Visual Abstract

Key Words: atherosclerosis, liraglutide, molecular imaging, ultrasound

Abbreviations and Acronyms: ApoE, apolipoprotein E; CEUMI, contrast-enhanced ultrasound molecular imaging; CVD, cardiovascular disease; GLP, glucagon-like peptide; GLP-1R, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor; GLP-1RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ICAM, intercellular cell adhesion molecule; IL, interleukin; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MB, microbubble; MBCtr, control microbubbles; MBVCAM-1, microbubbles targeted to VCAM; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; OPN, osteopontin; TG, triglycerides; TGRL, triglyceride-rich lipoproteins; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule; VLDL-C, very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Highlights

-

•

Treatment with the GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide reduces major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes mellitus.

-

•

In Apo E−/− mice on high fat diet, contrast enhanced ultrasound molecular imaging with a microbubble contrast agent targeted to endothelial VCAM-1 showed a signal increase vs nontargeted microbubbles in vehicle-treated animals, but not in animals on liraglutide.

-

•

Together with a reduction in plaque burden, TNF-α, IL-1β, MCP-1, and OPN, this indicates a reduction in vascular endothelial inflammation as a result of liraglutide treatment. This effect did not depend on glucose levels, because HbA1c was unchanged.

Summary

The authors determined the effect of the GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide on endothelial surface expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 in murine apolipoprotein E knockout atherosclerosis. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound molecular imaging using microbubbles targeted to VCAM-1 and control microbubbles showed a 3-fold increase in endothelial surface VCAM-1 signal in vehicle-treated animals, whereas in the liraglutide-treated animals the signal ratio remained around 1 throughout the study. Liraglutide had no influence on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol or glycated hemoglobin, but reduced TNF-α, IL-1β, MCP-1, and OPN. Aortic plaque lesion area and luminal VCAM-1 expression on immunohistology were reduced under liraglutide treatment.

About 18 million people die every year from cardiovascular diseases (CVD), and 85% of these deaths are due to myocardial infarction or stroke associated with atherosclerosis. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is one of the most important risk factors for the development of CVD.1 In the LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes) and SUSTAIN-6 (Trial to Evaluate Cardiovascular and Other Long-term Outcomes With Semaglutide in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes) trials, both large randomized clinical studies, the glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) liraglutide and semaglutide decreased death from cardiovascular causes, myocardial infarction, and stroke.2,3 However, the effect of GLP-1RA on glucose control in these trials was small, and the reductions in cardiovascular outcomes were not related to glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels. Together with a significant treatment effect in the subgroup of patients with established CVD in the LEADER trial, this suggests an effect of GLP-1RAs on atherosclerosis. The exact mechanism by which GLP-1RAs act on the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis is not fully understood.

Leukocyte recruitment and entry into the vessel wall is one of the most important contributors to atherogenesis and is mediated by the interaction between cell adhesion molecules expressed on inflamed vascular endothelium and their counter-ligands on the leukocyte surface. In this process, vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 plays a dominant role in the initiation of atherosclerosis by promoting slow rolling and eventual firm attachment and diapedesis of leukocytes by interacting with the heterodimeric integrin Very Late Antigen-4 (α4β1).4,5 Liraglutide has been shown to inhibit the progression of plaques in murine atherosclerosis6 and to reduce signal in radionuclide imaging targeting activated macrophages in patients with type 2 diabetes,7 indicating a role of liraglutide in reducing vascular inflammation. In vitro studies in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells treated with liraglutide have shown attenuation in tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α-induced expression of VCAM-1.8,9 Also, in an in vivo murine hypertension model, liraglutide leads to a reduction in vascular inflammation including reduction in aortic VCAM-1 mRNA expression.10 However, whether liraglutide also results in a down-regulation of vascular endothelial VCAM-1 expression in atherosclerosis models in vivo is not known. Commonly used techniques such as Western blot or immunohistochemistry do not exclusively measure the fraction of VCAM-1 expressed on the endothelial luminal surface that is responsible for leucocyte recruitment. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound molecular imaging (CEUMI) uses targeted microbubble (MB) contrast agents to noninvasively image the expression of endothelial surface markers such as VCAM-1.11, 12, 13, 14 Because the size of MBs ranges from 2 to 4 μm, they are pure intravascular tracers and detect the fraction of VCAM-1 present on the endothelial luminal surface.

The aim of our study was therefore to assess the effect of liraglutide on endothelial VCAM-1 expression in an in vivo murine model of atherosclerosis using CEUMI. We hypothesized that liraglutide treatment would result in a down-regulation of endothelial VCAM-1 expression independent of glucose levels.

