Abstract

Dichroa febrifuga Lour. is a traditional medicinal herb that has been applied in the treatment of malaria and some other infectious diseases. Studies recently have focused on the anti-inflammation of the extracts of Dichroa febrifuga Lour. although there have not many reports about which compounds play the essential role. Therefore, in this study, we isolated hydrangenoside C (1), isoarborinol (2), and methyl 1,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-fructofuranoside (3) from the leaves of Dichroa febrifuga. Subsequently, the anti-inflammatory property of 1–3 was assessed using an in vivo assay of edema mouse model which was induced by carrageenan. Out of the three, 2 inhibited the edema effectively and dose-dependently, similarly to diclofenac while there was no obvious activity observed in 1 and 3. The in silico results demonstrated that 2 enables binding to 5-LOX and PLA2 via generating h-bonds. This is the first study to mention the anti-inflammation of 2 in Dichroa febrifuga Lour., and would be a contribution to further studies to elucidate the promising bioactivities of this compound.

Keywords: Anti-inflammation; Dichroa febrifuga Lour.; Hydrangenoside; Isoarborinol; Methyl 1,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-fructofuranoside

1. Introduction

Inflammation is an activity to protect the body against the invasion of harmful stimuli. In the process, inflammation might damage the tissues or organs which accidentally causes various diseases in its host (Chen et al., 2018). Up to date, nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs are mainly used to treat problems that are linked to arthritis and other musculoskeletal disorders, reduce inflammation and pain which contains many adverse effects, some of which may be life – threatening (Ho et al., 2018, Bindu et al., 2020). Therefore, finding an alternative compound, mainly from natural resources, has been a race among scientists for many years, attracting much attention both inside and outside the field.

Dichroafebrifuga Lour., an evergreen shrub belonging to the Saxifragaceae family is an important herb for the treatment of malaria. The extracts of the roots and leaves are demonstrated effective against different Plasmodium species and other diseases (Jang et al., 1948, Mitsui et al., 2020). Studies demonstrated that the activity of this plant is predominantly attributed to febrifugine, an active quinazoline-type alkaloid (Jiang et al., 2005, Murata et al., 1999). Additionally, many studies have investigated the bioactivities of an analog of febrifugine, halofuginone, which has been approved for drugs for malaria, coccidiosis in broiler chickens and growing turkeys, protozoan parasites in cattle, etc. (Pines and Spector, 2015). Current approaches have focused on the other activities of the extracts of Dichroa febrifuga Lour. and isolated compounds including anti-cancer (Jin et al., 2014, Wang et al., 2020, Chen et al., 2016) and anti-inflammation (Park et al., 2009, Choi et al., 2003). The aqueous extract of Dichroa febrifuga root inhibited the inflammation induced by endotoxin. This activity was expressed via suppressing the production of NO, the underlying mechanisms were supposed to be due to inhibiting the signaling pathways of proinflammatory and inflammatory cytokines in LPS-stimulated mouse peritoneal macrophages (Kim et al., 2000).

Hydrangenoside C (C29H38O12) is a glycoside isolated from species of Hydrangeaceae. Together with other compounds in the extract, hydragenoside C might exhibit anti-photoaging activity in UVB-exposed human fibroblasts (Myung et al., 2020). Isoarborinol is a triterpene with the molecular formula of C30H50O. Isoarborinol methyl ether demonstrated antimicrobial and antifungal activities ((Ragasa et al., 2009). The antiamoebic activity of Petiveria alliacea L. was supposed to be due to the major designated component isoarborinol (Zavala-Ocampo et al., 2017). In an analysis of Sanjie Zhentong Capsule which has been used to treat adenomyosis, the results showed that one of the key components is isoarborinol (Du et al., 2020). Methyl 1,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-fructofuranoside (C15H22O10) is a derivative of fructofuranoside which displayed valuable bioactivities including antitumor (n-butyl-β-D-fructofuranoside) (Lu et al., 2014) and antioxidant activity (β-D-fructofuranosides) (Herrera-González et al., 2017).

