Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the presence of chronic critical illness (CCI) in COVID-19 patients and compare clinical characteristics and prognosis of patients with and without CCI admitted to intensive care unit (ICU).

Methods

It was a retrospective, observational study at a university hospital ICU. Patients were accepted as CCI if they had prolonged ICU stay (≥14 days) and got ≥1 score for cardiovascular sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score and ≥2 score in other parameters on day 14 of ICU admission which was described as persistent organ dysfunction.

Results

131 of 397 (33%) patients met CCI criteria. CCI patients were older (p = 0.003) and frailer (p < 0.001). Their Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II and SOFA scores were higher, PaO2/FiO2 ratio was lower (p < 0.001). Requirement of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), steroid use, and septic shock on admission were higher in the CCI group (p < 0.001). CCI patients had higher ICU and hospital mortality than other patients (54.2% vs. 19.9% and 55.7% vs. 22.6%, p < 0.001, respectively). Regression analysis revealed that IMV (OR: 8.40, [5.10–13.83], p < 0.001) and PaO2/FiO2 < 150 on admission (OR: 2.25, [1.36–3.71], p = 0.002) were independent predictors for CCI.

Discussion

One-third of the COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU were considered as CCI with significantly higher ICU and hospital mortality.

Keywords: Coronavirus, mortality, post-intensive care syndrome, SARS-CoV-2, outcome

Introduction

Patients with acute critical illness followed up in the intensive care unit (ICU) can be managed well regardless of the underlying cause thanks to the progress of intensive care medicine and contemporary medical practices, and mortality is decreasing in intensive care units, especially in developed countries.1,2 These patients encounter chronic conditions that require multi-organ support, especially with mechanical ventilation (MV). This process is called chronic critical illness (CCI) and it has become a serious healthcare system burden.3 Many disorders such as immunosuppression, resistant infections, malnutrition, neuropathy, myopathy, hematological dysfunction, delirium, cognitive dysfunction, and depression may accompany in these patients.4 Although the term of CCI was initially proclaimed in 1985,5 there is no generally accepted definition in the medical literature yet. Therefore, the exact epidemiology of CCI is not completely known. In 2017, Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center investigators from the University of Florida, the United States of America (USA) proposed a CCI definition. Patients were confirmed as CCI if they had prolonged ICU length-of-stay (LOS) (≥14 days) and got ≥1 score for cardiovascular sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score and ≥2 score in other parameters on day 14 of ICU admission which was described as persistent organ dysfunction.6

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has a heterogeneous clinical spectrum. COVID-19 may affect all organ systems and 5–32% of patients may require intensive care admission.7 The burden of COVID-19 and its correlation to other diseases are the hot topic study areas nowadays.8 There are only a few papers in terms of CCI and COVID-19 and there is still a lack of information regarding CCI status that may occur in patients requiring ICU admission due to COVID-19 that has been shown to have prolonged physical, cognitive, and psychological effects which were defined as post-acute COVID or long-COVID.9

In this study, our primary aim was to determine the prevalence of CCI in COVID-19 patients followed in ICU. Our secondary aim was to evaluate the clinical findings and prognosis of patients who were evaluated as CCI and to compare them with others.

Material and methods

Study design and patients

This study is a retrospective observational study on adult critically ill COVID-19 patients confirmed by polymerase chain reaction test admitted to our 28 beds ICU between 20th March 2020 and 15th June 2021. The study was approved by the University Faculty of Medicine Non-interventional Clinical Researches Ethics Committee (reference number: GO 22/277, date: 15.03.2022). This report does not contain any personal information related to the patients. Written informed consent did not need to be obtained from the patients due to the retrospective study design.

Data collection

Patient charts and electronic medical records were reviewed for data collection in terms of demographic data and comorbidities. The performance status of patients was evaluated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) and Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS). Disease severity was assessed by Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score. Organ dysfunction was determined by SOFA score on admission and 14th day in the CCI group. The partial pressure of arterial oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen ratios (PaO2/FiO2) on ICU admission was calculated for benchmarking of respiratory failure. Application of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) during the ICU stay was noted. Applied respiratory and rescue therapies for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and medications such as anti-viral drugs, and immunomodulatory therapies were also recorded.

