Abstract

Purpose of Review.

We conducted a scoping review to evaluate the degree to which literature published within the past five years concerning mental health among Black emerging adult men in the United States engaged with intersectionality.

Methods.

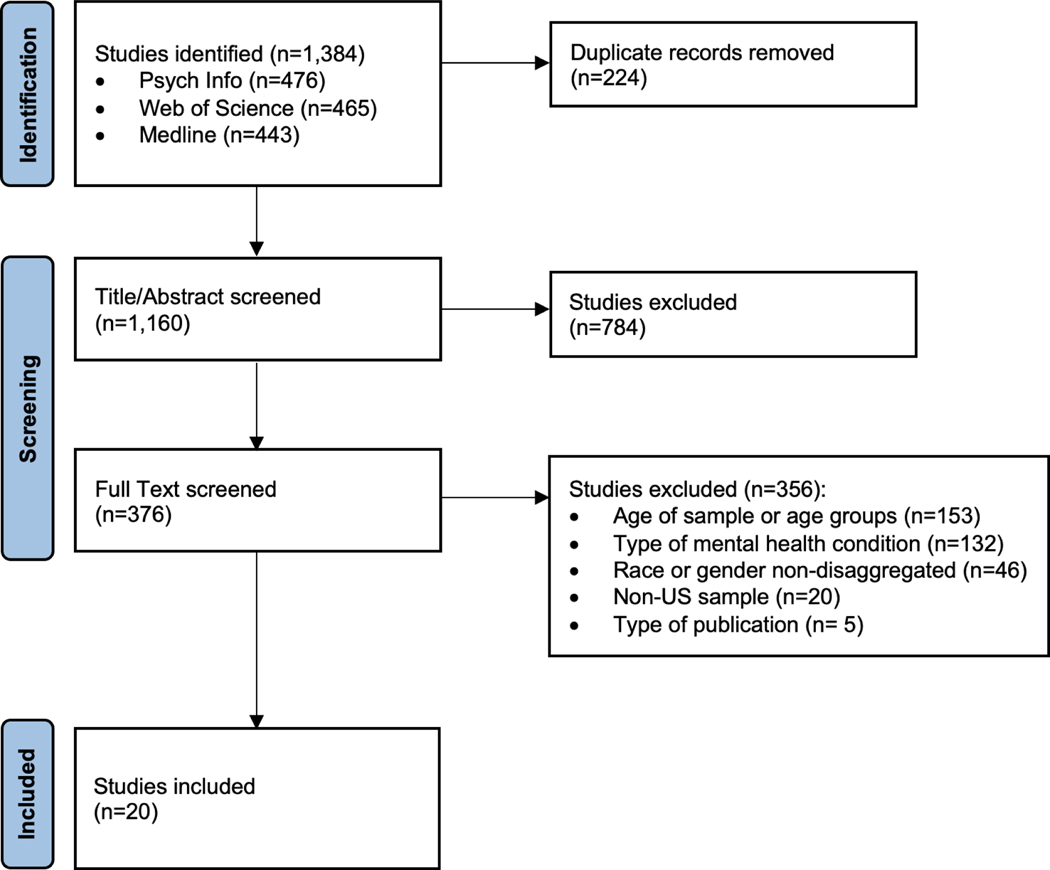

Using Scoping review methods, we applied the following a-priori eligibility criteria: (i) sample included Black/African American men who were aged 18–29 years, (ii) pertained to general mental wellness, depression, or anxiety, (iii) published within between 2017–2022, (iv) empirical and/or theoretical literature including reviews, pre-prints, and reports from organizations or professional groups, (v) conducted in the United States. In total, 1384 studies were identified from the databases, after which 224 duplicates were removed, resulting in 1160 unique citations that were screened in the title/abstract phase. Overall, 376 sources were assessed for full-text eligibility and 20 studies were included for extraction. Information pertaining to sample characteristics, intersectionality, and main mental health results were extracted from the included studies.

Findings.

Findings from this review indicate that there is a paucity of research that has investigated the mental health of Black American, emerging adult men. Of the studies that have been conducted in recent years, there are few that have used an intersectional framework to examine how different social identities intersect to affect mental health.

Summary.

This review underscores that the mental health of emerging adult Black men is of considerable concern given the developmental stage, social and historical context as well as intersecting identities that men in this stage embody.