Methods

Study design and animal model

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with Swiss federal legislation and national regulations in Denmark and were approved by the ethics committees of the veterinary office of the canton of Basel or animal experimentation inspectorate under the Danish Ministry of Justice. Female homozygous apolipoprotein E (ApoE) knockout (−/−) mice (N = 120; 002052; C57BL/6J-Apo-Etm1Unc) aged 6 to 9 weeks were put on a Western-type diet (D12079B; Research Diets, containing protein = 17 kcal%, carbohydrate = 43 kcal%, and fat = 41 kcal%) and randomly divided into 2 duration groups of daily liraglutide (1 mg/kg, Novo Nordisk) or vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline) subcutaneous administration for a period of 8 or 12 weeks. The doses were uptitrated to the full dose during the first 3 to 5 days of dosing. Five mice were euthanized earlier as per the exclusion criteria. The animals underwent high-frequency cardiac ultrasound and molecular imaging of the aortic arch 2 days before start of treatment at 0 weeks (baseline) and after 4, 8, or 12 weeks of treatment. Body weight and animal well-being were monitored regularly. The mice were euthanized at 8 or 12 weeks of treatment by removal of the blood volume by puncture of the left ventricle under deep sedation. The blood was collected into EDTA tubes and centrifuged immediately. The isolated plasma was stored at −80°C for biochemical and cytokine analysis. For excision of the thoracic aorta, a limited thoracotomy was performed under deep sedation. The aorta was perfused with 10% formalin. Connective tissue and fat were removed from the thoracic aorta, and the ascending portion and arch including the takeoff of the arch vessels were excised. Immersion fixation of the tissue in 4% paraformaldehyde was performed overnight. The harvested tissues were subsequently embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-μm sections for histology and immunohistology analysis.

Microbubble preparation

Lipid-shelled decafluorobutane MBs with functionalized biotin linker moieties were prepared by sonication of a gas-saturated aqueous suspension of distearoylphosphatidylcholine (2 mg/mL, Avanti Polar Lipids), polyoxyethylene-40-stearate (1 mg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich), and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-phosphoethanolamine-N-[biotinyl(polyethylene glycol)-3400] (0.14 mg/mL, Creative PEGWorks) in a glass vial. The MBs were washed by flotation-centrifugation to remove lipids not incorporated into the MB shell. MBs targeted to VCAM-1 (MBVCAM-1) were prepared by conjugation of biotinylated rat anti-mouse VCAM-1 antibody (Clone 429/MVCAM.A, Cat #. 553331, BD Pharmingen) to the MB surface using biotin-streptavidin-biotin linking. Control MBs (MBCtr,) bearing a nonspecific biotinylated rat IgG2a, K isotype control antibody (Clone R35-95, Cat #. 553928, BD Pharmingen) were also prepared.

Animal Instrumentation

Inhalational isoflurane (1% to 1.5% in room air for maintenance) was used to anesthetize the mice for echocardiography and CEUMI. The adequacy of anesthesia was regularly assessed with toe-pinch, and the dose of inhaled isoflurane adjusted if necessary. For MB injections, the internal jugular vein was cannulated (PE 50 tubing) while maintaining the body temperature at 37°C with a heating pad. The chest was depilated, and the animals were transferred onto a temperature-controlled imaging stage (Vevo Imaging Station). The heart rate was monitored.

Echocardiography

High-frequency ultrasound assessment of cardiac structure and function was performed at baseline and 4, 8, and 12 weeks after daily liraglutide or vehicle treatment, using a Vevo 2100 (VisualSonics Inc) imaging system with a MS 550D transducer operating at 40 MHz at the shortest possible pulse length. M-Mode images of the left ventricle in the parasternal short-axis plane at the midpapillary muscle level were used to measure left ventricular wall dimensions and the internal diameters at end-diastole (LVIDd) and at end-systole (LVIDs). Left ventricular mass derived from these measurements was normalized to the body weight. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated using the cube formula (LVEF [%] = 100 × [(LVIDd3 − LVIDs3)/LVIDd3]). Parasternal long-axis images of the aortic arch were used to measure internal diameter and the centerline peak systolic velocity in the aortic arch just distal to the brachiocephalic artery was measured by pulsed-wave spectral Doppler tracings.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound molecular imaging

CEUMI (Sequoia Acuson C512, Siemens Medical Systems) was done with a high-frequency linear-array probe (15L8) held in place by a railed gantry system. The ascending aorta of the mice was imaged in a long-axis plane from a right parasternal window by including the sinus of Valsalva and the take-off of the brachiocephalic artery.

