Abstract

The lived experiences of work-related burdens in the daily working routines of home care workers are insufficiently investigated. Therefore, the aim of this study is to examine the types, frequencies, and distributions of work-related burdens and to explore their co-occurrence. Qualitative data was collected via audio diaries and analyzed applying a crossover mixed analysis using content as well as network analysis. In all, 23 home care workers (mean age = 46.70 ± 10.40; 91.30% female) produced 242 diary entries. Participants reported work-related burdens 580 times with 77 different types, predominately in relation to work organization (50.5%). Network analysis reveals a complex picture, which shows the strong relation between time pressure and travel between homes, and identifies additional tasks as the central node in the network of burdens. A holistic understanding of setting-specific burdens provides an important starting point for measures of workplace health promotion.

Keywords: home care, stress, caregiving, health, mixed methods

What this paper adds

• The daily working routines of home care workers entail complex networks of burdens, in which a variety of causal relations occurs.

• Burdens related to additional tasks and traveling between homes were found to have a central role within networks of burdens.

• Compared to the frequency of other burdens, physical strain has a subordinate role in the experiences of home care workers.

Applications of study findings

• Efforts should be made to develop new systems of time scheduling that are in accordance with the reality of work in home care.

• Measures of workplace health promotion should address central nodes within the networks of burdens, such as additional tasks or traveling between homes.

• Audio diaries and cross over mixed analysis represent valuable additions to the methodological toolkit in gerontological research.

Introduction

As population ages and family structures change, formal long-term care is an issue of increasing importance to almost all high- and middle-income countries. The number of long-term care recipients aged 65 or over has nearly doubled between 2007 and 2017 in OECD member states (Muir, 2017). Within this development, there is a clear trend towards the de-institutionalization of long-term care, responding to policy funding priorities and the preference of care recipients to stay as long as possible in their home environment (European Commission & Social Protection Committee, 2021). In the EU-27 states, nearly 7 million people received home care in 2019; and the number of home care recipients is projected to increase by more than one million in 2030 (European Commission & Social Protection Committee, 2021). Similarly, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistic anticipates a continuation of the trend towards increased shares of home care in the expanding long-term care market and predicts an increased need for home care workers by up to one third in 2030 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistic, 2021). However, research about the home care sector is not growing as fast as the branch itself. There are multiple blind spots in home care literature (Contandriopoulos et al., 2021), including limited knowledge about the experience of paid caregivers in their daily work.

“Home care worker” is a general term for a variety of social and health care professionals, from assistants with little or no training to registered nurses with several years of education, who deliver nursing care (e.g., dressing change), personal care (e.g., personal hygiene), and domestic care (e.g., ordinary housework) (Van Eenooa et al., 2018). However, home care workers describe their work as “different kind of nursing” (Fjørtoft et al., 2020), as specific working conditions determine the everyday working life. Working alone and having the care recipients’ private homes as the work environment are the most characteristically features in this care sector (Fjørtoft et al., 2020) affecting all other aspects of work. Patients’ homes are unpredictable workplaces (Grasmo et al., 2021), are hardly equipped for the provision of care (King et al., 2018), and require traveling between homes (Cœugnet et al., 2016). Moreover, working in a private home implies a level of trust and intimacy, what affects the carer-patients’ relationship (Timonen & Lolich, 2019) and demands in many cases collaborating with family caregivers (Ris et al., 2019). Another specific characteristic shaping the daily working life in home care is the tight time schedule, which includes arrival times for all visits and an exact amount of time allocated for every single task. Additionally, patients frequently ask home care workers to do things, which are not part of their job and therefore not calculated in the time budget (Karlsson et al., 2020). These working conditions have a high potential for mental and physical burdens, which are associated with negative health consequences such as emotional exhaustion (Ruotsalainen et al., 2020), musculoskeletal disorders (Quinn et al., 2021) and a loss of health related quality of life in home care workers (Sjöberg et al., 2020).

The German Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (2021) categorizes work-related mental strains according to the four areas of (1) social relationships, (2) work content, (3) work organization, and (4) work environment. Home care workers are exposed to strains in all four areas (Quinn et al., 2021; Treviranus et al., 2021). Examples of this include strains related to relationships with colleagues, patients, and relatives (social relationships; Mojtahedzadeh, Wirth, et al., 2021), challenging client needs (work content; Karlsson et al., 2020), staffing challenges, high workloads and time pressure (work organization; Fjørtoft et al., 2020; Grasmo et al., 2021; Otto et al., 2019; Sjöberg et al., 2020), and dangerous traffic situations (work environment; Grasmo et al., 2021). In addition, the working conditions in home care are associated with a variety of physical strains such as working in awkward posture when assisting with toileting and bathing in private bathrooms or holding heavy loads when lifting patients (King et al., 2018; Otto et al., 2019).

