Abstract

Proteins naturally self‐assemble to function. Protein cages result from the self‐assembly of multiple protein subunits that interact to form hollow symmetrical structures with functions that range from cargo storage to catalysis. Driven by self‐assembly, building elegant higher‐order superstructures with protein cages as building blocks has been an increasingly attractive field in recent years. It presents an engineering challenge not only at the molecular level but also at the supramolecular level. The higher‐order constructs are proposed to provide access to diverse functional materials. Focussing on design strategy as a perspective, current work on protein cage supramolecular self‐assembly are reviewed from three principles that are electrostatic, metal‐ligand coordination and inherent symmetry. The review also summarises possible applications of the superstructure architecture built using modified protein cages.

Inspec Keywords: molecular biophysics, proteins, self‐assembly

1. INTRODUCTION

Protein cages are ubiquitous with diversified morphologies and functionalities [1]. Typical protein cages are symmetrical, hollow, and nanometre‐sized [2]. The protein cage family mainly consists of virus‐like particles (VLPs), ferritins (Ftn), lumazine synthases (LS), and heat shock proteins (Hsp) [2]. VLPs make up the largest segment of the family and are represented by the cowpea mosaic virus, cowpea chlorotic mottle virus (CCMV), brome mosaic virus, and the bacteriophage MS2 [2]. Protein cages have received extensive research attention in recent years due to their various advantages (e.g., good biocompatibility, charge transport properties, thermostability) and potential applications [3]. Utilising genetic or chemical modification [4], the exterior surface, the interior surface, and the interface between subunits of protein cages can be designed to endow non‐natural functionalities [2].

Supramolecular self‐assembly is a process in which building blocks form organised structures via non‐covalent interactions without any external directions [5]. There are seven kinds of non‐covalent interactions that can drive self‐assembly including hydrogen‐bonding, π–π interactions, hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic interactions, metal‐ligand coordination, receptor‐ligand recognitions, and van der Waals interactions [6, 7]. As a fabrication strategy, self‐assembly can drive basic components to build nanostructures from zero‐dimensional (0D) nanocluster/nanoparticles to three‐dimensional (3D) hydrogels [8].

The inclination of natural proteins to form organised assemblies to function prompted the exploration of utilising protein cages as the building blocks for higher‐order structures [9]. To date, researchers have achieved a variety of accomplishments in protein and peptide assembly. But, there remain some challenges considering the fragile feature and structural complexities [10]. Biotechnical and chemical approaches have been applied on protein assembly to design different kinds of protein–protein interactions (PPIs) [10]. Apart from typical PPIs, DNA–DNA interactions, coiled coil interactions, and other interactions produced by supramolecular self‐associating components have been developed to build self‐assembling superstructures by protein‐based building blocks [10]. For instance, Brodin et al. [11] connected oligonucleotides to catalase to construct crystalline superlattices by DNA–DNA interactions. Recent work on protein assemblies have been reviewed elsewhere [9, 10]. However, explorations on utilising a particular type of protein, protein cages, are limited.

