Abstract

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on essential service workers has given rise to their newfound “hero” status, resulting in a dramatic shift of their occupational value. Service work has been long envisioned as “dirty work”, and further, stigmatized by members of society (the Out-Group), until recently. This study utilized occupational stigma theory to identify the mechanisms under which both essential service workers and society at large came to unify around the importance of perceived dirty work in the United States. Critical discourse analysis was employed as a qualitative methodology, particularly examining the In- and Out-Group’s coping mechanisms for coming to terms with the value of “dirty” service work heroes. Theoretical implications include the utilization of stigma theory for Out-Groups, and revealed a previously undetected Out-Group coping tactic. Practical implications include the urgency for keeping the “hero” story alive so that all service workers benefit from the movement.

Keywords: Occupational stigma theory, Coping mechanisms, Line-level employees, Hourly employees, Heroes, Hospitality industry

1. Introduction

“Work is part of everyone’s daily life and is crucial to a person’s dignity, well-being and development as a human being.” - International Labour Organization, Introduction to the International Labour Standards, 2019

The role of work in our lives is undeniable, as work provides the means to meet basic needs, a sense of belonging to a group outside of one’s family, opportunities to grow and develop, and a source of identity (Hulin, 2002). Despite the potential for work to provide positive meaning and identity, scholars note that a work-based identity can be pleasant or painful (Green, 1993). Certain occupations carry stigma (Kreiner et al., 2006), with far-reaching implications for individual identity, employee safety and well-being, and the broader societal narrative on the function of such occupations (Bickmeier et al., 2015). In particular, certain low-wage hourly jobs within the services industries have been the target of such stigma, including those in retail grocery (Baldissarri et al., 2014), food service (Shigihara, 2018; Wildes, 2005), hotel housekeeping (Nimri et al., 2020), consumer retail (Duemmler and Caprani, 2017), and taxi/transportation services (Phung et al., 2020; Ravenelle, 2019).

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, occupations previously stigmatized, or categorized as “dirty work”, have been deemed essential, followed by a marked shift in societal discourse on the value of these occupations. For example, the cover of a recent TIME issue (an honor typically reflective of rank, title, and influence) featured workers in formally stigmatized occupations performing their work amid the dangers of the COVID-19 pandemic, and labeled them “the heroes of the front lines” (Felsenthal, 2020). Historically undervalued, supermarket employees, foodservice workers, and food delivery drivers’ social standing suddenly shifted to “essential”, and propelled these workers into hero status (Guasti, 2020).

This sudden and drastic shift in the cultural narrative on the value of previously stigmatized occupations is unprecedented, and may have long-lasting implications on the value of service work as perceived by both the members of these essential service occupations, and by “outsiders” not belonging to those occupations. Moreover, members of society who had previously cast aspersions on the value of service work, and by extension, the labor rights owed to service workers (i.e. healthcare, living wages, etc.), have publicly contended with their previous (mis)conceptions of service work and workers. The purpose of this study was to examine In-Group (i.e. the stigmatized) and Out-Group (i.e. the stimatizers) reactions to the “new hero status” ascribed to front line service workers. Using a critical discourse analysis methodology of news articles published immediately before and during the first few weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, the discursive management of stigmatized identities (Meisenbach, 2010) were examined, and disparate approaches were addressed to managing individual and collective coping responses to stigma (Kreiner et al., 2006) in some service-related industries.

This study offers several contributions to the literature. First, a novel way to understand the evolution of occupational stigma of essential line level service workers in light of the COVID-19 pandemic is presented. Second, this study extends the literature on occupational stigma by examining how extreme and disruptive events (Hällgren et al., 2018) can spur dynamic shifts in insider and outsider views of occupational stigma, and how these groups cope with changing stigma perceptions. Third, the role of outsiders in occupational stigma is explicitly examined. While stigma theory inherently rests on the notion that occupational stigma is imposed based on outsiders’ views of the work (Ashforth et al., 2008; Kreiner et al., 2006), little research exists examining occupational stigma processes in outsiders. However, this research suggests that outsiders, like insiders, employ a variety of strategies to cope with stigmatization of occupations, especially when societal views of those occupations shift and result in dissonance. Fourth, discourse analysis is offered as a valuable methodological strategy to understand how insiders and outsiders respond to occupational stigma change. This work also has important practical contributions in terms of suggesting various strategies that service workers can use to foster positive occupational identities during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, and a deeper understanding of this phenomenon can provide insight into the ways by which service workers’ status in society may be enhanced in the future.

2. Literature Review

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of October 11, 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic had infected 37,109,851 people worldwide, resulting in 1,070,355 confirmed deaths (WHO, 2020). Compared with other pandemics of the 20th and 21st centuries, the level of devastation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented due to its pre-symptomatic transmission, which is undetectable in asymptomatic patients (Rogers, 2020). The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) illness and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), while both having high case fatality rates well above COVID-19, did not cause the same level of devastation because they were not easily transmittable (Gavi, 2020; Rogers, 2020). Once people became infected with SARS or MERS, they immediately developed symptoms, and stayed home or were hospitalized, thus inhibiting the spread of the virus. Other viruses, such as the Swine Flu (H1N1) and Ebola, while both deadly, did not have as detrimental effects on society, due to lack of severity (H1N1) and difficulty in transmission (Ebola). Regardless, due to its high level of transmission, societal control measures for COVID-19 have had unprecedented effects on the loss of life and the global economy (Rogers, 2020). While the Spanish Flu of 1918 was followed by a recession, the more recent pandemics in modern history such as SARS, MERS, H1N1, and Ebola, were followed by short economic downturns (Gavi, 2020). Thus, the effects of COVID-19 on health and life require closer evaluation as to the impacts on global economies and the subsequent social phenomenon emerging from the devastation, particularly on those sectors most impacted, such as the services industries.

2.1. Service workers’ transition to Hero status

In the context of the substantial decline in U.S. employment at the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020 (U.S. BLS, 2020), only essential workers were spared from being laid off or furloughed. Essential service workers considered themselves fortunate to remain employed, and through an anecdotal social phenomenon widely reported in the news and other media in the U.S., these workers quickly rose to “hero” status (Brogan, 2020). Service employees’ rapid social status ascent was not prevalent, nor even imaginable, only weeks prior to the pandemic shut down, where long-held perceptions of line-level hospitality and service work in the U.S. was consistently equated with low skill and low wages (Summers et al., 2018; Wildes, 2005). Previously stigmatized by those outside the services industries, herein referred to as the Out-Group, hourly service workers’ (i.e. the In-Group) experiences of being stigmatized has adversely affected their self-concept and work engagement (Ashforth et al., 2017; Duemmler and Caprani, 2017; Shigihara, 2018). Kreiner et al. (2006) described stigmatized workers as a group subjected to others’ devaluing opinions of their humanity, and whose work is viewed as flawed in some respects. In the U.S. and in other developed economies, service jobs have long been viewed as low-level and servile, and in many cases dirty, often stigmatized and relegated to those with few employment options (Robinson et al., 2016), or newly entering the workforce with minimal skills (Ashforth and Kreiner, 2014; David and Dorn, 2013; Mooney et al., 2016; Powell and Watson, 2006).

In recent human history, service workers have never before encountered such a seismic shift in Out-Group favoritism and appreciation. Within the period of only a few weeks, the perception of line-level hourly service workers changed from one of obscurity into one of high standing, where essential service workers became appreciated, respected, and suddenly valued by the Out-Group (SHRM, 2020). Anecdotal news sources reported that essential service workers were placing their own personal health in jeopardy, and felt that while they were honored in this new hero role, they were also perplexed and resentful as to why they were not held to the same regard prior to the pandemic (Brogan, 2020; SHRM, 2020; Selyukh, 2020). Given the rapidity with which this social phenomenon transpired, essential line level service workers were surprised and confused by a nation’s sudden transition and positive response to line level work in the services industries (Brogan, 2020). If the processes and implications of this rapid shift are to be understood, it is imperative to recognize why certain occupations carry stigma, as well as the attitudinal and behavioral outcomes of that stigma. To that end, occupational stigma theory will be used to illustrate the mechanisms of how service workers and society in general view service work in the context of COVID-19.