However, to describe home care workers’ burden by focusing on single strains on a list seems to be too narrow and does not appropriately capture the complexity of their daily working routine.

Research on the interaction between different strains and multifaceted pathways to negative health outcomes is still in its infancy in home care. Much of the research on work-related burden and its consequences has been cross-sectional in design; thus, the findings are limited by snapshots of pre-selected variables and fail in determining whether a strain associated with an outcome is causal or not (Karlsson et al., 2020; Ruotsalainen et al., 2020). Existing qualitative studies in this field provide a more comprehensive picture of work-related burdens in home care, but are dominated by interviews and focus groups (e.g., Fjørtoft et al., 2020; Grasmo et al., 2021), which provide only one-time retrospective narratives. This methodological approach limits the insights into situated events, illustrating how and to what extent home care workers experience different types of work-related burdens, and how they link them in one storyline within a specific contextual framework (Williamson et al., 2015).

One promising methodological approach to address the blind spots previous studies have left behind, are diary studies (Bolger et al., 2003). Audio diaries were considered as preferable to their written counterparts, as verbal diary entries allow the inclusion of participants with limited literacy skills and may facilitate a greater depth of self-reflexivity (Crozier & Cassell, 2016; Williamson et al., 2015). Studies from the field of stress research show, that the method appears suitable for the delineation of the process-driven nature of stress, encourages participants to share sensitive information that might not come to light in surveys or interviews, and raise the awareness and reporting of specific circumstances under which stress arises (Cottingham et al., 2018; Crozier & Cassell, 2016; O’Reilly et al., 2022). As such, audio diaries are appropriate to reveal the hidden script of work-related burdens within the lived experience of home care workers. Moreover, the longitudinal nature of data collection allows an authentic assessment of the frequency and distribution of different strains within home care workers’ daily working routine (Crozier & Cassell, 2016).

Study Aim

Due to methodological limitations of previous studies, two research gaps can be identified: (1) The frequencies and distribution of different burdens within the home care workers’ daily working routine are insufficiently investigated, due to pre-selected variables and the lack of longitudinal studies. (2) Research on the interaction between different burdens and pathways to negative health outcomes is scarce, as cross-sectional studies fail to draw causal relationships and retrospective accounts within qualitative designs are limited in analyzing how burdens are linked within single storylines.

Consequently, the aim of this study is threefold: (1) to identify work-related burdens experienced by home care workers in their daily work, (2) to determine the frequency and distribution of the identified burdens, and (3) to investigate the co-occurrence of the experienced burdens and their causal relationships.

Method

Study Design

Using a merged methods approach (Gobo et al., 2021), qualitative longitudinal data was collected via audio diaries and analyzed applying a qualitative-dominant crossover mixed analysis (Hitchcock & Onwuegbuzie, 2020). This study is part of a larger mixed-methods research project called EMMA, which was conducted in six home care services in southern Germany. The Ethics Committee of the Technical University Munich approved all methods and materials (428/20 S-EB, 29 July 2020).

Data Collection

In September and October 2020, an information event was implemented to introduce the project to the participating home care services. Managers were asked to select four employees (three direct care workers, one administrative employee) for the audio diary study. Study participation was voluntary and written informed consent was obtained directly from all employees. Thus, a convenience sample of 24 employees was recruited. Participants were instructed to make short (one to 3 minutes) diary entries directly after 12 consecutive shifts. Where they wanted to make the diary entries was up to them. They received an audio diary package including (1) a digital voice recorder with a simple step-by-step user guide, (2) a prompt sheet on what to record in the diary, and (3) a short questionnaire on sociodemographic variables (gender, age, native language, region, and profession). The instructions about the diary entries were outlined as follows: “Please think about your workday. Which moments were particularly burdening?” Beside the question about particularly burdening moments, participants should also report about their joyful moments. These results are presented elsewhere (Gebhard et al., 2022).

