Abstract

The most common symptom of peripheral artery disease (PAD) is intermittent claudication, which consists of debilitating leg pain during walking. In clinical settings, the presence of PAD is often noninvasively evaluated using the ankle–brachial index and imaging of the arterial supply. Furthermore, various questionnaires and functional tests are commonly used to measure the severity and negative effect of PAD on quality of life. However, these evaluations only provide information on vascular insufficiency and severity of the disease, but not regarding the complex mechanisms underlying walking impairments in patients with PAD. Biomechanical analyses using motion capture and ground reaction force measurements can provide insight into the underlying mechanisms to walking impairments in PAD. This review analyzes the application of biomechanics tools to identify gait impairments and their clinical implications on rehabilitation of patients with PAD. A total of 18 published journal articles focused on gait biomechanics in patients with PAD were studied. This narriative review shows that the gait of patients with PAD is impaired from the first steps that a patient takes and deteriorates further after the onset of claudication leg pain. These results point toward impaired muscle function across the ankle, knee, and hip joints during walking. Gait analysis helps understand the mechanisms operating in PAD and could also facilitate earlier diagnosis, better treatment, and slower progression of PAD.

Keywords: biomechanics, claudication, gait, ischemia, peripheral artery disease (PAD), walking

Introduction

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a significant, worldwide public health problem. It is estimated to affect 236 million people globally, including 8–12 million people in the United States.1,2 Worldwide, the estimated prevalence of PAD is 7.37% in high-income countries and about 5.09% in low- and middle-income countries; making it the third greatest cause of atherosclerotic cardiovascular morbidity after coronary artery disease and stroke.2,3 Even though PAD is a well-known cause of morbidity, it remains underdiagnosed.4

Intermittent claudication (IC) is the most common symptom of PAD; affecting one-third of patients.5,6 As a result of IC, people with PAD tend to limit physical activity,7,8 which affects their quality of life and produces an increasingly sedentary lifestyle.9 Physical impairment due to PAD exists even in those with asymptomatic or atypical leg symptoms, which constitutes most people with PAD.10 The most common atypical leg pain symptoms include leg pain/discomfort that begins at rest but distinct from ischemic leg pain or exertional leg pain/discomfort that does not cause the patient to stop walking or leg pain/discomfort that consistently do not resolve with rest.11

The negative effect of PAD on quality of life and physical functioning is typically characterized and measured with various questionnaires and functional tests. Some of the commonly used questionnaires are: walking impairment questionnaire (WIQ),12,13 medical outcomes study short form (SF-36),14 patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS),15 vascular quality of life (VascuQoL) questionnaire,16,17 peripheral artery questionnaire (PAQ),18 and peripheral artery disease quality of life (PADQOL) questionnaire.19 These patient-reported outcome measure tools are qualitative and subjective, hence do not help in identifying the mechanisms responsible for gait impairment in PAD. Various quantitative functional tests (such as the 6-minute walk test, chair raises, timed up and go, etc.) are used to evaluate the severity of PAD. These questionnaires and quantitative measures effectively determine the perceived quality of life and functional status in patients with IC. However, establishing a consensus on the best assessment for symptomatic patients with PAD and standardizing the implementation and interpretation of these tools in clinical settings has been difficult.20,21 Thus, researchers and clinicians often seek combinations of objective and subjective function assessments for patients with PAD.

