Abstract

Narrowband-ultraviolet B (NB-UVB) has been used to treat skin diseases such as psoriasis. Chronic use of NB-UVB might cause skin inflammation and lead to skin cancer. In Thailand, Derris Scandens (Roxb.) Benth. is used as an alternative medicine to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for low back pain and osteoarthritis. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the potential anti-inflammatory effect of Derris scandens extract (DSE) on pre- and post exposed NB-UVB human keratinocytes (HaCaT). The results indicated that DSE could not protect HaCaT from cell morphology changes or DNA fragmentation and could not recover cell proliferation ability from the NB-UVB effects. DSE treatment reduced the expression of genes related to inflammation, collagen degradation, and carcinogenesis, such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS, COX-2, MMP-1, MMP-9, and Bax. These results indicated the potential use of DSE as a topical preparation against NB-UVB-induced inflammation, anti-aging, and prevention of skin cancer from phototherapy.

Keywords: Derris scandens, Narrowband-ultraviolet B, Human keratinocytes, UV protection, Anti-inflammation, Phototherapy

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Derris scandens extract (DSE) possessed anti-inflammation to the narrowband-UVB exposed HaCaT.

-

•

DSE exhibited more potent activity than its major compounds.

-

•

The results suggested the potential use of DSE to reduce phototherapy side effects on skin.

1. Introduction

Derris scandens is a plant of the family Fabaceae that Thai traditional healers use to treat pain in the bones and joints [21]. It is an herbal medicine available in the Thai National List of Essential Medicines for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Clinical studies support their effectiveness and safety use in patients [2,42]. The stem extract exhibits immunomodulatory activity by increasing lymphocyte proliferation, stimulating IL-2, and enhancing neutral killer cell function in HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) patients and healthy volunteers [43]. The chemical constituents of the stem include isoflavones and isoflavone glycosides [36,25], such as lupalbigenin and genistein-7-O- [α-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 to 6)-β-glucopyranoside] (GTG). GTG is a biomarker of this plant in the monograph of the Thai Herbal Pharmacopoeia or THP [6].

Phototherapy is one of the therapeutic approaches to various skin diseases, such as psoriasis, by exposure to ultraviolet A (UVA) or ultraviolet B (UVB). Although it can induce immunosuppression and alter cell proliferation, these side effects are less severe than when using immunosuppressive drugs [5]. The use of broadband UVB (BB–UVB, 290–320 nm) as the first-line treatment of psoriasis was later replaced with narrowband UVB (NB-UVB, 305–315 nm with a peak at 311 nm) due to its safety (5–10 times less erythrogenic than BB-UVB) and greater effectiveness, since 8- to 10-fold higher doses of NB-UVB are equivalent to BB-UVB. NB-UVB has also been used in atopic dermatitis, mycosis fungoides, and vitiligo. Several clinical studies have reported that UVB narrowband PL-L/PL-S lamps are safe and effective because their very narrow waveband emission requires a much shorter time and less harmful effects and is less carcinogenic. However, skin exposure to UVB could induce burning symptoms post phototherapy, including moderate-to-severe redness, tenderness, pain, pruritus, photoaging, and tanning [41], and cause photocarcinogenesis, inflammation, and immunosuppression.

UV increases the formation of reactive oxygen species such as superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals [9], which lead to premature skin aging. It also increases matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and reduces procollagen I production [35]. Matrix metalloproteinase type I (MMP-1) is produced by keratinocytes and is a subtype of collagenase that digests collagen. Therefore, MMP-1 relates to skin aging [18] of UVB-exposed skin. MMP-9 is a subtype of gelatinase that degrades gelatin and collagen. The upregulation of the cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) gene in the epidermis is markedly increased after UV exposure. COX-2 inhibitors such as celecoxib have been used in animal models to prevent UV-induced skin cancers [5]. Moreover, UVB exposure leads to the secretion of cytokines such as IL-1, IL-2, IL-6 (interleukin 6), and IL-8 and induces nitric oxide production by inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [39].

To date, there are few topical anti-inflammatory products available on the market to reduce the side effects of phototherapy. The well-known topical anti-inflammation is aescin (triterpenoid) for venosis. It was documented that genistein (isoflavone) possesses potent chemopreventive effects against UVB-induced carcinogenesis [26]. These reasons drew our attention to searching for a plant extract to relieve NB-UVB-induced skin inflammation. Since isoflavones are commonly distributed in fabaceous plants, Derris scandens, an anti-inflammatory herb, was chosen to investigate its ability to protect against NB-UVB-induced inflammation in human keratinocytes (HaCaT).

This study aimed to investigate the effect of ethanolic extract from D. scandens stem (DSE) on NB-UVB-exposed human keratinocytes (HaCaT) to evaluate the potential use of DSE as a topical product for anti-NB-UVB-induced inflammation.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Chemicals

All reagents and solvents were AR grade. General chemicals were from Merck, Germany. GTG and lupalbigenin were purified from D. scandens stems. Cell culture media and supplements were purchased from Gibco (USA). TRIzol reagent, DNAzol reagent, and Superscript® Ш RT were purchased from Invitrogen (USA). SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix was purchased from Bio–Rad (USA). L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA), Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (L-NAME), lipopolysaccharides (LPS), mushroom tyrosinase (50 KU), gallic acid, rutin, kojic acid, and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Germany).

2.2. Preparation of D. scandens extract (DSE)

D. scandens stems were collected from Khon Kaen Province, Thailand. The voucher specimen number was MSU.PH-FAB-D1. It was washed, chopped, dried at 50 °C, and ground. The 200 g dried powder was defatted by maceration two times with hexane. After that, it was further extracted twice with 95% EtOH 1500 mL for three days. The extract was evaporated to dryness using a rotary evaporator and freeze drier. The dried extract (11.43 g, yield 5.72%) was kept at −20 °C until use.