Data Analysis

Within a crossover mixed analysis (Hitchcock & Onwuegbuzie, 2020), the two analytic approaches of qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2015) and thematic network analysis (Attride-Stirling, 2001) were merged, consecutively applied to the dataset, and complemented by quantification. MAXQDA 2020 (VERBI Software, 2019a) was used for the qualitative data analysis.

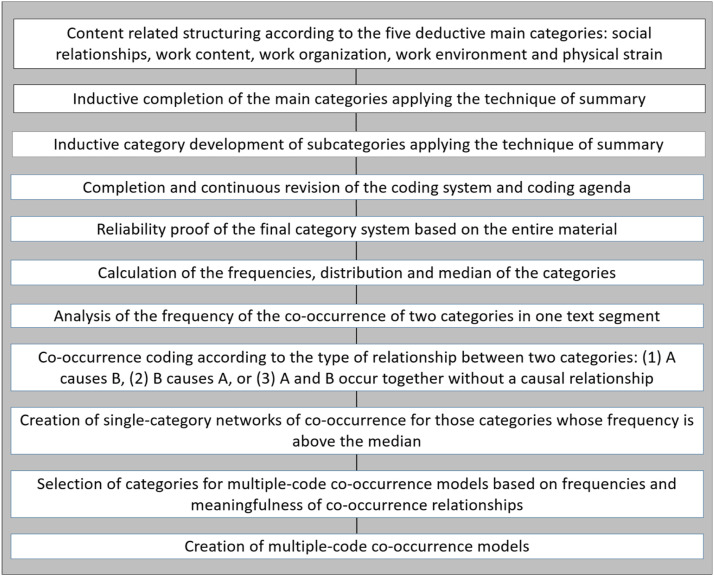

Audio diaries were transcribed completely and verbatim (an example is presented in the supplemental material 3). Transcripts were analyzed using qualitative content analysis based on Mayring (2015) to address the first and second study aim. The procedure of content-related structuring was applied to the material following five deductive categories of work-related burdens (social relationships, work content, work organization, work environment, physical strain). The technique of summarizing was used to complement those five main categories at level 1 of the category hierarchy. Subcategories for all lower levels of the category hierarchy were developed inductively. The category system and the coding agenda were steadily revised and complemented by two coders (both female; one worked as postdoc, one as student assistant with a bachelor’s degree; both were experienced in qualitative content analysis). In addition, a reliability proof of the final categories was made based on the entire material. Disagreements between the two coders were resolved by discussion and consensus. Finally, the qualitative data was quantified by calculating frequencies and percentage distributions for main categories and their subcategories.

Targeting the third study aim, thematic networks were created. This approach goes beyond the hierarchical organization of categories, as data is structured by its thematic linkages and illustrated as web-like nets (Attride-Stirling, 2001). Using MAXMaps, code co-occurrence models (VERBI Software, 2019b) were created to visualize the co-occurrence of categories as a network structure. To quantify the relationships between selected categories, the category intersection was evaluated by analyzing how often two categories have been assigned to a text segment together. To analyze how the content of two categories co-occurring in one text segment is related with each other, two coders worked through the text segments and coded them as (1) A causes B, (2) B causes A, or (3) A and B co-occur without any causal relation. To decide, which categories of burdens should be illustrated and connected within one code co-occurrence model a two-step procedure was conducted. First, a pre-selection was made based on the median of the categories´ frequencies. For all categories with frequencies higher than the median, code co-occurrence models were created, showing the network of each category separately. Secondly, those single-category networks were discussed based on the content meaningfulness and the co-occurrence frequencies. Derived from that, categories were selected to display their networks together in three multiple-code co-occurrence models. Figure 1 shows the steps performed in the analysis process.

Figure 1.

Analysis process.

Results

Sample Characteristics

In all, 23 home care workers (one participant withdrew consent) produced 242 diary entries, which results in an average of 10.52 entries per person. The length of the transcribed entries ranged from 3 to 841 words with an average length of 110.9 words per entry. Table 1 shows the sample characteristics.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics.

| Variable | Home care workers (n = 23) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 46.70 ± 10.40 |

| Gender, female (%) | 91.30 |

| Native language, German (%) | 78.26 |

| Region, urban (%) | 47.83 |

| Profession, care worker (%) | 86.96 |

Types, Frequencies and Distribution of Work-Related Burdens

Within 33 out of 242 diary entries, participants reported the absence of burdening situations. Therefore, the results are based on 209 diary entries. The frequency (n) indicates how often one category was mentioned across all entries. Multiple mentions per entry are possible if they refer to different storylines (situations). Home care workers described 77 different types of burdens, which were mentioned 580 times. In addition to the five deductively developed main categories, two further main categories were added inductively from the material: (1) strain symptoms and (2) strain-related negative consequences for quality of work. Figure 2 shows the distribution and frequencies of the seven main categories.