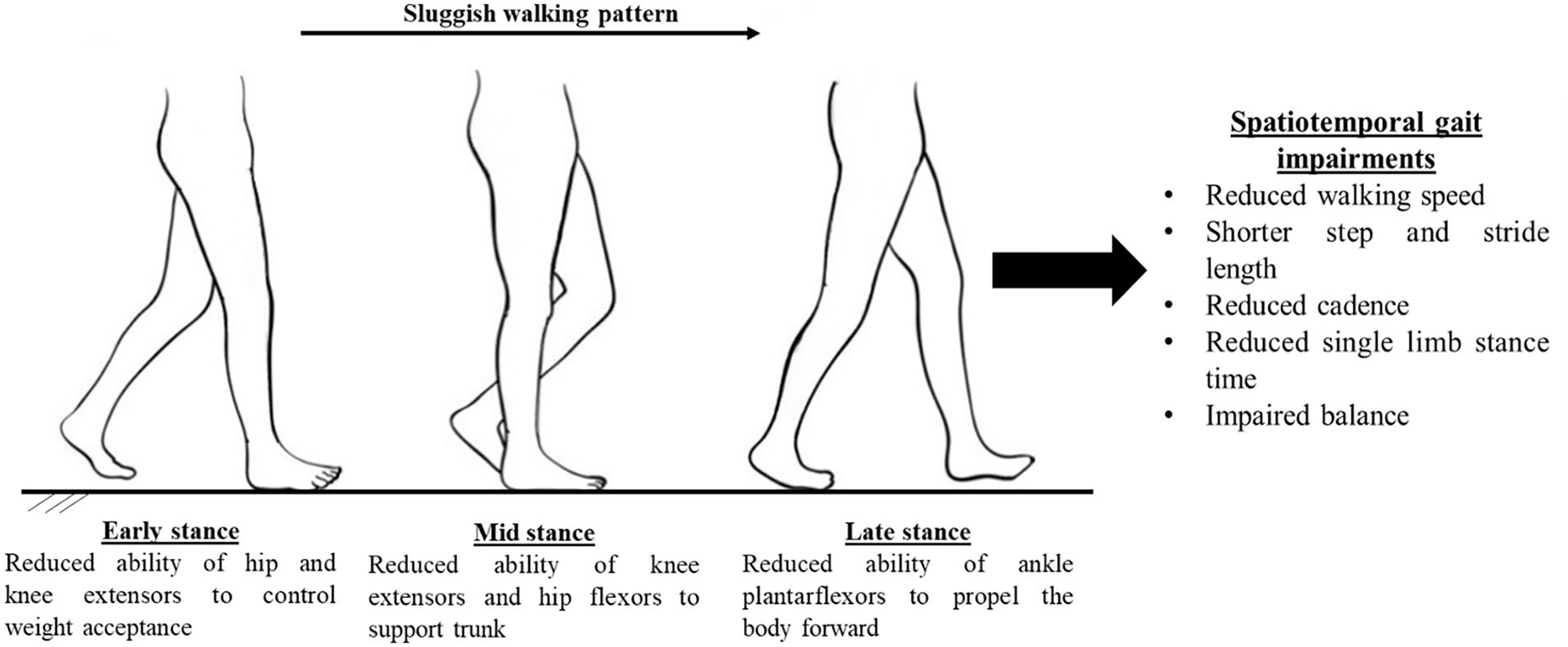

Spatial and temporal features of gait have more recently been used to assess physical function in patients with PAD.22–26 It has been found that patients with PAD generally walk slower,22,24,27,28 have shortened step length,24,28 reduced cadence,22,24,28 and shorter single-limb stance time28 with a higher propensity to fall.29,30 These spatiotemporal evaluations indicate abnormal gait in patients with PAD. However, they fail to provide specific insights regarding the precise locations and mechanisms operating to produce the impaired walking patterns in patients with PAD. Thus, these parameters can mainly be used to evaluate the functional changes that occur with disease progression or after an intervention.

Advanced biomechanics techniques have led to progress in monitoring and treating several medical conditions, including stroke, cerebral palsy, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, osteoarthritis, and lower-limb amputations. Similarly, biomechanical assessments in PAD allow for detailed characterization of the severity of walking impairments of patients with PAD and provide insights into the mechanisms contributing to impaired gait.31 Before the last decade, gait evaluation in patients with PAD was limited to time and distance measurements. These methods established that patients with PAD have different gait patterns than age-matched counterparts without PAD, but it was not until gait biomechanical evaluations were employed32–34 that we were able to identify and better understand the mechanisms operating in PAD.31,35 The purpose of this work is to review the findings related to gait impairments in patients with PAD and their clinical implications based on the analyses performed by advanced gait biomechanics.

Methods of biomechanical assessment

Accurate assessments of the way patients with PAD walk, before and after the onset of claudication pain, can be performed using standard gait biomechanics methods utilizing motion capture systems integrated with force platforms.31,35 Such comprehensive analysis of numerous kinematic and kinetic gait variables can minimize the need for the number and certain types of examinations described in previous sections such as the 4-and 6-meter walk tests for measuring walking speed and other spatiotemporal parameters. Motion capture requires reflective markers attached to specific anatomical landmarks on the human body. This allows each limb segment movement to be precisely tracked in three-dimensional space by infrared cameras. Kinematic data can then be used to calculate ankle, knee, and hip joint angles. A force platform measures the ground reaction forces (GRF) and the location of the center of pressure during the stance phase of walking. The GRF is exerted by the ground on a body in contact with it and is composed of vertical, anterior-posterior, and mediolateral components. Inverse dynamics analyses are performed on the obtained motion capture and force platform data to calculate net joint forces, joint torque, and joint power. The first derivative of the limb segment angle gives the angular velocity and the second derivative provides the angular acceleration of that segment. The rotational effect of the force located at a distance from the joint axis is quantified using joint torques. In an inverse dynamics analysis, joint torque is calculated as the scalar product of the moment of inertia and angular acceleration of the limb segment under consideration.36 The joint power quantifies the muscular contributions to movement at individual joints during walking. The joint power is calculated as the scalar product of net joint torque and angular velocity of the limb segment.36

Summary of gait biomechanics studies in patients with PAD

Relevant journal articles were searched in Google Scholar, PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and Cochrane Library databases. The published articles up to April 31, 2022 are included in this review. The search was limited to studies published in English. The following search terms and their combination was used: biomechanics, gait, peripheral artery disease, claudication, joint kinetics, kinematics, walking, and ischemia. After careful scrutiny of articles to remove duplicates and irrelevant articles, a total of 18 articles that focused on gait biomechanics in patients with PAD were included in this perspective review (shown in online Supplementary Table S1). We have excluded the articles focusing on gait variability in patients with PAD from this review. The following sections summarize the results of studies of the biomechanics of patients with PAD measured in motion capture laboratories.

