Abstract

Background and Purpose

To define the distribution of cerebral volumetric and microstructural parenchymal tissue changes in a specific mutation within inherited human prion diseases (IPD) combining voxel-based morphometry (VBM) with voxel-based analysis (VBA) of cerebral magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) and mean diffusivity (MD).

Materials and Methods

VBM and VBA of cerebral MTR and MD were performed in 16 healthy controls and 9 patients with the 6-octapeptide repeat insertion (6-OPRI) mutation. An ANCOVA consisting of diagnostic grouping with age and total intracranial volume as covariates was performed.

Results

On VBM there was significant grey matter (GM) volume reduction in patients compared with controls in the basal ganglia, perisylvian cortex, lingual gyrus and precuneus. Significant MTR reduction and MD increases were more anatomically extensive than volume differences on VBM in the same cortical areas, but MTR and MD changes were not seen in the basal ganglia.

Conclusions

GM and WM changes were seen in brain areas associated with motor and cognitive functions known to be impaired in patients with the 6-OPRI mutation. There were some differences in the anatomical distribution of MTR-VBA and MDVBA changes compared to VBM, likely to reflect regional variations in the type and degree of the respective pathophysiological substrates. Combined analysis of complementary multi-parameter MRI data furthers our understanding of prion disease pathophysiology.

1 INTRODUCTION

Human prion diseases are rapidly progressive, uniformly fatal neurodegenerative disorders1, that can be inherited (IPD), occur sporadically, or be due to iatrogenic or dietary infection. The discovery of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD)2 has not been followed by a major epidemic; however, the existence of subclinical infections3 and the evidence for secondary transmission by blood transfusion4-5, reinforce the public health relevance of these conditions.

Most of the prion disease imaging literature has focused on the acquired and sporadic forms rather than IPD. In prevalence studies 15% of prion disease cases are IPD, a cause of early onset dementia, with over 30 different prion protein gene (PRNP) mutations identified6. The clinical phenotypes vary widely some mutations having a phenotype similar to sCJD eg E200K while others can mimic hereditary ataxias eg P102L or Alzheimer’s disease e.g. some cases of 4-OPRI7 the findings on conventional MRI are similarly variable.

In the UK, large kindreds presenting with six additional repeats in the octapeptide region (6-OPRI mutation), have been followed up for over two decades with detailed reports of clinical symptoms8 and neuropsychology features9 but without systematic analysis of imaging findings. These patients characteristically present with fronto parietal dysfunction progressing over 7-15 years (mean 11 years) culminating in an akinetic mute state. Visuospatial, frontal executive and nominal skills are significantly impaired in this patient group and apraxia is an important early feature.

Brain atrophy has rarely been quantified in IPD apart from a case-report of a presymptomatic P102L gene carrier demonstrating early parietal atrophy10 and a recent demonstration of parietal and occipital cortical thinning in patients with the 6-octapeptide repeat insertion (6-OPRI) mutation9. Quantitative MRI techniques such as magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) and mean diffusivity (MD) mapping have revealed significant regional and whole-brain differences between symptomatic prion disease patients and controls11-14.However, these studies employed ROI or histogram analyses, possibly missing or diluting regionally-specific changes.

Voxel-based analysis (VBA) of structural images (voxel based morphometry, VBM)15 or MRI measures such as MD or MTR overcome these limitations as they do not require a priori anatomical hypotheses. These tools have not been applied in IPD, except for patients with the E200K mutation16-18.

We performed VBM, MTR-VBA and MD-VBA in a cohort of IPD patients with the 6-OPRI mutation, some of whom were previously studied with alternative methods12-13. We hypothesized that this multi-parametric approach would localize brain abnormalities corresponding to known clinical symptoms and neuropsychological deficits, and further, that MTR and MD would quantify microstructural changes even in areas without significant volume loss on VBM.

2 METHODS

2.1 Subjects

Patients attended the National Prion Clinic at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, UK, and were recruited into the UK MRC PRION-1 trial19. Ethical approval was granted by the Eastern Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (MREC), Cambridge, UK.

Full neurological, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)20 and Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (‘sum of boxes’, CDR)21 were recorded. Where several individual patient MRI data-sets were available, in order to have a more homogeneous cohort, the dataset acquired when the patients’ CDR was closest to the group median (CDR = 8) was selected; this approach allowed to minimise the CDR standard deviation across the patient group.

Nine individuals with the6-OPRI mutation were studied (6-OPRI group: mean age 38.1±3.6 years, median MMSE 19, range 11-27, all codon 129MM). Sixteen healthy volunteers with no history of neurological disorder were included (Controls group: age 37.1±10.7 years, all MMSE 30), see Table 1.

