Highlights

-

•

The majority (89%) of studies conducted to understand the experiences of family members of adult cardiac arrest patients beyond hospital discharge are observational and very few interventions exist to improve family member outcomes.

-

•

Across all studies, methodological heterogeneity with significant variability in the participants included, in the assessment tools selected, the timing of their administration relative to cardiac arrest, and outcome measures were seen.

-

•

Of a few studies (27%) reporting the race of the participants, the majority (80%) of participants identified as White or Caucasian race suggesting a significant lack of diversity in the experiences described in studies published so far.

-

•

Family members of adult cardiac arrest patients, both co-survivors and bereaved, reported significant uncertainty and persistent psychological burden after the cardiac arrest. In some studies, co-survivors reported even higher levels of distress compared to the survivors of cardiac arrest.

Keywords: Cardiac arrest, Family-centered care, Informal caregiver, Clinical outcomes, Scoping review

Abstract

Aim

Synthesise the existing literature on experiences and health outcomes of family members of adult cardiac arrest patients either after hospital discharge or death and identify gaps and targets for future research.

Methods

Following recommended scoping review guidelines and reporting framework, we developed an a priori protocol and searched five large biomedical databases for all relevant studies published in peer-reviewed journals in the English language through 8/8/2022. Studies reporting either on the experiences or health outcomes of family members of adult cardiac arrest patients who survived to hospital discharge (i.e., co-survivors) or bereaved family members were included. Study characteristics were extracted and findings were reviewed for co-survivors and bereaved family members. We summarised practice recommendations and evidence gaps as reported by the studies.

Results

Of 44 articles representing 3,598 family members across 15 countries and 5 continents, 89% (n = 39) were observational. Co-survivors described caregiving challenges and difficulty transitioning to life at home after hospital discharge. Co-survivors as well as bereaved family members reported significant and persistent psychological burden. Enhanced communication, information on what to expect after hospital discharge or the death of their loved ones, and emotional support were among the top recommendations to improve family members’ experiences and health outcomes.

Conclusion

Family members develop significant emotional burdens and physical symptoms as they deal with their loved ones’ critical illnesses and uncertain, unpredictable recovery. Interventions designed to reduce family members' psychological distress and uncertainty prevalent throughout the illness trajectory of their loved ones admitted with cardiac arrest are needed.

Introduction

A recent scientific statement by the American Heart Association on recovery and survivorship after cardiac arrest1 acknowledged the integral role of family members in the patient’s journey before, during, and after discharge from the hospital. Family members can have unique needs due to the sudden, life-threatening, and traumatic nature of the cardiac arrest event. Especially for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, family members may not just witness the event but may also be involved in alerting emergency medical services (EMS) and performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) before EMS arrival. If the loved one is hospitalised after successful resuscitation, family members witness life-sustaining treatments in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting and can face prognostic uncertainty when making critical life-or-death decisions, which may lead to decisional conflict.2, 3

With growing numbers of adult patients surviving cardiac arrest,1 the implications on family members of surviving patients (i.e., co-survivors) extend beyond the initial resuscitation and hospitalization to the management of the patient’s physical, functional, cognitive, and psychological deficits after hospital discharge. This is in addition to coordinating the patient’s medical care, which can include the management of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) or other advanced heart support devices, all while struggling to meet their own health needs and manage their psychological distress after the cardiac arrest. For other family members whose loved one does not survive resuscitation or hospitalization (i.e., bereaved), the sudden loss following a cardiac arrest has a significant impact on their emotional well-being.4 Despite growing evidence describing physical, neurocognitive, and psychological outcomes among cardiac arrest patients,1 the health outcomes among family members after a patient’s cardiac arrest remain poorly understood.

A recent scoping review identified family members’ care needs from the time of patient collapse until the determination of survival outcome.5 It highlighted the informational and psychological needs of families during and after the resuscitation period and identified potential improvements to current policies and procedures. However, a description of family members' experiences after hospital discharge, including the long-term psychosocial impact, caregiver burden, and health-related quality of life, was outside the scope of that review. Hence, this review aimed to provide a focused insight into the experiences and health outcomes of family members of adult cardiac arrest patients after hospital discharge. We identified gaps and targets for future research to support all family members of adult patients after cardiac arrest.

Methods

We followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis6 and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist7 for the conduct and reporting of this scoping review. An a priori protocol was registered with Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/ANHTG). We used Covidence,8 an online platform, to manage the review workflow.

Data sources and search strategy

We developed a comprehensive search strategy in consultation with an informationist combining the following population-concept-context search terms with the Boolean operator AND: families, cardiac arrest, outcomes (see Supplemental Methods for full search strategy). Five biomedical databases were searched through 8/8/22: MEDLINE (PubMed), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (EBSCO), PsycInfo (EBSCO), Scopus, and Embase. No filters were applied to the search. We additionally hand-searched reference lists of studies meeting the scoping review inclusion criteria. Each step of the screening process was independently performed by two team members (DAR, CED, LF) and discrepancies were discussed with a third team member until a consensus was reached.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) the study sample comprised individuals who identified as family members of adult (≥18 years) patients who experienced cardiac arrest, (2) the study either explored the qualitative experiences of family members after a patient’s cardiac arrest or quantitatively assessed family member health outcomes (e.g., indicators of psychological distress, physical symptoms, caregiver burden) after hospital discharge. We excluded studies that (1) presented only cardiac arrest patient-related outcomes or (2) were published in a non-English language.

Data charting

Data from included studies were charted by at least two team members (DAR, CED, SLA) who discussed discrepancies with a third team member until a consensus was reached. A standardised form was developed and pilot tested by the team prior to data charting. The following study characteristics were charted: title of the article, first author, publication year, geographical location, study design, study aims, sample size, family member characteristics (e.g., age, sex, relationship to patient), patient characteristics (e.g., age, sex), location of cardiac arrest (in-hospital or out-of-hospital), patient outcome at hospital discharge (i.e., survival or death), health outcomes, measurement tools utilised, data collection time points relative to cardiac arrest, key findings, and recommendations made by authors.

Data synthesis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the demographic characteristics of patients and families across studies. We compared findings (i.e., themes) from qualitative studies and identified common themes across studies. For quantitative studies, we identified outcomes measured across studies and synthesised study findings (e.g., symptom prevalence) by the outcome. Findings for co-survivors and bereaved family members were described separately when applicable due to theoretical differences in the type of psychological and physical symptoms and the instruments utilised to measure outcomes among these groups (e.g., caregiver burden among co-survivors, prolonged grief symptoms among bereaved family members). Using the JBI Framework9, 10 we assigned studies a level of evidence. We summarised practice recommendations made by authors and identified gaps in the existing literature.

