Abstract

The novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak exerted a serious effect on healthcare. Between 1st of January and May 31, 2020 due to the special regulations in Hungary, the number of reported COVID-19 infections were relatively low (3876 cases). The inpatient and outpatient care and the blood supply were significantly affected by the implemented regulations. The aim of this study was to evaluate the use of blood products amid the first five months of the pandemic situation. This investigation has observed a significant reduction of hospitalizations (37.35%). Analyzing individually the included units, pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentrations of transfused patients presented slight modifications, which were not statistically significant. The special regulations resulted major changes in the frequency of diagnoses at admissions in case of the Department of Surgery, while in case of the other specialities (Division of Hematology and Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Therapy), there were no major changes compared to pre-pandemic period. Considering each department separately, transfused red blood cell concentrates (RBC) per patient, and the proportion of transfused patients did not change significantly. However, the combination of these modifications resulted in the significant decrease in RBC transfusions (p < 0.0001) compared to the pre-pandemic baseline. With regard to platelet and fresh frozen plasma (FFP), their usage was significantly reduced (44.40% platelet concentrates and 34.27% FFP). Our results indicate that the pandemic had an important effect on the blood product usage at the included departments by introducing different patient care policies and the temporary deferral of the elective surgical interventions. Despite the challenging circumstances of blood collection and blood product supply, the hospitalized patients received adequate care.

Keywords: COVID-19 and blood product usage, Blood components, Restrictive transfusion policy, Patient blood management, Pre-transfusion hemoglobin

1. Introduction

Infections with the emerging coronavirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) can lead to the development of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19 – named by World Health Organization - WHO - on February 11th, 2020) [1]. WHO has declared the COVID-19 outbreak as a pandemic on March 11th, 2020 [[1], [2], [3], [4]].

To prevent the uncontrolled spreading of the virus, the Hungarian Government established the operative board with its principal aim of analysis and evaluation of the coronavirus-pandemic and the definition of new recommendations [5]. According to the recommendations of the operative board in charge, non-emergency inpatient healthcare was temporarily banned. In addition, before the hospitalization of the patients, the mandatory coronavirus molecular testing (real-time polymerase chain reaction – RT - PCR) was also introduced [6,7]. These modifications have also had a significant influence on blood demand. In other countries, due to the temporary ban of elective surgical interventions transfusion demand decreased at around 10–40% [8,9].

The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control established indications regarding the supply of substances of human origin. Therefore, alongside other European countries, Hungary implemented special rules and recommendations that aimed to prevent transmission of the novel coronavirus infection through transfusion, despite the lack of evidence about the possibility of blood-borne transmission [10]. The measures to prevent unnecessary commuting of the novel coronavirus infections, have led to challenges in organizing a safe blood donation. Thus, blood product supply for safe and effective patient care became even more difficult.

Studies are currently in progress to find evidence-based guides for optimal management of the blood product transfusion. Patient Blood Management is a recently evolved multidisciplinary approach based on a series of evidence-based medical and surgical directives to improve patient outcomes. Three pillars of patient blood management have been conceptualized, which are (I) the optimization of patient's red blood cell mass, (II) reduction of perioperative blood loss and (III) enhancement of physiological anemia tolerance [11]. Thus, Patient Blood Management reduces the transfusion rate and eventually increases blood product reserve [12,13].

The Janus Pannonius Clinical Building (JPCB) is part of the Clinical Centre of the University of Pécs, containing the Departments and Clinics with the highest blood demand. The Clinical Transfusion Service stores and issues labile blood products for different departments of the JPCB. The average number of monthly handled blood components is generally about 1600 units.

2. Aim

The purpose of our retrospective and descriptive study is the assessment of the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use of blood product in the JPCB supplied by the Clinical Transfusion Service.

