Abstract

The narrow genetic base of tomato poses serious challenges in breeding. Hence, with the advent of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)-associated protein9 (CRISPR/Cas9) genome editing, fast and efficient breeding has become possible in tomato breeding. Many traits have been edited and functionally characterized using CRISPR/Cas9 in tomato such as plant architecture and flower characters (e.g. leaf, stem, flower, male sterility, fruit, parthenocarpy), fruit ripening, quality and nutrition (e.g., lycopene, carotenoid, GABA, TSS, anthocyanin, shelf-life), disease resistance (e.g. TYLCV, powdery mildew, late blight), abiotic stress tolerance (e.g. heat, drought, salinity), C-N metabolism, and herbicide resistance. CRISPR/Cas9 has been proven in introgression of de novo domestication of elite traits from wild relatives to the cultivated tomato and vice versa. Innovations in CRISPR/Cas allow the use of online tools for single guide RNA design and multiplexing, cloning (e.g. Golden Gate cloning, GoldenBraid, and BioBrick technology), robust CRISPR/Cas constructs, efficient transformation protocols such as Agrobacterium, and DNA-free protoplast method for Cas9-gRNAs ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) complex, Cas9 variants like PAM-free Cas12a, and Cas9-NG/XNG-Cas9, homologous recombination (HR)-based gene knock-in (HKI) by geminivirus replicon, and base/prime editing (Target-AID technology). This mini-review highlights the current research advances in CRISPR/Cas for fast and efficient breeding of tomato.

Keywords: abiotic stress, biotic stress, CRISPR/Cas9, plant architecture, flower, fruit quality, genome editing, tomato

Introduction

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) is one of the most economically important vegetable crops, which is consumed as fresh and processed products. Tomato is considered a functional and protective food because of its health-beneficial compounds such as vitamins A and C, minerals, and antioxidants mainly lycopene and beta-carotene (Causse et al., 2016). Breeding new tomato cultivars with current consumers’ demand and processing industrial requirements is very important, which needs wide genetic resources with target traits. Natural genetic variability has led to the development of many varieties with agronomic traits. Initially, induced mutagenesis caused by chemical or physical mutagens has been successfully applied in breeding, but it is quite labor-intensive, cumbersome, and time-consuming. Similarly, conventional breeding also rely upon phenotypic selection and requires a long breeding cycle. Hence, to overcome these issues the availability of genome sequence (900 Mb) allows functional genomics and rapid breeding via dissecting complex traits (Tomato Genome Consortium, 2012). Furthermore, tomato pan-genomes have been reported for 1000 accessions (Alonge et al., 2020) and 725 cultivated and wild species (Gao et al., 2019). Recently, progress in genomics-assisted breeding has been reviewed for accelerated tomato improvement (Hanak et al., 2022; Tiwari et al., 2022).

To address the issues faced with conventional breeding, chemical/physical mutagenesis and trangenics, plant breeding has become much easier and highly efficient while using the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated 9 protein (CRISPR/Cas9) genome editing tool. CRISPR/Cas9 is a powerful and precise genome editing technology that allows trait-specific targeted mutants and functional characterization of genes. CRISPR/Cas9 has been used to edit various traits in tomato (Rothan et al., 2019; Vu et al., 2020a; Chandrasekaran et al., 2021; Salava et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2021; Chaudhuri et al., 2022). Recently, CRISPR-edited GABA-rich tomatoes first entered the food market (Waltz, 2022). In this mini-review, we provide a brief overview of CRISPR/Cas9, its current application in tomato trait modifications, and research advances on sgRNA designing, cloning, transformation, and regulatory aspects.

CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technology

CRISPR/Cas9 protein functions on the principles of a bacterial or archaeal adaptive immunity system that confronts the invading viruses or phages. CRISPR/Cas has been categorized into several types and sub-types such as the class 1 (type I, III, and IV) includes numerous proteins to form complexes, whereas the class 2 (type II, V, and VI) includes only one protein. Among them, Cas9 is the most widely deployed machinery in crop improvement. CRISPR/Cas9 uses specific, designed nucleases to cause double-stranded break (DSB) in DNA (dsDNA). Further, the DSB is repaired by the mechanisms called non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR)/homologus recombination (HR). The NHEJ mechanism is error-prone, allows random small insertions or deletions and substitutions, and probably causes gene knock-out (KO) mutations. The HDR mechanism mostly generates point mutations or deletions caused by gene knock-in (KI), but this method has a very low success rate so far. CRISPR/Cas9 makes breeding much easier by producing gene knock-out mutants for desired traits. Gene knock-in is possible through HDR by providing template DNA with overlapping flanking regions. Nevertheless, CRISPR/Cas9 has many limitations, such as the availability of NGG protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) motifs in the genome sequence. Hence, emphasis has been driven to diversify Cas9 proteins and search for other Cas9 proteins in different bacteria, which have different PAM sequences.

Strategies and advances in CRISPR/Cas9 technology

Guide RNA and CRISPR/Cas9 construct design

CRISPR/Cas9 is an RNA-guided genome editing system. The sgRNAs direct Cas9 nuclease to recognize the target DNA sequence to interrupt transcriptional regulation. The gRNA-Cas9 complex identifies the target sequence by gRNA-DNA pairing between the 5’-end sequence of gRNA spacer and one DNA strand (complementary stand of protospacer). Cas9 requires the PAM sequence at the target site. The approximately 20 nucleotide-long gRNA spacer sequence could be readily programmed to target DNA sites with PAM using the online tools available. The freely available online tools for sgRNA design and quality check are CRISPRdirect (https://crispr.dbcls.jp), CRISPR-P (http://cbi.hzau.edu.cn/cgi-bin/CRISPR), CRISPR-PLANT (http://omap.org/crispr/index.html), CRISPR-GE (http://skl.scau.edu.cn/), Breaking-Cas (http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/breakingcas/), CRISPOR.org (http://crispor.org), CRISPR-BETs (Wu et al., 2022) and so on. The MoClo Toolkit (Weber et al., 2011) to assemble sgRNAs constructs and Golden Gate cloning (Engler et al., 2014) protocols have been used in CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in plants.

The Golden Gate cloning strategy is a very fast and flexible assembly for CRISPR/Cas construct designing (Engler et al., 2014) and applied effectively in tomato (Brooks et al., 2014; Gao et al., 2021; Tran et al., 2021; Do et al., 2022). A new GoldenBraid (GB) assembly of vector construction has shown promising results in tomato (Vázquez-Vilar et al., 2021). An innovative strategy called BioBrick technology consisting of pHNCas9 and pHNCas9HT binary vectors has been devised for functional genomics and genome engineering in plants (Hu et al., 2019). These studies confirm that the CRISPR toolbox can easily carry out single or multi-site editing on multiple genes in tomato.

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation is the most commonly used method in CRISPR/Cas9 research in plants including tomato (Lin et al., 2022b; Yang et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2022). Besides, polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based protoplast-mediated transformation and particle bombardment or biolistic methods have also been exhibited in tomato. A notable example elucidates the diverse behavior of Cas9 by engineering QTLs via mutagenesis in the cis-regulatory regions of the CLV3 (Clavata3) gene in tomato (Rodríguez-Leal et al., 2017). Since, sgRNAs and Cas9 gene are eliminated in the next T1 generation upon segregation, CRISPR/Cas9 is considered a safe, rapid, and environmentally friendly next-generation breeding technology in crop plants.

DNA-free protoplast-mediated transformation

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation cannot be used for the delivery of Cas9/ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) complexes. Therefore, preassembled Cas9-gRNA RNPs have been directly delivered into the plant cells via protoplast-mediated transformation by polyethylene glycol (PEG) fusion or biolistic methods. To remove CRISPR/Cas background, the Cas9-gRNA RNPs system is completely DNA-free and devoid of genetic segregation (Liu et al., 2020b; Thiruppathi, 2022). There are several advantages of Cas9-gRNA RNPs delivery, such as: i) avoiding progeny screening by selfing or backcrossing; ii) no off-target effects; iii) better control over CRISPR/Cas endonuclease; iv) direct and easy mutagenesis process after transfection without any lagging phase; and v) direct delivery of Cas9-sgRNA assembly or preassembled isolated RNPs into the plant cells. However, RNP’s system has problems like delivery through the plant cells and regeneration from cell-wall-free cells. As a result, protoplast culture protocol is dependent on genotype, species, tissue-specific, and cell wall responses. Thus, minimizing the proportion of off-targets and checking the possibilities of transgene integration is important for enhancing precise Cas9 endonuclease activity.

CRISPR/Cas9 variants (PAM-free Cas12a, and Cas9-NG/XNG-Cas9)

Cas9 can be used to edit DNA highly efficiently to target gene knock-outs within coding sequences or random changes in non-coding sequences like cis-elements for random promoter engineering (Rodríguez-Leal et al., 2017). Further, the elimination of Cas9 components from the plant genome via selfing or backcrossing is possible for diploid tomato. The availability of PAM sequences (2-5 bp) is highly lacking in the genome, so it is difficult to edit target genes. Hence, diversity in protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence specificities has become a key requirement of CRISPR/Cas9.

