Abstract

Tax pass-through rates to prices measure how much prices increase when taxes are increased by one unit, which will in turn determine the effectiveness of taxation policies in reducing substance use. Using longitudinal data of alcohol prices and excise taxes from 27 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries from 2003 to 2016, we estimate the tax pass-through rates to prices for a variety of alcoholic beverages – beer (1.24 ; 95% CIs: [0.67, 1.81]), wine ( 2.4; 95% CIs: [1.7, 3.11]), Cognac (1.71; 95% CIs: [1.07, 2.35]), Gin (0.85; 95% CIs: [0.34, 1.35]), Scotch whisky (1.14; 95% CIs: [0.52, 1.75]), and Liqueur Cointreau (1.98; 95% CIs: [1.21, 2.76]). While excise taxes on wine, Cognac, and Liqueur Cointreau are over-shifted to prices, taxes on Gin are exact- or under-shifted. Excise taxes on beer and Scotch whisky are likely over-shifted to prices, but the tax pass-through rates for these beverages are not significantly different from 1 and we cannot completely rule out exact pass-through of taxes to prices. The tax pass-through to prices for most beverage types is also higher for higher-priced products. Dynamic model further shows a lagged impact of wine and beer taxes on prices, indicating pricing strategies that may target lower-priced beer and wine.

Keywords: Alcoholic beverages, alcohol excise taxes, prices, tax pass-through rates

Introduction

Excessive drinking is a major cause of adverse health, economic, and behavior-related consequences [1]. Among all policies aimed at reducing excessive drinking and related harms, increasing taxes is the most effective intervention, and it is important to fully leverage its public health benefits [2-4]. In particular, how excise alcohol taxes are passed to prices (i.e., how much prices increase in response to per unit tax increase) and the price elasticity of demand for alcoholic beverages will determine the effectiveness of tax policies and thereby impact drinking behaviors.

Economic theories suggest that the degree to which taxes are passed to prices depends on supply and demand curves, shaped by the competition level of the market. In the classic example, the supply and demand sides share the tax increases and the less price-responsive side of the market bears greater tax burden. Under this scenario, the retail price increase is less than the tax increase, suggesting a tax pass-through rate that is less than one. In other scenarios, taxes may be over-shifted, exact-shifted, or under-shifted to prices [5-8]. For example, manufacturers may have incentives to raise prices at higher levels than the amount of tax hikes to compensate for profit and revenue loss, leading to a tax pass-through rate greater than one, as in the case of the cigarette market [9-13].

Alcohol and tobacco markets are often categorized as oligopolistic [11]. Therefore, the Cournot model of oligopoly behavior may better explain the pass-through rates of sin taxes (e.g., excise tobacco and alcohol taxes) to retail prices [14]. Under the assumptions that the price elasticity of demand and the market concentration do not depend on taxes, the tax pass-through rates are determined by the differences in the magnitude of the price elasticity of demand and the market concentration measure – the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) for oligopoly. In this framework, the tax pass-through rate is greater than one in a typical oligopoly market and approaches one as the market becomes more competitive.

Nonetheless, how taxes are passed through to prices is an empirical question that has been extensively studied in the form of tax pass-through rates to prices. In the sin tax literature, cigarette taxes are considered over-shifted to prices in an oligopoly tobacco market, supported by a series of empirical studies [15, 16]. Similar conclusions of over-shifted taxes have been found for alcoholic beverages, particularly beer, but the literature is less abundant and often limited to evidence from the US. One recent systematic review and meta-analysis of alcohol tax pass-through rates shows that beer taxes are over-shifted to prices, whereas taxes on other beverages are fully shifted to prices. However, this analysis cannot reject the full-shifting of alcohol taxes to prices, including beer [17].

Studies in this area of research further generate various estimates of tax pass-through rates. For example, Young and Bielínska-Kwapisz [8]analyze US quarterly data of alcohol taxes and prices from 1982 to 1997 and find that, in response to a $1 increase in taxes, the retail prices of alcohol increase by $1.05-$1.86 for beer, $1.64-$3.01 for spirits, and $1.24-$2.44 for wine. An evaluation of the 2002 tax hike in Alaska shows an over-shifting of alcohol taxes to prices, with an average pass-through rate of two (i.e., a $1 increase in taxes leads to a $2 increase in prices) for off-premise beer and spirits, and a rate of three to four for on premise beer and spirits [18]. Using alcohol price data compiled by the American Chamber of Commerce Research Association (ACCRA), one study estimates a nearly full tax pass-through rate of 0.94 for beer and an over-shifting pass-through rate of 1.56 for liquor [19]. Using state-level tax and price variation over time, one study illustrates that the beer tax pass-through rate to prices is 1.7 in the US.

Despite most evidence that shows alcohol taxes to be over-shifted to prices in the US, Siegel et al. [20] investigate the relationship between state liquor excise taxes and the retail prices of a variety of liquor products (bourbon, cognac, gin, etc.) in eight US states in 2012 and estimated a nearly full pass-through rate of 0.93. However, that study assessed only the correlation between taxes and prices, which may have resulted in biased estimates. Further, although the estimated pass-through rates of beer taxes to prices tend to be greater than one, it is not uncommon for a study to report a range of rates with a lower bound close to one, suggesting that a full pass-through of beer taxes cannot be completely ruled out.

Studies from countries other than the US also suggest that beer excise taxes may be over-shifted to prices. Bergman and Hansen [21] investigate the shifting of beer and liquor excise taxes in Denmark, where they show the tax pass-through rate to be between one and two. Interestingly, tax cuts on liquor – unlike tax increases – are under-shifted to prices, suggesting an asymmetric impact of tax changes on prices. Using monthly data from 2000 to 2011, Bakó and Berezvai [22] examine the Hungarian beer market and estimate a tax pass-through rate of 1.65. In South Africa, evidence suggests a pass-through rate of 4.83 for lager and 4.77 for all beer [11]. The over-shifting of alcohol taxes to prices is found across beer brands and packaging combinations, indicating that tax over-shifting occurs at all beer price levels in South Africa.

Global evidence further indicates that the tax pass-through rates of specific excise taxes to prices may differ from those of value-added taxes (VATs), and vary by price levels along the price distribution. In the French liquor market, while specific excise taxes are over-shifted to beer and aperitif prices, VATs are under-shifted [23]. The magnitude of UK excise duty and VAT pass-through rates also differ by price levels along the price distribution of beer, wine, and spirits. Specifically, for the cheapest 15% of products, taxes are under-shifted to prices, whereas for median prices and above, taxes are over-shifted to prices [24]. Moreover, the under-shifting of taxes to prices at the lowest 15% of the price distribution is more pronounced for beer and spirits than for wine, with a pass-through rate of 0.85-0.86 for beer and spirits and a rate of 0.9 for wine.