3. Materials and methods

The data was acquired from the TraceLine blood product tracking system's database used by the Clinical Transfusion Service, between January 1st, 2020, and May 31st, 2020, regarding the blood product usage from three clinical departments: 1st Department of Medicine (Division of Hematology), Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Therapy and the Department of Surgery. The patients were split into two groups based on the date of hospitalization. The first day after Hungary's emergency healthcare situation was declared was March 11th, 2020. Two time intervals have been compared, the first time interval lasted between 1st of January 2020 and 15th of March 2020 and the second interval comprised the period from 16th of March 2020 to 31st of May 2020. We evaluated the mean weekly patient hospitalizations and statistically analyzed the differences of the two groups regarding the weekly average number of patients, transfusion rates, and red blood cell usage. We also recorded the pre-transfusion hemoglobin (Hb) concentrations in the case of 691 patients and the diagnoses at the moment of admission in the case of 1932 discharged patients.

Microsoft Excel™ software was used to analyze the collected data. The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 26 and Microsoft Excel™. Independent samples t-test was performed to assess differences between our set of data in case of normal distribution, and Mann Whitney test was performed in case of not normally distributed data. This study has been approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Pécs (8349/PTE2020).

4. Results

Our study included a total number of 2238 hospitalized patients. 19.61% of the inpatients needed transfusion, with 1442 red blood cell concentrates (RBCs) used. Their pre-transfusion mean hemoglobin concentration was 74.05 g/dL (min: 15.00; max: 117). Additionally, 473 thrombocyte concentrates, and 411 fresh frozen plasma (FFP) units have been transfused in the analyzed period (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of data related to inpatients, used blood products and inpatient pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentrations.

| Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Therapy | Division of Hematology | Department of Surgery | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First period | Hospitalizations (n) | 183 | 317 | 876 | 1376 |

| Packed red cells used (n) | 265 | 524 | 178 | 967 | |

| Thrombocyte concentrates used (n) | 32 | 262 | 10 | 304 | |

| Fresh frozen plasma used (n) | 82 | 148 | 18 | 248 | |

| Inpatients receiving RBC transfusions (n) | 68 | 148 | 60 | 276 | |

| Mean Hb concentration (g/dL) and standard deviation | 77,39 ± 2,03 (SD) | 67,21 ± 2,84 (SD) | 77,47 ± 5,86 (SD) | ||

| Second period | Hospitalizations (n) | 70 | 251 | 541 | 862 |

| Packed red cells used (n) | 85 | 286 | 104 | 475 | |

| Thrombocyte concentrates used (n) | 10 | 154 | 5 | 169 | |

| Fresh frozen plasma used (n) | 25 | 122 | 16 | 163 | |

| Inpatients receiving RBC transfusions (n) | 27 | 93 | 43 | 163 | |

| Mean Hb concentration (g/dL) and standard deviation | 77,19 ± 3,65 (SD) | 64,35± 4,20 (SD) | 81,26±6,89 (SD) | ||

61.48% of hospitalizations took place in the first time interval. Considering the weekly hospitalizations, we observed a statistically significant (p < 0.0001) reduction of inpatient numbers after the special regulations were implemented (125.09 min:42; max:139 vs 24.16 min:16; max:71) apart from the Division of Hematology.

Combined, the weekly average RBC utilization was significantly (p < 0.0001) diminished in the second time interval (87.90 min:42; max:139 vs 43.28 min:16; max:71), as well as considering the included departments separately (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Weekly usage of packed red cell concentrates. Summative weekly representation of the red blood cell concentrates' usage suggests that the Division of Hematology has been the clinic with the highest use of this blood product type followed by the Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care and Department of Surgery. The red blood cell concentrate usage has been significantly lower in the second time interval, especially in the first weeks of this period. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

For detailed results of the statistical analyses, we refer to Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of detailed statistical analysis

| Tested variable | Clinical unit | First period |

Second period |

Significance (p-value and Mann Whitney's U) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Deviation or min;max | Mean | Std. Deviation or min; max | |||

| Mean weekly hospitalizations (patients/week) | Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care | 16.63 | 4;26 | 6.36 | 2;9 |

