Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is considered one of the most significant global disasters in the last years. The rapid increase in infections, deaths, treatment, and the vaccination process has resulted in the excessive use of pharmaceuticals that have entered the environment as micropollutants. Considering the prior information about the presence of pharmaceuticals found in the wastewater of Cali, Colombia, which was collected from 2015 to 2022. The data monitored after the COVID-19 pandemic showed an increase in the concentration of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs of up to 91%. This increase was associated with the consumption of pharmaceuticals for mild symptoms, such as fever and pain. Moreover, the increase in concentration of pharmaceuticals poses a highly ecological threat, which was up to 14 times higher than that reported before of COVID-19 pandemic. These results showed that the COVID-19 had not only impacted human health but also had an effect on environmental health.

Keywords: Analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs, Colombia, COVID-19, Ecological threat, Hazard quotient

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Urban wastewater consists of a complex combination of contaminants, including micropollutants which are chemical substances with concentrations ranging from μgL−1 to ngL−1. Micropollutants and their presence in the water sources have become an environmental issue of global relevance. Pharmaceuticals are the most concerning micropollutants, as they can be excreted in their original form through urine and feces or as metabolites and are often resistant to degradation [1].

In Colombia, pharmaceutical compounds have been found in drinking water, surface water, and wastewater of cities, such as Bogotá, Medellín, and Cali [2, 3∗∗, 4]. Their presence is related to the self-medicating of people, and to the broad marketing of over-the-counter pharmaceuticals, particularly analgesics and anti-inflammatory compounds.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been one of the most concerning disasters in recent years. It placed the medical, scientific, and political circles on high alert due to the rapid increase in contagion and deaths. In Colombia, the first recorded case of COVID-19 was reported in March 2020, and subsequently, the number of positive cases quickly rose to an accumulated total of more than six million, resulting in almost 142,000 deaths up until November 2022 [5].

According to the World Health Organization, the most common symptoms of COVID-19 include fever, cough, tiredness, headache, and muscle aches, as well as in severe cases, shortness of breath. Therefore, symptom management requires the prescription of different pharmaceuticals, including antiviral, antibiotics, and analgesics/anti-inflammatory pharmaceuticals. Moreover, in Colombia, the vaccination process started in 2021, and around 71% of the population was vaccinated up until November 2022 [6]. Some mild symptoms were reported after vaccination, such as tiredness, myalgia, fever, headache, pain at the injection site, joint pain, nausea, and diarrhea [7, 8]. Some analgesics/anti-inflammatory pharmaceuticals are also recommended for the treatment of vaccination-related symptoms.

The increase in the presence of antiviral drugs and antibiotics has been reported by Morales-Paredes et al. [9], who stated that these compounds were detected in the water bodies at concentrations higher than 70% during the pandemic compared to previous years. In Colombia, only a few pharmaceutical compounds used to treat mild COVID-19 symptoms have been previously detected in urban wastewater, including paracetamol, ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac, and the antibiotic azithromycin all at average concentrations of up to 29.66, 2.72, 5.84, 0.34, and 3.99 μgL−1, respectively. However, there is no literature reporting data on the presence and concentration of these compounds during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Taking into account the impact of COVID-19 and the need for medication to treat both the disease and the mild symptoms associated with the vaccination, the aim of this paper is to analyze the changes in some pharmaceutical compounds present in Santiago de Cali’ wastewater, based on collected data, before and after the-COVID-19 pandemic, and evaluate their potential impact on aquatic biota using an ecological hazard methodology.

Geographical location

Data were collected from the effluent of the Santiago de Cali, Colombia, wastewater treatment plant (WWTP-C), which serves 82.7% of the population, equivalent to 1,847,773 people. The plant uses chemically enhanced primary treatment (CEPT) methods, including coagulation, flocculation, and sedimentation processes. The plant is located at the geographic coordinates 3°28′10.345″ N - 76°28′30.593″ W (refer to the location map in Figure S1 of the supplementary material).

Occurrence of pharmaceutical compounds

A combination of spot and composite samplings was conducted to obtain 42 samples in 2015, 2016, 2018, 2019, 2021, and 2022. The composite samples were taken at hourly intervals for 12 h. These samples were stored in amber-colored glass containers, refrigerated at 4 °C, filtered with 0.45 μm cellulose membranes, and analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC/MS-MS) to detect pharmaceutical compounds, following the methodology outlined by Jiménez-Bambague et al. [10]. The HPLC/MS-MS process is detailed in the supplementary material. A total of 21 pharmaceutical compounds were measured in the WWTP-C effluent. The sampling was arbitrarily alternated between rainy and dry periods, where no significant differences were identified, which is characteristic of Colombia's tropical climate.

