Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are chronic and progressive inflammatory joint diseases that affect a large population worldwide. Intra-articular administration of various therapeutics is applied to alleviate pain, prevent further progression, and promote cartilage regeneration and bone remodeling in both OA and RA. However, the effectiveness of intra-articular injection with traditional drugs is uncertain and controversial due to issues such as rapid drug clearance and the barrier afforded by the dense structure of cartilage. Nanoparticles can improve the efficacy of intra-articular injection by facilitating controlled drug release, prolonged retention time, and enhanced penetration into joint tissue. This review systematically summarizes nanoparticle-based therapies for OA and RA management. Firstly, we explore the interaction between nanoparticles and joints, including articular fluids and cells. This is followed by a comprehensive analysis of current nanoparticles designed for OA/RA, divided into two categories based on therapeutic mechanisms: direct therapeutic nanoparticles and nanoparticles-based drug delivery systems. We highlight nanoparticle design for tissue/cell targeting and controlled drug release before discussing challenges of nanoparticle-based therapies for efficient OA and RA treatment and their future clinical translation. We anticipate that rationally designed local injection of nanoparticles will be more effective, convenient, and safer than the current therapeutic approach.

Keywords: Nanoparticles, Intra-articular, Osteoarthritis, Rheumatoid arthritis, Controlled release, Drug delivery

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are two of the most prevalent joint disorders, affecting millions of people worldwide. In OA, the joint tissues undergo abnormal remodeling due to an excessive amount of inflammatory mediators within the joints, leading to joint degeneration. This condition affects an estimated 10–12% of the adult population worldwide [1,2]. On the other hand, RA is a chronic inflammatory and autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation and swelling of the synovium, abundant autoantibody production, and destruction of cartilage and bone. The incidence rate of RA is around 0.5–1% [3]. Both OA and RA may cause permanent joint damage, leading to chronic pain, decreased range of motion, and significantly reducing patients’ quality of life, which also result in socioeconomic burdens.

OA is a complex condition that involves multiple physiological processes affecting various parts of the joint, such as cartilage, synovium, subchondral bone, and meniscus [4]. Histologically, OA is characterized by cartilage degeneration, synovitis, meniscus loss, osteophyte formation, and subchondral bone sclerosis (Fig. 1) [5]. Proinflammatory and anabolic factors have been identified in OA, and an imbalance between these factors can contribute to joint inflammation, progressive destruction, and remodeling [6,7]. In contrast, the pathological process of RA primarily involves synovial hyperplasia and pannus formation, with other parts of the joint, including cartilage, subchondral bone, tendon, tendon sheaths, capsule, and ligaments, typically affected during the course of the disease (Fig. 1) [8]. In RA, various cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin 1 (IL-1), induce synovial hyperplasia and pain, followed by the invasion of degrading enzymes, mostly matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), into the cartilage and bone. TNF-α and IL-1 also contribute to bone destruction [9,10]. Intra-articular loose bodies may develop, which can further prolong joint damage and inflammation. Effective treatment is crucial to prevent disability, ankylosis, deformity, and severe secondary degenerative arthritis caused by RA [8].

Fig. 1.

Anatomy of joint under healthy, OA and RA condition.

The management of OA and RA aims to relieve pain, delay disease progression, promote cartilage regeneration and bone remodeling, and improve joint mobility and function. Contemporary clinical therapy procedures for these conditions are divided into three categories: non-pharmacologic management, pharmacologic management, and surgical management [11]. Non-pharmacologic management, such as exercise and physical therapy, can help relieve symptoms, but it only treats the symptoms instead of the root cause, and may even worsen the condition [12,13]. When OA or RA progresses to a later stage, surgical therapy, such as arthroscopic surgery or joint replacement surgery, may be considered. However, this approach is costly and carries significant risks, particularly for older patients or those with other major diseases, and has apparent limitations [14]. Current pharmacologic strategies for both OA and RA aim to relieve symptoms and improve the quality of life but are noncurative. Systematic administration of drugs, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory ones for OA and RA, can aid in pain relief, but the low local concentrations within the joints limit their efficacy. Low-dose methotrexate is commonly used for RA and can suppress immune and inflammatory reactions, but it may cause side effects such as hepatotoxicity, pulmonary damage, and myelosuppression [15]. In contrast, intra-articular injection offers several advantages for joint therapy, such as increased bioavailability, reduced systemic adverse reactions [16,17] and reduced cost [18,19]. Currently, intra-articular injection of corticosteroids for OA and RA and hyaluronate for OA are therapeutic alternatives for managing pain and symptoms in patients [16,20,21]. However, the efficacy of intra-articular injection of these agents remains controversial, partly because the drugs are rapidly cleared from the joints by capillary and lymphatic drainage [22]. Intra-articular injected steroids and albumin are cleared from joints within 1–4 h and 1–13 h, respectively [23,24]. The half-life of hyaluronic acid (HA) in the joint is only approximately 20 h [25]. Another reason is that the dense network of extracellular matrix in cartilage may prevent drug absorption and affect the diffusion of intra-articular administrated drugs into targeted sites and cells [24]. In addition to HA and corticosteroids, intra-articular injection of other biologic agents such as IL-1β antagonist (such as anakinra) [26], TNF-α inhibitors (such as etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab) [[27], [28], [29]], recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 7 [30], and recombinant human fibroblast growth factor 18 (sprifermin) [31] has also been reported. However, the results from clinical trials of these agents to date are not conclusive [16].

With the rapid development of nanotechnology, nanoparticle-based therapy offers some unique advantages. Nanoparticles can stabilize encapsulated drugs and achieve controllable drug release, which can lead to prolonged drug retention time and lower site toxicity [32]. Meanwhile, rationally designed nanoparticles could diffuse and penetrate the ECM and joint tissue to facilitate cartilage repair. Nanoparticle-based delivery systems can target specific sites actively or passively, enhancing therapeutic effects and lowering the side effects of the loaded drugs [33,34]. Responsive nanoparticles can release preloads based on pathological conditions in OA and RA, such as elevated reactive oxidative species (ROS), acidic pH, and overexpressed enzymes [35]. This targeted drug delivery system can enhance efficacy while reducing the risk of side effects.

This review provides state-of-the-art perspectives on the design of nanoparticles for intra-articular therapy in OA and RA. We begin by discussing the interaction of nanoparticles with the synovial fluid and cells of joints, and the pharmacokinetics of nanoparticles after intra-articular injection. We then examine the current nanoparticle-based therapies and categorize them into two groups based on their working mechanisms: direct therapeutic nanoparticles and nanoparticles as drug delivery systems (Fig. 2). For each category, we provide a detailed summary of the latest research progress and discuss the characteristics of the nanoparticles and their biological and therapeutic effects. Finally, our perspectives for the future clinical translation of intra-articular nanoparticles for OA and RA management including the challenges of nanoparticle design and clinical use are presented. This review aims to guide the development of next-generation intra-articular nanoparticles for the treatment of OA and RA.

Fig. 2.

Intra-articular injection of direct therapeutic and drug delivery nanoparticles for OA and RA. Possible interactions of nanoparticles with components in joints are illustrated. A, intra-articular injection of nanoparticles for OA and RA; B, nanoparticles interacting with extracellular matrix (ECM); C, nanoparticles interacting with synovial fluid; D, nanoparticles interacting with immune cells, chondrocytes or synoviocytes. Nanoparticles or their degradation products exit the joint via drainage through the lymphatics and capillaries underlying the synovium. NP, nanoparticle; MPS, mononuclear phagocyte system; HA, hyaluronic acid.

2. The interaction and pharmacokinetics of nanoparticles in joints

2.1. The interaction of nanoparticles with articular fluids

Synovial fluid is a lubricant, absorbs shock, and regulates the transportation of molecules within the joint [36]. Synovial fluid is the first substance with which any drug or nanoparticle injected into the joint interacts. The properties and functions of nanoparticles will be influenced by the complex biological composition of the fluid [37]. Some nanoparticle-based therapies target synovial fluid directly and modulate the physical, chemical or biological properties of the fluid.

Normal synovial fluid contains HA and glycoproteins in addition to the components filtrated from plasma. Albumin is the main protein in synovial fluid. Larger proteins such as macroglobulins and fibrinogen are in relatively small quantity. HA, synthesized by synthetic synoviocytes, gives synovial fluid its typical viscid character. The HAs form large proteoglycan complexes with a protein that is also synthesized by synthetic synoviocytes. Small amounts of cells such as synthetic synoviocytes, phagocytic synoviocytes, fibroblasts, chondrocytes and immune cells can be also found in synovial fluid [38,39]. For OA and RA, increased total cell amount in synovial fluid was observed. Especially for RA, dramatic increasement of cells including the blood-derived leukocytes can be found [40]. The presence of fibrinogen and altered proteoglycans are significant changes in synovial fluid observed in OA and RA [39,41].