2.3. Purification of marker compounds: genistein-7-O-[α-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 → 6)-β-glucopyranoside] (GTG) and lupalbigenin

Dried stem powder of D. scandens (2.0 kg) was extracted with n-hexane and 95% EtOH using a Soxhlet apparatus. Then, they were evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure to provide n-hexane (20.0 g) and EtOH (94.0 g) extracts. The EtOH extract was suspended in H2O and partitioned with CHCl3 and n-BuOH. The n-BuOH fraction (18.0 g) was subjected to a silica gel column using the solvent system CHCl3 to yield lupalgenin (230 mg, CHCl3–MeOH–H2O (15:7:1, and finally 25:25:2) to afford GTG (297 mg). The chemical structures of lupalbigenin were elucidated by 1H NMR and 13C NMR, and GTG was identified by comparing the Rf value to the standard GTG obtained from Prof. Dr. Waraporn Putalun [14].

2.4. Characterization of DSE

2.4.1. TLC and HPLC chromatogram

DSE (10 mg/mL) was applied to a TLC silica gel GF254 precoated plate (Merck, Germany). The mobile phases were EtOAc–HCOOH–H2O (90:5:5) for GTG and hexane-EtOAc (6: 4) for lupalbigenin and detected under UV 254 nm.

HPLC was performed by using an HPLC machine (Agilent, LC1100) and a RP-18 column 250 × 4.0 mm, 5 μm, 100 Å (Kromasil, Phenomenex, USA). A mobile phase gradient of solvent A (H2O) and solvent B (CH3CN) was used as follows: 0:0 (t = 0), 50:50 (t = 5), 30:70 (t = 15), 0:100 (t = 25), 0:100 (t = 40), 100:0 (t = 45), flow rate 0.8 mL/min, UV detector at 254 nm, and the injection volume 10 μL of 0.5 mg/mL DSE and 0.1 mg/mL of lupalbigenin and GTG.

2.4.2. Total phenolic content

The total phenolic content was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetric method and calculated from the standard graph of gallic acid in the concentration range of 3.125–100 μg/mL. The reaction mixture was performed on a 96-well plate and consisted of 20 μL DSE or gallic acid in MeOH, 100 μL 10% Folin-Ciocalteu's reagent, and 80 μL 7% sodium carbonate. They were mixed and incubated at room temperature for 30 min and protected from light. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 760 nm. The total phenolic content was calculated from the standard graph of gallic acid, y = 0.1231x + 0.0166, R2 = 0.9971, and was presented as mg gallic acid equivalent (GAE)/g extract.

2.5. Antioxidant assay of DSE

2.5.1. DPPH free radical scavenging assay of DSE

The assay was performed on a 96-well plate. The reaction mixture contained 100 μL of 0.2 mM 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), and the sample solution was 100 μL and incubated at room temperature for 30 min (protected from light). The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 517 nm. Rutin was used as the positive control. % Free radical scavenging was calculated by using the following formula:

% Free radical scavenging = [ADPPH-(Asample-Ablank)] x 100/ADPPH, where ADPPH is the absorbance of DPPH solution, Asample is the absorbance of the reaction mixture of the sample, and Ablank is the absorbance of each sample concentration. The IC50 values of rutin and DSE were compared.

2.5.2. Superoxide anion radical scavenging assay of DSE

The assay was based on a nonenzymatic phenazine methosulfate-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (PMS/NADH) system, generating superoxide radicals. This resulted in the reduction of nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) to purple formazan. The inhibitory effect of decreasing NBT formation by quenching superoxide radicals was observed. The reaction was composed of 50 μM NBT 40 μL, 78 μM NADH 40 μL and 40 μL samples and mixed thoroughly. After that, 40 μL of 35 μM PMS was added and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 560 nm (n = 3). % Inhibition of superoxide anion was calculated by using the formula: % Inhibition = [(Acontrol – As mple)/Acontrol)] x 100, where Acontrol was the absorbance of the complete reaction without the tested samples, and Asample was the absorbance of the reaction in the presence of samples. Rutin was used as a positive control. The IC50 values of rutin and DSE were compared [40].

2.6. Tyrosinase inhibition activity of DSE

The assay was performed in triplicate in a 96-well plate and protected from light. The reaction mixtures contained 100 units/mL mushroom tyrosinase 40 μL, and 80 μL of test samples were incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The substrate 12 mM L-DOPA 80 μL was added and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. Kojic acid was used as a positive control. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 490 nm and calculated for the % tyrosinase inhibition as follows: % Inhibition = [(Acontrol – Asample)/Acontrol)] x 100, where Acontrol was the absorbance of the reaction without the tested samples, and Asample was the absorbance of the reaction of the samples. The IC50 values of kojic acid and DSE were compared.

2.7. Cell culture

2.7.1. Culture of HaCaT and RAW264.7 cells

HaCaT cells were obtained from Cell Line Service (CLS, Germany). The cells were cultured in a 75 cm2 cell culture flask with DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) supplemented with 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum), 1% nonessential amino acids (NEAAs) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

RAW 264.7 (ATCC) cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

2.7.2. MTT assay

Cell viability was measured using an MTT assay [27] in a 96-well plate. HaCaT (7500 cells/well) or RAW 264.7 cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were seeded for 24 h. Various concentrations of DSE in the complete medium and 0.1% DMSO were used to treat cells in both MTT assay and all of the cell-based experiments. The samples were incubated with cells for 24 h. After that, the medium was discarded, and the cells were washed with PBS before adding 100 μL of 0.5 mg/mL MTT and incubated for 2 h. The formazan was dissolved by adding 50 μL DMSO, and the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 540 nm. The percentage of cell viability was calculated as follows: % Cell viability = (Asample/Auntreated control) x 100, where Asample was the absorbance of cells treated with the sample, and Auntreated control was the absorbance of the untreated control.

