Abstract

Anabolic Androgenic steroids (AAS) are abused and reports have been made on their deleterious effects on various organs. It is imperative to report the mechanism of inducing oxidative tissue damage even in the presence of an intracellular antioxidant system by the interaction between lipid peroxidation and the antioxidant system in the kidney. Twenty (20) adult male Wistar rats used were grouped into: A- Control, BOlive oil vehicle, C- 120 mg/kg of AAS orally for three weeks, and D- 7 days withdrawal group following 120 mg/kg/ 21days of AAS intake. Serum was assayed for lipid peroxidation marker Malondialdehyde (MDA) and antioxidant enzyme –superoxide Dismutase (SOD). Sectioned of kidneys were stained to see the renal tissue, mucin granules, and basement membrane. AAS-induced oxidative tissue damage, in the presence of an endogenous antioxidant, is characterized by increased lipid peroxidation and decreased SOD level which resulted in the loss of renal tissue cells membrane integrity which is a characteristic of the pathophysiology of nephron toxicity induced by a toxic compound. However, this was progressively reversed by a period of discontinuation of AAS drug exposure.

Keywords: Anabolic Androgenic Steroid, Antioxidant, Nephrotoxicity, Lipid peroxidation, Oxidative stress, Basement membrane

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Anabolic Androgenic steroid (AAS) was administered orally at 120 mg/kg.

-

•

The Laboratory animals were kept in standard laboratory conditions according to approved ethical guidelines.

-

•

Serum was aliquoted to assay for biomarkers for lipid peroxidation using malondialdehyde (MDA) and antioxidant enzyme SOD via spectrophotometric analysis.

-

•

A recovery was included to evaluate the possibility of self-regeneration of renal cortical cells due to the activity of endogenous antioxidants following discontinuation of AAS administration.

-

•

AAS caused disruption of renal cortical cells histology, this was due to AAS AAS-induced toxicity leading generation of reactive oxygen species that downregulated the endogenous antioxidant – SOD.

-

•

AAS withdrawal group, demonstrates progressive regeneration of distorted cells.

-

•

This was linked to positive interplay between renal cells and the endogenous antioxidants.

1. Introduction

Anabolic-androgenic steroids (AASs) can be described as a group of synthetic compounds similar to testosterone endogenously produced in the body [1]. AAS is often used by young individuals to build muscle tone or improve muscle growth for aesthetic purposes and athletes’ performance [2], [3]. Studies have reported potential side effects of AASs abuse or misuse in young individuals [4], [5], [6].

However, with these reports, the number of young adults using AAS has grown drastically over the last 10 years [7]. AAAs misuse is considered a public health issue [8] that requires urgent attention to increase public awareness of the toxicology reports on AAS abuse [2]. Of all the AASs derivatives of testosterone, Nandrolone Decanoate (ND), methandienone, and methenolol are the most commonly abused androgens [9]. There are several studies that have suggested and reported the toxicology of AAS linked to oxidative stress and tissue damage [10] through alteration in the activity of the mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes [11], leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) having damaging effects in the cells [12]. The production of lot of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can induce oxidative stress, leading to cell damage that can culminate in cell death and many degenerative diseases [12]. However, cells can produce endogenous antioxidant enzymes to scavenge ROS produced during oxidative stress, thereby ameliorating or reversing the damaging effects of ROS in vitro and delaying many events that contribute to cell death [4], [12].

In some cases, toxic agent induces the generation of ROS, which overwhelms the endogenously produced antioxidants leading to progressive cell death [13]. In the last decade, the use of anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS) has been the focus of research worldwide, because of the reports of its deleterious effects or adverse effects in a number of young adults population [5], [14], [15]. These studies have reported process through which AAS alters the activity of the mitochondrial respiratory systems resulting in oxidative tissue damage cascade reaction [16]. However, this damaging effects can be downregulated and reversed by upregulating the antioxidant enzymes [4]. For instance, Aly et al. [13] reported AAS mediated degeneration of testicular tissue associated with an elevation in malondialdehyde activity and a decrease in superoxide dismutase, which collaborates with Riezzo et al. [17]. report that chronic administration of AAS induce oxidative stress and tissue damage characterized by a notable increase in lipid peroxidation and a decrease in antioxidant enzymes activity. The kidney is extremely vulnerable to oxidative tissue damage stress due to its high metabolic activities [18], [19]. and presence of large number of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) as lipid compositions of the kidney [20]. Agarwal, [21] and Aparicio et al., [22] linked chronic kidney disease with oxidative stress.

