Abstract

The SERPINA1 gene encodes the serine protease inhibitor alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) and is located on chromosome 14q31-32.3 in a cluster of homologous genes likely formed by exon duplication. AAT has a variety of anti-inflammatory properties. Its clinical relevance is best illustrated by the genetic disease alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD) which is associated with an increased risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cirrhosis. While 2 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) , S and Z, are responsible for more than 95% of all individuals with AATD, there are a number of rare variants associated with deficiency and dysfunction, as well as those associated with normal levels and function. Our laboratory has identified a number of novel AAT alleles that we report in this manuscript. We screened more than 500,000 individuals for AATD alleles through our testing program over the past 20 years. The characterization of these alleles was accomplished by DNA sequencing, measurement of AAT plasma levels and isoelectric focusing at pH 4-5. We report 22 novel AAT alleles discovered through our screening programs, such as Zlittle rock and QOchillicothe, and review the current literature of known AAT genetic variants.

Keywords: copd, alpha-1 antitrypsin, genomics, novel alleles, allele characterization, PolyPhen-2

Introduction

The alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) gene (SERPINA1) is located on chromosome 14q31-32.3. This serine protease inhibitor is predominantly produced by hepatocytes,1 but also expressed by macrophages,2 neutrophils,3 monocytes,4 and epithelial cells.5 AAT is synthesized as a single polypeptide chain that undergoes co/post-translational modification which includes a 24 amino acid N-terminal clip and the addition of 3 N-linked glycosylated oligosaccharides to produce the di-, tri-, and tetra-antennary structure.6

AAT is an acute phase reactant protein known for its anti-inflammatory properties. This is demonstrated by increases in AAT levels within hours after inflammation or infection begins. Allelic variations in this genetic disease can lead to deficiency/dysfunction of the AAT protein. The protein may misfold and accumulate in the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes leading to increased susceptibility for development of cirrhosis.7 Since levels of circulating AAT are decreased, less of this molecule can reach the lungs and inhibit neutrophil elastase. The balance of protease to anti-protease is shifted towards lung destruction in deficiency. This is classically seen with the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at earlier ages even with minimal or no tobacco history in affected individuals.8

AAT’s clinical relevance is best demonstrated by the genetic disease alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD) which predisposes individuals to developing COPD and cirrhosis. In the homozygous state, it is associated with development of emphysema at an early age8 and with an increased incidence of hepatitis, usually progressing to cirrhosis.7 There are 2 major alleles, S and Z, which encompass greater than 95% of all known AAT mutations. The S mutation results from the substitution of valine for glutamic acid at amino acid position 264 in exon III (g.9628 A>T). The Z mutation results from the substitution of lysine for glutamic acid at amino acid position 342 in exon V (g.11940 G>A). However, hundreds of mutations exist, including variants associated with normal circulating plasma levels and those associated with deficiency and/or dysfunction.

Our laboratory has identified several novel mutations through our nationwide testing program where we screened more than 500,000 individuals. Individuals with abnormal or ambiguous screening results were invited to join the Alpha-1 Foundation DNA and Tissue Bank and enrolled at their own discretion. The Alpha-1 Foundation DNA and Tissue Bank was established in 2002 and contains approximately 2400 DNA and plasma samples from AATD patients and their families. These individuals were initially screened based on medical indications from liver, lung, or family history that pointed towards a possible diagnosis of AATD. Characterization of novel alleles was accomplished using DNA sequencing, measuring AAT levels in plasma, and isoelectric focusing (IEF) at pH 4–5. Pathogenic variants were determined using PolyPhen-2, a program which estimates the probability that an amino acid change significantly affects protein structure. In this report we characterized 22 alleles discovered at the University of Florida AAT Genetics Laboratory and provide a comprehensive review of known AAT allelic variants.

Material and Methods

Approach to Detection of Abnormal SERPINA1Alleles

The majority of samples were screened for abnormal alleles using dried blood spot cards containing whole blood collected in three 12mM circles on 903 paper. Punches from the 903 Whatman filter paper containing whole blood were used to determine AAT levels by nephelometry. DNA was extracted from the blood spots and genotyped by TaqMan polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers directed to the Z and S alleles. When a sample had a low AAT level inconsistent with the genotype of MZ, SZ, and ZZ, a letter was sent to either the patient or the patient’s physician (depending on the screening program) inviting the individual to join the Alpha-1 Foundation DNA and Tissue Bank and submit a clinical questionnaire and a whole blood sample.

Samples

Genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood samples obtained from participants in the Alpha-1 Foundation DNA and Tissue Bank at the University of Florida, protocol UF-IRB 201500842, after providing written consent. Candidate samples were prescreened and selected for DNA melting, DNA sequencing, or both based on 3 criteria, which, when considered together, suggested the existence of a rare or novel allele. In most cases TaqMan allelic discrimination had to indicate the existence of a non-S or non-Z allele, the AAT protein level had to be lower than 10μM by nephelometry, and IEF had to present an unusual protein migration signature. For melt experiments, DNA concentration was adjusted to 10μg/mL. An M1M1 (rs 6647) sample from the Alpha-1 Foundation DNA and Tissue Bank was used for a control.

Primers

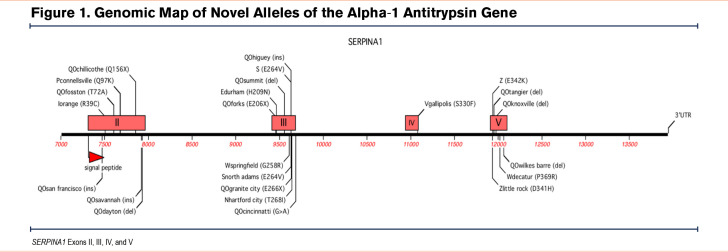

Two different sets of primers were designed for the pre-melt PCR amplifications and pre-sequencing PCR amplifications due to the inability of the melt experiment to accurately detect mutations with high fidelity in amplicons greater than 400 base pairs. Exons II and V were subdivided into 3 and 2 sections, respectively, for the pre-melt amplification (Figure 1). Primers were designed to begin approximately 20 base pairs upstream of intron-exon junctions so splice site mutations, as well as intra-exon mutations, could be identified. We did not routinely screen the promotor regions of the AAT gene for 2 reasons: (1) in our previous sequencing studies of AATD participants we have identified promotor single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) but were unable to attribute any reductions in plasma AAT to the SNPs and, (2) all participants we screened using this approach had SNPs that explained the decreases in plasma AAT, e.g., nonsense mutations, frameshifts, stop codon, and splicing mutations.