2.2. COVID-19 through the Lens of occupational stigma theory

The literature on occupational stigma is typically framed through the lens of social identity theory (Tajfel, 1978a,b), which offers a useful framework to examine how perceptions of groups vary for those within and outside of the group. While this framework has afforded many insights on stigmatized occupational identities, existing literature has not yet accounted for the rapid and radical shifts in identity initiated by shared societal events. Although some frameworks do conceptualize stigma as dynamic, based on the types of tasks that are performed (i.e. compartmentalized stigma; Kreiner et al., 2006), features outside of the job have not yet been explored as a prompting event for a dynamic shift in perceived stigma. COVID-19 highlights a unique opportunity to expand an existing theoretical lens, given that historical events provide a sense of shared meaning that is “important in creating, maintaining, and changing people’s identity” (Liu and Hilton, 2005, p. 537).

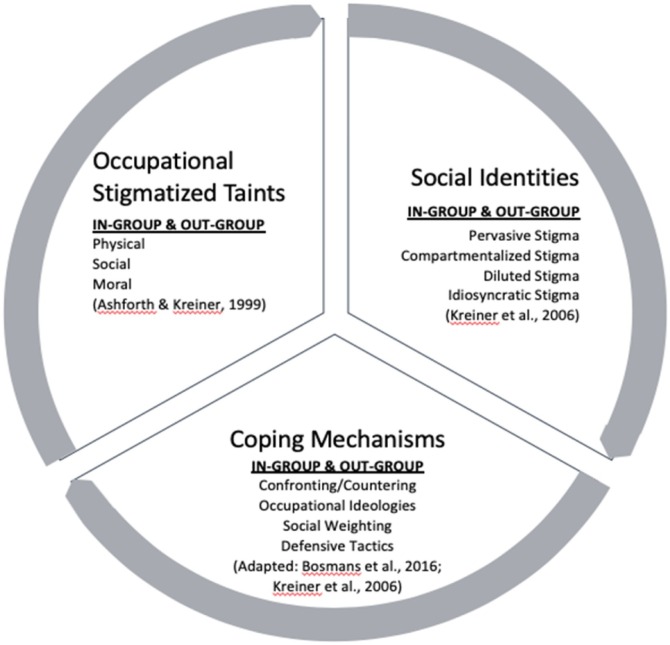

The conceptual framework for this study, depicted in Fig. 1 , was based on an expansion of occupational stigma theory to understand how members from the essential service worker In-Group and those members from the Out-Group (i.e. societal ‘outsiders’) navigated this rapid shift in perceptions of line level service work. Within this framework, the following core components of occupational stigma theory were considered (the lines within each section of the figure representing coding options within each construct): taint, social identities, and coping mechanisms. Consistent with occupational stigma theory, the conceptual model considered both insider and outsider reactions to essential service workers’ new hero status. As coping is considered critical to how individuals and collectives manage stigma, this study examined the various ways by which insiders and outsiders cope with this dynamically evolving stigma. Interpreting these coping strategies hold promise for understanding how insiders and outsiders try to manage simultaneous positive and negative views of/towards service workers, which is crucial for downstream outcomes, at both the individual and societal levels (Ashforth et al., 2017).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model guiding the research.

2.2.1. Occupational stigmatized taints

Social identity theory proposes that in order to reduce uncertainty in social interactions, individuals categorize themselves into groups (Hogg and Terry, 2000). Individuals then compare their group to Out-Groups, favoring their own group in a positive way, or extolling and praising their In-Group (Kreiner et al., 2006). When the identity of a group is threatened by external forces (e.g., societal stigma), In-Group members are motivated to protect their group’s positive identity (Mikolon et al., 2020; Spears et al., 2001; Tajfel and Turner, 1986).

Identity becomes especially important in stigmatized occupations where constructing positive, self-enhancing identities may be especially difficult due to the ‘taint’ associated with these occupations (Ashforth and Kreiner, 1999; Shigihara, 2018). These tainted occupations are referred to as “dirty work” occupations and are classified based on the type “dirt” individuals in the occupation are exposed to. Ashforth and Kreiner (1999) discuss three types of taint: physical, social and moral. Physical taint refers to occupations that deal directly with the physically dirty (garbage, death, etc.) or are performed under dangerous circumstances. Social taint refers to occupations that come into regular contact with other stigmatized individuals or have a servile role with outgroup members, as in the case of service workers. Moral taint refers to occupations that are themselves seen as sinful or contrary to societal norms. Physical, social and moral taint are not mutually exclusive, and many occupations may be exposed to multiple forms of taint (Ashforth and Kreiner, 1999; Shigihara, 2018). In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, socially tainted occupations, especially service occupations, are increasingly risking exposure to the virus in order to continue meeting the demands of society, thereby increasing their exposure to physical taint.

2.2.2. Social identities

In addition to the three types of taint, stigmatized occupations can be categorized based on the depth and breadth of their exposure to taint. Depth is the extent to which an employee is directly involved with the tainted aspect of the occupation, while breadth refers to the proportion of the work that is dirty (Kreiner et al., 2006). In other words, depth refers to how deeply involved workers are with the stigmatized factors of the job, while breadth refers to how much of an employee’s job relates to the stigma. Kreiner et al. (2006) identified four categories of occupational stigma; pervasive stigma, compartmentalized stigma, diluted stigma, and idiosyncratic stigma. Pervasive stigma refers to those occupations with high depth and high breadth, such as prison guards or embalmers. Compartmentalized stigma refers to high depth but low breadth, such as an occupation related to reporting, for example. Diluted stigma refers to occupations with low depth and high breadth, as with auto mechanics. Idiosyncratic stigma refers to occupations with low depth and low breadth, which Kreiner et al. (2006) argued could be allocated among all other occupations not falling into one of the other three categories. Because service workers risk greater exposure to the virus in many aspects of their jobs, including those that were not previously seen as physically tainted (e.g., interactions with the public), these occupations may be viewed as increasingly and pervasively stigmatized (Caza et al., 2018).

2.2.3. Coping strategies

This study not only examined shifting occupational stigmas and social identities, but also how occupational insiders and outsiders coped with these shifting societal dynamics. Kreiner et al. (2006) offered a useful typology of tactics that individuals use to cope with occupational stigma that may provide a starting point for examining this question. The first general category relates to the ideology of stigma, or the belief system surrounding the taint. Here, work can be reframed such that the more positive aspects are highlighted, while the negative aspects are minimized. Work can also be recalibrated, meaning that the magnitude and/or value of various job tasks are evaluated against an adjusted standard (meaning that the stigmatized tasks are evaluated as “not a major part of the job”). Finally, work can be refocused such that the attention is not so concentrated on tasks with taint (Kreiner et al., 2006). Second, members of stigmatized occupations can also participate in social weighting, in which the opinions of Out-Group members are selectively affirmed or discredited. A final class of tactics, cognitive and behavioral, represents coping tactics meant to buffer the felt stress associated with stigma. For example, a stigmatized employee could engage in coping mechanisms that address the problem of taint, or their emotions in the face of stigma (Kreiner et al., 2006).

Expanding on occupational stigma theory, this study examined how members from the essential service worker In-Group, together with societal Out-Group members, have navigated the rapid shift in views of essential line level service workers, broadly, and the Out-Group’s coping mechanisms with this shift, specifically. As coping is considered critical to how individuals and collectives manage stigma, this study examined the various ways by which members of the In-Group and Out-Group coped with this dynamically evolving stigma (Caza et al., 2018).

3. Method

In general, the effects of COVID-19 adversely affected social science researchers’ ability to collect qualitative interview data in the early stages of the pandemic, forcing alternative solutions for investigating research questions at the time (Kimbrough, 2020; Shiffman, 2020). In this study, the aim was to examine In-Group and Out-Group perceptions and coping mechanisms of formerly stigmatized service workers, who quickly ascended into hero status due to the employment mandate for essential workers during the pandemic in the U.S. Attributed to mandates during the first weeks of the regional “stay at home orders” in the U.S., a decision was made to capture public discourse at the beginning of the pandemic as a proxy for the individual- and societal-level sentiments.