Chronic ingestion of AAS can induce oxidative stress that targets the lipid components in the kidney leading to an increased lipid peroxidation and decreased antioxidant enzyme activity resulting in kidney damage [17], [23]. Emphatically, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and protein synthesis alteration are commonly described mechanisms associated with AAS-related tissue damage [4] which can be reversed by the antioxidant enzymes endogenously produced or exogenously administered [4]. Various studies have documented extensively how antioxidants averts oxidative tissue damage mediated by toxic compounds or drugs. However, there is a knowledge gap on the role of endogenously produced antioxidants in AAS nephrottoxicity. Hence SOD being a key enzyme that act, first in line of antioixidant defense because of its potential to convert highly reactive superoxide radical [24]. Most studies have documented modulatory roles of exogenous antioxidant on endogenous antioxidant generation in health and diseases [25]. It is important to mention that the body cells have the ability to synthesize many endogenous antioxidants, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and glutathione (GSH) [12], which helps to maintain cellular redox homeostasis during oxidative tissue damage in the absence of exogenous antioxidant[13]. Transmembrane mucin helps to provide structural support by forming glycoclayx layer for epithelial cell basement membrane [26], and they have been implicated in disease conditions. It is important to fill the knowledge gap on the possible role of endogenously release antioxidant first line enzyme -SOD, in AAS administration to demonstrate its potency to reverse AAS mediated nephrotoxicity. Also, changes in mucin granules associated with basement membrane integrity has not be reported while making a comparison of the interplay between endogenous antioxidants and generation of ROS during AAS intake and after discontinuation. Hence this study was designed to evaluate the interplay between the endogenous antioxidant enzyme- superoxide dismutase (SOD) in reversing AAS-induced renal disruption during AAS administration and following its withdrawal by users.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Experimental animals

The adults male Wistar rats ( Rattus norvegicus) of an average weight of 120 g, procured and bred in the Animal House of Anatomy Department in Bingham University Karu, Nigeria, were kept in well-aerated metallic cages and allowed to acclimatized for two weeks before experimentation. They were kept in standard laboratory conditions of room temperature 35.5–37 °C, the humidity of 60 − 65 %, 12h of light and dark cycles and feed with pelleted rat feed (Vital Feed, Nasarawa State Nigeria) and water ad libitum. The animal care and use procedures in the research were performed in accordance with the Ethics Committee of the National Research Centre and the recommendations of the National Institutes of Health’s Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [27].

2.2. Drug of study

The drug of study, Anabolic-Androgenic Steroid with the generic name Testosterone Undecanoate (Andriol Testocaps, N. V. Organon, Oss the Netherlands) was procured from Tonia Pharmaceutical Store Maitama Abuja, Nigeria. Each drug capsule contains 40 mg of Testosterone Undecanoate in addition to castor oil, propylene glycol laurate, glycerin, and gelatin. The study dose was taken to be 120 mg/kg bodyweight a dose below the study dose adopted by An and Kong (2022) [28]. study dose of 125 mg/kg. The drug was given orally using olive oil as a vehicle [29], [30] and this is reported to enhance drug bioavailability and increased the absorption rate for drugs such as Undecanoate used in this study which is a lipid-based formulations for oral delivery [30]. The drug was authenticated by the pharmacists by visual inspection of the drug label, confirming the appropriate formulations, expiration date, batch name scanned and authenticated using codes. The address of the manufacturer was also checked in the pharmacy and authenticated before purchase.

3. Experimental duration

The experiment was designed to run for four (4) weeks, i.e three (3) weeks AAS treatment and one (1) week of withdrawal from AAS administration. The rationale for the withdrawal group was to evaluate changes in the animal following discontinuation of AAS intake.

4. Experimental design

Experimental animals were divided into four [4] groups of five animals each (n = 5).

Group A: Control group normal saline 1 ml/day.

Group B: 1 ml of Olive Oil (vehicle for drug administration].

Group C: 120 mg/kg of AAS administered orally for 21 days [three weeks].

Group D: one-week discontinuation/recovery group following three weeks of oral administration of 120 mg/kg of AAS.

5. Euthanasia of experimental animal

The final body weight of experimental animals was taken 24 h after the last administration. The blood samples were taken via cardiac puncture then animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation. The renal tissues were excised and rapidly preserved in 10 % formol- saline ready for histological tissue processing and staining.

6. Renal tissue histological processing

Longitudinal sectioned renal tissues were processed according to histological processing procedures: dehydration in graded alcohol (ascending grades), clearing in three changes of xylene, infiltration in molten paraffin wax [31] using an automated tissue processor (LEICA LTP50). Tissues blocks were sectioned using a Rotatory microtome (LEICA) set at 5 µm thickness.

7. Histological and histochemical staining procedure

Histological staining was done using Haematoxylin and Eosin (H and E) stain according to procedure by Bancroft and Gamble and Memudu et al. methods [31], [32]. Histochemical staining was done to demonstrate mucin granules of the epithelial cells’ basement membrane (basal lamina) using Periodic acid Schiff (PAS) reaction (enzyme digestion method) according to procedure by Bancroft and Gamble [31] Stained tissues sections were mounted/ cover-slipped using DPX, ready for light microscopic analysis and photomicrography.

