Abstract

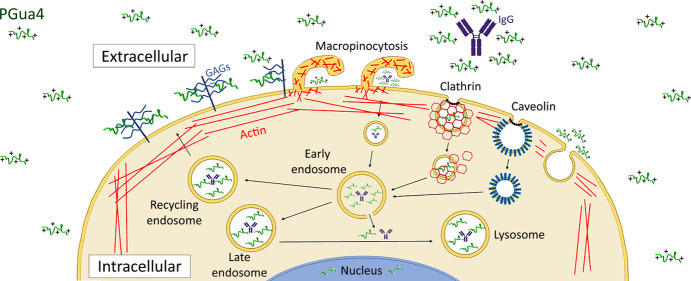

To investigate the structure-cellular penetration relationship of guanidinium-rich transporters (GRTs), we previously designed PGua4, a five-amino acid peptoid containing a conformationally restricted pattern of eight guanidines, which showed high cell-penetrating abilities and low cell toxicity. Herein, we characterized the cellular uptake selectivity, internalization pathway, and intracellular distribution of PGua4, as well as its capacity to deliver cargo. PGua4 exhibits higher penetration efficiency in HeLa cells than in six other cell lines (A549, Caco-2, fibroblast, HEK293, Mia-PaCa2, and MCF7) and is mainly internalized by clathrin-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis. Confocal microscopy showed that it remained trapped in endosomes at low concentrations but induced pH-dependent endosomal membrane destabilization at concentrations ≥10 μM, allowing its diffusion into the cytoplasm. Importantly, PGua4 significantly enhanced macropinocytosis and the cellular uptake and cytosolic delivery of large IgGs following noncovalent complexation. Therefore, in addition to its peptoid nature conferring high resistance to proteolysis, PGua4 presents characteristics of a promising tool for IgG delivery and therapeutic applications.

Keywords: cell-penetrating peptide, guanidinium-rich transporters, macropinocytosis, endosomal escape, IgG delivery

Introduction

The action of several therapeutic molecules is currently limited by their large size and polarity, which prevent them from crossing cellular membranes to reach intracellular targets and induce pharmacological response.1 To overcome this problem, several tools, such as cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs), have been developed. CPPs are short peptides of 5 to 35 amino acids that are able to penetrate the plasma membrane and deliver various cargos ranging from nanoparticles to macromolecules (e.g., siRNAs, DNAs, proteins, peptides, antibodies, and therapeutic agents).2−9 CPPs are classified into three categories: cationic, amphipathic, and hydrophobic.10 Cationic CPPs are generally arginine-rich peptides and are the most studied class of CPPs. Examples of this class of CPPs include the well-known TAT peptide, derived from the human immunodeficiency virus transactivator protein, penetratin, derived from the Drosophila antennapedia homeoprotein and various synthetic oligoarginine peptides.11−14 Despite their good cell-penetrating ability, clinical applications of cationic CPPs are limited due to their instability in the blood, lack of cell selectivity, and poor capacity to reach the cytoplasm to deliver their cargo due to entrapment in endosomes.15−17 CPPs are reported to enter cells by multiple pathways, depending on their structure and concentration and on the cargo attached to them.18 Currently, the field recognizes endocytosis to be the primary route for the cellular uptake of cationic CPP and subsequent endosomal escape, the rate-limiting step for the effectiveness of CPPs to deliver cargo into the cytoplasm of living cells.15,19 A better understanding of the mechanisms of uptake and release of these CPPs from the endosomal compartment is crucial to optimizing their cytosolic delivery.

The positively charged guanidinium group on arginine residues has been shown to be a key element for the cellular penetration of arginine-rich peptides.8,20−24 Guanidinium groups form bidentate hydrogen bonds with negatively charged components of the plasma membrane (e.g., sulfates, carboxylates, phosphate groups), such as glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), to enable internalization.20,25 Rigidification of the backbone structure of CPPs, restricting their flexibility and thus the presentation of guanidinium groups, has been shown to be an effective strategy to increase cellular uptake.26 Furthermore, peptoids (oligomers of amino acids in which the side chain is appended to the amine nitrogen instead of the α-carbon), which were initially conceived as synthetic peptide derivatives to improve the metabolic stability of peptides, have several other advantages over peptides, including a larger selection of side chains and better cell membrane permeability.27−29

To better understand the impacts of the structural parameters of the guanidinium moieties on cell permeation, our group previously designed peptoidic guanidinium-rich transporters (GRTs) bearing modular scaffolds that displayed conformationally restricted patterns of guanidines.30 We hypothesized that these restricted guanidinium conformations would help aid investigation of the chemical space of anionic cellular membrane components, such as GAGs, to support the development of structure-cellular penetration relationships. Peptoids bearing 4 to 12 guanidine residues were tested for cellular uptake in HeLa cells.30 The best compound of this class was a five-amino-acid peptoid containing eight positively charged guanidines, called PGua4. PGua4 showed low cell toxicity, an internalization level on the same order as that of nona-arginine, and was dependent on plasma membrane GAGs.30

In this new study, we characterized PGua4 stability, cellular uptake selectivity, the internalization pathway, intracellular distribution, and the capacity to escape endosomes and deliver cargo. Our results revealed that PGua4 is a promising transporter showing both resistance to proteolytic degradation and cell selectivity, which can moreover induce macropinocytosis and endosomal escape, allowing cytosolic delivery of IgGs following a simple precomplexation step in a test tube.

Experimental Section

DNA Constructs

The pmRFP-C3-Rab5 (#14437), pDsRed-C1-HA-Rab11 (#12679), and pmCherry-Gal3 (#85662) constructs were purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA). pmRFP-C3-Rab5-Q79L was generated by replacing glutamine with leucine at position 79 of Rab5 in the construct pmRFP-C3-Rab5 using the QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies). pmRFP-C3-Rab7 cDNA was kindly provided by Dr. Stéphane Lefrançois (Université de Montréal, Montréal, Canada). pmCherry-Gal3 was a gift from Hemmo Meyer (Addgene plasmid # 85662 ; http://n2t.net/addgene:85662; RRID:Addgene_85662). All constructs were submitted to nucleotide sequencing before use.

Reagents and Antibody

Cytochalasin D (#PHZ1063), Alexa Fluor 633 transferrin (#T23362), FITC transferrin (#T2871), Alexa Fluor 594 cholera toxin subunit B (#C22842), and Texas Red dextran (70,000 g/mol, #D1864) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). FITC cholera toxin subunit B (#C1655) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA), and CF488A dextran (70,000 g/mol, #80117) was purchased from Biotium (Fremont, California, USA). FuGENE 6 Transfection Reagent was purchased from Promega (Madison, Wisconsin, USA), and Lipofectamine 2000, Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (#A21207), and Hoechst (#804612) were purchased from Invitrogen (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Bafilomycin A1 (#88899-55-2) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Alexa Fluor 594 anti-Nuclear Pore Complex Proteins IgG (#682202) was purchased from Cedarlane (Burlington, Ontario, Canada).

Peptoid Synthesis

PGua4 (fluorescein-β-Ala-(N{(3,5-bis(2-(guanidino)ethoxy)) or (Ac-β-Ala-(N{(3,5-bis(2-(guanidino)ethoxy)) benzyl})4-NH2), PBn4 (fluorescein-β-Ala-(NPhe)4-NH2), Pam4 (fluorescein-β-Ala-(N{(3,5-bis(2-(amino)ethoxy))benzyl})4-NH2), R8 (fluorescein-β-Ala-Arg8-NH2), and R9 (fluorescein- β-Ala-Arg9-NH2) were chemically synthesized using a submonomer approach, as previously described.30 For the peptide PGua4-Cys (fluorescein-β-Ala-(N{(3,5-bis(2-(guanidino)ethoxy))benzyl})4-Cys-NH2), cysteine was coupled with resin prior to the synthesis of FITC-PGua4.

Synthesis of Covalently Linked FITC-PGua4-AF594-IgG

Bromoacetylation

To 500 μL of a commercial solution of IgG in PBS (1 mg, 6.7 nmol) at 4 °C was added 20 μL of a solution of NHS-bromoacetate (112 nmol) in DMF. The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. The excess reagent was then removed by filtration using an AMICON Ultra centrifugal filter (50 kDa). After washing four times with PBS, the solution of bromoacetylated IgG was collected and adjusted to 500 μL with PBS (1 mM EDTA, 0.02% NaN3).

Peptide Conjugation

A 500 μL solution of bromoacetylated IgG was mixed with 500 μL glycerol. PGua4-Cys powder (0.31 mg, 128 nmol) was then added to the IgG solution, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h. The IgG–PGua4 conjugate was purified by filtration using an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter (50 kDa). After four washes with PBS-glycerol (50:50), the solution of the conjugated product was collected and the volume was adjusted to 200 μL with the same solvent.