A combination of power modulation and pulse inversion (Contrast Pulse Sequence) was used to image the contrast MBs at a transmission frequency of 7 MHz and a dynamic range of 50 dB. The gain settings were adjusted to levels just below noise speckle and maintained constant. MBVCAM-1 and MBCtr (1 × 106 MBs per injection) were injected intravenously in random order. Ultrasound imaging was paused from the beginning of MB injection for 8 minutes. Imaging was then resumed at a mechanical index of 0.87. The first acquired image frame was used to derive the total amount of MBs present within the aorta. The MBs in the ultrasound beam were then destroyed using several (>10) image frames at a mechanical index of 0.87. Several image frames (n = 3) at a long pulsing interval (10 seconds) were then captured to measure signal from freely circulating MBs. The video intensities were log-linear converted, and frames representing freely circulating MBs were averaged and subtracted digitally from the first image to derive signal from attached MBs alone. Contrast intensity was measured from a region of interest encompassing the sinus of Valsalva, the ascending aorta, and extending into the origin of the brachiocephalic artery. The selection of the region of interest was guided by fundamental frequency anatomical images of the ascending aorta and the aortic arch acquired at 14 MHz at the end of each individual imaging sequence. Signals were expressed as a signal ratio of MBVCAM-1 signal normalized to MBCtr control signal.15 Each animal was imaged at 2 time points during the duration of the experiments.

Measurement of lipids, glucose levels, and HbA1c

Plasma triglycerides (TG) were measured with an enzymatic colorimetric commercial assay kit (ETGA-200 and EGLY-200, BioAssay Systems). Total cholesterol, combined low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and very low density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL-C), as well as high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), were measured using an enzymatic colorimetric commercial assay kit (EHDL-100, BioAssay Systems). In the animals undergoing CEUMI, plasma HbA1c was measured using a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent commercial assay kit (E4657-100, BioVision), and nonfasting plasma glucose was measured using mouse glucose assay kit (#81692, Crystal Chem) in blood drawn after the imaging studies. In a separate group of animals (n = 20 on liraglutide treatment and n = 20 on vehicle treatment), whole-blood HbA1c was measured at baseline, day 44, and day 80 in a 5-μL full blood sample taken from the tip of the tail by puncturing the capillary bed with a lancet, using a heparinized capillary tube to sample the blood. The capillary tube was then shaken into 500 μL of Hitachi Hemolyzing Reagent and measured in a Hitachi 912 autoanalyzer (Roche A/S Diagnostics), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Assays were performed in duplicates according to manufacturer’s protocol with the exception of whole-blood HbA1c assays, which were done as single measurements.

Plasma cytokine analysis

ProcartaPlex multiplex custom immunoassay (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was performed on plasma samples to measure the following cytokines: interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17A, IL-33, interferon (IFN)-γ, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (CXCL1), monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, TNF-α, and Rantes. Plasma osteopontin (OPN) was determined using Mouse OPN ELISA kit (EMSPP1, Thermo Fisher Scientific). All assays were performed in duplicates according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Histology and immunohistology

See the expanded methods in the Supplemental Appendix for information.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed on GraphPad Prism software (version 9.3.1 for MacOS, GraphPad Software). Data are expressed either as the median and 25th to 75th percentile or as the mean ± SD if normally distributed (Komolgorov-Smirnov test and Shapiro-Wilk test, data are expressed as mean ± SD if both tests indicate normal distribution), unless otherwise indicated. Single comparisons between the 2 treatment groups were performed as appropriate with either a Mann-Whitney rank sum test or an unpaired t-test. A 2-way repeated measures analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons was performed to analyze the effect of treatment and duration on body weight of mice and blood HbA1c levels. For multiple pairwise comparisons of MB signals from CEUMI a Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance with Dunn`s multiple comparison post hoc test was used. A 2-sided P value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Effect of liraglutide treatment on body weight and metabolic parameters

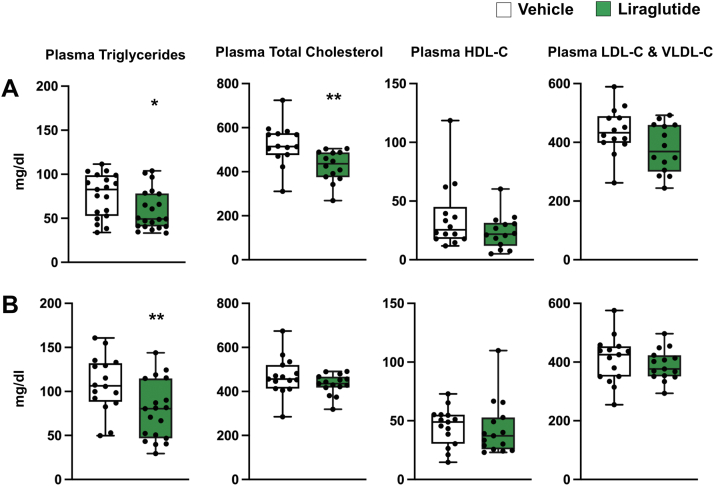

Compared with mice on vehicle treatment, liraglutide resulted in a significant 7% to 10% weight reduction throughout the study (Figure 1). Results from plasma lipid analysis are presented in Figure 2. Plasma TG levels were significantly reduced after 8 and 12 weeks of daily liraglutide treatment. Total cholesterol levels were significantly reduced after 8 weeks, but not after 12 weeks, of daily liraglutide treatment. Plasma HDL-C, LDL-C, and VLDL-C were not affected by daily liraglutide treatment for 8 or 12 weeks. Plasma and whole-blood HbA1c, as well as plasma glucose levels (Figure 3), did not differ between treatment groups.