7.1. Blood sample collection and preservation

The blood sample was collected via cardiac puncture using a 5 ml syringe. The collected samples were kept in labeled EDTA bottles. The bottle samples were centrifuged at 5000 r.p.m for 10 min using Remi C24 refrigeration centrifuge (−4 °C). Serum samples were aliquoted in labeled sample bottles ready for spectrophotometric analysis for Superoxide dismutase and Malondialdehyde activity using commercial kits.

7.2. Estimation of lipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation was estimated according to the method of Memudu et al., (2020a). This assay is based upon the reaction of TBA with malondialdehyde (MDA) which is one of the aldehyde products of lipid peroxidation. Lipid peroxidation was assayed by measuring the level of malondialdehyde (MDA) by spectrophotometry. MDA levels were determined by measuring thiobarbituric acid-reactive species, producing a red-colored complex having a peak of absorbance at 532 nm (Memudu et al., 2020b).

7.3. Estimation of endogenous antioxidant enzyme SOD activity in the serum

SOD was estimated by the technique explained by Memudu et al. [31], [32], [33] The activity was expressed as unit/ mg protein.

7.4. Tissue photomicrography

Photomicrographs of sections of the renal cortices were obtained using a compound light microscope (Olympus Tokyo, Japan) connected to a digital microscopic camera (Amscope Inc., Irvine, CA, USA).

7.5. Statistical analysis

Data sets were analysed using statistical tool - GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., LA Jolla, CA). Student’s t-tests were used for all paired comparisons and one-way ANOVA was used for all multiple comparisons followed by the post hoc Tukey test. Statistics were significant when p-values were lower than 0.05 and significant effects are indicated by asterisks (*p < 0.05). Data were expressed as mean ± Standard deviation (SD).(Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Experimental design and Protocol for this study.

8. Results

8.1. AAS results in an increase in body weight

there was a significant increase in final body weights of AAS treated (C) when compared with the control and the vehicle (olive oli) group at P < 0.05. The withdrawal group (D) had a significant increase in final body weight as compared with groups A and B (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Graphical representation of the final body weight of adult male Wistar. Data expressed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D). Data (*) taken as significant statistically when p < 0.05. Legend: A= Control; B= Vehicle (Olive oil) C= 120 mg/kg Anabolic Androgenic Steroid (AAS) Treated and D= AAS Withdrawal Group.

8.2. Androgen Anabolic Steroid (AAS) induced elevation of lipid peroxidation activity

Malondialdehyde (MDA) is a biomaker for lipid peroxidation in a tissue undergoing oxidative tissue damage. An increase in MDA indicates an increase in the destruction of the lipid membrane of the cell by reactive oxygen species (ROS). In this study, lipid peroxidation marker, MDA increased significantly in rats treated with AAS (group C) as compared with the control and vehicle groups (A and B). However, the withdrawal group had significant decline when compared with the AAS treated group C. This means that upon withdrawal of AAS a pro-oxidant compound there was a decline in cellular lipid peroxidation metabolites such as MDA (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Graphical representation of the serum level of Malondialdehyde (MDA) a biomarker for lipid peroxidation in oxidative tissue damage in of adult male Wistar. Data expressed as mean ± S.D (standard deviation). Data (*) taken as significant statistically when p < 0.05. Legend: A= Control; B= Vehicle (Olive oil) C= 120 mg/kg Anabolic Androgenic Steroid (AAS) Treated and D= AAS Withdrawal Group.

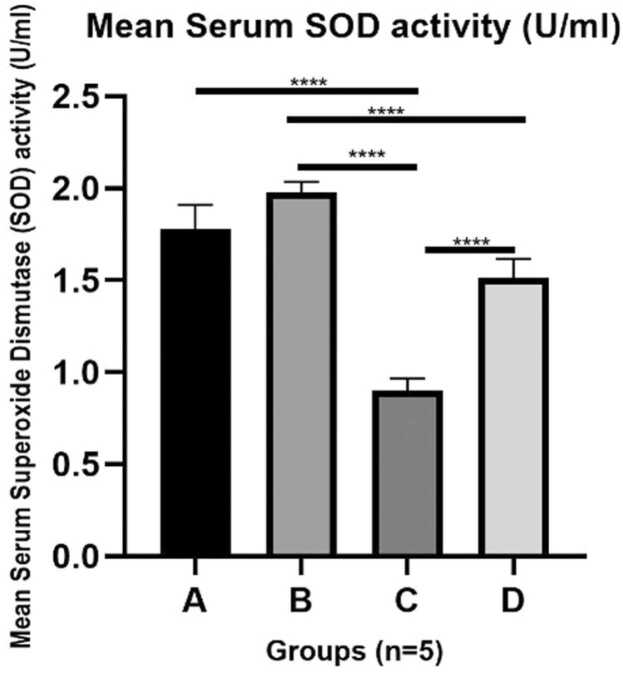

8.3. AAS mediates a declined in endogenous antioxidant status of Superoxide dismutase (SOD) which was upregulated upon withdrawal of AAS