First, PAM-free nucleases have been devised through natural orthologous mining and protein engineering. This can be overcome by Cas9 variants with different PAM-specific sequences, such as Cas12a (class II, type V) requires PAM sequences (5’-TTTN-3’). This is quite useful for the tomato genome, as it has AT-rich sequences and uses Cas12a nuclease. Hence, new variants of Cas9 with diverse sequence specificities of PAM would be greatly useful for the restoration of genetic diversity. The Cas9 variant, a PAM-free Cas12a nuclease, is smaller in size and highly thermostable than Cas9 (Vu et al., 2021). Cas12a (LbCas12a or LbCpf1) from Lachnospiraceae bacteria is a new category of the CRISPR system, which is quite analogous to Cas9 and enables editing of AT-rich genomic regions like the 5’ and 3’ UTR and promoter domains. Cas9 endonuclease recognizes G-rich PAM sequences and produces a blunt end cut, whereas Cas12a has a shorter crRNA by 60 nucleotides and no spacer is required, tracrRNA is not required to generate mature crRNA, and recognizes T-rich PAM sequences, producing cohesive ends (Wada et al., 2022). Thus, numerous Cas9 and Cas12a variants are in the process of facilitating sgRNA design and genome editing research.

PAM-free Cas9 has advantages like: i) it can target any sequence; ii) selection of the target site is simple and flexible with more on-target and less off-target; iii) it allows easy placement of base-editing over specific nucleotides; and iv) it is beneficial for multiplexing because only one nuclease targets most genes. Nevertheless, a major limitation of PAM-free nuclease is that the gRNA that is expressed from the DNA constructs would self-target the parent DNA immediately, ultimately leading to unsuccessful results. Another drawback is that a nuclease without a specific PAM would search every sequence in the genome and would take much longer time to find the target sequence, hence increasing the chance of off-targets. Importantly, Cas12a has much scope for PAM-free nuclease activity in plants. Therefore, the development of a nuclease repertoire could be a novel way by which any gene sequence can be targeted by the CRISPR/Cas system.

SpCas9, the most widely used and powerful genome editing tool, requires NGG PAM; thus, its use has been restricted to genomic regions lacking in NGG PAM. The SPCas9 variants xCas9 and Cas9NG have been developed to recognize NG, GAA, and GAT PAMs in human cells. According to Niu et al., 2020, the SpCas9 variants Cas9-NG and XNG-Cas9 can recognize a wide range of NG PAM sites in tomato. Further, a new RNA-guided CRISPR activation (CRISPR-Act3.0) system has been introduced in plants for simultaneous editing of multiple genes based on the deactivated Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (dSpCas9) and demonstrated in tomato (Pan et al., 2021). This study provides a substantial toolbox for efficient gene activation, an improvement over the CRISPR technology in plants.

Homology-directed repair and virus-induced genome editing

Precise genome editing is emerging as a promising technology for trait modifications in crops. CRISPR/Cas9 has provided a versatile and efficient option for inducing DSBs in the plant genome. DSB repair by NHEJ can be error-prone and result in partial insertion-deletion that can lead to gene knock-out (KO). On the contrary, DSB repair by HDR requires donor template DNA with homologous flanking sequences that allow gene KI mechanism. NHEJ is the most commonly deployed to develop KO mutants, whereas HDR or KI is promising but has a low success rate in eukaryotic cells. Therefore, the KI mechanism requires more research to handle the technical difficulties in placing the donor templates in the vicinity of the DSB in the recipient plant cells.

Agrobacterium-mediated delivery mechanism is most commonly applied in plants, but it is less efficient for HDR-mediated gene editing. Therefore, to address these issues virus-induced genome editing (VIGE) involves plant virus-derived vectors for fast and efficient delivery of sgRNAs (Butler et al., 2016) and has been deployed in tomato. HDR or KI gene editing using the CRISPR/LbCpf1-geminiviral multi-replicon system has increased the editing efficiency by three-fold compared to Cas9-based single-replicon in tomato (Vu et al., 2020b). HR-based knock-in (HKI) frequency has been continuously refined for precision editing in tomato using a combination of Cas9 and a geminivirus replicon, LbCas12a (LbBCpf1), with multi-replicons. Further, HKI could be improved by reengineering temperature-tolerant Cas12a to speed up tomato breeding. Despite a high success rate in plants using geminivirus replicons, the majority of the studies used selection markers with edited alleles. This indicates that geminivirus replicon-based genome editing is still challenging without the use of selection markers for selecting edited lines. Hence, the development of marker-free and selection-free mutants requires further refinement. Thus, CRISPR/Cas9-induced gene replacement via the HDR mechanism provides an innovative breeding method in tomato.

Base/prime editing (Target-AID technology)

The Cas9 nuclease results in DSBs with a high risk of off-target effects. As a result, base editing is a novel CRISPR/Cas9 system approach for editing a single base without DSB or HDR and without donor DNA. Base editing allows mostly transition base changes from C/G to T/A (cytosine base editor, CBE), or A/T to G/C (adenine base editor, ABE), but no CRISPR system has been reported until now for transversion base changes in the plant (Lu et al., 2021; Sretenovic et al., 2021). The ABE has emerged as a boon to gaining gene function. It has been reported that ABE is preferred over CBE in plants because ABE produces fewer off-targets than CBE. Second, the Target activation-induced cytidine deaminase (Target-AID) technology consists of Petromyzon marinus cytidine deaminase1 (PmCDA1) fused with nuclease-deficient Cas9 (dCas9) or nCas9 (nickase Cas9 has single-strand DNA cleavage activity). Target-AID using dCas9 results in highly efficient and accurate substitution of C to T, whereas the use of nCas9 causes base substitution and insertion-deletion in the target sites at high efficiency to introduce point mutations (C to T or A to G) without any off-target (Kawaguchi et al., 2021). Third, a recent approach to substitution called prime editing or precise editing has been announced for medium-length DNA using the microhomology-mediated end-joining method. Prime editing technology has been used in animals and monocots, but it is more difficult to apply in dicots. Base or prime editing can easily edit a single base substitution, but problems arise when editing more bases. Several modifications of CRISPR/Cas9 are available for modifying target gene sequences from a single base by base-editors and prime-editors to several kilobases with HKI technique (Vu et al. 2020b). The HKI is a viable option for precise editing. But due to its low frequency and complexity in design, it can be used for modification on a single base or thousands of bases (Vu et al. 2020b). Thus, as a result of a fusion of Cas9 with Target-AID, marker-free mutant plants have been developed with homozygous heritable DNA substitutions, thus demonstrating the feasibility of base editing in tomato improvement.

Applications of CRISPR/Cas9 in tomato

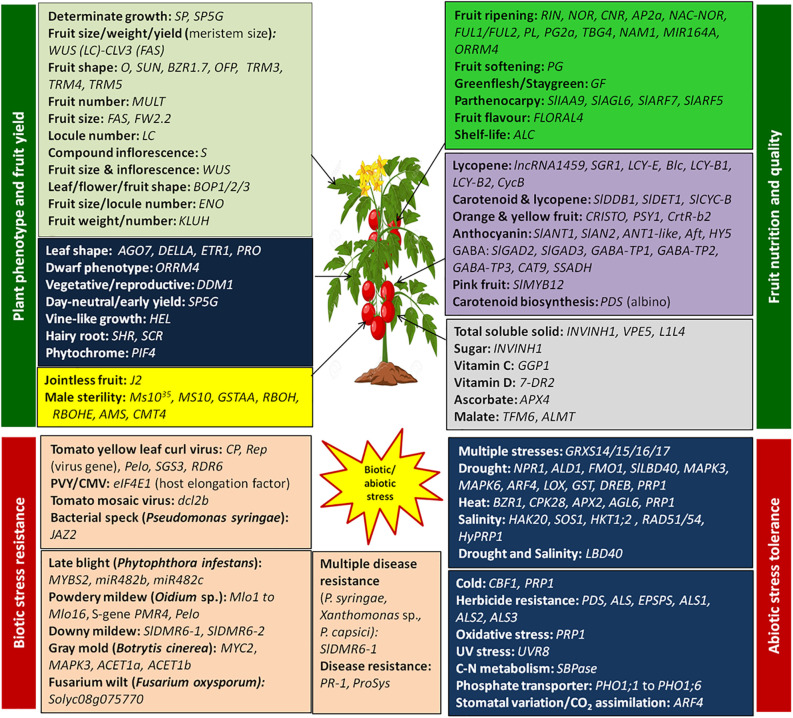

CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing has revolutionized crop breeding, including tomatoes. CRISPR/Cas9 is the most commonly used genome editing system for precise, efficient, easy, versatile, cost-effective, and targeted gene editing at the desired genomic regions. After the first report in 2013, this technology has been used extensively to edit tomato genotypes. The successful examples of the application of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in tomatoes are summarized in Table 1 . Figure 1 illustrates various genes demonstrated in tomato traits modification.

Table 1.