Table 1. Subject demographics and clinical data.

| Controls | 6-OPRI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 16 (8♂) | 9 (4♂) | - |

| Age (years) | 37.1±10.7 | 38.1±3.6 | ns |

| MMSE | 30 (30-30) | 19 (11-27) | <.001 |

| CDR | - | 8 (2-14) | .002# |

Note. Age values are mean ± standard deviation. MMSE and CDR values are median (range). N=number;

=male; MMSE=mini-mental state examination; CDR=Clinician’s Dementia Rating. ns = not significant (p≥0.1) All, comparisons were performed with the Mann-Whitney U test, except for

CDR, for which Wilcoxon test vs CDR=0 was performed.

2.2 MRI acquisition

MRI was performed at 1.5-Tesla (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA) using the standard transmit/receive head coil. Sequences comprised:

structural T1-weighted imaging [3D-IR-SPGR sequence (TR/TE/TI6.4/14.5/650ms, flip angle 15°, 124 1.5mm partitions, FOV 24×18cm2, matrix 256×192, total acquisition time (AcqT) 9′48″)];

DWI with diffusion-weighting (‘b’) [single-shot EPI(TR 10s, 30 5mm slices, FOV 26×26cm2, matrix 96×128)] with diffusion-weighting factors (‘b values’) of 0 (b0) and 1000s/mm2 (b1k; TE 101ms, 1 average, AcqT 1′20″) and of 0 and 3000s/mm2 (b3k; TE 136ms, 3 averages, AcqT 4′) applied sequentially along three orthogonal axes; MD was calculated as MD1k,3k=ln(S0 /S1k,3k)/b1k,3k22 -where S0 and S1k,3k are respectively the local signal intensities of the b0 and mean of DWI (b1k or b3k) acquired in 3 orthogonal directions (as only 3 gradient sensitization directions were used, this variable is actually an approximation of the mean diffusivity that could be measured with 6 or more directions);

MTR imaging [interleaved 2D-gradient-echo sequence, similar to the EuroMT sequence23 (TR/TE 1500/15.4ms, flip angle 70°, 30 5mm slices, FOV 24×18cm2, matrix 256×192, AcqT 12′)]. Magnetization transfer pre-saturation was achieved with a Gaussian pulse of duration 12.8ms and peak amplitude 23.2μT giving a nominal bandwidth of 125Hz, applied 2kHz off water-resonance. Scans with/without presaturation were interleaved for each TR period ensuring exact co-registration of the pixels on saturated (Msat) and unsaturated (M0) images24. MTR was calculated from M0 and Msat images as MTR = (1–Msat/M0)x100in percentage units (p.u.).

FSET2-weighted (TR/TE 6000/106ms, 22 5mm slices, FOV 24×18cm2, matrix 256×224, 2 averages) and FLAIR imaging (TR/TE/TI 9897/161/2473ms, 22 5mm slices, FOV 24×24cm2, matrix 256×224).

2.3 Imaging Analysis: Qualitative analysis by visual inspection

The T2-weighted, FLAIR and DWI images were reviewed independently (in a non-blinded fashion) by two consultant neuroradiologists with experience in prion disease. Pathological signal changes were assessed in the caudate, putamen, and thalamus and in the cortex of the frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital lobes. Where a discrepancy was identified, the images were re-reviewed in a consensus reading and a kappa statistic calculated to assess the level of agreement.

2.4 Imaging analysis: Quantitative MR Imaging

a. VBM spatial pre-processing

Spatial processing for VBM was performed for structural data using SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) as follows:

SPM8’s ‘unified segmentation’, combining segmentation, bias correction and normalization to the MNI (Montreal Neurological Institute) space into a single generative model (SPM ‘Segment’)25. The rigid normalization transformation component was used to produce approximately aligned images for the following step.

Generation of a cohort specific template for GM and WM segments using DARTEL26 using all subjects.

Warping and resampling of individual GM and WM segments, normalizing them to the cohort-specific template. Local intensities for each voxel were modulated, i.e. multiplied by the ratio of voxel volume before and after normalization, to account for normalization associated volume changes27.

b. MTR-VBA preprocessing

Rigid transformations between individual Msat images and corresponding T1 datasets were estimated and then combined with the warps computed for the T1 data to normalize individual MTR maps to the cohort VBM T1-template.As voxel MTR values are not directly related to voxel volume, data was not modulated.

c. MD-VBA preprocessing

The MD3k dataset was rigidly aligned with the MD1k dataset (based on the corresponding b0 acquisitions). Affine transformations between MD and corresponding T1 images were estimated with reg_aladin28,29 to partially correct EPI-associated geometric distortion (based on the MD1k b0 acquisitions). These transforms were then combined with the warps computed for the T1 data to normalize (with no modulation) individual MD1k and MD3kmaps to the cohort VBM T1-template.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

An isotropic 6mm full-width-at-half-maximum Gaussian kernel was applied to each of the 6 normalized datasets (GM, WM, MTR, MD1k, MD3k).An ‘objective’ masking strategy30 defined the voxels for subsequent statistical analysis on GM and WM segments separately; the resulting masks were combined for MTR and MD data analysis. For each dataset, the analysis involved an ANCOVA consisting of diagnostic grouping (6-OPRI or controls) with individual age and total intracranial volume (TIV: estimated as sum of GM, WM and CSF segments) as covariates (using the same covariates for all analyses allowed for a more consistent model across modalities). Group differences between covariates were assessed with the 2-sample Mann-Whitney U test (PASW Statistics 18, IBM Corporation, NY).