Interaction with synovial fluid by nanoparticles upon intra-articular injection affects their hydrodynamic size, surface characteristics and colloidal stability [42]. For instance, the size and surface charge of poly (lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) nanoparticles changed after incubated with synovial fluid, affecting their cellular update performance [43]. These alterations are hypothesized due to the absorption of the synovial fluid components on the surface of the particles and the forming of protein corona. The protein corona can mask surface modifications or targeting ligands of nanoparticles, thereby affecting the interaction of the particles with cells or tissues [44].

2.2. The interaction of nanoparticles with cells within joints

Joints are enclosed spaces surrounded by synovium, cartilage, mucous bursa, ligament and fibrous capsule. Joint cells are primarily found in cartilage, synovium and subchondral bone. Fibroblast-like and macrophage-like synovial cells are the main cells in healthy synovium [45]. In OA and RA, the synovial intimal lining is infiltrated by inflammatory cells like B cells, T cells and macrophages [46]. This infiltration can lead to changes in catabolites and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, stimulating the change of catabolites and the generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Those changes altered the constitution of synovial fluid [47]. One the other hand, some cells like bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) can repair cartilage and subchondral bone. They have been shown to improve arthroscopic and histological changes in OA [48].

Within joints, injected nanoparticles can interact with cells such as immune cells, synoviocytes and chondrocytes, by either entering into those cells or releasing the loaded therapeutic drugs. The interactions between nanoparticles and cells are influenced by various characteristics of the nanoparticles, including their size, shape, charge, surface functionalization, and composition, as well as the biological and pathological microenvironment of the joints [49]. For size, within a size range of 50–1000 nm, smaller nanoparticles are reported to have higher cellular uptake efficacy compared to their large counterparts. Magnetic iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanoparticles with similar surface properties and well-defined sizes (70–350 nm) were synthesized for RA. Size-dependent internalization was observed when incubated with macrophages [50]. The shape also influences the nanoparticle's uptake efficiency. Rod-shaped, star-shaped, and spherical gold nanoparticles with a range from 40 to 110 nm were compared for their uptake efficiency by human MSCs, and it was determined that spherical nanoparticles obtained the highest uptake efficacy [51]. The surface properties and potential (charge) of nanoparticles play essential roles in the internalization process. A recent study demonstrated increased uptake of Kartogenin-loaded PLGA-polyethylene glycol (PEG) and PLGA-PEG-HA nanoparticles fabricated with different sizes, surface charge and hydrophobicity by MSCs compared to PLGA particles [52,53]. Modifying targeting ligands on the surface of nanoparticles can enhance cellular uptake. Dextran sulfate, for example, could actively target scavenger receptors on the surface of macrophages. Dextran sulfate-modified hydroxide nanocomposites have been shown to exhibit increased cellular uptake compared to non-targeting carriers for RA therapy [54].

The biological environment and severity of OA and RA likely influence the interaction between nanoparticles and cells. For example, catabolic enzymes in arthritis may change both the physiological status of cells and the properties of nanoparticles, affecting the interplay. Meanwhile, cellular uptake of nanoparticles may be distinct in normal and diseased cells, and the mechanisms still need further investigation.

2.3. The pharmacokinetics of nanoparticles in joints

2.3.1. The resident time of nanoparticles in joints

Lymphatic drainage rapidly clears intra-articular therapies from joints. The rate mainly depends on the size of the molecule [22]. For instance, the half-life of soluble steroids injected intra-articularly is only 1–4 h [23]. The half-period of albumin is 1–13 h in the joint, and hyaluronate takes approximately 20 h to clear from the joint [24,25]. Moreover, drug exit from inflamed joints is at a much faster rate. The half-period of hyaluronate in inflamed joints decreases from 20 h to 11–12 h [24]. The short resident time may hinder the therapeutic effects of OA and RA. Compared to free drugs, nanoparticles usually have a prolonged retention time in the joint due to their large size. The physical and chemical characteristics of nanoparticles such as size, shape, and surface properties determine their joint resident time.

Typically, nanoparticles with larger sizes have longer retention times, making them useful for enhancing the effectiveness of arthritis treatments. Andrés J. García et al. [55] prepared polymer nanoparticles with polyhydroxyethylmethacrylate backbone and a hydrophobic side chain of pyridine. The model protein bovine serum albumin was tethered to the nanoparticles to modulate the size, ranging from 500 to 900 nm. The researchers found that the half-life of 900 nm nanoparticles was 2.5 days, which is longer than the 1.9 days half-life of 500 nm nanoparticles. Importantly, they also demonstrated sustained retention of 900 nm particles in the joint space (∼30% at 14 days) compared to smaller particles. In addition to particle size, surface properties affect the retention time of nanoparticles. High positively charged (p/10.5) and small sized (7 nm diameter) avidin was able to penetrate the entire thickness of cartilage within 6 h. The half-period of avidin within the joint cavity was 29 h. The electrostatic interactions between anionic glycosaminoglycan content in cartilage ECM and cationic avidin were confirmed [56]. High uptake of a cationic PEGylated dendrimer into cartilage tissue without toxicity was demonstrated. When conjugating the dendrimer to insulin-like growth factor 1(IGF-1), the bioactivity was maintained. Compared to free IGF-1 with a half-life of 0.41 days, the residence time of the conjugate in the joint rise to 4.21 days [57]. Cationic polymeric nanoparticles could also be designed to ionically cross-link with hyaluronate in the synovial fluid. 70% of the particles remained in the joint space for one week after being injected into rats’ knees [58]. In addition, tissue-specific targeting ability could improve the dwelling time of nanoparticles in the joint space. The joint retention of nanoparticles could also be prolonged by targeting biomolecules such as collagen type II for immobilization [59]. By modifying the nanoparticles with a collagen II-binding peptide, a 7-day retention time in the joint can be achieved, whereas nanoparticles with a scrambled peptide only remain in the joint for about 6–8 h [60].

2.3.2. The degradation and clearance of nanoparticles from the joints

Chief degradation mechanisms of nanoparticles can be divided into chelation, hydrolysis, redox and enzymolysis [61]. Physicochemical properties, along with environmental factors affect the kinetics of loss of integrity and degradation of nanoparticles. In the arthritic environment, inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-1β, TNFα, and MMPs, are generated [62]. A series of pathways can be activated by these factors, which will contribute to the pathological progress of arthritis [63,64], and the inflammatory environment will affect the disintegration of the particles. To the best of our knowledge, there is a significant gap in understanding the degradation of nanoparticles that are intra-articularly injected for OA and RA that requires investigation.

The removal of nanoparticles and their encapsulated drugs from the articular cavity is aided by drainage through the lymphatics and capillaries that underlie the synovium surrounding the joint. Small particles tend to exit the joint through the capillaries, while the lymphatic pathway can eliminate nanoparticles and their degradation products, regardless of size [24,65]. Compositional or structural changes can influence the particles's behaviour. In addition, it is noted that synovial lymph flow is enhanced with systemic inflammation and autoimmune dysfunction in RA [66]. As a result, the clearance of large particles or molecules increases [67]. Further research is needed to determine how the pathogenesis of OA and RA impacts the elimination of injected biomaterials.

3. Direct therapeutic nanoparticles for OA and RA management

Current studies on nanoparticles for intra-articular therapy of OA/RA are focusing on particle types that can gradually release therapeutic agents, providing locally sustained drug action for effective arthritis treatment. Another type of nanoparticle is designed with a direct therapeutic effect on arthritis (Fig. 3). Although the nanoparticles do not carry drugs, their ingredients or designs can alleviate arthritis. These nanoparticles usually contain natural elements of joints, such as HA, chondroitin sulfate, collagen, or acellular ECM. The cell membrane-encapsulated nanoparticle can also be a direct therapeutic strategy for OA/RA. Direct therapeutic particles have attracted increasing consideration because of their low toxicity, biodegradable characteristics and good biocompatibility without an adverse immune response [68,69]. Nanoparticle systems for direct therapy of OA/RA are highlighted in the following review sections.

Fig. 3.

Intra-articular nanoparticles for OA and RA management. Based on their working mechanisms and functions, direct therapeutic nanoparticles and drug delivery systems are divided.

3.1. Hyaluronic acid nanoparticles

As a polymeric straight chain polysaccharide released predominately by synthetic synoviocytes [70], HA has remarkable biocompatibility, high moisture retention capacity, excellent viscoelasticity, and hygroscopic characteristics [71]. The skin [72], synovial fluid [73], vitreous body, and umbilical cord [74] contain the highest concentrations of HA. Additionally, HA is a crucial component of the ECM, which aids in cell division, migration, and morphogenesis.

When OA/RA develops, the molecular weight of HA in synovial fluid diminishes causing joint mechanical characteristics to deteriorate and joint dysfunction [75]. By injecting exogenous HA nanoparticles into the joint cavity, the concentration of HA in the joint can be maintained, thereby restoring the viscoelasticity of synovial fluid, assisting in joint lubrication, protecting the joint from vibration, and maintaining a stable joint environment [76]. Applying HA nanoparticles can help improve joint function and alleviate pain without significant toxicity, especially in the early and middle stages of OA [77]. Novel self-assembling HA-based gel core elastic nanovesicles (gel-core hyaluosomes) have been developed for the non-invasive transdermal distribution of HA into the joint [78]. Compared to conventional liposomes and plain gel, this nano-system exhibits higher ex vivo permeation of hyaluosomes, indicating enhanced self-penetration properties. A remarkable six-fold increase in transdermal permeation of HA to knee joints was also found in an in vivo study [78].