Figure 1.

Effect of Liraglutide Treatment on Body Weight

Percentage change from baseline in body weight of apolipoprotein E−/− mice after high-fat diet and daily subcutaneous liraglutide or vehicle treatment up to 84 days. Data are mean ± SEM.

Figure 2.

Effect of Liraglutide Treatment on Plasma Lipids

Plasma triglyceride and cholesterol levels of apolipoprotein E−/− mice after high-fat diet and daily subcutaneous liraglutide or vehicle treatment for (A) 8 weeks (triglycerides, n = 19-21; cholesterol, n = 14) and (B) 12 weeks (triglycerides, n = 16-19; cholesterol, n = 15) (∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01). Data are median (horizontal line), 25% to 75% percentiles (box), and range of values (whiskers). HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; VLDL-C = very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Figure 3.

Effect of Liraglutide Treatment on Plasma HbA1c and Glucose

Plasma glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and glucose levels of apolipoprotein E−/− mice after high-fat diet and daily subcutaneous liraglutide or vehicle treatment for (A) 8 weeks (n = 16-20) and (B) 12 weeks (n = 17-20). Data are mean ± SD. Blood HbA1c percentage (%) levels shown in (C), and data are median (horizontal line), 25% to 75% percentiles (box), and range of values (whiskers).

In vivo CEUMI of VCAM-1 expression in the mouse aorta

MB preparations used for in vivo CEUMI had mean sizes of 3.52 ± 1.61 μm for MBVcam1 and 3.44 ± 1.53 μm for MBCtr (P = 0.20). Results from CEUMI are presented in Figure 4. The MBVCAM-1 to MBCtr signal ratio at baseline was around 1 and did not differ between the treatment groups. In vehicle-treated animals, there was a significant 3-fold increased MBVCAM-1 to MBCtr signal ratio at 4, 8, and 12 weeks. By contrast, this ratio remained unchanged at around 1 in liraglutide-treated animals throughout the study.

Figure 4.

Molecular Imaging of the Aortic Arch

(A) Fold change of background-subtracted contrast-enhanced ultrasound molecular imaging signal intensity from the aortic arch after injection of MBVcam-1 (microbubbles targeted to vascular cell adhesion molecule [VCAM]-1) and MBCtr (control) microbubbles (MB) in apolipoprotein E−/− mice at baseline (no treatment) and after high-fat diet and daily subcutaneous liraglutide or vehicle treatment for 4 weeks (n = 18-20), 8 weeks (n = 17-20), and 12 weeks (n = 15-17) (∗P < 0.05; ∗∗∗P < 0.001). Data are median (horizontal line), 25% to 75% percentiles (box), and range of values (whiskers). (B) Examples of color-coded CEUMI overlaid on anatomic images of the aortic arch illustrating low signal after injection of MBCtr in vehicle and liraglutide treated animals (top row), high signal after injection of MBVcam-1 in a vehicle treated animal (bottom row left) and low signal after injection of MBVcam-1 in a liraglutied treated animal (bottom row right).

Heart rate and high-frequency echocardiographic assessment of cardiac function

Heart rate was not different between the treatment groups at baseline and after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment (Table 1). High-frequency echocardiography showed the aorta systolic flow velocity and left ventricular ejection fraction to be similar for vehicle- and liraglutide-treated mice at all time points. Aorta internal diameter was higher for vehicle as compared with liraglutide-treated mice only after 8 weeks of treatment. The left ventricular mass corrected for body weight was higher for vehicle-treated as compared with liraglutide-treated mice only after 8 weeks of treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Physiological and Echocardiographic Data

| 0 Weeks |

4 Weeks |

8 Weeks |

12 Weeks |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | Liraglutide | Vehicle | Liraglutide | Vehicle | Liraglutide | Vehicle | Liraglutide | |

| Sample size, n | 19-21 | 21-22 | 16-18 | 20-21 | 18-20 | 16-17 | 15 | 19 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 491± 69 | 482 ± 65 | 497 ± 46 | 493 ± 61 | 519 ± 37 | 493 ± 45 | 496 ± 64 | 500 ± 53 |

| Aortic PSV, m/s | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 |

| Aortic ID. mm | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1b | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

| LVEF, % | 75 ± 7 | 75 ± 9 | 75 ± 9 | 77 ± 6 | 77 ± 9 | 77 ± 8 | 73 ± 11 | 74 ± 11 |

| LV mass/body weight, mg/g | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 0.6a | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 2.8 ± 0.7 |

Values are mean ± SD, except as noted.