Figure 2.

Distribution and frequencies of burdens.

The category work organization includes five hierarchical levels with 29 subcategories. Aspects related to the work process were described most frequently (n = 212), with additional tasks (n = 79), time pressure (n = 27), and a high workload (n = 25) being reported most often as burdening. Figure 3 presents the categories’ structure up to level three (level four and five are presented in the supplemental material 1, Figure S1.1 and Figure S1.2), frequencies, and related statements.

Figure 3.

Distribution and frequencies of work organization.

The category work content includes four hierarchical levels with 13 subcategories. Burdens related to emotional strain were mentioned most often (n = 84). These burdens were mainly related to the suffering, dying, and fear of patients or relatives (n = 29), challenging patient behaviors (n = 21), and moral distress during work (n = 12). The categories’ structure up to level three (level four is presented in the supplemental material 1, Figure S1.3), frequencies, and related quotes are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Distribution and frequencies of work content.

Within the category work environment, 11 subcategories on four hierarchical levels were identified. Most burdens were experienced related to traveling (n = 53). The weather/darkness (poor visibility and driving conditions because of bad weather and darkness; n = 15) and the traffic (n = 13) were most frequently mentioned within this category. Figure 5 presents the categories’ structure up to level three (level four is presented in the supplemental material 1, Figure S1.4), frequencies, and related quotes.

Figure 5.

Distribution and frequencies of work environment.

The category social relationships contain ten subcategories on four hierarchical levels. Burdens in relation to the patients (n = 13), the team (n = 12), and the relatives (n = 12) were mentioned almost equally often. Regarding patients (n = 10) and relatives (n = 6), negative interactions were described as burdening. Within the team, missing cooperation was perceived negatively (n = 5). Figure 6 shows the categories’ structure up to level three (level four is presented in the supplemental material 1, Figure S1.5), frequencies, and related quotes.

Figure 6.

Distribution and frequencies of social relationships.

The category physical strain includes nine subcategories on three hierarchical levels. Presenteeism (work despite physical complaints or illness, n = 13) and strained postures (n = 9) were most frequently mentioned, followed by burdens due to pulling/pushing (n = 4) and lifting/transferring during care tasks (n = 3). Figure 7 illustrates the categories’ structure and related statements.

Figure 7.

Distribution and frequencies of physical strain.

Strain symptoms were reported as burdening (n = 51) in the categories of cognitive/mental symptoms (n = 18), physical symptoms (n = 16), and the feeling of being exhausted/burdened (n = 17). Strain-related negative consequences for quality of work were reported 12 times as burdening. Mentions were summarized within the categories uncompleted administrative tasks (n = 7) and working inaccurately (n = 5). Since both categories (strain symptoms and consequences for work quality) have only one level of subcategories, the corresponding figures are presented in the supplemental material 1 (Figure S1.6, S1.7).

Networks of Work-Related Burdens

The rounded median over all categories’ frequencies is at 13. In total, 13 categories were mentioned more than 13 times. Thus, single-category code co-occurrence models were created for these categories, showing the networks for each category separately. Based on these networks, three multiple-category co-occurrence models were created: (1) In order to obtain a holistic picture of burdens related to strain symptoms, the categories physical symptoms, cognitive/mental symptoms and the general feeling of being exhausted/burdened are illustrated in a common network. (2) To create a network of the categories time pressure and travel between homes was decided, as both categories were mentioned reciprocal most frequently as co-occurred categories. (3) The network of additional tasks and mismatch of allocated and required time was created, as additional tasks were the category most frequently co-occurring within all single-category code co-occurrence models, and the category mismatch of allocated and required time had the highest co-occurrence rate (n = 44) relatively to the frequency of the category (n = 23). Figures of the multiple-category co-occurrence models are presented in the following section. The co-occurrence frequency of two categories is displayed on the connecting lines between them; the thickness of the lines indicates the relative frequency of co-occurrence. The direction of the arrow indicates the predominant causal relationship between two categories according to the participants’ reporting. If the arrow direction is not presented, the two categories predominantly co-occur without any causal relation. The single-category code co-occurrence models for those six categories, which were not included in the multiple-category co-occurrence models are outlined in the supplemental material 2 (Figure S2.1–Figure S2.5).