Keywords: African American, men, intersectionality, mental health, anxiety, depressive symptoms

Introduction

Due to historical and contemporary sociopolitical factors, Black Americans face a myriad of stressors. These stressors are linked to poor health outcomes, including mental conditions such as depression and anxiety [1, 2]. Both depression and anxiety are commonly occurring mental health conditions in the U.S., and depression is the leading global cause of disability [3].

Surprisingly, results from previous research indicate that Black Americans are less likely to be diagnosed with depression compared to White Americans [4•]. These findings are considered paradoxical, given the association between stress and poor mental health, as some scholars describe this phenomenon as the “mental health paradox” [5, 6]. Overall, Black Americans experience greater stress exposure, lower socioeconomic levels, and a disproportionate burden of physical health disparities compared to White Americans but are still less likely to be diagnosed with depression.

Access to mental health care is considered a major factor in the propagation of this paradox as Black Americans are significantly underserved with regard to mental health services [7•-9]. Furthermore, Black men face even more barriers to mental health service utilization, including but not limited to lack of healthcare coverage, mistrust, preferences in care, and transportation issues. Even less is known about the prevalence and impact of commonly occurring mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety among Black American men, especially those considered emerging adults.

Emerging Adulthood and Mental Health among Black Men

Emerging adulthood is the development period in which people transition from adolescence to early adulthood. This period is typically defined as the span between 18–29 years of age and is demographically and developmental distinct [10,11]. This period is characterized by increased independence, autonomy, and engagement in adult responsibilities, which is often stressful. In addition, there are normative societal norms and subjective expectations that individuals are expected to adhere to. For example, emerging adults often establish their independence, craft their identity, complete their educations or professional training, establish their careers or jobs, and start their own families [12, 13]. This period can represent a time for substantial growth, as people take advantage of personal and professional opportunities.

Conversely, this period can be exceptionally challenging, particularly for people who do not have access to stable social support or familial wealth to assist with obtaining independence and stability. Considering these factors, emerging adult Black men represent an important group to explore. Furthermore, emerging adult Black men may be underrepresented in the existing epidemiologic mental health data as they are more likely to be in transition or live in “institutionalized” settings such as college dormitories or military service [14••]. Therefore, these men are often absent from studies that examine community mental health needs. Additionally, emerging adult Black men often lack adequate access to healthcare, so treatment data may not capture their mental health needs [15].

Intersectionality Considerations in Characterizing the Mental Health of Black Men

While there is little known about the mental health of Black American, emerging adult men, data from existing studies [16••, 17] indicate that suicide risk is growing, especially in comparison to other sociodemographic groups. The growing literature about the mental health of this group is of considerable concern because young Black boys and men are in a unique social position that heightens their risk for mental health challenges [18••]. Scholars have implored researchers to explore “marginalized masculinities,” as Black men have been oppressed and overlooked, particularly in previous research [19••-21]. Emerging adult Black men are not only contending with developmental challenges to gain independence; they may be dealing with identity-related stressors such as exposure to racism and norms of masculinity. Intersectionality is a theoretical framework that considers how individual-level social identities intersect with systems of privilege and oppression at the macro-level [22, 23]. Intersectional scholars are interested in examining how multiple identities, including race/ethnicity, gender, and social class, produce health inequities, paying close attention to historical and contemporary contexts as well as social context, and findings from previous research indicate that the interplay of individual-level factors (e.g., race, gender, and socioeconomic status) influence health [24–26]. Additionally, researchers have challenged the field to use intersectionality frameworks to analyze how multiple identities affect mental health [27-28•, 29]. An intersectional approach can provide an appropriate theoretical framework to conceptualize and critically examine how different identity-related experiences coalesce to affect mental health [23, 30, 31].

Rationale

Gaining a better understanding of the mental health challenges that emergent adult Black men face as well as the barriers to mental health services they experience is essential in developing systems and interventions for this population. The goal of this paper was to provide a comprehensive review of mental health among Black emerging adult men in the United States. We used an intersectional framework to critically evaluate the current literature relevant to mental health and emerging adult Black men focusing on recently published studies.

Methods

This review was conducted using a scoping review approach in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [32]. We sought to explore the field of study on mental health among the Black American emerging men population in the United States. Guided by the research question, “What is the current state and evidence of research guided by principles of intersectionality in relation to mental health among emerging adult Black men?” We developed a search strategy to gather a wide section of peer-reviewed sources, including various study types and disciplines.