Cell Culture and Transfection

HeLa CCL-2 and MCF7 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Untransformed skin fibroblasts from healthy individuals (#GM05399) were purchased from Coriell Institute (Camden, NJ, USA). HEK293, A549, Caco-2, and Mia-PaCa2 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Alexandra Newton (University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA), Dr. Richard Leduc (Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Canada), Dr. Michel Grandbois (Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Canada), and Dr. Marie-Josée Boucher (Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Canada), respectively. A549, Caco-2, HeLa, HEK293, fibroblast, and Mia-PaCa2 cells were grown in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Wisent Inc., Saint-Jean-Baptiste, QC, Canada), and MCF7 cells were grown in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM) with l-glutamine and Earle’s salts (Wisent Inc., Saint-Jean-Baptiste, QC, Canada). All culture media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin–glutamine solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Caco-2 and Mia-PaCa2 were supplemented with 2 mM GlutaMAX (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Mia-PaCa2 was also supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (Wisent Inc., Saint-Jean-Baptiste, QC, Canada). Unless otherwise mentioned, all incubation sequences were performed at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. HeLa cells were transfected with FuGENE 6 or Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagents according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA Interference

siRNAs against human clathrin heavy chain (siGENOME SMART pool siRNA CHC, #M-004001-00), against human caveolin 1 (siGENOME SMART pool siRNA CAV1, #M-003467-01), against human dynamin2 (siGENOME SMART pool siRNA DNM2, #M-004007-03), and control siRNA (siGENOME Non-Targeting siRNA Pool #2, #D-001206-14) were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, Colorado, USA). HeLa cells were plated in 60 mm culture dishes and transfected the next day with siRNAs (final concentration of 100 nM) using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h, the cells were plated in 24-well plates (6 × 104 cells/well) for flow cytometry analysis or 35 mm glass-bottom dishes (12 × 104 cells) for confocal microscopy analysis. The cells were analyzed 72 h after siRNA transfection. The protein knockdowns were confirmed by Western blotting.

Flow Cytometry

A594 (1.2 × 105), Caco-2 (1.2 × 105), fibroblast (6 × 104), HEK293 (1.2 × 105), HeLa (6 × 104), MCF7 (1.2 × 105), and Mia-PaCa2 (1.2 × 105) cells were plated in 24-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) and grown in their respective media for 24 h. On the day of the experiment, cells were washed and incubated with fresh medium containing FITC-labeled peptoids (5 μM), transferrin (25 μg/mL), or dextran (0.5 mg/mL) for 10 or 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were placed on ice and washed two times for 30 s with a low-pH solution (0.15 M NaCl, 0.2 M glycine, pH 3.0) and cold PBS containing 0.5 mg/mL heparin for an additional 30 s (to remove cell-surface peptoids, transferrin, and dextran). The cells were then detached with Trypsin–EDTA 0.25% (Wisent, Quebec, Canada); resuspended in PBS buffer containing 10 mg/mL propidium iodide (PI, to exclude debris and dead cells), 0.05% w/v Trypan Blue (to quench remaining extracellular fluorescence), and 5% FBS (to neutralize trypsin); and transferred to a 96-well plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) for flow cytometry analysis. A total of 10,000 gated events per sample were acquired and analyzed by a CytoFLEX B4-R2-V0 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) with 50 mW diode lasers tuned at 488 and 638 nm equipped with an automatic 96-well plate loader. The emitted fluorescence was split and collected through 525/40 nm (FITC) and 585/42 nm (PI) bandpass filters. The mean of the signal for each experiment was determined by the average of three independent experiments. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

Confocal Microscopy

For live cell confocal microscopy analysis, HeLa cells (6 × 104) were plated in 35 mm glass-bottom dishes (MatTek Corporation). On the day of the experiments, the cells were washed in PBS and incubated with 5 μM FITC-PGua4, 25 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 633 transferrin, 2 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 594 cholera toxin B, or 0.5 mg/mL Texas Red-Dextran 70 at 37 °C for different periods of time (according to the experiments) in complete DMEM without phenol red (Gibco). The cells were then washed with PBS, and Hoechst #804612 (1 μg/mL) was added to the cells for 5 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed three times with PBS, and 1 mL of complete medium (made with DMEM without phenol red) was added to the cells immediately before analysis. To keep the cells at 37 °C with 5% CO2, Petri dishes were placed in a microchamber (Okolab, NA, Italy) attached to the stage of the microscope. Images were acquired with a scanning confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP8 STED DMI8, Leica Microsystems, Toronto, ON, Canada) equipped with a 63×/1.4 oil-immersion objective and a tunable white light laser (470 to 670 nm). The fluorophores or fluorescent proteins FITC, Alexa Fluor 594, Alexa Fluor 633, Texas Red, red fluorescent protein (RFP), and mCherry were excited with the 488, 594, 633, 596, 555, and 587 nm laser lines of the white light laser, respectively, and emissions were detected with a HyD detector. When the levels of internalization of PGua4 or endocytic markers (Tf, CTB, or Dex) or cytoplasmic IgGs were compared between different conditions, images were acquired using identical instrument settings. LAS AF Lite software (Leica) was used for image acquisition and analysis. The images were further processed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

Macropinocytosis Inhibition

HeLa cells were starved for 1 h at 37 °C. The cells were then pretreated with 10 μM cytochalasin D or vehicle (DMSO) in DMEM for 15 min at 37 °C before incubation in the same medium containing 0.5 mg/mL Texas Red dextran and/or 5 μM FITC-PGua4 for an additional 10 min at 37 °C. The cells were next prepared for flow cytometry or confocal microscopy analysis.

Actin Reorganization

HeLa cells were transfected with pCMV-LifeAct-TagRFP using the FuGENE 6 Transfection Reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were starved for 2 h and incubated in the absence or presence of 5 μM FITC-PGua4 for 1 h at 37 °C. Images of cells were acquired by live-cell confocal microscopy.

Endosomal Distribution Analysis

HeLa cells were transfected with either pmRFP-C3-Rab5 (wild-type or Q79L), pmRFP-C3-Rab7, or pDsRed-C1-Rab11 using the FuGENE 6 Transfection Reagent. After 24 h, the cells were washed and incubated with 5 μM FITC-PGua4 for 30 or 75 min at 37 °C. Images of cells were acquired by live-cell confocal microscopy.

Endosomal Escape Analysis

HeLa cells were incubated with either 5, 10, 20, or 30 μM FITC-PGua4 in complete DMEM (without phenol red) for 30 min at 37 or 4 °C. For bafilomycin treatment, HeLa cells were preincubated with 100 nM bafilomycin in complete medium for 1 h and incubated with 10 μM FITC-PGua4 for an additional 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were then analyzed by live-cell confocal microscopy.

Galectin-3 Assay

HeLa cells were transfected with pmCherry-Galectin-3 using the FuGENE 6 Transfection Reagent for 24 h. Cells were washed with PBS and incubated with or without 10 μM FITC-PGua4 in complete DMEM for 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were then analyzed by live-cell confocal microscopy.

Intracellular IgG Delivery

HeLa cells (6 × 104) were plated in 35 mm glass-bottom dishes. The next day, complexes between IgGs and PGua4, R8, or R9 were formed by mixing 0.3 μM Alexa Fluor 594-IgG together with 20, 40, or 60 μM FITC-PGua4, FITC-R8, or FITC-R9 in Opti-MEM (total volume 250 μL) for 1 h at room temperature. The complexes were then diluted with 250 μL of Opti-MEM (final concentrations: 0.15 μM Alexa Fluor 594-IgG and 10, 20, and 30 μM FITC PGua4 or 20 μM FITC-R8 or -R9), added to the cells (medium previously removed), and incubated for 45 min at 37 °C. Without changing the medium, 1.5 mL of complete medium was added to the cells and incubated for 3, 16, or 24 h at 37 °C. The cells were then analyzed by confocal microscopy. The percentage of cells with a cytosolic distribution of Alexa Fluor 594-IgG was determined by counting the total number of cells (nuclei labeled with Hoechst) and the number of cells with a cytosolic distribution of Alexa Fluor 594 fluorescence from 10 visual fields (per experiment) and from three independent experiments (≥250 total cells). Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

Delivery of Anti-Nuclear Pore Complex Proteins (NPC) IgG

The experiment was performed as described in the Intracellular IgG Delivery section, except that complexes were formed by mixing 22.6 μg/mL of Alexa Fluor 594-NPC IgGs together with 40 μM FITC-PGua4 in Opti-MEM (for a final concentration of 11.3 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 594-NPC IgGs and 20 μM FITC PGua4). The cells were then analyzed on an LSM Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope equipped with a 60×/1.35 oil-immersion objective and diode 405 nm and HeNe 543 nm lasers. Petri dishes were placed at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a microchamber (Okolab, NA, Italy) attached to the stage of the microscope. FV10-ASW 4.2 Viewer software (Olympus) was used for image acquisition and analysis. The images were further processed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism version 8.2.1 or 9.3.0 (GraphPad Software) using one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons (for Figures 1D, 2C, 3B, 6B, and 8B,E), two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons (for Figure 1D, Table S1 and S2), one-sample Wilcoxon test (for Figure 4B,C), and unpaired t-test (for Figure S4). Data were considered significant when p values were < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Analysis of the cellular uptake of PGua4 and its analogs. (A) Structure of the guanidinium-rich peptoid PGua4, (B) the backbone analog PBn4, and (C) aminated analog PAm4. All structures are covalently linked to the fluorophore FITC with a β-Ala spacer. (D) Cellular uptake of FITC-PGua4, -PBn4, and -PAm4 in A549, Caco-2, fibroblast, HEK293, HeLa, MCF7, and Mia-PaCa2 cells analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of each peptide (5 μM) for 30 min at 37 °C, washed with PBS, trypsinized, and treated with trypan blue and PI before FACS analysis. Error bars represent the mean ± S.D. of n ≥ 3 independent experiments. One-way ANOVA test, *p < 0.001; **p < 0.0001 represent PGua4 vs analog peptides. #p < 0.0001 of two-way ANOVA test of PGua4 uptake in HeLa cells versus all the other cell lines. Statistical analyses of PGua4 and PAm4 uptake between the different cell lines are detailed in Tables S1 and S2.