ID = internal diameter; LV = left ventricular; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; PSV = peak systolic velocity.

P < 0.05

P < 0.01 vs vehicle treatment.

Effect of liraglutide treatment on histologic plaque area and aortic luminal interface VCAM-1 expression on immunohistology

Masson`s trichrome stains showed a reduction after 8 and 12 weeks in the plaque lesion area both at the aortic root (Figure 5) and ascending aorta (Figure 6) level in mice treated with daily liraglutide vs vehicle injections. The reduction in the plaque lesion area was more pronounced in the ascending aorta vs the aortic root. Plaques were composed primarily of macrophages that expressed Vcam-1 (Supplemental Figure 1). Expression of luminal VCAM-1 on immunofluorescent staining (Figure 7) was reduced by about one-third at the aortic root and ascending aorta level in mice treated with daily liraglutide injections for 8 and 12 weeks.

Figure 5.

Effect of Liraglutide Treatment on Aortic Root Atherosclerotic Plaque Burden

Percent of total luminal plaque area at the aortic root of apolipoprotein E−/− mice after high-fat diet and daily subcutaneous liraglutide or vehicle treatment for (A) 9 weeks (n = 6) and (B) 12 weeks (n = 6) (∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.005). Data are mean ± SD. Representative image of Masson's trichrome stain of aortic root after (C and D) 8 weeks and (E and F) 12 weeks of high-fat diet and liraglutide or vehicle treatment.

Figure 6.

Effect of Liraglutide Treatment on Ascending Aortic Atherosclerotic Plaque Burden

Percent of total luminal plaque area in the ascending aorta of apolipoprotein E−/− mice after high-fat diet and daily subcutaneous liraglutide or vehicle treatment for (A) 8 weeks (n = 6) and (B) 12 weeks (n = 6) (∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.005). Data are mean ± SD. Representative image of Masson's trichrome stain of aortic root after (C and D) 8 weeks and (E and F) 12 weeks of high-fat diet and liraglutide or vehicle treatment.

Figure 7.

Effect of Liraglutide Treatment on Aortic Luminal Interface Expression of VCAM-1

Percentage of endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) immunofluorescent staining of the aortic root and ascending aorta of apolipoprotein E−/− mice after high-fat diet and daily subcutaneous liraglutide or vehicle treatment for (A) 8 weeks (n = 8-9) and (B) 12 weeks (n = 14-16) (∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.005; ∗∗∗P < 0.001). Data are mean ± SD. Representative image of endothelial VCAM-1 immunofluorescent staining shown for vehicle (C) and liraglutide (D) treatment.

Effect of liraglutide treatment on plasma cytokines

Daily liraglutide vs vehicle treatment led to a trend for reduced values at 8 weeks and significant reductions in the plasma concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, MCP-1, and OPN (Figure 8) after 12 weeks of treatment. Plasma IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17A, IL-33, IFN-γ, GM-CSF, CXCL1, and Rantes levels did not show any differences after 8 or 12 weeks of daily liraglutide treatment (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 8.

Effect of Liraglutide Treatment on Plasma Cytokine Levels

Plasma cytokine levels of apolipoprotein E−/− mice after high-fat diet and daily subcutaneous liraglutide or vehicle treatment for (A) 8 weeks (TNF-α, IL-1β, and MCP-1, n = 18-19; OPN, n = 10) and (B) 12 weeks (TNF-α, IL-1β, and MCP-1, n = 13-14; OPN, n = 10) (∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01). Data are median (horizontal line), 25% to 75% percentiles (box), and range of values (whiskers). TNF = tumor necrosis factor; IL = interleukin; MCP = monocyte chemoattractant protein.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that treatment with liraglutide led to a reduction in endothelial expression of VCAM-1 in a mouse model of atherosclerosis. This effect did not depend on changes in plasma glucose levels. Taken together with the reduction in atherosclerosis progression and levels of proinflammatory cytokine that we observed, this suggests that liraglutide treatment reduced vascular inflammation in atherosclerosis, in part by attenuation of recruitment of leukocytes to the vascular wall, which may explain the observed effect of GLP-1RAs on cardiovascular events in large clinical trials.

