Abstract

Objective

To explore the impact of expanded eligibility criteria for antiretroviral therapy (ART) on median CD4+ cell count at ART initiation and early mortality on ART.

Methods

Analyses included all adults (≥16 years) initiated on first-line ART between August 2004 and July 2012. CD4+ cell count threshold 350 cells/μL for all adults was implemented in August 2011. Early mortality was defined as any death within 91 days of ART initiation. Trends in baseline CD4+ cell count and early mortality were examined by year (August-July) of ART initiation. Competing-risks analysis was used to examine early mortality.

Results

A total of 19 080 adults (67.6% female) initiated ART. Median CD4+ cell count at ART initiation was 110-120 cells/μL over the first six years, increasing marginally to 145 cells/μL in 2010/11 and more significantly to 199 cells/μL in 2011/12. Overall, there were 875 deaths within 91 days of ART initiation; early mortality rate 19.4 per 100 person-years (95% confidence interval (CI) 18.2-20.7). After adjustment for sex, age, baseline CD4+ cell count and concurrent TB, there was a 46% decrease in early mortality for those who initiated ART in 2011/12 compared to the reference period 2008/9 (sub-hazard ratio 0.54, 95% CI 0.41-0.71).

Conclusions

Since the expansion of eligibility criteria, there is evidence of earlier access to ART and a significant reduction in early mortality rates in this primary health care programme. These findings provide strong support for national ART policies and highlight the importance of earlier ART initiation for achieving reductions in HIV-related mortality.

Keywords: HIV-1, anti-retroviral agents, CD4 lymphocyte count, mortality, access to health care

Introduction

Rapid scale-up of public health antiretroviral therapy (ART) programmes in the past decade has led to over eight million HIV-infected individuals receiving treatment in low- and middle-income countries1. One of the persistent challenges in sub-Saharan Africa has been the high rates of early mortality on ART, observed consistently in programmes from the region and reported to be substantially higher than in high-income settings2-5. There is strong evidence that mortality can be reduced with earlier initiation of ART6,7; in 2010 the World Health Organization (WHO) changed the recommended CD4+ cell count threshold for initiation of ART from 200 cells/μL to 350 cells/μL8. This recommendation has now been adopted by several countries, including South Africa, the country with the largest HIV treatment programme in the world9.

There is as yet limited evidence that adoption of these policies has led to changes in the timing of presentation for care and treatment or to early mortality on antiretroviral therapy: one study from Lesotho demonstrated that earlier initiation (CD4+ cell count >200 cells/μL compared to <200 cells/μL) was feasible and associated with lower mortality in a routine programmatic setting10. Here our main objective was to use data from a large rural HIV treatment programme, where care is decentralised to primary health care level, to assess trends in CD4+ cell count at initiation of ART and mortality in the first three months after ART initiation. In particular, we set out to test the hypothesis that early mortality would decline after the expansion of treatment eligibility criteria in 2011. The manuscript was prepared with reference to the STROBE statement11,12.

Methods

The Hlabisa HIV Treatment and Care Programme

The Hlabisa HIV Treatment and Care Programme provides comprehensive HIV services at 17 primary health care (PHC) clinics and one district hospital in the predominantly rural Hlabisa sub-district (1430 km2) in northern KwaZulu-Natal4,13. The programme is coordinated by the local Department of Health (DoH) with support from the Africa Centre for Health and Population Studies (www.africacentre.ac.za). HIV treatment and care is delivered largely by nurses and counsellors in adherence with national antiretroviral treatment guidelines. South Africa implemented policy recommendations regarding ART eligibility in a phased manner: between 2004 and April 2010, eligibility for adults was based on CD4+ cell count <200 cells/μL14; this was expanded initially in April 2010 to 350 cells/μL for pregnant women and individuals with active TB disease15; in August 2011, this was extended to 350 cells/μL for all9. ART was also recommended throughout for all individuals with WHO clinical stage 4 and, since April 2010 for all individuals with drug-resistant TB.

Data collection

Clinical information is collected at time of ART initiation for all individuals and transferred from standardised paper-based clinic records to a Microsoft® SQL database housed at the Africa Centre. Paper-based records are used at each clinic to capture subsequent visits during follow-up on ART and to document any change in vital status (death, loss to follow-up, transfer out). Information from these records is transferred to the database at the end of each month. As part of routine programme operations, a single tracking team attempts to contact individuals that have missed clinic visits and thus identifies deaths in those lost to follow-up. To further improve data on mortality for those lost to follow-up, mortality data from the district hospital information system (recording in-hospital deaths since January 2011) are imported to the programme database periodically. Furthermore, mortality data from the Africa Centre Demographic Surveillance System is also used periodically to update vital status for individuals lost to follow-up (approximately 40% of adults enrolled in the treatment programme are members of the surveillance system)13,16. With both of these systems, individual records are linked between databases following a standardised protocol utilising the South African identity number, name, surname, age and sex.

