Abstract

Polysaccharides exhibit multiple pharmacological activities which are closely related to their structural features. Therefore, quantitatively quality control of polysaccharides based on their chemical characteristics is important for their application in biomedical and functional food sciences. However, polysaccharides are mixed macromolecular compounds that are difficult to isolate and lack standards, making them challenging to quantify directly. In this study, we proposed an improved saccharide mapping method based on the release of specific oligosaccharides for the assessment of Hericium erinaceus polysaccharides from laboratory cultured and different regions of China. Briefly, a polysaccharide from H. erinaceus was digested by β-(1-3)-glucanase, and the released specific oligosaccharides were labeled with 8-aminopyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic-acid (APTS) and separated by using micellar electrokinetic chromatography (MEKC) coupled with laser induced fluorescence (LIF), and quantitatively estimated. MEKC presented higher resolution compared to polysaccharide analysis using carbohydrate gel electrophoresis (PACE), and provided great peak capacity between oligosaccharides with polymerization degree of 2 (DP2) and polymerization degree of 6 (DP6) in a dextran ladder separation. The results of high performance size exclusion chromatography coupled with multi-angle laser light scattering and refractive index detector (HPSEC-MALLS-RI) showed that 12 h was sufficient for complete digestion of polysaccharides from H. erinaceus. Laminaritriose (DP3) was used as an internal standard for quantification of all the oligosaccharides. The calibration curve for DP3 showed a good linear regression (R2 > 0.9988). The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) values were 0.05 μg/mL and 0.2 μg/mL, respectively. The recovery for DP3 was 87.32 (±0.03)% in the three independent injections. To sum up, this proposed method is helpful for improving the quality control of polysaccharides from H. erinaceus as well as other materials.

Keywords: Saccharide mapping, Hericium erinaceus, Polysaccharide, CE-LIF, PACE

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Specific oligosaccharides were released from polysaccharides by selected enzyme.

-

•

Quantitative saccharide mapping method was firstly developed based on CE-LIF.

-

•

This method was superior to PACE, especially the feasibility of quantification.

1. Introduction

Polysaccharides have recently attracted a growing amount of interest in the biomedical and functional food area due to their numerous possible biological activities [1]. The bioactivities of polysaccharides are closely correlated with their specific chemical properties [2]. For example, β-(1-3)-d-glucans [3] and α-1,3-mannan [4] have been demonstrated to be the main bioactive components in many kinds of edible and medicinal fungi, while glucomannans are responsible for the bioactivities of Dendrobium spp [5].

Hericium erinaceus is a well-known edible and medicinal mushroom with multiple bioactivities, such as antioxidant [6], immunomodulatory [7], and anticancer [8] activities. Usually, polysaccharides, especially β-(1-3)-glucan related polysaccharides, are considered as one of the major bioactive components in H. erinaceus [9], and polysaccharides from H. erinaceus show a wide range of industrial applications. A large number of listed drugs and some proprietary health products contain H. erinaceus extracts as the medicinal ingredients that have penetrated into many aspects of the protection of human health [10]. Commercially available health products, i.e., fresh H. erinaceus oral liquid, have been shown to be effective against gastric mucosal damage and can be used to promote learning and memory [11]. Therefore, qualitative and quantitative analysis of β-(1-3)-glucan related polysaccharides in H. erinaceus are of significant importance, which is beneficial to improving their quality control and their performance in the field of biomedical and functional food.

However, it is challenging to extract information from intact polysaccharides due to their vast molecular mass, structural diversity, and complexity. Research and development of polysaccharide-based products have been hampered by the difficulty in ensuring their quality. So far, several methods to measure β-glucan have been reported, such as quantitative nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and colorimetric and enzymatic assay [[12], [13], [14]]. The structure and quantity of C1 of the glucose chain are inferred using the quantitative NMR approach from the 1H NMR signal. However, this method is only appropriate for purified β-glucan products. The colorimetric assay can quantify β-glucan with triple-helix structures by reaction with Congo red. However, it is also unsuitable for polysaccharides mixtures since they are not β-glucan specific. Alternatively, there are several methods involving converting the β-glucan in a sample into glucose by enzymatic digestion. Due to its use of β-glucan-specific enzymes, the enzymatic technique has more selectivity than the first two methods and may thus be used on samples mixed with other β-glucanase resistant polysaccharides. However, earlier published techniques simply converted glucans into glucose, which is too general and unable to distinguish the changes in structure between different species. Since oligosaccharides carry more structural information than monosaccharides and are therefore more specific, oligosaccharide analysis may offer a way to overcome these challenges.