2.8. Inhibition of nitric oxide (NO) production assay in RAW264.7 cells

The assay was performed on a 96-well plate. RAW264.7 cells were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/well for 24 h in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. LPS 100 ng/mL was used to induce NO production. The cells were treated with the test sample adding with LPS. L-NAME 100 μM in the presence of LPS was used as a positive control. The culture was incubated for 24 h, and the media was collected and used to determine NO by using the Griess assay. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 540 nm and calculated for % NO production as follows:

% NO production = (Asample/Acontrol) x 100, where Asample is the absorbance of LPS-induced RAW264.7, which was treated with the sample, and Acontrol is the absorbance of LPS-stimulated RAW264.7.

2.9. NB-UVB irradiation of HaCaT

HaCaT 7500 cells/well were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. The medium was then discarded, and the wells were washed with 50 μL cold PBS. NB-UVB lamp 305–315 nm which peaks at 311 nm (PL-S 9W/01/2P, Philips, Poland) was used to irradiate HaCaT at 10 cm distance long. The dose of NB-UVB was measured by a Digital UV-AB Light Meter (General Tools, Taiwan). The prescribed dose used in this study was 3.79 J/cm2.

2.10. NB-UVB protective assay of DSE in NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT cells

Pretreatment with DSE was performed as follows. HaCaT 7500 cells/well were seeded for 24 h, then the medium culture was changed to DSE in the complete DMEM and further incubated for 24 h. After that, cells were irradiated with NB-UVB for 20 min and incubated in the complete DMEM without DSE for 24 h. HaCaT-exposed NB-UVB was determined for % cell viability by MTT assay.

2.11. Recovery effect of DSE on NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT cells

DSE posttreatment was performed on NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT cells. After cell irradiation, the cells were treated with DSE 25 μg/mL for 24, 48, and 72 h. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay.

2.12. Determination of genomic DNA fragmentation of HaCaT

HaCaT cells (1.6 × 106 cells/dish) were cultured in a 6 cm cell culture dish for 24 h. DSE was added to the culture 24 h before NB-UVB exposure (pretreatment with DSE) or after NB-UVB exposure (posttreatment with DSE) and further incubated for 24 h. Then, the cells were harvested and DNA was extracted by using DNAzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The genomic DNA was measured for A260 and A280 by using a UV spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan). Five micrograms of DNA was loaded into a 1.8% (w/v) agarose gel and photographed by using Gel Doc (SynGene).

2.13. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) of NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT cells

HaCaT cells (1.6 × 106 cells/dish) were treated with 25 μg/mL DSE 24 h before NB-UVB exposure or after NB-UVB exposure in a 6 cm cell culture dish, and the cells were further incubated for 24 h before being harvested. Total RNA was extracted by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Then, total RNA was measured for quality and quantity using a MaestroNano Spectrophotometer (Maestrogen, USA) and was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Superscript Ш, Invitrogen). qPCR was conducted in a CFX96 Real-Time PCR machine (BioRad) using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio–Rad, USA) as described by the manufacturer. Briefly, in a 10 μL reaction volume, the following components were added: 3 μL of 10× diluted cDNA, 5 μL of 2× SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix, 0.2 μL of each 10 μM primer, and 1.6 μL of RNase-free water. The sequences of the primers are shown in Table 2. The PCR cycling conditions were initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 57 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. To verify the amplification product, the melting curve analysis was 95 °C for 5 s, 65 °C for 5 s, and 95 °C for 5 s. The housekeeping gene GAPDH was used as a reference mRNA control, and the relative expression was calculated using the 2 -ΔΔCT method [24].

Table 2.

Primers for qPCR analysis.

| Gene | Primer sequences (5′→ 3′) | Size (bp) | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1α | Forward: GATCAGTACCTCACGGCTGC | 244 | NM_000575.5 |

| Reverse: TGCCGTGAGTTTCCCAGAAG | |||

| IL-1β | Forward: CAGCTCTCTCCTTTCAGGGC | 237 | NM_000576.3 |

| Reverse: ACACTGCTACTTCTTGCCCC | |||

| IL-6 | Forward: GTGTGAAAGCAGCAAAGAGGC | 160 | NM_000600.5 |

| Reverse: CTGGAGGTACTCTAGGTATAC | |||

| iNOS | Forward: CCTGGAGGTGCTAGAGGAGT | 166 | NM_000625.4 |

| Reverse: ATCTCCGGTGTGGTAGGTGA | |||

| COX-2 | Forward: TTGCATTCTTTGCCCAGCAC | 261 | NM_000963.4 |

| Reverse: ACCGTAGATGCTCAGGGACT | |||

| MMP-1 | Forward: TGTGGTGTCTCACAGCTTCC | 233 | NM_002421.4 |

| Reverse: ATCTGGGCTGCTTCATCACC | |||

| MMP-9 | Forward: ACGATGACGAGTTGTGGTCC | 247 | NM_004994.3 |

| Reverse: GGTTTCCCATCAGCATTGCC | |||

| Bax | Forward: CCAAGAAGCTGAGCGAGTGT | 204 | NM_138761.4 |

| Reverse: CCTTGAGCACCAGTTTGCTG | |||

| GADPH | Forward: GAGAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTT | 231 | NM_002046.6 |

| Reverse: AGTGATGGCATGGACTGTGG |

2.14. Statistical analysis

The results were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA using SPSS Statistics 24. The difference within the group was analyzed by Duncan's test. P < 0.05 or P < 0.01 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Derris scandens extract

The ethanolic extract, DSE (11.43 g), was obtained as a dry powder with a pale brown color and yielded 5.72% (w/w) of the dried stem. The chemical constituents of DSE detected by both TLC and HPLC mainly consisted of GTG and lupalbigenin (Fig. 1). The total phenolic content of DSE was 31.14 ± 8.77 mg GAE/g extract and exhibited DPPH radical scavenging with IC50 158.27 ± 21.62 μg/mL. DSE possessed mild activities of both superoxide anion radical scavenging (15.16 ± 0.04% at 250 μg/mL) and tyrosinase inhibition (25.63% inhibition at 400 μg/mL). The results indicated that DSE could not attenuate the NB-UVB effect that causes free radical, anion superoxide, and melanin production by tyrosinase activity.

