Abstract

Cyclophilin A (CypA) is a ubiquitous cis-trans-prolyl isomerase with key roles in immunity and viral infection. CypA suppresses T-cell activation through cyclosporine (Cs) complexation and is required for effective HIV-1 replication in host cells. We show that CypA is acetylated in diverse human cell lines and use a synthetically evolved acetyl-lysyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNACUA pair to produce recombinant acetylated CypA in E. coli. We determine atomic resolution structures of acetylated CypA and its complexes with Cs and HIV-1 capsid. Acetylation dramatically inhibits CypA catalysis of cis to trans isomerisation and stabilises cis rather than trans forms of the HIV-1 capsid. Furthermore, CypA acetylation antagonizes the immunosuppressive effects of Cs, by inhibiting the sequential steps of Cs binding and calcineurin inhibition. Our results reveal that acetylation regulates key functions of CypA in immunity and viral infection and provide a general set of mechanisms by which acetylation modulates interactions to regulate cell function.

Introduction

Cyclophilins/Immunophilins are peptidyl-prolyl-cis/trans isomerases found in all kingdoms of life and all tissues. Cyclophilin A (CypA), the archetypal cyclophilin, is central to protein folding1, signal transduction2, trafficking3, receptor assembly4, cell cycle regulation5 and stress response and has an expanding catalog of roles6. Two of CypA’s most important roles in human health are in controlling immunosuppression and viral infection. CypA is the target of the widely-used immunosuppressive, cyclosporine (Cs, 1). The complex formed by CypA and Cs binds to and allosterically inhibits calcineurin, a protein phosphatase, leading to suppression of the T-cell mediated immune response via an IL-2 mediated down-regulation of T-cell activation7. CypA is also an essential host protein in the efficient replication of a number of viruses including vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)5, severe acute respiratory syndrome virus (SARS)6, hepatitis C8, vaccinia virus (VV) and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)9,10. During HIV-1 infection, CypA interacts with the capsid protein gag and is packaged into budding HIV-1 virions9,10. Inhibition of CypA by Cs substantially decreases viral titer in human cells11. The importance of CypA in lentiviral replication is underscored by the fact that two different primate species have independently evolved antiviral restriction factors that use a retrotransposed copy of CypA to provide viral targeting12. Despite the importance of CypA in immunosuppression, viral infection, and other key cellular processes the molecular mechanisms by which the varied and critical functions of CypA are regulated remains unclear.

Acetylation of the epsilon amine of specific lysine residues in proteins is a reversible post-translational modification with many diverse roles and a functional importance that rivals phosphorylation13. Acetylation is mediated by acetyl-CoA dependent histone acetyl-transferases14, removed by Zn dependent histone deacetylases or NAD dependent sirtuins15 and specifically recognized by bromo-domain containing proteins16. Recent mass spectrometry and immunofluorescence studies demonstrate that hundreds of non-histone proteins are acetylated in mammalian cells17, however the molecular mechanisms by which acetylation may control protein function and effect cellular regulation are largely unknown.

A recent proteomics screen isolated a peptide whose sequence matched CypA but which contained an acetyl-lysine (2) in place of K12517. However, since there are many CypA gene fusions in the genome, the origin of this peptide is ambiguous. Here we show that the free enzyme form of CypA is acetylated in human cells. We produce homogeneously and site-specifically acetylated recombinant CypA using an acetyllysyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNACUA pair that co-translationally directs the incorporation of acetyl-lysine in response to an amber codon18 placed in a CypA gene. This approach allows us to perform structural and biophysical measurements on acetylated CypA for the first time. These results reveal how acetylation modulates key functions of CypA, including suppressing its catalytic activity, cyclosporine binding and calcineurin inhibition and altering its recognition of the HIV-1 capsid. Furthermore, the molecular details of these affects establish a general set of mechanisms by which acetylation can regulate protein activity.

