Abstract

The hospitality industry worldwide is among the hardest-hit industries from the COVID-19 lockdowns. Initial theoretical and practical observations in the hospitality industry indicate that business model innovation (BMI) might be a solution to recover from and successfully cope with the COVID-19 crisis. Interestingly, some firms in the hospitality industry already started to successfully adapt their business models. This study explores the why and how of these successful recovery attempts through BMI by conducting a multiple case study of six hospitality firms in Austria. We rely on interview data from managers together with one of their main stammgasts for each case, which we triangulate with secondary data for the analysis. Findings show that BMI is applied during and after the crisis to create new revenue streams and secure a higher level of liquidity, with an important role of stammgasts.

Keywords: Business model innovation, Hospitality, Tourism, COVID-19, Crisis, Stammgasts

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic tremendously challenged governments, society, and firms worldwide (Clark et al., 2020). While some industries suffered from minor consequences, firms in the hospitality industry almost completely lost their business for months (Baum and Hai, 2020). Furthermore, the nature of their products and services prevents the possibility of a catch-up effect to compensate for the lost revenues on a long-term base. A meal not being served during the crisis cannot be sold twice later. Moreover, the lockdown might have changed how business in hospitality will be done in the future, given the new rules and regulations concerning hygiene and social distancing together with more hesitant and worried customers. Given this severe and still ongoing crisis, firms in this sector are in a need of adequate mechanisms to recover.

Research on crisis management in the hospitality industry sees good approaches above all in strengthened marketing for local consumers and the reduction of infrastructure. However, government aid is generally regarded as the most important factor in the industry for surviving a crisis (Israeli and Reichel, 2003; Mansfeld, 1999). Ritter and Pedersen (2020) highlight that the COVID-19 crisis will affect established business models (BM). The BM is the firms' unique configuration of its value proposition (i.e., what does the firm offer to whom?), value creation (i.e., how is this value proposition created?) and value capture (i.e., how does the firm generate profits from this?) approach (Clauss, 2017; Clauss et al., 2019). In a recent analysis on family firms’ reactions to the COVID-19 crisis – which also includes firms from the hospitality industry – Kraus et al. (2020) identified temporary business model innovation (BMI) as a potential solution to recover from the crisis. If a BM is innovated through substantial changes in the elements and/or their configuration (Foss and Saebi, 2017), new opportunities can be addressed that increase firm performance and may help hospitality firms to recover.

Research on BM and BMI in the hospitality industry is scarce, but indicates that BM considerations and BMI are empirically relevant in this industry. Bogers and Jensen (2017) provide a taxonomy of different BMs in the gastronomic sector as a basis to assess the potential for BMI. Souto (2015) highlights that BMI can stimulate incremental and radical innovation in the hotel sector. Cheah et al. (2018) found that BMI mediates the relationship between market turbulence and performance in the hospitality industry. Based on these considerations, we identify a relevant research need for answering the question:

“Can BMI be used for overcoming the COVID-19 crisis in the hospitality industry?”

If BMI is a relevant mechanism for hospitality firms to cope with the COVID-19 crisis, it needs to be identified under which conditions these are fostered. Empirical literature has demonstrated that environmental turbulence nurtures BMI activities (Cheah et al., 2018; Clauss et al., 2019). Also, the general management literature highlighted that firms need to identify or source the ideas for BMI across the boundaries of the firm (e.g., Hock-Doepgen et al., 2020; Micheli et al., 2020). In particular, customers have been identified as a valuable source of ideas for new BMs (Clauss et al., 2018; Ebel et al., 2016). Studies in the discourse on innovation in the hospitality industry have highlighted the role of guests, in particular those who are characterized by high involvement, loyalty, and frequent visits to the hospitality firm (Grissemann and Stokburger-Sauer, 2012). Those regular patrons or stammgasts 1 reflect upon the strengths and weaknesses of the hospitality firm and openly communicate potential ideas for innovation (Hjalager, 2010; Kallmuenzer, 2018). Therefore, we further ask:

“What are the drivers of BMI in the hospitality industry during the COVID-19 crisis, and what is the role of stammgasts?”

For answering these two research questions, we employ a multiple case analysis of six hospitality firms located in the mountainous, mixed urban and rural Alpine region of Austria. This region is a prominent and established tourism region (Kallmuenzer and Peters, 2018; Paget et al., 2010) that was struck and suffered strongly from a high number of COVID-19 infections (the winter sports town Ischgl as one of the hotspots from which the virus spread throughout Europe is located in this area) and the subsequent political consequences. Employment statistics for Tyrol, Austria’s federal state with the largest, mostly rural hospitality industry, show that during that time unemployment numbers in hospitality went up by 933% from the beginning of the shutdown on March 5 to May 12, 2020 (AMS, 2020), compared to, for example, an increase of 1521% in the trade industry. Considering that the hospitality industry also serves guests who are not tourists (Okumus et al., 2010), the business in this industry was especially struck as both groups of customers – locals and visitors – were not allowed to visit these firms anymore and only slowly started to return after the sanctions were alleviated and the borders were still closed.

We triangulate the findings of multiple interviews per firm (i.e., managers and stammgasts) and available secondary data for our analysis. Our results suggest that BMI can serve as a strategic response to a crisis for hospitality firms. We discovered inhibiting and enhancing factors that influence BMI in the hospitality industry. Moreover, BMI is rather evolutionary and incremental during the crisis, as it had to be implemented quickly and spontaneously in a period of low liquidity. In contrast to our initial assumption, stammgasts are not the driving forces for BMI in times of crisis, but can serve as initial idea givers to the firms which might initiate BMI. Furthermore, they provide vital financial and psychological support during the crisis and when strategic responses such as BMI are carried out.

This study contributes to research and practice on hospitality management by exploring BMI as a coping mechanism for hospitality firms during a severe crisis, such as the current one caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In this context, we extend previous research on the role of guests for innovation. Moreover, this study contributes to the general ongoing discussion of the antecedents of BMI by highlighting enhancing and inhibiting factors.

2. Theoretical foundation

2.1. Crisis management in the hospitality industry

The handling of crises in the hospitality industry has already been investigated from different perspectives. Above all, the significance of terror and violence in tourism regions played a major role in this consideration (Anson, 1999; Butler and Baum, 1999). Other crisis situations were the financial crisis (del Mar Alonso-Almeida and Bremser, 2013) or crises from natural hazards (Biggs et al., 2012). Early ideas to cope with crisis situations were established by Mansfeld (1999) and consisted of increased marketing efforts to target local customers, the dismantling of infrastructure, and the call for governmental support. Further investigations of Israeli and Reichel (2003) built on a preset of 21 different practices hospitality firms can use to overcome a crisis. Their results showed that the most important factor for surviving a crisis at that time was the possibility of a grace period for local payments. Additionally, hospitality firms can recognize opportunities during crises and charge more from customers through added value. Moreover, in other studies cost reductions play an important role for surviving a crisis (Kraus et al., 2020; Wenzel et al., 2020).

