Abstract

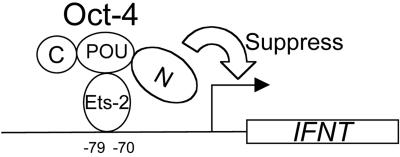

Oct-4 is a POU family transcription factor associated with potentially totipotent cells. Genes expressed in the trophectoderm but not in embryos prior to blastocyst formation may be targets for silencing by Oct-4. Here, we have tested this hypothesis with the tau interferon genes (IFNT genes), which are expressed exclusively in the trophectoderm of bovine embryos. IFNT promoters contain an Ets-2 enhancer, located at −79 to −70, and are up-regulated about 20-fold by the overexpression of Ets-2 in human JAr choriocarcinoma cells, which are permissive for IFNT expression. This enhancement was reversed in a dose-dependent manner by coexpression of Oct-4 but not either Oct-1 or Oct-2. When cells were transfected with truncated bovine IFNT promoters designed to eliminate potential octamer sites sequentially, luciferase reporter expression from each construct was still silenced by Oct-4. Full repression required both the N-terminal and POU domains of Oct-4, but neither domain used alone was an effective silencer. Oct-4 and Ets-2 formed a complex in vitro in the absence of DNA through binding of the POU domain of Oct-4 to a site located between the “pointed” and DNA binding domains of Ets-2. The two transcription factors were also coimmunoprecipitated after being expressed together in JAr cells. Oct-4, therefore, silences IFNT promoters by quenching Ets-2 transactivation. The POU domain most probably binds to Ets-2 directly, while the N-terminal domain inhibits transcription. These findings provide further evidence that the developmental switch to the trophectoderm is accompanied by the loss of Oct-4 silencing of key genes.

Tau interferons (IFN-τ) are structurally related to IFN-β, IFN-α, and IFN-ω (with approximately 25, 50, and 75% primary sequence identities, respectively) (38, 39). Although these IFNs exhibit typical properties, including the ability to induce an antiviral state in cells expressing the appropriate IFN receptor, their function is in reproduction and not in disease prevention (2, 11, 37, 38). The preattachment conceptuses of ruminant species, such as cattle, sheep, and deer, produce IFN-τ in order to prevent the regression of the maternal corpus luteum, an event that would normally occur at the end of the estrous cycle if the animal were not pregnant (2, 11, 37). Members of the multigene IFN-τ family are expressed weakly in the trophectoderm of cattle beginning when this epithelium differentiates at blastocyst formation (11, 14, 16, 37). The level of production of IFN-τ per cell increases markedly as the blastocyst enlarges and begins to elongate. Production is down-regulated when the trophectoderm forms contacts with the uterine wall and as the process of placentation is initiated. The expression of IFN-τ is confined to a single cell layer, the trophectoderm, for 1 to 2 weeks during the critical period when the corpus luteum of pregnancy must be rescued and progesterone production must be maintained. Neither the inner cell mass nor the embryo that is derived from it expresses this IFN (2, 11, 37).

An analysis of the nucleotide sequences of the IFN-τ genes (IFNT genes) has indicated that the progenitor gene arose by duplication of a closely related gene, one encoding IFN-ω, approximately 35 million years ago (38, 39). This event appeared to involve a disruption in the upstream promoter region of the new gene relative to its parent and presumably led to the observed loss of viral inducibility (20) and a gain in the ability to be expressed constitutively in trophoblasts. A major divergence in sequence identity between the promoter sequences of IFNT genes and IFN-ω genes (IFNW genes) begins just proximal to a presumptive Ets binding site (−79 to −70) in the IFNT genes which is lacking in the IFNW genes (38, 39). This region of the IFNT promoter has been implicated in controlling high-level IFN-τ expression in the trophectoderm (10, 20).

In experiments that used the yeast one-hybrid screen, Ets-2 was confirmed as the transcription factor that most likely bound to the Ets binding site in the IFNT proximal promoter region (13). Ets-2 strongly transactivates IFNT-luciferase (luc) gene reporters, and IFNT genes that lack the Ets site are poorly expressed. The Ets-2 protein is also expressed in the trophectoderm of ovine conceptuses when this tissue expresses IFNT genes. A role for Ets-2 in controlling the differentiation of trophoblast derivatives has been proposed because deletion of the murine ets-2 gene leads to embryonic death by day 8.5 as the result of defective placental development (56). Further, a number of genes in addition to IFNT genes, which are expressed in trophoblasts but not in the inner cell mass (i.c.m.), are regulated by the Ets factor (18, 30, 36, 50, 52).

It was recently demonstrated that two human genes expressed in trophoblasts, the α and β subunits of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), are silenced in human choriocarcinoma cells by the transcription factor Oct-4 (22, 23). Oct-4 (48), also called Oct-3 (29), belongs to the family of POU transcription factors that contain a bipartite DNA binding domain (POU specific and POU homeodomain) (43). In mouse embryos, it is expressed predominantly in blastomeres, pluripotent early embryo cells, and the germ cell lineage (34, 42, 47). Its mRNA and protein are expressed throughout the cleavage stages of embryo development but not in the trophectoderm of blastocysts (32). The situation is slightly different in bovine embryos (19, 54). There, Oct-4 is expressed strongly in the i.c.m. However, the expression of Oct-4 can also be detected in the trophectoderm until day 10, approximately 3 days after blastocyst formation but before the massive up-regulation of IFN-τ that accompanies trophoblast elongation (14, 37). Oct-4 has been predicted to play a defining role in maintaining cells in the pluripotent state and in preventing differentiation of the i.c.m. of mouse embryos into the trophectoderm (28). Day 4.5 mouse embryos with their Oct-4 gene deleted lack a true i.c.m. and consist entirely of trophectoderm-like cells (26). It is not yet clear how Oct-4 prevents differentiation, but it likely activates certain key genes (3, 31, 41, 58) while repressing others (22, 23). Down-regulated Oct-4 expression presumably lifts the constraints operating on the differentiation process.

These data together suggest that Ets-2 and Oct-4 might have counteracting roles in the functional differentiation of trophoblasts. While the former may have a promoting action, the role of Oct-4 may be in restraint. Here we have examined whether the two transcription factors interact in controlling IFNT gene expression, which is a biochemical marker for the functional differentiation of trophoblasts in bovine embryos.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reporter gene constructs and expression plasmids.