Pre-melt PCR

The pre-melt amplification solution included 1 μL of genomic DNA and 9 μL of a PCR master mix that included a Klentaq enzyme and LCGreen Plus (Idaho Technology, Inc., Salt Lake City, Utah). Reaction mixtures were pipetted into opaque black and white 96-well plates with a 20μL mineral oil overlay, sealed with optical adhesive tape and amplified. The PCR had an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 2 minutes, 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds, reannealing at 65°C for 20 seconds, and elongation at 72°C for 15 seconds, followed by a 95°C hold for 30 seconds and a 26°C hold for 30 seconds.

Melt Acquisition

High resolution melt scanning was performed on an Idaho Tech Lightscanner. After completion of PCR amplification, the instrument’s heating block was warmed to a holding temperature of 70°C, at which point the 96-well tray was inserted. Samples were melted within a temperature range of 74°C to 94°C with fluorescence levels measured over the interval.

Melt Analysis

Results were analyzed using the light scanner software package, which presented each melt event as a curve plotted as fluorescence versus temperature. All melt curves corresponding to a single amplicon section were grouped together and normalized by declaring 100% and 0% fluorescence levels at regions before and after the denaturation event. The temperature shift was set to 5% fluorescence. Using the M1M1 control sample as the baseline, the software generated -dF/dT derivative plots that gave steep parabolic curves for samples containing heteroduplexes.

Sanger Sequencing

Exons determined to contain mutations were amplified using in-house sequencing primers. The PCR included an initial denaturation step of 94°C for 1 minute, 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 10 seconds, reannealing at 56°C for 30 seconds, and elongation at 72°C for 1 minute. Sequencing was performed by the UF ICBR sequencing core using an Applied Biosystems Model 3130 Genetic Analyzer or by GeneWiz (South Plainfield, New Jersey). Returned sequences were aligned against National Center for Biotechnology Information-Gene consensus sequences using the MacVector ClustalW/Multiple Sequence Alignment (Apex, North Carolina).

PolyPhen-2

PolyPhen-2 is a program designed to predict the impact of amino acid substitutions on the structure and function of human proteins.9 Position of the variant within the protein, along with the specific amino acid substitution was inputted to determine a score from 0–1 to indicate if the overall protein would be deficient, dysfunctional, normal, or null. A score of 0.8 or greater is considered probably damaging.

Naming

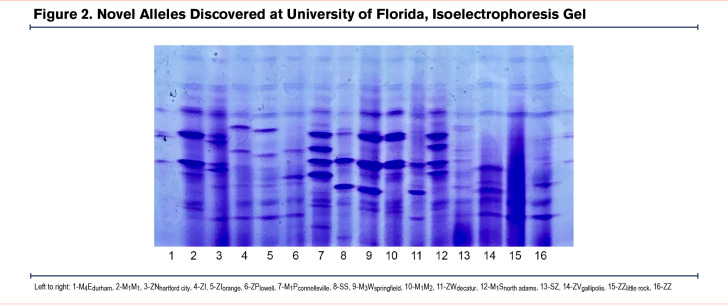

Novel alleles were named according to the birthplace of the individual with the novel variant. Designation of M, Z, S, QO, etc., were implemented based on the pattern of the protein on the IEF gel. Novel alleles were named according to the Human Genome Variation Society and described at the DNA level with the format “position substituted” “reference nucleotide” > “new nucleotide.” The reference transcript does not include the 24 residues of the signal peptide. Much of the variation in AAT variants is based on amino acid substitutions that alter the electrophoretic migration in an IEF gel at pH 4–5. The most common alleles are the M alleles, M1–3, where the differences are based on a combination of SNPs encoding differentially charged amino acids that can be identified by IEF (see example in Figure 2 ). We used M1(val213) as the base allele to compare all variants.

Approach to Literature Review

Construction of tables of known variants of AAT was accomplished by using the search term “alpha-1 antitrypsin” in the PubMed database. The search was accomplished in early 2020 and there were approximately 14,000 articles with the search word in the title and/or abstract. All 14,000 article abstracts and titles available on PubMed were screened for terms indicating a report of novel AAT alleles. Following the identification of these articles the authors reviewed the articles for accuracy and availability of sufficient data to support the variant.

Results

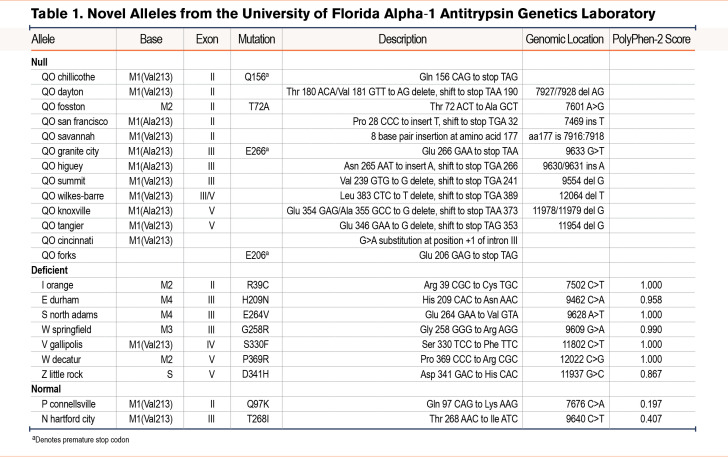

From the Alpha-1 Foundation DNA and Tissue Bank, we identified 22 novel alleles (Figure 1 and Table 1). The majority of these novel alleles were discovered in asymptomatic individuals who underwent genetic testing due to a family history of AATD. Three individuals with novel mutations who presented with pulmonary symptoms at a younger age are discussed in greater detail below.

