Abstract

EGL-15 is a fibroblast growth factor receptor in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Components that mediate EGL-15 signaling have been identified via mutations that confer a Clear (Clr) phenotype, indicative of hyperactivity of this pathway, or a suppressor-of-Clr (Soc) phenotype, indicative of reduced pathway activity. We have isolated a gain-of-function allele of let-60 ras that confers a Clr phenotype and implicated both let-60 ras and components of a mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in EGL-15 signaling by their Soc phenotype. Epistasis analysis indicates that the gene soc-1 functions in EGL-15 signaling by acting either upstream of or independently of LET-60 RAS. soc-1 encodes a multisubstrate adaptor protein with an amino-terminal pleckstrin homology domain that is structurally similar to the DOS protein in Drosophila and mammalian GAB1. DOS is known to act with the cytoplasmic tyrosine phosphatase Corkscrew (CSW) in signaling pathways in Drosophila. Similarly, the C. elegans CSW ortholog PTP-2 was found to be involved in EGL-15 signaling. Structure-function analysis of SOC-1 and phenotypic analysis of single and double mutants are consistent with a model in which SOC-1 and PTP-2 act together in a pathway downstream of EGL-15 and the Src homology domain 2 (SH2)/SH3-adaptor protein SEM-5/GRB2 contributes to SOC-1-independent activities of EGL-15.

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) play critical roles in translating cues gathered from the extracellular environment into biological responses such as cellular differentiation, proliferation, and migration events. RTKs such as the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptors define a family of single-pass transmembrane proteins with an intracellular tyrosine kinase domain (51). Binding of growth factor to the extracellular portions of these receptors promotes receptor dimerization and activation of the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain (43). Receptor activation leads to receptor autophosphorylation as well as phosphorylation of cytoplasmic signaling proteins. Specific phosphotyrosine sites on the receptor can serve to propagate signaling by recruiting Src homology domain 2 (SH2) and PTB domain-containing signaling proteins directly to the activated receptor (37, 38). For example, many RTKs can signal to the RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade via direct recruitment of the SH2/SH3 domain-containing adaptor protein GRB2 in complex with SOS, the guanine nucleotide exchange factor for RAS (31). EGF and PDGF RTKs can utilize direct recruitment of the GRB2/SOS complex to achieve RAS activation. This canonical pathway is well-conserved in Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila, and mammalian systems (37).

There is compelling evidence that the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway plays an important role in signaling via FGF receptors (FGFRs) as well (32). However, unlike the EGF and PDGF receptors, FGFRs do not appear to recruit GRB2/SOS directly. Instead, mammalian FGFR-1 makes use of the multisubstrate adaptor (MSA) FRS2/SNT1 to link receptor activation to GRB2/SOS recruitment and the RAS/MAPK cascade (25, 53). FRS2 consists of an N-terminal myristylation sequence followed by a PTB domain and an extended C-terminal tail with a number of tyrosine motifs. Upon FGFR activation, FRS2 becomes highly tyrosine phosphorylated, creating docking sites for the SH2 domain of GRB2 as well as other SH2 domain-containing signaling components.

FRS2 typifies one class of MSA proteins. A second, structurally distinct class of MSAs includes mammalian GAB1 and Drosophila DOS (38). This second class of MSAs differs from FRS2 in both structure and function. GAB1 and DOS consist of an N-terminal pleckstrin homology (PH) domain followed by a C-terminal tail that contains a number of tyrosine and polyproline motifs. Unlike FRS2, which appears to act specifically in FGF and nerve growth factor RTK signaling, GAB1 and DOS have been implicated in a number of RTK signaling pathways (18, 20, 21, 34, 41, 54). The precise molecular mechanisms by which the GAB1/DOS-type MSAs function to mediate signaling remain unclear. In Drosophila, DOS function is intimately linked to the cytoplasmic tyrosine phosphatase Corkscrew (CSW) (3, 18, 19). Similarly, GAB1 can associate with the mammalian ortholog of CSW, SHP2, and may represent a similar signaling module in mammalian systems (20, 45).

In C. elegans, egl-15 encodes the sole FGFR and plays a critical role in multiple aspects of development (11). Modulating the strength of signaling through EGL-15 can have profound phenotypic effects. Hyperactive EGL-15 signaling results in a distinctive Clear (Clr) phenotype. This Clr phenotype can be observed in transgenic animals bearing a constitutively active version of EGL-15 or in animals that have lost the CLR-1 receptor tyrosine phosphatase that normally attenuates EGL-15 signaling (23). Animals that have completely lost egl-15 function arrest early in larval development, demonstrating an essential role for this receptor. Less severe reduction of egl-15 function can confer multiple developmental defects. These defects include a Scrawny (Scr) body morphology, an egg-laying-defective phenotype, and suppression of the Clr phenotype of clr-1 mutants. We have called this last phenotype Soc for suppression of Clr and have used the Soc phenotype as an indication of reduced levels of EGL-15 signaling (11).

Genetic analysis has begun to identify components that function downstream of EGL-15 in its various roles. Some of these roles, such as sex myoblast migration guidance and the essential function of EGL-15, appear to be functionally distinct and may involve different downstream signaling pathways. Genetic screens for suppressors of clr-1 (soc genes) have identified the most comprehensive set of downstream signaling components for EGL-15. These suppressor mutations include multiple alleles of four genes (egl-15, sem-5, soc-1, and soc-2/sur-8) as well as a single allele of let-341/sos-1 (11). Soc mutations in sem-5, the GRB2 ortholog in C. elegans (10); soc-2/sur-8, encoding a leucine-rich repeat protein that binds to LET-60 RAS (44, 46); and let-341/sos-1 (8) implicate the RAS/MAPK cascade in mediating this function of EGL-15 signaling. LET-60 RAS function has been implicated in other processes mediated by EGL-15 (9, 11, 49). Here we present direct evidence for the involvement of LET-60 RAS and members of the MAPK cascade in the Clr/Soc aspect of EGL-15 signaling. In addition, we have cloned soc-1 and present evidence that it functions in conjunction with the C. elegans SHP2 homolog, PTP-2 (13), to mediate a portion of the EGL-15 signal transduction cascade.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of let-60(ay75gf)

A semiclonal screen for enhancers of the Clr phenotype of clr-1(e1745ts) was performed at 15°C, the permissive temperature for e1745ts. All manipulations were performed at 15°C. clr-1(e1745ts) hermaphrodites were mutagenized with ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) as described previously (6). F1 progeny were picked to individual plates at five per plate, the F2 progeny were screened for Clr animals, and the mutations responsible for the Clr phenotype were recovered from F2 siblings of Clr animals. From animals representing approximately 6,000 mutagenized haploid genomes, two mutations that caused a recessive Clr phenotype at 15°C were identified. Besides the ay75 mutant, the other mutant isolated bore a second mutation in clr-1 that resulted in a nonconditional Clr phenotype (ay76). Although ay75 was obtained in a clr-1(e1745ts) background, it confers a Clr phenotype even in a clr-1(+) background. All subsequent characterization has been performed in a clr-1(+) background.

ay75 was backcrossed four times and mapped based on its recessive Clr phenotype at 15°C. Sequence-tagged site mapping (55) showed tight linkage to the sP4 polymorphism on linkage group IV (among ay75/ay75 homozygotes segregated from ay75/sP4 hermaphrodites, 0 of 90 contained the sP4 marker). Subsequent multifactor mapping showed that ay75 mapped between lin-3 and unc-22 and was inseparable from dpy-20 (data available from ACEDB [http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/C_elegans/webace_front_end.shtml]).

Isolation of let-60(ay75 ay100)

Suppressors of ay75 were isolated based on its temperature-sensitive semidominant fertility defect. let-60(ay75) + unc-22(e66)/+ dpy-20(e1362) + hermaphrodites were mutagenized with EMS at 15°C, and the healthy F1 progeny (non-Dpy, non-Clr, non-Twi) were picked to a single plate and transferred to 25°C for 1 day. Healthy young adults were picked at one per plate; after an additional 2 days at 25°C, plates with large broods were identified. The broods from 1,678 F1 animals were screened, and two mutants (ay100 and ay101) were isolated, both of which segregated rod-like larval-lethal progeny characteristic of loss-of-function let-60 alleles. ay75 ay100 was backcrossed by mating N2 males into non-Dpy progeny [ay75 ay100 unc-22(e66)/dpy-20(e1362)]. The resulting males were crossed into dpy-20(e1362) hermaphrodites. Non-Dpy cross-progeny that segregated rod-like larval-lethal progeny were selected as the twice-backcrossed strain, and the process was repeated. The behavior of ay100 during the backcrossing protocol was consistent with it being an intragenic suppressor. ay101 was not characterized further.

Brood sizes were measured by cloning L4 hermaphrodites and transferring each adult to a fresh plate daily. Progeny were counted immediately after each transfer.

Characterization of let-60(gf) phenotypes.