2.2. Innovation in the hospitality industry

Considering the importance of loyal and local customers in the recovery from crises (del Mar Alonso-Almeida and Bremser, 2013), it is important to consider that customers value innovations of hospitality firms (Chen and Elston, 2013; Pikkemaat et al., 2018). In tourism, innovations are defined as "everything that differs from business as usual or which represents a discontinuance of previous practice in some sense for the innovating firm" (Hjalager, 2010, p. 2), and occur in the form of product/service, process, managerial, marketing, or institutional innovations. Hospitality firms themselves are also aware that their customers expect constant innovation (Kallmuenzer, 2018; Tajeddini and Trueman, 2012), and thus attempt to continuously innovate to be able to compete on the market (Thomas and Wood, 2014). However, in most cases and due to often limited financial opportunities and capacities, these are mostly incremental innovations (compared to radical innovations associated with rather technical advancements like the creation of smartphones) of products and services (Pikkemaat and Peters, 2006). As destinations are competing with each other and are often perceived by tourists as one product bundle (Svensson et al., 2005), innovations also often happen jointly by a large number of actors (Baggio, 2011).

2.3. Open innovation in crises

An increasingly important form of innovation is open innovation, which, compared to traditional in-house innovation, is also inspired by external stakeholders (Chesbrough and Bogers, 2014). This form of innovation is still in its infancy in the hospitality sector, and initial research results refer to the guest as an important innovation driver, often evoked by the informal exchange of ideas (Binkhorst and Den Dekker, 2009; Kallmuenzer, 2018). However, hospitality firms first have to implement a culture and processes to systematically follow an open innovation approach (Iglesias-Sánchez et al., 2020), but feedback of guests can already be a fruitful source of inspiration. During crises, open innovation shows to be a viable alternative to keep up with rapidly changing environmental conditions and to identify emerging opportunities (Chesbrough, 2020).

2.4. Business model innovation in crises

Business model innovation (BMI) promises to be a strong response to the COVID-19 crisis (Kraus et al., 2020). Any enterprise has a BM, i.e., a unique configuration of the three mutually enforcing elements value proposition, value creation and value capture (Clauss, 2017; Clauss et al., 2019; Foss and Saebi, 2017), which is either consciously articulated or not (Chesbrough, 2007). The dimension of value proposition describes the firm’s portfolio of proposed solutions and how the firm offers those solutions to the customer (Johnson et al., 2008; Morris et al., 2005). Value creation defines how the firm creates value along its value chain based on its resources and capabilities (Achtenhagen et al., 2013) while value capture refers to how the firm transforms its value proposition into revenues (Clauss, 2017).

BMs are important when firms seek to commercialize their innovations (Chesbrough, 2010; Teece, 2010). BMs are innovation drivers (Schneider and Spieth, 2013), representing the structure in which firms create and capture value from innovative technologies or ideas which, by themselves, do not provide any “single objective value […] until it is commercialized in some way via a business model” (Chesbrough, 2010, p. 354). Given their role in innovation, BMs have become subject to innovation themselves (Schneider and Spieth, 2013).

Foss and Saebi (2017) define BMI as “designed, nontrivial changes to the key elements of a firm's BM and/or the architecture linking these elements” (p. 207). Further, they propose a BM typology that distinguishes four types of BMI based on two dimensions, namely scope (modular changes versus architectural changes) and novelty (new to firm versus new to industry).

Evolutionary BMI evolves as rather voluntary and emergent changes (Demil and Lecocq, 2010) in individual BM components. In contrast, adaptive BMI refers to changes in the entire BM and its architecture (Foss and Saebi, 2017), hence the way how BM components are linked together, as a reaction to changes in the external environment (Teece, 2010). The changes in evolutionary and adaptive BMI are typically new to the firm while not necessarily new to the industry (Saebi et al., 2017). Focused and complex BMI are modular or architectural BM changes, proactively initiated by the firm's management to disrupt market conditions within a respective industry (Foss and Saebi, 2017). Hence, these changes are not only new to the firm, but new to the industry. Focused BMI represents changes in one BM element, whereas complex BMI affects the entire architecture of the BM.

BMI has gained increasing attention among scholars and practitioners over the last years (Foss and Saebi, 2017), but research on BMI in the hospitality industry remains scarce and thus also misses to address its elements and typology. Although innovation is of great importance for hospitality firms' business growth (Thomas and Wood, 2014) and competitiveness (Pikkemaat and Peters, 2006), the role of BMI has ― with some exemptions (Bogers and Jensen, 2017; Cheah et al., 2018; Souto, 2015) ― been widely neglected. This study therefore attempts to explore how these elements and types of BMI are adhered to in the hospitality industry

Interestingly, Cheah et al. (2018) already revealed that BMI helps hospitality firms to generate a sustainable competitive advantage, mainly when operating in turbulent environments. In fact, BMI often occurs as a consequence of external drivers, such as globalization (e.g., Lee et al., 2012), changes in the competitive environment (e.g., De Reuver et al., 2013), new technological opportunities, or new behavioral opportunities (e.g., Wirtz et al., 2010). BMI is vital for firms' success in today's fast-changing, turbulent and volatile environments (Giesen et al., 2010; Pohle and Chapman, 2006). In such environments, well-established and previously successful BMs may be no longer profitable (Chesbrough, 2007, 2010), and the “superior capacity for reinventing your BM before circumstances force you to” (Hamel and Valikangas, 2004, p. 53) becomes an essential source of competitive advantage. In contexts characterized by high environmental volatility, BMI can provide opportunities (Giesen et al., 2010) in, for instance, reacting to altering sources of value creation and value capture (Pohle and Chapman, 2006) and developing new, innovative ways to create and capture value (Amit and Zott, 2010).

Further observations indicate a positive link between BMI and performance (Foss and Saebi, 2017). For instance, financial performance was positively linked to BMI in the IBM 2006 Global CEO Study (Pohle and Chapman, 2006) and BMI may positively influence firm performance in entrepreneurial (Zott and Amit, 2007), small (Aspara et al., 2010) as well as established firms (Cucculelli and Bettinelli, 2015).

3. Methodology

3.1. Research design

To understand how hospitality firms innovate their BMs in reaction to the COVID-19 crisis and why such innovation efforts might be enhanced or inhibited, we adopt a multiple case study method, which is best suited for studying complex, real-life phenomena for which theoretical knowledge is scarce (Eisenhardt, 1989; Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007; Yin, 2017). As pointed out earlier, hardly any research on BMI in the hospitality industry exists, and also the COVID-19 context has a novel quality compared to other crises. However, research on both BMI without our sector specificity and on crises in general exist. Therefore, our qualitative research approach aims to extend existing theory by bridging the context (Bansal and Corley, 2012; Brand et al., 2019).

Single (e.g., Franceschelli et al., 2018; Velu, 2016) and multiple case study research designs (e.g., Bolton and Hannon, 2016; Ghezzi and Cavallo, 2020; Yang et al., 2017) are well-established in the BMI field. We chose to include multiple cases to enhance the robustness of our findings (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007; Yin, 2017). Whereas case study research does not allow for an empirical generalization in probabilistic or deterministic terms, our findings shall be understood as ideas that provide reasonable expectations of similar findings in other cases in the hospitality sector (Bengtsson and Hertting, 2014; Lincoln and Guba, 2000) and that can be validated or falsified by future quantitative research.

