Abstract

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have discovered hundreds of loci associated with complex brain disorders but it remains unclear in which cell types these loci are active. Here we integrate GWAS results with single-cell transcriptomic data from the entire mouse nervous system to systematically identify cell types underlying brain complex traits. We show that psychiatric disorders are predominantly associated with projecting excitatory and inhibitory neurons. Neurological diseases were associated with different cell types, which is consistent with other lines of evidence. Notably, Parkinson’s disease was not only genetically associated with cholinergic and monoaminergic neurons (which include dopaminergic neurons) but also with enteric neurons and oligodendrocytes. Using post-mortem brain transcriptomic data, we confirmed alterations in these cells, even at the earliest stages of disease progression. Our study provides an important framework for understanding the cellular basis of complex brain maladies, and reveals an unexpected role of oligodendrocytes in Parkinson’s disease.

Introduction

Understanding the genetic basis of complex brain disorders is critical for developing rational therapeutics. In the last decade, GWAS have identified thousands of highly significant loci 1–4. However, interpretation of GWAS remains challenging. First, >90% of the identified variants are located in non-coding regions 5, complicating precise identification of risk genes. Second, extensive linkage disequilibrium present in the human genome confounds efforts to pinpoint causal variants. Finally, it remains unclear in which tissues and cell types these variants are active, and how they disrupt specific biological networks to impact disease risk.

Functional genomic studies from brain are now seen as critical for interpretation of GWAS findings as they can identify functional regions (e.g., open chromatin, enhancers, transcription factor binding sites) and target genes (via chromatin interactions and eQTLs) 6. Gene regulation varies substantially across tissues and cell types 7,8, and hence it is critical to perform functional genomic studies in empirically identified cell types or tissues.

Multiple groups have developed strategies to identify tissues associated with complex traits 9–13, but few have focused on the identification of salient cell types within a tissue. Furthermore, previous studies used a small number of cell types derived from one or few different brain regions 3,11–17. For example, we recently showed that, among 24 brain cell types, four types of neurons were consistently associated with schizophrenia 11. We were explicit that this conclusion was limited by the relatively few brain regions studied; other cell types from unsampled regions could conceivably contribute to the disorder.

Here, we integrate a wider range of gene expression data – tissues across the human body and single-cell gene expression data from an entire nervous system – to identify tissues and cell types underlying a large number of complex traits (Fig. 1a,b). We find that psychiatric and cognitive traits are generally associated with similar cell types whereas neurological disorders are associated with different cell types. Notably, we show that Parkinson’s disease is associated with cholinergic and monoaminergic neurons, enteric neurons and oligodendrocytes, providing new clues into its etiology.

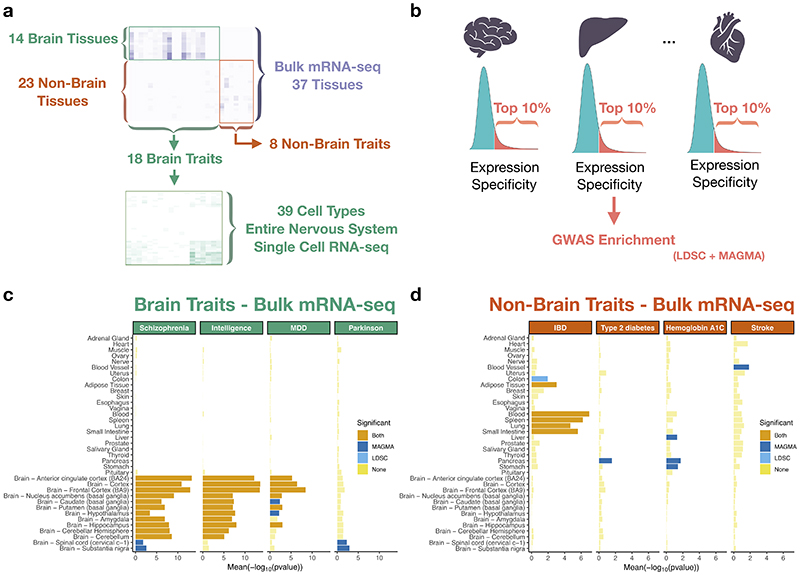

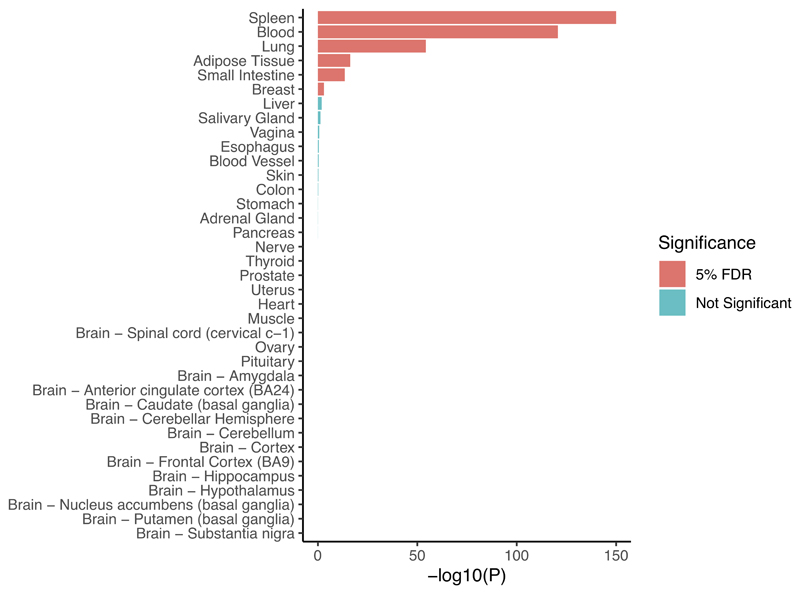

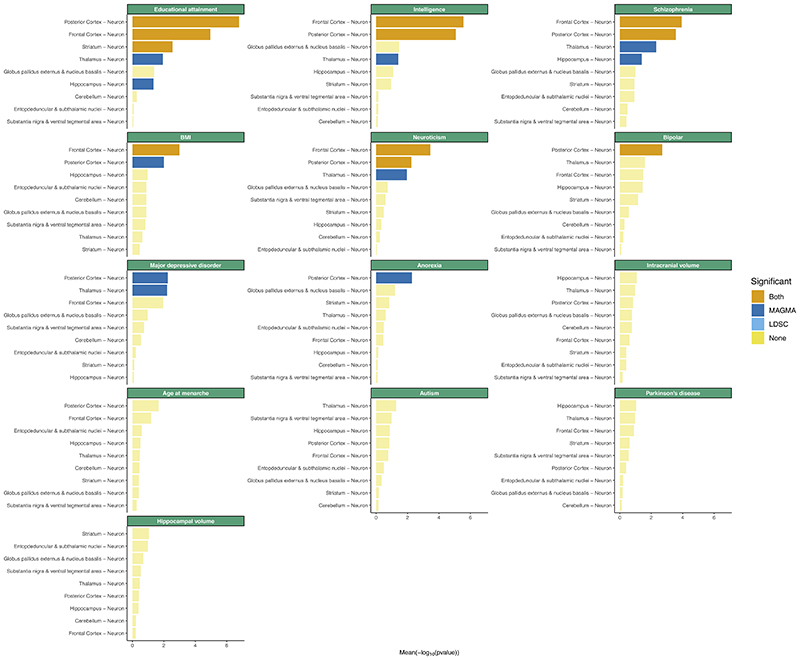

Figure 1. Study design and tissue-level associations.

Heat map of trait – tissue/cell types associations (-log10P) for the selected traits. (a) Trait – tissue/cell types associations were performed using MAGMA and LDSC (testing for enrichment in genetic association of the top 10% most specific genes in each tissue/cell type). (b) Tissue – trait associations for selected brain related traits. (c) Tissue – trait associations for selected non-brain related traits. (d) The mean strength of association (-log10P) of MAGMA and LDSC is shown and the bar color indicates whether the tissue is significantly associated with both methods, one method or none (significance threshold: 5% false discovery rate).

Results

Association of traits with tissues using bulk RNA-seq

Our goal was to use GWAS results to identify relevant tissues and cell types. Our primary focus was human phenotypes whose etiopathology is based in the central nervous system. We thus obtained 18 sets of GWAS summary statistics for brain-related complex traits. For comparison, we included GWAS summary statistics for 8 diseases and traits with large sample sizes whose etiopathology is not rooted in the central nervous system (Methods).

We first aimed to identify human tissues showing enrichment for genetic associations using bulk-tissue RNA-seq (37 tissues) from GTEx 7. To robustly identify tissues implied by these 26 GWAS, we used two approaches (MAGMA 18 and LDSC12,19) which employ different assumptions (Methods). For both methods, we tested whether the 10% most specific genes in each tissue were enriched in genetic associations with the different traits (Fig. 1b).

Examination of non-brain traits found, as expected, associations with salient tissues. For example, as shown in Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 1, inflammatory bowel disease was strongly associated with immune tissues (blood, spleen) and alimentary tissues impacted by the disease (small intestine and colon). Lung and adipose tissue were also significantly associated with inflammatory bowel disease, possibly because of the high specificity of immune genes in these two tissues (Extended Data Figure 1). Type 2 diabetes was associated with the pancreas, while hemoglobin A1C, which is used to diagnose type 2 diabetes and monitor glycemic controls in diabetic patients, was associated with the pancreas, liver and stomach (Fig. 1d). Stroke and coronary artery disease were most associated with blood vessels and waist to hip ratio was most associated with adipose tissue (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1).

For brain-related traits (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1), 13 of 18 traits were significantly associated with one or more GTEx brain regions. For example, schizophrenia, intelligence, educational attainment, neuroticism, BMI and MDD were most significantly associated with brain cortex, frontal cortex or anterior cingulate cortex, while Parkinson’s disease was most significantly associated with the substantia nigra (as expected) and spinal cord (Fig. 1c). Alzheimer’s disease was associated with tissues with prominent roles in immunity (blood and spleen) consistent with other studies 20–22, but also with the substantia nigra and spinal cord, while stroke was associated with blood vessel (consistent with a role of arterial pathology in stroke) 23.

In conclusion, we show that tissue-level gene expression allows identification of relevant tissues for complex traits, indicating that our methodology is suitable to explore trait-gene expression associations at the cell type level.