Matrix receptors integrin and CD44 have been reported to be responsible for the interactions between the ECM and chondrocytes, and for maintaining cartilage homeostasis. HA-based nanoparticles or HA-loaded nanomaterials can bind to CD44, a transmembrane glycoprotein, thus leading to the interaction. Empty HA-nanoparticles (without drug loading) have been shown to interfere with CD44 involved in OA pathogenesis. Kang et al. [79] successfully formulated empty HA-nanoparticles with no cytotoxicity, by self-assembling amphiphilic HA conjugates synthesized with low molecular weight HA and hydrophobic 5β-cholanic acid. The protective effect of nanoparticles against cartilage destruction mediated by CD44 has been demonstrated. In vitro studies have shown that HA nanoparticles can protect cartilage by blocking the CD44-NF-κB-catabolic gene axis. Furthermore, in a murine model of OA, these nanoparticles were found to significantly inhibit cartilage destruction compared to direct injection of high molecular weight HA [80].

In terms of chondrogenic differentiation, Chen et al. explored a new strategy of exposing chitosan/HA nanoparticles with osteoarthritic chondrocytes and MSCs derived from the human infrapatellar fat pad, demonstrating the nanoparticles’ ability to promote the production of type II collagen and aggrecan, and potential one-step cartilage repair as a therapeutic approach for knee OA [81]. Recently, Xie et al. developed composite nanofibers with HA as the main backbone and two different polymers as side chains that bound the cartilage surface to inhibit cartilage degradation. The synthesized brush-like lubricants not only promoted cartilage regeneration but also prevented the imbalance between cartilage catabolism and anabolism caused by lubrication dysfunction [82].

3.2. Chondroitin sulfate nanoparticles

Chondroitin sulfate is a sulfated glycosaminoglycan with a long, unbranched polysaccharide chain that consists of repeating disaccharide units of N-acetylgalactosamine and glucuronic acid. It plays an essential role in the extracellular matrix of various connective tissues, such as bone, cartilage, skin, ligaments, and tendons [83]. Studies have shown that chondroitin sulfate hinders the mRNA expression of MMPs in OA cartilage and stimulates proteoglycan synthesis by chondrocytes. In addition, it promotes cartilage defect repair by supplementing the cartilage matrix and reducing cartilage degeneration [84,85].

Several chondroitin sulfate nanoparticles with direct therapeutic properties have been investigated for arthritis treatment due to their advantages of outstanding biocompatibility, anti-apoptotic, pain-relieving and chondrogenic differentiation functions [86]. For example, a novel nano platinum decorated with chondroitin sulfate showed over 50% cell viability of OA chondrocytes despite elevated concentrations up to 100 ppm, indicating its potential application for OA treatment [87]. Improved nanoparticle biocompatibility by combining chondroitin sulfate and selenium via self-aggregation progress has been previously reported, where selenium-chondroitin sulfate nanoparticles were synthesized by ultrasonic and dialysis method to inhibit T-2 toxin induced chondrocytes apoptosis [88]. A more recent study evaluated the effects of chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine as structure modifiers to form a nanoemulsion, indicating safety for topical application and enhanced drug permeation through the skin; repair of articular cartilage and pain reduction were observed in some patients after nanoemulsion treatment [89]. In addition to these nanoparticles, Hong et al. [81] developed an artificial ECM nanoshell composed of fibronectin and chondroitin sulfate through layer-by-layer adsorption. The thickness of the nanoshell could be controlled by the number of layers. In this study, a total number of four layers promoted the highest expression of chondrogenic markers in MSCs, indicating a high efficiency of chondrogenic differentiation. Compared with the uncoated MSCs spheroids group, MSCs spheroids coated with the nanoshells exhibited superior chondrogenesis capacity in vivo [90].

3.3. Acellular ECM nanoparticles

Biomolecules secreted by residing cells and those constituting the ECM can facilitate the site-specific remodeling of tissues [91]. Production of naturally existing nanomaterials by decellularization has become alluring. The complex composition of decellularized ECM materials includes an ultrastructural microenvironment with imbedded inductive physicochemical and biological cues necessary for successful tissue regeneration [92]. When cellular components of cartilage ECM are removed, a framework of biomolecules is left behind that can stimulate chondrogenic development without provoking a negative immune response. All cellular residues can be removed through decellularization using chemicals (such as detergent-based and enzymatic treatments) and physical procedures (such as freeze-thaw) [93].

Few studies have used acellular ECM to synthesize nanoparticles for chondrogenic differentiation. Saeed Zahiri et al. developed acellular ECM nanoparticles with an average size of 61.5 ± 22.4 nm, which were shown to promote the chondrogenic development of human primary chondrocytes in micromass spheroids by retaining natural ECM signals [94]. After 21 days of growth in media containing acellular ECM nanoparticles, several chondrogenic markers, including SOX9 and COL2, were expressed similarly to those of cells cultured in a commercial differentiation medium. These findings suggest that acellular ECM nanoparticles could be a useful supplement in culture media and injectable biomaterials, particularly for cell-based therapies for cartilage tissue regeneration.

3.4. Cell membrane-coated nanoparticles

Cell membrane-coated nanoparticles have been developed into a potential therapeutic platform [95]. These nanoparticles are created by fusing synthetic cores with natural cell membranes that allow them to retain the antigenic profile of the donor cells. These nanoparticles function as decoys that can absorb and eliminate diverse and intricate pathogenic chemicals [96]. Cell-mimicking nanoparticles are an efficient anti-inflammatory strategy to overcome the challenges associated with current OA/RA therapy.

A nanoparticle-based anti-inflammatory approach was prepared through fusing neutrophil membrane onto polymeric cores and resulted in the broad-spectrum therapeutic efficacy of RA [97] (Fig. 4). These nanoparticles were able to target deeply inside the cartilage matrix, neutralize proinflammatory cytokines, decrease synovial inflammation, and offer potent chondroprotection against joint injury. The neutrophil membrane-coated nanoparticles exhibited notable therapeutic efficacy in rodent models of arthritis by reducing joint destruction and alleviating disease severity [97]. For RA therapy, a macrophage-derived microvesicles-coated nanoparticle was also created by coating PLGA with macrophage-derived microvesicles [98]. By weakening the bond between the macrophages' cytoskeleton and membrane, cytochalasin B was utilized to promote microvesicle secretion. Since the bioactivity of macrophage-derived microvesicles was similar to that of RA-targeting macrophages, the nanoparticles showed enhanced inflammation-mediated targeting capacity in vitro as well as in vivo. In comparison to the red blood cell membrane-coated nanoparticles, macrophage-derived microvesicles-coated nanoparticles had a substantially greater in vitro binding capacity to inflamed human umbilical vein endothelial cells. The nanoparticles also demonstrated a more improved targeting effect in vivo in a collagen-induced arthritis animal model when compared to bare nanoparticles and red blood cell membrane-coated nanoparticles. In this research, Mac-1 and CD44 helped the macrophage-derived microvesicles-coated nanoparticles achieve their exceptional targeting impact [98].

Fig. 4.

Nanoparticles with neutrophil membrane coatings minimize arthritic joint degeneration and synovial inflammation in RA. A, Neutrophil-nanoparticles were shown schematically; B, transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of Neutrophil-nanoparticles (uranyl acetate were used to stain samples, Scale bar, 100 nm); C, after being incubated with neutrophil-nanoparticles or red blood cell-nanoparticles, fluorescent pictures of chondrocytes and human umbilical vein endothelial cells were presented. Blue and red stand for nuclei and nanoparticles, respectively. Cells were stimulated with TNF-α previously. Scale bar, 50 μm; D-E, Neutrophil-nanoparticles affected chondrocyte activation (D), apoptosis (D), and release of MMP-3 (E); F, H&E and safranin-O staining images of mice's knee sections treated with neutrophil-nanoparticles, phosphate buffered saline (PBS), anti-IL-1β antibody, or anti- TNF-α antibody. Scale bars, 100 μm; G, Safranin-O stained knee slices were employed to calculate the amount of cartilage present. Scale bars, 100 μm. Reproduced from Ref. [97] with permission from Elsevier.

