Abstract

Many burn survivors experience social challenges throughout their recovery. Measuring the social impact of a burn injury is important to identify opportunities for interventions. The aim of this study is to develop a pool of items addressing the social impact of burn injuries in adults to create a self-reported computerized adaptive test based on item response theory. The authors conducted a comprehensive literature review to identify preexisting items in other self-reported measures and used data from focus groups to create new items. The authors classified items using a guiding conceptual framework on social participation. The authors conducted cognitive interviews with burn survivors to assess clarity and interpretation of each item. The authors evaluated an initial pool of 276 items with burn survivors and reduced this to 192 items after cognitive evaluation by experts and burn survivors. The items represent seven domains from the guiding conceptual model: work, recreation and leisure, relating to strangers, romantic, sexual, family, and informal relationships. Additional item content that crossed domains included using self-comfort and others’ comfort with clothing, telling one’s story, and sense of purpose. This study was designed to develop a large item pool based on a strong conceptual framework using grounded theory analysis with focus groups of burn survivors and their caregivers. The 192 items represent 7 domains and reflect the unique experience of burn survivors within these important areas of social participation. This work will lead to developing the Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation profile, a self-reported outcome measure.

With the steady increase in survival rates after a burn injury, survivors have reported experiencing difficulties in returning to work, maintaining their personal relationships, and continuing activities that are important to them.1-5 These challenges may be greater for those with burns to critical areas that include face, hand, feet, or genitals. With more burn survivors living and returning to their communities, social, and professional lives, there is a need for patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures that capture the increasingly important social areas of recovery.

Existing burn-specific questionnaires primarily focus on physical and not social outcomes. Although the Burn Outcome Questionnaires do contain dimensions of social function, family, and work reintegration, they are tailored to pediatric and young adult populations.6 Burn care is oriented toward survivors’ recovery and return to their communities. Current measures are lacking the breadth and depth that are required to track burn survivor’s progress for these important life areas. Previous work has focused on developing a conceptual framework for building an instrument that measures the social impact of burn injuries.7 The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health provides the conceptual grounding for a content model that focuses on two main concepts: societal role and personal relationships, which includes the subdomains of work, recreation, and leisure, relating to strangers, romantic relationships, sexual relationships, family, and informal relationships.

This article reports on the development of survey questions (what we call “items”) we employed for a new PRO instrument that measures the social impact of burn injuries. We developed this pool of items with the goal of building a PRO, the Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation (LIBRE Profile), to measure social functioning throughout a burn survivor’s recovery.

METHODS

We conducted a structured literature review to collect items from existing generic, burn-specific, and other condition-specific PRO measures published in English. New items were written based on input from focus groups, and all items were refined through cognitive testing.

The LIBRE Profile employs a methodology called item response theory (IRT), where each item is ordered in a hierarchy along a unidimensional construct. Computerized adaptive testing (CAT) is a method of administering IRT-based instruments. For a broad concept such as social impact of burns, there are a large number of areas that need to be measured to capture the breadth of issues, and there is a wide range of possible items within each particular area. Therefore, a primary goal of item development is generating a large item pool that reflects the breadth and depth of concepts that we wish to capture. To administer the LIBRE Profile in a feasible way, we will employ a technique called CAT where a computer algorithm selects each subsequent question based on how a respondent answers previous questions. The CAT approach allows for the skipping of items irrelevant to a person’s ability or status, which minimizes the burden of administration without sacrificing measurement precision.

We identified 19 PRO measures as part of the literature review (methods of literature review described in the study by Marino et al7). Items from those measures were first binned by two reviewers, who were selected based on their experience conducting the literature review and developing the conceptual framework. Binning refers to a rigorous process for categorizing items into domains on the basis of a latent construct. When there was disagreement between the reviewers, several burn injury content experts were consulted about inclusion.8 Six content experts were provided with the study’s conceptual framework, the list of agreed upon items, and the items where there was disagreement about relevancy or mapping to the conceptual framework. In addition, we conducted four focus groups with burn clinical experts and survivors, which were transcribed and coded using grounded theory methodology.9,10 This approach has been recommended as a best practice to ensure that items are developed with rigorous methods and used to ultimately arrive at a final pool of items that are accurate, are exhaustive, and have content and face validity.11,12

We winnowed down the items based on the refining of the content models to ensure that the item pool was representative of the areas discussed by burn survivors and clinicians. The same two independent reviewers winnowed the items by flagging those that were irrelevant, repetitive, or in need of revision. Those that required revisions were brought to the larger research team along with a list of content areas and themes noted in the focus groups for which there were no items. When there were no suitable legacy items for content identified in the framework as important to social participation of burn survivors, new items were written. Whenever possible, the language of the burn survivors and clinicians were used in the item wording to maximize fidelity to the original concept conveyed.