Figure 2.

PGua4 is internalized by clathrin- and dynamin-mediated endocytosis. (A) Time-course analysis of PGua4 internalization at 37 or 4 °C. HeLa cells were incubated with 5 μM FITC-PGua4 for 3, 5, 10, and 30 min at 37 or 4 °C and then analyzed by live-cell confocal microscopy. Scale bars, 10 μm. Each cell is delimited by a white line. (B, C) Effects of caveolin, clathrin, and dynamin depletion on PGua4 internalization. HeLa cells were treated with control, caveolin, clathrin, or dynamin siRNA for 72 h. Cells were then incubated with 25 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 594-transferrin (Tf), 2 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 594-cholera toxin B (CTB), or 5 μM FITC-PGua4 for 30 min at 37 °C. In (B), cells were analyzed by live confocal microscopy. Scale bars, 10 μm. In (C), cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Mean fluorescence was normalized to the siRNA control conditions (100%). Error bars represent the mean ± S.D. of n ≥ 3 independent experiments. One-way ANOVA test, **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001, ns, not significant.

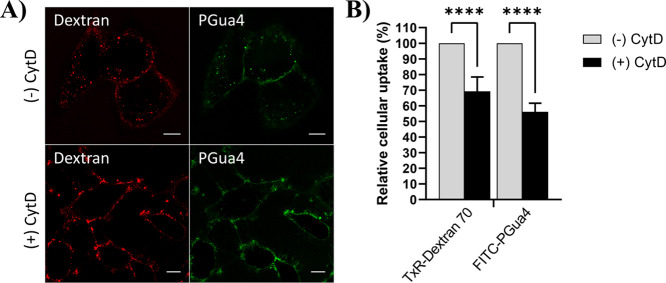

Figure 3.

PGua4 is internalized by macropinocytosis. Serum-starved HeLa cells were pretreated with the macropinocytosis inhibitor cytochalasin D (CytD, 10 μM) for 15 min prior to incubation with FITC-PGua4 (5 μM) or Texas Red-Dextran 70 (Dex70, 0.5 mg/mL) for 10 min in the presence of CytD. In (A), cells were analyzed by live cell confocal microscopy. Scale bars, 10 μm. In (B), cellular internalization was quantified by flow cytometry. Mean fluorescence was normalized to the condition without CytD (100%). Error bars represent the mean ± S.D. of n ≥ 3 independent experiments. One-way ANOVA test, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 6.

Cytosolic delivery of PGua4. (A) HeLa cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of FITC-PGua4 (5, 10, 20, and 30 μM) for 30 min at 37 or 4 °C and analyzed by live cell confocal microscopy. Scale bars, 10 μm. (B) Quantification of the proportion of cells with cytosolic distribution of FITC-PGua4 analyzed under the different conditions described in (A). Error bars represent the mean ± S.D. of n ≥ 3 independent experiments. One-way ANOVA test, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ns, not significant. (C) Effect of endosomal acidification on cytosolic delivery of PGua4. HeLa cells were preincubated with or without 100 nM bafilomycin for 1 h and incubated with 10 μM FITC-PGua4 for an additional 30 min at 37 °C. Images were acquired by live cell confocal microscopy. Scale bars, 10 μm. In (A) and (C), white arrows show cells with both nucleolar and cytosolic staining.

Figure 8.

Cytosolic delivery of immunoglobulin G (IgGs) by PGua4. PGua4 was mixed with AF594-IgGs or AF594-anti-NPC IgGs with OptiMEM in a test tube and incubated for 1 h at RT. Cells were treated for 45 min at 37 °C with the complexes that were previously diluted by half in OptiMEM (final concentrations are indicated in the figures). Complete medium was next added to the cell and further incubated at 37 °C before imaging by confocal microscopy. In (A), cells were incubated with complexes combining 0.15 μM AF594-IgG and increasing concentrations of PGua4 (0, 10, 20, 30 μM) for 24 h at 37 °C. In (C), cells were incubated with complexes combining 0.15 μM AF594-IgG and 20 μM PGua4 for increasing incubation times (3, 16, and 24 h) at 37 °C. In (A) and (C), the white asterisks indicate cells with cytosolic distribution of AF594-IgG. Scale bars, 10 μm. In (D), cells were incubated with 0.15 μM of covalently linked FITC-PGua4-AF594-IgG for 24 h at 37 °C. Scale bars, 10 μm. (B, E) Quantification of the proportion of cells with cytosolic distribution of AF594-IgG analyzed in the different conditions described in (A, C, D). Error bars represent the mean ± S.D. of n ≥ 3 independent experiments. One-way ANOVA test, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ns, not significant. In (F), cells were incubated with complexes combining 20 μM FITC-PGua4 together with 11.3 μg/mL AF594-NPC-IgG or AF594-control IgG for 24 h. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst before imaging. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Figure 4.

PGua4 stimulates the uptake of Dextran 70 and actin reorganization. (A) Comparison of the uptake of Dextran 70 without or with PGua4. HeLa cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/mL Texas Red-Dextran 70 in the absence or presence of 5 μM FITC-PGua4 for 3, 5, 10, and 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were analyzed by live confocal microscopy. Scale bars, 10 μm. (B, C) Flow cytometry analysis of the uptake of 0.5 mg/mL CF488A-Dextran 70 (B) or 25 μg/mL FITC-transferrin (C) in cells incubated with or without 5 μM Ac-PGua4 (nonfluorescent) for 10 min at 37 °C. Error bars represent the mean ± S.D. of n ≥ 3 independent experiments. One-sample Wilcoxon test, *p < 0.05 and ns (not significant). (D) Actin rearrangement induced by PGua4. Starved HeLa cells expressing LifeAct-RFP were treated without (CTL) or with 5 μM FITC-PGua4 for 1 h at 37 °C and analyzed by live cell confocal microscopy. White arrows show membrane protrusions. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Results

PGua4 Penetration Efficiency Is Cell-Line Dependent

To characterize the cell-penetrating abilities of PGua4 (Figure 1A), its cellular uptake was evaluated in seven human cell lines selected based on their different human tissue origins and their cancerous and non-cancerous origins: lung cancer A549, colorectal cancer Caco-2 cells, cervical cancer HeLa cells, breast cancer MCF7 cells, pancreatic cancer Mia-PaCa2 cells, embryonic kidney HEK293 cells, and primary skin fibroblast. PGua4 uptake was also compared to the nonfunctionalized backbone analog PBn4 (Figure 1B) and aminated analog PAm4 (Figure 1C) with equivalent positive charges. The cells were incubated with or without 5 μM of these fluorescein (FITC)-labeled compounds for 30 min at 37 °C, and the cellular uptake was determined by flow cytometry (Figure 1D). The penetration of PGua4 in all cell lines was statistically higher than that of the analogs PBn4 and PAm4, indicating that the backbone and positive charges of PGua4 are not primarily responsible for its uptake. Furthermore, significant differences were observed between the different cell lines (Figure 1D, Table S1). The uptake of PGua4 was statistically higher in HeLa cells than in all the other cell lines (p < 0.0001) and lower in MCF7 cells (except HEK293 cells with p = 0.057). A similar uptake was observed between A549, Caco-2, and Mia-PaCa2 cells and between HEK293 cells and skin fibroblasts. In summary, the level of PGua4 uptake in the different cell lines was HeLa > Caco-2 = Mia-PaCa2 = A549 ≥ fibroblast = HEK293 ≥ MCF7. Of note, such cell selectivity was not observed with the uptake of PAm4 (Table S2). Together, these results indicate that the guanidine groups of PGua4 are important pharmacophores contributing to a higher cellular penetration rate and cell selectivity.

PGua4 Internalization Is Mediated by Clathrin-Dependent Endocytosis and Macropinocytosis

Cationic CPPs are reported to gain entry into the cell by multiple pathways, including endocytosis and direct penetration.18 We thus investigated the PGua4 internalization mechanism and distribution using live-cell confocal microscopy in HeLa cells, given that PGua4 cellular uptake was higher in these cells. Following a 3 to 30 min incubation period with 5 μM FITC-PGua4 at 37 °C, the distribution of FITC-PGua4 was rapidly observed in a punctate intracellular fluorescence pattern (Figure 2A), suggesting that PGua4 enters cells via endocytosis and localizes within intracellular vesicles.

To determine whether an energy-dependent mechanism mediates the uptake of PGua4, low-temperature treatment was performed, as it suppresses all active endocytosis processes, but not direct translocation through the cell membrane (passive cell penetration).31 Live-cell confocal images shown in Figure 2A indicate that PGua4 internalization was significantly impeded at 4 °C, confirming that an energy-dependent endocytic pathway internalizes PGua4.