As M2 macrophages exhibit anti-inflammatory properties to alleviate OA and stimulate cartilage regeneration repair, Dai et al. proposed and fabricated artificial M2 macrophages with the yolk-shell structure for the treatment of OA [99]. The “shell” referred to macrophage membrane and the “yolk” referred to inflammation-responsive nanogel. Gelatin and chondroitin sulfate were physically combined to generate the nanogel, which obtained burst release properties to decrease inflammation during acute phases of OA and sustained release properties to repair cartilage during low inflammatory conditions [99]. Furthermore, artificial M2 macrophages displayed targeting and sustained residence in the inflammatory area and prevented immunological activation of macrophages induced by chondroitin sulfate. This nanoparticle was anticipated to end OA's self-reinforcing cycle [99]. As a novel method for cartilage regeneration, nanoparticles generated from mesenchymal stem cells have also been produced. Machluf et al. established a brand-new class of nanoparticles called nano-ghosts that were based on the cytoplasmic membrane of MSCs [100]. They demonstrated nano-ghosts’ ability to target cartilage tissues. These particles effectively reduced inflammation by modulating pro-inflammatory mechanisms in vitro and preventing bone and cartilage breakdown in vivo. Through this work, nano-ghosts were confirmed as possible future therapeutics for OA.

3.5. Other direct therapeutic nanoparticles

In addition to these nanoparticles with natural elements as direct therapeutics, several inorganic nanoparticles have also demonstrated direct anti-inflammatory properties for treating OA and RA.

Gold nanoparticles were developed as a treatment alternative for arthritis. Previous studies hypothesized that gold's anti-inflammatory qualities work in a variety of ways, including inhibiting the release of lysosomal enzymes by phagocytic cells, modifying prostaglandins, reducing the proliferation of synovial cells, and increasing the production of collagen [101]. Manal A. Abdel-Aziz et al. [102] evaluated the safety of gold nanoparticles for OA therapy. The biosynthesized gold nanoparticles had a zeta potential of 33 mV and were virtually spherical, measuring an average of 20 nm. After being applied in vivo, gold nanoparticles were proved to be more effective than Diacerein for alleviating OA in rats [102]. Manganese dioxide nanoparticles were also developed for protecting chondrocytes in osteoarthritic cartilage [103]. Manganese dioxide catalyzes the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), one of the principal ROS generated by chondrocytes [104]. The small size (less than 20 nm) and cationic property of the manganese dioxide nanoparticles facilitated their uptake into cartilage. The particles have shown the ability to penetrate through the depth of cartilage explants and demonstrate chondroprotection of cytokine-challenged cartilage explants. After being injected intra-articularly, the retention and biodistribution properties confirmed the nanoparticles as a promising approach for protecting chondrocytes in OA [103]. Large pore mesoporous silica nanoparticles loaded with ceria nanoparticles and coated with asymmetric manganese dioxide are also promising for intra-articular RA therapy. These nanomotors have been shown to decrease various pro-inflammatory cytokines and reduce joint degradation in the RA microenvironment by consuming overexpressed H2O2, generating O2, and scavenging inflammation [105]. Additionally, cerium oxide nanoparticles are also being investigated for their potential in RA management. Lin et al. [106] synthesized 120 nm-sized cerium (IV) oxide (CeO2) nanoparticles using the hydrothermal method and demonstrated their ability to protect chondrocytes from damage caused by ROS. Similarly, Ponnurangam et al. [107] showed that commercial CeO2 nanoparticles have an anti-inflammatory effect on IL-1α-induced chondrocytes. Additionally, Han et al. successfully improved the retention effectiveness for cartilage with super-lubrication by immobilizing nanofat in aldehyde-modified PLGA porous microspheres [108].

4. Nanoparticles as drug delivery systems for intra-articular therapies

Nano-scale drug delivery systems have also been developed for intra-articular therapy with advantages over traditional drug treatments. To effectively treat arthritis, the system for delivering drugs must be able to pass biological barriers inside the joint, release at the right time and place, and deliver effective agents at the required dose. The intra-articular nano-drug delivery system offers such a possibility, ensuring precise and sensitive drug delivery. In the following section, traditionally designed drug-delivery nanoparticles (such as liposomes, polymers, mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) et al.), functionally targeting nanoparticles, and stimuli-responsive nanoparticles will be reviewed, providing further insight into the therapy of OA and RA.

4.1. Traditionally designed nanoparticles as drug delivery systems for joint therapy

Traditionally designed nanoparticles are the main carriers of anti-inflammatory drugs or genes. After intra-articular injection, the cargo loaded can be released into the joint cavity and then act as a therapy. Organic polymer nanoparticles, such as liposomes, polymers, and inorganic nanomaterials such as MSNs can be used as these types of carriers.

4.1.1. Lipid NPs/Liposomes

As spherical nanostructures with double-layer membranes, liposomes containing a water phase as the inner cavity and natural phospholipids as the exterior layer [109]. Basically, phospholipids act as effective biological lubricants for reducing friction and keeping the active motility of synovial joints. Zhao et al. integrated the lubrication ability of liposomes and anti-inflammatory properties of d-glucosamine sulfate. The liposomes could release d-glucosamine sulfate continuously and offer effective lubrication, as well as supply anti-inflammatory effects and protection of chondrocytes in vitro [110]. Additionally, hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds can be combined in liposomes, with the possibility of surface modification enabling targeted selection and prolonged retention time in the joints' environment. Rimona Margalit et al. [111] demonstrated alleviated knee joint inflammation in OA rats over 17 days mediated by local injections of liposomal dexamethasone-diclofenac formulation carrying hyaluronan or collagen as the surface-anchored ligands [111].

Liposomes can potentially reduce the adverse events of anti-inflammatory agents. The hybrid formulation of celecoxib-loaded liposomes encapsulated in HA gel developed by Dong et al. [112], for example, showed high encapsulation efficiency (>99%). By reducing the dose and exposure time, the intra-articular delivery of the formulation may lower the risk of cardiovascular events.

4.1.2. Synthetic polymers based NPs

Biodegradable polymers such as poly lactic acid (PLA) and its derivative PLGA can be employed as carriers for intra-articular therapy due to their good mechanical properties, high biocompatibility and chemical versatility, controlled loading capacity and sustained drug release [[113], [114], [115], [116]]. Downregulation of TNF-α via PLGA nanoparticle-loaded TNF-α siRNA has been demonstrated in inflammatory macrophages in vitro and associated with a reduction in disease activity of RA in vivo in a murine arthritis model [115]. Introducing hydrophilic PEG to modify the surface of PLA/PLGA to create amphiphilic block copolymers could help to obtain high drug loading and effective delivery, preventing surface aggregation, phagocytosis, and prolonged circulation time [117]. Another promising approach for treating RA could be the use of mesoporous polydopamine nanoparticles coated with spherical polyethyleneimine and loaded with STING antagonist C-176. The STING pathway is stimulated by ds-DNA accumulation, a feature of RA. These nanoparticles can inhibit the STING pathway and inflammation in macrophages, thereby alleviating ds-DNA-induced and collagen-induced arthritis when injected into the joint cavity of mice [118].

While biodegradable synthetic polymers have been widely utilized for drug delivery, there are limited direct intra-articular applications for OA or RA. One potential disadvantage is that the acidic degrading products of these polymers may worsen cartilage inflammation and matrix degradation [115,116,119,120].

4.1.3. Natural polymers and their derivates based NPs

Natural polymers such as chitosan, alginate, and cellulose derivatives show therapeutic potential for intra-articular drug delivery [121,122]. Chitosan has strong biocompatibility for preserving the cartilage formation phenotype and proliferative activity, similar to glycosaminoglycans in natural cartilage, as well as the adjustable degradability determined by deacetylation degree [123,124]. For drug and gene delivery, chitosan nanoparticles can not only increase duration in synovial fluid but also reduce the concentration of therapeutic agents in plasma, thus effectively alleviating OA. Zhao et al. produced chitosan-based nanoparticles for sustained release of berberine chloride, a kind of isoquinoline alkaloid with anti-OA properties [125]. In comparison to free berberine chloride solution, the quantity of the drug in rat blood was reduced and the retention time in the synovial fluid increased after intra-articular injection of berberine chloride-loaded nanoparticles. The carriers showed high anti-apoptosis activity in OA therapy. Chitosan nanoparticles also exhibit rapid cellular uptake by macrophages in RA [126]. However, limited water solubility and charge reduction under physiological pH, as well as poor transfection efficiency and targeting, are limitations to be taken into account [127].

4.1.4. Inorganic nanoparticles

Inorganic nanoparticles such as MSNs have been utilized for intra-articular drug and gene delivery for the treatment of arthritis, with the benefits of enormous surface area, large pore volume, capacity to modify the morphology and pore structure, controlled surface functioning, and advanced biocompatibility [128,129]. Target drugs can be loaded at high capacities and released constantly when MSNs are applied in the therapy of arthritis [130,131]. Researchers have developed MSNs with a core-cone structure and surface-functionalized with polyethyleneimine and delivered biocompatible hyaluronan synthase type 2 into synovial cells in the OA joint. The high molecular weight of endogenous hyaluronic acid could be synthesized by this nanoparticle delivery system. This method encouraged endogenous HA synthesis and prevented synovial inflammation for more than three weeks with one shot [131] (Fig. 5). After surface-decoration with phospholipid [132] or manganese ferrite/ceria [133], the lubrication or ROS scavenging function of MSNs would increase, making the drug-delivery nanoparticles more effective for arthritis therapy.

