Abstract

Determination and differentiation of skeletal muscle precursors requires cell-cell contact, but the full range of cell surface proteins that mediate this requirement and the mechanisms by which they work are not known. To identify participants in cell contact-mediated regulation of myogenesis, genes that encode secreted proteins specifically upregulated during differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts were identified by the yeast signal sequence trap method (K. A. Jacobs, L. A. Collins-Racie, M. Colbert, M. Duckett, M. Golden-Fleet, K. Kelleher, R. Kriz, E. R. La Vallie, D. Merberg, V. Spaulding, J. Stover, M. J. Williamson, and J. M. McCoy, Gene 198:289–296, 1997), followed by RNA expression analysis. We report here the identification of CD164 as a gene expressed in proliferating C2C12 cells that is upregulated during differentiation. CD164 encodes a widely expressed cell surface sialomucin that has been implicated in regulation of cell proliferation and adhesion during hematopoiesis. Stable overexpression of CD164 in C2C12 and F3 myoblasts enhanced their differentiation, as assessed by both morphological and biochemical criteria. Furthermore, expression of antisense CD164 or soluble extracellular regions of CD164 inhibited myogenic differentiation. Treatment of C2C12 cells with sialidase or O-sialoglycoprotease, two enzymes previously reported to destroy functional epitopes on CD164, also inhibited differentiation. These data indicate that (i) CD164 may play a rate-limiting role in differentiation of cultured myoblasts, (ii) sialomucins represent a class of potential effectors of cell contact-mediated regulation of myogenesis, and (iii) carbohydrate-based cell recognition may play a role in mediating this phenomenon.

Skeletal myogenesis is an excellent model system for the study of cell lineage determination, cell differentiation, and tissue-specific gene expression. These processes are regulated by a positive-feedback network of transcription factors comprised, at its core, of the myogenic basic helix-loop-helix factors (MyoD, Myf-5, myogenin, and MRF4) and members of the MEF-2 family (31, 33, 45). Myogenic basic helix-loop-helix and MEF-2 factors act individually and together to maintain their own expression, coordinate withdrawal from the cell cycle, and activate muscle-specific genes (31, 33, 45).

Despite the wealth of information about transcriptional control of myogenic differentiation, several observations suggest that myogenesis, and therefore presumably the core positive-feedback network, may be positively regulated by cell contact-mediated interactions between muscle precursor cells. For example, such interactions are required for myogenic determination and differentiation of explanted embryonic mesodermal cells of both frog and mouse origin, a phenomenon referred to as the community effect (11, 18, 19). Furthermore, differentiation of certain myogenic cell lines is dependent on cell aggregation (1, 37). Finally, it is widely appreciated that high cell density is a strong prodifferentiation condition for C2C12 and other well-studied myogenic cell lines in monolayer culture. The mechanisms by which cell surface proteins mediate such effects are not well understood. Proteins predicted to play a role include various cadherins and immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily members (14, 20, 25, 37, 47). It seems likely, however, that additional, as yet unidentified proteins will also prove to be involved.

Sialomucins are a heterogeneous class of secreted and cell surface proteins characterized by one or more regions (mucin domains) that contain a high percentage of proline, threonine, and serine residues; examples include CD34, CD43, PSGL-1, GlyCAM-1, MAdCAM-1, and the MUC family (for a review, see reference 39). The threonine and serine residues are heavily O-glycosylated, and these O-linked glycans are very important to sialomucin function. For example, CD34 and other sialomucins serve as high-affinity ligands for selectins; selectins recognize sialylated carbohydrate structures on these ligands during the adhesion cascade by which leukocytes move from blood into tissues (38). Furthermore, sialomucins may serve as signaling receptors that regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis in the hematopoietic compartment, functions that are thought to be, at least in part, dependent on carbohydrate modification (3, 16, 30, 40, 41).

CD164 (also known as MGC-24v and endolyn) is a recently identified sialomucin implicated in hematopoiesis, although it is expressed at the mRNA level in most murine and human tissues, including skeletal muscle (21, 29, 41, 46). CD164 contains an extracellular region comprised of two mucin domains linked by a cysteine-rich motif that resembles a consensus pattern previously found in growth factor and cytokine receptors. CD164 also contains a single-pass transmembrane domain and a 13-amino-acid intracellular region that includes a C-terminal motif able to target the protein to endosomes and lysosomes (21). Like other sialomucins, CD164 is highly glycosylated, containing both O- and N-linked glycans (15). Furthermore, monoclonal antibodies that recognize carbohydrate-dependent epitopes on mucin domain I of CD164 affect adhesion and proliferation of hematopoietic precursor cells (15).

In order to identify cell surface proteins involved in cell contact-mediated regulation of myogenesis, we have used the yeast signal sequence trap, a cDNA library-based screening technique that permits the identification of genes encoding secreted and membrane-associated proteins (22, 23). Subsequent to isolation of positive clones, RNA expression analysis was used to further identify mRNAs whose expression is enhanced during differentiation of cultured myoblasts. We report here the identification of CD164 as a gene that is expressed in proliferating myoblasts, is upregulated during myogenic differentiation, and functions as a positive regulator of this process. Overexpression of CD164 enhanced differentiation of two independent myoblast cell lines, while expression of an antisense CD164 cDNA or soluble extracellular forms of CD164 inhibited differentiation. Finally, treatment of myoblasts with sialidase or O-sialoglycoprotease also inhibited differentiation. These data indicate that sialomucins represent a class of potential effectors of cell contact-mediated regulation of myogenic differentiation. The results also raise the possibility that carbohydrate-based cell recognition events play a role in this phenomenon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RNA isolation, library construction, and screening.

RNA used for cDNA library construction and dot blot and Northern blot analyses was prepared with the Trizol reagent (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). The polyadenylated fraction was obtained with the MessageMaker mRNA isolation system (Gibco-BRL). A random-primed, directional cDNA library was constructed in the signal sequence trap vector pSUC2T7M13ORI (23) with mRNA isolated from a mixture of proliferating, differentiating, and fully differentiated C2C12 cells. The library (>2 × 107 independent clones) was constructed with the SuperScript Choice System kit from Gibco-BRL and amplified in Escherichia coli by the protocols of Jacobs et al. (22). The amplified cDNA library was transformed into the SUC2− Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain YTK12 with lithium acetate (5), and plasmids were isolated from colonies which survived invertase selection by growing on medium containing raffinose and antimycin A (22). The plasmid DNAs were then transformed into E. coli by electroporation and purified for sequencing, which was performed at the Mount Sinai DNA Sequencing Core Facility.

Cell culture.

C2C12 cells (7) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) plus 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (growth medium [GM]). The myoblast cell lines P2 and F3 (12), 10T1/2 cells, and 293T cells were all cultured in DMEM plus 10% FBS. Cells were induced to differentiate at 90 to 95% confluence by transferring them into DMEM plus 2% horse serum (differentiation medium [DM]).

Overexpression of CD164.