Definitions and outcomes

Patients were defined as CCI if they had ICU LOS ≥ 14 days and got ≥1 score for cardiovascular SOFA score and ≥2 score in other parameters on day 14. This SOFA criterion was described as persistent organ dysfunction.6 Patients were dichotomized as CCI or others. Septic shock and acute kidney injury (AKI) were diagnosed based on Sepsis-3 definitions10 and Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes criteria11 on admission. Patients were considered as secondary bacterial infection if they had positive culture results with clinical symptoms and signs of infection 72 hours after ICU admission.12 The determination of Pneumocystis jiroveci, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Aspergillus species, and the presence of candidemia were accepted as opportunistic infections. Outcome was measured primarily as ICU mortality.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were indicated as median and interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles—IQR). Categorical variables were shown as frequency and percent. Mann–Whitney U test and Chi-square test were performed for the purpose of comparison of independent groups. Dependent variables were compared by the Wilcoxon test. Receiver-operator characteristics (ROC) analyses were done for the analysis of predictive factors for CCI. Median values were used for the categorization of numeric variables. Independent predictors of CCI were determined by binary logistic regression analysis with the Backward LR method. The effect of CCI on ICU survival was measured by Kaplan–Meier curve with log-rank. Statistical significance was confirmed when p-value is under 5%. All analysis was studied with SPSS 18 IBM® statistics program.

Results

Three hundred and ninety-seven confirmed COVID-19 patients were admitted to ICU during the study period. Among them, CCI criteria were obtained in 131 (33%) patients. General characteristics and outcomes of patients with CCI and others are seen in Table 1. The median age of the patients with CCI was 68 (60–78) and they were older than others whose median age was 63 (53–74) (p = 0.003). Median ECOG (p = 0.001), CFS (p < 0.001), APACHE II (p < 0.001), and admission SOFA (p < 0.001) scores were higher in patients with CCI than others. Admission laboratory values were similar except lymphocyte (0.60 vs. 0.75, p < 0.001) and platelet counts (183 vs. 196, p < 0.001) which were lower and procalcitonin levels which were higher (0.30 vs. 0.20, p = 0.003) in CCI patients (Appendix). Median PaO2/FiO2 ratio on admission was lower (129 vs. 171, p < 0.001), IMV (75.6% vs. 23.7%, p < 0.001), and tracheostomy (13.7% vs. 1.1%, p < 0.001) requirements were higher, IMV duration was longer (18 vs. 5 days, p < 0.001) in CCI patients than others. Septic shock on admission, secondary bacterial infection, and opportunistic infection (p < 0.001) were more common in patients with CCI. AKI on admission (p = 0.004) and requirement of RRT (p < 0.001) were seen more in CCI patients. Twenty-eighth day, ICU and hospital mortality rates (34.4% vs. 19.2%; p = 0.001, 54.2% vs. 19.9%; p < 0.001, 55.7% vs. 22.6%; p < 0.001) were higher and ICU (24 vs. 7 days, p < 0.001) and hospital LOS (31 vs. 14 days, p < 0.001) were longer in patients with CCI than others.

Table 1.

General characteristics of patients with chronic critical illness and others.

| Variables | All patients (n = 397) | CCI (n = 131) | No CCI (n = 266) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yearsa | 65 [55–76] | 68 [60–78] | 63 [53–74] | 0.003 |

| Age > 65 years old, n (%) | 207 (52.1) | 80 (61.1) | 127 (47.7) | 0.012 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 254 (64.0) | 82 (62.6) | 172 (64.7) | 0.687 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 209 (52.6) | 76 (58.0) | 133 (50.0) | 0.133 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 136 (34.3) | 48 (36.6) | 88 (33.1) | 0.482 |

| Cardiac disease | 134 (33.8) | 49 (37.4) | 85 (32.0) | 0.280 |

| Malignancy | 77 (19.4) | 28 (21.4) | 49 (18.4) | 0.484 |

| Chronic lung disease | 66 (16.6) | 26 (19.8) | 40 (15.0) | 0.226 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 35 (8.8) | 15 (11.5) | 20 (7.5) | 0.194 |