SPM-t maps (p<0.05) after family-wise error (FWE) multiple-comparison correction (with no cluster-extent threshold), and effect-size maps showing group differences as percentages of the control-group mean were produced. We also computed the affine transformation between the DARTEL space (in which the SPM results where computed) and MNI space. Using these parameters, the SPM maps and effect-size maps where also transformed onto MNI space for visualization. Results are thus displayed in MNI space overlaid on the average of the warped and smoothed T1 volumes. All are presented using the neurological convention (right hemisphere displayed on the right).

2.6 Regions of Interest

To quantify differences in MR measures, 3 ROIs were defined on the right hemisphere of the average warped and smoothed T1-volume, in the thalamus, head of caudate and putamen (ROI volume range: 0.59-0.60ml) and verified for individual datasets to ensure the smoothing had not introduced CSF contamination. The ROI-mean from the corresponding warped/smoothed datasets for each individual was computed and between-group differences assessed by the 2-sample Mann-Whitney U test; to account for multiple comparisons over the three regions (but not the four metrics, as these tests are being compared to each other, rather than simply being searched over) p<0.01 was considered significant.

3 RESULTS

Between controls and 6-OPRI, differences in age were not significant, in contrast to MMSE and CDR (Table 1). The TIVs were 1.42±0.14 liters (mean ± SD) in controls and 1.41±0.20 liters in 6-OPRI and not significantly different.

3.1 Qualitative Analysis

On initial assessment, both raters agreed that there was no pathological signal change in 7 of the 9 patients. There were discrepancies in two patients where DWI signal hyperintensity in the frontal cortex was noted in one patient and FLAIR signal hyperintensity in the perihabenular region noted in another patient (kappa score 0.835). On consensus review of these cases, it was decided that the findings were artefactual and that there was no evidence of pathological signal change.

3.2 Quantitative Analysis

3.2.1 VBM

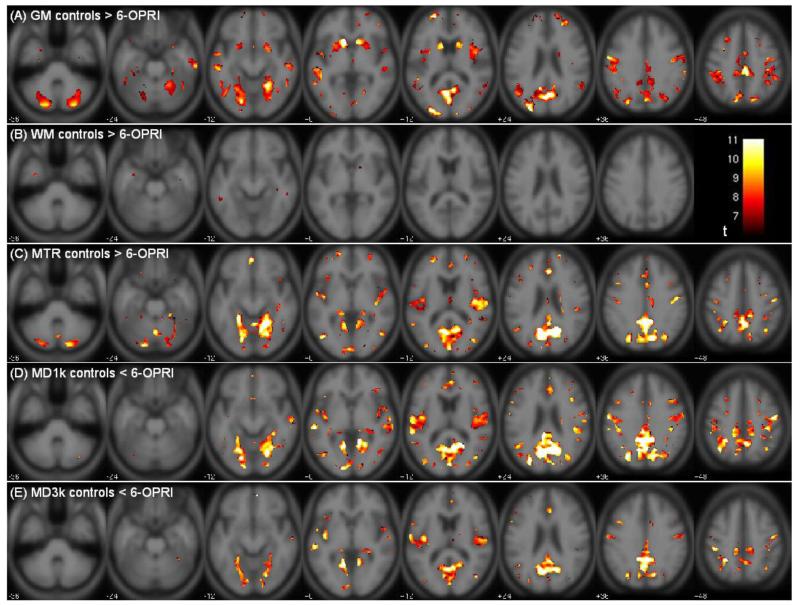

Within the supratentorial cortex, extensive bilateral symmetrical GM volume reduction was seen in the perisylvian cortex: central opercular, insular cortex, middle and superior temporal gyri; parietal cortex: angular, supramarginal and post central gyrus; and occipital cortex: lingual gyrus and cuneus. Less extensive GM reduction was also seen in the left superior frontal gyrus, and cingulate gyrus. Within the deep grey nuclei, significant GM reduction was seen in the caudate and putamen bilaterally and within the posterior fossa, the cerebellar cortex bilaterally also showed significant GM reduction (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. SPM-t maps for patients with the 6-OPRI mutation compared to controls.