A boIFNT1 promoter fragment (bp −457 to +66) (10) was subcloned into the KpnI site of the luciferase reporter plasmid, pGL2-Basic (Promega, Madison, Wis.) (−457luc). Site-directed mutagenesis of the Ets-2 binding site at −79 on the −457luc promoter was achieved with primers mets1 and mets2 (Table 1) and standard PCR procedures (8). The mutated promoter was subcloned into the SacI site of pGL2 Basic Vector. A series of deletion mutants of boIFNT1 promoter fragments was generated from the −457luc construct by PCR with promoter primers, −353se, −228se, and −91se, and vector primer, GL2 (Table 1). The PCR fragments were subcloned from the pBluescript SK(−) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) vector by SacI and XbaI digestion and inserted into the luciferase reporter plasmid. The −126luc construct (containing the promoter fragment from bp −126 to bp +50) has been described previously (13). −126luc was mutated by introduction of an StuI site at −50. The −49luc construct was generated from mutated −126luc by NotI and StuI digestion, blunt ending, and self-ligation. A construct consisting of three tandemly repeated octamer motifs (3×Oct) was generated by ligation of annealed oligonucleotides, OCTf and OCTr (21) (Table 1), and was cloned into the SpeI site of pBluescript SK(−). By using the BamHI and XbaI sites of the vector polylinker, the 3×Oct fragment was cloned into the same sites of pTKCAT (51), upstream of the thymidine kinase (tk) promoter (−105 to +51). The 3×Oct-tk fragment was released by XbaI and XhoI digestion and was cloned into the luc reporter plasmid. The fidelity of all the constructs was verified by DNA sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Synthetic oligonucleotides used in PCR and electrophoretic mobility shift assaysa

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| −353se: | 5′ -ATC AAT GGA AAA TTA TAT TCC TGA CAT AAG ATA AAC |

| −228se: | 5′ -CCT TTA TTT AGT TTC TCA |

| −91se: | 5′ -CTG AAA ACA CAA ACA GGA AGT G |

| GL2: | 5′ -CTT TAT GTT TTT GGC GTC TTC CA |

| Oct4se: | 5′ -GGA ATT CAT GGA TCC TCG AAC CTG G |

| Oct4as: | 5′ -GGA AGA TCT CCT CAG TTT GAA TGC ATG G |

| −126se: | 5′ -AGC GAA TTC GAC TAC ATT TCC TAG GTC |

| −34as: | 5′ -GGG AAG ACG GTA CTC ATT ATC |

| OCTf: | 5′ -CTA GGG TAA TTT GCA TTT CTA A |

| OCTr: | 3′ -CC ATT AAA CGT AAA GAT TGA TC |

| −353/−333: | 5′-ATC AAT GGA AAA TTA T/G TTA CCT TTT AAT ATA |

| −267/−238: | 5′ -TAA GTC TTT GCA TAC TTA C/TT CAG AAA CGT ATG AAT GT |

| −201/−182: | 5′ -TAT ACA TTT ACA TTG ACA A/TA TGT AAA TGT AAC TGT TT |

| −170/−146: | 5′ -TGG GAA AAT TAA ATT TCT ACT GT/CC CTT TTA ATT TAA AGA TGA CAT |

| mets1: | 5′ -CGC ACT AGT CGT GAG AGAGAA |

| mets2: | 5′ -CGC ACT AGT TTG TGT GTT CAG |

Incorporated restriction enzyme cutting sites (6 bases) and the core sequence of the Oct-4 binding sites (8 bases) are underlined.

The Oct-1 and Oct-2 expression plasmids that were cloned into the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter-driven vector, pCG, were a gift from W. Herr (53). The expression plasmids for mouse Oct-4 and its derivatives, pCMV-Oct4, pCMV-POU4, pCMV-4N-POU4, and pCMV-POU4-4C, were gifts from H. Schöler. Plasmid pCMV-4N was created from pCMV-Oct4 by removal of the PstI (at amino acid [aa] 135)-NsiI (at aa 349) fragment and self-ligation. For glutathione S-transferase (GST)–Oct-4 fusion proteins, cDNAs encoding Oct-4 domains, full-length Oct-4 (aa 1 to 352), 4N-POU4 (aa 1 to 286 plus 349 to 352), POU4-4C (aa 135 to 352), POU4 (aa 135 to 286 plus 349 to 352), Oct4N (aa 1 to 135 plus 350 to 352), and Oct4C (aa 280 to 352), were amplified by PCR from these pCMV plasmids and then subcloned into a GST protein expression vector, pGEX-4T-1 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.). The Ets-2 expression plasmid (pCGNEts-2) has been described previously (13). Either the β-galactosidase gene driven by the Rous sarcoma virus long terminal repeat (pRSVLTR-βgal) or the Renilla luc gene driven by the CMV promoter (pRL-CMV) (Promega) was used as an internal control in all transfection experiments.

Cell cultures and transfections.

JAr cells (HTB-144; American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (50 U/ml), and streptomycin (50 μg/ml) and transfected by the calcium phosphate method as described previously (13). The boIFNT1 promoter-luc reporter construct (3.2 μg) was cotransfected with either pCMV-Oct4 (0.2 to 0.4 μg) or pCGNEts-2 (0.2 to 0.4 μg). All transfections included 50 ng of pRSVLTR-βgal or 10 ng of pRL-CMV. Total amounts of transfected DNA were kept constant by adding corresponding empty vectors. luc reporter assays were conducted 36 h after transfection. Enzyme assays for analyses of transfection experiments were carried out as described previously (13), except when pRL-CMV was used. The activities of both firefly and Renilla luciferases were measured with a dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase or Renilla luciferase activity.

Western blot and immunoprecipitation analyses.

JAr cells were scraped from 6-cm dishes and lysed in 0.2 ml of the buffer-reagent M-PER (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.)/plate. After centrifugation, 75 μg of cleared cell lysate was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). The antisera were commercially prepared in rabbits. Anti-Oct-1, -2, and -4 (sc-231, sc-233, and sc-9081), diluted 1:1,000, and anti-Ets-2 (sc-351), diluted 1:4,000, were all products of Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif. The second antibody was alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G diluted 1:10,000, which was used in conjunction with a Western-Star chemiluminescence kit from Applied Biosystems, Bedford, Mass.

In the coimmunoprecipitation experiments, JAr cells at a density of 5 × 105/10-cm plate were transfected with 10 μg each of plasmids pCGNEts-2 and pCVM-Oct-4 (with empty vector as the transfected control). Cell lysis was done as described above. Cleared lysate was incubated with 0.1 mg of either the anti-Oct-4 antibody preparation described above or normal rabbit immunoglobulin G immobilized on a Protein G support (Seize X mammalian immunoprecipitation kit; Pierce). Subsequent washing of the affinity matrix was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Antigen was eluted in four successive 190-μl fractions by using the buffer provided in the kit. Samples (20 μl from the second fraction) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting as described above.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

A 1-kb Oct-4 cDNA fragment (48) amplified by PCR with primers Oct4se and Oct4as (Table 1) was subcloned into the EcoRI-BamHI site of vector pGBT9. The EcoRI-SalI cDNA fragment from construct pGBT9 was cloned into pGEX-4T-1 and used to transform Escherichia coli DH5α. The fidelity of the construct was verified by DNA sequencing, and bacterial extracts were processed as described elsewhere (13). Annealing of oligonucleotides OCTf and OCTr (Table 1) produces a double-stranded canonical octamer site (23). Reaction mixtures included 2 μg of E. coli protein containing either GST–Oct-4 or GST plus 10 fmol of 32P-labeled, double-stranded octamer DNA probe (∼18,700 cpm). For competition binding assays, competitor DNA (250-fold molar excess, 2.5 pmol) was added before incubation with the labeled probe. DNA binding conditions and the electrophoretic analysis have been described previously (13). Synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotides used as competitors are listed in Table 1 (−353/−333, −267/−238, −201/−182, and −170/−146). A DNA fragment from bp −126 to bp−34 of the boIFNT1 promoter was amplified by PCR by using primers −126se and −34as (Table 1). The amplified DNA was purified by agarose gel electophoresis and excised by using a QIAEX II kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). The quantity of DNA was measured by ethidium bromide fluorescence quantitation (45).