The therapeutic groups evaluated were as follows: antiepileptics such as 10,11-Dihydro-10,11-dihydroxy carbamazepine (CBZ-Diol), carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, and primidone; hypolipidemic drugs such as bezafibrate, clofibric acid, etofibrate, fenofibrate, fenofibric acid, and gemfibrozil; analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs such as diclofenac, fenoprofen, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketoprofen, naproxen, and paracetamol; and tranquilizers such as diazepam, oxazepam, and pentoxyfilline. Lastly, the limit of quantification (LOQ) of the pharmaceutical compounds in HPLC/MS-MS was 0.050 μgL−1.

The effluent of the WWTP-C associated with CEPT was not designed to effectively remove these pharmaceutical compounds, leading to a low removal efficiency of less than 30% for the majority of these compounds [11]. Previous studies have shown that the coagulation-flocculation process has low efficiency for removing compounds, such as paracetamol, naproxen, ibuprofen, diclofenac, and carbamazepine [12, 13, 14]. Carballa et al. [13] found that the hydrophobic and acid properties of some compounds affect their fixation in the solid fraction, leading to a better removal of contaminants through the coagulation-flocculation process. However, most pharmaceuticals found in WWTP-C are hydrophilic or weakly hydrophobic. Moreover, although acidic pharmaceuticals (except carbamazepine) may interact better with the solids in the wastewater at acidic pH, their adsorption tends to decrease at neutral pH. This is because the negatively charged pharmaceuticals produce a repelling effect with the negatively charged solids in the wastewater, reducing the efficiency of the coagulation-flocculation process [14,15]. Therefore, the low removal efficiency of pharmaceutical compounds in WWTP-C can also be attributed to the circumneutral pH values (6.5 and 7.4) of its effluent, which is necessary to comply with regulations.

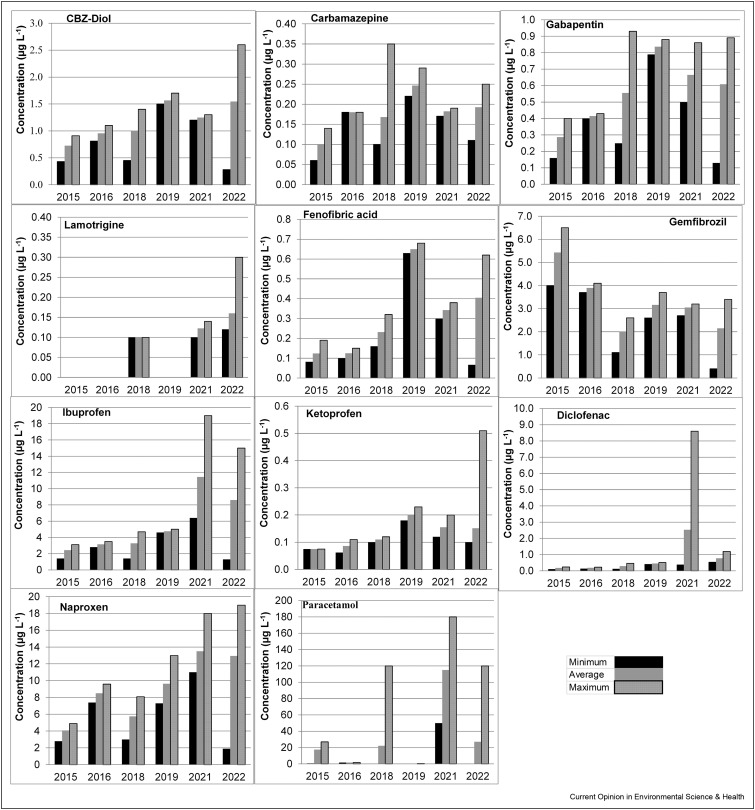

Eleven pharmaceutical compounds above LOQ have been detected since 2015, and these consist of four antiepileptics, including CBZ-Diol, carbamazepine, gabapentin, and lamotrigine; two hypolipidemic drugs including fenofibric acid (the active form of fenofibrate) and gemfibrozil; and five analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs including diclofenac, ibuprofen, ketoprofen, naproxen, and paracetamol. Figure 1 shows the pharmaceutical concentration for every year of the periods that were studied.