Fig. 5.

Hyaluronan synthase 2 is being delivered via MSNs with a core-cone structure and surface-functionalized with polyethylenimine to improve native hyaluronan generation. A, Nanoparticles mediated Hyaluronan synthase 2 delivery to synoviocytes; B, MSNs with a core-cone structure and surface-functionalized with polyethylenimine examination by TEM (a), scanning electron microscope (SEM) (b), and electron tomography (ET) (c); C, Representative immunoblots and D, quantitative information on the levels of Hyaluronan synthase 2, CD44, and high mobility group box 1 protein expression in synoviocytes; E, MicroCT scans of the temporomandibular joint condyles with sagittal section views at 2 and 12 weeks following monoiodoacetate injection. Reproduced from Ref. [131] with permission from John Wiley and Sons.

Inorganic nanoparticles offer several advantages over their organic counterparts. They tend to be more rigid and stable, making them less susceptible to degradation and other environmental factors. This property can be particularly useful in the development of drug delivery systems for large biomolecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids. Additionally, inorganic nanoparticles can achieve high drug loading capacity, allowing for the delivery of higher doses of therapeutic agents with greater efficiency [134,135]. However, one concern with inorganic nanoparticles is their potential toxicity and lack of biodegradability. If they persist in the body for too long, they can lead to chronic inflammation and other adverse effects. Additionally, the clearance of inorganic nanoparticles from the body can be a concern. It is important to carefully consider the biocompatibility of any inorganic nanoparticle system before they are used in OA/RA treatment.

4.2. Nanoparticles designed for targeted joint therapy delivery

Nanoparticles can effectively improve the efficiency of loaded drugs by targeting cells or specific components within the joint tissue. Approaches can be categorized into two types:active targeting and passive targeting. Active targeting is usually achieved by connecting ligands to nanocarriers for receptors increased on target cells or components. The ligand-receptor interaction elicits effective cellular uptake of particles via endocytosis [136]. Passive targeting refers to enhanced interaction between nanoparticles and cells or tissues with the effect of the nanoparticle's inherent physical and chemical characteristics, including size, charge, hydrophilicity, etc. Potential designs for active and passive targeting nanoparticles applied in intra-articular drug delivery systems will be discussed.

4.2.1. Active targeting strategies

4.2.1.1. Nanoparticles decorated with penetrating peptides

Due to the meshwork of collagen and aggrecan proteoglycans, joint tissues, such as cartilage, ligaments, meniscus and tendons, are avascular and dense. These tissue barriers often prevent the perfusion of exogenous substances and block penetration of most active molecules of therapeutic value. Therefore, it is particularly important to develop penetrating and binding materials for therapeutic agent delivery to target related sites in OA and RA. As short peptides applied in this case, penetrating peptides obtain a valid capacity for transduction and are able to be utilized for delivering active cargoes into the targeted components or cells.

For instance, DSPE-PEG-TAT modified nanoparticles enhance chondrocyte association. Targeted micelles and liposomes bound chondrocytes about four times higher than untargeted carriers [137]. Another chondrocyte penetrating peptide, p5RHH peptide, can effectively penetrate human cartilage (>700 μm) to deliver its siRNA cargo aimed at reducing chondrocyte apoptosis and mitigating cartilage degeneration [138]. Another cell-penetrating anti-inflammatory peptide can inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α when released from polymer nanoparticles (Table 1). This system was shown to be efficient in selectively targeting macrophages and damaged tissue in bovine knee cartilage explants, and potentially an effective tool to treat OA [139] (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Direct therapeutic nanoparticles for OA and RA management.

| Nanoparticle type | Nanoparticle System | Control | Nanoparticle Size | TestModel | OA/RA | Major findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA-based nanoparticles | Self-assembled low molecular weight HA and hydrophobic 5β-cholanic acid nanoparticles | High molecular weight HA nanoparticles | 221 ± 1 nm | In vivo mouse model treated with destabilization of the medial meniscus surgery | OA | Achieved a chondroprotective effect by blocking the CD44-NF-κB-catabolic gene axis; Effectively protected the cartilage destruction induced by destabilization of the medial meniscus compared to high molecular weight HA nanoparticles |

[80] |

| Chitosan/HA nanoparticles | The monocultures of articular chondrocytes (ACs) and infrapatellar fat pad (IPFP)-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) | 74.6 ± 7.6 nm | In vitro pellet coculture of human IPFP MSCs and ACs | OA | Exhibited a higher expression of chondrogenic markers, major ECM proteins; Improved the chondrogenic differentiation of ACs and IPFP MSCs |

[203] | |

| Self-assembled gel-core hyaluosomes | HA nanoparticles only, liposomes, liposomal gel, liquefied hyaluosomes | 226–233 nm | Applied to rat's knee joint skin topically to observe the transdermal route of the administration | OA | Enhanced penetration degree and dermal localization of HA; Increased six folds of HA amount than HA aqueous gel; Exhibited high stability even after 6 months storage at 4 °C |

[78] | |

| Chondroitin sulfate-based nanoparticles | Self-aggregated selenium-chondroitin sulfate nanoparticles | untreated cells, chondroitin sulfate solution and T-2 toxin, T-2 toxin alone | 30–200 nm | In vitro cell culture of cartilage chondrocytes from Kashin–Beck disease patients | OA | Showed lower cytotoxicity of chondrocytes than sodium selenite; Reduced the impact of T-2 toxin on inducing apoptosis in chondrocytes for Kashin-Beck disease patients |

[88] |

| Platinum nanoparticles coated with chondroitin sulfate | untreated cells | 3–5 nm for Pt nanoparticles | In vitro cell culture of OA chondrocytes | OA | Exhibited a concentration dependent cytotoxicity towards OA chondrocytes and great biocompatibility | [87] | |

| Fibronectin and chondroitin sulfate-based nanoshell | Collagen-based nanoshells (heparin, tannic acid and chondroitin sulfate) and fibronectin-based nanoshells (heparin, chondroitin sulfate and collagen) | ∼150 nm in thickness | Nanoshell-coated MSCs spheres transplanted into the subcapsular layer of the kidney in the nude mouse mineralization model | OA and RA | Promoted chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs; Increased the formation of cartilage-like tissue in vivo |

[90] | |

| Collagen and Acellular ECM derived nanoparticles | Decellularized extracellular matrix nanoparticles | Devitalized cartilage powder | 61.56 ± 22.4 nm | In vitro cell culture of human primary chondrocytes | OA and RA | Exhibited similar expression level of SOX9 and COL2 to commercial differentiation medium; Promoted chondrogenic differentiation of human primary chondrocytes in micromass spheroids |

[94] |

| Cell membrane-coated nanoparticles | Neutrophil membrane-coated PLGA nanoparticles | Red blood cell membrane-coated PLGA nanoparticles | N/A | In vivo mouse model of collagen-induced arthritis and human transgenic mouse model of inflammatory arthritis | RA | Showed deeper penetration into the cartilage matrix of mouse femoral head explants, better synovial inflammation suppression ability and higher chondrogenesis than control group; Ameliorated joint damage and suppressed overall arthritis severity; Provided a function-driven, broad-spectrum and disease-relevant blockade that dampened the inflammation cascade |

[97] |

| Macrophage-derived microvesicle- coated PLGA nanoparticles | Bare PLGA nanoparticles and red blood cell membrane-coated nanoparticles | 130 ± 14 nm | Collagen-induced arthritis mouse model | RA | Exhibited significantly stronger in vitro binding ability to inflamed human umbilical vein endothelial cells; Significantly enhanced targeting effect towards inflammatory synovium in vivo; Suppressed the progression of RA in mice model with tacrolimus loaded |

[98] | |

| Artificial M2 macrophage membrance coated chondroitin sulfate-loaded gelatin/chondroitin sulfate-crosslinked nanogel nanoparticles | Chondroitin sulfate, gelatin nanoparticles, gelatin/chondroitin sulfate-crosslinked nanogel (GC), chondroitin sulfate-loaded GC (ChS@GC), erythrocyte membrane-cloaked ChS@GC | 608.57 ± 11.37 nm | Papain solution injection into knees of mice | OA | Showed higher adhesion ability and accumulation rate to inflamed cartilage in vivo; Achieved controllable release of chondroitin sulfate dependent on the inflammation of OA; Decreased joint surface erosion, chondrocyte apoptosis and loss of glycosaminoglycan content; Down-regulated the secretion level of the inflammatory factors (IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-17); Demonstrated the ability to target and remain in the inflamed region for an extended period of time, and prevented immune stimulation of macrophages |

[99] | |

| MSCs' cytoplasmic-membrane-based nanoparticles | untreated group | ∼200 nm | Mice with surgical destabilization of the knee medial meniscus | OA | Demonstrated the ability to target cartilage tissues in vitro and in vivo; Showed less osteophyte formations and slower cartilage degeneration compared with the OA group without treatment |