Search Strategy

We developed a comprehensive search strategy through an iterative process. This included a series of pilot searches in April 2022 to ensure the search results captured the desired concepts: (1) mental health, (2) Black/African American men, and (3) emerging adults. The concept of mental health was limited to general mental health and two commonly occurring disorders in the U.S. population, depression and anxiety. The research team discussed the option to include psychological distress and stress as search terms and was determined to be an appropriate step as previous studies have used the term psychological distress to capture stress, anxiety, and depression.

A source was eligible for inclusion if it met the following a-priori eligibility criteria: (i) sample included Black/African American men (inclusive of multiracial, multiethnic individuals) who were aged 18–29 years, (ii) pertained to general mental wellness, depression, or anxiety, (iii) published within the past five years (2017–2022), (iv) empirical and/or theoretical literature including reviews, pre-prints, and reports from organizations or professional groups, (v) conducted in the United States. Articles were excluded if results were not disaggregated by race and gender. For example, studies using composite data of Black men and Black women without stratifying by gender were excluded. Studies that focused on mental health conditions other than depression and anxiety were excluded (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia). Our team used a systematic database search strategy that utilized a combination of standardized terms, keywords, and Boolean operators in the following databases: APA Psyc Info, Medline, and Web of Science. The search strategy can be found in Appendix B. The search was run on May 5, 2022. Once each search was complete, retrieved sources were uploaded into Covidence [33] to remove duplicates and conduct screening.

Screening and Extraction

Three independent reviewers on our team conducted an initial review of 30 titles and abstracts to remove articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Inter-rater discrepancies from the initial 30 articles screened were resolved by group discussion, and from these conversations, the inclusion/exclusion criteria were refined as appropriate. After the title and abstract screening, the full text of all articles that met the inclusion criteria was reviewed. For both titles/abstracts and full-text reviews, the team reviewed the sources against the eligibility criteria. Eligible sources were extracted for relevant information related to the research question. We extracted information according to general information (e.g., purpose, sample size, setting), research approach, participant characteristics, any measurement for mental health or social identities, results, and evidence of engaging with the intersectionality framework.

Results

Study Selection

In total, 1384 studies were identified from the database search and imported to Covidence, after which 224 duplicates were removed, resulting in 1160 unique citations screened in the title/abstract phase. Next, 376 sources were assessed for full-text eligibility, and 20 studies were included for extraction. Refer to Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow chart.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow chart of the article selection process

Study Characteristics

The majority of studies in this review were quantitative (n=16); there were three qualitative studies and one mixed method. Over half of the included studies were cross-sectional (n=9) with fewer utilizing longitudinal data (n=6). Most studies contained original data (n=8), followed by secondary data analysis (n=6), and then sub-analysis from a larger dataset or project (n=3). Of the 20 studies, 10 employed samples of Black men aged 18–29, and 6 employed samples drawn from a national sample, such as an epidemiological study. Only one study had an entire sample from the northeast region, while the remaining studies were set in the mid-west (n=3) and south (n=7) regions of the U.S. Seven studies contained an entire student sample.

Theory

We examined articles for evidence of intersectionality by first assessing whether any theory or framework was used. Fifteen studies (75%) included a theory or framework guiding their research objectives or findings. Of those reporting a theory or framework, most theories were in the social sciences area, such as stress theories and multi-level models. A minority of studies (n=4) reported using an intersectional perspective or intersectionality framework. Next, among the sources that did not mention intersectionality (n=17), we examined whether the source reflected at least one of the core tenets of intersectionality as outlined by Bowleg [22]. For example, comprehension that participants could have multiple identities, and these identities could be intersecting as opposed to considering social identities from a demographical or unidimensional perspective. This evidence was found in the following sections of the studies: introduction/background, methodology, analysis, and discussion (See Table 1).

Table 1:

Studies according to evidence of intersectionality (n=17)

| Author and publication year | Intro./ Background (n=10, 50%) | Methodsa (n=11, 55%) | Analysis (n=11, 55%) | Discussion (n=12, 60%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Tobin 2022 | ✓ | |||

| Williams 2022 | ✓ | |||

| Wade 2021b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Hussen 2021 | ✓ | |||

| Kogan 2021 | ✓ | |||

| Vincent 2020 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Moore 2020b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Turpin 2020 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lee 2020 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Watkins 2020 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Turpin 2019 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Vu 2019b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Solomon 2020 | ||||

| Wade 2018 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Goodwill 2018b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Hussen 2018 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Bernard 2017 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

Inclusive of studies that conducted secondary analysis.

Study mentioned intersectionality as a guiding theory or framework.

