Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the study was to explore non-HIV-related health care service (NHRHS) utilization, demographic, clinical and laboratory factors associated with timely initial “retention” in HIV care among individuals “linked” to HIV care in British Columbia (BC), Canada.

Methods

We conducted a Weibull time-to-initial-retention analysis among BC Seek and Treat for Optimal Prevention of HIV/AIDS (STOP HIV/AIDS) cohort participants linked in 2000–2010, who had ≥ 1 year of follow-up. We defined “linked” as the first HIV-related service accessed following HIV diagnosis and “retained” as having, within a calendar year, either: (i) at least two HIV-related physician visits/diagnostic tests or (ii) at least two antiretroviral therapy (ART) dispensations, ≥ 3 months apart. Individuals were followed until they were retained, died, their last contact date, or until 31 December 2011, whichever occurred first.

Results

Of 5231 linked individuals (78% male; median age 39: (Q1–Q3: 32–46) years], 4691 (90%) were retained [median time to initial retention of 9 (Q1–Q3: 5–13) months] by the end of follow-up and 540 (10%) were not. Eighty-four per cent of not retained and 96% of retained individuals used at least one type of NHRHS during follow-up. Individuals who saw a specialist for NHRHS during follow-up had a shorter time to initial retention than those who did not [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 2.79; 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.47–3.16]. However, those who saw a general practitioner (GP) for NHRHS (aHR 0.79; 95% CI: 0.74–0.84) and those admitted to the hospital for NHRHS (aHR 0.60; 95% CI: 0.54–0.67), versus those who did/were not, respectively, had longer times to initial retention, as did female patients, people who inject drugs (PWID) and individuals < 40 years old.

Conclusions

Overall, 84% of not retained individuals used some type of NHRHS during follow-up. Given that 71% of not retained individuals used GP NHRHS, our results suggest that GP-targeted interventions may be effective in improving time to initial retention.

Keywords: HIV, missed opportunities, non-HIV-related health care service utilization, retention in HIV care, retention, time to retention

Introduction

Retaining HIV-diagnosed individuals in HIV care is crucial for optimizing HIV-related health outcomes. Studies have shown that individuals retained in HIV care are more likely to initiate antiretroviral therapy (ART) in a timely fashion [1], have higher CD4 cell counts [2–5], and have increased survival rates [3,6,7]. They also have a decreased likelihood of developing HIV-related opportunistic infections [8], being hospitalized [9–11], having high viral loads [2], and developing ART resistance [2,3,12].

Furthermore, the importance of retaining individuals in care is emphasized in the context of treatment as prevention (TasP). [TasP refers to the timely and sustained use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) to simultaneously virtually eliminate the risk of disease progression to AIDS and premature death, as well as HIV transmission [13–21].] This idea is demonstrated by the results of a mathematical model, which estimated the proportion of HIV transmissions occurring at each stage of the HIV care cascade [22]. The authors estimated that individuals who were diagnosed but not retained in HIV care accounted for the greatest proportion of transmissions in the USA in 2009, 61%, as well as the second highest transmission rate, 5.3 per 100 person-years, following HIV-infected but undiagnosed individuals. These findings further highlight the importance of understanding factors associated with timely retention in HIV care (referred to as “retention” hereafter), and the need to uncover opportunities for engagement in HIV care, both of which are crucial for constructing targeted retention interventions.

Unfortunately, achieving adequate retention remains an ongoing challenge. A recent longitudinal analysis of the HIV cascade of care, from 1996 to 2011, in British Columbia (BC) found that, consistently, the greatest cascade attrition occurred between the stages “linked to HIV care” and “retained in HIV care” [23]. However, there was a gap in understanding why this was the case, as BC is a Canadian province with universal free access to ART, laboratory monitoring and care, as well as a well-established TasP programme [24]. Thus, we sought to determine factors associated with delayed time to initial retention among the HIV-positive population in BC. Specifically, we were interested in exploring whether individuals not retained in HIV care (referred to as “retained” hereafter) continued to seek out non-HIV-related health care and how non-HIV-related health care utilization was associated with the time to initial retention.

Methods

Study data

Data used in this analysis came from the BC STOP HIV/AIDS database, which has been described in detail elsewhere [25,26]. Briefly, the database is derived from a series of linked provincial data sets. These include: (i) a data set from The BC Centre for Disease Control, which is the provincial agency that centralizes all HIV testing data and new HIV diagnoses from the BC Public Health Microbiology and Reference Laboratory (which performs all confirmatory testing in BC); HIV reporting (nonnominal and nominal) became mandatory in BC in 2003; (ii) a data set from The BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, which has a centralized system which captures all antiretroviral distribution, all plasma viral load testing (pVL), all resistance testing, and approximately 85% of CD4 cell count measurements in BC; (iii) The Medical Services Plan (MSP) physician billing database, which captures non-HIV-related and HIV-related physician services; (iv) the provincial Discharge Abstract Database (DAD), which records all hospitalizations in BC, and (v) The BC Pharma Net database, which captures non-ART-related drug dispensations.

Eligibility

This analysis was restricted to HIV-positive individuals who were linked to HIV care (referred to as “linked” hereafter) between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2010 and had at least one calendar year of follow-up. Individuals were followed until they were retained. Individuals who were never retained were followed until death, their last contact date or 31 December 2011, whichever occurred first.