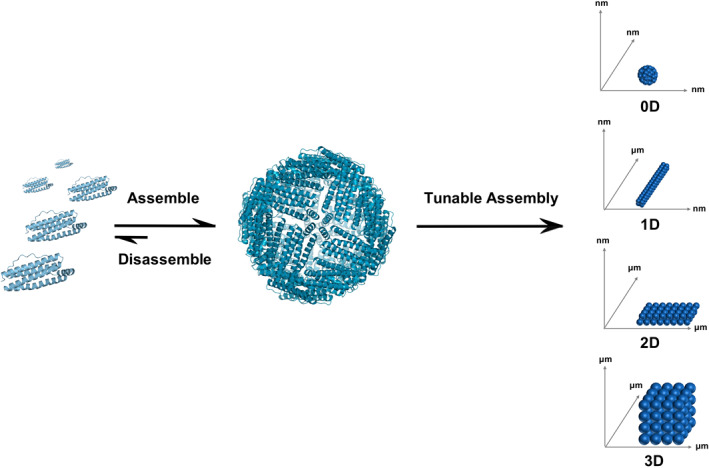

Among all types of proteins, protein cages are promising candidates due to their conformance [2, 4]. A protein cage can maintain the integrity of its original structure with modified functions after being incorporated into a higher‐order structure [4]. In addition, protein cages are flexible units in the assembly process. The cage protein subunits serve as building blocks owing to the ability of protein cages to assemble and disassemble. For instance, the 24 subunits of ferritin self‐assemble into the ferritin protein cage, and the protein cage itself can further be used to build higher‐order superstructures. Figure 1 describes the processes of building the superstructure showing the two‐step supramolecular assembly. First, the protein subunits serve as the molecular building blocks and second, the protein cage itself as the building blocks. The supramolecular assembly of the protein subunits results in the protein cages and the supramolecular assembly of the protein cages results in the superstructures.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the assembly processes resulting in protein cage superstructures. Protein subunits self‐assemble into protein cage of 0D. Engineering of the exterior surface of the protein cages drive the formation of superstructures across different length scales resulting in 0D, 1D, 2D, and 3D structures

The protein cage‐based superstructures have been proposed to have a wide range of potential applications. Most protein cages are robust thermally and mechanically, serving as a good foundation for subsequent assembly [2, 23]. By incorporating other components, such as metal particles, drugs, fluorescent dyes, and antibodies, the delicate architectures based on protein cages can offer additional functionalities as an amalgamation of the characteristics of protein cages and functional aspects of the incorporated molecules [10]. The diverse structures constructed via self‐assembly inspire infinite possibilities of preparing functional biomaterials [7], paving ways for the future development of applications in diagnostics [24], catalyses [25], and bioelectronics [26]. With regard to diagnostics, the hierarchical ternary structure synthesised by Kostiainen's group is an example [24]. The work takes advantage of ferritin as a biological building block and avoids the weakness of losing the effectiveness to produce singlet oxygen when utilising phthalocyanines (Pc) in buffer solution [24]. The singlet oxygen offered the biohybrid crystal an application of diagnostic arrays [24]. Nanoenzyme built from protein cages is an illustration of application in catalysis with fabulous biocompatibility, impressive improvement of catalytic activity, and reusable features [7]. Attachment of biotin‐tagged horseradish peroxidase enzyme to CCMV–avidin crystals results in efficient loading and concentration of active enzymes [12]. Although several fruitful studies have been conducted in regards to the application of individual protein cages [26, 27, 28], limited research studies have delved into the functional characterisations of the exquisite superstructures assembled from protein cages.

The work associated with protein cages that has been summarised in other reviews includes connectability [1], artificial design [29], construction of virus‐based protein cages [30], the length scale of the assembly [2], suggested functional manner (e.g. enzyme encapsulation [31]), and the platform of advanced materials [32]. In this review, we will present recent work on protein cage supramolecular self‐assembly and categorise the works based on three most widely used strategies that include two non‐covalent interactions as the driving force of the assembly (i.e., electrostatic interactions and metal‐ligand coordination) and modifications based on the inherent symmetry of protein cages. The potential functions and applications will also be discussed. This review sheds light on the future developments of functional biomaterials leveraging on designed self‐assembly with protein cages as the building blocks.