Social Identities

We documented key social categories across the 20 articles into seven categories: 1) race, 2) ethnicity, 3) socioeconomic position, 4) gender identity, 5) gender expression, 6) sexual identity/expression, and 7) other.

Race

Given the focus of this review, all studies documented participants’ racial identities; therefore, we defined this category as a study in which a key area of focus or conceptualization of race directed the development of the study. In total, (n=19, 95%) of the studies met this definition. Two of these articles measured Black Identity [34••, 35•]. Only one of these two studies used an instrument to measure racial identity, the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity. One article measured internalized racism with the Appropriated Racism Oppression Scale [36]. Racial discrimination was measured in a small number of studies (n=5, 25%). The reported measures used for this construct were the following: Daily Life Experience subscale (n=2) [34, 35], Schedule of Racist Events (n=1) [37], author-developed questions (n=1) [38•], and other (n=1) [39••].

Ethnicity

This category represents the studies that recognize the ethnic diversity within the Black population. A total of four articles reported the collection of data related to ethnic identity or attempted to capture ethnicity within the Black diaspora. In one study, participants were allowed to select their ethnicity with the following options: African, Caribbean, Latino, Mixed, and None [40]. In another study, authors mentioned that their sample of African Americans contains ethnic identities, such as origins in Caribbean and African nations, but these data were not presented [41]. Authors of one qualitative investigation sought to examine whether there were differences in respondents based on their families’ ethnicity and immigration status, focusing on how respondents were socialized in African households compared to native-born, Black American households [42••].

Socioeconomic Position

This category was defined as the socially derived economic factors that influence individuals’ position within society. In acknowledgment of the numerous ways researchers can describe and measure socioeconomic position, we used this field to illustrate studies that took distinctive approaches to measure SEP. Two articles created a composite measure, which included multiple factors such as having a college degree, personal income categories, and history of homelessness [39, 43]. One study modified a scale, Chen’s Personal Social Capital Scale, for their participants. Modification entailed the researchers’ changing words, adding items, and conducting cognitive interviews before implementing use of the scale [44]. Participants’ financial situation was collected in Ubesie (2021) with multiple categories. Current financial situation had three categories: financial struggle, tight but fine, and not a problem. A family’s financial situation growing up had four categories: very poor and not enough to get by, had enough to get by, comfortable, and well to do.

Gender identity

Studies obtained gender identity through a mix of methods, including self-identification and records (e.g., medical, educational). The most comprehensive study reported six gender identities within their sample: cisgender man, transgender man, cisgender woman, transgender woman, non-binary (assigned male at birth), and non-binary (assigned female at birth) [41].

Gender expression

We defined gender expression as the way in which an individual expresses or presents their gender identity (e.g., clothing). Of the 20 articles, four considered the gender expression of emerging adult Black men [41, 42, 45•, 46]. Watkins and colleagues (2020) incorporated the measure: Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory to assess participants’ conformity to various hegemonic masculine norms endorsed in dominant American culture.

Sexual identity/expression

Nearly half the studies (n=9) considered the sexual identity of their participants within our sample [36, 38–41, 45, 47]. This category is defined as the participant’s identity regarding whom they are romantically or sexually attracted (e.g., gay, bisexual). Of the 20 studies, six studies (30%) intentionally drew on this identity because the studies were explicitly focused on young Black gay, bisexual, and men who have sex with men (YB-GBMSM) [36, 39, 40, 44, 49, 50]. The majority of these seven studies had participants self-disclosed their sexual identity using the study documents; one study obtained participants’ sexual identity through medical records [50]. Regarding distinctive measures, there was the Mayfield’s Internalized Homonegativity Inventory to measure internalized negative attitudes towards homosexuality and the Revised HIV Stigma scale for youth [44] and the author-developed Racialized Sexual Discrimination Scale [36].

Other

This category aims to identify studies that reflect other possible intersecting social identities, such as one’s physical ability. Two studies highlighted rural settings as a distractive feature for their sample. Two studies collected participants’ history of incarceration and religiosity. The Multidimensional Measure of Religious Involvement was used in one study.

