Abstract

This research note reports the results of a qualitative study exploring front-line hotel employees’ views about working during the COVID-19 pandemic in order to identify factors that may influence their ability and willingness to report to work. Findings from online focus-groups reveal that front-line hotel employees generally felt a sense of duty to work during the pandemic. However, there were also a number of perceived barriers to working that impacted on this sense of duty. These emerged as barriers to ability and barriers to willingness, but the distinction is not clear-cut. Instead, most barriers seem to form a continuum ranging from negotiable barriers to insuperable barriers. Following this coneptualisation, the key to reducing absenteeism during the pandemic is likely to take remedial action so that barriers to willingness do not become perceived as barriers to ability to work. Practical implications towards this direction are offered.

Keyword: COVID-19, Pandemic, Crisis, Hotel employees, Absenteeism, Willingness to work

1. Introduction

A pandemic crisis has the potential to influence the number of employees who report to work. Absenteeism in a pandemic situation is directly affected by two important variables: an employee’s (un)willingness to show up for work, and an employee’s ability to report to duty. In this context, “ability refers to the capability of the individual to report to work, whereas willingness refers to a personal decision to report to work” (Qureshi et al., 2005: 379). Studies from healthcare services and the general population suggest that absenteeism rates may be significant when fear of becoming infected with novel agents is high, ranging respectively from ∼35 % to 55 % (Chafee, 2009) and from 50 % to 80 % (Teh et al., 2012). Pandemic-related absenteeism resulting from a lack of willingness and ability to work could, therefore, lead to severe workforce shortages.

From a hospitality management perspective, the high costs associated with absenteeism suggest that it is imperative to understand this phenomenon (Karatepe et al., 2020). This is particularly so during pandemics, when absenteeism might be heightened by infected employees and those staying away from work by fear of contamination (Verikios et al., 2016). Pandemic-induced absenteeism, nonetheless, is under-researched within tourism and hospitality crisis management. Existing studies (e.g., Novelli et al., 2018; Page et al., 2012) focus on pandemic preparedness/response plans and impact assessments and are conducted at the destination and sectoral levels. Thereby, they overlook individual crisis stakeholders such as employees and their views and experiences during actual situations. This gap is surprising considering that when a pandemic occurs hospitality employees are exposed to health/safety risks while, simultaneously, sharing the responsibility for carrying out crisis response tasks (Hu et al., 2020). This is particularly relevant for front-line hotel employees who are exposed to infectious diseases through frequent contact with customers (Hannerz et al., 2002). To address this gap, we conducted a pandemic-related study on front-line hotel employees’ ability and willingness to work. The study took place during the early unfolding of COVID-19 in Greece.

2. Methodology

Focus groups were chosen to explore front-line hotel employees’ views, in order to identify factors that may influence their ability and willingness to report to duty during the COVID-19 pandemic. Focus groups are appropriate for exploratory research into under-investigated topics, where the emphasis is on exploring people’s opinions, experiences and concerns (Kitzinger and Barbour, 1999) and, therefore, well-suited to the nature of this study.

2.1. Sample

Postgraduate tourism management students from the Hellenic Open University were selected as respondents. These are not a typical student population as they are adult students (over the age of 24), most of whom work in the hospitality industry. As such, they offered an easily accessible segment of the hospitality labour market. The ethics committee of the university granted approval for this study with the requirements of obtaining consent from each participant and collecting limited demographics to maintain participant confidentiality. Following this, respondents were recruited using invitations released through official University email accounts. Asynchronous email communication was established, during which the first author provided details about the study, a link to an online consent form, and screened potential participants for study eligibility, i.e. they were front-line hotel employees (thus they had direct experience of the topic being researched). Eligible participants who signed the consent form were entered in a database. The intent of a focus group is to explore the views of individuals, not to generalize to wider groups (Kitzinger and Barbour, 1999). In addition, a valid sample in qualitative research should be based on information-rich respondents to discover a wide range of perspectives (Patton, 2005). Accordingly, participants were purposively selected from this database with the sample including a wide range of job positions, age, gender and seniority as possible to ensure a variety of answers and perspectives. The sample consisted of 32 participants; 19 male and 13 female. Fifteen were married and 7 were living with a partner, the remaining being single. The sample had an overall mean age of 36.4 years and a mean seniority level of 8.1 years. The selected participants had customer contact responsibilities in three key operational hotel departments: front-office (47 %), F&B service (34 %) and housekeeping (19 %). All participants were working full-time. No further demographics were collected.