3.1. Critical discourse analysis

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) was the methodology employed in this study, based on the work of Fairclough (1992), who described CDA as an interdisciplinary approach which studies language as a form of social practice. The working assumption of CDA is that language can be used as a tool to wield power and/or create social change. Fairclough (1993) posited a three-dimensional framework to conduct CDA, which includes (1) descriptive text analysis at the word level; (2) discursive practice, where the text is subject to interpretation and where language holds values conveyed to the recipients; and (3) social practice as an explanation of the outputs and context of social events, analyzed at the norm level (Janks, 1997). CDA scholars agree that there is no commonly accepted way to conduct a discourse analysis (Gee, 2011; Small et al., 2008), although in general, CDA can follow along the same methodological steps as qualitative analysis within Fairclough’s (1992) framework. As all discourse shapes the reality of a society (Fairclough, 2017), the value of CDA methodology is to dissect and analyze the meaning of the discourses and the interpretations of those affected (Ignatova, 2020).

Prior empirical employee-focused health and safety studies have used CDA as a method and as a theoretical framework in stigmatized occupations (Zoller, 2003; Zhohar & Polachek, 2014). In the service industries context, a qualitative study about the behavioral roles of hotel controllers in Hong Kong, discourse analysis was used with interview transcripts, and revealed hotel controllers as the “company cops” of a hospitality organization (Gibson, 2002). CDA methodology was employed in a tourism study regarding in-flight magazine advertisements for Quantas Airlines and Air New Zealand, where the researchers argued that the discourse “socially sorted” consumers between those who were culturally acceptable airline travelers, and those who were not (Small et al., 2008). Other than the above few examples, the CDA methodology is underutilized in hospitality and service industries research, but fitting in this study due to the circumstances surrounding data collection at the time, and also as a novel approach in the discipline for garnering public sentiments.

3.2. Data collection rationale and procedure

The data were collected from publicly available news sources, and a search was conducted using Nexis Uni, a database that includes news sources from newspapers, wire services, magazines, SEC filings, law cases, state and federal codes, law review journals, and reference works, as well as a limited coverage of health administration news. The search terms for Nexis Uni were selected in line with the research purpose and theoretical lens pertaining to essential line level workers in the service industry context, and included: “essential worker*” or “essential employee*” or “critical infrastructure worker*” or “critical infrastructure employee*” and “hero*” or “identity*” or “stigma*”. Listing the search terms in this way ensured the news sources returned contained content pertaining to essential workers (also referred to as ‘essential employees’, or ‘critical infrastructure workers/employees’) and were relevant to at least one other topic or term pertaining to the research purpose and theoretical lens: hero, identity, or stigma.

Although healthcare workers were deemed essential during the COVID-19 crisis, the focus of this study excluded narrative specifically about the medical field, and centered on reports and news about line-level essential workers in retail grocery, foodservice, transportation, and consumer retail. The rationale for excluding the public narrative regarding essential healthcare and medical worker “heroes” was (1) line level low-paid workers from the services industries prior to COVID-19 did not enjoy a similar societal status as workers in healthcare; and (2) essential healthcare workers were on the front lines, caring for COVID-19 patients, whereas essential service workers were at the service of the public, or society in general. While there may be similarities in the various stigmas and taints between essential healthcare and line level service workers, for the purpose of this study, essential line level service workers were identified as the sampling frame in order to specify the more distinct public “hero” sentiments of grocery workers, foodservice employees, and taxi/Uber/delivery drivers serving the Out-Group, versus doctors and nurses treating COVID-19 patients directly.

The sampling frame was further restricted based on a period of time in order to stay within the timeline of the early outbreak of COVID-19 in the United States from January 1, 2020 to May 31, 2020 (Taylor, 2020). Furthermore, sources were restricted to the United States in order to avoid potential confounds with other countries, cultures, and timelines on the spread of COVID-19. News sources were also required to be written in English. Finally, sources pulled from “Briefings.com” and “WebNews – Academic” were excluded since those are not considered to be news sources. “Briefings.com” includes stock market and research reports, which were not relevant for the purposes of this project. The above search criteria yielded 67 articles, of which 5 were duplicates. Through the data screening process, it was determined that of the 62 articles, 16 did not contain content relevant to addressing the research question. As such, the analysis was conducted on the retained 46 news articles, with publication dates ranging from March 30, 2020 to May 31, 2020. Further justification for constraining data collected within this timeframe was that this period was within the last instances of shared work and social restrictions contributing to this phenomenon, as many businesses and regional areas reopened at some point in May 2020. If data were collected after May 2020, there would be less consistency in work and social restrictions. At the time of this writing (October 2020), there is now more variation between states, with some states pausing or reversing reopening, while others remain open (The New York Times, 2020).

Of these retained news sources, 24 were news transcripts (52.17%) from televised news sources such as CNN, PBS NewsHour, Fox News Network, MSNBC, and ABC News’ Good Morning America; 12 were published news articles (26.09%) from university newspapers such as the Cornell Daily Sun, Michigan Daily, Daily Targum, The Circle, as well as articles from States News Service, the Business Insider, and others. The search also yielded commentary/opinion sources, of which 8 (17.39%) were published articles from sources such as JD Supra, Business Wire, Electronic Urban Report, as well as university papers such as Michigan Daily, The Alestle, and others. Two articles (4.35%) were commentary/opinion transcripts from sources such as Business Wire and Naked Capitalism. For a summary of the data characteristics, see Appendix A.

3.3. Data analysis procedure

The data analysis procedure utilized a stepwise qualitative analytic approach, guided by Fairclough’s (1992) three-dimensional framework. First, the data sources were subject to a coding process at the text level, informed by the literature on stigma and coping mechanisms of dirty work of service workers. Second, the codes were organized according to frequency, revealing relationships between the In- and Out-Groups, and constructing meaning as discursive practice. Third, the overarching themes were assembled to offer insights and explanation of this social phenomenon, and how for a brief period of time, the social discourse related to essential service workers’ new hero status recorded a national conversation on Out-Group perceptions and accolades of essential line level service workers.

Two researchers on the team each coded all 46 documents independently utilizing Maxqda v.20 qualitative data analysis software, employing deductive and inductive coding approaches (Kuckartz and Radiker, 2019; Strauss and Corbin, 1998) to each of the steps listed above for CDA. More specifically, the data in each step were first coded according to a deductive approach, using predetermined coding categories from both the In-Group and the Out-Group perspectives, based on the conceptual framework (see Fig. 1). Specific coding definitions were adhered to in the codebook so that the researchers could administer the deductive codes in a reliable manner (see Appendix B). In the second round of coding, the researchers applied an inductive approach to the data, utilizing axial coding methods, which incorporated a combination of inductive and deductive decision-making, relating the codes to each other, thus constructing linkages in meaning (Strauss and Corbin, 1998).

The procedures to establish the credibility (i.e. validity) of this methodology were based on Cresswell and Miller’s (2000) two-dimensional approach incorporating the researchers’ lens perspective and paradigm assumptions. Specifically, the independent and iterative coding procedures outlined above were subject to a triangulation process among all researchers in this study, in which several virtual meetings were conducted to corroborate the data, the codes generated from the data, and the overarching themes assigned to the coding frequencies (Cresswell and Miller, 2000). This procedure satisfied the researchers’ lens perspective criteria. The use of thick, rich descriptions throughout the following Results and Discussion sections provided another procedure for establishing credibility (i.e. validity), in which the example narratives illustrate the data in vivid detail, thus providing readers with a transparent account of the source data (Cresswell and Miller, 2000). This procedure met the paradigm assumptions criteria for credibility in qualitative analysis.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Coding and cluster mapping results