Iorange

The proband was a 33-year-old female with a history of asthma. She was a non-smoker with a family history of COPD. During initial screening, she was determined to be carrying a Z allele and subsequent DNA sequencing revealed a heterozygous mutation at codon 39 (Arg CGC > Cys TGC) on an M2 (Arg101 CGT > His CAT) background which causes it to run cathodal to the known I mutation by IEF.

QOsan francisco

This patient was a 41-year-old female with a history of hepatitis, asthma, and emphysema. She was on supplemental oxygen and receiving AAT augmentation therapy at the time of sample collection, though she reported a very low plasma level of AAT prior to initiation of augmentation therapy. DNA sequencing appeared to be homozygous for a null allele in exon II (Pro28 CCC, insertion of T, shift to stop TGA 32) though there is a possibility she has a complete deletion of her second AAT allele. The patient had 2 children who were tested at the time, a 16-year-old with a plasma AAT level of 12.8mM and a 7-year-old with a level of 15.4mM, both are heterozygous for this novel null allele.

QOknoxville

The proband was a 57-year-old male with an extensive family history of lung disease, including emphysema, COPD, chronic bronchitis, and asthma. In addition to a Z allele, he was determined to have a novel null allele (a frame shift deletion in exon V resulting in a stop codon at 373). Family testing facilitated by the Alpha-1 Foundation DNA and Tissue Bank showed his son, a 28-year-old with asthma was also heterozygous for this null allele. More family members were screened and a 34-year-old niece of the proband with no active lung disease was found to have the SQOknoxville genotype.

Other Novel Alleles

Because the genetic screening program focused predominately on individuals identified as AAT deficient, the majority of alleles identified represent disease-associated mutations and fall into 2 major categories of AATD: null (n=13) and deficient (n=7). Only 2 normal alleles were identified, Pconnelllsville and Nhartford city (Table 1, Figures 1 and 2). Two of the deficient alleles, Iorange and Snorth adams, show altered IEF migration patterns of the I and S alleles, respectively, and only differ from them with respect to their base alleles which in these novel cases appear on the M2 and M4 backgrounds rather than on the more common M1 background. Electrophoretic differences such as these have previously been reported in the P family of alleles.

Novel deficiency alleles were called “disease associated” based on a PolyPhen-2 score above 0.8 and a clinical history of respiratory and/or liver disease. The molecular mechanisms of abnormal secretion of AAT typically were associated with amino acid substitutions that cause a significant charge alteration, such as a neutral amino acid to a charged amino acid or vice versa. Novel null alleles were most commonly caused by single base deletions and subsequent sequence frameshifts, leading to a premature stop codon. One null allele, QOcincinnati, was the result of a base change in a splice junction in intron III (Figure 1). Two other null mutations were the result of a base substitution that created a stop codon (Figure 1 and Table 1).