Currently, saccharide mapping [15], based on a series of endoglycosidases hydrolysis of raw polysaccharides into specific oligosaccharides followed by chromatographic analysis, was established for the qualitative analysis of polysaccharides from different traditional Chinese medicines. According to the saccharide mapping profiles of digested polysaccharides, their similarity can be found and different polysaccharides should be discriminated. This method has been applied to the comparison and characterization of natural and cultured Cordyceps [16], and Pseudostellaria heterophylla from different regions [17]. Compared with the acid catalyzed [18,19] and oxidative chemistry [20] de-polymerization method, the enzymatic hydrolysis procedure is gentle, easily controllable and glycosidic linkage related [21], and the released oligosaccharides are stable and unique for the given polysaccharides, presenting a linear relationship with the content of the parent polysaccharides [18]. Thus, the released specific oligosaccharides can be used as quality markers for the quantitative determination of targeted polysaccharides under an appropriate separation and detection condition. Traditional saccharide mapping methods based on high performance size exclusion chromatography (HPSEC), polysaccharide analysis using carbohydrate gel electrophoresis (PACE), and high performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) are valuable tools for polysaccharide identification and authentication [16,17,22]. However, the existing methods are of low sensitivity and resolution, and therefore unsuitable for quantification. Recently, an ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-fluorescence-mass spectrometry (UPLC-FLR-MS) method has been established to quantify the released specific oligosaccharides from Lentinus edodes in order to address this issue [23], allowing for the qualitative distinction of different fungi polysaccharides. However, liquid chromatographic methods consume large amounts of organic solvents, which can cause environmental pollution. Another high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) method was developed for the quantification of acid released oligosaccharides as a marker to present parent polysaccharides [19]. However, the resolution of the selected two markers, Te-Man-ABEE and Pen-Man-ABEE, needs to be improved.

As an alternative method, capillary electrophoresis (CE) has recently become increasingly popular in the food, beverage, and pharmaceuticals industries for the determination of carbohydrate composition [24,25]. In CE, the electrically charged particles or solute molecules migrate at different rates according to their hydrodynamic volume-to-charge ratios. The main advantages of CE are of short analysis time, high resolution and separation efficiency, as well as minimal consumption of sample and organic solvents. The most commonly used and highly sensitive detection method in carbohydrate analysis is laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) after labeling the sample with a charged fluorophore tag, which allows detection of even fmol to amol amounts of carbohydrates [26].

Therefore, in this study, enzymatic released specific oligosaccharides from H. erinaceus were characterized using saccharide mapping based on CE-LIF analysis. First, β-(1-3)-d-glucanase was applied to obtain the specific oligosaccharides from H. erinaceus polysaccharides before the released specific oligosaccharides were labeled with 8-aminopyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic-acid (APTS) and quantitatively analyzed using CE-LIF. Since the purified reference oligosaccharides are usually difficult to obtain, the strategy of quantification of multiple components by one marker (QMCOM) or single standard to determine multi-components (SSDMC) [27] was applied, which has been employed for the quantitative analysis of carbohydrate modification on glycoproteins from seeds of Ginkgo biloba [28]. We validated this method according to linearity, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantitation (LOQ), precision, accuracy, repeatability, and sample stability. The method described here is beneficial to a better understanding of the structural characters of β-1,3-glucans in H. erinaceus and can also facilitate the quality control of polysaccharides from other plants and fungi.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and chemicals

Six batches (HE01–HE06) of H. erinaceus fruiting body were collected from different regions of China, and three batches (first, second and third harvest, HE07–HE09) were subjected to laboratory culture (Table 1). Identity of the H. erinaceus was confirmed by Prof. Shao-Ping Li, University of Macau, Macao SAR, China. The voucher specimens were deposited at the Institute of Chinese Medical Sciences, University of Macau, Macao SAR, China.

Table 1.

Information of the analyzed samples.

| Codes | Parts | Locations |

|---|---|---|

| HE01 | Fruiting body | Dabieshan, Anhui, China |

| HE02 | Fruiting body | Changshan, Zhejiang, China |

| HE03 | Fruiting body | Jiangshan, Zhejiang, China |

| HE04 | Fruiting body | Shennongjia, Hubei, China |

| HE05 | Fruiting body | Putian, Fujian, China |

| HE06 | Fruiting body | Daxinganling, Heilongjiang, China |

| HE07 | Fruiting body | Lab cultivated |

| HE08 | Fruiting body | Lab cultivated |

| HE09 | Fruiting body | Lab cultivated |

Acetic anhydride was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). β-1,3-d-glucan (BGN), laminaritriose (DP3), and 1,3-β-glucanase (EC 3.2.1.39) were purchased from Megazyme (Wicklow, Ireland). 8-aminonaphthalene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid (ANTS) was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan). Sodium cyanoborohydride (NaCNBH3), ammonium acetate (NH4Ac), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and APTS were purchased from Sigma. Polyacrylamide containing a ratio of acrylamide/N,N-methylenebisacrylamide (19:1, m/m) was obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA). Deionized water was prepared by Millipore Milli-Q Plus system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). All the other reagents were of analytical grade.