One common limitation of these existing studies that utilize data from a single country or state is the lack of counterfactuals, which may lead to biased estimation of the tax pass-through rate to prices. For example, a pre- and post-comparison of prices in response to a tax change is often used to estimate tax pass-through rate, which identifies correlations rather than causations. Only one study uses a difference-in-difference (DD) method in a cross-country context (i.e., Two-way Fixed Effects model with time and country fixed effects) to identify the tax pass-through rates to prices. That study capitalizes on the variation of VAT rates, beer excise tax rates, and beer prices in all 28 European Union (EU) member states during 1996-2016, and showed that specific excise taxes are nearly fully shifted to beer prices [25].

In summary, the evidence on the pass-through rates of alcohol excise taxes to prices is scarce. Although a majority of studies suggest an over-shifting of excise taxes to alcohol prices, there are caveats such as a narrow focus on beer and the lack of empirical strategies to identify causal impacts. Further, the analyses often yield ambiguous conclusions on whether excise taxes are fully passed or over-shifted to prices, with many studies suggesting a lower bound of pass-through rate close to one. It is also less understood how taxes are passed to prices along the price distribution. In other words, when taxes increase by the same amount, it is unclear whether the price increase of less expensive products is less, equal, or greater than the price increase of their more expensive counterparts. The evidence on tax shifting along the price distribution may have important public health implications if manufacturers intentionally keep lower-priced products cheaper by passing forward less tax increase. As a result, more studies are needed to understand the differences in tax pass-through rates by alcoholic beverage types and price levels.

This study intends to fill this critical evidence gap by conducting a thorough investigation of pass-through rates of beer, wine, and liquor (Cognac, Scotch whisky, Gin, and Liqueur Cointreau) taxes to respective prices, with data collected from products of different qualities and sold in different stores to reflect the price distribution. Using longitudinal data of prices and taxes from 27 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries from 2003 to 2016, we employ multiple models of panel data to identify the tax pass-through rates to prices, after addressing several notable methodological limitations in prior studies.

Data and Variables

Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) city data

Alcohol prices are the outcome investigated in this study and the data are obtained from the “Worldwide Cost of Living Survey” conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). In order to construct the consumer price index for 140 major cities in the world, the EIU collects prices of more than 160 services and products including alcoholic beverages every six months (in June and December). Professional price collectors are sent to document prices from supermarkets and mid-priced stores (e.g., convenience stores, specialty stores when applicable) in 140 cities that are located in 92 countries. The EIU editorial team then evaluates the accuracy and consistency of these price data and generates the average price for each product and service annually, using the June and December data collections. Additionally, to ensure consistency over time and across geographical locations, prices of the same or similar brands are collected for each product. The annual average EIU prices from 1990 onward are made available to researchers. Given that EIU data contains the largest number of cities and countries for which price information is collected consistently, they are widely used in health research when a cross-country comparison is performed [26-28].

For alcoholic beverages, prices of one local brand beer, one top-quality beer, one common table wine, one fine-quality wine, and one superior-quality wine are collected from supermarkets and mid-priced stores in each city each year. As a result, a total of four price levels are reported annually for beer (local brand from supermarkets, local brand from mid-priced stores, top quality from supermarkets, and top quality from mid-priced stores), whereas six price levels are reported annually for wine (common table from supermarkets, common table from mid-priced stores, superior quality from supermarkets, superior quality from mid-priced stores, fine quality from supermarkets, and fine quality from mid-priced stores). The EIU also collects prices of liquor/spirits including Cognac (French VSOP), Gin (Gilbey’s or equivalent), and Scotch whisky six years old. For each of these products, one price level from supermarkets and one price level from mid-priced stores are reported for each city each year. In this study, we use EIU price data from 2003 to 2016, during which excise tax rates for beer, wine, and other liquors in OECD countries are also available.

Table 1 is an illustration of the 64 cities in 27 OECD countries where EIU data are collected. Although there are 34 OECD countries to date, the price data or the excise alcohol tax information are not always available for Mexico, Turkey, and Israel during the study period; therefore those countries are dropped from the analytical sample.

Table 1:

OECD countries and EIU city data mapping

| Continents | Country (city /cities) |

|---|---|

| Americas | United States of America (Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Honolulu, Houston, Lexington, Los Angeles, Miami, Minneapolis, New York, Pittsburgh, San Francisco, Washington DC); Canada (Calgary, Montreal, Vancouver ) |

| Asia | Japan (Osaka/Kobe, Tokyo) |

| Australia | Australia (Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Sydney, Perth ); New Zealand (Auckland, Wellington) |

| Europe | Austria (Vienna); Belgium (Brussels); Czech Republic (Prague); Denmark (Copenhagen); Finland (Helsinki); France (Paris, Lyon); Germany (Berlin, Dusseldorf, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Munich); Greece (Athens); Hungary (Budapest); Iceland (Reykjavik); Ireland (Dublin); Italy (Milan, Rome); Luxembourg (Luxembourg); Netherlands (Amsterdam); Norway (Oslo); Poland (Warsaw); Portugal (Lisbon); Slovak Republic (Bratislava); Spain (Barcelona, Madrid); Sweden (Stockholm); Switzerland (Geneva, Zurich); United Kingdom (London, Manchester) |

Note: Wine taxes were not available for Australia, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain and Switzerland. Liquor/spirit taxes were not available for Japan.

All alcoholic beverage prices are converted into real prices in constant 2010 US dollars using the consumer price index from the World Bank. The real prices are further scaled into standard units. Specifically, beer prices are scaled to prices per liter (approximately three 12-ounce cans); wine prices are scaled to prices per 750 ml bottle; and liquor prices are scaled to prices per 700 ml bottle to match the excise tax information on the same basis. Because EIU data report final retail prices, we calculate prices exclusive of VATs, which are retail prices divided by (1+VAT rate). Next, we ranked VAT-exclusive prices for each alcoholic beverage type to identify the high and low levels of prices, along with average prices.

Alcohol excise duties in OECD countries

The key explanatory variables – alcohol excise taxes – are obtained from the OECD tax database1, which periodically publishes Consumption Tax Trends reports that compile VATs and excise taxes of beer, wine, and other alcoholic beverages as of January 1 of the report year. Using this information, we obtain January 1 tax rates in years 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2012, 2014, and 2016. These reports also standardize tax bases across countries to make excise taxes comparable. For example, in Canada and the US, where provincial or state taxes also exist, tax rates are calculated as a weighted average of federal and local taxes (e.g., state or provincial taxes).

With regard to tax basis, beer excise taxes are reported on a basis of per hectoliter per % abv (percentage of pure alcohol by volume at 20°C); excise taxes of sparkling and still wine are reported on a basis of per hectoliter; and excise taxes of other alcoholic beverages are reported on a basis of per hectoliter of absolute alcohol. In order to match these tax rates with price data, we scaled beer taxes to rates per liter of 5% abv products; wine taxes to rates per 750 ml bottle; and liquor taxes to rates per 700 ml of 40% abv products. Because we cannot identify whether the wine products surveyed by the EIU data are sparkling or still, the average tax rates for sparkling and still wine are linked to EIU data for analyses. In addition, the reports also describe tax structures of beer and liquor with respect to alcohol strength and producer sizes, from which we construct dichotomous indicators for whether beer excise rates are progressive by strength, whether beer excise rates are lower for small producers, and whether liquor excise tax rates are lower for small distillers. These dichotomous indicators are taken as controls in the analyses.