[100] | |

| Other direct therapeutic nanoparticles | Gold nanoparticles | Untreated control rats, normal rats treated with diacerein, gold nanoparticles, and gold nanoparticles plus diacerein, OA rats, OA rats treated with diacerein or gold nanoparticles and gold nanoparticles plus diacerein | ∼20 nm | In vivo rat model of monosodium iodoacetate-induced OA | OA | Showed more effective treatment than diacerein; Increased formation of joint cartilage with the combined treatment with gold nanoparticles and diacerein |

[97] |

| PEG modified manganese dioxide nanoparticles | Saline injected group | 15 ± 4.3 nm | In vivo rat OA model | OA | Reduced the loss of glycosaminoglycans and release of nitric oxide; Demonstrated chondroprotection of cytokine-challenged cartilage explants; Reduced oxidative stress in cartilage; Accumulated at the chondral surfaces and co-localized with the lacunae od chondrocytes |

[98] | |

| Cerium oxide nanoparticles | Untreated cells, treated with H2O2, treated with H2O2 and HA, treated with H2O2, HA and cerium oxide nanoparticles | 131.1 ± 0.7 nm | In vitro cell culture of chondrocytes | OA | Decreased chondrocytes apoptosis induced by H2O2; Enhanced the scavenger effect on the H2O2 oxidative stree of chondrocytes with the presence of HA; Improved cartilage degeneration |

[99] | |

| Nanofat functionalized microfluidic microspheres with PLGA modification | Sham operation group, PBS, PLGA modified microspheres only and nanofat only | N/A | In vivo rat OA model of surgical destabilization of the knee medial meniscus | OA | Improved joint lubrication, targeted cartilage surface adhesion and loading efficiency; Increased the expression of cartilage anabolic substances; Downregulated cartilage catabolic enzymes, and inflammation-related and pain-related genes; Suppressed the progression of OA in vivo by improving lubrication of the joint cavity and behavioral performance, and reducing the production of osteophytes |

[108] |

Table 2.

Nanoparticles design on targeting delivery for joint therapy.

| Nanoparticle | Targeting modality | Loaded drugs | Particle-size | Control | Test Model |

OA/RA | Major findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-penetrating peptide-modified micelle and liposome | Active (penetrating peptide TAT, sequence: YGRKKRRQRRR-C) |

N/A | 106 nm (modified micelle); 397 nm (modified micelle liposome) |

Unmodified micelles and liposomes | Ex vivo bovine explants | OA | Significantly increased chondrocyte-associated fluorescence; Enhanced micelle diffusion in articular cartilage of explants with IL-1 and trypsin treatments |

[137] |

| Self-assembling p5RHH-siRNA peptidic nanoparticles | Active (penetrating peptide p5RHH, sequence: VLTTGLPALISWIRRRHRRHC) | NF-κB p65 siRNA | 55 ± 18 nm | Scram siRNA nanoparticles | Ex vivo IL-1β treated human articular cartilage explants | OA | Demonstrated the ability to penetrate into human cartilage; Suppressed IL-1β induced p65 activation up to 3 weeks, indicating attenuation of chondrocyte apoptosis and maintenance of cartilage homeostasis |

[138] |

| KAFAK-loaded poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) nanoparticles | Active (penetrating peptide KAFAK, sequence: KAFAKLAARLYRKALARQLGVAA) | KAFAK peptide; loading capacity 0.605 ± 0.062 mg/mg | 129–408 nm | N/A | In vitro inflammatory macrophage; Ex vivo aggrecan-depleted bovine knee cartilage explants | OA | Selectively and effectively reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in macrophages and bulk cartilage plugs; Displayed a limited tendency to diffuse into healthy cartilage. |

[139] |

| Peptide modified MMP-13 ferritin nanocages | Active (penetrating peptide, WRYGRL) | Hydroxychloroquine Loading capacity: 0.49 mg/mg |

∼22 nm | Ferritin nanocages, peptide modified ferritin nanocages | In vivo mouse model of papain solution injection into knees | OA | Showed dual-stimuli activation and cartilage targeting for on-demand prognosis and intra-articular release of hydroxychloroquine; Achieved MMP-13 responsive fluorescence signal recovery of a NIR dye for fluorescence imaging and diagnosis of OA; Realized the pH-responsive release of anti-inflammatory drug for OA treatment |

[141] |

| Peptide modified poly (propylene sulphide) nanoparticles | Active (penetrating peptide, sequence: WYRGRL) | N/A | 38 nm (polydispersiy index 0.221); 96 nm (polydispersiy index 0.261) |

Poly (propylene sulphide) nanoparticles and with scrambled peptide (YRLGRW) nanoparticles | In vivo mouse model of antero-lateral injection into healthy knee joints | OA | Provided an intra-tissue release of a therapeutic agent; Enhanced targeted delivery into extracellular space of articular cartilage and entered chondrocytes |

[59] |

| Peptide modified PLGA nanoparticles | Active (penetrating peptide, sequence: WYRGRLK) | N/A | 180.2 ± 8.0 nm | Passive targeting cationic nanoparticles, untargeted neutrally-charged nanoparticles | In vivo model of collagenase-induced OA rat knees | OA | Improved nanoparticles retention in both healthy and OA-mimicked cartilage matrix; Showed proportionally more association with femoral cartilage in OA knees compared to healthy knees |

[143] |

| Peptide modified lipid-polymer core shell nanoparticles | Active (penetrating peptide, sequence: WYRGRLC) | MK-8722, an activator of 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase Loading capacity: 0.058 mg/mg |

25 nm | Nontargeted lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles | In vivo model of collagenase-induced OA rat knees | OA | Increased average fluorescence intensity and depth within tissues; Encapsulated MK-8722 at high capacity and released them in a sustained and controllable manner; Reduced cartilage damage and alleviated disease severity |

[144] |

| Radiolabeled HA-PLGA nanoparticles | Active (binding to macrophage CD44 receptor) |

Methotrexate; Loading capacity: 0.06 mg/mg |

167.6 ± 57.4 nm |

177LuCl3,177Lu-DOTA-HA-PLGA,177Lu-DOTA-PLGA (MTX), MTX, HA-PLGA, PLGA (MTX) and HA-PLGA (MTX) |

In vitro tests with macrophages | RA | Enhanced cellular uptake of nanoparticles and the cytotoxic effect mediated by HA binding and consequent internalization . |

[145] |

| HA-coated bovine serum albumin nanoparticles | Active (binding to chondrocyte CD44 receptor) | Brucine; Loading capacity: 0.042 mg/mg |

108.1 ± 5.9 nm | Bovine serum albumin nanoparticles | In vivo rat model of intra-articular injection into healthy knee joints | OA | Exhibited biocompatibility and efficient targeting; Improved cellular uptake with HA coating; Showed slower elimination from the articular cavity; |

[147] |

| HA-coated nanostructured lipid carriers | Active (binding to chondrocyte CD44 receptor) | Isoxazole derivative lefunomide; Loading capacity: 0.102–0.123 mg/mg |

153.8 nm | Uncoated nanostructured lipid carriers, CS-coated lipid carriers | In vivo model of complete Freund's adjuvant-induced arthritic rat knees | RA | Showed convenient gelation time, easy injectability, formulation-dependent mechanical strength and extended leflunomide releasing time; Exhibited superior efficacy in joint healing of induced-arthritic rat model |

[148] |

| Dextran sulfate-triamcinolone acetonide conjugate nanoparticles | Active (binding to scavenger receptor class A of macrophage) | Dextran sulfate and triamcinolone acetonide | ∼70 nm | Free dextran sulfate and triamcinolone acetonide in vitro and without induction of OA in vivo | In vivo model of monosodium iodoacetate -induced OA rat knees | OA | Demonstrated targeting specificity to scavenger receptor class A on activated macrophages; Effectively reduced the viability of activated macrophages and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines; Alleviated the structural damage to the joint cartilage; Reduced the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-) in the cartilage tissue |

[149] |

| Monoclonal antibody functionalized polymeric siRNA nanoparticle complexes | Active: Col2 antibody (targeting type II collagen in cartilage) |

siRNA that suppresses MMP-13 expression | ∼100 nm | polymeric siRNA nanoparticles with no antibody conjugation and functionalized with an off-target antibody | In vivo mouse model of acute post-trauma OA of noninvasive repetitive joint loading | OA | Enhanced the binding of polymeric siRNA nanoparticle complexes to exposed Col2 in damaged cartilage compared to undamaged cartilage, with the conjugation of monoclonal antibody; Reduced the expression of MMP-13 and protected cartilage integrity and overall joint structure in vivo |

[152] |

| Monoclonal anti-type II collagen antibody-coated nanoscaled liposomes | Active: antibodies (targeting the type II collagen in cartilage matrix) | N/A | ∼100 nm | IgG 2 A antibod-coated nanosomes | In vivo OA mouse model induced by destabilization of the medial meniscus | OA | Enhanced binding specificity to the cartilage tissue according to the severity of damage | [153] |

| Chitosan-HA nanoparticles with anti-IL-6 antibody | Active: anti-IL-6 antibody (binding IL-6) | N/A | ∼130 nm | Soluble anti-IL-6 antibody | In vitro incubation with human articular chondrocytes and macrophages | OA and RA | Demonstrated immobilization capacity and superior cytocompatibility with human articular chondrocytes and macrophages; Exhibited a prolonged action and stronger efficacy than the soluble antibody |