Application of CRISPR/Cas9 technology in tomato improvement for plant architecture, flower, fruit and biotic/abiotic stress resistance-related traits.

| Trait | Genotype | Target gene | Gene ID | CRISPR (DNA repair) |

Transformation | Genome editing effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant architecture, flower and fruit traits | |||||||

| Plant architecture, lycopene, fruit weight, size, number | S. pimpinellifolium |

SP, O, MULT, FAS FW2.2, CNR, CycB |

Solyc06g074350, Solyc02g085500, Solyc02g077390, Solyc11g071380, Solyc02g077920 Solyc04g040190 |

Cas9 (knockout) |

Agrobacterium | Determinate growth habit (SP), increased fruit size (FAS), shape (O), number (MULT), fruit weight (FW2.2), and very high lycopene (CycB) content | Zsögön et al., 2018 |

| Inflorescence, fruit size, weight, yield | M82, S. pimpinellifolium |

WUS/LC, CLV3/FAS SP, S |

Solyc02g083950,Solyc11g071380, Solyc06g074350, Solyc02g077390 |

Cas9 (knockout) |

Agrobacterium | Meristem size regulator (LC-FAS), increased compound inflorescence, locule number, fruit weight, size, and yield | Rodríguez-Leal et al., 2017 |

| Plant growth habit, fruit | S. pimpinellifolium |

SP, SP5G, CLV3, WUS, GGP1 |

Solyc06g074350, Solyc05g053850, Solyc11g071380, Solyc02g083950, Solyc02g091510 |

Cas9 (knockout) |

Agrobacterium | Determinate growth habit, compact plants, synchronous fruit ripening and enlarged fruit size | Li et al., 2018d |

| Plant growth habit, flower | M82 | SP5G | Solyc05g053850 | Cas9 (knockout) |

Agrobacterium | Rapid flowering, compact determinate growth habit and early yield | Soyk et al., 2017 |

| Plant growth habit | Red Setter |

SP, SP5G |

Solyc06g074350, Solyc05g053850 |

Cas9 (Knockin/RNPs) |

Protoplast (PEG) | Protoplast-mediated transformation protocols | Liu et al., 2022 |

| Plant regeneration | S. peruvianum |

SGS3, RDR6, PR-1, ProSys, Mlo1 |

Solyc04g025300, Solyc04g014870,Solyc08g075820, Solyc09g006005, Solyc05g051750, Solyc04g049090 |

Cas9 (Knockin/RNPs) |

Protoplast (PEG) | No chromosomal changes or unintended genome editing sites, and heritable changes | Lin et al., 2022a |

| Plant regeneration | Micro-Tom | AGO7 | Solyc01g010970 | Cas9 (CBEs/ABEs) |

Protoplast (PEG) |

Successful application of cytosine base editors (CBEs) and adenine base editors (ABEs) in rice, tomato and poplar | Sretenovic et al., 2021 |

| Plant phenotype | Micro-Tom |

PDS, PIF4 |

Solyc03g123760, Solyc07g043580 |

Cas9 (knockout) |

Agrobacterium | High frequencies of homozygous and biallelic albino mutants | Pan et al., 2016 |

| Plant phenotype | Ailsa Craig and Micro-Tom |

PDS | NM_001247166 | Cas9 (knockout) |

Agrobacterium | Albino mutants | Li et al., 2018c |

| Plant regeneration | Red Setter, Ailsa Craig, M82, Moneymaker |

SP, SP5G |

Solyc06g074350, Solyc05g053850 |

Cas9 (RNPs) |

Protoplast (PEG-Ca2+) | Improved protoplast isolation and shoot regeneration | Liu et al., 2022 |

| Plant regeneration | Solanum spp. |

SHR, SCR |

Solyc02g092370, Solyc10g074680 | Cas9 (knockout) |

A.

rhizogenes |

Hairy root transformation | Ron et al., 2014 |

| Dwarf plant | Moneymaker | PRO | Solyc11g011260 | Cas9 (knockout) |

Agrobacterium | Gibberellins-responsive dominant dwarf mutant with loss of function and deletion in DELLA allele | Tomlinson et al., 2019 |

| Leaf shape | M82 | AGO7 |

Solyc01g010970, Solyc07g021170, Solyc08g041770, Solyc12g044760 |

Cas9 (knockout) |

Agrobacterium | Change in leaf shape from compound flat to needle like leaves | Brooks et al., 2014 |

| Leaf shape | Micro-Tom |

DELLA, ETR1 |

Solyc11g011260, Solyc12g011330 |

Cas9 (base editing, Target-AID) |

Agrobacterium | Reduced serrated leaflets and insensitivity to ethylene | Shimatani et al., 2017 |

| Male sterility | Micro-Tom |

Ms1035

, GSTAA |

Solyc02g079810, Solyc02g081340 |

Cas9 (knockout) |

Agrobacterium | Male-sterile line with a green hypocotyl or trichome density | Liu et al., 2021a |

| Male sterility | KS-13 | MS10 | Solyc02g079810 | Cas9 (knockout) |

Agrobacterium | Male sterile line | Jung et al., 2020 |

| Male sterility | Alisa Craig | RBOH, RBOHE | Solyc01g099620, Solyc07g042460 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Male sterile line | Dai et al., 2022 |

| Male sterility | Ailsa Craig | AMS | QDO73362.1 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Non-viable pollens | Bao et al., 2022 |

| Male sterility | Ailsa Craig | CMT4 | Solyc08g005400 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Suppressed pollen tube growth | Guo et al., 2022 |

| Jointless fruit | M82 | J2 | Solyc12g038510, | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Jointless inflorescence, large sepals | Roldan et al., 2017 |

| Leaf, flower, fruit shape | M82 |

BOP1/2/3

(TMF) |

Solyc04g040220, Solyc10g079460, Solyc10g079750 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Defects in fruit shape and altered leaf | Xu et al., 2016 |

| Fruit size, locule number | S. pimpinellifolium | ENO | Solyc03g117230 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Increased fruit locule number, fruit size and yield | Yuste-Lisbona et al., 2020 |

| Fruit weight, number | S. pimpinellifolium |

KLUH

(CYP78A family) |

M9 SNP | Cas9 (knock-out) | Agrobacterium | Increased fruit weight and decreased number of small fruits | Li et al., 2022b |

| Fruit size | Ailsa Craig |

SUN, BZR1.7 |

Solyc10g079240, Solyc10g076390 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Elongated fruit shape | Yu et al., 2022 |

| Fruit size | S. lycopersicum, S. pimpinellifolium |

TRM3/4/5, OFP |

Solyc07g008670, Solyc10g076180 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Slightly flatter fruit | Wu et al., 2018 |

| Fruit ripening | Micro-Tom |

MIR164A

(targets: NAM2, NAM3) |

Solyc03g115850, Solyc06g069710 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Accelerated fruit ripening | Lin et al., 2022b |

| Fruit ripening | Ailsa Craig | RIN | Solyc05g012020 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Partial ripening and moderate red pigmentation | Ito et al., 2015; Ito et al., 2017; Ito et al., 2020 |

| Fruit ripening | Ailsa Craig |

NOR, CNR |

Solyc10g006880

Solyc02g077920 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Delayed ripening by 2-3 days | Gao et al., 2019 |

| Fruit ripening | Moneyberg, Ailsa Craig |

AP2a, NAC-NOR, FUL1, FUL2 |

Solyc03g044300, Solyc10g006880, Solyc06g069430, Solyc03g114830 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Early fruit ripening but not fully ripen | Wang et al., 2019a |

| Fruit ripening | Ailsa Craig |

PL, PG2a, TBG4 |

Solyc03g111690, Solyc10g080210, Solyc12g008840, |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Influenced fruit firmness, weight and color | Wang et al., 2019a |

| Fruit ripening | Ailsa Craig | NAM1 | Solyc06g060230 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Regulates fruit ripening | Gao et al., 2021 |

| Fruit ripening | Moneyberg, Ailsa Craig |

FUL1, FUL2 |

Solyc06g069430, Solyc03g114830 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Independent/overlapping functions in fruit ripening | Wang et al., 2019a |

| Fruit ripening | Micro-Tom | ORRM4 | - | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Involved in RNA editing of transcripts | Yang et al., 2017 |

| Parthenocarpy | Micro-Tom, Ailsa Craig | IAA9 | Solyc04g076850 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Leaf shape changes and parthenocarpic | Ueta et al., 2017 |

| Parthenocarpy | MP-1 | AGL6 | Solyc01g093960 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Parthenocarpic fruit and heat stress tolerance | Klap et al., 2017 |

| Fruit flavor | F6 (RILs) | FLORAL4 | Solyc04g063350 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Increased phenylalanine volatile | Tikunov et al., 2020 |

| Lycopene | – | lncRNA1459 |

KT963310, KT963311 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Reduced ethylene and lycopene | Li et al., 2018a |

| Lycopene | Ailsa Craig |

SGR1, LCY-E, Blc, LCY-B1, LCY-B2 |

DQ100158, EU533951, XM_010313794, EF650013, AF254793 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Increased lycopene | Li et al., 2018b |

| Lycopene | S. pimpinellifolium | CycB | Solyc04g040190 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | High lycopene content | Zsögön et al., 2018 |

| Carotenoid, chlorophyll, B. cinerea | Moneymaker, San Marzano |

GF | Solyc08g080090 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | high carotenoids, chlorophylls and Botrytis cinerea resistance | Gianoglio et al., 2022 |

| Yellow fruit | Red Setter |

Psy1, CrtR-b2 |

Solyc03g031860, Solyc03g007960 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Yellow flesh color fruit | D’Ambrosio et al., 2018 |

| Carotenoid | Periyakulam 1 (PKM1) | CRTISO | AF416727 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Complete knockout of protein function | Jayaraj et al., 2021 |

| Pink fruit | Inbred lines | MYB12 | Solyc01g079620 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Pink color fruit | Deng et al., 2018 |

| Orange and yellow fruit | Micro-Tom |

CRISTO, PSY1 |

- | Cas9 (knockin/geminiviral replicon) | Agrobacterium | High editing efficiency | Dahan-Meir et al., 2018 |

| Yellow fruit | M82, S. pimpinellifolium | PSY1 | Solyc03g031860 | Cas9 (knockin) |