Ground reaction forces.

Two studies of overground walking in patients with PAD reported no difference in the vertical ground reaction force pattern as compared to healthy controls.37,38 A laboratory-based study of patients with PAD found a flatter vertical ground reaction force curve before and after the onset of claudication pain as compared to healthy controls.35 A recent study showed a significant reduction in maximum vertical GRF during the early and late stance in patients with PAD compared to healthy controls.39 Flattening of the vertical ground reaction force curve suggests reduced vertical movement in the body’s center of mass. Another study40 performed frequency domain analysis of the GRF to assess the frequency content in healthy subjects and patients with PAD. Median frequency, which is the point where half of the total power is above and below that frequency, was found to be significantly reduced (p = 0.037) in the vertical forces compared to speed and age-matched controls. This suggests a sluggish walking pattern in patients with PAD40 versus their healthy counterparts.

In the case of anterior-posterior ground reaction forces, decreased propulsion peak35,38,39 and propulsion impulse35,41 were reported in patients with PAD. Reduction in forward impulse suggests a lack of strength and dysfunction in lower-extremity propulsive muscles (the posterior calf muscles, mainly the gastrocnemius, soleus, tibialis posterior, and flexor digitorum longus muscles). The significantly reduced (p = 0.031) median frequency of the anterior-posterior ground reaction forces was consistent with the vertical ground reaction force findings.40 An early study comparing the peak mean anterior-posterior force among patients with PAD and controls reported no difference between groups.37

Higher medial ground reaction forces were reported in patients walking after the onset of claudication pain.35 A prior study37 reported that ‘the medio-lateral force is larger in patients with PAD than normal individuals’. One explanation for this could be based on the reduced center of mass vertical excursions in patients with PAD. Owing to a flatter center of mass trajectory, patients might be adopting a hip circumduction strategy to clear the ground during the swing phase. This results in wider steps during walking, generating larger medial forces, a finding consistent with other spatiotemporal studies.33

Differences between studies37,38 could be due to methodological differences and different statistical comparison groups. Pietraszewski et al.38 visually compared the pattern, whereas Carlsöö et al.37 only compared the mean values of three ground reaction force components in patients with IC and healthy controls. Furthermore, the study by Rosoky et al.41 was performed using wearable pressure insoles to approximate forefoot impulse, whereas all other studies utilized the gold standard, force platforms.

Recent studies of stair ascent and descent in patients with PAD42,43 reported a statistically significant reduction in the vertical and propulsion forces during stair climbing in patients with PAD compared to controls. The severity of PAD was also correlated with increased peak medial forces and reduced peak propulsion forces during stair ascent.42 These results are similar to previous literature on the ground reaction force pattern during overground walking in patients with PAD.

Joint angles.

Multiple studies25,38,44,45 on gait analysis in patients with PAD have compared the hip, knee, and ankle joint angles in the sagittal plane to healthy controls. Patients with PAD demonstrated reduced peak ankle plantar flexion in terminal stance and overall reduced ankle range of motion (ROM).25,44 Two other studies31,45 reported significantly increased peak ankle plantar flexion angle during early stance and increased ankle ROM during the stance phase. This discrepancy is because the two latter studies31,45 only measured the stance phase. In contrast, other studies considered the entire gait cycle.

Two studies reported a statistically significant reduction in knee ROM in patients with PAD compared to healthy individuals.25,38 Two others31,44reported nonsignificant reductions in knee ROM compared to healthy individuals, although Gommans et al.44 found significant reductions (p = 0.019) in the knee ROM in patients with PAD during walking with pain compared to pain-free walking.

Compared to healthy individuals, patients with PAD showed significantly decreased peak hip flexion during early stance45 and peak hip extension during push-off25 when walking before the onset of claudication pain. Walking after pain onset led to further reductions in peak hip flexion in patients with PAD.45 One study did not find significant differences in the hip flexion-extension angle or hip ROM compared to healthy controls when patients with PAD walked before and after the onset of IC.31 A potential reason for the lack of differences observed in hip and knee joint angles in Celis et al.31 could be that the patient population had single-level, isolated femoropopliteal segment PAD. It is possible that in patients with femoropopliteal disease, calf musculature is the most affected, whereas in patients with aortoiliac and multilevel disease included in other studies, muscles of the thigh and buttocks are affected. The average ROM in pelvic obliquity (p < 0.001) and pelvic rotation (p < 0.0001) was significantly reduced in patients with PAD compared to healthy counterparts.38

Joint torques.