Results

CypA is acetylated in human cells

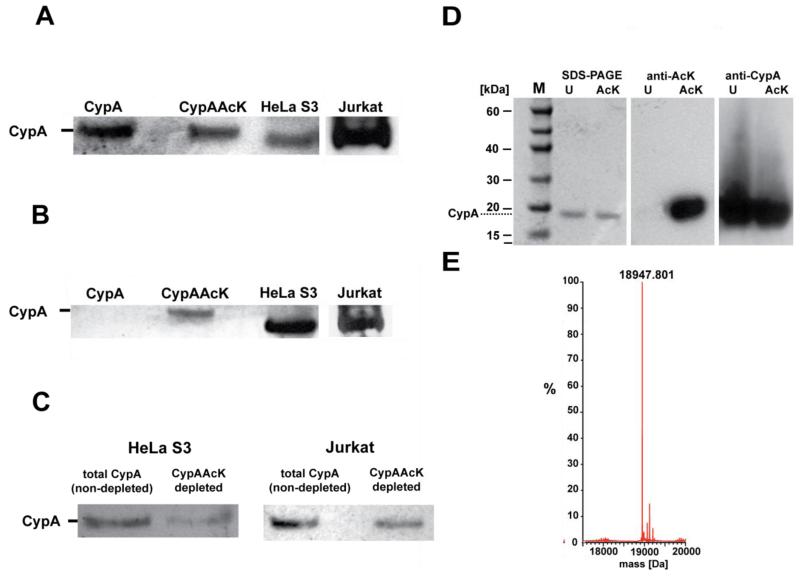

To investigate whether CypA is acetylated in human cells we immunoprecipitated endogenous CypA from HeLa and Jurkat T cells using a CypA specific antibody. Detection by western blot using an anti-CypA antibody demonstrated that endogenous CypA is present in the cell extract (Figure 1a). Detection using an anti-acetyl-lysine antibody showed that this endogenous CypA is acetylated in both HeLa and Jurkat T cells (Figure 1b). Importantly, the anti-acetyl-lysine antibody did not detect the unacetylated control (Figure 1b). These data conclusively demonstrated that CypA is acetylated in human cells, including T cells where CypA mediates its effects on immunosuppresion and HIV-1 infection. To determine the proportion of endogenous CypA that is acetylated in each cell type we performed an immunodepletion experiment. Acetylated CypA was depleted from lysate using an anti-acetyl-lysine antibody bound to protein A sepharose. The depleted material was compared by western blot with an anti-CypA antibody to non-depleted material processed in the absence of the anti-acetyl-lysine antibody (Figure 1c). To obtain a quantitative estimate of the proportion of acetylated CypA, we performed a standardization experiment with varying ratios of acetylated:nonacetylated recombinant protein (Supplementary Figure 1). Using this standardization we estimated that 50% ± 5% of CypA is acetylated in HeLa cells and 38% ± 3% in Jurkat T cells. These results indicated that a substantial proportion of CypA is acetylated in both HeLa and Jurkat T cells. While we expect the proportion of acetylated protein to be regulated in response to stimuli these results demonstrated that the effects of acetylation on CypA are relevant to, and important for, understanding CypA mediated processes.

Figure 1. Homogenous and site-specific incorporation of acetyllysine into CypA.

(a&b) CypA can be immunoprecipitated from HeLa and Jurkat T cells (a) and the acetylated fraction detected by anti-acetyllysine antibody in both cell types (b). Recombinant CypA and CypAAcK are present as controls. (c) Quantification of acetylated CypA in HeLa and Jurkat cells using an immunodepletion approach. Endogenous CypA from cell lysate is depleted with anti-acetyllysine antibody and compared to nondepleted material by western blot with an anti-CypA-antibody. These results show that a substantial proportion of CypA is acetylated in both HeLa and Jurkat cells.

Expression of homogenously K125 acetylated CypA

To determine the consequences of K125 acetylation on CypA structure and function we needed a way of synthesizing large quantities of site-specifically homogeneously acetylated protein. We produced recombinant acetylated CypA (CypAAcK) from E. coli using an evolved orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNACUA pair that co-translationally directs the incorporation of exogenously added acetyllysine into recombinant proteins in response to amber codons placed in their encoding genes18,19. The CypA gene bearing an amber codon in place of the K125 codon was expressed from a T7 promoter in cells bearing acetyl-lysyl-tRNA synthetase and the corresponding amber suppressor tRNA. The cells were supplemented with 10 mM acetlyllysine and 20mM nicotinamide and protein expression induced at log phase. Recombinant acetylated cyclophilin was purified at greater than 10 mg per liter of culture, in the presence of 20 mM nicotinamide to inhibit cobB, an NAD dependent deacetylase present in E. coli. The presence of the acetyl group was confirmed by anti-acetyllysine western blot (Supplementary Figure 2a, and the quantitative incorporation of acetyllysine was further demonstrated by electrospray-ionisation-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS, Supplementary Figure 2b).

Atomic structure of acetylated CypA

Recombinant CypA is most stable in basic buffers between pH 8-8.5, however the acetylated CypA rapidly precipitates under these conditions. By screening a range of pH and salt conditions using absorbance at 320 nm as a measure of aggregation we found that the stability of acetylated CypA increases dramatically in acidic buffers (pH 5.4-6.4). Under mildly acidic conditions acetylated CypA was still soluble at concentrations around 3 mM. This suggested that K125 has a prominent role in surface electrostatics and that its acetylation has a significant impact on CypA behavior. To assess the affect of acetylation on the physicochemistry of CypA we determined the native crystal structure. Acetylated CypA crystallized in two different forms, one in an orthorhombic spacegroup and one in a trigonal spacegroup. We determined the structure of both forms in order to assess crystal packing affects. Crystal contacts are provided in Supplementary Table 1. The structures were refined to 1.2 Å and 1.4 Å respectively, with two copies in the asymmetric unit in the case of the trigonal crystal and a single copy in the orthorhombic crystal. These are the first structures containing a specific, biologically relevant post-translational lysine acetylation. In both CypA structures there is clear density for the acetyllysine side-chain, as evidenced by the omit maps (Figure 2a,b). This further demonstrates the homogeneity of acetyllysine incorporation and shows that the acetyllysine has a well-defined conformation. Finally, both structures and both chains from the trigonal crystal superpose closely with only minimal differences in the extreme N-terminal residues (Figure 2c).

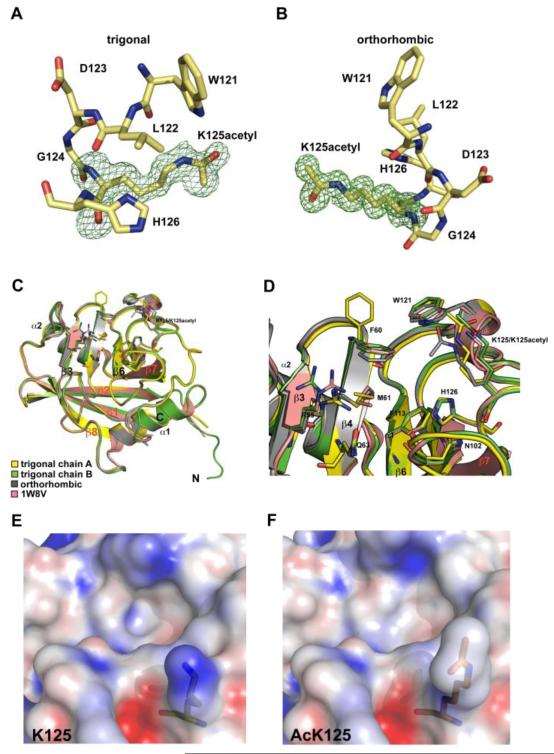

Figure 2. Structure of acetylated CypA.