2. ORGANISED ASSEMBLIES EXPLOITING PROTEIN CAGES AS BUILDING BLOCKS

2.1. Designs based on electrostatic interactions

Electrostatic interaction is a type of long‐range, non‐selective, and relatively strong non‐covalent interaction [33]. In nature, electrostatic interactions have pivotal roles that include molecular recognition, protein assembly, protein stabilisation, and regulation of catalytic reactions [34]. Inspired by the wisdom of nature, protein cages’ assembly driven by electrostatic interactions have been studied for decades. Notably, Kostiainen et al. have accomplished a series of work based on electrostatic interactions. They started with constructing photosensitive dendron–CCMV complexes of micrometre sizes, which could be assembled by relying on oppositely charged components and disassembled using light as the trigger [13]. In 2011, they constructed temperature‐switchable architecture with CCMV and copolymer, containing poly(diethyleneglycol methyl ether methacrylate) (poly(DEGMA)) and poly((2‐dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate) blocks [14]. The assembly and disassembly were dependent on the cloud point temperature (T cp) of the poly(DEGMA) block [14]. In 2013, they prepared 3D binary nanoparticle superlattices using protein cages including CCMV and ferritin with 1‐pentanethiol‐stabilised gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) [15]. The particle–particle electrostatic interactions were controlled by the Debye screening length. The strong interaction resulted in gel‐like aggregation, while the weak interaction would not be enough to initiate an assembly. Prior to this work, the constructions by Kostiainen et al. were protein cages assembled together with artificial synthetic components. They moved forward to utilise natural components to incorporate them with protein cages. In 2014, Liljeström et al. assembled CCMV and avidin via electrostatic interactions, the process of which was built without covalent modification of protein cages [12]. The resulting crystal could respond to external stimuli and presented the ability to be pre‐ or post‐functionalised. In 2018, Korpi et al.fabricated ferritin and CCMV with supercharged fusion peptides (K72) based on their opposite charges [16]. Other groups also successfully attained ordered assemblies via electrostatic interactions. For instance, Künzle et al. generated a 3D binary superlattice using oppositely charged ferritin as building blocks [35]. The building blocks were computationally designed and genetically modified. Two types of metal oxide nanoparticles were encapsulated in the cavities, which demonstrated potentially versatile applications of protein containers based on cargos. Brunk et al. realised tunable 3D ordered arrays via the electrostatic interaction between engineered VLPs and PAMAM dendrimer [36]. The driving force was shown to be a balance of the electrostatic attraction and thermal motion of VLPs. Simulation‐driven prediction was also applied in this work to exhibit how the capacity to form arrays can be further improved (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Supramolecular assemblies of protein cages based on electrostatic interactions. (a) Photosensitive dendron–CCMV complexes [13]. (b) Temperature‐switchable assembly with CCMV and copolymer, adapted with permission from [14]. (c) Three‐dimensional binary nanoparticle superlattices using CCMV and ferritin with 1‐pentanethiol‐stabilised gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) [15]. (d) Binary assembly of CCMV and avidin [12]. (e) Cocrystals from supercharged fusion peptides and protein cages [16]. CCMV, cowpea chlorotic mottle virus. All figures are adapted with permissions. Figures 2, 3, 4 adapted copyrighted figures from references [12, 13, 14, 15, 16], [17, 18, 19], [20, 21, 22] and have obtained permission to use the materials

