Abstract

Objective:

To study how demographic differences impact disease manifestation of sarcoidosis using the WASOG tool in a large multicentric study.

Methods:

Clinical data regarding 1445 patients with sarcoidosis from 14 clinical sites in 10 countries were prospectively reviewed from Feb 1, 2020 to Sep 30, 2020. Organ involvement was evaluated for the whole group and for subgroups differentiated by sex, race, and age.

Results:

The median age of the patients at diagnosis was 46 years old; 60.8% of the patients were female. The most commonly involved organ was lung (96%), followed by skin (24%) and eye (22%). Black patients had more multiple organ involvement than White patients (OR=3.227, 95% CI: 2.243–4.643) and females had more multiple organ involvement than males (OR=1.238, 95% CI: 1.083–1.415). Black patients had more frequent involvement of neurologic, skin, eye, extra thoracic lymph node, liver and spleen than White and Asian patients. Women were more likely to have eye (OR=1.522, 95%CI: 1.259–1.838) or skin involvement (OR=1.369, 95%CI: 1.152–1.628). Men were more likely to have cardiac involvement (OR=1.326, 95%CI: 1.096–1.605). A total of 262 (18.1%) patients did not receive systemic treatment for sarcoidosis. Therapy was more common in Black patients than in other races.

Conclusion:

The initial presentation and treatment of sarcoidosis was related to sex, race, and age. Black and female individuals are found to have multiple organ involvement more frequently. Age at diagnosis<45, Black patients and multiple organ involvement were independent predictors of treatment.

Keywords: Sarcoidosis, demographic disparities, organ involvement, clinical manifestation

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology characterized by the formation of non-caseating epithelioid cell granulomas[1]. Although its etiology remains unknown, sarcoidosis is believed to represent a genetically primed abnormal immune response to an antigenic exposure[2]. The epidemiology, clinical manifestation and outcomes of the disease vary by race and ethnicity[3]. In the United States, different clinical phenotypes were found between Black and White patients. Studies have demonstrated that the disease is more common in Black females and the disease severity is worse in Black patients compared to Whites[4–6].

Sarcoidosis commonly affects the lungs and other organs including the eyes, skin, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes. In 1999 a sarcoidosis specific instrument was developed to standardize the disease phenotypes in newly diagnosed US sarcoidosis patients based on race, sex, and age in the “A Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis (ACCESS)” multicenter study[7]. In 2014, the ACCESS disease manifestation instrument was updated by a taskforce of the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous diseases (WASOG)[8]. Prior studies have reported differences in phenotypes of sarcoidosis around the world[9, 10]. However, these earlier studies neither used standard criteria for determining organ involvement nor discussed therapy. In this study, using the new WASOG sarcoidosis assessment tool, we compared the disease manifestations from 14 sites around the world to determine how demographic differences may impact disease manifestation and whether race, gender, or age influenced the phenotypes.

Methods

Data sources

Patients with sarcoidosis were enrolled from 14 sites in 10 countries of the world. Each site was suggested to enter 100 consecutive patients of a single racial group from pulmonary clinics with an interest in sarcoidosis. One center (University of Cincinnati) entered 100 consecutive Black patients and 100 consecutive White patients. The medical records were prospectively reviewed during the seven month period from Feb 1, 2020 to Sep 30, 2020. Sarcoidosis was diagnosed based on the presence of clinical symptoms, radiological features compatible with sarcoidosis, and biopsy evidence of noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas with other known causes of granulomatosis excluded. The investigator recorded age, race, sex, organ involvement, and current and past therapy. Information for each patient was entered into a research electronic data capture system central database (REDCap)[11].

Race identification

Race was self-reported by every patient. Further analysis was performed for the racial subgroups. Considering Japanese have different clinical phenotypes from other Asian patients (more eye disease and cardiac disease), we divided race into four groups: Blacks (African Americans), Whites (Caucasians), Asians and Japanese.