0.0020 U=14.00 |

| Division of Hematology | 28.81 | 6.25 | 22.81 | 5.98 | 0.0560 U = 31.00 |

|

| Department of Surgery | 79.63 | 38;99 | 49.18 | 31;72 |

0.0010 U=11.5 |

|

| Clinical units combined | 125.09 | 42;139 | 78.36 | 16;71 |

0.0001 U=10.00 |

|

| Weekly used red blood cell concentrates (RBC/week) | Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care | 24.09 | 13.05 | 7.72 | 6.48 | 0.0020 |

| Division of Hematology | 47.63 | 17.38 | 26.00 | 12.88 | 0.0040 | |

| Department of Surgery | 16.18 | 9,62 | 9.45 | 4.41 | 0.0480 | |

| Clinical units combined | 87.90 | 42;139 | 43.18 | 16;71 | 0.0001 | |

| Weekly average red blood cell products per transfused patient (RBC/patient) | Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care | 3.89 | 1.05 | 2.63 | 1.43 | 0.0300 |

| Division of Hematology | 3.57 | 1.15 | 3.03 | 0.83 | 0.2210 | |

| Department of Surgery | 2.70 | 1.24 | 2.53 | 0.71 | 0.2230 | |

| Clinical units combined | 3.46 | 0.71 | 2.83 | 0.60 | 0.0370 | |

| Weekly average proportion of transfused patients (%) | Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care | 40.05 | 17.91 | 36.40 | 21.68 | 0.6710 |

| Division of Hematology | 48.71 | 15.52 | 38.56 | 16.84 | 0.1570 | |

| Department of Surgery | 6.58 | 3.47 | 8.67 | 5.72 | 0.3120 | |

| Clinical units combined | 20.02 | 3.64 | 19.31 | 5.34 | 0.7180 | |

| Pretransfusion Hb concentration (g/L) | Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care | 77.39 | 2.03 | 77.19 | 3.65 | 0.380 |

| Division of Hematology | 67.21 | 2.84 | 64.35 | 4.20 | 0.083 | |

| Department of Surgery | 77.47 | 5.86 | 81.26 | 6.89 | 0.420 | |

| Clinical units combined | 74.02 | 2.39 | 69.59 | 10.30 | 0.0110 | |

| Weekly used thrombocyte concentrates (platelet concentrates/week) | Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care | 2.90 | 0;9 | 0.90 | 0;4 |

0.0280 U=27.50 |

| Division of Hematology | 23.81 | 6.940 | 14.00 | 5.93 | 0.0020 | |

| Department of Surgery | 0.90 | 0;3 | 0.45 | 0;2 | 0.4010 U = 47.50 |

|

| Clinical units combined | 27.63 | 6.23 | 15.36 | 6.74 | 0.0001 | |

| Weekly used fresh frozen plasma (FFP units/week) | Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care | 7.45 | 0;16 | 2.27 | 0;10 |

0.0080 U=21.00 |

| Division of Hematology | 13.45 | 0;80 | 11.09 | 0;46 | 0.8470 U = 57.00 |

|

| Department of Surgery | 1.63 | 0;8 | 1.45 | 0;6 | 1.0000 U = 60.00 |

|

| Clinical units combined | 22.54 | 0;94 | 14.81 | 0;48 | 0.5190 U = 50.00 |

|

The significance threshold has been set at p<0.05. The significant differences of the tested variables are represented bold.