SPM-t maps showing significant differences between symptomatic patients with the 6-OPRI mutation (n=9) and healthy subjects (n=16) for FWE p<0.05:(A) GM: controls>6-OPRI, t≥6.60; (B) WM: controls>6-OPRI, t≥6.07, (C) MTR: controls>6-OPRI, t≥6.86; (D) MD1k: controls<6-OPRI, t≥7.03; (E) MD3k: controls<6-OPRI, t≥6.96. The colorbar represents the t-values range.

The areas of significant WM reductions are more sparse and of smaller extent. Significant areas of WM volume reduction involved the anterior temporal lobes, the body of the corpus callosum (CC) and hippocampus bilaterally (Figure 1B). A complete list of the coordinates and corresponding anatomical locations of the significant cluster peaks (for clusters with size k>2) is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Significant clusters for WM VBM (Controls > 6-OPRI).

| k | peak p (FWE corr) | Peak T | Peak Z | x | y | z | description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 175 | <0.001 | 10.59 | 6.16 | −34 | −4 | −31 | L-TemporalFusiform and Parahippocampal gyri |

| 176 | 0.003 | 7.61 | 5.22 | −52 | −43 | −3 | L-middle Temporal gyrus |

| 0.005 | 7.37 | 5.12 | −56 | −42 | −12 | L-middle Temporal gyrus | |

| 7 | 0.017 | 6.66 | 4.83 | −54 | −29 | −8 | L-middle Temporal gyrus |

| 6 | 0.019 | 6.61 | 4.81 | −39 | −57 | 30 | L-Angular Gyrus |

| 46 | 0.006 | 7.25 | 5.08 | −25 | −31 | −13 | L-Hippocampus |

| 45 | 0.007 | 7.16 | 5.04 | −26 | −29 | −8 | L-Hippocampus and L-Parahippocampal gyrus |

| 0.03 | 6.35 | 4.69 | −20 | −34 | 6 | L-Thalamus | |

| 18 | 0.035 | 6.27 | 4.66 | −13 | 6 | −3 | L-Pallidum |

| 97 | 0.001 | 8.25 | 5.45 | 57 | −35 | −13 | R-middle Temporal gyrus |

| 0.017 | 6.67 | 4.83 | 49 | −39 | −9 | R-Inferior Temporal gyrus | |

| 0.018 | 6.66 | 4.83 | 47 | −48 | −11 | R-Inferior Temporal gyrus | |

| 148 | 0.002 | 7.82 | 5.29 | 37 | −12 | −22 | R-Temporal Fusiform gyrus |

| 0.003 | 7.72 | 5.26 | 37 | −29 | −13 | R-Temporal Fusiform gyrus | |

| 57 | 0.009 | 7.01 | 4.98 | 26 | −31 | −6 | R-Hippocampus |

| 60 | 0.012 | 6.86 | 4.92 | 13 | 8 | −3 | R-Pallidum |

| 27 | 0.004 | 7.58 | 5.21 | 2 | −22 | 19 | Midline-Body CorpusCallosum |

| 3 | 0.034 | 6.29 | 4.66 | −5 | −19 | 30 | L-Body Corpus callosum |

| 10 | 0.022 | 6.54 | 4.78 | 5 | −17 | 30 | R-Body-Corpus Callosum |

Note. K is the number of voxels within each cluster. All clusters of voxels above a voxel-level threshold FWE p<=0.05 of size k>2 are shown. For the largest clusters the table shows up to 3 local maxima more than 8mm apart. x,y,z coordinates are in MNI space. Peak-T and Peak-Z values are within each cluster

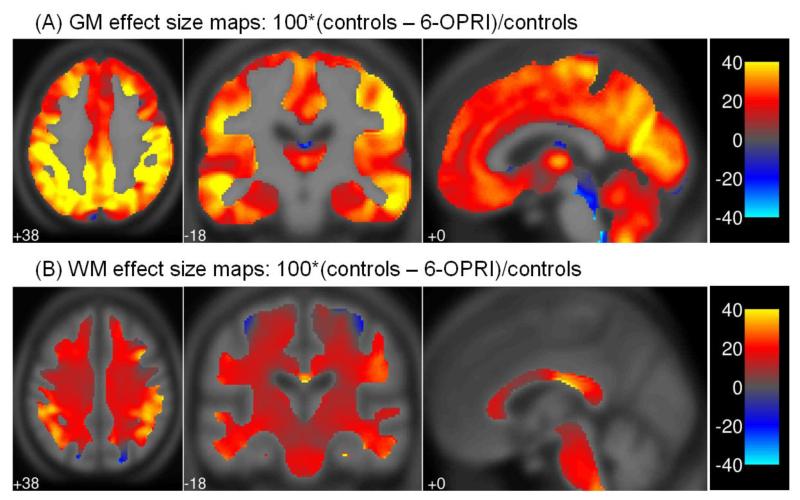

The effect maps (Figure 2A and Figure 2B) demonstrated that the largest percentage differences were present in the insular cortex, middle and superior temporal gyri, angular and supramarginal gyri, lingual gyrus and cuneus.