| Chronic liver disease | 11 (2.8) | 3 (2.3) | 8 (3.0) | 0.682 |

| ECOGa | 1 [0–2] | 2 [1–3] | 1 [0–2] | 0.001 |

| CFSa | 3 [2–6] | 4 [3–7] | 3 [2–5] | <0.001 |

| APACHE II scorea | 15 [11–19] | 17 [13–21] | 14 [10–17] | <0.001 |

| Admission SOFA scorea | 4 [2–5] | 5 [3–6] | 3 [2–4] | <0.001 |

| PaO2/FiO2 on admissiona | 150 [113–226] | 129 [98–169] | 171 [122–241] | <0.001 |

| IMV requirement, n (%) | 162 (40.8) | 99 (75.6) | 63 (23.7) | <0.001 |

| IMV durationa, days | 12 [5–22] | 18 [11–27] | 5 [2–9] | <0.001 |

| Tracheostomy requirement, n (%) | 21 (5.3) | 18 (13.7) | 3 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Prone position, n (%) | 217 (54.7) | 89 (67.9) | 128 (48.1) | <0.001 |

| Septic shock, (admission) n (%) | 54 (13.6) | 29 (22.1) | 25 (9.4) | <0.001 |

| AKI (admission) n (%) | 112 (28.2) | 49 (37.4) | 63 (23.7) | 0.004 |

| Immunomodulatory therapies | ||||

| Systemic steroid, n (%) | 354 (89.2) | 126 (96.2) | 228 (85.7) | 0.002 |

| Convalescent plasma, n (%) | 31 (7.8) | 14 (10.7) | 17 (6.4) | 0.134 |

| Tocilizumab or Anakinra, n (%) | 26 (6.5) | 13 (9.9) | 13 (4.9) | 0.056 |

| IVIG, n (%) | 17 (4.3) | 10 (7.6) | 7 (2.6) | 0.021 |

| Outcome | ||||

| Secondary bacterial infection, n (%) | 172 (43.3) | 88 (67.2) | 84 (31.6) | <0.001 |

| Opportunistic infection, n (%) | 92 (23.2) | 61 (46.6) | 31 (11.7) | <0.001 |

| RRT, n (%) | 78 (19.6) | 40 (30.5) | 38 (14.3) | <0.001 |

| 28th days mortality, n (%) | 96 (24.2) | 45 (34.4) | 51 (19.2) | 0.001 |

| ICU mortality, n (%) | 124 (31.2) | 71 (54.2) | 53 (19.9) | <0.001 |

| Hospital mortality, n (%) | 133 (33.5) | 73 (55.7) | 60 (22.6) | <0.001 |

| ICU LOSa, days | 11 [6–19] | 24 [18–33] | 7 [4–11] | <0.001 |

| Hospital LOSa, days | 19 [12–31] | 31 [25–42] | 14 [10–22] | <0.001 |

CCI: chronic critical illness, ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, CFS: clinical frailty scale, APACHE: acute physiology and chronic health evaluation, SOFA: sequential organ failure assessment, PaO2/FiO2: Partial pressure of oxygen/Fraction of inspired oxygen, IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation, IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin, AKI: acute kidney injury, RRT: renal replacement therapy, ICU: intensive care unit, LOS: length of stay.

Continuous variables were indicated as median [IQR].

Comparison of laboratory parameters and components of SOFA scores on admission and 14th day in CCI patients are presented in Table 2. The values of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (10.2 vs. 14.2, p = 0.004), D-dimer (1.13 vs. 3.29, p < 0.001), and ferritin (438 vs. 592, p = 0.011) clinically significantly increased, while albumin level declined (3.1 vs. 2.5, p < 0.001). Median SOFA score raised from 5 to 7 (p < 0.001). Among 131 CCI patients, 79 patients (60.3%) were still requiring IMV on the 14th day.

Table 2.