To identify the endocytic pathway involved in the uptake of PGua4, cells were treated with siRNA interfering with individual internalization pathways and then analyzed by live-cell confocal microscopy. The role of caveolae in the uptake of PGua4 was evaluated using caveolin-1 (CAV1) siRNAs that knocked down the expression of this major caveolae component (Figure S1). The uptake of FITC-PGua4 was maintained in CAV1-depleted cells following a 30 min incubation period (Figure 2B), whereas the internalization of Alexa Fluor 594-cholera toxin subunit B (CTB), a classical marker of caveolin-mediated endocytosis, was completely inhibited.32 In concordance, flow cytometry analysis showed a nonsignificant reduction in PGua4 uptake in these cells (Figure 2C), indicating that the endocytosis of PGua4 is not mediated by caveolae.

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis was selectively inhibited with clathrin heavy chain (CHC) siRNAs, which knocked down the expression of this key clathrin coat component (Figure S1). As expected, clathrin depletion inhibited the internalization of Alexa Fluor 594 Tf, a classical marker of clathrin-mediated endocytosis, following a 30 min incubation period (Figure 2B).33 In contrast, the internalization of FITC-PGua4 was only partially inhibited in these cells, since some intracellular vesicles were observed in addition to an accumulation at the cell surface (Figure 2B). These results were quantified by flow cytometry, which indicated that clathrin depletion decreased the internalization of Tf by 38.6%, but that of PGua4 by only 20.1% (Figure 2C), suggesting that clathrin is partially involved in PGua4 internalization. The implication of clathrin vesicles in PGua4 uptake was confirmed with the depletion of dynamin (Figure S1), a critical GTPase for clathrin- and caveolin-vesicle scission and release from the plasma membrane.34,35 Indeed, the same level of inhibition of PGua4 uptake was observed in dynamin knockdown and clathrin knockdown cells (Figure 2C), indicating that PGua4 is partially internalized by a clathrin- and dynamin-mediated pathway.

The contribution of macropinocytosis to the cellular uptake of PGua4 was next examined using cytochalasin D (CytD), a fungal metabolite that inhibits actin polymerization, a critical step in macropinocytosis.36 Confocal microscopy analysis showed that treatment with CytD inhibited the internalization of Texas Red-labeled dextran (70,000 MW, Dex70), a gold standard marker of macropinocytosis (Figure 3A), but did not alter the uptake of the clathrin-mediated endocytosis marker Tf (Figure S2), which was sometimes reported to be perturbed in the presence of this inhibitor.37,38 The cellular uptake of FITC-PGua4 was strongly reduced following a 10 min incubation period at 37 °C in the presence of CytD and was mainly observed at the cell surface (Figure 3A). Flow cytometry analysis quantified a 44% reduction in PGua4 peptide uptake compared to untreated cells, suggesting that macropinocytosis contributes mainly to the uptake pathway of PGua4 (Figure 3B). In summary, these results indicate that PGua4 is internalized by both clathrin-dependent endocytosis and macropinocytosis.

PGua4 Induces Actin Reorganization and Macropinocytosis

Macropinocytosis is a constitutive mechanism that shuttles both cell surface-associated and fluid phase elements into cells.39,40 Some arginine-rich peptides (e.g., R8 and TAT) have been shown not only to enter cells by macropinocytosis but also to induce macropinocytosis.41,42 The ability of PGua4 to stimulate macropinocytosis was tested by comparing the cellular uptake of fluorescent Dex70 at different periods of time in the absence or presence of 5 μM PGua4. Live-cell confocal images showed a marked increase in the fluorescence intensity of dextran in cells treated with PGua4 compared to untreated cells, and this increase was observed at all time points (Figure 4A). Flow cytometry analysis after a 10 min incubation period indicated a twofold increase in Dex70 internalization in cells treated with PGua4 compared to control cells (Figure 4B). In contrast, the presence of PGua4 did not alter the uptake of the clathrin-mediated endocytic marker Tf (Figure 4C), indicating that PGua4 specifically induces the macropinocytic pathway.

Macropinocytosis is well documented to lead to actin cytoskeleton reorganization, which allows the formation of lamellipodia.43,44 To examine the effect of PGua4 on the morphology of the actin cytoskeleton, live-cell imaging was performed on HeLa cells expressing the F-actin binding peptide LifeAct tagged with RFP (LifeAct-RFP)45 and incubated in the absence or presence of 5 μM PGua4 for 30 min. Figure 4D shows significant actin rearrangement and lamellipodium-like structures in cells treated with PGua4 compared to control cells. These results suggest that PGua4 treatment induces actin reorganization associated with macropinocytosis. Together, these results firmly suggest the ability of PGua4 to activate macropinocytosis and drive the uptake of the marker Dex70.

Intracellular Fate of PGua4

One of the main drawbacks of cationic CPPs is that following their internalization by endocytosis, they largely remain trapped in the endocytic pathway and are eventually targeted for degradation or recycling rather than being released into the cytoplasm or trafficked to a desired subcellular destination.15,19 To identify the intracellular fate of internalized PGua4, we next followed its trafficking in the recycling and degradation pathways following its internalization. To identify these pathways, cells were transfected with different fluorescent-tagged Rab proteins as markers of the endocytic pathways. Rab5 is a marker of early endosomes, Rab7 is a late endosome marker for degradation in lysosomes, and Rab11 is a recycling endosome marker.46−49 Cells were then treated with 5 μM FITC-PGua4 for 30 and 75 min at 37 °C, and colocalization was analyzed by live-cell confocal microscopy (Figure 5). After 30 min, PGua4 colocalized mainly with Rab5 and Rab11, indicating that it reached the early and recycling endosomes. However, after an extended period of incubation (75 min), PGua4 was observed in Rab5-, Rab7-, and Rab11-labeled endosomes. Of note, Rab5-Q79L is a constitutively active form of Rab5 that causes the formation of enlarged early endosomes50 and facilitates the detection of PGua4 in the endosomal lumen. While some PGua4 is observed lining the endosomal membranes at 30 min, it appears mainly in the lumen at 75 min. Furthermore, PGua4 is detected in the cytoplasm at neither of these time points. Colocalization of PGua4 with wild-type Rab5 was also confirmed (Figure S3). These results indicate that at a concentration of 5 μM, PGua4 primarily remains trapped in the endocytic pathway and will therefore be either recycled or degraded.

Figure 5.

Endosomal distribution of PGua4. HeLa cells expressing RFP-Rab5-Q79L (early endosomes), RFP-Rab7-WT (late endosomes), and DsRed-Rab11-WT (recycling endosomes) were incubated with FITC-PGua4 (5 μM) for 30 or 75 min at 37 °C and analyzed by live cell confocal microscopy. Scale bars, 10 μm.

PGua4 Endosomal Escape Is Concentration Dependent

Endosomal escape is an inefficient process; concentrations above 10 μM of Arg-rich CPP are typically required to generate a detectable cytoplasmic fluorescent signal.31 We sought to test whether higher concentrations of PGua4 can be detected in the cytosol. HeLa cells were incubated with 5, 10, 20, and 30 μM FITC-PGua4 for 30 min at 37 °C and analyzed by live-cell confocal microscopy (Figure 6A). These concentrations have been previously shown to be noncytotoxic.30 PGua4 localized mainly within vesicular structures at all concentrations, indicating predominant encapsulation into endosomes. At 5 μM, cytosolic PGua4 is absent or too low to be detected by fluorescence. However, at a concentration ≥ 10 μM, fluorescence was detected in the cytoplasm and nucleus (abundant in the nucleolus) and increased with peptide concentration, suggesting that a fraction of PGua4 translocated into the cytosol. Quantification of the percentage of total cells with cytosolic distribution of PGua4 indicated that the highest cytosolic distribution (85%) was observed with 20 μM PGua4 (Figure 6B). To exclude the possibility that cytosolic import was a result of damage to the plasma membrane, the membrane integrity was confirmed using PI (data not shown). It has been reported that higher concentrations of Arg-rich CPPs can modify corresponding uptake mechanisms, leading to alternative endocytic routes or even nonendocytic import, causing rapid cytosolic delivery.51 Therefore, we examined whether the uptake and endosomal escape at higher concentrations of PGua4 were mediated by an energy-dependent mechanism. Figure 6A shows that low-temperature treatment inhibits the uptake and cytosolic localization of 5, 10, 20, and 30 μM PGua4, indicating that the cytosolic distribution observed at higher concentrations does not involve energy-independent direct penetration. Interestingly, the internalization and endosomal escape of PGua4 are not altered by the presence of FBS in the culture medium (Figure S4), which has been previously reported to inhibit cell delivery of arginine-rich CPPs.52−55 Furthermore, macropinocytosis was identified as the main internalization pathway of 5 μM PGua4 (Figure 3). Inhibition of macropinocytosis with CytD also blocked the uptake and cytoplasmic distribution of PGua4 at higher concentrations (10 μM) (Figure S5). Taken together, these results indicate that higher concentrations of PGua4 do not alter the internalization pathway of PGua4 but increase its cytosolic delivery.