Fig. 1.

Chromatogram of Derris scandens extract (DSE) showing the major chemical components, GTG and lupalbigenin. A–C: HPLC chromatogram (A): DSE; (B): GTG; and (C): lupalbigenin. D–E: TLC chromatogram (D): TLC chromatogram of DSE and GTG; solvent system: EtOAc: HCOOH: H2O (90: 5: 5); Lane 1: DSE; Lane 2: GTG (Rf 0.31) (E): TLC chromatogram of DSE and lupalbigenin; solvent system: hexane: EtOAc (6: 4); Lane 1: DSE; Lane 2: lupalbigenin (Rf 0.86).

3.2. NO production of DSE, GTG, and lupalbigenin in LPS-treated RAW264.7 macrophages

The maximum noncytotoxic dose of 50 μg/mL DSE and that of GTG at 200 μg/mL (264.32 μM) reduced NO production by 46% and 13.53%, respectively (Fig. 2), while the noncytotoxic dose of lupalbigenin, which was 5 μg/mL (12.3 μM), showed only 4.6% inhibition. The results revealed that the anti-inflammatory effect of DSE by inhibiting nitric oxide production might not be due to the action of lupalbigenin and GTG. Therefore, DSE was further used to evaluate the anti-inflammatory effects in NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT cells.

Fig. 2.

Nitric oxide production of RAW264.7 macrophages in the presence of DSE (A) and GTG (B) and % cell viability in the presence of DSE (C) and GTG (D). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, compared to LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells (n = 8). LPS 100 ng/mL was used to induce nitric oxide production, and 250 μM L-NAME was a positive control.

3.3. Effect of NB-UVB on genomic DNA of HaCaT

NB-UVB exposure to HaCaT caused a reduction in cell viability (Fig. 3A). The minimal irradiation time of NB-UVB that led to 60% cell viability of HaCaT was 20 min (Fig. 3A), which was the prescribed dose of 3.79 J/cm2. NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT resulted in genomic DNA fragmentation, presented as the ladder of smaller DNA in the agarose gel (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effect of NB-UVB on HaCaT cells. Effect of NB-UVB irradiation compared to non-NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT cells. (A): % Cell viability of various NB-UVB exposure times (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 compared to no NB-UVB; n = 8) (B): Agarose gel electrophoresis of genomic DNA from no NB-UVB-exposed and NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT (pretreatment: DSE was added to HaCaT before NB-UVB exposure; posttreatment: DSE was added to HaCaT after NB-UVB exposure).

3.4. Effect of pre- and posttreatment DSE on NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT

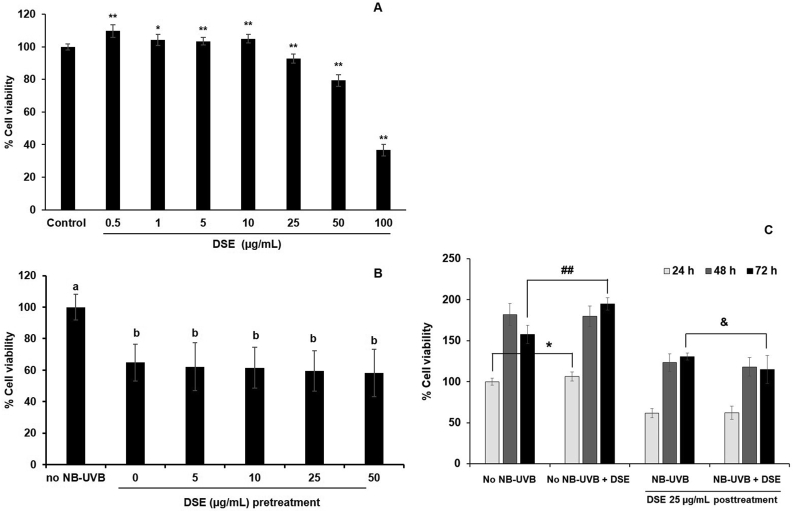

DSE 0.5–50 μg/mL was the nontoxic concentration range for normal HaCaT (Fig. 4A). The results showed that pretreatment with DSE within this range did not restore the viability of the irradiated HaCaT cells (Fig. 4B). Posttreatment of DSE to NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT cells increased the % cell viability in a time-dependent manner with the same ratio as that of the non-NB-UVB HaCaT control (Fig. 4C). These results indicated the loss of cell proliferation ability in NB-UVB-irradiated HaCaT cells, which DSE could not recover. Therefore, the increase in % viability of NB-UVB HaCaT cells after post-DSE treatment after 24, 48, and 72 h of exposure as shown in Fig. 4C reflected the self-recovery of HaCaT cells, not from the activity of DSE. The results also showed that treatment with DSE before and after NB-UVB irradiation did not prevent the breakage of DNA although pretreatment with DSE provided a tendency toward less DNA fragmentation than posttreatment (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 4.