In contrast to the Clr phenotype of clr-1 mutants, which can be observed at any postembryonic stage, let-60(ga89ts) and let-60(ay75ts) mutants display a late-onset Clr phenotype, becoming observably Clr only as adults. The let-60(ay75) mutant was not used for epistasis studies due to its low brood size. Instead, the let-60(ga89) mutant was used to assess the epistatic relationship between let-60 ras and the soc genes. Double mutant combinations between let-60(ga89) and the soc genes were assayed by shifting L4 hermaphrodites to 25°C and scoring for the Clr or Soc phenotype approximately 36 h later. Due to a severe egg-laying-defective phenotype, the Clr phenotype of let-60(ga89); sem-5(n1779) was assessed in gonad-ablated animals; gonads in L1 animals were ablated, and the animals were shifted to 25°C. The strain was severely developmentally delayed, and the Clr phenotype was apparent after 5 days at 25°C.

let-60(ay75) was characterized at 15°C for its ability to confer a Clr or Muv phenotype in the following manner. Non-Dpy L4 hermaphrodite progeny from let-60(ay75)/dpy-20(e1362) animals were cloned to individual plates, and their adult phenotype was assayed after 2 days at 15°C. Genotypes of the progeny were inferred by the spectrum of phenotypes exhibited in their resulting brood: animals whose broods included approximately 25% Dpy animals were inferred to be let-60(ay75)/dpy-20(e1362); animals whose broods lacked Dpy animals were inferred to be let-60(ay75)/let-60(ay75).

Phenotypic characterization of ay75/+ at 25oC was performed as follows. Gravid unc-24(e138) let-60(ay75) unc-22(e66)/dpy-20(e1362) adult hermaphrodites were allowed to lay eggs for 1 h at 15°C and transferred to 25°C for approximately 48 h until the progeny reached the L4 stage. Non-Dpy non-Unc non-Twi hermaphrodites [unc-24(e138) let-60(ay75) unc-22(e66)/dpy-20(e1362)] were collected at 10 per plate, and their phenotypes were scored at approximately 48 h post-L4 stage.

let-60(ay75 ay100) was characterized at 25°C as follows. Gravid let-60(ay75 ay100) unc-22(e66)/dpy-20(e1362) adult hermaphrodites were grown at 25°C and allowed to lay eggs for 1 h. The progeny were grown at 25°C for an additional 3 days, and their phenotypes were scored. Non-Dpy non-Twi hermaphrodites were inferred to be let-60(ay75 ay100) unc-22(e66)/dpy-20(e1362) heterozygotes. Rod-like larval-lethal animals were inferred to be let-60(ay75 ay100) unc-22(e66) homozygotes.

Synchronized let-60(n1046gf) progeny were obtained by transferring gravid let-60(n1046gf) hermaphrodites once a day to fresh plates. Phenotypes displayed by the progeny were scored after 3 days at 25°C or after 7 days at 15°C.

Cloning of soc-1

The soc-1 map position was refined by mapping with respect to restriction fragment length polymorphisms, which placed soc-1 to the left of the RW#L63 polymorphism (L. DeLong and M. J. Stern, personal communication).

soc-1-rescuing activity was assayed by injecting gravid clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1(n1789) hermaphrodites with 40 ng of tester DNA per μl and 50 to 100 ng of pRF4 per μl as a cotransformation marker. Injected animals were allowed to lay eggs at the permissive temperature (15°C). Transformed F1 Rol progeny were either scored for rescue of the Soc phenotype by shifting animals at the L4 stage to the nonpermissive temperature (25°C) for 4 to 16 h or transferred semiclonally to new plates to identify stably transmitting lines. A minimum of 10 Rol animals from each line were tested for rescue of the Soc phenotype as described for F1 transformants. soc-1-rescued animals are Clr at 25°C; nonrescued animals retain the Soc phenotype at 25°C.

Germ line transformation of ptp-2

Due to the recessive sterility of ptp-2(op194), ptp-2-rescuing activity was assayed by injecting tester DNA at 20 ng per μl with 50 to 100 ng of pRF4 DNA per μl into gravid clr-1(e1745ts) ptp-2(op194)/mIn1 hermaphrodites, establishing transformed lines, and scoring the clr-1(e1745ts) ptp-2(op194) homozygous progeny for a Clr or Soc phenotype. mIn1 is an inversion on chromosome II that balances clr-1 and ptp-2. mIn1 is homozygous viable and contains a mutation in dpy-10 that confers a Dpy phenotype in mIn1 homozygotes (M. Edgley, personal communication). Injected animals were allowed to lay eggs at 15°C; transformed F1 Rol progeny were transferred to 25°C. As for soc-1 rescue, ptp-2-rescued animals are Clr at 25°C; nonrescued animals retain the Soc phenotype at 25°C. Approximately one-third of the non-Dpy transformed progeny are of the genotype clr-1(e1745ts) ptp-2(op194) and are relevant to assay for rescuing activity of the transgene; the other non-Dpy progeny are heterozygous for ptp-2(op194) and non-Clr at all temperatures regardless of the transgene. Heterozygotes were identified by segregating 1/4 Dpy mIn1 progeny. Stably transformed lines were isolated from these transformed heterozygotes and scored as described for F1 transformants. A wild-type genomic 5.3-kb PstI-XbaI fragment was isolated from the cosmid F59G1 that contained the region of overlap from the ptp-2-rescuing cosmids (13). This construct (NH#772) confers robust rescue of the Soc phenotype but very weak rescue of the fertility defect of ptp-2(op194). Rescue of the fertility defect was not assayed in the mutant constructs.

soc-1 cDNA isolation and allele sequencing.

A soc-1 cDNA was isolated using reverse transcription-PCR and 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends. Primers were designed based on the exon-intron structure of the gene F43F1.2 predicted by the program GENEFINDER. These were used to amplify a soc-1 cDNA from a mixed-stage C. elegans cDNA library. A 1,350-bp cDNA with an exon-intron structure similar, although not identical, to that of F43F1.2 (GenBank accession no. AF419335) was isolated. BLAST searches of nonredundant genomic DNA databases at the National Center for Biotechnology Information using the soc-1 cDNA sequence identified significant homology only to the PH domain of GAB1.

soc-1 allele lesions were identified by sequencing two or more independent PCR products amplified from either genomic DNA or single-worm PCRs from individual clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1 mutant strains. The entire open reading frame including exon-intron boundaries was sequenced for each allele, and mutational lesions were confirmed in independent PCR products.

soc-1 and ptp-2 mutant constructs.

Tyrosine-to-phenylalanine changes in SOC-1 were introduced into a soc-1 cDNA (NH#693) using the Transformer site-directed mutagenesis kit (Clontech). To facilitate testing of these constructs in the germ line transformation rescue assay, restriction sites were introduced into both the soc-1 cDNA and genomic rescuing constructs: an AgeI restriction site was introduced just upstream of the endogenous stop codon, and a NotI site was introduced just downstream of the stop codon. The AgeI site was positioned to allow GFP-coding sequences from pD95.67 (kindly provided by A. Fire, J. Ahnn, G. Seydoux, and S. Xu) to be added in frame to any modified construct. A C-terminal portion of the cDNA containing these site-directed mutations was cloned into the soc-1 genomic rescuing construct using an endogenous SphI site just downstream of the PH domain and the engineered AgeI restriction site.

The PTP-2 fragment fused to SOC-1(Y408F) contained the entire C-terminal portion of PTP-2 from alanine 123 just upstream of the C-terminal SH2 domain to the C terminus of PTP-2. A PCR product amplified from a genomic ptp-2 construct was inserted in frame between the AgeI and NotI restriction sites of the Y408F derivative of the SOC-1-rescuing construct described above.

PCR was used to generate the C-terminal truncations in SOC-1 by cloning into the endogenous SphI site and the inserted AgeI site. The truncation primers used (the AgeI site is in boldface) were as follows: CTD1, 5′-GGT TCA CCG GTT CGA CGA CTC GGC TGC ATG CGA GC-3′; CTD2, 5′-GGT TGA CCG GTC GTC TTC AGT CCG TCG GCT TG-3′; and CTD3, 5′-GGT TAA CCG GTC CGA TTG TTG GTA GTT CGA AGT TCG-3′. GFP-coding sequences were appended to the C terminus as described above.

Overlap PCR with mutagenic primers was used to introduce specific mutations in the essential arginine residue of each SH2 domain and the essential catalytic cysteine residue of the phosphatase domain of PTP-2 based on sequence comparisons with SHP2 (35). Mutagenic primers include (mutant codons are underlined) N-SH2 (R36E) (5′-GGA GAT TTT CTT CTT GAA TAC AGC GAA TCA AAT CCG-3′), C-SH2 (R159E) (5′-T TAC GAG AGC TCC TGG TAT GTG TTG ACT TGC TTC TAG AAG ATA CGT TCC ATT CTT TTC-3′), and PTP (C518S) (5′-C AAG TAC GGT ACC TGT TCT ACC AAT TCC AGC ACT AGA ATG AAC AAC GAT CGG-3′). Mutagenized products were reintroduced into the ptp-2 genomic rescuing construct NH#772.

All constructs were sequenced to confirm the presence of the desired mutation(s).

Constructs with GFP tags were also injected without the GFP. No difference in rescue efficiency was detected between GFP-tagged and untagged versions of the same soc-1 construct. Using fluorescence microscopy, SOC-1::GFP was visualized in early larval stages, the L4 vulva, cells surrounding the rectum, and cells in the head and tail. A more detailed analysis of soc-1 expression will be reported elsewhere.

sem-5 noncomplementation screen.