Association of brain complex traits with cell types

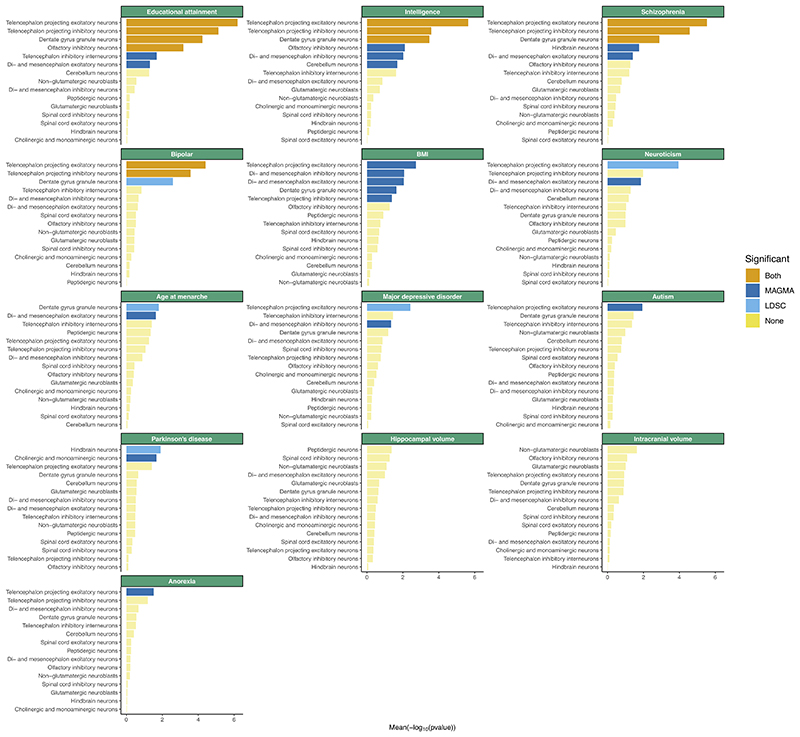

We leveraged gene expression data from 39 broad categories of cell types from the mouse central and peripheral nervous system 24 to systematically map brain-related traits to cell types (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Figure 2). Our use of mouse data to inform human genetic findings was carefully considered (see Discussion).

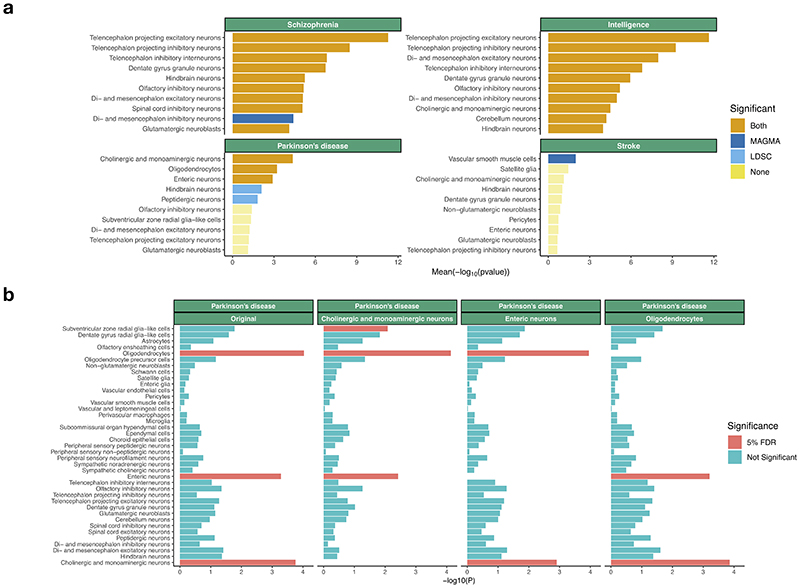

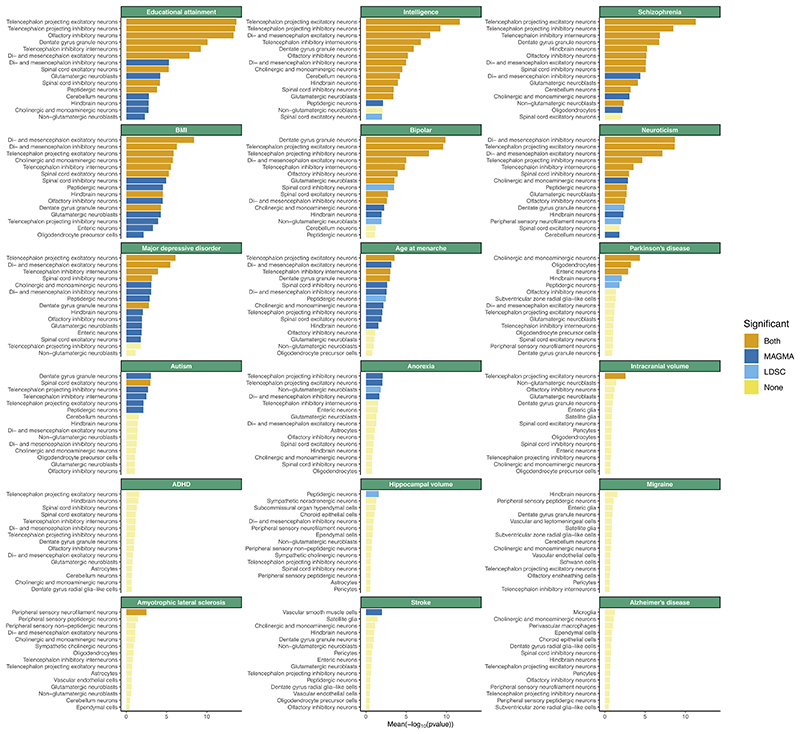

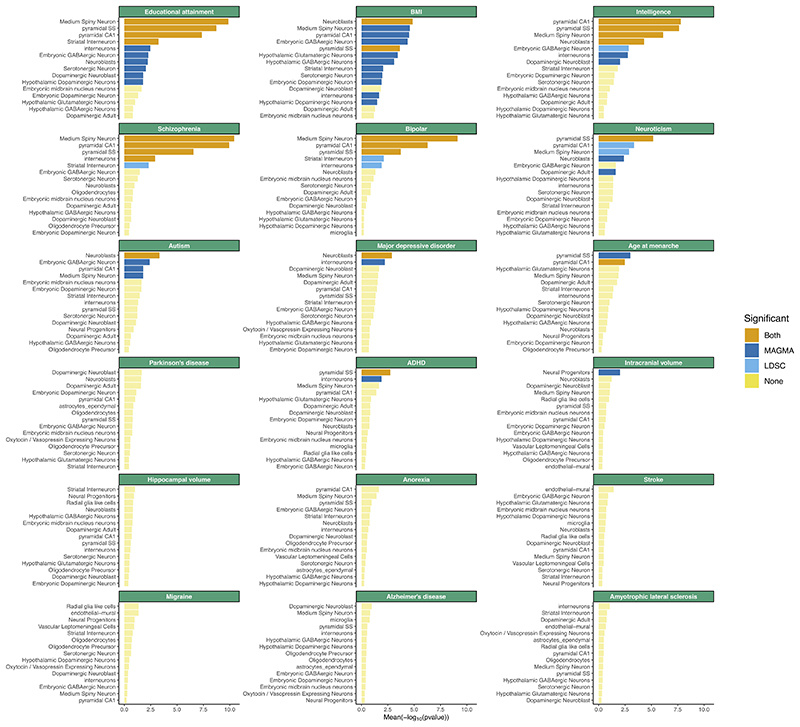

Figure 2. Association of selected brain related traits with cell types from the entire nervous system.

Associations of the top 10 most associated cell types are shown. (a) Conditional analysis results for Parkinson’s disease using MAGMA. The label indicates the cell type the association analysis is being conditioned on. (b) The mean strength of association (-log10P) of MAGMA and LDSC is shown and the bar color indicates whether the cell type is significantly associated with both methods, one method or none (significance threshold: 5% false discovery rate).

As in our previous study of schizophrenia based on a small number of brain regions 11, we found the strongest signals for telencephalon projecting neurons (i.e. excitatory neurons from the cortex, hippocampus and amygdala), telencephalon projecting inhibitory neurons (i.e. medium spiny neurons from the striatum) and telencephalon inhibitory neurons (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 2). We also found that other types of neurons were associated with schizophrenia albeit less significantly (e.g., dentate gyrus granule neurons). Other psychiatric and cognitive traits had similar cellular association patterns to schizophrenia (Extended Data Figure 2,3 and Supplementary Table 2). We did not observe significant associations with immune or vascular cells for any psychiatric disorders or cognitive traits.

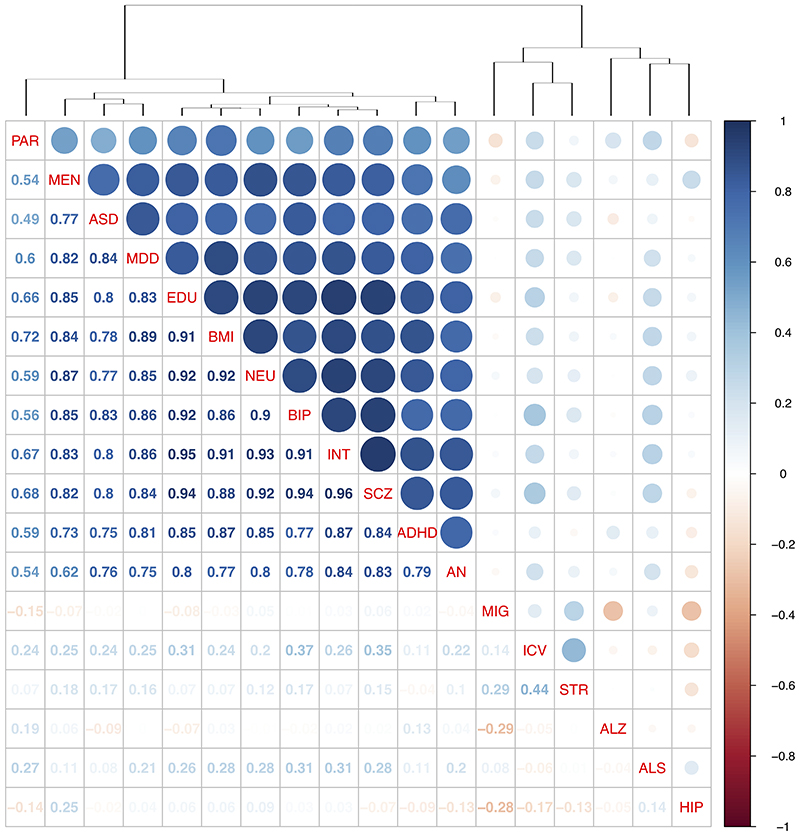

Neurological disorders generally implicated fewer cell types, possibly because neurological GWAS had lower signal than GWAS of cognitive, anthropometric, and psychiatric traits (Supplementary Fig. 2). Consistent with the genetic correlations (Supplementary Note), the pattern of associations for neurological disorders was distinct from psychiatric disorders (Extended Data Figure 2,3), reflecting that neurological disorders have minimal functional overlap with psychiatric disorders 25.

Stroke was significantly associated with vascular smooth muscle cells (Fig. 2a) consistent with an important role of vascular processes for this trait. Alzheimer’s disease had the strongest signal in microglia, as reported previously 10,16,26, but the association did not survive multiple testing correction.

We found that Parkinson’s disease was significantly associated with cholinergic and monoaminergic neurons (Fig. 2a). This cluster consists of neurons (Supplementary Table 3) that are known to degenerate in Parkinson’s disease 27–29, such as dopaminergic neurons from the substantia nigra (the hallmark of Parkinson’s disease), but also serotonergic and glutamatergic neurons from the raphe nucleus 30, noradrenergic neurons31, as well as neurons from afferent nuclei in the pons 32 and the medulla (the brain region associated with the earliest lesions in Parkinson’s disease 27). In addition, hindbrain neurons and peptidergic neurons were also significantly associated with Parkinson’s disease (with LDSC only). Interestingly, we also found that enteric neurons were significantly associated with Parkinson’s disease (Fig. 2a), which is consistent with Braak’s hypothesis, which postulates that Parkinson’s disease could start in the gut and travel to the brain via the vagus nerve 33,34. Furthermore, we found that oligodendrocytes (mainly sampled in the midbrain, medulla, pons, spinal cord and thalamus, Supplementary Fig. 3) were significantly associated with Parkinson’s disease, indicating a strong glial component to the disorder. This finding was unexpected but consistent with the strong association of the spinal cord at the tissue level (Fig. 1c), as the spinal cord contains the highest proportion of oligodendrocytes (71%) in the nervous system 24. Altogether, these findings provide genetic evidence for a role of enteric neurons, cholinergic and monoaminergic neurons, as well as oligodendrocytes in Parkinson’s disease etiology.