A statistically significant (p = 0.0110) difference has been observed (74.02 g/L ± 2,39 standard deviation - SD vs 69.59 g/L ± 10,30 SD) considering variance of pre-transfusion Hb levels in the included clinics overall. The clinical departments individually have shown slight differences between the two tested periods. In case of Anesthesiology and Intensive Therapy the mean Hb pre-transfusion concentration has almost been identical, with a wider range of distribution. Patients hospitalized at Division of Hematology presented a lower mean of pre-transfusion Hb concentration in the second time interval, but the difference was not statistically significant. At the Department of Surgery, we observed slightly increased pre-transfusion mean Hb concentrations in the second period. However, these differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Boxplots of measured hemoglobin concentrations before red blood cell transfusions by clinics and combined (X-mean marker). Our data suggests that there were slight differences regarding pretransfusion hemoglobin concentrations comparing the two time intervals. Overall, mean pretransfusion hemoglobin concentrations have been significantly decreased, showing a wider range of distribution. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Overall weekly average platelet concentrates’ usage has been significantly reduced after implementing the modified regulations (p = 0.0001), except the Department of Surgery (p = 0.4010). Pre-transfusion platelet count has been evaluated in the case of Division of Hematology, where mean platelet count has been similarly low (p = 0.6090) in the two analyzed time intervals (9,77 G/L (min:0,00 G/L, max:49,00 G/L) vs 10,28 G/L (min 1,00 G/L, max 33,00 G/L)). (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Weekly usage of thrombocyte concentrates. The represented data suggests a marked decrease of platelet concentrate usage in the first weeks of the second interval, after which thrombocyte concentrate usage is gradually increasing by the end of the analyzed period. The highest demand has been registered at the Division of Hematology. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Regarding FFP usage, its consumption was significantly reduced at the Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care (p = 0.0080). However, overall weekly average FFP usage at the JPCB did not differ significantly in the analyzed time intervals (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Weekly usage of fresh frozen plasma during the tested period. The Division of Hematology also includes apheresis as a therapeutic option, therefore the FFP usage is significantly related to the activity of the apheresis team. We can observe that on weeks 8, 9, 16, 17 and 22 a very high number of FFP has been administrated at the Division of Hematology, which occurred on those weeks, when therapeutic apheresis has been performed on different patients that needed the intervention. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