In this study, we isolated compounds including hydrangenoside C (1), isoarborinol (2), and methyl 1,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-fructofuranoside (3) from the leaves of Dichroa febrifuga Lour., then, examined the inflammation inhibiting activity of them using an assay of the carrageenan-stimulated edema mouse model.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. The isolation of compounds

Dichroa febrifuga Lour.was collected and identified by the University of Agriculture and Forestry, Hue University.

The leaves of Dichroa febrifuga were extracted at room temperature using MeOH with the ratio of 1.5 kg:5.0 L solvent, 2 times repeated. 65.7 g of crude extract dissolved in water was partitioned using 5.0 L CH2Cl2, 3 times, then applied onto vacuo to remove the solvent. Particularly, 2 partions were obtained, including CH2Cl2 (C, 13.5 g) and water (W, 52.2 g). The C extract was subjected to silica gel column eluting with n-hexane-CH2Cl2 gradient system (100:0 → 0:100, v/v) to obtain 6 smaller fractions, Fr.1-Fr.6. Fraction Fr.4 (3.3 g) was separated into 10 sub-fractions, Fr.4.1-Fr.4.10, on a silica gel column eluting with n-hexane–acetone (30:1, v/v, 6.5 L). Subfraction Fr.4.4 (185.0 mg) was purified by a silica gel column, using n-hexane-CH2Cl2 (20:1, v/v, 1.0 L) as mobile phase to afford 1 (Off-white powder, 18.3 mg) and 2 (Colorless noodles, 22.5 mg). Subfraction Fr.4.9 (450.0 mg) was loaded onto an open silica gel column eluting with n-hexane-CH2Cl2 (10:1, v/v, 2.5 L) to obtain 5 smaller fractions, Fr.4.10.1-Fr.4.10.5. Finally, subfraction Fr.4.10.4 (125.0 mg) was further purified using n-hexane–acetone (15:1, v/v, 1.0 L) to yield 3 (white crystal, 21.8 mg). The nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy has been applied to identify the compounds.

2.2. Experimental mice

The experiments used Swiss albino mice (aged 5–6 weeks) which were supplemented by Pasteur Institute, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam with a weight of approximately 18 ± 2 g. The mice were maintained in standard conditions for 1 week before use including room temperature, approximately 70% humidity, 12 h dark/light cycle. The animal experiments were followed by ethical principles in Declaration of Helsinki (1964).

2.3. The in vivo assay

A carrageenan-induced mouse paw edema model was performed following the protocol of Winter CA (Winter et al., 1962) to examine the anti-inflammatory capability of 1–3. The mice were administrated intraperitoneally of 1–3 for 1 h before subplantar injection with 40 µL of 1% carrageenan to induce acute inflammation. Diclofenac (10 mg/kg) was used as positive control while saline (0.9% w/v NaCl) was used as negative control. Six mice were in each group and total 5 groups of mice were used. Groups I-V were treated with saline, diclofenac, 1–3 (50 mg/kg), respectively. The paw volume was measured using a plethysmometer (Panlab Harvard Apparatus, Barcelona, Spain) at C0 (before carrageenan treatment) and Ct (after carrageenan treatment) at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 h.

The increasing rate of paw swelling was calculated using the following equation:

% increasing rate of paw swelling = 100 × (Ct − C0)/C0.

To confirm the swelling reduction of positive and active compounds, the treated paws were pictured after 5 h of carrageenan treatment.

The most effective compound was used for testing at different concentrations. The experiment was performed following the above-mentioned protocol. The mice were intraperitoneally treated with the compound at different concentrations (12.5, 25 and 50 mg/kg), then injected with carrageenan to induce the inflammation. A plethysmometer was used to measure the inflamed paw volume at C0 (before carrageenan treatment) and Ct (after carrageenan treatment) at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 h.