Hip, knee, and ankle joint torques were reported in studies evaluating gait in patients with PAD during pain-free (before the onset of claudication symptoms) and pain-induced (after the onset of claudication symptoms) walking conditions compared to healthy controls of similar age. Most studies divided the stance phase into three subphases: early stance (also known as weight acceptance), mid stance (single-limb support), and terminal stance (push-off). Thus, reporting joint torques according to these three subphases helps to correlate and interpret the results concerning muscle contractions.

During the early stance phase, peak hip extensor torque was significantly reduced during self-selected33,39,45–47 and fast overground walking46 in patients with PAD. This implies decreased concentric contractions of the hip extensors (gluteal muscles). Similar reductions in the peak knee extensor (predominantly the quadriceps muscles) torque during early stance were reported in patients with PAD, walking at self-selected speed with and without claudication pain compared to healthy controls.32,33,46,47 These differences correspond to less eccentric muscle activity (i.e., reduced knee extensor torque), and they remained significant while walking at a fast speed and before IC onset.46 Likewise, there were significant reductions in ankle dorsiflexor (predominantly tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, and extensor hallucis longus muscles) torque in patients with PAD during early stance while walking with and without pain at self-selected speed and without pain at fast speed as compared to healthy controls.32,46 Some studies did not find a significant difference in the ankle dorsiflexor torque compared to healthy controls.33,34,39,47 In general, weakness of the hip and knee extensors and ankle dorsiflexors in early stance implies diminished control of weight acceptance, which translates into impaired transfer of momentum across the remaining stance phase of walking in patients with PAD.

There was no significant difference between patients with PAD and healthy controls in the peak joint torques during single-limb support. During single-limb support, limited muscle contractions are required to maintain the eccentric contraction of the knee extensors during early stance, which was reduced in patients with PAD, as mentioned earlier.

During push-off, patients with PAD showed reduced peak hip flexor (predominantly iliopsoas muscles) torque during pain-free and pain-induced walking at self-selected speed33 and pain-free walking at fast speed.46 Additionally, compared with healthy individuals, reduced peak ankle plantar flexor (predominantly soleus and gastrocnemius muscles) torque was found in patients with PAD.32,33,39,45 These reductions are consistent with reduced concentric muscle activity at the ankle and hip during push-off.

Some studies did not report significant reductions in the peak ankle plantar flexor torque in patients with PAD, walking without claudication pain at self-selected46,47 and fast speed,46 as compared to healthy age-matched controls. The lack of consensus on ankle plantar flexor torque among these studies could be due to the differences in individuals’ ages, as Myers et al.48 showed that joint torques significantly differ between young (age < 65 years) and older (age ⩾ 65 years) patients with PAD. When patients with PAD walking before the onset of IC pain were compared with speed-matched healthy controls, the peak hip, knee, and ankle joint torques throughout the stance phase were not significantly different.34 When adjusted for stride length, step width, and velocity as covariates, there was a significant difference for the knee extensor torque during early stance.47 Differences in spatiotemporal parameters of subjects across studies could be another reason for discrepancies. Other potential reasons include a varying level of claudication or disease severity of participants across the studies.

Joint powers.

The reduction in measured joint torque during various stance phases impacts joint powers in patients with PAD. The characteristic walking gait in patients with PAD during early stance includes decreased hip extensor power generation,33,39 reduced knee extensor power absorption,32–34,39,46 and reduced ankle dorsiflexor power absorption.32,33 During mid-stance, decreased hip flexor power absorption32–34,46 and decreased knee extensor power generation compared with controls32,33,46 was reported. Almost all studies reporting joint power in patients with PAD show a characteristic reduction in the ankle plantar flexor power generation peak during the push-off phase.32–34,39,46

The studies cited above did not control for walking speed or other potential covariates. However, later studies adjusting for confounding spatiotemporal variables such as stride length, step width, and walking speed confirmed a significant difference, mainly in the ankle plantar flexor power during the push-off phase.47 These reductions in ankle plantar flexor power were significant during pain-free and pain-induced self-selected walking32,33 and fast walking,46 even when compared with speed-matched healthy controls.34 During push-off, decreased knee flexor power absorption33,34,39,46 and decreased hip flexor power generation33,46 were reported in patients with PAD compared to healthy controls.