Mental Health

Studies were largely categorized into four areas based on mental health outcomes: 1) positive mental health, 2) physical health, 3) health behavior, and 4) negative mental health. These categories were not mutually exclusive as some studies had more than one goal or ad hoc analysis. Positive mental health was defined as attributes that support mental wellness. Studies that focused on positive mental health (n=6, 30%) included outcomes such as self-esteem, resiliency, and self-worth. Physical health outcomes (n=3) included measures such as sleep and HIV viral load. Health behavior studies (n=9, 45%) included individual-level actions that can influence one’s mental health, including substance use and physical activity. Studies that focused on negative mental health largely focused on depressive symptoms (n=14) as opposed to a sample with diagnosed or documented depression, which was represented in four studies. Both depression and anxiety were of interest in 7 studies. The majority of studies used depression measures that have been widely used in the existing literature with a broad array of study populations and settings, such as the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (n=7and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (n=2).

Summary by Intersecting Social Identities

Race and gender.

Several studies in our review investigated mental health concerns for Black men, focusing on the intersection of race and gender. Tobin (2022) used two epidemiological dataset and found that the Black-White mental health paradox was evident for the 18–29 age group. Black men had as significantly lower odds of any mood disorder (e.g. depression) and any mental disorder related to 18–29 White men. Findings from Ubesie (2021) indicated that Black women college students were more likely to engage in help-seeking behavior compared to Black men. Racial discrimination was found to be associated with depression. Lee et al. (2020) found that different trajectories of perceived racial discrimination during the period of emerging adulthood can adversely influence the psychological well-being of African Americans in adulthood using.

Race, gender, and ethnicity

In Williams et al.’s (2019) qualitative study, African respondents, such as first and second-generation immigrants from Ghana, reported that mental health was not “a thing” within their networks or as they were socialized growing up because of cultural norms. Respondents indicated that poor mental health was considered a sign of weakness or instability. Therefore, men were socialized to suppress their emotions to appear to be strong.

Race, gender, and socioeconomic position

Most studies in our review either controlled for SEP in their analyses or investigated whether SEP is related to mental health. Overall, poorer SEP was associated with a greater risk of depression. In our review, only two studies examined the intersection of race, gender, and SEP for emerging adult Black men. Williams’ qualitative study of 20 Black men who were attending college indicated that money was a significant stressor across all of five focus groups they conducted. Within a sample of YB-GMSM, Turpin and colleagues found a positive correlation between poverty status and depression diagnosis.

Race and gender expression

Three studies used qualitative approaches to examine how social norms intersected with gender expression [41, 42, 46]. Moore and colleagues conducted in-depth interviews to investigate ho, several participants described the simultaneous experience of discrimination on multiple levels. For example, respondents described negative experiences due to the application of racial stereotypes by healthcare providers in addition to negative evaluation if their gender expression conflicted with social norms of masculinity. These experiences were not limited to healthcare encounters or when crossing racial boundaries, as respondents indicated that they were treated differently within the Black community due to their gender expression. Watkins et al. (2020) examined (with Black university attending Black men found that hegemonic norms of masculinity influenced men’s coping strategies on a conscious and subconscious level. For example, findings from their data indicated that participants often hid their emotions or attempted to suppress them. Williams (2022), with 20 college-attending Black men found that many participants identified masculinity as the key reason that precluded them from safe spaces as they did not feel comfortable utilizing social support or sharing feelings related to depression or anxiety.

Race, gender, and sexual identity

Sexual racism or discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation was explored in two studies [38, 41]. In one study Wade and colleagues specifically examined racialized sexual discrimination, also known as sexual racism. Vu (2019), with a sample that contained 106 Black men, used multivariable linear regression to investigate the association between being Black and a sexual minority on depressive symptoms compared to White heterosexual women. Here, they did not identify any statistically significant associations. However, Vincent and colleagues used data drawn from a larger sample of over 1800 Black men and found that higher scores on internalized heterosexism were significantly associated with greater levels of depressive symptoms. In an author-developed scale named Racialized Sexual discrimination, Wade and colleagues, found that the subscales: White superiority, same-race rejection, and White physical objectification were significantly associated with higher rates of depressive symptoms among their sample. An example of an item on this scale is, “How often do you see profiles from White people clearly state that they want to meet other White people?”

Conclusions

The findings from this review should be interpreted with some limitations in mind. This review includes studies in which data were collected more than 15 years old. Additionally, the sample sizes of some studies in the review were small and the geographic sampling for frame for most studies were not reflective of a nationally representative sample of emerging adult Black men. For example, some of the samples included in this review were largely composed of college students. Given the breadth of the mental health literature, we drew tight boundaries in our search. We excluded studies that focused primarily on the experience of discrimination that did not include any mental health data.