Null alleles of sem-5 were isolated based on two known characteristics: (i) noncomplementation of the Soc phenotype of sem-5(n1779) and (ii) the rod-like larval-lethal phenotype of strong alleles of sem-5 (10). clr-1(e1745ts); sem-5(n1779)/0 males were mated into EMS-mutagenized clr-1(e1745ts); lon-2(e678) hermaphrodites at 15°C. F1 progeny were transferred to 25°C to select for Soc cross-progeny; those which segregated rod-like larval lethals were characterized further. Two new mutations, ay73 and ay74, were isolated from animals representing approximately 12,000 mutagenized genomes. ay53 was isolated from a similar screen that did not include the lon-2(e678) marker, representing approximately 8,000 additional mutagenized genomes. Strains homozygous for ay53 could be maintained, while those with either ay73 or ay74 were maintained as balanced heterozygotes using the szT1[lon-2(e678)] balancer. Sequence determination revealed that ay53 corresponds to a molecular lesion that is identical to that found in the n1619 allele (P49L), ay73 corresponds to a nonsense mutation at Q10, and ay74 corresponds to a mutation in the SH2 domain (R87Q). Both ay73 and ay74 are partially penetrant rod-like larval-lethal mutations; the surviving homozygotes are extremely Scr and have no live self-progeny. ay73 is used as a sem-5 null allele due to its strong phenotype and its molecular lesion. ay74 displays a more penetrant rod-like larval-lethal phenotype, possibly due to dominant negative characteristics interfering with the maternal contribution of sem-5.

RESULTS

let-60 ras is critical for EGL-15 signaling.

In a screen for additional Clr mutants (see Materials and Methods), a single mutation, ay75, that was not an allele of clr-1 was isolated. The original characterization of this mutant was performed at 15°C, where ay75 confers a recessive late-onset Clr phenotype (Fig. 1D and 2A). On the basis of its recessive Clr phenotype at 15°C, ay75 was mapped by standard sequence-tagged site and multifactor mapping to a region of linkage group IV which contains the let-60 ras gene. Gain-of-function mutations in let-60 ras can confer a spectrum of phenotypes similar to those displayed by ay75 mutants (see below), leading us to test whether ay75 was associated with a lesion in the let-60 ras gene. Sequence analysis of the let-60 ras gene in ay75/ay75 homozygotes revealed a G178-to-A transition which results in a G60R alteration, demonstrating that ay75 is an allele of let-60.

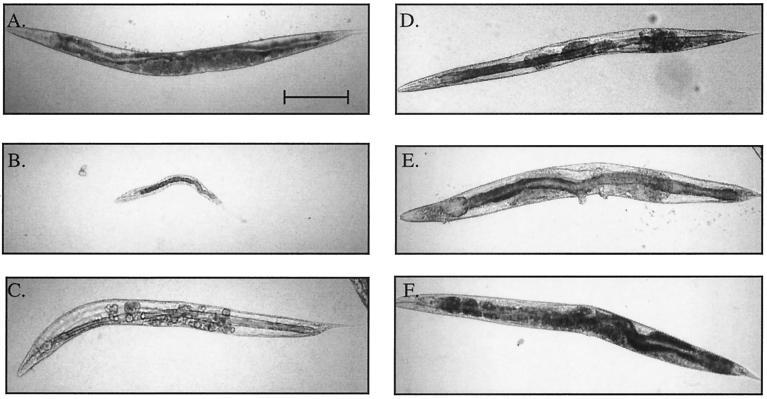

FIG. 1.

let-60(ay75gf) confers a Clr phenotype. (A) Wild type. (B) clr-1(n1992) null mutant, which displays a severe Clr phenotype. (C) clr-1(e1745ts) animal shifted from 15 to 25°C at mid-L4; these animals develop a dramatic Clr phenotype within a normal body shape. (D) let-60(ay75gf) homozygous animals raised at 15°C display a Clr phenotype similar to that of the clr-1(e1745ts) animal shown in panel C. (E) let-60(ay75)/+ heterozygous animals raised at 25°C display a dominant Clr phenotype. This animal also displays a protruding excretory pore and vulva. (F) let-60(ay75 ay100)/+ heterozygous animals raised at 25°C are non-Clr, demonstrating the cis-dominant effect of the intragenic suppressor, ay75 ay100. Bar, 200 μm.

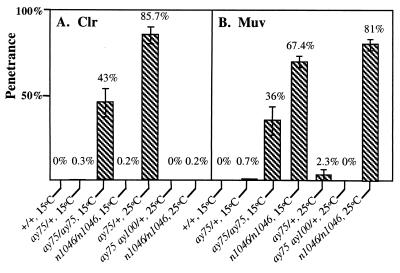

Several lines of evidence suggest that the Clr phenotype of let-60(ay75) is due to hyperactivation of LET-60 RAS activity. First, the lesion associated with ay75, G60R, enhances transforming mutations in mammalian RAS (28). Second, in addition to the Clr phenotype, ay75 mutants display pleiotropies characteristic of other let-60 ras gain-of-function alleles (4, 15, 16). ay75 mutants exhibit a partially penetrant Multivulva (Muv) phenotype (Fig. 2B) and a weakly penetrant protruding excretory pore phenotype (data not shown), both hallmarks of gain-of-function RAS mutations in C. elegans [Fig. 2B, let-60(n1046)]. Third, ay75/+ heterozygotes display dominant phenotypes, consistent with the hypothesis that this lesion in let-60 results in gain-of-function features. In contrast to the recessive Clr phenotype of ay75 at 15°C, ay75/+ heterozygotes raised at 25°C display a highly penetrant dominant Clr phenotype (Fig. 1E and 2A). In addition to the dominant Clr phenotype, ay75/+ heterozygotes also have dramatic fertility defects when raised at temperatures above 15°C (Table 1). Fourth, an intragenic suppressor (ay75 ay100) of the dominant fertility defect of ay75 abolishes the dominant Clr phenotype (Fig. 1F and 2A) as well as suppressing the Muv phenotype associated with ay75 mutants (Fig. 2B). This intragenic suppressor mutation confers a recessive rod-like larval-lethal phenotype typical of loss of LET-60 RAS activity (data not shown). Sequence analysis demonstrates that ay100 corresponds to a C127AG-to-TAG lesion, resulting in an early truncation (Q43STOP) that is predicted to eliminate RAS function. Fifth, another gain-of-function allele of let-60, ga89 (12), displays a Clr phenotype at 25°C like ay75. Together, these data demonstrate that ay75 is an allele of let-60 ras with dominant gain-of-function features. The Clr phenotype of this mutant suggests that RAS has an important function in EGL-15 FGFR signaling in addition to its well-characterized role in C. elegans LET-23 EGF receptor signaling (4, 15).

FIG. 2.

Penetrance of the Clr (A) and Muv (B) phenotypes associated with let-60(ay75gf). Each phenotype was scored individually in a set of animals (>100) for each of the following genotypes: wild type, ay75/+ heterozygotes raised at 15 and 25°C, ay75/ay75 homozygotes raised at 15°C, ay75 ay100/+ raised at 25°C, and the canonical gain-of-function C. elegans ras allele, let-60(n1046gf), for comparison at 15 and 25°C. The penetrance of the Clr or Muv phenotype is represented as a percentage of the total population examined; error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. For clarity, error bars are not shown for penetrances that are less than 1%; all of these values have 95% confidence intervals that are also less than 1%.

TABLE 1.

Brood sizes of animals carrying ay75 mutations at various temperatures

| Genotype | Brood sizea at:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 15°C | 20°C | 25°C | |

| Wild type | 255 ± 53 (9) | 267 ± 26 (9) | 228 ± 42 (9) |

| ay75/+b | 149 ± 51 (25) | 24 ± 16 (31) | 0.5 ± 1 (29) |

| ay75/ay75 | 3.4 ± 4.4 (15) | 0.7 ± 1.1 (9) | <0.1 (11) |

| ay75 ay100/+c | 280 ± 82 (10) | 232 ± 31 (20) | 139 ± 47 (10) |

Data are reported as means ± standard deviations; the number of broods scored is shown in parentheses.

Animals were of the genotype let-60(ay75)/dpy-20(e1362).

Animals were of the genotype let-60(ay75 ay100) unc-22(e66)/dpy-20(e1362).

The finding that hyperactivation of LET-60 RAS can lead to a Clr phenotype similar to that conferred by hyperactivation of the EGL-15 FGFR suggests that LET-60 RAS may be a normal component of this EGL-15 signaling pathway. Although many components of EGL-15 signaling were identified in an extensive screen for clr-1(e1745ts) suppressors (11), alleles of let-60 ras were not isolated in that screen. Therefore, we directly tested several reduction-of-function alleles of let-60 for their ability to suppress the Clr phenotype of clr-1(e1745ts). Neither let-60(n2021) nor let-60(n2035), two hypomorphic alleles of let-60 ras (4), can suppress the Clr phenotype of clr-1(e1745ts) (Table 2). Stronger alleles of let-60 confer a completely penetrant rod-like larval lethality (4) that cannot be distinguished at the level of Nomarski optics from the Clr phenotype of clr-1 mutants. Thus, we could not assess the Clr/Soc phenotype of a null allele of let-60 directly. To circumvent this problem, an allele of lin-1 was used to suppress the rod-like larval lethality of the null allele let-60(ay75 ay100) (16). While clr-1(e1745ts); lin-1(e1275ts) animals are Clr, clr-1(e1745ts); lin-1(e1275ts) let-60(ay75 ay100) animals are Soc (Table 2). Thus, hyperactivation of let-60 can confer a Clr phenotype and loss of let-60 can suppress the Clr phenotype due to hyperactivation of EGL-15, implicating LET-60 RAS in this EGL-15 FGFR signaling pathway.

TABLE 2.