GLP-1 is produced in enteroendocrine cells in the gut and is secreted into the bloodstream upon food intake. GLP-1 stimulates insulin secretion, inhibits gastric emptying, and promotes satiety.16 GLP-1 acts via the G protein-coupled receptor (GLP-1R), which is expressed in the gastrointestinal tract and other tissues. Although the cardiovascular receptor expression is confined to smooth muscle cells in the walls of arteries and arterioles of renal and lung vasculature and myocytes of the sinoatrial node in the heart,17 there are reports of receptor-independent cardiovascular effects.18,19 The GLP-1RAs liraglutide and semaglutide have been shown to reduce cardiovascular events in large clinical trials. In terms of mechanistic insight, preclinical data show that treatment with liraglutide reduces TNF-α–induced endothelial intercellular cell adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 (ICAM-1) and VCAM-1 expression in vitro.8,9 In in vivo murine models of atherosclerosis, liraglutide, and semaglutide reduce atherosclerotic plaque formation,20 reduce ICAM-1, and improve plaque stability scores.6,9 Our study adds new information on in vivo aortic endothelial expression of VCAM-1, which was reduced throughout the study duration in liraglutide-treated animals. Importantly, the reduction in VCAM-1 was evidenced both using in vivo ultrasound molecular imaging—a direct readout of endothelial expression—as well as with quantitative immunohistochemistry. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 are expressed on the endothelium of large arteries in areas that are predisposed to develop atherosclerosis and in the shoulder regions of developing plaques; in addition, ICAM-1 is also more widely expressed. In murine atherosclerosis models, endothelial VCAM-1 levels, but not ICAM-1 levels, have been shown to be crucial for plaque development.4 Our data are in line with data from a small clinical trial showing a reduction in soluble VCAM-1 under liraglutide treatment in patients with recent-onset diabetes21

In a post hoc analysis of the LEADER trial, a mild reduction of HbA1c values in liraglutide-treated vs placebo-treated patients was identified as a potential mediator of cardiovascular effects.22 In our study, we did not find significant differences in plasma glucose levels between vehicle- and liraglutide-treated animals. Because plasma glucose and plasma HbA1c values (Figures 3A and 3B) were measured in blood taken at the end of prolonged imaging studies, we also measured full-blood HbA1c in a separate experiment in a large group of vehicle- or liraglutide-treated animals (Figure 3C). The full-blood HbA1c values below 4% are consistent with a nondiabetic glycemic state,23 and the lack of differences between groups excludes differences in glucose levels as a mediator of the effects of liraglutide on vascular inflammation that we observe in our study.

Consistent with the effect of liraglutide on satiety, there was an initial weight loss compared with animals receiving vehicle, and there was a difference in weight throughout the study. The transient decrease in total cholesterol level that we saw at 8 weeks, but not at 12 weeks, may relate to a type 1 statistical error, because previous studies with liraglutide in ApoE−/− mice20 and humans24 have not found a significant effect on total cholesterol levels. Also, there was no difference in LDL/VLDL or HDL-C values both at 8 and 12 weeks that could lead to differences in atherogenesis. By contrast, there were significant differences in serum TG values, with 20% to 30% lower values in animals treated with liraglutide. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TGRL) have been shown to modulate endothelial inflammation; however, both proinflammatory as well as anti-inflammatory effects have been reported depending on TGRL composition25 with increased particle TG density resulting in a proinflammatory effect. We did not specifically measure and characterize TGRL and therefore cannot exclude that the lower TG values observed in our study contributed to the attenuation of vascular inflammation in the liraglutide-treated group.

The transcription of VCAM-1 is driven mainly by the transcription factor NFκB. Signaling of TNF-α and interleukins via their receptors leads to activation and nuclear translocation of NFκB where it induces transcription of proinflammatory factors including VCAM-1.26,27 A down-regulation of NFκB signaling in ApoE−/− mice treated with GLP-1 analogs in aortic tissue has been shown.20 In line with this, we see a trend for reduction of TNF-α, as well as IL-1β, after 8 weeks and a significant reduction after 12 weeks of liraglutide treatment, further supporting the notion that liraglutide attenuates vascular inflammation. In this respect, it is important to notice that similar to the current effect on VCAM-1 expression, treatment with canakinumab, a monoclonal antibody targeted to IL-1β also leads to down-regulation of VCAM-1 in vivo.28 In addition to reductions in IL-1β and TNF-α, we also observed a reduction in the chemotactic cytokine MCP-1, also termed CCL-2. Reductions in CCL-2 or its receptor CCR-2 have been shown to reduce subendothelial lipid deposition and recruitment of monocytes into the arterial wall.29,30 Similarly, chronic elevations in levels of OPN, a glycophosphoprotein that partly acts as a cytokine, have been shown to promote fatty streak formation in murine atherosclerosis models on high-fat diet via recruitment of monocytes.31 Thus, the decreased levels in MCP-1 and OPN that we observe suggest that there is an effect of liraglutide on vascular inflammation that potentiates the effect of the reduction in endothelial VCAM-1 by reducing chemoattraction for monocytes.