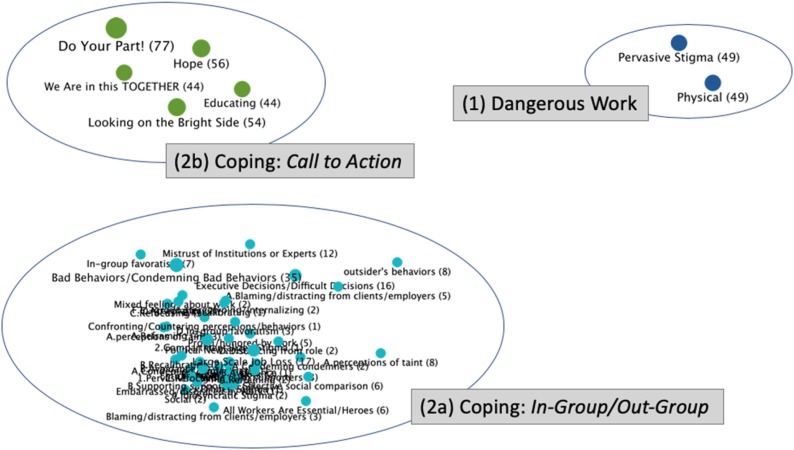

In the final analysis, a total of 479 codes applicable to the conceptual model were generated across the 46 documents, with varying frequencies. A code co-occurrence analysis was conducted to determine the connections and interrelationships between and among the codes. Utilizing the code co-occurrence mapping capability within the Maxqda v.20 software, clusters of codes were generated based on (1) the frequency with which like-codes were assigned to the same text segment(s) (i.e. intersection); and (2) the proximity of like-codes to each other (see Fig. 2 and Table 1 ) (Kuckartz and Radiker, 2019). The results of the cluster mapping guided the research team in categorizing and organizing relevant themes and sub-themes. Triangulation was achieved by other members on the research team, who confirmed the relevant themes guided by dirty work, stigma, and coping theories. Below is a detailed discussion of the themes, with sample narratives from the data source documents.

Fig. 2.

Cluster map of coded segments according to frequencies (via dot size) and proximity/relationship (via closeness).

Table 1.

Code frequencies, percentages, and number of documents according to clustered themes.

| Theme | Parent Code | Sub-Code | Sub-Theme | Freq. | Sub-Freq | % | # Docs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Dangerous Work | Identities | Identities | Pervasive Stigma | 49 | 10.2% | 28 | |

| Occ. Taint | Occupation Stigmatized Taints | Physical Taint | 49 | 98 | 10.2% | 25 | |

| (2a) Coping: In-Group | Identities | Identities | Pervasive Stigma | 12 | 2.5% | 9 | |

| 4.Idiosyncratic Stigma | 2 | 14 | 0.4% | 2 | |||

| Occ. Taint | Occupation Stigmatized Taints | Physical | 11 | 2.3% | 8 | ||

| Social | 2 | 0.4% | 2 | ||||

| Moral | 1 | 14 | 0.2% | 1 | |||

| Coping | Confronting/Countering perceptions/behaviors | A. Perceptions of taint | 3 | 3 | 0.6% | 3 | |

| Occupational ideologies | A. Reframing | 4 | 0.8% | 4 | |||

| C. Refocusing | 3 | 0.6% | 3 | ||||

| B. Recalibrating | 2 | 9 | 0.4% | 2 | |||

| Social weighting | D. In-Group favoritism | 7 | 1.5% | 5 | |||

| B. Supporting supporters | 2 | 0.4% | 2 | ||||

| F. In-Group stereotyping/internalizing | 2 | 0.4% | 2 | ||||

| A. Condemning condemners | 1 | 0.2% | 1 | ||||

| C. Selective social comparison | 1 | 13 | 0.2% | 1 | |||

| Defensive tactics | A. Blaming/distracting fr clients/employers | 3 | 0.6% | 2 | |||

| B. Avoidance | 2 | 0.4% | 2 | ||||

| C. Acceptance | 2 | 7 | 0.4% | 2 | |||

| Out-Group | Identities | Identities | 4.Idiosyncratic Stigma | 2 | 0.4% | 1 | |

| 3.Diluted Stigma | 1 | 0.2% | 1 | ||||

| 2.Compartmentalized Stigma | 1 | 4 | 0.2% | 1 | |||

| Coping | Confronting/Countering perceptions/behaviors | A. Perceptions of taint | 8 | 1.7% | 6 | ||

| B. Outsider's behaviors | 8 | 16 | 1.7% | 4 | |||

| Occupational ideologies | A. Reframing | 2 | 0.4% | 2 | |||

| B. Recalibrating | 1 | 0.2% | 1 | ||||

| C. Refocusing | 1 | 4 | 0.2% | 1 | |||

| Social weighting | C. Selective social comparison | 6 | 1.3% | 5 | |||

| B. Supporting supporters | 3 | 0.6% | 3 | ||||

| D. In-Group favoritism | 3 | 0.6% | 2 | ||||

| A. Condemning condemners | 2 | 14 | 0.4% | 2 | |||

| Defensive tactics | A. Blaming/distracting fr clients/employers | 5 | 1.0% | 4 | |||

| D. Distancing from role | 2 | 0.4% | 2 | ||||

| B. Avoidance | 1 | 8 | 0.2% | 1 | |||

| (2b) Coping: Call to Action |

Do Your Part! | 77 | 16.1% | 23 | |||

| Hope | 56 | 11.7% | 16 | ||||

| Looking on the bright side | 54 | 11.3% | 21 | ||||

| We are in this TOGETHER | 44 | 9.2% | 16 | ||||

| Educating | 44 | 275 | 9.2% | 15 | |||

| TOTAL | 479 | 479 | 100% |

4.2. Overarching themes from the data

Based on the combined deductive and inductive coding approaches employed in the analysis (Kuckartz and Radiker, 2019; Strauss and Corbin, 1998), two overarching themes emerged from the data, derived from the coding frequencies and cluster analysis: (1) Dangerous Work and (2) Coping Mechanisms. The Coping Mechanisms theme was further categorized according to the following sub-themes: (a) In-Group/Out-Group, and (b) Call to Action: “Do Your Part!”. The Call to Action sub-theme emerged from the inductive axial coding process, and upon triangulation and confirmed in the literature, the researchers deemed this sub-theme as relevant to Coping Mechanisms in this study, a finding new to the literature. The following sections interpret these results through a dirty work and stigma lens.

4.3. Dangerous work: pervasive stigma and physical taint

An overarching theme identified in the data referred to Dangerous Work associated with essential service workers related to the pandemic in the U.S. While the clustered data for this theme relied on a total of 98 coded segments, slightly over 20% of the total codes, this theme was coded in over 50% of the source documents: Pervasive Stigma in 28 documents, and Physical Taint in 25 documents (see Fig. 2 and Table 1). From both the In-Group (i.e. the previously stigmatized or service workers) and the Out-Group (i.e. the stigmatizers’ or societal onlookers’) perspectives, danger was characterized in terms of Pervasive Stigma (freq = 49) and Physical Taint (freq = 49). This finding is consistent with previous literature on the taints associated with service work (e.g., Adib and Guerrier, 2003) and current conceptualizations of the COVID-19 contagion risk associated with essential tasks in service work (e.g., interaction with customers and food preparation) (Baker et al., 2020).

4.3.1. Pervasive stigma: breadth and depth

Consistent with prior research, essential service employees during COVID-19 worked in occupations which were classified by Kreiner et al. (2006) as carrying a pervasive stigma, both in the highest levels of breadth and depth of the perceived dirty work. In terms of the breadth of essential service workers’ dirtiness, the data revealed multiple instances of both the proportion of the work considered dirty, and the centrality of the dirt to the occupation (Kreiner et al., 2006). For example, a line level restaurant worker referred to the proportion of dirtiness in the literal sense,

“I am practically bathing in hand sanitizer. I fear that I’m a soldier on the front line, bound to be the first to fall. Over cheeseburgers” [43].

From the Out-Group perspective, the data revealed commentary on the proportion of dirtiness with the perceived danger in working in an environment with a surging death toll [2], among line level workers protesting for personal protective equipment (PPE) [5], followed by Out-Group members’ fundraising initiatives to supply masks and PPE [7]. All of these instances describe the pervasive extent or proportion of dirtiness while working in an essential service capacity during COVID-19.

The centrality of the dirt associated with the breadth of the pervasive stigma of service employees was described by how their core work activities were defined by their inherent “essential-ness”. For example, truck drivers emphasized the critical and essential-ness central to their work, claiming that without them, “None of you would get anything. No food, medical supplies, PPE, fuel, etc.” [11]. These centrality perceptions resonated with members from the Out-Group in a similar way:

“Any person in this country that is helping keep the lights on, and helping us live day by day, whether it is the farmworkers who are picking the food, or whether it’s an MTA bus driver [is essential]” [40].