Epistasis analysis of soc genes and clr-1(e1745ts) and let-60(ga89)

| Gene | Allele | Phenotypea

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| clr-1(e1745ts) | let-60(ga89) | ||

| egl-15b | n1477ts, hypomorph | Soc | Clr |

| soc-1 | n1789, null | Soc | Clr |

| ptp-2 | op194, null | Soc | Clr |

| sem-5 | n1779, hypomorph | Soc | Clr |

| ay73, null | Soc | Clr | |

| let-341 | n2183, hypomorph | Soc | Clr |

| s1031, null | Soc | NDc | |

| let-60 | n2021, hypomorph | Clr | NAd |

| n2035, hypomorph | Clr | NA | |

| ay75ay100, null | Soce | NA | |

| soc-2 | n1774, hypomorph | Soc | Soc |

| mek-2 | n2678, null | Soc | ND |

| mpk-1 | ga117, null | Soc | Soc |

Phenotypes were assayed at 25°C, a temperature at which these strains are 100% penetrant for their Soc or Clr phenotypes.

Epistasis using a null allele of egl-15 was not feasible due to the inviability of let-60(ga89); egl-15(n1454).

ND, not determined.

NA, not applicable.

Assayed in a lin-1(e1275ts) background.

The MAPK cascade is required for the Clr phenotype.

Many functions of LET-60 RAS are mediated by the MAPK cascade, which consists of the serine/threonine kinases LIN-45 RAF, MEK-2 MAPKK, and MPK-1 MAPK (17, 24, 26, 56). We tested loss-of-function mutations in the genes encoding MAPKK and MAPK for their ability to suppress the Clr phenotype of clr-1(e1745ts). While mutations in these genes were not isolated in the original Soc screen, alleles of both mek-2 (n2678) and mpk-1 (ku1 and ga117) were found to confer a Soc phenotype when examined in a clr-1(e1745ts) background (Table 2), implicating this MAPK cascade in EGL-15 signaling. Due to interfering pleiotropies, we were unable to test lin-45 raf directly, but the involvement of let-60, mek-2, and mpk-1 strongly implicate LIN-45 RAF as a component of this EGL-15 pathway.

Epistasis analysis of soc genes using let-60(gf)

We used the Clr phenotype conferred by let-60(ga89) to analyze the epistatic relationship between the soc genes and let-60 ras. Consistent with the well-characterized roles that these soc genes play in RTK signaling, let-60 is epistatic to egl-15, sem-5, and let-341/sos-1, while mpk-1 is epistatic to let-60 (Table 2). let-60 is also epistatic to soc-1, suggesting that soc-1 acts either between EGL-15 and RAS or independently of LET-60 RAS. To understand the function of soc-1 better, we have molecularly and genetically characterized its role in EGL-15 signaling pathways.

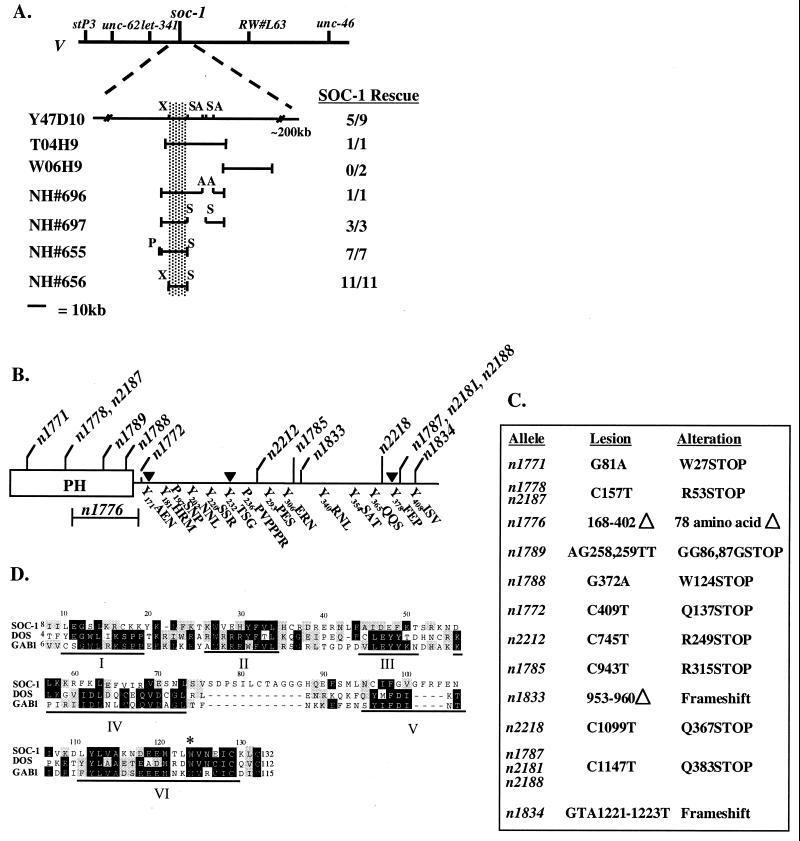

soc-1 encodes an MSA.

soc-1 was cloned by a germ line transformation rescue assay using yeast artificial chromosomes (YACs) and cosmids corresponding to its genetic map position. The soc-1-rescuing region was initially defined by rescue with the YAC Y47D10 (L. DeLong and M. J. Stern, unpublished data). Subsequently, a single cosmid, T04H9, that efficiently rescues the Soc phenotype of clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1(n1789) was identified. The rescuing activity of T04H9 was pared down to a 10-kb XhoI-to-SacII fragment (Fig. 3A). This rescuing fragment contains a single open reading frame according to GENEFINDER predictions. We cloned a soc-1 cDNA using reverse transcription-PCR and 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends. The resulting 1,350-bp cDNA contains a single open reading frame with an in-frame stop codon preceding the first potential ATG start site. Using the germ line transformation rescue assay, we have demonstrated that this cDNA can restore wild-type soc-1 function (Fig. 4). Similar, although not identical, to GENEFINDER predictions, this cDNA encodes a protein of 430 amino acids with an N-terminal PH domain. PH domains are found in a variety of signaling molecules with and without enzymatic activity and are thought to mediate targeting of these proteins to the cell membrane through interactions with phosphoinositides and/or interactions with other proteins (27, 33). The PH domain of SOC-1 is most similar to the PH domains of the MSA proteins Drosophila DOS and mammalian GAB1 (Fig. 3D) (20, 41). MSA proteins link RTKs with downstream pathways by recruiting SH2 and SH3 domain-containing signaling components to assemble a signaling complex at the plasma membrane near the activated receptor (37, 38). The C-terminal two-thirds of SOC-1 does not share significant sequence identity with any other known protein but has 12 potential tyrosine phosphorylation sites (Fig. 3B). In addition, there are two polyproline motifs in the C terminus of SOC-1 that could function as binding sites for SH3 domain-containing proteins. Despite lacking a definitive sequence ortholog, its overall structural organization, PH domain similarity, and tyrosyl and polyprolyl motifs strongly suggest that SOC-1 is an MSA protein most similar to DOS and GAB1.

FIG. 3.

soc-1 encodes an MSA protein. (A) Cloning of soc-1 by germ line transformation rescue. The genetic map position of soc-1 is shown with respect to flanking genes and Bristol/Bergerac restriction fragment length polymorphisms. The clones tested for soc-1-rescuing activity are placed with respect to the rescuing YAC, Y47D10. Germ line transformation rescue results for the cosmids (T04H9 and W06H9) and derivatives of the rescuing cosmid T04H9 are shown as the number of stably transformed lines capable of rescuing the Soc phenotype of clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1(n1789) animals; soc-1 rescue with Y47D10 was tested in clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1(n1833) animals. A break in the bar designates a deletion. The position of the minimal rescuing fragment is indicated by shading. Relevant restriction sites: A, ApaI; P, PstI; S, SacII; X, XhoI. (B) Schematic representation of SOC-1. The open box represents the N-terminal PH domain. The positions of allele lesions are noted at the top. The sequences of the C-terminal tyrosyl and polyprolyl motifs are listed at the bottom; 4 of the 12 tyrosines within the C terminus of SOC-1 are found within recognizable SH2 domain binding motifs (47). Three of these tyrosine motifs correspond to predicted docking sites for two SH2 domain-containing soc genes: Y202NNL (SEM-5/GRB2), Y340RNL (SEM-5/GRB2), and Y408ISV (PTP-2/SHP2). In addition, Y181HRM is a predicted phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase SH2 domain binding motif. Arrowheads indicate the 3′ extent of the C-terminal truncations (see Fig. 5). (C) Mutational lesions. soc-1 alleles are listed with their corresponding DNA lesions, numbered according to the soc-1 cDNA starting at the initiation codon. All mutations were induced using EMS mutagenesis, except for n1789, n1833, and n1834, which were induced with gamma rays (11). (D) Alignment of PH domains from SOC-1, Drosophila DOS, and human GAB1. Amino acid sequences corresponding to the PH domain as defined by the Pfam protein motif finder from SOC-1 (positions 8 to 132), DOS (4 to 112), and GAB1 (6 to 115) were aligned using the CLUSTAL method and DNAstar sequence analysis software. Sequence identities are shown in black, and similarities are shaded. Subdomain locations are indicated with a bar and a roman numeral below the alignment (33); the invariant tryptophan found in all PH domains is indicated with an asterisk above the alignment. Amino acid positions with respect to the SOC-1 sequence are noted above the alignment.