Outcome variable

We undertook the present analysis to assess the time to initial retention among linked individuals. We defined linked and retained using previously defined and validated definitions [23]: “linked”: the first instance of an HIV-related service (i.e. having a pVL measurement, a CD4 cell count, an HIV-related physician visit, or having ART dispensed): (i) after the HIV diagnosis for individuals with a confirmed HIV test or (ii) ≥ 30 days after the derived HIV diagnosis date for individuals without a confirmed HIV test. “Retained”: among linked individuals, having at least two HIV-related physician visits or diagnostic tests (CD4 or pVL) or ART drug dispensations, ≥ 3 months apart within a calendar year. As retention is defined by two retention events/dates, the retained date for this analysis was defined as the first retention event date.

Explanatory variables

Of primary interest was exploring the use of non-HIV-related health care services stratified by retention status. To achieve this, we used five non-HIV-related health care utilization variables, measured from the time of linkage to the end of study follow-up: (1) non-HIV-related MSP services provided by a general practitioner (GP), (2) non-HIV-related MSP services provided by a specialist, (3) non-HIV-related laboratory work, (4) non-HIV-related DAD hospital admissions, and (5) non-HIV-related Pharma Net prescription dispensations. Given the high correlation between non-HIV-related health care services (for example, in BC, to see a specialist one requires a referral from a GP), we assigned a value of 1 if an individual accessed a specific non-HIV-related health care service and 0 otherwise. Thus, if an individual saw a GP for non-HIV-related reasons, regardless of any other type of non-HIV-related health care service used, that individual would be classified as “1” for seeing a GP for non-HIV-related reasons. After creating our binary non-HIV-related health care service utilization variables, we tested them for correlation and found that the variable non-HIV-related laboratory work was highly correlated with non-HIV-related MSP services provided by a specialist (Spearman’s correlation coefficient = 0.98). Thus, we only included the variable “non-HIV-related MSP services provided by a specialist” in our final Weibull model and in the creation of the variable “number of types of non-HIV-related health care services”, which is the number of different types of non-HIV-related health care services used by an individual, categorized as zero, one, two, three and four.

We also considered the following baseline covariates (i.e. characteristics measured during the linkage year): sex; history of testing hepatitis C virus antibody positive (hepatitis C); AIDS diagnosis; HIV risk group: categorized as people who inject drugs (PWID), men who have sex with men (MSM), heterosexual and other (blood transfusion, accidental puncture or perinatal exposure)/unknown (i.e. no reported HIV risk group); age; CD4 count; pVL; patient residence in an urban or nonurban area, defined by the first three digits of a patient’s postal code; and the regional health authority (HA) where the individual received HIV care (there are five regional HAs in BC: Northern, Vancouver Coastal, Vancouver Island, Fraser and Interior). In BC, HAs are administratively responsible for health care delivery within their respective regions. As our retention definition includes the use of ART and ART initiation guidelines have changed over time to recommend initiating ART at higher CD4 cell counts [27–30], we controlled for the covariate “year of diagnosis” to account for this cohort effect. We categorized cohorts as < 2000, 2000–2007, 2008–2009 and ≥ 2010.

Statistical analyses

Time to initial retention was estimated using Kaplan–Meier methods and a Weibull accelerated failure-time model [31]. For clarity, Kaplan–Meier curves are displayed up to the first 20 months, as most individuals were retained within this time period, though longer term follow-up was obtained for some individuals and was included in the Weibull model. Event-free individuals were right-censored as of 31 December 2011. Individuals included in this analysis were not followed after this date and those lost to follow-up were censored at the date of last contact.

Statistical tests for the dependence between categorical variables were performed using Fisher’s exact test or the χ2 test, while continuous variables were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The Weibull model was built in order to estimate the effects of a number of variables and their influence on initial time to retention among linked individuals. Backward stepwise selection based on Akaike information criteria (AIC) and type III P-values were used in the final model variable selection [32]. In addition, to minimize the potential of collinearity, the correlation between pairs of independent variables was calculated using the Spearman correlation test and highly correlated variables were excluded from further analysis. All analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

In total, 5231 individuals were linked between 2000 and 2010 and had at least one calendar year of follow-up. Of these, 78% were male, 19% were < 30 years old, 34% were 30–39 years old, 31% were 40–49 years old, and 17% were ≥ 50 years old. Also, 36% were PWID, 28% were MSM, 14% were heterosexual, and 22% were in the other/unknown risk group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Non-HIV-related health care utilization and baseline characteristics associated with initial retention in HIV care

| Total (n = 5231) | Not retained (n = 540) | Retained (n = 4691) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex [n (%)] | ||||