Endosome maturation and acidification are involved in the ability of Arg-rich CPP to escape to the cytoplasm.56 We therefore measured the effect of blocking endosome acidification on the ability of 10 μM PGua4 to reach the cytoplasm. Cells were treated with bafilomycin A1, a specific inhibitor of vacuolar proton ATPases that dissipates the low endosomal pH and blocks transport from early to late endosomes.57,58Figure 6C shows no cells with diffuse cytosolic and nuclear PGua4 signals when incubated in the presence of bafilomycin A1. This finding supports the hypothesis that PGua4 escapes to the cytoplasm from acidified endocytic vesicles. To further understand the endosomal escape pathway induced by PGua4, we studied the recruitment of the endosomal repair protein galectin-3 (Gal3). Gal3 is a reported marker for endosomal damage, as it binds to luminal β-galactosides that become exposed to the surface of endolysosomal compartments following membrane disruption.9,59,60 Cells expressing mCherry-Gal3 were incubated in the absence or presence of FITC-PGua4 for 30 min and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Figure 7). Without PGua4, cells exhibit homogeneous fluorescence due to cytosolic mCherry-Gal3. However, when treated with 10 μM PGua4, particularly in cells exhibiting cytoplasmic FITC-PGua4, a distinct punctate mCherry-Gal3 signal was detected (white arrows), which is consistent with its recruitment to damaged endosomes. These results suggest that in the endosomal acidic environment, PGua4 (at concentrations ≥10 μM) destabilizes the endosomal membrane, allowing its diffusion into the cytoplasm.

Figure 7.

PGua4 induces endosomal membrane perturbation/destabilization. Live cell confocal microscopy images of HeLa cells expressing mCherry-Galectin-3 (a sensor of endosomal membrane disruption) after treatment without (−) or with (+) 10 μM FITC-PGua4 for 30 min at 37 °C. White arrows show cells with an accumulation of intracellular Gal3 foci, as evidence of membrane destabilization. Scale bar, 10 μm.

PGua4 Resistance to Proteolysis

Peptoids have several advantages over peptides, including excellent resistance to biodegradation due to their unnatural skeletal structure.27−29,61 To examine the resistance to proteolytic cleavage, PGua4 was incubated with trypsin for 6 h at 37 °C (Figure S6). As expected, PGua4 (10 μM) showed strong resistance to degradation, whereas the control peptide octa-arginine (R8), a peptide bearing eight guanidiniums, was almost completely degraded after 30 min. This result confirmed that the peptoid nature of PGua4 is less sensitive to degradation, suggesting better metabolic stability.

PGua4 Allows Cytoplasmic Delivery of IgGs

The ability of PGua4 to induce macropinocytosis and escape endosomes is considered a significant advantage for the delivery of large cargos to intracellular targets. We therefore used full-length immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies (150 kDa), as a model cargo. Furthermore, intracellular delivery of functional antibodies is currently of high interest for therapeutic applications .62,63 Cargo linked through noncovalent interactions (mixing the cargo and CPP in the test tube) is a simple strategy previously used to introduce a wide variety of cargos into the cytoplasm of living cells, including IgGs.64,65 We used this approach to evaluate the ability of PGua4 to promote the cytosolic delivery of IgGs. For this assay, a fixed concentration of Alexa Fluor 594-tagged IgG (AF594-IgG) was first mixed in a test tube with different concentrations of FITC-PGua4 (at twice the final concentrations of 0, 10, 20, and 30 μM) for 1 h at room temperature for complex formation. These concentrated mixtures were next diluted twice and added to HeLa cells for 45 min before the addition of complete medium and further incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. In the live-cell confocal images shown in Figure 8A, AF594-IgGs were not significantly delivered into cells without PGua4, suggesting that because of their large size and physicochemical properties, IgGs are membrane impermeable and not efficiently endocytosed. In complex with 10 μM PGua4, AF594-IgGs are observed in intracellular punctate structures but not in the cytosol, suggesting internalization and entrapment within endosomes. Of note, in some cells, PGua4 is located in the cytosol, whereas AF594-IgGs are only located in endosomes, suggesting that PGua4, but not IgGs, can escape from endosomes. However, complex formation with 20 and 30 μM PGua4 led to cytoplasmic delivery of AF594-IgGs. The percentage of cells with a cytosolic distribution of AF594-IgGs was highest (31.7%) for the mixture of 0.15 μM IgGs and 20 μM PGua4 (final concentration added to cells) (Figure 8B). Unexpectedly, diffuse IgG labeling was also detected into the nucleus of some cells (Figure 8A). It can be explained by the degradation of antibodies (before or after their endosomal escape) into IgG fragments that can passively enter the nucleus (proteins with size up to 110 kDa have been shown to passively diffuse through the nuclear pore of HeLa cells)66 or the complexation with PGua4 also delivers intact IgGs in the nucleus via an unknown mechanism.

Doubling the amount of IgGs in the complex mixture (0.3 μM IgGs and 20 μM PGua4) did not help detect the presence of IgGs in the cytoplasm (Figure S7); it even decreased IgG fluorescence detected in the cytosol, indicating that the mixture of 0.15 μM IgG:20 μM PGua4 (final concentrations) is the most effective for cytosolic IgG delivery. To determine the optimal incubation time required for cytosolic IgG delivery by PGua4, cells were incubated with the 0.15 μM IgG:20 μM PGua4 complex (final concentrations) for 3, 16, and 24 h (Figure 8C). Cellular internalization of AF594-IgG was observed after 3 h of incubation, but its presence in the cytosol was detectable only after 16 and 24 h of incubation (Figure 8C). Quantification indicated that 0, 11, and 32% of the total cells showed cytoplasmic delivery of AF594-IgGs after 3, 16, and 24 h of incubation, respectively (Figure 8E). Furthermore, using CytD treatment, we demonstrated that, as shown for PGua4, the IgG:PGua4 complex is mainly internalized via macropinocytosis (Figure S8).

We next tested whether complex formation was a necessary step for the cytosolic delivery of IgG. Here, 0.15 μM IgGs and 20 μM PGua4 were coadded (without the complexation step) to cells and incubated for 24 h before confocal microscopy analysis. Interestingly, IgGs were detected in punctate endosomal structures but were not detected in the cytosol (Figure S9), indicating that complexation was crucial for the cytoplasmic delivery of IgGs. Given that covalent conjugation is a method frequently used to couple cargos to CPPs,67,68 we next tested whether it would be a more efficient delivery method. AF594-IgGs were covalently coupled to FITC-PGua4 using a previously reported method69 and added to cells at a final concentration of 0.15 μM for 24 h before analysis by confocal microscopy. As shown in Figure 8D,E, AF594-IgGs covalently coupled to PGua4 were internalized but remained trapped in the endosomes and did not reach the cytoplasm. These results suggest that while the covalent coupling of IgGs to PGua4 allowed their internalization in endosomes, probably due to the capacity of PGua4 to induce macropinocytosis, it did not allow their endosomal escape in the cytoplasm. In summary, these results indicate that noncovalent complexation with PGua4 is the only method that allows IgG cellular uptake by macropinocytosis and endosomal escape for delivery into the cytoplasm. To determine whether PGua4’s capacity to deliver IgGs was simply due to the presence of guanidiniums, IgG delivery assay was repeated with two prototypical linear arginine-rich permeant peptides, R8 and R9, which were previously reported to import a variety of biological molecules into cells.62,70,71 Of note, we previously reported that the uptake of PGua4 was about 20% lower than R8 and R9.30 Pre-complexation with FITC-R8 and -R9 yielded endosomal presence but no significant cytosolic appearance of AF594-IgGs (Figure S10). This result suggests that the arginine composition is not the only element involved in the ability of PGua4 to deliver cargos in the cytoplasm; the structure of PGua4 seems critical for its IgG delivery ability.

Finally, to assess whether the IgGs delivered by PGua4 retained their ability to target intracellular proteins, the delivery assay was performed with AF594-labeled anti-nuclear pore complex protein (NPC) antibodies targeting the nuclear membrane. Although not very frequent, significant labeling of the nuclear periphery was detected in some cells when the anti-NPC antibodies were precomplexed with PGua4 but was never detected with control IgGs (Figure 8F). This result suggests that, even if IgG degradation occurs before and after their endosomal escape in the cytoplasm, a fraction of the cytosolic IgGs was functional and in sufficient quantities in some cells to detect their target proteins.

Discussion

Cationic CPPs are promising tools as intracellular delivery vectors. However, they have shown some inherent limitations, including poor stability, endosomal entrapment, suboptimal cell penetration, and selectivity as well as toxicity. Here, we investigated/characterized the impact of conformational restriction of PGua4, a guanidinium-rich peptoid bearing a conformationally restricted guanidinium display scaffold, on the stability, cellular uptake, endosomal escape, and intracellular delivery of cargo. Our results revealed that PGua4 shows resistance to proteolytic degradation and cell selectivity and allows cytosolic delivery of IgGs by inducing macropinocytosis and endosomal escape.

We previously published the finding that the uptake of PGua4, bearing eight guanidine groups, was superior to those of similar scaffolds bearing 10 or 12 guanidines.30 Here, we showed the cellular selectivity of PGua4 given the significantly higher penetration efficiency in HeLa cells compared to six other cell lines (A549, Caco-2, fibroblast, HEK293, MCF7, and Mia-PaCa2). Because we previously showed that PGua4 uptake is decreased in GAG-depleted cells, we suggest that the variation in GAG composition between different cell types may explain the cellular selectivity.30,72−74 Further comparison of PGua4 uptake between different cell lines and primary cells as well as the level and composition of GAGs of the different cell lines will be necessary to better understand the nature of its preference for specific cell types and for further optimization of its structure to enable use as a therapeutic carrier with minimal off-target effects.