Results

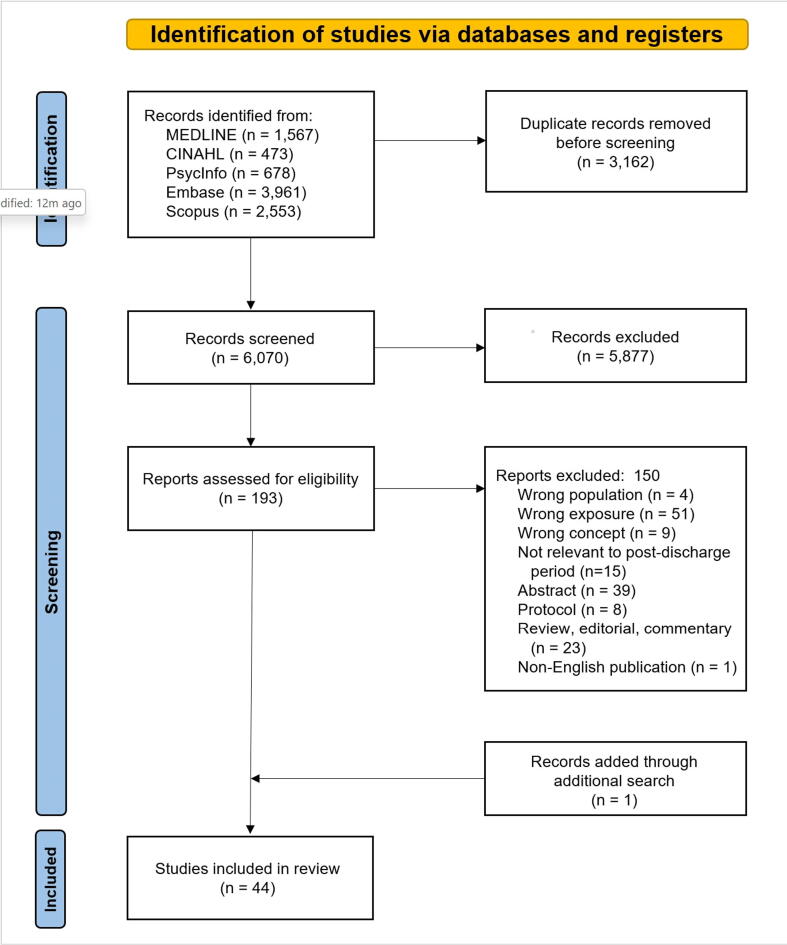

The initial search strategy yielded 6,070 records (Fig. 1). After title and abstract screening, 193 full-text records were reviewed for eligibility and 150 were excluded (additional details are provided in Supplemental Results). One additional record was identified through a hand search that met the inclusion criteria. In total, 44 studies were included in the review.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram to show the study selection process.

Detailed characteristics of included studies are provided in Tables 1 and 2. Though studies date back to 1971, over two-thirds (n = 38) were published within the last decade (2012–2022). The review encompassed studies conducted across 15 countries and 5 continents, with the highest number of studies conducted in the United States (n = 18) and Sweden (n = 11). Of 3,598 family members represented in this review, ages ranged from 28-71 years, 72% (n = 2,105) identified as women, and 67% (n = 1,939) were either spouses or partners. Only 12 studies reported data on participant race and ethnicity; of those 596 participants, 80% (n = 476) identified as White or Caucasian. Though the location of cardiac arrest varied by study, roughly half (n = 23) of all studies focused exclusively on experiences and health outcomes in the context of an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics.

| Participant Characteristics | Evidence Level | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Author, year Country |

Study design | Aims | Cardiac arrest setting | Data collection time points* | Sample size (n)† | Age (y) | Female (%) | Spouse/partner (%) | Race/ethnicity | Status at study enrollment | JBI Category; Rating |

| Armand et al., 2021 Netherlands |

Obs; Quant | Examine whether acute traumatic stress is associated with PTSD symptoms in patients who have had a CA and their partners | Mixed (>OHCA) | 3 wk, 3 mo, 1 y | 97 | 57 [NR]; range 24–79 |

88% | 100% | NR | Co-survivor | Prognosis; 3.b |

| Auld et al., 2021 USA |

Int; Quant | Examine differential responses in intervention effect among partners from the Patient plus Partner RCT based on outcome trajectory across 12 mo | NR | hospital discharge, 3 mo, 6 mo, and 12 mo | 301 | 62 (12) | 74% | 100% | Caucasian 83% | Co-survivor | Effectiveness; 1.c |

| Beesems et al., 2014 Netherlands |

Obs; Quant | Assess neurocognitive function and quality of life of patients 6–12 mo after CA, the impact on the caregiver, and the relationship between overall performance category and cerebral performance category at hospital discharge and level of functional independency and cognitive function at follow-up | OHCA | median 9 (range 6–13) mo | 197 | NR | NR | 84% | NR | Co-survivor | Effectiveness; 4.b |

| Bohm et al., 2021 Sweden, Denmark, Italy, Netherlands, UK |

Obs; Quant | Describe burden and health-related quality of life among caregivers of OHCA survivors and explore potential association with cognitive function of survivors | OHCA | 6 mo | 272 | 58 (18) | 83% | NR | NR | Co-survivor | Effectiveness; 4.b |

| Brinkrolf et al., 2021 Germany |

Obs; Quant | Analyze bystanders' psychological processing of OHCA and examine the potential impact of bystanders performing resuscitation and the influence of the relationship between bystander and patient | OHCA | median 18 (range 7–47) d | 54 | NR | NR | 65% | NR | NR | Effectiveness; 4.b |

| Carlsson et al., 2020 Sweden |

Obs; Qual | Illuminate meanings of losing a close person following SCA | Mixed (>OHCA) | range 6–16 mo | 12 | 50.5 [NR]; range 25–78 |

67% | 30% | NR | Bereaved | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| Carlsson et al., 2021 Sweden |

Obs; Quant | Describe symptoms of prolonged grief and self-reported health among bereaved family members of persons who died from SCA, with comparisons between spouses and non-spouses | Mixed (>OHCA) | 6 mo | 108 | 61 [51.5–71] | 69% | 33% | NR | Bereaved | Effectiveness; 4.b |

| Carlsson et al., 2022 Sweden |

Obs; Quant | Explore the associations between symptoms of prolonged grief and psychological distress and identify factors associated with symptoms of prolonged grief and psychological distress among bereaved family members of peresons who died from SCA | Mixed (>OHCA) | 6 mo | 108 | 61 [NR]; range 25–87 |

69% | 33% | NR | Bereaved | Effectiveness; 4.b |

| Case et al., 2021 Australia |

Obs; Qual | Explore the psychological adjustment and experiential perspectives of survivors and families in the second year after OHCA | OHCA | median 66 wk, (range 14–19 mo) | 12 | 49.1 (17.8) | 67% | 75% | NR | Co-survivor | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| Compton et al., 2009 USA |

Obs; Quant | Assess symptoms of PTSD associated with witnessing unsuccessful out-of-hospital CPR on a family member | OHCA | witnesses: 79 (range 70–109) d; non-witnesses: 84 (range 68–141) d | 54 | NR (n=31 or 57% were >60 years) |

63% | 48% | White 85% | Bereaved | Effectiveness; 3.c |

| Compton et al., 2011 USA |

Obs; Quant | Compare bereavement-related depression and PTSD symptoms among CPR patients' family members who remained in the waiting room of an urban ED with those who were invited to witness CPR | NR | 30 and 60 d | 65 | 55.7 (14.3) | 68% | 35% | African American 75% | Bereaved | Effectiveness; 2.c |

| Dichman et al., 2021 Denmark |

Obs; Qual | Generate knowledge about how relatives of OHCA survivors experience the transition between hospital and daily life | OHCA | range 3–134 mo | 23 | range 31–89 | 74% | 96% | NR | Co-survivor | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| Dobson et al., 1971 UK |

Obs; Qual | Explore CA survivors' attitude and feelings about their experience and to assess their psychological, social, and physical adjustment | Mixed | range 6–24 mo | 17 | NR | 94% | 100% | NR | Co-survivor | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| Doolittle et al., 1995 USA |

Obs; Qual | Identify and explore phenomena experienced by aborted SCD survivors and their spouses and determine implications for care | Mixed (>OHCA) | baseline: within 3 wk (mean 10.2 d); follow-up: 6–8 wk, 12–15 wk, 22–25 wk | 30 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Co-survivor | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| Dougherty et al., 1994 USA |

Obs; Quant | Describe psychological reactions, neurological sequelae, and family adjustment following SCA during the first year of recovery | OHCA‡ | hospital discharge, 1 mo, 3 mo, 6 mo, and 1 y | 15 | 53 (9)§ | 87%§ | 100% | African American 7%, White 93%§ | Co-survivor | Prognosis; 3.b |

| Dougherty et al., 1995 USA |

Obs; Quant | Compare psychological reactions and family adjustment after SCA and ICD implantation in survivors who did and did not experience defibrillatory shocks the first year of recovery | OHCA | hospital discharge, 1 mo, 3 mo, 6 mo, and 1 y | 15 | 53 (9)§ | 87%§ | 100% | African American 7%, White 93%§ | Co-survivor | Effectiveness; 3.c |

| Dougherty et al., 2000 USA |

Obs; Qual | Explore individual and family experiences after SCA and AICD implantation during the first year of recovery, specifically addressing the domains of concern expressed and helpful strategies used by participants | OHCA‡ | hospital discharge, 1 mo, 3 mo, 6 mo, and 1 y | 15 | 53 (9) | 87% | 100% | African American 7%, White 93% | Co-survivor | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| Dougherty et al., 2004 USA |