GST pull-down assay.

Each GST fusion protein was expressed in E. coli DH5α and allowed to bind to glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) under conditions recommended by the manufacturer. The size and quantity of bound fusion protein were estimated by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Human Ets-2 cDNA and murine Oct-4 cDNA were subcloned into pBluescript SK(−) to generate a template for the TNT-coupled transcription-translation system (Promega). A slurry of GST protein-beads (20 μl), which contained approximately 1 μg of protein, was suspended in 50 μl of binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.12 M NaCl, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.055% [vol/vol] 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5% [vol/vol] Nonidet P-40) (12). An aliquot (5 μl) of in vitro-translated [35S]-methionine-labeled protein was mixed with GST protein-beads and suspended for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were washed four times with 420 μl of washing buffer (0.12 M NaCl in the binding buffer was replaced with 0.1 M NaCl). The final, washed pellet was resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, boiled, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Radiolabeled proteins in the gel were visualized by fluorography by using EN3HANCE (New England Nuclear, Boston, Mass.).

RESULTS

Inhibition of boIFNT1 reporter expression by Oct-4.

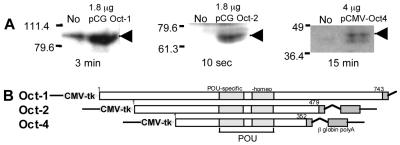

As in earlier studies (13), transfections were performed with JAr choriocarcinoma cells, which are of human origin, because appropriate bovine or ovine cell lines are not available. A preliminary study was designed to determine first whether Oct-1, Oct-2, and Oct-4 were expressed in JAr cell and second whether the pCMV expression plasmid gave equivalent levels of expression of Oct-1, Oct-2, and Oct-4. Western blot analysis of untransfected JAr cells (Fig. 1A) showed that, while small amounts of Oct-1 were present, neither Oct-2 nor Oct-4 could be detected in the cell extracts. Importantly, different levels of apparent expression of the three Oct proteins were observed 36 h after transfection. Detection of Oct-4 was achievable only when the largest amount of expression plasmid (4 μg) was transfected and then required long exposure times to X-ray film. Although these data may be explained in part by the relative avidities of the antisera used in the chemiluminescence procedure, they also suggest that Oct-4 either is poorly expressed or has a short half-life in JAr cells. The Western blots revealed two bands of Oct-4 protein in transfected cells (Fig. 1A, right panel), consistent with data obtained by others, who indicated that the higher-molecular-weight form was phosphorylated (4).

FIG. 1.

Expression of Oct proteins in transfected JAr cells. (A) Western blotting of JAr cell extracts (75 μg) before and after transfection with expression plasmids for Oct-1, Oct-2, and Oct-4. The amount of plasmid used in the transfection is shown above each panel; the exposure times for detecting chemiluminescence are shown below. Arrowheads show the positions of the respective proteins. The numbers to the left of each gel blot are molecular size markers (in thousands). (B) Structures of the Oct expression constructs that were used in transfection experiments. All plasmids share the same expression system [CMV promoter-tk leader and β-globin gene poly(A) signal]. The numbers represent the lengths (in amino acid residues) of the Oct proteins.

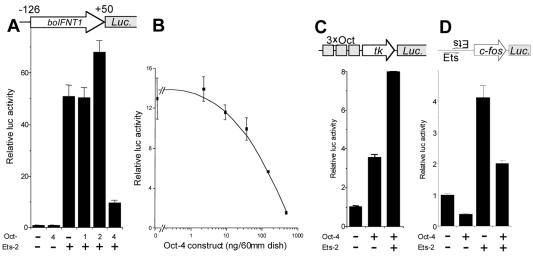

It was previously shown that a −126 boIFNT1 promoter can be strongly transactivated by Ets-2 in JAr cells (13). As shown in Fig. 2A, 0.2 μg of the Ets-2 expression plasmid provided greater than 50-fold transactivation of a luc reporter plasmid placed downstream of the −126 boIFNT1 promoter in this particular series of experiments. Cotransfection with an Oct-4 expression plasmid (0.2 μg/dish) in the absence of Ets-2 caused a modest inhibition (about 10%) of luciferase expression from the −126 boIFNT1 promoter. However, Oct-4 was able to reverse the transactivation effects of Ets-2 by approximately 80%. In contrast, cotransfection with either an identical amount of Oct-1 plasmid (Fig. 2A) or amounts up to 1.8 μg (data not shown) had no effect. Oct-2 cotransfection (0.2 μg) provided approximately 40% stimulation above that caused by Ets-2 alone (Fig. 2A), which increased twofold with 1.8 μg of plasmid (data not shown). Therefore, despite its apparent low level of expression compared to that of Oct-1 and Oct-2, Oct-4 was still able to exhibit a major suppressive effect on the Ets-2-transactivated boIFNT promoter.

FIG. 2.

Oct-4 acts solely as a repressor of the boIFNT1 promoter. (A) The −126luc construct is suppressed specifically by Oct-4 and not by other octamer proteins. JAr cells were transfected with 3 μg of −126luc, 0.2 μg of Ets-2, and/or 0.2 μg of Oct expression plasmid. Reporter activities were normalized to the activity of cotransfected plasmid pRL-CMV. (B) Dose-dependent repression of the boIFNT1 promoter by Oct-4. JAr cells were transfected with 3.2 μg of −126luc, 0.4 μg of Ets-2, and 0 to 400 ng of Oct-4 expression plasmid. Reporter activities were normalized to the activity of cotransfected plasmid pRSVLTR-βgal. Error bars show standard errors (SE). (C) Oct-4 transactivation of an artificial promoter, 3×Oct-tk. JAr cells were transfected with 3 μg of 3×Oct-tk reporter, 0.2 μg of Oct-4, and 0.2 μg of Ets-2 expression plasmid. Reporter activities were normalized to the activity of cotransfected plasmid pRL-CMV. Results are means and SE from three independent experiments. Activity is expressed as fold activation relative to basal activity. (D) Oct-4 represses E.18 reporter activity in either the absence (−) or the presence (+) of Ets-2. JAr cells were transfected with 3.2 μg of E.18-luc reporter and 0.4 μg of Ets-2 expression plasmid. Reporter activities were normalized to the activity of cotransfected plasmid pRSVLTR-βgal. Data are reported as described for panel C.