[154] |

| ZIF-8 nanoparticles modified with anti-CD16/32 antibody | Active: anti-CD16/32 antibody (targeting M1 macrophages) |

S-methylisothiourea hemisulfate salt and catalase; Loading capacity: 1.38 and 0.44 mg/mg respectively |

∼160 nm | Free catalase protein, physical mixture of catalase and ZIF-8 nanoparticles | In vivo OA mouse model induced by anterior cruciate ligament transection | OA | Showed the ability to target synovial M1 macrophages with increased retention time in OA joints; Allowed for pH-responsive release; Promoted the shift of macrophages from M1 to M2, decreasing the secretion of inflammatory cytokines Attenuated cartilage degeneration in vivo |

[155] |

| Thermosensitive hollow PEGylated poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) nanoparticles | Passive (size effect) | Anti-inflammatory peptide, KAFAK; Loading capacity: 0.498 ± 0.087 mg/mg |

293 ± 1.4 nm | Non-PEGylated poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) nanoparticles, solid poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) nanoparticle counterparts (NGPEGMBA and NGMBA) | Ex vivo OA model of bovine cartilage explant | OA | Delivered a therapeutically active dose of KAFAK to bovine cartilage explants; Suppressed pro-inflammatory IL-6 expression after IL-1β stimulation; Penetrated into aggrecan-depleted cartilage explants and protect their cargo from proteolytic degradation |

[156] |

| Cationic amphipathic peptide–NF–κB siRNA nanoparticles | Passive (size effect) | NF-κB siRNA | ∼55 nm | p5RHH-scrambled siRNA nanoparticles | In vivo noninvasive murine model of controlled knee-joint impact injury | OA | Mediated chondroprotective effect partially by maintaining cartilage autophagy/homeostasis via modulation of AMPK, mTORC1, and Wnt/β-catenin activity; Mediated chondrocyte differentiation and disruption of cartilage homeostasis |

[157] |

| Positively charged Avidin | Passive (positive charge) | N/A | ∼7 nm | Neutral charged NeutrAvidin | Ex vivo trypsin treated bovine cartilage explants | OA | Showed the ability to diffuse through the full thickness of cartilage and the capacity to bind to sites within the ECM; Showed a 400-fold higher uptake than NeutrAvidin and over 15 days retention within cartilage explants due to the large effective binding site density within cartilage matrix |

[166] |

| Multi-arm cationic nano-construct of Avidin conjugated with DEX | Passive (positive charge) | DEX; Loading capacity: 0.157 ± 0.01 mg/mg |

∼10 nm | Avidin only, Dex only, PEG-Dex, PEG-Dex-hemisuccinate, PEG-Dex-glutarate, PEG-Dex-phthalate | In vitro cartilage explant culture model of OA | OA | Demonstrated the ability of intra-cartilage delivery of Dex and their combinations to chondrocytes; Exhibited rapid penetration through the full thickness of cartilage; Effectively suppressed IL-1α-induced cartilage degeneration over 2 weeks in OA cartilage explant |

[167] |

| PLGA/didodecyldimethylammonium bromide nanoparticles | Passive (positive charge) | N/A | 112.4 ± 37.5 nm | PLGA/poly (vinyl alcohol) nanoparticles | Ex vivo model of OA-like bovine cartilage explants with collagenase type II | OA | Improved cartilage retention of nanoparticles; Reduced over 2-fold retention in arthritic tissue with the presence of synovial fluid; Induced changes to nanoparticle surface properties and colloidal stability in vitro via interactions with synovial fluid |

[43] |

Formica et al. reported the retention capability of a six amino acid peptide (WYRGRL) in cartilage deep zone by specifically binding to collagen type II bundles of cartilage [140]. Nanoparticles conjugated with the peptide could efficiently target the articular cartilage of OA [59,141]. Other collagen-targeting peptides such as WYRGRLC and WYRGRLK have also been developed as moieties of nanocarriers to bond to collagen strands in cartilage, providing versatile tools for pathology research in OA and RA [[142], [143], [144]] (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

A collagen-binding peptide (WYRGRLC) was incorporated in lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles for targeting cartilage. A) Illustration of the hybrid nanoparticle, which has a PLGA-core and a PEG-conjugated lipid shell. The particles can penetrate the cartilage intensely with drug release for chondrocytes; B) The hydrodynamic diameter of the corresponding PLGA cores, lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles, and collagen-targeting lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles; C) The zeta potential (mV) of various nanoparticles; D) A typical TEM picture of collagen-targeting lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles stained with uranyl acetate (scale bar, 50 nm); E) Fluorescence images of femoral head slices treated with collagen-targeting lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (bottom) or DiD-labeled lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (top). The nanoparticles are shown in red, and the nuclei are shown in blue (scale bars: 20 μm); F) After intra-articular injection of fluorescently tagged nanoparticles at various timepoints, pictures of mice knee joints were captured. G) cartilage slice images, stained with Safranin-O, from healthy mice (Naive), OA mice treated with PBS, lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (MK-8722), and collagen-targeting lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (MK-8722), respectively. Scale bars, 100 μm; H) TNF-α, IL-1β, and nitric oxide synthase 2-related mRNA expression in the mice's knee cartilage after treatment with different agents. Reproduced from Ref. [144]with permission from John Wiley and Sons.

4.2.1.2. Nanoparticles decorated with polysaccharide

In addition to penetrating peptides, desirable active drug-delivery nanoparticles for intra-articular therapy of OA and RA can be achieved via decorating nanoparticles with polysaccharide, such as hyaluronan and dextran sulfate. These molecules can efficiently target specific receptors of inflammatory cells.

As a cell surface molecule mediating cell interaction and migration, CD44 escalated in chondrocytes, synovial macrophages, lymphocytes and fibroblasts of arthritic joints. HA, the ligand to CD44, can be decorated onto nanoparticles for actively targeting [145,146]. For instance, HA-coated bovine serum albumin nanoparticles are promising intra-articular therapeutic carriers for OA. Via binding to CD44 on the cell surface, HA potentiates the particles' joint residence and enhances their interaction with chondrocytes [147]. An empty HA nanoparticle without cargo has also been shown to be able to suppress cartilage destruction in OA development. The particle plays a part via fragmented low molecular weight HA-CD44 interaction in OA, along with the underlying mechanism involved in OA [80] (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

HA nanoparticles were constructed to target the CD44 receptor and ameliorate OA. A) Scheme of the HA nanoparticles induced OA therapy; B) TEM images and size distribution of HA-nanoparticles. Scale bar, 100 nm; C) Sequential images of the femoral cartilages after normal mice were intra-articularly injected Cy5.5 and Cy5.5-labeled HA-nanoparticles. Scale bars, 100 μm; D-E) OA mouse cartilage injected intra-articularly once a week with PBS, HA-nanoparticles, or free high-molecular-weight HA 4 weeks post destabilization of the medial meniscus surgery. Relevant Safranin O, CD44 staining, Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) grade, and subchondral bone plate thickness were displayed. (F–I) IκB levels in IL-1β-treated (F,G) and Ad-Cd44-infected (H,I) chondrocytes with or without HA-nanoparticles. Reproduced from Ref. [80] with permission from Elsevier.

Resolution of experimentally induced arthritis occurred more rapidly with intra-articular injection of HA-coated nanostructured lipid particles compared to chondroitin sulfate-coated nanostructured lipid carriers and control, achieved via HA actively targeting CD44 receptors overexpressed in the articular tissue [148].

Scavenger receptors regulate serum albumin, polyanionic macromolecule and oxidized low-density lipoprotein on the surface of macrophages under inflammation. Dextran sulfate is the ligand for scavenger receptor class A and highly expressed on activated macrophages. Researchers have utilized dextran sulfate as a drug cargo in the treatment of arthritis. Dextran sulfate-triamcinolone acetonide conjugate nanoparticles was designed by Peng She et al. [149] for the therapy of OA. The excellent targeting specificity of dextran sulfate-triamcinolone acetonide conjugate (DS-TA) nanoparticles to SR-A was demonstrated. The nanoparticles were also able to decrease the viability of stimulated macrophages and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In addition, intra-articular injection of these particles effectively reduced cartilage degradation in OA [149].