Criteria for organ involvement

Organ involvement were determined for each patient at the time of enrolment using the revised WASOG instrument described in 2014[8]. The clinical manifestation for a specific organ system was categorized as: a) highly probable, b) probable, or c) possible. Highly probable lesions were defined when the likelihood of sarcoidosis causing this manifestation was at least 90%; whereas probable lesions had a likelihood between 50% and 90%. Possible lesions included those in which the likelihood of sarcoidosis causing this manifestation was <50%. Specific sarcoidosis organ involvement was defined as biopsy confirmation of granulomas or either“ highly probable” or “probable” disease category. Fifteen distinct organs or disease manifestations were compared in sarcoidosis patients: lung, central nervous system (CNS), heart, skin, eye, liver, extra thoracic node, renal, spleen, bone/joint, bone marrow, parotid/salivary, calcium metabolism, muscle, and ear nose and throat (ENT). In addition, presence of small fiber neuropathy, Lofgren’s syndrome, and pulmonary hypertension was also noted.

Statistics

Comparisons of disease manifestations and treatment in different groups were analyzed by χ2 test and corrected for continuity using Fisher’s exact test if needed. All P values were corrected (Pc) for the number of disease manifestations according to Bonferroni’s correction factor. Independent predicting factors were studied using binary logistic regression analysis with forward selection. The strength of association was expressed by odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0 package software with P value of <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 1445 patients with sarcoidosis were enrolled in the study. Patients were excluded from the study if they did not match the mentioned diagnostic criteria. Patients were enrolled from 14 sites in 10 countries (Table 1), with a third from the United States sites. Of the 1445 patients, the female to male ratio was 1.55. The median age at diagnosis was 46 years old and ranged from 13 to 85 years old. The age at diagnosis of all patients is shown in Figure 1. A larger percentage of women than men were diagnosed with sarcoidosis at 45 years of age or older, whereas men were diagnosed more frequently than woman at below 45 years (OR=1.724, 95% CI: 1.511–1.967). In the US patients, there were 276 White patients, 220 Black patients and one Asian patient. 65.9% of US Black patients were diagnosed below age 45 while only 37.1% US White patients were diagnosed below age 45 (OR=1.993, 95% CI: 1.558–2.398).

Table 1.

Demographics of Sarcoidosis Patients from 14 Sites

| Continent | Sites | Country | Number | Female/Male | Age (median,range) | Race (Black/White/Asian/Japanese |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | Cincinnati | US | 200 | 137/63 | 44 (18–72) | 100/100/0/0 |

| Albany | US | 100 | 47/53 | 45 (21–74) | 20/79/1/0 | |

| Greenville | US | 100 | 60/40 | 38 (13–63) | 100/0/0/0 | |

| Iowa | US | 97 | 53/44 | 53 (22–79) | 0/97/0/0 | |

| Toronto | Canada | 101 | 44/57 | 47 (18–78) | 19/71/11/0 | |

| South America | São Paulo | Brazil | 100 | 70/30 | 50 (23–75) | 52/48/0/0 |

| Asia | Shanghai | China | 100 | 77/23 | 52 (20–68) | 0/0/100/0 |

| Kyoto | Japan | 100 | 64/36 | 49 (22–77) | 0/0/0/100 | |

| Tochigi | Japan | 100 | 74/26 | 51 (21–75) | 0/0/0/100 | |

| Nodia | India | 107 | 56/51 | 44 (25–78) | 0/0/107/0 | |

| Europe | Paris | France | 100 | 52/48 | 45 (26–73) | 0/100/0/0 |

| Tatarstan | Tatarstan | 100 | 62/38 | 45.5 (22–68) | 0/100/0/0 | |

| Bucharest | Romania | 100 | 58/42 | 37 (20–75) | 0/100/0/0 | |

| Barcelona | Spain | 40 | 24/16 | 47 (16–85) | 3/33/1/0 | |

| / | Total | / | 1445 | 878/567 | 46 (13–85) | 294/731/220/200 |

Figure 1.

Distribution of patients with sarcoidosis by age at diagnosis and sex. The percentage of male and female patients are shown separately.