Agrobacterium | Yellow fruit | Hayut et al., 2017 |

| Carotenoid, lycopene | Micro-Tom |

DDB1, DET1, CYC-B |

Solyc02g021650, Solyc01g056340, Solyc06g074240 |

Cas9 (Target-AID base editing) |

Agrobacterium | Increased carotenoid, lycopene, and β-carotene content | Hunziker et al. (2020) |

| Anthocyanin | Micro-Tom | ANT1 | Solyc10g086260 | Cas9 (Geminivirus replicon) | Agrobacterium | High anthocyanin content | Cˇermák et al., 2015; Vu et al., 2020b |

| Anthocyanin | Indigo Rose |

AN2, ANT1, ANT1- like, R2R3-MYB TF AN2-like/Anthocyanin fruit (Aft) |

Solyc10g086250, Solyc10g086260, Solyc10g086270, Solyc10g086290 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Decreased anthocyanin content | Yan et al., 2020; Zhi et al., 2020 |

| Anthocyanin | Indigo Rose | HY5 | Solyc08g061130 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Decreased anthocyanin | Qiu et al., 2019 |

| GABA | Micro-Tom |

GAD2, GAD3 |

B1Q3F1 FB1Q3F2 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Increased GABA content | Nonaka et al., 2017 |

| GABA | Ailsa Craig and Micro-Tom |

GABA-TP1, GABA-TP2, GABA-TP3, CAT9, SSADH |

AY240229, AY240230, AY240231, XM_004248503, NM_001246912 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Increased GABA content | Li et al., 2018c |

| Total soluble solid (TSS) | M82 |

INVINH1, VPE5 |

Solyc12g099200, Solyc12g095910 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Increased glucose, fructose, and TSS contents | Wang et al., 2021a |

| Sugar | Suzukoma | INVINH1 | Solyc12g099200 | Cas9 (knockout, Target-AID base editing) |

Agrobacterium | High sugar content | Kawaguchi et al., 2021 |

| Vitamin D | Moneymaker | 7-DR2 | Solyc06g074090 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Increased 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC) level | Li et al., 2022a |

| Ascorbate | Micro-Tom | APX4 | Solyc06g005150 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Increased ascorbate content | Do et al., 2022 |

| Malate | S. lycopersicum, S. pimpinellifolium, S.l. var cerasiforme |

TFM6, ALMT |

Solyc06g072910, Solyc06g072920 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Reduced malate content | Ye et al., 2017 |

| Shelf-life | M82 | ALC | FJ404469 | Cas9 (knockin) | Agrobacterium | Extended shelf-life | Yu et al., 2017 |

| Fruit softening | Micro-Tom | PG | solyc10g080210 | Cas9 (knockout) | A. rhizogenes | Delayed fruit softening | Nie et al., 2022 |

| Biotic stress resistance | |||||||

| TYLCV | Moneymaker |

CP, Rep

(virus gene) |

- | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Resistance | Tashkandi et al., 2018 |

| TYLCV | Moneymaker | rgsCaM promoter | - | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Efficiency of an inducible promoter | Faal et al., 2020 |

| TYLCV, Powdery mildew | BN-86 |

Pelo, Mlo1 |

Solyc04g009810, Solyc04g049090 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | High resistance | Pramanik et al., 2021 |

| ToMV | Ailsa Craig | DCL2b | – | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Resistance | Wang et al., 2018 |

| Bacterial speck (Pseudomonas syringae) | Moneymaker | JAZ2 | Solyc12g009220 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Resistance | Ortigosa et al., 2019 |

| Late blight (Phytophthora infestans) | Alisa Craig | MYBS2 | Solyc04g008870 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | High resistance | Liu et al., 2021b |

| Powdery mildew (Oidium sp.) | Moneymaker | Mlo1 | Solyc04g049090 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Resistance | Nekrasov et al., 2017 |

| Powdery mildew | Moneymaker | PMR4 | Solyc07g053980 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Reduced resistance | Martínez et al., 2020 |

| Downy mildew | FL8000 | DMR6-1, DMR6-2 |

Solyc03g080190, Solyc06g073080 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | High resistance | Thomazella et al., 2021 |

| Multiple diseases | FL8000 | DMR6-1 | Solyc03g080190 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Disease resistance to P. syringae, P. capsici, and Xanthomonas spp. | Thomazella et al., 2016 |

| Fusarium wilt | 76R, rmc | - | Solyc08g075770 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Resistance | Prihatna et al., 2018 |

| Gray mold (Botrytis cinerea) |

Micro-Tom, Ailsa Craig | MYC2, MAPK3 | - | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Decreased disease resistance to B. cinerea | Zhang et al., 2018; Shu et al., 2020 |

| PVY, CMV | Inbred line S8 |

eIF4E1

(host gene) |

– | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | PVY and CMV resistant mutants | Atarashi et al., 2020 |

| Abiotic stress tolerance | |||||||

| Multiple stresses | Rubion | GRXS14/15/16/17 |

Solyc02g082200, Solyc06g067960, Solyc09g005620, Solyc02g078360 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Increased tolerance to heat, chilling, drought, heavy metal toxicity and nutrient deficiency | Kakeshpour et al., 2021 |

| Drought | Ailsa Craig | NPR1 | KX198701 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Reduced drought tolerance | Li et al., 2019 |

| Drought | Condine Red |

ALD1, FMO1 |

Solyc11g044840, Solyc07g04243 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Increased drought tolerance | Wang et al., 2021b |

| Drought | Micro-Tom | LBD40 | Solyc02g085910 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Increased drought tolerance | Liu et al., 2020a |

| Drought | Ailsa Craig | MAPK3 | AY261514 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Reduced drought tolerance | Wang et al., 2017 |

| Heat | Condine Red | BZR1 | Solyc04g079980 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Reduced heat tolerance | Yin et al., 2018 |

| Heat | Condine Red |

CPK28, APX2 |

Solyc02g083850, Solyc06g005150 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Improved thermotolerance | Hu et al., 2021 |

| Heat | MP-1 | AGL6 | Solyc01g093960 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Seedless fruit under heat stress | Klap et al., 2017 |

| Cold | Ailsa Craig | CBF1 | AAS77820 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Reduced chilling tolerance | Li et al., 2018e |

| Salinity | S. lycopersicum, S. pimpinellifolium | HAK20, SOS1 | Solyc04g008450, Solyc11g044540 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Increased salt sensitivity | Wang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021c |

| Salinity | Hongkwang |

HKT1;2

RAD51/54 |

Solyc07g017540, Solyc04g056400 |

Cas12a/ LbCpf1 (Geminivirus replicon) |

Agrobacterium | Increased salt tolerance | Vu et al., 2020b |

| Salinity | Hongkwang | HyPRP1 | Solyc12g009650 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Increased salt tolerance | Tran et al., 2021 |

| C-N metabolism | Micro-Tom | SBPase | Solyc05g052600 | Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Optimal growth, carbon assimilation and nitrogen metabolism | Ding et al., 2018 |

| Phosphate transporter | Micro-Tom |

PHO1;1, PHO1;2, PHO1;3, PHO1;4, PHO1;5, PHO1;6 |

Solyc09g090360

Solyc08g068240, Solyc05g010060, Solyc05g013180, Solyc02g088220, Solyc02g088230 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | High anthocyanin and phosphate content | Zhao et al., 2019 |

| Herbicide resistance | WVA106 | ALS | Solyc03g044330 | Cas9 (base editing) |

Agrobacterium | Resistance (Chlorsulfuron) | Veillet et al., 2019 |

| Herbicide resistance | Micro-Tom |

PDS, ALS, EPSPS |

Solyc03g123760, Solyc06g059880, Solyc03g044330, Solyc01g091190 |

Cas9 (knockout) | Agrobacterium | Resistance | Yang et al., 2022 |

| Herbicide resistance | – |

ALS1, ALS2, ALS3 |

Solyc03g044330, Solyc07g061940, Solyc06g059880 |

Cas9 (knockin) | Agrobacterium | Resistance (Chlorsulfuron) | Danilo et al., 2019 |