Network of Burdens Related to Strain Symptoms

Figure 8 shows the network of burdens related to strain symptoms. Cognitive/mental symptoms of strain were reported two times together with the feeling of being exhausted/burdened, both categories have not been mentioned in relation to physical symptoms.

Figure 8.

Network of burdens related to strain symptoms.

Emotional strain is the category most often mentioned to cause cognitive/mental symptoms (n = 10); in detail, suppressing emotions (n = 3), and suffering, dying, fear of patients/relatives (n = 3) are the subcategories most commonly reported to be causes for cognitive/mental symptoms. Emotional strain is also reported together with physical symptoms (n = 2) and one time in a causal relationship with feeling of being exhausted/burdened. The roster is mentioned most often to cause the feeling of being exhausted/burdened, mostly related to the subcategories split shifts (n = 4) and sequence of working days and days off (n = 3). The roster is mentioned once to cause cognitive/mental symptoms and physical symptoms. Strained postures, most commonly associated with stooped posture (n = 5) due to dressing changes are reported most frequently to cause physical symptoms, with no relations to other strain symptoms.

Network of Burdens Related to Time Pressure and Travel Between Homes

Figure 9 shows the network of burdens related to time pressure and travel between homes. Time pressure and travel between homes were reported ten times together. Traveling causes in six cases time pressure, mostly when it was related to the traffic situation (n = 3). The other way around, time pressure causes in one diary entry burdening aspects of traveling as the participants report risky driving behavior caused by time pressure.

Figure 9.

Network of burdens related to time pressure and travel between homes.

Additional tasks were reported most commonly to cause time pressure, especially related to an emergency/incident (n = 2) or unusual administrative tasks (n = 2). Traveling was most frequently reported together with cognitive/mental symptoms (n = 4). In three cases, burdening aspects of traveling cause cognitive/mental symptoms, predominantly due to risky driving behavior of other road users (n = 2). One participant reported that cognitive/mental symptoms lead to one’s own risky driving behavior due to the lack of concentration.

Network of Burdens Related to Additional Tasks and the Mismatch of Allocated and Required Time

Figure 10 shows the network of burdens related to additional tasks and the mismatch of allocated and required time. In nine storylines participants reported that additional tasks caused a mismatch of allocated and required time, mostly related to additional administrative tasks (n = 4) and additional tasks due to increased care needs of patients (n = 4).

Figure 10.

Network of burdens related to additional tasks and the mismatch of allocated and required time.

Additional tasks were reported 12 times to cause burdens due to a delay. Most frequently because of an emergency/incident (n = 4) and increased care needs of patients (n = 3). Burdens related with a high workload were reported in five diary entries to cause burdens because of the mismatch of allocated and required time. In an equal number of storylines, this was reported the other way around—the mismatch of allocated and required time are reported to cause time pressure.

Discussion

The findings revealed a complex picture of work-related burdens among home care workers. More than half of all reported burdens were related to work organization. Within the category of work organization, burdens due to the work process have the highest share, with additional tasks mentioned most frequently. This predominance is in accordance with the findings from Sjöberg et al. (2020), indicating that home care workers report more problems related to quantitative aspects than due to content-related ones. The common occurrence of additional tasks within the daily working routine was also found by Karlsson et al. (2020), as 47% of home care workers reported that clients often ask them to do tasks they are not paid for. However, the current study extends the understanding of burdens related to additional tasks. The majority of the additional tasks is not because of patients’ requests, but is administrative work. Moreover, the co-occurrence models show that additional tasks are a central node within the network of burdens. They were most frequently reported to cause burdens due to emotional strain, high workload, delay, the roster and the mismatch of allocated and required time. This may be the central key to explain the feeling of having unpredictable workdays found in previous studies among home care workers (Fjørtoft et al., 2020; Grasmo et al., 2021).