Obs; Qual | Describe the domains of concern of intimate partners of SCA survivors and outline strategies used by partners of SCA survivors in dealing with the concerns and demands of recovery in the first year after ICD implantation | OHCA‡ | hospital discharge, 1 mo, 3 mo, 6 mo, and 1 y | 15 | 53 (9) | 87% | 100% | African American 7%, White 93% | Co-survivor | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| Dougherty et al., 2009 USA |

Obs; Quant | Describe the physical functioning, psychological adjustment, healthcare utilization, and impact on the intimate relationship of intimate partners of persons receiving an ICD in the first year after implantation | NR | hospital discharge, 1 mo, 3 mo, 6 mo, and 1 y | 110 | 60.96 (12.87) | 84% | 100% | American Indian 1.1%, Caucasian 96.9%, Mixed 1.1%, Declined response 1% | Co-survivor | Prognosis; 3.b |

| Ingles et al., 2016 Australia |

Obs; Quant | Assess psychological functioning after the SCD of a young relative and identify factors that correlate with adverse outcomes | OHCA|| | mean 6.3±4.6 y | 103 | 44 (16) | 58% | 4% | NR | Bereaved | Effectiveness; 4.b |

| Israelsson et al., 2020 Sweden |

Obs; Quant | Investigate if a distressed personality and perceived control among CA survivors and their spouses were associated with their own and their partner's health-related quality of life. | Mixed (>IHCA) | 6 mo | 126 | 64.4 (10.9) | 85% | 100% | NR | Co-survivor | Effectiveness; 4.b |

| Jabre et al., 2013 France |

Int; Quant | Evaluate the effect of offering family presence during CPR on family members' PTSD-related symptoms, medical efforts at resuscitation, the well-being of the healthcare team, and the occurrence of medicolegal claims | OHCA | 90 d | 570 | 57 (16) | 64% | 55% | NR | Mixed (96% bereaved at day 28) |

Effectiveness; 1.c |

| Jabre et al., 2014 France |

Int; Quant | Evaluate the psychological consequences among family members given the option to be present during the CPR of a relative, compared with those not routinely offered the option. | OHCA | 1 y | 408 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Effectiveness; 1.c |

| Larsen et al., 2022 Denmark |

Obs; Qual | Explore relatives' experiences with OHCA and the following months after | OHCA | mean 9 (range 2–18) mo | 12 | 69 (NR) | 83% | 100% | NR | Co-survivor | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| Larsson et al., 2013 Sweden |

Obs; Qual | Describe relatives' experiences during the next of kin's hospital stay after surviving a CA treated with hypothermia at an intensive care unit | NR | hospital discharge and 1.5–6 wk | 20 | 52 (NR); range 20–70 |

65% | 65% | NR | Co-survivor | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| Mayer et al., 2013 USA |

Obs; Qual | Describe the bereavement experiences of families who survived the SCD of a family member and identify meanings of loss | OHCA|| | mean 2.1 (range 1–5) y | 17 | 41.8 (NR); range 22–60 |

71% | 29% | NR | Bereaved | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| McDonald et al., 2020 Australia |

Obs; Quant | Investigate the needs of parents who have experienced the SCD of their child (≤ 45 y) | OHCA|| | range 2–17 y | 38 | 59 (11) | 79% | 0% | NR | Bereaved | Effectiveness; 3 |

| Metzger et al., 2019 Switzerland |

Obs; Quant | Assess prevalence and risk factors for depression and anxiety among relatives of OHCA patients at 90 d after the event and explore associations of patient and relative risk factors at baseline with symptoms at 90 d | OHCA | before hospital discharge and 90 d post-discharge | 101 | 55.1 (14.4) | 72% | 59% | NR | Mixed (51% bereaved) |

Prognosis; 2 |

| Mion et al., 2021 UK |

Obs; Mixed | Investigate the problems encountered by survivors and their families after OHCA, their experience of follow-up care and what improvements they felt could be made to the follow-up appointment to make it more relevant and targeted | OHCA | median 2 y (range 19 d-25 y); 72% experienced CA within 5 y | 39 | 52 [NR]; range 15–73 |

69% | NR | NR | Co-survivor | Effectiveness; 4.b |

| Moulaert et al., 2015 Netherlands |

Int; Quant | Evaluate the effectiveness of a brief nursing intervention on outcomes among CA survivors and caregivers through 1 y | NR | 2 wk, 3 mo, 12 mo | 155 | 55 (12) | 86% | 89% | NR | Co-survivor | Effectiveness; 1.c |

| Presciutti et al., 2021 USA |

Obs; Quant | Estimate the proportion of clinically significant PTS in both CA survivors with good neurologic recovery and informal caregivers and examine the association between PTS and physical, psychological, and social quality of life | Mixed (>OHCA) | mean 43.2±36.4 mo | 52 | 48.7 (13.7) | 87% | 83% | Non-White 11.5%, White 88.5% | Co-survivor | Effectiveness; 4.b |

| Presciutti et al., 2022 USA |

Obs; Quant | Elucidate gaps in the provision in cognitive and psychological resources among CA survivors with good neurologic recovery and informal caregivers | Mixed (>OHCA) | mean 43.2 (range 17–55) mo | 52 | 48.7 (13.7) | 87% | 83% | Non-White 11.5%, White 88.5% | Co-survivor | Effectiveness; 4.b |

| Pusswald et al., 2000 Austria |

Obs; Mixed | Explore persistent neuropsychiatric symptoms, global function and life situation of OHCA survivors after inpatient rehabilitation and to evaluate quality of life in families | OHCA | 25 mo after inpatient rehabilitation | 10 | NR | NR | 100% | NR | Co-survivor | Effectiveness; 4.b |

| Rosenkilde et al., 2022 Denmark |

Obs; Qual | Explore the experience of burden for family caregivers of OHCA survivors | OHCA | “varied from months to a few years” | 25 | 55 (NR); range 31–89 |

68% | 96% | NR | Co-survivor | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| Sawyer et al., 2016 USA |

Obs; Qual | Identify themes unique and important to CA survivors and their friends and/or family members | Mixed | n=8 (21%) within 1y; n=6 (15%) within 6–30 y | 39 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Co-survivor | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| Simons et al., 1992 USA |

Obs; Qual | Explore the experiences and emotional responses of wives of CA survivors | NR | mean 18±9 (range 7–39) wk | 9 | 55.7 (13) | 100% | 100% | Caucasian 100% | Co-survivor | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| Soleimanpour et al., 2017 Iran |

Int; Quant | Study the effect of a nurse providing support to relatives present during resuscitation on relatives' psychological condition | IHCA | 90 d | 133 | intervention group: 40.45 (10.27); control group: 40.42 (10.36) |

45% | 7% | NR | Mixed (>75% bereaved) |

Effectiveness; 2.c |

| van Wijnen et al., 2017 Netherlands |

Obs; Quant | Gain insight in the functioning of caregivers of CA survivors at 12 mo after a CA, the course of caregiver wellbeing during the first year, and factors associated with a higher care burden at 12 mo | NR | 2 wk, 3 mo, 12 mo | 195 | 57 (12) | 85% | 88% | NR | Co-survivor | Prognosis; 3.b |

| van't Wout Hofland et al., 2018 Netherlands |

Obs; Quant | Determine the impact of a CA on long-term daily functioning and quality of life in caregivers of survivors 2 y after the CA and study the relationship between attendance/participation during CPR and long-term functioning | NR | 2 y | 57 | 56.9 (12.0) | 90% | 91% | NR | Co-survivor | Prognosis; 3.b |

| Wachelder et al., 2009 Netherlands |

Obs; Quant | Determine the level of functioning of OHCA survivors 1–6 years later and evaluate the predictive value of medical variables on long-term functioning | OHCA | range 1–6 y | 42 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Co-survivor | Effectiveness; 4.b |

| Wallin et al., 2013 Sweden |

Obs; Qual | Describe relatives’ experiences of needing support and information and the impact on everyday life 6 mo after a significant other survived CA treated with therapeutic hypothermia at an intensive care unit | NR | 6 mo | 20 | 55 (NR); range 20–70 |