2.2. Standard and sample preparation

2.2.1. Preparation of polysaccharides in H. erinaceus

H. erinaceus samples were freeze-dried for 48 h and ground to a fine powder. Each homogenized sample powder (1.0 g) was immersed in 30.0 mL of deionized water and extracted in the water bath (WB22 Memmert, Schwabach, Bavaria, Germany) at 100 °C for 1.5 h, and cooled for 15 min. Then the extract was centrifuged at 4,000 g for 10 min (Allegra X-15R, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA), and the supernatant was evaporated to an appropriate volume under vacuum using a rotary evaporator. Subsequently, the concentrated extracts were precipitated by the addition of 4 times volume of 95% ethanol at room temperature. Then, the sample was centrifuged, and the precipitation was re-dissolved in 15.0 mL of hot water (60 °C). After centrifugation (4,000 g, 15 min), the supernatant was transferred to ultra-centrifugal filtration (molecular weight cutoff: 3 kDa; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and then the low molecular weight compounds (Mw < 3 kDa) were removed by centrifugation (4,000 g, 20 min, 25 °C). Finally, the residual polysaccharides were lyophilized for further analysis.

2.2.2. Hydrolysis of polysaccharides in H. erinaceus

Polysaccharides samples (5.0 mg) were dissolved in 2.0 mL of deionized water and hydrolyzed according to the previously reported method [22]. Briefly, the polysaccharides solutions (300 μL) of each sample were mixed with 1,3-β-glucanase (the final concentration was 2.0 U/mL), and digested at 40 °C. To investigate the time required for complete release of oligosaccharides, the samples were digested for 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 h, respectively. Then the mixtures were heated at 80 °C for 20 min to denature the enzymes and analyzed using high performance size exclusion chromatography coupled with multi-angle laser light scattering and refractive index detector (HPSEC-MALLS-RI) [29]. Under the optimized hydrolysis conditions, the reacted samples were derivatized with ANTS [16] or APTS [30] for PACE and CE analysis, respectively. The polysaccharide standard BGN (5 mg/mL, 100 μL) was treated with 1,3-β-glucanase under the above conditions as positive control. Polysaccharide solution without enzyme, treated as described above, was used as blank control.

APTS was used to label released oligosaccharides [30] and prepared in acetic acid/water (3:17, V/V) at a final concentration of 0.1 M. Prepared dextran ladder, DP3 standard, or oligosaccharides released from H. erinaceus was evaporated to dryness using lyophilizer. 4 μL of 0.1 M APTS and 1 M NaCNBH3 (in dimethyl sulphoxide) were added to each dried sample. The mixture was incubated in a 60 °C water bath for 60 min, and subsequently diluted with water to 200 μL without further purification. Then, 50 μL of the above labeled samples mixed with 50 μL DP3 (5 μg/mL) were used for CE analysis.

2.3. CE separation

CE separation was performed on a Beckman P/ACE MDQ capillary electrophoresis system (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA) equipped with a LIF detector, in which the excitation wavelength was set to 488 nm and emission wavelength to 520 nm. 32 Karat system version 8.0 (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) was used for data acquisition and processing.

Bare fused-silica capillary with 50 cm effective length, 75 μm I.D., and 365 μm O.D. (Yongnian Ruifeng Chromatographic Devices Co., Ltd., Handan, China) was used in capillary zone electrophoresis (CZE) and micellar electrokinetic chromatography (MEKC) separation. The running buffer used in MEKC experiment was 25 mM SDS in 55 mM tetraborate solution, and the running buffer for CZE experiment was 50 mM NH4Ac (pH 2.5) [30]. The pH of BGE was adjusted by a SevenEasy pH-meter (Mettler Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland) with formic acid. The capillaries were washed with 0.1 M sodium hydroxide solution for 10 min, deionized water for 5 min, and the running buffer for 10 min before or after buffer change each day. The capillary was replenished with running buffer for 2 min between runs and the running buffer was renewed after every two runs. Sample injection was performed at a pressure of 0.5 psi for 10 s. The applied voltage was 25 kV and the experiments were carried out at a room temperature of 25 °C.

2.4. Method validation

MEKC was applied to quantify the content of specific oligosaccharides released from H. erinaceus polysaccharides. A commercial DP3 was used as an internal standard, and the calibration curve was constructed at 0.2–10 μg/mL. The calibration curve was obtained by plotting the chromatographic peak areas of DP3 derivatives versus the corresponding saccharide concentrations. The linearity was determined by the coefficient of determination (R2), and the limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) were measured at the signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1 and 10:1, respectively. The quantitative precision was evaluated by determining the intra-day and inter-day variations from the replicate determination of enzymatic hydrolysates of polysaccharide from H. erinaceus, reported as relative standard deviation (RSD%). The intra-day variation was analyzed by six replicates in a day, and the inter-day variation was determined by two injections over three continuous days. The sample stability was investigated at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 12 h from the time of sample preparation. Recoveries were calculated from the slope of the linear regression obtained between the added analyte concentration and the measured analyte concentration.

