Abstract

The word “pox” indicated, during the late 15th century, a disease characterized by eruptive sores. When an outbreak of syphilis began in Europe during that time, it was called by many names, including the French term “la grosse verole” (“the great pox”), to distinguish it from smallpox, which was termed “la petite verole” (“the small pox”). Chickenpox was initially confused with smallpox until 1767, when the English physician William Heberden (1710-1801) provided a detailed description of chickenpox, differentiating it from smallpox.

The cowpox virus was used by Edward Jenner (1749-1823) to develop a successful vaccine against smallpox. He devised the term “variolae vaccinae” (“smallpox of the cow”) to denote cowpox. Jenner's pioneering work on a smallpox vaccine has led to the eradication of this disease and opened the way to preventing other infectious diseases, such as monkeypox, a poxvirus that is closely related to smallpox and that is currently infecting persons around the world.

This contribution tells the stories behind the names of the various “poxes” that have infected humans: the great pox (syphilis), smallpox, chickenpox, cowpox, and monkeypox.

These infectious diseases not only share a common “pox” nomenclature, but are also closely interconnected in medical history.

Poxes great and small: The stories behind their names

The recent monkeypox outbreak has caught the world by surprise, and during the first half of 2022, more than 6,000 persons across multiple countries were infected by the virus.1 The outbreak has also given our simian friends widespread recognition in the news media because monkeypox was first identified in 1958 among laboratory monkeys.2 Despite being named “monkeypox,” the source of the disease remains unknown.2 African rodents and nonhuman primates, like monkeys, might harbor the virus and infect people. Person-to-person transmission can then follow.

Names of diseases often have historic, cultural, and political significance. Thus, the World Health Organization (WHO) is planning to change the name of the monkeypox virus over concerns that the term “monkeypox” is discriminating and stigmatizing to Africa and its people.3

Whatever we choose to call it, the current monkeypox outbreak brings to mind distant memories of a far deadlier poxvirus that was eradicated more than 40 years ago: smallpox. Like monkeypox, the name “smallpox” has a story behind it. This contribution tells that story along with those of the other “poxes” that can infect people: the great pox (syphilis), chickenpox, and cowpox.

These infectious diseases do not all share a common pathogen. Monkeypox, smallpox, and cowpox are caused by orthopoxviruses, whereas syphilis is a bacterial disease (Treponema pallidum) and chickenpox is caused by varicella zoster virus. Nonetheless, as will be seen in this contribution, these poxes are all interconnected by their “pox” nomenclature and in medical history.

The word “pox” and its etymology

For centuries, the word “pox” generated images of fear, sickness, and death because it denoted the rapidly spreading infectious diseases of syphilis and smallpox. William Shakespeare (1564-1616) used it as an insult in his play The Tempest (Act 1, scene 1):

A pox o’ your throat, you bawling, blasphemous, incharitable dog!4

During the late 15th century, the term “pox” described a disease characterized by eruptive sores.5 It was originally spelled as “pockes,” the plural of “pocke” (similar to “pock”) and meant a pustule, blister, or ulcer on the skin.

Similar terms to pox that were used in those times included:

-

1)

The German terms “blattern” or “plattern”

-

2)

The word “pustule,” late 14th century, from the Old French “pustule” and Latin “pustula,” meaning blister or pimple.6

The word “variola” was introduced by Marius Aventicensis (532-596), the Bishop of Aventicum, the capital of Roman Switzerland. He used it to describe an epidemic that afflicted Gaul and Italy in 570.7 The term comes from the diminutive of the Latin word “varius” meaning “changing” or “various,” in this case indicating “speckled” or “spotted.”8

The great pox and smallpox

When an outbreak of syphilis struck Europe during the 1490s, it was called by many names, such as the “French disease” (morbus gallicus) because it appeared during the siege of Naples by troops of Charles VIII (1470-1498) of France. Other, more medically related synonyms for syphilis included “posen plattern” and “bosen blattern,” both meaning “bad pox,” “malatia delle cattive pustule” (“disease of the bad pox”), and the French term “grosse verole” (great pox) (Figure. 1) to distinguish it from “petite verole,” or smallpox (Figure. 2).9