Among the 27 OECD countries included in the analyses, beer tax information is available for all countries, but wine taxes are not applicable or available for Australia, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland; and liquor/spirit taxes were not available for Japan. Therefore, the analytical samples differ in sizes by alcoholic beverages.

Other country-level controls and data linkage

The country-level sociodemographic controls that we include in the data analyses are annual GDP per capita, the percent of population aged 15-64, and the percent of population aged 65 and over, obtained from the World Bank database.

Although we have alcohol prices at the city level, all explanatory variables are measured at the country level. Therefore, we aggregate city-level high, low, and average prices to country-level prices to facilitate a linkage among alcohol prices, taxes, and sociodemographic controls using country and year identifiers. Alcohol prices and taxes are further matched based on types. Specifically, beer prices are matched with beer excise taxes; wine prices are matched with wine taxes; and other alcohol prices are matched with liquor/spirit taxes. The final analytical sample size is 188 for beer analyses, 136 for wine analyses, and 180 for other liquor analyses (177 for Liqueur Cointreau; and 180 for the remaining liquor types).

Empirical Methodology

The systematic review by Nelson and Moran [17] provides a thorough summary of various analytical frameworks that guides the empirical approaches of this study. The analytical framework also draws from the Cournot model of oligopoly behavior that shows the tax pass-through rates as a function of price elasticity and HHI. Therefore, we first estimate fixed effects (FE) model as the benchmark framework, similar to the two-way fixed effects model used in Shrestha and Markowitz and in Ardalan and Kessing [12, 25]. The specification of the benchmark model can be described using the following equation:

where Pjt denotes alcohol prices in country j in year t; Taxjt indicates excise tax rates in country j in year t; and Xjt is a vector of time-varying country-level controls including GDP per capita, the percent of population aged 15-64, the percent of population aged 65 and over, and a linear form of the country-specific year trend that captures changes in country-specific unobservable factors (e.g., market concentration). When beer prices are taken as the outcomes, Xjt also includes dichotomous variables of whether beer excise taxes are progressive and whether beer rates are lower for small producers; and when liquor prices are outcomes, Xjt also includes a dichotomous variable of whether liquor excise rates are lower for small distillers. Yt and Γc denote year fixed effects and country fixed effects, respectively; and εijt is the error term. In other words, this benchmark model is essentially a panel fixed-effects model. Because we pool data from different countries, a flexible specification that controls for demographic variables, year and country fixed effects, and a linear country-specific year trend may be necessary to adjust for differences in price elasticity, market concentration (HHI), and other country-specific factors that influence tax pass-through rates to prices. Nonetheless, we also estimated less flexible specifications with and without demographic variables and country-specific year trends. For countries where we have data for beer market HHI from the Euromonitor data2, we conduct additional analyses to assess the effects of HHIs and the interaction between HHIs and taxes.

Further, because we have multiple price levels for each alcoholic beverage type, a total of 14 groups of regressions are analyzed, one for each of the following price outcomes: low beer price, average beer price, high beer price, low wine price, average wine price, high wine price, low Cognac price, high Cognac price, low Scotch whisky price, high Scotch whisky price, low gin price, high gin price, low Liqueur Cointreau price, and high Liqueur Cointreau price. Clustered standard errors are estimated by adjusting for inter-temporal correlations within each country.

In addition to the benchmark model, we also examine a dynamic model with one lead (t+2) and one lag (t−2) of excise taxes entered into the equation along with the contemporary (t) taxes. Due to a two- to three-year gap between the releases of tax data in OECD reports, t−2 and t+2 represent a two-year or more difference in the following equation:

As described in the review article by Nelson and Moran [17], the impacts of tax lags and leads are often tested in existing studies on tax pass-through rates [8, 11, 17, 21, 22, 25, 29]. The dynamic framework examines the lagging impacts of tax hikes on prices and the reactions in the market if tax increases are anticipated.

When two or more waves of data are available, another specification that is commonly used in the tax pass-through literature is to assess the impact of changes in taxes on changes in prices. This approach directly estimates the extent to which the price change responds to the tax change, regardless of whether it is a tax hike or cut. Therefore, the framework has the advantage of interpreting tax pass-through rates to prices intuitively and, as a first-difference (FD) panel technique alternative to the benchmark FE model, also provides a sensitivity analysis [11, 18, 25]. The FD regressions can be summarized using the following equation:

where the variables are identical to those in FE models, but are in the first difference form. In such a specification, time-invariant factors such as country fixed effects are dropped from the equation.

Throughout the analyses, we also conduct seemingly unrelated regressions (SUR) to simultaneously estimate equations for different price levels for each alcohol type respectively. SUR allows the error terms of maximum, average, and minimum price equations to be correlated, further allowing for a direct test of tax pass-through rates along the price distribution.

A series of sensitivity analyses and falsification tests are performed to examine the validity of these estimates. First, we re-conduct beer analyses after dropping Japan – the only Asian country – from the analytical sample in order to make countries more comparable in terms of alcohol market features and alcohol consumption cultures. Second, we include HHIs for beer markets in the beer regressions. Euromonitor reports have measures of beer manufacturers’ market shares for select countries, which were used to construct HHI indices for beer. However, these data are only available for a limited number of countries. Finally, we explore the state level alcohol tax variations in the US by conducting FE/benchmark analyses using city-level alcohol prices from all OECD countries. In this case, state-level excise and VAT taxes in the US are obtained from the Alcohol Policy Information System, standardized to comparable tax bases, and matched to EIU city-level prices using state and year identifiers. City-level prices from other countries remained matched to only country-level tax information. This set of regressions can be described using a modified version of Equation 1: Pijt = α1 + α2Taxjt + α3Xjt + Yt + Γc + εijt, where “ i” represents cities that are nested in countries, and Taxjtare in fact Taxijt for cities in the US.