Endogenous antioxidant enzymes are significant to attenuate/ reduce oxidative tissue damage in the presence of free radicals generated such as ROS. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is an endogenous antioxidant enzyme that generates superoxide anion as it mobs off ROS. In this study, AAS treated rats (group C) caused a statistically significant decline in SOD activity when compared with the control and vehicle groups (A and B). This indicates that ROS produced by AAS, overwhelmed endogenous SOD production resulting in a decline in endogenous production of SOD leading to the oxidative tissue damage in the renal tissue. However, the AAS withdrawal group demonstrated a mild increase in SOD level, when compared with group C (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Graphical representation of the Serum level of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), an endogenous antioxidant enzyme in adult male Wistar. Data expressed as mean ± S.D. Data (*) taken as significant statistically when p < 0.05. Legend: A = Control; B = Vehicle (Olive oil) C = 120 mg/kg Anabolic Androgenic Steroid (AAS) Treated and D = AAS Withdrawal Group.

8.4. AAS mediates disruption of the epithelial cell arrangement of the cells structures in the renal cortex

Histological appearance of the renal cortex was demonstrated using H and E stain. The control groups i.e the normal and vehicular control (A and B) have normal histoarchitectural arrangement characterized by well space renal tubules, normal squamous epithelial cell arrangement of the glomerulus, well-arranged basophilic cytoplasm of the cuboidal epithelial cells of the proximal convoluted tubules all showing the eosinophilic nucleus. However, the AAS treated renal cortex, is characterized by glomerular fragmentation, ruptured epithelial arrangement of the proximal convoluted tubules, presence of blood hemorrhage, vacuolar degeneration of the epithelial lining appearing like ground glass while the recovery/ withdrawal group was characterized by progressive regeneration of the glomerular and renal tubular epithelial framework, with the absence of degeneration like signs when compared with the AAS treated group (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Photomicrograph of a section of the longitudinal section of the kidney of adult male Wistar rats showing the renal cortex stained with H and E stain, Magnification is x40. Legend: A: Control, B: Olive Oil used as Vehicle, C- 120 mg/kg AAS, and D: 7 days withdrawal group after 21 days of oral AAS intake. Red circle; Glomerulus, Black arrows: Blood cells, green arrows: Disruption of the epithelial cell arrangement and ground-glass appearance of the epithelial cells. Groups A and B: show glomerulus and its epithelial cells undistorted, well-arranged epithelium of the proximal convoluted tubules showing their eosinophilic nucleus. C: the AAS treated renal cortex, is characterized by glomerular fragmentation, ruptured epithelial arrangement of the proximal convoluted tubules, and vacuolar degeneration of the epithelial lining appearing like ground glass. Group D: is characterized by regeneration of the glomerular and renal tubular epithelial framework, with the absence of degenerative-like signs when compared with group C.

8.5. AAS mediates disruption or dissolution of mucin granules results in loss of basement membrane integrity of the epithelial structures in the renal cortex

To demonstrate cell integrity of the basement epithelial membrane, PAS stain was used to demonstrate the thickness of the glomerular basement membrane associated with mucin granules in the basal lamina. The control and vehicle groups’ basement membranes were preserved when compared with the AAS treated group having loss of the basement membrane demonstrated in the disruption of epithelial cell arrangement in the glomerulus and renal tubules, these histopathological characteristics were diminished in the recovery/withdrawal group (Fig. 6). The disruption of the basal lamina of the basement membrane disrupt cell adhesion integrity in the epithelium of the renal cortex of the kidney tissue.

Fig. 6.

Photomicrograph of a section of the longitudinal section of the kidney of adult male Wistar rats showing the renal cortex stained with Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) reaction stain, Magnification is x40. Legend: A: Control, B: Olive Oil used as Vehicle, C- 120 mg/kg AAS, and D: 7 days withdrawal group after 21 days of oral AAS intake. Yellow circle; degranulation of Mucin granules and distorted basement membrane epitheliums, red arrows: diminished basement membrane blue arrows: preserved basement membrane (presence of mucin) lining. Groups A and B: have glomerulus and its epithelial cells undistorted, well-arranged epithelium of the proximal and distal convoluted tubules showing their eosinophilic nucleus. C: the AAS treated renal cortex, is characterized by glomerular fragmentation, ruptured / degeneration of the proximal and distal convoluted tubules with diminished mucin granules. Group D: is characterized by regeneration of the glomerular and renal tubular epithelial framework, with the presence of mucin granules in the basement membrane when compared with group C.