A mouse CD164 cDNA (656 bp), including the entire open reading frame, 21 bp of the 5′ untranslated region, and 41 bp of the 3′ untranslated region, was isolated by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR on total RNA from C2C12 cells with primers 5′-CCGGAATTCGACGCCTGGGCTGAAGACACA-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCCAAGCTTCACAAGTTAACTGCCAGTCCA-3′ (antisense). The cDNA, whose sequence was identical to mouse CD164/MGC-24v (GenBank accession number AB014464), was ligated into the retroviral expression vector pMV7 (26). Production of recombinant retroviruses and infection of C2C12 and F3 cells were performed as previously described by Kang et al. (24). Infected cultures were selected in medium that contained appropriate antibiotics, and antibiotic-resistant colonies were pooled and analyzed as described in Results.

RNA and protein analyses.

Northern blot analyses were performed by fractionating total cellular RNA through agarose-formaldehyde gels, blotting to nylon membranes, and hybridizing with DNA probes as described by Krauss et al. (28). Immunoblot analyses were performed essentially as described by Kang et al. (24). Cultures were harvested in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, [pH 7.2]. 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 1 mM EGTA) containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 ng/ml leupeptin, 50 mM NaF, and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. Cell lysates were then separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Life Science, Inc., Arlington Heights, Ill.), and the membranes were probed with one of the following antibodies from the indicated sources: anti-myosin heavy chain (MHC) (MF20 [2]); antitroponin T (TnT; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.); anti-MyoD (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.); and antimyogenin (FD5) (44). After extensive washing with 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–50 mM NaCl–1 mM EDTA–0.1% Tween 20, the blots were reprobed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, and specific protein bands were visualized with the Lumi-Light chemiluminescent detection system (Roche).

Fluorescence microscopy.

Immunocytochemical staining for MHC was performed with the monoclonal antibody MF20. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed for 1 min with 100% methanol, and blocked with 5% horse serum–PBS for 1 h at room temperature. After incubating cells with MF20 antibody for 1 h at room temperature, cells were washed three times with PBS. Secondary detection was carried out by incubation for 1 h at room temperature with a 1:200 dilution of fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Nuclei were counterstained by incubation for 5 min using DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; 0.5 μg/ml). Fluorescence photomicroscopy was performed on a Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope, and images were captured digitally with Spot TM 3.0.5 (Apple Event) software.

Myogenic colony assay.

C2C12 cells were infected with pBabePuro-based retroviruses (34) harboring the mouse CD164 cDNA in the antisense orientation or, as a control, retroviruses lacking a cDNA insert. After a 2-week selection in GM containing 5 μg of puromycin per ml, macroscopic colonies were easily visible; the cultures were then switched to DM for 24 h and stained with a monoclonal antibody to MHC (MF20) as described by Bader et al. (2). After sequential incubation with biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin, cells were stained with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma Chemical Co.), and colonies were analyzed by microscopy as described in Results.

CD164 fusion proteins.

A PCR-derived fragment containing the signal sequence and entire extracellular region of mouse CD164 was subcloned into the Aptag-2 or Igtag vector (6) to produce CD164-alkaline phosphate (AP) and CD164-Fc, respectively. The following PCR primers were used to amplify the appropriate CD164 cDNA product: 5′-GGAAGATCTGAAGACACAATGTCGGGCTCC-3′ (sense), and 5′-GGAAGATCTTGCATCAAAGGTCGACTTCCG-3′ (antisense). These vectors, which place the fusion proteins under the transcriptional control of the cytomegalovirus promoter, were transfected into C2C12 cells with the Fugene reagent (Roche Diagnostic Corporation, Indianapolis, Ind.). Ten micrograms of each vector was cotransfected with 1 μg of pBabePuro, and cultures were selected in medium containing 5 μg of puromycin per ml. Aptag-4, which encodes a secreted, soluble form of AP itself, was used as a control. Secretion of CD164-AP and AP into the medium of selected cultures was determined by colorimetric assay of AP activity in conditioned medium (CM) as described by Flanagan and Leder (17). Production of CD164-Fc was determined by immunoprecipitation of CM with protein A-Sepharose, followed by immunoblot analysis of eluted proteins with HRP-coupled goat anti-human IgG.

To assess the differentiation capacity of C2C12 cells that constitutively secreted these proteins into the medium, the stably transfected cells were plated in GM and cultured to allow the medium to become depleted of growth factors (25). To assess the ability of CD164-Fc and CD164-AP to block differentiation of C2C12 cells in trans, these proteins were produced by transient transfection of 293T cells by the calcium phosphate method (43). C2C12 cells were plated at high density and transferred to DM at 95% confluence. After 12 h, one-half of the DM was removed and an equivalent volume of CM derived from 293T cells transfected with one of the fusion protein constructs was added to the cultures. A 1:1 mixture of fresh 293T cell-derived CM and DM was added to these cultures every 12 h for 4 days.

Treatment of C2C12 cells with sialidase and O-sialoglycoprotease.

Clostridium perfringens sialidase was purchased from Sigma, and Pasteurella haemolytica O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase (O-sialoglycoprotease) was purchased from Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corp. (Westbury, N.Y.). For treatment of C2C12 cells, cells were incubated with 0.025 U of sialidase or 15 μg of O-sialoglycoprotease per ml for 24 h in DM; fresh enzyme in DM was added to the cells every 24 h for 3 days. To test for the ability of CD164 to serve as a substrate for these enzymes, CM from 293T cells transiently transfected with the CD164-Fc expression vector was used. CM was treated overnight (≈16 h) with double the concentrations of sialidase or O-sialoglycoprotease stated above and then analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and staining with Coomassie blue, Western blot analysis with detection by HRP-coupled goat anti-human IgG, and the Immun-Blot kit for glycoprotein detection (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The kit was used according to the manufacturer's instructions for specific detection of terminal sialic acid residues on proteins bound to a nitrocellulose membrane. Briefly, terminal sialic acid residues on CD164-Fc were subjected to a specific oxidation reaction to label them with biotin; subsequent detection was done with streptavidin-AP and color development reagents.

RESULTS

Identification of CD164 as a gene whose expression is upregulated during C2C12 myoblast differentiation.

To isolate cDNAs that encode secreted proteins whose expression is upregulated during myogenic differentiation, a two-step strategy was employed. First, a cDNA library from a mixture of proliferating, differentiating, and fully differentiated C2C12 cells was constructed in the signal sequence trap vector pSUC2T7M13ORI. As originally described by Jacobs et al. (23), this vector harbors a yeast invertase gene that lacks both a methionine to initiate translation and a signal sequence to direct the translated product into the secretory pathway. It is possible, therefore, to use an invertase selection protocol in yeast to isolate cDNAs that provide a start codon followed by a functional signal sequence when they are ligated in frame with the invertase gene (23). Second, cDNA inserts from plasmids that were isolated by such a selection protocol were used as probes on dot blots of total RNAs derived from C2C12 cells at various stages of differentiation, as well as several other myoblast and fibroblast cell lines (data not shown). One such cDNA fragment that hybridized to an mRNA whose expression was enhanced during C2C12 cell differentiation corresponded to the 5′ end of murine CD164. A full-length CD164 cDNA was subsequently isolated from C2C12 cells by RT-PCR; this cDNA encodes the major CD164 isoform that includes all six exons (8, 29).