Notwithstanding these limitations, findings from our review indicates that there is a paucity of research that has investigated the mental health of Black American, emerging adult men. Of the studies that have been conducted in recent years, there are few that have used an intersectional framework to examine how different social identities (e.g., race/ethnicity, gender, sexual identity, SEP) intersect to affect mental health. Although it is difficult to disentangle the effects of individual-level identities and mental health, such as SEP and race, our review reiterates the significant of doing such work. Using an intersectional lens can promote healthy equity and address health disparities by uncovering nuances, experiences, and barriers entailed for those with intersecting identities in this subpopulation of Black American men.

Due to long-standing, deeply entrenched racial residential segregation, emerging adult Black men’s contexts can be stressful. Exposure to high levels of poverty, crime, and violence is stressful. Findings from several studies in our review showed that access, including healthcare coverage and affordability of care, were formidable barriers to seeking mental healthcare. Additionally, finding from previous literature reveals that there are often identity misalignments that discourage men from seeking mental health treatment. For example, scholars have noted that providers are often White and/or come from a different social class background compared to Black men. This, in turn, decreases the likelihood of men from seeking care or disclosing their emotions and struggles because of perceptions that providers would not be able to understand their lived experiences and perspectives. Residential segregation and concentrated poverty, therefore, increase the risk of poor mental health while truncating the opportunities for coping and treatment for emerging adult Black men.

In addition to these factors, Black men in this group contend with gender-related norms, particularly those related to masculinity. Findings from our review indicate that pressure to conform to standards of masculinity decreases men’s likelihood to seek treatment or even enlist social support within their own social networks. These norms also influence the quality of care that Black men receive when they do seek treatment. For example, findings from Moore, Camacho, & Munson indicated that Black men reported poor treatment from providers, particularly those who were also sexual minorities, or their expression of gender did align with “traditional” heteronormative presentations of masculinity.

This review underscores that the mental health of emerging adult Black men is of considerable concern given the developmental stage, social and historical context as well as intersecting identities that men in this stage embody. Furthermore, there is not enough work that has examined this subpopulation, especially considering the unique stressors that emerging adult Black men experience as well as the social, economic, and structural barriers to mental healthcare. The findings from this study also provide researchers several directions to be pursued in future lines of inquiry. Regarding understanding the mental health paradox among this population, more representative data are needed to investigate whether emerging adult Black men are at greater risk of depression and anxiety compared to their White counterparts.

Additional research is needed to better understand the overall mental health of emerging adult Black men in addition to the unique stressors that this population faces [51]. More research is needed that is grounded in intersectionality, intentionally investigating the interplay of different social identities and the experiences associated with these identities. For example, emerging adult Black men may contend with multiple types of discrimination, including but not limited to race, age, sexual identity, and social class, which as deleterious to health. The consideration of within- group differences regarding ethnicity and immigration status may also yield important observations relevant to research and practice.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

ACA is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health training grant [T32 MH019960-24]. DH is supported by the National Institute of Aging [R01AG074302] and [1R01AG061162-01]

Footnotes

Statements and Declaration: The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Dohrenwend BP. The role of adversity and stress in psychopathology: some evidence and its implications for theory and research. J Health Soc Behav 41, 1–19 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mezuk B, Abdou CM, Hudson D, Kershaw KN, Rafferty JA, et al. “White Box” Epidemiology and the Social Neuroscience of Health Behaviors. Soc Ment Health 3, 79–95 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392, 1789–1858 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson JM, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiat 64, 305–315 (2007). • This article identifies the undertreatment and severity of major depressive disorder among African Americans and Black Caribbeans relative to non-Hispanic whites in the US.

- 5.Barnes DM, Keyes KM, Bates LM. Racial differences in depression in the United States: how do subgroup analyses inform a paradox? Soc Psych Psych Epid 48, 1941–1949 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC et al. Specifying race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in a USA national sample. Psychol Med 36, 57–68 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Neighbors HW, Caldwell C, Williams DR, Nesse R, Taylor RJ, et al. Race, Ethnicity, and the Use of Services for Mental Disorders: Results From the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiat 64, 485–494 (2007). • This article demonstrates the underuse of mental health services among African Americans and Black Caribbeans in the US.