Results

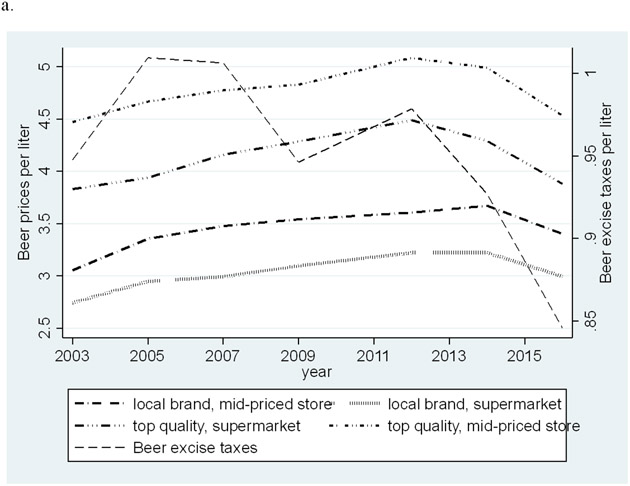

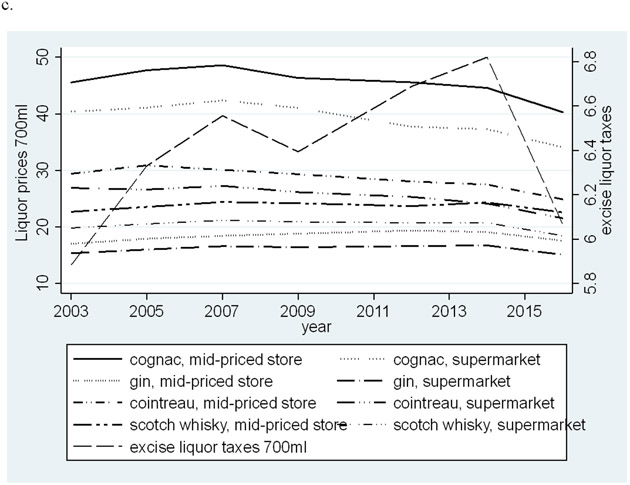

Figure 1 shows the trends in retail prices and excise taxes respectively for beer, wine, and other liquor during 2003-2016. Within each alcoholic beverage type, the price gaps between higher and lower qualities and between mid-priced stores and supermarkets remain stable over time. Beer and wine prices show corresponding trends to respective taxes. From 2003 to 2014, following the changes in taxes, the prices of both alcoholic beverages gradually increased, and then dropped from 2014 to 2016. Excise taxes fluctuate in a relative narrow range of $0.25-0.4 for both beer and wine, with increases in earlier years around 2005 and decreases since 2007. In contrast, although liquor taxes mostly increased from 2003 to 2014, the prices across all liquor subtypes gradually decreased during that period. Nonetheless, price trends in general respond to tax changes by adjusting accordingly in a two-year window.

Figure 1. Alcoholic beverage prices and excise taxes in 2010 US $, OECD country averages, 2003-2016.

Figure 1a. Beer price and excise taxes in 2010 US $, OECD country averages, 2003-2016

Figure 1b. Wine price and excise taxes in 2010 US $, OECD country averages, 2003-2016

Figure 1c. Liquor price and excise taxes in 2010 US $, OECD country averages, 2003-2016

Table 2 reports the summary statistics of the study samples (N=188 for beer, 136 for wine, 177 for Liqueur Cointreau, and 180 for other types). Higher-priced beer per liter (three 12-ounce cans) cost $4.45; average-priced beer cost $3.53; and lower-priced beer cost $2.75. The average beer excise taxes per liter are $0.88. For 74.5% of the sample, beer excise tax rates are progressive by strength, and for 39% of the sample, smaller producers enjoy lower beer excise tax rates. Higher-priced wine in a 750 ml bottle cost $53.03; average wine cost $24.19; and lower-priced wine cost $7.15. The average wine excise taxes per 750 ml bottle are $1.94. The high and low costs of a 700 ml liquor bottle are $44.85 and $38.32 for Cognac, $18.94 and $16.72 for Gin, $23.23 and $20 for Scotch whisky six years old, and $25.46 and $22.61 for Liqueur Cointreau. Liquor excise taxes for per 700 ml bottle of 40% abv products are $7.89. For 20% of the sample, lower liquor excise rates are imposed for small distillers.

Table 2:

Summary statistics of the analytical samples, by beverage types

| Variables | Mean/% | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Beer (N=188) | ||

| High beer price (l) | $4.45 | 2.37 |

| Average beer price (l) | $3.53 | 1.69 |

| Low beer price (l) | $2.75 | 1.29 |

| Beer excise tax (l) | $0.88 | 1.05 |

| Lower rates for small beer producers (%) | 39% | 0.49 |

| Excise beer taxes progressive by strength (%) | 74.5% | 0.44 |

| Panel B:Wine (N=136) | ||

| High wine price (750ml) | $53.03 | 19.03 |

| Average wine price (750ml) | $24.19 | 7.22 |

| Low wine price (750ml) | $7.15 | 3.29 |

| Average wine tax (750ml) | $1.94 | 2.33 |

| Panel C: Cognac (French VSOP) (N=180) | ||

| High cognac price (700ml) | $44.85 | 17.66 |

| Low cognac price (700ml) | $38.32 | 15.45 |

| Panel D: Gin (Gilbey’s or equivalent) (N=180) | ||

| High gin price (700ml) | $18.94 | 8.46 |

| Low gin price (700ml) | $16.72 | 8.01 |

| Panel E: Scotch Whisky 6 years old (N=180) | ||

| High scotch whisky price (700ml) | $23.23 | 9.90 |

| Low scotch whisky price (700ml) | $20 | 8.54 |

| Panel F: Liqueur Cointreau (N=177) | ||

| High liqueur Cointreau price (700ml) | $25.46 | 10.08 |

| Low liqueur Cointreau price (700ml) | $22.61 | 8.96 |

| All liquor panels (C-F): Liquor taxes (N=180) | ||

| Excise tax (700ml) | $7.89 | 6.46 |

| Lower tax rates for small distillers (%) | 20% | 0.4 |

| All panels: Demographics (N=188) | ||

| GDP per capita | $38,595 | 14,056 |

| Population aged 15-64 (%) | 66.82% | 2 |

| Population aged 65 and over (%) | 16.28% | 2.89 |

Note: Prices are measured in constant 2010 US dollars.

In Tables 3-6, we report the pass-through rates of taxes to prices for each beverage type, estimated using various models. Table 3 shows that for beer tax pass-through rates, results from most specifications are greater than one when high and average prices are taken as the outcome, and close to one when the low level of prices are taken as the outcome. This finding is robust to whether the specifications control for demographic variables or the linear country-specific year trend in dynamic and FD models. In FE models, taxes are under-shifted to all three levels of prices when the specifications do not control for the linear country-specific year trend and/or demographic covariates. However, the more flexible FE models with all covariates yield similar results to those of dynamic and FD models, which suggest that beer taxes are over-shifted to high and average prices and exact-shifted to low prices. The dynamic models further indicate that past beer excise taxes are negatively associated with the low level of prices in the current period. This finding may be interpreted as a marketing strategy where beer producers keep low-priced beer available in the market by absorbing past excise tax increases.

Table 3:

Pass-through rates of excise beer taxes to beer prices

| Prices | High | Average | Low | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| FE model – dependent variable: Price (t) (N=188) | |||||||||

| Tax (t) | 0.86** (0.25) |

0.76** (0.23) |

1.37*** (0.28) |

0.88*** (0.12) |

0.83*** (0.11) |

1.26*** (0.19) |

0.82*** (0.06) |

0.79*** (0.06) |

1.04*** (0.14) |

| Dynamic model – dependent variable: Price (t) (N=134) | |||||||||

| Tax (t) | 1.08+ (0.56) |

1.08+ (0.58) |

1.47* (0.55) |

1.10** (0.37) |

1.10** (0.37) |

1.25*** (0.38) |

1.13*** (0.25) |

1.13*** (0.25) |

1.17*** (0.19) |

| Past tax (t−2) | −0.02 (0.32) | −0.19 (0.41) | −0.72 (0.68) | −0.16 (0.19) | −0.28 (0.25) | −0.68 (0.53) | −0.29+ (0.15) |

−0.40* (0.19) |

−1.02** (0.34) |

| Future tax (t+2) | 0.28 (0.48) | 0.13 (0.45) | −0.12 (0.62) | 0.08 (0.30) | −0.01 (0.29) | −0.1 (0.51) | −0.18 (0.19) | −0.25 (0.19) | −0.57 (0.3) |

| FD model – dependent variable: Δ Price (t- t−2) (N=161) | |||||||||

| Δ tax (t-t−2) | 1.19*** (0.31) |

1.18*** (0.31) |

1.33*** (0.36) |

1.11*** (0.20) |

1.10*** (0.21) |

1.21*** (0.24) |

0.99*** (0.16) |

0.98*** (0.17) |

1.04*** (0.2) |

| Demographics | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Linear country-year trend | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

Note:

p<0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001. Standard errors clustered at the country level are in parentheses. FE and dynamic regressions control for year fixed effects, country fixed effects, and whether beer taxes are lower for small producers and whether beer taxes are progressive by strength. Demographic controls are GDP per capita, the percent of population aged 15-64, and the percent of population aged 65 and over. FD models control for the first differences of these covariates.