2.5. PACE analysis

PACE was performed according to the previously reported method [22]. Briefly, all freeze-dried samples were re-dissolved in 200 μL of urea (6 M) and then separated using a vertical slab gel electrophoresis apparatus, Mini-Protean Tetra system from Bio-Rad. Electrophoresis of 30% (m/V) polyacrylamide in the resolving gel with a stacking gel of 8% (m/V) polyacrylamide was applied for the separation of partial acid and enzymatic hydrolysates. Electrophoresis was performed at 0 °C to reduce Joule heat, and the electrophoresis buffer was also cooled at 0 °C before use. The samples were first electrophoresed at 200 V for 10 min, followed by electrophoresis at 700 V for 40 min. Gels were imaged using an InGenius LHR CCD camera system (Syngene, Cambridge, UK) at UV 365 nm.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Sample preparation

Boiling water extraction is a popular and convenient method for the extraction of polysaccharides from natural materials. Therefore, the parameters, including solid-liquid ratio and extraction time, were optimized for complete extraction (HE01). The contents (%) of water soluble polysaccharides were used for determination. The yields of crude polysaccharides were 3.6%, 4.0%, 3.9%, 3.9%, and 3.8%, at a different solid-liquid ratio of 1:15, 1:20, 1:30, 1:40, and 1:50 at 100 °C for 1.5 h, respectively, indicating that the highest yield of soluble polysaccharides was obtained at a solid-liquid ratio 1:20. Then, the extraction time (1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 3.0 h) was extended to optimize the yield of the soluble polysaccharides. The highest polysaccharides yield of 4.0% was obtained under 1.5 h. Therefore, the solid-liquid ratio was set to 1:20 and the temperature was set at 100 °C for 1.5 h to obtain optimal polysaccharides yield. Finally, the polysaccharide was obtained after removing small molecules by using ultra-centrifugal filter (molecular weight cutoff: 3 kDa).

3.2. Enzymatic hydrolysis of H. erinaceus polysaccharides

It has been reported that polysaccharides from H. erinaceus usually consist of glucose, galactose, and rhamnose [10,31]. Moreover, 1,3-β-d-Glcp has been reported to be one of the major glucosidic bonds in the polysaccharides from H. erinaceus [31,32]. Therefore, 1,3-β-glucanase was selected for enzymatic hydrolysis of polysaccharides from H. erinaceus. To investigate the time required for complete release of specific oligosaccharides, the samples were digested with 1,3-β-glucanase for 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 h, respectively. Then, the amounts of digested samples were calculated using HPSEC-MALLS-RI method (Fig. 1). The results showed a gradual decrease in peak areas from 20 to 31 min and an increase in the percentage of digested polysaccharides from 8.2% to 24.6% after 6–10 h incubation compared to undigested polysaccharides. No significant differences in the peak areas were found after 12 and 14 h digestion. Therefore, the enzymatic digestion time of 12 h was sufficient to digest the polysaccharides from H. erinaceus.

Fig. 1.

High performance size exclusion chromatography coupled with multi-angle laser light scattering and refractive index detector (HPSEC-MALLS-RI) chromatogram of polysaccharides from H. erinaceus (HE) digested with 1,3-β-glucanase for 6–14 h.

3.3. Separation effects of different CE separation mechanisms

In CE, different separation modes can be readily achieved by using different separation buffers and buffer additives, with the same instrument. Usually, CZE is commonly used to separate charged analytes. MEKC is the method to achieve the separation of neutral compounds based on the differential partitioning of solutes between the hydrophobic interior of a charged micelle and the aqueous phase. In order to find a suitable mode for saccharide mapping analysis, MEKC (Fig. 2A) and CZE (Fig. 2D) were compared using dextran standards and released specific oligosaccharides from H. erinaceus (HE01) as the test sample. It was reported that SDS micelle in MEKC could trap excess labeling fluorophore and therefore simplify the sample preparation procedure [30]. No peak for excess APTS was observed in this MEKC method, and it indicated the possibility of skip of the removal step for excess APTS fluorophore. In the MEKC mode, the electropherogram of separation of the APTS derivatized dextran ladder showed that the largest analytes migrated first, and the smallest migrated last (Fig. 2A). This was different from CZE result due to the application of a normal polarity separation mode. A large peak capacity between oligosaccharides with polymerization degree of 2 (DP2) and polymerization degree of 6 (DP6) in the separation of dextran ladder by MEKC was found, making it an ideal mechanism for the analysis of specific oligosaccharides released from H. erinaceus polysaccharides (Fig. 2B). Fig. 2C depicts the H. erinaceus sample without the addition of internal standard DP3. In addition, the added internal standard DP3 could be well separated using MEKC (Fig. 2B), but co-eluted in the CZE mode (Fig. 2E). Therefore, the MEKC mode was a better method for the quantitative determination of specific oligosaccharides from H. erinaceus.