3.2. Sample

Using purposive (Guest et al., 2006; Morse et al., 2002) or theoretical sampling (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007), we selected six hospitality firms from Austria (see Table 1 ) that were strongly affected by the COVID-19 crisis, but showed signs of recovery and were therefore likely to show BMI (Patton, 2014). Austria is a country with a well-established hospitality industry, counting 1527 million overnight stays in 2019, and ranking 5th out of 29 European tourism regions (WKO, 2020). Approximately one-sixth of the country's workforce is employed in this sector that contributes 15.3% of the country's GDP.

Table 1.

Overview of the investigated cases.

| Case | Type | Data Source | Family firm | Seasonal business | Number of employees | Year of foundation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Restaurant | 2 Interviews Homepage Review platforms Social media | yes 1 st generation | no | 30 | 2019 |

| B | Restaurant | 2 Interviews Homepage Review platforms | yes 1 st generation | no | 6 | 2019 |

| C | Restaurant | 2 Interviews Homepage Review platforms | yes 1 st generation | no | 6 | 2019 |

| D | Bar | 2 Interviews Homepage Social media | no | no | 10 | 2011 |

| E | Bar | 2 Interviews Homepage Review platforms Social media | yes 1 st generation | no | 4 | 2010 |

| F | Hotel | 2 Interviews Homepage Review platforms Social media | yes 3rd generation | no | 12 | 1953 |

For the sample, we also included a hotel apart from a homogenous group of restaurants and bars that depend on daily guests to be able to search for both similarities and contrasts among the cases and therefore to enhance the robustness of the findings (Guest et al., 2006). For the same reason, we selected cases with different firm ages as these might affect the way management copes with the crisis. Thus the restaurants and bars also differ regarding number of employees, number of seats, kinds of offered foods or beverages, etc. We stopped data collection after saturation was reached (Eisenhardt, 1989; Morse et al., 2002).

3.3. Data collection

For each hospitality firm in our sample, we conducted two interviews: one with the owner or managing director and one with a stammgast, in May and June 2020. The semi-structured interview format allowed us to adjust our questions to the respondents' statements (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007). With the interviewees' consent, the interviews were recorded. We triangulated the data with publicly available information (Yin, 2017) from the firms' websites and review platforms such as TripAdvisor and social media.

3.4. Data analysis

After transcribing the interviews, we independently read the transcripts and openly coded the interview and archival data (Miles et al., 2014; Corbin and Strauss, 2014) in a within-case analysis, followed by a cross-case analysis (Eisenhardt, 1989). In the coding process, we iterated between theory and data. In the cross-case analysis, we compared and contrasted the cases and looked for common themes which could be verified in interactive loops (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007), to get an in-depth understanding and find insights that are potentially generalizable (Miles et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2017). Reliability and validity of our findings were assured by multiple cases, independent coding, and iterative joint data consolidation (Kirk et al., 1986; Morse et al., 2002; Sousa, 2014).

3.5. Case descriptions

3.5.1. Background information

The Austrian hospitality industry was affected by the COVID-19 crisis like hardly any other industry. Due to the wide variety of country-specific measures and regular legal adjustments, transparency about the situation was of great importance during data collection. While the interviews were conducted with the firms, all borders with neighboring countries were still closed. Restaurants and bars were allowed to open up again from May 15, 2020, hotels only from May 29. The staff had to wear masks or face visors. Also, guests had to wear a mask when entering a facility. Guests were allowed to sit at the table with a maximum of four people, and a minimum distance between the tables was imposed. The closing time was legally set at 23:00.

3.5.2. Case A – Restaurant

Case A is a restaurant with a long tradition starting in the 18th century. After several changes, in 2019, the restaurant became a family firm in first generation, and the new tenant continued to run the restaurant under the existing brand, employing 30 employees. The restaurant is an annual operation and not a seasonal business, but due to the additional garden seats and the tourist attraction in summer, the restaurant makes its principal turnover in summer. During summer, 400 seats are available, mainly in the large garden.

Currently, two family members work in the firm and split the management tasks. Both have many years of industry experience and had already run a restaurant before. The restaurant benefits from the excellent reputation of the brand. It is characterized by low fluctuation despite the change of tenant and the takeover of the team. However, ideas generally come from the management team and not from employees. The managers try as often as possible to serve the customers directly and therefore have numerous stammgasts.

3.5.3. Case B – Restaurant

Case B is a family-owned restaurant in the first generation which offers 109 seats and employs six employees. In 2019, tenants changed, but the new tenants continued to run the restaurant under the same brand. The firm started its operations in January 2020 and only had a short time to establish itself before the COVID-19 crisis led to a national lockdown. The restaurant is not a seasonal business, but due to the garden, most of the sales are generated in summer.

Currently, only one family member is employed full-time as manager and chef. This person already has extensive industry experience. The firm has taken over many stammgasts from its predecessor, who focused on the neighboring countries. As a result of the border closures, many stammgasts were unable to enter the restaurant during the reopening.

3.5.4. Case C – Restaurant

Case C is a restaurant that has been run as an inn since 1864. The current owner has rented the building for the last 30 years, and after the last change of tenant in 2019 decided to build the restaurant himself as a family firm. The restaurant has six employees and a total of 106 seats. Due to a small garden, the building offers more seats in summer but is not a seasonal business.

Since October 2019, the family firm has been managed by an experienced external managing director. There are currently no family members in the firm, but they are in training in other restaurants and are planning to take over the family firm in the long run. Although the firm has only been run as a family firm for a short time, numerous stammgasts have already been won over.

3.5.5. Case D – Bar

Case D is a bar that is mainly attracting a local audience. The firm is not a family firm but is run by two partners with many years of experience in the business. The first shareholder took over the firm in 2011 under the existing brand. The second shareholder joined the firm in 2018. The firm has a total of 10 employees, only four of whom work full-time, and offers inside space for up to 200 guests (no garden/terrace).

Individual stammgasts have been visiting the bar regularly for over ten years. The implementation of the non-smoking law in Austria in autumn 2019 has led to minor structural changes and has caused the firm several problems as smokers must leave the premises. This, in turn has led to problems with residents. The regular opening hours of the bar are from 19:00 to 03:00 in the morning, and the bar is well attended, especially on weekends. The main rush of customers is between 22:00 and 02:00.

3.5.6. Case E – Bar

Case E is a bar that exists since 2010 and has four full-time employees. The managing director is 70 years old and experienced in the hospitality industry. The firm is a family firm in the first generation, and in addition to the managing director, her husband also works in the firm. Due to problems with neighbors related to noise, the firm had to move to a new facility in 2016. This move was associated with high costs. The premises do not have a garden, so the firm was affected by renewed building measures after the introduction of the non-smoking law in Austria. The law resulted in numerous noise nuisances and fewer customers. The bar is generally open from 19:00 to 05:00 and is particularly well frequented on weekends. Because of the longer opening hours than most local bars, the firm is visited by guests mainly between 02:00 and 05:00.