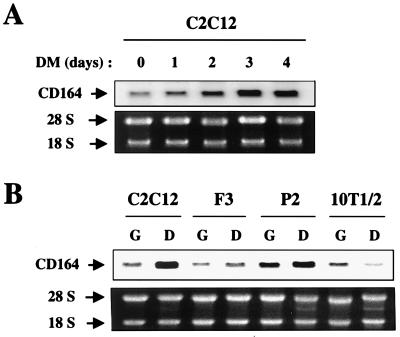

CD164 mRNA expression was examined more closely by Northern blot analysis with the CD164 cDNA as a probe. C2C12 cells cultured in serum-rich GM expressed CD164 mRNA, and expression rose progressively after the cells were transferred into mitogen-deficient DM. After 3 days in DM, CD164 mRNA levels had increased approximately fourfold (Fig. 1A). The relative levels of CD164 mRNA in GM and DM were also determined in F3 and P2, two independent myoblast cell lines derived by treatment of 10T1/2 fibroblasts with 5-azacytidine (12). CD164 mRNA levels increased slightly in both F3 and P2 cells when cultured in DM for 3 days (Fig. 1B). However, in contrast, parental 10T1/2 fibroblasts displayed decreased amounts of CD164 mRNA when cultured in DM (Fig 1B). These data indicate that the elevation of CD164 mRNA seen in the three myoblast cell lines was associated with myogenic differentiation and not a consequence of serum starvation or withdrawal from the cell cycle.

FIG. 1.

Expression of CD164 mRNA during myogenic differentiation in vitro. (A) C2C12 myoblasts were grown to near confluence in GM, shifted into DM, and harvested at the indicated time points. The upper panel shows a Northern blot analysis of CD164 mRNA expression. The ethidium bromide-stained gel displaying the 28S and 18S rRNA bands is shown in the lower panel as a loading control. (B) C2C12, F3, and P2 myoblasts and 10T1/2 fibroblasts were cultured during log-phase growth in GM (G) or at confluence for 3 days in DM (D) and harvested for Northern blot analysis as shown in the top panel. The ethidium bromide-stained gel displaying the 28S and 18S rRNA bands is shown in the lower panel as a loading control.

Overexpression of CD164 enhances differentiation of C2C12 and F3 myoblasts.

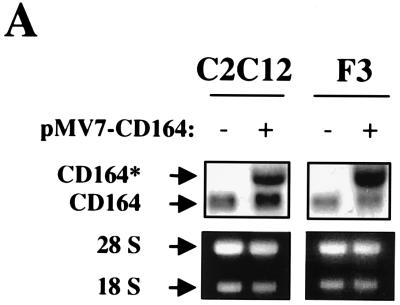

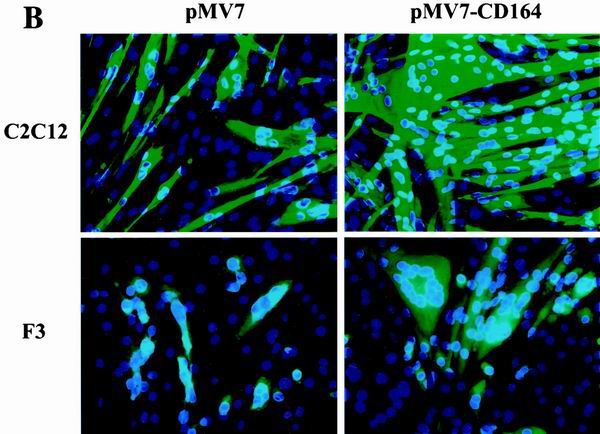

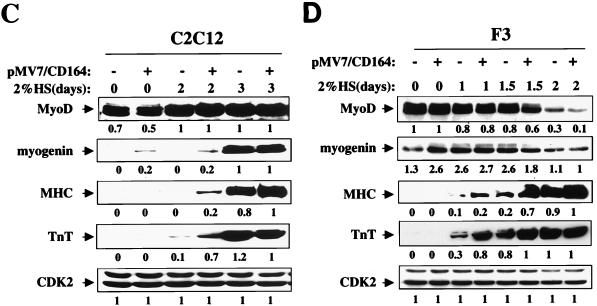

To investigate the function of CD164 during myoblast differentiation, C2C12 and F3 cells that overexpress CD164 were generated. Cells were infected with control (pMV7) or CD164-expressing (pMV7-CD164) retroviruses and selected for G418 resistance; drug-resistant colonies were pooled and examined for expression of CD164 mRNA and their ability to differentiate. The CD164 virus-infected cells (designated C2C12/CD164 cells and F3/CD164 cells) displayed expression of both an endogenous ≈3.0-kb CD164 mRNA and a vector-derived ≈3.9-kb CD164 mRNA, while control vector-infected cells (designated C2C12/neo cells and F3/neo cells) expressed only the endogenous mRNA species (Fig. 2A). Overexpression of CD164 had no obvious effect on the morphology of C2C12 or F3 cells or on their ability to proliferate in GM (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Overexpression of CD164 enhances differentiation of C2C12 and F3 myoblasts. C2C12 and F3 cells were stably infected with recombinant control (pMV7) or CD164-expressing (pMV7-CD164) retroviruses, selected with G418, and analyzed for expression of CD164 mRNA, myotube formation, and expression of muscle-specific proteins. (A) Northern blot analysis of CD164 mRNAs in infected cells. −, infection with pMV7 virus; +, infection with pMV7-CD164 virus. (B) Immunofluorescence photomicrographs of infectants. C2C12 and F3 cells stably infected with the indicated viruses were cultured in DM for 3 days, fixed, and doubly stained with a monoclonal antibody to MHC (detected with a fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody) and with DAPI for nuclear DNA. (C) Western blot analysis of muscle-specific proteins and, as a control, CDK2 expressed by C2C12 infectants cultured in DM for the indicated times. −, infection with pMV7 virus; +, infection with pMV7-CD164 virus. (D) Western blot analysis of muscle-specific proteins and, as a control, CDK2 expressed by F3 infectants cultured in DM for the indicated times. −, infection with pMV7 virus; +, infection with pMV7-CD164 virus. The numbers below the Western blots in C and D represent relative levels of each protein derived by densitometric analysis of the signal.