Omit maps of the acetyllysine density for the trigonal (a) and orthorhombic structures (b) contoured at 1σ. (c&d) Comparison of unacetylated (1W8V) and acetylated CypA structures. There are no significant conformational changes associated with incorporation of the acetyl group. (e&f) Electrostatic surface potential of the active site around K125 as generated by APBS. Blue represents a positive charge and red negative. Scaled from −20 to +20 kT e−1.

The secondary structure of the acetylated CypA superposes closely with the known structure of native cyclophilin, showing that there are no large conformational changes induced by acetylation (Figure 2c&d). Comparison of the active sites reveals differences in only three residues F60, R55 and K125. The F60 side-chain of trigonal chain A is rotated 90° compared to the other structures. This is due to crystal contacts between F60 and its symmetry-related copy. F60, together with M61 and F113, form a hydrophobic core at the base of the substrate binding-pocket. R55 is a key catalytic residue, facilitating catalysis through stabilisation of the proline in the transition state20. Differences in the side-chain orientation of R55 in the acetylated and non-acetylated structures are likely to result from the inherent flexibility required in this region to accommodate diverse CypA substrates. Acetylation of CypA does not therefore appear to distort its conformation or substantially rearrange the active-site. However, acetylation does have a dramatic affect on surface electrostatics. Calculation of the surface electrostatic potential using the Adaptive Poisson-Boltzmann Solver (APBS) shows that K125 provides the strongest patch of positive charge in the active site (Figure 2e&f) and that this charge is largely neutralized by the acetyl group. Such a dramatic shift in electrostatics correlates with our observation that acetylation switches CypA from requiring a basic to an acidic environment.

Acetylation inhibits cyclosporine binding

The formation of the CypA:Cs complex is a prerequisite for realizing the immunosuppressive effects of Cs. To investigate the effect of CypA acetylation on Cs binding we compared the steady-state affinity of Cs to acetylated and non-acetylated CypA by following the fluorescence enhancement of the single CypA tryptophan residue that occurs upon complex formation. Using this method we measured a CypA:Cs dissociation constant of 1 ± 1.2 nM, which is within the previously reported range (1 nM to 205 nM)21. Measurements of acetylated CypA binding to Cs reveal that acetylation reduces the affinity of CypA for Cs 20 fold to 19 ± 2 nM (Supplementary Figure 3a&b). We confirmed the affect of acetylation on Cs binding by enzyme inhibition. Cs gave an inhibition constant of 1.3 ± 0.2 nM for CypA and an inhibition of 27 ± 5.6 nM for acetylated Cyp (Supplementary Figure 4).

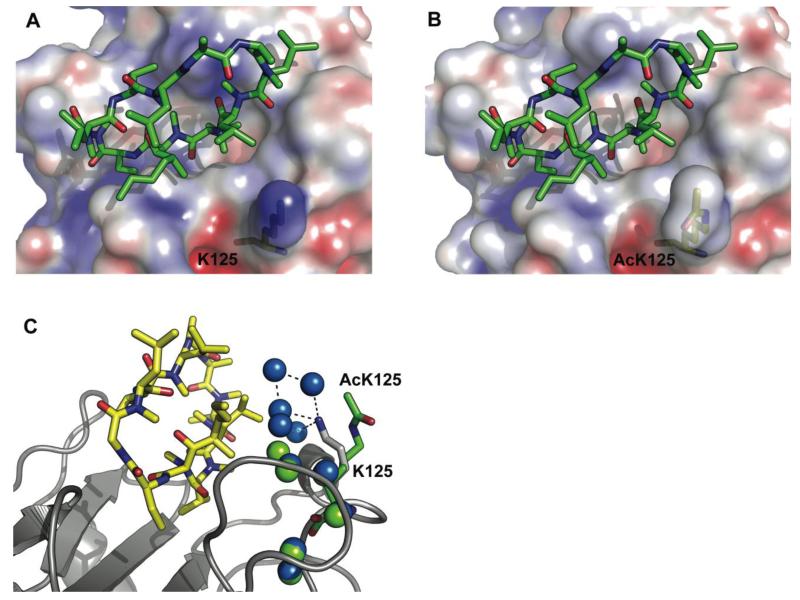

To determine the molecular basis for the affinity change we solved the structure of Cs in complex with acetylated CypA. The complex crystallized in a hexagonal spacegroup with 5 molecules in the asymmetric unit. The acetylated complex superposed closely with the previously solved non-acetylated structure, however comparison of the electrostatics show that the changes in charge mediated by the acetyl group directly alter the environment of the bound substrate (Figure 3a&b). A major effect of this change is to disrupt the water network between CypA and Cs. In the non-acetylated complex, K125 mediates a shell of waters at the interface between CypA and Cs (Figure 3C). Acetylation of K125 releases the network of 5 water molecules ordered by the ε-amino group of this lysine (Figure 3c). This solvent remodelling may explain the effect of acetylation on the thermodynamics of Cs binding and illustrates how acetylation may control protein:small molecule interactions without eliciting rearrangement of structure or inducing allosteric changes.

Figure 3. Structural comparison of the nonacetylated and acetylated CypA:Cs complexes.

A view of the binding site of the nonacetylated complex (a) and acetylated complex (b) from the superposed structures is shown with the Cs in green and CypA as a molecular surface upon which the electrostatic surface potential has been mapped using APBS. As can be seen, acetylation alters the active site charge. (c) The role of waters at the CypA:Cs interface is shown. Cs is in yellow, CypA and K125 in gray and the acetyllysine side-chain in green. Waters belonging to the non-acetylated complex are shown in blue whilst waters belonging to the acetylated complex are in green. Acetylation results in loss of much of the water network at the interface. The previously solved structure 2CPL36 was used in the comparison.