There was a concern that Oct-4 might suppress Ets-2 expression through an ability to interact with the CMV promoter. To resolve this question, all reporter activities, including those in Fig. 2A, were normalized by reference to the activity of a cotransfected Renilla luciferase reporter (pRL-CMV) that was driven by the same CMV promoter as that used to express Ets-2. The luciferase activity from this plasmid was not inhibited by Oct-4 (data not shown).

Transcription factors are known to exhibit marked dose-dependent differences in activity. For example, a transactivator can become inhibitory when transfected at high concentrations (reference 25 and references therein). Therefore, we examined the ability of a range of Oct-4 plasmid concentrations to suppress reporter activity when cotransfected with a fixed amount of −126luc and Ets-2 plasmid (Fig. 2B). Oct-4 suppression was dose dependent. At no point in the titration was any significant activation of reporter activity noted. At the highest concentration used (0.4 μg of plasmid), Oct-4 suppressed more than 90% of the luciferase activity from the −126luc reporter.

Oct-4 is known to act as a transactivator as well as a suppressor (46). As shown in Fig. 2C, it was able to transactivate tandemly repeated octamer motifs (3×Oct) inserted upstream of a tk minimal promoter (−105 to +51) and a luc reporter approximately 3.5-fold in JAr cells. Cotransfection with Ets-2 unexpectedly enhanced expression to about eightfold, despite the fact that no obvious Ets binding site was present in the promoter. Control experiments (data not shown) showed that this effect was independent of Oct-4 expression and was likely due to the binding of Ets-2 to a cryptic site on the promoter.

Together, the data in Fig. 2A and B indicate that Oct-4 suppression of the IFNT promoter was not the result of general squelching but was due either to direct interaction of Oct-4 with the IFNT promoter or to an indirect mechanism involving a protein-protein interaction of some kind.

Oct-4 suppresses a simple promoter that contains Ets-2 binding sites.

To determine whether Oct-4 inhibits Ets-2 transactivation of a simple promoter, the E.18 reporter (57), which consists of two inverted Ets-2 consensus binding sites located upstream of a c-fos minimal promoter (−56 to +119), was cotransfected into JAr cells either alone or in combination with Oct-4 and Ets-2 expression plasmids (Fig. 2D). Ets-2 transactivation of the E.18 promoter was evident but was relatively modest compared with the effect on the more complex IFNT enhancer (Fig. 2A). Oct-4 suppressed the activity of the E.18 promoter, both in its basal state and after transactivation by Ets-2 (Fig. 2D), but the extent of silencing was limited (only about 50% in each instance). These experiments show that Oct-4 suppression of Ets-2 transactivation can occur through a simple Ets-2-responsive promoter that lacks obvious octamer binding sequences. Oct-4 therefore might be able to interact with Ets-2 without binding to DNA itself. Moreover, suppression seems somewhat independent of the promoter involved.

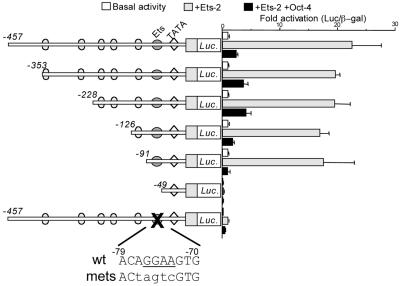

Oct-4 suppression of the boIFNT1 promoter after deletion of all presumptive octamer binding sites.

IFNT genes are intronless and occur as a multigene family (38, 39). The first 400 bases of their promoter regions are highly conserved both within and between species, as might be anticipated from their relatively recent origin. A −450 boIFNT1 promoter is also sufficient to direct the full expression of reporter genes in JAr cells (10). Consistent with earlier data (13), Ets-2 was able to transactivate a −457luc reporter 23-fold (Fig. 3). As anticipated, the activity increase observed in the presence of Ets-2 was suppressed more than 90% by cotransfection with 0.4 μg of Oct-4 plasmid. When the Ets-2 binding site on the −457luc promoter was inactivated by mutation, the ability of Ets-2 to transactivate the promoter was almost but not completely lost (Fig. 3). Oct-4 effects were also partially abolished when the mutated promoter was used, although only about one-half of the low residual activity noted in the presence of Ets-2 was inhibited by cotransfection with Oct-4.

FIG. 3.

Oct-4 suppresses the promoter activities of boIFNT1 promoter constructs with progressive deletions removing potential Oct binding sites. The IFNT promoter deletions (from −457 to −49 bp) linked to luc reporters were transfected into human JAr cells in either the absence (Basal) or the presence of the expression vectors for human Ets-2 (+Ets-2) and Ets-2 and murine Oct-4 together (+Ets-2 +Oct-4). As a control, expression from the −457luc construct, with its Ets binding site mutated, was measured in the presence and absence of Ets-2 with and without cotransfection with Oct-4. Reporter activities are expressed relative to the activity of cotransfected plasmid pRSVLTR-βgal. Results are means and standard errors from three independent experiments. Activity is shown as fold activation relative to the basal activity for each construct, except in two instances. For the mutated −457luc construct, fold changes in expression are shown relative to the basal expression of nonmutated −457luc. Similarly, expression from −49luc that lacks the Ets-2 binding site is compared to the basal expression of −126luc. A mutation targeted to the Ets binding site is indicated at the bottom of the figure. wt, wild type; mets, mutated Ets site.

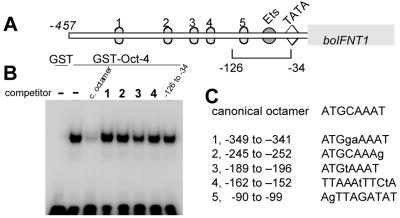

Oct-4 has been shown to bind at least two consensus motifs (ATGCAAAT and TTAAAATTCA) and a range of variants of these sequences (29). Five such octamer-like binding sites (designated 1 to 5 in Fig. 4C) are present within the −457 boIFNT1 promoter region. In order to define which of these sites might be responsible for Oct-4 silencing of the boIFNT1 promoter, a series of promoter deletion mutants progressively lacking one or more of these sites were constructed (Fig. 3). Plasmids containing the truncated genes were cotransfected with plasmids expressing either Ets-2 alone or both Ets-2 and Oct-4 together. Ets-2 up-regulated luciferase expression about 20-fold from each of the promoters that contained the Ets binding site, which is positioned between bp −79 and bp −70 (Fig. 3). In each instance, Oct-4 reversed the Ets-2 effect, reducing activity between 80 and 90%. Silencing even occurred with the −91 promoter, which lacked any recognizable octamer binding site. As expected, further deletion of the promoter to −49 almost completely eliminated Ets-2 up-regulation of the reporter.

FIG. 4.

Failure of Oct-4 to bind the octamer-like sites in the boIFNT1 promoter efficiently. (A) Structure of the IFNT promoter and the locations of the octamer-like sites, the Ets site, and the TATA box. (B) DNA competition binding assays with a GST–Oct-4 fusion protein. Recombinant GST (negative control) or GST–Oct-4 fusion protein was incubated with a 32P-labeled, double-stranded canonical octamer (Table 1) in the presence of either no competitor DNA (−) or a 250-fold excess of unlabeled probe (c. octamer), double-stranded oligonucleotides identical in sequence to the octamer-like sites in the boIFNT1 promoter (lanes 1 to 4), and the promoter fragment from −126 to −34 (last lane). (C) Comparisons of the putative octamer sites in the boIFNT1 promoter with canonical octamer sequences. Mismatched sequences are shown with lowercase letters.