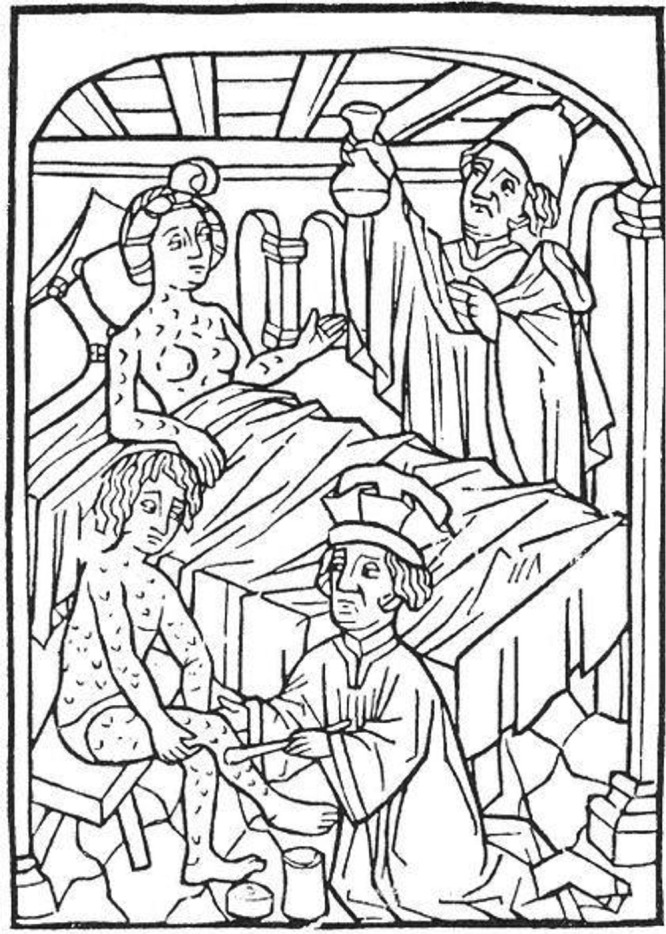

Fig. 1.

Syphilis treatment. Urine examination and treatment with ointments (mercury), Vienna 1497-1498. Woodcut by Bartholomaus Steber (15th century to 1506). Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

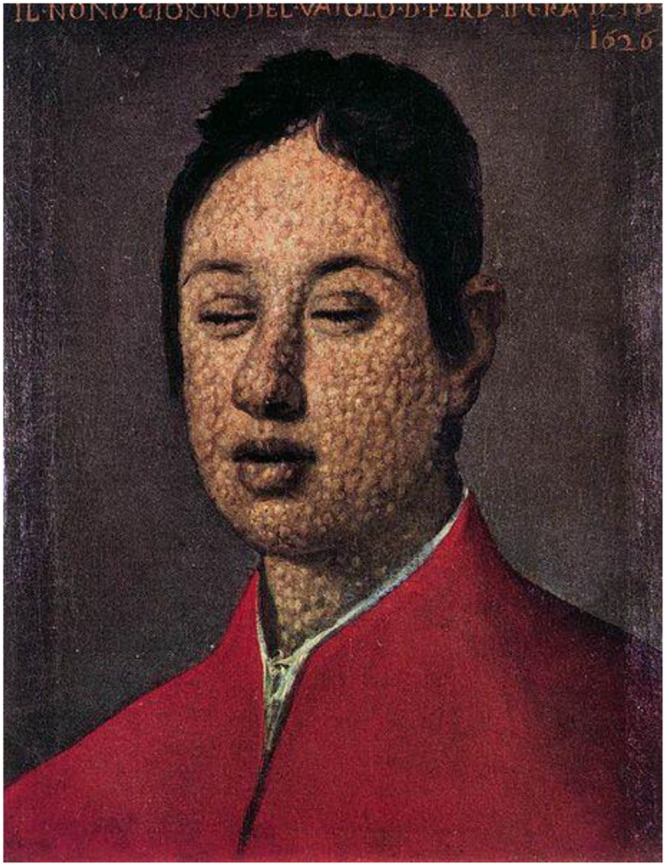

Fig. 2.

Portrait of Fernando II de Medici (1610-1670). Oil on canvas, 1626, by Justus Sustermans (1597-1681). Wikimedia Commons. Public domain. The painting was made on the ninth day of Fernando II's smallpox infection, showing a full eruption of the disease. Fernando II survived his illness and became grand duke of Tuscany, Italy.

The name “syphilis” comes from the Latin poem Syphilis sive morbus Gallicus written in 1530 by the Italian poet Hieronymous Fracatorius (1478-1553). The poetic verses describe this dreadful plague as something sent by the vengeful god, Apollo, to strike down the mythical shepherd named Syphilis. The term syphilis appears in the essays of Desiderius Erasmus, a Dutch philosopher and Catholic theologian (1466-1536).10 Daniel Turner (1667-1741), a London physician who published the first English language textbook on dermatology in 1714, was the first English medical author to use the term; however, the word syphilis was not in general use to describe the disease until the early 19th century.10 Until that time, it was known as the French disease, the French pox, the Spanish pox, or simply “the pox.”10

As mentioned, the term smallpox was derived from the French words “petite verole.” Variola was used to denote smallpox during the late 1700s and after, especially with the introduction of Edward Jenner's (1749-1823) cowpox vaccine and his use of the term variolae vaccinae (“smallpox of the cow”) to describe it. The German physician Rudolph Augustin Vogel (1724-1774) used the term “variolae” in 1757.11

Chickenpox

Chickenpox was confused with smallpox until 1767, when the English physician William Heberden (1710-1801) published his paper “On the Chicken-pox,” in which he clinically distinguished the two infections.12 The name chickenpox was used by the English physician Richard Morton (1637-1698), who characterized it as a mild form of smallpox.12 There are several theories about the origin of the term chickenpox. One theory, suggested by the British physician Thomas Fuller (1654-1734) in 1730, is that the lesions of chickenpox looked as if a “Child had been picked by the Bills of chickens.”13 In the dictionary of the English lexicographer, Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), it is mentioned that chickenpox is so called “from its being of no great danger.”13 The Latin term “varicella” is an irregular diminutive of the word variola8 and is believed to have been used during the 18th century.14