Acetylation modulates calcineurin inhibition

The Cs:CypA complex is a potent inhibitor of calcineurin (a phosphatase) and the immunosuppressive effects of Cs are a direct result of this inhibition. To examine the effect of acetylation on the ability of the CypA:Cs complex to inhibit calcineurin we assayed the calcineurin-mediated release of phosphate from the RII-phosphopeptide22 as a function of [CypA: Cs]. Under conditions where Cs is in excess, and equal amounts of CypA:Cs are formed with the acetylated and non-acetylated cyclophilin we find a Ki for the non-acetylated complex of 497 nM, which is similar to the inhibition constants previously measured for this interaction22. Acetylation reduced the calcineurin inhibition constant (Ki) by 2-fold to 972 nM (Supplementary Figure 5). The potency of Cs immunosuppression is determined by the affinity of Cs for CypA and the efficiency with which the CypA: Cs complex inhibits calcineurin. Since we have shown that acetylated CypA binds Cs 20-fold more weakly than the non-acetylated CypA, and since the acetylated CypA:Cs complex mediates a 2-fold decrease in calcineurin inhibition the total effect of acetylation on CypA-mediated immunosupression may be multiplicatively larger than either of these individual effects. However, the potent immunosuppression mediated by Cs in patients suggests that the acetylation levels in T cells in vivo or acetylation itself is not sufficient to completely abolish calcineurin inhibition in these cells.

Acetylation inhibits CypA catalysis

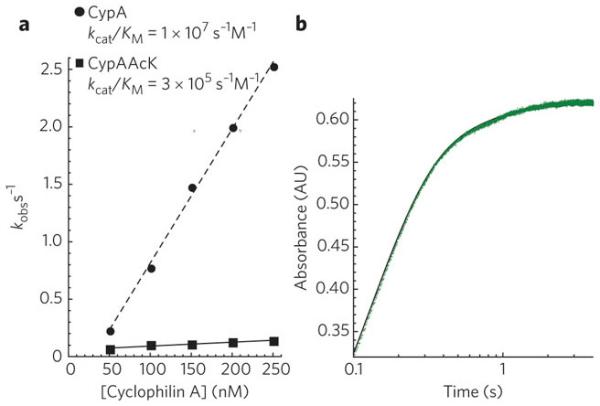

To determine how acetylation has altered the enzymatic activity of CypA, we used a modified form of the linked chymotrypsin assay23 to measure the kcat/KM of cis to trans isomerisation. In this assay, cleavage of a nitroanilide peptide substrate by chymotrypsin (Suc-AAPF-pNA) was detected by measuring the absorbance of liberated 4-nitroaniline. The peptide is also a substrate for CypA and contains a proline residue that at equilibrium is approximately 90% trans and 10% cis. The trans form of the peptide is readily cleaved by chymotrypsin whereas the cis form can only be cleaved following its isomerisation by CypA. Previous studies have used steady-state methods to determine the kcat/KM of CypA isomerisation, however this results in loss of data during mixing of the reaction components. Moreover, this approach cannot differentiate the two kinetic events and therefore does not take into account any contribution of the fast cleavage of trans peptide to the apparent rate of isomerisation. We have used a stopped-flow spectrophotometer, which allows pre-steady state measurement (due to rapid mixing <1ms) and the resolution of separate kinetic events. Using our stopped-flow method we observe two discrete phases in 4-nitroaniline production, corresponding to a fast cleavage step and a slower isomerisation step (Figure 4a). The molecular processes underpinning the fast and slow steps are confirmed by their relative amplitudes, which correspond closely to the expected cis/trans distribution of the substrate such that the slower isomerisation step represents ~10% of the total amplitude change. By fitting each experiment to a double exponential we obtained an accurate measurement of the apparent rate of cis to trans isomerisation at different CypA concentrations. The kcat/KM was then calculated by fitting the increase in apparent rate (kobs) with increasing CypA concentrations (E) to kobs = (kcat/KM)[E]. Comparison of CypA to acetylated CypA reveals that acetylation dramatically decreases kcat/KM by 35-fold from 1×107 M−1 s−1 to 3×105 M−1 s−1 (Figure 4b).

Figure 4. Acetylation decreases CypA-catalysed cis to trans isomerisation.

Cleavage of a nitroanilide peptide substrate for both chymotrypsin and CypA results in two kinetic events corresponding to cleavage of trans substrate and cis-trans isomerisation (a). These events are fit to a double exponential to determine the apparent relaxation rate kobs (b). Plotting either CypA or acetylated CypA concentration against kobs and fitting to kobs = (kcat/KM)[E] gives kcat/KM.

Acetylation alters HIV-1 capsid interaction

CypA is an important host co-factor in HIV-1 replication. Inhibition of the CypA:HIV-1 capsid interaction by Cs or mutation of the CypA-binding-loop reduces infectivity10,11,24,25. NMR measurements demonstrate that the G89-P90 peptide bond in HIV-1 capsid is isomerized by CypA, and it has been proposed that CypA may catalyse the disassembly of viral capsid26. To investigate how acetylation affects the thermodynamics of CypA:capsid interaction we performed isothermal titration calorimetry. We found that the acetylated and non-acetylated forms of CypA bind HIV-1 capsid with similar affinities. However, acetylation altered the thermodynamics of interaction (Table 1). The interaction of non-acetylated CypA and HIV1-CAN was mainly enthalpy driven (−7.4 kcal/mol), whereas the entropic contribution was only marginal (0.6 kcal/mol). Acetylation substantially reduced enthalpic favourability (by 2.8 kcal/mol) but this was compensated for by an increase in entropy (by 1.8 kcal/mol). The replacement of glutamine for lysine has often been used to mimic acetyllysine and the effects of acetylation. We used ITC characterization of capsid binding to determine how effective glutamine is as a substitute. The affinity of the glutamine mutant K125Q was decreased in comparison to the acetylated CypA (Table 1). Furthermore the thermodynamics of K125Q binding to capsid was similar to unacetylated CypA. This indicated that glutamine is not a good mimic of acetyllysine in this case.