Figure 1.

Minimum, average, and maximum concentrations of pharmaceutical compounds.

The analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs were of the highest concentrations, and paracetamol was found to have the highest value of 180 μgL−1. Similarly, this therapeutic drug group showed a higher concentration increase in the post-COVID period than other compounds. These increases were 89%, 70%, 48%, and 91% for diclofenac, ibuprofen, naproxen, and paracetamol, respectively. This sharp increase in concentration could be attributed to these compounds being used to treat mild symptoms of COVID-19 and the effects of vaccination to prevent it [16]. In addition, according to Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos y Alimentos (INVIMA), they are over-the-counter pharmaceuticals, which means they are much more easily acquired in drugstores, supermarket chains, and small shops.

In another study, Galani et al. [17] found a drop in the consumption of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) of 27% and an increase of 198% in the consumption of paracetamol. These results were likely related to the common practice of doctors recommending the use of paracetamol instead of NSAIDs for treating COVID-19 symptoms. This is because NSAIDs have been found to increase the risk of respiratory tract infections [18]. NSAIDs include diclofenac, ibuprofen, naproxen, and ketoprofen. Paracetamol is not an NSAID because it is an analgesic and antipyretic, with limited anti-inflammatory effects.

Despite doctors advising patients to avoid using NSAIDs, their increase in Santiago de Cali's wastewater can be associated with users self-medicating, particularly in cases where users did not receive medical attention. It can also be attributed to the misinformation on social networks where incorrect medical advice is frequently given.

The COVID-19 pandemic is also the indirect cause of mental health problems, particularly because of isolation [19]. However, the results did not show a significant increase in antiepileptic drug and tranquilizer concentration. Only the antiepileptic drug lamotrigine had a concentration increase above LOQ and a greater detection frequency (8% in the pre-pandemic period vs. 94% between 2021 and 2022). According to Asadi-Pooya et al. [20], COVID-19 treatment in people with epilepsy may be complicated as antiepileptic drug doses often require adjusting. Van der Lee et al. [21] showed that the interaction between lopinavir/ritonavir (antiviral drugs used for treating COVID-19 patients) with lamotrigine might require a dose increment of 200%. Therefore, the need to increase the dose by said amount could lead to a higher consumption of lamotrigine, thus increasing its concentration in wastewater. This lamotrigine increase remains a problem because it is a persistent compound found in wastewater and brings with it complex degradation as carried out through conventional treatments. In some studies, these conventional treatments have resulted in an increase in lamotrigine concentration, which has been associated with a transformation of metabolite 5-desamino 5-Oxo-2,5-dihydro Lamotrigine back to lamotrigine [22].

Hypolipidemic drugs, such as fenofibric acid and gemfibrozil, maintained a similar trend in pre and post-pandemic periods. However, some studies have shown that these compounds can serve as effective treatments for COVID-19 infections. Fenofibric acid is the active form of fenofibrate which demonstrates that it could become a potential therapeutic agent for preventing contagions and reducing the severity of COVID-19-infected patients [23].

Determination of ecological hazard pre and post-COVID-19 pandemic

The ecological hazard was estimated using the hazard quotient (HQ) method, according to Equation (1) [24].

| (1) |

where MEC is the measured environmental concentration (μgL−1), PNEC is the predicted no-effect concentration that refers to the highest concentration at which there are no adverse effects on an indicator organism (μgL−1). PNEC is determined according to Equation (2).

| (2) |

The PNEC value was calculated by applying assessment factors (AF) based on available long-term no observed effects concentration (NOEC) toxicity data on fish, daphnias, and algae, or short-term EC50 data [24]. The ecotoxicological data were taken from The ECOTOXicology Knowledgebase (ECOTOX). It was created and is now maintained by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, which can be viewed via the following link: https://cfpub.epa.gov/ecotox/help.cfm.

HQ is interpreted as follows: no hazard when HQ < 0.1; insignificant hazard but potential adverse effects should be considered when between 0.1 and 1.0; medium hazard with moderate effects when between 1.0 and 10; and high hazard when HQ > 10.