Organ involvement was classified by the proposed assessment system and is displayed in Table 2. There were 390 (27%) patients with single organ involvement, with 368 having disease limited to the lung, and 22 having disease limited to extra pulmonary organs (skin, 8; heart, 4; CNS, 3; renal, 2; eye, 1; extra node, 1; bone/joint, 1; parotid/salivary gland, 1; testis, 1). The remaining patients had multiple organ involvement, with 493 (34.1%) having two organs involved, 309 (21.4%) having three organs involved, 154 (10.7%) having four organs involved, and 99 (6.8%) having five or more organs involved (one of these patients had nine organs involved). Less than five percent had Lofgren’s syndrome, small fiber neuropathy, or pulmonary hypertension. For different race and sex patients, Black patients were more likely to have multiple organ involvement than Whites (OR=1.314, 95% CI: 1.225–1.410) and females were more likely to have multiple organ involvement than men (OR=1.238, 95% CI: 1.083–1.415). Of 1445 sarcoidosis patients, 63 (4.4%) did not have lung involvement.

Table 2.

Number and Percent of Patients with Organ Involvement.

| Organ involvement | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Lung | 1382 | 96 |

| Skin | 346 | 24 |

| Eye | 319 | 22 |

| Extra thoracic node | 273 | 19 |

| Calcium metabolism | 229 | 16 |

| Spleen | 148 | 10 |

| Heart | 126 | 9 |

| Liver | 124 | 9 |

| CNS | 110 | 8 |

| Bone/Joint | 88 | 6 |

| Parotid/salivary | 46 | 3 |

| PH | 43 | 3 |

| SFN | 42 | 3 |

| Renal | 41 | 3 |

| Lofgren | 41 | 3 |

| ENT | 36 | 3 |

| Bone marrow | 33 | 2 |

| Muscle | 26 | 2 |

CNS: central nervous system; SFN: small fiber neuropathy; PH: pulmonary hypertension; ENT: ear, nose, and throat.

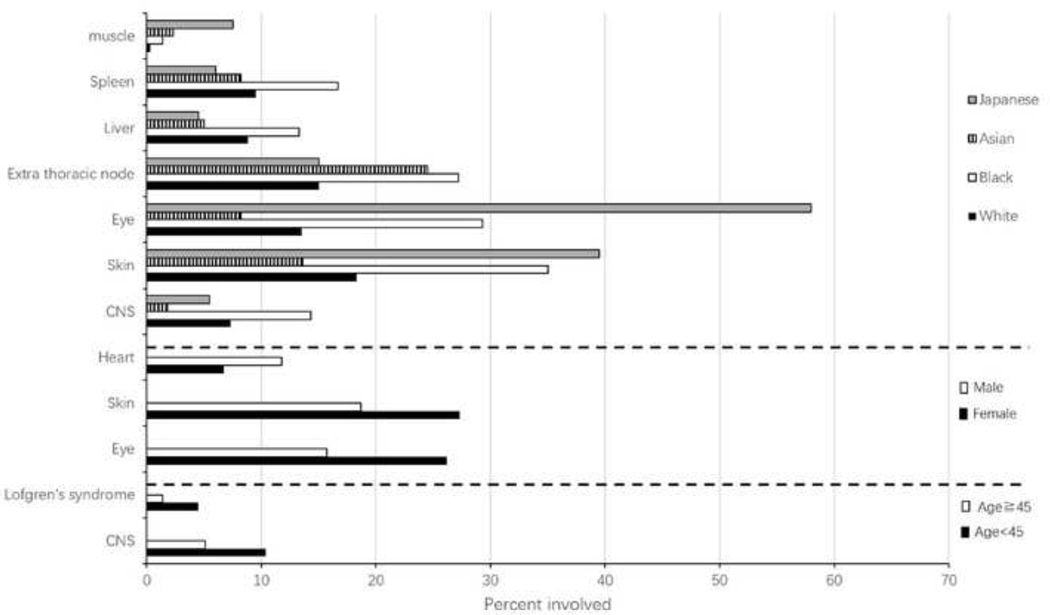

Univariate analysis comparing organ involvement versus sex, age and race are summarized in Figure 2. Japanese patients are more likely to have skin, eye, and muscle involvement (Pc<0.001). Black patients had more frequent involvement of CNS (χ2=30.433, Pc<0.001), skin (χ2=72.180, Pc<0.001), eye (χ2=215.092, Pc<0.001) and spleen (χ2=15.558, Pc<0.001) than White and Asian patients; had more extra thoracic node involvement (χ2=27.097, Pc<0.001) than Whites and had more liver involvement (χ2=16.190, Pc=0.018) than Asian patients. Women were more likely to have eye (OR=1.522, 95%CI: 1.259–1.838) or skin involvement (OR=1.369, 95%CI: 1.152–1.628) than men. Men were more likely to have heart involvement (OR=1.326, 95%CI: 1.096–1.605) than women. Comparison of patients by age at time of diagnosis revealed that those under 45 years of age were more likely to have involvement of CNS (OR=1.512, 95%CI: 1.176–1.944) and have Lofgren’s syndrome (OR=2.045, 95%CI: 1.231–3.397).