Figure 2. Effect size maps for all patients compared to controls and 6-OPRI compared to controls.

Effect size maps demonstrating the percentage difference between 6-OPRI and controls in (A) GM volume and (B) WM volume calculated as 100*(controls-all patients)/controls displayed in MNI space.

3.2.2 MTR

Significant MTR reductions in the 6-OPRI patients were topographically similar in the supratentorial cortex to those seen on VBM, with extensive involvement of the perisylvian regions, parietal and occipital cortex bilaterally as described above (Figure 1C). Within the deep grey nuclei, significant MTR reductions were seen in the posteromedial thalamus bilaterally only. In the posterior fossa, extensive involvement of the cerebellar cortex was seen.

In terms of number of supra-threshold voxels, changes were more anatomically extensive on MTR-VBA than VBM in the perisylvian regions, cuneus and precuneus, where there is the impression of involvement of the subcortical WM, with significant reductions in the posteromedial thalamus, not seen on VBM. However MTR-VBA did not detect significant MTR reductions in the caudate nucleus, putamena or middle temporal gyri where VBM showed differences (Figure 1C).

3.2.3 MD

MD1k

The largest clusters and most significant MD1k increases were seen in the GM and subcortical WM of the perisylvian, parietal and occipital lobes (Figure 1D) and in the posteromedial thalamus bilaterally. In terms of number of supra-threshold voxels, changes were more anatomically extensive on MD-VBA than VBM, similar to MTRVBA. No significant differences were seen in the cerebellar hemispheres, as seen on MTR, or in the basal ganglia, as seen on VBM.

MD3k

Areas of significant MD3k increase overlapped those seen with MD1k, although the extent and significance were generally smaller (Figure 1D and Figure 1E). Reduced significance could arise from either reduced effect size (group difference) or increased variability; we investigated these influences by evaluating the non-normalized group difference, and a form of coefficient of variation given by the square root of the mean squared residuals (SPM’s ResMS image) divided by the average of the 2 group means from the ANCOVA model. Both the group difference and the coefficient of variation were larger for MD1k (data not shown), suggesting the higher significance of MD1k changes is due to a greater effect size than for MD3k, and not simply higher signal-to-noise ratio.

3.4 ROI analysis

Mean values for 6-OPRI differed significantly from controls in all three ROIs for tissue-segment volumes, MTR and MD1k, and in the thalamic ROI only for MD3k (Table 3).

Table 3. Mean values for tissue segment volumes, MTR, MD1k and MD3k in selected ROIs.

| Controls | 6-OPRI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right thalamus | |||

| WM (tv)& | 0.66±0.07 | 0.57±0.05 | .002 |

| MTR (%) | 40.6±1.2 | 38.9±1.1 | .002 |

| MD1K(×10−3mm2/s) | 0.81±0.03 | 0.88±0.05 | <.001 |

| MD3K (×10−3mm2/s) | 0.63±0.01 | 0.67±0.03 | <.001 |

| Right caudate | |||

| GM (tv) | 0.74±0.07 | 0.50±0.08 | <.001 |

| MTR (%) | 37.6±1.1 | 33.8±2.2 | <.001 |

| MD1K (×10−3mm2/s) | 0.79±0.03 | 0.88±0.10 | .001 |

| MD3K (×10−3mm2/s) | 0.63±0.02 | 0.64±0.03 | ns |

| Right putamen | |||

| GM (tv) | 0.92±0.12 | 0.60±0.12 | <.001 |

| MTR (%) | 38.6±1.0 | 36.8±1.1 | .001 |

| MD1k (×10−3mm2/s) | 0.78±0.02 | 0.83±0.07 | .008 |

| MD3k (×10−3mm2/s) | 0.65±0.01 | 0.63±0.03 | .04 |

Note. Values are mean±standard deviation over subject group of the individual ROI means. ROI=region of interest, GM=grey matter, WM=grey matter, tv=modulated tissue segment fractional volume, MTR=magnetization transfer ratio, MD1k =mean diffusivity (b=1000 s/mm2), MD3k =mean diffusivity (b=3000 s/mm2).

WM is here reported since the SPM8 Segmentation routine classifies the thalamus as a predominantly WM structure.

ns= not significant (p≥0.1). P-values are reported for the Mann-Whitney U test.

4 DISCUSSION

This is the first systematic study describing the distribution of GM and WM volume changes and voxel-wise MTR and MD changes in IPD patients with the 6-OPRI mutation. We demonstrated anatomically-specific mean tissue density reduction in these patients that are consistent with previous qualitative reports. Using MTR and MD, we detected cortical and subcortical microstructural changes both coincident with and spatially-independent of tissue volume changes. Some of these changes appear to be specific to the 6-OPRI IPD mutation.