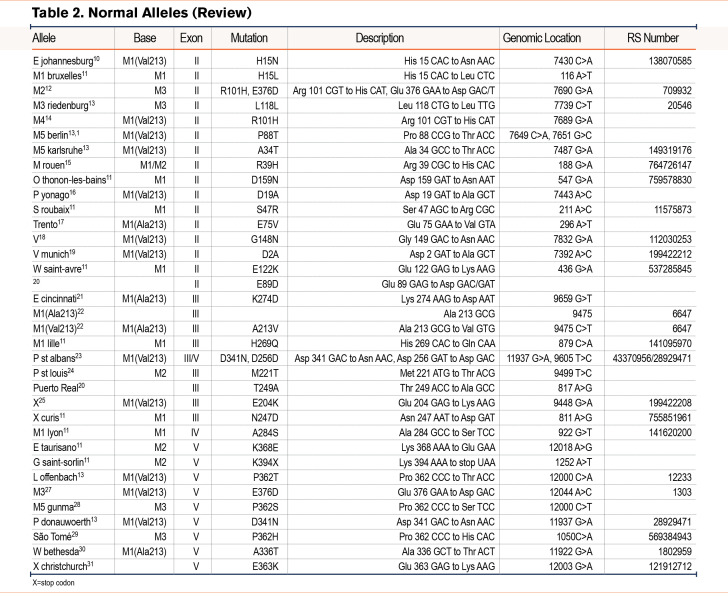

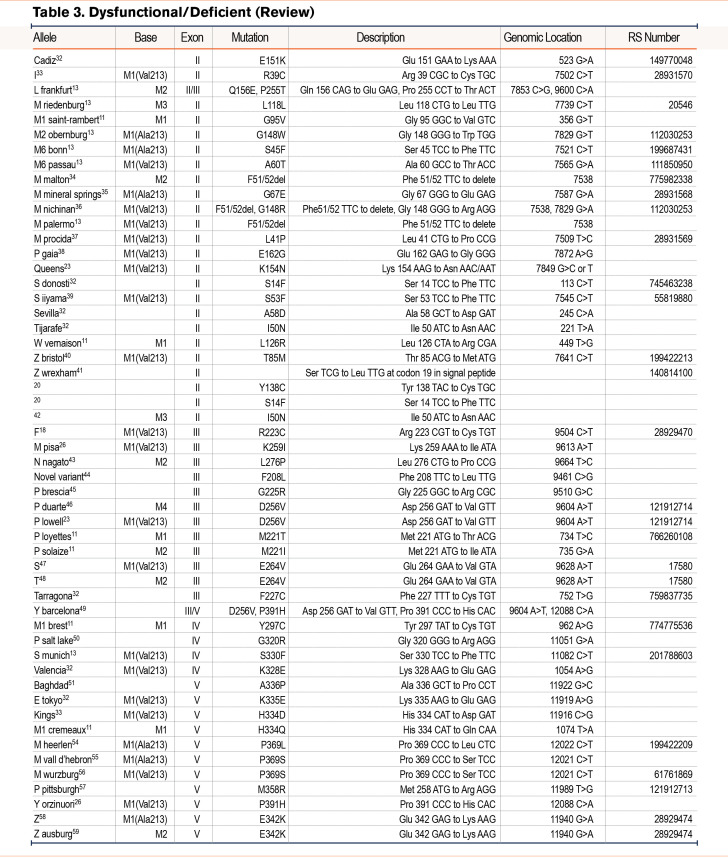

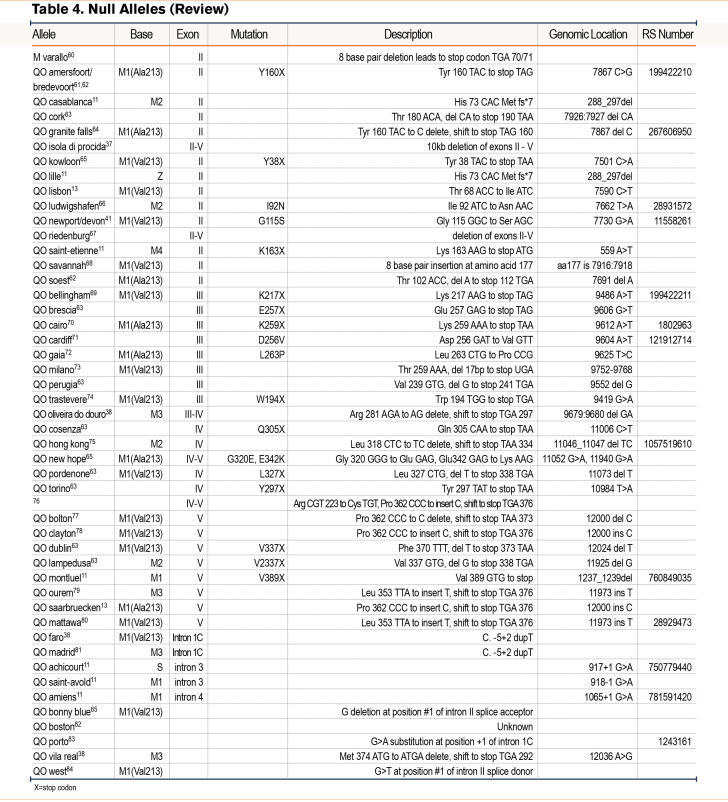

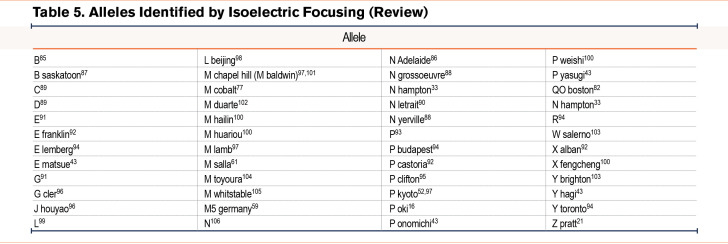

We have grouped known variants into similar categories as the reported novel variants of normal, deficient/dysfunctional, and null variants (Table 2)10-31 (Table 3)32-59 (Table 4).60-84 Alleles listed without a name were discovered via sequencing alone and were not given a name based on their pattern of IEF. We included a table that lists variants that have been identified by IEF and did not have DNA sequencing (Table 5).85-106

Discussion

Our laboratory has been screening individuals for AAT variants for several years using a series of improving and more efficient technologies to simplify the accurate identification of new alleles. In the process, we have identified a number of alleles that provide insight into the molecular basis of AATD-based key relationships between structure and function. While rare deficiency alleles do not play a significant role in the vast majority of AATD individuals, they may play an important role in guiding novel therapies involving chaperones, gene editing, and gene silencing to modulate the consequences of misfolded AAT.

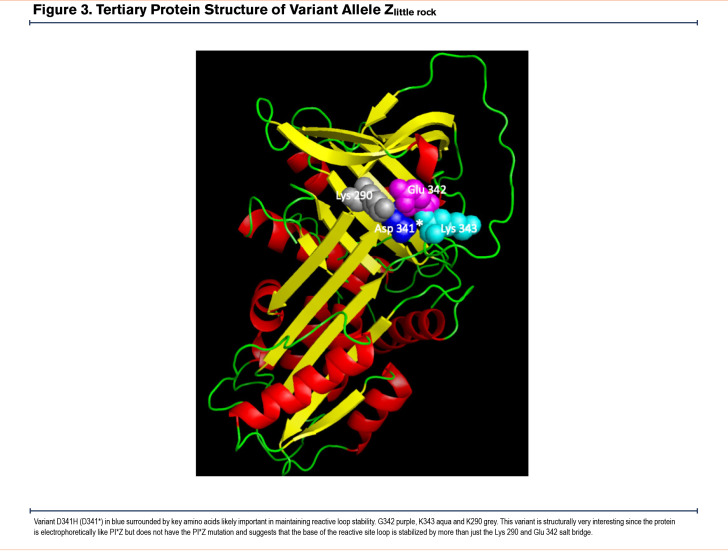

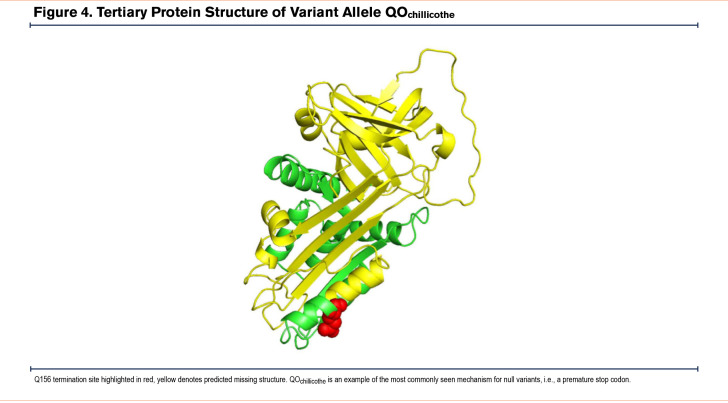

While more than 95% of all disease-affected AATD individuals have severe deficiency due to the presence of the Z allele, novel mutations in the AAT gene provide insight into the key structural elements of the AAT protein. Modeling of Zlittle rock (Figure 3) and QOChillicothe (Figure 4) demonstrate how amino acid changes may create different interactions that alter the structural stability of the protein. These observations have allowed structural biologists to identify key mechanisms of misfolding including the serpin shutter disruption, importance of the C-terminus in structure, and our understanding of the mechanisms of polymerization of variants.107,108

Centers throughout the world devoted to screening for known and novel AAT alleles need to continue their work. While the ease of sequencing DNA has made major leaps, specialized protein analysis and retaining key clinical information of alleles remain very important resources for the AATD community and requires specialists. The Alpha-1 Foundation has been one of the most generous funders of these specialized detection centers. There is much to do before there is a cure for AATD, a condition that affects nearly half a million individuals world-wide. A major step towards developing a cure for AATD includes screening for deficient individuals with informative structural changes and using this information to better understand the structural basis of AATD. As has been said by more than one geneticist, nature through its rich variation has done all the interesting experiments, we just need to determine what we can learn from them.