DNA competition binding assay with Oct-4.

To identify whether Oct-4 suppresses IFNT promoter activity by binding to promoter DNA, a GST–Oct-4 fusion protein was used in a mobility shift assay for DNA competition analysis. A DNA fragment from the mouse immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene enhancer, which contains a canonical octamer site (49), was used as the DNA probe (Fig. 4C). Although the GST protein itself did not form a DNA-protein complex with the probe, the Oct-4 fusion protein did form a complex (Fig. 4B). A 250-fold molar excess of unlabeled probe competed efficiently with labeled probe, thereby confirming the specificity of the interaction (Fig. 4B).

As shown in Fig. 4A, the IFNT promoter contains five octamer-like sites, whose sequences are shown in Fig. 4C. Promoter octamer sequences 1, 2, and 3 resemble the probe sequence ATGCAAAT quite closely, while sequences 4 and 5 resemble a second type of Oct binding site, TTAAAATTCA (29). All five sites differ by only one or two base mismatches from the consensus sequence. Synthetic double-stranded DNAs were prepared to represent sites 1 to 4. A PCR-amplified DNA fragment (−126 to −34) from the boIFNT1 promoter contained site 5. All were used in a 250-fold molar excess in the probe competition assay. Octamer sequences 1, 2, 4, and 5 were completely ineffective as competitors for the canonical octamer oligonucleotide in the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (Fig. 4B). Octamer sequence 3 (ATGtAAAT), at bp −196, however, exhibited weak competitor activity at a 250-fold molar excess. Nevertheless, since deletion constructs −126 and −91 were as strongly suppressed by Oct-4 as the longer constructs in the transfection assays (Fig. 3), it seems unlikely that octamer sequence 3 had any role in silencing. Taken together, these results indicate that Oct-4 suppresses Ets-2 transactivation of IFNT promoter activity without binding to DNA.

Domain specificity of Oct-4 for the suppression effect on the boIFNT1 promoter.

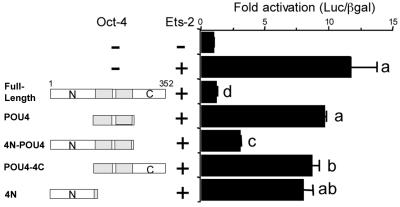

To determine what parts of the tripartite Oct-4 protein contributed to the suppression of the IFNT promoter, various domain deletion mutants were cotransfected with the Ets-2 expression construct and the −126luc reporter. In this series of experiments, Ets-2 activation of the IFNT promoter averaged about 12-fold, and Oct-4 suppression of reporter activity was always greater than 80% (Fig. 5). Only one truncated Oct-4 construct, the one with the N-terminal and POU domains intact but with the C terminus largely deleted, was an effective silencer. Neither the POU domain (aa 135 to 286 plus aa 349 to 352), the N-terminal domain alone, nor the POU domain plus the C-terminal domain was able to suppress Ets-2 transactivation of the −126 boIFNT1 promoter effectively. These data suggest that silencing requires both the N-terminal and the POU domains of Oct-4.

FIG. 5.

Domain specificity of Oct-4 in the suppression of the boIFNT1 promoter. The −1261uc reporter was transfected into JAr cells in either the absence (−) or the presence of expression vectors for Ets-2 (+) and for both Ets-2 and Oct-4 deletion constructs. The structures of the various Oct-4 deletion proteins are shown diagrammatically on the left, with shaded rectangles representing the POU domains. Reporter activity was normalized to the activity of cotransfected plasmid pRSVLTR-βgal. Results are means and standard errors. Activity is expressed as fold activation relative to basal activity. Data from four independent transfections, each run in triplicate, were log transformed to limit the heterogeneity of variance and were analyzed by least-squares analysis of variance (PC-SAS version 6.12; Statistical Analysis System Institute, Cary, N.C.). Pairwise comparisons among treatments were completed by using F test statistics (PC-SAS). Values marked with different letters (a, b, c, and d) differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Recombinant Ets-2 protein specifically binds to the POU domain of Oct-4 in vitro.

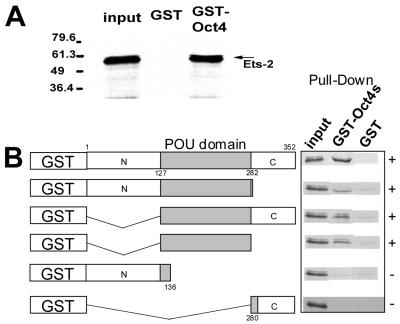

To explore the manner whereby Oct-4 interacts with Ets-2, GST pull-down assays were used. GST–Oct-4 and various truncation products were coupled to glutathione-Sepharose beads and tested for their abilities to trap Ets-2 that had been labeled with [35S]methionine by in vitro translation. As expected, 35S-labeled Ets-2 did form a complex with full-length GST–Oct-4 (Fig. 6A). In order to determine which domain of Oct-4 was responsible for the interaction, a series of Oct-4 truncations were tested in pull-down assays (Fig. 6B). All fusion proteins that contained an intact POU domain bound to Oct-4, but there was no interaction with either the C-terminal (aa 280 to 352) or the N-terminal (aa 1 to 136) peptides. Clearly, the POU domain of Oct-4 was sufficient to provide binding to Ets-2.

FIG. 6.

Recombinant Ets-2 protein binds specifically to the POU domain of Oct-4 in vitro. (A) Ets-2 protein interacts with Oct-4 protein in a GST pull-down assay. E. coli-expressed GST–Oct-4 fusion protein immobilized on Sepharose beads was mixed with [35S]methionine-labeled, in vitro-translated Ets-2 protein. Protein bound specifically was analyzed by SDS–10% PAGE. The first lane shows an analysis of the input protein (10% of in vitro-translated Ets-2). The second lane shows that immobilized GST failed to bind in vitro-translated Ets-2, while the third lane shows that GST–Oct-4 bound the radioactive protein. (B) Summary of the data from the pull-down assay, in which a series of Oct-4 truncations were tested for their ability to bind 35S-labeled Ets-2. The truncated proteins (shown diagrammatically on the left) were synthesized as GST fusion proteins and coupled to Sepharose. The ability of the proteins to bind 35S-labeled Ets-2 was then assessed in a pull-down assay. The data are consistent with the conclusion that the POU domain (aa 127 to 282) is required for Oct-4 to bind Ets-2.

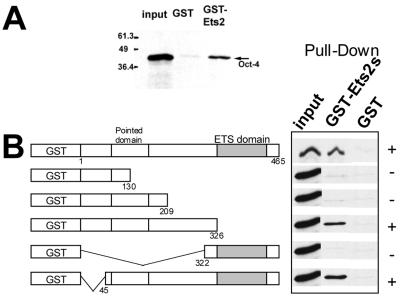

Recombinant Oct-4 binds to the transactivation domain of Ets-2 in vitro.