Figure 2.

Comparison of organ involvement which was significant difference between groups on basis of race, sex or age.

Among different continents, North American patients were more likely to have CNS (χ2=26.925, Pc<0.001) and heart involvement (χ2=44.256, Pc<0.001) than European and Asian patients. Abnormal calcium metabolism was more common in South American and Asian patients (χ2= 30.347, Pc<0.001), whereas Skin involvement (χ2= 39.659, Pc<0.001) was more common in South American patients and eye involvement (χ2= 66.861, Pc<0.001) was more common in Asian patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of organ involvement which was significant difference among continents.

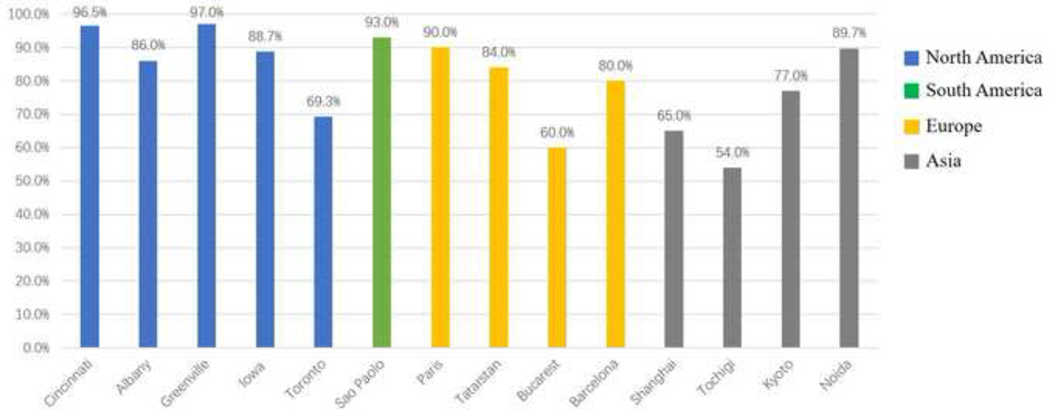

Nearly twenty percent of patients never received systemic treatment for their sarcoidosis. Table 3 presents all previous and current anti-inflammatory therapy for the remaining 1183 patients at the time of our analysis. Over time, systemic therapy had either never been prescribed or was discontinued in 588 (40.7%) patients. Figure 4 compared the rate of treatment at visit per site (Figure 4A), race and continents (Figure 4B). The percentage of Black patients receiving treatment at study visit was higher than that of other races (χ2= 26.295, P<0.001). Figure 5 compared the rate of current or past treatment per site (Figure 5A), race and continents (Figure 5B). Only 4.1% of Black patients had never been treated, while 34.5% of Japanese patients never received treatment (χ2= 77.094, P<0.001). In the patients with CNS involvement, the percent on therapy at visit was higher than those without CNS involvement (75.5% versus58.0%, OR=2.109, 95%CI: 1.384–3.214). Other organ involvement in which treatment was more common than non-treatment included heart (78.6% versus 57.5%, OR=2.516, 95%CI: 1.666–3.8), and skin (67.9% versus 56.6%, OR=1.453, 95%CI: 1.189–1.774). The more the number of organs involved, the higher the percentage of systemic treatment. In this study, the percentage of systemic treatment at visit in patients with one organ involvement, two organs involvement and greater than or equal to 3 organs involvement were 46.4%, 55.2% and 71.8% respectively. A binary logistic regression analysis with forward selection was performed on factors including gender, age, race, organ involvement and geographic location. There were three independent predictors of treatment: age at diagnosis <45 (OR,1.531; 95%CI, 1.131–2.072), Black patients (OR,2.327; 95%CI, 1.476–3.668) and multiple organ involvement (OR,2.261; 95%CI, 1.670–3.061).