Effect of DSE on % cell viability of HaCaT. (A): DSE treatment of nonexposed NB-UVB HaCaT cells (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01; compared to untreated control, n = 8) (B): pretreatment of DSE in NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT cells (% cell viability of treatments were compared to no NB-UVB group, the letter indicated significant different between group, the same letter meant no different, n = 8) (C): posttreatment of 25 μg/mL DSE in NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT cells compared to no NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT cells at 24, 48, and 72 h (% cell viability was compared to no NB-UVB group at 24 h, significant different was presented between no NB-UVB and NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT at the same incubation time, ∗p < 0.05 of no NB-UVB HaCaT at 24 h, ##p < 0.01 of no NB-UVB HaCaT at 72 h, and &p < 0.05 of NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT at 72 h, n = 8).

3.5. Gene expression in NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT cells

NB-UVB resulted in the upregulation of all target genes: iNOS, COX-2, MMP-1, MMP-9, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and Bax (Fig. 5). The expression level of IL-6 was dramatically high after NB-UVB exposure (Fig. 5G), while that of MMP-1 was the slightest increase (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Relative expression of genes by qPCR in HaCaT cells. DSE was applied to HaCaT cells before or after NB-UVB irradiation (pretreatment or posttreatment, respectively). (A): iNOS; (B): COX-2 (C): MMP-1; (D): MMP-9 (E): IL-1α; (F): IL-1β (G): IL-6; (H): Bax (Presented as fold expression compared to non-NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT, different letters a-e presented significantly different between group, p < 0.05, n = 3).

DSE (25 μg/mL) significantly downregulated the gene expression levels of COX-2, iNOS, MMP-1, MMP-9, and IL-6 in non-NB-UVB HaCaT cells (0.26-, 0.43-, 0.74-, 0.82- and 0.99-fold of the untreated control, respectively) and significantly increased the expression of IL-1α, IL-1β, and Bax (1.74-, 1.77-, and 1.26-fold, respectively), as shown in Fig. 5.

Pretreatment of DSE with HaCaT 30 min before NB-UVB irradiation decreased the expression of iNOS, MMP-9, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and Bax but not COX-2 or MMP-1. The posttreatment of DSE after NB-UVB exposure showed a higher level of gene downregulation than those from the pretreatment condition in all target genes, except only IL-6, which was reduced to a comparable level between pre- and post-NB-UVB treatment. The ability of DSE to decrease gene expression of the posttreatment NB-UVB HaCaT was in the range of 38–69%. The results indicated that NB-UVB exposure induced the overexpression of genes related to inflammation, collagen degradation, and carcinogenesis. Pretreatment with DSE presented mild prevention of those effects. Posttreatment with DSE attenuated the inflammatory process and collagen degradation and prevented cancer at the gene expression level.

4. Discussion

4.1. Dose of NB-UVB

Phototherapy treats skin diseases such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and vitiligo by exposure to specific wavelengths of light, including ultraviolet A and B (UVA and UVB). The wavelength 313 nm, which is NB-UVB, has been reported as the most effective UVB wavelength for treating psoriasis [33] and has been used as an effective therapy for several cutaneous conditions [28]. The UVB lamp with narrow waveband of 305–315 nm (peaks at 311 nm) has been developed which is suitable for various applications includes phototherapy. Since NB-UVB phototherapy for psoriasis is used daily, erythema from skin inflammation [7], photoaging due to decreased collagen [4], and skin cancer could occur [3].

The dose of NB-UVB in this study provided effects on keratinocytes in morphology change, DNA fragmentation, and gene expression level. The dose used was related to phototherapy, which could be started from 300 to 500 mJ/cm2 and reach the maximum dose of 2–3 J/cm2 depending on the skin type [32]. NB-UVB irradiation for 4–6 h (dosages 144–216 J/cm2) was also used to study the effect of annual UVB irradiation on the skin, which was comparable to natural exposure to solar UVB irradiation of skin [10]. The cumulative dose of NB-UV phototherapy to patients with vitiligo, alopecia areata, lichen simplex, and psoriasis vulgaris is 17–28 J/cm2 [7].

4.2. Characterization and photoprevention of DSE

Although genistein has been well documented as a potent photopreventive isoflavone from the fabaceous plant [26], this compound could not be detected in DSE. The diprenyl isoflavone lupalbigenin and the glycoside genistein GTG were the major constituents (Fig. 1). GTG is defined as a biomarker in the Thai Herbal Pharmacopoeia monograph of D. scandens, while lupalbigenin has been reported as an anticancer substance [45,37]. Both possessed weak nitric oxide reduction in macrophage RAW 264.7 cells (Fig. 2). This indicated that the anti-inflammatory effect of DSE might not occur through the inhibition of nitric oxide. From previous reports, GTG inhibits cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) with IC50 values of 1500 and 2500 μM, respectively, and is suggested to be the reservoir of genistein [22]. Therefore, increasing the photoprotective potency of DSE could be achieved by hydrolysis of GTG in DSE to release genistein. On the other hand, lupalbigenin possesses an anticancer effect on various human cancer cell lines at a concentration of 40 (16.26 μg/mL) via induction of apoptosis [45]. In this study, at a nontoxic dose of 5 μg/mL (12.3 μM), only weak nitric oxide inhibition (4.6%) was observed in RAW264.7 cells. Therefore, whether lubalbigenin might not be an active compound for anti-inflammation, it might be useful against NB-UVB-induced skin cancer. Since the major compounds lupalbigenin and GTG exhibited less anti-inflammatory potency than DSE based on NO reduction, DSE was chosen for further investigation in HaCaT.