Comparison of laboratory parameters and SOFA scores between admission and 14th day of ICU stay of CCI patients.

| Laboratory values and SOFA scoresa | Admission | 14th day | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphocyte, ×103/mm3 | 0.60 [0.34–0.87] | 0.61 [0.38–1.10] | 0.031 |

| NLR | 10.2 [4.0–22.0] | 14.2 [6.9–28.9] | 0.004 |

| Platelet, ×103/mm3 | 183 [126–243] | 196 [126–295] | 0.039 |

| BUN, mg/dl | 22.7 [16.0–34.8] | 32.0 [19.0–56.0] | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.93 [0.68–1.32] | 0.79 [0.59–1.31] | 0.153 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.1 [2.7–3.5] | 2.5 [2.3–2.7] | <0.001 |

| ALT, U/L | 27 [17–45] | 37 [22–56] | 0.012 |

| AST, U/L | 40 [27–76] | 39 [24–60] | 0.046 |

| Bilirubin, mg/dl | 0.57 [0.44–0.87] | 0.77 [0.44–0.87] | <0.001 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 1.13 [0.71–2.51] | 3.29 [1.72–7.54] | <0.001 |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dl | 574 [448–680] | 516 [376–658] | 0.022 |

| Ferritin, mcg/L | 438 [194–928] | 592 [273–1037] | 0.011 |

| CRP, mg/dl | 8.0 [3.3–15.4] | 8.8 [3.1–17.2] | 0.621 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/ml | 0.30 [0.11–1.69] | 0.30 [0.10–1.17] | 0.202 |

| LDH, U/L | 428 [284–581] | 421 [334–513] | 0.404 |

| PaO2/FiO2 | 129 [98–169] | 155 [117–206] | 0.059 |

| SOFA score | 5 [3–6] | 7 [3–11] | <0.001 |

| Respiration | 3 [2–4] | 3 [2–3] | 0.884 |

| Coagulation | 0 [0–1] | 0 [0–1] | 0.955 |

| Renal | 0 [0–1] | 0 [0–1] | 0.537 |

| Cardiovascular | 0 [0–0] | 0 [0–3] | <0.001 |

| Liver | 0 [0–0] | 0 [0–0] | 0.273 |

| Central nervous system | 0 [0–1] | 2 [0–4] | <0.001 |

SOFA: sequential organ failure assessment, NLR: neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio, BUN: Blood urea nitrogen, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, CRP: C-reactive protein, LDH: lactate dehydrogenase, PaO2/FiO2: Partial pressure of oxygen/Fraction of inspired oxygen.

Variables were indicated as median [IQR].

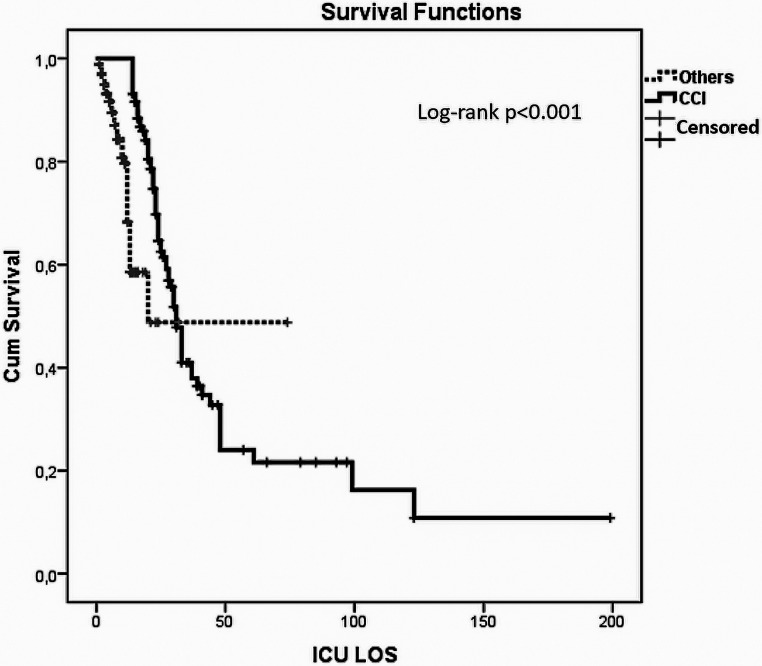

Multivariate analyses with age above 65 years old, ECOG > 1, CFS > 3, APACHE II score ≥ 15, admission SOFA ≥ 4, presence of septic shock and AKI on admission and systemic steroid use showed that IMV and PaO2/FiO2 < 150 were found to be independent variables for predicting CCI (Table 3). ROC curve in terms of predictors of CCI showed that IMV and PaO2/FiO2 < 150 have 0.76 and 0.70 sensitivity, 0.76 and 0.60 specificity with 0.76 and 0.65 AUC, p < 0.001 for both, respectively (Figure 1). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of patients with others and CCI revealed a significant difference in ICU mortality (Log-Rank p < 0.001) (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Factors associated with chronic critical illness in logistic regression analysis.