Table 6:

Pass-through rates of excise liquor taxes to Scotch Whisky and Liqueur Cointreau prices

| Prices | High Scotch | Low Scotch | High Liqueur | Low Liqueur | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

| FE model – dependent variable: Price (t) (N Scotch=180; N Liqueur=177) | ||||||||||||

| Tax (t) | 0.09 (0.31) | 0.18 (0.28) | 1.15*** (0.27) |

−0.06 (0.4) | 0.03 (0.37) | 0.93** (0.3) |

1.78*** (0.36) |

1.79*** (0.34) |

1.92*** (0.33) |

1.96*** (0.32) |

1.97*** (0.28) |

2.02*** (0.29) |

| Dynamic model – dependent variable: Price (t) (N Scotch=128; N Liqueur=126) | ||||||||||||

| Tax (t) | 0.81*** (0.22) |

0.87*** (0.23) |

1.33*** (0.42) |

0.49** (0.16) |

0.51** (0.33) |

1** (0.36) |

1.97*** (0.45) |

2.02*** (0.46) |

1.88*** (0.55) |

1.48*** (0.25) |

1.57*** (0.3) |

2.49*** (0.51) |

| Past tax (t−2) | 0.16 (0.19) | 0.20 (0.15) | 0.34*** (0.08) |

0.37 (0.2) | 0.39+ (0.2) |

0.54*** (0.11) |

0.02 (0.30) | 0.01 (0.32) | 0.22 (0.36) | 0.97* (0.43) |

0.92* (0.38) |

1.55* (0.75) |

| Future tax (t+2) | −1.26*** (0.25) |

−1.19*** (0.23) |

−0.61 (0.55) | −1.11** (0.32) |

−1.1** (0.31) |

−0.66 (0.53) | −0.88** (0.27) |

−0.88** (0.26) |

−0.36 (0.33) | −0.61*** (0.14) |

−0.62*** (0.16) |

−0.2 (0.44) |

| FD model – dependent variable: Δ Price (t- t−2) (N Scotch=154; N Liqueur=151) | ||||||||||||

| Δ tax (t-t−2) | 1.03*** (0.22) |

1.05*** (0.2) |

1.35*** (0.2) |

0.75* (0.3) |

0.78** (0.27) |

1.06*** (0.24) |

1.95*** (0.34) |

1.94*** (0.34) |

1.92*** (0.35) |

1.82*** (0.24) |

1.8*** (0.25) |

1.67*** (0.23) |

| Demographics | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Linear country-year trend | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

Note:

p<0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001. Standard errors clustered at the country level are in parentheses. FE and dynamic regressions controlled for year fixed effects, country fixed effects, and whether excise liquor tax rates are lower for small distillers. Demographic controls are GDP per capita, the percent of population aged 15-64, and the percent of population aged 65 and over. FD models control for the first differences of these covariates.

Table 4 shows that for wine tax pass-through rates, results from most specifications are greater than one, indicating that wine excise taxes are over-shifted to prices. This finding is robust to whether the specifications control for demographic variables or the linear country-specific year trend in FE, dynamic, and FD models. Similar to beer results, the dynamic models indicate that past wine excise taxes are negatively associated with the low level of prices in the current period. This finding may be interpreted as a marketing strategy where wine producers keep low-priced wine available in the market by absorbing past excise tax increases.

Table 4:

Pass-through rates of excise wine taxes to wine prices

| Prices | High | Average | Low | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| FE model – dependent variable: Price (t) (N=136) | |||||||||

| Tax (t) | 1.67** (0.44) |

2.38** (0.75) |

3.25*** (0.48) |

1.74*** (0.12) |

2*** (0.25) |

2.47*** (0.19) |

1.30*** (0.06) |

1.39*** (0.81) |

1.4*** (0.06) |

| Dynamic model – dependent variable: Price (t) (N=94) | |||||||||

| Tax (t) | 2.26** (0.75) |

2.56** (0.78) |

3.76*** (0.95) |

2.12*** (0.26) |

2.23*** (0.31) |

2.64*** (0.37) |

1.43*** (0.11) |

1.44*** (0.08) |

1.41*** (0.11) |

| Past tax (t−2) | −1.28 (1.10) | −0.65 (1.21) | −0.43 (1.43) | −0.8* (0.34) |

−0.53 (0.42) | −0.24 (0.51) | −0.43*** (0.09) |

−0.37* (0.14) |

−0.44* (0.2) |

| Future tax (t+2) | 0.17 (1.76) | 0.86 (1.81) | −0.58 (1.54) | 0.07 (0.47) | 0.28 (0.44) | 0.011 (0.54) | 0.07 (0.1) | 0.07 (0.13) | 0.05 (0.14) |

| FD model – dependent variable: Δ Price (t- t−2) (N=114) | |||||||||

| Δ tax (t-t−2) | 2.73*** (0.57) |

2.9*** (0.56) |

2.98*** (0.58) |

2.18*** (0.23) |

2.27*** (0.23) |

2.3*** (0.25) |

1.39*** (0.05) |

1.42*** (0.05) |

1.41*** (0.06) |

| Demographics | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Linear country-year trend | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

Note:

p<0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001. Standard errors clustered at the country level are in parentheses. FE and dynamic regressions control for year fixed effects and country fixed effects. Demographic controls are GDP per capita, the percent of population aged 15-64, and the percent of population aged 65 and over. FD models control for the first differences of these covariates. Wine excise taxes are the average of tax rates for sparkling wine and the rates for still wine.