4.1 Local volume reductions assessed with VBM

Brain atrophy occurs in all forms of prion disease8,31 but most reports are based upon visual inspection rather than objective quantification. In an early case-report a presymptomatic P102L gene carrier demonstrated widespread supratentorial and cerebellar volume loss with relative sparing of mesial temporal lobe structures11. In a recent study of 6-OPRI mutation patients, significant cortical thinning was seen in the precuneus, inferior parietal cortex, supramarginal gyrus and lingula9. The present study confirms these findings, with GM volume loss in 6-OPRI patients predominantly involving the perisylvian cortex, precuneus and lingual gyrus without significant involvement of the mesial temporal lobe structures.

These cortical changes relate well to clinical symptoms documented in patients with the 6-OPRI mutation. Apraxia is an important early feature and generally associated with lesions to the dominant parietal lobe and specifically the supramarginal gyrus. Visuo-perceptual, visuo-spatial impairments known to be sensitive to right parietal damage are also common in this patient group8. The explanation for the prominent cognitive features of memory loss and frontal executive dysfunction in this patient group32 is more complex.

Although the effect size maps (Fig. 2) demonstrated some percentage difference in the mesial temporal lobes and prefrontal cortices, these volume losses were less marked compared to those in the cortical areas described above and did not prove to be statistically significant on VBM. Some of the memory and executive deficits seen in 6-OPRI mutations could be explained by subcortical pathology impacting on cortical circuits involved in these cognitive functions. This would be supported by the subcortical GM volume loss seen in the caudate nuclei and putamina, as well as the MD and MTR changes in the posteromedial thalami.

Thalamic and striatal involvement is well established in all forms of human prion disease33. The putamen and caudate nuclei receive input from diverse cortical areas, including prefrontal and limbic structures with non-motor output from the striatum projecting, via the medio-dorsal and ventro-lateral thalamic nuclei, to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, lateral orbitofrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate34.

4.2 Voxel Based Analyses of MTR and MD

The MTR-VBA and MD-VBA did not show significant change in the basal ganglia; however they demonstrated significant MTR reduction and significant MD increase in the posteromedial thalamus (not detected by VBM), cortical GM areas corresponding to those displaying VBM changes, and also in adjacent subcortical WM where no significant volume changes were detected. This suggests that MTR and MD data are a useful complement to T1-weighted structural data, and are potentially more sensitive to subcortical WM and thalamic changes in prion diseases.

4.2.1 MTR-VBA

Our MTR findings are consistent with a previous study where decreases in whole-brain and whole-GM-segment MTR compared to controls were observed in symptomatic prion disease patients, correlated with disease severity13. An association between decreased post mortem GM MTR and increased spongiosis was also seen in that study. One possible explanation for the differences in regional distribution of changes shown by MTR-VBA and VBM here is the potential of MTR to reflect microstructural pathological changes (such as spongiosis), occurring before or independent of macroscopic volume loss.

4.2.2 MD-VBA

Our findings of increased cerebral MD in patients with the 6-OPRI mutation has been reported in IPD patients11,35, specifically in the cerebellar cortex in patients with the E200K mutation18 and in the thalamus in vCJD36,37 thought to reflect increased gliosis35,36.Opposite findings of decreased MD have been reported in sCJD and patients with the E200K mutation within the basal ganglia and thalamus11,14, thought to reflect spongiform change. A relationship between macroscopic atrophy and microscopic changes reflected in increased MD may be expected; in other neurodegenerative disorders, whole brain or regional MD values usually increase in association with brain atrophy38,39. This increase in diffusivity has been associated with loss of neuronal cell bodies, synapses and dendrites causing an expansion of the extracellular space where water diffusivity is fastest40, and in prion diseases could reflect areas where neuronal loss and gliosis is becoming dominant over spongiform change, but is too subtle to be detected by VBM.

High b-value DWI, relatively more sensitive to slowly diffusing tissue water components41, provided greater pathological sensitivity for spongiform change than conventional b-value DWI in a previous study of sporadic CJD (sCJD)11 and in IPD patients with the E200K mutation who frequently mimic the sCJD phenotype14. However, in the former study, high b-value DWI was not more sensitive than convention b-value DWI for detecting increased ADC values in the pulvinar nucleus in variant CJD patients, thought to histopathologically represent gliosis. It is likely that in the context of gliosis and neuronal loss, fast diffusion components dominate the mean diffusivity, so that high b-value DWI is less sensitive, as was observed in the present study.