All CD4+ cell counts were performed by the National Health Laboratory Service using the Beckman Coulter EPICS XL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter Inc. Brea, California). Since January 2007, all CD4+ cell count results from the sub-district were provided by the NHLS and were transferred to the programme database on a fortnightly basis; laboratory records were merged with existing clinical records following a standardised protocol utilising the unique South African identity number, name and date of birth. For individuals not yet commenced on ART, the database holds only CD4+ cell count results but no clinical information17.

Data analysis

All adults (≥16 years) initiated on first-line ART between August 2004 and July 2012 and with a baseline CD4+ cell count were included in the main analysis, unless they had transferred into the programme already on ART (as for this group CD4+ cell count at initiation was not known). Baseline CD4+ cell count was defined as the last measured CD4+ cell count up to 180 days prior to date of ART initiation. Individuals were divided into eight groups on the basis of the date of ART initiation (12-month periods from August-July). This categorisation was chosen to allow clear delineation before and after the change in CD4+ cell count threshold to 350 cells/μL for all (August 2011). Baseline CD4+ cell counts were described with summary statistics: median, interquartile range (IQR), and proportions in pre-defined categories (<50 cells/μL, 50-200 cells/μL, 201-350 cells/μL, >350 cells/μL). Trends in baseline CD4+ cell count were examined for all adults and then for separate groups (males, pregnant females, non-pregnant females). To explore temporal changes in timing of first presentation for care since 2007, the first recorded CD4+ cell count was used for all adults (≥16 years at test date). This was defined as the earliest recorded CD4+ cell count in the database, providing the test date was prior to the ART initiation date. Again these were summarised within groups based on the test date (12-month periods from August-July starting in August 2007).

Early mortality was defined for this analysis as deaths within three months (≤91 days) of ART initiation, a period previously reported to be responsible for approximately 60% of the deaths in the first year of ART in this programme18. Loss to follow-up was defined as >90 days without a recorded clinic visit; transfer out was defined as formal transfer out of the programme (this did not include transfer between two clinics within the programme). Analysis allowed for at least three months follow-up for all individuals and a further three months before database closure (31 Jan 2013) to allow capture of deaths and loss to follow-up (LTF) that occurred during the first three months and to minimise bias. Competing-risks analysis was used to generate cumulative incidence functions for mortality19. Follow-up time was censored at the date of last clinic visit for those who transferred out or were lost to follow-up. Analyses were also performed separately for males, non-pregnant females and pregnant females. Competing-risks regression was used to explore factors associated with early mortality20. Missing data for any categorical variable were included in the model as a separate category.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to explore the pattern of early mortality according to CD4+ cell count: early mortality rates were estimated by time period, restricted to those with CD4+ cell count <50 cells/μL, ≤200 cells/μL and >200 cells/μL. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted under the assumption that either 20% or 40% of those individuals lost to follow-up in the last time period (2011/12) had died. This was to allow for the possibility that deaths in the later cohorts were underrepresented due to the differential time for deaths to be captured both through routine programme systems and through linkage to the hospital information system and the ACDIS. We have previously shown by linking programme data to demographic surveillance data that 40% of adults lost to follow-up in the first three months of ART had died21. All analyses were conducted using STATA 11.2 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was granted by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal and the Health Research Committee of the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health for the retrospective analysis of data from the Hlabisa HIV Treatment and Care Programme (refs. BE066/07 and HRKM012/07).

Results

Temporal changes in CD4+ cell count at initiation of ART

A total of 19 747 adults initiated ART during the period under analysis, of who 19 080 (96.6%) had a baseline CD4+ cell count recorded. Annual enrolment increased from 280 adults in 2004-5 to 4199 in 2011-12. Median age was 34 years (interquartile range (IQR) 28-42); 12 906 (67.6%) were female and, of those, 10.7% (1383/12 906) initiated ART whilst pregnant. Overall median baseline CD4+ cell count was 139 cells/μL (IQR 71-198) and was higher for females than males (151 cells/μL vs. 111 cells/μL, p <0.001).