Understanding the carrier peptide internalization mechanism and intracellular pathway is fundamental to their use as delivery vectors (for overall safety and efficacy assessment). Our results indicate that PGua4, at a concentration of 5 μM, is internalized only by endocytic energy-dependent mechanisms: mainly by macropinocytosis and clathrin-mediated endocytosis. This multientry mode is similar to what has been reported for other arginine-rich CPPs at low concentrations (≤5 μM), including TAT and octa-arginine (R8), which enter by macropinocytosis, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and passive transport, and nona-arginine (R9), which enters by macropinocytosis and clathrin- and caveolin-mediated transport.41,42,51,75−77 Despite a large number of studies on Arg-rich CPPs, their fundamental mechanism of action to penetrate cells remains a subject of controversy given that their mode of entry is reported to be dependent on their concentration, the cargo attached to the peptide, and the structural properties of the plasma membrane (lipid and protein composition/fluidity).15,18,78 However, in contrast to TAT, R8, and R9, PGua4 did not penetrate cells through direct plasma membrane translocation, even at higher concentrations. High accumulation of linear Arg-rich CPP on the cell surface has been proposed to lead to lipid packing, membrane potential perturbation, and transient pore formation, allowing direct translocation in the cells.79 We suggest that PGua4 is a scaffold possessing the right balance between flexibility and steric hindrance, which may limit the perturbation of the plasma membrane, thus explaining the incapacity of PGua4 to penetrate via direct translocation, even at high concentrations (which may also explain its low cytotoxicity).30

As reported for some Arg-rich CPPs (R8, R12, and TAT),18,42,80 PGua4 stimulates actin rearrangement and macropinocytosis. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), such as syndecans, are long-known interactors/receptors for arginine-rich CPP-mediated macropinocytosis.41,42,81,82 Since proteoglycans are necessary for PGua4 internalization,30 they can logically play a role in the macropinocytosis induced by PGua4. Interestingly, syndecan-4 has also been identified as the membrane-associated receptor for the uptake of R8 via clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME).77 The roles of HSPG in macropinocytosis and CME can explain the uptake of PGua4 by both pathways. Other interactions with arginine-rich CPPs were shown to be involved in macropinocytosis, including neuropilin-1, CXCR4, and possibly lanthionine synthase component C-like protein 1.83−85 Further studies are thus needed to precisely identify PGua4 receptors promoting macropinocytosis. There is indeed growing interest in the macropinocytosis pathway as a strategy for intracellular drug delivery since it allows effective entrance of large macromolecules and nanoparticles.9,86

Following cellular uptake/internalization, the intracellular trafficking pathway mapped for PGua4 is identical to that reported for TAT and R8 (at low concentrations (1 μM)), which colocalized with both early (Rab5+) and late (Rab7+) endosomes after 30 min of internalization.56 Recently, an unconventional endocytic route fully independent of Rab5 and Rab7 but dependent on Rab14 has been reported to target cationic CPPs (including R9 and Tat, at high concentrations (40 μM)) to the nonacidic LAMP1-positive compartment.87 While we cannot exclude the role of Rab14 in the intracellular transport of PGua4, at the concentrations used in our study (5 μM), PGua4 was observed to traffic mainly through the classical endocytic pathway and to primarily remain trapped within it, a major limitation for many Arg-rich CPPs, including TAT, R8, and R9.15,17,56 Based on qualitative assessment (detection of fluorescence in the cytoplasm, which is a limiting method for the detection of low level of cytoplasmic delivery), the release of PGua4 from endosomes occurs at a concentration ≥ 10 μM, with the maximal cells showing cytosolic labeling at a concentration of 20 μM. However, the endosomal escape efficiency of PGua4 is poor, given that it shows predominant vesicular localization even at high concentrations. Although Arg-rich CPP endosomal escape remains poorly defined, a few mechanisms have been proposed that can also be applied to PGua4.5,18,88,89 Given that endosomal acidification is required for cytosolic delivery of PGua4 (inhibited with bafilomycin A1) and that endosomal membrane destabilization/perturbation was detected (with a Gal3 sensor) in the presence of PGua4, one possible mechanism is that the positively charged PGua4 interacts with negatively charged phospholipids enriched in the endosomal membrane and induces the formation of a membrane pore and endosomal leakage or induces membrane budding into small vesicles. Indeed, the effects of Arg-rich CPP on lipid mixing, membrane curvature, and leakage were shown to be greater at the acidic pH found in endosomes.88−90 Another possible mechanism is that the low endosomal pH favors the protonated state of PGua4, which would cause osmotic swelling of the endosome and eventually lead to its rupture. However, this latter mechanism, termed the “proton sponge” effect, is mainly known for peptides rich in histidine.91,92 Of note is the fact that endosomal membrane permeation by PGua4 accommodates the translocation of large cargos, such as IgGs (150 kDa), implying a very effective perturbation of the endosomal membrane. More recently, a novel membrane translocation mechanism, named vesicle budding and collapse (VBC), proposes that CPPs induce endosomal membrane curvature and budding of small vesicles, which subsequently collapse into amorphous lipid/peptide aggregates, thereby releasing their luminal contents into the cytosol.89,93 An advantage of this model is that it explains how CPPs deliver macromolecular cargoes (such as IgGs) in the cytoplasm without having to rupture or permeabilize the endosomal membrane. Based on this model, the fluorescence puncta observed in Figure 7 can represent collapsed vesicles/lipid-peptoid aggregates. Further studies will be directed to decipher the precise mechanism by which PGua4 induces endosomal escape to modify the original structure or to add motifs that will improve its cytosolic delivery.

PGua4 is able to deliver IgGs into the cytosol by noncovalent complexation by performing a simple premixing of PGua4 with this cargo in a test tube before addition to the cells. Based on qualitative assessment, the optimal mixing ratio for complex formation was 0.15 μM IgG:20 μM PGua4, and 24 h of incubation delivered IgG to the cytosol of 30% of the cells. We showed that complexation with PGua4 allows cellular uptake of IgGs via macropinocytosis and partial endosomal escape into the cytosol. However, complexation with linear arginine-rich R8 and R9 was unable to deliver IgGs into the cytosol, supporting that the conformational restricted CPPs, such as PGua4, show better endosomal escape efficiencies.89,90,94 Importantly, we also noted that the premixing step is critical for endosomal escape given that the simple coaddition (without complexation) of IgGs and PGua4 allowed the internalization of IgGs in endosomes but not their delivery to the cytosol. A quantitative assay should be performed in the future to determine the amount of IgG that is able to reach the cytoplasm using the complexation assay. Nevertheless, the assay performed with anti-nuclear pore complex IgGs indicated low endosomal escape efficacy and/or partial IgG degradation given that only a few cells showed nuclear membrane labeling. It suggests that only a fraction of IgGs delivered in the cytosol is functional and/or is in sufficient quantities to detect their target proteins on the nuclear membrane. Optimization will be required to enhance the functional cargo delivery by PGua4. Surprisingly, we also showed that the covalent coupling between PGua4 and IgGs allowed IgG internalization in endosomes but did not support IgG delivery into the cytosol. This result was unexpected given that most Arg-rich CPPs, such as Tat and oligo-Arg, have been shown to deliver their cargo when covalently linked to them.95−97 This suggests that either covalent binding altered the endosomal escape properties of PGua4, as previously reported for other CPPs, or that the ratio of IgGs-PGua4 was not optimal.98 Indeed, four PGua4 peptoids were covalently linked to each IgG, whereas many more PGua4 peptoids may be complexed to each IgG using the noncovalent complexation method. This noncovalent complexation strategy is usually based on the phenomenon that positively charged peptides can condense negatively charged molecules through electrostatic interactions to form stable complexes.99,100 Further studies will be required to better understand the physicochemical properties of the complexation of PGua4 with IgGs (electrostatic and/or hydrophobic interactions, stability of the complex, dissociation kinetics, and stability in biological environments), to determine whether other types of cargo (proteins, RNA, DNA, nanoparticles, etc.) can be delivered by PGua4, and to modify PGua4 in order to enhance endosomal escape efficacy and reduce the incubation times for optimal delivery of functional cargo.