In addition to high levels of breadth of the perceived dirty work, illustrated with examples of proportion and centrality above, in this study, the depth of the pervasive stigma among essential service workers was also evident. According to Kreiner et al. (2006), depth refers to the extent to which workers in a pervasively stigmatized job conduct their jobs in close proximity to “dirt”, or work perceived by the Out-Group as dirty. Essential service workers revealed concerns over their direct proximity to people they encountered while doing their jobs, potentially infected with coronavirus, who feared going home and infecting their own families [3]. The Out-Group voiced similar fears and concerns over the proximity of essential service workers to the public, and recommended that people stay at home so as not to infect these workers [5].

4.3.2. Physically tainted occupations

Of the three types of taints attributed to high breadth and depth dirty occupations (i.e. physical, social, or moral taint), in this study, the data revealed essential service work as physically tainted (see Fig. 2 and Table 1). Consistent with Ashforth and Kreiner’s (1999) typology of tainted occupations, physical taint in this study exhibited essential service work conducted under dangerous conditions, possibly leading to death. For example, the daughter of an essential service worker explained that her father traveled very far to go to his job delivering food every day, and expressed her trepidation, “Each day he comes home feeling healthy, it feels like a blessing” [41]. Similarly, a member of the Out-Group observed,

“We are one of the states that has chicken processing plants. And so, we have already had four deaths at processing plants that will now likely balloon because they don’t have access to the adequate protections they need” [20].

Each of these examples depicting the serious danger of essential service workers in their jobs through the lens of pervasive stigma (breadth and depth), and the physical taint associated with their occupations, underscored the severity of the service work environment during COVID-19. Amidst the sickness and death reported on a regular basis, essential service workers came to realize the dangerous risk not only to their health, but also to the health of their families: “Every day we risk our health and the health of our family that await us at home’ [43], further demonstrating and illustrating the Dangerous Work theme.

4.4. Coping mechanisms

The second overarching theme identified in the data with a combined frequency of 381 coded segments was Coping Mechanisms, which was garnered through both deductive and inductive coding methods. Theoretically rooted in the dirty work literature, and based on the following constructs pertaining to In-Group and Out-Group perspectives: social identities (Kreiner et al., 2006), occupational stigmatized taints (Ashforth and Kreiner, 1999), and coping mechanisms (Bosmans et al., 2016; Kreiner et al., 2006) were applied in a deductive coding procedure, which uncovered the sub-theme: In-Group/Out-Group (106).

Upon a parallel inductive coding procedure, the sub-theme Call to Action: “Do Your Part!” (275) emerged as a cluster assigned to the Out-Group coping mechanism, a finding new to the literature (see Fig. 2 and Table 1). Although the clusters pertaining to Coping Mechanisms in Fig. 2 captured some coding from the ‘Identities’ and ‘Occupational Taint’ parent codes, the following discussion will focus solely on the majority of the codes captured under the ‘Coping’ parent code, from both the In-Group and Out-Group perspectives (see Appendix B for parent codes). Such findings are consistent with previous literature on In-group coping mechanisms among workers employed in stigmatized occupations (Kreiner et al., 2006). As this study is among the first to examine Out-group coping mechanisms, the findings are interpreted according to the extant occupational stigma literature.

4.4.1. In-group coping mechanisms

Coping mechanisms captured from the In-Group (i.e. essential service workers’) perspective were generated as a result of a deductive coding process, following a prescribed set of parent and sub-codes from the literature (Ashforth and Kreiner, 1999; Bosmans et al., 2016; Kreiner et al., 2006) (see Appendix B). The results from this study revealed social weighting (via In-Group favoritism) as the primary coping mechanism exhibited among the essential service workers’ discourse in the source documents. An example of In-Group favoritism included a retail worker who was fired for leading a protest over PPE and COVID-19 protection [2]. Reframing was another strategy of the In-Group as an occupational ideology coping mechanism, where essential service workers explained how their work was inspiring and the pleasure they experienced through the camaraderie they felt in their jobs [4]. This finding is also consistent with prior stigma research in the foodservice context, where the ability of workers to leverage internal service quality within their organization moderated stereotyping and stigma of service work (Wildes, 2007). Blaming was used by the In-Group as a defensive tactic, especially when referring to customers without masks, and the lack of pay associated with such dangerous, yet essential, service work [43]. Finally, the In-Group employed confronting/countering perceptions of the taint as a mechanism for coping, where essential service workers were envisioned as the lifeline to continuity in society [11] (see Table 1). These findings are consistent with prior research examining domestic service workers’ dirty work coping strategies via social weighting, including confronting/countering, reframing, In-Group favoritism, and blaming (Bosmans et al., 2016).

4.4.2. Out-group coping mechanisms

Coping mechanisms captured from the Out-Group (i.e. society or onlookers’) perspective were generated in the same manner as described with the In-Group coping mechanisms’ deductive coding process. With a focus solely on coping, the Out-Group favored confronting/countering perceptions for coping with their perceptions of essential workers’ hero status. For example, members from the Out-Group described how farmers were innovating ways to move their produce directly to consumers, illustrating the farmers’ and grocery store workers’ societal value in the food supply chain [8].

Selective social comparison as a social weighting tactic, was another Out-Group coping mechanism identified in this study. This tactic was framed in terms of societal class warfare in the U.S.:

“I'm tired of this 'essential worker' formulation, along with the soon-to-be-seen-as performative identification of media elites with grocery workers and delivery people. As a class, by definition, the working class is essential. So, I don't care much for invidious distinctions like 'essential' and 'not essential,' which are all too compliant with the liberal means-testing mentality, and their Lady Bountiful distinction between the deserving and the undeserving. Who cares if some poor [person] accidentally gets an extra grand in this society? What the 'essential workers' formulation conceals is that the correlation between 'essential' and wealth is often inverse. Who on earth would classify the Lords of Private Equity as essential? Or hedging? Or health insurance executives? All such should be given something useful to do, like delivering pizza or clearing bedpans.” [6]

Blaming and distracting as a defensive tactic, was a coping strategy identified among members of the Out-Group for dealing with essential workers’ new hero status. For example, members from the Out-Group blamed a lack of funding for critical PPE on the U.S. Government’s decision-making to “send billions of dollars in weapons overseas” during a televised memorial for those who died during Covid-10 in May 2020 [46].

Finally, reframing the perceptions of occupational roles of essential service workers was a coping mechanism used by the Out-Group (see Table 1). This notion was presented as an argument for better pay for essential service workers in the U.S. House of Representatives on May 25, 2020:

“The question is, should we rectify a situation where people are actually worse off financially for showing up in an essential job and should we recognize their willingness to put themselves at risk, which these individuals did, for two plus solid months with a very modest [paycheck]?” [42]

These findings new to the literature, while from the perspectives of the Out-Group, closely resemble key findings from a recent study examining sudden In-Group hero status among non-physician health care workers (Hennekam et al., 2020). Observations from that study contextualized In-Group hero status in terms of sudden “occupational visibility” by the Out-Group, who had previously taken In-Group service workers for granted (Hennekam et al., 2020). These findings are also consistent with prior research revealing how members of the Out-Group believed that sudden visibility bolstered by Out-Group accolades (via Out-Group social weighting coping mechanisms) should be appreciated and embraced by In-Group members (Mahalingam et al., 2019; Rabelo and Mahalingam, 2019).

4.4.3. Comparing in-group and out-group coping mechanisms

A finding new to the dirty work literature, the application of coping mechanisms for stigmatized work previously used to classify In-Group perspectives, in this study, was successfully applied to those perspectives of stigmatized essential service work from members of the Out-Group (i.e. society). Specifically, In-Group coping mechanisms in this study were adapted for the Out-Group perspective, and coded throughout the discourse from the source documents. As a comparison between the two groups regarding their preferred coping mechanisms for stigmatized essential service work during COVID-19, the data revealed the Out-Group’s coping mechanism was to broadcast out their support in a confronting/countering strategy (see Table 2 ). Extolling the value of essential service work during COVID-19 to change the perceptions and behaviors of other Out-Group members was in direct contrast to the In-Group’s preferred coping strategy, which was to extoll their own virtues within their own group as a form of social weighting. This finding is supported by recent “hero” research, demonstrating the ambivalence of service workers toward their new hero status, both accepting and rejecting simultaneously their sudden social valorization (Hennakam et al., 2020).