When challenged to differentiate, C2C12/neo and F3/neo cells closely resembled their parental lines, producing multinucleated, MHC-positive myotubes of either an elongated or “stubbier” morphology, respectively (Fig. 2B). In contrast, C2C12/CD164 cells and F3/CD164 cells had a strongly enhanced differentiation response, as assessed by the morphology of the myotubes formed (Fig. 2B) and quantitated by the percentage of nuclei present in MHC-positive myotubes (Table 1). Consistent with these results, expression of the differentiation markers myogenin, MHC, and TnT was accelerated in C2C12/CD164 and F3/CD164 cells relative to control cells, as determined by Western blot analysis of lysates from cells cultured in DM for 0 to 3 days and 0 to 2 days, respectively (Fig. 2C and 2D; F3 cells completed the differentiation process more quickly than did C2C12 cells, so slightly different time courses were used for the two different cell lines). Overexpression of CD164 did not significantly alter MyoD protein levels in either cell line (Fig. 2C and 2D). It is concluded that overexpression of CD164 enhances both morphological and biochemical aspects of myogenic differentiation. It is worth noting, however, that overexpression of CD164 appeared to have a more pronounced effect on formation of multinucleate myotubes than on expression of biochemical markers of differentiation, raising the possibility that it may play a role in regulating myoblast fusion.

TABLE 1.

Effects of manipulating CD164 levels or function on myogenic differentiationa

| Treatment and cells | % of nuclei in MHC-positive myotubes |

|---|---|

| Stable infection or transfectionb | |

| C2C12/neo (control) | 29.4 ± 3.3 |

| C2C12/CD164 | 64.9 ± 11.2d |

| F3/neo (control) | 27.5 ± 2.3 |

| F3/CD164 | 56.8 ± 5.9d |

| C2C12/AP (control) | 26.3 ± 1.3 |

| C2C12/CD164-AP | 8.6 ± 0.8d |

| C2C12/CD164-Fc | 9.3 ± 2.2d |

| Conditioned mediumc | |

| C2C12 + AP (CM) (control) | 15.4 ± 0.6 |

| C2C12 + CD164-AP (CM) | 6.0 ± 0.3d |

| C2C12 + CD164-Fc (CM) | 6.5 ± 0.5d |

| Enzyme | |

| C2C12 (control) | 35.3 ± 6.4 |

| C2C12 + sialidase | 6.6 ± 0.4d |

| C2C12 + O-sialoglycoprotease | 5.1 ± 0.3d |

Cells were cultured in DM for 3 days except as noted in footnote c. Values are the means of eight determinations from three independent experiments (two quantitated in triplicate, one quantitated in duplicate) ± 1 standard deviation.

Cells were stably infected or transfected with expression vectors for the indicated proteins as described in the text.

Cells were cultured in a 1:1 mixture of DM and CM derived from 293T cells transiently transfected with expression vectors for the indicated proteins.

P < 0.01 by two-tailed t test compared with control in each grouping.

Expression of an antisense CD164 vector inhibits C2C12 cell differentiation.

To determine whether inhibition of CD164 expression interferes with myogenic differentiation, the ability of an antisense CD164 expression vector to inhibit colonies of C2C12 cells from differentiating was assessed. C2C12 cells were infected with control (pBabePuro) or CD164 antisense-expressing (pBabePuro/asCD164) retroviruses and selected with puromycin. When puromycin-resistant colonies emerged, they were shifted into DM for 1 day, and the percentage of MHC-positive cells within the colonies was scored (Table 2). Compared to colonies infected with pBabePuro, colonies infected with pBabePuro/asCD164 displayed substantially fewer MHC-positive cells, suggesting that CD164 levels may be rate-limiting for myoblast differentiation. To test the effectiveness of the antisense vector, Northern blot analysis was performed on a polyclonal C2C12 line that had been stably propagated after infection with pBabePuro/asCD164 and selection in puromycin. Figure 3 shows that this line expressed exogenous vector-derived mRNA of the predicted size (≈3.6 kb) and displayed a concomitant loss of the endogenous CD164 mRNA (≈3.0 kb), presumably via degradation of RNA:RNA hybrids. As expected, these cells showed a reduced ability to differentiate in response to DM relative to control cells (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Effect of antisense CD164 expression on C2C12 cell differentiationa

| % Range of MHC-positive cells/colony | % of colonies displaying the indicated range of MHC-positive cells per colony

|

|

|---|---|---|

| pBabePuro (control) | pBabePuro/asCD164 | |

| 0 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 42.0 ± 1.5 |

| 0.1–5 | 31.2 ± 2.7 | 44.7 ± 6.1 |

| 5–20 | 23.9 ± 4.0 | 8.9 ± 0.7 |

| 20–50 | 19.9 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± 2.7 |

| >50 | 24.2 ± 2.5 | 0.85 ± 1.2 |

C2C12 cells were infected with control (pBabePuro) or CD164 antisense-expressing (pBabePuro/asCD164) retroviruses and selected with puromycin; after 2 weeks, puromycin-resistant colonies were shifted into DM for 1 day, fixed, and stained with a monoclonal antibody to MHC, and the percentage of MHC-positive cells within the colonies was scored. At least 100 colonies were scored per infection. The values represent means ± 1 standard deviation from four infections.

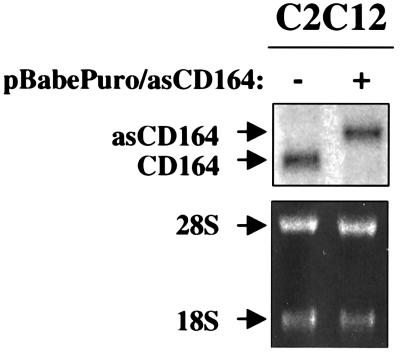

FIG. 3.

C2C12 cells that express an antisense CD164 construct display a concomitant loss of endogenous CD164 mRNA. Northern blot analysis of CD164 mRNAs in infected cells is shown. −, infection with control pBabePuro virus; +, infection with pBabePuro/asCD164 virus. Note that the cells infected with pBabePuro/asCD164 virus express a vector-derived band (≈3.6 kb) and have much reduced levels of endogenous CD164 mRNA (≈3.0 kb). A full-length, double-stranded CD164 probe was used to detect both mRNAs. The ethidium bromide-stained gel displaying the 28S and 18S rRNA bands is shown in the lower panel as a loading control.

Secreted, soluble extracellular regions of CD164 inhibit C2C12 cell differentiation.

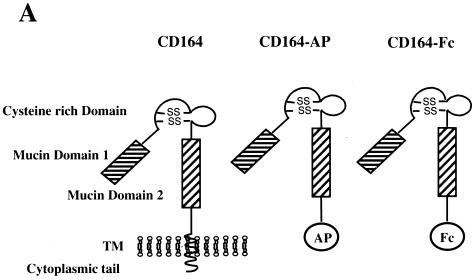

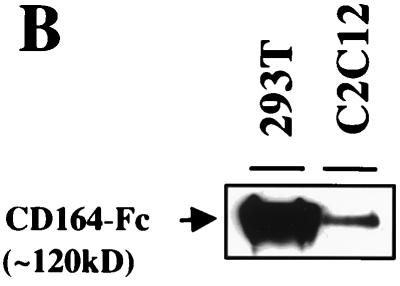

Many membrane-associated sialomucins play a role in cell-cell interactions by serving as ligands or receptors for selectins or other yet to be identified extracellular and membrane-associated factors (38–41). If CD164 functions to mediate interactions between myoblasts that contribute positively towards differentiation, it would be predicted that expression of soluble extracellular regions of CD164 by C2C12 cells might compete with endogenous membrane-bound CD164 and affect differentiation. To test this possibility, recombinant soluble fusion proteins that contain the entire CD164 extracellular region coupled to either AP or the Fc region of human IgG (CD164-AP and CD164-Fc, respectively; Fig. 4A) were constructed. C2C12 cells were stably transfected with expression vectors for CD164-AP, CD164-Fc, and, as a control, secreted AP alone. AP activity was easily detected in the CM of the CD164-AP and AP transfectants (data not shown), and CD164-Fc was detected immunologically in CM from the CD164-Fc transfectants (Fig. 4B).