| Parameters | Chronic critical ıllness | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age > 65 years old | 1.72 (1.12–2.63) | 0.013 | NA | NA |

| ECOG > 1 | 1.84 (1.21–2.81) | 0.005 | NA | NA |

| CFS > 3 | 2.16 (1.41–3.31) | <0.001 | NA | NA |

| APACHE II score ≥ 15 | 2.37 (1.53–3.66) | <0.001 | NA | NA |

| SOFA scorea ≥ 4 | 3.92 (2.48–6.22) | <0.001 | NA | NA |

| PaO2/FiO2a < 150 | 3.43 (2.20–5.36) | <0.001 | 2.25 (1.36–3.71) | 0.002 |

| IMV | 9.97 (6.12–16.25) | <0.001 | 8.40 (5.10–13.83) | <0.001 |

| Septic shocka | 2.74 (1.53–4.91) | 0.001 | NA | NA |

| AKIa | 1.93 (1.22–3.03) | 0.005 | NA | NA |

| Systemic steroid | 4.20 (1.61–10.94) | 0.003 | NA | NA |

OR: odds ratio, CI: Confidence Interval, NA: not applicable, ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, CFS: Clinical Frailty Scale, APACHE: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, PaO2/FiO2: Partial pressure of oxygen/Fraction of inspired oxygen, IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation, AKI: acute kidney injury.

Admission.

Figure 1.

ROC curve for predictors of chronic critical illness.

ROC: Receiver-operator characteristics.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve.

Discussion

Current study showed that CCI prevalence was 33% in COVID-19 patients followed in the ICU. These patients who met the criteria of CCI had more than 50% mortality. Need of IMV and admission PaO2/FiO2 < 150 were the main predictors of CCI.

It is not possible to state a certain prevalence of CCI in intensive care patients due to the lack of consensus regarding the definition of CCI.13 Initially, the need for prolonged MV was proposed as CCI definition in which the prevalence of CCI was reported to be 10% in those patients.14 Fourteen to 21 or more days on MV or requirement of tracheostomy had been accepted as CCI in several studies which were emphasized in a review article by Loss et al.15 Kahn et al.16 adopted a new definition with the criteria of 8 or more days ICU stay with at least one following conditions: MV (for at least 96 hours in a single period), tracheotomy, stroke, head trauma, sepsis, and serious injury. According to this definition, CCI was seen in 7.6% and 9% of patients from nationwide epidemiological studies in the USA16 and Japan,17 respectively. Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center investigators from the University of Florida, USA, proposed a new definition for CCI described as prolonged intensive care hospitalization with persistent organ dysfunction.6 Stortz et al.18 first studied these criteria in 145 septic surgical ICU patients and showed that 49% of patients developed CCI. In 2019, Gardner et al.19 from the same study group investigated long-term survival among septic patients who were discharged from surgical ICU. In their cohort, 63 of 173 (36%) patients had developed CCI. A multicenter cross-sectional study from China in which the same definition was used reported that the prevalence of CCI was 30.7% in patients without COVID-19.20 The prevalence of CCI was 33% in our critically ill COVID-19 cohort. As a viral sepsis agent, COVID-19 has similar results like aforementioned studies with high CCI prevalence in comparison to the general ICU population in studies with previous definitions. In recent two studies including critically ill COVID-19 patients admitted to ICU showed that CCI was seen in 55% (n = 320)21 and 83.1% (n = 59)22 of cases in which different CCI definitions were utilized.