The preliminary list of items was then cognitively evaluated with burn survivors by conducting debriefings to assess the clarity and the consistent interpretation of each item.13 Item pools were divided into modules of 15 to 25 items based on content areas. Each burn survivor provided feedback on two to three modules. Each item was reviewed by two to three different burn survivors to facilitate item revision when disagreements in the feedback from the burn survivors arose.13 For these cognitive evaluation interviews, targeted verbal probes were used, including asking participants to rephrase the items in their own words, pointing out any words that were confusing or hard to understand, and providing the investigators with feedback on the item stems and response scales. A nonrandom sample of 23 participants was recruited from a regional support group of burn survivors and clinical database of burn survivors interested in participating in research. Snowball sampling was also used to reach the target sample size. Those who participated in the focus groups were not eligible to participate in cognitive evaluation of the items. After the cognitive interview process, the research group examined the feedback, revised items, and then gave the revised item pool to content experts for final review.

RESULTS

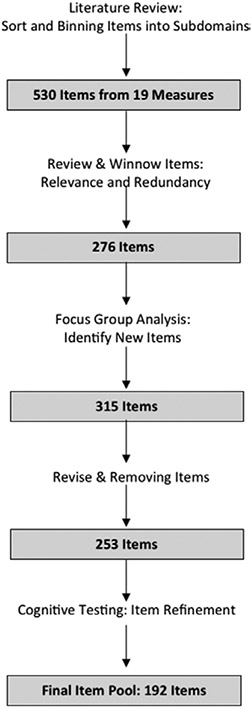

The literature review yielded 19 measures with a total of 530 items14-32 (Table 1). After binning, winnowing, and writing new items, there were 253 items that were cognitively evaluated. The final item pool after cognitive testing was 192 items (Figure 1). Of these 192 measures, 100 were originally written for the LIBRE Profile and were unique to this item pool, 88 items came from other legacy measures but were either altered to reflect a specific issue discussed by a burn survivor or changed for clarity based on the feedback in cognitive interviews. Only four items were retained from previously used measures in their original form.

Table 1.

Identified questionnaires included in the literature review

| Measure | Candidate Items Identified |

|---|---|

| Young Adults Burn Outcomes Questionnaire6 | 22 |

| The Burn Specific Health Scale21 | 14 |

| Sexuality After Burn Injury Questionnaire17 | 31 |

| The Female Sexual Function Index19 | 19 |

| The International Index of Erectile Function20 | 15 |

| Intimate Bond Measure29 | 12 |

| Dyadic Adjustment Scale18 | 32 |

| Fear of Intimacy Scale30 | 35 |

| Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire27 | 18 |

| Differential Loneliness Scale33 | 58 |

| Index of Sexual Satisfaction22 | 25 |

| Satisfaction With Appearance Scale16 | 13 |

| Neuro-QOL25 | 115 |

| PROMIS8 | 40 |

| Perceived Stigmatization Questionnaire14 | 21 |

| Social Comfort Questionnaire15 | 8 |

| Body Image Quality of Life Inventory24 | 19 |

| Coping With Burns Questionnaire28 | 33 |

| Total | 530 |

PROMIS, patient-reported outcomes measurement information system; QOL, quality of life.

Figure 1.

Item identification, development, and revision process.