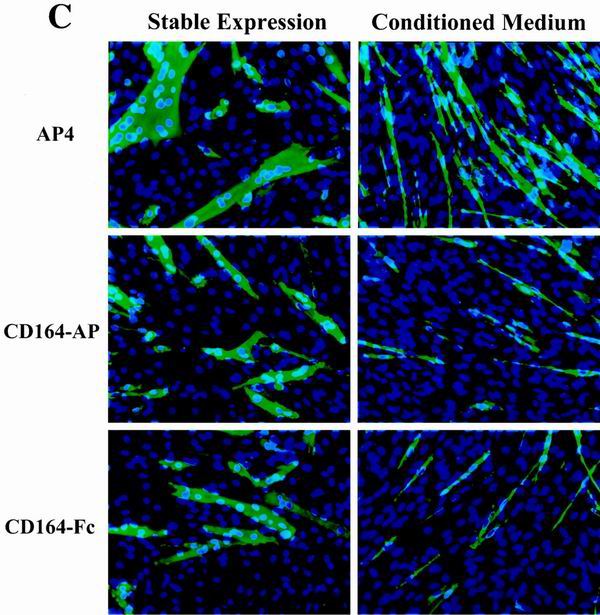

FIG. 4.

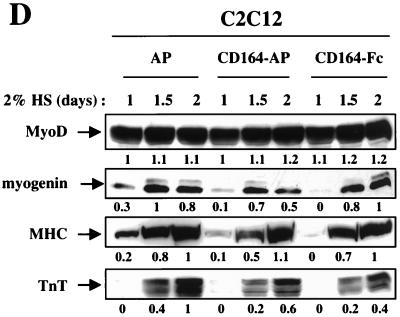

Secreted, soluble extracellular regions of CD164 inhibit C2C12 cell differentiation. (A) Schematic representation of CD164 and the soluble fusion proteins CD164-AP and CD164-Fc. The pictured structure of two mucin domains linked by a cysteine-rich region containing putative disulfide bonds is based on data from reference 21. (B) Western blot analysis of CD164-Fc in CM from transiently transfected 293T cells and stably transfected C2C12 cells. (C) Left column, immunofluorescence photomicrographs of C2C12 cells stably transfected with expression vectors for the indicated proteins and cultured in DM for 3 days. Right column, immunofluorescence photomicrographs of C2C12 cells cultured for 3 days in a 1:1 mixture of DM and CM derived from 293T cells transiently transfected with expression vectors for the indicated proteins. Cultures were fixed and doubly stained with a monoclonal antibody to MHC (detected with a fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody) and with DAPI for nuclear DNA. (D) Western blot analysis of muscle-specific proteins expressed by C2C12 cells stably transfected with expression vectors for the indicated proteins and cultured under differentiation-inducing conditions for the indicated times (see Materials and Methods for details). The numbers below the Western blots in D represent relative levels of each protein derived by densitometric analysis of the signal.

These cells were then assessed for their ability to differentiate. As shown in Fig. 4C and Table 1, control cells that expressed AP differentiated similarly to the parental line, forming extensive multinucleate myotubes. In contrast, cells that stably produced either of the soluble CD164 proteins formed smaller myotubes with fewer nuclei than did control cells (Fig. 4C and Table 1). Consistent with this result, when C2C12 cells expressing CD164-AP or CD164-Fc were challenged with DM, accumulation of the differentiation markers myogenin, MHC, and TnT was delayed (Fig. 4D). As was observed with overexpression of CD164 (Fig. 2C), however, inhibition by CD164-AP or CD164-Fc was not accompanied by alterations in the levels of MyoD (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, also as seen with overexpression of CD164, the effects of CD164-AP and CD164-Fc on myotube formation appeared to be more pronounced than their effects on biochemical aspects of differentiation.

Comparable results to those seen with stable expression of CD164-AP and CD164-Fc were obtained when CM from 293T cells transiently transfected with expression vectors for these proteins was added 1:1 with DM to cultures of parental C2C12 cells, but not when CM from AP vector-transfected cells was used (Fig. 4B and C and Table 1). It should be noted that the use of serum-containing CM in the differentiation assay resulted in a somewhat altered myotube morphology and a decrease in the percentage of nuclei found in MHC-positive cells relative to control cultures in 100% DM; nevertheless, the percent inhibition of multinucleate myotube formation by CD164-AP and CD164-Fc was similar whether these proteins were stably produced by C2C12 cells or supplied in trans via CM (Table 1).

Treatment of C2C12 cells with sialidase or O-sialoglycoprotease inhibits differentiation.

Sialomucins, including CD164, have the common characteristic of being highly glycosylated polypeptides, containing both O- and N-linked carbohydrate side chains (39, 41). Monoclonal antibodies against CD164 that alter the adhesive and proliferative properties of hematopoietic precursors recognize epitopes that are destroyed by treatment of cells with sialidase, which cleaves terminal sialic acid residues on O- or N-linked carbohydrates, or O-sialoglycoprotease, an enzyme that selectively degrades O-sialomucins (9, 32). It would be predicted, therefore, that treatment of C2C12 cells with these enzymes would inhibit differentiation.

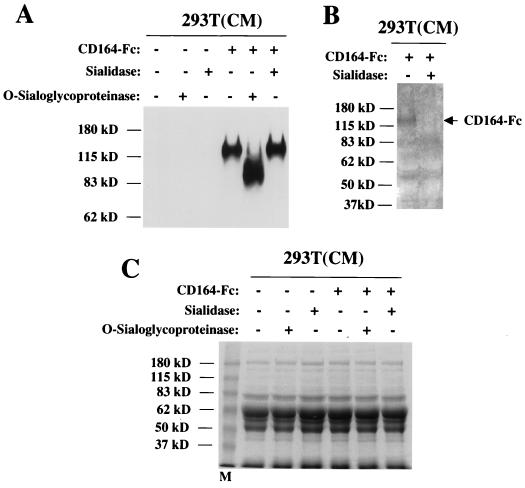

To first confirm that CD164 is a substrate for sialidase and O-sialoglycoprotease and that commercially available preparations of these enzymes were not significantly contaminated with nonspecific proteases, CD164-Fc in CM from transiently transfected 293T cells was used as a test substrate. Figure 5A shows a Western blot analysis of CM treated with each enzyme, using anti-human Fc antibodies to detect the soluble fusion protein. CD164-Fc was quantitatively cleaved by O-sialoglycoprotease, as demonstrated by its shift to a lower molecular weight; in contrast, sialidase treatment did not significantly alter the migration of CD164-Fc, as would be predicted if only terminal sialic acid residues were removed.