7-DR2 (7-Dehydrocholesterol reductase), AGL6 (Agamous-like 6), AGO7 (Argonaute7), ALC (Alcobaca), ALD1 (AGD2-like defense response protein), ALMT (Al-activated malate transporter),ALS1 (Acetolactate synthase 1), AMS (Aborted microspores), AN2 (Anthocyanin2), ANT1 (Anthocyanin 1), AP2a (Apetala2a TF), APX2/4 (Ascorbate peroxidase2/4), Blc (Beta-lycopene cyclase),BOPs (Blade-on-petiole), BZR1 (Brassinazole-resistant 1), CRTISO (Carotenoid isomerise), CAT9 (Cationic amino acid transporter 9), CBF1 (C-repeat/dehydration responsive element binding factor1), CLV3 (Clavata3), CMT4 (Chromomethylase), CNR (SBP-box colorless non-ripening), CPK28 (Calcium-dependent protein kinase28), CP (Coat protein), CrtR-b2 (Beta-carotene hydroxylase 2),CRTISO (Central role of carotenoid isomerase), CYC-B/CycB (Lycopene beta cyclase), DDB1 (DNA damage UV binding protein 1), DELLA (Aspartic acid–glutamic acid–leucine–leucine–alanine),DCL2b (Dicer-like 2b), DET1 (Deetiolated1), DMR6 (Downy mildew resistance 6), EJ2 (Enhancer-of-jointless2), ENO (Excessive number of floral organs), EPSPS (5-Enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase), ETR1 (Ethylene receptor 1), FASCIATED (FAS), FMO1 (Flavin-dependent monooxygenase), FUL1/2 (Fruitfull), GABA-TP1 (Pyruvate-dependent g-aminobutyric acidtransaminase 1), GAD2 (Glutamate decarboxylase 2), GAD3 (Glutamate decarboxylase 3), GF (Greenflesh/Staygreen), GGP1 (GDP-l-galactose phosphorylase1), GRXS (CGFS-type glutaredoxin),GSTAA (Glutathione S-transferase), HAK20 (High-affinity K+ 20), HKT1;2 (High-affinity potassium transporter 1;2), HY5 (elongated hypocotyl5), HyPRP1 (Hybrid proline-rich protein 1), IAA9(Auxin-induced 9), INVINH1 (Invertase inhibitor 1), J2 (Jointless-2), JAZ2 (Jasmonate zim domain), LBD40 (Lateral organ boundaries domain40), LOCULE NUMBER (LC), LCY-B1 (Lycopene bcyclase1), LCY-B2 (Lycopene b-cyclase 2), LCY-E (Lycopene e-cyclase), LIN (Long inflorescence), MAPK3 (Mitogen activated protein kinase 3), MIR164A (MicroRNA164A), TFAM1/TFAM2(Mitochondrial transcription factor A), Mlo1 (Mildew resistance locus o 1), MS10 (Male sterile 10), Ms1035 (Male sterile 1035), MULT (Multiflora), MYBS2 (MYB transcription factor S2), MYC2(Basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor), NAC (NAM-ATAF-CUC), NAM1/2/3 (No apical meristem1/2/3), NAC-NOR (NAC TF non-ripening), NOR (Non-ripening), NOR-like1 (Non-ripeninglike1), NPR1 (Nonexpressor of pathogenesis-related gene 1), O (ovate), ORRM4 (organelle RNA recognition motif-containing protein4), PDS (Phytoene desaturase), OFP (OVATE family protein),PG (Polygalacturonase), PG2a (polygalacturonase 2a), PHO1 (Phosphate 1), PIF4 (Phytochrome interacting factor 4), PL (pectate lyase), PMR4 (Powdery mildew resistance 4), PR-1 (Pathogenesisrelatedprotein-1), PRO (Procera), ProSys (Prosystemin), PSY1 (Phytoene synthase 1), RAD51/54 (DNA repair and recombination protein51/54), RBOH/RBOHE (Respiratory burst oxidasehomolog), RDR6 (RNA ald1dependent RNA polymerase 6), REP (Replicase), RIN (Ripening inhibitor), RMC (Reduced mycorrhizal colonization), SBPase (Sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase), S(Compound inflorescence), SCR (Scarecrow), SHR (Shortroot), SGR1 (Stay-green 1), SGS3 (Suppressor of gene silencing 3), SOS1 (Salt overly sensitive 1), SP (Self pruning), SP5G (Self pruning 5G),SSADH (Succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase), Target-AID (Target activation-induced cytidine deaminase), TBG4 (b-galactanase), TFM6 (Tomato fruit malate on chromosome6), TMF(Terminating flower), ToMV (Tomato Mosaic virus), TRM3/4/5 (TONNEAU1 Recruiting Motif3/4/5), VPE5 (Vacuolar processing enzyme5), and WUS (Wuschel).RNPs (ribonucleoproteins), PEG (polyethylene glycol), Target-AID (Target Activation Induced Cytidine Deaminase), NHEJ (Homologous-End-Joining), KO (gene knock-out), KI (gene knock-in), HDR (homology-directed repair), HR (homologous recombination), HKI (HR-based KI).

Figure 1.

Genome editing of key genes involved in trait modification in plant phenotype, fruit yield, quality, biotic and abiotic stress in tomato.

Plant architecture, flower, and fruit traits

CRISPR/Cas9 technology has been deployed successfully in tomato for plant architecture, flower and fruit traits ( Table 1 ). In the early domestication process, small-fruited cherry tomato led to the development of large-fruited modern tomato cultivars. During this process a number of traits were evolved and now it has been proven by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Cas9-based genome engineering has been applied in tomato for yield and its related traits such as a determinate plant growth habit caused by the flowering repressor SP (Self pruning) gene, a 3-fold increase in fruit size by the gene FAS (fasciated), an oval shape the ovate (O) gene, a 10-fold increase in fruit number by the gene MULT (multiflora), an increased fruit weight by the gene FW2.2 (fruit weight), and a very high lycopene content that has been improved by 500% (CYC-B/CycB). Moreover, many other traits have also been edited such as male sterility for hybrid seed production via co-knockouts of the Ms1035 (Male Sterile 1035), GSTAA (Glutathione S-Transferase) genes (Liu et al., 2021a), J2 (Jointless-2) gene for mechanical harvesting (Roldan et al., 2017), and pectin degradation in ripening tomato (Wang et al., 2019c).

The essential role of the RIN (ripening inhibitor) gene encoding the MADS-box transcription factor in fruit ripening is well known, as evidenced by various researchers ( Table 1 ). RIN gene-defective mutants yielded partially ripened fruits, whereas heterologous mutants yielded fully ripened red fruits, confirmed its role in fruit ripening in tomato (Ito et al., 2015; Ito et al., 2017; Ito et al., 2020). The roles of the genes SGR1 (Stay-Green1), LCY-E (Lycopene e-cyclase), Blc (Beta-lycopene someri), and LCY-B1/LCY-B2 (Lycopene b-cyclase 1/2) have been illustrated in the carotenoid metabolic pathways by using CRISPR/Cas9 gene knockout mechanism. Lycopene content in the mutants was increased by about 5.1-fold along with other advantages such as high efficiency, rare off-target mutations, and stable heredity (Li et al., 2018b). The CYC-B/CycB (Lycopene beta someri) gene-mediated Cas9 editing increased the lycopene content in tomato (Zsögön et al., 2018). Cas9-mediated editing of the AGL6 (Agamous-like 6) gene resulted in parthenocarpic fruit development under heat stress conditions in tomato (Klap et al., 2017). A large number of traits have been modified using CRISPR/Cas9 in tomato for fruit color (yellow, pink and purple). Increased GABA content (7–15 folds) in fruits was obtained by CRISPR/Cas9 editing of GAD2/3 (Glutamate Decarboxylase 2/3) genes (Nonaka et al., 2017). High total soluble solids (TSS) content is very important in tomato varieties for processing purposes. Recently, Wang et al. (2021a) regenerated CRISPR gene knockout mutants of INVINH1 and VPE5 genes with significantly increased levels of glucose, fructose, and TSS content.

Biotic and abiotic stress resistance/tolerance traits

Tomato is affected seriously by various biotic (disease and insect-pest) and abiotic (heat, drought, cold, salinity) stresses. To overcome these problems, in the recent years many traits have been edited by CRISPR/Cas9 tools ( Table 1 ). Importantly, tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TLCV) is the most devastating disease of tomato. CRISPR/Cas9 has been successfully deployed to develop TYLCV resistant plants. High resistance to TYLCV (Ty-5) and powdery mildew diseases were developed via Cas9 editing of the Pelo and Mlo1 genes (Pramanik et al., 2021). Further, multiple disease-resistant mutants have been regenerated via CRISPR/Cas9 editing of DMR6-1 (Downy mildew resistance 6-1) for P. syringae, P. capsici, and Xanthomonas spp. (Thomazella et al., 2016; Thomazella et al., 2021). They showed that mutants displaying up-regulation of DMR6-1 after pathogen infection has enhanced disease resistance, which was correlated with increased salicylic acid (SA) (Thomazella et al., 2016; Thomazella et al., 2021). Late blight (Phytophthora infestans) resistant mutants were also developed by CRISPR/Cas9 editing of the MYBS2 (MYB transcription factor S2) gene (Liu et al., 2021b).

Heat stress is one of the most serious issues in tomato cultivation in climate change scenarios. Several abiotic stresses related traits have been altered by CRISPR/cas9 ( Table 1 ). CRISPR/Cas9 editing of the CPK28 (Calcium-dependent protein kinase28) gene targeting APX2 (Ascorbate peroxidase 2) improved thermotolerance in tomato (Hu et al., 2021). CRISPR/Cas9 of GRXS14/15/16/17 (CGFS-type glutaredoxin 14/15/16/17) genes showed increased tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses such as heat, chilling, drought, heavy metal toxicity, and nutrient deficiency (Kakeshpour et al., 2021). Salinity stress tolerance was detected in Cas9 mutants of genes like HKT1;2 (High-affinity potassium transporter1;2), RAD51/54 (DNA repair and recombination protein 51/54) (Vu et al., 2020b), and PR-1 (Pathogenesis-related protein 1) (Tran et al., 2021). Taken together, a large number of traits have been modified in tomato applying CRISPR/Cas9 ( Table 1 ).

Concluding remarks

The CRISPR/Cas system is a powerful technology for next-generation breeding of tomato. An immense development has been observed in CRISPR/Cas research, such as protoplast-mediated sgRNAs/RNPs transformation, the PAM-free system, dCas9-mediated epigenome modification and targeted base/prime editing. However, many questions remain unanswered, like the missing link connecting interference, adaptation in primed spacer acquisition, and the mechanism behind the horizontal transfer of CRISPR/Cas. Still, several challenges are involved in CRISPR/Cas. First, the generation of off-targets is the major concern in genome editing, which can be reduced considerably using the Cas9 variant (Cas12a) with diverse PAM sequence specificities and base or prime editing. Second, off-target mutants are reduced by increasing the specificity of Cas9 cleavage via the induction of double nickage mutants or truncation of the gRNA. It is also important to reduce the problems caused by the low frequency of HDR in plants. Third, multiplex editing is an efficient strategy for the simultaneous dissection of multiple genes, proteins, and metabolites at specific precision. Fourth, problems are associated with the selection of a large number of bases, which is possible with HKI. Fifth, dealing with in-planta transformation issues in Agrobacterium-mediated (Maher et al., 2020) or nanoparticle-mediated (Cunningham et al., 2018) transformation, and so on. Altogether, an appropriate sgRNA, Cas array, efficient transformation system, and phenotype without off-targets are the key considerations of CRISPR/Cas9.