Fig. 2.

Separation effects of different capillary electrophoresis (CE) separation mechanisms. (A) Micellar electrokinetic chromatography (MEKC) mode for the separation of dextran hydrolysates, (B) MEKC mode for the separation of released oligosaccharides spiked with DP3, and (C) MEKC mode for the separation of released oligosaccharides without DP3. (D) Capillary zone electrophoresis (CZE) mode for the separation of dextran hydrolysates, and (E) CZE mode for the separation of released oligosaccharides spiked with DP3. Glc: glucose; DP2–5: oligosaccharides with polymerization degree of 2–5; P1–8: peaks 1–8; IS: internal standard.

3.4. Method validation

3.4.1. Linearity, sensitivity, and recovery

Since no oligosaccharide standards were available for the quantitation of specific oligosaccharides from H. erinaceus polysaccharides, DP3, consisting of three glucose molecules linked by 1,3-β-glucoside bonds, was used as the internal standard for the generation of the calibration curve for the released oligosaccharides. Under the optimal experimental conditions, a linear equation y = 321012x−57938 was established with an R2 value of 0.9988 using Origin9.1 software (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA), where y represents the peak area and x represents the corresponding concentration of DP3, with the standard error of 4350 and 2307 for slope and intercept, respectively. The response was found linear in the range of 0.2–10 μg/mL. The LOD and LOQ values for the analyzed compound were 0.05 μg/mL and 0.2 μg/mL, respectively. The recovery for DP3 was 87.32 (±0.03)% in three independent injections.

3.4.2. Precision, reproducibility, and stability

Enzymatic released specific oligosaccharides (P1–P8) of H. erinaceus polysaccharides were used for precision, repeatability, and sample stability investigation (Table 2). For intra-day precision, RSD of the peak area was 4.9%–10.3% and RSD of the retention time was 0.3%–2.4%; for inter-day precision, the corresponding RSD was 3.6%–10.1% and 0.7%–2.1% for peak area and retention time, respectively. For the repeatability, the corresponding RSD was 5.6%–8.6% and 0.4%–0.9% for peak area and retention time, respectively. For the sample stability, RSD of the peak area was 6.6%–10.3%, and RSD of the retention time was 0.4%–0.9%, respectively. The results indicated that the APTS labeled samples were quite stable. The sample stability for APTS labeled oligosaccharides was stable for at least 2 months at −20 °C.

Table 2.

Precision, stability, and reproducibility of the released specific oligosaccharides (P1–P8) from H. erinaceus polysaccharides.

| Peak | Intra-day precision (RSD%) |

Inter-day precision (RSD%) |

Stability (RSD%) |

Reproducibility (RSD%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT | Peak area | MT | Peak area | MT | Peak area | MT | Peak area | |

| P1 | 0.3 | 6.0 | 0.7 | 8.9 | 0.4 | 8.6 | 0.4 | 6.5 |

| P2 | 0.3 | 5.8 | 0.8 | 8.9 | 0.5 | 8.8 | 0.5 | 5.9 |

| P3 | 0.3 | 10.3 | 1.0 | 7.5 | 0.5 | 6.6 | 0.8 | 8.6 |

| P4 | 0.4 | 5.8 | 1.1 | 10.1 | 0.5 | 10.3 | 0.7 | 6.7 |

| P5 | 0.4 | 5.8 | 1.2 | 9.4 | 0.6 | 8.6 | 0.5 | 7.9 |

| P6 | 0.4 | 7.9 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 9.6 | 0.8 | 8.6 |

| P7 | 2.4 | 5.6 | 1.5 | 7.4 | 0.7 | 10.1 | 0.6 | 7.9 |

| P8 | 0.5 | 4.9 | 2.1 | 9.3 | 0.9 | 8.4 | 0.9 | 5.6 |

MT: migration time; RSD: relative standard deviation.