Some themes emerged from the focus groups that were not anticipated in the study’s conceptual framework: “self-comfort and others’ comfort with clothing,” “telling one’s story,” and “sense of purpose.” Because these themes were pervasive in the focus groups, they were used to create items (Table 2). Burn survivors talked about clothing as a way to cover up their burns, as landmarks of progress in their comfort with other people seeing their burns, and as something that people in their lives often had strong opinions about. One burn survivor commented that “My burn is so recent that I’ve loved this hard, long winter because I’m all covered up. And I’m dreading the warm weather when I go to short sleeves and short skirts. I don’t know how I’m going to feel, never mind thinking about how people around me will feel.” The same participant further stated that “My two sons are the ones that put the fire out when I was burning and they don’t like to see anything…So that’s why I like to cover them up with capris that cover most of them. And I always have -quarter-length sleeve because I have–like, my arm goes in and there’s nothing that–… And my husband does it, too. So I can’t visibly go out and look like that, because it throws things back at them.” Several burn survivors discussed how they used clothing as a way of covering up their burns to avoid stares from strangers, and then a gradual process of becoming comfortable with others seeing their burns corresponded with gradually changing their clothing.

Table 2.

Themes used as content areas unique to burn survivors

| Theme/ Content Area |

Quotations | Items Developed |

|---|---|---|

| Clothing |

“I think you work your way slowly into it. I started with a skirt with a pair of tights.”

“First I went to the pedal pushers. And you know, the three-quarter length. And last year I said, oh, hell with it, I’ll put back on my short-shorts.” “When you learn to wear whatever clothes you want and just tell everybody, “Don’t look, you don’t have to look at it.” |

I dress to avoid stares. I feel that my partner accepts how I look. My family is comfortable with my burns being seen in public. |

| Telling your story | “And if somebody’s curious and comes up and starts conversation with me, I talk to them. And they usually are—the ones that are brave enough to come up to you and talk to you are usually [brave] enough to ask, ‘Do you mind if I ask what happened?’…I was taught when I first got in here, be able to tell your story in five minutes or less and go on…” | I am upset when strangers comment on my burns. I don’t mind when strangers ask me about my burns. I am comfortable explaining my burns to strangers. |

| Sense of purpose |

“I learned after a number of years that my purpose in life was to pay it forward and help others and then have a passion in this burn community, that is I could make a difference in someone’s life then I was going to do it. And I set out to do that.”

“Like when I was little, I was raised with siblings who have disabilities, and I was raised with taking care of other people. All my life has been about taking care of other people, which I love. I couldn’t imagine it any other way. In fact, what I want to do with my career is to go on and take care of people” |

My burns give me a greater sense of purpose. I like helping other burn survivors. My burns help me understand other people’s problems. |

The theme of “telling one’s story” incorporates the notion that many burn survivors had varying levels of comfort with sharing their burn experience with strangers, people at work, or talking about their experience with those close to them. The importance of this theme was not that constant full disclosure is a signal of recovery, but rather about each survivor finding a way to talk about experiences in the ways that are most comfortable for him or her: “When you reach towards acceptance, like myself, I tell a story… I just share one, quick story. Somehow it came up in a conversation with this client I’d known for 20 years, ‘I’m doing some work in [hospital]. And I volunteer at the burn unit.’ ‘Oh, well, how did you get involved with that?’ ‘Well, I was in a house fire…’” Items related to this theme were written for relating with strangers, family, and informal relationships domains.

Many burn survivors talked about how their experience of both their burn and their recovery and rehabilitation has helped them gain greater insights and purpose in life. This took many forms such as new perspectives on relationships, new vocational callings, and particularly in becoming a part of a burn survivor community and helping others in similar situations. “Long run I think I’m much more empathic person. And I think when other people I know are going through things that are really hard, they’re a bit more comfortable going to me because they think, because I’ve been through something analogous.”

Twenty-three burn survivors participated in the cognitive interviews, 13 men and 10 women. The TBSA burned for the sample ranged from 1 to 94% with an average of 28.3%, and the time since burn injury ranged from 3 months to 38 years, with an average of 9.3 years.34 The average age was close to 50 years, the majority of participants were white, and six of the participants had a high school diploma or less (Table 3). Table 4 gives selected examples of original items and how they were refined based on the quotations from the burn survivors in focus groups and feedback from cognitive testing. All items were written at an average sixth grade reading level or lower and assessed using the Lexile Analyzer (https://lexile.com/analyzer/). Items are both “positive” and “negative” phrased and theoretically represent a continuum of “difficulty” or “functioning” rather than solely an average level. The item pool contains questions and statements with three different response categories: “strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree, not applicable”; “never, almost never, sometimes, often, always”; and “not at all, a little bit, some-what, quite a bit, very much.”

Table 3.