2.2. Design

Four focus-group sessions were planned with a total of 32 participants, each focus group with eight participants. Participants were assigned to focus groups based on their availability. All sessions were moderated by both researchers and completed in real-time over a web-conferencing service to adhere to social distancing recommendations issued by health authorities. Focus groups started by asking participants about the effect they anticipated the pandemic to have on their professional life. Participants were asked whether they thought front-line hotel employees had a professional duty to work; how likely they were to report to work if in good health; and if they felt they would be able and/or willing to report to work as usual. The focus groups lasted approximately 90 min and were video-recorded and transcribed. Data collection took place during the first two weeks of March 2020. At that time, the number of COVID-19 patients in Greece remained low in comparison to other countries, reaching 331 confirmed cases as of March 15 (Worldometer, 2020). On March 10 the operation of all schools and universities was suspended nationwide. Hotels closed down on March 22, which was not known at the time of the research.

2.3. Data analysis

Data were analysed manually by both authors independently, through thematic analysis using the steps documented by Gioia et al. (2013). In the first round, the transcripts were read carefully to identify key themes. Then, a second round of coding was performed in order to group emerging topics into interrelated themes by copying, reorganising and comparing thematic categories. Last, in the third round of coding sub-categories were combined with the key themes initially identified to refine and further develop the thematic categories. Following this stage, both authors met to discuss individual analyses. Both analysts identified a similar constellation of themes and agreed that the coding framework was easy to interpret and use. Notwithstanding scepticism about the value of such testing in the context of qualitative thematic analysis (O’Connor and Joffe, 2020), we assessed the agreement between coders using Miles and Huberman, 1994 percentage agreement approach. Percentage agreement is a suitable index when the coding task is easy and the data is straightforward (Feng, 2014). Agreement between coders was 88 %, providing further confidence that the thematic structure represented a credible account of the data. Discrepancies (12 %) were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

3. Findings

Given the nature of qualitative inquiry we present our findings by describing themes that emerged out of the group process. The emphasis is on what was said rather than how often it was said. What percentages are offered are therefore given solely to provide the reader with an impression of the salience of the themes discussed.

3.1. Professional duty

The majority of participants tended to believe that they should, and would, continue to work through the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a prevailing view that they had a duty to work and that not reporting to work would be morally wrong. This sense of duty was justified on different grounds. Most were motivated by a sense of professional obligation (44 %), some by feelings of collegiality (19 %) and a few others by a simple work ethic that absenteeism, if one is able to work, is wrong (9%). The extracts below exemplify such views:

“As a hospitality professional it is my obligation to come to work if I am able to” [female, 30, receptionist]

“I like to think of myself as part of a larger team. If I don’t show up for work I am letting my team down” [male, 41, concierge]

“If one is fit and well they should come to work. You don’t just work when everything is okay” [male, 27, restaurant captain]

3.2. Transport to work

There were, nonetheless, a number of factors that impacted on this sense of duty, emerging as barriers to ability and willingness to report to work. However, lines between these categories were often blurred. Indeed, the only concrete barrier to ability was becoming infectious. Informants also expressed concerns that if the pandemic was to escalate in the country, they would be unwilling to use public transport for fear of becoming infected during the commute (41 %). Others had already refrained from doing so, walking or using private cars to get to work. In this context, lack of motorised transportation for those living a long distance from work was perceived as a barrier of ability to report to work (25 %).

3.3. Family obligations

One prominent concern was family obligations. For many informants, it was important to strongly state that ‘family comes first’. This was expressed as a pre-defined moral premise rather than a choice of weighing up competing obligations (47 %); therefore, acting as a barrier to ability to report to work. As an informant [male, 29, waiter] put it, “if a family member needs me, I will not be able to go to work”. The presence of dependents living at home was also raised by some participants as an insurmountable obstacle (22 %), due to unavailability of externally accessible/available care. For example, “with the schools closed down and no one to look after my children I had to ask for a leave of absence” [female, 32, assistant housekeeping manager]. For others (38 %), child/eldercare functioned as a barrier to willingness to work, where personal choice prioritised family over work (e.g. available care was regarded inadequate) or one was able to work because they relied on available others.

3.4. Risk to self/family

Concern about becoming infected and taking the virus home to one’s family was also a recurrent theme, with risk to self being less pronounced except by few participants (16 %) for whom “high personal risk justifies absenteeism” [female, 27, waitress]. Generally, though, such concerns were not perceived as a barrier to ability to report to work with participants believing that, if needed, they would be in a position to moderate the risk by employing infection control measures (53 %). In this regard, some informants (31 %) stressed the importance of being provided with protective equipment in their workplace if national guidance recommends their use.