When the accelerating factors for the progression to CCI were examined in animal models and clinical studies, it was observed that especially immunological dysregulation and additional infections played a role irrespective of the first cause.23 This was interpreted as the second hit hypothesis.18 Prolonged hospitalization may cause the development of secondary infections acquired in the hospital and increase mortality. These repeated inflammatory challenges put the CCI patients in a situation called persistent inflammation immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome that we can consider as a phenotype of CCI, suggested by the same investigators who advocated the CCI definition that we utilized in our study.24 Kahn et al.16 revealed that nearly half of the sepsis patients had hospital-acquired infections and showed that those infections were one of the important contributors to CCI development in their epidemiological study regarding CCI in USA. In the current study, 67.2% and 46.6% of patients developed secondary bacterial and opportunistic infections, respectively. Septic shock was also shown as the robust predictor of CCI in previous studies.18,23 In our cohort, 22.1% of patients with CCI had a septic shock on admission. The presence of ARDS and an increase in SOFA score have been indicated as risk factors associated with CCI in recent two studies regarding CCI in COVID-19 patients.21,22 We found that requirement of IMV and the presence of admission PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 150 were the independent predictors of CCI. More than half of the patients in our CCI cohort passed away. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed that CCI significantly increased ICU mortality in COVID-19 patients.

Previous nationwide epidemiological studies have shown that the prevalence of CCI escalates with age.16,17 In our cohort, patients with CCI were older than others. In addition, CCI patients had worse disease performance status which could be related to age. It is known that the severity of the disease at the time of admission determines the outcome of the patients in the ICU.25 Uncontrolled inflammation brought by acute respiratory failure requiring MV or sepsis can lead to prolongation of organ failure, ICU-acquired weakness, and neuropsychiatric problems, which are the biggest difficulties encountered among patients with CCI.26 In our study, APACHE-II and admission SOFA scores were higher in the CCI group. Admission PaO2/FiO2 ratio was lower, requirement of IMV and tracheostomy were more common in CCI patients. Median SOFA score was still high on the 14th day of admission in CCI patients.

Considering that there is no clear definition of CCI, it should be emphasized that the proposed criteria were used for the first time for medical ICU patients in the English literature in our study, based on the SOFA score, which evaluates organ failure, is a well-known and easily applied for patients requiring ICU admission. By using these criteria, it will set light on further studies in terms of determining the true burden of CCI. However, there are several limitations to the current study. First, generalization of the results in terms of the prevalence of CCI in the general ICU population is a major concern due to its retrospective design and limited patient number only including COVID-19 patients. More data is required to get appropriate decisions. For more clarification, data should be collected and included from another region as well. Second, almost all patients received systemic corticosteroids for standard treatment of COVID-19 which may be a confounder factor for the development of CCI. Third, patient outcomes may have been affected due to the disruption of physiotherapy practices during the pandemic situation. Fourth, since this study only examined the CCI status in COVID-19 patients during ICU stay, it could not provide us the information about the long-term effects that may develop due to COVID-19. In addition, our data was collected from 20th March 2020 to 15th June 2021 and results are influenced by the fact that no specific therapies were available at that time, this is why it is important to highlight the presence of newer therapies like antiviral drugs that may prevent hospitalization.27,28

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that one-third of COVID-19 patients may develop CCI accompanied by more than 50% mortality during their hospitalization in ICU. The requirement of IMV, and moderate and severe hypoxemia during ICU admission were the main determinants of CCI. It is necessary to investigate the real burdens of the CCI situation like physical, cognitive, psychiatric, and economic consequences secondary to COVID-19 whose prolonged effects on patients have been proven.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-chi-10.1177_17423953231161333 for Chronic critical illness in critically ill COVID-19 patients by Burcin Halacli, Mehmet Yildirim, Esat Kivanc Kaya, Ege Ulusoydan, Ebru Ortac Ersoy and Arzu Topeli in Chronic Illness

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Burcin Halacli https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7216-7438