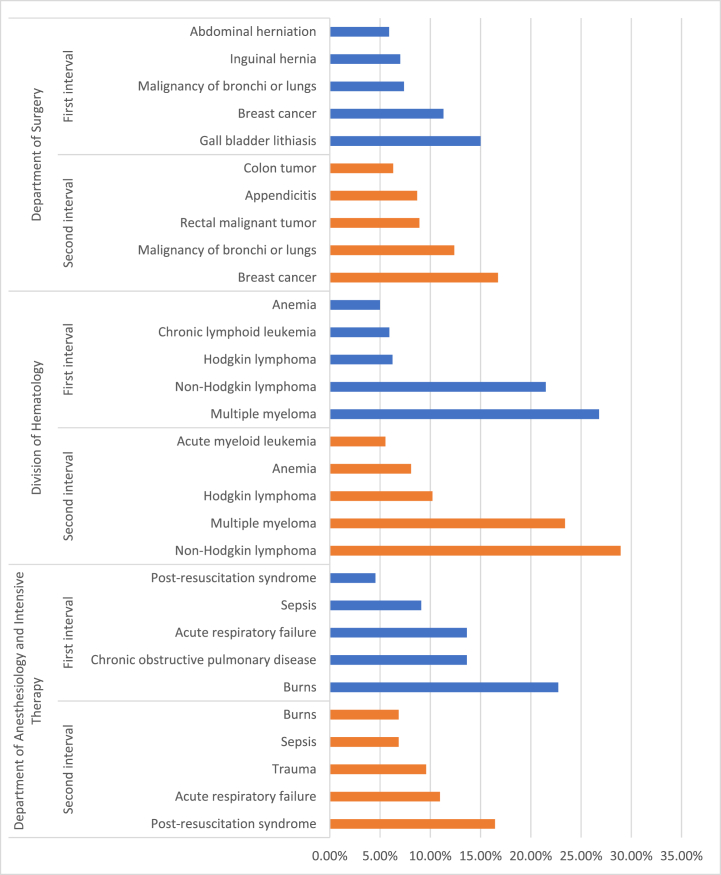

We analyzed the five most frequent diagnoses in the two intervals of the tested period (Fig. 5). At the Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Therapy, the top five most frequent diagnoses have been unchanged, although slight differences occurred in their recurrence. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin-lymphoma and multiple myeloma have been the diagnoses with the highest frequency in both time intervals at the Division of Hematology, followed by anemia. Our data suggest that the Department of Surgery has been the most affected among the evaluated clinical units. In the first interval, the diagnoses of highest occurrence were represented by gall bladder diseases, inguinal and abdominal herniations followed by malignancies of breast and lungs or bronchi. After the special regulations had been introduced, elective surgical interventions were abruptly reduced. The most frequent diagnoses were breast and pulmonary malignancies in this interval, followed by rectal and colon tumors. Appendicitis has also become one of the most frequent causes of hospitalizations during the second period (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Occurrence of the most frequent diagnoses at the evaluated clinics during the tested time intervals. The columns represent the rate of the diagnoses in ascending order by clinics and time intervals. Further data regarding the frequency of diagnoses by clinics is represented in the supplementary material provided. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

5. Discussion

COVID-19 caused by the novel coronavirus escalated rapidly into the pandemic the world has been facing since. The special measures aiming to stop or reduce the aggravation of the pandemic influenced the blood supply and patient care as well [14,15].

Our retrospective study aimed to assess the tendencies in blood product usage at JPCB, Clinical Centre, University of Pécs, after the coronavirus pandemic significantly affected the Hungarian healthcare. Supply of blood products and blood demand was rarely constant, even in the pre-pandemic period [16]. Regular fluctuations are observed around holidays and in summer. The clinics and healthcare units try to adapt by reducing elective surgical interventions or postponing deferrable cases to a later appointment. However, these fluctuations are much more complex, during the Christmas period, blood supply is substantially increased while at the beginning of the year and in the summer the blood product demand is more increased [17,18].

In Hungary, blood donations are exclusively voluntary. Generally, a larger proportion of blood donations occur during blood drive events outside the blood collection services, while the remaining blood collections take place in the blood banks. Outside blood collection events have been temporarily banned due to the coronavirus pandemic and the blood collections' schedule inside the blood banks were prolonged during this period aiming to compensate the canceled outside events. Blood donors were asked for a previous self-assessment regarding the symptoms of any type of infectious disease prior to blood donation, as well as an online blood donor appointment system was implemented to avoid increased number of donors in the waiting area of the blood collection institutions. In the first months of the pandemic nationwide blood donor appearances have been reduced by 28%, while nationwide RBC and FFP utilization reduced by around 30% and platelet concentrates’ use fell by 20% [8].

The temporary deferral of elective surgical interventions caused a significant reduction of hospitalizations in the evaluated units of JPCB. Our data concerning the diagnoses of inpatients supports, that after introducing restrictive rules in Hungary, elective surgical cases and patients with an underlying condition were postponed – if possible – to a later appointment, similar to other healthcare centers [19].

Significant changes were implemented at the Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Therapy to match the potentially increased patient care demand due to severe COVID-19 cases [20]. Weekly average hospitalizations have been significantly reduced in the second time interval of the tested period, although the first five most frequent diagnoses remained unchanged compared to the pre-pandemic interval. During the investigated time interval, critically ill COVID-19 patients were treated at another site of Clinical Center of University of Pécs, due to the reduced number of the cases. Hematology patients are rarely deferrable due to the urgent diagnosis and therapy of their underlying condition and the necessity of continuous monitoring and medical care for their correct treatment. Hence, the most frequent diagnoses after the introduction of restrictive regulations have been unchanged compared to the first period of the analyzed time interval, which confirms the exceptional, demanding situation of the hematology patient [21]. Inpatient numbers presented a decreasing tendency in the case of the Division of Hematology compared to the pre-pandemic baseline of weekly average inpatients. Nonetheless, hospitalizations remained more frequent than in the case of other analyzed units.

Overall, weekly used RBCs' volumes presented a significant reduction in the second time interval compared to the pre-pandemic baseline consumption. Our findings suggest that although less packed red cell units were administrated, the proportion of inpatients needing transfusion did not change significantly. However, the observed reduction of RBCs transfused calculated per patient together with the slight decrease of pretransfusion Hb concentrations had a favoring effect on the reduction of blood product usage. The Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Therapy has been the only clinical unit where a significant decline of transfused red blood cell product units per patient occurred. A possible explanation for this finding could be the higher blood demand characteristic for the first time interval due to a higher proportion of hospitalized patients with burns. This condition requires more blood products than other underlying diseases [22].