- 8.Brown TH, Hargrove TW. Psychosocial Mechanisms Underlying Older Black Men’s Health. Journals Gerontology Ser B 73, 188–197 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snowden LR. Barriers to Effective Mental Health Services for African Americans. Ment Heal Serv Res 3, 181–187 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnett JJ. Emerging Adulthood. Am Psychol 55, 469–480 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnett JJ, Žukauskienė R, Sugimura K The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 1, 569–576 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sussman S, Arnett JJ. Emerging Adulthood. Eval Health Prof 37, 147–155 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnett JJ, Mitra D. Are the Features of Emerging Adulthood Developmentally Distinctive? A Comparison of Ages 18–60 in the United States. Emerg Adulthood 8, 412–419 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, et al. The National Survey of American Life: a study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. Int J Method Psych 13, 196–207 (2004). • This article outlines the design of the National Survey of American Life, a survey aimed to investigate mental disorders among Black and non-Hispanic whites in the US.

- 15.Metzl JM. Structural Health and the Politics of African American Masculinity. Am J Men’s Heal 7, 68S–72S (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Joe S, Scott ML, Banks A. What Works for Adolescent Black Males at Risk of Suicide. Res Social Work Prac 28, 340–345 (2018). •• This recent review reveals the gap in literature on the risk of suicide for young Black males.

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. https://wisqars.cdc.gov/cgi-bin/broker.exe.

- 18. Staggers-Hakim R The nation’s unprotected children and the ghost of Mike Brown, or the impact of national police killings on the health and social development of African American boys. J Hum Behav Soc Environ 26, 390–399 (2016). •• This study employs focus groups to analyze the impacts police killings on the emotional and psychological wellbeing of young Black boys and men.

- 19. Griffith DM. An intersectional approach to Men’s Health. J Men’s Heal 9, 106–112 (2012). •• This article to provide a framework for studying men’s health with an intersectional framework.

- 20.Griffith DM. “Centering the Margins”: Moving Equity to the Center of Men’s Health Research. Am J Men’s Heal 12, 1317–1327 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffith DM, Ellis KR,Allen JO. An Intersectional Approach to Social Determinants of Stress for African American Men. Am J Men’s Heal 7, 19S–30S (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowleg L The Problem With the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality—an Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health. Am J Public Health 102, 1267–1273 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crenshaw KW. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics and Violence Against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 43, 1241–1299 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudson DL, Neighbors HW, Geronimus AT, Jackson JS. The relationship between socioeconomic position and depression among a US nationally representative sample of African Americans. Soc Psych Psych Epid 47, 373–381 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffith DM. An intersectional approach to Men’s Health. J Men’s Heal 9, 106–112 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warner DF, Brown TH. Understanding how race/ethnicity and gender define age-trajectories of disability: An intersectionality approach. Soc Sci Med 72, 1236–1248 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cole ER. “Intersectionality and Research in Psychology,” Am Psychol, vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 170–180, 2009, doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bauer GR. “Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: challenges and the potential to advance health equity.,” Soc Sci Medicine 1982, vol. 110, pp. 10–7, 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022. • This qualitative study is one the first to examine Black gay and bisexual men’s descriptions and experiences of intersectionality.

- 29.Gilbert KL, Rashawn R, Siddiqi A, Shetty S, Baker E, et al. , “Visible and Invisible Trends in Black Men’s Health: Pitfalls and Promises for Addressing Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Inequities in Health,” Annu Rev Publ Health, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 295–311, 2016, doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowleg L The Problem With the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality—an Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health. Am J Public Health 102, 1267–1273 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowleg L “Once You’ve Blended the Cake, You Can’t Take the Parts Back to the Main Ingredients”: Black Gay and Bisexual Men’s Descriptions and Experiences of Intersectionality. Sex Roles 68, 754–767 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 169, 467–473 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Covidence systematic review software. (Veritas Health Innovation). [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee DB, Anderson RE, Hope MO, Zimmerman MA. Racial discrimination trajectories predicting psychological well-being: From emerging adulthood to adulthood. Dev Psychol 56, 1413–1423 (2020). •• This study examines perceived racial discrimination trajectories and the relationship between these trajectories and mental health outcomes in emerging adulthood for African Americans.

- 35. Bernard DL, Lige QM, Willis HA, Sosoo EE, Neblett EW. Impostor Phenomenon and Mental Health: The Influence of Racial Discrimination and Gender. J Couns Psychol 64, 155–166 (2017). • This study investigates how gender and racial discrimination moderate the impact of imposter phenomenon on mental health in African American college students at predominantly white institutions.