| Female | 1127 (22) | 175 (32) | 952 (20) | <0.001 |

| Male | 4104 (78) | 365 (68) | 3739 (80) | |

| Age [n (%)] | 5231 | |||

| < 30 years | 978 (19) | 113 (21) | 865 (18) | 0.023 |

| 30–39 years | 1770 (34) | 174 (32) | 1596 (34) | |

| 40–49 years | 1607 (31) | 144 (27) | 1463 (31) | |

| ≥ 50 years | 876 (17) | 109 (20) | 767 (16) | |

| Non-HIV-related MSP services provided by a general practitioner [n (%)] | ||||

| Yes | 3538 (68) | 381 (71) | 3157 (67) | 0.132 |

| No | 1693 (32) | 159 (29) | 1534 (33) | |

| Non-HIV-related MSP services provided by a specialist [n (%)] | ||||

| Yes | 4733 (90) | 381 (71) | 4352 (93) | < 0.001 |

| No | 498 (10) | 159 (29) | 339 (7) | |

| Non-HIV-related laboratory test(s) performed [n (%)] | ||||

| Yes | 4618 (88) | 336 (62) | 4282 (91) | < 0.001 |

| No | 613 (12) | 204 (38) | 409 (9) | |

| Non-HIV-related hospital admission(s) [n (%)] | ||||

| Yes | 431 (8) | 85 (16) | 346 (7) | < 0.001 |

| No | 4800 (92) | 455 (84) | 4345 (93) | |

| Non-HIV-related drug prescriptions filled [n (%)] | ||||

| Yes | 4084 (78) | 338 (63) | 3746 (80) | < 0.001 |

| No | 1147 (22) | 202 (37) | 945 (20) | |

| Number of types of non-HIV-related health care services used [n (%)] | ||||

| None | 250 (5) | 85 (16) | 165 (4) | < 0.001 |

| One | 478 (9) | 63 (12) | 415 (9) | |

| Two | 1567 (30) | 130 (24) | 1437 (31) | |

| Three | 2570 (49) | 186 (34) | 2384 (51) | |

| Four | 366 (7) | 76 (14) | 290 (6) | |

| On ART in the retention year [n (%)] | ||||

| Yes | 2160 (41) | 0 (0) | 2160 (46) | < 0.001 |

| No | 3071 (59) | 540 (100) | 2531 (54) | |

| Hepatitis C [n (%)] | ||||

| Positive | 1585 (30) | 43 (8) | 1542 (33) | < 0.001 |

| Negative | 2467 (47) | 73 (14) | 2394 (51) | |

| Unknown | 1179 (23) | 424 (79) | 755 (16) | |

| AIDS diagnosed [n (%)] | ||||

| Yes | 746 (14) | 13 (2) | 733 (16) | < 0.001 |

| No | 4485 (86) | 527 (98) | 3958 (84) | |

| HIV risk factors [n (%)] | ||||

| Heterosexual | 751 (14) | 47 (9) | 704 (15) | < 0.001 |

| PWID | 1885 (36) | 138 (26) | 1747 (37) | |

| MSM | 1452 (28) | 54 (10) | 1398 (30) | |

| Other/unknown | 1143 (22) | 301 (56) | 842 (18) | |

| Year of diagnosis [n (%)] | ||||

| < 2000 | 365 (7) | 55 (10) | 310 (7) | 0.001 |

| 2000–2007 | 3779 (72) | 359 (66) | 3420 (73) | |

| 2008–2009 | 781 (15) | 84 (16) | 697 (15) | |

| 2010 | 306 (6) | 42 (8) | 264 (6) | |

| Patient’s residing health authority [n (%)] | ||||

| Fraser | 1216 (23) | 154 (29) | 1062 (23) | < 0.001 |

| Interior | 304 (6) | 42 (8) | 262 (6) | |

| Vancouver Coastal | 2781 (53) | 212 (39) | 2569 (55) | |

| Vancouver Island | 592 (11) | 53 (10) | 539 (11) | |

| Vancouver Northern | 214 (4) | 23 (4) | 191 (4) | |

| Unknown | 124 (2) | 56 (10) | 68 (1) | |

| Patient’s residence in urban area [n (%)] | ||||

| Yes | 4629 (88) | 320 (59) | 4309 (92) | < 0.001 |

| No | 185 (4) | 5 (1) | 180 (4) | |

| Unknown | 417 (8) | 215 (40) | 202 (4) | |

| Earliest available pVL during the linkage year (log10 copies/mL) | ||||

| [median (25th–75th percentile)] | 3.70 (1.69–4.66) | 3.88 (2.16–4.82) | 3.69 (1.69–4.65) | 0.104 |

| Earliest available CD4 count (cells/μL) during the linkage year | ||||

| [median (25th–75th percentile)] | 360 (230–520) | 460 (225–600) | 360 (230–520) | 0.110 |

| Follow-up time from linkage to the end of study follow-up (months) | ||||

| [median (25th–75th percentile)] | 48 (27–85) | 8 (5–12) | < 0.001 | |

All variables in the table were measured during the year an individual was linked to HIV care except for non-HIV-related care service variables. These variables were measured from the time of linkage to the end of study follow-up. ART, antiretroviral therapy; Hepatitis C, history of testing antibody positive for hepatitis C virus; MSM, men who have sex with men; PWID, people with a history of injecting drug use; other/unknown, other (blood transfusion, accidental puncture or perinatal exposure)/unknown (i.e. no reported HIV risk group); MSP, Medical Services Plan; ART, antiretroviral therapy; pVL, plasma viral load.