Study limitations

Several limitations of our study deserve mentioning. First, the dose of liraglutide used in our study was higher than the dose used in clinical trials (1 mg/kg once daily in our study vs a fixed dose of 1.8 mg once daily in the LEADER trial). This dose was based on a shorter half-life of 3 to 4 hours of liraglutide in mice (B. Rolin, unpublished data, February 2022) compared with 13 hours in humans.32 However, lower doses of liraglutide have been shown to have a similar effect on reduction in plaque burden as observed in our study in murine atherosclerosis models.33 Whether even higher doses of liraglutide would have an incremental effect on vascular inflammation independent of metabolic effects was not tested in our study. Second, our study was not designed to dissect the exact mechanism by which liraglutide leads to a down-regulation of VCAM-1. Previous studies using liraglutide have shown that the effects of liraglutide on plaque development and plaque stability are inhibited by cotreatment with the GLP-1R antagonist exendin-9, suggesting that the effects of liraglutide on atherosclerosis are mediated via GLP-1R.6

Conclusions

In summary, using CEUMI, we have shown a down-regulation in the VCAM-1 signal in vivo on the vascular endothelium in a mouse model of atherosclerosis in response to liraglutide treatment. Importantly we showed that this reduction in expression was independent of plasma glucose levels. By reducing VCAM-1, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, liraglutide attenuated plaque formation.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: Liraglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, is used for treatment of diabetes and obesity. In the large clinical LEADER trial, liraglutide reduced death from cardiovascular causes in patients with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk. The exact mechanisms by which liraglutide acts on atherosclerosis are unknown. In a murine model of atherosclerosis and using in vivo ultrasound molecular imaging, we show that liraglutide leads to a down-regulation of the endothelial expression of VCAM-1, which is critically involved in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis. This effect is independent of plasma glucose levels.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Further studies are needed to assess which exact signaling pathway confers the effect of liraglutide on endothelial VCAM-1 expression, as well as other potential mechanisms, because this may also help to identify mechanisms underlying the protective effects of GLP-1RAs on the cardiovascular system. Future clinical studies could examine the effect of liraglutide on cardiovascular events in nondiabetic patient populations.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

This work is supported by grants 310030-169905 and 310030-197673 from the Swiss national Science Foundation and from the Swiss Heart Foundation to Dr Kaufmann. This work was funded in part by Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsværd, Denmark. The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Loic Sauteur from the DBM Microscopy Core Facility and Diego Calbrese from the DBM Histology Core Facility for their support. The authors are thankful to Jannis Baumgartner and Joris Bachmann for their help with the experiment preparations.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For an expanded Methods section and a supplemental figure and table, please see the online version of this paper.