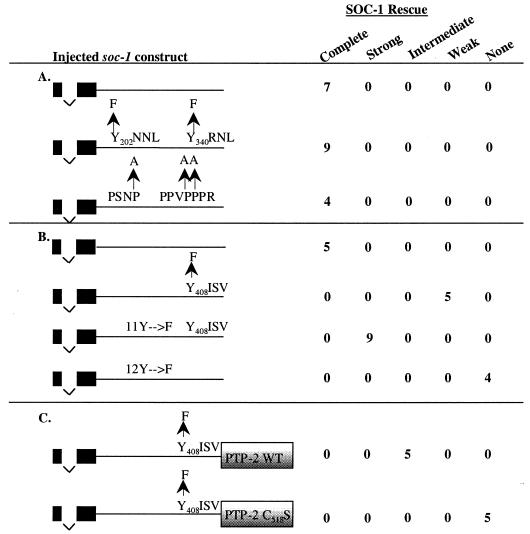

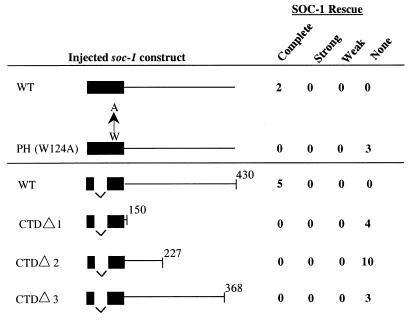

FIG. 4.

Functional analysis of potential protein binding sites in the C-terminal tail of SOC-1. (A) Canonical SEM-5 binding sites in SOC-1 are dispensable for function. (B) The C-terminal Y408 is critical for SOC-1 function. (C) Fusing an active phosphatase domain from PTP-2 to SOC-1 can enhance signaling by SOC-1(Y408F). WT, wild type. The SOC-1 PH domain is depicted by solid rectangles, and the SOC-1 C-terminal tail is indicated by a thick line. Injected constructs contain a single intron between exons one and two. Tyrosine-to-phenylalanine and proline-to-alanine changes are depicted above each construct. The C-terminal SH2 domain (C-SH2) and phosphatase domain (PTP) of PTP-2 are depicted as shaded boxes. PTP C518S bears a cysteine-to-serine mutation within the catalytic core of PTP-2. Data shown are for untagged constructs in panels A and C and for GFP-tagged constructs in panel B. Stably transformed lines were isolated as described for Fig. 3 and tested for rescue of the Soc phenotype of clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1(n1789) by shifting L4 transformants to the nonpermissive temperature. The extent of rescue for each of the lines was assigned to one of five categories: (i) complete, animals display a Clr phenotype similar to that seen when clr-1(e1745ts) L4 animals are shifted to the nonpermissive temperature; (ii) strong, animals are sterile and display a reduced but obvious Clr phenotype; (iii) intermediate, animals are not sterile and display an obvious Clr phenotype; (iv) weak, animals are fertile and only subtly Clr (defect confirmed by Nomarski microscopy); or (v) none, animals are completely Soc and indistinguishable from the injected strain clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1(n1789).

Fifteen independent alleles of soc-1 have been isolated in both EMS and gamma ray mutagenesis screens for soc genes. We have identified mutations within this coding region in all of these alleles of soc-1 (Fig. 3C). All but one of the lesions in soc-1 are predicted to result in the premature truncation of the gene product; the remaining lesion (n1776) corresponds to a 78-amino-acid deletion within the PH domain. Several of these lesions (n1771, n1778, n2187, n1789, and 1788) are early nonsense mutations which are likely to be null alleles of soc-1. The spectrum of soc-1 mutations isolated indicates that it may be necessary to severely cripple soc-1 function in order to compromise EGL-15 signaling.

Structure-function analysis of SOC-1.

soc-1 and sem-5/GRB2 are both soc genes that behave similarly in epistasis tests (Table 2) (44), suggesting the possibility that SEM-5 might associate directly with SOC-1 to mediate EGL-15 signal transduction. SOC-1 has several motifs in its C terminus with the potential to interact directly with SEM-5. These include two YXNX motifs and two polyproline motifs that are potential binding sites for SEM-5 via its SH2 and SH3 domains, respectively (Fig. 3B) (22, 30, 47). To assess the importance of these motifs for SOC-1 function, we tested variants of the soc-1-rescuing fragment in which these motifs were specifically mutated (Fig. 4A). soc-1-rescuing fragments with altered YXNX or polyproline motifs were introduced into clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1(n1789) mutant animals, and stably transformed progeny were scored for rescue of the Soc phenotype. For both the YXNX and polyproline motifs, the mutated variants rescued the soc-1(n1789) defect as well as the wild-type soc-1 construct, suggesting that neither of these motifs on its own is essential for SOC-1 function.

To address more broadly how SOC-1 functions in EGL-15 signaling, we investigated the importance of the two major SOC-1 domains, the PH domain and the C-terminal tail. To monitor expression of the transgenic constructs, GFP was appended to the carboxy termini of these constructs (see Materials and Methods). Two different soc-1 cDNA/genomic chimeras (either containing the entire wild-type soc-1 cDNA or maintaining a single intron within the PH domain) both showed highly penetrant rescue activity in transiently transformed animals (data not shown) and in stably inherited lines (Fig. 4 and 5). Both of these constructs showed the same pattern of GFP expression, although the construct containing the additional intron resulted in more robust expression. None of the modifications tested affected either the cellular distribution or the levels of GFP fluorescence of soc-1::GFP, demonstrating that compromised SOC-1 function was unlikely to be due to an altered pattern or extent of protein expression.

FIG. 5.

Both the PH domain and C-terminal tail are required for SOC-1 function. Injected constructs are diagrammed as described for Fig. 4, and amino acid positions are noted above the diagram. The PH domain mutation, W124A, and its wild-type (WT) control were tested in an intronless construct without GFP. When GFP was appended to monitor expression, these constructs showed a pattern of expression that was indistinguishable from that of the wild-type control. The extent of the depicted truncations with respect to the tyrosyl and polyprolyl motifs within the C terminus of SOC-1 is indicated by arrowheads in Fig. 3B.

To investigate whether the PH domain of SOC-1 is important for function in vivo, we used site-directed mutagenesis to change the invariant tryptophan found in all PH domains to alanine (W124A) (33). This change has been shown to abrogate the ability of PH domain-containing proteins to translocate from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane in response to signal in cell culture systems (36, 52). Despite being expressed similarly to the wild-type rescuing construct, the SOC-1(W124A) PH domain mutant fails to rescue the Soc phenotype of clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1(n1789), indicating that the PH domain is essential for SOC-1 to function properly (Fig. 5). To investigate the importance of the C-terminal tail of SOC-1, we created a series of three nested C-terminal deletions and tested these constructs for rescue and expression. Despite retaining a normal expression pattern by GFP, these constructs all fail to rescue soc-1(n1789) (Fig. 5), suggesting that a critical element for SOC-1 function may be located near the very C terminus of SOC-1. These results are consistent with the chromosomal mutations identified in the alleles of soc-1, including several that are predicted to truncate only a small C-terminal portion of SOC-1 (Fig. 3B).

SOC-1–PTP-2 association appears to be critical for EGL-15 signaling.

SOC-1 is structurally similar to the Drosophila MSA DOS. An important function of DOS appears to be recruitment of the tyrosine phosphatase CSW (3, 18, 19). An ortholog of vertebrate SHP2, CSW functions in a number of Drosophila RTK signaling pathways, including the Breathless FGFR pathway (39, 40). SHP2 in vertebrates is also known to function in signaling via FGFRs, for example, during mesoderm induction in Xenopus development (50) and in the differentiation of PC12 cells in culture (14). These findings suggest that the SHP2 ortholog in C. elegans might function in EGL-15 FGFR signal transduction.

The C. elegans SHP2 ortholog, PTP-2, was identified as a positive mediator of LET-23/EGF receptor signal transduction (13). Like CSW and SHP2, PTP-2 has two SH2 domains at its amino terminus followed by a carboxy-terminal phosphatase domain. We found that a mutation which abolishes PTP-2 function, ptp-2(op194), suppresses the Clr phenotype of clr-1(e1745ts) animals, demonstrating that ptp-2 is a soc gene. ptp-2 also behaves similarly to soc-1 in epistasis analysis with let-60(ga89) (Table 2), suggesting that PTP-2 may act in conjunction with SOC-1 to mediate EGL-15 signaling.

To test the requirement of the different domains of PTP-2 for its function in this pathway, a transformation rescue assay was developed for the Soc phenotype of ptp-2(op194) (see Materials and Methods). Mutations in ptp-2 were introduced into a genomic rescuing fragment to test independently the requirement of each SH2 domain and the phosphatase domain. As shown in Table 3, mutations that are predicted to abolish the function of either SH2 domain or the catalytic activity of the phosphatase domain also abolish ptp-2-rescuing activity. These results suggest that the function of both SH2 domains and the catalytic activity of PTP-2 are required for efficient EGL-15 signaling. The similar epistasis results for soc-1 and ptp-2 and the SH2 domain requirement for PTP-2 function suggest the possibility that EGL-15 signaling may require PTP-2 to be recruited via its SH2 domain(s) to SOC-1.

TABLE 3.

Structure-function analysis of PTP-2

| PTP-2 | Mutated domain | Soc rescuea (stable lines) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 4/4 | |

| R36E | N-SH2 | 0/3 |

| R159E | C-SH2 | 0/3 |

| C518S | PTPase | 0/2 |

Soc rescue is defined as rescue of the Soc phenotype of the clr-1(e1745ts) ptp-2(op194) strain derived from the parental clr-1(e1745ts) ptp-2(op194)/mIn1 strain.