Overall, 90% (n = 4691) of the study population were retained during study follow-up and had a median time to initial retention of 9 [25th–75th percentile (Q1–Q3): 5–13] months (Table 1). Thirty per cent and 70% of the study population were retained 6 and 12 months after being linked, respectively. Of retained individuals, 46% were on ART in the year they were considered retained. The remaining 10% (540) of the study population were never retained and had a median study follow-up time of 48 (Q1–Q3 27–85) months. Bivariable analysis results showed that being male, having an AIDS diagnosis, having a known risk factor, being HIV-diagnosed between 2000 and 2007, being on ART, residing in the Vancouver Coastal HA and Vancouver Island HA, and living in an urban area were associated with being retained. All of these variables were included in our final Weibull model except for “patient residence in an urban area”, as only five individuals were both not retained and did not reside in an urban area. We also did not include the variables “hepatitis C”, as this was highly collinear with PWID, and “year of diagnosis”, as this was highly negatively correlated with “follow-up time”. Finally, we did not include “on ART”, as this was a part of our retention definition.

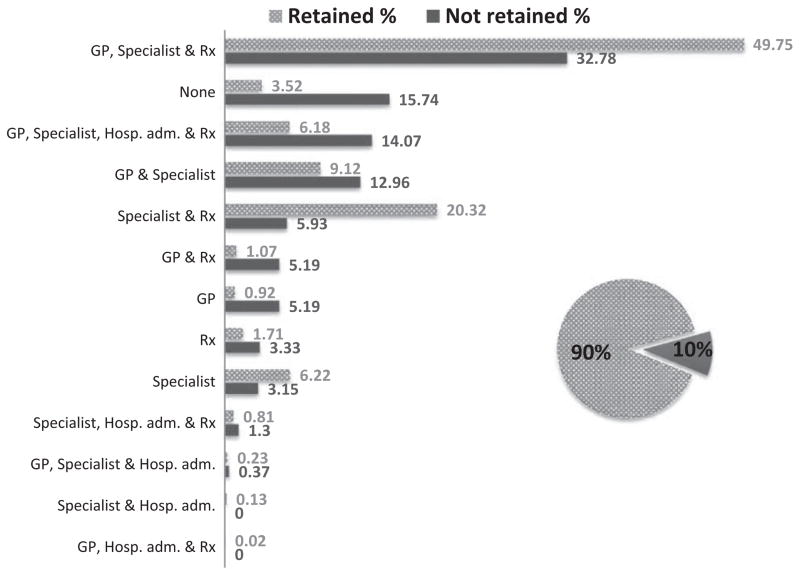

Non-HIV-related health care use and retention in care status

Use of non-HIV-related services in the study population was high, with approximately 84% (455) of not retained and 96% (4526) of retained individuals using some type of non-HIV-related health care service during study follow-up. All five of the “non-HIV-related health care utilization” variables and the “number of different types of non-HIV-related health care services used” variable were associated with being retained (Table 1). Figure 1 shows the distribution of those retained (patterned bar) and the distribution of those not retained (solid bar), by the types of non-HIV-related service utilization variables (Table 2). The top three non-HIV-related service combinations used by retained individuals were: (i) seeing a GP for non-HIV-related reasons and a non-HIV-related specialist and having a non-HIV-related prescription filled, (ii) seeing a non-HIV-related specialist and having a non-HIV-related prescription filled, and (iii) both seeing a GP for non-HIV-related reasons and seeing a non-HIV-related specialist. The top three non-HIV-related service combinations used by not retained individuals were: (i) seeing a GP for non-HIV-related reasons and a non-HIV-related specialist and having a non-HIV-related prescription filled, (ii) using zero non-HIV-related services, and (iii) using all four types of non-HIV-related services.

Fig. 1.

Non-HIV-related health care utilization by retention status among 5231 individuals linked to HIV care between 2000 and 2010 in BC, Canada. The distribution of the 90% of study individuals retained in HIV care (shown as a patterned bar) and the distribution of the 10% of study individuals not retained in HIV care (shown as a solid bar) are shown by the type of non-HIV-related health care service used. GP, billed Medical Services Plan non-HIV-related general practitioner visit; Hosp. adm., non-HIV-related hospital admission; Rx, non-HIV-related hospital prescription; Specialist, billed Medical Services Plan non-HIV-related specialist visit.

Table 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios relating non-HIV-related health care utilization and baseline characteristics associated with time to initial retention among 5231 individuals linked to HIV care between 2000 and 2010 in British Columbia, Canada

| Model 1 Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) |

Model 2 Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Number of types of non-HIV-related health care services used | ||

| None | 1.00 | Not included |

| One | 1.99 (1.65–2.40) | |

| Two | 2.57 (2.16–3.04) | |

| Three | 2.72 (2.30–3.22) | |

| Four | 1.70 (1.39–2.08) | |

| Non-HIV-related MSP services provided by a general practitioner (yes vs. no) | Not included | 0.79 (0.74–0.84) |

| Non-HIV-related MSP services provided by a specialist (yes vs. no) | 2.79 (2.47–3.16) | |

| Non-HIV-related hospital admissions (yes vs. no) | 0.60 (0.54–0.67) | |

| Non-HIV-related drug prescriptions (yes vs. no) | 1.28 (1.18–1.38) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 0.83 (0.77–0.90) | 0.84 (0.78–0.91) |

| Age | ||

| < 30 years | 0.92 (0.85–1.00) | 0.93 (0.86–1.01) |

| 30–39 years | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 40–49 years | 1.15 (1.07–1.24) | 1.16 (1.08–1.24) |