2.4. Ligand docking

The binding of 2 and diclofenac to inflammatory proteins was analyzed using Maestro software (Schrödinger Release 2020-3). Cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and 5-lipooxygenase (5-LOX) which are the main proteins relating to the inflammation were used in this model. The crystal structures of compounds were obtained from database of Protein Data Bank including COX-1 (PDB 3KK6), COX-2 (PDB 1CX2), 5-LOX (PDB 3V99) and PLA2 (PDB 1P7O). The formation of bond orders, removal of waters, generation het states using Epik, optimization of the h-bond, and minimization of the OPLS3e force field were performed using Protein Preparation Wizard. The grid box was arranged at the centroid of native ligands with the size of 20 Å.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The collected data were described with the standard error of the means. A Graphpad Prism software program was used to analyze the data (Graphpad prism, version 8.0, San Diego, CA). The significant difference between the sample means compared to the negative control was analyzed using t-test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 and ***, p < 0.0001 with p < 0.05 were considered statistical difference.

3. Results

3.1. The isolation and identification of compounds

The MeOH extract of Dichlora febrifuga was partitioned with CH2Cl2 and applied onto chromatographies. As a result, three compounds including hydrangenoside C (1), isoarborinol (2), and methyl 1,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-fructofuranoside (3) were isolated (Supplement S1). The structure of compounds was described in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Structures of 1–3 isolated from Dichroa febrifuga Lour.

3.2. Anti-inflammatory assay

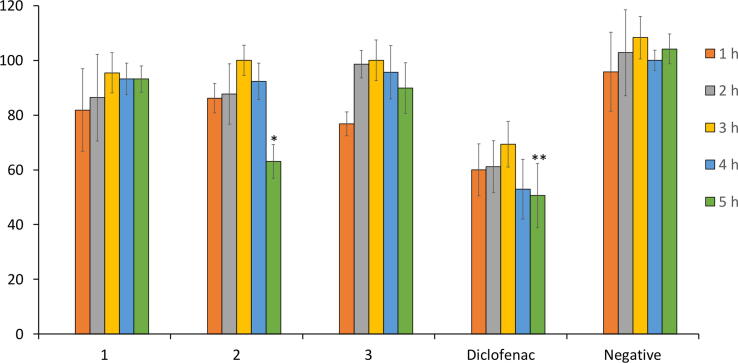

An edema mouse model which was induced by injection of carrageenan was used to assess the anti-inflammatory activity of 1–3. Particularly, the mice (six mice in each group) were peritoneally injected with 1–3 for 1 h before injection of carrageenan. The volume of oedema was identified to compare to that of negative and positive controls. The increasing paw volume is described in Fig. 2. Diclofenac significantly reduce paw edema during the tested period, especially at 5 h (p < 0.01). Of the three, 2 effectively inhibited the paw swelling in the late phase (5 h) of carrageenan treatment (p < 0.05). There was no inhibition observed in 1 and 3 (p > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

The edema inhibition of 1–3. After peritoneal injection of compounds and then subplantar injection of carrageenan, the volume of the edema paw was identified hourly from 1 to 5 h. Saline was used as negative control and diclofenac was used as positive control. Six mice were used in each group.

The reduction in paw size in Groups treated with diclofenac or 2 at a concentration of 50 mg/kg was observed in Fig. 3. There was a dramatic increase in the size of paw treated with saline (Negative) while in those treated with diclofenac and 2, there was a slight collapse.

Fig. 3.

The paw images after treatment of 2. The mice were peritoneally injected with 2 (50 mg/kg), followed by injection of carrageenan to cause edema. After 5 h, the size of treated paws was pictured at both lateral and plantar views. Normal is mouse’s paw without carrageenan treatment. Saline was used as negative control.

To analyze further the activity of 2, different concentrations of 2 were used to administer into mice, followed by inflammatory induction using carrageenan. The paw volume was measured and shown in Fig. 4. As a result, 2 reduced the edema dose-dependently. Specifically, at a concentration of 50 mg/kg, 2 clearly lowered the swelling during 1–5 h, especially at 5 h (p < 0.01). Lower concentrations of 12.5 and 25 mg/kg also significantly inhibit the inflammation-induced swelling (p < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

The edema inhibition of 2 at different doses. The mice were peritoneally injected with 2 (12.5 mg/kg, 25 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg), followed by injection of carrageenan to cause edema. The paw edema was measured hourly from 1 to 5 h after carrageenan treatment. Saline was used as negative control. Six mice were used in each group.