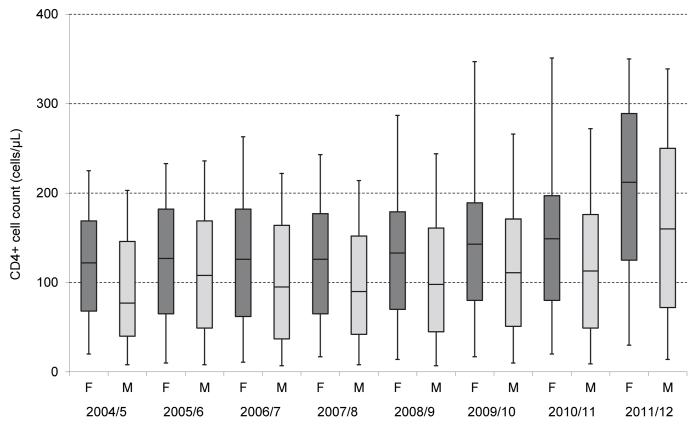

There was no significant change in baseline CD4+ cell count over the first six years (110-134 cells/μL) and only a modest increase to 145 cells/μL in 2010/11 after the initial extension of eligibility to CD4+ cell count <350 cells/μL for pregnant women and TB patients (Table 1). In the last time period (2011/12), there was a significant increase and the median CD4+ cell count of 199 cells/μL (IQR 110-280) was more than 50 cells/μL higher than for any other time period. This was accompanied by a substantial decline in the proportion with CD4+ cell count <50 cells/μL, reaching a low of 11.5% (95% confidence interval (CI) 10.6-12.5) in 2011/12. The same temporal pattern was observed when males and non-pregnant females were studied separately (Table 1 and Figure 1). The proportionate rise in median CD4+ cell count between 2010/11 and 2011/12 was similar for these two groups, although the differences between the two groups remained constant, with males having lower median CD4+ cell count and higher proportion with CD4+ cell count <50 cells/μL in all time periods. For pregnant females, a rise in median CD4+ cell count was observed over the last two time periods (2010/11 and 2011/12), consistent with the earlier implementation of the CD4+ cell count threshold of 350 cells/μL for pregnant women in April 2010. There was a low proportion of pregnant females with CD4+ cell count <50 cells/μL across all time periods.

Table 1.

Trends in baseline CD4+ cell count, overall and by sex categories (males, non-pregnant females and pregnant females)

| 2004-5 | 2005-6 | 2006-7 | 2007-8 | 2008-9 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||||||||

| Number of individuals | 280 | 907 | 1408 | 2754 | 3079 | 3159 | 3294 | 4199 | 19 080 |

| Median (IQR), cells/μL | 111 (58-163) |

122 (61-178) |

116 (52-176) |

113 (58-172) |

123 (61-175) |

134 (72-187) |

145 (76-201) |

199 (110-280) |

139 (71-198) |

| % CD4+ cell count <50 cell/μL (95% CI) |

22.1 (17.7-27.4) |

20.6 (18.1-23.4) |

24.1 (21.9-26.4) |

21.3 (19.8-22.9) |

20.2 (18.9-21.7) |

17.4 (16.1-18.8) |

16.2 (15.0-17.5) |

11.5 (10.6-12.5) |

17.6 (17.1-18.2) |

|

| |||||||||

| Males | |||||||||

| Number of individuals | 88 | 294 | 458 | 874 | 1099 | 1050 | 982 | 1329 | 6174 |

| Median (IQR), cells/μL | 77 (40-146) |

108 (49-169) |

95 (37-164) |

90 (42-152) |

98 (45-161) |

111 (51-171) |

113 (49-176) |

160 (72-250) |

111 (49-179) |

| % CD4+ cell count <50 cell/μL (95% CI) |

30.7 (22.0-41.0) |

25.5 (20.9-30.8) |

31.9 (27.8-36.3) |

29.1 (26.2-32.2) |

27.2 (24.7-29.9) |

24.9 (22.3-27.6) |

25.6 (23.0-28.4) |

18.6 (16.6-20.8) |

25.3 (24.2-26.4) |

|

| |||||||||

|

Females (non-

pregnant) |

|||||||||

| Number of individuals | 190 | 601 | 934 | 1727 | 1825 | 1845 | 1859 | 2542 | 11 523 |

| Median (IQR), cells/μL | 122 (68-169) |

127 (65-182) |

126 (62-182) |

126 (65-177) |

133 (70-179) |

143 (80-189) |

149 (80-197) |

212 (125-289) |

147 (79-200) |

| % CD4+ cell count <50 cells/μL (95% CI) |

18.4 (13.6-24.5) |

18.5 (15.6-21.8) |

20.3 (17.9-23.0) |

18.5 (16.7-20.4) |

17.5 (15.8-19.3) |

14.7 (13.2-16.4) |

14.5 (13.0-16.2) |

9.0 (7.9-10.1) |

15.1 (14.5-15.8) |

|

| |||||||||

| Females (pregnant) | |||||||||

| Number of individuals | 2 | 12 | 16 | 153 | 155 | 264 | 453 | 328 | 1383 |

| Median (IQR), cells/μL | 88 (63-113) |

138 (109-190) |

142 (59-186) |

140 (87-190) |

152 (109-191) |

174 (105-246) |

216 (145-280) |

241 (163-294) |

190 (123-265) |

| % CD4+ cell count <50 cells/μL (95% CI) |

- | 8.3 (0-24.7) |

18.8 (0-38.5) |

8.5 (4.1-13.0) |

3.2 (0.4-6.0) |

6.8 (3.8-9.9) |

2.9 (1.3-4.4) |

2.7 (1.0-4.5) |

4.5 (3.5-5.7) |

IQR, interquartile range; CI, confidence interval

Figure 1.

