Abstract

Background

The gold-standard method for establishing a microbiological diagnosis of COVID-19 is reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). This study aimed to evaluate the accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of a set of clinical-radiological criteria for COVID-19 screening in patients with severe acute respiratory failure (SARF) admitted to intensive care units (ICUs), using reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as the reference standard.

Methods

Diagnostic accuracy study including a historical cohort of 1009 patients consecutively admitted to ICUs across six hospitals in Curitiba (Brazil) from March to September, 2020. The sample was stratified into groups by the strength of suspicion for COVID-19 (strong versus weak) using parameters based on three clinical and radiological (chest computed tomography) criteria. The diagnosis of COVID-19 was confirmed by RT-PCR (referent).

Results

With respect to RT-PCR, the proposed criteria had 98.5% (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 97.5–99.5%) sensitivity, 70% (95% CI 65.8–74.2%) specificity, 85.5% (95% CI 83.4–87.7%) accuracy, PPV of 79.7% (95% CI 76.6–82.7%) and NPV of 97.6% (95% CI 95.9–99.2%). Similar performance was observed when evaluated in the subgroups of patients admitted with mild/moderate respiratory disfunction, and severe respiratory disfunction.

Conclusion

The proposed set of clinical-radiological criteria were accurate in identifying patients with strong versus weak suspicion for COVID-19 and had high sensitivity and considerable specificity with respect to RT-PCR. These criteria may be useful for screening COVID-19 in patients presenting with SARF.

Keywords: COVID-19 testing, Intensive care units, Tomography, Sensitivity and specificity, COVID-19 testing, Mass screening

Background

The SARS-CoV-2 emerged in late 2019 and has spread globally. The clinical presentation of patients infected with this virus may range from lack of symptoms to severe acute respiratory failure (SARF), culminating in admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) [1].

During a pandemic, viruses transmit at a high rate, infecting a large number of individuals and increasing the risk of disease, including in its most severe forms. Therefore, proper screening and knowledge of the clinical and epidemiological profile of infected individuals can contribute to timely actions and implementation of treatments that minimize the impact of the disease on individual and population levels [2]. Since the beginning of the health crisis due to COVID-19, the Brazilian health care system has faced challenges in discriminating patients with COVID-19 from those with other causes of SARF. Equally challenging has been the identification of patients who meet the criteria for severe disease. With the high demand and limited availability of beds, it is fundamental to properly guide those patients requiring high-level care to admission to ICUs instead of general medical wards.

The clinical manifestations of COVID-19 are also commonly found in several other diseases, e.g., SARF due to other viruses, bacterial pulmonary infections, and decompensated chronic pulmonary or heart diseases, among others [3]. Therefore, establishing an accurate diagnosis is crucial, given the importance of each disease involving specific therapeutic decisions and, in the context of a pandemic, the need for the adoption of appropriate health measures.

The gold-standard method for establishing a microbiological diagnosis of COVID-19 is reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). However, the low sensitivity of RT-PCR tests available at the beginning of the pandemic has resulted in a high number of false-negative results, a condition that has favored the community spread of the virus [2, 4, 5]. Also, this method is not widely available in Brazil, further limiting its availability considering the exponential spread of the disease—and even when the test is available, results may be delayed. These complications have also been reported in other (underdeveloped and developed) countries [6].

In this context, this study aimed to evaluate the accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of a set of clinical-radiological criteria for screening of COVID-19 in patients with SARF admitted to ICUs, using RT-PCR as the reference standard for the diagnosis of the disease.

Methods

Diagnostic accuracy study using data from a historical cohort of adult patients consecutively admitted to ICUs across six hospitals (two public and four private) in the city of Curitiba (Paraná, Brazil) due to SARF and suspected COVID-19 between March 11 and September 20, 2020.

The data were retrieved from the database of the Center for Studies and Research in Intensive Care Medicine (CEPETI), which encompasses sociodemographic and clinical information regarding patients' admission and outcome across all six ICUs included in the study. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Instituto de Neurologia de Curitiba under protocol number 3.000.353 on November 05th, 2018 (ID: CAAE 98,099,918.2.0000.5227; project title: Epidemiological analysis of patients hospitalized in ICUs in Curitiba-Paraná). The requirement for informed consent was waived, given the noninterventional design of the study and the fact that the data were collected from clinical records and without contact with the participants. All research procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee on human experimentation and the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2013. The study findings are reported according to STARD 2015 guidelines [7].