Abbreviations

Abbreviations: AAT=alpha-1 antitrypsin; AATD= alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IEF=isoelectric focusing; PCR=polymerase chain reaction; SNPs=single nucleotide polymorphisms

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Alpha-1 Foundation.

References

- 1.Brantly M,Nukiwa T,Crystal RG. Molecular basis of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Med. 1988;84(Suppl 6):13-31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(88)80066-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.du Bois RM,Bernaudin JF,Paakko P,Takahashi H,Ferrans V,Crystal RG. Human neutrophils express the alpha-1 antitrypsin gene and produce alpha-1 antitrypsin. Blood. 1991;77(12):2724-2730. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V77.12.2724.2724 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergin DA,Reeves EP,Meleady P,et al. α-1 antitrypsin regulates human neutrophil chemotaxis induced by soluble immune complexes and IL-8. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(12):4236-4250. doi: https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI41196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll TP,Greene CM,O’Connor CA,Nolan AM,O’Neill SJ,McElvaney NG. Evidence for unfolded protein response activation in monocytes from individuals with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. J Immunol. 2010;184(8):4538-4546. doi: https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.0802864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cichy J,Potempa J,Travis J. Biosynthesis of alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor by human lung-derived epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(13):8250-8255. doi: https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.272.13.8250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lechowicz U,Rudzinski S,Jezela-Stanek A,Janciauskiene S,Chorostowska-Wynimko J. Post-translational modifications of circulating alpha-1 antitrypsin protein. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(23):9187. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21239187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell EL,Khan Z. Liver disease in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: current approaches and future directions. Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2017;5:243-252. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40139-017-0147-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayer AS,Stoller JK,Vedal S,et al. Risk factors for symptom onset in PI*Z alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2006;1(4):485-492. doi: https://www.dovepress.com/risk-factors-for-symptom-onset-in-piz-alpha-1-antitrypsin-deficiency-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-COPD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adzhubei I,Jordan DM,Sunyaev SR. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2013;76(1).doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahadeva R,Gaillard M,Pillay V,Halkas A,Lomas D. Characterization of a new variant of alpha-1 antitrypsin EJohannesburg (H15N) in association with asthma. Hum Mutat. 2001;17(2):156. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-1004(200102)17:2<156::AID-HUMU19>3.0.CO;2-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renoux C,Odou M-F,Tosato G,et al. Description of 22 new alpha-1 antitrypsin genetic variants. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13:161. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-018-0897-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frants RR,Eriksson AW. a1-Antitrypsin: common subtypes of Pi M. Hum Hered. 1976;26:435-440. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000152838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faber JP,Poller W,Weidinger S,et al. Identification and DNA sequence analysis of 15 new alpha 1-antitrypsin variants, including two PI*Q0 alleles and one deficient PI*M allele. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55(6):1113-1121. doi: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7977369/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Constans J,Viau M,Gouaillard C. Pi M4: an additional Pi M subtype. Hum Genet. 1980;55:119-121. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00329137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin JP,Sesboue R,Charlionet R,Ropartz C. Does alpha-1-antitrypsin PI null phenotype exist? Humangenetik. 1975;30:121-125. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00291944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuasa I,Okada K. A new a1-antitrypsin allele PI*Poki: isoelectric focusing with immobilized pH gradients as a tool for identification for PI variants. Hum Genet. 1985;70:333-336. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00295372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miranda E,Ferrarotti I,Berardelli R,et al. The pathological Trento variant of alpha-1-antitrypsin (E75V) shows nonclassical behaviour during polymerization. FEBS J. 2017;284(13):2110-2126. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.14111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fagerhol MK,Laurell CB. The polymorphism of 'prealbumins' and a1-antitrypsin in human sera. Clin Chim Acta. 1967;16(20):199-203. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-8981(67)90181-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes MD,Brantly ML,Curiel DT,Weidinger S,Crystal RG. Characterization of the normal alpha 1-antitrypsin allele Vmunich: a variant associated with a unique protein isoelectric focusing pattern. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;46(4):810-816. doi: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2316526/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matamala N,Gomez-Mariano G,Martinez S,et al. Molecular characterization of novel PiS-like alleles identified in Spanish patients with Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(Suppl 62):PA936. doi: https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.congress-2018.PA936 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hug G,Chuck G,Slemmer TM,Fagerhol MK. Pi Ecincinnati: a new alpha1-antitrypsin allele in three negro families. Hum Genet. 1980;54:361-364. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00291583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nukiwa T,Satoh K,Brantly ML,et al. Identification of a second mutation in the protein-coding sequence of the Z type alpha 1-antitrypsin gene. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(34):15989-15994. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)66664-5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes MD,Brantly ML,Crystal RG. Molecular analysis of the heterogeneity among the P-family of alpha-1-antitrypsin alleles. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142(5):1185-1192. doi: https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm/142.5.1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pierce JA,Eradio B. MPsaintlouis: a new antitrypsin phenotype. Hum Hered. 1981;31(1):35-38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000153173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Axelsson U,Laurell CB. Hereditary variants of serum alpha-1-antitrypsin. Am J Hum Genet. 1965;17(6):466-472. doi: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4158556/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fra AM,Gooptu B,Ferrarotti I,et al. Three new alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency variants help to define a C-terminal region regulating conformational change and polymerization. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e38405. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Genz T,Martin JP,Cleve H. Classification of a1-antitrypsin (Pi) phenotypes by isoelectrofocusing. Distinction of six subtypes of the PiM phenotype. Hum Genet. 1977;38:325-332. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00402159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuasa I,Umetsu K,Ago Kazutoshi,Iijima K,Nakagawa M,Irizawa Y. Molecular characterization of four alpha-1-antitrypsin variant alleles found in a Japanese population: a mutation hot spot at the codon for amino acid 362. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2001;3(4):213-219. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1344-6223(01)00040-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seixas S,Trovoada MJ,Santos MT,Rocha J. A novel alpha‐1‐antitrypsin P362H variant found in a population sample from São Tomé e Príncipe (Gulf of Guinea, West Africa). Hum Mutat. 1999;13(5):414. doi: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/%28SICI%291098-1004%281999%2913%3A5%3C414%3A%3AAID-HUMU19%3E3.0.CO%3B2-%23 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crystal RG. Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency, emphysema, and liver disease. Genetic basis and strategies for therapy. J Clin Invest. 1990;85(5):1343-1352. doi: https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI114578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brennan SO,Carrell RW. a1-Antitrypsin Christchurch, 363 Gluà lys: mutation at the P'5 position does not affect inhibitory activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;873(1):13-19. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4838(86)90183-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matamala N,Lara B,Gomez-Mariano G,et al. Characterization of novel missense variants of SERPINA1 gene causing alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2018;58(6):706-716. doi: https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2017-0179OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnaud P,Chapuis-Cellier C,Vittoz P,Fudenberg HH. Genetic polymorphism of serum alpha-1-protease inhibitor (alpha-1 antitrypsin): Pi i, a deficient allele of the Pi system. J Lab Clin Med. 1978;92(2):177-184. doi: https://www.translationalres.com/article/0022-2143(78)90046-X/fulltext [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cox D W. A new deficiency allele of alpha-1antitrypsin: Pi Mmalton In: Peeters H, ed. Protides of Biological Fluids, Proceedings of the 23rd Colloquium Brugge, 1975.Pergamon Press Ltd;. 1976:375-378.