3.3. Ligand docking

To confirm the in vivo assay, the binding of 2 with different inflammatory proteins including COX-1, COX-2, 5-LOX and PLA2 was analyzed using docking software. The binding free energy of 2 and diclofenac was shown in Table 1. In case of COX-1 and COX-2, 2 could not bind to these compounds while diclofenac showed high binding capacity with low free energy (-45.2 and −49.4 kcal.mol−1 respectively). However, 2 expressed high binding affinity to 5-LOX and PLA2, similar to diclofenac. Particularly, the MM-GBSA estimation of 2 and diclofenac to 5-LOX were −26.7 and −29.3 kcal.mol−1 respectively while these to PLA2 were −64.6 and −59.1 kcal.mol−1, respectively.

Table 1.

The estimation of 2 and diclofenac with different inflammatory compounds.

| Ligands |

MM-GBSA estimation (kcal.mol−1) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COX-1 | COX-2 | 5-LOX | PLA2 | |

| 2 | – | – | −26.7 | −64.6 |

| Diclofenac | −45.2 | −49.4 | −29.3 | −59.1 |

4. Discussion

Carrageenan is an acute inflammatory inducer that is proceeded widely to examine the inflammation-inhibiting property of new agents or extracts. Carrageenan causes acute inflammation via biphasic mechanism: (1) early phase, the release of mediators including histamine, serotonin, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) and bradykinin; (2) late phase, the elevation of prostaglandins and inducible cyclooxygenase (COX-2), neutrophil infiltration and activation to produce reactive oxygen species (Necas and Bartosikova, 2013, Salvemini et al., 1996, Posadas et al., 2004). This study found that 2 significantly and dose-dependently inhibited the oedema caused by carrageenan in both early phase and more effectively in the late phase (5 h) after inflammation.

Triterpenoids are constituents predominantly isolated from plants, demonstrating numerous promising properties consisting of antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, etc. (De Almeida et al., 2015). Previous research mentioned the inflammatory inhibition of triterpenoids via reducing the release of serotonin and phospholipase A2; arachidonic acid, 5-lipoxygenase. Additionally, some triterpenoids have been demonstrated to inhibit the release of interleukin, colagenase, radical species, lipid peroxidation and histamine (Ríos et al., 2000). Therefore, the studies about anti-inflammation of triterpenoids have attracted much attention. However, in a study of Jeong et al. (2014), there was no activity of isoarborinol on the inhibition of NO release in activated macrophage cells. In our study, isoarborinol inhibited carrageenan-induced inflammation at the injection dose of 50 mg/kg dose-dependently (Fig. 1 and Fig. 3). Therefore, the action mechanism of isoarborinol might be accompanied by another pathway in the in vivo model. This is the first study to demonstrate the anti-inflammation of isoarborinol using an edema model using carrageenan.

A docking software was applied to confirm the binding of 2 to different anti-inflammatory proteins. As a result, 2 could not bind to both COX-1 and COX 2 while diclofenac showed high binding capacity. The disabled binding of 2 can be explained by the large steric structure of 2. However, 2 expressed high binding affinity to 5-LOX and PLA2, similar to diclofenac. These estimates were consistent with in vivo results of 2 and diclofenac which showed similar efficiency in reducing the carrageenan-induced swelling. Fig. 5 exhibited that 2 was held by one h-bond donor with 5-LOX and one h-bond donor, one h-bond acceptor with PLA2. In addition, an important factor in 5-LOX inhibition of 2 and diclofenac is the ability to form coordination bonds with the ferrous ion, where the inflammatory redox reaction of arachidonic acid has been reported previously (Radmark, 2009, Nguyen et al., 2020). Based on the in silico results, we might explain the anti-inflammation mechanism of 2 via the inhibition of 5-LOX and PLA2 pathways by h-bonds generation. Futher experiments to confirm the binding of 2 with 5-LOX and PLA2 by analyzing the downstream mRNA or protein levels should be performed. Furthermore, OH residue of 2 seems to be responsible for the anti-inflammatory activity, thus, the study of 2 without OH residue should be tested.