Table 1 presents the ecotoxicological data of indicator organisms for each pharmaceutical compound. No ecotoxicological data were found for CBZ-Diol, while for lamotrigine, the HQ was applied from the PNEC value, as reported in previous studies [25]. HQ was determined from the maximum concentrations of pharmaceutical compounds (MEC) for each year between 2015 and 2022. The Literature data for the calculation of the HQ of each compound are included in the final part of Table 1.

Table 1.

The results of HQ study show that gemfibrozil, ibuprofen, and naproxen had a consistently high ecological hazard throughout the duration of the study. Additionally, diclofenac and paracetamol demonstrated medium to high HQ values, but saw a significant increase in their post-COVID HQ values, ranging from 2 to 14 times higher than the average pre-COVID HQ values. It is noteworthy that diclofenac saw the largest increase among these drugs.

These results raise concern due to the negative impact of these compounds on the aquatic biota of the recipient water body. In relation to this, Erhunmwunse et al. [46] reported that 10 μgL−1 of paracetamol can produce teratogenic, neurotoxic, and cardiotoxic effects in the embryo and larvae of Clarias gariepinus. This level of paracetamol concentration is less than the highest value reported in this study, which was up to 180 μgL−1 (Figure 1). In addition, ibuprofen and naproxen have been related to fish reproduction issues and are, therefore, considered endocrine disruptors [47,48]. Diclofenac has also shown toxic effects on aquatic organisms including hormonal disorders in crustaceans at concentrations of 0.25 μgL−1 [49]. This concentration is 34 times lower than the maximum value found in this study. Gemfibrozil is also considered to pose a threat to embryonic development due to its potential to cause genotoxicity and toxic effects [36,50,51].

The HQ results indicate that carbamazepine has a medium potential to affect the aquatic biota, which is a cause of concern due to some alterations observed in aquatic organisms. A recent study reported that environmental concentrations of carbamazepine could induce oxidative DNA damage in the livers of Chinese minnows, with notable effects when concentrations were at 0.91 μgL−1 [28]. This concentration level is slightly higher when compared to the highest concentration levels found in Santiago de Cali's wastewater.

According to the results which were obtained between 2015 and 2022, it is possible to conclude that the COVID-19 pandemic may have had a negative impact on the aquatic biota of the Cauca River. This result is primarily due to the increased consumption of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs, such as diclofenac, ibuprofen, naproxen, and paracetamol. These findings may provide an indirect measurement of COVID-19's impact on Santiago de Cali and serve as a warning to public health and environmental entities regarding the potential consequences of excessive use of over-the-counter medication.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Fiderman Machuca reports financial support was provided by Ibero-American Program of Science and Technology for Development.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Universidad del Valle, Minciencias (Colombia) and CYTED program for funding the project Contaminantes emergentes en aguas residuales: Innovación para la detección y eliminación - CEARAL. Grant No FP-490-2021. They would also like to extend their thanks to EMCALI EICE ESP for granting them access to the Cali wastewater treatment plant's facilities and the TZW laboratory in Germany for providing technical assistance in determining pharmaceutical compounds.

This review comes from a themed issue on Environmental Technologies 2023: Eco-Friendly and Advanced Technologies for Pollutant Remediation and Management

Edited by Palanivel Sathishkumar, Abirami Ramu Ganesan, Tony Hadibarata and Thava Palanisami

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coesh.2023.100457.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The followings are the supplementary data to this article.

WWTP location.tif.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Pouran S.R., Aziz A.A., Daud W.M.A.W. Review on the main advances in photo-Fenton oxidation system for recalcitrant wastewaters. J Ind Eng Chem. 2015;21:53–69. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bedoya-Ríos D.F., Lara-Borrero J.A., Duque-Pardo V., Madera-Parra C.A., Jimenez E.M., Toro A.F. Study of the occurrence and ecosystem danger of selected endocrine disruptors in the urban water cycle of the city of Bogotá, Colombia. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A. 2018;53:317–325. doi: 10.1080/10934529.2017.1401372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madera-Parra C.A., Jiménez-Bambague E.M., Toro-Vélez A.F., Lara-Borrero J.A., Bedoya-Ríos D.F., Duque-Pardo V. Estudio exploratorio de la presencia de microcontaminantes en el ciclo urbano del agua en Colombia: caso de estudio Santiago de Cali. Rev Int Contam Ambient. 2018;34:475–487. [Google Scholar]; This study was the first report about the presence of pharmaceutical compounds in drinking water, surface water, and wastewater in Santiago de Cali, Colombia. This study allowed identifying the issues associated with the presence of these micropollutants and their effects on the aquatic biota.