Finally, in addition to its low cell toxicity,30 PGua4 showed remarkable resistance to proteolytic degradation. Unlike classic peptides, the peptoid nature of PGua4 (its side chain is appended to the amine nitrogen instead of the α-carbon) prevents recognition by proteases, allowing better metabolic stability, an essential characteristic for in vivo application.29,101

Conclusions

In conclusion, PGua4 is a promising CPP for the cytosolic delivery of IgGs. It presents several advantages, including lack of toxicity and sensitivity to serum as well as high proteolytic stability. Moreover, it induces macropinocytosis, allowing the delivery of large cargos in various cells, and it can form complexes with IgGs upon simple mixing without the need for genetic engineering or chemical cross-linking to couple them covalently. Although PGua4 still requires optimization for better endosomal escape and complexation with different cargos, we believe it can become a useful tool for protein delivery, which is currently of high interest for therapeutic applications.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Michel Grandbois (University of Sherbrooke, Canada) for kindly providing the LifeAct-RFP plasmid and Caco-2 cells and to Dr. Richard Leduc, Dr. Marie-Josée Boucher, and Dr. Alexandra Newton for providing different cell lines. We are also grateful to Alexandre Murza for constructive criticism of the results and the manuscript. We also thank the Plateforme de microscopie photonique and the Plateforme de cytométrie de l’Université de Sherbrooke. This paper is dedicated to the memory of our dear friend, colleague, and mentor, Dr. Eric Marsault, who died prematurely. He initiated and greatly contributed to this project.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AF594

Alexa Fluor 594

- CAV1

caveolin 1

- CHC

clathrin heavy chain

- CME

clathrin-mediated endocytosis

- CPP

cell-penetrating peptide

- CTB

cholera toxin subunit B

- CytD

cytochalasin D

- Dex70

Dextran 70

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FITC

fluorescein

- GAG

glycosaminoglycan

- Gal3

galectin-3

- GRT

guanidinium-rich transporters

- HSPG

heparan sulfate proteoglycan

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- NPC

nuclear pore complex proteins

- PI

propidium iodide

- R8

octa-arginine

- R9

nona-arginine

- Tf

transferrin

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.2c00783.

Materials and methods; statistical analysis of PGua4 uptake in different cell lines (Table S1); statistical analysis of PAm4 uptake in different cell lines (Table S2); validation of protein expression knockdown (Figure S1); cytochalasin D, which does not inhibit the clathrin-mediated endocytosis pathway (Figure S2); colocalization of FITC-PGua4 with RFP-Rab5 wild-type (Figure S3); serum, which does not affect the internalization and endosomal escape of PGua4 (Figure S4); high concentration of FITC-PGua4 (10 μM) internalized by macropinocytosis (Figure S5); PGua4 not affected by proteolytic degradation (Figure S6); increasing the amount of IgGs in the complex mixture with PGua4, which does not increase the cytoplasmic delivery (Figure S7); complex IgG:Pgua4 internalized by macropinocytosis (Figure S8); IgG complexation with PGua4 required for its cytoplasmic delivery (Figure S9); delivery of AlexaFluor594-IgG into HeLa cells by FITC-R8 or FITC-R9 (Figure S10) (PDF)