Tables 5 and 6 present the results for Cognac, Gin, Scotch whisky, and Liqueur Cointreau. For Cognac, results from models with demographic controls and a linear country-specific year trend suggest that liquor excise taxes are over-shifted to Cognac prices. This finding for high Cognac price is further robust to other less flexible specifications when dynamic and FD models are estimated. For Gin, most results suggest that liquor excise taxes are under-shifted to Gin prices and this finding is robust to various models and specifications. For Scotch whisky, the estimates of liquor tax pass-through rates are somewhat sensitive to the specifications. When the linear country-specific year trend and demographic variables are controlled for, liquor taxes are over-shifted to high Scotch whisky prices and exact-shifted to low Scotch whisky prices, whereas in other specifications, liquor taxes are under- or exact- shifted to high Scotch whisky prices and under-shifted to low Scotch whisky prices. For Liqueur Cointreau, liquor excise taxes are over-shifted to prices – a finding that is robust to various models and specifications. The dynamic models further illustrate that past liquor excise taxes tend to be positively associated with current liquor prices, whereas future liquor taxes tend to be negatively associated with current liquor prices. This finding indicates that the short-run tax pass-through rates for liquors may be different from the long-run ones.

Table 5:

Pass-through rates of excise liquor taxes to Cognac and Gin prices

| Prices | High Cognac | Low Cognac | High Gin | Low Gin | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

| FE model – dependent variable: Price (t) (N=180) | ||||||||||||

| Tax (t) | 0.35 (0.37) | 0.56 (0.36) | 1.92*** (0.26) |

−0.16 (0.43) | 0.03 (0.39) | 1.45*** (0.28) |

−0.17 (0.29) | −0.12 (0.26) | 0.71*** (0.19) |

−0.15 (0.3) | −0.1 (0.27) | 0.82*** (0.22) |

| Dynamic model – dependent variable: Price (t) (N=128) | ||||||||||||

| Tax (t) | 1.35*** (0.31) |

1.54*** (0.36) |

2.17*** (0.41) |

0.35 (0.28) | 0.5 (0.33) | 1.36*** (0.31) |

0.26+ (0.14) |

0.27+ (0.14) |

0.91* (0.35) |

0.36** (0.10) |

0.35** (0.1) |

0.91* (0.43) |

| Past tax (t−2) | −0.11 (0.41) | −0.02 (0.35) | 0.25 (0.38) | 0.8+ (0.39) |

0.86* (0.37) |

1.23** (0.43) |

0.13 (0.22) | −0.14 (0.21) | 0.43*** (0.08) |

0.21 (0.13) | 0.21 (0.13) | 0.43*** (0.11) |

| Future tax (t+2) | −1.56*** (0.4) |

−1.42*** (0.33) |

−0.56 (0.75) | −1.71*** (0.3) |

−1.62*** (0.29) |

−0.49 (0.31) | −0.99** (0.29) |

−0.98** (0.28) |

−0.4 (0.44) | −1.08*** (0.26) |

−1.09*** (0.26) |

−0.56 (0.56) |

| FD model – dependent variable: Δ Price (t- t−2) (N=154) | ||||||||||||

| Δ tax (t-t−2) | 1.7*** (0.24) |

1.73*** (0.24) |

2.17*** (0.22) |

0.84+ (0.44) |

0.89* (0.39) |

1.21** (0.40) |

0.56** (0.2) |

0.57** (0.18) |

0.79*** (0.16) |

0.65** (0.19) |

0.67** (0.17) |

0.92*** (0.13) |

| Demographics | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Linear country-year trend | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

Note:

p<0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001. Standard errors clustered at the country level are in parentheses. FE and dynamic regressions control for year fixed effects, country fixed effects, and whether excise liquor tax rates are lower for small distillers. Demographic controls are GDP per capita, the percent of population aged 15-64, and the percent of population aged 65 and over. FD models control for the first differences of these covariates.

In Table 7, we summarize the results from the preferred specification with controls of demographic variables and the linear country-specific year trend. For each beverage type, we report the number of tax pass-through estimates and the range, mean, and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) of these point estimates. Although beer excise taxes are on average over-shifted to beer prices at a rate of 1.24(95% CIs: [0.67, 1.81]), this rate is not significantly different from 1. As a result, we cannot rule out the scenario that beer taxes are exact-shifted to beer prices. On average, wine excise taxes are over-shifted to wine prices at a rate of 2.4 (95% CIs: [1.7, 3.11]). Liquor excise taxes are over-shifted to Cognac prices at a rate of 1.71 (95% CIs: [1.07, 2.35]), and to Liqueur Cointreau prices at a rate of 1.98 (95% CIs: [1.21, 2.76]). In addition, liquor excise taxes are under-shifted to Gin prices at a rate of 0.85 (95% CIs: [0.34, 1.35]), and over-shifted to Scotch whisky prices at a rate of 1.14 (95% CIs: [0.52, 1.75]). However, these tax-through rates are not significantly different from 1. We further use the alternative criteria proposed by Bergman and Hansen [21] to categorize under-shifting (<0.9), exact pass-through (0.9-1.1), and over-shifting (>1.1) of taxes to prices. The conclusions are similar to those from examining the mean of point estimates and its 95% CIs.

Table 7:

Summary of results and the categorization of tax pass-through rates to prices

| Alcoholic Beverage | # of estimates | Range | Mean | Average 95% CI | Under-shifting (< 0.9) (#/%) |

Exact pass- through (0.9-1.1) (#/%) |

Over-shifting (>1.1) (#/%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beer | 9 | 1.04-1.47 | 1.24 | [0.67-1.81] | 0 | 2/22% | 7/78% |

| Wine | 9 | 1.40-3.76 | 2.4 | [1.70, 3.11] | 0 | 0 | 9/100% |

| Cognac | 6 | 1.21-2.17 | 1.71 | [1.07, 2.35] | 0 | 0 | 6/100% |

| Gin | 6 | 0.71-0.92 | 0.85 | [0.34, 1.35] | 3 / 50% | 3 /50% | 0 |

| Scotch Whisky | 6 | 0.93-1.35 | 1.14 | [0.52, 1.75] | 0 | 3 / 50% | 3/50% |

| Liqueur Cointreau | 6 | 1.67-2.49 | 1.98 | [1.21-2.76] | 0 | 0 | 6/100% |

Note: For each beverage type, results are pooled from FE, dynamic and FD models that examine different prices levels (high, low, and average prices for beer and wine and high and low prices for other liquors)

Next in Table 8, we show results of testing the difference in tax pass-through to high vs. low prices, based on SURs that simultaneously estimate the two price outcomes using the benchmark FE models. In general, tax pass-through to prices is higher for higher-priced products. Specifically, in response to a $1 increase in beer taxes, the price increase of higher-priced products is 33 cents higher than the increase of lower-priced products (p<0.01). Similarly, for wine the difference in price increase between high- and low-priced products is $1.85 (p<0.1). For other beverages, the difference in price increase is 47 cents for Cognac (p<0.05) and 22 cents for Scotch whisky (p<0.05), whereas the differences for Gin and Liqueur Cointreau are negative and insignificant.

Table 8:

Testing the differences in tax pass-through rates at different price levels using SUR

| Alcoholic Beverage | High | Low | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beer | 1.37 | 1.04 | 0.33** |

| Wine | 3.25 | 1.4 | 1.85+ |

| Cognac | 1.92 | 1.45 | 0.47 |

| Gin | 0.71 | 0.82 | −0.11 |

| Scotch Whisky | 1.15 | 0.93 | 0.22* |

| Liqueur Cointreau | 1.92 | 2.02 | −0.1 |

Note:

p < 0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001. Standard errors clustered at the country level are in parentheses. FE benchmark models are estimated using SUR and the differences among high, average (wine and beer), and low prices are tested. The tax pass-through to average wine or beer prices at the average level is not significantly different from those at the high or low levels.