9. Discussion

Androgenic–anabolic steroids (AASs) or Anabolic steroids (also known as androgenic steroids) are synthetic derivatives of testosterone [34] used mainly for bodybuilding and aesthetics [35]. In this present study, 120 mg/kg of AAS given orally caused a significant increase in final body weight when compared with the control and the vehicle control, this correlates with report by Bento-Silva et al., (2010) that AASs induce body weight gain thereby supporting its use in aesthethic and body building [35] However, there are conflicting reports on AAS and body weight gain. This is associated with variation in drug dose and duration of administration. Alrabadi et al. [36], made a report that 100 mg/kg of AAS had a non-significant increase in body weight gain in male rats when compared with the control group. Our present study observed a slight decline in body weight of the withdrawal group when compared with the AAS-treated group., which correlated with report made by Abd El-Aziz El-Gendy et al. [37].

Studies have demonstrated that renal tissues are vulnerable to oxidative tissue damage because they have large number of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) [20] as well as extremely high metabolic functions resulting in excessive production of free radicals [19]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) released by kidney cells or by a toxic compound assault to the kidney can lead to renal tissue damage, which contributes to many nephro-degenerative diseases [38], [39], this explains why kidney is prone to chronic kidney disease associated with oxidative stress [21], [22].

This study demonstrates that exposure of the renal tissue to AAS caused an increase in lipid peroxidation biomarker MDA in the serum. An increased lipid peroxidation demonstrated by an elevated MDA is a biomarker for oxidative tissue damage [4], [23]. There was a surge in MDA level in AAS treated groups which implies that AAS induced oxidative renal damage targets the lipid chain in the kidney tissue [20] resulting in dissolution of the lipid components of the renal tissue [13]. This support reports made by Frankenfeld et al. [40] and Albano et al. [4] The continuous administration of AAS disrupts the endogenous antioxidant system that should have upregulated and mobs off the ROS mediating elevation MDA [4]. However, in this study the endogenous activity of SOD declined this correlates with reports made by Aly et al. [13] and Sadowska-Krępa et al. [23]. However, the recovery or withdrawal group showed a significant decline in MDA level when compared with the AAS-treated group but no significant difference with the control groups. This indicates that withdrawal of oxidative stress mediators can progressively reversed redox reactions in the renal tissue. Emphatically, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and protein synthesis alteration are commonly described mechanisms associated with AAS-related tissue damage [4], which can be reversed by the antioxidant enzymes endogenously produced or exogenously administered [4].

Human body cells are capable of producing many endogenous antioxidants defense systems, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), glutathione (GSH) [12], which helps to maintain cellular redox homeostasis during oxidative tissue damage in the absence of exogenous antioxidant [13]. The body is endowed with an enzymatic mechanism that minimizes damage induced by generated ROS during oxidative stress, this is carried out by antioxidant enzymes endogenously produced [39] thereby protecting tissues from damaging effects of ROS by either neutralizing or repairing oxidative damage [41]. In this study, the level of endogenous SOD was assayed, results obtained showed that SOD level declined significantly as compared with the control and vehicle group, indicating its use to scavenged generated ROS [39] associated with AAS induced renal oxidative tissue damage. This finding supports the reports that AAS has the potential to decline antioxidant enzymes such as SOD due continuous elevation of production of ROS that increases lipid peroxidation [42]. The withdrawal group had a significant increase in SOD activities as compared with the AAS treated group this is attributed to the gradual recovery of the renal cortical cells from AAS assault and production of more endogenous SOD aiding repairs and protection of cells from assault that will induced oxidative tissue damage [39].

Histopathological demonstration of the AAS treated renal cortex revealed distortion of the glomerular epithelial cells and cuboidal epithelial cells of the renal tubules with hemorrhage between the renal tubules similar to the report made by Brasil et al. [43] and Kahal and Allem [44]. In this study, AAS mediates oxidative stress leading to the generation of ROS that causes elevation of MDA and decline endogenous SOD thereby causing generated ROS to disrupt glomerular and renal tubules epithelial cells integrity characterized by loss of basement membrane/ basal lamina for the epithelial cell, which collaborates with Brasil et al. [43] and Ratliff et al. [45] reports on histopathological characterization observed in individual with AAS addiction or abuse. Androgen receptors (ARs) are expressed widely in human tissue most even in the kidney [4], AAS acts by binding onto them thereby increasing endogenous production of testosterone, elevation of testosterone production affect the glucocorticoid receptors, leading to inhibition of glucose synthesis and protein catabolism [4) leading to induced hypertrophy and distortion of renal tissue [43].

The recovery or withdrawal group demonstrates a progressive repair of the AAS mediated distortion of the glomerular cells and renal tubules epithelial cell via a decline in lipid peroxidation and upregulation of the endogenous antioxidant enzymes, hence gradual withdrawal of AAS ingestion can reverse AAS induced oxidative tissue damage [44] characterized by presence of mucin granules in the basement membrane of the glomerular and renal tubules epithelial cells in the renal cortex and absence of distortion of the epithelial cells as compared with the AAS treated group.