Cowpox

Cowpox was a term used in the late 1700s to denote a disease of the teats and udders of cows that infected milkmaids; it was described by the British physician Edward Jenner in 1798 in his book An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae.15 Jenner had heard rumors that dairy maids who had been infected with cowpox were not capable of having smallpox. He put this theory to the test by inoculating patients with cowpox and proving that this procedure prevented smallpox. Jenner used the term variolae vaccinae (smallpox of the cows) to denote cowpox, and his procedure became known as vaccination from the Latin term vaccinus (“from cows).”16

Jenner's vaccine helped to eradicate smallpox, one of humanity's most devastating diseases. It also opened the way to the development of other vaccines to prevent infectious diseases.

Conclusions

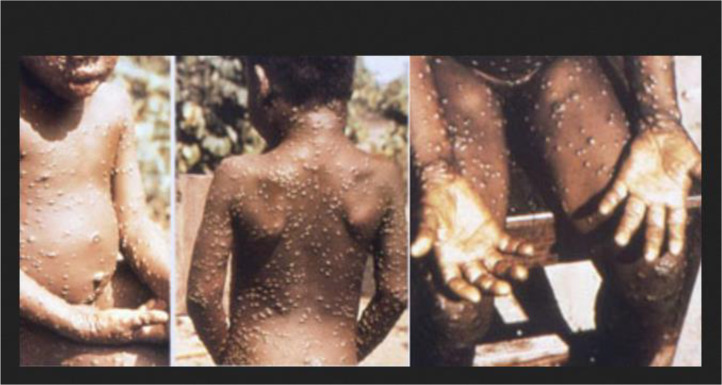

The surprise monkeypox ( Figure 3 ) outbreak of 2022 sent physicians around the world scrambling back to medical textbooks to review the cutaneous manifestations of this poxvirus infection. The skin eruption is an important clinical finding for the diagnosis of monkeypox as it was for the diagnosis of smallpox years ago and for differentiating smallpox from syphilis. Both smallpox and syphilis spread death and misery to their many unfortunate victims.

Fig. 3.

An image of the rash of monkeypox. October 15, 2017. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Cowpox, another poxvirus, became a gift to humanity when Jenner used it to develop a successful vaccine against smallpox. We are fortunate to live today in a world that is free of the ravages of smallpox and when other vaccines, anti-viral drugs, and antibiotics are available to prevent and treat syphilis, chickenpox, monkeypox, and a whole array of other pathogens.

The WHO is concerned that we do not use the monkeypox outbreak to discriminate against a continent or to stigmatize a particular demographic group. Infectious diseases, WHO reminds us, do not discriminate against people, and neither should we. Hopefully, if governments, physicians, and public health officials work together, the 2022 monkeypox epidemic will speedily be brought under control.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2022. Multi-country outbreak of monkeypox, external situation report.https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/multi-country-outbreak-of-monkeypox–external-situation-report–1–6-july-2022 #1 –6 JulyEdition 1. Available at. Accessed July 24, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About monkeypox. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/about.html. Accessed July 24, 2022.

- 3.Advisory Board. Why WHO wants to rename monkeypox. Available at: https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/2022/06/16/renaming-monkeypox. Accessed July 24, 2022.

- 4.Folger Shakespeare Library. The Tempest: Act 1, scene 1. Available at: https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/the-tempest/read/1/1 . Accessed April 20, 2023.

- 5.Online Etymology Dictionary. Pox. Available at: https://www.etymonline.com/word/pox. Accessed July 31, 2022.

- 6.Online Etymology Dictionary. Pustule. Available at: https://www.etymonline.com/word/pustule. Accessed July 31, 2022.

- 7.Wikipedia. Marius Aventicensis. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marius_Aventicensis. Accessed July 31, 2022.

- 8.Online Etymology Dictionary. Variola. Available at: https://www.etymonline.com/word/variola. Accessed July 31, 2022.

- 9.Tagarelli A, Tagarelli G, Lagonia P, Piro A. A brief history of syphilis by its synonyms. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2011;19:228–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frith J. Syphilis - its early history and treatment until penicillin, and the debate on its origins. J Mil Veterans Health. 2022;20:49–56. History. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogel RA. Neue Medicinische Bibliothek. Vol. 4. Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck; 1758:87.

- 12.Heberden W. On the Chicken-pox. Medical transactions published by the Royal College of Physicians in London. Vol. 1. London, England: Printed for J. Dodsley, P. Embly, and Leigh and Sotheby; 1768:427-436.

- 13.Aronson J. Chickenpox. BMJ. 2000;321:682. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7262.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galetta KM, Gilden D. Zeroing in on zoster: a tale of many disorders produced by one virus. J Neurol Sci. 2015;358:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wikipedia. Edward Jenner. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Jenner. Accessed August 1, 2022.

- 16.Online Etymology Dictionary. Vaccination. Available at: https://www.etymonline.com/word/vaccination. Accessed August 1, 2022.