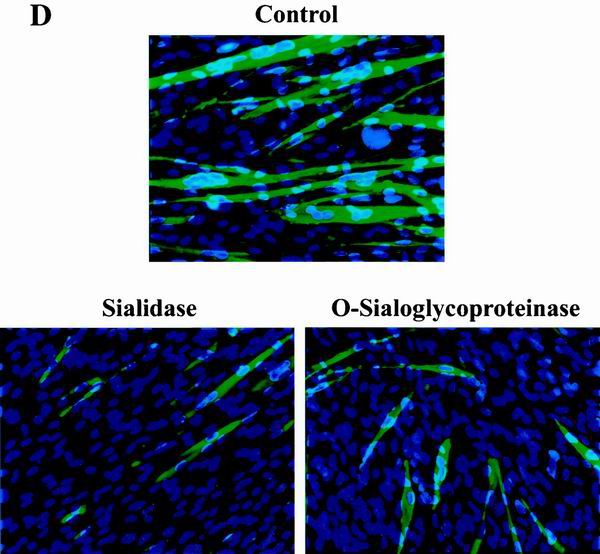

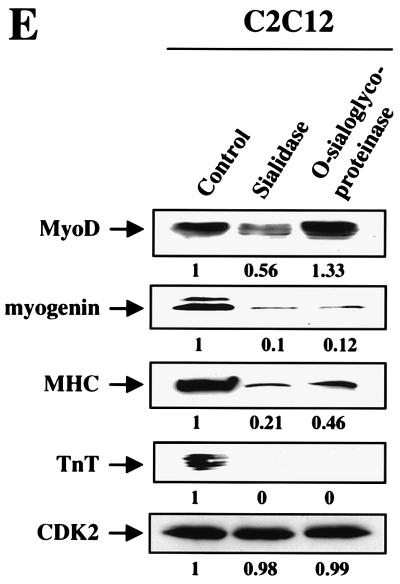

FIG. 5.

CD164 is a substrate for sialidase and O-sialoglycoprotease, and treatment of C2C12 cells with these enzymes inhibits differentiation. (A) Western blot analysis of the effects of sialidase and O-sialoglycoprotease on CD164-Fc present in CM of transiently transfected 293T cells. (B) Detection of terminal sialic acid residues on CD164-Fc in 293T CM treated or not with sialidase (see Materials and Methods for details). (C) Assessment of nonspecific protease activity in preparations of sialidase and O-sialoglycoprotease. Duplicates of the samples in panel A were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and the gel was stained with Coomassie blue. Lane M, protein markers. (D) Immunofluorescence photomicrographs of C2C12 cells cultured in DM for 3 days with and without the indicated enzymes. Cultures were fixed and doubly stained with a monoclonal antibody to MHC (detected with a fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody) and with DAPI for nuclear DNA. (E) Western blot analysis of muscle-specific proteins and, as a control, CDK2 expressed by C2C12 cells cultured in DM for 3 days with or without the indicated enzymes. The numbers below the Western blots in E represent relative levels of each protein derived by densitometric analysis of the signal.

To test the efficacy of the sialidase treatment, the samples shown in Fig. 5A were analyzed with a biotin-labeling procedure specific for sialic acid as a terminal monosaccharide. As can be seen in Fig. 5B, treatment of the CM led to a loss of CD164-Fc reactivity. As a control for nonspecific protease activity, duplicates of the samples displayed in Fig. 5A were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and the gel was stained with Coomassie blue (Fig. 5C). No loss of protein bands in the CM was observed in the enzyme-treated samples. It is concluded that CD164 is a specific substrate for both sialidase and O-sialoglycoprotease and that the enzyme preparations used are free of significant levels of nonspecific protease activity.

The effect of sialidase and O-sialoglycoprotease on C2C12 cell differentiation was assessed by addition of the enzymes to the culture medium. As shown in Fig. 5D and Table 1, treatment of C2C12 cells with either enzyme inhibited myotube formation in response to 3 days of culture in DM without altering cell viability (data not shown). Consistent with this decrease in morphological aspects of differentiation, expression of myogenin, MHC, and TnT was strongly reduced in both sialidase- and O-sialoglycoprotease-treated cells (Fig. 5E). MyoD levels were not altered by O-sialoglycoprotease, but were reduced approximately 50% by sialidase (Fig. 5E). In contrast, neither enzyme altered the amount of CDK2 produced by C2C12 cells (Fig. 5E), indicating that the cells were healthy and suggesting that the effects on expression of muscle-specific proteins were not nonspecific. Although it is obviously not possible to conclude that CD164 is the only relevant target of these enzymes, these results fulfill a prediction raised by the hypothesis that CD164 levels are rate-limiting for differentiation of C2C12 cells.

DISCUSSION

Determination and differentiation of skeletal muscle precursors requires cell-cell contact, and various cadherins and immunoglobulin superfamily members have been proposed to play a role in mediating this requirement (14, 20, 25, 37, 47). We report here that CD164, a cell surface sialomucin, has properties consistent with a role in mediating cell-cell interactions that contribute to myogenesis. CD164 was isolated in this study by signal sequence trapping in yeast, an efficient method for selecting genes that encode secreted proteins from complex libraries (22, 23). The additional step of rapidly screening positive clones for their expression pattern during myogenic differentiation permitted the identification of CD164 as a gene expressed in proliferating C2C12 myoblasts that is upregulated during differentiation. Subsequent functional analyses demonstrated that overexpression of CD164 in myoblast cell lines accelerated expression of biochemical markers of differentiation and enhanced formation of multinucleate myotubes, while expression of antisense CD164 or soluble extracellular regions of CD164 inhibited myogenesis. Finally, treatment of C2C12 myoblasts with sialidase or O-sialoglycoprotease, two enzymes that destroy functional epitopes on CD164 (15), also inhibited differentiation. Taken together, these data are consistent with the hypothesis that CD164 may play a rate-limiting role in myogenic differentiation in vitro.

While manipulation of CD164 levels or function could enhance or inhibit differentiation of myoblasts, as assessed by formation of multinucleate myotubes or by expression of the differentiation markers myogenin, MHC, and TnT, it did so without altering the levels of MyoD protein produced by these cells. This observation suggests that CD164 might somehow serve to increase MyoD activity at a posttranslational level, an event that precedes induction of myogenin and muscle structural proteins in myogenic differentiation. Very similar data were obtained in this lab with C2C12 and other myoblast cell lines by stable expression of wild-type or interfering mutants of CDO, a receptor-like protein that contains five Ig and three FNIII repeats (25). It will be interesting to determine whether CD164 and CDO exert their effects by a similar mechanism. However, whereas CDO has a long intracellular region that could easily function as a docking site for adapter proteins or enzymes involved in signaling, CD164's intracellular region is only 13 amino acids long, including 4 at the carboxy terminus that target the protein to lysosomes and endosomes (21).