70% | 65% | NR | Co-survivor | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| Wisten et al., 2007 Sweden |

Obs; Qual | Elucidate the perceived support and needs of bereaved parents confronted with SCD in a young son or daughter | OHCA | mean 8 (range 5–12) y | 28 | NR | NR | 0% | NR | Bereaved | Meaningfulness; 3 |

| Yeates et al., 2013 Australia |

Obs; Mixed | Evaluate psychological wellbeing and experiences of first-degree relatives who presented for evaluation following SCD in the young (≤ 40 y) | NR | mean 4±2 y | 50 | 51 (15) | 58% | 0% | NR | Bereaved | Effectiveness; 4.b |

| Zimmerli et al., 2014 Switzerland |

Obs; Quant | Study PTSD frequency and risk factors in relatives of OHCA patients | OHCA | mean 2.6±1.7 y | 101 | 58.1 (12.2) | 70% | 71% | NR | Mixed (56% bereaved) |

Effectiveness; 4.b |

Note. Age data reported as mean (standard deviation) or median [interquartile range] unless otherwise reported. CA cardiac arrest; y years; JBI Joanna Briggs Institute; Obs observational; Quant quantitative; PTSD post-traumatic stress disorder; OHCA out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; wk week(s); mo month(s); NR not reported; Int interventional; RCT randomised controlled trial; Qual Qualitative; SCA sudden cardiac arrest; HCP healthcare provider; CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation; d day(s); ED emergency department; SCD sudden cardiac death; ICD implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; AICD automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; ADLs activities of daily living; PTS post-traumatic stress; IHCA in-hospital cardiac arrest; ICU intensive care unit; HRQoL health-related quality of life; ECPR extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation; SABI severe acute brain injury; EMS emergency medical services.

*Time lapsed since cardiac arrest.

†Number of family members of cardiac arrest patients.

‡Inferred based on Dougherty et al., 1995.

§Inferred based on Dougherty et al., 2000, 2004.

||Inferred given sudden cardiac death.

Table 2.

Key Study Findings.

| Author, year | Key findings |

|---|---|

| Armand et al., 2021 | 45–48% of partners exhibited severe PTSD symptoms, a higher rate than 26–28% of patients; higher acute traumatic stress severity was significantly positively associated with higher PTSD symptom severity at 3 mo and 1 y post-resuscitation, both in patients and partners, with the strongest association for women compared with men |

| Auld et al., 2021 | Dyadic intervention was more effective in improving mental health, caregiver burden, and self-efficacy among partners with relatively poorer health (i.e., poorer mental health, higher caregiver burden, lower self-efficacy) over 12 mo follow-up |

| Beesems et al., 2014 | 16% of caregivers experienced high burden; risk factors for increased caregiver strain included patient's level of dependency and cognitive function |

| Bohm et al., 2021 | 28% of caregivers reported high caregiver burden; caregivers of cognitively impaired patients reported higher burden and worse quality of life in 5 of 8 domains |

| Brinkrolf et al., 2021 | One out of three bystanders of OHCA suffers signs of pathological psychological processing, independent of bystander age, gender, and relationship to the patient; performing resuscitation seems to help coping with witnessing OHCA |

| Carlsson et al., 2020 | Participants described pending between life and sudden loss: fluctuating between hope and despair during resuscitation, needing to feel meaning in the act of resuscitation, wanting to feel taken care of by healthcare professionals, and needing to know that everything possible was done. Proceeding with life after sudden loss involves: being left with questions or without answers, seeking consolation in the sudden nature of death, being reminded of death as a part of life, experiencing an unfamiliar body, wanting to be acknowledged as a bereaved family member, and suddenly losing life as it was known |

| Carlsson et al., 2021 | 20% of family members reported prolonged grief and other health problems, especially anxiety; spouses reported more problems with prolonged grief and self-reported health compared with non-spouses |

| Carlsson et al., 2022 | Significant associations between prolonged grief and anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress were identified. Perceived social support and professional support were associated with all outcomes. HCPs should provide support during resuscitation and during bereavement. |

| Case et al., 2021 | Themes of trauma exposure, survivor adjustment problems, family impact, and areas for service improvement highlighted the need for clear, sensitive communication and comprehensive post-discharge follow-up care |

| Compton et al., 2009 | Witnesses' total PTSD symptom scores were nearly 2 times higher than nonwitnesses; 2 PTSD symptom subscales (avoidance and increased arousal) were higher for witnesses |

| Compton et al., 2011 | Bereavement-related depression and PTSD symptoms were commonly reported, but no significant differences were found at either 30 d and 60 d between those who witnessed CPR and those who did not |

| Dichman et al., 2021 | Family members reported their presence in the hospital as necessary, their need for communication with healthcare professionals on the cardiac ward, and their experience of an abrupt disappearance of the system post-discharge |

| Dobson et al., 1971 | Spouses experience considerable emotional stress at the time of illness and during the early convalescence at home; 9 reported not knowing how to treat their spouse, finding them to be dependent and irritable; 6 felt unable to express their own needs or aggressive feelings in case it had a detrimental effect on the husband; all 13 who were aware that a CA had occurred reported the more information they received, the less isolated they felt |

| Doolittle et al., 1995 | Spouses and patients experience different focus/reference points for future decision making: for spouses, it was the arrest and for patients, it was pre-arrest life; these different reference points led to different concerns, from which spousal protectiveness and entrapment emerged |

| Dougherty et al., 1994 | Anxiety, depression, anger, stress, and confusion were highest at hospital discharge and decreased over 1 y; spouses reported fewer coping strategies and lower dyadic satisfaction than patients; family social support was lower than previously established norms at all periods during the first year of recovery |

| Dougherty et al., 1995 | Families reported lower levels of family support and marital satisfaction during the first year after SCA and ICD implantation; anxiety, depression, anger, and stress levels were higher among patients and family members if the defibrillator fired |

| Dougherty et al., 2000 | Participants identified the following domains of concern which can be used to design nursing intervention programs: preventive care, dealing with AICD shocks, emotional challenges, physical changes, ADLs, partner relationships, and dealing with HCPs |

| Dougherty et al., 2004 | Participants reported strategies to address the following identified domains of concern: care of the survivor, my (partner) self-care, relationship, ICD, money, uncertain future, health care providers, family |

| Dougherty et al., 2009 | At hospital discharge, partners report the greatest care demands and high impact on the intimate relationship; partners' physical health, symptoms, and depression significantly declined over the first year; anxiety was significantly reduced over time but remained elevated after 1 y |

| Ingles et al., 2016 | 20.6% of family members report prolonged grief and 44% reported PTS symptoms; family members reported more severe depression, anxiety, and stress than the general population; mothers and those who witnessed the death reported higher prolonged grief, higher post traumatic stress symptoms, lower quality of life, and higher depression and anxiety scores |

| Israelsson et al., 2020 | A significant association between type D personality and health-related quality of life in spouses was found; type D personality and perceived control in patients were associated with health-related quality of life of spouses |

| Jabre et al., 2013 | At 3mo, family presence during CPR was associated with lower frequency of anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms and did not interfere with medical efforts, increase stress in the health care team, or result in medicolegal conflicts |

| Jabre et al., 2014 | At 1y, psychological benefits persist for family members offered the possibility to witness CPR (significantly less PTSD, depressive symptoms, complicated grief) |

| Larsen et al., 2022 | Relatives experienced high distress and anxiety during the OHCA, confronted with the possibility of bereavement while watching from the sideline with fearful eyes, and after the OHCA, experiencing a troubled time with anxiety and edginess as they tried to adapt to a new normality. |