- 4.Botero-Coy A.M., Martínez-Pachón D., Boix C., Rincón R.J., Castillo N., Arias-Marín L., Manrique-Losada L., Torres-Palma R., Moncayo-Lasso A., Hernández F. An investigation into the occurrence and removal of pharmaceuticals in Colombian wastewater. Sci Total Environ. 2018;642:842–853. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.INS . Instituto Nacional de Salud; 2022. Covid 19 en Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- 6.MINSALUD . Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social; 2022. Vacunación contra COVID-19 en Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadoff J., Gray G., Vandebosch A., Cárdenas V., Shukarev G., Grinsztejn B., Goepfert P.A., Truyers C., Fennema H., Spiessens B. Safety and efficacy of single-dose Ad26. COV2. S vaccine against Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2187–2201. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almufty H.B., Mohammed S.A., Abdullah A.M., Merza M.A. Potential adverse effects of COVID19 vaccines among Iraqi population; a comparison between the three available vaccines in Iraq; a retrospective cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metabol Syndr: Clin Res Rev. 2021;15 doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.102207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morales-Paredes C.A., Rodríguez-Díaz J.M., Boluda-Botella N. Pharmaceutical compounds used in the COVID-19 pandemic: a review of their presence in water and treatment techniques for their elimination. Sci Total Environ. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiménez-Bambague E.M., Madera-Parra C.A., Ortiz-Escobar A.C., Morales-Acosta P.A., Peña-Salamanca E.J., Machuca-Martínez F. Case study: Santiago de cali-Colombia. Water Science and Technology; 2020. High-rate algal pond for removal of pharmaceutical compounds from urban domestic wastewater under tropical conditions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiménez-Bambague E.M., Madera-Parra C.A., Peña-Salamanca E.J. Eliminación de compuestos farmacéuticos presentes en el agua residual doméstica mediante un tratamiento primario avanzado. Ingeniería y Competitividad. 2020;22:10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S.-H., Kim K.-H., Lee M., Lee B.-D. Detection status and removal characteristics of pharmaceuticals in wastewater treatment effluent. J Water Process Eng. 2019;31 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carballa M., Omil F., Lema J.M. Removal of cosmetic ingredients and pharmaceuticals in sewage primary treatment. Water Res. 2005;39:4790–4796. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suarez S., Lema J.M., Omil F. Pre-treatment of hospital wastewater by coagulation–flocculation and flotation. Bioresour Technol. 2009;100:2138–2146. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park J., Cho K.H., Lee E., Lee S., Cho J. Sorption of pharmaceuticals to soil organic matter in a constructed wetland by electrostatic interaction. Sci Total Environ. 2018;635:1345–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi E.E., Dhar A., Petruschke R., Locht C., Buchy P., Low J.G.H. Use of analgesics/antipyretics in the management of symptoms associated with COVID-19 vaccination. npj Vaccines. 2022;7:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41541-022-00453-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study indicates the use of analgesics to alleviate the symptoms of COVID-19 vaccination, which is related to the presence of these compounds in the wastewater.

- 17.Galani A., Alygizakis N., Aalizadeh R., Kastritis E., Dimopoulos M.-A., Thomaidis N.S. Patterns of pharmaceuticals use during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Athens, Greece as revealed by wastewater-based epidemiology. Sci Total Environ. 2021;798 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Little P. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2020. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and covid-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinstadler V., Ausweger V., Grabher A.-L., Kreidl M., Huber S., Grander J., Haslacher S., Singer K., Schlapp-Hackl M., Sorg M. Monitoring drug consumption in Innsbruck during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) lockdown by wastewater analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2021;757 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asadi-Pooya A.A., Attar A., Moghadami M., Karimzadeh I. Management of COVID-19 in people with epilepsy: drug considerations. Neurol Sci. 2020;41:2005–2011. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04549-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study exposes the interaction between antiepileptics drugs with COVID-19 medications and provides a possible explanation for the increase in lamotrigine after to COVID-19 pandemic.