Overall, pre-transfusion Hb concentrations have been reduced significantly in comparison of the selected time intervals. In the Division of Hematology, a slight reduction of pre-transfusion Hb concentrations could be observed. In both time intervals, patients at the Division of Hematology presented the lowest pre-transfusion Hb concentrations. The increased anemia tolerance of these patients is a possible explanation of our findings, due to the higher incidence of chronic anemia in these patients [23]. Thus, restrictive blood transfusion policy could be applied better. At the Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Therapy mean pre-transfusion Hb concentration was almost equal. The hospitalized patients presented similar diagnoses, and the increased transfusion risk was possibly present in both time intervals, these patients being in critically ill conditions. In the case of the Department of Surgery mean pre-transfusion Hb concentrations slightly increased and presented a wider range of distribution, which is also sustaining the fact that elective surgical cases and patients with deferrable underlying conditions were postponed to a later appointment while patient care was temporarily focused on treating patients presenting with emergency, life-threatening diseases. Thus, pharmacological correction of preoperative anemia and anemia tolerance enhancement in severe cases were challenging.

Utilized platelet concentrate volumes had shown a significant reduction characteristic for the second time interval, which can be explained by the overall reduction of hospitalizations and inpatient numbers characteristic for the period after special regulations were introduced. As the highest platelet concentrate user has been the Division of Hematology, the analysis of their data showed that pre-transfusion platelet count was similar in the two time intervals. Based on our observations, it is assumed that patients needing platelet transfusion received adequate care in both time intervals.

FFP products’ overall usage was similar after the introduction of stricter regulations. This blood product type was gradually less utilized as efficient alternatives like albumin, coagulation factor concentrates, cryoprecipitates, fibrin glue etc., are widely introduced in everyday medical practice. Thus, the impact of regulations exerted a less noticeable effect on FFP usage than other labile blood products [24].

Transfusion volumes have been relatively reduced compared to the pre-pandemic baseline, beginning in the first weeks of the second time interval. A slow, gradual return toward previous blood product usage could also be observed by the end of the analyzed timeframe. Based on our findings, life-threatening blood product shortage issues were not characteristic for the analyzed period.

Pre-transfusion Hb concentrations, transfused RBCs per patient, and the proportion of transfused patients did not decrease significantly in every included department. However, the combination of these modifications resulted in the significant decrease in RBC transfusions.

The limitations of this study are that the collection of a more detailed data regarding the clinical status of patients treated in the analyzed period, as well as real-time data acquiring was not possible. However, our results reveal important aspects of modifications of blood product usage and patient care in the included clinics of JPCB during the first months of the coronavirus pandemic.

6. Conclusion

Our observed results indicate that the pandemic had an important effect on blood product usage by introducing different patient care policies and the temporary delay of elective surgical interventions. Drastic reduction of pre-transfusion Hb concentration was not required due to the implemented modern transfusion policies. Despite the challenging circumstances of blood collection and blood product supply, the hospitalized patients received adequate care. The appropriate number of blood products could be provided for the treatment of inpatients in the JPCB.

Author contribution statement

Sándor Pál:conceived and designed the experiments; analyzed and interpreted the data; wrote the paper.

Barbara Réger: analyzed and interpreted the data; wrote the paper.

Hussain Alizadeh: contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data, wrote the paper.

Árpád Szomor: contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

András Vereczkei: contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data, wrote the paper.

Tamás Kiss: contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Attila Miseta: contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Margit Solymár: analyzed and interpreted the data; wrote the paper.