| ≥ 50 years | 1.15 (1.05–1.26) | 1.13 (1.03–1.23) |

| AIDS diagnosed | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.32 (1.22–1.43) | 1.32 (1.22–1.43) |

| HIV risk factors | ||

| MSM | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| PWID | 0.71 (0.66–0.77) | 0.73 (0.68–0.79) |

| Heterosexual | 1.02 (0.92–1.12) | 1.09 (0.99–1.20) |

| Other/unknown | 0.39 (0.35–0.42) | 0.42 (0.39–0.46) |

| Patient’s residing health authority | ||

| Vancouver Coastal | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Fraser | 0.88 (0.82–0.95) | 0.92 (0.86–0.99) |

| Interior | 0.88 (0.78–1.00) | 0.97 (0.85–1.10) |

| Vancouver Island | 1.04 (0.95–1.15) | 1.12 (1.02–1.24) |

| Northern | 1.00 (0.86–1.16) | 1.08 (0.93–1.25) |

| Other/unknown | 0.62 (0.48–0.80) | 0.64 (0.50–0.82) |

Model 1 includes the variable “the number of different types of non-HIV-related services used” but does not includes the four types of “non-HIV-related health care services” variables. Model 2 includes the four “types of non-HIV-related health care services” variables but does not include the “number of different types of non-HIV-related services used” variable. All variables in Weibull model 1 and model 2 were measured during the year an individual was linked to HIV care except for the four types of non-HIV-related health care service variables. These variables were measured from the time of linkage to the end of study follow-up. CI, confidence interval; GP, general practitioner; MSM, men who have sex with men; MSP, Medical Services Plan (British Columbia’s medical billing system); PWID, people who inject drugs.

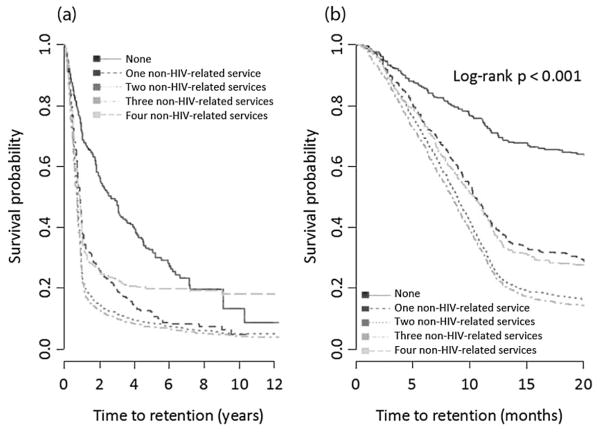

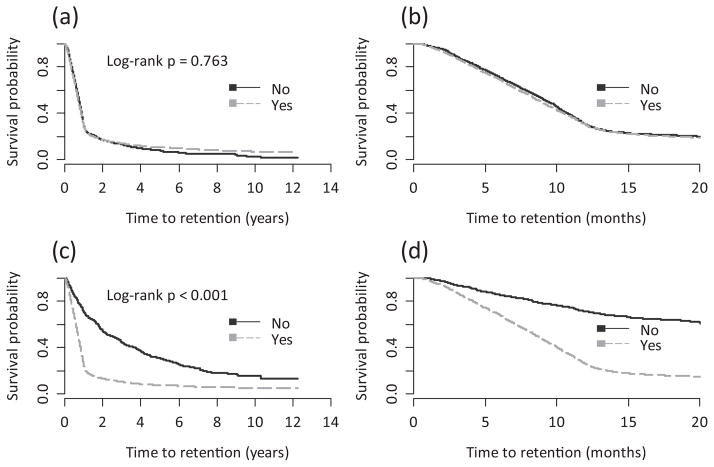

Non-HIV-related health care use and time to retention in care

Figure 2 shows Kaplan–Meier time-to-initial-retention plots by the number of different types of non-HIV-related health care services used. We observed that individuals who used zero non-HIV-related services had a statistically significantly longer time to initial retention than those who used one or more different types of non-HIV-related health care services (log-rank P < 0.001). Figure 3 shows Kaplan–Meier survival plots by non-HIV-related GP and specialist use. There was no significant difference in the time to initial retention between those who saw a GP for non-HIV-related reasons and those who did not (log-rank P = 0.7634). However, those who saw a non-HIV-related specialist had a significantly shorter time to initial retention than those who did not (log-rank P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier time to initial retention in HIV care estimates by the number of types of non-HIV-related services used. In (a), the x-axis shows the full study follow-up period, and in (b) the x-axis shows the first 20 months of study follow-up.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier time to initial retention in HIV care estimates by (a) non-HIV-related general practitioner use during the full study follow-up period; (b) non-HIV-related general practitioner use in the first 20 months of study follow-up; (c) non-HIV-related specialist use during the full study follow-up period, and (d) non-HIV-related specialist use in the first 20 months of study follow-up.

Results from our two final Weibull models are displayed in Table 2. Model 1 included the variable “number of different types of non-HIV-related services used”, and we found that, after controlling for all other covariates, compared with using zero types of non-HIV-related services, the adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) for using one, two, three and four types of non-HIV-related services was 1.99 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.65–2.40], 2.57 (95% CI 2.16–3.04), 2.72 (95% CI 2.3–3.22) and 1.70 (95% CI 1.39–2.08), respectively.