Conclusions and discussion

Tax pass-through to prices and the sales response (i.e., the price elasticity of demand) together determine the effectiveness of excise taxes in reducing excessive drinking and promoting healthy behaviors. Therefore, how taxes are passed to prices is a critical step for sin taxes to effectively reduce risky behaviors and harmful health consequences. Empirical evidence in this area may further inform policymakers about the underlying market power of the supply and demand sides, tax burdens and revenues, and optimal taxes that are often debated in the policy arena [30-33]. Despite being a widely-used policy measure, increasing excise taxes on alcoholic beverages faces many challenges in achieving its public health goal. Evaluating the extent to which tax increases are passed to prices is a natural first step to assess the effectiveness of alcohol tax policies, in addition to the price elasticity of demand for alcohol which determines the effectiveness of alcohol tax policies.

Using longitudinal data of alcoholic beverage prices and taxes from 27 OECD countries from 2003 to 2016, we estimate the excise tax pass-through rates to prices for a variety of alcohol products. While excise taxes on wine, Cognac, and Liqueur Cointreau are over-shifted to respective prices, the excise tax pass-through rates for beer, Gin, and Scotch whisky are less conclusive. Specifically, excise taxes on beer and Scotch whisky may be over-shifted to prices, but we cannot completely rule out the scenario that these taxes are exact-shifted to respective prices. Excise taxes are on average under-shifted to Gin prices, but we cannot rule out the possibilities of exact-shifting. In summary, there is significant heterogeneity in tax pass-through to prices by beverage types and ambiguity in the pass-through rates for beer, Gin, and whisky. In regards to beer excise taxes, the findings are conferrable to the existing literature that in general suggests the over-shifting of taxes to beer prices. The results related to the ambiguity of the categorization of beer tax pass-through rates are also consistent with the conclusion made in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis [17]. That is, we cannot rule out the possibility that beer taxes are exact-shifted to prices.

Findings about wine and other liquor further contribute to the very sparse literature on how taxes are passed to the prices of alcoholic beverages other than beer, and corroborate some of the prior studies that also find these types of taxes over-shifted to prices. More importantly, our findings provide evidence on differential pass-through rates by different beverage types, which may explain why conclusions about tax pass-through to beverages other than beer in the existing literature tend to be inconsistent. Nonetheless, more research is needed to better evaluate the pass-through rates of various alcohol taxes to prices.

Another important contribution that this study offers is to evaluate how taxes are passed differently to various price levels along the price distribution. We find that, for most alcoholic beverages, the tax pass-through rates are higher for higher-priced products. This conclusion is to some extent similar to the findings in Ally et al. [24], who found that alcohol taxes are under-shifted to lower prices in the price distribution and over-shifted above the mean. Although the limited price points of EIU data prohibit us from capturing the full price distribution, we nonetheless find similar gaps in the tax pass-through rates between higher- and lower-priced products.

Following the guidance in the most recent systematic review, we further expand the analytical framework to include lags and leads of taxes in addition to current taxes to capture the dynamic structure of tax pass-through. Overall, manufacturers of beer and wine may adjust down the prices of lower-priced products in response to past tax hikes to keep these products affordable. These impacts were not found for their higher-priced counterparts. This evidence, together with the evidence on the lower tax pass-through rates for lower-priced products, indicates that the lower end of the price distribution may be the target of the alcohol industry in responding to taxes strategically. Such strategies also have been widely documented in the tobacco literature demonstrating the tobacco industry’s pricing strategy to keep lower-priced products affordable to consumers of lower socioeconomic status [16, 34-38].

Although over-shifting of taxes in general implies that consumers bear higher tax burdens than what the policies intend to impose, it does not necessarily lead to tax regressivity that disproportionately hurts consumers of lower socioeconomic status (SES). This is likely the case in a policy environment such as the US, where the alcohol taxes are not indexed to inflation and the real prices have been decreasing over time [4, 39, 40]. The US federal excise taxes on alcoholic beverages have not been increased since 1991 and a temporary lower tax rate has been in place since 2017 [17, 39]. The ultimate tax burdens on consumers (i.e., tax incidence), particularly those of low SES, need to be investigated with great caution.

In sensitivity analyses, we analyze a limited sample of countries for which the HHIs of beer markets can be measured. In these analyses, we test the Cournot model of oligopoly behavior by additionally controlling for beer market HHIs and the interaction term of HHIs and excise taxes. However, these HHI factors do not significantly impact prices (Appendix Table). Moreover, the estimates of beer tax pass-through rates are sensitive to the choices of models and specifications. Nonetheless, the average HHIs for beer are 0. 26, smaller than the absolute value of the existing price elasticity of beer demand, which is −0.46 [2]. These magnitudes suggest that beer taxes may be over-shifted to prices and could explain the greater than one beer tax pass-through rates found in this study and the existing literature. However, neither can the empirical evidence rule out exact- or under-shifting of beer taxes. Moreover, the results from sensitivity analyses are consistent with the literature showing that supply-side controls may not make a difference to the point estimates of tax pass-through rates [12, 20]. The recent review by Nelson and Moran [17] also lays out a framework without supply-side endogenous factors entered into the equations for estimating tax pass-through rates. All this evidence suggests that the lack of supply-side controls can be mitigated in the empirical work.

Finally, other sensitivity analyses by dropping Japan from the beer tax analyses and by testing these models using city-level instead of aggregated country-level data generally support the conclusions. Although city-level EIU price data reflect prices in urban areas and thus are not representative of average prices in a country, they nonetheless facilitate a comparison of prices among different countries that can be linked to the excise tax differences among these countries. Future analyses that match country-level prices and taxes more accurately are needed to address this limitation. In addition, the price levels reported in the EIU data do not fully reflect the price distribution in a country; future research that utilizes comparable retailer scanner data from different countries may be able to address this data limitation.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Xuening Wang for converting the original tax reports to excel data. We would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers, Jon Nelson, Le Wang, John Buckell and participants at the University of Oklahoma College of Arts and Sciences Research Seminar, the 2019 American Society of Health Economist conference, and the 2019 International Health Economics Association conference for constructive comments. Anh Ngo and Ce Shang are supported by a grant from NIH/NIAAA to Dr. Ce Shang.