In this experiment, the experiment shown in Fig. 6 was reversed. GST-fused Ets-2 deletion mutants were coupled to glutathione-Sepharose and probed with 35 S-labeled Oct-4 (Fig. 7A). The results of a typical experiment out of three performed are shown in Fig. 7B. Polypeptide fragments representing the C terminus of Ets-2 (aa 322 to 465), which contains the DNA binding domain, and the first 130 or 209 aa (including the “pointed” domain; aa 68 to 168) of the N terminus of the protein failed to bind to Oct-4. However, two polypeptides (aa 1 to 326 and 45 to 465), both of which included a central sequence of Ets-2 between the pointed and DNA binding domains, exhibited binding activity.

FIG. 7.

Recombinant Oct-4 binds to a central domain of Ets-2 in vitro. (A) Oct-4 protein interacts with Ets-2 protein in a GST pull-down assay. GST–Ets-2 fusion protein and GST immobilized on Sepharose beads were mixed with [35S]methionine-labeled, in vitro-translated Oct-4. Bound protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE as described in the legend to Fig. 6. The first lane is input protein (10% of the in vitro translation mixture of Oct-4). (B) Summary of the data from the pull-down assay, in which a series of Ets-2 truncations (shown on the left) were tested for their ability to bind 35S-labeled Oct-4. The data indicate that a central domain within Ets-2 is required for binding to Oct-4.

Ets-2 associates with Oct-4 in vivo.

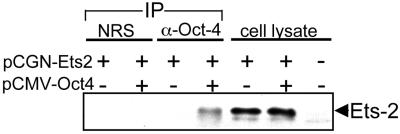

Transfection of JAr cells with the Ets-2 expression plasmid, followed 36 h later by direct analysis of whole-cell lysates by Western blotting with anti-Ets-2 antiserum, revealed a strong immunopositive band that was not detectable in untransfected control cells (Fig. 8, fifth and seventh lanes). However, the Ets-2 signal was observed in the untransfected cell lysate when larger amounts of the lysate were analyzed (data not shown). The same level of Ets-2 expression after transfection was present whether or not Oct-4 was coexpressed (Fig. 8, sixth lane).

FIG. 8.

Oct-4 binds Ets-2 in vivo. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from JAr cells that had been transiently transfected with 10 μg of pCGNEts-2 in either the presence or the absence of 10 μg of pCMV-Oct4. Protein G cross-linked with antiserum against Oct-4 (α-Oct-4) or nonimmune serum (NRS) was then added. Immune complexes were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-Ets-2 antiserum (first through fourth lanes). Blots show the presence of Ets-2 protein in whole-cell lysates (10 μg) of transfected cells (fifth and sixth lanes) and in nontransfected cells (seventh lane). The fourth lane shows that Ets-2 is immunoprecipitated with anti-Oct-4 antiserum only in cells coexpressing both proteins.

In order to demonstrate that Ets-2 and Oct-4 associated in vivo, JAr cells were transfected with the two expression vectors either alone or together. After 36 h, antiserum to Oct-4 was added to cell lysates, and the immune complexes were analyzed by Western blotting with an antiserum against Ets-2 (Fig. 8, first through fourth lanes). The Ets-2 band identified in the fifth and sixth lanes of Fig. 8 was noted only in cells that had been transfected with both pCMV-Oct4 and pCGNEts-2. These data suggest that Oct-4 can associate with Ets-2 in human JAr cells.

DISCUSSION

Oct-4 probably holds a key position in maintaining cells in a pluripotent state (33–35). Until the blastocyst stage in the mouse, cells that give rise to the trophoblast and those that will form the embryo proper express Oct-4. The consensus view is that Oct-4 prevents differentiation by maintaining the expression of key embryonic genes. As postulated here and elsewhere (22, 23), they may also silence the transcription of genes that are associated with differentiation into the trophectoderm. The positively regulated genes in the murine i.c.m. include FGF-4 and the transcriptional coactivator UTF1 (1, 27). A third potential target is the Glut-3 glucose transporter, whose expression mirrors that of Oct-4 (44). In contrast, two genes up-regulated in the trophectoderm of human embryos (the α- and β-subunit genes of hCG) are silenced by Oct-4 (22, 23). Surprisingly, Oct-4 control of the hCGα and hCGβ genes, two genes that must be expressed coordinately to produce the active hormone, is different. In the case of the hCGβ gene, an atypical octamer site localized at about −270 binds Oct-4 and is responsible for the silencing (so-called direct silencing; see below) (23). With hCGα, Oct-4 exerts its effects within a relatively narrow (−170 to −148) region of the promoter, but no direct binding to DNA is required (22). Instead, the suppression of transcription appears to be dependent upon interactions with other, presently unknown, protein factors. There is therefore a close parallel between the silencing of the hCGα gene and that of the IFNT gene described here.

Chorionic gonadotropin is a hormone confined to the primate order (40). In ruminants, the corpus luteum of pregnancy is prevented from undergoing luteolysis by the release of IFN-τ from the trophoblast prior to the formation of the placenta. Timely production of the hormone is crucial if the pregnancy is to be maintained (11). As with hCG, IFN-τ can first be detected as the blastocyst forms, although maximal production per cell is not reached for a few days, at a time when Oct-4 is fully down-regulated (54). Although initial experiments to demonstrate the effects of Oct-4 on the expression of transfected IFN-τ promoters in JAr cells indicated only a modest effect (9), which may be through endogenously expressed Ets-2, Oct-4 is clearly a potent silencer of IFN-τ promoters when the transactivator, Ets-2, is overexpressed (Fig. 2A and B).

Although there are several octamer-like binding sites in the IFNT promoter, none of these could bind Oct-4 strongly, and all could be eliminated without any effect on silencing (Fig. 3 and 4). These results rule out a direct mechanism of repression in which Oct-4 would cause silencing by docking to the promoter and interfering with the transcriptional process. Similarly, it seems unlikely that Oct-4 competes with Ets-2 or some other transcription factor for a site on the promoter (the so-called competition mechanism of repression). There is, for example, no obvious octamer binding site either overlapping or close to the Ets-2 site, and the entire proximal IFNT promoter region (−126 to −34) fails to compete with Oct-4 for binding to a double-stranded canonical octamer sequence (Fig. 4B).

As observed previously for the shorter −126 promoter (13), a modest transactivation of the −457 boIFNT1 promoter by Ets-2 was observed after the main Ets-2 binding site had been mutated (Fig. 3). This increase in activity was partially reversed when Oct-4 was expressed. Conceivably, there is a cryptic, although much weaker, Ets-2 enhancer site on the promoter. Alternatively, the effects could be indirect and mediated through the action of Ets-2 and Oct-4 on another gene.