CD4+ cell count at initiation of antiretroviral therapy, by time period and sex (non-pregnant females and males). Upper and lower margins of the box represent the 25th and 75th centiles respectively, with the horizontal line representing the median; whiskers represent 5th and 95th centiles

Temporal changes in CD4+ cell count at first presentation for care

A total of 41 300 adults had their first CD4+ cell count measurement between August 2007 and July 2012 (Table 2). Overall median CD4+ cell count at first presentation was 273 cells/μL (IQR 136-444). There was limited change in the first four time periods but a significant rise in 2011/12 (median 317 cells/μL, IQR 170-487). This was accompanied in the last time period by a significant decline in the proportion that presented with CD4+ cell count <50 cells/μL and a rise in the proportion that presented with CD4+ cell count >350 cells/μL.

Table 2.

Temporal changes in CD4+ cell count at first presentation for care

| 2007-8 | 2008-9 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of first CD4+ cell count tests | 9662 | 8655 | 7584 | 6860 | 8539 | 41 300 |

|

CD4+ cell count, cells/μL, median

(IQR) |

253 (128-420) |

263 (129-438) |

267 (127-446) |

263 (132-431) |

317 (170-487) |

273 (136-444) |

| CD4+ cell count, cells/μL, % (95% CI) | ||||||

| <50 | 10.4 (9.8-11.0) |

10.9 (10.2-11.6) |

10.4 (9.7-11.1) |

10.7 (10.0-11.5) |

7.8 (7.3-8.4) |

10.0 (9.8-10.3) |

| 50-200 | 29.5 (28.6-30.5) |

27.8 (26.8-28.7) |

27.7 (26.7-28.7) |

27.7 (26.7-28.8) |

21.8 (21.0-22.7) |

26.9 (26.5-27.4) |

| 201-350 | 25.8 (25.0-26.7) |

24.8 (23.9-25.7) |

25.0 (24.0-26.0) |

25.8 (24.8-26.9) |

26.4 (25.4-27.3) |

25.6 (25.2-26.0) |

| >350 | 34.2 (33.2-35.1) |

36.6 (35.6-37.6) |

36.9 (35.8-37.9) |

35.7 (34.6-36.8) |

44.0 (42.9-45.0) |

37.5 (37.0-37.9) |

IQR, interquartile range; CI, confidence interval

Early mortality

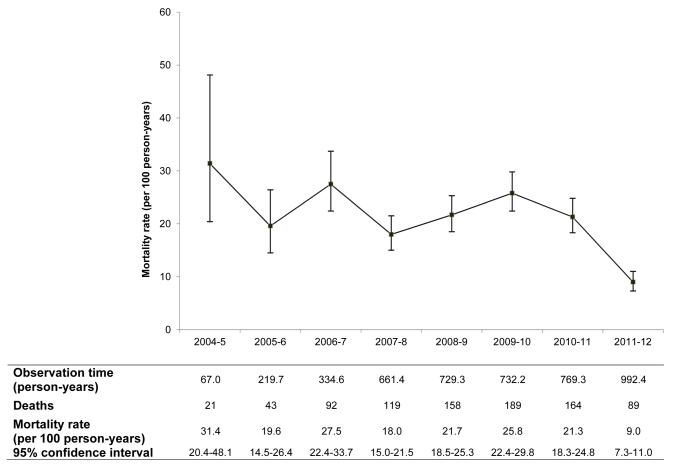

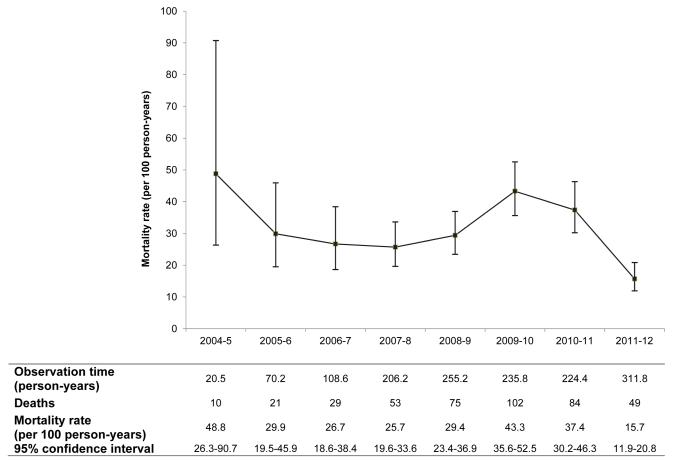

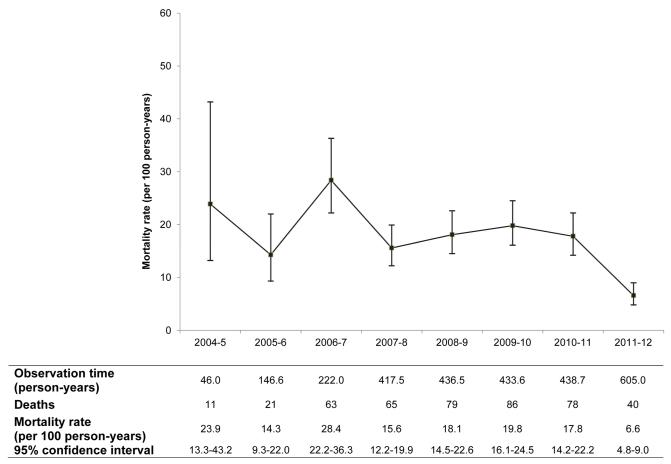

A total of 19 080 individuals were included in mortality analysis with 4506 person-years of follow-up (median 86 days). There were 875 deaths (4.6%) in the first three months of ART giving a crude early mortality rate of 19.4 per 100 person-years (95%CI 18.2-20.7). 641 individuals (3.4%) were lost to follow-up and 170 (0.9%) transferred out of the programme within three months. The deaths in the first three months represented 59.6% (875/1469) of all deaths observed in the first year of ART. There was no substantial change in early mortality until the last period where there was a large decline in mortality rate: from 21.3 per 100 person-years (95%CI 18.3-24.8) in 2010/11 to 9.0 per 100 person-years (95%CI 7.3-11.0) in 2011/12 (Figure 2A). This pattern was consistent for both males and non-pregnant females (Figures 2B and 2C); there were too few early deaths in the pregnant female group (n = 9) for temporal trends to be explored.