Model 2 included all of the different types of non-HIV-related health care service variables explored, but did not include the “number of different types of non-HIV-related services used”. We found that, after controlling for all other covariates, those who saw a specialist for non-HIV-related health care (vs. those who did not) (aHR 2.79; 95% CI 2.47–3.16) and those who had a non-HIV-related prescription filled (vs. those who did not) (aHR 1.28; 95% CI 1.18–1.38) had a shorter time to initial retention. However, those who saw a GP for non-HIV-related health care (vs. those who did not) (aHR 0.79; 95% CI 0.74–0.84) and those who were admitted to the hospital for non-HIV-related health care (vs. those who were not) (aHR 0.6; 95% CI 0.54–0.67) had a longer time to initial retention. Also, female individuals (compared with male individuals) (aHR 0.84; 95% CI 0.78–0.91), PWID (aHR 0.73; 95% CI 0.68–0.79) and individuals with other/unknown HIV risk factors (aHR 0.42; 95% CI 0.39–0.46) (compared with MSM) had a longer time to initial retention. In contrast, individuals with an AIDS diagnosis (compared with those without an AIDS diagnosis) and those 40–49 (aHR 1.16; 95% CI 1.08–1.24) and ≥ 50 years of age (aHR 1.13; 95% CI 1.03–1.23) (compared with 30–39-year-olds) had a shorter time to initial retention. Little variation was observed by HA, with only those living in the Vancouver Island HA having a shorter time to initial retention than those in the most densely populated HA, Vancouver Coastal (aHR 1.12; 95% CI 1.02–1.24).

Discussion

We found that that, among BC residents linked between 2000 and 2010, 90% were retained by the end of study follow-up and 70% within 1 year of being linked. The median (Q1–Q3) time to initial retention among those retained by the end of study follow-up was 9 (5–13) months. Additionally, we found that high proportions of both retained (96%) and not retained (84%) individuals used some type of non-HIV-related health care service during study follow-up. The time to initial retention decreased (i.e. improved) in a dose–response fashion with the use of non-HIV-related health care services for up to three different types of such services, but was longer for those who used four non-HIV-related services. When considering the types of non-HIV-related services used, we observed that individuals who saw a specialist for non-HIV-related health care were nearly three times more likely to be retained than those who did not. In contrast, individuals who saw a GP for non-HIV-related health care or had a non-HIV-related hospital admission during study follow-up were less likely to be retained than those who did not see a GP or were not admitted to the hospital for non-HIV-related health care, respectively. Also, we found that being male, having an AIDS diagnosis, having a known risk factor, being HIV-diagnosed between 2000 and 2007, being on ART, residing in the Vancouver Coastal HA and Vancouver Island HA, and living in an urban area were all associated with being retained by the end of study follow-up. These results were observed in the context of a universally free health care system.

Comparing our observed proportion achieving retention to previously published work is challenging because of varying published study retention definitions (which probably reflects the lack of a gold standard with which to measure retention). Published reports have defined retention using missed pVL or CD4 testing or medical appointments over a 6-month or 1-year time period [1,2,6,12,33–35]. In contrast, our definition of retained was relatively flexible as it included having an HIV-related physician visit (as demonstrated by a billed service to the MSP), having laboratory work performed, or having ART dispensed (almost half of our retained population were on ART). Furthermore, we measured time to initial retention over a longer time period than previous studies.

Individuals who used four non-HIV-related services were found to have a longer time to initial retention than those who used three or fewer non-HIV-related services. We hypothesize that the frequent use of non-HIV-related services is an indicator of underlying complexities and comorbidities (e.g. homelessness, poor mental health and substance use) which can make achieving engagement in HIV care very challenging. However, we lack social determinants of health data to assess this hypothesis, although a subanalysis found that female individuals and PWID were more likely to use four non-HIV-related services (data not shown).

Our observation that individuals who saw a GP or were admitted to the hospital for non-HIV-related health care had a longer time to initial retention than those who did/were not was of concern, as 71% of not retained individuals saw a GP for non-HIV-related health care during the follow-up period. These results suggest that there were frequent missed opportunities to engage individuals in appropriate HIV care. (Of note, non-HIV-related hospital admissions were relatively uncommon, with only 16% of not retained individuals being admitted to the hospital for non-HIV-related health care.) The reason for this observed association between seeing GPs for non-HIV-related health care and having a lower likelihood of being retained cannot be elucidated from these analyses. We speculate that this observation may be attributable to the nature of GP visits and their patterns of use in our midst. In general, GP visits tend to be problem-driven and very focused, and tend not to require a follow-up visit. Also, some patients may see GPs through walk-in clinics and would not necessarily see the same GP at every visit.

However, our results do suggest that non-HIV-related GP-targeted interventions should be considered as a means to improve initial retention. To date, few retention improvement strategies have targeted physician-level interventions [36], although Gardner et al. found that a low-cost intervention of displaying posters and brochures in six HIV clinics, alongside practitioner-communicated reminders to patients on the importance of attending all clinic visits, significantly improved clinic retention rates [37]. Based on our results, a similar intervention in a non-HIV-specific GP setting may warrant being tested as a method for improving time to initial retention in our setting. Alternatively, use of electronic medical records (EMRs) may be a method for improving retention. In 2009, the state of Louisiana (USA) implemented an EMR-based notification system after a 2007 study found that approximately 1100 individuals who did not receive CD4 or pVL monitoring for > 12 months used at least one non-HIV-related service during this period [38]. The notification system alerted medical providers providing non-HIV-related health care when they saw HIV-positive individuals who were without HIV health care for > 12 months and delivered 488 alerts and identified 345 HIV-positive individuals within a 2-year evaluation period. These alerts resulted in 82% of individuals having at least one CD4 or pVL test over the evaluation period.