It is not immediately obvious, therefore, how CD164 could serve as a signaling receptor in this context. One possibility is that CD164 may facilitate signaling by binding to other receptors or adhesion molecules as part of a complex. Alternatively, CD164 might function as a ligand for a signaling receptor present on the surface of adjacent myoblasts. It is also important to note that alteration of CD164 level or function appeared to have a more pronounced effect on morphological aspects of differentiation (i.e., formation of multinucleate myotubes) than on biochemical aspects of differentiation (i.e., expression of muscle-specific proteins). CD164 may therefore be more directly involved in regulating myoblast fusion than in coordinating the entire myogenic differentiation program. Further studies will be needed to address this point.

The most clearly documented functions for sialomucins pertain to the traffic signals that regulate leukocyte localization in the vasculature (for a review, see reference 38). Molecules like CD34, GlyCAM, and MAdCAM are expressed on high endothelial venules to provide sialylated carbohydrate ligands for selectin receptors expressed on various leukocytes. Interactions of the opposite “polarity,” between specific sialomucins on leukocytes and selectins on activated endothelial cells, also occur. Selectin-sialomucin interactions are responsible for tethering flowing leukocytes to the vessel wall and for transient adhesive events involved in leukocyte rolling. These are required first steps in an adhesion cascade, with subsequent interactions between integrins and immunoglobulin superfamily members providing the more stable adhesive connections necessary for monocytes, neutrophils, and other cell types to exit the bloodstream and enter tissues. Because cell surface proteins of the cadherin, immunoglobulin, and, now, sialomucin families have all been implicated in myogenesis, it is tempting to speculate that, by analogy with the leukocyte traffic model, a series of adhesive and cell contact-mediated signaling interactions between myoblasts underlie phenomena such as the prodifferentiation effects of high cell density.

The function of sialomucins in leukocyte traffic depends on their specific glycosylation. Likewise, CD164 bears functional epitopes that are carbohydrate dependent (15). These observations raise the interesting possibility that carbohydrate-based cell recognition events may play a role in cell contact-mediated functions that are important in myogenesis. The fact that treatment of C2C12 cells with sialidase inhibited differentiation suggests that this may be true. It is important to note that many cell surface proteins in addition to CD164 are substrates for sialidase, and the most important substrates involved in mediating its inhibitory effects on myogenesis are not identified. Treatment of C2C12 cells with O-sialoglycoprotease also inhibited differentiation. This enzyme has a much more restricted set of substrates, apparently recognizing O-linked carbohydrates on mucin domain-containing proteins specifically and cleaving the polypeptide chain nearby (9, 32). CD164 may well be a major substrate of O-sialoglycoprotease on C2C12 cells, although the predicted cleavage and release of an amino-terminal fragment do not distinguish between the carbohydrate or peptide sequences lost as being of primary importance. Furthermore, the proteins to which the extracellular region of CD164 binds are not known; whether such interactions occur with lectin-like molecules via its extensive O- and N-linked sugars or with other types of receptors via its core protein sequence is also unknown. Nevertheless, expression of both lectin activity and specific lectin domain-containing proteins is regulated during myogenesis in vitro and in vivo (10, 13, 35, 36, 42), and the potential role of carbohydrate-based cell recognition events in differentiation is worthy of further exploration.

It is clear that sialomucins play roles other than those documented in leukocyte traffic as well. CD34 is a clinically useful marker of adult hematopoietic stem cells (27). Of relevance to the potential role of sialomucins in myogenesis, CD34 was also recently shown by Beauchamp et al. to be a marker for most, but not all, quiescent muscle satellite cells (4). CD34 mRNA expression is extinguished within 24 h of satellite cell activation, suggesting that it may play a role in maintaining the quiescent state of these cells (4). Additionally, CD34 is expressed in C2C12 myoblasts at very low levels in the great majority of cells in the culture; those few that express high levels of CD34 appear to represent a subset of cells that do not differentiate (4). These results suggest that CD34 and CD164 very likely perform different functions during myogenesis. Nevertheless, taking the results of Beauchamp et al. (4) together with the findings of this study, it can be concluded that sialomucins represent a family of cell surface proteins newly recognized as potentially important regulators of various aspects of muscle development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AR46207 and CA59474 from the NIH and a grant from the American Heart Association. J.-S.K. was supported by a fellowship from the Charles H. Revson Foundation and funds from the T.J. Martell Foundation for Leukemia, Cancer and AIDS Research. R.S.K. was a Career Scientist of the Irma T. Hirschl Trust and an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association during a portion of these studies.

The first two authors contributed equally.