Neuronal prioritization in the mouse central nervous system

A key goal of this study was to prioritize specific cell types for follow-up experimental studies. As our metric of gene expression specificity was computed based on all cell types in the nervous system, it is possible that the most specific genes in a given cell type capture genes that are shared within a high level category of cell types (e.g. neurons). To rule out this possibility, we computed new specificity metrics based only on neurons from the central nervous system (CNS). We then tested whether the top 10% most specific genes for each CNS neuron were enriched in genetic association for the brain related traits that had a significant association with a CNS neuron (13/18) in our initial analysis.

Using the CNS neuron gene expression specificity metrics, we observed a reduction in the number of neuronal cell types associated with the different traits (Extended Data Figure 4), suggesting that some of the signal was driven by core neuronal genes. However, we found that multiple neuronal cell types remained associated with a number of traits. For example, we found that telencephalon projecting excitatory and projecting inhibitory neurons were strongly associated with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, educational attainment and intelligence using both LDSC and MAGMA. Similarly, telencephalon projecting excitatory neurons were significantly associated with BMI, neuroticism, MDD, autism and anorexia using one of the two methods, while hindbrain neurons and cholinergic and monoaminergic neurons remained significantly associated with Parkinson’s disease.

Altogether, these results suggest that specific types of CNS neurons can be prioritized for follow-up experimental studies for multiple traits.

Trait-cell type associations conditioning on other traits

As noted above, the pattern of associations of psychiatric and cognitive traits were highly correlated across the 39 different cell types tested (Extended Data Figure 3). For example, the Spearman rank correlation of cell type associations (-log10P) between schizophrenia and intelligence was 0.96 (0.94 for educational attainment) as both traits had the strongest signal in telencephalon projecting excitatory neurons and little signal in immune or vascular cells. In addition, we observed that genes driving the association signal in the top cell types of the two traits were enriched in relatively similar GO terms involving neurogenesis and synaptic processes (Supplementary Note). We evaluated two possible explanations for these findings: (a) schizophrenia and intelligence are both associated with the same genes that are specifically expressed in the same cell types or (b) schizophrenia and intelligence are associated with different sets of genes that are both specific to the same cell types. Given that these two traits have a significant negative genetic correlation (rg=-0.22, from GWAS results alone) (Supplementary Table 4), we hypothesized that the strong overlap in cell type associations for schizophrenia and intelligence was due to the second explanation.

To evaluate these hypotheses, we tested whether the 10% most specific genes for each cell type were enriched in genetic associations for schizophrenia controlling for the gene-level genetic association of intelligence using MAGMA (and vice versa) and found that the pattern of associations were largely unaffected. Similarly, we found that controlling for educational attainment had little effect on the schizophrenia associations and vice versa (Extended Data Figure 5). In other words, genes driving the cell type associations of schizophrenia appear to be distinct from genes driving the cell types associations of cognitive traits.

Trait-cell type associations conditioning on cell types

Many neuronal cell types passed our stringent significance threshold for multiple brain traits (Fig. 2a). This could be because gene expression profiles are highly correlated across cell types and/or because many cell types are independently associated with the different traits. In order to address this, we performed univariate conditional analysis using MAGMA, testing whether cell type associations remained significant after controlling for the 10% most specific genes from other cell types (Supplementary Table 5). We observed that multiple cell types were independently associated with age at menarche, anorexia, autism, bipolar, BMI, educational attainment, intelligence, MDD, neuroticism and schizophrenia (Supplementary Fig. 4). As in our previous study11, we found that the association between schizophrenia and telencephalon projecting inhibitory neurons (i.e. medium spiny neurons) was independent from telencephalon projecting excitatory neurons (i.e. pyramidal neurons). For Parkinson’s disease, enteric neurons, oligodendrocytes and cholinergic and monoaminergic neurons were independently associated with the disorder (Fig. 2b), suggesting that these three different cell types play an independent role in the etiology of the disorder.

Replication in other single-cell RNA-seq datasets

To assess the robustness of our results, we repeated these analyses in independent datasets. A key caveat is that these other datasets did not sample the entire nervous system as in the analyses above.

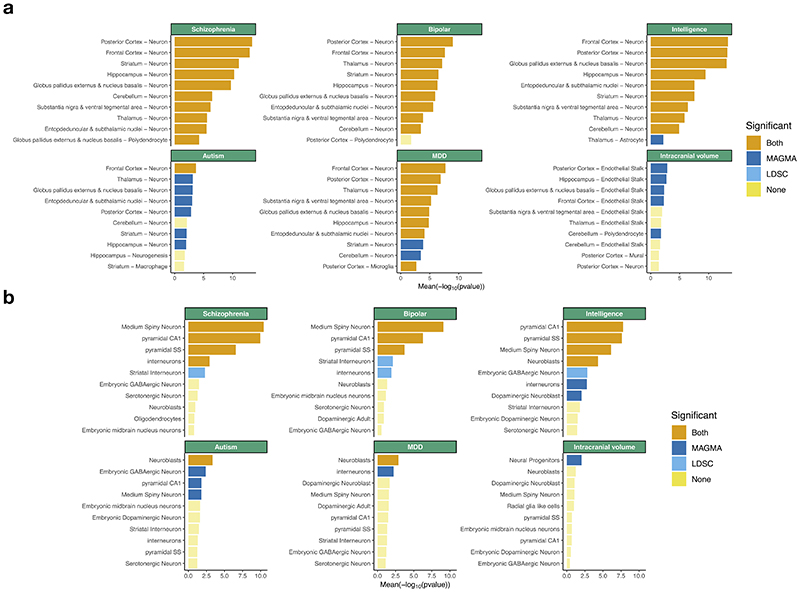

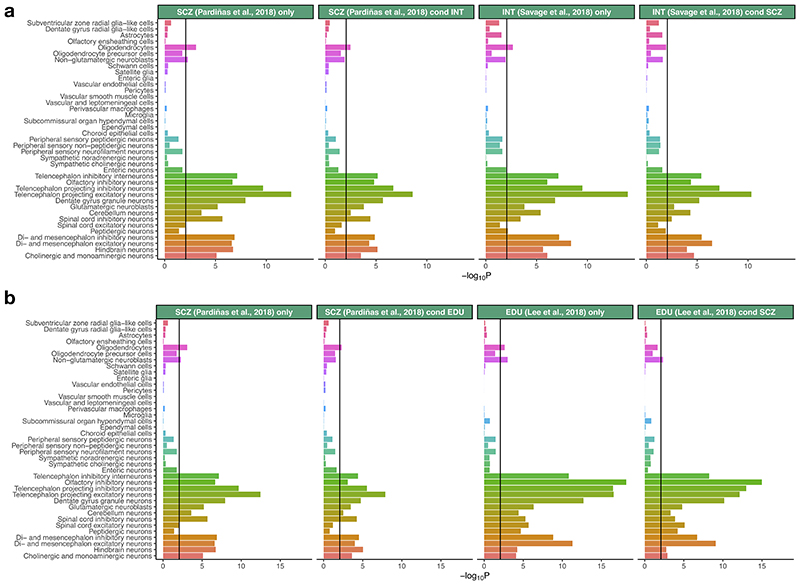

First, we used a single-cell RNA-seq dataset that identified 88 broad categories of cell types from 9 mouse brain regions 35. We found similar patterns of association in this external dataset (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Figure 6 and Supplementary Table 6). Notably, for schizophrenia, we strongly replicated associations with neurons from the cortex, hippocampus and striatum. We also observed similar cell type associations for other psychiatric and cognitive traits (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Figure 6,7). For neurological disorders, we found that stroke was significantly associated with mural cells while Alzheimer’s disease was significantly associated with microglia (Extended Data Figure 6). The associations of Parkinson’s disease with neurons from the substantia nigra and oligodendrocytes were significant at a nominal level in this dataset (P=0.006 for neurons from the substantia nigra, P=0.027 for oligodendrocytes using LDSC). By computing gene expression specificity within neurons, we replicated our findings that neurons from the cortex can be prioritized for multiple traits (schizophrenia, bipolar, educational attainment, intelligence, BMI, neuroticism, MDD, anorexia) (Extended Data Figure 8).

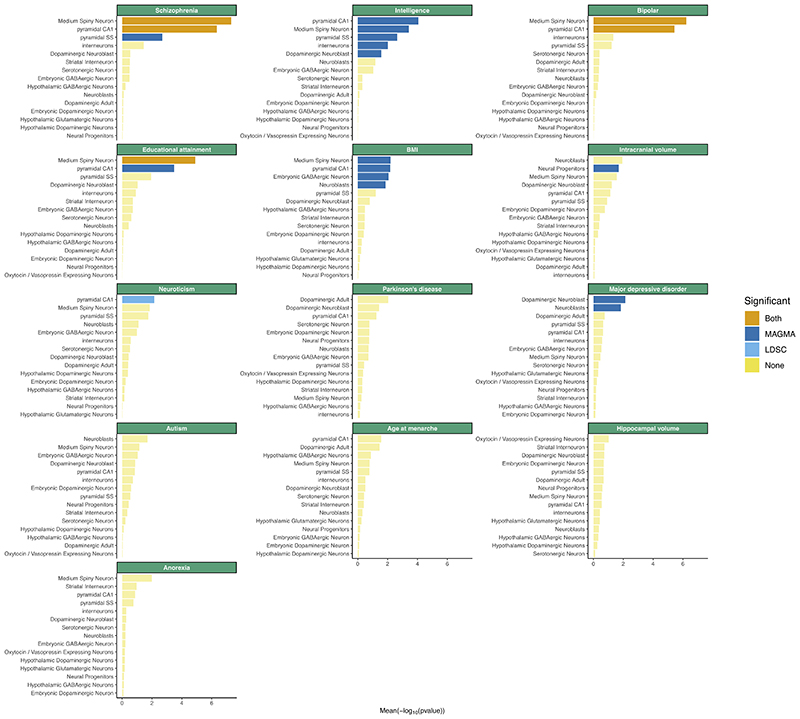

Figure 3. Replication of cell type – trait associations in mouse datasets.

Tissue – trait associations are shown for the 10 most association cell types among 88 cell types from 9 different brain regions. (a) Tissue – trait associations are shown for the 10 most association cell types among 24 cell types from 5 different brain regions. (b) The mean strength of association (-log10P) of MAGMA and LDSC is shown and the bar color indicates whether the cell type is significantly associated with both methods, one method or none (significance threshold: 5 % false discovery rate).