4.2.1.3. Nanoparticles decorated with antibodies

Nanoparticles decorated with antibodies for intra-articular injection may also facilitate drug release for arthritis therapy. Antibodies for collagen type II have been investigated and incorporated in nanoparticles to enhance the interaction with cartilage [150,151]. Locally injected polymeric siRNA nanoparticles modified with collagen type II antibodies could alleviate cartilage damage and protect joint structure in post-traumatic OA [152] (Fig. 8) (see Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

Ameliorating post-traumatic OA with collagen type II antibodies decorated nanoparticles that deliver siRNA. A) Scheme of matrix-targeted nanoparticles which augment siRNA intracellular activity and retention in cartilage damaged locations; B) Formulation scheme for siRNA cargo packing and construction; C) ATDC5 cells activated with TNF were treated with the targeting nanoparticles to silence MMP-13 (siMMP-13 against 50 nM or 100 nM nontargeting siRNA sequences); D) Targeting nanoparticles' retention on both healthy and trypsin-damaged porcine cartilage explants was assessed by using intravital in vivo imaging system (IVIS) imaging of rhodamine-fluorescing polymers. E-H) Long-term MMP-13 knockdown lowered MMP-13 protein levels in cartilage, synovium and allieviated the progress of OA in mechanically stressed joints. Schematic of the Long-term OA mouse model E); MMP-13 expression at the end of week 6 (siMMP-13 versus nontargeting siRNA sequences F); immunohistochemical staining demonstrating decreased MMP-13 protein levels in cartilage when administered with the targeting nanoparticles G); Characteristic images of Safranin O stained cartilage of the femurs in healthy mice (top left) and OA mice treated with siMMP-13, nontargeting siRNA sequences or no treatment; FL, lateral femoral condyle H). Reproduced from Ref. [152] with permission from Elsevier.

Fig. 9.

Modified ZIF-8 nanoparticles alleviated OA via modulating synovial macrophages' metabolic pathways. A) Synthesis of Modified ZIF-8 nanoparticles; B, C) Intracellular gases were regulated via administration of the nanoparticles, dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) probe assisting measurement of M1 macrophages' intracellular H2O2 level B), the O2 indicator [Ru (dpp)3]2 + Cl2] assisting measurement of intracellular O2 level C); D) Western blot of HIF-1α; E) IVIS imaging of intra-articularly injected nanoparticles; F) H&E staining of the cartilage in knee joints of OA mice after nanoparticle therapy. Reproduced from Ref. [155] with permission from American Chemical Society.

Similarly, fluorescent nanosomes conjugated with anti-type II collagen antibodies could accumulate in the knee in proportion to the severity of OA, which would help to diagnose the early osteoarthritic lesions [153].

As a crucial mediator in the pathophysiology of arthritis, IL-6 regulates acute-phase responses, inflammation, and immune responses. Immobilizing IL-6 antibodies at the surface of chitosan-HA nanoparticles can seize and neutralize IL-6. The active targeting nanoparticles' cytocompatibility was validated when cultured with human articular chondrocytes and human macrophages. This approach supplied a valid method for local therapy of arthritic diseases [154]. Anti-CD16/32 antibody modified zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) nanoparticles prolongs the retention time of nanoparticles in knee joints of OA mice. Mechanistically, proinflammatory M1 macrophages are suppressed and M2 macrophage infiltration is upregulated with the modified nanoparticles in the synovium, which leads to recovery of the inflamed cartilage [155] (Fig. 8).

Taken together, the available literature shows that active targeting nanoparticles increase the efficiency of therapeutics for OA and RA. Spatial identification and localization of nanocarriers for intra-articular therapy of inflamed joints underscored the advantages of targeting.

4.2.2. Passive targeting strategies

Several properties of nanocarriers have been taken into account to enhance passive targeting properties towards joints. A critical feature is the particle size, which influences the nanoparticles' penetration into the tissue and transportation between the synovial fluid and surrounding tissue. Penetration of nanoparticles into cartilage is based mainly on porosity, which is influenced by the components of cartilage, including collagen, aggrecan, and chondrocytes. Among them, collagen type II and aggrecan constitute heterogeneous, dense and negatively charged ECM, with a pore size between 6 and 11 nm. Porosity increases with degenerative disease and at greater cartilage depth. The threshold size of nanoparticle penetrating cartilage is still conflicting and inconsistent.

McMasters et al. produced KAFAK-loaded hollow nanoparticles with a 293 nm particle size, which were effective to penetrate deep in osteoarthritic cartilage and enabling the drug payload to be released precisely at the site of inflammation, attenuating the progression of the disease [156]. Peptide–siRNA nano-complexes up to 55 nm can penetrate human OA cartilage ex vivo through the full thickness of cartilage, freely diffusing into chondrocyte lacunae located in the intermediate zone [157]. Although these studies have proved the success of nanoparticles with large size for intra-articular therapy, others have drawn different conclusions. For instance, 138 nm diameter liposomes were unable to penetrate damaged cartilage ex vivo [137]. The reason of the inconsistency most likely lies in other properties of nanoparticles beyond diameter, affecting the ability for materials to enter ECM. These factors include hydrophilicity, shape, surface, experimental conditions such as incubation time, temperature and surface area of cartilage.

Similarly, when nanoparticles are applied in passively targeting synovium of OA and RA, not only the diameter of the formulation but also characteristics of nanoparticles should be considered. Nanoparticles engineered with sizes from 5 to 300 nm have been designed for transfer between synovial membrane and synovial fluid [[158], [159], [160], [161]]. Large particles (>250 nm) tend to passively accumulate naturally in the synovium due to microvascular endothelium and interstitial spaces [162] and lead to prolonged retention of drugs in synovium. Pharmacokinetics of nanoparticles is also influenced by particle shape, which will dictate transporting, interaction of nanoparticles with cell membranes, and margination [163]. Non-spherical particles have been proved to be able to marginate and escape the blood flow more easily [164]. Macrophages are important targets in synovium of arthritis and shape contributes to the rate of macrophage uptake of nanoparticles [163]. Surface chemistry is another property to make impact on passive targeting synovium. PEG on the surface of the nanoparticles is most widely used strategy in surface modification [165]. PEGylated particles have been shown with higher accumulation in inflamed synovium than non-PEGylated ones, leading to improved therapeutic outcomes [152].

Anionic charged cartilage offers another passive targeting strategy in intra-articular nanoparticle therapy. Sulfated proteoglycans contribute to negative charge of the cartilage. When positive charged nanoparticles interact with the tissue, acceleration of transport, short time of drug reaching therapeutic concentration, and extending half-life in vivo is achieved [58]. Avidin, a positively charged drug delivery particle can infiltrate throughout the entire thickness of cartilage explants with diameter <10 nm. In addition, it can stay within cartilage ex vivo for more than 15 days to enhance drug delivery [166]. Multi-arm cationic nano-constructs of avidin have shown promising results in terms of rapid penetration through the full thickness of cartilage at high concentrations, and extended intra-articular retention [167]. When PLGA nanoparticles are surface-modified with didodecyldimethylammonium bromide, a quaternary ammonium cation, the particles are able to passively target cartilage. Within synovial fluid ex vivo, the retention of the modified PLGA nanoparticles is improved 4-fold over the corresponding negatively charged nanoparticles [43]. Positively charged Tantalum oxide nanoparticles have also exhibited an excellent affinity for murine cartilage via Coulombic attraction to the fixed, negatively charged glycosaminoglycans in the cartilage. In this study, it was found that cationic nanoparticles could distribute throughout the entirety of the articular cartilage ex vivo, whereas neutral phosphonate and anionic carboxylate particles showed slow uptake and only accumulated at the superficial zone [168].

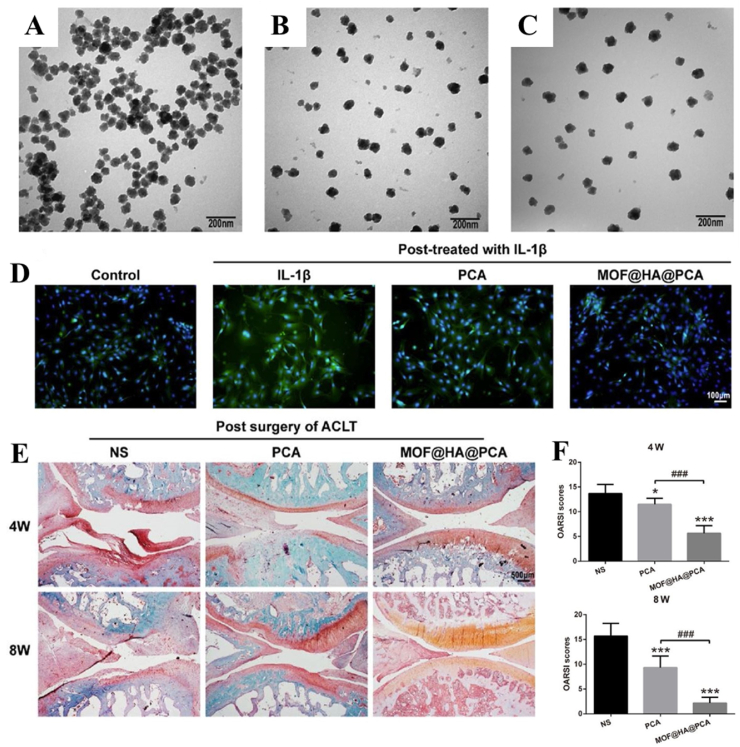

4.3. Nanoparticles designed for controlled release joint therapy