Zsuzsanna Faust: conceived and designed the experiments; analyzed and interpreted the data; wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Stanworth S.J., New H.V., Apelseth T.O., Brunskill S., Cardigan R., Doree C., et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on supply and use of blood for transfusion. Lancet Haemat. 2020;7(10):e756–e764. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30186-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raturi M., Kusum A. The active role of a blood center in outpacing the transfusion transmission of COVID-19. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 2020;27(2):96–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiely P., Hoad V.C., Seed C.R., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2: implications for blood safety and sufficiency. Vox Sang. 2020 doi: 10.1111/vox.13009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esakandari H., Nabi-Afjadi M., Fakkari-Afjadi J., et al. A comprehensive review of COVID-19 characteristics. Biol. Proced. Online. 2020;22:19. doi: 10.1186/s12575-020-00128-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.40/2020. (III. 11) 2020. Governmental Ordinance, Hungarian Official Gazette [Korm. rendelet. Magy Közlöny] (39) [Google Scholar]

- 7.41/2020. (III. 11) 2020. Governmental Ordinance, Hungarian Official Gazette [Korm. rendelet. Magy Közlöny] (40) [Google Scholar]

- 8.A Tordai, S Nagy, K Baróti-Tóth et al. Effect of the SARS-CoV2 pandemic on Hungarian blood banking [A SARS-CoV2-járvány hatása a hazai vérellátásra], Hematológia-Transzfuziológia 53(2):96-105.

- 9.Yahia A.I.O. Management of blood supply and demand during the COVID-19 pandemic in King Abdullah hospital, Bisha, Saudi Arabia. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2020;59(5) doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2020.102836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . ECDC; Stockholm: 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Supply of Substances of Human Origin in the EU/EEA – Second Update. 10 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Retteghy T.A. Perioperative Patient Blood Management [A vértakarékos betegellátás a perioperatív szakban] Hematológia−Transzfuziológia. 2018;51(4):194–203. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaglio S., Prisco D., Biancofiore G., Rafanelli D., Antonioli P., Lisanti M., et al. Recommendations for the implementation of a Patient Blood Management programme. Application to elective major orthopaedic surgery in adults. Blood Transfus. 2016;14(1):23–65. doi: 10.2450/2015.0172-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shander A., Van Aken H., Colomina M.J., Gombotz H., Hofmann A., Krauspe R., et al. Patient blood management in Europe. Br. J. Anaesth. 2012;109(1):55–68. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogar C.O., Okoroiwu H.U., Obeagu E.I., Etura J.E., Abunimye D.A. Assessment of blood supply and usage pre- and during COVID-19 pandemic: a lesson from non-voluntary donation. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 2021;28:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2020.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley W., Love K., McCullough J. Public policy impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on blood supply in the United States. Am. J. Publ. Health. 2021;111(5):860–866. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy C., Fontaine M., Luethy P., et al. Blood usage at a large academic center in Maryland in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Transfusion. 2021;61(7):2075–2081. doi: 10.1111/trf.16415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mccarthy L.J. How do I manage a blood shortage in a transfusion service? Transfusion. 2007;47(5):760–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanger S.H., Yates N., Wilding R., et al. Blood inventory management: hospital best practice. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2012;26(2):153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Søreide K., Hallet J., Matthews J.B., et al. Immediate and long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delivery of surgical services. Br. J. Surg. 2020;107(10):1250–1261. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Dorzi H.M., Aldawood A.S., Almatrood A., et al. Managing critical care during COVID-19 pandemic: the experience of an ICU of a tertiary care hospital. J. Infect. 2020;14(11):1635–1641. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ueda M., Martins R., Hendrie P.C., McDonnell T., Crews J.R., Wong T.L., et al. Managing cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Agility and collaboration toward a common goal. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020;18(4):366–369. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu R.P., Lin F.C., Ortiz-Pujols S.M., Adams S.D., Whinna H.C., Cairns B.A., et al. Blood utilization in patients with burn injury and association with clinical outcomes (CME) Transfusion. 2013;53(10):2212–2221. doi: 10.1111/trf.12057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hare G.M.T. Tolerance of Anemia: understanding the adaptive physiological mechanisms which promote survival. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2014;50(1):10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Görlinger K., Fries D., Dirkmann D. Reduction of fresh frozen plasma requirements by perioperative point-of-care coagulation management with early calculated goal-directed therapy. Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy. 2012;39(2):104–113. doi: 10.1159/000337186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.