Figure 2A.

Mortality in the first three months of antiretroviral therapy, all adults (N = 19 080)

Figure 2B.

Mortality in the first three months of antiretroviral therapy, males (N = 6174)

Figure 2C.

Mortality in the first three months of antiretroviral therapy, non-pregnant females (N = 11 523)

In competing-risks regression, after adjustment for sex, age, baseline CD4+ cell count and concurrent TB, the time period of ART initiation was strongly associated with mortality in the first three months of ART: subhazard ratio (SHR) 0.54 (95% CI 0.41-0.71) for 2011/12 compared to the reference time period of 2008/9 (Table 3). CD4+ cell count <50 cells/μL was strongly associated with early mortality (SHR 4.25, 95%CI 3.23-5.60). Compared to non-pregnant females, males had higher early mortality (SHR 1.48, 95%CI 1.28-1.70) whereas pregnant females had substantially lower early mortality (SHR 0.23, 95%CI 0.12-0.45).

Table 3.

Competing-risks regression model (N = 19 080) for factors associated with mortality in the first three months of antiretroviral therapy

| Variable | n | Sub-hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Non-pregnant female | 11 523 | 1 | |

| Pregnant female | 1383 | 0.23 (0.12-0.45) | <0.001 |

| Male | 6174 | 1.48 (1.28-1.70) | <0.001 |

| Age | |||

| 16-24 | 2289 | 0.70 (0.53-0.93) | 0.014 |

| 25-34 | 7598 | 1 | |

| 35-44 | 5536 | 0.91 (0.77-1.06) | 0.225 |

| 45-54 | 2669 | 1.09 (0.89-1.32) | 0.412 |

| ≥55 | 988 | 1.11 (0.83-1.49) | 0.467 |

| Baseline CD4+ cell count, cells/μL | |||

| <50 | 3365 | 4.25 (3.23-5.60) | <0.001 |

| 50-200 | 11 175 | 1.46 (1.11-1.91) | 0.006 |

| 201-350 | 3969 | 1 | |

| >350 | 571 | 0.74 (0.38-1.45) | 0.384 |

| Concurrent TB diseasea | |||

| No | 13 943 | 1 | |

| Yes | 3331 | 1.08 (0.92-1.28) | 0.357 |

| Missing | 1806 | 1.19 (0.96-1.48) | 0.121 |

| Time period of ART initiation | |||

| 2004-5 | 280 | 1.37 (0.87-2.15) | 0.121 |

| 2005-6 | 907 | 0.88 (0.63-1.24) | 0.470 |

| 2006-7 | 1408 | 1.18 (0.91-1.54) | 0.204 |

| 2007-8 | 2754 | 0.84 (0.66-1.06) | 0.139 |

| 2008-9 | 3079 | 1 | |

| 2009-10 | 3159 | 1.27 (1.03-1.58) | 0.027 |

| 2010-11 | 3294 | 1.16 (0.93-1.44) | 0.191 |

| 2011-12 | 4199 | 0.54 (0.41-0.71) | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval

Concurrent TB disease was TB disease treated at the time of ART initiation

When the analysis was restricted to individuals with CD4+ cell count <50 cells/μL and ≤200 cells/μL, the substantial reduction in early mortality rate was still observed for the 2011/12 cohort (see Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/QAI/A433). The proportion of each annual cohort lost to follow-up within the first three months increased over time: 0.4% (95%CI 0-1.1) for 2004/5, 0.6% (95%CI 0.1-1.0) for 2005/6, 1.6% (95%CI 1.0-2.3) for 2006/7, 1.2% (95%CI 0.8-1.6) for 2007/8, 2.7% (95%CI 2.2-3.3) for 2008/9, 3.9% (95%CI 3.2-4.6) for 2009/10, 4.4% (95%CI 3.7-5.1) for 2010/11, and 5.4% (95%CI 4.7-6.1) for 2011/12. In sensitivity analyses, assuming deaths in 20% and 40% of those lost to follow-up from 2011/12, estimates of corrected early mortality for that period were 13.5 per 100 person-years (95%CI 11.4-16.0) and 18.0 per 100 person-years (95%CI 15.6-20.9) respectively (see Figure S1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/QAI/A433).

Discussion

In this observational study, we found evidence not only of earlier presentation for ART, but also a substantial reduction in early mortality on ART subsequent to the change in CD4+ cell count eligibility criteria which took effect in South Africa in August 2011. Median CD4+ cell count at ART initiation remained higher and mortality lower for women during all time periods, consistent with data from this region22,23. However, it is encouraging that the increase in CD4+ cell count and reduction in early mortality for those who initiated ART in the last time period (2011-12) was consistent for both non-pregnant females and males. Pregnant women only represented about 7% of all adults who initiated ART and there were very few deaths in this group so there was limited statistical power to observe any temporal trends. These data provide further encouragement at a time when substantial reductions in population-level mortality have been documented in this community and more broadly in South Africa24-27.

We have previously shown that during the first phase of rapid programme scale-up, there was no significant change in CD4+ cell count at ART initiation4. It seems that after the first policy change in 2010 to recommend ART at <350 cells/μL for TB patients and pregnant females there was minimal change in the overall median CD4+ cell count at ART initiation yet, after the expansion to <350 cells/μL for all, there has been a definite increase. This suggests that, although antenatal care and TB services remain important entry points to HIV treatment, the contribution from these groups alone was too small to see a broader impact of the expanded eligibility criteria. The increase in overall median CD4+ cell count between 2010/11 and 2011/12 was 54 cells/μL, which corresponds approximately to six months earlier in terms of disease progression according to our previous data17. The relationship between mortality risk and time period was maintained after adjustment for baseline CD4+ cell count, consistent with the fact that CD4+ cell count does not fully predict mortality28, and that other factors associated with earlier presentation, such as the absence of opportunistic infection, may have contributed to the mortality decline. It is noteworthy that in the last time period there was a decline in the absolute number and the proportion of people who initiated ART with CD4+ cell count <50 cells/μL, as this remains the factor most strongly associated with early mortality, with a fourfold increased risk of early mortality compared to CD4+ cell count 201-350 cells/μL.

These observations provide robust evidence that the reduction in early mortality has occurred since the policy change to recommend earlier initiation of ART although a direct causal association cannot be inferred from these observational data. In common with data from other large programmes in South Africa, early mortality did not change in the first few years of programme scale-up29-31. Only in the last time period (2011-12) was there a real decline in early mortality. There have been no specific interventions or programmatic changes that could easily explain the decline in early mortality. There is no formal package of care for individuals prior to eligibility for ART and retention in this group is suboptimal32. We have previously shown that TB is the most common cause of early mortality on ART and that prevalent TB at time of ART initiation is associated with almost double the risk of mortality on ART, in line with other studies in the region32-34. In this analysis, there was no independent association between TB and early mortality, although the statistical power to observe an association might have been affected by the lower risk of TB disease at higher CD4+ cell counts35. The implementation of isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) was scaled up from early 2010 yet provision remains patchy in this programme. It could be that improved integration of antiretroviral therapy with TB treatment has contributed to the reduction in mortality, in line with findings from clinical trials36,37. Alternatively, although there was no specific programmatic change, it could be related to clinic systems becoming more efficient over time, increased use of nurse-initiated ART, or by the shorter time needed for pre-ART work-up for people with higher CD4+ cell counts. Finally, given the change in the first-line antiretroviral regimen in 2010 from a stavudine-based to tenofovir-based regimen, we cannot discount that this may have accounted for some of the mortality change, although against this would be the fact that the majority of fatal adverse events related to stavudine (e.g. lactic acidosis) occur after the first three months38.