Discussion

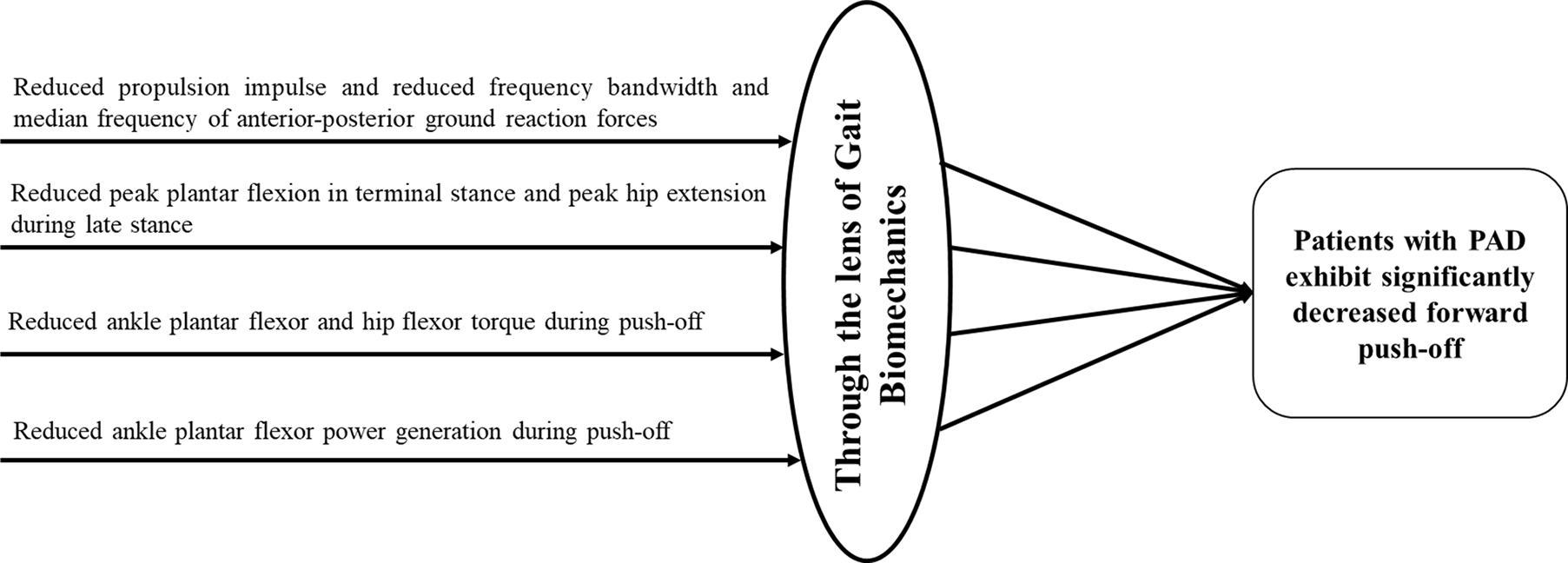

Previous studies on spatiotemporal parameters of gait have shown that patients with PAD walk more slowly, with reduced cadence, and shorter stride length.22–26,28 Gait biomechanics studies have confirmed these findings and significantly advanced this work showing that patients with PAD walking both with and without claudication pain walk differently than their healthy counterparts (Figure 1). The key findings from gait biomechanics studies in patients with PAD are summarized in Table 1. These gait changes show that PAD produces defective neuro-muscular performance and cooperation across the ankle, knee, and hip joints and throughout stance. These impairments are present from the first step a patient with PAD takes (even before claudication pain starts) and worsen after the onset of claudication symptoms in the affected limbs. Furthermore, findings from various gait biomechanics studies point toward significantly reduced forward push-off during late stance in patients with PAD. Thus, the microscope of gait biomechanics helps to identify the underlying mechanisms associated with gait impairments in patients with PAD, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Cause and effect analysis of gait impairments in patients with peripheral artery disease using findings from gait biomechanics studies.

Table 1.

Summary of significant findings based on gait biomechanics studies in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) compared to healthy counterparts.

| Gait biomechanics parameters | Significant findings in patients with PAD |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Ground reaction forces (GRF) | • A flatter vertical ground reaction force profile35,39,40 |

| • Reduced propulsion impulse35,41 and reduced frequency bandwidth and median frequency of anterior-posterior ground reaction forces40 | |

| Joint angles | • Increased peak plantar flexion31,45 and decreased hip flexion during early stance34,45 |

| • Reduced peak plantar flexion in terminal stance25,44 and peak hip extension during late stance25 | |

| Joint torques | • Decreased torque contribution by the hip extensors33,34,45 knee extensors32,34 and ankle dorsiflexors32,34 during weight acceptance |

| • Reduced ankle plantar flexor32,33,39,45 and hip flexor torque33,46 during push-off | |

| Joint powers | • Reduced ankle plantar flexor power generation during push-off32–34,39,46 |

| Key Conclusions | |

| • Patients with PAD exhibit significantly decreased forward push-off | |

| • Gait impairments in patients with PAD are present across the hip, knee and ankle joint throughout the stance phase. | |

| • Overall, gait of patients with PAD is significantly impaired compared to healthy counterparts both before and after onset of claudication pain. | |

Figure 2.

Gait biomechanics provides a microscopic lens to analyze gait impairments in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD). Gait biomechanics findings from various studies point toward reduced forward push-off during late stance in patients with PAD.