Data of all consecutive patients with suspected COVID-19 admitted to the participating ICUs with moderate to severe disease (as per the WHO Clinical Progression Scale) [8] during the study period were reviewed for identification of the level of suspicion (strong versus weak) of COVID-19 according to the proposed set of clinical-radiological criteria. Patients who fulfilled all three criteria listed below were classified as having strong suspicion for COVID-19:

Presence of one or more flu-like symptoms (fever, runny nose, sore throat, or cough).

Presence of two or more items in the quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) [9], i.e., systolic blood pressure ≤ 100 mmHg, respiratory rate ≥ 22 bpm, reduced level of consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale < 15), and oxygen pulse saturation ≤ 93%.

Chest computed tomography (CT) scanning obtained within the first 24 h of ICU admission and with a strong suspicion for COVID-19, defined as the presence of multifocal peripheral lesions distributed across both lungs and ground-glass infiltrates in more than 25% of the lung area, as described in the literature [10].

Patients not meeting all three criteria were classified as having weak suspicion for COVID-19. All patients were allocated into one of the two groups of suspicion for COVID-19 defined by the systematically applied set of clinical-radiological criteria (strong versus weak level of suspicion) and, within the first 24 h of admission, underwent nasopharyngeal swab collection for RT-PCR test for the detection of SARS-CoV-2.

We excluded from the analysis those patients without any of the three criteria described above or in whom the criteria were not evaluated and those with inconclusive or missing RT-PCR results.

The group of patients identified as having strong suspicion for COVID-19 was compared with the group with a weak suspicion for COVID-19 with respect to the following variables: age, sex, reduced level of consciousness according to the Glasgow Coma Scale, need for hemodynamic support with volume and/or vasoactive drug, need for invasive ventilatory support on ICU admission, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) severity score, SOFA score in the first 24 h of ICU admission, reason for hospitalization, length of ICU stay, limitation of advanced life support, and mortality.

The accuracy of the screening method for COVID-19 based on the proposed set of clinical-radiological criteria (strong versus weak suspicion) was evaluated against the result of the RT-PCR (positive versus negative), which is the gold-standard method for diagnosis of COVID-19 [11].

The physicians analyzing the clinical-radiological criteria had no access to the results of laboratory tests confirming the diagnosis of COVID-19. Similarly, the laboratory team that ran the RT-PCR tests for detection of SARS-CoV-2 had no access to the patients' clinical data and were, thus, unaware of the patients' classification according to the clinical-radiological criteria.

Statistical analysis

We included in the analysis only those patients with complete data regarding the parameters evaluated in the set of clinical-radiological criteria and with RT-PCR results for the detection of SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, imputation for missing data was not required.

To compare the diagnostic accuracy of the set of clinical-radiological criteria with the RT-PCR result (reference standard), we calculated the following measures of diagnostic accuracy: sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, probability of false positive and false negative, accuracy (and respective 95% confidence intervals [95% CIs]), and likelihood values for positive and negative tests. The same analysis was also performed separately for the subgroup of patients with mild/moderate respiratory dysfunction and severe respiratory dysfunction, to assess the tool’s performance in different poles of respiratory dysfunction. In this context, patients with severe respiratory dysfunction were considered those admitted to the ICU using invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation, and/or those who scored three or more in the APACHE II respiratory parameters of the first 24 h in the ICU stay (respiratory rate ≥ 35 or < 5, arterial-alveolar gradient ≥ 350 mmHg in inspired oxygen fraction ≥ 0.5, or oxygen partial pressure ≤ 60 mmHg in inspired oxygen fraction < 0.5). The others were considered as mild/moderate respiratory dysfunction.

As an exploratory analysis, for those patients with results that were true negative, false positive, and false negative according to the set of clinical-radiological criteria, we grouped the reasons for hospitalization (defined up to 24 h after admission) and described them using absolute frequencies and percentages.