2.2. Designs based on metal‐ligand coordination

Metal‐ligand coordination is also a promising way to induce the formation of sophisticated structures. Metal‐ligand coordination is a highly directional interaction [37]. Nature's metalloprotein is one of the prototypes that directs us to construct exquisite complexes. Tezcan [37] and his coworkers have been focussing on protein self‐assembly via metal coordination [37]. In recent years, their work has included protein cages’ self‐assembly mediated by metal‐ligand coordination [17]. Sontz et al. generated a 3D ternary crystal of the body‐centred cubic (bcc) arrangement via zinc‐protein coordination [17]. The fabrication was significantly permeable to solutes resulting from the tightly packed bcc structure and porous character of hollow ferritins. They further synthesised and characterised a group of protein‐based metal‐organic frameworks (MOFs) to explore the criteria of an organised structure systematically [18]. They combined different kinds of metal ions including zinc, nickel, and cobalt ions, synthetic dihydroxamate linker, and ferritin to form 3D protein‐based crystals and found that different components could influence the architecture modularly. Other illustrative work of this group emphasised on its functional aspect. Recently, inspired by the phenomenon resulting from changing the concentration of magnesium ion in their previous work, Künzle et al. created an assembly tunable between a unitary structure and a binary structure [35]. The parameter that controlled the crystal pattern was the concentration of magnesium ions. They found that magnesium ions, coordinated in an octahedral manner, participated in the formation of the crystal structure when the concentration was high [19]. In contrast, when the concentration of magnesium ions was low, aspartic acid residues and glutamic acid residues contributed to the contacts between protein cages (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Supramolecular assemblies of protein cages based on metal‐ligand coordination. (a) 3D ternary crystal of the body‐centred cubic (bcc) arrangement via zinc‐protein coordination [17]. (b) Ferritin−MOFs with the bcc structure [18]. (c) The assembly tunable between a unitary structure and a binary structure [19]. 3D, three‐dimensional; MOF, metal‐organic framework. All figures are adapted with permissions. Figures 2, 3, 4 adapted copyrighted figures from references [12, 13, 14, 15, 16], [17, 18, 19], [20, 21, 22] and have obtained permission to use the materials

2.3. Designs based on inherent symmetry

Another marvellous characteristic of protein cages is their inherent symmetry [2]. Combined with the strength of different kinds of interactions, versatile higher‐order architectures have been created by employing the modification sites neighbouring the symmetrical axes of the building blocks (Figure 4). In regard to the 3D Zn‐ferritin crystal of Tezcan's group, the construction took advantage of manipulating sites near C3 axes [17]. Furthermore, utilising the design philosophy of genetically changing, adding, or reducing components near the C4 axes of ferritin, several 2D/3D assemblies have been obtained by manipulating the protein sequence of the protein cage building blocks [20, 21]. Zhou et al. [21] realised the formation of 2D and 3D protein superlattices by introducing π–π stacking interactions at the symmetry axes. They substituted the single amino acid residue close to the C4 axes, Glu162, to Phe, Tyr, and Trp, leading to the reversible and tunable organised assembly of ferritin nanocages. Through a bottom‐up strategy, Zheng et al. gained 2D and 3D protein arrays showing a simple cubic packing pattern [20]. This construction was driven by hydrophobic interactions from the amyloidogenic motifs connected to the external surface of ferritins adjacent to the C4 axes. The alternation of the 2D and 3D structures could be controlled by adjusting the pH or the reaction time. To acquire metal‐ligand coordination with nickel ions as the driving force, Gu et al. linked His2 motifs to Thr157 close to the C4 axes of ferritins, resulting in the successful generation of a binary protein–metal crystalline framework [22].

FIGURE 4.

Supramolecular assemblies of protein cages based on inherent symmetry. (a) 2D and 3D protein superlattices via π–π stacking interactions [21]. (b) 2D and 3D protein arrays driven by hydrophobic interactions [20]. (c) Binary protein–metal crystalline framework [22]. 2D, two‐dimensional; 3D, three‐dimensional. All figures are adapted with permissions. Figures 2, 3, 4 adapted copyrighted figures from references [12, 13, 14, 15, 16], [17, 18, 19], [20, 21, 22] and have obtained permission to use the materials