NB-UVB irradiation affects the epidermal layer of the skin. Keratinocytes are the first layer exposed and lead to ROS production (such as the superoxide anion radical, and hydroxyl radical), and increase melanin production via tyrosinase. From our results, DSE exhibited a mild effect on superoxide anion scavenging, moderate DPPH radical scavenging, and slightly inhibited tyrosinase (Table 1). This indicated that DSE might not be suitable for NB-UVB skin treatment by reducing oxidative stress, antioxidant, and anti-pigmentation. This result was consistent with a previous study of the D. scandens extract, which explained that its anti-inflammatory effect is not due to antioxidants because of its weak antioxidant activity [21]. However, since DPPH and superoxide anion scavenging assays are indirect methods for antioxidative activities, the determination of the intracellular ROS such as DCFH-DA (dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate) assay [38] should be further determined to clarify the direct effect of DSE to HaCaT.

Table 1.

Characterization of DSE.

| DSE | |

|---|---|

| Total phenolic content (mg GAE/g extract) | 31.14 ± 8.77 |

| DPPH free radical scavenginga (IC50 μg/mL) | 158.27 ± 21.62 |

| Superoxide anion radical scavenging assayb (IC50 μg/mL) | >250 |

| Tyrosinase inhibitorc (IC50 μg/mL) | >400 |

IC50 of rutin = 7.39 ± 0.13 μg/mL.

IC50 of rutin = 111.22 ± 18.98 μg/mL.

IC50 of kojic acid = 13.63 ± 4.88 μg/mL.

4.3. Effect of NB-UVB on HaCaT cells

Keratinocytes are cells in the epidermis that are exposed to the environment. It has been used as a study model on UVB-exposed effects, skin irritation, skin cancer, mutagenicity, genotoxicity, and cytotoxicity to toxic substances [19]. It can be used to describe the effect of any compound on human skin [47] and are a significant target of NB-UVB phototherapy. It was known that the UVB prevention effect could be from polyphenolic compounds that possess antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities which function by decreasing the levels of UVB-induced intracellular ROS, increasing the expression of anti-apoptotic factors, such as Bcl-2, and decreasing the expression of pro-apoptotic factors, such as Bax [11].

The effects of NB-UVB irradiation on HaCaT cells in our study were demonstrated by the decrease in cell viability, DNA breakage, and loss of cell proliferation, which was in line with a previous report [17]. The UVB induce ROS generation, decrease in cell survival, and induce apoptosis in human keratinocytes. The main damages resulting from UVB are cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer formation [12]. Cells undergoing apoptosis have characteristics such as nuclear DNA fragmentation and cell shrinkage [31]. The obtained DNA ladder in Fig. 3B might indicate the effect of NB-UVB that induced HaCaT cell death by apoptosis. It seemed that pretreatment of DSE provided less DNA ladder than that of posttreatment which indicated the partial DNA prevention effect of DSE because the DNA fragments were still presented. This might be from the moderate and mild potencies of free radical and superoxide anion scavenging properties of DSE, respectively, since antioxidants can neutralize ROS production, attenuate the induction of apoptosis, and prevent DNA damage [[8], [13], [16]].

According to the use of D. scandens as an anti-inflammatory drug, and its extract provided low potency of NB-UVB protection to HaCaT, the effect of DSE on gene expression in NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT was investigated. NB-UVB can induce skin inflammation, and the upregulation of genes involves inflammation and cascade effects. From our results, genes including the inflammatory enzymes iNOS and COX-2; proinflammatory cytokines IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6; collagen degradation MMP-1 and MMP-9; and carcinogenesis Bax were all upregulated after NB-UVB exposure (Fig. 5). Posttreatment with DSE, which reduced the expression of IL-1 (Fig. 5E–F) and IL-6 (Fig. 5G), might be beneficial to psoriasis phototherapy by NB-UVB since the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1 is related to psoriatic pathology and IL-6 is a key mediator in acute and chronic inflammation, which is highly expressed in psoriasis plaques but weakly expressed in the normal epidermis [30].

Chronic inflammation and chronic exposure to UVB could promote skin cancer. The upregulation of apoptotic biomarkers, especially the preapoptotic protein Bax, could induce apoptosis in skin cells [1]. COX-2 is also a target gene for UVB-induced carcinogenesis. COX-2 expression and prostaglandin PGE-2 production enhance tumor formation in the skin [46]. From our results, DSE showed downregulation of both Bax and COX-2 (Fig. 5B and H), indicating the potential for cancer prevention. In DSEs, the presence of lupalbigenin, an anticancer compound, might also be involved in this effect. Further experiments to explain the mechanism of action in detail will be conducted.

The gene downregulation of MMP-1 and MMP-9 of DSE also provided its potential ability to protect against NB-UVB-induced skin aging. This was in line with previous reports that UVB-irradiated keratinocytes overexpress matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) via ROS-mediated MAPK activation, which results in reduced collagen production and increased cleavage of extracellular matrix (ECM) components such as collagen and elastin [29]. MMPs play a role in collagen degradation in epidermal keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts. Thus, MMPs are one of the targets to prevent skin aging. MMP-1 (Type I collagenase) controls Type I collagen (80–90% of the skin), while MMP-9 (gelatinase-B) degrades gelatin. MMP-1, MMP-9, and MMP-10 are secreted by keratinocytes. MMP-1 causes fragments of collagen, which initiate matrix degradation and make it susceptible to further breakdown by MMP-9 [20,44].

The low potency of the iNOS gene downregulation effect of DSE in HaCaT cells (Fig. 5A) was accompanied by the moderate potency of nitric oxide reduction of DSE in RAW 264.7 cells. This suggested that DSE inhibited nitric oxide production by decreasing iNOS gene transcription, although the submaximal expression of the iNOS gene in keratinocytes might not be achieved because it needs 48 h after UVB exposure to reach the highest level [39]. These results also supported that inhibition of nitric oxide production was not the principal mechanism of action of DSE as anti-inflammation. Posttreatment of DSE was more effective to downregulate gene expressions than the pretreatment in NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT.