Second, we reanalyzed these GWAS datasets using our previous dataset 11 (24 cell types from five mouse brain regions, Fig. 3b, Extended Data Figure 9 and Supplementary Table 7). We again found strong associations of pyramidal neurons from the somatosensory cortex, pyramidal neurons from the CA1 region of the hippocampus (both corresponding to telencephalon projecting excitatory neurons in our main dataset), and medium spiny neurons from the striatum (corresponding to telencephalon projecting inhibitory neurons) with psychiatric and cognitive traits. MDD and autism were most associated with neuroblasts, while intracranial volume was most associated with neural progenitors. The association of dopaminergic adult neurons with Parkinson’s disease was significant at a nominal level using LDSC (P=0.01), while oligodendrocytes did not replicate in this dataset, perhaps because they were not sampled from the regions affected by the disorder (i.e. spinal cord, pons, medulla or midbrain). A within-neuron analysis again found that projecting excitatory (i.e. pyramidal CA1) and projecting inhibitory neurons (i.e. medium spiny neurons) can be prioritized for multiple traits (schizophrenia, bipolar, intelligence, educational attainment, BMI). In addition, neuroblasts could be prioritized for MDD and neural progenitors could be prioritized for intracranial volume (Extended Data Figure 10).

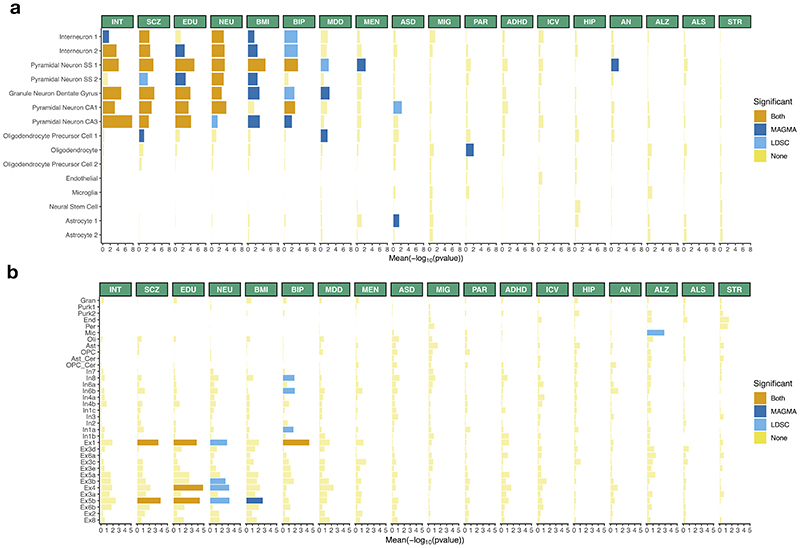

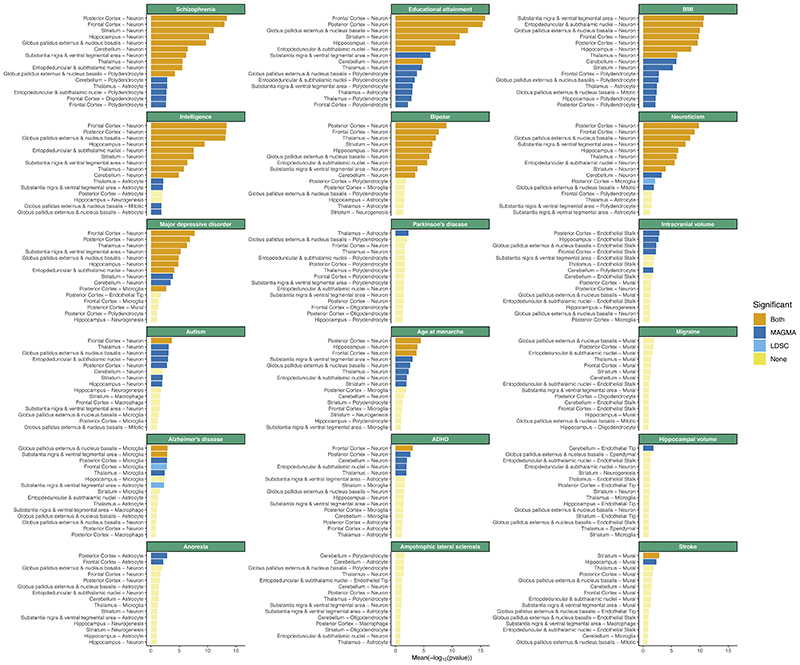

Third, we evaluated a human dataset consisting of 15 different cell types from cortex and hippocampus 36 (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 8). We replicated our findings with psychiatric and cognitive traits being associated with pyramidal neurons (excitatory) and interneurons (inhibitory) from the somatosensory cortex and hippocampus. We also replicated the association of Parkinson’s disease with oligodendrocytes (enteric neurons and cholinergic and monoaminergic neurons were not sampled in this dataset). No cell types reached our significance threshold using specificity metrics computed within-neurons, possibly because of similarities in the transcriptomes of neurons from the cortex and hippocampus.

Figure 4. Human replication of cell type – trait associations.

Cell type - trait associations for 15 cell types (derived from single-nuclei RNA-seq) from 2 different brain regions (cortex, hippocampus). (a) Cell type - trait associations for 31 cell types (derived from single-nuclei RNA-seq) from 3 different brain regions (frontal cortex, visual cortex and cerebellum). (b) The mean strength of association (-log10P) of MAGMA and LDSC is shown and the bar color indicates whether the cell type is significantly associated with both methods, one method or none (significance threshold: 5% false discovery rate). INT (intelligence), SCZ (schizophrenia), EDU (educational attainment), NEU (neuroticism), BMI (body mass index), BIP (bipolar disorder), MDD (Major depressive disorder), MEN (age at menarche), ASD (autism spectrum disorder), MIG (migraine), PAR (Parkinson’s disease), ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), ICV (intracranial volume), HIP (hippocampal volume), AN (anorexia nervosa), ALZ (Alzheimer’s disease), ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), STR (stroke).

Fourth, we evaluated a human dataset consisting of 31 different cell types from 3 different brain regions (visual cortex, frontal cortex and cerebellum) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 9) 37. We found that schizophrenia, educational attainment, neuroticism and BMI were associated with excitatory neurons, while bipolar was associated with both excitatory and inhibitory neurons. As observed previously 10,16,26, Alzheimer’s disease was significantly associated with microglia. Oligodendrocytes were not significantly associated with Parkinson’s disease in this dataset, again possibly because the spinal cord, pons, medulla and midbrain were not sampled. No cell types reached our significance threshold using specificity metrics computed within neurons in this dataset.

Validation of oligodendrocyte pathology in Parkinson

We investigated the role of oligodendrocytes in Parkinson’s disease. First, we confirmed the association of oligodendrocytes with Parkinson’s disease by combining evidence across all datasets (Fisher’s combined probability test, P=2.5*10-7 using MAGMA and 6.3*10-3 using LDSC) (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 5). In addition, oligodendrocytes remained significantly associated with Parkinson’s disease after conditioning on the top neuronal cell type in each dataset (P=1.2*10-7, Fisher’s combined probability test).

Third, we tested whether genes with rare variants associated with Parkinsonism (Supplementary Table 10) were specifically expressed in cell types from the mouse nervous system (Method). As for the common variant, we found the strongest enrichment for cholinergic and monoaminergic neurons (Supplementary Table 11). However, we did not observe any significant enrichments for oligodendrocytes or enteric neurons for these genes.

Fourth, we applied EWCE 10 to test whether genes that are up/down-regulated in human post-mortem Parkinson’s disease brains (from six separate cohorts) were enriched in cell types located in the substantia nigra and ventral midbrain (Fig. 5). Three of the studies had a case-control design and measured gene expression in: (a) the substantia nigra of 9 controls and 16 cases 38, (b) the medial substantia nigra of 8 controls and 15 cases39, and (c) the lateral substantia nigra of 7 controls and 9 cases 39. In all three studies, downregulated genes in Parkinson’s disease were specifically enriched in dopaminergic neurons (consistent with the loss of this particular cell type in disease), while upregulated genes were significantly enriched in cells from the oligodendrocyte lineage. This suggests that an increased oligodendrocyte activity or proliferation could play a role in Parkinson’s disease etiology. Surprisingly, no enrichment was observed for microglia, despite recent findings 40,41.

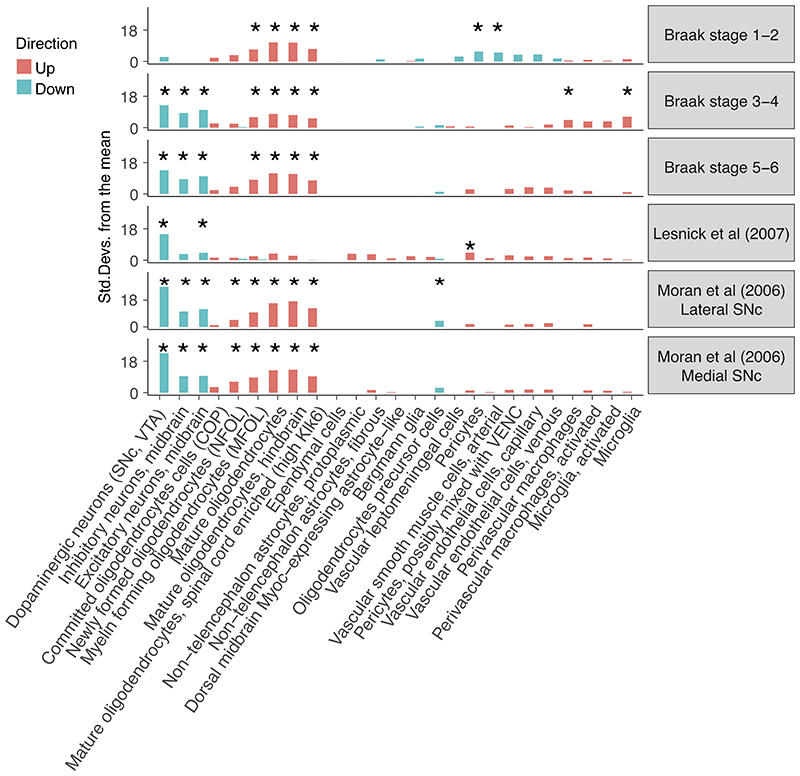

Figure 5. Enrichment of Parkinson’s disease differentially expressed genes in cell types from the substantia nigra.

Enrichment of the 500 most up/down regulated genes (Braak stage 0 vs Braak stage 1—2, 3—4 and 5—6, as well as cases vs controls) in postmortem human substantia nigra gene expression samples. The enrichments were obtained using EWCE10. A star shows significant enrichments after multiple testing correction (P<0.05/(25*6).

We also analyzed gene expression data from post-mortem human brains which had been scored by neuropathologists for their Braak stage 42. Differential expression was calculated between brains with Braak scores of zero (controls) and brains with Braak scores of 1—2, 3—4 and 5—6. At the latter stages (Braak scores 3—4 and 5—6), downregulated genes were specifically expressed in dopaminergic neurons, while upregulated genes were specifically expressed in oligodendrocytes (Fig. 5), as observed in the case-control studies. Moreover, Braak stage 1 and 2 are characterized by little degeneration in the substantia nigra and, consistently, we found that downregulated genes were not enriched in dopaminergic neurons at this stage. Notably, upregulated genes were already strongly enriched in oligodendrocytes at Braak Stages 1-2. These results not only support the genetic evidence indicating that oligodendrocytes may play a causal role in Parkinson’s disease, but indicate that their involvement precedes the emergence of pathological changes in the substantia nigra.