Innovations in Cas9 offer precise editing of targeted genes and even simultaneous editing of multiple genes by multiplexing to accelerate breeding at reduced costs. Diversity in CRISPR/Cas toolbox is required to mediate the catalytic activities of CRISPR/Cas along with environmentally friendly protocols for efficient delivery of Cas9. New CRISPR/Cas tools have created more efficient and precise editing via base editing, prime editing, and HKI. Allele introgression via targeted mutagenesis, as well as base editing and HKI in tomato, has become easier and less time-consuming. The discovery of programmable Cas9 variant and Cas12a nucleases has widened more scope without any off-targets. The use of a multiplexing approach with a robust CRISPR/Cas9 array having single or multiple sgRNAs or RNPs targeting conserved sequences of target genes and protoplast-mediated transformation could be deployed for precision editing. Homozygous edited lines can be obtained through haploid-inducer-based genome editing. Cas9 components can be removed via genetic segregation, and transgene-free genome-edited mutants can be obtained to meet regulatory requirements. More importantly, public awareness is necessary for the popularity of genome-edited plants, which do not contain any foreign genes. Hence, the regulatory process needs to be harmonized in public for genome-edited mutants. There is no concern about biosafety regulation in genome-edited plants because they are free of foreign genes, particularly site-directed nucleases (SDN1 and SDN2), and the vector backbone is removed through genetic segregation via backcrossing. The United States Department of Agriculture provides an exemption for these genome-edited crops, e.g., mushroom and corn; on the contrary, the Court of Justice of the European Union considered genome-edited plants under the same transgenic category. Further, the USA has released six virus-resistant genome-edited tomatoes. Genome-edited plants could be accepted as transgene-free (non-GM) by the public and regulatory bodies, which would open more avenues for the application of CRISPR/Cas in tomatoes. Taken together, there is a tremendous potential to deploy CRISPR/Cas9 for trait modifications in tomato.

Author contributions

JT: conceptualized and wrote the manuscript; AS and TB critically edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank ICAR-IIVR, Varanasi for the necessary support under institute research project and ICAR-CRP on Hybrid Technology (Tomato) (Project code: 3024). Thanks to the ICAR-Lal Bahadur Shastri Outstanding Young Scientist Award project to JT.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Alonge M., Wang X., Benoit M., Soyk S., Pereira L., Zhang L, et al. (2020). Major impacts of widespread structural variation on gene expression and crop improvement in tomato. Cell 182, 145–161.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atarashi H., Jayasinghe W. H., Kwon J., Kim H., Taninaka Y., Igarashi M., et al. (2020). Artificially edited alleles of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E1 gene differentially reduce susceptibility to cucumber mosaic virus and potato virus y in tomato. Front. Microbiol. 11, 564310. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.564310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao H., Ding Y., Yang F., Zhang J., Xie J., Zhao C., et al. (2022). Gene silencing, knockout and over-expression of a transcription factor ABORTED MICROSPORES (SlAMS) strongly affects pollen viability in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). BMC Genom. 23 (Suppl 1), 346. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08549-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks C., Nekrasov V., Lipppman Z. B., Van Eck J. (2014). Efficient gene editing in tomato in the first generation using the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated9 system. Plant Physiol. 166, 1292–1297. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.247577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler N. M., Baltes N. J., Voytas D. F., Douches D. S. (2016). Geminivirus-mediated genome editing in potato (Solanum tuberosum l) using sequence-specific nucleases. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1045. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cˇermák T., Baltes N. J., Cˇegan R., Zhang Y., Voytas D. F. (2015). High-frequency precise modificat. tomato genome. Genome Biol. 16, 232. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0796-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Causse M., Giovannoni J., Bouzayen M., Zouine M. (2016). The Tomato Genome. Springer Berlin, Heidelberg. p. 259. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-53389-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran M., Boopathi T., Paramasivan M. (2021). A status-quo review on CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing applications in tomato. Inter J. Biol. Macromol. 190, 120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.08.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri A., Halder K., Datta A. (2022). Classification of CRISPR/Cas system and its application in tomato breeding. Theor. Appl. Genet. 135 (2), 367–387. doi: 10.1007/s00122-021-03984-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham F. J., Goh N. S., Demirer G. S., Matos J. L., Landry M. P. (2018). Nanoparticle-mediated delivery towards advancing plant genetic engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 36 (9), 882–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan-Meir T., Filler-Hayut S., Melamed-Bessudo C., Bocobza S., Czosnek H., Aharoni A., et al. (2018). Efficient in planta gene targeting in tomato using geminiviral replicons and the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant J. 95 (1), 5–16. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X., Han H., Huang W., Zhao L., Song M., Cao X., et al. (2022). Generating novel male sterile tomatoes by editing respiratory burst oxidase homolog genes. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 817101. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.817101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio C., Stigliani A. L., Giorio G. (2018). CRISPR/Cas9 editing of carotenoid genes in tomato. Transgenic Res. 27 (4), 367–378. doi: 10.1007/s11248-018-0079-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilo B., Perrot L., Mara K., Botton E., Nogue F., Mazier M. (2019). Efficient and transgene-free gene targeting using Agrobacterium-mediated delivery of the CRISPR/Cas9 system in tomato. Plant Cell Rep. 38, 459–462. doi: 10.1007/s00299-019-02373-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L., Wang H., Sun C., Li Q., Jiang H., Du M., et al. (2018). Efficient generation of pink-fruited tomatoes using CRISPR/Cas9 system. J. Genet. Genomics 45, 51–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding F., Hu Q., Wang M., Zhang S. (2018). Knockout of SlSBPASE suppresses carbon assimilation and alters nitrogen metabolism in tomato plants. Inter J. Mol. Sci. 19 (12), 4046. doi: 10.3390/ijms19124046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do J. H., Park S. Y., Park S. H., Kim H. M., Ma S. H., Mai T. D., et al. (2022). Development of a genome-edited tomato with high ascorbate content during later stage of fruit ripening through mutation of SlAPX4. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 836916. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.836916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler C., Youles M., Gruetzner R., Ehnert T.M., Werner S., Jones J. D., et al. (2014). A golden gate modular cloning toolbox for plants. ACS Synth Biol. 3 (11), 839–843. doi: 10.1021/sb4001504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faal P. G., Farsi M., Seifi A., Mirshamsi Kakhki A. (2020). Virus-induced CRISPR-Cas9 system improved resistance against tomato yellow leaf curl virus. Mol. Biol. Rep. 47 (5), 3369–3376. doi: 10.1007/s11033-020-05409-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2022) World Population Prospects 2022: The 2017 Revision Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT (2022). Available at: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL.