3.5.7. Case F – Hotel

Case F is a family-owned hotel, established in 1953 and now managed in the third generation. The managing director was integrated into the firm from the very beginning and had much experience. The firm currently has 12 employees, including three family members. The hotel has 80 beds at full capacity and is not a seasonal business, but most turnover is generated during the summer months, as the region is popular with tourists during this time due to cultural events. Outside this time, the most frequent guests are representatives in transit and guests of regional firms. The family runs an associated restaurant in the hotel, but this only generates a small share of the total turnover.

4. Findings

4.1. Within-case analysis

The following analysis provides an insight into the individual cases. Table 2 provides an overview of the main components of the cases.

Table 2.

Within-case analysis overview.

| BMI | Furlough | Dismissals | Rent | Most important measure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case A | conducted | yes | no | Sales-related | Furlough |

| Case B | no | yes | no | Sales-related | Furlough |

| Case C | considered | yes | no | Owns building | Furlough |

| Case D | conducted | yes | no | Sales-related | Furlough |

| Case E | conducted | yes | no | suspended/ not finally clarified | Furlough |

| Case F | considered | yes | yes (1) | Owns building | Furlough |

4.1.1. Case A

Case A was severely affected by the crisis and completely discontinued its primary BM. The firm put all employees on furlough but did not have to lay anyone off. Besides, the management pursued a strong cost-cutting policy and was able to suspend the rent during the lockdown and pay the rent based on turnover for at least the first two months after reopening.

During the crisis, the firm engaged in BMI. The idea came from the entrepreneur and was implemented at short notice. Instead of the regular restaurant business, various theme boxes (boxes with pre-selected ingredients to cook at home) were put together, which were then purchased and picked up by customers. These boxes were advertised primarily via personal networks, social media and a regional newspaper. The managing director plans to expand and further develop this model.

The firm has also clearly benefited from its stammgasts during the crisis, although they did not contribute any ideas to the BMI. The stammgasts, however, were the buyers of the new service and also supported the firm by purchasing vouchers. They also provided psychological support for the owner. After reopening, it was mainly stammgasts who were responsible for the turnover. Until the opening of the border, stammgasts were responsible for over 40% of earnings after the crisis and also contributed to promoting the firm in this phase through their social media activities.

4.1.2. Case B

The firm did not begin operating until shortly before the crisis, but was already popular and well attended. During the crisis, the business was shut down, and no revenues were generated. The employees were all put on furlough, and the rent was immediately waived. Government support and furlough were the most important measures to survive the crisis.

During the crisis, the business used the time mainly to do small repairs and cleaning. No new BM was developed, the time was merely bridged. At the end of the lockdown, the firm started to sell vouchers to improve liquidity.

Stammgasts were of psychological importance to the firm and helped to get through the crisis. After the crisis, they will be of great importance as visiting the restaurant repeatedly. One of the main problems is that many stammgasts come from neighboring countries, and, at the time of the interview, were not yet allowed to travel.

4.1.3. Case C

The firm had already closed before the official lockdown due to a vacation closedown; afterwards, the employees were registered for furlough, no employees had to be dismissed. As the family firm owns the building, no negotiations regarding the rent were necessary. Furlough was mentioned as the most important measure. In addition to the government measures, a fixed cost subsidy, the depreciation of spoiled goods, the reduction of the VAT on non-alcoholic beverages, and a regional tourism promotion also helped the business.

Although the firm briefly considered establishing a pick-up or delivery service, the management and the owners decided against it. The adjustments were considered too large, and it was assumed that this BM could not be implemented in a sustainable manner and would, therefore, only be used for marketing purposes.

However, stammgasts were vital for the business. They generated liquidity by purchasing vouchers, but mostly showed psychological support and regularly asked for the manager's well-being. After the crisis, they helped to get the firm going again, primarily through frequent visits and the introduction of ideas.

4.1.4. Case D

The firm followed government regulations and shut down completely. To be able to survive the situation in the best possible way, costs were minimized. In addition to furlough and government support, the management negotiated a suspension of the rent and a turnover-related rent for the first six months after the reopening. This measure and furlough were the most important criteria for surviving the crisis. In the course of the reopening, it is mainly the opening hours that cause problems for the firm.

The firm was already implementing BMI before the crisis. The aim was to develop a flexible bar in a trailer to offer cocktail catering on birthdays and weddings. Due to the crisis, this BM was implemented more quickly and adapted again. The firm has a fixed location, in an open-air swimming pool, to be able to generate turnover during the day and to have the personnel resources free for the actual business in the evening. In addition to this innovation, there was another BM change. Since the firm did not have garden areas available, they agreed with the city to set up a cocktail stand in a gastronomically undeveloped area on weekends.

In hardly any other example did the stammgasts show such a strong connection to the firm. The stammgasts joined forces and offered the firm, next to psychological support, financing to help survive the crisis. However, the offer became unnecessary due to state support. The firm refrained from selling vouchers during the crisis but benefited from the consumption of stammgasts in the first few weeks after the crisis, as they accounted for most of the firm's turnover.

4.1.5. Case E

The firm faced numerous problems during the crisis and shortly after the lockdown. Expenses could be reduced through furloughs, but the rent could only be postponed. Due to the problems that occurred when starting out and implementing the non-smoking law, the financial situation was already tense. Customer demand, however, is high, especially at off-peak times, which makes the early curfew another problem.

The firm saw a way out in adjusting its BM and rented additional open space. This space is now used to generate sales during a period when the actual bar is closed. The changes in the BM are small, but help the firm to generate revenue and stay liquid.

During the crisis, the managing director was in contact with stammgasts, this psychological factor helped especially as she belongs to the risk group for the virus. From a financial point of view, however, the firm did not try to approach its stammgasts. Stammgasts greatly helped the business after the reopening by actively sharing social media contributions to support.

4.1.6. Case F

This hotel business was severely affected by the lockdown and, compared to the restaurants, was only allowed to reopen later. Since the hotel guests are the most important customers for the own restaurant, the firm decided not to open the restaurant early. During the lockdown, costs were reduced, employees were sent on furlough, and one employee in the probationary period was dismissed. Since the property belongs to the firm, rent was no issue. Banks were contacted for potential credit lines.

The management thought briefly about starting a new BM to keep the restaurant business running. Due to the organizational effort and potential bad reputation they decided against this. The business is known for its high quality food and assumed that this standard could not be maintained with delivery.

Stammgasts were relevant for the firm mainly concerning liquidity. Three stammgasts offered to continue to make the regular direct debits, and use these amounts in the future. Apart from this component, no psychological support for the stammgasts was felt at this firm.

4.2. Cross-case analysis

The analysis shows that the firms have a very similar understanding and approach to the crisis. Only the hotel (Case F) differs in some respects, mainly due to specifications of the accommodation industry, which predominantly refer to the significantly higher unit costs for consumption. Table 3 provides an overview of the main results of the cross-case analysis. We did not find an impact of the firm age on how to cope with the crisis.

Table 3.