Hence, oxidative stress, apoptosis and inflammation play a significant role in renal tissue damage and in this context it is mediated by the drug AAS which has been reported to contribute to nephrotoxicity and morbidity [46]. Although the mechanism of AAS mediated nephrotoxicity is not totally understood, one may say it mediated by activation of ARs, oxidative stress [47] that is known to generate ROS that overwhelms endogenous antioxidant capacity [48] Therefore the interplay between AAS and endogenous antioxidant enzymes mediates upregulation or downregulation of oxidative tissue damage cascade reaction that culminates into nephrotoxicity or nephroregeneration [49], [50], [51], [52].

10. Conclusion

This study shows that AAS mediates the generation of reactive oxygen species leading to an increase in lipid peroxidation and depletion of endogenous antioxidant system in kidney tissue resulting in kidney damage, however, the discontinuation of AAS reverses improves the interplay between the tissue and production of endogenous antioxidant for tissue repairs and depletion of lipid peroxidation.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Authors solely funded this research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Conceptualization, A.E.M; methodology, A.E.M and G.D.A; software, validation, formal analysis: A.E.M; investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, A.E.M and G.D.A; writing—review and editing, A.E.M and G.D.A; visualization, A.E.M and G.D.A; supervision, A.E.M; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Handling Editor: Dr. L.H. Lash

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Roman M., Roman D.L., Ostafe V., Ciorsac A., Isvoran A. Computational assessment of pharmacokinetics and biological effects of some anabolic and androgen steroids. Pharm. Res. 2018;35(2):41. doi: 10.1007/s11095-018-2353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esposito M., Licciardello G., Privitera F., Iannuzzi S., Liberto A., Sessa F., Salerno M. Forensic post-mortem investigation in AAS abusers: investigative diagnostic protocol. A systematic review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11(8):1307. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11081307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mullen C., Whalley B.J., Schifano F., Baker J.S. Anabolic androgenic steroid abuse in the United Kingdom: an update. Br. J. Pharm. 2020;177(10):2180–2198. doi: 10.1111/bph.14995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albano G.D., Amico F., Cocimano G., Liberto A., Maglietta F., Esposito M., Rosi G.L., Di Nunno N., Salerno M., Montana A. Adverse effects of anabolic-androgenic steroids: a literature review. Healthcare. 2021;9:97. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9010097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjørnebekk A., Westlye L.T., Walhovd K.B., Jørstad M.L., Sundseth Ø.Ø., Fjell A.M. Cognitive performance and structural brain correlates in long-term anabolic-androgenic steroid exposed and nonexposed weightlifters. Neuropsychology. 2019;33:547. doi: 10.1037/neu0000537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanehkar F., Rashidy-Pour A., Vafaei A.A., Sameni H.R., Haghighi S., Miladi-Gorji H., et al. Voluntary exercise does not ameliorate spatial learning and memory deficits induced by chronic administration of nandrolone decanoate in rats. Horm. Behav. 2013;63(1):158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bueno A., Carvalho F.B., Gutierres J.M., Lhamas C., Andrade C.M. A comparative study of the effect of the dose and exposure duration of anabolic androgenic steroids on behavior, cholinergic regulation, and oxidative stress in rats. PLoS One. 2017;12(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahnema C.D., Crosnoe L.E., Kim E.D. Designer steroids - over-the-counter supplements and their androgenic component: review of an increasing problem. Andrology. 2015;3(2) doi: 10.1111/andr.307. 155-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patanè F.G., Liberto A., Maria Maglitto A.N., Malandrino P., Esposito M., Amico F., Cocimano G., Rosi G.L., Condorelli D., Nunno N.D., Montana A. Nandrolone decanoate: use, abuse and side effects. Medicina (Kaunas) 2020;11(56):11. doi: 10.3390/medicina56110606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerretani D., Neri M., Cantatore S., Ciallella C., Riezzo I., Turillazzi E., Fineschi V. Vol. 10. 2013. Looking for organ damages due to anabolic-androgenic steroids(AAS): is oxidative stress the culprit? pp. 393–399. (Mini Rev. Org. Chem). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arazi H., Mohammadjafari H., Asadi A. Use of anabolic androgenic steroids produces greater oxidative stress responses to resistance exercise in strength-trained men. Toxicol. Rep. 2017;4:282–286. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2017.05.005. (-) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poljsak B., Dušan Š., Irina M. Achieving the balance between ROS and antioxidants: when to use the synthetic antioxidants. oxidative medicine and cellular longevity. Artic. ID. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/956792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aly M.A., El-Shamarka El-Sayed, Soliman M., Elgabry, M.A T.N. Protective effect of nanoencapsulated curcumin against boldenone-induced testicular toxicity and oxidative stress in male albino rats. Egypt Pharm. J. 2021;20:72–81. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bento-Silva M., Carmo de Carvalho Martins, Francisco L., Torres-Leal T., Luiz B., Lara do N., Ferreira de Carvalho H., Aparecido, Carvalho F., de Castro Almeida R. Effects of administering testosterone undecanoate in rats subjected to physical exercise: effects on the estrous cycle, motor behavior and morphology of the liver and kidney. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010;46(1):79–89. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson B.S., Hildebrandt T., Wallisch P. Anabolic–androgenic steroid use is associated with psychopathy, risk-taking, anger, and physical problems. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:9133. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13048-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agriesti F., Tataranni T., Pacelli C., Scrima R., Laurenzana I., Ruggieri V., Cela O., Mazzoccoli C., Salerno M., Sessa F., Sani G., Pomara C., Capitanio N., Piccoli C. Nandrolone induces a stem cell-like phenotype in human hepatocarcinoma-derived cell line inhibiting mitochondrial respiratory activity. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:2287. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58871-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riezzo I., Turillazzi E., Bello S., Cantatore S., Cerretani D., Di Paolo M., Fiaschi A.I., Frati P., Neri M., Pedretti M., Fineschi V. Chronic nandrolone administration promotes oxidative stress, induction of pro-inflammatory cytokine and TNF-α mediated apoptosis in the kidneys of CD1 treated mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2014;280(1):97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perico N., Remuzzi G., Benigni A. Aging and the kidney. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2011:317–321. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328344c327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daenen K., Andries A., Mekahli D., Van Schepdael A., Jouret F., Bammens B. Oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease. Pedia Nephrol. 2019;34(6):975–991. doi: 10.1007/s00467-018-4005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozbek, E. 2012. Induction of Oxidative Stress in Kidney. International Journal of Nephrology.9 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Agarwal R. Chronic kidney disease is associated with oxidative stress independent of hypertension. Clin. Nephrol. 2004;61(6):377–383. doi: 10.5414/cnp61377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aparicio V.A., Camiletti-Moirón D., Tassi M., Nebot E., de-Teresa C., et al. Effects of anabolic androgenic steroids on renal morphology in rats. Arch Renal Dis. Manag. 2017;3(2):034–037. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadowska-Krępa E., Kłapcińska B., Nowara A., Jagsz S., Szołtysek-Bołdys I., Chalimoniuk M., Langfort J., Chrapusta S.J. High-dose testosterone supplementation disturbs liver pro-oxidant/antioxidant balance and function in adolescent male Wistar rats undergoing moderate-intensity endurance training. PeerJ. 2020;8 doi: 10.7717/peerj.10228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ighodaro O.M., Akinloye O.A. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alex. J. Med. 2018;54(4):287–293. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tung B.T., Rodríguez-Bies E., Ballesteros-Simarro M., Motilva V., Navas P., López-Lluch G. Modulation of endogenous antioxidant activity by resveratrol and exercise in mouse liver is age dependent. J. Gerontol.: Ser. A. 2014;69(4) doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt102. 398–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grondin J.A., Kwon Y.H., Far P.M., Haq S., Khan W.I. Mucins in intestinal mucosal defense and inflammation: learning from clinical and experimental studies. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:2054. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Institutes of Health’s Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Publication no. 19–60, revised 1985).