3.5. Quantification of the released specific oligosaccharides from H. erinaceus polysaccharides

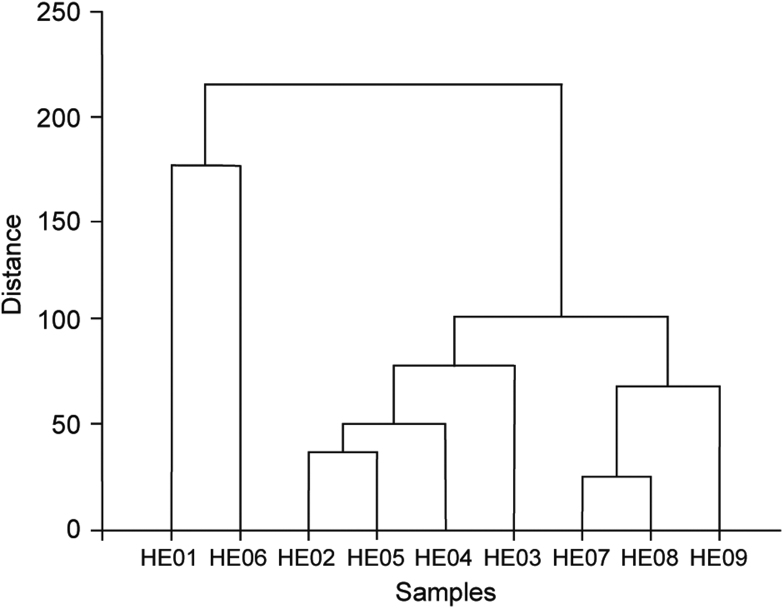

The contents of the eight released specific oligosaccharides in samples HE01–HE09 were determined using the developed method, and the results are shown in Fig. 3; the relative contents of the specific oligosaccharides are listed in Table 3. The results indicated that these samples released different amounts of oligosaccharides. In particular, much higher contents of P6 (121.6 μg/g) and P7 (56.2 μg/g) were detected in sample HE06 from Daxinganling, Heilongjiang, China. The total contents of released oligosaccharides were the highest in sample HE01 (741.5 μg/g) from Dabieshan, Anhui, China, followed by HE06 (610.9 μg/g) from daxinganling, Heilongjiang, China. However, the laboratory-cultured samples contained much lower amounts, from the first harvest sample (HE07, 228.5 μg/g) increased to the second (HE08, 244.6 μg/g) and third harvest (HE09, 339.7 μg/g) samples, indicating that the longer cultivation procedure may favor the accumulation of β-1,3-glucosidic bond related polysaccharides. In addition, hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) based on the contents of released oligosaccharides from samples HE01−HE09 was also carried out using Origin 9.1 software. Three clusters were obtained from the HCA dendrogram (Fig. 4), with peak 4 (P4) fitting this trend well. The highest levels of oligosaccharide (P4) released in samples HE01 and HE06 belonged to one cluster with 141.2 μg/g and 130.1 μg/g, respectively. The contents of P4 from samples HE02−05 which were in the range of 59.1–68.6 μg/g were in the second cluster. While the lowest P4 contents (18.5–34.4 μg/g) in laboratory-cultured samples HE07, HE08 and HE09 belonged to the third cluster. Therefore, this developed CE-LIF method could be applied for the quality analysis of H. erinaceus samples from different origins. Indeed, the content of released oligosaccharides presented a linear relationship with that of the parent polysaccharides using dextran and pullulan as models [18]. Though the contents of released specific oligosaccharide and the parent polysaccharides from H. erinaceus were not comparable in this work, the polysaccharides content absolutely could be reflected by the content of released specific oligosaccharide.

Fig. 3.

Micellar electrokinetic chromatography (MEKC) chromatograms of specific oligosaccharides released from H. erinaceus (HE) polysaccharides. (A) HE01, (B) HE02, (C) HE03, (D) HE04, (E) HE05, (F) HE06, (G) HE07, (H) HE08, (I) HE09, and (J) blank, sample without enzyme digestion. P1–8: peaks 1–8; IS: internal standard.

Table 3.

Estimated contents (μg/g) of the released specific oligosaccharides (P1–P8) from H. erinaceus polysaccharides.

| Code | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | Sumb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HE01 | 65.5a | 89.5 | 35.7 | 141.2 | 96.2 | 38.5 | 57.8 | 217.1 | 741.5 |

| HE02 | 46.5 | 49.5 | 18.7 | 64.5 | 60.4 | / | / | 70.9 | 310.4 |

| HE03 | 47.9 | 31.6 | 77.9 | 59.9 | 65.8 | 19.3 | 12.9 | 112.1 | 427.5 |

| HE04 | 29.7 | 52.8 | 11.8 | 59.1 | 42.6 | 11.3 | 13.4 | 102.3 | 322.9 |

| HE05 | 61.3 | 52.0 | 22.6 | 68.6 | 78.6 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 95.9 | 398.7 |

| HE06 | 73.7 | 68.6 | 8.9 | 130.1 | 82.5 | 121.6 | 56.2 | 69.2 | 610.9 |

| HE07 | 10.9 | 54.0 | 21.0 | 18.5 | 11.4 | 10.2 | 9.7 | 92.7 | 228.5 |

| HE08 | 20.2 | 52.3 | 15.8 | 29.3 | 29.7 | 7.0 | 5.6 | 84.5 | 244.6 |

| HE09 | 25.0 | 47.7 | 17.2 | 34.4 | 40.9 | 12.2 | 11.6 | 150.7 | 339.7 |

The sample codes are the same as in Table 1.

/: undetected or under limit of quantification (LOQ).

The data are presented as average of duplicates; their relative average deviation is less than 5.0%.

Total amount of eight released specific oligosaccharides.