The association of dichotomous variables (sex, mortality, requirement of hemodynamic and/or invasive ventilatory support at ICU admission) between the groups (strong versus weak suspicion) was presented as absolute and percentage frequencies and compared using Fisher's exact test. The results of the Glasgow Coma Scale on admission were dichotomized, and scores ≤ 14 indicated a reduced level of consciousness while a score of 15 indicated a normal level of consciousness; these variables were described as absolute frequencies and percentages, and the differences between groups were assessed using Fisher's exact test.

The normality of the distribution was verified visually using box plots, with skewness and kurtosis assessments, and with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The age of the patients, given their normal distribution, was described as means and standard deviations and compared between groups using Student's t test for independent samples. The length of ICU stay, which was not normally distributed, and APACHE II and SOFA scores and the Glasgow Coma Scale were described as medians and interquartile ranges and compared between groups using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test. For the evaluation of the influence of the APACHE II score on the proposed set of clinical-radiological criteria, the scores were further adjusted for age, analyzed using a multiple logistic regression model, and presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals.

The level of statistical significance was set at 5%, and the data were analyzed using Stata, version 15.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

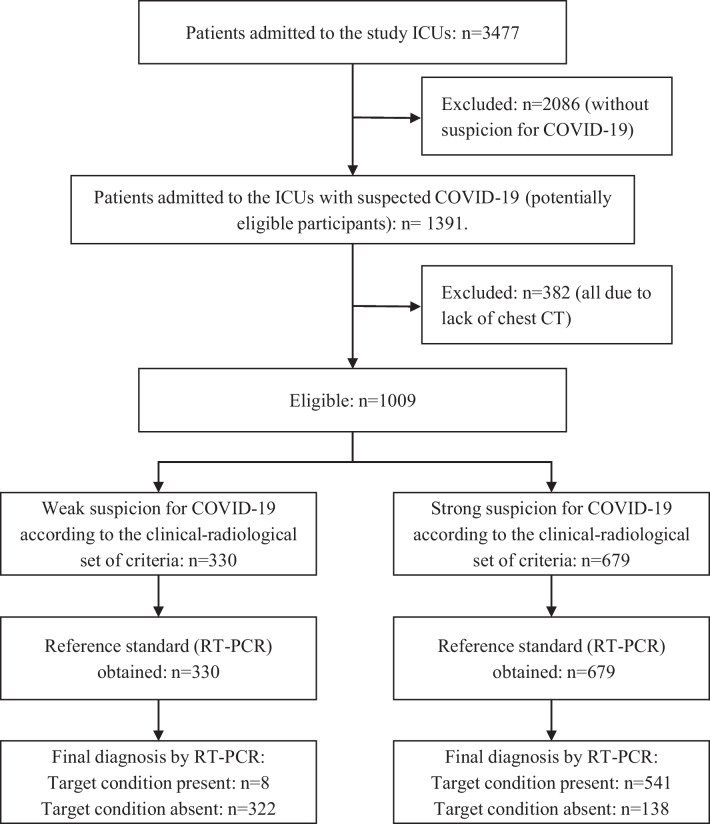

During the study period, 3477 patients were admitted to the participating ICUs, of whom 1391 were suspected of having COVID-19. Of these, 382 were excluded as they had not been evaluated with chest CT scanning, resulting in 1009 eligible patients who fulfilled all the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart with the process of selection of the study sample. Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; CT, Computed tomography; RT-PCR, Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Of the 1009 patients included in the analysis, 679 (67.3%) and 330 (32.7%) were identified as having, respectively, a strong and weak suspicion for COVID-19 according to the set of clinical-radiological criteria. Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics associated with hospitalization and outcomes in each group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of ICU patients with SARF and suspicion for COVID-19, stratified by the clinical-radiological criteria

| Characteristics | Total (n = 1009) |

Strong Suspicion (n = 679) |

Weak Suspicion (n = 330) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)—mean (SD) | 63.4 (17.5) | 61.5 (16.5) | 67.1 (18.2) | ≤ 0.001f |