Cognitive interview participants: demographics

| n | 23 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 10 |

| Male | 13 |

| Age (yr) | 24 to 71 |

| Race | |

| White | 22 |

| Other | 1 |

| Years since burn injury | 3 mo to 38 yr |

| TBSA | 1–94% |

| Education | |

| High school diploma or less | 6 |

| Greater than high school | 17 |

Table 4.

Items written and refined based on cognitive interviews

| Subdomain | Tested Item | Interview Feedback | Revised Item |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work and employment | I feel hopeless about finishing certain work tasks, because my burn injury. | There are two parts to this question, there is physical labor which is more task, and then there are general/mental limitations at work… The word “hopeless” pre-sets what you are looking for. | Because of my burns, I am unable to finish many work tasks. |

| Recreation and leisure | I am limited in how I spend my free time. | I am not sure if that means that there are things that I want to do but can’t or that there are more constraints on my free time. | My burns limit the fun things I can do in my free time. |

| Relating with strangers | How I feel affects how people react to me. |

Right now though, how I look affects more how people react to me than how I feel. I could be happy and people will still avoid me.”

“If I’m not in a good mood people aren’t going to be around me. If I’m friendly, people would want to be around. Don’t know how it relates to burn injury.” |

I can help strangers feel comfortable around me. |

| Romantic relationships | How often do you and your partner work together on a project? |

I don’t know what kind of project—is it a school or work project, is it building a shelf?

“Project” is confusing, I’m not sure what that means. |

How often do you and your partner do things together? |

| Sexual relationships | My lack of interest in sex is a problem. | For whom? My lack of interest is a problem for me or is it a problem for my partner? Or is it just something I worry about? “Problem” covers a lot. | I am not interested in sex anymore. |

| Family relationships | My family allows me to feel bad. | “You can interpret this in a few ways: (1) my family is neglecting my feelings and letting me feel bad; (2) my family doesn’t overact and allows me to feel my feelings—everyone has bad days. I’m not sure which you’re getting at.” | My family helps me through my bad days. |

| Informal relationships | How I look affects how I act with my friends. | With respect to the injury? Or am I trying to answer more globally? | I think my friends are uncomfortable being with me because of my burns. |

The distribution of the final 192 items is representative of all of the domains of the conceptual framework7 as presented in Table 5. There are several features assessed for each domain with at least three items. Work and employment items involve physical and emotional content related to finding, maintaining, and advancing in a job, as well as interpersonal interactions with coworkers and supervisors. Recreation and leisure items ask questions about a person’s ability to engage in and satisfaction with activities such as running errands, sports, hobbies, and general community events. For relating with strangers, the items ask about particular interactions with strangers, comfort level in public situations, and general behaviors regarding interacting with strangers. Family and friend items focus on the amount of support one gets from others, the comfort level in the relationships, and activities one does with family and friends. Questions about romantic relationships are asked specific to an individual partner and cover content involving emotional and physical attractions, communication, and support. Sexual relationship items involve desire and interest toward sex, satisfaction with sexual activity, sexual confidence, and sexual intimacy. The items in both the romantic and sexual relationship domains are written in gender neutral terms to be universal regardless of sexual orientation.

Table 5.

Final item pool by conceptual domain

| Subdomain | Number of Items |

Original Items |

Modified Items |

Original Unchanged Legacy Items |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work and employment | 27 | 16 | 11 | 0 |

| Recreation and leisure | 21 | 11 | 9 | 1 |

| Relating to strangers | 22 | 11 | 10 | 1 |

| Romantic relationships | 35 | 15 | 20 | 0 |

| Sexual relationships | 21 | 12 | 9 | 0 |

| Family relationships | 30 | 17 | 12 | 1 |

| Informal relationships | 33 | 15 | 17 | 1 |

| Other | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 192 | 100 | 88 | 4 |

DISCUSSION

We applied a conceptual framework to guide the identification and development of a large pool of items that address in depth on the social areas of life affected by a burn injury. The resulting 192 items represent a continuum of functioning across the subdomains of work and employment, recreation and leisure, relating with strangers, and romantic, sexual, family, and informal relationships.