In addition, consistent with previously published work, we found that women, PWID, those with other/unknown HIV transmission risk, and individuals under 40 years of age were less likely to be retained after being linked [39–44]. Increasing efforts and evidence-based interventions are urgently needed to retain these subgroups in HIV care in order to maximize individual health outcomes as well as to reduce the risk of forward HIV transmission.

There were several limitations to our study. First, we did not have access to medical charts. Thus, we cannot comment on whether or not a GP or non-HIV-related specialist was aware of or inquired about a patient’s HIV status. Secondly, physicians may not bill a visit as an HIV visit despite a visit involving HIV care, although this is unlikely in our setting, where physicians receive higher remuneration for providing HIV care than most other illnesses. Thirdly, risk category was “unknown” for a high proportion of our population. Improved risk data collection would allow for improved understanding of retention by population subgroups. Finally, as this was an observational cohort study, we tried to adjust for several important demographic and clinical characteristics; however, residual confounding may persist.

In summary, we found that the median time to initial retention was 9 months among those retained and that 70% of individuals were retained within 12 months of being linked in a setting with universal access to HIV care and treatment. Also, the majority, 84%, of not retained individuals used some type of non-HIV-related health care service during the study period. Furthermore, we observed that individuals who saw non-HIV-related specialists during the study follow-up period were nearly three times more likely to be retained than those who did not; however, those who saw a GP for non-HIV-related health care were less likely to be retained than those who did not. This missed opportunity for engagement in HIV care suggests a potential for non-HIV-related GP-targeted interventions to improve time to initial retention in HIV care.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants that make up the Seek and Treat for Optimal Prevention in HIV/AIDS cohort and the physicians, nurses, social workers and volunteers who support them. Linkage and preparation of the de-identified individual-level database was facilitated by the BC Ministry of Health.

Funding

VDL is supported by a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research, a New Investigator Award from CIHR and two grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-125948) and the US National Institute on Drug Abuse (R03DA033851-01). JSGM is supported by the British Columbia Ministry of Health and by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA036307). He has also received limited unrestricted funding from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare. BN is supported by a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Footnotes

Some of the results described here were presented as an oral presentation at the 9th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence, Miami, FL, 8–10 June 2014 (Abstract 408).

Conflicts of interest:

The funders had no role in the design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Author contributions

LL, AN, DS, VDL, GC, BN and JSGM contributed to the conception and design of the study. AN and DS performed all statistical analyses. LL drafted the manuscript. VDL and JSGM advised on all aspects of the study. All authors revised the manuscript critically and approved the final version submitted for publication.