3. POTENTIAL FUNCTIONAL MATERIAL: PROTEIN CAGE‐BASED SUPERSTRUCTURES

Different kinds of organised structures can endow enhanced properties, and therefore, can further facilitate the exploration of the unexploited field of functional materials [32]. To date, materials made of decorated protein cages have been suggested to have potential applications. Zhang et al. [38] developed a hybrid crystal with face‐centred cubic arrangement by integrating the K86Q surface mutation on ferritin with hydrogel polymers [38]. The mechanical properties of this material were investigated to check whether the existence of the hydrogel could cause the crystal to have different mechanical behaviours [38]. By utilising small‐angle X‐ray scattering, they characterised the altering of the lattice permutation related to expansion and the lattice ability to reverse after expansion. The swelling–contraction behaviour of the lattice could be regulated by altering the ion content. Moreover, this material demonstrated self‐healing ability due to the reversible interplays between ferritin and the copolymer hydrogel [15]. Further studies included enhancing the direction of the dynamic and mechanical properties [39]. Rhombohedral or trigonal ferritin, which preserved anisotropic symmetries, could gain directionality that is critical for functional materials inclusive of biological devices. They found that the expansion and contraction of this type of ferritin‐based crystals were anisotropic and the crystallinity was maintained. Bailey et al. amalgamated ferritin with three dihydroxamate linkers and two kinds of metal ions, zinc and nickel ions, to constitute protein MOFs with tunable thermostabilities and different thermomechanical properties [40]. Offered by the sparsely packed structure, a transformation with a large volumetric change around room temperature was observed in the fdh‐Ni‐ferritin type, which adopted 2,5‐furan dihydroxamic acid (H2fdh) as a linker and nickel ions. This material was expected to be applied to sensing and memory devices. Recently, Chakraborti et al. developed a binary superlattice based on Thermotoga maritima ferritins (TmFtn) and gold nanoparticles that successfully encapsulated lysozyme into the lumen of TmFtn [41]. The enzymatic activity was retained after the encapsulation and assembling into the superlattice.

Although a few signs of progress have been achieved in the functional aspect of supramolecular structures constructed by protein cages, more research needs to be devoted to this area. The extensive work on individual protein cages provides hints on the direction of analysing the functional feature of the protein cage‐based supramolecular structures. Among future applications, the diverse cargos that have been indicated to be encapsulated into the cavity of protein cages could endow delivery potential to the materials [3] and offer possible ideas for constructing synthetical organelle‐mimicking materials [28]. Table 1 summarises the types of protein cages, the driving forces involved in the formation of the superstructure, and the co‐assembling component.

TABLE 1.

The main design principles, driving forces and co‐assembling components of different protein cages

| Driving forces | Protein cage type—Source | Co‐assembling component | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic interaction | CCMV | Dendron | [13] |

| CCMV | Copolymer | [14] | |

| CCMV, Ferritin—recombinant, ferritin from hyperthermophile Pyrococcus furiosus | AuNPs | [15] | |

| CCMV | Avidin | [12] | |

| CCMV—Vigna unguiculata, ferritin—Pyrococcus furiosus | Supercharged fusion peptides | [16] | |

| Human heavy‐chain ferritin | None | [35] | |

| P22 VLP variants | PAMAM dendrimer | [36] | |

| Ferritin—Thermotoga maritima | AuNPs | [41] | |

| Metal‐ligand coordination | Human heavy‐chain ferritin | None a | [17] |

| Human heavy‐chain ferritin | Synthetic dihydroxamate linkers | [18] | |

| Human heavy‐chain ferritin | None | [19] | |

| Recombinant shrimp ferritin | None a | [22] | |

| Human heavy‐chain ferritin | Copolymer | [38] | |

| Human ferritin | Dihydroxamate linkers | [40] | |

| Hydrophobic interactions | Recombinant human H chain ferritin | None a | [20] |

| π–π Stacking interactions | Recombinant human H chain ferritin | None a | [21] |

Abbreviations: CCMV, cowpea chlorotic mottle virus; VLP, virus‐like particle.

The design includes manipulations at the inherent symmetry.

4. PERSPECTIVE AND CONCLUSION

This review summarises a variety of protein cages that have been utilised as building blocks in supramolecular assembly, design principles, and potential applications. The advantages of choosing protein cages as building blocks include conformance, flexibility, and thermal and mechanical robustness. Stemming from the applications of individual protein cages, the potential functionality of protein cage‐based superstructures can be conceived. Except for the fields that have been mentioned (e.g. sensing, encapsulation, and organelle‐mimicking materials), biomedicine, therapy, and scaffold are potential applications of the higher‐order structures made of protein cages. Although work mentioned in Section 3 have included functional characterisations [38, 39, 40, 41], transition from preliminary to device level characterisation is still challenging.