Table 1. Effect of acetylation on CypA interaction with HIV-1 capsid.

Isothermal titration calorimetry was used to determine the thermodynamics of interaction of HIV-1 N-terminal capsid domain with non-acetylated CypA, acetylated CypA and acetylation-mimic mutant K125Q. Acetylation causes no significant change to the affinity (KD) but alters the entropy (T∆S) and enthalpy (∆H) components indicating that the mechanism of binding has been altered. The K125Q data illustrates that glutamine is not a good mimic of acetyllysine.

| Protein | KD / μM | ΔH / kcal·mol−1 | TΔS/ kcal·mol−1 | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CypAWT | 7.5 ± 0.8 | −7.4 ± 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.01 |

| CypAAcK | 6.1 ± 0.9 | −4.6 ± 0.1 | 2.4 | 0.9 ± 0.02 |

| CypA[K125Q] | 10 ± 0.7 | −6.1 ± 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 + 0.01 |

Since enthalpy-entropy-compensation can indicate a change in binding mechanism we investigated the effects of CypA acetylation on capsid recognition by determining the structure of acetylated CypA:HIV-1 M group CAN at a resolution of 1.95 Å. We compared this structure to a previously solved non-acetylated complex27 to reveal the molecular differences in the complexes that result from acetylation of CypA.

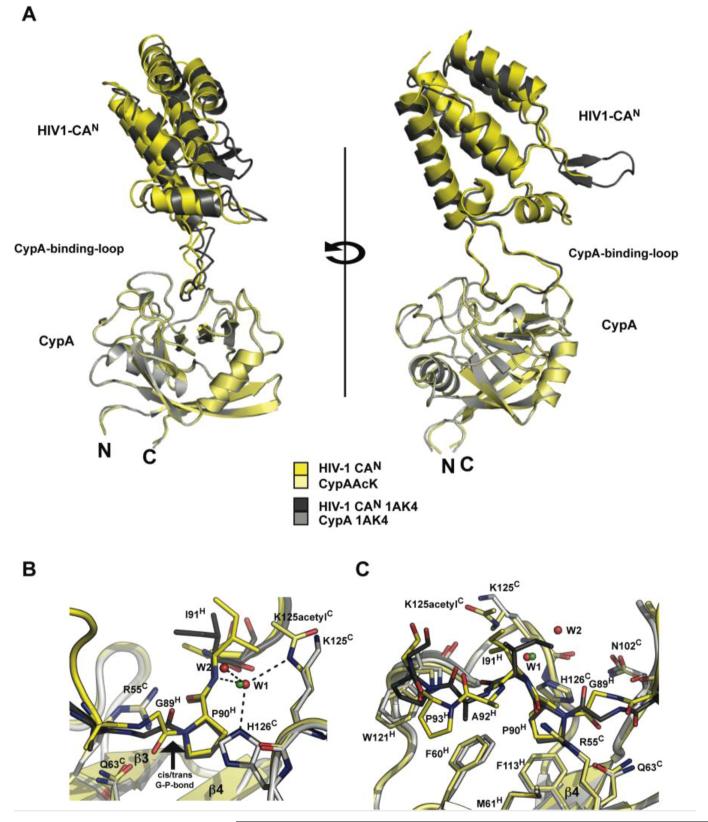

The acetylated and non-acetylated CypA:HIV1-CAN complexes superposed closely but with minor changes in the orientation of the capsid scaffold with respect to the CypA-binding-loop (Figure 5a). The major difference between the two structures is that whilst both copies of the capsid in the non-acetylated structure are bound with their G89-P90 peptide bond in a trans conformation, in both copies in the acetylated structure the GP peptide bond is in a cis conformation (Figure 5b&c). This change in HIV-1 capsid binding from trans to cis is a direct result of acetylation of K125. In the non-acetylated complex the trans G89 peptide oxygen is orientated towards the positive electrostatic patch provided by K125 and H126, in the acetylated complex the oxygen is orientated away. This altered substrate binding correlates with our solution data on the affect of acetylation on CypA catalysis. Enzymatic characterization showed that acetylation inhibits isomerisation and reduced kcat/KM by 35-fold (Figure 4). Altered HIV-1 binding, namely the switch from trans to cis proline in the HIV-1 complex, is consistent with this reduced kcat/KM, which is a measure of cis to trans isomerisation. In addition to switching cis/trans preference through charge neutralisation, the acetyl-lysine also stabilized the cis conformation of HIV-1 capsid by making new hydrogen bond and hydrophobic interactions. The methyl group of the acetyl moiety forms a new hydrophobic interaction with an alternative side-chain conformer of I91. This interaction results in main-chain changes that are propagated to C-terminal residues A92 and P93, altering their interactions in turn. In the non-acetylated complex P93 forms a hydrophobic stacking interaction with CypA residue W121. The rearrangement in the position of P93 caused by acetylation leads to an alternative stacking interaction with the aromatic ring of conserved CypA residue F60. Finally, the acetyl-lysine mediates a new water network involving the side-chain of highly conserved H126, the main-chain amide of I91 and two water molecules (Figure 5b). Acetylated CypA therefore stabilises the HIV-1 capsid in its cis form by engaging residues C-terminal to the isomerized proline P90 in a different conformation. This correlates with the proposed catalytic pathway for nitroanilide peptide substrates, in which the position of residues C-terminal to the isomerized proline alters according to whether the peptide binds in cis or trans28.