References

- 1.Giordano TP, White AC, Sajja P, et al. Factors associated with the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients newly entering care in an urban clinic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:399–405. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg MB, Safren SA, Mimiaga MJ, Grasso C, Boswell S, Mayer KH. Nonadherence to medical appointments is associated with increased plasma HIV RNA and decreased CD4 cell counts in a community-based HIV primary care clinic. AIDS Care. 2005;17:902–907. doi: 10.1080/09540120500101658. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC, et al. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1493–1499. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rastegar DA, Fingerhood MI, Jasinski DR. Highly active antiretroviral therapy outcomes in a primary care clinic. AIDS Care. 2003;15:231–237. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000068371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Westfall AO, et al. Early retention in HIV care and viral load suppression: implications for a test and treat approach to HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59:86–93. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318236f7d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Willig JH, et al. Missed visits and mortality among patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:248–256. doi: 10.1086/595705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metsch LR, Pereyra M, Messinger S, et al. HIV transmission risk behaviors among HIV-infected persons who are successfully linked to care. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:577–584. doi: 10.1086/590153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bani-Sadr F, Bedossa P, Rosenthal E, et al. Does early antiretroviral treatment prevent liver fibrosis in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:234–236. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818ce821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horstmann E, Brown J, Islam F, Buck J, Agins BD. Retaining HIV-infected patients in care: where are we? Where do we go from here? Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:752–761. doi: 10.1086/649933. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill JM, Mainous AG, Nsereko M. The effect of continuity of care on emergency department use. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:333–338. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.4.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleishman JA, Moore RD, Conviser R, Lawrence PB, Korthuis PT, Gebo KA. Associations between outpatient and inpatient service use among persons with HIV infection: a positive or negative relationship? Health Serv Res. 2008;43:76–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sethi AK, Celentano DD, Gange SJ, Moore RD, Gallant JE. Association between adherence to antiretroviral therapy and human immunodeficiency virus drug resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1112–1118. doi: 10.1086/378301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montaner JS, Lima VD, Barrios R, et al. Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage, population viral load, and yearly new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia, Canada: a population-based study. Lancet. 2010;376:532–539. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60936-1. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U S Gov’t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lima VD, Hogg RS, Montaner JS. Expanding HAART treatment to all currently eligible individuals under the 2008 IAS-USA Guidelines in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010991. Research Support, Non-U S Gov’t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang CT, Hsu HM, Twu SJ, et al. Decreased HIV transmission after a policy of providing free access to highly active antiretroviral therapy in Taiwan. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:879–885. doi: 10.1086/422601. Research Support, Non-U S Gov’t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das M, Chu PL, Santos GM, et al. Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in new HIV infections in San Francisco. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011068. Research Support, Non-U S Gov’t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia Z, Mao Y, Zhang F, et al. Antiretroviral therapy to prevent HIV transmission in serodiscordant couples in China (2003–11): a national observational cohort study. Lancet. 2013;382:1195–1203. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61898-4. Research Support, Non-U S Gov’t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood E, Kerr T, Marshall BDL, et al. Longitudinal community plasma HIV-1 RNA concentrations and incidence of HIV-1 among injecting drug users: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:b1649. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, Fleming TR, Team HS. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with antiretroviral therapy REPLY. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1935. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1110588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanser F, Barnighausen T, Grapsa E, Zaidi J, Newell ML. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Science. 2013;339:966–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1228160. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U S Gov’t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stover J, Hallett TB, Wu Z, et al. How can we get close to zero? The potential contribution of biomedical prevention and the investment framework towards an effective response to HIV. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e111956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111956. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skarbinski JRE, Paz-Bailey G, Hall I, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus transmission at each step of the care continuum in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:588–596. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8180. Original Investigation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nosyk B, Montaner JS, Colley G, et al. The cascade of HIV care in British Columbia, Canada, 1996–2011: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:40–49. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70254-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montaner JS, Lima VD, Harrigan PR, et al. Expansion of HAART coverage is associated with sustained decreases in HIV/AIDS morbidity, mortality and HIV transmission: the ‘HIV Treatment as Prevention’ experience in a Canadian setting. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e87872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087872. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U S Gov’t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heath K, Samji H, Nosyk B, et al. Cohort profile: seek and treat for the optimal prevention of HIV/AIDS in British Columbia (STOP HIV/AIDS BC) Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:1073–1081. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nosyk B, Colley G, Yip B, et al. Application and validation of case-finding algorithms for identifying individuals with human immunodeficiency virus from administrative data in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e54416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054416. Research Support, Non-U S Gov’t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeni PG, Hammer SM, Carpenter CCJ, et al. Antiretroviral treatment for adult HIV infection in 2002 – updated recommendations of the international AIDS Society-USA panel. JAMA. 2002;288:222–235. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Cahn P, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection 2010 recommendations of the international AIDS society-USA panel. JAMA. 2010;304:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammer SM, Eron JJ, Reiss P, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection – 2008 recommendations of the International AIDS Society USA panel. JAMA. 2008;300:555–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Hoy JF, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection 2012 recommendations of the international antiviral society-USA panel. JAMA. 2012;308:387–402. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carroll KJ. On the use and utility of the Weibull model in the analysis of survival data. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24:682–701. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lima VD, Geller J, Bangsberg DR, et al. The effect of adherence on the association between depressive symptoms and mortality among HIV-infected individuals first initiating HAART. AIDS. 2007;21:1175–1183. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32811ebf57. Research Support, Non-U S Gov’t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersen M, Hockman E, Smereck G, et al. Retaining women in HIV medical care. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2007;18:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradford JB, Coleman S, Cunningham W. HIV system navigation: an emerging model to improve HIV care access. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:S49–S58. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet. 2008;372:293–299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61113-7. Research Support, Non-U S Gov’t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higa DH, Marks G, Crepaz N, Liau A, Lyles CM. Interventions to improve retention in HIV primary care: a systematic review of U.S. studies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2012;9:313–325. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0136-6. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gardner LI, Marks G, Craw JA, et al. A low-effort, clinic-wide intervention improves attendance for HIV primary care. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1124–1134. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis623. Multicenter Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S. Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herwehe J, Wilbright W, Abrams A, et al. Implementation of an innovative, integrated electronic medical record (EMR) and public health information exchange for HIV/AIDS. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19:448–452. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Israelski D, Gore-Felton C, Power R, Wood MJ, Koopman C. Sociodemographic characteristics associated with medical appointment adherence among HIV-seropositive patients seeking treatment in a county outpatient facility. Prev Med. 2001;33:470–475. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poole WK, Perritt R, Shah KB, et al. A characterisation of patient drop outs in a cohort of HIV positive homosexual/bisexual men and intravenous drug users. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55:66–67. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.1.66. Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arici C, Ripamonti D, Maggiolo F, et al. Factors associated with the failure of HIV-positive persons to return for scheduled medical visits. HIV Clin Trials. 2002;3:52–57. doi: 10.1310/2XAK-VBT8-9NU9-6VAK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rumptz MH, Tobias C, Rajabiun S, et al. Factors associated with engaging socially marginalized HIV-positive persons in primary care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:S30–S39. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giordano TP, Visnegarwala F, White AC, Jr, et al. Patients referred to an urban HIV clinic frequently fail to establish care: factors predicting failure. AIDS Care. 2005;17:773–783. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331336652. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waldrop-Valverde D, Guo Y, Ownby RL, Rodriguez A, Jones DL. Risk and protective factors for retention in HIV care. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:1483–1491. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0633-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]