- Gao Y., Fan Z. Q., Zhang Q., et al. (2021). A tomato NAC transcription factor, SlNAM1, positively regulates ethylene biosynthesis and the onset of tomato fruit ripening. Plant J. 108 (5), 1317–1331. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Zhu N., Zhu X. F., Wu M., Jiang C. Z., Grierson D., et al. (2019). Diversity and redundancy of the ripening regulatory networks revealed by the fruit ENCODE and the new CRISPR/Cas9 CNR and NOR mutants. Hortic. Res. 6, 39. doi: 10.1038/s41438-019-0122-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianoglio S., Comino C., Moglia A., Acquadro A., García-Carpintero V., Diretto G., et al. (2022). In-depth characterization of greenflesh tomato mutants obtained by CRISPR/Cas9 editing: A case study with implications for breeding and regulation. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 936089. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.936089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Zhao J., Chen Z., Qiao J., Zhang Y., Shen H., et al. (2022). CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of SlCMT4 causes changes in plant architecture and reproductive organs in tomato. Hortic. Res. 9, uhac081. doi: 10.1093/hr/uhac081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanak T., Madsen C. K., Brinch-Pedersen H. (2022). Genome editing-accelerated re-domestication (GEaReD) - a new major direction in plant breeding. Biotechnol. J. 17 (7), e2100545. doi: 10.1002/biot.202100545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayut S. F., Bessudo C. M., Levy A. A. (2017). Targeted recombination between homologous chromosomes for precise breeding in tomato. Nat. Commun. 8, 15605. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Li J., Ding S. (2021). The protein kinase CPK28 phosphorylates ascorbate peroxidase and enhances thermotolerance in tomato. Plant Physiol. 186 (2), 1302–1317. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiab120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu N., Xian Z., Li N., Liu Y., Huang W., Yan F., et al. (2019). Rapid and user-friendly open-source CRISPR/Cas9 system for single- or multi-site editing of tomato genome. Hortic. Res. 6, 7. doi: 10.1038/s41438-018-0082-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunziker J., Nishida K., Kondo A., Kishimoto S., Ariizumi T., Ezura H. (2020). Multiple gene substitution by target-AID base-editing technology in tomato. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77379-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y., Nishizawa-Yokoi A., Endo M., Mikami M., Toki S. (2015). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of the RIN locus that regulates tomato fruit ripening. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 467 (1), 76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.09.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y., Nishizawa-Yokoi A., Endo M., Mikami M., Shima Y., Nakamura N., et al. (2017). Re-evaluation of the rin mutation and the role of RIN in the induction of tomato ripening. Nat. Plants 3, 866–874. doi: 10.1038/s41477-017-0041-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y., Sekiyama Y., Nakayama H., Nishizawa-Yokoi A., Endo M., Shima Y., et al. (2020). Allelic mutations in the ripening-inhibitor locus generate extensive variation in tomato ripening. Plant Physiol. 183, 80–95. doi: 10.1104/pp.20.00020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraj K. L., Thulasidharan N., Antony A., John M., Augustine R., Chakravartty N., et al. (2021). Targeted editing of tomato carotenoid isomerase reveals the role of 5’ UTR region in gene expression regulation. Plant Cell Rep. 40 (4), 621–635. doi: 10.1007/s00299-020-02659-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y. J., Kim D. H., Lee H. J., Nam K. H., Bae S., Nou I. S., et al. (2020). Knockout of SlMS10 gene (Solyc02g079810) encoding bHLH transcription factor using CRISPR/Cas9 system confers male sterility phenotype in tomato. Plants (Basel) 9 (9), 1189. doi: 10.3390/plants9091189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakeshpour T., Tamang T. M., Motolai G., Fleming Z. W., Park J. E., Wu Q., et al. (2021). CGFS-type glutaredoxin mutations reduce tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in tomato. Physiol. Plant 173 (3), 1263–1279. doi: 10.1111/ppl.13522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi K., Takei-Hoshi R., Yoshikawa I., Nishida K., Kobayashi M., Kusano M., et al. (2021). Functional disruption of cell wall invertase inhibitor by genome editing increases sugar content of tomato fruit without decrease fruit weight. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 21534. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00966-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klap C., Yeshayahou E., Bolger A. M., Arazi T., Gupta S. K., Shabtai S., et al. (2017). Tomato facultative parthenocarpy results from SlAGAMOUS-LIKE 6 loss of function. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 634–647. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Feng Q., Snouffer A., Zhang B., Rodríguez G. R., van der Knaap E. (2022. b). Increasing fruit weight by editing a cis-regulatory element in tomato KLUH promoter using CRISPR/Cas9. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 879642. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.879642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Fu D., Zhu B., Luo Y., Zhu H. (2018. a). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of lncRNA1459 alters tomato fruit ripening. Plant J. 94 (3), 513–524. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Li R., Li X., Fu D., Zhu B., Tian H., et al. (2018. c). Multiplexed CRISPR/Cas9-mediated metabolic engineering of y-aminobutyric acid levels in Solanum lycopersicum . Plant Biotechnol. J. 16, 415–427. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Liu C., Zhao R., Wang L., Chen L., Yu W., et al. (2019). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated SlNPR1 mutagenesis reduces tomato plant drought tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 19, 38. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1627-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Scarano A., Gonzalez N. M., D’Orso F., Yue Y., Nemeth K., et al. (2022. a). Biofortified tomatoes provide a new route to vitamin d sufficiency. . Nat. Plants 8 (6), 611–616. doi: 10.1038/s41477-022-01154-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Wang Y., Chen S., Tian H., Fu D., Zhu B., et al. (2018. b). Lycopene is enriched in tomato fruit by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated multiplex genome editing. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 559. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Yang X., Yu Y., Si X., Zhai X., Zhang H., et al. (2018. d). Domestication of wild tomato is accelerated by genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 1160–1163. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Zhang L., Wang L., Chen L., Zhao R., Sheng J., et al. (2018. e). Reduction of tomato-plant chilling tolerance by CRISPR–Cas9-mediated SlCBF1 mutagenesis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 9042–9051. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. S., Hsu C. T., Yuan Y. H., Zheng P. X., Wu F. H., Cheng Q. W., et al. (2022. a). DNA-Free CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing of wild tetraploid tomato solanum peruvianum using protoplast regeneration. Plant Physiol. 188 (4), 1917–1930. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiac022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D., Zhu X., Qi B., Gao Z., Tian P., Li Z., et al. (2022. b). SlMIR164A regulates fruit ripening and quality by controlling SlNAM2 and SlNAM3 in tomato. Plant Biotechnol. J. 20 (8), 1456–1469. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Andersson M., Granell A., Cardi T., Hofvander P., Nicolia A. (2022). Establishment of a DNA-free genome editing and protoplast regeneration method in cultivated tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Plant Cell Rep. 41 (9), 1843–1852. doi: 10.1007/s00299-022-02893-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Rudis M. R., Cheplick M. H., Millwood R. J., Yang J. P., Ondzighi-Assoume C. A., et al. (2020. b). Lipofection-mediated genome editing using DNA-free delivery of the Cas9/gRNA ribonucleoprotein into plant cells. Plant Cell Rep. 39, 245–257. doi: 10.1007/s00299-019-02488-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Wang S., Wang H., Luo B., Cai Y., Li X., et al. (2021. a). Rapid generation of tomato male-sterile lines with a marker use for hybrid seed production by CRISPR/Cas9 system. Mol. Breed 41, 25. doi: 10.1007/s11032-021-01215-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Zhang Y., Tan Y., Zhao T., Xu X., Yang H., et al. (2021. b). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated SlMYBS2 mutagenesis reduces tomato resistance to phytophthora infestans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (21), 11423. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Zhang J., Xu J., Li Y., Guo L., Wang Z., et al. (2020. a). CRISPR/Cas9 targeted mutagenesis of SlLBD40, a lateral organ boundaries domain transcription factor, enhances drought tolerance in tomato. Plant Sci. 301, 110683. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Tian Y., Shen R., Yao Q., Zhong D., Zhang X., et al. (2021). Precise genome modification in tomato using an improved prime editing system. Plant Biotechnol. J. 19 (3), 415–417. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher M. F., Nasti R. A., Vollbrecht M., Starker C. G., Clark M. D., Voytas D. F. (2020). Plant gene editing through de novo induction of meristems. Nat. Biotechnol. 38 (1), 84–89. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0337-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez M. I. S., Bracuto V., Koseoglou E., Appiano M., Jacobsen E., Visser R., et al. (2020). CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of the tomato susceptibility gene PMR4 for resistance against powdery mildew. BMC Plant Biol. 20 (1), 284. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02497-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekrasov V., Wang C., Win J., Lanz C., Weigel D., Kamoun S. (2017). Rapid generation of a transgene-free powdery mildew resistant tomato by genome deletion. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 482. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00578-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie H., Shi Y., Geng X., Xing G. (2022). CRISRP/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis of tomato polygalacturonase gene (SlPG) delays fruit softening. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 729128. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.729128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Q., Wu S., Li Y., Yang X., Liu P., Xu Y., et al. (2020). Expanding the scope of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in plants using an xCas9 and Cas9-NG hybrid. J. Integ Plant Biol. 62 (4), 398–402. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka S., Arai C., Takayama M., Matsukura C., Ezura H. (2017). Efficient increase of ɣ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) content in tomato fruits by targeted mutagenesis. Sci. Rep. 7, 7057. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06400-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortigosa A., Gimenez-Ibanez S., Leonhardt N., Solano R. (2019). Design of a bacterial speck resistant tomato by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of SlJAZ2. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 665–673. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan C., Wu X., Markel K., Malzahn A. A., Kundagrami N., Sretenovic S., et al. (2021). CRISPR-Act3.0 for highly efficient multiplexed gene activation in plants. Nat. Plants 7 (7), 942–953. doi: 10.1038/s41477-021-00953-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan C., Ye L., Qin L., Liu X., He Y., Wang J., et al. (2016). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated efficient and heritable targeted mutagenesis in tomato plants in the first and later generations. Sci. Rep. 6, 24765. doi: 10.1038/srep24765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik D., Shelake R. M., Park J., Kim M. J., Hwang I., Park Y., et al. (2021). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated generation of pathogen-resistant tomato against tomato yellow leaf curl virus and powdery mildew. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (4), 1878. doi: 10.3390/ijms22041878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prihatna C., Barbetti M. J., Barker S. J. (2018). A novel tomato fusarium wilt tolerance gene. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1226. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z., Wang H., Li D., Yu B., Hui Q., Yan S., et al. (2019). Identification of candidate HY5-dependent and -independent regulators of anthocyanin biosynthesis in tomato. Plant Cell Physiol. 60, 643–656. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Leal D., Lemmon Z. H., Man J., Bartlett M. E., Lippman Z. B. (2017). Engineering quantitative trait variation for crop improvement by genome editing. Cell 171, 470–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roldan M. V. G., Perilleux C., Morin H., Huerga-Fernandez S., Latrasse D., Benhamed M., et al. (2017). Natural and induced loss of function mutations in SlMBP21 MADS-box gene led to jointless-2 phenotype in tomato. Sci. Rep. 7, 4402. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04556-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron M., Kajala K., Pauluzzi G., Wang D., Reynoso M. A., Zumstein K., et al. (2014). Hairy root transformation using Agrobacterium rhizogenes as a tool for exploring cell type-specific gene expression and function using tomato as a model. Plant Physiol. 166 (2), 455–469. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.239392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothan C., Diouf I., Causse M. (2019). Trait discovery and editing in tomato. Plant J. 97 (1), 73–90. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salava H., Thula S., Mohan V., Kumar R., Maghuly F. (2021). Application of genome editing in tomato breeding: Mechanisms, advances, and prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (2), 682. doi: 10.3390/ijms22020682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimatani Z., Kashojiya S., Takayama M., Terada R., Arazoe T., Ishii H., et al. (2017). Targeted base editing in rice and tomato using a CRISPR-Cas9 cytidine deaminase fusion. Nat. Biotechnol. 35 (5), 441–443. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu P., Li Z., Min D., Zhang X., Ai W., Li J., et al. (2020). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated SlMYC2 mutagenesis adverse to tomato plant growth and meja-induced fruit resistance to botrytis cinerea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 5529–5538. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b08069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyk S., Müller N. A., Park S. J., Schmalenbach I., Jiang K., Hayama R., et al. (2017). Variation in the flowering gene SELF PRUNING 5G promotes day-neutrality and early yield in tomato. Nat. Genet. 49, 162–168. doi: 10.1038/ng.3733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sretenovic S., Liu S., Li G., Cheng Y., Fan T., Xu Y., et al. (2021). Exploring c-To-G base editing in rice, tomato, and poplar. Front. Genome Edit. 3, 756766. doi: 10.3389/fgeed.2021.756766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashkandi M., Ali Z., Aljedaani F., Shami A., Mahfouz M. M. (2018). Engineering resistance against tomato yellow leaf curl virus via the CRISPR/Cas9 system in tomato. Plant Signal Behav. 13, e1525996. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2018.1525996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiruppathi D. (2022). CRISPR keeps going “wild”: a new protocol for DNA-free genome editing of tetraploid wild tomatoes. Plant Physiol. 189 (1), 10–11. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiac061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomazella D., Brail Q., Dahlbeck D., Staskawicz B. (2016). CRISPR-Cas9 mediated mutagenesis of a DMR6 ortholog in tomato confers broad-spectrum disease resistance. BioRxiv 064824. doi: 10.1101/064824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomazella D., Seong K., Mackelprang R., Dahlbeck D., Geng Y., Gill U. S., et al. (2021). Loss of function of a DMR6 ortholog in tomato confers broad-spectrum disease resistance. Procd Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118 (27), e2026152118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2026152118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikunov Y. M., Roohanitaziani R., Meijer-Dekens F., Molthoff J., Paulo J., Finkers R., et al. (2020). The genetic and functional analysis of flavor in commercial tomato: The FLORAL4 gene underlies a QTL for floral aroma volatiles in tomato fruit. Plant J. 103, 1189–1204. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari J. K., Yerasu S. R., Rai N., Singh D. P., Singh A. K., Karkute S. G., et al. (2022). Progress in marker-assisted selection to genomics-assisted breeding in tomato. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 41 (5), 321–50. doi: 10.1080/07352689.2022.2130361 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomato Genome Consortium (2012). The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature 485, 635–641. doi: 10.1038/nature11119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson L., Yang Y., Emenecker R., Smoker M., Taylor J., Perkins S., et al. (2019). Using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in tomato to create a gibberellin-responsive dominant dwarf DELLA allele. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17 (1), 132–140. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran M. T., Doan D. T. H., Kim J., Song Y. J., Sung Y. W., Das S., et al. (2021). CRISPR/Cas9-based precise excision of SlHyPRP1 domain(s) to obtain salt stress-tolerant tomato. Plant Cell Rep. 40, 999–1011. doi: 10.1007/s00299-020-02622-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueta R., Abe C., Watanabe T., Sugano S. S., Ishihara R., Ezura H., et al. (2017). Rapid breeding of parthenocarpic tomato plants using CRISPR/Cas9. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 507. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00501-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Vilar M., García-Carpintero V., Selma S., Bernabé-Orts J. M., Sánchez-Vicente J., Salazar-Sarasua B., et al. (2021). The GB4.0 platform, an all-in-one tool for CRISPR/Cas-based multiplex genome engineering in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 689937. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.689937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veillet F., Perrot L., Chauvin L., Kermarrec M. P., Guyon-Debast A., Chauvin J. E., et al. (2019). Transgene-free genome editing in tomato and potato plants using Agrobacterium-mediated delivery of a CRISPR/Cas9 cytidine base editor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (2), 402. doi: 10.3390/ijms20020402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu T. V., Das S., Tran M. T., Hong J. C., Kim J. Y. (2020. a). Precision genome engineering for the breeding of tomatoes: Recent progress and future perspectives. Front. Genome Ed. 2, 612137. doi: 10.3389/fgeed.2020.612137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu T. V., Doan D., Tran M. T., Sung Y. W., Song Y. J., Kim J. Y. (2021). Improvement of the LbCas12a-crRNA system for efficient gene targeting in tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 722552. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.722552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu T. V., Sivankalyani V., Kim E. J., Doan D., Tran M. T., Kim J. (2020. b). Highly efficient homology-directed repair using CRISPR/Cpf1-geminiviral replicon in tomato. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18 (10), 2133–2143. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada N., Osakabe K., Osakabe Y. (2022). Expanding the plant genome editing toolbox with recently developed CRISPR-cas systems. Plant Physiol. 188 (4), 1825–1837. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiac027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz E. (2022). GABA-enriched tomato is first CRISPR-edited food to enter market. Nat. Biotechnol. 40 (1), 9–11. doi: 10.1038/d41587-021-00026-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Chen L., Li R., Zhao R., Yang M., Sheng J., et al. (2017). Reduced drought tolerance by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated SlMAPK3 mutagenesis in tomato plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 65, 8674–8682. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Deng Z., Zhang X., Wang H., Wang Y., Liu X., et al. (2018). Tomato DCL2b is required for the biosynthesis of 22-nt small RNAs, the resulting secondary siRNAs, and the host defense against ToMV. Hortic. Res. 5, 62. doi: 10.1038/s41438-018-0073-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Hong Y., Li Y., Shi H., Yao J., Liu X., et al. (2021. c). Natural variations in SlSOS1 contribute to the loss of salt tolerance during tomato domestication. Plant Biotechnol. J. 19 (1), 20–22. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Hong Y., Zhu G., Li Y., Niu Q., Yao J., et al. (2020). Loss of salt tolerance during tomato domestication conferred by variation in a Na(+)/K(+) transporter. EMBO J. 39, e103256. doi: 10.15252/embj.2019103256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Li N., Huang S., Hu J., Wang Q., Tang Y., et al. (2021. a). Enhanced soluble sugar content in tomato fruit using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated SlINVINH1 and SlVPE5 gene editing. Peer J. 9, e12478. doi: 10.7717/peerj.12478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Luo Q., Yang W., Ahammed G. J., Ding S., Chen X., et al. (2021. b). A novel role of pipecolic acid biosynthetic pathway in drought tolerance through the antioxidant system in tomato. Antioxidants (Basel) 10 (12), 1923. doi: 10.3390/antiox10121923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Samsulrizal N. H., Yan C., Allcock N. S., Craigon J., Blanco-Ulate B., et al. (2019. c). Characterization of CRISPR mutants targeting genes modulating pectin degradation in ripening tomato. Plant Physiol. 179 (2), 544–557. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.01187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Tavano E., Lammers M., Martinelli A. P., Angenent G. C., de Maagd R. A. (2019. a). Re-evaluation of transcription factor function in tomato fruit development and ripening with CRISPR/Cas9-mutagenesis. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 1696. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-38170-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber E., Engler C., Gruetzner R., Werner Marillonnet S. S. (2011). A modular cloning system for standardized assembly of multigene constructs. PloS One 6, e16765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., He Y., Sretenovic S., Liu S., Cheng Y., Han Y., et al. (2022). CRISPR-BETS: A base-editing design tool for generating stop codons. Plant Biotechnol. J. 20 (3), 499–510. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S., Zhang B., Keyhaninejad N., Liu S., Cheng Y., Han Y., et al. (2018). A common genetic mechanism underlies morphological diversity in fruits and other plant organs. Nat. Commun. 9, 4734. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07216-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X., Cheng X., Li R., Yao J., Li Z., Cheng Y. (2021). Advances in application of genome editing in tomato and recent development of genome editing technology. Theor. Appl. Genet. 134 (9), 2727–2747. doi: 10.1007/s00122-021-03874-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C., Park S. J., van Eck J., Lippman Z. B. (2016). Control of inflorescence architecture in tomato by BTB/POZ transcriptional regulators. Genes Dev. 30, 2048–2061. doi: 10.1101/gad.288415.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S., Chen N., Huang Z., Li D., Zhi J., Yu B. (2020). Anthocyanin fruit encodes an R2R3-MYB transcription factor, SlAN2-like, activating the transcription of SlMYBATV to fine-tune anthocyanin content in tomato fruit. New Phytol. 225, 2048–2063. doi: 10.1111/nph.16272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S. H., Kim E., Park H., Koo Y. (2022). Selection of the high efficient sgRNA for CRISPR/Cas9 to edit herbicide related genes, PDS, ALS, and EPSPS in tomato. Appl. Biol. Chem. 65, 13. doi: 10.1186/s13765-022-00679-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Zhu G., Li R., Yan S., Fu D., Zhu B., et al. (2017). The RNA editing factor SlORRM4 is required for normal fruit ripening in tomato. Plant Physiol. 175 (4), 1690–1702. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J., Wang X., Hu T., Zhang F., Wang B., Li C., et al. (2017). An InDel in the promoter of Al-ACTIVATED MALATE TRANSPORTER9 selected during tomato domestication determines fruit malate contents and aluminium tolerance. Plant Cell 29, 2249–2268. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]