- 21.Van der Lee M.J., Dawood L., ter Hofstede H.J., de Graaff-Teulen M.J., van Ewijk-Beneken Kolmer E.W., Caliskan-Yassen N., Koopmans P.P., Burger D.M. Lopinavir/ritonavir reduces lamotrigine plasma concentrations in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Therapeut. 2006;80:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonja B., Pérez S., Barceló D. Human metabolite lamotrigine-N 2-glucuronide is the principal source of lamotrigine-derived compounds in wastewater treatment plants and surface water. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50:154–164. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b03691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study argues the cause of the concentration increase of lamotrigine in wastewater. This concentration increase is associated with the back-transformation of metabolite 5-desamino-5-oxo-2,5-dihydrolamotrigine to lamotrigine.

- 23.Yasmin F., Zeeshan M.H., Ullah I. The role of fenofibrate in the treatment of COVID-19. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2022;74 doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.TGD E: Technical guidance document on risk assessment in support of commission directive 93/67/EEC on risk assessment for new notified substances . Part II. European commission joint research centre. EUR; 2003. Commission regulation (EC) No 1488/94 on risk assessment for existing substances, and directive 98/8/EC of the European parliament and of the council concerning the placing of biocidal products on the market. Part I–IV, European chemicals bureau (ECB), JRC-ispra (VA), Italy, April 2003; p. 20418. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Topaz T., Boxall A., Suari Y., Egozi R., Sade T., Chefetz B. Ecological risk dynamics of pharmaceuticals in micro-estuary environments. Environ Sci Technol. 2020;54:11182–11190. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W., Zhang M., Lin K., Sun W., Xiong B., Guo M., Cui X., Fu R. Eco-toxicological effect of carbamazepine on scenedesmus obliquus and chlorella pyrenoidosa. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2012;33:344–352. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrari Bt, Paxeus N., Giudice R.L., Pollio A., Garric J. Ecotoxicological impact of pharmaceuticals found in treated wastewaters: study of carbamazepine, clofibric acid, and diclofenac. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2003;55:359–370. doi: 10.1016/s0147-6513(02)00082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S., Chen R., Wang M., Zha J. Carbamazepine at environmentally relevant concentrations caused DNA damage and apoptosis in the liver of Chinese rare minnows (Gobiocypris rarus) by the Ras/Raf/ERK/p53 signaling pathway. Environ Pollut. 2021;270 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study shows the effects of carbamazepine's environmental concentration in fish. These results are a baseline for evaluating the potential ecological hazard in the wastewater studied.

- 29.Ferrari B., Mons R., Vollat B., Fraysse B., Paxēaus N., Giudice R.L., Pollio A., Garric J. Environmental risk assessment of six human pharmaceuticals: are the current environmental risk assessment procedures sufficient for the protection of the aquatic environment? Environ Toxicol Chem. 2004;23:1344–1354. doi: 10.1897/03-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joachim S., Beaudouin R., Daniele G., Geffard A., Bado-Nilles A., Tebby C., Palluel O., Dedourge-Geffard O., Fieu M., Bonnard M. Effects of diclofenac on sentinel species and aquatic communities in semi-natural conditions. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;211 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study presents the effects associated with diclofenac and allows us to identify the potential impact on the aquatic biota. This data is used to determine the potential ecological hazard.