Two other mechanisms have been proposed to cause the repression of eukaryotic genes, squelching and quenching (21). Squelching results from the ability of the silencer to sequester either the activator itself or some other molecule necessary for transactivation of the gene (6). Such a mechanism appears unlikely for Oct-4 repression of IFNT. Ets-2 did not, for example, have a reciprocal effect and prevent Oct-4 from transactivating a reporter gene through the 3×Oct enhancer (Fig. 2C). A second observation that appears to rule out squelching as the silencing mechanism is that Oct-4 interacts with Ets-2 through its POU domain (Fig. 6), yet the POU domain alone is ineffective as a silencer (Fig. 5). Clearly, Oct-4 is able to interact with Ets-2 both in vitro (Fig. 6 and 7) and in vivo (Fig. 8).

The fourth type of silencing, quenching, occurs when the silencer interferes with the ability of the DNA-bound transactivator to interact with the basal transcriptional machinery (21). Such a mechanism seems most consistent with the observed Oct-4 suppression of the IFNT promoter (Fig. 9). First, Oct-4 seems not to be required to bind to promoter DNA to exert its effect (Fig. 3 and 4). Instead, Oct-4 binds Ets-2, with its POU domain targeting a region between the pointed and DNA binding regions of Ets-2 (Fig. 6 and 7). Presumably, this interaction places the N terminus in a position to block transcription (Fig. 9). It may be significant that a functional transactivation domain of Ets-2 has been mapped to a region within aa 1 to 293 (7) and that the POU domain of octamer proteins forms functional complexes with several transcription factors, including C/EBP (15), Sox-2 (1, 3, 27), and the viral proteins EIA and E7 (5), although in each of these instances the outcome is up-regulation rather than silencing of the targeted promoters. It remains to be seen whether the experiments reported here can be mimicked with other types of cells and whether either the POU or the C-terminal domain of Oct-4 can be individually replaced by the homologous regions from other Oct proteins and still provide effective silencing.

FIG. 9.

Oct-4 likely silences IFNT gene transcription through a quenching mechanism involving binding to the transactivator Ets-2.

There is considerable similarity between the mechanism of Oct-4 suppression of the IFNT promoter and the silencing of myelin P0 gene transcription by a related octamer protein, Oct-6 (also known as SCIP and Tst-1), which is expressed in premyelinating Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes (17, 24, 55). In both instances, repression of transcription occurs through protein-protein interactions involving the POU domain and regardless of whether or not octamer binding sites in the promoters are deleted. Moreover, the N-terminal domain of the Oct protein appears to provide the specificity for the repression (24). Finally, just as Oct-4 is down-regulated as trophoblast cells form, Oct-6 expression is lost as myelinated cells begin to appear (17).

In conclusion, the findings of this study provide additional evidence that Oct-4 can function as a silencer as well as a transactivator. Oct-4 likely contributes to maintaining cells in an undifferentiated, pluripotent or totipotent state in two ways, by activating certain key genes and silencing others. This silencing, which for IFNT involves quenching of Ets-2 transactivation, may be a key mechanism that prevents cells of the i.c.m. from expressing products that direct differentiation toward the trophectoderm.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant R37HD21896 to R.M.R.