| Larsson et al., 2013 | Relatives described a first period of chaos (e.g., fear, uncertainty), the need to feel secure with support and information in a difficult situation during hospitalization, and the impact on everyday life after the CA (i.e., increased responsibility, concerns for the future, and changes in the next of kin) |

| Mayer et al., 2013 | Bereavement experience includes sudden cardiac death, saying goodbye, grief unleashing volatile emotional reactions, life going on but never back to normal, and searching for meaning in loss |

| McDonald et al., 2020 | Medical needs were identified as the most important domain, followed by psychosocial, spiritual, and financial; the two most endorsed needs were 'To have the option of whether or not you would pursue genetic testing for yourself or family members' and 'To understand what happened'; psychosocial information and support needs were reported as the most unmet need (endorsed by 54%); medical information and support needs were reported as unmet by almost 1/3 |

| Metzger et al., 2019 | Depression and anxiety were reported by 17% and 13% of relatives, respectively; witnessing CPR, lower overall satisfaction with information and decision making during ICU, anxiety at 90 d, lower perceived health status at 90 d, increased use of psychotropic drugs at 90 d, patient mortality at 90 d, and worse patient neurological outcome at 90 were associated with depression; relatives' unemployment at ICU admission and lower perceived health status at 90 dwere associated with anxiety |

| Mion et al., 2021 | 95% of family members reported lingering psychological difficulties after hospital discharge; only 11 (28%) were able to access support; 95% advocated for a dedicated follow-up appointment for relatives of survivors |

| Moulaert et al., 2015 | Caregivers reported higher anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress than patients; the intervention did not result in significant improvements in caregiver outcomes |

| Presciutti et al., 2021 | 35% of caregivers (compared to 25% of survivors) reported clinically significant PTS scores; greater PTS scores, younger age at CA, fewer months since CA, and low-to-medium income were associated with worse HRQoL scores |

| Presciutti et al., 2022 | A greater proportion of caregivers reported provision of resources (discussions about cognitive symptoms, scheduled neurologist and cognitive resource appointments) compared to survivors, highlighting the vital role of caregivers in coordinating follow-up care upon hospital discharge |

| Pusswald et al., 2000 | 60% of spouses suffered from psychosomatic problems (lack of interests, sleep disturbances, restlessness, loss of libido, reduction of impulse, loss of appetite/weight); 50% complained of lack of social suppport |

| Rosenkilde et al., 2022 | Caregivers reported feeling unexpectedly alone and invisible, having fear of losing their loved one, and experiencing difficulties adjusting to a new everyday life. Caregiving following OHCA includes several perspectives, emotional, social, socioeconomic, and practical changes within the family |

| Sawyer et al., 2016 | Major themes include recognition of loved one's memory loss; a lack of information at discharge, including expectations after discharge; and concern for the patient experiencing another CA |

| Simons et al., 1992 | Wives experienced a great deal of fear related to the near-loss and possibility of recurrence and felt a great personal responsibility for prevention of another event; AICD served as both a source of security and anxiety; husbands' driving restrictions caused conflict and appeared to epitomise the dependence–independence issues after CA; other emotions included anger over lifestyle changes and improved intimacy |

| Soleimanpour et al., 2017 | Anxiety, depression, and PTSD were significantly less prevalent in the intervention group (i.e., those who received support from a nurse during resuscitation) at 90 d |

| van Wijnen et al., 2017 | Among caregivers at 12 mo, caregiver strain was high in 15%, anxiety and depression were present among 25% and 14%, respectively, and caregiver strain correlated significantly with anxiety/depression, quality of life, and caregiver's view of patient cognition; overall wellbeing improved over time/during the first year |

| van't Wout Hofland et al., 2018 | Mean PTSD, fatigue, and caregiver strain scores were increased compared to the general population; nearly 30% reported clinically significant PTSD scores; quality of life scores equated to those of the general population; those who witnessed the resuscitation experienced significantly more trauma-related stress compared to those who did not witness |

| Wachelder et al., 2009 | Caregivers reported stress related responses, feelings of anxiety and lower quality of life; 17% reported high caregiver strain which was associated with the patient’s level of functioning |

| Wallin et al., 2013 | Everyday life was still affected 6mo after the event, involving increased domestic responsibilities, restrictions in social life, and constant concern for the patient; feeling hope for the future involved support from trusted persons, gratitude for their own health and to those involved during/after the event, and confidence in recovery |

| Wisten et al., 2007 | 1/3 had no contact with the ED, 1/3 had been disappointed after meeting ED caregivers who did not act with sensitivity and consistency, 1/3 were more or less satisfied with the ED handling; a majority experienced a lack of follow-up care, left mainly to themselves to find information and support; evidence, reconstruction, explanation, and sensitivity were identified as being particularly important |

| Yeates et al., 2013 | Relatives had significantly higher mean anxiety and depression scores compared to the general population; mothers had significantly higher anxiety and depression scores compared to other participants, with 53% having a score suggestive of anxiety disorder; factors were reported as helpful with coping (e.g., information and support, formal counseling sessions, time) |

| Zimmerli et al., 2014 | PTSD was detected in 40% of relatives; predictors included female gender, history of depression, and family perception of the patient's therapy as insufficient |

Note. PTSD post-traumatic stress disorder; OHCA out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; SCA sudden cardiac arrest; HCP healthcare provider; CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ED emergency department; ICD implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; AICD automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; ADLs activities of daily living; PTS post-traumatic stress; ICU intensive care unit; HRQoL health-related quality of life.

Of the 44 studies evaluating experiences after hospitalization or long-term health outcomes, more than half (n = 28) were focused on co-survivors with more than one-fourth (n = 14) focused on bereaved family members; few (n = 2) did not specify the patient’s outcome. Most studies (89%; n = 39) were observational. A wide range of health outcomes (e.g., psychological symptoms, caregiver burden, health-related quality of life [HRQoL]) was measured using a variety of instruments (summary of outcomes and instruments are detailed in Supplemental Table 1). Four studies of interventions to improve outcomes among family members were identified; only two were delivered after the hospitalization.11, 12.

Major findings

Co-survivors described challenges in caring for patients with new physical, cognitive, and emotional needs

Cardiac arrest patients suffer from a host of emotional issues, such as anxiety, loss of confidence, personality changes, anger, frustration, depression, fatigue, and irritability.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Due to anoxia and brain injury, impairments in cognition13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 and physical function resulted in patients becoming more dependent on co-survivors for support.14, 16, 20, 21, 22, 23 The transition from hospital to daily life at home was reportedly difficult; co-survivors felt under-informed and ill-equipped to manage post-cardiac arrest sequelae.17 They found that post-discharge support was difficult to locate16, 17 and that primary care was insufficient to meet their needs.15 Co-survivors encountered feelings of doubt, frustration, powerlessness, and lack of control.15, 17, 23 Managing their own needs on top of the patients complicated the transition to life at home.13, 14, 16, 17, 21, 23, 24 Fifteen to 30% of co-survivors screened positive for significant caregiver burden.25, 26, 27, 28 This demand for caregiving expanded past the patient to other family members, which may include caring for younger children and keeping other relatives updated.18 Caregiving responsibilities caused stress and sleep disturbances17, 18 with roughly 20% reporting fatigue29 and 25% reporting poor sleep.24 Co-survivors felt lonely and isolated in caregiving,16, 17, 20, 23 especially without someone to share their worries and emotions.23 Their needs fell second to those of their loved ones and they failed to care for themselves.17 Further, the demands of caregiving and change in the patient’s work status led to strain and worry about the family’s financial future.20, 17, 18

Co-survivors experienced psychological burden and poor quality of life after cardiac arrest

Co-survivors commonly reported anxiety after returning home,17, 18, 21, 22, 23 with 25% to 33% reporting clinically significant symptoms.11, 24, 26, 28 Many reported fear of recurrence of cardiac arrest and death. This uncertainty was believed to be the root cause of continual anxiety.16, 17, 19, 22, 30 They also reported symptoms of depression,20 with the prevalence of clinically significant symptoms ranging from 10% to 60%.20, 26, 28 Post-traumatic stress symptoms were exhibited by 35% to 50% of co-survivors.26, 28, 29, 31, 32 Though symptoms typically decreased over time,33, 34 burden could persist for months to years and was higher for co-survivors than for patients.12 Even a year after the cardiac arrest, one in four reported persistent anxiety,26 one in seven reported persistent depression,26 and nearly-one in two reported persistent post-traumatic stress.31