In this study, burdens related to the mismatch of allocated and required time were found to occur due to specific care tasks, needs of specific patients, and the high workload within one shift. Not even half of the mentions were related to additional tasks, indicating that the mismatch occurs mostly on a general basis and is inherent to the working routine in home care. Similarly, also Mojtahedzadeh, Rohwer et al., (2021) reported that the schedules are generally planned too tightly as staying longer as allocated with patients is unavoidable. In line with these results, Ruotsalainen et al. (2020) pointed out that the strict time schedule based on specific time units for each task creates problems on a practical level because a resource planning system does not know all the details home care workers have to do. In summary, this leads to the assumption, that the scheduling system does not encourage home care worker to work efficiently, but it constantly creates the feeling of being under time pressure and failing in keeping the schedule. As a consequence, home care worker were found to manipulate the timer system (Strandås et al., 2019), skip breaks (Mojtahedzadeh, Rohwer et al., 2021) and suppress the need to go to the toilet (Grasmo et al., 2021). Moreover, time pressure leads to unhealthy behavior, such as an increased consumption of sweets and forgetting to drink (Mojtahedzadeh, Rohwer et al., 2021). Research on routing and planning in home care is growing (Di Mascoloa et al., 2021). However, as the present results show, there is still a need for planning approaches that are not solely focused on efficiency and are developed participatively with caregivers.

Additionally, this study found that time pressure was related to various types of burdens but most frequently to traveling between homes. Focusing on this connection, Cœugnet et al. (2016) showed through on-trip observations that half of the work-related trips were performed under time pressure. They found that time pressure was related to time constraints as well as challenges and the uncertainties while being on the road. Thus, some pioneer home care services have switched from cars to bikes, so they can bypass traffic jams and avoid parking problems (Dorset HealthCare University, 2021). As weather and darkness were found to be most frequently mentioned as a burdening aspect related to traveling in this study, bicycling may alleviate burdens related to traffic and parking, but at the same time intensify others. Nevertheless, the results of the current study indicate that burdens due to traveling should gain more attention when looking at environmental strains, as it was mentioned four times more frequently compared to the participants’ workplace.

Audio entries indicate that burdens related to the work content are almost exclusively characterized by emotional strains, most frequently due to the patients’ dying, suffering, and fear. This predominance was also found in the study by Kim et al. (2013), showing that home care workers were most likely to be confronted with patients’ physical pain and sickness compared to other emotional strains. Moreover, Tsui et al. (2019) showed that patients’ death requires substantial emotional labor among home care workers and leads to a wide range of negative mental and physical outcomes. Thus, the results confirm that home care workers are in urgent need of further training in dealing with the suffering and dying of patients (Baik et al., 2021), as this is a frequently occurring and health impacting burden.

Unlike the study from Tsui et al. (2019), participants did not report emotional strains to cause physical symptoms of strain; rather, they exclusively associated physical strains with physical symptoms. Maybe this perception is slightly too simple as emotional dissonance was found to predict low back pain in home care workers (Elfering et al., 2017). Physical burdens are undoubtedly a unique set of challenges in home care (King et al., 2018), but the comparatively small share of reported burdens (5.5%) may suggest that this type of burden has been overestimated so far.

Complementary to the picture of work-related resources of home care workers, where social relationships were found to be the most important source for joyful moments (Gebhard et al., 2022), they have a subordinate role in the experience of burdens (6.4%). The most notable result in this category is the role of relatives, as burdens related to them were comparatively frequently reported to cause emotional strain. This result appears to be specific for home care and complements the results from Ris et al. (2019), showing that the effective collaboration between family caregivers and home care workers is not only crucial for the health of relatives, but also for the home care workers’ health.

However, there is still a lack of specific measures that address the particular mental and physical burdens of home care (Neumann et al., 2021). The present findings reinforce the call for the development of new approaches to workplace health promotion for home care workers (Grasmo et al., 2021) and specify the need with concrete starting points for interventions.

Strengths and Limitations

The greatest strength of this study is the methodological approach. Both, the data collection method and the analysis method were found to be valuable additions to the methodological toolkit in gerontological research. The main limitations of the study are related to the sample size and the convenience sampling, which may both have biased the results. Moreover, further quantitative analysis would have allowed even deeper insights.

Conclusion

Using audio diaries and moving beyond the binary qualitative-quantitative distinction reveals a more holistic picture of work-related burdens among home care workers. A deeper understanding of home care workers’ script of burdens provides an important starting point for workplace health promotion. Measures should address the most burdening nodes and focus on burdens that frequently occur in order to improve working conditions in home care efficiently.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for The Hidden Script of Work-Related Burdens in Home Care – A Cross Over Mixed Analysis of Audio Diaries by Doris Gebhard and Magdalena Wimmer in Journal of Applied Gerontology

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Julia Frank for her support related to the coding of the co-occurrence and the visualization of the data as part of her internship.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was financially supported by Verband der Ersatzkassen e. V. (vdek).