Table 3.

Systemic Treatment of sarcoidosis patients.

| Drug | Total No. treated (%) | Current (%) | Past (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prednisone | 1022 (71) | 548 (38) | 661 (46) |

| Methotrexate | 488 (34) | 246 (17) | 279 (19) |

| Azathioprine | 142 (10) | 45 (3) | 98 (7) |

| Mycophenolate | 44 (3) | 27 (2) | 16 (1) |

| Leflunomide | 59 (4) | 18 (1) | 42 (3) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 209 (15) | 99 (7) | 122 (8) |

| Infliximab | 103 (7) | 59 (4) | 44 (3) |

| Adalimumab | 26 (2) | 15 (1) | 11 (1) |

| Rituximab | 26 (2) | 22 (2) | 4 (0) |

| Repository corticotropin injection | 26 (2) | 10 (1) | 16 (1) |

Figure 4A.

Percent treated at visit versus site.

Figure 4B.

Percent treated at visit versus race and continents.

Figure 5A.

Percent treated (current or past) versus site.

Figure 5B.

Percent treated (current or past) versus race and continents.

Prednisone was the most commonly prescribed drug. Treatment often consisted of combination of prednisone and immunosuppressive drug, which may be cytotoxic or biologic (Figure 6). Univariate analysis was done, comparing current or past treatment versus sex, age and race. The significant differences between groups were summarized in Table 4. Prednisone and hydroxychloroquine were more commonly used in those under 45 years of age. Rituximab was more commonly used in female patients. Twenty-four of the 26 patients receiving rituximab were treated in Cincinnati. For Black patients, therapy was more common with prednisone, methotrexate, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, infliximab and repository corticotropin injection.

Figure 6.

Therapy could include one drug or a combination. Drugs prescribed included cytotoxics (methotrexate, azathioprine, leflunomide, mycophenolate or Hydroxychloroquine), biologics (infliximab, Adalimumab or rituximab) and repository corticotropin injection.

Table 4.

Current or Past Treatment by sex, age and race.

| No. (current or past) | χ2 (Female/Male) | χ2 (Female/Male) | Pc | (Age<45/ Age≧45) | χ2 (Age<45/ Age≧45) | Pc | (Black/White/Asian/Japanese) | χ2 (Black/White/Asian/Japanese) | Pc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prednisone | 1022 | 616/406 | 0.348 | NS | 494/528 | 9.029 | 0.03 | 271/496/156/99 | 111.782 | <0.001 |

| Methotrexate | 488 | 290/198 | 0.551 | NS | 232/256 | 0.953 | NS | 156/251/32/49 | 93.060 | <0.001 |

| Azathioprine | 142 | 86/56 | 0.003 | NS | 73/69 | 2.141 | NS | 60/76/3/3 | 70.847 | <0.001 |

| Mycophenol ate | 44 | 25/19 | 0.296 | NS | 16/28 | 1.676 | NS | 10/29/4/1 | 7.774 | NS |

| Leflunomide | 59 | 38/21 | 0.343 | NS | 33/26 | 2.473 | NS | 17/42/0/0 | 25.205 | <0.001 |

| Hydroxychlo roquine | 209 | 132/77 | 0.589 | NS | 125/84 | 18.931 | <0.001 | 63/113/33/0 | 45.982 | <0.001 |

| Infliximab | 103 | 69/34 | 1.805 | NS | 57/46 | 3.946 | NS | 45/54/4/0 | 54.497 | <0.001 |

| Adalimumab | 26 | 17/9 | 0.237 | NS | 9/17 | 1.367 | NS | 6/19/1/0 | 8.660 | NS |

| Rituximab | 26 | 23/3 | 8.521 | 0.04 | 13/13 | 0.176 | NS | 10/16/0/0 | 12.594 | NS |

| Repository corticotropin injection | 26 | 21/5 | 4.446 | NS | 16/10 | 2.594 | NS | 12/14/0/0 | 16.418 | 0.009 |

Pc: P values were corrected multiple testing of treatment according to Bonferroni’s correction.