Earlier presentation for treatment may be indirectly related to the policy changes but also to improved HIV testing coverage in the community, facilitated by the nationwide HIV counselling and testing (HCT) campaign, as well as local initiatives to scale up home- and community-based HCT39. This is supported by the fact that the CD4+ cell count at enrolment in the programme also shifted substantially in the period since August 2011, to the extent that almost half of the adults who enrolled into care between August 2011 and July 2012 had a CD4+ cell count >350 cells/μL. Policy changes alone have no impact unless the health system is able to provide the services and individuals are able and willing to access those services. Our data are therefore important to show not only that people are accessing treatment earlier but that, so far, the health system has been able to cope with the increasing patient load. Not all countries are following WHO recommendations with regards to ART eligibility criteria and these data should contribute to the evidence base around the impact of earlier access to ART40.

As early loss to follow-up increased over time, mortality may have been underestimated, especially in the last time period due to the shorter time for deaths to be captured. The correction of mortality for loss to follow-up is complicated in our programme as, prior to analysis, some correction occurs routinely through linkage to the hospital information system and demographic surveillance system. Under a worst-case but unrealistic scenario, where the proportion of loss to follow-up in the last time period attributable to mortality was 40%, the estimated mortality decline was much less marked but under a more realistic assumption of 20% the decline remained significant.

The strengths of this analysis relate to the simplicity and quality of the data from a well-characterised treatment programme. Only 6% of adults who initiated ART had a missing baseline CD4+ cell count (considerably lower than the 25% reported from a multi-cohort collaboration in South Africa41), thus minimising potential bias. Nevertheless, interpretation of the findings should be subject to some caution. We were unable within this analysis to explore outcomes for those people who, while eligible, did not initiate ART. We cannot therefore exclude the possibility that unmeasured variations over time in mortality for those who did not access ART could offset the mortality decline observed for those who access ART, although the consistent decline in population-level mortality would argue against this27. Data regarding in-hospital deaths from the Hospital Information System were only available from January 2011 and in-hospital deaths during earlier time periods might have been missed if they had not been reported through the routine systems of the HIV treatment and care programme. However, this would be expected to bias the findings away from the null hypothesis and therefore would strengthen our findings. Whilst the findings should be broadly generalizable to public-sector programmes in South Africa, it is possible that not only extra financial support to the programme but also the research and community engagement activities in the area might influence access to and uptake of treatment and replication of this analysis should be performed with other programmes.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that in this rural area, since the policy shift to recommend ART for all adults with CD4+ cell count <350 cells/μL, there has been a significant increase in the median baseline CD4+ cell count and a significant reduction in mortality within the first three months of ART. These findings provide support for national and international ART policies and highlight the importance of earlier ART initiation for achieving reductions in HIV-related mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the patients who contributed data to this analysis and all the people working in and supporting the Hlabisa HIV Treatment and Care Programme.

Source of Funding:

This work was supported by a core grant to the Africa Centre from the Wellcome Trust (grant number 082384/Z/07/Z, www.wellcome.ac.uk). RL is supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 090999/Z/09/Z). The Hlabisa HIV Treatment and Care Programme has received support through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the President’s Emergency Plan (PEPFAR) under the terms of Award No. 674-A-00-08-00001-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the USAID or the United States Government. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Together we will end AIDS. UNAIDS; Geneva: [Accessed 3 September 2012]. 2012. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/20120718_togetherwewillendaids_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulle A, Bock P, Osler M, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and early mortality in South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:678–687. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.045294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawn SD, Harries AD, Anglaret X, et al. Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1897–1908. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830007cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mutevedzi PC, Lessells RJ, Heller T, et al. Scale-up of a decentralized HIV treatment programme in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: does rapid expansion affect patient outcomes? Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:593–600. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.069419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, et al. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet. 2006;367:817–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegfried N, Uthman OA, Rutherford GW. Optimal time for initiation of antiretroviral therapy in asymptomatic, HIV-infected, treatment-naive adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD008272. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008272.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Severe P, Juste MA, Ambroise A, et al. Early versus standard antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected adults in Haiti. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:257–265. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: recommendations for a public health approach – 2010 revision. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.South African National AIDS Council (SANAC) [Accessed 3 September, 2012];Statement on the meeting of the South African National AIDS Council. 2011 http://www.sanac.org.za/files/uploaded/886_Plenary%20Press%20Statement%2012Aug11.pdf.