Ethical Approval: The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Technical University Munich (428/20 S-EB, 29 July 2020). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Doris Gebhard https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2984-3007

References

- Attride-Stirling J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. 10.1177/146879410100100307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baik D., Leung P., Sterling M., Russell D., Jordan L., Silva A., Masterson Creber R. (2021). Eliciting the educational needs and priorities of home care workers on end-of-life care for patients with heart failure using nominal group technique. Palliative Medicine, 35(5), 977–982. 10.1177/0269216321999963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N., Davis A., Rafaeli E. (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 579–616. 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cœugnet S., Forrierre J., Naveteur J., Dubreucq C., Anceaux F. (2016). Time pressure and regulations on hospital-in-the-home (HITH) nurses: An on-the-road study. Applied Ergonomics, 54(1), 110-119. 10.1016/j.apergo.2015.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contandriopoulos D., Stajduhar K., Sanders T., Carrier A., Bitschy A., Funk L. (2021). A realist review of the home care literature and its blind spots. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 28(4), 1–10. 10.1111/jep.13627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottingham M., Johnson A., Erickson R. (2018). “I can never Be too comfortable”: Race, gender, and emotion at the hospital bedside. Qualitative Health Research, 28(1), 145–158. 10.1177/1049732317737980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozier S., Cassell C. (2016). Methodological considerations in the use of audio diaries in work psychology: Adding to the qualitative toolkit. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89(2), 396–419. 10.1111/joop.12132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Mascoloa M., Martinez C., Espinousea M-L. (2021). Routing and scheduling in home health care: A literature survey and bibliometric analysis. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 158, Article 107255. 10.1016/j.cie.2021.107255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorset HealthCare University . (2021). Dorset’s district nurses get on their bikes . Dorset HealthCare University. https://www.dorsethealthcare.nhs.uk/about-us/news-events/press/dorsets-district-nurses-get-their-bikes [Google Scholar]

- Elfering A., Häfliger E., Celik Z., Grebner S. (2017). Lower back pain in nurses working in home care: Linked to work-family conflict, emotional dissonance, and appreciation? Psychology, Health & Medicine, 23(6), 733–740. 10.1080/13548506.2017.1417614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission & Social Protection Committee (2021). 2021 Long-Term Care Report Trends, challenges and opportunities in an ageing society . https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=24079&langId=en [Google Scholar]

- Fjørtoft A.-K., Oksholm T., Delmar C., Førland O., Alvsvåg H. (2020). Home-care nurses’ distinctive work: A discourse analysis of what takes precedence in changing healthcare services. Nursing Inquiry, 28(1), Article e12375. 10.1111/nin.12375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhard D., Neumann J., Wimmer M., Mess F. (2022). The second side of the coin—resilience, meaningfulness and joyful moments in home health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), Article 3836. 10.3390/ijerph19073836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health . (Ed.) (2021). Handbuch Gefährdungsbeurteilung [Risk assessment manual]. 10.21934/baua:fachbuch20210127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gobo G., Fielding N., La Rocca G., van der Vaart W. (2021). Merged methods: A rationale for full integration . Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Grasmo S., Liaset I., Redzovic S. (2021). Home care workers’ experiences of work conditions related to their occupational health: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 962. 10.1186/s12913-021-06941-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock J., Onwuegbuzie A. (2020). Developing mixed methods crossover analysis approaches. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 14(1), 63–83. 10.1177/1558689819841782 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson N., Markkanen P., Kriebel D., Galligan C., Quinn M. (2020). “That’s not my job”: A mixed methods study of challenging client behaviors, boundaries, and home care aide occupational safety and health. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 63(4), 368–378. 10.1002/ajim.23082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I.-H., Noh S., Muntaner C. (2013). Emotional demands and the risks of depression among homecare workers in the USA. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 86(6), 635–644. 10.1007/s00420-012-0789-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King E., Holliday P., Andrews G. (2018). Care challenges in the bathroom: The views of professional care providers working in clients' homes. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 37(4), 493–515. 10.1177/0733464816649278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayring P. (2015). Qualitative inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und techniken [qualitative content analysis. Basics and techniques] (12., überarbeitete Aufl.). Beltz. [Google Scholar]