Rescue data from the serial C-terminal truncations of SOC-1 (Fig. 5) suggest an important function for the extreme carboxy-terminal sequences of SOC-1. Within this region, SOC-1 contains a tyrosine residue surrounded by sequences that constitute an ideal binding site for the N-terminal SH2 domain of the PTP-2 ortholog, SHP2 (47). Mutation of this tyrosine (Y408) to phenylalanine results in a dramatic reduction in soc-1-rescuing activity (Fig. 4B). Transgenic animals carrying a multicopy array that contains the Y408→F mutated form of SOC-1 display an essentially nonrescued phenotype, although minimal rescuing activity can be detected when the transformed animals are viewed using Nomarski optics. Conversely, when the remaining 11 tyrosines in the C-terminal tail of SOC-1 are mutated, rescuing activity remains quite robust. Mutating all 12 tyrosines in the C terminus of SOC-1 to phenylalanine (12Y→F) completely abolishes soc-1-rescuing activity, indicating that the rescuing activity remaining in the Y408→F construct is mediated by one or more of these other tyrosine residues (Fig. 4B).

These results suggest that one critical function for SOC-1 in EGL-15 signaling is to recruit PTP-2 via its SH2 domain(s) to a specific phosphotyrosyl motif within the C-terminal tail of SOC-1. This function appears to be mediated primarily through Y408, but additional PTP-2 binding sites that contribute to the ability of SOC-1 to recruit PTP-2 may exist within the C-terminal sequences of SOC-1. To test this hypothesis, we constructed a chimeric molecule fusing the catalytic portion of PTP-2 directly to SOC-1(Y408F). This fusion can partially rescue soc-1 mutant animals (Fig. 4C). By contrast, a mutated version of this construct that should eliminate its phosphatase activity (C518S) fails to rescue soc-1 mutants. These data support a model in which SOC-1 can serve to recruit PTP-2 via Y408 to help mediate EGL-15 signaling.

SOC-1 does not mediate all aspects of EGL-15 signaling.

In addition to conferring a Soc phenotype in a clr-1 mutant background, soc-1 null alleles confer a Scr body morphology in a wild-type background (Fig. 6C). This phenotype is similar to the Scr defect observed in animals homozygous for hypomorphic alleles of egl-15 (11). Similar to the case for these egl-15 alleles, the Scr phenotype of soc-1 null mutants is predominantly suppressed in a clr-1(e1745ts) background, resulting in an animal that appears to be essentially wild type (Fig. 6D). The ability of clr-1(e1745ts) to suppress the Scr phenotype of soc-1 null mutants even at the permissive temperature for clr-1(e1745ts) suggests that soc-1 null mutants reduce signaling to a level that is sensitive to small perturbations in pathway activity. Distinct from the phenotype of soc-1(n1789) null mutants, egl-15 null mutants display a more severe phenotype and arrest in the first larval stage (Fig. 6B) (11). This result indicates that some signaling activities of EGL-15 are independent of SOC-1.

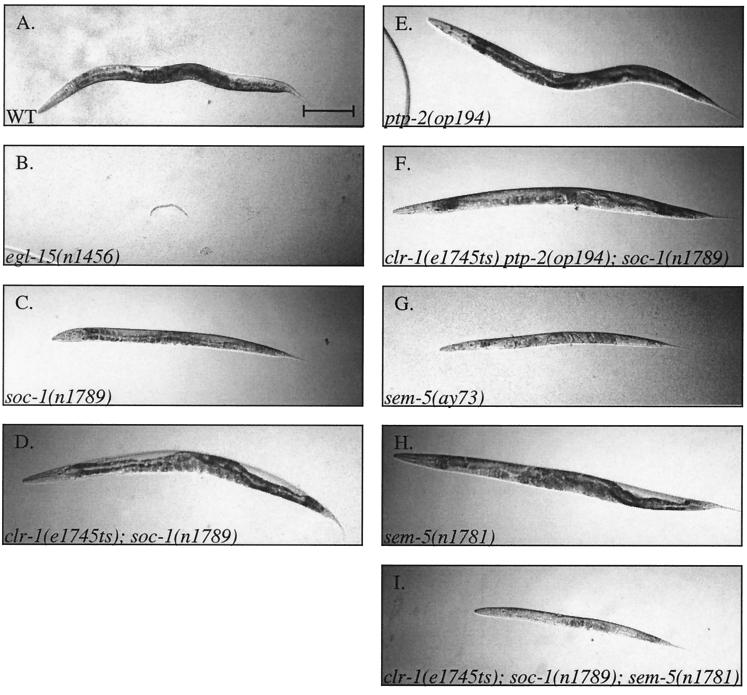

FIG. 6.

Interactions between genes involved in egl-15 signaling. Bright-field photographs comparing the Scr phenotypes of worms carrying mutations in genes involved in egl-15 signaling are shown. All animals were photographed at a magnification of ×10; bar, 200 μm. The animals pictured are representative of nonoverlapping phenotypic classes where wild-type or non-Scr and Scr are clearly distinguishable. (A) Wild type (WT). (B) egl-15(n1456) null mutant arrested larva. (C) soc-1(n1789) Scr hermaphrodite. (D) clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1(n1789) Soc, non-Scr hermaphrodite. (E) ptp-2(op194) non-Scr hermaphrodite. (F) clr-1(e1745ts) ptp-2(op194); soc-1(n1789) non-Scr hermaphrodite. (G) sem-5(ay73) Scr hermaphrodite. (H) sem-5(n1781) non-Scr hermaphrodite. (I) clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1(n1789); sem-5(n1781) extremely Scr hermaphrodite. The animals shown in panels B, E, F, and G are homozygotes derived from mothers heterozygous for either egl-15(n1456), ptp-2(op194), or sem5(ay73).

We have used the Scr phenotype, which is shared by several genes implicated in EGL-15 signaling, to assess how SOC-1 functions with other EGL-15 signaling components. The sem-5 null mutant, sem-5(ay73), displays a partially penetrant rod-like larval lethality when segregated from a heterozygous mother. However, most progeny survive and display an extremely Scr phenotype (Fig. 6G). These animals are vulvaless, and their small number of progeny die within their mothers. Less severe alleles of sem-5 display a spectrum of phenotypes ranging from non-Scr (Fig. 6H) to extremely Scr (48). By contrast, the ptp-2 null mutant, ptp-2(op194), is non-Scr both in a clr-1(e1745ts) background and in a clr-1(+) background (data not shown and Fig. 6E). To test for interactions between soc-1 and either ptp-2 or sem-5, we built double mutants using null alleles of soc-1 and ptp-2 and non-Scr alleles of sem-5 in a clr-1(e1745ts) mutant background. clr-1(e1745ts); ptp-2(op194); soc-1(n1789) triple mutant animals are non-Scr, similar to each of the clr-1 double mutants (Fig. 6F). Thus, mutations in ptp-2 and soc-1 do not show dramatic synergistic effects, consistent with these proteins functioning together to mediate a portion of EGL-15 signal transduction. In sharp contrast to this result with ptp-2, mutations in soc-1 and sem-5 synergize dramatically. Neither the sem-5(n1781) nor the sem-5(n1779) mutant (both weak alleles of sem-5) is Scr either alone or in a clr-1(e1745ts) background (Fig. 6H and data not shown) (11). The triple mutant clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1(n1789); sem-5(n1781) is extremely Scr (Fig. 6I), while the clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1(n1789); sem-5(n1779) triple mutant is nonviable and arrests at early larval stages. In fact, clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1(n1789) animals are so sensitive to perturbations of sem-5 activity that introducing the sem-5(n1779) mutation as a heterozygote makes these animals variably sick and Scr. These results demonstrate a strong synergistic interaction between soc-1 and sem-5 mutations.

Since sem-5 is involved in signaling pathways other than EGL-15, the dramatic synergism observed between soc-1 and sem-5 might be due to the additive effect of defects in different pathways. In addition to its role in EGL-15 signaling, SEM-5 plays an important role in the C. elegans LET-23/EGF receptor signaling pathway, which is essential for viability (10). Defects in this essential function of SEM-5 result in a characteristic rod-like larval lethality. The clr-1; soc-1; sem-5 triple mutants do not display the rod-like larval lethality associated with reduced LET-23 signaling. Rather, the triple mutants display the Scr phenotype, consistent with reduced levels of EGL-15 signaling. Thus, the synergism observed between soc-1 and sem-5 appears to reflect deficits in EGL-15 signaling specifically rather than combined losses in both EGL-15 and LET-23 signaling. These results further support the hypothesis that SOC-1 and PTP-2 act together to mediate a branch of EGL-15 signal transduction and indicate that SEM-5 is likely to mediate at least part of the SOC-1-independent signaling activity downstream of EGL-15.

DISCUSSION

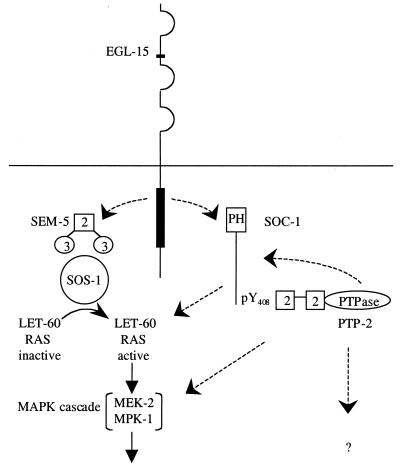

While several components that are critical to EGL-15 signaling have been described previously (8, 10, 11, 44), we have now identified many additional components which allow us to begin to assemble an EGL-15 signaling pathway. We present evidence supporting the involvement of LET-60 RAS and the MAPK cascade in EGL-15 FGFR signal transduction. We isolated a new allele of let-60 ras, ay75, and showed that it is a gain-of-function allele that confers a Clr phenotype, characteristic of hyperactivation of the EGL-15 FGFR. Additionally, we showed that loss of LET-60 RAS can confer a Soc phenotype, supporting a normal role for LET-60 RAS in this Clr/Soc pathway. Mutations in mek-2 and mpk-1 are also Soc, implicating the MAPK cascade in mediating this aspect of EGL-15 signaling. Thus, our data strongly suggest that EGL-15 signals via SEM-5/SOS-1 to the RAS/MAPK pathway. Exactly how the signal is transduced from EGL-15 to this cascade remains unresolved.