Cross-case overview of essential factors.

| Case A | Case B | Case C | Case D | Case E | Case F | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engaged in BMI | Change in Value Creation | yes | – | – | no | no | – | |

| Change in Value Proposition | yes | – | – | yes | yes | – | ||

| Change in Value Capture | no | – | – | no | no | – | ||

| Scope and novelty of BMI | focused BMI | – | – | evolutionary BMI | evolutionary BMI | – | ||

| Status of BMI | conducted | no | considered | conducted | conducted | considered | ||

| Influencing factors | Stammgast | Financial support | x | – | x | x | – | x |

| Psychological support | x | x | – | x | x | – | ||

| Marketing channel | x | – | x | x | x | – | ||

| Idea generator | – | – | x | – | – | – | ||

| Governmental support | Furlough | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Decrease of VAT on non alc. drinks | x | – | x | x | – | – | ||

| Bridging loan | – | – | x | – | – | x | ||

| Hardship funds | – | – | x | x | x | – | ||

| Takeover of fixed costs | – | – | x | – | – | – | ||

| Further support | Reduction or deferment of rent | x | x | owns building | x | x | owns building | |

4.2.1. Importance of BMI to overcome the crisis

Three firms (Case A, D, and E) established a BMI as a result of the crisis. In all three cases, the BMs were fundamentally new for the firm, but for two cases already established in the industry (Case D, and E). In two firms (Case A and D), the idea for innovation was already present before the crisis, and was adapted or implemented as planned due to time and financial pressure.

The results show that the crisis in one firm (Case A) has significantly changed its value creation. The firm no longer offers the value of a classic restaurant but establishes prepared food or gift baskets for at home. For the value proposition, there were changes in all three cases (Case A, D, and E). On the one hand, new points of sales are being used, and on the other hand, the customer base is changing significantly. As there was a significant change in the value proposition in Case A, the value capture also had to be adjusted. The BMIs are mainly evolutionary BMIs for Cases D and E but also a focused innovation for Case A.

4.2.2. Enhancers and inhibitors in BMI of hospitality firms

The main reasons for initiating BMI are related to the firms’ respective situations but can be narrowed down to the topics of financial pressure, responsibility, and available time. The results show that available time capacities are not automatically sufficient to start a BMI, as all firms had those capacities available, but only three of them innovated their BM. However, the combination of free capacities and financial pressure as well as great responsibility, has led to a BMI (Case A, D, and E). Firm A has a special responsibility due to its size. However, only with the free capacities, the BMI could be realized. In the case of firms D and E, it is striking that even after the end of the lockdown, both would still hardly make any sales due to their situation (no garden areas and closing time at 23:00). As a result, the financial pressure on the firms became greater, and they had to come up with new ideas.

Although only three firms have responded to the crisis with a BMI, two other firms (Case C and F) have also looked into it and developed ideas, without eventually pursuing them due to their marginal financial value. Both these firms own their premises and thus have the advantage to not have to pay rent. Other firms, which have been involved in BMI, are dependent on the goodwill of the lessor for their rent payments.

Besides the cost reduction through rent savings, all investigated firms praised the state support. Extensive government programs have allowed firms to reduce their personnel costs and ensure liquidity, which has eased the pressure to implement innovative ideas.

For all firms, furlough was the most important factor in surviving the crisis. In addition, a regional tourism promotion scheme was highlighted because of its unbureaucratic payment (Case C and E). Other government measures included the reduction of VAT on non-alcoholic beverages, the distribution of bridging loans, the entrepreneur hardship fund, and the assumption of fixed costs. In general, the entrepreneurs mainly mentioned state measures.

4.2.3. Stammgasts’ role during crisis in the hospitality industry

Extant literature suggests that guests play a significant role in the generation of new ideas in firms (Kallmuenzer, 2018). Our results also show the great importance of stammgasts for the firms’ survival of the crisis.

Table 4 highlights the components of a definition in the eyes of the interviewees. Apart from the factor that stammgasts are returning guests (Cases A, B, C, D, E, and F), the emotional bond between guest and owner is of extraordinary importance for stammgasts (Cases A, B, C, D, and E). "To me, stammgasts are more than just frequent visitors. They are like friends and or family." (Case D).

Table 4.

Components used in the definition of a stammgast and their frequency.

| Component | Number of nominations | Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Frequent returning guest | 6 | A, B, C, D, E, F |

| Personal level | 4 | A, B, C, D, E |

| Special reference to the host | 4 | A, B, C, D, E |

| Emotional relation to employees | 3 | A, B, E |

| Friend | 3 | A, B, D |

| Interacts with social media | 3 | A, D, E |

| Word of Mouth | 3 | A, C, D |

| Almost like family | 2 | A, D |

| Brings new guests | 1 | C |

| Offers support if needed | 1 | D |

Therefore, we define a stammgast as “a person who is a not only a frequent returning guest of a hospitality firm but is also connected on an emotional and personal level to the owner and the staff.” Only the statements of the hotel (Case F) were not entirely in line with these results as the definition of a stammgast was purely reduced to the number of hotel stays.

For all investigated firms, stammgasts played an essential role during the general lockdown. The psychological component was of utmost importance (Cases A, B, C, D, and E). The stammgasts repeatedly contacted the entrepreneurs, asked about their current situation and thus provided psychological support. Through this support, the entrepreneurs felt encouraged to implement their ideas and thus carry out BMI. Stammgasts also contributed to overcoming liquidity bottlenecks and, as early adopters, took advantage of new services offered (Cases A, B, D, and F). Moreover, in two cases, stammgasts offered additional financial support to the firms. In Case D, a group of stammgasts joined together offering to finance the firm through the crisis. The managing director (Case D) explained: “We knew from the outset that we could run out of money during the lockdown. Our stammgasts noticed that too. We were then offered money saved by several stammgasts to help finance our business.” In Case F, several stammgasts offered the hotel to carry out the regular debits even without providing the service to secure the firm's liquidity: “Some of our stammgasts at the hotel said we should just charge them for the months, they would definitely come and spend it one way or another.”

Even in the course of the reopening, stammgasts were of great importance. Especially on the opening days, they established themselves as revenue generators. The only exception is the hotel (Case F), which had only few customers due to closed borders. The other firms emphasized the role of stammgasts due to their loyalty and the revenue they generate (Case A, B, C, D, and E). The managing director of Case A states: “We are very happy about our stammgasts. They currently account for about 40% of our revenue.” In addition, stammgasts also have played a role as brand ambassadors and as a marketing channel. Both in conversation and when looking at the firms' social media sites, it can be seen that the stammgasts interact with the firms' posts and spread them among their friends (Case A, B, C, D, and E).

Finally, stammgasts were also a source of ideas. In Case C, in particular, they came up with numerous ideas to increase the capacity utilization of the restaurant during the reopening phase. They were also actively involved in the implementation and offered their own premises and contacts for advertising purposes.

5. Discussion and conclusion

5.1. Key findings

The present study shows that BMI is a useful strategy for hospitality firms to overcome and restart after a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic. We find that the identified BMIs are rather small incremental changes that can be implemented quickly (Foss and Saebi, 2017). We highlight the driving factors for a BMI, namely available time, overall pressure to change because of the crisis, and the important role of stammgasts during BMI. The state-ordered closure and the associated reduction of operational tasks freed up time resources in the firms, especially for decision-makers. These resources can now be invested in strategic developments instead of operational activities.