Appendix

Appendix Table 1:

Pass-through rates of excise beer taxes to beer prices, with controls of HHIs

| Prices | High | Average | Low | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Tax (t) | 3.34* (1.51) |

4.73** (1.46) |

0.36 (2.52) | 2.96** (1.93) |

3.94*** (1.37) |

1.0 (0.19) | 1.49* (0.58) |

1.75+ (0.94) |

1.66 (1) |

| HHI (t) | −2.14 (4.65) | 0.78 (5.24) | 0.96 (2.52) | 0.77 (2.74) | 2.51 (3.34) | 0.48 (1.91) | 0.68 (1.77) | 0.47 (1.87) | 0.31 (1.39) |

| HHI × Tax (t) | 0.4 (4.15) | −1.44 (4.36) | 10.26 (11.07) | −2.72 (2.75) | −4.77 (5.23) | 5.19 (8.19) | 0.38 (2.21) | 1.24 (3.5) | 1.14 (4.31) |

| Model | FE | Dynamic | FD | FE | Dynamic | FD | FE | Dyanmic | FD |

| N | 115 | 92 | 92 | 115 | 92 | 92 | 115 | 92 | 92 |

Note:

p<0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001. Standard errors clustered at the country level are in parentheses. Regressions control for year fixed effects, country fixed effects, and whether beer taxes are lower for small producers and whether beer taxes are progressive by strength. Demographic controls are GDP per capita, the percent of population aged 15-64, and the percent of population aged 65 and over. FD models control for the first differences of these covariates.

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Ce Shang, Department of Internal Medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, Ohio, US.

Anh Ngo, Oklahoma Tobacco Research Center, Stephenson Cancer Center, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, US.

Frank J Chaloupka, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, US.

References

- 1.Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C: A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Preventive Medicine. 38, 613–19 (2004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagenaar AC, Salois MJ, Komro KA: Effects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: A meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studies. Addiction. 104, 179–90 (2009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagenaar AC, Tobler AL, Komro KA: Effects of alcohol tax and price policies on morbidity and mortality: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health. 100, 2270–78 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu X, Chaloupka FJ: The effects of prices on alcohol use and its consequences. Alcohol Research & Health. 34, 236 (2011) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dutkowsky DH, Sullivan RS: Excise taxes, consumer demand, over-shifting, and tax revenue. Public Budgeting & Finance. 34, 111–25 (2014) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dutkowsky DH, Sullivan RS: Excise taxes, over-shifting, cross-elasticity, and tax revenue. Applied Economics Letters. 24, 113–16 (2017) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tremblay MJ, Tremblay VJ: Tax incidence and demand convexity in Cournot, Bertrand, and Cournot-Bertrand Models. Public Finance Review. 45, 748–70 (2017) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young DJ, Bielínska-Kwapisz A: Alcohol taxes and beverage prices. National Tax Journal. 55, 57–73 (2002) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fullerton D, Metcalf GE: Tax incidence. Handbook of Public Economics. 4, 1787–1872 (2002) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanson A, Sullivan R: The incidence of tobacco taxation: Evidence from geographic micro-level data. National Tax Journal. 62, 677–98 (2009) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell C, van Walbeek C: How does a change in the excise tax on beer impact beer retail prices in South Africa? South African Journal of Economics. 84, 555–73 (2016) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shrestha V, Markowitz S: The pass-through of beer taxes to prices: Evidence from state and federal tax changes. Economic Inquiry. 54, 1946–62 (2016) [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization: WHO technical manual on tobacco tax administration. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: (2010) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tirole J: The theory of industrial organization. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA: (1988) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaloupka FJ, Kostova D, Shang C: Cigarette excise tax structure and cigarette prices: Evidence from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey and the U.s. National Adult Tobacco Survey. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 16, s3–s9 (2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shang C, Chaloupka FJ, Zahra N, Fong GT: The distribution of cigarette prices under different tax structures: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation (ITC) Project. Tobacco Control. 28, s31–s36 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson JP, Moran JR: Effects of alcohol taxation on prices: A systematic review and meta-analysis of pass-through rates. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy. 20, 1–21 (2020) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenkel DS: Are alcohol tax hikes fully passed through to prices? Evidence from Alaska. American Economic Review. 95, 273–77 (2005) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stehr M: The effect of Sunday sales bans and excise taxes on drinking and cross-border shopping for alcoholic beverages. National Tax Journal. 60, 85–105 (2007) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siegel M, Grundman J, DeJong W, Naimi TS, King C III, Albers AB, Williams RS, Jernigan DH: State-specific liquor excise taxes and retail prices in 8 US states, 2012. Substance Abuse. 34, 415–21 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergman UM, Hansen NL: Are excise taxes on beverages fully passed through to prices? The Danish evidence. FinanzArchiv: Public Finance Analysis. 75, 323–56 (2019) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bakó B, Berezvai Z: Excise tax overshifting in the Hungarian beer market. (2013) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carbonnier C: Pass-through of per unit and ad valorem consumption taxes: Evidence from alcoholic beverages in France. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy. 13, 837–63 (2013) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ally AK, Meng Y, Chakraborty R, Dobson PW, Seaton JS, Holmes J, Angus C, Guo Y, HIll-McManus D, Brennan A: Alcohol tax pass-through across the product and price range: Do retailers treat cheap alcohol differently? Addiction. 109, 1994–2002 (2014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ardalan A, Kessing SG: Tax pass-through in the European beer market. Empirical Economics. (2019). 10.1007/s00181-019-01767-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blecher E, Liber A, Van Walbeek C, Rossouw L: An international analysis of the price and affordability of beer. PLOS One. 13, e0208831 (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blecher EH, van Walbeek CP: An international analysis of cigarette affordability. Tobacco Control. 13, 339–46 (2004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shang C, Wang X, Chaloupka FJ: The association between excise tax structures and the price variability of alcoholic beverages in the United States. PLOS One. 13, e0208509 (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker P, Brechling V: The impact of excise duty changes on retail prices in the UK. Fiscal Studies. 13, 48–65 (1992) [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Donoghue T, Rabin M: Optimal sin taxes. Journal of Public Economics. 90, 1825–49 (2006) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sorensen PB: The theory of optimal taxation: What is the policy relevance? International Tax and Public Finance. 14, 383–406 (2007) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mankiw NG, Weinzierl M, Yagan D: Optimal taxation in theory and practice. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 23, 147–74 (2009) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffith R, O’Connell M, Smith K: Tax design in the alcohol market. Journal of Public Economics. 172, 20–35 (2019) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pesko MF, Kruger J, Hyland A: Cigarette price minimization strategies used by adults. American Journal of Public Health. 102, e19–e21 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pesko MF, Licht AS, Kruger JM: Cigarette price minimization strategies in the United States: Price reductions and responsiveness to excise taxes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 15, 1858–66 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pesko MF, Xu X, Tynan MA, Gerzoff RB, Malarcher AM, Pechacek TF: Per-pack price reductions available from different cigarette purchasing strategies: United States, 2009-2010. Preventive Medicine. 63, 13–19 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu X, Pesko MF, Tynan MA, Gerzoff RB, Malarcher AM, Pechacek TF: Cigarette price-minimization strategies by US smokers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 44, 472–6 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shang C, Lee HM, Chaloupka FJ, Fong GT, Thompson M, O’Connor RJ: Association between tax structure and cigarette consumption: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation (ITC) Project. Tobacco Control. 28, s31–s36 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blanchette JG, Lira MC, Heeren TC, Naimi TS: Alcohol policies in US states, 1999-2018. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81, 58–67 (2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naimi TS, Daley JI, Xuan Z, Blanchette JG, Chaloupka FJ, Jernigan DH: Who would pay for state alcohol tax increases in the United States? Preventing Chronic Disease. 13, E67 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]