- 36.Wade RM, Bouris AM, Neilands TB, Harper GW. Racialized Sexual Discrimination (RSD) and Psychological Wellbeing among Young Sexual Minority Black Men (YSMBM) Who Seek Intimate Partners Online. Sex Res Soc Policy 1–16 (2021) doi: 10.1007/s13178-021-00676-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kogan SM, Bae D, Cho J, Smith AK, Nishitani S. Pathways linking adverse environments to emerging adults’ substance abuse and depressive symptoms: A prospective analysis of rural African American men. Dev Psychopathol 33, 1496–1506 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vu M, Li J, Haardörfer R, Windle M, Berg CJ. Mental health and substance use among women and men at the intersections of identities and experiences of discrimination: insights from the intersectionality framework. Bmc Public Health 19, 108 (2019). • This study explores the impact of intersecting identities and perceived racial and sexual discrimination on depressive symptoms and substance abuse in men and women.

- 39. Vincent W, Peterson JL, Huebner DM, Storholm ED, Neilands TB, et al. Resilience and Depression in Young Black Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Social-Ecological Model. Stigma Heal 5, 364–374 (2020). •• This study identifies contextual and individual protective factors against depressive symptoms in young Black men who have sex with men.

- 40.Solomon H, Linton SL, del Rio C, Hussen SA. Housing Instability, Depression, and HIV Viral Load Among Young Black Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex With Men in Atlanta, Georgia. J Assoc Nurses Aids Care 31, 219–227 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore KL, Camacho D, Munson MR. Identity negotiation processes among Black and Latinx sexual minority young adult mental health service users. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv 32, 1–28 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Williams KDA, Dougherty SE, Utsey SO, LaRose JG, Carlyle KE. “Could Be Even Worse in College”: Social Factors, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptoms Among Black Men on a College Campus. J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities 1–13 (2022) doi: 10.1007/s40615-022-01302-w. •• This study identifies and analyzes contextual and social risk factors for anxiety and depressive symptoms in Black male undergraduate students.

- 43.Fuller-Rowell TE, Nichols OI, Doan SN, Adler-Baeder F, El-Sheikh M. Changes in Depressive Symptoms, Physical Symptoms, and Sleep-Wake Problems From Before to During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Emerging Adults: Inequalities by Gender, Socioeconomic Position, and Race. Emerg Adulthood 9, 492–505 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hussen SA, Easley KA, Smirth JC, Shenvi N, Harper GW, et al. Social Capital, Depressive Symptoms, and HIV Viral Suppression Among Young Black, Gay, Bisexual and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men Living with HIV. Aids Behav 22, 3024–3032 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Watkins DC, Goodwill JR, Johnson NC, Casanova A, Wei T, et al. An Online Behavioral Health Intervention Promoting Mental Health, Manhood, and Social Support for Young Black Men: The YBMen Project. Am J Men’s Heal 14, 1557988320937215 (2020). • This study reports findings from the Young Black Men, Masculinities and Mental Health project on mental health, masculinity, and social support outcomes for college-aged Black men.

- 46.Goodwill JR, Watkins DC, Johnson NC, Allen JO. An Exploratory Study of Stress and Coping Among Black College Men. Am J Orthopsychiat 88, 538–549 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turpin R, Slopen N, Boekeloo B, Dallal C, Chen S, et al. Testing a Syndemic Index of Psychosocial and Structural Factors associated with HIV Testing among Black Men. J Health Care Poor U 31, 455–470 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turpin R Latent class analysis of a syndemic of risk factors on HIV testing among black men. Aids Care 31, 1–8 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wade R, Harper GW, Bauermeister JA. Psychosocial Functioning and Decisional Balance to Use Condoms in a Racially/Ethnically Diverse Sample of Young Gay/Bisexual Men Who Have Sex with Men. Arch Sex Behav 47, 195–204 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hussen S Mental Health Service Utilization Among Young Black Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men in HIV Care: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Aids Patient Care St 35, 9–14 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hope MO, Taggart T, Galbraith-Gyan KV, Nyhan K Black Caribbean Emerging Adults: A Systematic Review of Religion and Health. J Religion Heal 59, 431–451 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tobin CST, Erving CL, Hargrove TW, Satcher LA. Is the Black-White mental health paradox consistent across age, gender, and psychiatric disorders? Aging Ment Health 1–9 (2022) doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1855627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ubesie A, Wang C, Wang L, Farace E, Jones K, et al. Examining Help-Seeking Intentions of African American College Students Diagnosed with Depression. J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities 8, 475–484 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kogan SM, Cho J, Oshri A, MacKillop J. The influence of substance use on depressive symptoms among young adult black men: The sensitizing effect of early adversity. Am J Addict 26, 400–406 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.