The gait biomechanics studies help shed light on the critical question of whether the gait changes observed in patients with PAD are due to acquired deconditioning resulting from less walking or due to vascular insufficiency. It is known that PAD produces an ischemic myopathy in the legs of patients with PAD.49,50 At the histological level, this myopathy is characterized by myofiber degeneration and fibrosis involving both the myofibers and the muscle microvessels and capillaries.51–53 Thus, walking impairments in people with PAD are due to both reduced vascular perfusions from atherosclerotic blockages in lower-extremity arteries, and skeletal muscle damage, most likely from ischemia reperfusion injury to skeletal muscle.11 A recent study showed that variability in gait parameters is affected by both PAD and reduced blood flow.54 Another study showed that gait changes in patients with PAD are more significant than deconditioning found in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.55 Previously, it has been shown that gait in the absence of PAD, and other ambulatory comorbidities, does not decline significantly with age.48 These studies compared gait in patients with PAD to non-PAD groups, including older individuals without PAD. The overall evidence from gait biomechanics studies shows that gait alterations in patients with PAD are primarily due to vascular insufficiency and resulting muscle damage. The contribution of acquired deconditioning owing to less walking needs to be further investigated.

Precise assessment of gait biomechanics has proven a useful way to assess differences versus healthy counterparts, determine mechanisms responsible for gait alterations, and evaluate treatment effectiveness in patients with PAD.56–58 Therefore, determining the presence of PAD without the need to induce leg pain will be beneficial for assessing the risk of disease progression and allow early interventions and therapies to prevent or lessen the consequences of the disease. A recent study successfully implemented a machine learning model on gait biomechanics data to identify presence of PAD.59 Similarly, gait analysis can provide vital information to guide the selection of treatments and develop new interventions for improving the quality of life in patients with PAD.

Study limitations

There are certain limitations of this perspective review. The lack of a systematic search strategy for the selection of articles may have resulted in selection bias or omission of some relevant articles. Furthermore, some differences in comparing gait kinematic and kinetic outcomes for patients with PAD have been observed across studies. Different inclusion/exclusion criteria, clinical parameters of PAD (unilateral vs bilateral, level of disease, disease severity, age group), and/or instrumentation and methodology likely contribute to the differences. Methodological and statistical approaches suggest that velocity influences biomechanics and spatiotemporal parameters across studies and between patients with PAD and healthy controls; walking velocity could account for some of the variance in results. Future work also needs to be done using statistical techniques like meta-analysis to establish the combined significant effect with regard to gait biomechanics changes in patients with PAD. Additionally, minimal clinically important differences need to be established for various gait biomechanics parameters to use those in a clinical setting for outcome measurement in patients with PAD.

Regarding future treatment strategies, focus should be on identifying the muscle groups most affected by PAD to understand how muscles can effectively be treated and rehabilitated, particularly following revascularization interventions that improve blood flow, but do not automatically restore muscles to health. For these reasons, the pathophysiology of PAD myopathy, its contribution to the deteriorated ambulation of patients with PAD, and the impact on cardiovascular risk make the exploration of appropriate treatments to reverse and ameliorate PAD an important area of research in older populations.49,50,60

In general, there is a lack of studies addressing the length of time required to restore the gait after exercise therapy and surgical interventions. Previous studies show that 3–6 months of supervised exercise therapy increases walking distances and quality of life.61–63 These improvements are concurrent with improvements in muscle strength and gait biomechanics, including torque and power generation at the ankle and hip joints.58 Future work should also examine the benefits of supervised exercise therapy combined with other available treatments for PAD. The effects of revascularization and alternative exercise protocols on spatiotemporal gait parameters, in addition to accepted clinical measurements, should be scientifically investigated to provide a comprehensive understanding of how such protocols may help rehabilitate gait in individuals with PAD. Ultimately, the goal of using biomechanical assessments is to guide the patient toward improved function through targeted physiotherapy and exercise or with assistive devices. Gait biomechanics assessments can function as a vital tool in measuring the efficacy of any intervention that aims to enhance and restore gait in patients with PAD.

Conclusions

This review summarizes the currently published research on the walking impairment of patients with PAD and presents novel ways to synthesize and explain the results. Biomechanics contributes to an optimal understanding of the impairments present in the ambulation of patients with claudication. The review shows that gait impairments are present from the first step a patient with PAD takes and worsen after the onset of claudication symptoms in the affected limbs. Furthermore, the precise information regarding the muscular contributions at specific joints during each gait cycle phase provides insights into the mechanisms contributing to the severe functional limitations of patients with claudication. The growing discipline of biomechanics with the progressive integration of advanced engineering techniques and new technologies has the potential to guide the efforts of researchers and clinicians to restore gait in patients with PAD.

Supplementary Material

Funding

Sara A Myers is funded by the National Institutes of Health RO1 grant (RO1HD090333). Sara A Myers and Iraklis I Pipinos are funded by VA Merit grant I01 RX003266. Iraklis I Pipinos was supported by the National Institutes of Health RO1 grant RO1AG034995. AZB was supported by UNO GRACA 2020–2021 grant. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online with the article.