In summary, the downregulation of the gene in NB-UVB-exposed HaCaT cells by DSE provided feasibility for the topical use of this extract as an anti-inflammatory agent through the decreased expression of iNOS, COX-2, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6; an anti-aging agent through the reduced expression of MMP-1 and MMP-9; an anti-psoriasis agent through the reduced expression of IL-1 and IL-6; and cancer prevention via the inhibition of Bax, iNOS, and COX-2. Further experiments should be performed to support these findings.

5. Conclusions

DSE possessed moderate anti-inflammatory activity through NO inhibition in macrophage RAW264.7 cells, while its 2 main components (GTG and lupalbigenin) had mild to inactive effects. DSE also did not enhance cell proliferation. Therefore, it might be good to use for the treatment of NB-UVB-induced skin inflammation and keratinocyte hyperproliferation diseases such as psoriasis. The anti-inflammatory effect of DSE was not from antioxidant and antioxidative stress, but it might have resulted from multitarget inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL6, COX-2, and MMPs, such as MMP-1 and MMP-9. This finding suggested that DSE was ineffective when used as pre-NB-UVB irradiation since it provided no protective effects to HaCaT cells, but it might have potential use to reduce the inflammation of keratinocytes after NB-UVB irradiation. Although DSE exhibited mild antioxidant activity, the presence of lupalbigenin, an anticancer agent, and the downregulation effect on the genes COX-2, MMP-1, and MMP-9, which are targets of NB-UVB-induced skin cancer, could support the potential cancer prevention effect of DSE from chronic NB-UVB-induced inflammation. The decrease in MMP-1 and MMP-9 in DSE also indicated their possible use for skin antiaging. Furthermore, the inhibition of gene expression involved in psoriasis pathogenesis, IL-1, and IL-6, might benefit from phototherapy in psoriasis patients. Our results suggested the potential uses of DSE as a polyherbal topical product that combines herbal extract with antioxidants to neutralize NB-UVB-induced ROS. More mechanisms of action in detail and an improved extraction method of D. scandens stem to yield the extract with higher anti-inflammatory potency and UV protection should be investigated.

Author contributions

Sumrit Sukhonthasilakun: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Pramote Mahakunakorn: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision. Alisa Naladta: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing-review and editing. Katesaraporn Nuankaew: Investigation, Formal analysis. Somsak Nualkaew: Methodology, Writing-review and editing, Supervision. Chavi Yenjai: Formal analysis. Natsajee Nualkaew: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) for graduate student (Sukhonthasilakun S.) in the year 2017, grant number KKU16/2560.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Transdisciplinary University, Bangalore.