Discussion

In this study, we used gene expression data from cells sampled from the entire nervous system to systematically map cell types to GWAS results from multiple psychiatric, cognitive, and neurological complex phenotypes.

We note several limitations. First, we emphasize that we can implicate a particular cell type but it is premature to exclude cell types for which we do not have data 11. Second, we used gene expression data from mouse to understand human phenotypes. We believe our approach is appropriate for several reasons. (A) Crucially, the key findings replicated in human data. (B) Single-cell RNA-seq is achievable in mouse but difficult in human neurons (where single-nuclei RNA-seq is typical 36,37,43,44). In brain, differences between single-cell and single-nuclei RNA-seq are important as transcripts that are missed by sequencing nuclei are important for psychiatric disorders 11, and we previously showed that dendritically-transported transcripts are specifically depleted from nuclei datasets 11 (confirmed in four additional datasets, Supplementary Fig. 6). (C) Correlations in gene expression for cell type across species is high (median correlation 0.68, Supplementary Fig. 7), and as high or higher than correlations across methods within cell type and species (single-cell vs single-nuclei RNA-seq, median correlation 0.6) 45. (D) We only evaluated protein-coding genes with 1:1 orthologs between mouse and human, which are highly conserved. (E) We previously showed that gene expression data cluster by cell type and not by species 11, indicating broad conservation of core brain cellular functions across species. (F) We used a large number of genes to map cell types to traits (~1500 genes for each cell type), minimizing potential bias due to individual genes differentially expressed across species. (G) If there were strong differences in cell type gene expression between mouse and human, we would not expect that specific genes in mouse cell types would be enriched in genetic associations with human disorders. However, it remains possible that some cell types have different gene expression patterns between mouse and human, are only present in one species, have a different function or are involved in different brain circuits.

A third limitation is that gene expression data were from adolescent mice. Although many psychiatric and neurological disorders have onsets in adolescence, some have onsets earlier (autism) or later (Alzheimer’s and Parkinson's disease). It is thus possible that some cell types are vulnerable at specific developmental times. Data from studies mapping cell types across brain development and aging are required to resolve this issue.

We found that psychiatric traits implicated largely similar cell types. These biological findings are consistent with genetic and epidemiological evidence of a general psychopathy factor underlying diverse psychiatric disorders 25,46,47. Although intelligence and educational attainment implicated similar cell types, conditional analyses showed that the same cell types were implicated for different reasons. This suggests that different sets of genes highly specific to the same cell types contribute independently to schizophrenia and cognitive traits.

Our findings for neurological disorders were strikingly different from psychiatric disorders. In contrast to previous studies that either did not identify any cell type associations with Parkinson’s disease 48 or identified significant associations with cell types from the adaptive immune system 41, we found that cholinergic and monoaminergic neurons (which include dopaminergic neurons), enteric neurons and oligodendrocytes were significantly and independently associated with the disease. Our findings suggest that dopaminergic neuron loss in Parkinson’s disease (the hallmark of the disease) is at least partly due to intrinsic biological mechanisms.

Interestingly, enteric neurons were also associated with Parkinson’s disease. This result is in line with prior evidence implicating the gut in Parkinson’s disease. Notably, dopaminergic defects and Lewy bodies (i.e. abnormal aggregates of proteins enriched in α-synuclein) are found in the enteric nervous system of patients affected by Parkinson’s disease 49,50. In addition, Lewy bodies have been observed in patients up to 20 years prior to their diagnosis 51 and sectioning of the vagus nerve (which connects the enteric nervous system to the central nervous system) was shown to reduce the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease 52. Therefore, our results linking enteric neurons with Parkinson’s disease provides new genetic evidence for Braak’s hypothesis 33.

The association of oligodendrocytes with Parkinson’s disease was more unexpected. A possible explanation is that this association could be due to a related disorder (e.g., multiple system atrophy, characterized by Parkinsonism and accumulation of α-synuclein in glial cytoplasmic inclusions 53). However, this explanation is unlikely as multiple system atrophy is a very rare disorder; hence, only a few patients could have been included in the Parkinson’s disease GWAS. In addition, misdiagnosis is unlikely to have led to the association of Parkinson’s disease with oligodendrocytes. Indeed, we found a high genetic correlation between self-reported diagnosis from the 23andMe cohort and a previous GWAS of clinically-ascertained Parkinson’s disease 54.

We did not find an association of oligodendrocytes with Parkinsonism for genes affected by rare variants. This result may reflect etiological differences between sporadic and familial forms of the disease or low statistical power. Prior evidence has suggested an involvement of oligodendrocytes in Parkinson’s disease. For example, α-synuclein-containing inclusions have been reported in oligodendrocytes in Parkinson’s disease brains 55. These inclusions (“coiled bodies”) are typically found throughout the brainstem nuclei and fiber tracts 56. Although the presence of coiled bodies in oligodendrocytes is a common, specific, and well-documented neuropathological feature of Parkinson’s disease, the importance of this cell type and its early involvement in disease has not been fully recognized. Our findings suggest that alterations in oligodendrocytes occur at an early stage of disease, which precedes neurodegeneration in the substantia nigra, arguing for a key role of this cell type in Parkinson’s disease etiology.

Methods

GWAS results

Our goal was to use GWAS results to identify relevant tissues and cell types. Our primary focus was human phenotypes whose etiopathology is based in the central nervous system. We thus obtained 18 sets of GWAS summary statistics from European samples for brain-related complex traits. These were selected because they had at least one genome-wide significant association (as of 2018; e.g., Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, and IQ). For comparison, we included GWAS summary statistics for 8 diseases and traits with large sample sizes whose etiopathology is not rooted in the central nervous system (e.g., type 2 diabetes). The selection of these conditions allowed contrasts of tissues and cells highlighted by our primary interest in brain phenotypes with non-brain traits.

The phenotypes were: schizophrenia 1, educational attainment 2, intelligence 14, body mass index 4, bipolar disorder 57, neuroticism 3, major depressive disorder 58, age at menarche 59, autism 60, migraine 61, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 62, ADHD 63, Alzheimer’s disease 21, age at menopause 64, coronary artery disease 65, height 4, hemoglobin A1c 66, hippocampal volume 67, inflammatory bowel disease 68, intracranial volume 69, stroke 70, type 2 diabetes mellitus 71, type 2 diabetes adjusted for BMI 71, waist-hip ratio adjusted for BMI 72, and anorexia nervosa 73.

For Parkinson’s disease, we performed an inverse variance-weighted meta-analysis 74 using summary statistics from Nalls et al. 54 (9,581 cases, 33,245 controls) and summary statistics from 23andMe (12,657 cases, 941,588 controls). We found a very high genetic correlation (rg) 75 between results from these cohorts (rg=0.87, s.e=0.068) with little evidence of sample overlap (LDSC bivariate intercept=0.0288, s.e=0.0066). The P-values from the meta-analysis strongly deviated from the expected (Supplementary Fig. 8) but was consistent with polygenicity (LDSC intercept=1.0048, s.e=0.008) rather than uncontrolled inflation 75. In this new meta-analysis, we identified 61 independent loci associated with Parkinson’s disease (49 reported previously 17 and 12 novel) (Supplementary Fig. 9). The 10,000 most associated SNPs from the 23andMe cohort are available in Supplementary Table 12.

Gene expression data

We collected publicly available single-cell RNA-seq data from different studies. The core dataset of our analysis is a study that sampled more than 500K single cells from the entire mouse nervous system (19 regions) and identified 39 broad categories (level 4) and 265 refined cell types (level 5) 24. The 39 cell types expressed a median of 16417 genes, had a median UMI total count of ~8.6M and summed the expression of a median of 1501 single cells (Supplementary Table 13). The replication datasets were: 1) a mouse study that sampled 690K single cells from 9 brain regions (frontal cortex, striatum, globus pallidus externus/nucleus basalis, thalamus, hippocampus, posterior cortex, entopeduncular nucleus/subthalamic nucleus, substantia nigra/ventral tegmental area, and cerebellum) and identified 565 cell types 76 (note that we averaged the UMI counts by broad categories of cell type in each brain region, resulting in 88 different cell types); 2) our prior mouse study of ~10K cells from 5 different brain regions (and samples enriched for oligodendrocytes, dopaminergic neurons, serotonergic neurons and cortical parvalbuminergic interneurons) that identified 24 broad categories and 149 refined cell types 11; 3) a study that sampled 19,550 nuclei from frozen adult human post-mortem hippocampus and prefrontal cortex and identified 16 cell types 36; 4) a study that generated 36,166 single-nuclei expression measurements (after quality control) from the human visual cortex, frontal cortex and cerebellum 37. We also obtained bulk tissues RNA-seq gene expression data from 53 tissues from the GTEx consortium 7 (v8, median across samples).

Gene expression data processing

All datasets were processed uniformly. First we computed the mean expression for each gene in each cell type from the single-cell expression data (if this statistics was not provided by the authors). We used the pre-computed median expression across individuals for the GTEx dataset and excluded tissues that were not sampled in at least 100 individuals, non-natural tissues (e.g. EBV-transformed lymphocytes) and testis (outlier using hierarchical clustering). We then averaged the expression of tissues by organ (with the exception of brain tissues) resulting in gene expression profiles of a total of 37 tissues. For all datasets, we filtered out any genes with non-unique names, genes not expressed in any cell types, non-protein coding genes, and, for mouse datasets, genes that had no expert curated 1:1 orthologs between mouse and human (Mouse Genome Informatics, The Jackson laboratory, version 11/22/2016). Gene expression was then scaled to a total of 1M UMIs (or transcript per million (TPM)) for each cell type/tissue. We then calculated a metric of gene expression specificity by dividing the expression of each gene in each cell type by the total expression of that gene in all cell types, leading to values ranging from 0 to 1 for each gene (0: meaning that the gene is not expressed in that cell type, 0.6: that 60% of the total expression of that gene is performed in that cell type, 1: that 100% of the expression of that gene is performed in that cell type). The top 10% most specific genes (Supplementary Table 14,15) in each tissue/cell type partially overlapped for related tissues/cell types, did not overlap for unrelated tissue/cell types and allowed to cluster related tissues/cell types as expected (Supplementary Fig. 10,11).

MAGMA primary and conditional analyses

MAGMA (v1.06b) 18 is a software for gene-set enrichment analysis using GWAS summary statistics. Briefly, MAGMA computes a gene-level association statistic by averaging P-values of SNPs located around a gene (taking into account LD structure). The gene-level association statistic is then transformed to a Z-value. MAGMA can then be used to test whether a gene set is a predictor of the gene-level association statistic of the trait (Z-value) in a linear regression framework. MAGMA accounts for a number of important covariates such as gene size, gene density, mean sample size for tested SNPs per gene, the inverse of the minor allele counts per gene and the log of these metrics.

For each GWAS summary statistics, we excluded any SNPs with INFO score <0.6, with MAF < 1% or with estimated odds ratio > 25 or smaller than 1/25, the MHC region (chr6:25-34 Mb) for all GWAS and the APOE region (chr19:45020859–45844508) for the Alzheimer’s GWAS. We set a window of 35kb upstream to 10kb downstream of the gene coordinates to compute gene-level association statistics and used the European reference panel from the phase 3 of the 1000 genomes project 77 as the reference population. For each trait, we then used MAGMA to test whether the 10% most specific gene in each tissue/cell type was associated with gene-level genetic association with the trait. Only genes with at least 1TPM or 1 UMI per million in the tested cell type were used for this analysis. The significance level of the different cell types was highly correlated with the effect size of the cell type (Supplementary Fig. 12) with values ranging between 0.999 and 1 across the 18 brain related traits in the Zeisel et al. dataset 24. The significance threshold was set to a 5% false discovery rate across all tissues/cell types and traits within each dataset.