Witnessing the cardiac arrest causes unique, long-lasting trauma. Co-survivors reported higher levels of distress compared to patients12, 29 which can be attributed in part to witnessing the event.29 Witnessing the cardiac arrest creates fundamentally different reference points between the co-survivor and the patient.30 While the patient may have no memory of the cardiac arrest, co-survivors who witnessed it feared its recurrence and became overprotective of the patient.14, 23, 30 This overprotectiveness made it difficult for the co-survivor to work full-time, caused stress in their relationship with the patient, led to changes in family structures and roles, and negatively impacted other social relationships.22, 16, 17, 18

Several patient-related, as well as co-survivors-characteristics associated with poor health outcomes among co-survivors such as lower HRQoL,26 high psychological symptom burden32, and caregiver25 burden, have been identified. Factors related to the patient include younger age,32 lower perceived control,36 physical dependency and cognitive impairment upon hospital discharge,25, 27, and receipt of ICD shocks after hospital discharge.37 Co-survivor factors include elevated levels of acute traumatic stress,31 being a bystander to CPR,38 greater perceptions of patient’s cognitive failures,26 low-to-medium income.32 Supplemental Table 2 provides additional details on the explored risk factors associated with poor outcomes.

Bereaved family members experienced a unique psychological burden after cardiac arrest

Family members’ lives were forever changed after losing a loved one to cardiac arrest.39 They lived their lives differently after facing a reminder of their mortality and the fragility of life. They had to take over responsibilities, manage changed family dynamics, and struggled to find a sense of meaning.39, 40 Psychological distress among bereaved family members was similar to co-survivors. Anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress affected 18–56%,4, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 16–41%,4, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 and 6–79%4, 41, 42, 44, 46, 47 of bereaved family members, respectively. Symptoms of prolonged grief disorder occurred among 18% to 36%4, 42, 44 and tended to co-occur with other markers of psychological distress.48 Factors (i.e., family member-related) associated with higher symptom burden include female gender,45, 47 mother related to the patient,44, 45 spouse relation to the patient,4 lower perception of their health status,43 history of depression47 and use of psychotropic drugs,43 unemployment at ICU admission,43 perceptions of insufficient care for the patient,47 low perceived social support,48 and witnessing CPR43, 49 (see Supplemental Table 2 for further details).

Very few interventions exist to improve family member outcomes

There have been only two randomised controlled trials that tested interventions aimed to improve co-survivor outcomes.11, 12 Both interventions were dyadic (i.e., engaging both patients and family members) and were delivered after hospital discharge. Study findings were mixed. The first utilised a semi-structured self-management intervention delivered over 1–6 sessions during the first month after discharge. The intervention arm received an evaluation of their cognitive and emotional problems and provided corresponding information and professional support. Compared to the usual healthcare group, the intervention arm did not demonstrate significant improvements in psychological stress, caregiver burden, or HRQoL at the one-year follow-up.12 The second study enrolled participants with an ICD for any reason. Only 40% of participants received ICD for secondary prevention after cardiac arrest. The intervention involved written and video information relating to “(1) how partners could support the care of the ICD patient, (2) partner self-care, (3) how the patient-partner relationship might be influenced by the ICD, (4) ICD function and components, (5) planning for the future, and (6) other topics of interest and questions” in addition to nurse telephone support over the first 12 weeks after discharge with an ICD. Compared to patients only, the patient and partner group had greater improvement in caregiver burden, mental health, and self-efficacy scores, among those with relatively poorer mental health.11.

The two interventional studies specifically designed for bereaved family members41, 42, 50 were delivered in the pre-hospital setting and focused on assessing the impact of family presence during CPR of their loved one. The first RCT reported lower psychological symptom burden among bereaved family members who witnessed CPR through one-year follow-up.41, 42 The other, quasi-experimental study tested the provision of emotional support by a nurse during witnessed in-hospital cardiac arrest50 and found reductions in psychological symptoms at a three-month follow-up. Despite conflicting evidence from observational studies43, 46, 49 family presence during CPR seemed to have an emotionally protective effect. No intervention studies were found for bereaved family members beyond acute hospitalization.

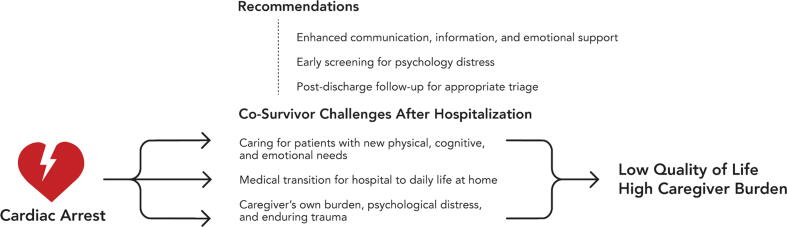

Recommendations

Findings from included studies and recommendations made by study authors (Fig. 2) suggest the following opportunities to improve outcomes for cardiac arrest family members:

-

•

Enhanced communication, including improved oral and written information for all13, 17, 18, 29 and repeated information17 for co-survivors to address what to expect (e.g., extra-cardiac sequelae) after hospital discharge, and thus removing uncertainty, have been recommended by most studies.14, 16, 17, 19, 20, 22, 35, 51 Appropriate referrals should be made and appointments scheduled to facilitate the transition from hospital to home.51 Similarly, information for bereaved family members about the cardiac arrest (e.g., cause) may facilitate processing and understanding.40, 52

-

•

Enhanced emotional support. For co-survivors, additional support should be provided for them to learn to cope with the consequences of the cardiac arrest,20, 22, 24, 29, 34 especially those who witnessed the event.29, 30 Strategies for self-care should be included.16 Emotional support for co-survivors may be better provided by other individuals who have gone through similar experiences (e.g., through peer support groups).19, 21, 23 Especially for those family members bereaved after cardiac arrest, additional support, should be provided.39, 40, 52 A focus on the family member immediately after the patient's death can help them to feel less alone, allow them to ask questions, and avoid feelings of inadequacy or future feelings of guilt.40, 52

-

•

Early screening (e.g., in-hospital) to identify family members at high risk for poor long-term health outcomes, such as PTSD.31, 32

-

•

Post-discharge follow-up for all family members, regardless of patient outcome.13, 14, 18, 21, 40, 45, 52 Healthcare providers should address the feelings and needs of co-survivors newly caring for their loved ones23, 24 and allow them to discuss their worries, clarify issues, and help them to process the event.17, 21 Follow-up care to bereaved family members (e.g., phone call or in-person visit a few days after the event) can allow them the opportunity to speak with someone if questions arise after the event.52

Fig. 2.

Gaps and recommendations made by existing studies informing behavioural interventions to improve quality of life and caregiver burden of family members of cardiac arrest survivors.