Despite the extensive work in protein assembly, the study of protein cages, which are a member of the protein family, in the context the supramolecular self‐assembly field has been limited. Recent progress in supramolecular assembly with protein cages as the building blocks is grouped into three design principles that are based on electrostatic interactions, metal‐ligand coordination, and the location of the modifications at the inherent symmetry. A number of work has been reported on leveraging non‐covalent interactions, such as hydrophobic interactions, to drive protein cages’ assembly into superstructures. While various achievements have been attained in constructing different types of higher‐order architectures, regulations of such structures in a controlled fashion and the understanding of both thermodynamic and kinetic mechanisms behind the created superstructures and patterns require further explorations. Subsequent integration into molecular devices and systematic functional characterisations will unlock and realise the potential of superstructures built using protein cages.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was funded by Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Sun, R. , Lim, S .: Protein cages as building blocks for superstructures. Eng. Biol. 5, (2), 35–42 (2021). 10.1049/enb2.12010

REFERENCES

- 1. Majsterkiewicz, K. , Azuma, Y. , Heddle, J.G. : Connectability of protein cages. Nanoscale Adv. (2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aumiller, W.M. , Uchida, M. , Douglas, T. : Protein cage assembly across multiple length scales. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47(10), 3433–3469 (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhaskar, S. , Lim, S. : Engineering protein nanocages as carriers for biomedical applications. NPG Asia Mater. 9(4), e371–e371 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Uchida, M. , et al.: Biological containers: protein cages as multifunctional nanoplatforms. Adv. Mater. 19(8), 1025–1042 (2007) [Google Scholar]