| Male sex—n (%) | 554 (54.9) | 392 (57.7) | 162 (49.1) | 0.010g |

| Clinical condition at ICU admission | ||||

| Reduced level of consciousness—n (%) a | 299 (32.6) | 175 (28.8) | 124 (39.9) | ≤ 0.001g |

| Need for hemodynamic support—n (%) a | 257 (28) | 165 (27.2) | 92 (29.6) | 0.485g |

| Need for invasive ventilatory support—n (%) a | 176 (19.2) | 104 (17.1) | 72 (23.2) | 0.033g |

| Severity scores at ICU admission | ||||

| APACHE II score—median (IQR) b | 12 (7–18) | 11 (6–17) | 13 (9–18) | ≤ 0.001h |

| SOFA score – median (IQR) c | 3 (2–6) | 3 (2–6) | 3 (2–6) | 0.365h |

| Severe respiratory disfunction at ICU admission—n (%) d | 468 (46.4) | 318 (46.8) | 150 (45.5) | 0.687g |

| Outcome | ||||

| Length of ICU stay (days)—median (IQR) | 4.0 (1.9–8.3) | 4.5 (2.2–9.3) | 3.1 (1.3–5.7) | ≤ 0.001h |

| Limitation of life-sustaining treatments (no increment or withdrawal)—n (%) e | 66 (6.6) | 43 (6.3) | 23 (7) | 0.685g |

| Death—n (%) | 246 (24.4) | 191 (28.1) | 55 (16.7) | ≤ 0.001g |

Clinical characteristics associated with hospitalization and outcomes in patients admitted to intensive care units with severe acute respiratory failure and suspicion for COVID-19, stratified by the strength of the suspicion according to the proposed set of clinical-radiological criteria

ICU intensive care unit, APACHE II Acute Physiology and Chronic Health disease Classification System II, SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range

a91 missing data in the total sample, 71 in the strong suspicion group, and 19 in the weak suspicion group

b79 missing data in the total sample, all in the strong suspicion group

c428 missing data in the total sample, 316 in the strong suspicion group, and 112 in the weak suspicion group

dpatients with severe respiratory dysfunction were considered those admitted to the ICU using invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation, and/or those who scored three or more in the APACHE II respiratory parameters of the first 24 h in the ICU stay (respiratory rate ≥ 35 or < 5, arterial-alveolar gradient ≥ 350 mmHg in inspired oxygen fraction ≥ 0.5, or oxygen partial pressure ≤ 60 mmHg in inspired oxygen fraction < 0.5. The others were considered as mild/moderate respiratory dysfunction)

eThree patients who progressed with brain death were not considered in the analysis, including one who was in the strong suspicion group and two in the weak suspicion group

fSignificance of Student's t test for independent samples

gSignificance of Fischer's exact test

hSignificance of nonparametric Mann–Whitney test

The group of patients with a strong versus that with a weak suspicion for COVID-19 had more men and individuals older than 60 years, were less frequently identified as having reduced level of consciousness or requiring invasive ventilatory support at ICU admission. This group of patients also had a lower median APACHE II score. However, after adjustment of the APACHE II scores by age, the difference between groups was no longer significant (OR 0.993, 95% CI 0.976–1.01). The median length of ICU stay and the percentage of deaths were also higher in the strong versus weak suspicion group.

The time from symptom onset to ICU admission among patients with a positive RT-PCR result was 6.8 ± 4.3 days. Table 2 shows the results of the classification by the proposed set of clinical-radiological criteria compared with the results of the RT-PCR tests.

Table 2.