Fig. 4.

Hierarchical clustering analysis (PCA) of samples HE01−HE09 based on the contents of released oligosaccharides.

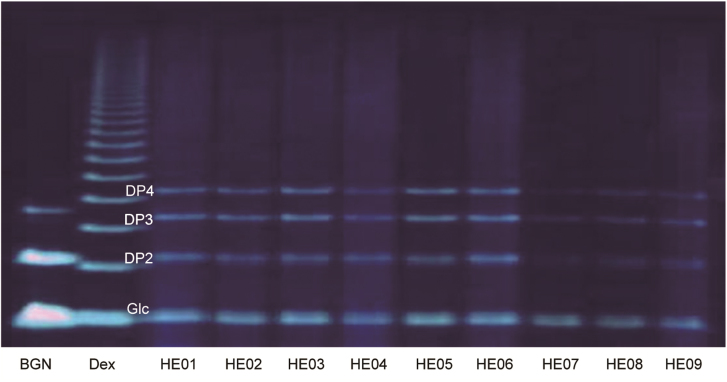

In addition, H. erinaceus samples from HE01 to HE09 were also analyzed by using PACE (Fig. 5), showing a similar chemical profile of released saccharides, which was in accordance with our previous report [33]. In the PACE profiles, three main bands were identified, in addition to monosaccharides, which may correspond to disaccharide, trisaccharide and tetrasaccharide. However, saccharide isomers from the released mixer were not separated compared to the MEKC method established in this study.

Fig. 5.

Polysaccharide analysis using carbohydrate gel electrophoresis (PACE) profile of specific oligosaccharides released from samples HE01 to HE09. Dex: partial acid hydrolysates of dextran; BGN: 1,3-β-d-glucan digested with 1,3-β-glucanase; Glc: glucose; DP2–4: oligosaccharides with polymerization degree of 2–4.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we developed a new quantitative saccharide mapping method based on specific oligosaccharides using MEKC-LIF, which was sensitive and obtained high resolution compared with the commonly used PACE method. In addition, enzymatic hydrolysates of specific oligosaccharides from nine batches of H. erinaceus were quantitatively profiled. Detailed structures of the released oligosaccharides may be elucidated by coupling CE with MS detectors or with isolated pure saccharides for a comprehensive understanding in future work. Nevertheless, this method provides a fresh, straightforward way of characterizing polysaccharides from natural sources, and it is helpful for ensuring the quality of polysaccharides derived from other edible and medicinal mushrooms.

CRediT author statement

Yong Deng: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original draft preparation; Jing Zhao: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - Reviewing & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition; Shao-Ping Li: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - Reviewing & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The research was partially funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.: 81673389), the Science and Technology Development Fund, Macao SAR, China (File Nos.: 0075/2018/A2, 034/2017/A1 and 0017/2019/AKP), the Guangdong Key Project for Modernization of Lingnan Herbs (Project No.: 2020B1111110006), and the Multi-Year Research Grant from the University of Macau (File Nos.: MYRG2018-00083-ICMS, MYRG2019-00128-ICMS, and CPG2022-00014-ICMS).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Xi'an Jiaotong University.

Contributor Information

Jing Zhao, Email: zhaojing.cpu@163.com.

Shaoping Li, Email: lishaoping@hotmail.com, spli@um.edu.mo.