- 5. Whitesides, G.M. , Grzybowski, B. : Self‐assembly at all scales. Science. 295(5564), 2418–2421 (2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang, J. , et al.: Peptide self‐assembly: thermodynamics and kinetics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45(20), 5589–5604 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun, H. , et al.: Nanostructures based on protein self‐assembly: from hierarchical construction to bioinspired materials. Nano. Today. 14, 16–41 (2017) [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gong, C. , et al.: Hierarchical nanomaterials via biomolecular self‐assembly and bioinspiration for energy and environmental applications. Nanoscale. 11(10), 4147–4182 (2019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bai, Y. , Luo, Q. , Liu, J. : Protein self‐assembly via supramolecular strategies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45(10), 2756–2767 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Luo, Q. , et al.: Protein assembly: versatile approaches to construct highly ordered nanostructures. Chem. Rev. 116(22), 13571–13632 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brodin, J.D. , Auyeung, E. , Mirkin, C.A. : DNA‐mediated engineering of multicomponent enzyme crystals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am. 112(15), 4564–4569 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liljeström, V. , Mikkilä, J. , Kostiainen, M.A. : Self‐assembly and modular functionalisation of three‐dimensional crystals from oppositely charged proteins. Nat. Commun. 5(1), 1–9 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kostiainen, M.A. , et al.: Self‐assembly and optically triggered disassembly of hierarchical dendron–virus complexes. Nat. Chem. 2(5), 394 (2010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kostiainen, M.A. , et al.: Temperature‐switchable assembly of supramolecular virus–polymer complexes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21(11), 2012–2019 (2011) [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kostiainen, M.A. , et al.: Electrostatic assembly of binary nanoparticle superlattices using protein cages. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8(1), 52–56 (2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Korpi, A. , et al.: Self‐assembly of electrostatic cocrystals from supercharged fusion peptides and protein cages. ACS Macro Lett. 7(3), 318–323 (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sontz, P.A. , et al.: A metal organic framework with spherical protein nodes: rational chemical design of 3D protein crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137(36), 11598–11601 (2015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bailey, J.B. , et al.: Synthetic modularity of protein–metal–organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139(24), 8160–8166 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Künzle, M. , Eckert, T. , Beck, T. : Metal‐assisted assembly of protein containers loaded with inorganic nanoparticles. Inorg. Chem. 57(21), 13431–13436 (2018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zheng, B. , et al.: Designed two‐and three‐dimensional protein nanocage networks driven by hydrophobic interactions contributed by amyloidogenic motifs. Nano. Lett. 19(6), 4023–4028 (2019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhou, K. , et al.: On‐axis alignment of protein nanocage assemblies from 2D to 3D through the aromatic stacking interactions of amino acid residues. ACS Nano. 12(11), 11323–11332 (2018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gu, C. , et al.: Structural insight into binary protein metal–organic frameworks with ferritin nanocages as linkers and nickel clusters as nodes. Chem.—Eur. J. 26(14), 3016–3021 (2020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sarker, M. , Tomczak, N. , Lim, S. : Protein nanocage as a pH‐switchable pickering emulsifier. ACS Appl. Mater Interfaces. 9(12), 11193–11201 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mikkilä, J. , et al.: Hierarchical organization of organic dyes and protein cages into photoactive crystals. ACS Nano. 10(1), 1565–1571 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Uchida, M. , et al.: Modular self‐assembly of protein cage lattices for multistep catalysis. ACS Nano. 12(2), 942–953 (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fujita, K. , et al.: A photoactive carbon‐monoxide‐releasing protein cage for dose‐regulated delivery in living cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55(3), 1056–1060 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Azuma, Y. , Bader, D.L. , Hilvert, D. : Substrate sorting by a supercharged nanoreactor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140(3), 860–863 (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Waghwani, H.K. , et al.: Virus‐like particles (VLPs) as a platform for hierarchical compartmentalisation. Biomacromolecules. 21(6), 2060–2072 (2020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stupka, I. , Heddle, J.G. : Artificial protein cages–inspiration, construction, and observation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 64, 66–73 (2020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Selivanovitch, E. , Douglas, T. : Virus capsid assembly across different length scales inspire the development of virus‐based biomaterials. Curr. Opin. Virol. 36, 38–46 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chakraborti, S. , et al.: Enzyme encapsulation by protein cages. RSC Adv. 10(22), 13293–13301 (2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Korpi, A. , et al.: Highly ordered protein cage assemblies: a toolkit for new materials. e1578. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 12(1) (2020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Faul, C.F. , Antonietti, M. : Ionic self‐assembly: facile synthesis of supramolecular materials. Adv. Mater. 15(9), 673–683 (2003) [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakamura, H. : Roles of electrostatic interaction in proteins. Q. Rev. Biophys. 29(1), 1–90 (1996) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Künzle, M. , Eckert, T. , Beck, T. : Binary protein crystals for the assembly of inorganic nanoparticle superlattices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138(39), 12731–12734 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brunk, N.E. , et al.: Linker‐mediated assembly of virus‐like particles into ordered arrays via electrostatic control. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2(5), 2192–2201 (2019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Salgado, E.N. , Radford, R.J. , Tezcan, F.A. : Metal‐directed protein self‐assembly. Acc. Chem. Res. 43(5), 661–672 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang, L. , et al.: Hyperexpandable, self‐healing macromolecular crystals with integrated polymer networks. Nature. 557(7703), 86–91 (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Han, K. , et al.: Anisotropic dynamics and mechanics of macromolecular crystals containing lattice‐patterned polymer networks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142(45), 19402–19410 (2020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bailey, J.B. , Tezcan, F.A. : Tunable and cooperative thermomechanical properties of protein–metal–organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142(41), 17265–17270 (2020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chakraborti, S. , et al.: Three‐dimensional protein cage array capable of active enzyme capture and artificial chaperone activity. Nano. Lett. 19(6), 3918–3924 (2019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]