Discussion

Our unique scoping review synthesised the literature on the experiences of family members of adult patients who either survived to hospital discharge or die during hospitalization from cardiac arrest. The findings suggest that irrespective of patients’ outcomes, family members’ physical and psychological well-being can be affected for months to years. The experience of cardiac arrest is associated with the fear of recurrence and uncertainty throughout the journey. The prevalence of clinically significant levels of posttraumatic stress is higher for co-survivors (35–50%) than for cardiac arrest patients (30%) at the time of hospital discharge.26, 28, 31 With growing numbers of patients surviving cardiac arrest, surrogates must cope with their loved one's physical, cognitive, and emotional changes, and coordinate the medical care (e.g., management of an ICD), all while struggling to meet their own physical and emotional health needs. Similarly, one in five bereaved family members report symptoms of prolonged grief disorder.4, 44

Adverse health outcomes among family members of patients who experience a critical illness have been well-documented53 but are poorly understood in the context of cardiac arrest. The level of evidence was low. The majority of the studies were cross-sectional, collecting data at varying time points after cardiac arrest ranging from 19 days to 25 years after cardiac arrest. We identified significant gaps in the existing literature with marked heterogeneity in assessment tools, and varying cut-offs for clinically significant symptoms to understand the trajectory of health outcomes and journey mapping of family members after cardiac arrest. One clear limitation of the research to date is that no study reported baseline (i.e., pre-cardiac arrest) physical and psychological data; thus, it is difficult to ascertain the significance of the findings. Prospective studies with serial assessments using validated psychometric instruments would allow for a better understanding of symptom prevalence and trajectory. This would further allow for the identification of risk factors and exploration of subgroups predisposed to adverse outcomes. This empirically derived data is critical for developing behavioural interventions. Particularly for co-survivors, dyadic interventions involving patients and co-survivors are beneficial for recovery after other acute brain injuries.54, 55

Other opportunities for future observational research include a more comprehensive evaluation of family member health outcomes and a wider diversity of study participants. Nearly no study reported on physical symptoms (e.g., fatigue) and health behaviours (e.g., sleep, physical activity), outcomes which are generally underexplored among family members of critically ill patients.56 Family members have been shown to have lower physical activity, poorer dietary behaviours, and other factors which heighten their cardiovascular risk57, 58 specifically in the context of cardiovascular disease. A better understanding of the physical health implications of cardiac arrest on family members is needed. Further, data reflecting the racial and ethnic diversity of participants were often not reported, limiting the generalizability of the findings to those with diverse backgrounds.

More interventional studies to improve the well-being of family members after a loved one’s cardiac arrest are warranted.59 Regardless of cardiac arrest exposure or outcome, family members represented in this scoping review reported similar intervention needs. Many studies report findings that may serve as potential targets for intervention (e.g., information about the cardiac arrest and long-term recovery, systematic family engagement during the transition from hospital to home, enhanced psychological support, and follow-up care after the hospitalization) (Fig. 2). Despite the growing body of observational data, only two interventions for each co-survivor and the bereaved group were identified and demonstrated varying degrees of effect. Future studies should further investigate the wants and needs of families and should include preferences for intervention timing, dose, and delivery. Identifying individuals at higher risk for adverse outcomes (e.g., demographic, clinical factors) can help to further tailor interventions, minimizing heterogeneity of treatment effect60, 61 by targeting those most responsive to treatment as demonstrated in the Patient plus Partner trial conducted by Auld and colleagues.11 Nearly-two-thirds of the literature included has been published within the last 10 years, highlighting the emerging importance of the field.

Limitations

The evidence in this review is limited to the adult cardiac arrest population and excluded studies with a paediatric context. This scoping review aimed to address the broad question of identifying the types of available evidence and knowledge gaps in family members’ experience beyond hospital discharge. We strictly adhered to JBI Evidence Synthesis guidelines6 according to which the use of statistical meta-analysis or meta-synthesis is typically not conducted in a scoping review. The next steps for the field will include addressing more focused research questions via these methods (i.e., meta-synthesis and meta-analysis). Nonetheless, this scoping review has laid down the foundation of this field of research and adhered to the highest standards in its conduct and reporting.

Conclusions

This scoping review enhances our understanding of the experiences and health outcomes of family members after a loved one’s cardiac arrest by providing insight into the psychological burden and caregiving needs especially during the post-hospitalization period. Studies to date have been largely observational and are limited in their design. Future observational studies should be longitudinal and comprehensive in evaluating physical and psychological well-being among family members across the trajectory of illness and recovery, involving patient-family member dyads when able and ensuring representation from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. Investigators should engage family member stakeholders throughout the research process to ensure studies are patient- and family-centered and to guide directions for future research. Intervention development must be prioritised to improve health and well-being among family members after a loved one’s cardiac arrest.

Funding disclosures

Authors report funding during the conduct of this study from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science TL1TR001875 (CED), the National Institute for Nursing Research (MG; unrelated to submitted work), and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute R01 HL153311 (SA). We have no other disclosures/conflicts of interest to report.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Danielle A. Rojas: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Christine E. DeForge: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Sabine L. Abukhadra: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Lia Farrell: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Maureen George: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Sachin Agarwal: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank our patient and family co-survivor stakeholders for their insight and contributions to this work through the NeuroCardiac Comprehensive Care Clinic for Families (N4C-F) of cardiac arrest patients at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC). We thank Mr. John Usseglio from the CUIMC library for his assistance in developing the search strategy.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resplu.2023.100370.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Sawyer K.N., Camp-Rogers T.R., Kotini-Shah P., et al. Sudden Cardiac Arrest Survivorship: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e654–e685. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller J.J., Morris P., Files D.C., Gower E., Young M. Decision conflict and regret among surrogate decision makers in the medical intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2016;32:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiarchiaro J., Buddadhumaruk P., Arnold R.M., White D.B. Prior Advance Care Planning Is Associated with Less Decisional Conflict among Surrogates for Critically Ill Patients. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1528–1533. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201504-253OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlsson N., Alvariza A., Bremer A., Axelsson L., Arestedt K. Symptoms of Prolonged Grief and Self-Reported Health Among Bereaved Family Members of Persons Who Died From Sudden Cardiac Arrest. Omega (Westport) 2021;302228211018115 doi: 10.1177/00302228211018115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douma M.J., Graham T.A.D., Ali S., et al. What are the care needs of families experiencing cardiac arrest?: A survivor and family led scoping review. Resuscitation. 2021;168:119–141. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aromataris E., Munn Z. (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. 10.46658/JBIMES-20-01. [DOI]

- 7.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veritas Health Innovation: Covidence Systematic Review Software. Melbourne, VIC, Australia. Available at https://www.covidence.org. Accessed March 7, 2021.

- 9.Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation Working Party. JBI Levels of Evidence. 2013. Available from https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI-Levels-of-evidence_2014_0.pdf.

- 10.Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation Working Party. Supporting Document for the Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation. 2014. Available from https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI%20Levels%20of%20Evidence%20Supporting%20Documents-v2.pdf.