- 31.Rosal R., Rodea-Palomares I., Boltes K., Fernández-Piñas F., Leganés F., Gonzalo S., Petre A. Ecotoxicity assessment of lipid regulators in water and biologically treated wastewater using three aquatic organisms. Environ Sci Pollut Control Ser. 2010;17:135–144. doi: 10.1007/s11356-009-0137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madureira T.V., Rocha M.J., Cruzeiro C., Rodrigues I., Monteiro R.A., Rocha E. The toxicity potential of pharmaceuticals found in the Douro River estuary (Portugal): evaluation of impacts on fish liver, by histopathology, stereology, vitellogenin and CYP1A immunohistochemistry, after sub-acute exposures of the zebrafish model. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2012;34:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siebel A.M., Piato A.L., Schaefer I.C., Nery L.R., Bogo M.R., Bonan C.D. Antiepileptic drugs prevent changes in adenosine deamination during acute seizure episodes in adult zebrafish. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;104:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minguez L., Pedelucq J., Farcy E., Ballandonne C., Budzinski H., Halm-Lemeille M.-P. Toxicities of 48 pharmaceuticals and their freshwater and marine environmental assessment in northwestern France. Environ Sci Pollut Control Ser. 2016;23:4992–5001. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3662-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isidori M., Nardelli A., Pascarella L., Rubino M., Parrella A. Toxic and genotoxic impact of fibrates and their photoproducts on non-target organisms. Environ Int. 2007;33:635–641. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rocco L., Frenzilli G., Zito G., Archimandritis A., Peluso C., Stingo V. Genotoxic effects in fish induced by pharmacological agents present in the sewage of some Italian water-treatment plants. Environ Toxicol. 2012;27:18–25. doi: 10.1002/tox.20607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lawrence J.R., Swerhone G.D., Wassenaar L.I., Neu T.R. Effects of selected pharmaceuticals on riverine biofilm communities. Can J Microbiol. 2005;51:655–669. doi: 10.1139/w05-047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heckmann L.-H., Callaghan A., Hooper H.L., Connon R., Hutchinson T.H., Maund S.J., Sibly R.M. Chronic toxicity of ibuprofen to Daphnia magna: effects on life history traits and population dynamics. Toxicol Lett. 2007;172:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han S., Choi K., Kim J., Ji K., Kim S., Ahn B., Yun J., Choi K., Khim J.S., Zhang X. Endocrine disruption and consequences of chronic exposure to ibuprofen in Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) and freshwater cladocerans Daphnia magna and Moina macrocopa. Aquat Toxicol. 2010;98:256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mennillo E., Arukwe A., Monni G., Meucci V., Intorre L., Pretti C. Ecotoxicological properties of ketoprofen and the S (+)-enantiomer (dexketoprofen): bioassays in freshwater model species and biomarkers in fish PLHC-1 cell line. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2018;37:201–212. doi: 10.1002/etc.3943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mennillo E., Pretti C., Cappelli F., Luci G., Intorre L., Meucci V., Arukwe A. Novel organ-specific effects of Ketoprofen and its enantiomer, dexketoprofen on toxicological response transcripts and their functional products in salmon. Aquat Toxicol. 2020;229 doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2020.105677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harada A., Komori K., Nakada N., Kitamura K., Suzuki Y. Biological effects of PPCPs on aquatic lives and evaluation of river waters affected by different wastewater treatment levels. Water Sci Technol. 2008;58:1541–1546. doi: 10.2166/wst.2008.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Isidori M., Lavorgna M., Nardelli A., Parrella A., Previtera L., Rubino M. Ecotoxicity of naproxen and its phototransformation products. Sci Total Environ. 2005;348:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ceballos-Laita L., Bes M., Peleato M., Fillat M.F., Calvo L. 2015. Effects of benzene and several pharmaceuticals on the growth and microcystin production in Microcystis ruginosa PCC 7806. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castro B.B., Freches A., Rodrigues M., Nunes B., Antunes S. Transgenerational effects of toxicants: an extension of the daphnia 21-day chronic assay? Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2018;74:616–626. doi: 10.1007/s00244-018-0507-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhunmwunse N.O., Tongo I., Ezemonye L.I. Acute effects of acetaminophen on the developmental, swimming performance and cardiovascular activities of the African catfish embryos/larvae (Clarias gariepinus) Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;208 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrated the effects of acetaminophen (paracetamol) on the African catfish. These identified effects may interfere with the survival of aquatic organisms and occur at higher concentrations than those reported by us.

- 47.Flippin J.L., Huggett D., Foran C.M. Changes in the timing of reproduction following chronic exposure to ibuprofen in Japanese medaka, Oryzias latipes. Aquat Toxicol. 2007;81:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kwak K., Ji K., Kho Y., Kim P., Lee J., Ryu J., Choi K. Chronic toxicity and endocrine disruption of naproxen in freshwater waterfleas and fish, and steroidogenic alteration using H295R cell assay. Chemosphere. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gonzalez-Rey M., Bebianno M.J. Effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) diclofenac exposure in mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. Aquat Toxicol. 2014;148:221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verlicchi P., Al Aukidy M., Zambello E. Occurrence of pharmaceutical compounds in urban wastewater: removal, mass load and environmental risk after a secondary treatment—a review. Sci Total Environ. 2012;429:123–155. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Henriques J.F., Almeida A.R., Andrade T., Koba O., Golovko O., Soares A.M., Oliveira M., Domingues I. Effects of the lipid regulator drug Gemfibrozil: a toxicological and behavioral perspective. Aquat Toxicol. 2016;170:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2015.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.