Author Contributions

A.L. planned and performed most of the experiments, collected and analyzed the data, made all the figures, and drafted the manuscript. E.M. and D.T.N. performed all CPP syntheses and revised the manuscript. U.F. performed all enzymatic stability assays. C.M. helped in some FACS experiments. P.-L.B. and C.L designed the study, provided intellectual feedback, participated in interpretation of data, and revised the manuscript. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by research funds from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to Eric Marsault. and P.-L.B. (#RGPIN-2022-04028) and to C.L. (#RGPIN-2020-06468). A.L. was supported by predoctoral fellowships from the FRQNT-funded PROTEO Network and Fond de Recherche du Québec (FRQS).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Yang N. J.; Hinner M. J. Getting Across the Cell Membrane: An Overview for Small Molecules, Peptides, and Proteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1266, 29–53. 10.1007/978-1-4939-2272-7_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oba M.; Demizu Y.. Cell-Penetrating Peptides: Design, Development and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hao M.; Zhang L.; Chen P. Membrane Internalization Mechanisms and Design Strategies of Arginine-Rich Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9038. 10.3390/ijms23169038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porosk L.; Langel Ü. Approaches for Evaluation of Novel CPP-Based Cargo Delivery Systems. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 1056467. 10.3389/fphar.2022.1056467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J.; Bi Y.; Zhang H.; Dong S.; Teng L.; Lee R. J.; Yang Z. Cell-Penetrating Peptides in Diagnosis and Treatment of Human Diseases: From Preclinical Research to Clinical Application. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 697. 10.3389/fphar.2020.00697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derakhshankhah H.; Jafari S. Cell Penetrating Peptides: A Concise Review with Emphasis on Biomedical Applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 108, 1090–1096. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.09.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desale K.; Kuche K.; Jain S. Cell-Penetrating Peptides (CPPs): An Overview of Applications for Improving the Potential of Nanotherapeutics. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 1153–1188. 10.1039/D0BM01755H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanzl E. G.; Trantow B. M.; Vargas J. R.; Wender P. A. Fifteen Years of Cell-Penetrating, Guanidinium-Rich Molecular Transporters: Basic Science, Research Tools, and Clinical Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2944–2954. 10.1021/ar4000554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arafiles J. V. V.; Hirose H.; Akishiba M.; Tsuji S.; Imanishi M.; Futaki S. Stimulating Macropinocytosis for Intracellular Nucleic Acid and Protein Delivery: A Combined Strategy with Membrane-Lytic Peptides To Facilitate Endosomal Escape. Bioconjugate Chem. 2020, 31, 547–553. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.0c00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Khan A. R.; Fu M.; Wang R.; Ji J.; Zhai G. Cell-Penetrating Peptide: A Means of Breaking through the Physiological Barriers of Different Tissues and Organs. J. Controlled Release 2019, 309, 106–124. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel A. D.; Pabo C. O. Cellular Uptake of the Tat Protein from Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Cell 1988, 55, 1189–1193. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivès E.; Brodin P.; Lebleu B. A Truncated HIV-1 Tat Protein Basic Domain Rapidly Translocates through the Plasma Membrane and Accumulates in the Cell Nucleus. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 16010–16017. 10.1074/jbc.272.25.16010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derossi D.; Joliot A. H.; Chassaing G.; Prochiantz A. The Third Helix of the Antennapedia Homeodomain Translocates through Biological Membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 10444–10450. 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)34080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futaki S. Oligoarginine Vectors for Intracellular Delivery: Design and Cellular-Uptake Mechanisms. Biopolymers 2006, 84, 241–249. 10.1002/bip.20421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeCher J. C.; Nowak S. J.; McMurry J. L. Breaking in and Busting out: Cell-Penetrating Peptides and the Endosomal Escape Problem. Biomol Concepts 2017, 8, 131–141. 10.1515/bmc-2017-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitz F.; Morris M. C.; Divita G. Twenty Years of Cell-Penetrating Peptides: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutics. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 157, 195–206. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madani F.; Abdo R.; Lindberg S.; Hirose H.; Futaki S.; Langel Ü.; Gräslund A. Modeling the Endosomal Escape of Cell-Penetrating Peptides Using a Transmembrane PH Gradient. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2013, 1828, 1198–1204. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruseska I.; Zimmer A. Internalization Mechanisms of Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2020, 11, 101–123. 10.3762/bjnano.11.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei D.; Buyanova M. Overcoming Endosomal Entrapment in Drug Delivery. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30, 273–283. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wender P. A.; Mitchell D. J.; Pattabiraman K.; Pelkey E. T.; Steinman L.; Rothbard J. B. The Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Molecules That Enable or Enhance Cellular Uptake: Peptoid Molecular Transporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000, 97, 13003–13008. 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi T.; Kosuge M.; Tadokoro A.; Sugiura Y.; Nishi M.; Kawata M.; Sakai N.; Matile S.; Futaki S. Direct and Rapid Cytosolic Delivery Using Cell-Penetrating Peptides Mediated by Pyrenebutyrate. ACS Chem. Biol. 2006, 1, 299–303. 10.1021/cb600127m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futaki S.; Suzuki T.; Ohashi W.; Yagami T.; Tanaka S.; Ueda K.; Sugiura Y. Arginine-Rich Peptides. An Abundant Source of Membrane-Permeable Peptides Having Potential as Carriers for Intracellular Protein Delivery. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 5836–5840. 10.1074/jbc.M007540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright L.; Rothbard J.; Wender P. Guanidinium Rich Peptide Transporters and Drug Delivery. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2003, 4, 105–124. 10.2174/1389203033487252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas J. R.; Stanzl E. G.; Teng N. N. H.; Wender P. A. Cell-Penetrating, Guanidinium-Rich Molecular Transporters for Overcoming Efflux-Mediated Multidrug Resistance. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2014, 11, 2553–2565. 10.1021/mp500161z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbard J. B.; Jessop T. C.; Lewis R. S.; Murray B. A.; Wender P. A. Role of Membrane Potential and Hydrogen Bonding in the Mechanism of Translocation of Guanidinium-Rich Peptides into Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 9506–9507. 10.1021/ja0482536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lättig-Tünnemann G.; Prinz M.; Hoffmann D.; Behlke J.; Palm-Apergi C.; Morano I.; Herce H. D.; Cardoso M. C. Backbone Rigidity and Static Presentation of Guanidinium Groups Increases Cellular Uptake of Arginine-Rich Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 453. 10.1038/ncomms1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwochert J.; Turner R.; Thang M.; Berkeley R. F.; Ponkey A. R.; Rodriguez K. M.; Leung S. S. F.; Khunte B.; Goetz G.; Limberakis C.; Kalgutkar A. S.; Eng H.; Shapiro M. J.; Mathiowetz A. M.; Price D. A.; Liras S.; Jacobson M. P.; Lokey R. S. Peptide to Peptoid Substitutions Increase Cell Permeability in Cyclic Hexapeptides. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 2928–2931. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckermann R. N.; Kodadek T. Peptoids as Potential Therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2009, 11, 299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R. J.; Kania R. S.; Zuckermann R. N.; Huebner V. D.; Jewell D. A.; Banville S.; Ng S.; Wang L.; Rosenberg S.; Marlowe C. K. Peptoids: A Modular Approach to Drug Discovery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992, 89, 9367–9371. 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marouseau E.; Neckebroeck A.; Larkin H.; Le Roux A.; Volkov L.; Lavoie C. L.; Marsault É. Modular Sub-Monomeric Cell-Penetrating Guanidine-Rich Peptoids – Synthesis, Assembly and Biological Evaluation. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 6059–6063. 10.1039/C6RA27898A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teo S. L. Y.; Rennick J. J.; Yuen D.; Al-Wassiti H.; Johnston A. P. R.; Pouton C. W. Unravelling Cytosolic Delivery of Cell Penetrating Peptides with a Quantitative Endosomal Escape Assay. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3721. 10.1038/s41467-021-23997-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnapen D. J.-F.; Chinnapen H.; Saslowsky D.; Lencer W. I. Rafting with Cholera Toxin: Endocytosis and Trafficking from Plasma Membrane to ER. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007, 266, 129–137. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayle K. M.; Le A. M.; Kamei D. T. The Intracellular Trafficking Pathway of Transferrin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1820, 264–281. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praefcke G. J. K.; McMahon H. T. The Dynamin Superfamily: Universal Membrane Tubulation and Fission Molecules?. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2004, 5, 133–147. 10.1038/nrm1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh P.; McIntosh D. P.; Schnitzer J. E. Dynamin at the Neck of Caveolae Mediates Their Budding to Form Transport Vesicles by GTP-Driven Fission from the Plasma Membrane of Endothelium. J Cell Biol 1998, 141, 101–114. 10.1083/jcb.141.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X. P.; Mintern J. D.; Gleeson P. A. Macropinocytosis in Different Cell Types: Similarities and Differences. Membranes 2020, 10, 177. 10.3390/membranes10080177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto L. M.; Roth R.; Heuser J. E.; Schmid S. L. Actin Assembly Plays a Variable, but Not Obligatory Role in Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis in Mammalian Cells. Traffic 2000, 1, 161–171. 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Wan T.; Wan M.; Liu B.; Cheng R.; Zhang R. The Effect of the Size of Fluorescent Dextran on Its Endocytic Pathway. Cell Biol. Int. 2015, 39, 531–539. 10.1002/cbin.10424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay R.; Macropinocytosis R. Biology and Mechanisms. Cells Dev. 2021, 168, 203713 10.1016/j.cdev.2021.203713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J. P.; Gleeson P. A. Macropinocytosis: An Endocytic Pathway for Internalising Large Gulps. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2011, 89, 836–843. 10.1038/icb.2011.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan I. M.; Wadia J. S.; Dowdy S. F. Cationic TAT Peptide Transduction Domain Enters Cells by Macropinocytosis. J. Controlled Release 2005, 102, 247–253. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Niwa M.; Takeuchi T.; Sonomura K.; Kawabata N.; Koike Y.; Takehashi M.; Tanaka S.; Ueda K.; Simpson J. C.; Jones A. T.; Sugiura Y.; Futaki S. Cellular Uptake of Arginine-Rich Peptides: Roles for Macropinocytosis and Actin Rearrangement. Mol. Ther. 2004, 10, 1011–1022. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canton J. Macropinocytosis: New Insights Into Its Underappreciated Role in Innate Immune Cell Surveillance. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2286. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S.; Zhang Y.; Ding T.; Ji N.; Zhao H. The Dual Role of Macropinocytosis in Cancers: Promoting Growth and Inducing Methuosis to Participate in Anticancer Therapies as Targets. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10, 570108 10.3389/fonc.2020.570108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl J.; Crevenna A. H.; Kessenbrock K.; Yu J. H.; Neukirchen D.; Bista M.; Bradke F.; Jenne D.; Holak T. A.; Werb Z.; Sixt M.; Wedlich-Soldner R. Lifeact: A Versatile Marker to Visualize F-Actin. Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 605–607. 10.1038/nmeth.1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen E.; Severin F.; Backer J. M.; Hyman A. A.; Zerial M. Rab5 Regulates Motility of Early Endosomes on Microtubules. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999, 1, 376–382. 10.1038/14075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovic M.; Sharma M.; Rahajeng J.; Caplan S. The Early Endosome: A Busy Sorting Station for Proteins at the Crossroads. Histol. Histopathol. 2010, 25, 99–112. 10.14670/HH-25.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra F.; Bucci C. Multiple Roles of the Small GTPase Rab7. Cell 2016, 5, 34. 10.3390/cells5030034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welz T.; Wellbourne-Wood J.; Kerkhoff E. Orchestration of Cell Surface Proteins by Rab11. Trends in Cell Biology 2014, 24, 407–415. 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld J. L.; Moore R. H.; Zimmer K. P.; Alpizar-Foster E.; Dai W.; Zarka M. N.; Knoll B. J. Lysosome Proteins Are Redistributed during Expression of a GTP-Hydrolysis-Defective Rab5a. J. Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 4499–4508. 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchardt F.; Fotin-Mleczek M.; Schwarz H.; Fischer R.; Brock R. A Comprehensive Model for the Cellular Uptake of Cationic Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Traffic 2007, 8, 848–866. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama K.; Nakase I.; Michiue H.; Takeuchi T.; Tomizawa K.; Matsui H.; Futaki S. Enhanced Intracellular Delivery Using Arginine-Rich Peptides by the Addition of Penetration Accelerating Sequences (Pas). J. Controlled Release 2009, 138, 128–133. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto K.; Akishiba M.; Iwata T.; Arafiles J. V. V.; Imanishi M.; Futaki S. Use of Homoarginine to Obtain Attenuated Cationic Membrane Lytic Peptides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 40, 127925 10.1016/j.bmcl.2021.127925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J.; Najjar K.; Erazo-Oliveras A.; Kondow-McConaghy H. M.; Brock D. J.; Graham K.; Hager E. C.; Marschall A. L. J.; Dübel S.; Juliano R. L.; Pellois J.-P. Cytosolic Delivery of Macromolecules in Live Human Cells Using the Combined Endosomal Escape Activities of a Small Molecule and Cell Penetrating Peptides. ACS Chem. Biol. 2019, 14, 2641–2651. 10.1021/acschembio.9b00585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosuge M.; Takeuchi T.; Nakase I.; Jones A. T.; Futaki S. Cellular Internalization and Distribution of Arginine-Rich Peptides as a Function of Extracellular Peptide Concentration, Serum, and Plasma Membrane Associated Proteoglycans. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008, 19, 656–664. 10.1021/bc700289w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum J. S.; LaRochelle J. R.; Smith B. A.; Balkin D. M.; Holub J. M.; Schepartz A. Arginine Topology Controls Escape of Minimally Cationic Proteins from Early Endosomes to the Cytoplasm. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 819–830. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer N.; Schober D.; Prchla E.; Murphy R. F.; Blaas D.; Fuchs R. Effect of Bafilomycin A1 and Nocodazole on Endocytic Transport in HeLa Cells: Implications for Viral Uncoating and Infection. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 9645–9655. 10.1128/JVI.72.12.9645-9655.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clague M. J.; Urbé S.; Aniento F.; Gruenberg J. Vacuolar ATPase Activity Is Required for Endosomal Carrier Vesicle Formation. J Biol Chem 1994, 269, 21–24. 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)42302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier O.; Marvin S. A.; Wodrich H.; Campbell E. M.; Wiethoff C. M. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Adenovirus Membrane Rupture and Endosomal Escape. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 10821–10828. 10.1128/JVI.01428-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock D. J.; Kondow-McConaghy H. M.; Hager E. C.; Pellois J.-P. Endosomal Escape and Cytosolic Penetration of Macromolecules Mediated by Synthetic Delivery Agents. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30, 293–304. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-S.; Lee Y.; Shin M. H.; Lim H.-S. Cell-Penetrating, Amphipathic Cyclic Peptoids as Molecular Transporters for Cargo Delivery. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 6800–6803. 10.1039/d1cc02848k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K.; Ejaz W.; Dutta K.; Thayumanavan S. Antibody Delivery for Intracellular Targets: Emergent Therapeutic Potential. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30, 1028–1041. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.9b00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G.; Luo Y.; Wang H.; Wang Y.; Liu B.; Wei J. Therapeutic Bispecific Antibodies against Intracellular Tumor Antigens. Cancer Lett. 2022, 538, 215699 10.1016/j.canlet.2022.215699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda A.; Tahara S.; Hirose H.; Takeuchi T.; Nakase I.; Ono A.; Takehashi M.; Tanaka S.; Futaki S. Oligoarginine-Bearing Tandem Repeat Penetration-Accelerating Sequence Delivers Protein to Cytosol via Caveolae-Mediated Endocytosis. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 1849–1859. 10.1021/acs.biomac.8b01299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda A.; Futaki S. Protein Delivery to Cytosol by Cell-Penetrating Peptide Bearing Tandem Repeat Penetration-Accelerating Sequence. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2383, 265–273. 10.1007/978-1-0716-1752-6_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R.; Brattain M. G. The Maximal Size of Protein to Diffuse through the Nuclear Pore Is Larger than 60kDa. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 3164–3170. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorko M.; Langel Ü. Cell-Penetrating Peptides: Mechanism and Kinetics of Cargo Delivery. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2005, 57, 529–545. 10.1016/j.addr.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]