Figure 5. Structural comparison of non-acetylated and acetylated CypA:HIV-1 complexes.

(a) Ribbon representation of the superposed complexes in two views. (b&c) Interaction between CypA active-site residues and the capsid. The isomerized G89-P90 cis-trans peptidyl-prolyl bond can be clearly seen. Acetylation alters both selectivity for this bond and the conformation of capsid bound by CypA. The acetylated complex is in yellow, the non-acetylated complex is in gray. Red spheres represent waters from the acetylated structure whilst green spheres are from the non-acetylated structure. Water w1 is conserved in both complexes.

Discussion

We have shown that CypA is substantially post-translationally acetylated in human cells and that this acetylation modulates key CypA functions including Cs binding, calcineurin inhibition and HIV-1 capsid interaction. We have solved the first high-resolution crystal structures of an acetylated protein, both in its free form and in complex with small molecules and protein ligands. These structures and accompanying biochemical and biophysical studies reveal that CypA acetylation antagonizes sequential binding and catalytic activities in the pathway that regulates the immunosuppressive effects of Cs, decreases the catalytic efficiency of CypA cis to trans isomerisation 35-fold and switches the binding of CypA from trans to cis HIV-1 capsid.

Acetylation represents a previously unexamined aspect of CypA biology. Identifying the acetyltransferases and deacetylases that modulate CypA acetylation levels will be important in exploring how CypA acetylation modulates function in response to stimuli such as immune stimulation. CypA is widely expressed yet different tissues display different CypA phenotypes. For instance, Cs and its derivatives are potent inhibitors and widely-used immunosuppressives but they have limited off-target effects. A study on calcineurin inhibition by Cs in different tissues found wide variation in potency that was not always explicable by variation in CypA levels29. Furthermore, HIV-1 interaction with CypA in different cell lines and different species gives rise to diverse and unpredictable phenotypes30,31. Differences in acetylation levels in different tissues may underpin some of this variation.

In binding to HIV-1 capsid, as in binding to Cs, acetylation mediates its effects through changes in both the charge and water network in the active site. However, in the case of HIV-1 binding (and in contrast to Cs) acetylation also mediates changes in the orientation of key interaction residues, generating new interactions and abolishing interactions present in the unacetylated complex. Disassembly of the viral capsid is an essential step in HIV-1 infection and may be catalysed by CypA isomerisation of the G89-P90 peptide bond26. By reducing CypA activity, as indicated both by the enzyme kinetics and the altered substrate binding in the complexed structure, acetylation may interfere with this process and reduce viral infectivity. In addition to HIV-1, Hepatitis C (HCV) has also been shown to require CypA for efficient replication8. As CypA inhibitors represent potential anti-HCV drugs32, it will be interesting to see whether acetylation impacts on the role of CypA in HCV replication. Finally, CypA is part of a larger CypA family, including proteins such as CypB that are almost identical in sequence yet have discrete specificities33. Post-translational modification of CypA but not CypB may have a role in differentiating their function. Acetylation may inhibit binding to some substrates but allow CypA to isomerize new ones.

A persistent challenge in studying the role of acetylation has been in the preparation of homogeneously and site-specifically acetylated proteins. Histone proteins have been acetylated using semi-synthetic methods34, but these methods are generally limited to the termini of proteins and yield small amounts of material, making biophysical studies challenging. Enzymatic modification with HATs is generally non-quantitative35 and leads to heterogeneity in the site and extent of acetylation. These methods of acetylation lead to non-homogenous samples that are unsuitable for quantitative biophysical studies or structural biology. Our experiments demonstrate that homogeneously and site specifically acetylated proteins that are suitable for structural studies and quantitative measurements can be made in excellent yield using an acetyllysyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNACUA pair18. Using this approach it will be possible to further explore the role of acetylation in controlling organism function.

While acetylation is often considered to simply neutralize electrostatic interactions our data reveal that the modification can regulate protein function by at least four general mechanisms – solvent remodelling, electrostatic quenching, hydrophobic interactions and surface complementarity. Since many acetylation sites have now been identified, it will be interesting to investigate how the molecular mechanisms we have uncovered are manipulated and augmented by cells to control organism function and possibly to combat viral infection.

Materials and Methods

Recombinant proteins

All CypA proteins were expressed in E. coli C41 and purified through their N-terminal His6-tag, followed size exclusion chromatography. Acetyl-CypA (CypaAcK) was expressed from a pCDFDuet-vector containing coding regions for the Methanosarcna barkeri MS tRNACUA (MbtRNACUA) and the CypAK125amber, respectively. The incorporation of pyrrolysine in M. barkeri MS is directed by a pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase (MbPylRS) and its cognate amber suppressor, MbtRNACUA, in response to an amber codon. For further details see Supplementary Methods.

ITC measurements

The interaction of CypA/CypAAcK/CypA [K125Q] and HIV1-CAN -capsids was performed by ITC based on Wiseman et al.37 using a MicroCal™ VP-ITC 200 microcalorimeter. For details see Supplementary Methods.

Linked chymotrypsin assay

A modified form of the linked chymotrypsin assay23 was used to allow pre-steady state measurement of CypA catalysed cis to trans isomerisation. Experiments were carried out at 5°C using a Hi-Tech KinetAsyst Stopped-Flow System in a 1:1 mixing mode and with the photomultiplier in-line with the long-pathlength of the cell. Briefly, an equal volume of 100 μM N-Succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe p-nitroanilide peptide (Sigma) in one syringe was rapidly mixed with a solution in a second syringe containing 5mg/ml bovine α-chymotrypsin (Sigma) and increasing concentrations of CypA from 0-500 nM. Biphasic liberation of nitroanilide was observed and fit to a double exponential, where the first fast step with greater amplitude corresponds to cleavage of trans peptide by chymotrypsin and the second slower step with smaller amplitude corresponds to cis to trans isomerisation by CypA. Determination of the apparent relaxation rate for isomerisation was performed on an average of at least 3 independent measurements. The results of experiments at different CypA concentrations were then used to determine kcat/KM as described in the main text. For inhibition experiments see Supplementary Methods.