Discussion

This study provides the updated data on the clinical phenotypes and characteristics of sarcoidosis in an international multicenter cohort. Sarcoidosis affects individuals of all age, sex, race or ethnicity. Epidemiologists have reported sarcoidosis was more common in patients over 30 years old in US[4]. Another study in Sweden showed that the incidence peaked in males aged 30–50 years and in females aged 50–60 years[12]. Our results showed that women with sarcoidosis were generally older than men when diagnosed, consistent with the previous studies. In the current study, the median age of diagnosis was 46 years for all enrolled patients with the peak ages of 50 to 54 years for female patients versus 35 to 39 years for male patients. For the incidence rate of sarcoidosis in elderly patients, there was a report found that 27.8% of the sarcoidosis patients were over 65 years old[13]. In this study, about six percent were diagnosed at age 65 or older. Although the incidence rate of elderly patients is lower than that reported previously, recognition that the onset age of female is older than that of male and sarcoidosis is not rare in older patients has important clinical significance.

We found the female to male ratio was 1.55, it was consistent with the common opinion that sarcoidosis incidence and prevalence appeared higher in women around the world[13, 14]. Gender could also affect clinical symptoms and organ involvement of sarcoidosis. Women accounted for about 65–77% of the patients with eye involvement in previous reports[15, 16]. In this study, the majority of the patients with sarcoid eye involvement were female (72.1%) which is consistent with previous study that found male sex was a protective factor against development of uveitis[17]. The skin was the most common nonthoracic organ involved, and was observed in nearly one-half of patients with extrapulmonary sarcoidosis[18]. The higher prevalence of skin involvement has also been observed in other populations with different ethnic backgrounds[5, 19, 20]. In this study, skin involvement second only to the lungs, accounted for 24% of the total patients. Skin involvement was seen more frequently in women (69.4%) than in men. Our study also suggested that cardiac sarcoidosis is more common in men than women, it was similar to a study in Poland[21].

For different ethnic groups, different clinical phenotypes and organ involvement have been reported. Uveitis has been reported to be more common in Japanese sarcoidosis patients in more than 70% of cases[22]. In the current study, 36.5% of Japanese sarcoidosis patients had eye involvement, significantly more than patients of other races. ACCESS showed that Black patients tend to experience more extrapulmonary sarcoidosis with skin, eyes, bone marrow, liver and extrathoracic lymph nodes involvement, while calcium dysmetabolism was more common in White patients[4]. Also, Black races was likely to have more severe sarcoidosis at presentation and have more organs involvement[23]. Similarly, clinical data from a large cohort of sarcoidosis patients at Medical University of South Carolina showed that Black patients had more advanced radiographic stages of sarcoidosis, more organ involvement, and more frequently required anti-sarcoidosis medication compared to White patients[5]. In the current study, Black patients tended to have more organs involvement than Whites, similar to prior studies. Black patients also had more frequent involvement of CNS, skin, eye and spleen than White and Asian patients; had more extra thoracic node involvement than Whites and had more liver involvement than Asian patients.

Corticosteroids were the preferred first-line treatment in our cohort, probably because of their availability, low cost, widely understood side effects, and rapid onset to attenuate granulomatous inflammation[24–27]. Their efficacy has been shown in randomized controlled trials, particularly in pulmonary sarcoidosis[28]. Of the 1022 prednisone-treated patients in this study, only 429 (42.0%) were prescribed prednisone alone, probably because combinations of medications can enhance steroid sparing and reduce toxicity in those patients requiring prolonged treatment. Second-line therapy includes cytotoxic agents such as methotrexate, azathioprine, leflunomide, mycophenolate and hydroxychloroquine[29–31]. Methotrexate is the only second-line therapy studied in a randomized controlled trial[29]. MTX is the preferred second-line treatment in sarcoidosis due to wide experience with low toxicity[30, 32, 33]. In 1995, Lower et al showed a benefit with MTX therapy both in symptomatic pulmonary and extra-pulmonary sarcoidosis: 66% of the treated patients (33/50) experienced disease improvement[34]. In this study, a third of patients received MTX therapy. Biologics and other agents are third-line therapy. TNF inhibitors (infliximab and adalimumab) have been shown to be particularly effective for advanced disease[35, 36]. New therapies, including repository corticotropin injection and rituximab, have been reported as effective in some cases[37]. Therapy with prednisone, methotrexate, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, infliximab, or repository corticotropin injection was more common with Black patients in this study. This may be related to more organ involvement and severe manifestation in Blacks.