- 35.Curiel DT,Vogelmeier C,Hubbard RC,Stier LE,Crystal RG. Molecular basis of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and emphysema associated with the alpha-1 antitrypsin Mmineral springs allele. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10(1):47-56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.10.1.47-56.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakamura H,Ogawa H,Kuno S,Fukuma M,Hashi N,Tsuda K. A family with a new deficient variant of alpha-1 antitrypsin PiMnichinan--with special reference to diastase-resistant, periodic acid-Schiff positive globules in the liver cells. [in Japanese]. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 1980;69(8):967-974. doi: https://doi.org/10.2169/naika.69.967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi H,Crystal RG. Alpha-1 antitrypsin null (isola di procida): an alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency allele caused by deletion of all alpha-1 antitrypsin coding exons. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;47(3):403-413. doi: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1683852/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva D,Oliveira MJ,Guimaraes M,Lima R,Gomes S,Seixas S. Alpha-1 antitrypsin (SERPINA1) mutation spectrum: three novel variants and haplotype characterization of rare deficiency alleles identified in Portugal. Respir Med. 2016;116:8-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2016.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seyama K,Nukiwa T,Takabe K,Takahashi H,Miyake K,Kira S. Siiyama (serine 53 (TCC) to phenylalanine 53 (TTC)). A new alpha-1 antitrypsin-deficient variant with mutation on a predicted conserved residue of the serpin backbone. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(19):12627-12632. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)98945-3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lovegrove JU,Jeremiah S,Gillett GT,Temple K,Povey S,Whitehouse DB. A new alpha-1 antitrypsin mutation, Thr-Met 85, (PI Zbristol) associated with novel electrophoretic properties. Ann Hum Genet. 1997;61(5):385-391. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-1809.1997.6150385.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Graham A,Kalsheker NA,Bamforth FJ,Newton CR,Markham AF. Molecular characterisation of two alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency variants: proteinase inhibitor (Pi) NullNewport (Gly115----Ser) and (Pi) Z Wrexham (Ser-19----Leu). Hum Genet. 1990;85:537-540. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00194233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carpagnano GE,Santacroce R,Palmiotti GA,et al. A new SERPINA-1 missense mutation associated with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and bronchiectasis. Lung. 2017;195:679-682. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-017-0033-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuasa I,Suenaga K,Gotoh Y,Ito K,Yokoyama N,Okada K. PI (alpha-1 antitrypsin) polymorphism in the Japanese: confirmation of PI*M4 and description of new PI variants. Hum Genet. 1984;67:209-212. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00273002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Seynes C,Ged C,de Verneuil H,Chollet N,Balduyck M,Raherison C. Identification of a novel alpha-1 antitrypsin variant. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;20:64-67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmcr.2016.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Medicina D,Montani N,Fra AM,et al. Molecular characterization of the new defective Pbrescia alpha-1 antitrypsin allele. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(8):E771-781. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.21043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hildesheim J,Kinsley G,Bissell M,Pierce J,Brantly M. Genetic diversity from a limited repertoire of mutations on different common allelic backgrounds: alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency variant Pduarte. Hum Mutat. 1993;2(3):228. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.1380020311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fagerhol MK. Serum Pi types in Norwegians. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1967;70(3):421-428. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1699-0463.1967.tb01310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kühnl P,Spielmann W. PiT: a new allele in the alpha-1 antitrypsin system. Hum Genet. 1979;50:221-223. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00390245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jardi R,Rodriguez F,Miravitlles M,et al. Identification and molecular characterization of the new alpha-1 antitrypsin deficient allele PI Ybarcelona (Asp256-->Val and Pro391-->His). Mutations in brief no. 174. Online. Hum Mutat. 1998;12(3):213. doi: https://europepmc.org/article/med/10651487 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bornhorst JA,Calderon FRO,Procter M,Tang W,Ashwood ER,Mao R. Genotypes and serum concentrations of human alpha-1 antitrypsin 'P' protein variants in a clinical population. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1124-1128. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2006.042762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haq I,Irving JA,Saleh AD,et al. Deficiency mutations of alpha-1 antitrypsin. Effects on folding, function, and polymerization. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54:71-80. doi: https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2015-0154OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyake Suzuki H,Oka H,Oda T,Harada S. Distribution ofα1 phenotypes in Japanese: Description of Pi M subtypes by isoelectric focusing. Jap J Human Genet. 1979;24:55-62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01888921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miranda E,Perez J,Ekeowa UI,et al. A novel monoclonal antibody to characterize pathogenic polymers in liver disease associated with alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Hepatology. 2010;52(3):1078-1088. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kramps JA,Brouwers J W,Maesen F,Dijkman JH. PiMheerlen, alpha PiM allele resulting in very low alpha-1 antitrypsin serum levels. Hum Genet. 1981;59:104-107. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00293055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jardi R,Rodriguez-Frias F,Lopez-Talavera JC,et al. Characterization of the new alpha-1 antitrypsin-deficient PI M-type allele, PI Mvalld'hebron (Pro369-->Ser). Hum Hered. 2000;50:320-32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000022935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Poller W,et al. Molecular characterisation of the defective alpha-1 antitrypsin alleles PI Mwurzburg(Pro369Ser), Mheerlen (Pro369Leu), and Q0lisbon (Thr68Ile). Eur J Hum Genet. 1999;7:321-331. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Owen MC,Brennan SO,Lewis JH,Carrell RW. Mutation of antitrypsin to antithrombin. Alpha-1 antitrypsin Pittsburgh (358 Met leads to Arg), a fatal bleeding disorder. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:694-698. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198309223091203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laurell C-B,Eriksson S. The electrophoretic α1-globulin pattern of serum in α1-antitrypsin deficiency. COPD. 2013;10(Suppl 1):3-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.3109/15412555.2013.771956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weidinger S,Jahn W,Cujnik F,Schwarzfischer F. Alpha-1 antitrypsin: evidence for a fifth PI M subtype and a new deficiency allele PI*ZAugsburg. Hum Genet. 1985;71:27-29. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00295662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coni P,Pili E,Convertino G,et al. MVarallo: a new M(Like) alpha-1 antitrypsin-deficient allele. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2003;12(4):237-239. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/00019606-200312000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fregonese L,Stolk J,Frants RR,Veldhuisen B. Alpha-1 antitrypsin null mutations and severity of emphysema. Respir Med. 2008;102(6):876-884. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2008.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prins J,van der Meijden BB,Kraaijenhagen RJ,Wielders JPM. Inherited chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: new selective-sequencing workup for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency identifies 2 previously unidentified null alleles. Clin Chem. 2008;54(1):101-107. doi: https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2007.095125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ferrarotti I,Carroll TP,Ottaviani S,et al. Identification and characterisation of eight novel SERPINA1 null mutations. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:172. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-014-0172-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nukiwa T,Takahashi H,Brantly M,Courtney M,Crystal RG. Alpha-1 antitrypsin nullGranite Falls, a nonexpressing alpha-1 antitrypsin gene associated with a frameshift to stop mutation in a coding exon. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(25):11999-12004. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)45309-4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee JH,Brantly M. Molecular mechanisms of alpha-1 antitrypsin null alleles. Respir Med. 2000;94(Suppl C):S7-11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1053/rmed.2000.0851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frazier GC,Siewertsen MA,Hofker MH,Brubacher MG,Cox DW. A null deficiency allele of alpha-1 antitrypsin, QOludwigshafen, with altered tertiary structure. J Clin Invest. 1990;86(6):1878-1884. doi: https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI114919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Poller W,Faber J-P,Weidinger S,Olek K. DNA polymorphisms associated with a new alpha-1 antitrypsin PIQ0 variant (PIQ0riedenburg). Hum Genet. 1991;86:522-524. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00194647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brantly M,Schreck P,Rouhani FN,et al. Rare and novel alpha-1 antitrypsin alleles identified through the University of Florida-Alpha-1 Foundation DNA Bank. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:A3506. doi: https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2009.179.1_MeetingAbstracts.A3506 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Satoh K,Nukiwa T,Brantly M,et al. Emphysema associated with complete absence of alpha-1 antitrypsin in serum and the homozygous inheritance [corrected] of a stop codon in an alpha-1 antitrypsin-coding exon. Am J Hum Genet. 1988;42(1):77-83. doi: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3257351/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zorzetto M,Ferrarotti I,Campo I,et al. Identification of a novel alpha-1 antitrypsin null variant (Q0Cairo). Diagn Mol Pathol. 2005;14(2):121-124. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pas.0000155023.74859.d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bamforth FJ,Kalsheker NA. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency due to Pi null: clinical presentation and evidence for molecular heterogeneity. J Med Genet. 1988;25(2):83-87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/jmg.25.2.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oliveira MJ,Seixas S,Ladeira I,et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency caused by a novel mutation (p.Leu263Pro): Pi*ZQ0gaia - Q0gaia allele. Rev Port Pneumol. 2015;21(6):341-343. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rppnen.2015.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rametta R,Nebbia G,Dongiovanni P,Farallo M,Fargion S,Valenti L. A novel alpha-1 antitrypsin null variant (PiQ0Milano). World J Hepatol. 2013;5(8):458-461. doi: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3767846/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee J,Novoradovskaya N,Rundquist B,Redwine J,Saltini C,Brantly M. Alpha-1 antitrypsin nonsense mutation associated with a retained truncated protein and reduced mRNA. Mol Genet Metab. 1998;63(4):270-280. doi: https://doi.org/10.1006/mgme.1998.2680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sifers RN,Brashears-Macatee S,Kidd VJ,Muensch H,Woo SLA. Frameshift mutation results in a truncated alpha-1 antitrypsin that is retained within the rough endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1988;263(15):7330-7335. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)68646-6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ringenbach MR,Banta E,Snyder MR,Craig TJ,Ishmael FT. A challenging diagnosis of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: identification of a patient with a novel F/Null phenotype. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2011;7:18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1710-1492-7-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fraizer GC,Siewertsen M,Harrold TR,Cox DW. Deletion/frameshift mutation in the alpha-1 antitrypsin null allele, PI*QObolton. Hum Genet. 1989;83:377-382. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00291385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brantly M,Lee JH,Hildesheim J,et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin gene mutation hot spot associated with the formation of a retained and degraded null variant [corrected; erratum to be published]. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;16(3):225-231. doi: https://doi.org/10.1165/ajrcmb.16.3.9070606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vaz Rodrigues L,Costa F,Marques P,Mendonca C,Rocha J,Seixas S. Severe α-1 antitrypsin deficiency caused by Q0Ourém allele: clinical features, haplotype characterization and history. Clin Genet. 2012;81(5):462-469. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01670.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cox DW,Levison H. Emphysema of early onset associated with a complete deficiency of alpha-1 antitrypsin (null homozygotes). Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137(2):371-375. doi: https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm/137.2.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lara B,Martinez MT,Blanco I,et al. Severe alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency in composite heterozygotes inheriting a new splicing mutation QOMadrid. Respir Res. 2014;15:125. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-014-0125-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Talamo RC,Langley CE,Reed CE,Makino S. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: a variant with no detectable alpha-1 antitrypsin. Science. 1973;181(4094):70-71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.181.4094.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Seixas S,Mendonça C,Costa F,Rocha J. Alpha-1 antitrypsin null alleles: evidence for the recurrence of the L353fsX376 mutation and a novel G-->A transition in position +1 of intron IC affecting normal mRNA splicing. Clin Genet. 2002;62(2):175-180. doi: https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.620212.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Laubach VE,Ryan WJ,Brantly M. Characterization of a human alpha-1 antitrypsin null allele involving aberrant mRNA splicing. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2(7):1001-1005. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/2.7.1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Martin JP,Vandeville D,Ropartz C. PiB, a new allele of alpha-1 antitrypsin genetic variants. Biomedicine. 1973;19(9):395-398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mulley JC,Cox DW,Sutherland GR. A new allele of alpha-1 antitrypsin: PI NADELAIDE. Hum Genet. 1983;63:73-74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00285402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Horne SL,Tennent RK,Cockcroft DW. A new anodal alpha-1 antitrypsin variant associated with emphysema: Pi Bsaskatoon. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;125(5):594-600. doi: https://doi.org/10.1164/arrd.1982.125.5.594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sesboüé R,Vercaigne D,Charlionet R,Lefebvre F,Martin JP. Human alpha-1 antitrypsin genetic polymorphism: PI N subtypes. Hum Hered. 1984;34:105-113. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000153444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Robinet-Lévy M,Rieunier M. Method for the identification of Pi groups. 1st statistics from Languedoc [French]. Rev Fr Transfus. 1972;15(1):61-72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0035-2977(72)80029-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Charlionet R,Sesboüe R,Morcamp C,Lefebvre F,Martin JP. Genetic variations of serum alpha-1 antitrypsin (Pi types) in Normans. Common Pi M subtypes and new phenotypes. Hum Hered. 1981;31:104-109. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000153187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fagerhol MK. Genetics of the Pi system. In: Mittman C, ed. Pulmonary Emphysema and Proteolysis. 1972;123:-131. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cox DW,Smyth S,Billingsley G. Three new rare variants of alpha-1 antitrypsin. Hum Genet. 1982;61:123-126. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00274201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fagerho MK,Hauge HE. The Pi phenotype MP. Discovery of a ninth allele belonging to the system of inherited variants of serum alpha-1 antitrypsin. Vox Sang. 1968;15(5):396-400. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1423-0410.1968.tb04081.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cox DW. New variants of alpha-1 antitrypsin: comparison of Pi typing techniques. Am J Hum Genet. 1981;33(3):354-365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hug G,Chuck G,Fagerhol MK. PiPclifton: a new alpha 1-antitrypsin allele in an American Negro family. J Med Genet. 1981;18(1):43-45. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/jmg.18.1.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Plazonnet MP,Constans J,Mission G,Gentou C. Familial alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency with Pi-Z and a new Pi-Gcler variant. Biomedicine. 1980;33:86-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cox DW,Johnson AM,Fagerhol MK. Report of Nomenclature Meeting for alpha-1 antitrypsin, INSERM, Rouen/Bois-Guillaume-1978. Hum Genet. 1980;53:429-433. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00287070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ying QL,Liang CC,Zhang ML. PI*LBEI and PI*JHOU: two new alpha-1 antitrypsin alleles. Hum Genet. 1984;68:48-50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00293870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vandeville D,Martin JP,Ropartz C. Alpha-1 antitrypsin polymorphism of a Bantu population: description of a new allele PiL. Humangenetik. 1974;21:33-38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00278562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ying QL,Mei-lin Z,Chih-chuan L,et al. Geographical variability of alpha-1 antitrypsin alleles in China: a study on six Chinese populations. Hum Genet. 1985:69:184-187. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00293295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Johnson AM. Genetic typing of alpha-1 antitrypsin by immunofixation electrophoresis, identification of subtypes of Pi M. J Lab Clin Med. 1976;87(1):152-163. doi: https://www.translationalres.com/article/0022-2143(76)90340-1/fulltext [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lieberman J,Gaidulis L,Klotz SD. A new deficient variant of alpha-1 antitrypsin (MDUARTE). Inability to detect the heterozygous state by antitrypsin phenotyping. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;113(1):31-36. doi: https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1164/arrd.1976.113.1.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cook PJ. The genetics of alpha-1antitrypsin: a family study in England and Scotland. Ann Hum Genet. 1975;38(3):275-287. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1809.1975.tb00611.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yuasa I,Suenaga K,Umetsu K,et al. PI Mtoyoura: a new PI M subtype found by separator and hybrid isoelectric focusing. Electrophoresis. 1988;9:151-153. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/elps.1150090311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ambrose HJ,Chambers SM,Mieli-Vergani G,Ferrie R,Newton CR,Robertson NH. Molecular characterization of a new alpha-1 antitrypsin M variant allele, Mwhitstable: implications for DNA-based diagnosis. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1999;8(4):205-210. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/00019606-199912000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cox DW,Celhoffer L. Inherited variants of alpha-1 antitrypsin: a new allele PiN. Can J Genet Cytol. 1974;16(2):297-303. doi: https://doi.org/10.1139/g74-033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lomas DA,Carrell RW. Serpinopathies and the conformational dementias. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:759-768. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Knause KJ,Morillas M,Swietnicki W,Malone M,Surewicz WK,Yee VC. Crystal structure of the human prion protein reveals a mechanism for oligomerization. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:770-774. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nsb0901-770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]