Cross tabulation of the results of the proposed set of clinical-radiological criteria versus the RT-PCR, considering the total sample

| Total sample | RT-PCR (reference standard) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |||

| Classification by the clinical-radiological criteria | Strong Suspicion | 541 (53.6%) | 138 (13.7%) | 679 (67.3%) |

PPVa 79.7% (76.6–82.7%) |

| Weak Suspicion | 8 (0.8%) | 322 (31.9%) | 330 (32.7%) |

NPVa 97.6% (95.9–99.2%) |

|

| Total | 549 (54.4%) | 460 (45.6%) | 1009 (100%) | ||

|

Sensitivitya 98.5% (97.5–99.5%) |

Specificitya 70% (65.8–74.2%) |

Accuracya 85.5% (83.4–87.7%) |

|||

RT-PCR Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value

aValues presented with their respective 95% confidence intervals

Likelihood of a positive test: 3.28; likelihood of a negative test: 0.02

The proposed set of clinical-radiological criteria had high sensitivity (98.5%, 95% CI 97.5–99.5%) and comparatively lower specificity (70%, 95% CI 65.8–74.2%) to identify patients with a diagnosis of COVID-19 confirmed by RT-PCR. The probabilities of a false-positive and a false-negative result by the set of criteria were 30% (95% CI 25.8–34.2%) and 1.5% (95% CI 0.5–2.5%), respectively, and the positive and negative predictive values were 79.7% (95% CI 76.6–82.7%) and 97.6% (95% CI 95.9–99.2%), respectively. The proposed set of criteria had an accuracy of 85.5% (95% CI 83.4–87.7%) (Table 2). Similar performance of the set of clinical-radiological criteria was observed when evaluated in the subgroups of patients hospitalized with mild/moderate respiratory disfunction (Table 3) and severe respiratory disfunction (Table 4).

Table 3.

Cross tabulation of the results of the proposed set of clinical-radiological criteria versus the RT-PCR, considering the subgroup of patients with mild/moderate respiratory disfunction at ICU admission

| Subgroup of patients with mild/moderate respiratory disfunction | RT-PCR (reference standard) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |||

| Classification by the clinical-radiological criteria | Strong Suspicion | 295 (54.5%) | 66 (12.2%) | 361 (66.7%) |

PPVa 81.7% (77.7–85.7%) |

| Weak Suspicion | 5 (0.9%) | 175 (32.3%) | 180 (33.3%) |

NPVa 97.2% (94.8–99.6%) |

|

| Total | 300 (55.5%) | 241 (44.5%) | 541 (100%) | ||

|

Sensitivity 98.3% (96.9–99.8%) |

Specificitya 72.6% (67–78.2%) |

Accuracya 86.9% (84–89.7%) |

|||

RT-PCR Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value

aValues presented with their respective 95% confidence intervals

Likelihood of a positive test: 3.59; likelihood of a negative test: 0.02

Table 4.

Cross tabulation of the results of the proposed set of clinical-radiological criteria versus the RT-PCR, considering the subgroup of patients with severe respiratory disfunction at ICU admission

| Subgroup of patients with severe respiratory disfunction | RT-PCR (reference standard) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |||

| Classification by the clinical-radiological criteria | Strong Suspicion | 246 (52.6%) | 72 (15.4%) | 318 (67.9%) |

PPVa 77.4% (72.8–82%) |

| Weak Suspicion | 3 (0.6%) | 147 (31.4%) | 150 (32.1%) |

NPVa 98% (95.8–99.9%) |

|

| Total | 249 (53.2%) | 219 (46.8%) | 468 (100%) | ||

|

Sensitivitya 98.8% (97.4–99.9%) |

Specificitya 67.1% (60.9–73.3%) |

Accuracya 84.0% (80.7–87.3%) |

|||

RT-PCR Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value

aValues presented with their respective 95% confidence intervals

Likelihood of a positive test: 3.01; likelihood of a negative test: 0.02

The proportion of confirmed COVID-19 diagnoses by RT-PCR was also not significantly different between those with mild/moderate respiratory disfunction (55.5% positive RT-PCR), and severe respiratory disfunction (53.2% positive RT-PCR) (p = 0.486).

Table 5 shows the reasons for ICU admission among patients with false-positive and false-negative results, as well as those patients with a true negative diagnosis, which can lead to diagnoses other than COVID-19.

Table 5.