Appendix

References

- 1.Puri R., Kataoka Y., Uno K., Nicholls S.J. The distinctive nature of atherosclerotic vascular disease in diabetes: pathophysiological and morphological insights. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12:280–285. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0270-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marso S.P., Daniels G.H., Brown-Frandsen K., et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311–322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marso S.P., Bain S.C., Consoli A., et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1834–1844. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cybulsky M.I., Iiyama K., Li H., et al. A major role for VCAM-1, but not ICAM-1, in early atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1255–1262. doi: 10.1172/JCI11871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huo Y., Hafezi-Moghadam A., Ley K. Role of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and fibronectin connecting segment-1 in monocyte rolling and adhesion on early atherosclerotic lesions. Circ Res. 2000;87:153–159. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaspari T., Welungoda I., Widdop R.E., Simpson R.W., Dear A.E. The GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide inhibits progression of vascular disease via effects on atherogenesis, plaque stability and endothelial function in an ApoE(-/-) mouse model. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2013;10:353–360. doi: 10.1177/1479164113481817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen J.K., Zobel E.H., von Scholten B.J., et al. Effect of 26 weeks of liraglutide treatment on coronary artery inflammation in type 2 diabetes quantified by [(64)Cu]Cu-DOTATATE PET/CT: results from the LIRAFLAME trial. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.790405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu H., Dear A.E., Knudsen L.B., Simpson R.W. A long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue attenuates induction of plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 and vascular adhesion molecules. J Endocrinol. 2009;201:59–66. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaspari T., Liu H., Welungoda I., et al. A GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide inhibits endothelial cell dysfunction and vascular adhesion molecule expression in an ApoE-/- mouse model. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2011;8:117–124. doi: 10.1177/1479164111404257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helmstadter J., Frenis K., Filippou K., et al. Endothelial GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) receptor mediates cardiovascular protection by liraglutide in mice with experimental arterial hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:145–158. doi: 10.1161/atv.0000615456.97862.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufmann B.A., Sanders J.M., Davis C., et al. Molecular imaging of inflammation in atherosclerosis with targeted ultrasound detection of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Circulation. 2007;116:276–284. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.684738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaufmann B.A., Carr C.L., Belcik J.T., et al. Molecular imaging of the initial inflammatory response in atherosclerosis: implications for early detection of disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:54–59. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.196386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khanicheh E., Mitterhuber M., Xu L., Haeuselmann S.P., Kuster G.M., Kaufmann B.A. Noninvasive ultrasound molecular imaging of the effect of statins on endothelial inflammatory phenotype in early atherosclerosis. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khanicheh E., Qi Y., Xie A., et al. Molecular imaging reveals rapid reduction of endothelial activation in early atherosclerosis with apocynin independent of antioxidative properties. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:2187–2192. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuruta J.K., Klauber-DeMore N., Streeter J., et al. Ultrasound molecular imaging of secreted frizzled related protein-2 expression in murine angiosarcoma. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drucker D.J. The cardiovascular biology of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metab. 2016;24:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pyke C., Heller R.S., Kirk R.K., et al. GLP-1 receptor localization in monkey and human tissue: novel distribution revealed with extensively validated monoclonal antibody. Endocrinology. 2014;155:1280–1290. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ban K., Noyan-Ashraf M.H., Hoefer J., Bolz S.S., Drucker D.J., Husain M. Cardioprotective and vasodilatory actions of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor are mediated through both glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor-dependent and -independent pathways. Circulation. 2008;117:2340–2350. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siraj M.A., Mundil D., Beca S., et al. Cardioprotective GLP-1 metabolite prevents ischemic cardiac injury by inhibiting mitochondrial trifunctional protein-alpha. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:1392–1404. doi: 10.1172/JCI99934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rakipovski G., Rolin B., Nohr J., et al. The GLP-1 analogs liraglutide and semaglutide reduce atherosclerosis in ApoE(-/-) and LDLr(-/-) mice by a mechanism that includes inflammatory pathways. J Am Coll Cardiol Basic Trans Science. 2018;3:844–857. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X.M., Zhang W.Q., Tian Y., Wang L.F., Chen C.C., Qiu C.M. Liraglutide suppresses non-esterified free fatty acids and soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 compared with metformin in patients with recent-onset type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:53. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0701-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buse J.B., Bain S.C., Mann J.F.E., et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction with liraglutide: an exploratory mediation analysis of the LEADER trial. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:1546–1552. doi: 10.2337/dc19-2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan K.A., Hayes J.M., Wiggin T.D., et al. Mouse models of diabetic neuropathy. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;28:276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tye S.C., de Vries S.T., Mann J.F.E., et al. Prediction of the effects of liraglutide on kidney and cardiovascular outcomes based on short-term changes in multiple risk markers. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.786767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun C., Alkhoury K., Wang Y.I., et al. IRF-1 and miRNA126 modulate VCAM-1 expression in response to a high-fat meal. Circ Res. 2012;111:1054–1064. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.270314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pamukcu B., Lip G.Y., Shantsila E. The nuclear factor--kappa B pathway in atherosclerosis: a potential therapeutic target for atherothrombotic vascular disease. Thromb Res. 2011;128:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramji D.P., Davies T.S. Cytokines in atherosclerosis: Key players in all stages of disease and promising therapeutic targets. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2015;26:673–685. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shentu W., Ozawa K., Nguyen T.A., et al. Echocardiographic molecular imaging of the effect of anticytokine therapy for atherosclerosis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2021;34:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2020.11.012. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boring L., Gosling J., Cleary M., Charo I.F. Decreased lesion formation in CCR2-/- mice reveals a role for chemokines in the initiation of atherosclerosis. Nature. 1998;394:894–897. doi: 10.1038/29788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dawson T.C., Kuziel W.A., Osahar T.A., Maeda N. Absence of CC chemokine receptor-2 reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 1999;143:205–211. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Isoda K., Kamezawa Y., Ayaori M., Kusuhara M., Tada N., Ohsuzu F. Osteopontin transgenic mice fed a high-cholesterol diet develop early fatty-streak lesions. Circulation. 2003;107:679–681. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055739.13639.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson S.H., Martin T.S., Jones J.D., Seal D., Emanuel F. Liraglutide (victoza): the first once-daily incretin mimetic injection for type-2 diabetes. P T. 2010;35(9):498–529. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koshibu M., Mori Y., Saito T., et al. Antiatherogenic effects of liraglutide in hyperglycemic apolipoprotein E-null mice via AMP-activated protein kinase-independent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2019;316:E895–E907. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00511.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.