In addition to the free resources, general pressure has also emerged as an essential criterion. Firms that receive less support (from landlords or the state), are threatened by longer lockdowns (nightclubs, bars) and are responsible for many employees, react more proactively than others in their BMI. Stammgasts provide psychological safety, which supports and induces hosts to innovate their BM. In addition, the personal relationship ensures that stammgasts support and contribute to BMI throughout the process as partners in the implementation, early users and therefore providers of feedback.

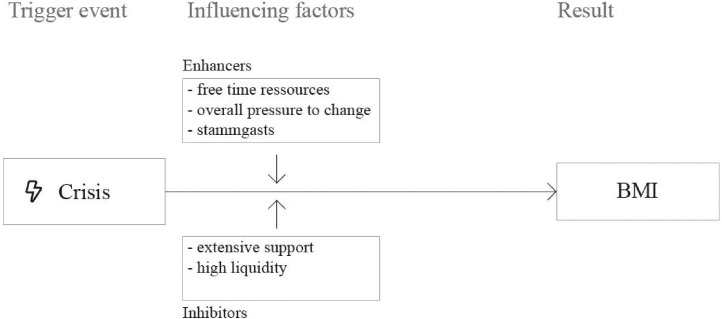

Based on these results, we propose the crisis – BMI relationship model for the hospitality industry (Fig. 1 ). The model comprises the results and shows that a crisis can be a trigger event (Sigala, 2020) to start BMI in the hospitality industry, which can help firms that are shut down to create new BM and open up again. The lockdown of the COVID-19 crisis led to the total loss of income streams and thus to a particular pressure on firms to innovate. Enhancing factors such as stammgasts’ psychological support, free time, and financial pressure create a need to change and further support a BMI. However, in the course of a crisis, comprehensive support packages are also put together by governments, which cause firms not to adjust their BM if liquidity is already secured.

Fig. 1.

Crisis - BMI relationship model under the influencing factors of the hospitality industry.

5.2. Theoretical contributions

This study contributes to the discourse on crisis management in the hospitality industry, which has so far been mainly addressed for the context of terrorism, but also for natural disasters and financial crises (Anson, 1999; Butler and Baum, 1999). Literature shows that, above all, government support and targeted advertising of local populations help to overcome a crisis (Mansfeld, 1999). Our findings confirm these particular effects also for the COVID-19 crisis. However, the results of this study extend previous knowledge by showing that BMI can be another potential solution to overcome a crisis in the hospitality industry.

This general finding is in line with recent evidence provided by Kraus et al. (2020) in a cross-industry setting from different European countries as well as with initial evidence that has shown that BMI is a relevant approach for hospitality family firms in increasing their innovation capability (Souto, 2015). We support the importance of BMI but also show that the role of BMI might be even more strategically relevant in a crisis context. While individual firms adapt BMs only temporarily to maintain liquidity, we find that BMI ― initiated as a response to a crisis ― can also have long-term implications. Put differently, a crisis can result in new perspectives and profit potentials for firms that seize the opportunity of change.

In this context, our study also dealt with the antecedents of BMI during the crisis. One particular focus was on the stammgasts, as literature sees guests as a source of innovation in the hospitality industry. Contrary to the suggestions in the literature (e.g., Kallmuenzer, 2018; Pynnönen et al., 2012), our study could not identify them as a principal trigger/idea generator and thus contributors to open innovation, but rather primarily as a facilitator of BMI. This may be explained by the nature of the given innovation context. Usually, customers become innovators as they want to improve their own situation and have the opportunity to provide critical feedback. The rigid lockdown, however, changed this context, as the measures for social distance also create distance for the exchange of ideas. Nonetheless, open innovation is still also little known in the hospitality sector and processes and foundations for open innovation are only gradually being created (Iglesias-Sánchez et al., 2020). A lack of structures in combination with the lockdown situation where communication between external stakeholders and decision-makers was limited apparently lead to a lack of pen innovation and thus also indicates that missing foundations during a crisis can have significant consequences. However, our study unveils a different and potentially even more important role of the stammgasts during the crisis ― namely their psychological support, especially in the implementation and establishment of a BMI, where they helped the firms to get over a first shock and motivated decision-makers to work creatively.

Above all, changes in the environment play a significant role (Foss and Saebi, 2017), and perceived threats were an important antecedence of BMI (Saebi et al., 2017). Our study supports these findings for the hospitality industry as the COVID-19 pandemic also represents a turbulent environment that significantly threatens the firm.

The crisis, as such, is a trigger for the general BMI, but not necessarily sufficient. A range of influencing factors is responsible for the final decision to implement a BMI. While the literature generally states that financial resources are a key driver for innovation in tourism (Kallmuenzer et al., 2019), in the specific context of this study, extensive financial resources only ensure that firms get through the time of crisis and continue to work without change. This finding may be explained as the threat (see Saebi et al., 2017) that is induced by the crisis is reduced, and therefore the pressure to alter the BM is much smaller. This persevering strategy helps the hospitality firms to survive the crisis (Wenzel et al., 2020), but its long-term development remains open as global crises, in particular, cause not only business but also social changes (Clark et al., 2020).

On the other hand, there are supporting factors that favor BMI. Kraus et al. (2020) found that lower operative utilization creates more available time and slack resources for strategic considerations. In particular, small and medium-sized enterprises that do not have dedicated capacities in strategy development can benefit from this (Legohérel et al., 2004). Furthermore, while extensive financial support inhibits BMI, financial pressure can lead a firm to engage in it. Eggers (2020) states that small and medium-sized enterprises, which usually have less financial resources available, come under even higher pressure during a crisis. But it is precisely this financial pressure that leads these firm to question the existing and develop a new BM.

5.3. Implications for practice

This study allows for first recommendations to firms concerning the role of BMI in the hospitality industry and in the survival and recovery from a crisis. Measures for social distancing lead to fatal consequences in the hospitality sector, such as blocking open innovation. A BMI cannot only help firms to generate revenues during the crisis but also contribute to a sustainable preparation of the firm for the future. Hospitality entrepreneurs should, therefore, actively and continuously develop and adapt their BM.

Especially through digitalization of the BM additional services can be offered, which can also be called up during the crisis and overcome the distance barriers imposed by the lockdown measures during COVID-19 (e.g., Clark et al., 2020). In the upcoming phase, firms should make the best possible use of this potential of digitalization in order to be prepared for future crises. Kraus et al. (2020) already showed that temporary changes in BMs are a useful strategy to overcome a crisis and prepare for the future.

In addition to digitalization, firms must actively reduce the effects of inhibiting factors and promote enhancing factors, such as communication with stammgasts and creating time slots for strategic considerations. This preparation does not only allow for a successful BMI, but also for open innovation (Iglesias-Sánchez et al., 2020). Findings from this study also show that open innovation would enable personal relationships and active communication with customers that can have enormous potential, especially during times of crisis.

Recommendations for regions can also be derived from the results. Destination managers should encourage and connect firms to innovate despite or even during good financial times. Innovation relates not only to products and services but also to BMs. BMI can be anchored in firms through training and cooperation with innovation and creativity trainers. These meetings then also lead to strong networking effects within the industry, which improves the exchange of ideas and innovations (Beritelli, 2011; Kallmuenzer, 2018) that can help to develop stronger resilience and recovery potential from future crises.