Not all sarcoidosis patients required a systemic treatment[27]. In this study, nearly twenty percent of patients were never prescribed systemic medication for their sarcoidosis. At time of enrollment in study, 40% of patients were not receiving any treatment for their sarcoidosis. Black patients were more likely to be treated with systemic medication than other races, which may be related to more severe manifestation in Blacks. The need for anti-sarcoidosis therapy was more common in patients with life-threatening organ involvement such as CNS and heart, and in patients with more organ involvement.

There were some limitations to this study. This is not a rigorous epidemiologic study and the race categorization of patients was self-reported, so there may have been selection biases concerning our cohort. Therefore, these results may not accurately reflect the world-wide state of sarcoidosis. Despite recruiting consecutive patients, differences in recruitment across 14 sites in 10 countries may have introduced bias which exaggerated or diminished differences in organ involvement and treatment strategies between racial and geographic groups.

In conclusion, sarcoidosis is a multifaceted disease. In this study, organ involvement and treatment differed according to race, sex, and age. The major determinant appeared to be race, other than regional differences. This variability must be considered in both etiologic and therapeutic studies.

Highlights:.

It is an international study with large cohort of patients with sarcoidosis.

Organ involvement and treatment differed according to race, sex, and age.

Black and female individuals were more likely to have multiple organ involvement.

Age at diagnosis<45, Black patients and multiple organ involvement were independent predictors of treatment.

Acknowledgement:

Ying Zhou’s work has been supported by National Science Foundation of Shanghai, China (No.18ZR1431400), Science and Technology Innovation Research Project of Shanghai Science and Technology Commission, China (No. 20Y11902700), and Clinical Research Plan of SHDC (No. SHDC20CR40011C).

Jacobo Sellares work has been financed with the grant SLT008/18/00176 and the support of the Department of Health of the Generalitat de Catalunya, in the call for grants 2019–2021, under a competitive regime, for the financing of different programs and instrumental actions included in the Strategic Research and Innovation Plan in Health 2016–2020. It has also been financed by FEDER Funds (PI19/01152), SEPAR, SOCAP, FUCAP and Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS).

Footnotes

Credit Author Statement

Ying Zhou: Project administration, enrolling patients, data acquisition and analysis, writing the manuscript.

Alicia K. Gerke, Elyse E. Lower, Ogugua Ndili Obi, Marc A. Judson, and Florence Jeny: Enrolling patients, data acquisition and revising the manuscript.

Robert P. Baughman: Project design and administration, enrolling patients, data acquisition and revising the manuscript.

Othe authors: Enrolling patients and data acquisition.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest to this work.

We declare that we do not have any commercial or associative interest that represents a conflict of interest in connection with the work submitted.

References:

- [1].Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 1999. 160(2): p. 736–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Valeyre D, et al. , Sarcoidosis. Lancet, 2014. 383(9923): p. 1155–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Westney GE and Judson MA, Racial and ethnic disparities in sarcoidosis: from genetics to socioeconomics. Clin Chest Med, 2006. 27(3): p. 453–62, vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Baughman RP, et al. , Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2001. 164(10 Pt 1): p. 1885–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Judson MA, Boan AD and Lackland DT, The clinical course of sarcoidosis: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment in a large white and black cohort in the United States. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis, 2012. 29(2): p. 119–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cozier YC, et al. , Sarcoidosis in black women in the United States: data from the Black Women’s Health Study. Chest, 2011. 139(1): p. 144–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Judson MA, et al. , Defining organ involvement in sarcoidosis: the ACCESS proposed instrument. ACCESS Research Group. A Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis, 1999. 16(1): p. 75–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Judson MA, et al. , The WASOG Sarcoidosis Organ Assessment Instrument: An update of a previous clinical tool. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis, 2014. 31(1): p. 19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Izumi T, Symposium: Population differences in clinical features and prognosis of sarcoidosis throughout the world. Sarcoidosis, 1992(9:S105––S118). [Google Scholar]