Table 2.

Comparison of Leading Coping Mechanisms to Stigmatized Essential Service Work During COVID-19 Between In-Group and Out-Group Members.

| In-Group | Out-Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social Weighting (13) | In-Group Favoritism | 1. Confronting/Countering (16) | Perception of Taint |

| Changing Behaviors | |||

| 2. Occ. Ideology (9) | Reframing | 2. Social Weighting (14) | Selective Social Comparison |

| 3. Defensive Tactics (7) | Blaming/Distracting | 3. Defensive Tactics (8) | Blaming/Distracting |

| 4. Confronting/Countering (3) | Perception of Taint | 4. Occ. Ideology (4) | Reframing |

Through another comparative lens of coping with the stigmatized work of essential service employees during COVID-19, in this study, another coping tendency of the Out-Group was to engage in a form of selective social comparison (comparing themselves as worse or better than those essential service workers) through social weighting. By comparison, the In-Groups’ second tendency in this study was to reframe their work inward with a positive value, affirming the meaning of their essential service duties. This finding was in alignment with a recent related study that demonstrated the Out-Group’s coping mechanisms for dirty task-related conditions of service workers as being worse by comparison. In the same study, the In-Group felt increased respect and recognition through their ‘essential’ status deemed by the Out-Group, and shared inward (Hennekam et al., 2020).

A finding of significance in this study was both groups’ use of defensive tactics as a third-place option from the coding frequencies, specifically blaming and distracting, as a coping mechanism for stigmatized essential service work during COVID-19. Both groups exhibited a tendency to blame “others” for not wearing masks [43], not funding PPE [21], perceived absence of testing [39], and employers allowing sick essential employees to work [21] in an effort to shift the blame of the dirty work from essential service workers to the “others” society deemed responsible.

Finally, a lesser, but fourth ranked coping mechanism according to frequency in the analysis, was the Out-Groups’ tendency for reframing, which was a second-ranked coping mechanism for the In-Group. The notion of deeming essential service workers as heroes perhaps held justification for the Out-Group to reframe the nature of essential service work during COVID-19 with a positive meaning. Similar to the Out-Groups’ predominant coping mechanism, the In-Group also coped by extolling the value of their essential work to others, justifying their value amidst stigmatized professions (see Table 2). These last two findings are supported by a recent study demonstrating a range of how the In-Group is comprised of non-homogenous sub-groups who cope with their own service workers hero status in a variety of ways. Extending this perspective to the Out-Group, the findings in this study demonstrate how the Out-Group (1) exhibited feelings of sudden importance of the In-Group brought on by hypervisibility; (2) increased displays of gratitude and consideration of the In-Group; (3) held feelings of ambivalence toward service workers’ new hero status; and (4) may have rejected the notion of service workers’ new hero status (Hennekam et al., 2020).

4.4.4. Call to action: “Do your part!”

The coping mechanism identified as Call to Action: Do Your Part!, emerged as a result of an inductive axial coding procedure, which utilized a combination of inductive and deductive decision-making, providing the ability to construct linkages in meaning (Strauss and Corbin, 1998), and offer insights and explanation as to the hero phenomenon under investigation (Fairclough, 1999). The following sub-codes materialized as a result of this procedure: Do Your Part! (77), Hope (56), Looking on the Bright Side (54), We are in this TOGETHER (44), and Educating (44), for a total of 275 codes, accounting for over half (57%) of the codes generated in the analysis (see Fig. 2).

Overall, the codes represented in this cluster included perspectives from both the In-Group and Out-Group, and also held a hopeful, positive message of working together in society toward a collective purpose. These codes did not reflect the work of essential service employees, but rather these codes focused on the external environment, which impacted the values of society. For example, the call to Do Your Part! by wearing masks [1], washing hands [1], staying home [2], and physically distancing [1], were messages early and continuous in the pandemic, and pervasive throughout the discourse. Other advice to Do Your Part! included not touching one’s face [13], practicing self-care [13], and calling the doctor if symptoms worsened [13]. A related component to Do Your Part!, was revealed in the sub-code, Educating. Due to the novelty of COVID-19, much about the virus was unknown, and reported in the discourse was the notion that the public needed to be patient, as we learned more together in society [2].

A Call to Action also offered hope, and a way to see the “bright side”. Hope manifested as Americans watched other countries, such as Italy, after combating rising infection numbers and deaths, how Italian society “flattened the curve” of newly reported infections [2]. Hope as a coping mechanism was also conveyed as new vaccines were being developed, and as new and effective steroid treatments became more well-known [4][24]. Even hydroxychloroquine, which was later disconfirmed as a treatment, did offer hope when first announced [10] (Geleris et al., 2020).

Looking on the Bright Side as a Call to Action manifested as balancing good news with bad. For example, news of stockpiling PPE, ventilators, hospital beds, and workers [5] in the external environment all helped the In- and Out-Groups to cope with the stigma of essential service work, and how support and positive messaging served to uplift these new heroes. Finally, the collective sense of We are in this TOGETHER, which permeated the discourse at the time, gave rise to the shared purpose of essential service workers. The social contract was such that if these essential workers agreed to serve the Out-Group by immersing themselves in stigmatized, dirty work, then the Out-Group would agree to convey messages assuring the safety and protection of essential service workers. Working TOGETHER, society agreed in the discourse that if the Out-Group stayed at home, used face masks, and followed the new social protocols in the pandemic, this would “buy time” to reduce the infection counts, work on a vaccine, and keep essential workers safe [2]:

“We are all in this together. Do it for yourself. Do it for your family. Do it for your community, and frankly, do it in memory of the likes of Kim and Bernard and Adam and Israel and everyone else we’ve lost. It's what we need to do, please.” [5]

5. Conclusion

The purpose of this research was to examine In-Group (i.e. essential service workers’) and Out-Group (i.e. society and others’) reactions and coping mechanisms to the new hero status of front-line essential service workers in the early wake of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Based on public discourse surrounding the shift to hero status, depth, breadth, and pervasiveness of physical stigma associated with essential service work has become especially salient in light of the pandemic. At the same time, as occupational outsiders were coping with their increased reliance on those doing this “dirty” work (i.e., service workers), occupational insiders were coping with the rapid changes in how they were viewed by society. The In-Group’s preferred coping strategy was to extoll their own virtues within their own group as a form of social weighting. Out-Group members primarily coped with this shift by extolling the value of essential service work during COVID-19 to change the perceptions and behaviors of other Out-Group members.

Perceived as a rare event in modern history, research generated from the COVID-19 pandemic since February 2020 is voluminous. The impacts of COVID-19 on social and economic losses cannot be underestimated, and is expected to precipitate global policy changes in both the short- and long-term (Verma and Gustafsson, 2020). Impacts on global business practices, supply chains, innovation and start-ups, global trade, technology, risk management, communication, etc. will all have long-term consequences on the hospitality and tourism industry devastated by inequities and job losses, which will continue to permeate intertwined social and economic relationships. All of these continuity of value issues justify a long-term research strategy across disciplines to untangle complex socio-economic issues for years to come (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020; Verma and Gustafsson, 2020).

5.1. Theoretical implications

The findings from this study offer theoretical implications, both in terms of a contribution to occupational stigma theory, and to critical discourse analysis as a methodology and framework for explicating a social phenomenon. The following sections explain further the contributions to theory.

5.1.1. Contribution to stigma research: out-group coping and radical shifts in Stigma

Despite the fact that members from the Out-Group were the source of occupational stigma prior to COVID-19, past research has not examined how Out-Group members cope with the occupational stigma they impose on others. As a coping mechanism new to the Out-Groups’ reaction to stigmatized dirty work broadly, and as an added sub-construct, specifically, this study revealed an outward tactic new to the literature: A Call to Action: Do Your Part!. This tactic is distinct from: (1) attempting to change outsiders’ perceptions of the dirty work (i.e. confronting/countering); (2) conferring positive meaning to essential service dirty work (i.e. reframing/recalibrating/refocusing); (3) engaging in social weighting via comparisons to favorable or unfavorable sub-groups; and (4) using defensive tactics to blame, distance, or to avoid the dirt associated with essential service work during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although conceptual frameworks of stigma do acknowledge its dynamic nature, the essential service workers’ tasks were framed as the predictor of a shift, as in the case of compartmentalized stigma, (Kreiner et al., 2006). The results of this study highlight that events external to the job, particularly events experienced on a large scale with shared meaning among In-Group and Out-Group members, should also be incorporated into occupational stigma models as a predictor of a dynamic shift in stigma.