3.5. Lack of pandemic planning

A further connected issue was the absence of guidance from their employer about COVID-19, suggesting a lack of pandemic planning. The majority of participants (56 %) said they had been given no training about the correct use of equipment and other precautions nor were made aware of what would be expected from them, were the crisis to escalate. This gave them the impression that their employer does not care about their needs. For many respondents (44 %), this lack of guidance represented an important barrier to their willingness to work: “why should I risk my health if I don’t have necessary information?” [female, 38, restaurant hostess].

3.6. Erosion of goodwill

For some participants (34 %), this perceived indifference was also connected to a general deterioration of goodwill in their employer as a result of perceived unfavourable working conditions. This raised the question of whether employees with such negative perceptions would go to work if they thought they would be risking themselves. Commenting on this issue, however, most participants (63 %) expressed their belief that their sense of duty will prevail but expected that some of their colleagues may not feel the same way. As an informant aptly put it, “it is a different decision for everybody depending on who they are and the circumstances each faces” [male, 44, front office manager].

4. Conclusion and implications

To the best of our knowledge this is the first study to investigate barriers to working among front-line hotel employees that may cause significant shortage in hotel workforce at times of pandemic crises. In the absence of relevant hospitality studies, we used the concepts of ability and willingness to work, raised in healthcare research. These concepts proved particularly useful in framing our investigation, as it became apparent that our data fitted well into these categories, providing structure into a complex phenomenon. On this view, this study has integrated perspectives from the healthcare literature to reveal theoretical and practical insights for the hospitality industry. As such, it responds to the recent call by Wen et al. (2020) for more pandemic-related interdisciplinary research between tourism/hospitality and the health sciences.

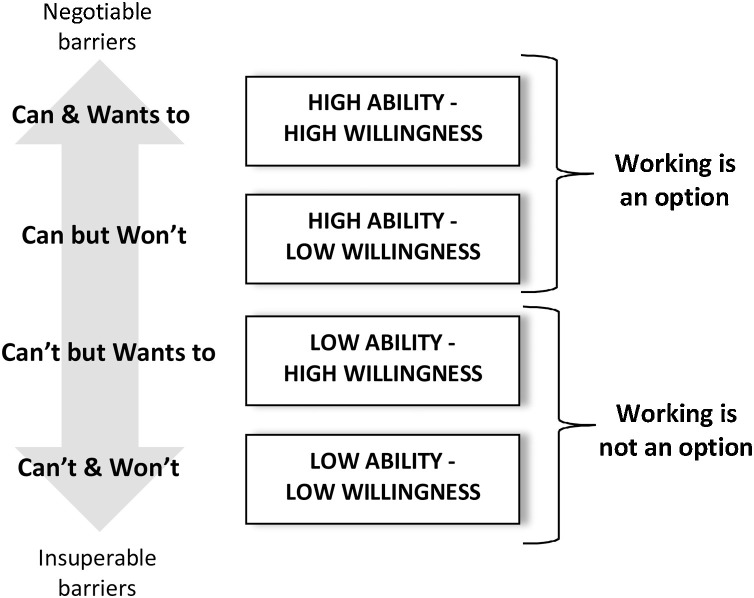

Our study findings suggest that the identified barriers can function as either barriers to ability or willingness to report to work but the distinction is not clear-cut. From a theoretical perspective and drawing from Ives et al. (2009), most barriers can therefore be conceptualised as forming a continuum ranging from negotiable to insuperable barriers, with increasingly harder choices in-between (see Fig. 1 ). Following this conceptualisation, the more difficult the choice to be made, the more likely it is to be perceived as a barrier to ability to report to work. For example, using reliable private childcare will be easier for those able to afford it but harder, or even impossible, for those less well-placed to do so. In the latter case, childcare is likely to be perceived as a barrier to ability to report to work. At the same time, what counts as ‘affordable’ and ‘reliable’ may owe as much to personal preference or choice as to insurmountable circumstances. A decision to report to work or not, then, is likely to differ for each individual resulting from a combination of personal beliefs/circumstances and external constraints, which interact with barriers to work. Accordingly, as can be seen in Fig. 1, this combination may result in different perceptions of one’s ability and willingness to work during a pandemic.

Fig. 1.

Pandemic-related absenteeism in hotel employees.