Fluorescence equilibrium titration measurements

All experiments were performed by using a Perkin Elmer LS55 Fluorimeters at 20°C in buffer A. The interaction of Cs and CypA was followed by measuring the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of W121 (λex: 280 nm, λem: 338 nm). Cs was added stepwise (final concentrations: 1–240 nM) to 10-50 nM CypA/CypAAcK, rapidly mixed and the fluorescence-intensity measured. The final intensity at each titration point was calculated from the average of 20 measurements at equilibrium. The relative fluorescence-intensity was plotted as a function of Cs concentration and the obtained curve was analysed by fitting a quadratic function to the data. For data analysis, Grafit 3.0-Grafit 5.0 was used. Final KD values were calculated from the mean of at least two independent titration experiments.

Crystallisation and structure determination

For details of crystallisation conditions see Supplementary Methods. All crystals were obtained using sitting drop for initial screens and the hanging drop/vapour diffusion method for optimisation. Crystals were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen using the cryoprotectants described above. Data-set collection was performed at the ESRF in Grenoble, France at beamline ID29. For data analysis see Supplementary Methods.

Cell culture, Immunoprecipitation and Western-blotting

Suspension HeLa S3 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum (FCS) and 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in 2 liter cell culture flasks (density: 0.5 × 106 cell/ml; viability: >90%). Lysis was performed in lysis buffer (0.3% Triton × 100, 20 mM nicotinamide, 1 μM trichostatin A, 50 μM sirtinol in 1×PBS) for 1h on ice. Pre-clearing was done by adding 100 μl of protein A-sepharose-slurry (GE Healthcare) to 1 ml of cell lysate (30 min, 4°C). IP was done by addition of 1.5 μg/ml of the polyclonal anti-CypA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, rabbit)-antibody (1h, 4C). After addition of 100 μl of prepared protein A-sepharose the antibody-protein-complexes were bound to the beads for 4h. The beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and 50 μl of 2-fold SDS-running buffer was added. Western blotting has been done using a standard protocol. 1:2000 monoclonal anti-acetyllysine antibody and 1:500 polyclonal anti-CypA (Biomol or Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used. The detection system was based on the non-radioactive ECL-reaction (GE Healthcare) using Horseraddish-coupled secondary antibody.

Immunodepletion experiments

HeLa S3 cells and Jurkat T-cells were grown in DMEM or RPMI medium, respectively. 500 ml of cells with a titer of 1×106 cells/ml were harvested, washed with PBS and resuspended in lysis buffer (0.3% Triton X100, 1mM TSA, 50 mM Sirtinol, 20 mM nicotinamide, protease inhibitors). Lysate was pre-cleared as described, before adding 1.5 μg/ml anti-CypA antibody (Biomol) for immunoprecipitation. After incubating for 1h at 4°C, 100 μl protein A sepharose was added and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing the beads 3 times with lysis buffer, CypA was eluted from the sepharose beads and split into 2 samples. One sample was incubated with 15 μg/ml anti-acetyllysine antibody and the other with the same volume of PBS (1h, 4°C). 50 μl of protein A sepharose was added and incubated over night at 4°C. Depleted supernatant was then loaded onto SDS-PAGE for western analysis using anti-CypA antibody. Standard deviations were calculated from at least three independent measurements. See Supplementary Materials for standardization details.

Calcineurin-Phosphatase-Assay

Calcineurin activity was determined using a colorimetric assay (Biomol), in which released phosphate from a RII-phosphopeptide (sequence: Asp-Leu-Asp-Val-Pro-Ile-Pro-Gly-Arg-Phe-Asp-Arg-Arg-Val-P-Ser-Val-Ala-Ala-Glu) is detected upon complex formation with Malachite green (A 620 nm)38. For full details see Supplementary Materials.

Compounds used in this study

Sirtinol (purity ≥95%, HPLC), trichostatin A (TSA) (5 mM in DMSO), nicotinamide (purity ≥99.5%, HPLC) and cyclosporine (purity ≥98.5%, TLC) were purchased from Sigma. Acetyl lysine was from Bachem (purity ≥99%, TLC).

Statistical data analysis

Where multiple experiments were performed the mean value has been quoted followed by the standard deviation as calculated using the standard equation s = √(Σ(X-M)2/(n-1)), where Σ = sum of, X = individual score, M = mean and N = sample size.