MAGMA can also perform conditional analyses given its linear regression framework. We used MAGMA to test whether cell types were associated with a specific trait conditioning on the gene-level genetic association of another trait (Z-value from MAGMA .out file) or to look for associations of cell types conditioning on the 10% most specific genes from other cell types by adding these variables as covariate in the model.

To test whether MAGMA was well-calibrated, we randomly permuted the gene labels of the schizophrenia gene-level association statistic file a thousand times. We then looked for association between the 10% most specific genes in each cell type and the randomized gene-level schizophrenia association statistics. We observed that MAGMA was slightly conservative with less than 5% of the random samplings having a P-value <0.05 (Supplementary Fig. 13).

We also evaluated the effect of varying window sizes (for the SNPs to gene assignment step of MAGMA) on the schizophrenia cell type associations strength (-log10(P)). We observed strong Pearson correlations in cell type associations strength (-log10(P)) across the different window sizes tested (Supplementary Fig. 14). Our selected window size (35kb upstream to 10 kb downstream) had Pearson correlations ranging from 0.94 to 0.98 with the other window sizes, indicating that our results are robust to this parameter.

In a recent paper, Watanabe et al. 78 introduced a different methodology to test for cell type – complex trait association based on MAGMA. Their proposed methodology tests for a positive relationship between gene expression levels and gene-level genetic associations with a complex trait (using all genes). Their method uses the average expression of each gene in all cell types in the dataset as a covariate. We examined the method of Watanabe et al. in detail, and decided against its use for multiple reasons.

First, Watanabe et al. hypothesize that genes with higher levels of expression should be more associated with a trait. In extended discussions among our team (which include multiple neuroscientists), we have strong reservations about the appropriateness and biological meaningfulness of this hypothesis; it is a strong requirement and is at odds with decades of neuroscience research where molecules expressed a low levels can have profound biological impact. For instance, many cell-type specific genes that are disease relevant are expressed at moderate levels (e.g., Drd2 is in the 10% most specific genes in telencephalon projecting inhibitory neurons but in the bottom 30% of expression levels). Our method does not make this hypothesis.

Second, the method of Watanabe et al. corrects for the average expression of all cell types in a dataset. This practice is, in our view, problematic as it necessarily forces dependence on the composition of a scRNA-seq dataset. For instance, if a dataset consists mostly of neurons, this amounts to correcting for neuronal expression and necessarily erodes power to detect trait enrichment in neurons. Alternatively, if a dataset is composed mostly of non-neuronal cells, this will impacts the detection of enrichment in non-neuronal cells.

Third, preliminary results indicate that the method of Watanabe et al. is sensitive to scaling. As different cell types express different numbers of genes, scaling to the same total read counts affects the average gene expression across cell types (which they use as a covariate), leading to different results with different choices of scaling factors (e.g., scaling to 10k vs 1 million reads). Our method is not liable to this issue.

LD score regression analysis

We used partitioned LD score regression 79 to test whether the top 10% most specific genes of each cell type (based on our specificity metric described above) were enriched in heritability for the diverse traits. Only genes with at least 1TPM or 1 UMI per million in the tested cell type were used for this analysis. In order to capture most regulatory elements that could contribute to the effect of the region on the trait, we extended the gene coordinates by 100kb upstream and by 100kb downstream of each gene as previously12. SNPs located in 100kb regions surrounding the top 10% most specific genes in each cell type were added to the baseline model (consisting of 53 different annotations) independently for each cell type (one file for each cell type). We then selected the coefficient z-score p-value as a measure of the association of the cell type with the traits. The significance threshold was set to a 5% false discovery rate across all tissues/cell types and traits within each dataset. All plots show the mean -log10(P) of partitioned LDscore regression and MAGMA. All results for MAGMA or LDSC are available in supplementary data files.

We evaluated the effect of varying window sizes and varying the percentage of most specific genes on the schizophrenia cell type associations strength (-log10P). We observed strong Pearson correlations in cell type associations strength (-log10P) across the different percentage and window sizes tested (Supplementary Fig. 15). Our selected window size (100 kb upstream to 100 kb downstream, top 10% most specific genes) had Pearson correlations ranging from 0.96 to 1 with the other window sizes and percentage, indicating that our results are robust to these parameters.

MAGMA vs LDSC ranking

In order to test whether the cell type ranking obtained using MAGMA and LDSC in the Zeisel et al. dataset 24 were similar, we computed the Spearman rank correlation of the cell types association strength (-log10P) between the two methods for each complex trait. The Spearman rank correlation was strongly correlated with λGC (a measure of the deviation of the GWAS test statistics from the expected) (Spearman correlation = 0.89) (Supplementary Fig. 16) and with the average number of cell types below our stringent significance threshold (Spearman correlation = 0.92), indicating that the overall ranking of the cell types is very similar between the two methods, provided that the GWAS is well powered (Supplementary Fig. 17). In addition, we found that λGC was strongly correlated with the strength of association of the top tissue (-log10P) (Spearman correlation = 0.88) (Supplementary Fig. 18), as well as with the effect size (beta) of the top tissue (Spearman correlation = 0.9), indicating that cell type – trait associations are stronger for well powered GWAS. The significance level (-log10P) was also strongly correlated with the effect size (Spearman correlation = 0.996) (Supplementary Fig. 18) for the top cell type of each trait.

Dendritic depletion analysis

This analysis was performed as previously described 11. In brief, all datasets were reduced to a set of six common cell types: pyramidal neurons, interneurons, astrocytes, microglia and oligodendrocyte precursors. Specificity was recalculated using only these six cell types. Comparisons were then made between pairs of datasets (denoted in the graph with the format ‘X versus Y’). The difference in specificity for a set of dendrite enriched genes is calculated between the datasets. Differences in specificity are also calculated for random sets of genes selected from the background gene set. The probability and z-score for the difference in specificity for the dendritic genes is thus estimated. Dendritically enriched transcripts were obtained from Supplementary Table 10 of Cajigas et al. 80. For the KI dataset 11, we used S1 pyramidal neurons. For the Zeisel 2018 dataset 24 we used all ACTE* cells as astrocytes, TEGLU* as pyramidal neurons, TEINH* as interneurons, OPC as oligodendrocyte precursors and MGL* as microglia. For the Saunders dataset 35, we used all Neuron.Slc17a7 cellt ypes from FC, HC or PC as pyramidal neurons; all Neuron.Gad1Gad2 cell types from FC, HC or PC as interneurons; Polydendrocye as OPCs; Astrocyte as astrocytes, and Microglia as microglia. The Lake datasets both came from a single publication 37 which had data from frontal cortex, visual cortex and cerebellum. The cerebellum data was not used here. Data from frontal and visual cortices were analyzed separately. All other datasets were used as described in our previous publication 11. The code and data for this analysis are available as an R package (see code availability below).

GO term enrichment

We tested whether genes that were highly specific to a trait-associated cell type (top 20% in a given cell type) AND highly associated with the genetics of the traits (top 10% MAGMA gene-level genetic association) were enriched in biological functions using the topGO R package 81. As background, we used genes that were highly specific to the cell type (top 20%) OR highly associated with the trait (top 10% MAGMA gene-level genetic association).

Parkinson’s disease rare variant enrichments

We searched the literature for genes associated with Parkinsonism on the basis of rare and familial mutations. We found 66 genes (listed in Supplementary Table 10). We used linear regression to test whether the z-scaled specificity metric (per cell type) of the 66 genes were greater than 0 in the different cell types.

Parkinson’s disease post-mortem transcriptomes

The Moran dataset 39 was obtained from GEO (accession GSE8397). Processing of the U133a and U133b Cel files was done separately. The data was read in using the ReadAffy function from the R affy package 82, then Robust Multi-array Averaging (RMA) was applied. The U133a and U133b array expression data were merged after applying RMA. Probe annotations and mapping to HGNC symbols was done using the biomaRt R package 83. Differential expression analysis was performed using limma 84 taking age and gender as covariates. The Lesnick dataset 38 was obtained from GEO (accession GSE7621). Data was processed as for the Moran dataset: however, age was not available to use as a covariate. The Disjkstra dataset 42 was obtained from GEO (accession GSE49036) and processed as above: the gender and RIN values were used as covariates. As the transcriptome datasets measured gene expression in the substantia nigra, we only kept cell types that are present in the substantia nigra or ventral midbrain for our EWCE 10 analysis. We computed a new specificity matrix based on the substantia nigra or ventral midbrain cells from the Zeisel dataset (level 5) using EWCE 10. The EWCE analysis was performed on the 500 most up or down regulated genes using 10,000 bootstrapping replicates.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Enrichment of immune genes in GTEx tissues.

Enrichment pvalues of genes belonging to the GO term “Immune System Process” in the 10% most specific genes in each tissue. The one-sided pvalues were computed using linear regression, testing whether the average specificity metric of the gene set was higher than 0 (z-scaled specificity metrics per tissue). The GO term was selected because it is the most associated with inflammatory bowel disease using MAGMA.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Associations of brain related traits with cell types from the entire mouse nervous system.

Associations of the top 15 most associated cell types are shown. The mean strength of association (-log10P) of MAGMA and LDSC is shown and the bar color indicates whether the cell type is significantly associated with both methods, one method or none (significance threshold: 5% false discovery rate).

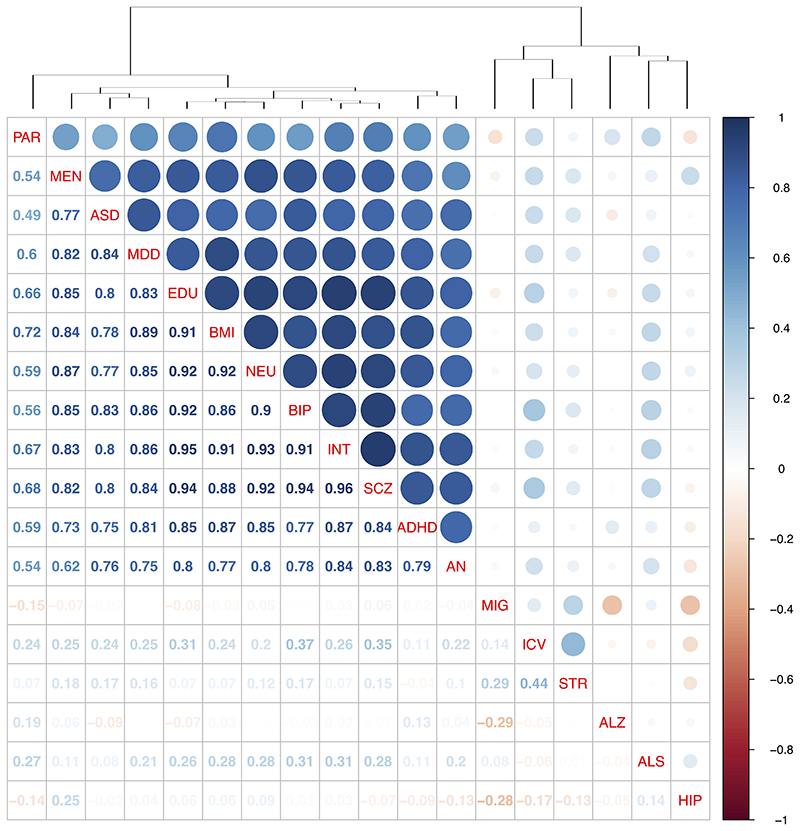

Extended Data Fig. 3. Correlation in cell type associations across traits.