Frequency of reasons for hospitalization according to the proposed set of clinical-radiological criteria

| Reasons for ICU admission, defined up to 24 h from admission | True negative n = 322 |

False positive n = 138 |

False negative n = 8 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary disease—n (%) | 249 (77.3a) | 130 (94.2a) | 4 (50a) |

| Pneumonia or sepsis of pulmonary source—n (%) | 145 (58.2b) | 10 (76.8b) | 2 (25b) |

| COPD—n (%) | 48 (19.3b) | 7 (5.4b) | 0 (0b) |

| Influenza—n (%) | 14 (5.6b) | 2 (1.5b) | 0 (0b) |

| SARF—n (%)c | 41 (16.5b) | 21 (16.2b) | 2 (25b) |

| Tuberculosis—n (%) | 1 (0.4b) | 0 (0b) | 0 (0b) |

| Heart disease—n (%)d | 43 (13.4a) | 5 (3.6a) | 2 (25a) |

| Extrapulmonary sepsis with acute lung injury—n (%) | 30 (9.3a) | 3 (2.2a) | 2 (25a) |

Frequency of reasons for hospitalization of patients with false-positive and false-negative results and patients with a true negative diagnosis according to the proposed set of clinical-radiological criteria

n absolute frequency, % percentage, SARF severe acute respiratory syndrome, ICU intensive care unit

aPercentage considering the total number of cases for each column

bPercentage considering the total pulmonary reasons for each column

cRespiratory failure due to causes other than COVID-19

dAll patients had congestive heart failure

Discussion

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample, which comprised patients admitted to ICUs with suspected COVID-19, were similar to those described in studies conducted in other locations severely affected by the pandemic [12–16]. As in this study, others also have sought to improve the screening process for COVID-19 by analyzing the relationship between chest CT findings and RT-PCR results in patients with suspected COVID-19, developing an artificial neural network, using logistic regression or proposing decision trees, in an attempt to diagnose the disease [2, 4, 17–20].

The findings of the present study showed a close relationship between the classification of strong suspicion for COVID-19 by the proposed set of clinical-radiological criteria and a positive RT-PCR result, with high sensitivity (98.5%) and a narrow confidence interval, suggesting that the diagnosis of COVID-19 is very unlikely in the absence of the proposed criteria. Thus, the high probability of a patient classified as having a strong suspicion for COVID-19 presenting a positive RT-PCR result suggests that the systematic application of the proposed set of criteria would have a positive impact on the screening of cases with suspected disease. This would translate into a more assertive approach in the provided care, including the application of appropriate sanitary measures and the implementation of specific treatment protocols even before the microbiological confirmation of the disease.

The high sensitivity of the proposed criteria may be related to the average duration of symptoms in the study population, which was relatively high, and the presence of tomographic changes [21], as chest CT findings may not be present in patients with a short symptom duration [22–24]. However, some clinical conditions at admission became confounders and led to a strong suspicion for the disease, which was not confirmed by microbiological examination. Among these confounding diseases are those that also present with SARF, such as acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bacterial pneumonia, and extrapulmonary sepsis with acute pulmonary injury.

On the other hand, the high sensitivity encountered brought along a high percentage of false-positive results. However, it should be noted that RT-PCR has a high rate of false-negative results for the diagnosis of COVID-19, especially in more advanced stages of the disease; therefore, patients who are strongly suspected of having COVID-19 but have a negative RT-PCR result could have a positive result in a repeat RT-PCR test, so the possibility of the disease cannot be ruled out [10].

Our set of clinical-radiological criteria developed by intensive care physicians in March 2020—when there was still no complete knowledge about the signs and symptoms that could be related to the disease—based on the literature and used pragmatically to screen patients with SARF on ICU admission during the COVID-19 pandemic, showed sensitivity, specificity and accuracy values similar to those of diagnostic model for COVID-19 developed using logistic regression models and artificial neural network [18, 20].

We included in the set of clinical-radiological criteria respiratory symptoms and fever, which at the beginning of the pandemic were the most related to covid-19. This could explain the burden of other non-COVID-19 lung diseases in the false positive group, as many lung diseases share similar symptoms. However, other studies demonstrate that fever and respiratory symptoms, such as cough and rhinorrhea are the most strongly correlated with the diagnosis of COVID-19, although several other extrapulmonary signs and symptoms may be present in patients with COVID-19 [18, 19].