5.1.2. CDA methodology and framework for capturing social phenomena

This work also highlighted the utility of critical discourse analysis as a tool for researchers in the services industries discipline. A micro-auto-ethnographic analysis of research published in a hospitality journal revealed a variety of quantitative and qualitative approaches leveraged within the discipline, yet critical discourse analysis had not been utilized to the same degree (Ryan, 2015). A large body of popular press and other narratives about the hospitality industry represents a unique opportunity to systematically analyze what is said about the services industries, in addition to existing quantitative and qualitative methodologies. This tool will allow hospitality and tourism researchers to better account for societal influences on the subject of research (Ryan, 2015) and to triangulate existing methods with “context-laden” approaches (Downward and Mearman, 2004, p.117).

5.2. Practical implications

The practical implications of this research are many, particularly as it pertains to advocacy on behalf of those working in the hospitality and services industries. This study’s findings, related to the pervasive stigma and exposure to dangerous work, bear practical implications regarding advocacy for employees in stigmatized conditions. As evidenced by the results, COVID-19 served as an event where, at least for a short time, both In-Group and Out-Group members recognized the value and shortfalls in current protections for essential stigmatized workers.

Essential services, such as transportation, grocery, food preparation, and delivery, all bolster the undercurrents of society, with or without a pandemic. Prior to COVID-19, inequities existed for service workers, which included low pay, lack of health insurance, and a lack of ancillary services (such as daycare) to support full-time line-level service workers. The pandemic has been said to reveal to a fuller extent to which these societal inequities already existed, and their collective consequences on a society so dependent on them (Grassani, 2020). The impacts of these inequities have an inverse effect, in that the more inequity (i.e. less pay, etc.) that exists, the more adversely impacted service workers will be affected, the effects exacerbated by the pandemic (Grassani, 2020). In terms of direct managerial implications offered in prior research, managers in the services industries play a complex role in that they must shield workers from the same threats they face themselves (Ashforth et al., 2007). Strategies for shielding service workers on the job have included the use of humor, counter-stereotypical behavior, and quiet resistance (Ashforth et al., 2007). Demonstrating and developing confidence in service roles is also a productive strategy toward mitigating stigma in a service industry role (Graham et al., 2020).

The accolade of “hero” on essential service workers during COVID-19, according to this study, holds little value for the In-Group, unless and until the Out-Group agrees to the value of the (dirty) service work. In modern news cycles, important stories rise and fall, such as the Black Lives Matter marches for equality, which moved to the front of the news cycle in the midst of the pandemic, revealing the complexity of interlocking social disparities. It will be incumbent on unions, associations, and advocacy groups to keep alive the story of the essential service worker “heroes”. More importantly, it will be critical for members of the Out-Group to remain engaged, and who will be needed in large numbers to advocate for the In-Group with the same veracity they extolled the virtues of service work at the beginning of the pandemic. The continuance of the “We are in this TOGETHER” outward messaging in the public discourse should be championed in a capacity that advocacy groups can summon. We call on professional associations, advocacy groups, and those involved in public policymaking to ensure that this sudden recognition of heroes translates to advocacy and public policy to protect the safety, health, and livelihoods of those service employees. Without such action, this new hero status may be nothing more than fleeting, empty words of gratitude. In fact, a recent commentary on COVID-19 public health structural inequalities assert that expressions of gratitude and unity without accompanying policy reform are nothing more than “another hollow platitude of solidarity designed to placate the privileged and temporarily uncomfortable and inconvenienced” (Bowleg, 2020, p.917).

5.3. Strengths, limitations, and future research

This study was strengthened by its foundation in theory, applying a well-understood and impactful perspective from the behavioral sciences, to a current social phenomenon in the services industries. This study was also strengthened by a thorough and meticulous methodology, as vetted by a professional in library sciences, ensuring that the data collected were representative of shared societal discourse, rather than discourse specific to a particular ideology, group, or source. This study’s novel perspective and methodology spurs a number of opportunities for future research, such as research employing quantitative methods to examine In-Group and Out-Group phenomenon and explanatory mechanisms for the relationship between stigma and coping, interventions to aid in advocacy, or evaluations of advocacy and public policy methods regarding the safety of stigmatized service workers.

This study was subject to limitations. Due to the extenuating circumstances of not being able to collect interview data at the beginning of the pandemic, the researchers in this study used news sources as data. This provided important insight into the societal discourse shaping how essential service work was being viewed. Future qualitative research should include a series of interviews collected among a variety of essential service workers. Future research should consider collecting longitudinal data, to follow changes in In-Group and Out-Group perspectives over time. Future studies should also incorporate healthcare workers by comparison, for greater generalizability of the “hero” effect and its impacts on society.

This study included 46 news sources, which may not have revealed all nuances in the data. Future research should examine more news sources and could develop an exacting Out-Group Call to Action construct. This study was limited to news sources in the United States, and as the pandemic is a global emergency, future research should be conducted internationally, with a focus on cultural approaches to In-Group and Out-Group perspectives on stigmatized occupations, particularly in the services industries. A comparison of In-Group and Out-Group features in the collectivist and individualistic contexts should yield more generalizable findings.

Funding statement

This study was supported by grant number T42OH008438, funded by the National Institute Occupational Safety (NIOSH) and Health under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIOSH or CDC or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102772.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Adib A., Guerrier Y. The interlocking of gender with nationality, race, ethnicity and class: the narratives of women in hotel work. Gend. Work Organ. 2003;10(4):413–432. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth B.E., Kreiner G.E. “How can you do it?” Dirty work and the challenge of constructing a positive identity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999;24(3):413–434. doi: 10.5465/amr.1999.2202129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth B.E., Kreiner G.E. Dirty work and dirtier work: differences in countering physical, social and moral stigma. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2014;10(1):81–108. doi: 10.1111/more.12044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth B.E., Kreiner G.E., Clark M.A., Fugate M. Normalizing dirty work: managerial tactics for countering occupational taint. Acad. Manag. J. 2007;50(1):149–174. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth B.E., Harrison S.H., Corley K.G. Identification in organizations: an examination of four fundamental questions. J. Manage. 2008;34(3):325–374. doi: 10.1177/0149206308316059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth B.E., Kreiner G.E., Clark M.A., Fugate M. Congruence work in stigmatized occupations: a managerial lens on employee fit with dirty work. J. Organ. Behav. 2017;38(8):1260–1279. [Google Scholar]

- Baker M.G., Peckham T.K., Seixas N.S. Estimating the burden of United States workers exposed to infection or disease: a key factor in containing risk of COVID-19 infection. PLoS One. 2020;15(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickmeier R.M., Lopina E.C., Rogelberg S.G. In: Well-Being and Performance at Work: The Role of Context. van Veldhoven M., Peccei R., editors. Psychology Press; 2015. Well-being and performance in the context of dirty work; pp. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bosmans K., Mousaid S., De Cuyper N., Hardonk S., Louckx F., Vanroelen C. Dirty work, dirtier work? Stigmatisation and coping strategies among domestic workers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016;92:54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. We’re not all in this together: on COVID-19, intersectionality, and structural inequity. Am. J. Public Health. 2020;110(July (7)):917. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogan K.F. The Atlantic. 2020. Calling me a hero only makes you feel better: I work in a grocery store. All this grandiose praise rings insincere.https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/i-work-grocery-store-dont-call-me-hero/610147/ [Online]. April 18, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Caza B.B., Vough H., Puranik H. Identity work in organizations and occupations: definitions, theories, and pathways forward. J. Organ. Behav. 2018;39(7):889–910. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell J.W., Miller D.L. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Pract. 2000;39(3):124–130. [Google Scholar]