References

- 1.Yu Y., Shen M., Song Q., et al. Biological activities and pharmaceutical applications of polysaccharide from natural resources: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018;183:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li S., Wu D., Lv G., et al. Carbohydrates analysis in herbal glycomics. Trends Anal. Chem. 2013;52:155–169. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vannucci L., Krizan J., Sima P., et al. Immunostimulatory properties and antitumor activities of glucans (Review) Int. J. Oncol. 2013;43:357–364. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu D., An L., Liu W., et al. In vitro fecal fermentation properties of polysaccharides from Tremella fuciformis and related modulation effects on gut microbiota. Food Res. Int. 2022;156 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng Y., Li M., Chen L.-X., et al. Chemical characterization and immunomodulatory activity of acetylated polysaccharides from Dendrobium devonianum. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018;180:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X., Yin J., Zhao M., et al. Gastroprotective activity of polysaccharide from Hericium erinaceus against ethanol-induced gastric mucosal lesion and pylorus ligation-induced gastric ulcer, and its antioxidant activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018;186:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Y., Ye H., Zhao C., et al. Value added immunoregulatory polysaccharides of Hericium erinaceus and their effect on the gut microbiota. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021;262 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.117668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J., Hou X., Li Z., et al. Isolation and structural characterization of a novel polysaccharide from Hericium erinaceus fruiting bodies and its arrest of cell cycle at S-phage in colon cancer cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;157:288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.04.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y., Liu X., Zhao J., et al. The phagocytic receptors of β-glucan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022;205:430–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.02.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He X., Wang X., Fang J., et al. Structures, biological activities, and industrial applications of the polysaccharides from Hericium erinaceus (Lion's Mane) mushroom: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;97:228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L.-L., Guo H.-G., Wang Q.-L., et al. A preliminary study of fresh Hericium erinaceus oral liquid on health-care function and promotion of learning and memory. Mycosystema. 2011;30:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowman D.W., Williams D.L. A proton nuclear magnetic resonance method for the quantitative analysis on a dry weight basis of (1→3)-β-d-glucans in a complex, solvent-wet matrix. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001;49:4188–4191. doi: 10.1021/jf010435l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nitschke J., Modick H., Busch E., et al. A new colorimetric method to quantify β-1,3-1,6-glucans in comparison with total β-1,3-glucans in edible mushrooms. Food Chem. 2011;127:791–796. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.12.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ide M., Okumura M., Koizumi K., et al. Novel method to quantify β-glucan in processed foods: Sodium hypochlorite extracting and enzymatic digesting (SEED) assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66:1033–1038. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b05044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li S., Wu D., Zhao J. Saccharide mapping and its application in quality control of polysaccharides from Chinese medicines. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2015;40:3505–3513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu D.-T., Cheong K.-L., Wang L.-Y., et al. Characterization and discrimination of polysaccharides from different species of Cordyceps using saccharide mapping based on PACE and HPTLC. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014;103:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng Y., Han B.-X., Hu D.-J., et al. Qualitation and quantification of water soluble non-starch polysaccharides from Pseudostellaria heterophylla in China using saccharide mapping and multiple chromatographic methods. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018;199:619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L.-F., Wong T.-L., Zhang J.-X., et al. An oligosaccharide-marker approach to quantify specific polysaccharides in herbal formula by LC-qTOF-MS: Danggui Buxue Tang, a case study. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020;185 doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong T.-L., Li L.-F., Zhang J.-X., et al. Oligosaccharide-marker approach for qualitative and quantitative analysis of specific polysaccharide in herb formula by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry: Dendrobium officinale, a case study. J. Chromatogr. A. 2019;1607 doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2019.460388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amicucci M.J., Nandita E., Galermo A.G., et al. A nonenzymatic method for cleaving polysaccharides to yield oligosaccharides for structural analysis. Nat. Commun. 2020;11 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17778-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Zaal P.H., Klostermann C.E., Schols H.A., et al. Enzymatic fingerprinting of isomalto/malto-polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;205:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu D.-T., Xie J., Hu D.-J., et al. Characterization of polysaccharides from Ganoderma spp. using saccharide mapping. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013;97:398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.04.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng Y., Chen L.-X., Zhu B.-J., et al. A quantitative method for polysaccharides based on endo-enzymatic released specific oligosaccharides: A case of Lentinus edodes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022;205:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mantovani V., Galeotti F., Maccari F., et al. Recent advances in capillary electrophoresis separation of monosaccharides, oligosaccharides, and polysaccharides. Electrophoresis. 2018;39:179–189. doi: 10.1002/elps.201700290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D'Orazio G., Asensio-Ramos M., Fanali C., et al. Capillary electrochromatography in food analysis. Trends Anal. Chem. 2016;82:250–267. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kabel M.A., Heijnis W.H., Bakx E.J., et al. Capillary electrophoresis fingerprinting, quantification and mass-identification of various 9-aminopyrene-1,4,6-trisulfonate-derivatized oligomers derived from plant polysaccharides. J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1137:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li S.-P., Qiao C.-F., Chen Y.-W., et al. A novel strategy with standardized reference extract qualification and single compound quantitative evaluation for quality control of Panax notoginseng used as a functional food. J. Chromatogr. A. 2013;1313:302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang T., Hu X.-C., Cai Z.-P., et al. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of carbohydrate modification on glycoproteins from seeds of Ginkgo biloba. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017;65:7669–7679. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheong K.-L., Wu D.-T., Zhao J., et al. A rapid and accurate method for the quantitative estimation of natural polysaccharides and their fractions using high performance size exclusion chromatography coupled with multi-angle laser light scattering and refractive index detector. J. Chromatogr. A. 2015;1400:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng H.-T., Su M., Rifai F.N., et al. Parallel analysis and orthogonal identification of N-glycans with different capillary electrophoresis mechanisms. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2017;953:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2016.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan J.-K., Ding Z.-C., Gao X., et al. Comparative study of physicochemical properties and bioactivity of Hericium erinaceus polysaccharides at different solvent extractions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018;193:373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie B., Yi L., Zhu Y., et al. Structural elucidation of a branch-on-branch β-glucan from Hericium erinaceus with A HPAEC-PAD-MS system. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021;251 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu D.-T., Li W.-Z., Chen J., et al. An evaluation system for characterization of polysaccharides from the fruiting body of Hericium erinaceus and identification of its commercial product. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;124:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]