- 28.An J., Kong H. Comparative application of testosterone undecanoate and/or testosterone propionate in induction of benign prostatic hyperplasia in Wistar rats. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stuchlík M., Zák S. Lipid-based vehicle for oral drug delivery. biomedical papers of the medical faculty of the University Palacky. Olomouc, Czechoslov. 2001;145(2):17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandeep K., Mohanvarma M., Veerabhadhraswamy P. Oral lipid-based drug delivery systems – an overview. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2013;3(6):361–372. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bancroft, J.D., Gamble, M. 2009 Theory and practice of histological techniques, 6th edn. Churchill Livingstone, London.

- 32.Memudu A.E., Pantong S., Osahon I. Histomorphological evaluations on the frontal cortex extrapyramidal cell layer following administration of N-Acetyl cysteine in an aluminum-induced neurodegeneration rat model. Metab. Brain Dis. 2020;35:829–839. doi: 10.1007/s11011-020-00556-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Memudu A.E., Olarenwaju E., Osahon I.R., Oviosun A. Caffeinated energy drink induces oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation and mild distortion of cells in the renal cortex of adult wistar rats. Eur. J. Pharm. Med. Res. 2020;7(6):817–824. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lusetti, M., Licata, M., Silingardi, E., Bonsignore, A., Palmiere, C. 2018. Appearance/Image- and Performance-Enhancing Drug Users: A Forensic Approach. The American journal of forensic medicine and pathology. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Kotil T., Sevim Ç., Kara M. Evaluation of PTN and P13K/AKT expressions in stanozolol- treated rat kidney. J. Istanb. Fac. Med. 2022;85(1):59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alrabadi N., Al-Rabadi G.J., Maraqa R., et al. Androgen effect on body weight and behaviour of male and female rats: novel insight on the clinical value. Andrologia. 2020;52 doi: 10.1111/and.13730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abd El-Aziz El-Gendy M., Helmy El-Dabbah F., Ibrahim Hassan A., Abd El-Naby Awad N. Hepatotoxic and cardiotoxic effects of testosterone enanthate abuse on adult male albino rats. Al-Azhar Med. J. 2021;50(2):1335–1348. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsatsakis A., Docea A.O., Calina D., Tsarouhas K., Zamfira L.-M., Mitrut R., et al. A mechanistic and pathophysiological approach for stroke associated with drugs of abuse. J. Clin. Med. 2019;8:1295. doi: 10.3390/jcm8091295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharifi-Rad M., Anil Kumar N.V., Zucca P., Varoni E.M., Dini L., Panzarini E., Rajkovic J., Tsouh, Fokou P.V., Azzini E., Peluso I., Prakash Mishra A., Nigam M., El Rayess Y., Beyrouthy M.E., Polito L., Iriti M., Martins N., Martorell M., Docea A.O., Setzer W.N., Calina D., Cho W.C., Sharifi-Rad J. Lifestyle, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: back and forth in the pathophysiology of chronic diseases. Front. Physiol. 2020;11:694. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frankenfeld S.P., Oliveira L.P., Ortenzi V.H., Rego-Monteiro I.C., Chaves E.A., Ferreira A.C., Leitão A.C., Carvalho D.P., Fortunato R.S. The anabolic androgenic steroid nandrolone decanoate disrupts redox homeostasis in liver, heart and kidney of male Wistar rats. PLoS One. 2014;9(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lazzarino G., Listorti I., Bilotta G., Capozzolo T., Amorini A.M., Longo S., et al. Water- and fat-soluble antioxidants in human seminal plasma and serum of fertile males. Antioxidants. 2019;8:96. doi: 10.3390/antiox8040096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turillazzi E., Neri M., Cerretani D., Cantatore S., Frati P., Moltoni L., Busardò F.P., Pomara C., Riezzo I., Fineschi V. Lipid peroxidation and apoptotic response in rat brain areas induced by long-term administration of nandrolone: the mutual crosstalk between ROS and NF-kB. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2016;20:601–612. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brasil G.A., de Lima E.M., do Nascimento A.M., Caliman I.F., de Medeiros A.R., Silva M.S., de Abreu G.R., dos Reis A.M., de Andrade T.U., Bissoli N.S. Nandrolone decanoate induces cardiac and renal remodeling in female rats, without modification in physiological parameters: the role of ANP system. Life Sci. 2015;137:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kahal A., Allem R. Reversible effects of anabolic steroid abuse on cyto-architectures of the heart, kidneys and testis in adult male mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;106:917–922. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ratliff B.B., Abdulmahdi W., Pawar R., Wolin M.S. Oxidant mechanisms in renal injury and disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2016;25:119–146. doi: 10.1089/ars.2016.6665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Awdishu L., Mehta R.L. The 6R’s of drug induced nephrotoxicity. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):124. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0536-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khairnar S.I., Mahajan U.B., Patil K.R., et al. Disulfiram and its copper chelate attenuate cisplatin-induced acute nephrotoxicity in rats via reduction of oxidative stress and inflammation. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020;193(1):174–184. doi: 10.1007/s12011-019-01683-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Omolola R.O., Ademola A.O., Temidayo O.O., Ebunoluwa R.A., Adebowale B.S. Biochemical and electrocardiographic studies on the beneficial effects of gallic acid in cyclophosphamide-induced cardiorenal dysfunction. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2017;14(3) doi: 10.1515/jcim-2016-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bates G., Van Hout M.C., Teck J.T.W., McVeigh J. Treatments for people who use anabolic androgenic steroids: a scoping review. Harm Reduct. J. 2019;16:75. doi: 10.1186/s12954-019-0343-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pomara C., Neri M., Bello S., Fiore C., Riezzo I., Turillazzi E. Neurotoxicity by synthetic androgen steroids: Oxidative stress, apoptosis, and neuropathology: a review. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2015;13:132–145. doi: 10.2174/1570159X13666141210221434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sessa F., Salerno M., Bertozzi G., Cipolloni L., Messina G., Aromatario M., Polo L., Turillazzi E., Pomara C. miRNAs as novel biomarkers of chronic kidney injury in anabolic-androgenic steroid users: an experimental study. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11:1454. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.563756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Torrisi M., Pennisi G., Russo I., Amico F., Esposito M., Liberto A., Cocimano G., Salerno M., Li Rosi G., Di Nunno N., et al. Sudden cardiac death in anabolic-androgenic steroid users: a literature review. Medicina. 2020;56:587. doi: 10.3390/medicina56110587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.