From a practical point of view, the challenge for hotel management, then, appears to be one of taking remedial action so that barriers to willingness to work are not perceived as barriers to ability to work, thus making reporting to work a realistic option. This study suggests a number of remedial measures that may achieve this. If transportation is an issue of concern, measures might be taken to facilitate transport for employees. Likewise, in order to increase employee willingness to report to work, measures for infection controls in customer areas and training the employees working in these areas to protect themselves and their families from infection should be taken. Efforts should also be made to develop a policy of communication between the organisation and its employees, encouraging the feeling that the needs of employees are acknowledged. Drawing from previous work on the healthcare sector (Garrett et al., 2009; Martin, 2011), providing for the care of those who do become ill and helping employees meet their family obligations is likely to contribute towards this direction.

The researchers would like to note that the findings are based on a convenience and well-educated student sample, which may not be the best representation of hotel employees in Greece. Therefore, the reported results should be treated with caution and further research is needed to determine which of the barriers identified here prove to be the most significant among hotel employees. This study serves to illustrate, however, that it would be valuable for hotel management to understand the barriers faced by its own employees. Such understanding would facilitate management efforts to develop a tailored strategy to mitigate pandemic-related absenteeism. The key to achieving this is likely to be taking remedial steps so that when barriers emerge, they are experienced as ones related to willingness to work, which are more negotiable than barriers to ability. If people feel they have a choice to go to work, other factors such as sense of duty or the knowledge they will be supported may provide the motivation to make this choice in favour of working.

References

- Chafee M. Willingness of health care personnel to work in a disaster: an integrative review of the literature. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2009;3(1):42–56. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e31818e8934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G.C. Intercoder reliability indices: disuse, misuse, and abuse. Qual. Quant. 2014;48:1803–1815. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett A.L., Park Y.S., Redlener I. Mitigating absenteeism in hospital workers during a pandemic. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2009;3(2):S141–S147. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181c12959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioia D.A., Corley K., Hamilton A.L. Seeking qualitative rigour in inductive research. Organ. Res. Methods. 2013;16(1):15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hannerz H., Tüchsen F., Kristensen T.S. Hospitalisations among employees in the Danish hotel and restaurant industry. Eur. J. Public Health. 2002;12(3):192–197. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/12.3.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Yan H., Casey T., Wu C.H. Creating a safe haven during the crisis: how organisations can achieve deep compliance with COVID-19 safety measures in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020:102662. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102662. Published online: 29 August 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ives J., Greenfield S., Parry J.M., Draper H., Gratus C., Petts J.I., Sorrell T., Wilson T. Healthcare workers’ attitudes to working during pandemic influenza. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(56):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe O.M., Rezapouraghdam H., Hassannia R. Job insecurity, work engagement and their effects on hotel employees’ non-green and nonattendance behaviors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020;87 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger J., Barbour R.S. In: Developing Focus Group Research: Politics, Theory and Practice. Barbour R.S., Kitzinger J., editors. Sage; London: 1999. Introduction: the challenge and promise of focus groups; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Martin S. Nurses’ ability and willingness to work during pandemic flu. J. Nurs. Manag. 2011;19(1):98–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M.B., Huberman A.M. 2nd edition. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Source Book. [Google Scholar]

- Novelli M., Burgess L.G., Jones A., Ritchie B.W. No Ebola…still doomed’ – the Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018;70:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor C., Joffe H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2020;19:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Page S., Song H., Wu D.C. Assessing the impacts of the global economic crisis and swine flu on inbound tourism demand in the United Kingdom. J. Travel. Res. 2012;51(2):142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. 4th edition. Sage; London: 2005. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi K., Gershon R., Sherman M., Straub T., Gebbie E., McCollum M., Erwin M., Morse S. Healthcare worker’s ability and willingness to report to duty during catastrophic disasters. J. Urban Health. 2005;82(3):378–388. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teh B., Olsen K., Black J., Cheng A.C., Aboltins C., Bull K., Johnson P.D.R., Grayson M.L., Torresi J. Impact of swine influenza and quarantine measures on patients and households during the H1N1/09 pandemic. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2012;44(4):289–296. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2011.631572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verikios G., Sullivan M., Stojanovski P., Giesecke J., Woo G. Assessing regional risks from pandemic influenza. World Econ. 2016;39(8):1225–1255. [Google Scholar]

- Wen J., Wang W., Kozak M., Liu X., Hou H. Many brains are better than one: the importance of interdisciplinary studies on COVID-19 in and beyond tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020 Published online: 13 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Worldometer . Greece; 2020. Woldometer’s COVID-19 Data. Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/greece/ [accessed 09/05/2020]. [Google Scholar]