- 11.Auld J.P., Thompson E.A., Dougherty C.M. Profiles of partner health linked to a partner-focused intervention following patient initial implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) J Behav Med. 2021;44:630–640. doi: 10.1007/s10865-021-00223-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moulaert V.R., van Heugten C.M., Winkens B., et al. Early neurologically-focused follow-up after cardiac arrest improves quality of life at one year: A randomised controlled trial. Int J Cardiol. 2015;193:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Case R., Stub D., Mazzagatti E., et al. The second year of a second chance: Long-term psychosocial outcomes of cardiac arrest survivors and their family. Resuscitation. 2021;167:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobson M., Tattersfield A.E., Adler M.W., McNicol M.W. Attitudes and long-term adjustment of patients survivng cardiac arrest. Br Med J. 1971;3:207–212. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5768.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dichman C., Wagner M.K., Joshi V.L., Bernild C. Feeling responsible but unsupported: How relatives of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors experience the transition from hospital to daily life - A focus group study. Nurs Open. 2021;8:2520–2527. doi: 10.1002/nop2.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dougherty C.M., Pyper G.P., Benoliel J.Q. Domains of concern of intimate partners of sudden cardiac arrest survivors after ICD implantation. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;19:21–31. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200401000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallin E., Larsson I.M., Rubertsson S., Kristoferzon M.L. Relatives' experiences of everyday life six months after hypothermia treatment of a significant other's cardiac arrest. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:1639–1646. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsson I.M., Wallin E., Rubertsson S., Kristoferzon M.L. Relatives' experiences during the next of kin's hospital stay after surviving cardiac arrest and therapeutic hypothermia. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;12:353–359. doi: 10.1177/1474515112459618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawyer K.N., Brown F., Christensen R., Damino C., Newman M.M., Kurz M.C. Surviving Sudden Cardiac Arrest: A Pilot Qualitative Survey Study of Survivors. Ther Hypothermia Temp Manag. 2016;6:76–84. doi: 10.1089/ther.2015.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pußwald G., Fertl E., Faltl M., Auff E. Neurological rehabilitation of severely disabled cardiac arrest survivors. Part II. Life situation of patients and families after treatment. Resuscitation. 2000;47:241–248. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(00)00240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsen M.K., Mikkelsen R., Budin S.H., Lamberg D.N., Thrysoe L., Borregaard B. With Fearful Eyes: Exploring Relatives' Experiences With Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Qualitative Study. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2022 doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simons L.H., Cunningham S., Catanzaro M. Emotional responses and experiences of wives of men who survive a sudden cardiac death event. Cardiovasc Nurs. 1992;28:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenkilde S., Missel M., Wagner M.K., et al. Caught between competing emotions and tensions while adjusting to a new everyday life: a focus group study with family caregivers of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2022 doi: 10.1093/eurjcn/zvac056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mion M., Case R., Smith K., et al. Follow-up care after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A pilot study of survivors and families' experiences and recommendations. Resusc Plus. 2021;7 doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2021.100154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bohm M., Cronberg T., Arestedt K., et al. Caregiver burden and health-related quality of life amongst caregivers of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors. Resuscitation. 2021;167:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Wijnen H.G.F.M., Rasquin S.M.C., van Heugten C.M., Verbunt J.A., Moulaert V.R.M. The impact of cardiac arrest on the long-term wellbeing and caregiver burden of family caregivers: a prospective cohort study. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:1267–1275. doi: 10.1177/0269215516686155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beesems S.G., Wittebrood K.M., de Haan R.J., Koster R.W. Cognitive function and quality of life after successful resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2014;85:1269–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wachelder E.M., Moulaert V.R., van Heugten C., Verbunt J.A., Bekkers S.C., Wade D.T. Life after survival: long-term daily functioning and quality of life after an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2009;80:517–522. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van't Wout Hofland J., Moulaert V., van Heugten C., Verbunt J. Long-term quality of life of caregivers of cardiac arrest survivors and the impact of witnessing a cardiac event of a close relative. Resuscitation. 2018;128:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doolittle N.D., Sauvé M.J. Impact of aborted sudden cardiac death on survivors and their spouses: the phenomenon of different reference points. Am J Crit Care. 1995;4:389–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armand S., Wagner M.K., Ozenne B., et al. Acute Traumatic Stress Screening Can Identify Patients and Their Partners at Risk for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms After a Cardiac Arrest: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2021 doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Presciutti A., Newman M.M., Grigsby J., Vranceanu A.M., Shaffer J.A., Perman S.M. Associations between posttraumatic stress symptoms and quality of life in cardiac arrest survivors and informal caregivers: A pilot survey study. Resusc Plus. 2021;5 doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2021.100085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dougherty C.M. Longitudinal recovery following sudden cardiac arrest and internal cardioverter defibrillator implantation: survivors and their families. Am J Crit Care. 1994;3:145–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dougherty C.M., Thompson E.A. Intimate partner physical and mental health after sudden cardiac arrest and receipt of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Res Nurs Health. 2009;32:432–442. doi: 10.1002/nur.20330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dougherty C.M., Benoliel J.Q., Bellin C. Domains of nursing intervention after sudden cardiac arrest and automatic internal cardioverter defibrillator implantation. Heart Lung. 2000;29:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Israelsson J., Persson C., Bremer A., Strömberg A., Årestedt K. Dyadic effects of type D personality and perceived control on health-related quality of life in cardiac arrest survivors and their spouses using the actor-partner interdependence model. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2020;19:351–358. doi: 10.1177/1474515119890466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dougherty C.M. Psychological reactions and family adjustment in shock versus no shock groups after implantation of internal cardioverter defibrillator. Heart Lung. 1995;24:281–291. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(05)80071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brinkrolf P., Metelmann B., Metelmann C., et al. One out of three bystanders of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests shows signs of pathological psychological processing weeks after the incident - results from structured telephone interviews. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2021;29:131. doi: 10.1186/s13049-021-00945-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayer D.D., Rosenfeld A.G., Gilbert K. Lives forever changed: family bereavement experiences after sudden cardiac death. Appl Nurs Res. 2013;26:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carlsson N., Bremer A., Alvariza A., Arestedt K. Bereaved family members' lived experiences. Death Stud; Losing a close person following death by sudden cardiac arrest: 2020. Axelsson L; pp. 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jabre P., Belpomme V., Azoulay E., et al. Family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1008–1018. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jabre P., Tazarourte K., Azoulay E., et al. Offering the opportunity for family to be present during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: 1-year assessment. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:981–987. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3337-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Metzger K., Gamp M., Tondorf T., et al. Depression and anxiety in relatives of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients: Results of a prospective observational study. J Crit Care. 2019;51:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ingles J., Spinks C., Yeates L., McGeechan K., Kasparian N., Semsarian C. Posttraumatic stress and prolonged grief after the sudden cardiac death of a young relative. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:402–404. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeates L., Hunt L., Saleh M., Semsarian C., Ingles J. Poor psychological wellbeing particularly in mothers following sudden cardiac death in the young. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;12:484–491. doi: 10.1177/1474515113485510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Compton S., Levy P., Griffin M., Waselewsky D., Mango L., Zalenski R. Family-witnessed resuscitation: bereavement outcomes in an urban environment. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:715–721. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zimmerli M., Tisljar K., Balestra G.M., Langewitz W., Marsch S., Hunziker S. Prevalence and risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in relatives of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients. Resuscitation. 2014;85:801–808. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carlsson N., Arestedt K., Alvariza A., Axelsson L., Bremer A. Factors Associated With Symptoms of Prolonged Grief and Psychological Distress Among Bereaved Family Members of Persons Who Died From Sudden Cardiac Arrest. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2022 doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Compton S., Grace H., Madgy A., Swor R.A. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptomology associated with witnessing unsuccessful out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:226–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soleimanpour H., Tabrizi J.S., Jafari Rouhi A., et al. Psychological effects on patient's relatives regarding their presence during resuscitation. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2017;9:113–117. doi: 10.15171/jcvtr.2017.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prescuitti A. Gaps in the Provision of Cognitive and Psychological Resources in Cardiac Arrest Survivors with Good Neurologic Recovery. Ther Hypothermia Temp Manag. 2022;12:61–67. doi: 10.1089/ther.2021.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wisten A., Zingmark K. Supportive needs of parents confronted with sudden cardiac death–a qualitative study. Resuscitation. 2007;74:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davidson J.E., Jones C., Bienvenu O.J. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:618–624. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236ebf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perrin P.B., Heesacker M., Hinojosa M.S., Uthe C.E., Rittman M.R. Identifying at-risk, ethnically diverse stroke caregivers for counseling: a longitudinal study of mental health. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54:138–149. doi: 10.1037/a0015964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bannon S., Lester E.G., Gates M.V., et al. Recovering together: building resiliency in dyads of stroke patients and their caregivers at risk for chronic emotional distress; a feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2020;6:75. doi: 10.1186/s40814-020-00615-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DeForge C.E., George M., Baldwin M.R., et al. Do interventions improve symptoms among ICU surrogates facing end-of-life decisions? A prognostically-enriched systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(11):e779–e790. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mochari-Greenberger H., Mosca L. Caregiver burden and nonachievement of healthy lifestyle behaviors among family caregivers of cardiovascular disease patients. Am J Health Promot. 2012;27:84–89. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.110606-QUAN-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aggarwal B., Liao M., Christian A., Mosca L. Influence of caregiving on lifestyle and psychosocial risk factors among family members of patients hospitalized with cardiovascular disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:93–98. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0852-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agarwal S., Birk J.L., Abukhadra S.L., et al. Psychological Distress After Sudden Cardiac Arrest and Its Impact on Recovery. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2022;24:1351–1360. doi: 10.1007/s11886-022-01747-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong H.R. Intensive care medicine in 2050: precision medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1507–1509. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4727-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research: Enrichment Strategies for Clinical Trials to Support Approval of Human Drugs and Biological Products. FDA, 2019. Available from https://www.fda.gov/media/121320/download.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.