References

- 1.Ascenso A., Pedrosa T., Pinho S., Pinho F., Ferreira de Oliveira J.M.P., Marques H.C., et al. The effect of lycopene preexposure on UV-B-irradiated human keratinocytes. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/8214631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benchakanta S., Puttiwong S., Boontan N., Wichit M., Wapee S., Kansombud S. A comparison of efficacy and side effect of knee osteoarthritis treatments with crude Derris scandens and ibuprofen. J Thai Trad Alt Med. 2012;10:115–123. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buglewicz D.J., Mussallem J.T., Haskins A.H., Su C., Maesa J., Kato T.A. Cytotoxicity and mutagenicity of narrowband UVB to mammalian cells. Genes. 2020;11:646. doi: 10.3390/genes11060646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi C.P., Kim Y.I., Lee J.W., Lee M.H. The effect of narrowband ultraviolet B on the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1, transforming growth factor-ß1 and type I collagen in human skin fibroblasts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;32:180–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coelho M.M.V., Apetato M. The dark side of the light: phototherapy adverse effects. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Medical Sciences, Ministry of Public Health . The Agricultural Co-operative Federation of Thailand; Bangkok: 2016. Thai herbal Pharmacopoeia. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esen Salman K., Kivanç Altunay I., Salman A. The efficacy and safety of targeted narrowband UVB therapy: a retrospective cohort study. Turk J Med Sci. 2019;49:595–603. doi: 10.3906/sag-1810-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernando P.M., Piao M.J., Kang K.A., Ryu Y.S., Hewage S.R., Chae S.W., et al. Rosmarinic acid attenuates cell damage against UVB radiation-induced oxidative stress via enhancing antioxidant effects in human HaCaT cells. Biomol Ther. 2016;24:75–84. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2015.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heck D.E., Vetrano A.M., Mariano T.M., Laskin J.D. UVB light stimulates production of reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22432–22436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300048200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernández A.R., Vallejo B., Ruzgas T., Björklund S. The effect of UVB irradiation and oxidative stress on the skin barrier—a new method to evaluate sun protection factor based on electrical impedance spectroscopy. Sensors. 2019;19:2376. doi: 10.3390/s19102376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu Y., Ma Y., Wu S., Chen T., He Y., Sun J., et al. Protective effect of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside against ultraviolet B radiation-induced cell damage in human HaCaT keratinocytes. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:301. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ichihashi M., Ueda M., Buiyanto A., Bito T., Oka M., Fukunaga M., et al. UV-induced skin damage. Toxicology. 2003;189:21–39. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamshidi S., Beigrezaei S., Faraji H. A review of probable effects of antioxidants on DNA damage. Int J Pharm Phytopharmacol Res. 2018;8:72–79. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jutathis K., Pongkitwitoon P., Sritularak B., Tanaka H., Putalun W. Development of monoclonal antibody-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for quantitative quality control of Derris scandens (Roxb.) Benth. J Immunoassay Immunochem. 2019;4:407–418. doi: 10.1080/15321819.2019.1615942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katiyar S.K., Mantena S.K., Meeran S.M. Silymarin protects epidermal keratinocytes from ultraviolet radiation-induced apoptosis and DNA damage by nucleotide excision repair mechanism. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021410. http://doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khalil C., Shebaby W. UVB damage onset and progression 24 h post exposure in human-derived skin cells. Toxicol Rep. 2017;4:441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim M.K., Shin J.M., Eun H.C., Chung J.H. The role of p300 histone acetyltransferase in UV-induced histone modification and MMP-1 gene transcription. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klemola K., Pearson J., Seppa L. Evaluating the toxicity of reactive dyes and dyed fabric with the HaCaT cytotoxicity test. Autex Res J. 2007;7:217–223. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon K.R., Alam B., Park J.H., Kim T.H., Lee S.H. Attenuation of UVB-induced photo-aging by polyphenolic-rich Spatholobus suberectus stem extract via modulation of MAPK/AP-1/MMPs signaling in human keratinocytes. Nutrients. 2019;11:1341. doi: 10.3390/nu11061341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laupattarakaeem P., Houghton P.J., Hoult J.R.S., Itharat A. An evaluation of the activity related to inflammation of four plants used in Thailand to treat arthritis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;85:207–215. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laupattarakasem P., Houghton P.J., Hoult J.R.S. Anti-inflammatory isoflavonoids from the stems of Derris scandens. Planta Med. 2004;70:496–501. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-827147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahabusarakam W., Deachathai S., Phongpaichit S., Jansakul C., Talor W.C. A benzyl and isoflavone derivatives from Derris scandens Benth. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:1185–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore J.O., Wang Y., Stebbins W.G., Gao D., Zhou X., Phelps R., et al. Photoprotective effect of isoflavone genistein on ultraviolet B-induced pyrimidine dimer formation and PCNA expression in human reconstituted skin and its implications in dermatology and prevention of cutaneous carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1627–1635. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myers E., Kheradmand S., Miller R. An update on narrowband ultraviolet B therapy for the treatment of skin diseases. Cureus. 2021;13 doi: 10.7759/cureus.19182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oh J.H., Lee J.I., Karadeniz F., Park S.Y., Seo Y., Kong C.S. Antiphotoaging effects of 3,5-dicaffeoyl-epi-quinic acid via inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases in UVB-irradiated human keratinocytes. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/8949272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohta Y., Katayama I., Funato T., Yokozeki H., Nishiyama S., Hirano T., et al. In situ expression of messenger RNA of interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 in psoriasis: interleukin-6 involved in formation of psoriatic lesions. Arch Dermatol Res. 1991;283:351–356. doi: 10.1007/BF00371814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park Y.K., Jang B.C. UVB-induced anti-survival and pro-apoptotic effects on HaCaT human keratinocytes via caspase- and PKC-dependent downregulation of PKB, HIAP-1, Mcl-1, XIAP and ER stress. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33:695–702. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parlak N., Kundarkci N., Parlak A., Akay B.N. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy starting and incremental dose in patients with psoriasis: comparison of percentage dose and fixed dose protocols. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2015;31:90–97. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parrish J.A., Jaenicke K.F. Action spectrum for phototherapy of psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 1981;76:359–362. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12520022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rittié L., Fisher G.J. Review UV-light-induced signal cascades and skin aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2002;1:705–720. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(02)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rukachaisirikul V., Sukpondma Y., Jansakul C., Taylor W.C. Isoflavone glycoside from Derris scandens. Phytochemistry. 2002;60:827–834. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00163-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sangmalee S., Laorpaksa A., Sritularak B., Sukrong S. Bioassay-guided isolation of two flavonoids from Derris scandens with topoisomerase II poison activity. Biol Pharm Bull. 2016;39:631–635. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b15-00767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Souza C., Mônico D.A., Tedesco A.C. Implications of dichlorofluorescein photoinstability for detection of UVA-induced oxidative stress in fibroblasts and keratinocyte cells. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2020;19:40–48. doi: 10.1039/c9pp00415g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seo S.J., Choi H.G., Chung H.J., Hong C.K. Time course of expression of mRNA of inducible nitric oxide synthase and generation of nitric oxide by ultraviolet B in keratinocyte cell lines. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:655–662. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen Y., Zhang H., Cheng L., Wang L., Qian H., Qi X. In vitro and in vivo antioxidation activity of polyphenols extracted from black highland barley. Food Chem. 2016;194:1003–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh R.K., Lee K.M., Jose M.V., Nakamura M., Ucmak D., Farahnik B., et al. The patient's guide to psoriasis treatment. part 1: UVB phototherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:307–313. doi: 10.1007/s13555-016-0129-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Srimongkol Y., Warachit P., Chavalittumrong P., Sriwanthana B., Pairour R., Inthep C. A study of efficacy of Derris scvandens (Roxb.) Benth. extract compared with diclofenac for the alleviation of low back pain. J Thai Trad Alt Med. 2007;5:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sriwanthana B., Chavalitumrong P. In vitro effect of Derris scandens on normal lymphocyte proliferation and its activities on natural killer cells in normals and HIV-1 infected patients. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;76:125–129. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tandara A.A., Mustoe T.A. MMP- and TIMP-secretion by human cutaneous keratinocytes and fibroblasts – impact of coculture and hydration. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2011;64:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tedasen A., Sukrong S., Sritularak B., Srisawat T., Graidist P. 5,7,4′-Trihydroxy-6,8-diprenylisoflavone and lupalbigenin, active components of Derris scandens, induce cell death on breast cancer cell lines. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;81:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Udayan B. UV induced skin inflammation and cancer, where is the link? Int J Curr Adv Res. 2017;6:8454–8463. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilhelm K.P., Samblebe M., Siegers C.P. Quantitative in vitro assessment of N-alkyl sulphate-induced cytotoxicity in human keratinocytes (HaCaT). Comparison with in vivo human irritation. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:18–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb06876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]