To further our understanding of EGL-15 signal transduction, we cloned soc-1 and demonstrated that it has both structural and functional similarities to Drosophila DOS. Like DOS, SOC-1 has an N-terminal PH domain followed by a C-terminal tail with tyrosine residues and polyproline motifs, suggesting that it functions as an MSA protein. In Drosophila RTK signal transduction pathways, DOS function is closely linked to the tyrosine phosphatase CSW (3, 18, 19). We have shown that the C. elegans ortholog of CSW, ptp-2, like soc-1 is also a soc gene, supporting a similar relationship between SOC-1 and PTP-2 in EGL-15 signaling.

Our genetic and structure-function analyses support the hypothesis that SOC-1 and PTP-2 function as a signaling cassette to transduce the EGL-15 signal. First, we found that SOC-1 Y408, a predicted SHP2/PTP-2 binding site, is critical for SOC-1 function. Experiments with Drosophila have demonstrated that a similar C-terminal CSW binding site is also critical for DOS function (3, 19). Second, PTP-2 requires an intact SH2 domain(s) to mediate EGL-15 signaling. Third, a chimeric protein that fuses the C-terminal SH2 and phosphatase domains of PTP-2 to SOC-1(Y408F) can restore some of the lost signaling potential of SOC-1(Y408F). Fourth, although both SOC-1 and PTP-2 function to mediate EGL-15 signaling, ptp-2; soc-1 double mutants do not reduce EGL-15 pathway activity to a greater extent than the single mutants. These data support a model in which SOC-1 and PTP-2 function together to mediate EGL-15 signaling. More specifically, in response to EGL-15 activation, SOC-1 is likely phosphorylated at Y408, enabling SOC-1 to recruit PTP-2 via a direct interaction between the C-terminal tail of SOC-1 and the SH2 domain(s) of PTP-2.

Two paradigms from other signaling systems provide a context for thinking about how a SOC-1/PTP-2 cassette might function in EGL-15 signaling. The first of these paradigms rests on the high degree of structural similarity between SOC-1 and the MSAs GAB1 and DOS. These proteins all have N-terminal PH domains followed by a series of tyrosyl and polyprolyl motifs in their C-terminal tails. These domains not only share a common structure but also appear to share common functions. The SOC-1 PH domain is most similar to the GAB1 PH domain, and the PH domains of GAB1 and DOS are functionally interchangeable, suggesting that a common function is carried out by these PH domains (3). The C-terminal tails of SOC-1 and DOS perform a common function to recruit PTP-2/CSW. This function is likely to be conserved in mammals, since the association of GAB1 with SHP2 plays an important role during epithelial morphogenesis (29, 42).

In addition to its association with SHP2, GAB1 has a well-established relationship with GRB2. Initially identified as the GRB2-associated binder 1, GAB1 associates with GRB2 by a phosphotyrosine-independent mechanism (20). We tested a possible association between SOC-1 and SEM-5 and found that neither the canonical SEM-5 SH2 binding sites nor the canonical SEM-5 SH3 binding sites in SOC-1 are essential for SOC-1 function. More recently, the association between GAB1 and GRB2 has been shown to be mediated in part by a noncanonical GRB2 SH3 domain binding site (termed GBS1) as well as a canonical GRB2 SH3 binding site (termed GBS2) (42). This newly identified GBS1 motif is found in both DOS and SOC-1, further supporting the structural homology among these proteins. The GBS1 motif in SOC-1 presents an alternative mechanism by which SOC-1 may associate with SEM-5 in a manner similar to that described for GAB1.

Although structurally distinct from SOC-1, the MSA protein FRS2 offers a second paradigm to consider as a functional analog for SOC-1. FRS2 plays a key role in FGFR signaling by linking the FGFR to GRB2 and the RAS/MAPK cascade (25, 53). In addition to recruiting GRB2 directly, FRS2 can associate with SHP2, offering an indirect means to recruit GRB2 (14). This recruitment could be mediated via known GRB2 binding sites within the C terminus of SHP2 (5). Our results indicate that SOC-1 does not act similarly. First, since its phosphotyrosine motifs predicted to bind SEM-5 are not essential for SOC-1 function, SOC-1 does not appear to recruit SEM-5 directly. Second, although our data suggest a direct interaction between PTP-2 and SOC-1 that is important for SOC-1 function, SOC-1 is unlikely to recruit SEM-5 via PTP-2, since PTP-2 does not have canonical GRB2 binding sites within its C-terminal tail. Thus, if SOC-1 recruits SEM-5 to activate RAS signaling, it must accomplish this by a different mechanism.

If SOC-1 does not play a direct role in linking EGL-15 signaling to the activation of the RAS/MAPK cascade, how might this link be made? Unlike mammalian FGFRs, EGL-15 may be able to associate directly with GRB2 through phosphotyrosyl motifs within its intracellular region. EGL-15 contains two potential phosphotyrosine motifs predicted to bind the SH2 domain of SEM-5, although these do not appear to be essential for EGL-15 function (C. Branda and M. J. Stern, unpublished data). Alternatively, a C. elegans predicted gene, F54D12.6 (7), that has similarity to FRS2 may perform an FRS2-like function to recruit GRB2/SOS/RAS during EGL-15 signaling. The role of this gene in EGL-15 signaling is currently being investigated.

It is not yet clear which of these two paradigms SOC-1 follows most closely. Similar to FRS2, SOC-1 appears to be a relatively specific adaptor for EGL-15 signaling. This is in contrast to GAB1 and DOS, which have been implicated in a number of RTK pathways and may represent more promiscuous adaptor proteins. Mechanistically, however, SOC-1 appears to function most like DOS in that one of its critical functions is to recruit PTP-2/CSW during signal transduction. Although DOS has not been implicated in FGFR signaling to date, a role for GAB1 was recently identified in linking FGFR activation with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling (34). The identification of SOC-1 as an important component of EGL-15 FGFR signaling implicates GAB1 or DOS in FGFR signaling in their respective systems as well.

Our data establish that the Clr/Soc EGL-15 pathway utilizes a RAS/MAPK signaling cascade and also define a role for the SOC-1/PTP-2 cassette in EGL-15 FGFR signaling. Several lines of evidence suggest that SOC-1/PTP-2 may act in a parallel signaling branch that has a modulatory effect on RAS signaling downstream of EGL-15 (Fig. 7). First, we have observed a strong synergism between sem-5 mutations and null alleles of soc-1. Second, a supporting parallel pathway might explain why two different let-60 gain-of-function mutations confer only a late-onset Clr phenotype rather than the full Clr phenotype observed in clr-1 mutants. Third, a parallel-pathway model can help explain why so many of these soc genes, including let-60, ptp-2, and soc-1, require strong mutations to confer a Soc phenotype. Lastly, this model is supported by data for Drosophila that suggest a complex interdependence of the RAS and DOS/CSW pathways (1, 2). Unraveling the precise molecular mechanisms by which SOC-1/PTP-2 contributes to signaling will be crucial to a more complete understanding of RTK signal transduction.

FIG. 7.

Model of C. elegans EGL-15/FGFR signaling. EGL-15 activation leads to the phosphorylation of SOC-1 on tyrosine 408; this event triggers PTP-2 recruitment and/or activation. In addition, EGL-15 activates the canonical SEM-5/SOS-1/RAS/MAPK pathway. Potential targets of the SOC-1/PTP-2 cassette and/or its role in modulating activity of the RAS/MAPK cascade are indicated by dashed lines. Precisely how activation of EGL-15 triggers SOC-1 and SEM-5 to participate in EGL-15 signal transduction remains unresolved (indicated by dashed lines from the receptor).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tom Duchesne for isolating let-60(ay75); Leslie DeLong for additional genetic mapping of soc-1, initial YAC rescue of soc-1, and help in characterization of let-60(ay75); Laura Selfors for restriction mapping of Y47D10 and assaying soc-1 rescue using cosmid pools; Peng Huang for assistance with soc-1 site-directed mutagenesis; Tim Schedl for providing the ptp-2(op194); let-60(ga89) strain; Catherine Branda and Sandra Mayday for constructing clr-1(e1745ts); soc-1(n1789); sem-5(n1781); Alan Coulson for providing cosmids; and Anton Bennett and David Stern for advice. Some nematode strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center.