We gratefully acknowledge Ken Jacobs and John McCoy for providing the yeast signal sequence trap system and for helpful advice; Justin Golub for his contribution to this study; David Sassoon, Phil Mulieri, Francesca Cole, Dario Coletti, and Jeanne Hirsch for critical reading of the manuscript; and the Mount Sinai DNA Sequencing Core Facility for sequencing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armour C, Garson K, McBurney M W. Cell-cell interaction modulates myoD-induced skeletal myogenesis of pluripotent P19 cells in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 1999;251:79–91. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bader D, Masaki T, Fischman D A. Immunochemical analysis of myosin heavy chain during avian myogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:763–770. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.3.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bazil V, Brandt J, Chen S, Roeding M, Luens K, Tsukamoto A, Hoffman R. A monoclonal antibody recognizing CD43 (leukosialin) initiates apoptosis of human hematopoietic progenitor cells but not stem cells. Blood. 1996;87:1272–1281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beauchamp J R, Heslop L, Yu D S, Tajbakhsh S, Kelly R G, Wernig A, Buckingham M, Partridge T A, Zammit P S. Expression of CD34 and Myf5 defines the majority of quiescent adult skeletal muscle satellite cells. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1221–1233. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker D M, Guarente L. High-efficiency transformation of yeast by electroporation. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:182–187. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergemann A D, Cheng H-W, Brambilla R, Klein R, Flanagan J G. ELF-2, a new member of the Eph ligand family, is segmentally expressed in mouse embryos in the region of the hindbrain and newly forming somites. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4921–4929. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blau H M, Chiu C-P, Webster C. Cytoplasmic activation of human nuclear genes in stable heterocaryons. Cell. 1983;32:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan J Y-H, Lee-Prudhoe J E, Jorgensen B, Ihrke G, Doyonnas R, Zannettino A C W, Buckle V J, Ward C J, Simmons P J, Watt S M. Relationship between novel isoforms, functionally important domains and subcellular distribution of CD164/endolyn. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2139–2152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007965200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark R A, Fuhlbrigge R C, Springer T A. l-Selectin ligands that are O-glycoprotease resistant and distinct from MECA-79 antigen are sufficient for tethering and rolling of lymphocytes on human high endothelial venules. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:721–731. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper D N W, Massa S M, Barondes S H. Endogenous muscle lectin inhibits myoblast adhesion to laminin. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1437–1448. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.5.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cossu G, Kelly R, Di Donna S, Vivarelli E, Buckingham M. Myoblast differentiation during mammalian somitogenesis is dependent upon a community effect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2254–2258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis R L, Weintraub H, Lassar A B. Expression of a single transfected cDNA converts fibroblasts to myoblasts. Cell. 1987;51:987–1000. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90585-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Den H, Malinzak D A, Keating H J, Rosenberg A. Influence of concanavalin A, wheat germ agglutinin, and soybean agglutinin on the fusion of myoblasts in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1975;67:826–834. doi: 10.1083/jcb.67.3.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickson G, Peck D, Moore S E, Barton C H, Walsh F S. Enhanced myogenesis in NCAM-transfected mouse myoblasts. Nature. 1990;344:348–351. doi: 10.1038/344348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doyonnas R, Chan J Y-H, Butler L H, Rappold I, Lee-Prudhoe J E, Zannettino A C W, Simmons P J, Buhring H-J, Levesque J P, Watt S M. CD164 monoclonal antibodies that block hematopoietic progenitor cell adhesion and proliferation interact with the first mucin domain of the CD164 receptor. J Immunol. 2000;165:840–851. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fackler M J, Krause D S, Smith O M, Civin C I, May W S. Full-length but not truncated CD34 inhibits hematopoietic cell differentiation of M1 cells. Blood. 1995;85:3040–3047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flanagan J G, Leder P. The kit ligand: a cell surface molecule altered in steel mutant fibroblasts. Cell. 1990;63:185–194. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90299-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurdon J B. A community effect in animal development. Nature. 1988;336:772–774. doi: 10.1038/336772a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurdon J B, Tiller E, Roberts J, Kato K. A community effect in muscle development. Curr Biol. 1993;3:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90139-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holt C E, Lemaire P, Gurdon J B. Cadherin-mediated cell interactions are necessary for the activation of MyoD in Xenopus mesoderm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10844–10848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ihrke G, Gray S R, Luzio J P. Endolyn is a mucin-like type I membrane protein targeted to lysosomes by its cytoplasmic tail. Biochem J. 2000;345:287–296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs K A, Collins-Racie L A, Colbert M, Duckett M, Evans C, Golden-Fleet M, Kelleher K, Kriz R, La Vallie E R, Merberg D, Spaulding V, Stover J, Williamson M J, McCoy J M. A genetic selection for isolating cDNA clones that encode signal peptides. Methods Enzymol. 1999;303:468–479. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)03028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobs K A, Collins-Racie L A, Colbert M, Duckett M, Golden-Fleet M, Kelleher K, Kriz R, La Vallie E R, Merberg D, Spaulding V, Stover J, Williamson M J, McCoy J M. A genetic selection for isolating cDNAs encoding secreted proteins. Gene. 1997;198:289–296. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00330-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang J-S, Gao M, Feinleib J L, Cotter P D, Guadagno S N, Krauss R S. CDO: an oncogene-, serum-, and anchorage-regulated member of the Ig/fibronectin type III repeat family. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:203–213. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang J-S, Mulieri P J, Miller C, Sassoon D A, Krauss R S. CDO, a Robo-related cell surface protein that mediates myogenic differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:403–413. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirschmeier P T, Housey G M, Johnson M D, Perkins A S, Weinstein I B. Construction and characterization of a retroviral vector demonstrating efficient expression of cloned cDNA sequences. DNA. 1988;7:219–225. doi: 10.1089/dna.1988.7.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krause D S, Fackler M J, Civin C I, May W S. CD34: structure, biology, and clinical utility. Blood. 1996;87:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krauss R S, Guadagno S N, Weinstein I B. Novel revertants of H-ras oncogene-transformed R6-PKC3 cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3117–3129. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.7.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurosawa N, Kanemitsu Y, matsui T, Shimada K, Ishihama H, Muramatsu T. Genomic analysis of a murine cell-surface sialomucin, MGC-24/CD164. Eur J Biochem. 1999;265:466–472. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levesque J P, Zannettino A C, Pudney M, Niutta S, Haylock S N, Snapp K R, Kansas G S, Berndt M C, Simmons P J. PSGL-1-mediated adhesion of human hematopoietic progenitors to P-selectin results in suppression of hematopoiesis. Immunity. 1999;11:369–378. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludolph D C, Konieczny S F. Transcription factor families: muscling in on the myogenic program. FASEB J. 1995;9:1595–1604. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.15.8529839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mellors A, Lo R Y C. O-Sialoglycoprotease from Pasteurella haemolytica. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:728–740. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molkentin J D, Olson E N. Combinatorial control of muscle development by basic helix-loop-helix and MADS-box transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9366–9373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morganstern J P, Land H. Advanced mammalian gene transfer: high titer tetroviral vectors with multiple drug selection markers and a complementary helper-free packaging cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3587–3596. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Podleski T R, Greenberg I. Distribution and activity of endogenous lectin during myogenesis as measured with antilectin antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:1054–1058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.2.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poirier F, Timmons P M, Chan C-T J, Guenet J-L, Rigby P W J. Expression of the L14 lectin during mouse embryogenesis suggests multiple roles during pre- and postimplantation development. Development. 1992;115:143–155. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Redfield A, Nieman M T, Knudsen K A. Cadherins promote skeletal muscle differentiation in three-dimensional cultures. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1323–1331. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Springer T A. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Klinken B J-W, Dekker J, Buller H A, Einerhand A W C. Mucin gene structure and expression: protection vs. adhesion. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:G613–G627. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.5.G613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verfaillie C M. Adhesion receptors as regulators of the hematopoietic process. Blood. 1998;92:2609–2612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watt S M, Chan J Y-H. CD164—a novel sialomucin on CD34+ cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;37:1–25. doi: 10.3109/10428190009057625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wewer U M, Iba K, Durkin M E, Nielsen F C, Loechel F, Gilpin B J, Kuang W, Engvall E, Albrechtsen R. Tetranectin is a novel marker for myogenesis during embryonic development, muscle regeneration, and muscle cell differentiation in vitro. Dev Biol. 1998;200:247–259. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wigler M, Pellicer A, Silverstein S, Axel R. Biochemical transfer of single-copy eucaryotic genes using total cellular DNA as donor. Cell. 1978;14:725–731. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wright W E, Dac-Korytko I, Farmer K. Monoclonal antimyogenin antibodies define epitopes outside the bHLH domain where binding interferes with protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions. Dev Genet. 1996;19:131–138. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1996)19:2<131::AID-DVG4>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yun K, Wold B. Skeletal muscle determination and differentiation: story of a core regulatory network and its content. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:877–889. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zannettino A C W, Buhring H-J, Niutta S, Watt S M, Benton M A, Simmons P J. The sialomucin CD164 (MGC-24v) is an adhesive glycoprotein expressed by human hematopoietic progenitors and bone marrow stromal cells that serves as a potent negative regulator of hematopoiesis. Blood. 1998;92:2613–2628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zeschnigk M, Kozian D, Kuch C, Schmoll M, Starzinski-Powitz A. Involvement of M-cadherin in terminal differentiation of skeletal muscle cells. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:2973–2981. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.9.2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]