References

- 1.Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016. AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: Executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69: 1465–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song P, Rudan D, Zhu Y, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2015: An updated systematic review and analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7: e1020–e1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowkes FGR, Rudan D, Rudan I, et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: A systematic review and analysis. Lancet 2013; 382: 1329–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kithcart AP, Beckman JA. ACC/AHA Versus ESC Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Peripheral Artery Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 72: 2789–2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiatt WR. Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease and claudication. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1608–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease (Lower Extremity, Renal, Mesenteric, and Abdominal Aortic). Circulation 2006; 113: e463–e465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meru AV, Mittra S, Thyagarajan B, et al. Intermittent claudication: An overview. Atherosclerosis 2006; 187: 221–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, et al. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). J Vasc Surg 2007; 45: S5–S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez H, Myers SA, Schieber M, et al. Quantification of daily physical activity and sedentary behavior of claudicating patients. Ann Vasc Surg 2019; 55: 112–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDermott M, Liu K, Greenland P, et al. Functional decline in peripheral arterial disease: Associations with the ankle brachial index and leg symptoms. JAMA 2004; 292: 453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDermott MMG. Lower extremity manifestations of peripheral artery disease: The pathophysiologic and functional implications of leg ischemia. Circ Res 2015; 116: 1540–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDermott MM, Liu K, Guralnik JM, et al. Measurement of walking endurance and walking velocity with questionnaire: Validation of the walking impairment questionnaire in men and women with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg 1998; 28: 1072–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coyne KS, Margolis MK, Gilchrist KA, et al. Evaluating effects of method of administration on Walking Impairment Questionnaire. J Vasc Surg 2003; 38: 296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware J, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and interpretation guide. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol 2010; 63: 1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan MBF, Crayford T, Murrin B, et al. Developing the Vascular Quality of Life Questionnaire: A new disease-specific quality of life measure for use in lower limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg 2001; 33: 679–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nordanstig J, Wann-Hansson C, Karlsson J, et al. Vascular Quality of Life Questionnaire-6 facilitates health-related quality of life assessment in peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg 2014; 59: 700–707.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spertus J, Jones P, Poler S, et al. The peripheral artery questionnaire: A new disease-specific health status measure for patients with peripheral arterial disease. Am Heart J 2004; 147: 301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Treat-Jacobson D, Lindquist RA, Witt DR, et al. The PADQOL: Development and validation of a PAD-specific quality of life questionnaire. Vasc Med 2012; 17: 405–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDermott MM, Liu K, Ferrucci L, et al. Physical performance in peripheral arterial disease: A slower rate of decline in patients who walk more. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144: 10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers SA, Johanning JM, Stergiou N, et al. Claudication distances and the Walking Impairment Questionnaire best describe the ambulatory limitations in patients with symptomatic peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg 2008; 47: 550–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scherer SA, Bainbridge S, Hiatt WR, Regensteiner JG. Gait characteristics of patients with claudication. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79: 529–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCully K, Sanders T, Leiper C. The effects of peripheral vascular disease on gait. Med Sci Sport Exerc 1999; 54A: 291–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDermott MM, Ohlmiller SM, Liu K, et al. Gait alterations associated with walking impairment in people with peripheral arterial disease with and without intermittent claudication. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49: 747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crowther RG, Spinks WL, Leicht AS, et al. Relationship between temporal-spatial gait parameters, gait kinematics, walking performance, exercise capacity, and physical activity level in peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg 2007; 45: 1172–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myers SA, Huben NB, Yentes JM, et al. Spatiotemporal changes posttreatment in peripheral arterial disease. Rehabil Res Pract 2015; 2015: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newman AB. Commentary on ‘the Effects of Peripheral Vascular Disease on Gait’. J Gerontol Biol Sci 1999; 54A: B295–B296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gardner AW, Forrester L, Smith G. Altered gait profile in subjects with peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Med 2001; 6: 31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gardner AW, Montgomery PS. The relationship between history of falling and physical function in subjects with peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Med 2001; 6: 223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gardner AW, Montgomery PS. Impaired balance and higher prevalence of falls in subjects with intermittent claudication. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001; 56: M454–M458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Celis R, Pipinos II, Scott-Pandorf MM, et al. Peripheral arterial disease affects kinematics during walking. J Vasc Surg 2009; 49: 127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koutakis P, Pipinos II, Myers SA, et al. Joint torques and powers are reduced during ambulation for both limbs in patients with unilateral claudication. J Vasc Surg 2010; 51: 80–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koutakis P, Johanning JM, Haynatzki GR, et al. Abnormal joint powers before and after the onset of claudication symptoms. J Vasc Surg 2010; 52: 340–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wurdeman SR, Koutakis P, Myers SA, et al. Patients with peripheral arterial disease exhibit reduced joint powers compared to velocity-matched controls. Gait Posture 2012; 36: 506–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott-Pandorf MM, Stergiou N, Johanning JM, et al. Peripheral arterial disease affects ground reaction forces during walking. J Vasc Surg 2007; 46: 491–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winter DA. Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Movement. 4th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carlsöö S, Dahlöf AG, Holm J. Kinetic analysis of the gait in patients with hemiparesis and in patients with intermittent claudication. Scand J Rehabil Med 1974; 6: 166–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pietraszewski B, Woźniewski M, Jasiński R, et al. Changes in gait variables in patients with intermittent claudication. Biomed Res Int 2019; 2019: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evangelopoulou E, Jones RK, Jameel M, et al. Effects of intermittent claudication due to arterial disease on pain-free gait. Clin Biomech 2021; 83: 105309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGrath D, Judkins TN, Pipinos II, et al. Peripheral arterial disease affects the frequency response of ground reaction forces during walking. Clin Biomech 2012; 27: 1058–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosoky RMA, Wolosker N, Muraco-Netto B, et al. Ground reaction force pattern in limbs with intermittent claudication. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2000; 20: 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.King SL, Vanicek N, O’Brien TD. Sagittal plane joint kinetics during stair ascent in patients with peripheral arterial disease and intermittent claudication. Gait Posture 2017; 55: 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.King SL, Vanicek N, O’Brien TD. Joint moment strategies during stair descent in patients with peripheral arterial disease and intermittent claudication. Gait Posture 2018; 62: 359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gommans LNM, Smid AT, Scheltinga MRM, et al. Altered joint kinematics and increased electromyographic muscle activity during walking in patients with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg 2016; 63: 664–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen SJ, Pipinos I, Johanning J, et al. Bilateral claudication results in alterations in the gait biomechanics at the hip and ankle joints. J Biomech 2008; 41: 2506–2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kakihana T, Ito O, Sekiguchi Y, et al. Hip flexor muscle dysfunction during walking at self-selected and fast speed in patients with aortoiliac peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg 2017; 66: 523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCamley JD, Cutler EL, Schmid KK, et al. Gait mechanics differences between healthy controls and patients with peripheral artery disease after adjusting for gait velocity, stride length, and step width. J Appl Biomech 2019; 35: 19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Myers SA, Applequist BC, Huisinga JM, et al. Gait kinematics and kinetics are affected more by peripheral arterial disease than by age. J Rehabil Res Dev 2016; 53: 229–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pipinos II, Judge AR, Selsby JT, et al. The myopathy of peripheral arterial occlusive disease: Part 1. Functional and histomorphological changes and evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2008; 41: 481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pipinos II, Judge AR, Selsby JT, et al. The myopathy of peripheral arterial occlusive disease: Part 2. Oxidative stress, neuropathy, and shift in muscle fiber type. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2008; 42: 101–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koutakis P, Myers SA, Cluff K, et al. Abnormal myofiber morphology and limb dysfunction in claudication. J Surg Res 2015; 196: 172–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Becker RA, Cluff K, Duraisamy N, et al. Analysis of ischemic muscle in patients with peripheral artery disease using X-ray spectroscopy. J Surg Res 2017; 220: 79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koutakis P, Miserlis D, Myers SA, et al. Abnormal accumulation of desmin in gastrocnemius myofibers of patients with peripheral artery disease. J Histochem Cytochem 2015; 63: 256–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rahman H, Pipinos II, Johanning JM, et al. Gait variability is affected more by peripheral artery disease than by vascular occlusion. PLoS One 2021; 16: 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCamley JD, Pisciotta EJ, Yentes JM, et al. Gait deficiencies associated with peripheral artery disease are different than chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Gait Posture 2017; 57: 258–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huisinga JM, Pipinos II, Stergiou N, et al. Treatment with pharmacological agents in peripheral arterial disease patients does not result in biomechanical gait changes. J Appl Biomech 2010; 26: 341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yentes JM, Huisinga JM, Myers SA, et al. Pharmacological treatment of intermittent claudication does not have a significant effect on gait impairments during claudication pain. J Appl Biomech 2012; 28: 184–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schieber MN, Pipinos II, Johanning JM, et al. Supervised walking exercise therapy improves gait biomechanics in patients with peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg 2020; 71: 575–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Al-ramini A, Hassan M, Fallahtafti F, et al. Machine learning-based peripheral artery disease identification using laboratory-based gait data. Sensors 2022; 22: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pipinos II, Judge AR, Zhu Z, et al. Mitochondrial defects and oxidative damage in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2006; 41: 262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haas TL, Lloyd PG, Yang H, et al. Exercise training and peripheral arterial disease. Compr Physiol 2012; 2: 2933–3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bendermacher BL, Willigendael EM, Nicolaï SP, et al. Supervised exercise therapy for intermittent claudication in a community-based setting is as effective as clinic-based. J Vasc Surg 2007; 45: 1192–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Treat-Jacobson D, McDermott MM, Beckman JA, et al. Implementation of supervised exercise therapy for patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease: A Science Advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019; 140: e700–e710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.