The Spearman rank correlations between the cell types associations across traits (-log10P) are shown. SCZ (schizophrenia), EDU (educational attainment), INT (intelligence), BMI (body mass index), BIP (bipolar disorder), NEU (neuroticism), PAR (Parkinson’s disease), MDD (Major depressive disorder), MEN (age at menarche), ICV (intracranial volume), ASD (autism spectrum disorder), STR (stroke), AN (anorexia nervosa), MIG (migraine), ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), ALZ (Alzheimer’s disease), HIP (hippocampal volume).

Extended Data Fig. 4. Associations of brain related traits with neurons from the central nervous system.

Associations of the 15 most associated neurons from the central nervous system (CNS) are shown. The specificity metrics were computed only using neurons from the CNS. The mean strength of association (-log10P) of MAGMA and LDSC is shown and the bar color indicates whether the cell type is significantly associated with both methods, one method or none (significance threshold: 5% false discovery rate).

Extended Data Fig. 5. Associations of cell types with schizophrenia/cognitive traits conditioning on gene-level genetic association of cognitive traits/schizophrenia.

MAGMA association strength for each cell type before and after conditioning on gene-level genetic association for another trait. The black bar represents the significance threshold (5% false discovery rate). SCZ (schizophrenia), INT (intelligence), EDU (educational attainment).

Extended Data Fig. 6. Replication of cell type – trait associations in 88 cell types from 9 different brain regions.

The mean strength of association (-log10P) of MAGMA and LDSC is shown for the 15 top cell types for each trait. The bar color indicates whether the cell type is significantly associated with both methods, one method or none (significance threshold: 5% false discovery rate).

Extended Data Fig. 7. Correlation in cell type associations across traits in a replication data set (88 cell types, 9 brain regions).

Spearman rank correlations for cell types associations (-log10P) across traits are shown. SCZ (schizophrenia), EDU (educational attainment), INT (intelligence), BMI (body mass index), BIP (bipolar disorder), NEU (neuroticism), PAR (Parkinson’s disease), MDD (Major depressive disorder), MEN (age at menarche), ICV (intracranial volume), ASD (autism spectrum disorder), STR (stroke), AN (anorexia nervosa), MIG (migraine), ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), ALZ (Alzheimer’s disease), HIP (hippocampal volume).

Extended Data Fig. 8. Associations of brain related traits with neurons from 9 different brain regions.

Trait – neuron association are shown for neurons of the 9 different brain regions. The specificity metrics were computed only using neurons. The mean strength of association (-log10P) of MAGMA and LDSC is shown and the bar color indicates whether the cell type is significantly associated with both methods, one method or none (significance threshold: 5% false discovery rate).

Extended Data Fig. 9. Top associated cell types with brain related traits among 24 cell types from 5 different brain regions.

The mean strength of association (-log10P) of MAGMA and LDSC is shown for the 15 top cell types for each trait. The bar color indicates whether the cell type is significantly associated with both methods, one method or none (significance threshold: 5% false discovery rate).

Extended Data Fig. 10. Top associated neurons with brain related traits among 16 neurons from 5 different brain regions.

The specificity metrics were computed only using neurons. The mean strength of association (-log10P) of MAGMA and LDSC is shown for the top 15 cell types for each trait. The bar color indicates whether the cell type is significantly associated with both methods, one method or none (significance threshold= 5% false discovery rate).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J. Bryois was funded by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (P400PB_180792). N.G.S. was supported by the Wellcome Trust (108726/Z/15/Z). N. Skene and L. Brueggeman performed part of the work at the Systems Genetics of Neurodegeneration summer school funded by BMBF as part of the e:Med program (FKZ 01ZX1704). J. Hjerling-Leffler was funded by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, award 2014-3863), StratNeuro, the Wellcome Trust (108726/Z/15/Z) and the Swedish Brain Foundation (Hjärnfonden). PFS was supported by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, award D0886501), the Horizon 2020 Program of the European Union (COSYN, RIA grant agreement n° 610307), and US NIMH (U01 MH109528 and R01 MH077139). K. Heilbron was supported by The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research (grant MJFF12737). E. Arenas was supported by the Swedish Research Council (VR 2016-01526), Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (SLA SB16-0065), Karolinska Institutet (SFO Strat. Regen., Senior grant 2018), Cancerfonden (CAN 2016/572), Hjärnfonden (FO2017-0059) and Chen Zuckeberg Initiative: Neurodegeneration Challenge Network (2018-191929-5022). C. Bulik acknowledges funding from the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, award: 538-2013-8864) and the Klarman Family Foundation. This work is supported by the UK Dementia Research Institute which receives its funding from UK DRI Ltd, funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Alzheimer’s Society and Alzheimer’s Research UK. We thank the research participants from 23andMe and other cohorts for their contribution to this study.

Footnotes

Author contributions

J.B., N.G.S., J.H.-L. and P.F.S. designed the study, wrote and reviewed the manuscript; J.B performed the analyses pertaining to Fig. 1–4, Extended Data Figure 1–10, Supplementary Fig. 1–5,7–20, Supplementary Table 1–9,12–17; N.G.S performed the analyses pertaining to Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 10,11; T.F.H, L.J.A.K. and the I.H.G.C provided the migraine GWAS summary statistics; H.J.W., the E.D.W.G.P.G.C, G.B. and C.M.B performed the anorexia GWAS; Z.L. contributed to the revision of the manuscript, The 23andMe R.T. provided GWAS summary statistics for Parkinson’s disease in the 23andMe cohort. L.B. contributed to the post-mortem differential expression analysis (Fig. 5); E.A. and K.H. provided expert knowledge on Parkinson’s disease and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

P.F.S. reports the following potentially competing financial interests. Current: Lundbeck (advisory committee, grant recipient). Past three years: Pfizer (scientific advisory board), Element Genomics (consultation fee), and Roche (speaker reimbursement). C.M. Bulik reports: Shire (grant recipient, Scientific Advisory Board member); Pearson and Walker (author, royalty recipient).

Contributor Information

Eating Disorders Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium:

Roger Adan, Lars Alfredsson, Tetsuya Ando, Ole Andreassen, Jessica Baker, Andrew Bergen, Wade Berrettini, Andreas Birgegård, Joseph Boden, Ilka Boehm, Claudette Boni, Vesna Boraska Perica, Harry Brandt, Gerome Breen, Julien Bryois, Katharina Buehren, Cynthia Bulik, Roland Burghardt, Matteo Cassina, Sven Cichon, Maurizio Clementi, Jonathan Coleman, Roger Cone, Philippe Courtet, Steven Crawford, Scott Crow, James Crowley, Unna Danner, Oliver Davis, Martina de Zwaan, George Dedoussis, Daniela Degortes, Janiece DeSocio, Danielle Dick, Dimitris Dikeos, Christian Dina, Monika Dmitrzak-Weglarz, Elisa Docampo Martinez, Laramie Duncan, Karin Egberts, Stefan Ehrlich, Geòrgia Escaramís, Tõnu Esko, Xavier Estivill, Anne Farmer, Angela Favaro, Fernando Fernández-Aranda, Manfred Fichter, Krista Fischer, Manuel Föcker, Lenka Foretova, Andreas Forstner, Monica Forzan, Christopher Franklin, Steven Gallinger, Héléna Gaspar, Ina Giegling, Johanna Giuranna, Paola Giusti-Rodríquez, Fragiskos Gonidakis, Scott Gordon, Philip Gorwood, Monica Gratacos Mayora, Jakob Grove, Sébastien Guillaume, Yiran Guo, Hakon Hakonarson, Katherine Halmi, Ken Hanscombe, Konstantinos Hatzikotoulas, Joanna Hauser, Johannes Hebebrand, Sietske Helder, Anjali Henders, Stefan Herms, Beate Herpertz-Dahlmann, Wolfgang Herzog, Anke Hinney, L. John Horwood, Christopher Hübel, Laura Huckins, James Hudson, Hartmut Imgart, Hidetoshi Inoko, Vladimir Janout, Susana Jiménez-Murcia, Craig Johnson, Jennifer Jordan, Antonio Julià, Anders Juréus, Gursharan Kalsi, Deborah Kaminská, Allan Kaplan, Jaakko Kaprio, Leila Karhunen, Andreas Karwautz, Martien Kas, Walter Kaye, James Kennedy, Martin Kennedy, Anna Keski-Rahkonen, Kirsty Kiezebrink, Youl-Ri Kim, Katherine Kirk, Lars Klareskog, Kelly Klump, Gun Peggy Knudsen, Maria La Via, Mikael Landén, Janne Larsen, Stephanie Le Hellard, Virpi Leppä, Robert Levitan, Dong Li, Paul Lichtenstein, Lisa Lilenfeld, Bochao Danae Lin, Jolanta Lissowska, Jurjen Luykx, Pierre Magistretti, Mario Maj, Katrin Mannik, Sara Marsal, Christian Marshall, Nicholas Martin, Manuel Mattheisen, Morten Mattingsdal, Sara McDevitt, Peter McGuffin, Sarah Medland, Andres Metspalu, Ingrid Meulenbelt, Nadia Micali, James Mitchell, Karen Mitchell, Palmiero Monteleone, Alessio Maria Monteleone, Grant Montgomery, Preben Bo Mortensen, Melissa Munn-Chernoff, Benedetta Nacmias, Marie Navratilova, Claes Norring, Ioanna Ntalla, Catherine Olsen, Roel Ophoff, Julie O'Toole, Leonid Padyukov, Aarno Palotie, Jacques Pantel, Hana Papezova, Richard Parker, John Pearson, Nancy Pedersen, Liselotte Petersen, Dalila Pinto, Kirstin Purves, Raquel Rabionet, Anu Raevuori, Nicolas Ramoz, Ted Reichborn-Kjennerud, Valdo Ricca, Samuli Ripatti, Stephan Ripke, Franziska Ritschel, Marion Roberts, Alessandro Rotondo, Dan Rujescu, Filip Rybakowski, Paolo Santonastaso, André Scherag, Stephen Scherer, Ulrike Schmidt, Nicholas Schork, Alexandra Schosser, Jochen Seitz, Lenka Slachtova, P. Eline Slagboom, Margarita Slof-Op 't Landt, Agnieszka Slopien, Sandro Sorbi, Michael Strober, Garret Stuber, Patrick Sullivan, Beata Świątkowska, Jin Szatkiewicz, Ioanna Tachmazidou, Elena Tenconi, Laura Thornton, Alfonso Tortorella, Federica Tozzi, Janet Treasure, Artemis Tsitsika, Marta Tyszkiewicz-Nwafor, Konstantinos Tziouvas, Annemarie van Elburg, Eric van Furth, Tracey Wade, Gudrun Wagner, Esther Walton, Hunna Watson, Thomas Werge, David Whiteman, Elisabeth Widen, D. Blake Woodside, Shuyang Yao, Zeynep Yilmaz, Eleftheria Zeggini, Stephanie Zerwas, and Stephan Zipfel