Among the patients identified as having a weak suspicion for COVID-19, we found only 1.5% of false-negative results; the confounders in these cases were other lung diseases, especially bacterial pneumonia.

The limitations of our study include the involvement of multiple intensivists in routinely evaluating the parameters of the clinical-radiological criteria and CT scans, which could have resulted in diverse interpretations of the findings, and the final reports of chest CTs being signed by different radiologists. As a strength, the group of professionals who performed the initial evaluation was small. Finally, we want to emphasize that all patients analyzed in this study had moderate to severe disease as determined by the WHO Clinical Progression Scale, i.e., a score ≥ 5 in the 10-point table [8].

Finally, we consider that the study contributes with relevant information by presenting the possibility of screening patients with suspected COVID 19 based on clinical and radiological criteria without the use of RT-PCR, which was not always available, especially in low-income countries.

Conclusion

The application of the criteria based on three clinical and radiological parameters proposed in this study could accurately identify patients with COVID-19 while RT-PCR results are pending. These criteria had high sensitivity and negative predictive value, and still considerable specificity and positive predictive value for a COVID-19 diagnosis when compared with the reference standard RT-PCR, in patients with mild/moderate respiratory dysfunction, as well as with severe respiratory dysfunction at ICU admission.

The adoption of these criteria may contribute to the timely implementation of recommended treatments in advance of the microbiological result and the application of sanitary actions such as placing patients in respiratory isolation and separating cohorts of inpatients with strong versus weak suspicion of COVID-19, thus helping the clinical management of these patients and reducing cross-contamination.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to all the participating centers for the support and interventions in our study during this challenging period for everyone. We would also like to thank Verônica Barros, along with the entire research team, for their support and collaboration.

Abbreviations

- RT-PCR

Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- SARF

Severe acute respiratory failure

- ICUs

Intensive care units

- CI

Confidence interval

- CEPETI

Center for Studies and Research in Intensive Care Medicine

- qSOFA

Quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- CT

Computed tomography

- APACHE II

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

- ORs

Odds ratios

- SD

Standard deviation

- IQR

Interquartile range

Author contributions

Study conception, study design, data interpretation: MCO and ARN; data acquisition and analysis, manuscript draft and revision: MCO, KOS, RSB, AKN, SML and BIT; data acquisition, manuscript revision: MCO, ARN, RSB, AKN, SML FBR and CCM. All authors have approved the submitted version and agreed to be personally accountable for their own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated and resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Zenodo repository, DOI 10.5281/zenodo.7140845 and hyperlink to dataset is 10.5281/zenodo.7140845.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Instituto de Neurologia de Curitiba under protocol number 3,000,353 on November 05th, 2018 (ID: CAAE 98099918.2.0000.5227; project title: Epidemiological analysis of patients hospitalized in ICUs in Curitiba-Paraná). The requirement for informed consent was waived by the same committee, given the noninterventional design of the study and the fact that the data were collected from clinical records and without contact with the participants and the procedures performed in this study were part of routine care. The document that supports this information was made available on the related files. All research procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee on human experimentation and the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2013.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mirella Cristine Oliveira, Email: moliveira969@gmail.com.

Karoleen Oswald Scharan, Email: karoleen.s@hotmail.com.

Bruna Isadora Thomés, Email: bruna_thome03@hotmail.com.

Rafaella Stradiotto Bernardelli, Email: rafaella.bernardelli@gmail.com.

Fernanda Baeumle Reese, Email: fefa_reese@hotmail.com.

Amanda Christina Kozesinski-Nakatani, Email: akozesinski@gmail.com.

Cintia Cristina Martins, Email: cintia.c.martins2018@gmail.com.

Suzana Margareth Ajeje Lobo, Email: suzanaalobo@gmail.com.

Álvaro Réa-Neto, Email: reaneto@uol.com.br.