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Wu Q, Hu D, Ren J. Chronic critical illness should be considered in long-term mortality study among critical illness patients. Crit Care Med 2015; 43: 57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prescott HC. Preventing chronic critical illness and rehospitalization: a focus on sepsis. Crit Care Clin 2018; 34: 501–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson JE, Cox CE, Hope AAet al. et al. Chronic critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182: 446–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desarmenien M, Blanchard-Courtois AL, Ricou B. The chronic critical illness: a new disease in intensive care. Swiss Med Wkly 2016; 146: w14336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girard K, Raffin TA. The chronically critically ill: to save or let die? Respir Care 1985; 30: 339–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loftus TJ, Mira JC, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, et al. Sepsis and critical illness research center investigators: protocols and standard operating procedures for a prospective cohort study of sepsis in critically ill surgical patients. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e015136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halacli B, Kaya A, Topeli A.Critically-ill COVID-19 patient. Turk J Med Sci. 2020; 50(SI-1): 585–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muneeb Hassan M, Ameeq M, Jamal Fet al. et al. Prevalence of COVID-19 among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and tuberculosis. Ann Med 2023; 55: 285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halaçlı B, Topeli A.Implementation of post-intensive care outpatient clinic (I-POINT) for critically ill COVID-19 survivors. Turk J Med Sci. 2021; 51(SI-1): 3350–3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA 2016; 315: 801–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron 2012; 120: c179–c184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacIntyre CR, Chughtai AA, Barnes M, et al. The role of pneumonia and secondary bacterial infection in fatal and serious outcomes of pandemic influenza a(H1N1)pdm09. BMC Infect Dis 2018; 18: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li S, Wu X, Ren J. Diagnostic criteria for chronic critical illness should be standardized. Crit Care Med 2021; 49: e1060–e1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchioni A, Fantini R, Antenora Fet al. et al. Chronic critical illness: the price of survival. Eur J Clin Invest 2015; 45: 1341–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loss SH, Nunes DSL, Franzosi OSet al. et al. Chronic critical illness: are we saving patients or creating victims? Rev Bras Ter Intensiva 2017; 29: 87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahn JM, Le T, Angus DC, et al. The epidemiology of chronic critical illness in the United States*. Crit Care Med 2015; 43: 282–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohbe H, Matsui H, Fushimi Ket al. et al. Epidemiology of chronic critical illness in Japan: a nationwide inpatient database study. Crit Care Med 2021; 49: 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stortz JA, Mira JC, Raymond SL, et al. Benchmarking clinical outcomes and the immunocatabolic phenotype of chronic critical illness after sepsis in surgical intensive care unit patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2018; 84: 342–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner AK, Ghita GL, Wang Z, et al. The development of chronic critical illness determines physical function, quality of life, and long-term survival among early survivors of sepsis in surgical ICUs. Crit Care Med 2019; 47: 566–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li SS, Wu J, Yu XY, et al. A multicenter cross-sectional study on chronic critical illness and surgery-related chronic critical illness in China. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi 2019; 22: 1027–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roedl K, Jarczak D, Boenisch O, et al. Chronic critical illness in patients with COVID-19: characteristics and outcome of prolonged intensive care therapy. JCM 2022; 11: 1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pérez-Anibal E, Contreras-Arrieta S, Rojas-Suárez J, et al. Association of chronic critical illness and COVID-19 in patients admitted to intensive care units: a prospective cohort study. Archivos de Bronconeumología. Published online November 2022:S0300289622005932. DOI: 10.1016/j.arbres.2022.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchioni A, Tonelli R, Sdanganelli A, et al. Prevalence and development of chronic critical illness in acute patients admitted to a respiratory intensive care setting. Pulmonology 2020; 26: 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fenner BP, Darden DB, Kelly LS, et al. Immunological endotyping of chronic critical illness after severe sepsis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020; 7: 616694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Godinjak A, Iglica A, Rama A, et al. Predictive value of SAPS II and APACHE II scoring systems for patient outcome in a medical intensive care unit. Acta Med Acad 2016; 45: 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villar J, Blanco J, Zhang Het al. et al. Ventilator-induced lung injury and sepsis: two sides of the same coin? Minerva Anestesiol 2011; 77: 647–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, et al. Oral nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2022; 386: 1397–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scioscia G, De Pace CC, Giganti G, et al. Real life experience of molnupiravir as a treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection in vaccinated and unvaccinated patients: a letter on its effectiveness at preventing hospitalization. Ir J Med Sci. Published online December 1, 2022. DOI: 10.1007/s11845-022-03241-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-chi-10.1177_17423953231161333 for Chronic critical illness in critically ill COVID-19 patients by Burcin Halacli, Mehmet Yildirim, Esat Kivanc Kaya, Ege Ulusoydan, Ebru Ortac Ersoy and Arzu Topeli in Chronic Illness