The grounded theory approach that we used in this work provides significant advantages over other approaches to questionnaire development. When using grounded theory methodology, the data are the foundation for theory building: in this case, the conceptual framework and item generation. By keeping the LIBRE Profile items directly linked to the data—the transcripts from the focus groups—they are directly rooted in burn-specific issues as identified by survivors and caregivers who work with them. Given that the ultimate purpose of developing this pool of items was to use in an IRT-based instrument, this methodology enabled us to obtain a large number of items reflective of the range of domains and the range of experiences expressed by burn survivors within each domain. Although other approaches such as literature review only or phenomenology may be more suited to other purposes, grounded theory allows investigators to work without preconceived hypotheses about topics and items to include. This methodology allows the content areas and language for items to emerge from the data, thereby enhancing content validity.

Given the grounded theory approach, the resulting LIBRE item pool that was generated is different from the item pool in other measures currently used. Although the domains in which the items are grouped may have some overlap with other burn-specific and generic measures used in the burn survivor population, the actual item content within them is quite unique. For example, the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system social roles and social discretionary activities scales ask about the satisfaction with ability to do leisure activities, but do not capture the multitude of unique ways a burn survivor may engage in leisure activities and challenges that he or she may face. In our recreation and leisure domain, by comparison, items specifically mention issues such as fatigue, concerns about appearance, and the reported therapeutic value of the activities, exemplified by items such as “I tire easily when doing things for fun.” and “I do things I enjoy, even if I have to do them differently.” Similarly, other generic outcome instruments35 may have items about interpersonal relations, but they fail to capture the burn-specific issues uncovered in our focus groups such as “My family is over protective of me,” and “I feel that my partner accepts how I look,” and “My friends have helped me get out of the house.” The LIBRE set of items is also more comprehensive than the burn-specific questionnaires currently being used. For example, the young adult burn outcome questionnaire asks several sexual questions; but the LIBRE item pool goes beyond the mechanical aspects of sex and also contains items such as “My burns affect my confidence as a sexual partner.”

Several limitations of the approach and findings in this article should be noted. First, because of the use of a locally based nonrandom sample, there may be differences in the interpretation and perceived applicability and relevance of the items to burn survivors in other geographic areas. Similarly, the cognitive interviewing participants were almost all white, and there may be race or ethnicity differences in interpretation not observed in this sample. Finally, the sample contained six burn survivors with a high school diploma or less, and the sample as a whole was fairly educated. Although the items were all written to be at an average of a sixth grade reading level, there may be issues in interpretation and clarity in participants with lower educational achievement. The further work currently underway to develop a final measure involves administering these items to a large sample of burn survivors from across North America.