International Headache Genetics Consortium:

Verneri Anttila, Ville Artto, Andrea Carmine Belin, Irene de Boer, Dorret I Boomsma, Sigrid Børte, Daniel I Chasman, Lynn Cherkas, Anne Francke Christensen, Bru Cormand, Ester Cuenca-Leon, George Davey-Smith, Martin Dichgans, Cornelia van Duijn, Tonu Esko, Ann Louise Esserlind, Michel Ferrari, Rune R. Frants, Tobias Freilinger, Nick Furlotte, Padhraig Gormley, Lyn Griffiths, Eija Hamalainen, Thomas Folkmann Hansen, Marjo Hiekkala, M Arfan Ikram, Andres Ingason, Marjo-Riitta Järvelin, Risto Kajanne, Mikko Kallela, Jaakko Kaprio, Mari Kaunisto, Lisette J.A. Kogelman, Christian Kubisch, Mitja Kurki, Tobias Kurth, Lenore Launer, Terho Lehtimaki, Davor Lessel, Lannie Ligthart, Nadia Litterman, Arn van den Maagdenberg, Alfons Macaya, Rainer Malik, Massimo Mangino, George McMahon, Bertram Muller-Myhsok, Benjamin M. Neale, Carrie Northover, Dale R. Nyholt, Jes Olesen, Aarno Palotie, Priit Palta, Linda Pedersen, Nancy Pedersen, Danielle Posthuma, Patricia Pozo-Rosich, Alice Pressman, Olli Raitakari, Markus Schürks, Celia Sintas, Kari Stefansson, Hreinn Stefansson, Stacy Steinberg, David Strachan, Gisela Terwindt, Marta Vila-Pueyo, Maija Wessman, Bendik S. Winsvold, Huiying Zhao, and John Anker Zwart

23andMe Research Team:

Michelle Agee, Babak Alipanahi, Adam Auton, Robert Bell, Katarzyna Bryc, Sarah Elson, Pierre Fontanillas, Nicholas Furlotte, Karl Heilbron, David Hinds, Karen Huber, Aaron Kleinman, Nadia Litterman, Jennifer McCreight, Matthew McIntyre, Joanna Mountain, Elizabeth Noblin, Carrie Northover, Steven Pitts, J. Sathirapongsasuti, Olga Sazonova, Janie Shelton, Suyash Shringarpure, Chao Tian, Joyce Tung, Vladimir Vacic, and Catherine Wilson

Data availability

All single-cell expression data are publicly available. Most summary statistics used in this study are publicly available. The migraine GWAS can be obtained by contacting the authors61. The full Parkinson’s disease summary statistics from 23andMe can be obtained under an agreement that protects the privacy of 23andMe research participants (https://research.23andme.com/collaborate/#publication). The 10,000 most associated SNPs from the 23andMe cohort are available in Supplementary Table 12.

Code availability

The code used to generate these results is available at: https://github.com/jbryois/scRNA_disease. An R package for performing cell type enrichments using magma is also available from: https://github.com/NathanSkene/MAGMA_Celltyping.

References

- 1.Pardiñas AF, et al. Common schizophrenia alleles are enriched in mutation-intolerant genes and in regions under strong background selection. Nat Genet. 2018;50:381–389. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0059-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JJ, Wedow R, Okbay Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1112–1121. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0147-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagel M, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for neuroticism in 449,484 individuals identifies novel genetic loci and pathways. Nat Genet. 2018;50:920–927. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yengo L, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for height and body mass index in ∼700000 individuals of European ancestry. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27:3641–3649. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maurano MT, et al. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science (80-) 2012;337:1190–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.1222794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akbarian S, et al. The PsychENCODE project. Nature Neuroscience. 2015;18:1707–1712. doi: 10.1038/nn.4156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aguet F, et al. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature. 2017;550:204–213. doi: 10.1038/nature24277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium et al. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015;518:317–329. doi: 10.1038/nature14248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ongen H, et al. Estimating the causal tissues for complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1676–1683. doi: 10.1038/ng.3981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skene NG, Grant SGN. Identification of vulnerable cell types in major brain disorders using single cell transcriptomes and expression weighted cell type enrichment. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skene NG, et al. Genetic identification of brain cell types underlying schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2018;50:825–833. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0129-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finucane HK, et al. Heritability enrichment of specifically expressed genes identifies disease-relevant tissues and cell types. Nat Genet. 2018;50:621–629. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0081-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calderon D, et al. Inferring relevant cell types for complex traits by using single-cell gene expression. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101:686–699. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savage JE, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis in 269,867 individuals identifies new genetic and functional links to intelligence. Nat Genet. 2018;50:912–919. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0152-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman JRI, et al. Biological annotation of genetic loci associated with intelligence in a meta-analysis of 87,740 individuals. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:182–197. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0040-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jansen IE, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nat Genet. 2019;51:404–413. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0311-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nalls MA, et al. Identification of novel risk loci, causal insights, and heritable risk for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:1091–1102. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30320-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Leeuw CA, Mooij JM, Heskes T, Posthuma D. MAGMA: Generalized Gene-Set Analysis of GWAS Data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finucane HK, et al. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1228–1235. doi: 10.1038/ng.3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jevtic S, Sengar AS, Salter MW, McLaurin JA. The role of the immune system in Alzheimer disease: Etiology and treatment. Ageing Research Reviews. 2017;40:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansen IE, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nature Genetics. 2019;51:404–413. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0311-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunkle BW, et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet. 2019;51:414–430. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0358-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Leary DH, et al. Carotid-Artery Intima and Media Thickness as a Risk Factor for Myocardial Infarction and Stroke in Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:14–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeisel A, et al. Molecular architecture of the mouse nervous system. Cell. 2018;174:999–1014.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anttila V, et al. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science (80-) 2018;360 doi: 10.1126/science.aap8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keren-Shaul H, et al. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2017;169 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braak H, et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sulzer D, Surmeier DJ. Neuronal vulnerability, pathogenesis, and Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2013;28:41–50. doi: 10.1002/mds.25095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poewe W, et al. Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3:17013. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halliday GM, et al. Neuropathology of immunohistochemically identified brainstem neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:373–385. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delaville C, de Deurwaerdère P, Benazzouz A. Noradrenaline and Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 2011 doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rinne JO, Ma SY, Lee MS, Collan Y, Röyttä M. Loss of cholinergic neurons in the pedunculopontine nucleus in Parkinson’s disease is related to disability of the patients. Park Relat Disord. 2008;14:553–557. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braak H, Rüb U, Gai WP, Del Tredici K. Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: Possible routes by which vulnerable neuronal types may be subject to neuroinvasion by an unknown pathogen. J Neural Transm. 2003;110:517–536. doi: 10.1007/s00702-002-0808-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liddle RA. Parkinson’s disease from the gut. Brain Research. 2018;1693:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saunders A, et al. Molecular diversity and specializations among the cells of the adult mouse brain. Cell. 2018;174:1015–1030.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Habib N, et al. Massively parallel single-nucleus RNA-seq with DroNc-seq. Nat Methods. 2017;14:955. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lake BB, et al. Integrative single-cell analysis of transcriptional and epigenetic states in the human adult brain. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:70–80. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lesnick TG, et al. A genomic pathway approach to a complex disease: Axon guidance and Parkinson disease. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:0984–0995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moran LB, et al. Whole genome expression profiling of the medial and lateral substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Neurogenetics. 2006;7:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10048-005-0020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kannarkat GT, Boss JM, Tansey MG. The role of innate and adaptive immunity in parkinson’s disease. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. 2013;3:493–514. doi: 10.3233/JPD-130250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gagliano SA, et al. Genomics implicates adaptive and innate immunity in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3:924–933. doi: 10.1002/acn3.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dijkstra AA, et al. Evidence for immune response, axonal dysfunction and reduced endocytosis in the substantia nigra in early stage Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lake BB, et al. Neuronal subtypes and diversity revealed by single-nucleus RNA sequencing of the human brain. Science (80-) 2016;352:1586–1590. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sathyamurthy A, et al. Massively Parallel Single Nucleus Transcriptional Profiling Defines Spinal Cord Neurons and Their Activity during Behavior. Cell Rep. 2018;22:2216–2225. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lake BB, et al. A comparative strategy for single-nucleus and single-cell transcriptomes confirms accuracy in predicted cell-type expression from nuclear RNA. Sci Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04426-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caspi A, et al. The p factor: One general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2:119–137. doi: 10.1177/2167702613497473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sullivan PF, Geschwind DH. Defining the Genetic, Genomic, Cellular, and Diagnostic Architectures of Psychiatric Disorders. Cell. 2019;177:162–183. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reynolds RH, et al. Moving beyond neurons: the role of cell type-specific gene regulation in Parkinson’s disease heritability. npj Park Dis. 2019;5:6. doi: 10.1038/s41531-019-0076-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singaram C, et al. Dopaminergic defect of enteric nervous system in Parkinson’s disease patients with chronic constipation. Lancet. 1995;346:861–864. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92707-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H, Takeda S, Ohama E, Ikuta F. Lewy Bodies in the Enteric Nervous System in Parkinson’s Disease. Arch Histol Cytol. 1989;52:191–194. doi: 10.1679/aohc.52.suppl_191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stokholm MG, Danielsen EH, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Borghammer P. Pathological α-synuclein in gastrointestinal tissues from prodromal Parkinson disease patients. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:940–949. doi: 10.1002/ana.24648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Svensson E, et al. Vagotomy and subsequent risk of Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:522–529. doi: 10.1002/ana.24448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gilman S, et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology. 2008;71:670–676. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000324625.00404.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nalls MA, et al. Large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies six new risk loci for Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46:989–993. doi: 10.1038/ng.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wakabayashi K, Hayashi S, Yoshimoto M, Kudo H, Takahashi H. NACP/α-synuclein-positive filamentous inclusions in astrocytes and oligodendrocytes of Parkinson’s disease brains. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;99:14–20. doi: 10.1007/pl00007400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seidel K, et al. The brainstem pathologies of Parkinson’s disease and dementia with lewy bodies. Brain Pathol. 2015;25:121–135. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stahl EA, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 30 loci associated with bipolar disorder. Nat Genet. 2019;51:793–803. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0397-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wray N, Sullivan PF, PGC, M. D. D. W. G. of the Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat Genet. 2018;50:668–681. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0090-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perry JRB, et al. Parent-of-origin-specific allelic associations among 106 genomic loci for age at menarche. Nature. 2014;514:92–97. doi: 10.1038/nature13545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grove J, et al. Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Genet. 2019;51:431–444. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0344-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gormley P, et al. Meta-analysis of 375,000 individuals identifies 38 susceptibility loci for migraine. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1296. doi: 10.1038/ng1016-1296c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Rheenen W, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify new risk variants and the genetic architecture of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1043–1048. doi: 10.1038/ng.3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Demontis D, et al. Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Genet. 2019;51:63–75. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0269-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Day FR, et al. Large-scale genomic analyses link reproductive aging to hypothalamic signaling, breast cancer susceptibility and BRCA1-mediated DNA repair. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1294–1303. doi: 10.1038/ng.3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]