4.2.3 ROI Analysis

Whilst MD-VBA and MTR-VBA did not reveal significant basal ganglia changes, significant ROI MD increases and MTR decreases were seen in the thalamus, putamen and caudate in the 6-OPRI subgroup relative to controls. Voxel-based analyses may not provide a complete substitute, but rather a complement to ROI analysis, the latter potentially avoiding smoothing across inter-regional or tissue boundaries. Cross-boundary smoothing in VBA complicates interpretation, and can either reduce or increase statistical power depending on whether or not the greatest underlying changes respect the observable tissue boundaries. Inter-group differences revealed on VBA and VBM may identify pathologically-specific affected regions; these may then be more sensitively investigated on a subject-to-subject basis using ROI analysis, which may provide the most straightforward and interpretable way to monitor disease progression.

4.3 Limitations of this study

Patients with the 6-OPRI mutation were the largest mutation subgroup to undergo MRI scanning in the PRION-1 trial, and the current study represents the largest group of 6-OPRI patients for which consistent multi-parameter MRI measurements are available. Nevertheless, given the relatively small group size, our analysis should be considered preliminary.

Some types of IPD (E200K, V201I) have clinical and radiological features similar to sCJD42, but apart from patients carrying the P102L mutation9 the imaging features of other mutations are not well described in the literature. A comparison of 6-OPRI MRI findings with those from other IPD mutations would be particularly informative. Though we had access to another small set (n=8) of IPD patients with other mutations, the subgroups were too small (n=4, 1, 1, 1, 1) to achieve statistical power sufficient to provide robust conclusion on differences and similarities between mutations. Future trials enrolling larger patient numbers will be necessary for this type of analysis.

Our data suggest that in a number of brain regions MTR and MD appear ‘more sensitive’ to pathological changes than the tissue-volume data inferred from the T1-weighted acquisition. A future study with a larger data set may confirm this by seeking significant changes after adjusting for local atrophy using voxel-wise covariates (also known as biological parametric mapping, BPM)43,44. Furthermore, for our current data we underline that the specific sensitivities (and statistical power) of the individual voxel-based analyses also depend upon the acquisition signal-to-noise-ratios in the respective protocols (determined by e.g. specific sequence parameters, including nominal voxel sizes). We used the standard acquisition parameters optimized for each method at our institution: the current study was not designed to systematically compare protocols with matched signal-to-noise.

Whilst the voxel-based analyses are performed on normalized images with a nominal isotropic resolution of (1.5mm)3, the DWI and MTR source data were acquired with a larger slice thickness (5mm) compared to the nominal 1.5mm partition of the 3D structural images. Partial-volume averaging from cerebrospinal fluid at the brain surface may thus be partly responsible for the larger clusters detected proximal to the brain-CSF interfaces on MTR-VBA and MD-VBA. With this problem in mind we took care to ensure that CSF contamination did not influence the manually drawn ROIs.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This is the first multi-parameter voxel-based analysis of cerebral atrophy and microstructural changes in the 6-OPRI IPD mutation using quantitative MRI. With VBM we demonstrated regionally-specific volume loss corresponding anatomically to clinical symptoms, and providing an anatomical basis for the memory and executive function deficits seen clinically. We also showed that VBA of MTR and MD can detect microstructural changes in anatomical regions which do not demonstrate volume loss on VBM. This is likely to reflect a diverse anatomical distribution of histopathological change driven by varying pathophysiological processes. Combining regional measures from different but complementary MRI modalities, can identify brain regions preferentially involved in prion disease pathophysiology, and may provide markers of value in monitoring future therapies. Comparison of our data on 6-OPRI patients with existing literature is suggestive that the distribution of structural and microstructural changes presented here is specific to this particular IPD mutation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all patients and relatives for taking part in this study, present and past staff of the National Prion Clinic, the NHNN radiography staff, Prof. Gareth Barker for assistance with implementing the MT sequence, and Ray Young for the figures. We thank neurological and other colleagues throughout the UK for referral of patients.

FUNDING This work was supported by the UK Medical Research Council. Some of this work was undertaken at University College London Hospitals/University College London, which received a proportion of funding from the National Institute for Health Research Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme. The Dementia Research Centre is an Alzheimer’s Research UK Coordinating Centre and has also received equipment funded by Alzheimer’s Research UK. The Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging is supported by core funding from the Wellcome Trust 079866/Z/06/Z. TRACK-HD is funded by the CHDI Foundation, a not-for-profit organization dedicated to finding treatments for Huntington’s Disease.