Protein Data Bank

Coordinates for orthogonal free acetyl-CypA, trigonal free acetyl-CypA, cyclosporine complex and HIV-1 N-terminal capsid complex have been deposited with accession codes 2×25, 2×2a, 2×2c and 2×2d respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by The Medical Research Council.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Ou WB, Luo W, Park YD, Zhou HM. Chaperone-like activity of peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase during creatine kinase refolding. Protein Sci. 2001;10:2346–53. doi: 10.1110/ps.23301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Min L, Fulton DB, Andreotti AH. A case study of proline isomerization in cell signaling. Front Biosci. 2005;10:385–97. doi: 10.2741/1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uittenbogaard A, Ying Y, Smart EJ. Characterization of a cytosolic heat-shock protein-caveolin chaperone complex. Involvement in cholesterol trafficking. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6525–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helekar SA, Char D, Neff S, Patrick J. Prolyl isomerase requirement for the expression of functional homo-oligomeric ligand-gated ion channels. Neuron. 1994;12:179–89. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nahreini P, et al. Effects of altered cyclophilin A expression on growth and differentiation of human and mouse neuronal cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2001;21:65–79. doi: 10.1023/A:1007173329237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decker ED, Zhang Y, Cocklin RR, Witzmann FA, Wang M. Proteomic analysis of differential protein expression induced by ultraviolet light radiation in HeLa cells. Proteomics. 2003;3:2019–27. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roehrl MH, et al. Selective inhibition of calcineurin-NFAT signaling by blocking protein-protein interaction with small organic molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7554–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401835101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatterji U, et al. The isomerase active site of cyclophilin A is critical for hepatitis C virus replication. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16998–7005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.007625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franke EK, Yuan HE, Luban J. Specific incorporation of cyclophilin A into HIV-1 virions. Nature. 1994;372:359–62. doi: 10.1038/372359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thali M, et al. Functional association of cyclophilin A with HIV-1 virions. Nature. 1994;372:363–5. doi: 10.1038/372363a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sokolskaja E, Sayah DM, Luban J. Target cell cyclophilin A modulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity. J Virol. 2004;78:12800–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12800-12808.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price AJ, et al. Active site remodeling switches HIV specificity of antiretroviral TRIMCyp. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1036–42. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kouzarides T. Acetylation: a regulatory modification to rival phosphorylation? Embo J. 2000;19:1176–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marmorstein R, Roth SY. Histone acetyltransferases: function, structure, and catalysis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:155–61. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denu JM. The Sir 2 family of protein deacetylases. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:431–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mujtaba S, Zeng L, Zhou MM. Structure and acetyl-lysine recognition of the bromodomain. Oncogene. 2007;26:5521–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim SC, et al. Substrate and functional diversity of lysine acetylation revealed by a proteomics survey. Mol Cell. 2006;23:607–18. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumann H, Peak-Chew SY, Chin JW. Genetically encoding N(epsilon)-acetyllysine in recombinant proteins. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:232–4. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumann H, et al. A method for genetically installing site-specific acetylation in recombinant histones defines the effects of H3 K56 acetylation. Mol Cell. 2009;36:153–63. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howard BR, Vajdos FF, Li S, Sundquist WI, Hill CP. Structural insights into the catalytic mechanism of cyclophilin A. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:475–81. doi: 10.1038/nsb927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fanghanel J, Fischer G. Thermodynamic characterization of the interaction of human cyclophilin 18 with cyclosporin A. Biophys Chem. 2003;100:351–66. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Etzkorn FA, Chang ZY, Stolz LA, Walsh CT. Cyclophilin residues that affect noncompetitive inhibition of the protein serine phosphatase activity of calcineurin by the cyclophilin.cyclosporin A complex. Biochemistry. 1994;33:2380–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00175a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kofron JL, Kuzmic P, Kishore V, Colon-Bonilla E, Rich DH. Determination of kinetic constants for peptidyl prolyl cis-trans isomerases by an improved spectrophotometric assay. Biochemistry. 1991;30:6127–34. doi: 10.1021/bi00239a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braaten D, Franke EK, Luban J. Cyclophilin A is required for the replication of group M human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and simian immunodeficiency virus SIV(CPZ)GAB but not group O HIV-1 or other primate immunodeficiency viruses. J Virol. 1996;70:4220–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4220-4227.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Towers GJ, et al. Cyclophilin A modulates the sensitivity of HIV-1 to host restriction factors. Nat Med. 2003;9:1138–43. doi: 10.1038/nm910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bosco DA, Eisenmesser EZ, Pochapsky S, Sundquist WI, Kern D. Catalysis of cis/trans isomerization in native HIV-1 capsid by human cyclophilin A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5247–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082100499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gamble TR, et al. Crystal structure of human cyclophilin A bound to the amino-terminal domain of HIV-1 capsid. Cell. 1996;87:1285–94. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81823-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eisenmesser EZ, Bosco DA, Akke M, Kern D. Enzyme dynamics during catalysis. Science. 2002;295:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.1066176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kung L, et al. Tissue distribution of calcineurin and its sensitivity to inhibition by cyclosporine. Am J Transplant. 2001;1:325–33. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2001.10407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hatziioannou T, Perez-Caballero D, Cowan S, Bieniasz PD. Cyclophilin interactions with incoming human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsids with opposing effects on infectivity in human cells. J Virol. 2005;79:176–83. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.176-183.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ylinen LMJ, et al. Cyclophilin A Levels Dictate Infection Efficiency of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Capsid Escape Mutants A92E and G94D. Journal of Virology. 2009;83:2044–2047. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01876-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watashi K, Shimotohno K. Chemical genetics approach to hepatitis C virus replication: cyclophilin as a target for anti-hepatitis C virus strategy. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:245–52. doi: 10.1002/rmv.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watashi K, et al. Cyclophilin B is a functional regulator of hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase. Molecular Cell. 2005;19:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shogren-Knaak M, et al. Histone H4-K16 acetylation controls chromatin structure and protein interactions. Science. 2006;311:844–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1124000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson PJ, et al. 30 nm chromatin fibre decompaction requires both H4-K16 acetylation and linker histone eviction. J Mol Biol. 2008;381:816–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ke H. Similarities and differences between human cyclophilin A and other beta-barrel structures. Structural refinement at 1.63 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1992;228:539–50. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90841-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiseman T, Williston S, Brandts JF, Lin LN. Rapid measurement of binding constants and heats of binding using a new titration calorimeter. Anal Biochem. 1989;179:131–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Enz A, Shapiro G, Chappuis A, Dattler A. Nonradioactive assay for protein phosphatase 2B (calcineurin) activity using a partial sequence of the subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase as substrate. Anal Biochem. 1994;216:147–53. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.