We thank H. R. Schöler, M. C. Ostrowski, and W. Herr for expression plasmids.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambrosetti D C, Basilico C, Dailey L. Synergistic activation of the fibroblast growth factor-4 enhancer by Sox2 and Oct-3 depends on protein-protein interactions facilitated by a specific spatial arrangement of factor binding sites. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6321–6329. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bazer F W, Spencer T E, Ott T L. Interferon tau: a novel pregnancy recognition signal. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1997;37:412–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1997.tb00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botquin V, Hess H, Fuhrmann G, Anastassiadis C, Gross M K, Vriend G, Schöler H R. New POU dimer configuration mediates antagonistic control of an osteopontin preimplantation enhancer by Oct-4 and Sox-2. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2073–2090. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brehm A, Ohbo K, Schöler H. The carboxy-terminal transactivation domain of Oct-4 acquires cell specificity through the POU domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:154–162. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brehm A, Ohbo K, Zwerschke W, Botquin V, Jansen-Durr P, Schöler H R. Synergism with germ line transcription factor Oct-4: viral oncoproteins share the ability to mimic a stem cell-specific activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2635–2643. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cahill M A, Ernst W H, Janknecht R, Nordheim A. Regulatory squelching. FEBS Lett. 1994;344:105–108. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chumakov A M, Chen D L, Chumakova E A, Koeffler H P. Localization of the c-ets-2 transactivation domain. J Virol. 1993;67:2421–2425. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2421-2425.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cormack B. Introduction of restriction endonuclease sites by PCR. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1997. pp. 8.5.1–8.5.5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cross J C, Leaman D W, Rutter W J, Roberts R M. Developmentally regulated transactivators interact with the trophoblast interferon promoter. J Interferon Res. 1992;12:578. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cross J C, Roberts R M. Constitutive and trophoblast-specific expression of a class of bovine interferon genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3817–3821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demmers K J, Derecka K, Flint A F. Trophoblast interferon and pregnancy. Reproduction. 2001;121:41–49. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1210041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Endoh H, Maruyama K, Masuhiro Y, Kobayashi Y, Goto M, Tai H, Yanagisawa J, Metzger D, Hashimoto S, Kato S. Purification and identification of p68 RNA helicase acting as a transcriptional coactivator specific for the activation function 1 of human estrogen receptor alpha. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5363–5372. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.Ezashi T, Ealy A D, Roberts R M. Control of interferon-tau gene expression by Ets2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7882–7887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farin C E, Imakawa K, Hansen T R, McDonnell J J, Murphy C N, Farin P W, Roberts R M. Expression of trophoblastic interferon genes in sheep and cattle. Biol Reprod. 1990;43:210–218. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatada E N, Chen-Kiang S, Scheidereit C. Interaction and functional interference of C/EBPbeta with octamer factors in immunoglobulin gene transcription. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:174–184. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200001)30:1<174::AID-IMMU174>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez-Ledezma J J, Sikes J D, Murphy C N, Watson A J, Schultz G A, Roberts R M. Expression of bovine trophoblast interferon in conceptuses derived by in vitro techniques. Biol Reprod. 1992;47:374–380. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod47.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaegle M, Mandemakers W, Broos L, Zwart R, Karis A, Visser P, Grosveld F, Meijer D. The POU factor Oct-6 and Schwann cell differentiation. Science. 1996;273:507–510. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5274.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson W, Jameson J L. Role of ets2 in cyclic AMP regulation of the human chorionic gonadotropin beta promoter. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;165:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirchhof N, Carnwath J W, Lemme E, Anastassiadis K, Schöler H, Niemann H. Expression pattern of oct-4 in preimplantation embryos of different species. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1698–1705. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.6.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leaman D W, Cross J C, Roberts R M. Multiple regulatory elements are required to direct trophoblast interferon gene expression in choriocarcinoma cells and trophectoderm. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:456–468. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.4.8052267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine M, Manley J L. Transcriptional repression of eukaryotic promoters. Cell. 1989;59:405–408. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu L, Leaman D, Villalta M, Roberts R M. Silencing of the gene for the alpha-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin by the embryonic transcription factor Oct-3/4. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1651–1658. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.11.9971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Roberts R M. Silencing of the gene for the beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin by the embryonic transcription factor Oct-3/4. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16683–16689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monuki E S, Kuhn R, Lemke G. Repression of the myelin P0 gene by the POU transcription factor SCIP. Mech Dev. 1993;42:15–32. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90095-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Natesan S, Rivera V M, Molinari E, Gilman M. Transcriptional squelching re-examined. Nature. 1997;390:349–350. doi: 10.1038/37019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nichols J, Zevnik B, Anastassiadis K, Niwa H, Klewe-Nebenius D, Chambers I, Schöler H, Smith A. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 1998;95:379–391. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishimoto M, Fukushima A, Okuda A, Muramatsu M. The gene for the embryonic stem cell coactivator UTF1 carries a regulatory element which selectively interacts with a complex composed of Oct-3/4 and Sox-2. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5453–5465. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niwa H, Miyazaki J, Smith A G. Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet. 2000;24:372–376. doi: 10.1038/74199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okamoto K, Okazawa H, Okuda A, Sakai M, Muramatsu M, Hamada H. A novel octamer binding transcription factor is differentially expressed in mouse embryonic cells. Cell. 1990;60:461–472. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orwig K E, Soares M J. Transcriptional activation of the decidual/trophoblast prolactin-related protein gene. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4032–4039. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.9.6954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ovitt C E, Schöler H R. The molecular biology of Oct-4 in the early mouse embryo. Mol Hum Reprod. 1998;4:1021–1031. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.11.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmieri S L, Peter W, Hess H, Schöler H R. Oct-4 transcription factor is differentially expressed in the mouse embryo during establishment of the first two extraembryonic cell lineages involved in implantation. Dev Biol. 1994;166:259–267. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pesce M, Anastassiadis K, Schöler H R. Oct-4: lessons of totipotency from embryonic stem cells. Cells Tissues Organs. 1999;165:144–152. doi: 10.1159/000016694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pesce M, Gross M K, Schöler H R. In line with our ancestors: Oct-4 and the mammalian germ. Bioessays. 1998;20:722–732. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199809)20:9<722::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pesce M, Schöler H R. Oct-4: control of totipotency and germline determination. Mol Reprod Dev. 2000;55:452–457. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(200004)55:4<452::AID-MRD14>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pestell R G, Albanese C, Watanabe G, Lee R J, Lastowiecki P, Zon L, Ostrowski M, Jameson J L. Stimulation of the P-450 side chain cleavage enzyme (CYP11A1) promoter through ras- and Ets-2-signaling pathways. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1084–1094. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.9.8885243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts R M, Cross J C, Leaman D W. Interferons as hormones of pregnancy. Endocr Rev. 1992;13:432–452. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-3-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts R M, Liu L, Alexenko A. New and atypical families of type I interferons in mammals: comparative functions, structures, and evolutionary relationships. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1997;56:287–325. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)61008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts R M, Liu L, Guo Q, Leaman D, Bixby J. The evolution of the type I interferons. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1998;18:805–816. doi: 10.1089/jir.1998.18.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts R M, Xie S, Mathialagan N. Maternal recognition of pregnancy. Biol Reprod. 1996;54:294–302. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod54.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosfjord E, Rizzino A. The octamer motif present in the Rex-1 promoter binds Oct-1 and Oct-3 expressed by EC cells and ES cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:1795–1802. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosner M H, Vigano M A, Ozato K, Timmons P M, Poirier F, Rigby P W, Staudt L M. A POU-domain transcription factor in early stem cells and germ cells of the mammalian embryo. Nature. 1990;345:686–692. doi: 10.1038/345686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryan A K, Rosenfeld M G. POU domain family values: flexibility, partnerships, and developmental codes. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1207–1225. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.10.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saijoh Y, Fujii H, Meno C, Sato M, Hirota Y, Nagamatsu S, Ikeda M, Hamada H. Identification of putative downstream genes of Oct-3, a pluripotent cell-specific transcription factor. Genes Cells. 1996;1:239–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.d01-237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schöler H R, Ciesiolka T, Gruss P. A nexus between Oct-4 and E1A: implications for gene regulation in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 1991;66:291–304. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90619-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schöler H R, Dressler G R, Balling R, Rohdewohld H, Gruss P. Oct-4: a germline-specific transcription factor mapping to the mouse t-complex. EMBO J. 1990;9:2185–2195. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07388.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schöler H R, Ruppert S, Suzuki N, Chowdhury K, Gruss P. New type of POU domain in germ line-specific protein Oct-4. Nature. 1990;344:435–439. doi: 10.1038/344435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh H, Sen R, Baltimore D, Sharp P A. A nuclear factor that binds to a conserved sequence motif in transcriptional control elements of immunoglobulin genes. Nature. 1986;319:154–158. doi: 10.1038/319154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stacey K J, Fowles L F, Colman M S, Ostrowski M C, Hume D A. Regulation of urokinase-type plasminogen activator gene transcription by macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3430–3441. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steger D J, Altschmied J, Buscher M, Mellon P L. Evolution of placenta-specific gene expression: comparison of the equine and human gonadotropin alpha-subunit genes. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5:243–255. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-2-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun Y, Duckworth M L. Identification of a placental-specific enhancer in the rat placental lactogen II gene that contains binding sites for members of the Ets and AP-1 (activator protein 1) families of transcription factors. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:385–399. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.3.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tanaka M, Herr W. Differential transcriptional activation by Oct-1 and Oct-2: interdependent activation domains induce Oct-2 phosphorylation. Cell. 1990;60:375–386. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90589-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Eijk M J, van Rooijen M A, Modina S, Scesi L, Folkers G, van Tol H T, Bevers M M, Fisher S R, Lewin H A, Rakacolli D, Galli C, de Vaureix C, Trounson A O, Mummery C L, Gandolfi F. Molecular cloning, genetic mapping, and developmental expression of bovine POU5F1. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:1093–1103. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.5.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weinstein D E, Burrola P G, Lemke G. Premature Schwann cell differentiation and hypermyelination in mice expressing a targeted antagonist of the POU transcription factor SCIP. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1995;6:212–229. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1995.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamamoto H, Flannery M L, Kupriyanov S, Pearce J, McKercher S R, Henkel G W, Maki R A, Werb Z, Oshima R G. Defective trophoblast function in mice with a targeted mutation of Ets2. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1315–1326. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang B S, Hauser C A, Henkel G, Colman M S, Van Beveren C, Stacey K J, Hume D A, Maki R A, Ostrowski M C. Ras-mediated phosphorylation of a conserved threonine residue enhances the transactivation activities of c-Ets1 and c-Ets2. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:538–547. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.2.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yuan H, Corbi N, Basilico C, Dailey L. Developmental-specific activity of the FGF-4 enhancer requires the synergistic action of Sox2 and Oct-3. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2635–2645. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]