- [10].Siltzbach LE, et al. , Course and prognosis of sarcoidosis around the world. Am J Med, 1974. 57(6): p. 847–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Harris PA, et al. , Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform, 2009. 42(2): p. 377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Arkema EV, et al. , Sarcoidosis incidence and prevalence: a nationwide register-based assessment in Sweden. Eur Respir J, 2016. 48(6): p. 1690–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Baughman RP, et al. , Sarcoidosis in America. Analysis Based on Health Care Use. Ann Am Thorac Soc, 2016. 13(8): p. 1244–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kowalska M, Niewiadomska E. and Zejda JE, Epidemiology of sarcoidosis recorded in 2006–2010 in the Silesian voivodeship on the basis of routine medical reporting. Ann Agric Environ Med, 2014. 21(1): p. 55–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ungprasert P, et al. , Clinical Characteristics of Ocular Sarcoidosis: A Population-Based Study 1976–2013. Ocul Immunol Inflamm, 2019. 27(3): p. 389–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ying Z, et al. , Clinical characteristics of sarcoidosis patients in the United States versus China. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis, 2017. 34(3): p. 209–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Birnbaum AD, et al. , Sarcoidosis in the national veteran population: association of ocular inflammation and mortality. Ophthalmology, 2015. 122(5): p. 934–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].James WE, et al. , Clinical Features of Extrapulmonary Sarcoidosis Without Lung Involvement. Chest, 2018. 154(2): p. 349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Morimoto T, et al. , Epidemiology of sarcoidosis in Japan. Eur Respir J, 2008. 31(2): p. 372–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yanardag H, Pamuk ON and Karayel T, Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: analysis of the features in 170 patients. Respir Med, 2003. 97(8): p. 978–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Martusewicz-Boros MM, et al. , Cardiac Sarcoidosis: Is it More Common in Men? Lung, 2016. 194(1): p. 61–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Baughman RP, Lower EE and Kaufman AH, Ocular sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med, 2010. 31(4): p. 452–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rabin DL, et al. , Sarcoidosis: social predictors of severity at presentation. Eur Respir J, 2004. 24(4): p. 601–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Judson MA, An approach to the treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis with corticosteroids: the six phases of treatment. Chest, 1999. 115(4): p. 1158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sharma OP, Pulmonary sarcoidosis and corticosteroids. Am Rev Respir Dis, 1993. 147(6 Pt 1): p. 1598–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Baughman RP, et al. , Presenting characteristics as predictors of duration of treatment in sarcoidosis. QJM, 2006. 99(5): p. 307–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rahaghi FF, et al. , Delphi consensus recommendations for a treatment algorithm in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir Rev, 2020. 29(155). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Paramothayan NS, Lasserson TJ and Jones PW, Corticosteroids for pulmonary sarcoidosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2005(2): p. CD001114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Baughman RP, Winget DB and Lower EE, Methotrexate is steroid sparing in acute sarcoidosis: results of a double blind, randomized trial. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis, 2000. 17(1): p. 60–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Vorselaars A, et al. , Methotrexate vs azathioprine in second-line therapy of sarcoidosis. Chest, 2013. 144(3): p. 805–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Majithia V, et al. , Successful treatment of sarcoidosis with leflunomide. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2003. 42(5): p. 700–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Cremers JP, et al. , Multinational evidence-based World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders recommendations for the use of methotrexate in sarcoidosis: integrating systematic literature research and expert opinion of sarcoidologists worldwide. Curr Opin Pulm Med, 2013. 19(5): p. 545–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Baughman R, Cremers JP and Harmon M, Methotrexate in sarcoidosis: hematologic and hepatic toxicity encountered in a large cohort over a six year period. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis, 2020(37(3):c2020001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lower EE and Baughman RP, Prolonged use of methotrexate for sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med, 1995. 155(8): p. 846–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Judson MA, et al. , Efficacy of infliximab in extrapulmonary sarcoidosis: results from a randomised trial. Eur Respir J, 2008. 31(6): p. 1189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kamphuis LS, et al. , Efficacy of adalimumab in chronically active and symptomatic patients with sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2011. 184(10): p. 1214–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Baughman RP, et al. , Repository corticotropin for Chronic Pulmonary Sarcoidosis. Lung, 2017. 195(3): p. 313–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]