- David H., Dorn D. The growth of low-skill service jobs and the polarization of the US labor market. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013;103(5):1553–1597. [Google Scholar]

- Downward P., Mearman A. On tourism and hospitality management research: a critical realist proposal. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2004;1(2):107–122. doi: 10.1080/1479053042000251106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duemmler K., Caprani I. Identity strategies in light of a low-prestige occupation: the case of retail apprentices. J. Educ. Work. 2017;30(4):339–352. doi: 10.1080/13639080.2016.1221501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough N. vol. 10. Polity Press; 1992. (Discourse and Social Change). [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough N. The Routledge Handbook of Critical Discourse Studies. Routledge; 2017. CDA as dialectical reasoning; pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenthal E. Heroes of the front lines. TIME Magazine. 2020 https://time.com/collection/coronavirus-heroes/5816805/coronavirus-front-line-workers-issue/ April 9. [Google Scholar]

- Gavi . Gavi the Vaccine Alliance. 2020. How does COVID-19 compare to past pandemics? [Online]. Retrieved from https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/how-does-covid-19-compare-past-pandemics, June 1. [Google Scholar]

- Geleris J., Sun Y., Platt J., Zucker J., Baldwin M., Hripcsak G., et al. Observational study of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2411–2418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson D.A. On-property hotel financial controllers: a discourse analysis approach to characterizing behavioural roles. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2002;21(1):5–23. doi: 10.1016/S0278-4319(01)00018-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham D., Ali A., Tajeddini K. Open kitchens: customers’ influence on chefs’ working practices. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020;45:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Grassani A. The New York Times. 2020. As coronavirus deepens inequality, inequality worsens its spread.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/15/world/europe/coronavirus-inequality.html [Online]. March 15, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Guasti N. The plight of essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10237):1587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31200-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hällgren M., Rouleau L., de Rond M. A matter of life or death: how extreme context research matters for management and organization studies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2018;12(1):111–153. doi: 10.5465/annals.2016.0017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hennekam S., Ladge J., Shymko Y. From zero to hero: an exploratory study examining sudden hero status among nonphysician health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020;105(10):1088–1100. doi: 10.1037/apl0000832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Desbiolles F. Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg M.A., Terry D.J. Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000;25(1):121–140. doi: 10.5465/amr.2000.2791606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hulin C.L. In: The Psychology of Work: Theoretically Based Empirical Research. Brett J.M., Drasgow F., editors. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2002. Lessons from industrial and organizational psychology; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatova E. Where have all the people gone?: a multimodal critical discourse study of the representation of people in promotional tourism discourse. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2020;20(2-3):129–139. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization [ILO] International Labour Organization; 2019. Rules of the Game: an Introduction to the Standards-related Work of the International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Janks H. Critical discourse analysis as a research tool. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 1997;18(3):329–342. doi: 10.1080/0159630970180302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrough L. Mongabay: News & Inspiration from Nature’s Frontline. 2020. Field research, interrupted: how the COVID-19 crisis is stalling science.https://news.mongabay.com/2020/04/field-research-interrupted-how-the-covid-19-crisis-is-stalling-science/ [Online]. April 9, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner G.E., Ashforth B.E., Sluss D.M. Identity dynamics in occupational dirty work: integrating social identity and system justification perspectives. Organ. Sci. 2006;17(5):619–636. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1060.0208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz U., Radiker S. Springer Nature; 2019. Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA: Text, Audio, and Video. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.H., Hilton D.J. How the past weighs on the present: social representations of history and their role in identity politics. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005;44(4):537–556. doi: 10.1348/014466605X27162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalingam R., Jagannathan S., Selvaraj P. Decasticization, dignity, and ‘dirty work’ at the intersections of caste, memory, and disaster. Bus. Ethics Q. 2019;29(2):213–239. [Google Scholar]

- Meisenbach R. Stigma management communication: a theory and agenda for applied research on how individuals manage moments of stigmatized identity. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2010;38(3):268–292. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2010.490841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolon S., Alavi S., Reynders A. The Catch-22 of countering a moral occupational stigma in employee-customer interactions. Acad. Manag. J. 2020 doi: 10.5465/amj.2018.1487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney S.K., Harris C., Ryan I. Long hospitality careers–a contradiction in terms? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2016;28(11):2589–2608. [Google Scholar]

- Nimri R., Kensbock S., Bailey J., Jennings G., Patiar A. Realizing dignity in housekeeping work: evidence of five-star hotels. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2020;19(3):1–20. doi: 10.1080/15332845.2020.1737770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phung K., Buchanan S., Toubiana M., Ruebottom T., Turchick‐Hakak L. When stigma doesn’t transfer: stigma deflection and occupational stratification in the sharing economy. J. Manag. Stud. 2020 doi: 10.1111/joms.12574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Powell P.H., Watson D. Service unseen: the hotel room attendant at work. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006;25(2):297–312. [Google Scholar]

- Rabelo V.C., Mahalingam R. They really don’t want to see us: how cleaners experience invisible ‘dirty’ work. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019;113:103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ravenelle A.J. Univ of California Press; 2019. Hustle and Gig: Struggling and Surviving in the Sharing Economy. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson R.N.S., Kralj A., Solnet D.J., Goh E., Callan V.J. Attitudinal similarities and differences of hotel frontline occupations. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2016;28(5):1051–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers K. FiveThirtyEight. 2020. Why did the world shut down for COVID-19 but not ebola, SARS, or swine flu?https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/why-did-the-world-shut-down-for-covid-19-but-not-ebola-sars-or-swine-flu/ [Online]. April 14, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C. Trends in hospitality management research: a personal reflection. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2015;27(3):340–361. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-12-2013-0544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selyukh A. NPR. 2020. As ‘hero’ pay ends, essential workers wonder what they are worth.https://www.npr.org/2020/05/30/864477016/as-hero-pay-ends-essential-workers-wonder-what-they-are-worth [Online]. May 30, Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman D.S. American Scientist. 2020. Data collection during social distancing.https://www.americanscientist.org/blog/macroscope/data-collection-during-social-distancing [Online]. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Shigihara A.M. “(Not) forever talk”: restaurant employees managing occupational stigma consciousness. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. Int. J. 2018;13(4):384–402. doi: 10.1108/QROM-12-2016-1464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Small J., Harris C., Wilson E. A critical discourse analysis of in-flight magazine advertisements: the ‘Social Sorting’ of airline travellers? J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2008;6(1):17–38. doi: 10.1080/14766820802140422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) SHRM. 2020. Service and retail workers emerge as heroes: are those industries forever changed by the COVID-19 pandemic?https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/all-things-work/pages/coronavirus-impact-on-service-and-retail-industries.aspx [Online]. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Spears R., Jetten J., Doosje B. In: The Psychology of Legitimacy: Emerging Perspectives on Ideology, Justice, and Intergroup Relations. Jost J.T., Major B., editors. Cambridge University Press; 2001. The (il)legitimacy of in-group bias: from social reality to social resistance; pp. 332–362. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A.L., Corbin J.M. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. [Google Scholar]

- Summers J.K., Howe M., McElroy J.C., Ronald Buckley M., Pahng P., Cortes‐Mejia S. A typology of stigma within organizations: access and treatment effects. J. Organ. Behav. 2018;39(7):853–868. doi: 10.1002/job.2279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H. In: Differentiation Between Social Groups. Tajfel H., editor. Academic Press; 1978. Interindividual behavior and intergroup behavior; pp. 27–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H. In: Differentiation Between Social Groups. Tajfel H., editor. Academic Press; 1978. Social categorization, social identity and social comparison; pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H., Turner J.C. In: Psychology of Intergroup Relations. 2nd ed. Worchel S., Austin W.G., editors. Nelson Hall; 1986. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D.B. The New York Times. 2020. How the coronavirus pandemic unfolded: a timeline.https://www.nytimes.com/article/coronavirus-timeline.html [Online]. June 9 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- The New York Times . New York Times. 2020. See how all 50 states are reopening (and closing again)https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/states-reopen-map-coronavirus.html [Online Interactive]. October 9 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (U.S. BLS) U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2020. Economic News Release: Employment Situation.https://www.bls.gov/cps/employment-situation-covid19-faq-march-2020.pdf [Online]. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]