- Mojtahedzadeh N., Rohwer E., Neumann F., Nienhaus A., Augustin M., Zyriax B.-C., Harth V., Mache S. (2021). The health behaviour of German outpatient caregivers in relation to their working conditions: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), Article 5942. 10.3390/ijerph18115942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtahedzadeh N., Wirth T., Nienhaus A., Harth V., Mache S. (2021). Job demands, resources and strains of outpatient caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), Article 3684. 10.3390/ijerph18073684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir T. (2017). Measuring social protection for long-term care. OECD Health Working Papers (93). OECD Publishing. 10.1787/a411500a-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann F. A., Rohwer E., Mojtahedzadeh N., Makarova N., Nienhaus A., Harth V., Augustin M., Mache S., Zyriax B.-C. (2021). Workplace health promotion and COVID-19 support measures in outpatient care services in Germany: A quantitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), Article 12119. 10.3390/ijerph182212119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly K., Ramanaik S., Story W., Gnanaselvam N., Baker K., Cunningham T., Mukherjee A., Pujar A. (2022). Audio diaries: A novel method for water, sanitation, and hygiene-related maternal stress research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21(1), 1-10. 10.1177/16094069211073222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otto A., Bischoff L., Wollesen B. (2019). Work-related burdens and requirements for health promotion programs for nursing staff in different care settings: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), Article 3586. 10.3390/ijerph16193586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn M., Markkanen P., Galligan C., Sama S., Lindberg J., Edward M. (2021). Healthy aging requires a healthy home care workforce: The occupational safety and health of home care aides. Current Environmental Health Reports, 8(2), 235–244. 10.1007/s40572-021-00315-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ris I., Schnepp W., Mahrer-Imhof R. (2019). An integrative review on family caregivers’ involvement in care of home‐dwelling elderly. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(3), Article e95–e111. 10.1111/hsc.12663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruotsalainen S., Jantunen S., Sinervo T. (2020). Which factors are related to Finnish home care workers’ job satisfaction, stress, psychological distress and perceived quality of care? - a mixed method study. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), Article 896. 10.1186/s12913-020-05733-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöberg A., Pettersson-Strömbäck A., Sahlén K.-G., Lindholm L., Norström F. (2020). The burden of high workload on the health-related quality of life among home care workers in Northern Sweden. International Achieves Occupational and Environmental Health, 93(6), 747–764. 10.1007/s00420-020-01530-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandås M., Wackerhausen S., Bondas T. (2019). Gaming the system to care for patients: A focused ethnography in Norwegian public home care. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 121–121. 10.1186/s12913-019-3950-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timonen V., Lolich L. (2019). “The poor carer”: Ambivalent social construction of the home care worker in elder care services. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 62(7), 728–748. 10.1080/01634372.2019.1640334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treviranus F., Mojtahedzadeh N., Harth V., Mache S. (2021). Psychische Belastungsfaktoren und Ressourcen in der ambulanten Pflege [Psychological demands and resources in home care]. Zentralblatt für Arbeitsmedizin, Arbeitsschutz und Ergonomie, 71(1), 32-37. 10.1007/s40664-020-00403-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui E., Franzosa E., Cribbs K., Baron S. (2019). Home care workers’ experiences of client death and disenfranchised grief. Qualitative Health Research, 29(3), 382–392. 10.1177/1049732318800461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistic (2021). Occupational outlook handbook, home health and personal care aides . https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/home-health-aides-and-personal-care-aides.htm [Google Scholar]

- Van Eenooa L., van der Roestb H., Onderc G., Finne-Soverid H., Garms-Homolovae V., Palmi V., Draisma S., Hout H. V., Declercqa A. (2018). Organizational home care models across europe: A cross sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 77(1), 39-45. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERBI Software (2019. a). MAXQDA 2020 [computer software]. VERBI Software. [Google Scholar]

- VERBI Software (2019. b). MAXQDA 2020 manual . https://www.maxqda.com/download/manuals/MAX2020-Online-Manual-Complete-EN.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Williamson I., Leeming D., Lyttle S., Johnson S. (2015). Evaluating the audio-diary method in qualitative research. Qualitative Research Journal, 15(1), 20–34. 10.1108/QRJ-04-2014-0014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material for The Hidden Script of Work-Related Burdens in Home Care – A Cross Over Mixed Analysis of Audio Diaries by Doris Gebhard and Magdalena Wimmer in Journal of Applied Gerontology