References

- 1.Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA. 2020;324(8):782. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W, et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E32–40. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koo HJ, Lim S, Choe J, Choi SH, Sung H, Do KH. Radiographic and CT features of viral pneumonia. Radiographics. 2018;38(3):719–739. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karam M, Althuwaikh S, Alazemi M, Abul A, Hayre A, Alsaif A, et al. Chest CT versus RT-PCR for the detection of COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. JRSM Open. 2021;12(5):205427042110118. doi: 10.1177/20542704211011837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.China National Health Commission. Diagnosis and treatment protocol for COVID-19 (Trial Version 7) [Internet]. Beijing: China National Health Commission. 2020 [cited 2022 Jun 15]. Available from: http://en.nhc.gov.cn/2020-03/29/c_78469.htm

- 6.Kameda K, Barbeitas MM, Caetano R, Löwy I, de Oliveira ACD, Villela Corrêa MCD, et al. Testing COVID-19 in Brazil: fragmented efforts and challenges to expand diagnostic capacity at the Brazilian Unified National Health System. Cad Saude Publica. 2021;37(3):h5527. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00277420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig L, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. OPEN ACCESS. 2015 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall JC, Murthy S, Diaz J, Adhikari N, Angus DC, Arabi YM, et al. A minimal common outcome measure set for COVID-19 clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(8):e192–e197. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30483-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singer M, Deutschman CS, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) clinical review & education special communication caring for the critically ill patient. JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akçay Ş, Özlü T, Yilmaz A. Radiological approaches to COVID-19 pneumonia. Turkish J Med Sci. 2020;50:604–610. doi: 10.3906/sag-2004-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filchakova O, Dossym D, Ilyas A, Kuanysheva T, Abdizhamil A, Bukasov R. Review of COVID-19 testing and diagnostic methods. Talanta. 2022;1(244):123409. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2022.123409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Ban Y, Wu YH, Liu JY, Li XH, Wu H, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 65 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Liaoning. China World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(10):2205–2217. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i10.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briguglio M, Crespi T, Pino F, Mazzocchi M, Porta M, De Vecchi E, et al. Clinical characteristics of severe COVID-19 patients admitted to an intensive care unit in lombardy during the Italian pandemic. Front Med. 2021;8(March):1–6. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.582896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng D, Calderwood C, Skyllberg E, Ainley A. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of adult patients admitted with COVID-19 in East London: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2021;8(1):e000813. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nanda S, Toussaint L, Vincent A, Fischer KM, Hurt R, Schroeder DR, et al. A midwest COVID-19 cohort for the evaluation of multimorbidity and adverse outcomes from COVID-19. J Prim Care Commun Heal. 2021 doi: 10.1177/21501327211010991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pouw N, de Maat J, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of 952 hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the Netherlands: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim H, Hong H, Yoon SH. Diagnostic performance of CT and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction for coronavirus disease 2019: a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2020;296(3):E145–E155. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanbehzadeh M, Nopour R, Kazemi-Arpanahi H. Developing an artificial neural network for detecting COVID-19 disease. J Educ Health Promot. 2022;11(1):2. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_387_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shanbehzadeh M, Kazemi-Arpanahi H, Nopour R. Performance evaluation of selected decision tree algorithms for COVID-19 diagnosis using routine clinical data. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2021;35:29. doi: 10.47176/mjiri.35.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nopour R, Shanbehzadeh M, Kazemi-Arpanahi H. Using logistic regression to develop a diagnostic model for COVID-19: a single-center study. J Educ Health Promot. 2022;11(1):153. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1017_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Hou H, Wang W, Wang W. Combination of CT and RT-PCR in the screening or diagnosis of COVID-19. J Glob Health. 2020 doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.010347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu B, Xing Y, Peng J, Zheng Z, Tang W, Sun Y, et al. Chest CT for detecting COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(10):5720–5727. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06934-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Francesco Sardanelli F, Di Leo G, Milanese D. Letters to the Editor. 2019;2019–20.

- 24.Shao JM, Ayuso SA, Deerenberg EB, Elhage SA, Augenstein VA, Heniford BT. A systematic review of CT chest in COVID-19 diagnosis and its potential application in a surgical setting. Color Dis. 2020;22(9):993–1001. doi: 10.1111/codi.15252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Zenodo repository, DOI 10.5281/zenodo.7140845 and hyperlink to dataset is 10.5281/zenodo.7140845.