Fig. 5.

Binding poses of 2 (left) and diclofenac (right) with 5-LOX (A) and PLA2 (B).

5. Conclusions

In this study, we isolated 1–3 from the leaves of Dichroa febrifuga to explore the anti-inflammatory property of this precious herb. Subsequently, property of inflammatory inhibition was assessed using an in vivo assay of edema mouse model. Among three compounds, 2 inhibited the edema effectively and dose-dependently, similarly to diclofenac while there was no obvious activity observed in 1 and 3 based on the obtained research results. The in silico results suggested that the activity of 2 might be related to inhibiting 5-LOX and PLA2 via generating h-bonds. This is the first study to state the anti-inflammation property of 2, contributing to further studies to elucidate the promising bioactivities of this compound.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary material to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2023.103606.

Contributor Information

Ty Viet Pham, Email: phamvietty@hueuni.edu.vn.

Hang Phuong Thi Ngo, Email: hangntp.qh@hue.edu.vn.

Nguyen Hoai Nguyen, Email: nguyen.nhoai@ou.edu.vn.

Anh Thu Do, Email: thuda@huflit.edu.vn.

Thien Y. Vu, Email: vuthieny@tdtu.edu.vn.

Minh Hien Nguyen, Email: nguyenminhhien@tdtu.edu.vn.

Bich Hang Do, Email: dobichhang@tdtu.edu.vn.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary material to this article:

References

- Bindu S., Mazumder S., Bandyopadhyay U. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: A current perspective. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Deng H., Cui H., Fang J., Zuo Z., Deng J., Li Y., Wang X., Zhao L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget. 2018 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Gong R., Shi X., Yang D., Zhang G., Lu A., Yue J., Bian Z. Halofuginone and artemisinin synergistically arrest cancer cells at the G1/G0 phase by upregulating p21Cip1 and p27Kip1. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi B.T., Lee J.H., Ko W.S., Kim Y.H., Choi Y.H., Kang H.S., Kim H.D. Anti-inflammatory effects of aqueous extract from Dichroa febrifuga root in rat liver. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Almeida P.D.O., Boleti A.P.D.A., Rüdiger A.L., Lourenço G.A., Da Veiga Junior V.F., Lima E.S. Anti-inflammatory activity of triterpenes isolated from Protium paniculatum oil-resins. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/293768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L., Du D.H., Chen B., Ding Y., Zhang T., Xiao W. Anti-inflammatory activity of sanjie zhentong capsule assessed by network pharmacology analysis of adenomyosis treatment. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2020 doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S228721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-González A., Núñez-López G., Morel S., Amaya-Delgado L., Sandoval G., Gschaedler A., Remaud-Simeon M., Arrizon J. Functionalization of natural compounds by enzymatic fructosylation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho K.Y., Gwee K.A., Cheng Y.K., Yoon K.H., Hee H.T., Omar A.R. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in chronic pain: Implications of new data for clinical practice. J. Pain Res. 2018 doi: 10.2147/JPR.S168188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang C.S., Fu F.Y., Huang K.C., Wang C.Y. Pharmacology of ch’ang shan (Dichroa febrifuga), a Chinese antimalarial herb [16] Nature. 1948 doi: 10.1038/161400b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong E.J., Bae J.Y., Rho J.R., Kim Y.C., Ahn M.J., Sung S.H. Anti-inflammatory triterpenes from Euonymus alatus Leaves and twigs on lipopolysaccharide-activated RAW264.7 macrophage cells. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2014 doi: 10.5012/bkcs.2014.35.10.2945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S., Zeng Q., Gettayacamin M., Tungtaeng A., Wannaying S., Lim A., Hansukjariya P., Okunji C.O., Zhu S., Fang D. Antimalarial activities and therapeutic properties of febrifugine analogs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005 doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.3.1169-1176.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M.L., Park S.Y., Kim Y., Park G., Lee S.J. Halofuginone induces the apoptosis of breast cancer cells and inhibits migration via downregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Int. J. Oncol. 2014 doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.H., Ko W.S., Ha M.S., Lee C.H., Choi B.T., Kang H.S., Kim H.D. The production of nitric oxide and TNF-α in peritoneal macrophages is inhibited by Dichroa febrifuga Lour. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000 doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P., Li M., Lou Y., Su F., Li H., Zhao X., Cheng Y. Antiproliferative effects of n-butyl-β-D-fructofuranoside from Kangaisan on Bel-7402 cells. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2014 doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.125175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsui Y., Miura M., Kato K. In vitro effects of febrifugine on Schistosoma mansoni adult worms. Trop. Med. Health. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s41182-020-00230-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K., Takano F., Fushiya S., Oshima Y. Potentiation by febrifugine of host defense in mice against plasmodium berghei NK65. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999 doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myung D.B., Lee J.H., Han H.S., Lee K.Y., Ahn H.S., Shin Y.K., Song E., Kim B.H., Lee K.H., Lee S.H., Lee K.T. Oral intake of hydrangea serrata (Thunb.) ser. leaves extract improves wrinkles, hydration, elasticity, texture, and roughness in human skin: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Nutrients. 2020 doi: 10.3390/nu12061588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Necas J., Bartosikova L. Carrageenan: A review. Vet. Med. (Praha) 2013 doi: 10.17221/6758-VETMED. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H.T., Vu T.Y., Chandi V., Polimati H., Tatipamula V.B. Dual COX and 5-LOX inhibition by clerodane diterpenes from seeds of Polyalthia longifolia (Sonn.) Thwaites. Sci. Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72840-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.Y., Park G.Y., Ko W.S., Kim Y.H. Dichroa febrifuga Lour. inhibits the production of IL-1β and IL-6 through blocking NF-κB, MAPK and Akt activation in macrophages. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009;125:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines M., Spector I. Halofuginone – The multifaceted molecule. Molecules. 2015 doi: 10.3390/molecules20010573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posadas I., Bucci M., Roviezzo F., Rossi A., Parente L., Sautebin L., Cirino G. Carrageenan-induced mouse paw oedema is biphasic, age-weight dependent and displays differential nitric oxide cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004 doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radmark O., Samuelsson B. 5-Lipoxygenase: Mechanisms of regulation. J. Lipid Res. 2009 doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800062-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragasa C.Y., Puno M.R.A., Sengson J.M.A.P., Shen C.C., Rideout J.A., Raga D.D. Bioactive triterpenes from Diospyros blancoi. Nat. Prod. Res. 2009 doi: 10.1080/14786410902951054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ríos, J.L., Recio, M.C., Máñez, S., Giner, R.M., 2000. Natural triterpenoids as anti-inflammatory agents. In: Studies in Natural Products Chemistry. 10.1016/S1572-5995(00)80024-1. [DOI]

- Salvemini D., Wang Z.Q., Wyatt P.S., Bourdon D.M., Marino M.H., Manning P.T., Currie M.G. Nitric oxide: A key mediator in the early and late phase of carrageenan-induced rat paw inflammation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996 doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Zhu J.B., Yan Y.Y., Zhang W., Gong X.J., Wang X., Wang X.L. Halofuginone inhibits tumorigenic progression of 5-FU-resistant human colorectal cancer HCT-15/FU cells by targeting miR-132-3p in vitro. Oncol. Lett. 2020 doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.12248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter C.A., Risley E.A., Nuss G.W. Carrageenin-Induced Edema in Hind Paw of the Rat as an Assay for Antiinflammatory Drugs. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1962 doi: 10.3181/00379727-111-27849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavala-Ocampo L.M., Aguirre-Hernández E., Pérez-Hernández N., Rivera G., Marchat L.A., Ramírez-Moreno E. Antiamoebic activity of Petiveria alliacea leaves and their main component, isoarborinol. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017 doi: 10.4014/jmb.1705.05003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.