The large item pool that emerged from this development work serves as the foundation for building a new quantitative PRO instrument, the LIBRE Profile. All items will be administered to a large sample of burn survivors and analyzed to assess the unidimensionality of the hypothesized constructs using advanced psychometric approaches included in the framework and to calibrate the items into quantitative scales.36-38 Future empirical studies will include psychometric analyses based on factor analysis and IRT to validate the created scales to be administered as a CAT. The LIBRE Profile instrument could be used to develop trajectories of social impact and recovery after major burn injuries, which can help demonstrate the effect of different rehabilitation and social-based intervention programs over time.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grants 90DP0055 and 90DP0035). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this article do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Esselman PC, Ptacek JT, Kowalske K, Cromes GF, deLateur BJ, Engrav LH. Community integration after burn injuries. J Burn Care Rehabil 2001;22:221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blakeney P, Partridge J, Rumsey N. Community integration. J Burn Care Res 2007;28:598–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brych SB, Engrav LH, Rivara FP, et al. Time off work and return to work rates after burns: systematic review of the literature and a large two-center series. J Burn Care Rehabil 2001;22:401–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blades BC, Jones C, Munster AM. Quality of life after major burns. J Trauma 1979;19:556–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andreasen NJ, Norris AS. Long-term adjustment and adaptation mechanisms in severely burned adults. J Nerv Ment Dis 1972;154:352–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan CM, Schneider JC, Kazis LE, et al. ; Multi-Center Benchmarking Study Group. Benchmarks for multidimensional recovery after burn injury in young adults: the development, validation, and testing of the American Burn Association/Shriners Hospitals for Children young adult burn outcome questionnaire. J Burn Care Res 2013;34:e121–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marino M, Soley-Bori M, Jette A, et al. Development of a conceptual framework to measure the social impact of burns. J Burn Care Res. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, Stone AA; PROMIS Cooperative Group. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Med Care 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000;320:114–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brod M, Tesler LE, Christensen TL. Qualitative research and content validity: developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual Life Res 2009;18:1263–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lasch KE, Marquis P, Vigneux M, et al. PRO development: rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Qual Life Res 2010;19:1087–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knafl K, Deatrick J, Gallo A, et al. The analysis and interpretation of cognitive interviews for instrument development. Res Nurs Health 2007;30:224–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrence JW, Fauerbach JA, Heinberg LJ, Doctor M, Thombs BD. The reliability and validity of the Perceived Stigmatization Questionnaire (PSQ) and the Social Comfort Questionnaire (SCQ) among an adult burn survivor sample. Psychol Assess 2006;18:106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawrence JW, Rosenberg L, Rimmer RB, Thombs BD, Fauerbach JA. Perceived stigmatization and social comfort: validating the constructs and their measurement among pediatric burn survivors. Rehabil Psychol 2010;55:360–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawrence JW, Heinberg L, Roca R, Munster A, Spence R, Fauerbach JA. Development and validation of the Satisfaction With Appearance Scale: assessing body image among burn-injured patients. Psychol Assess 1998;10:64–70. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiltz K Sexuality After Burn Injury. Dissertation, Maimonides University. 2006; available from http://www.esextherapy.com/dissertations/Karen%20A%20Wiltz%20Sexuality%20After%20Burn%20Injury.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J Marriage Fam 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther 2000;26:191–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology 1997;49:822–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blades B, Mellis N, Munster AM. A burn specific health scale. J Trauma 1982;22:872–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudson WW. Index of sexual satisfaction. Tallahassee, FL: WALMYR Publishing Co.; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt N, Sermat V. Measuring loneliness in different relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol 1983;44:1038–47. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cash TF, Fleming EC. The impact of body image experiences: development of the body image quality of life inventory. Int J Eat Disord 2002;31:455–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gershon RC, Lai JS, Bode R, et al. Neuro-QOL: quality of life item banks for adults with neurological disorders: item development and calibrations based upon clinical and general population testing. Qual Life Res 2012;21:475–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cella D, Nowinski C, Peterman A, et al. The neurology quality-of-life measurement initiative. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92(10 Suppl):S28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol 1996;70:1327–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willebrand M, Kildal M, Ekselius L, Gerdin B, Andersson G. Development of the coping with burns questionnaire. Pers Indiv Differ 2001;30:1059–72. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilhelm K, Parker G. The development of a measure of intimate bonds. Psychol Med 1988;18:225–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Descutner CJ, Thelen MH. Development and validation of a fear-of-intimacy scale. Psychol Assess 1991;3:218. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gershon R, Rothrock NE, Hanrahan RT, Jansky LJ, Harniss M, Riley W. The development of a clinical outcomes survey research application: assessment Center. Qual Life Res 2010;19:677–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jansky LJ, Huang JC. A mlti-method approach to assess us-ability and acceptability: a case study of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement System (PROMIS) workshop. Soc Sci Comput Rev 2009;27:262–70. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt N, Sermat V. Measuring loneliness in different relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol 1983;44:1038–47. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lumenta DB, Kamolz LP, Frey M. Adult burn patients with more than 60% TBSA involved-Meek and other techniques to overcome restricted skin harvest availability—the Viennese Concept. J Burn Care Res 2009;30:231–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans DR, Levy LM, Pilgrim AE, Potts SM, Albert WG. The Community Alcohol Use Scale: a scale for use in prevention programs. Am J Community Psychol 1985;13:715–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lord FM. Applications of item response theory to practical testing problems. New York, NY: Routledge; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hambleton R, Pitoniak MJ, Pashler H, editors. Testing and measurement. Advances in item response theory and selected testing practices. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norris JM. Computer-adaptive testing: a primer. Lang Learn Tech 2001;5:23–7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wright BD, Masters G. Rating scale analysis [Internet]. Chicago: Mesa Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warm T Weighted likelihood estimation of ability in item response theory. Psychometrika 1989;54:427–50. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang S, Wang T. Precision of warm’s weighted likelihood estimates for a polytomous model in computerized adaptive testing. Appl Psychol Meas 2001;25:317–31. [Google Scholar]