- 10.Ford N, Kranzer K, Hilderbrand K, et al. Early initiation of antiretroviral therapy and associated reduction in mortality, morbidity and defaulting in a nurse-managed, community cohort in Lesotho. Aids. 2010;24:2645–2650. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833ec5b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houlihan CF, Bland RM, Mutevedzi PC, et al. Cohort profile: Hlabisa HIV treatment and care programme. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:318–326. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health . National antiretroviral treatment guidelines. Department of Health; Pretoria, South Africa: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Health . Clinical guidelines for the management of HIV & AIDS in adults and adolescents. Department of Health; Pretoria, South Africa: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanser F, Hosegood V, Barnighausen T, et al. Cohort Profile: Africa Centre Demographic Information System (ACDIS) and population-based HIV survey. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:956–962. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lessells RJ, Mutevedzi PC, Cooke GS, et al. Retention in HIV care for individuals not yet eligible for antiretroviral therapy: rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:e79–86. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182075ae2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mutevedzi PC, Lessells RJ, Rodger AJ, et al. Association of age with mortality and virological and immunological response to antiretroviral therapy in rural South African adults. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakoyannis G, Touloumi G, on behalf of CASCADE collaboration [Accessed 3 September, 2012];A practical guide on modelling competing risk data. 2008 http://www.ctu.mrc.ac.uk/cascade/content_pages/documents_and_files/Comp_Risks_guide.pdf.

- 20.Gutierrez R. [Accessed 3 September, 2012];Competing-risks regression. 2010 http://www.stata.com/meeting/boston10/boston10_gutierrez.pdf.

- 21.Mutevedzi PC, Lessells RJ, Newell ML. What happens to patients lost during antiretroviral therapy in rural South Africa?; 15th International Workshop on HIV Operational Databases; Prague, Czech Republic. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braitstein P, Boulle A, Nash D, et al. Gender and the use of antiretroviral treatment in resource-constrained settings: findings from a multicenter collaboration. J Womens Health. 2008;17:47–55. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cornell M, Schomaker M, Garone DB, et al. Gender Differences in Survival among Adult Patients Starting Antiretroviral Therapy in South Africa: A Multicentre Cohort Study. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herbst AJ, Cooke GS, Barnighausen T, et al. Adult mortality and antiretroviral treatment roll-out in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:754–762. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.058982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herbst AJ, Mafojane T, Newell ML. Verbal autopsy-based cause-specific mortality trends in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 2000-2009. Popul Health Metr. 2011;9:47. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-9-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradshaw D, Dorrington RE, Laubscher R. Rapid mortality surveillance report 2011. South African Medical Research Council; Cape Town: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bor J, Herbst AJ, Newell ML, et al. Increases in adult life expectancy in rural South Africa: valuing the scale-up of HIV treatment. Science. 2013;339:961–965. doi: 10.1126/science.1230413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.May M, Boulle A, Phiri S, et al. Prognosis of patients with HIV-1 infection starting antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: a collaborative analysis of scale-up programmes. Lancet. 2010 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60666-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boulle A, Van Cutsem G, Hilderbrand K, et al. Seven-year experience of a primary care antiretroviral treatment programme in Khayelitsha, South Africa. AIDS. 2010;24:563–572. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328333bfb7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fox MP, Shearer K, Maskew M, et al. Treatment outcomes after 7 years of public-sector HIV treatment. Aids. 2012;26:1823–1828. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328357058a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nglazi MD, Lawn SD, Kaplan R, et al. Changes in programmatic outcomes during 7 years of scale-up at a community-based antiretroviral treatment service in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:e1–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ff0bdc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Houlihan CF, Mutevedzi PC, Lessells RJ, et al. The tuberculosis challenge in a rural South African HIV programme. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lessells RJ, Mutevedzi PC, Ndirangu J, et al. Contribution of TB and drug-resistant TB to early mortality on antiretroviral therapy in rural KwaZulu-Natal: prospective cohort study; 5th South African TB Conference; Durban, South Africa. 2012; abstract 140. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawn SD, Harries AD, Meintjes G, et al. Reducing deaths from tuberculosis in antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2012;26:2121–2133. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283565dd1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawn SD, Myer L, Edwards D, et al. Short-term and long-term risk of tuberculosis associated with CD4 cell recovery during antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS. 2009;23:1717–1725. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d3b6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral drugs during tuberculosis therapy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:697–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, et al. Integration of antiretroviral therapy with tuberculosis treatment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1492–1501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murphy RA, Sunpath H, Kuritzkes DR, et al. Antiretroviral therapy-associated toxicities in the resource-poor world: the challenge of a limited formulary. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(Suppl 3):S449–456. doi: 10.1086/521112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maheswaran H, Thulare H, Stanistreet D, et al. Starting a home and mobile HIV testing service in a rural area of South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59:e43–46. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182414ed7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gupta S, Granich R, Suthar AB, et al. Global Policy Review of Antiretroviral Therapy Eligibility Criteria for Treatment and Prevention of HIV and Tuberculosis in Adults, Pregnant Women, and Serodiscordant Couples. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2013;62:e87–e97. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827e4992. 10.1097/QAI.1090b1013e31827e34992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cornell M, Technau K, Fairall L, et al. Monitoring the South African National Antiretroviral Treatment Programme, 2003-2007: the IeDEA Southern Africa collaboration. S Afr Med J. 2009;99:653–660. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.