5.4. Limitations and future research opportunities

This study is subject to limitations due to its methodology and the crisis situation. It is a first investigation on the relationship of BMI during a crisis in the hospitality industry. However, the purposive sampling of firms that were investigated is a general limitation of the method used. As BMI is a growing research field its effects on the hospitality industry should further be investigated. This paper can be seen as a foundation for further research.

The identified inhibiting and enhancing factors should be investigated in further quantitative approaches to check their robustness. Furthermore, our findings are particularly grounded on cases of restaurants, bars, and a hotel in Austria. Future research should extent both the scope of types of hospitality firms and the cultural context to further explore the phenomenon and add to the validity of findings.

The unique setting of the COVID-19 crisis is another limitation of this study: Since this crisis is described as unprecedented and special in its scope, the comparability with other crises is impaired. Closed borders were not known to Central Europe in the past decades, and has led to a special situation. By testing our results in the course of other crises and contexts, this limitation could be mitigated.

Acknowledgements

Montpellier Business School (MBS) is a founding member of the public research center Montpellier Research in Management, MRM (EA 4557, Univ. Montpellier). Johanna Gast is member of the LabEx Entrepreneurship (University of Montpellier, France), funded by the French government (Labex Entreprendre, ANR-10-Labex-11-01). This work was supported by the Open Access Publishing Fund provided by the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano.

Footnotes

We decided to use the German word, as it covers more than its English translation “regular patron”. A stammgast is not only a regular, but also a very frequent guest who is well-known by name (often even by first name, which is otherwise unusual in German-speaking countries where people usually address each other only by first name when they are friends) to the staff, where the staff often even services the stammgast with his regular dish without asking, and who can overall be considered as an “extended inventory” of the place.

References

- Achtenhagen L., Melin L., Naldi L. Dynamics of business models–strategizing, critical capabilities and activities for sustained value creation. Long Range Plann. 2013;46:427–442. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2013.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amit R., Zott C. IESE Business School of Navarra; Barcelona: 2010. Business Model Innovation: Creating Value in Times of Change. IESE Working Paper, No. WP-870. [Google Scholar]

- AMS . 2020. Derzeit Über 140.000 Menschen in Tirol in Kurzarbeit Oder Ohne Job. pp. Retrieved from: https://www.ams.at/regionen/tirol/news/2020/2005/derzeit-ueber-2140-2000-menschen-in-tirol-in-kurzarbeit-oder-ohne-#tirol. 25.09.2020. [Google Scholar]

- Anson C. Planning for peace: the role of tourism in the aftermath of violence. J. Travel. Res. 1999;38:57–61. doi: 10.1177/004728759903800112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aspara J., Hietanen J., Tikkanen H. Business model innovation vs replication: financial performance implications of strategic emphases. J. Strateg. Mark. 2010;18:39–56. doi: 10.1080/09652540903511290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baggio R. Collaboration and cooperation in a tourism destination: a network science approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011;14:183–189. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2010.531118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal P., Corley K. American Society of Nephrology Briarcliff Manor; NY: 2012. Publishing in AMJ—Part 7: What’s Different About Qualitative Research? [Google Scholar]

- Baum T., Hai N.T.T. Hospitality, tourism, human rights and the impact of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2020;32:2397–2407. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-03-2020-0242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson B., Hertting N. Generalization by mechanism: thin rationality and ideal-type analysis in case study research. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2014;44:707–732. doi: 10.1177/0048393113506495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beritelli P. Cooperation among prominent actors in a tourist destination. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011;38:607–629. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2010.11.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs D., Hall C.M., Stoeckl N. The resilience of formal and informal tourism enterprises to disasters: Reef tourism in Phuket, Thailand. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012;20:645–665. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.630080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Binkhorst E., Den Dekker T. Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. J. Hosp. Mark. Manage. 2009;18:311–327. doi: 10.1080/19368620802594193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bogers M., Jensen J.D. Open for business? An integrative framework and empirical assessment for business model innovation in the gastronomic sector. Br. Food J. 2017;119:2325–2339. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-07-2017-0394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton R., Hannon M. Governing sustainability transitions through business model innovation: towards a systems understanding. Res. Policy. 2016;45:1731–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2016.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brand M., Tiberius V., Bican P.M., Brem A. Agility as an innovation driver: towards an agile front end of innovation framework. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019:1–31. doi: 10.1007/s11846-019-00373-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler R.W., Baum T. The tourism potential of the peace dividend. J. Travel. Res. 1999;38:24–29. doi: 10.1177/004728759903800106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah S., Ho Y.-P., Li S. Business model innovation for sustainable performance in retail and hospitality industries. Sustainability. 2018;10:3952. doi: 10.3390/su10113952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.C., Elston J.A. Entrepreneurial motives and characteristics: an analysis of small restaurant owners. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013;35:294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough H. Business model innovation: it’s not just about technology anymore. Strategy Leadersh. 2007;35:12–17. doi: 10.1108/10878570710833714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough H. Business model innovation: opportunities and barriers. Long Range Plann. 2010;43:354–363. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough H. To recover faster from Covid-19, open up: managerial implications from an open innovation perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough H., Bogers M. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2014. Explicating Open Innovation: Clarifying an Emerging Paradigm for Understanding Innovation. New Frontiers in Open Innovation; pp. 3–28. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Clark C., Davila A., Regis M., Kraus S. Predictors of COVID-19 voluntary compliance behaviors: an international investigation. Global Transitions. 2020:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.glt.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss T. Measuring business model innovation: conceptualization, scale development and proof of performance. R&D Management. 2017;47:385–403. doi: 10.1111/radm.12186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss T., Kesting T., Naskrent J. A rolling stone gathers no moss: the effect of customers’ perceived business model innovativeness on customer value co-creation behavior and customer satisfaction in the service sector. R D Manag. 2018 doi: 10.1111/radm.12318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss T., Abebe M., Tangpong C., Hock M. Strategic agility, business model innovation, and firm performance: an empirical investigation. Ieee Trans. Eng. Manag. 2019:1–18. doi: 10.1109/TEM.2019.2910381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J., Strauss A. Sage publications; 2014. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Cucculelli M., Bettinelli C. Business models, intangibles and firm performance: evidence on corporate entrepreneurship from Italian manufacturing SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2015;45:329–350. doi: 10.1007/s11187-015-9631-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Reuver M., Bouwman H., Haaker T. Business model roadmapping: a practical approach to come from an existing to a desired business model. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2013;17 doi: 10.1142/S1363919613400069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- del Mar Alonso-Almeida M., Bremser K. Strategic responses of the Spanish hospitality sector to the financial crisis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013;32:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demil B., Lecocq X. Business model evolution: in search of dynamic consistency. Long Range Plann. 2010;43:227–246. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2010.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebel P.A., Bretschneider U., Leimeister J.M. Can the crowd do the job? Exploring the effects of integrating customers into a company’s business model innovation. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2016;20 doi: 10.1142/s1363919616500717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers F. Masters of disasters? Challenges and opportunities for SMEs in times of crisis. J. Bus. Res. 2020;116:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989;14:532–550. doi: 10.2307/258557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt K.M., Graebner M.E. Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007;50:25–32. doi: 10.5465/amj.2007.24160888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foss N.J., Saebi T. Fifteen Years of Research on Business Model Innovation: How far have we come, and where should we go? J. Manage. 2017;43:200–227. doi: 10.1177/0149206316675927. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschelli M.V., Santoro G., Candelo E. Business model innovation for sustainability: a food start-up case study. Br. Food J. 2018;120:2483–2494. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-01-2018-0049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi A., Cavallo A. Agile business model innovation in digital entrepreneurship: lean startup approaches. J. Bus. Res. 2020;110:519–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.06.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giesen E., Riddleberger E., Christner R., Bell R. When and how to innovate your business model. Strategy Leadersh. 2010;38:17–26. doi: 10.1108/10878571011059700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grissemann U.S., Stokburger-Sauer N.E. Customer co-creation of travel services: the role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tour. Manag. 2012;33:1483–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G., Bunce A., Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field methods. 2006;18:59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel G., Valikangas L. The quest for resilience. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004;81:52–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjalager A.-M. A review of innovation research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010;31:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hock-Doepgen M., Clauss T., Kraus S., Cheng C.-F. Knowledge management capabilities and organizational risk-taking for business model innovation in SMEs. J. Bus. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.12.001. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Sánchez P.P., López-Delgado P., Correia M.B., Jambrino-Maldonado C. How do external openness and R&D activity influence open innovation management and the potential contribution of social media in the tourism and hospitality industry? Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s40558-019-00165-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Israeli A.A., Reichel A. Hospitality crisis management practices: the Israeli case. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2003;22:353–372. doi: 10.1016/S0278-4319(03)00070-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.W., Christensen C.M., Kagermann H. Reinventing your business model. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008;86:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kallmuenzer A. Exploring drivers of innovation in hospitality family firms. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2018;30:1978–1995. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-04-2017-0242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kallmuenzer A., Peters M. Innovativeness and control mechanisms in tourism and hospitality family firms: a comparative study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018;70:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.10.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kallmuenzer A., Kraus S., Peters M., Steiner J., Cheng C.-F. Entrepreneurship in tourism firms: a mixed-methods analysis of performance driver configurations. Tour. Manag. 2019;74:319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2019.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk J., Miller M.L., Miller M.L. Sage; 1986. Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S., Clauss T., Breier M., Gast J., Zardini A., Tiberius V. The economics of COVID-19: initial empirical evidence on how family firms in five European countries cope with the corona crisis. Int. J. Entrepren. Behav. Res. 2020;26:1067–1092. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-04-2020-0214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Shin J., Park Y. The changing pattern of SME’s innovativeness through business model globalization. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2012;79:832–842. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2011.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Legohérel P., Callot P., Gallopel K., Peters M. Personality characteristics, attitude toward risk, and decisional orientation of the small business entrepreneur: a study of hospitality managers. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2004;28:109–120. doi: 10.1177/1096348003257330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y.S., Guba E.G. Case Study Method. 2000. The only generalization is: there is no generalization; pp. 27–44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfeld Y. Cycles of war, terror, and peace: determinants and management of crisis and recovery of the Israeli tourism industry. J. Travel. Res. 1999;38:30–36. doi: 10.1177/004728759903800107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Micheli M.R., Berchicci L., Jansen J.J.P. Leveraging diverse knowledge sources through proactive behaviour: how companies can use inter-organizational networks for business model innovation. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2020;29:198–208. doi: 10.1111/caim.12359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M.B., Huberman A.M., Saldaña J. 3rd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: a Methods Sourcebook. [Google Scholar]