J. L. Schutzman and C. Z. Borland contributed equally to this paper.

The Caenorhabditis Genetics Center is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). This work was supported by American Cancer Society grant RPG-98-070-01-DDC. M. K. Robinson was supported by NRSA postdoctoral fellowship F32 CA76713.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allard J D, Chang H C, Herbst R, McNeill H, Simon M. The SH2-containing tyrosine phosphatase corkscrew is required during signaling by sevenless, Ras1 and Raf. Development. 1996;122:1137–1146. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.4.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allard J D, Herbst R, Carroll P M, Simon M. Mutational analysis of the Src homology 2 domain protein-tyrosine phosphatase Corkscrew. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13129–13135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bausenwein B S, Schmidt M, Mielke B, Raabe T. In vivo functional analysis of the Daughter of Sevenless protein in receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Mech Dev. 2000;90:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beitel G, Clark S, Horvitz H R. Caenorhabditis elegans ras gene let-60 acts as a switch in the pathway of vulval induction. Nature. 1990;348:503–509. doi: 10.1038/348503a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett A, Tang T, Sugimoto S, Walsh C, Neel B. Protein-tyrosine-phosphatase SHPTP2 couples platelet-derived growth factor receptor b to Ras. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7335–7339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caenorhabditis elegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang C, Hopper N A, Sternberg P. Caenorhabditis elegans SOS-1 is necessary for multiple RAS-mediated developmental signals. EMBO J. 2000;19:3283–3294. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen E, Branda C, Stern M. Genetic enhancers of sem-5 define components of the gonad-independent guidance mechanism controlling sex myoblast migration in Caenorhabditis elegans hermaphrodites. Dev Biol. 1997;182:88–100. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark S G, Stern M J, Horvitz H R. C. elegans cell-signalling gene sem-5 encodes a protein with SH2 and SH3 domains. Nature. 1992;356:340–344. doi: 10.1038/356340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeVore D L, Horvitz H R, Stern M J. An FGF receptor signaling pathway is required for the normal cell migrations of the sex myoblasts in C. elegans hermaphrodites. Cell . 1995;83:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenmann D, Kim S. Mechanism of activation of the Caenorhabditis elegans ras homologue let-60 by a novel, temperature-sensitive, gain-of-function mutation. Genetics. 1997;146:553–565. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.2.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutch M, Flint A, Keller J, Tonks N, Hengartner M. The Caenorhabditis elegans SH2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP-2 participates in signal transduction during oogenesis and vulval development. Genes Dev. 1998;12:571–585. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hadari Y, Kouhara H, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Binding of Shp2 tyrosine phosphatase to FRS2 is essential for fibroblast growth factor-induced PC12 cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3966–3973. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han M, Sternberg P. let-60, a gene that specifies cell fates during C. elegans vulval induction, encodes a ras protein. Cell. 1990;63:921–931. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90495-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han M, Aroian R, Sternberg P. The let-60 locus controls the switch between vulval and nonvulval cell fates in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1990;126:899–913. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.4.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han M, Golden A, Han Y, Sternberg P. C. elegans lin-45 raf gene participates in let-60 ras-stimulated vulval differentiation. Nature. 1993;363:133–140. doi: 10.1038/363133a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herbst R, Carroll P M, Allard J D, Schilling J, Raabe T, Simon M. Daughter of Sevenless is a substrate of the phosphotyrosine phosphatase Corkscrew and functions during Sevenless signaling. Cell. 1996;85:899–909. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herbst R, Zhang X, Qin J, Simon M. Recruitment of the protein tyrosine phosphatase CSW by DOS is an essential step during signaling by the Sevenless receptor tyrosine kinase. EMBO J. 1999;18:6950–6961. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holgado-Madruga M, Emlet D R, Moscatello D K, Godwin A K, Wong A J. A Grb2-associated docking protein in EGF- and insulin-receptor signalling. Nature. 1996;379:560–564. doi: 10.1038/379560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holgado-Madruga M, Moscatello D K, Emlet D R, Dieterich R, Wong A J. Grb2-associated binder-1 mediates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation and the promotion of cell survival by nerve growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12419–12424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kay B, Williamson M, Sudol M. The importance of being proline: the interaction of proline-rich motifs in signaling proteins with their cognate domains. FASEB J. 2000;14:231–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kokel M, Borland C Z, DeLong L, Horvitz H R, Stern M J. clr-1 encodes a receptor tyrosine phosphatase that negatively regulates an FGF receptor signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1425–1437. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kornfeld K, Guan K, Horovitz H R. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene mek-2 is required for vulval induction and encodes a protein similar to the protein kinase MEK. Genes Dev. 1995;9:756–768. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kouhara H, Hadari Y R, Spivak-Kroizman T, Schilling J, Bar-Sagi D, Lax I, Schlessinger J. A lipid-anchored Grb2-binding protein that links FGF-receptor activation to the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway. Cell. 1997;89:693–702. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80252-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lackner M, Kim S. Genetic analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans MAP kinase gene mpk-1. Genetics. 1998;150:103–117. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemmon M, Ferguson K, Schlessinger J. PH domains: diverse sequences with a common fold recruit signaling molecules to the cell surface. Cell. 1996;85:621–624. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowy D, Zhang K, Declue J, Willumsen B. Regulation of p21ras activity. Trends Genet. 1991;7:346–351. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90253-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maroun C R, Holgado-Madruga M, Royal I, Naujokas M A, Fournier T M, Wong A J, Park M. The Gab1 PH domain is required for localization of Gab1 at sites of cell-cell contact and epithelial morphogenesis downstream from the Met receptor tyrosine kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1784–1799. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayer B, Eck M. Minding your p's and q's. Curr Biol. 1995;5:364–367. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCormick F. How receptors turn Ras on. Nature. 1993;363:15–16. doi: 10.1038/363015a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohammadi M, Dikic I, Sorokin A, Burgess W, Jaye M, Schlessinger J. Identification of six novel autophosphorylation sites on fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 and elucidation of their importance in receptor activation and signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:977–989. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Musacchio A, Gibson T, Rice P, Thompson J, Saraste M. The PH domain: a common piece in the structural patchwork of signalling proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:343–348. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90071-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ong S H, Hadari Y R, Gotoh N, Guy G R, Schlessinger J, Lax I. Stimulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase by fibroblast growth factor receptors is mediated by coordinated recruitment of multiple docking proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6074–6079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111114298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Reilly A, Neel B. Structural determinants of SHP-2 function and specificity in Xenopus mesoderm induction. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:161–177. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parent C, Blacklock B, Froehlick W, Murphy D, Devreotes P. G protein signaling events are activated at the leading edge of chemotactic cells. Cell. 1998;95:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81784-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pawson T. Protein modules and signalling networks. Nature. 1995;373:573–580. doi: 10.1038/373573a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pawson T, Scott J. Signaling through scaffold, anchoring, and adaptor proteins. Science. 1997;278:2075–2080. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perkins L A, Larsen I, Perrimon N. corkscrew encodes a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase that functions to transduce the terminal signal from the receptor tyrosine kinase torso. Cell. 1992;70:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90098-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perkins L A, Johnson M R, Melnick M B, Perrimon N. The nonreceptor protein tyrosine phosphatase corkscrew functions in multiple receptor tyrosine kinase pathways in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1996;180:63–81. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raabe T, Riesgo-Escovar J, Liu X, Bausenwein B S, Deak P, Maröy P, Hafen E. DOS, an novel pleckstrin homology domain-containing protein required for signal transduction between Sevenless and Ras1 in Drosophila. Cell. 1996;85:911–920. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schaeper U, Gehring N, Fuchs K, Sachs M, Kempkes B, Birchmeier W. Coupling of Gab1 to c-Met, Grb2, and Shp2 mediates biological responses. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1419–1432. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2000;103:211–225. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Selfors L M, Schutzman J L, Borland C Z, Stern M J. soc-2 encodes a leucine-rich repeat protein implicated in fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6903–6908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi Z Q, Yu D H, Park M, Marshall M, Feng G. Molecular mechanism for the Shp-2 tyrosine phosphatase function in promoting growth factor stimulation of Erk activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1526–1536. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1526-1536.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sieburth D, Sun Q, Han M. SUR-8, a conserved Ras-binding protein with leucine-rich repeats, positively regulates Ras-mediated signaling in C. elegans. Cell. 1998;94:119–130. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Songyang Z, Shoelson S, Chaudhuri M, Gish G, Pawson T, Haser W, King F, Roberts T, Ratnofsky S, Lechleider R, Neel B, Birge R, Fajardo J, Chou M, Hanafusa H, Schaffhausen B, Cantley L. SH2 domains recognize specific phosphopeptide sequences. Cell. 1993;72:767–778. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90404-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stern M J, Marengere L, Daly R, Lowenstein E, Kokel M, Batzer A, Olivier P, Pawson T, Schlessinger J. The human GRB2 and Drosophila Drk genes can functionally replace the Caenorhabditis elegans cell signaling gene sem-5. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:1175–1188. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.11.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sundaram M, Yochem J, Han M. A Ras-mediated signal transduction pathway is involved in the control of sex myoblast migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1996;122:2823–2833. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang T, Freeman R, O'Reilly A, Neel B, Sokol S. The SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase SH-PTP2 is required upstream of MAP kinase for early Xenopus development. Cell. 1995;80:473–483. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90498-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ullrich A, Schlessinger J. Signal transduction by receptors with tyrosine kinase activity. Cell. 1990;61:203–212. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90801-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Varnai P, Rother K I, Balla T. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent membrane association of the Bruton's tyrosine kinase pleckstrin homology domain visualized in single living cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10983–10989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J, Xu H, Li H, Goldfarb M. Broadly expressed SNT-like proteins link FGF receptor stimulation to activators of Ras. Oncogene. 1996;13:721–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weidner K M, DiCesare S, Sachs M, Brinkmann V, Behrens J, Birchmeier W. Interaction between Gab1 and c-Met receptor tyrosine kinase is responsible for epithelial morphogenesis. Nature. 1996;384:173–176. doi: 10.1038/384173a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams B, Schrank C, Huynh R, Shownkeen R, Waterston R H. A genetic mapping system in Caenorhabditis elegans based on polymorphic sequence-tagged sites. Genetics. 1992;131:609–624. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.3.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu Y, Han M. Suppression of activated LET-60 Ras protein defines a role of Caenorhabditis elegans SUR-1 MAP kinase in vulval differentiation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:147–159. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]