- Morris M., Schindehutte M., Allen J. The entrepreneur’s business model: toward a unified perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2005;58:726–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J.M., Barrett M., Mayan M., Olson K., Spiers J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2002;1:13–22. doi: 10.1177/160940690200100202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okumus F., Altinay L., Chathoth P. Butterworth-Heinemann; Oxford: 2010. Strategic Management for Hospitality and Tourism. [Google Scholar]

- Paget E., Dimanche F., Mounet J.-P. A tourism innovation case: an actor-network approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010;37:828–847. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2010.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M.Q. Sage publications; 2014. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Pikkemaat B., Peters M. Towards the measurement of innovation - a pilot study in the small and medium sized tourism industry. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2006;6:89–112. doi: 10.1300/J162v06n03_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pikkemaat B., Peters M., Chan C.-S. Needs, drivers and barriers of innovation: the case of an alpine community-model destination. Tourism Manage. Perspect. 2018;25:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pohle G., Chapman M. IBM’s global CEO report 2006: business model innovation matters. Strategy Leadersh. 2006;34:34–40. doi: 10.1108/10878570610701531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pynnönen M., Hallikas J., Ritala P. Managing customer-driven business model innovation. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2012;16 doi: 10.1142/S1363919612003836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter T., Pedersen C.L. Analyzing the impact of the coronavirus crisis on business models. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020;88:214–224. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saebi T., Lien L., Foss N.J. What drives business model adaptation? The impact of opportunities, threats and strategic orientation. Long Range Plann. 2017;50:567–581. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2016.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S., Spieth P. Business model innovation: towards an integrated future research agenda. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2013;17 doi: 10.1142/S136391961340001X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sigala M. Tourism and COVID-19: impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa D. Validation in qualitative research: general aspects and specificities of the descriptive phenomenological method. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2014;11:211–227. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2013.853855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Souto J.E. Business model innovation and business concept innovation as the context of incremental innovation and radical innovation. Tour. Manag. 2015;51:142–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.05.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson B., Nordin S., Flagestad A. A governance perspective on destination development‐exploring partnerships, clusters and innovation systems. Tour. Rev. 2005;60:32–37. doi: 10.1108/eb058455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tajeddini K., Trueman M. Managing Swiss Hospitality: how cultural antecedents of innovation and customer-oriented value systems can influence performance in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012;31:1119–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teece D.J. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plann. 2010;43:172–194. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R., Wood E. Innovation in tourism: Re-conceptualising and measuring the absorptive capacity of the hotel sector. Tour. Manag. 2014;45:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2014.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Velu C. Evolutionary or revolutionary business model innovation through coopetition? The role of dominance in network markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016;53:124–135. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M., Stanske S., Lieberman M.B. Strategic responses to crisis. Strateg. Manage. J. 2020 doi: 10.1002/smj.3161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz B.W., Schilke O., Ullrich S. Strategic development of business models: implications of the Web 2.0 for creating value on the internet. Long Range Plann. 2010;43:272–290. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2010.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- WKO . 2020. Tourismus in Zahlen: Österreichische Und Internationale Tourismus- Und Wirtschaftsdaten. Retrieved from: https://www.wko.at/branchen/tourismus-freizeitwirtschaft/tourismus-freizeitwirtschaft-in-zahlen-2020.pdf. 29.09.2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Evans S., Vladimirova D., Rana P. Value uncaptured perspective for sustainable business model innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017;140:1794–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.07.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin R.K. Sage publications; 2017. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Zott C., Amit R. Business model design and the performance of entrepreneurial firms. Organ. Sci. 2007;18:181–199. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1060.0232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]