ABBREVIATIONS

- VBM

voxel-based morphometry

- VBA

voxel-based analysis

- MTR

Magnetisation transfer ratio

- IPD

Inherited Prion Disease

- MD

mean diffusivity

REFERENCES

- 1.Collinge J. Prion Diseases. In: Ledingham JGG, Warrell DA, editors. Concise Oxford Textbook of Medicine. Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 1307–1311. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collinge J, Rossor M. A new variant of prion disease. Lancet. 1996;347:916–917. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91407-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill AF, Collinge J. Subclinical prion infection in humans and animals. British Medical Bulletin. 2003;66:161–170. doi: 10.1093/bmb/66.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llewelyn CA, Hewitt PE, Knight RS, et al. Possible transmission of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease by blood transfusion. Lancet. 2004;363:417–421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15486-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wroe SJ, Pal S, Siddique D, et al. Clinical presentation and pre-mortem diagnosis of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease associated with blood transfusion: a case report. Lancet. 2006;368:2061–2067. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69835-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mead S. Prion disease genetics. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:273–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaski DN, Pennington C, Beck J, Poulter M, Uphill J, Bishop MT, Linehan JM, O’Malley C, Wadsworth JD, Joiner S, Knight RS, Ironside JW, Brandner S, Collinge J, Mead S. Inherited prion disease with 4-octapeptide repeat insertion: disease requires the interaction of multiple genetic risk factors. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 6):1829–38. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mead S, Poulter M, Beck J, et al. Inherited prion disease with six octapeptide repeat insertional mutation--molecular analysis of phenotypic heterogeneity. Brain. 2006;129:2297–2317. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alner K, Hyare H, Mead S, et al. Distinct neuropsychological profiles correspond to distribution of cortical thinning in inherited prion disease caused by insertional mutation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(1):109–114. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox NC, Freeborough PA, Mekkaoui KF, et al. Cerebral and cerebellar atrophy on serial magnetic resonance imaging in an initially symptom free subject at risk of familial prion disease. BMJ. 1997;315:856–857. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7112.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyare H, Thornton J, Stevens J, et al. High-b-value diffusion MR imaging and basal nuclei apparent diffusion coefficient measurements in variant and sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:521–526. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyare H, Wroe S, Siddique D, et al. Brain-water diffusion coefficients reflect the severity of inherited prion disease. Neurology. 2010;74:658–665. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d0cc47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siddique D, Hyare H, Wroe S, et al. Magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) may be a surrogate of spongiform change in human prion diseases. Brain. 2010 Oct;133:3058–3068. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H, Hoffman C, Kingsley PB, Degnan A, et al. Enhanced Detection of Diffusion Reductions in Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease at a Higher B Factor. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(1):49–54. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Voxel-based morphometry--the methods1. Neuroimage. 2000;11:805–821. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee H, Rosenmann H, Chapman J, et al. Thalamo-striatal diffusion reductions precede disease onset in prion mutation carriers. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 10):2680–7. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee H, Cohen OS, Rosenmann H, et al. Cerebral White Matter Disruption in Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33(10):1945–50. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen OS, Hoffmann C, Lee H, et al. MRI detection of the cerebellar syndrome in Creutzfeldt-Jacob Disease. Cerebellum. 2009;8(3):373–8. doi: 10.1007/s12311-009-0106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collinge J, Gorham M, Hudson F, et al. Safety and efficacy of quinacrine in human prion disease (PRION-1 study): a patient-preference trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(4):334–344. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70049-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (Cdr) - Current Version and Scoring Rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stejskal EO, Tanner JE. Spin diffusion measurements: spin echoes in the presence of a time dependent field gradient. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1965;42:288–292. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barker, et al. Barker GJ, Schreiber WG, Gass A, et al. A standardised method for measuring magnetisation transfer ratio on MR imagers from different manufacturers--the EuroMT sequence. MAGMA. 2005;18(2):76–80. doi: 10.1007/s10334-004-0095-z. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barker GJ, Tofts PS, Gass A. An interleaved sequence for accurate and reproducible clinical measurement of magnetization transfer ratio. Magn Reson Imaging. 1996;14(4):403–11. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(96)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Unified segmentation. Neuroimage. 2005;26:839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashburner J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage. 2007;38:95–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mechelli A, Price CJ, Friston KJ, et al. Voxel-Based Morphometry of the Human Brain: Methods and Applications. Current Medical Imaging Reviews. 2005;1(2):105–113. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ourselin S, Roche A, Subsol G, et al. Reconstructing a 3D structure from serial histological sections. Image and Vision Computing. 2001;19:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ourselin S, et al. Robust registration of multi-modal images: Towards real-time clinical applications. MICCAI; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridgway GR, Omar R, Ourselin S, et al. Issues with threshold masking in voxel-based morphometry of atrophied brains. Neuroimage. 2009;44:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arata H, Takashima H, Hirano R, et al. Early clinical signs and imaging findings in Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker syndrome (Pro102Leu) Neurology. 2006;66:1672–1678. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000218211.85675.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cordery RJ, Alner K, Cipolotti L, et al. The neuropsychology of variant CJD: a comparative study with inherited and sporadic forms of prion disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2005;76:330–336. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.030320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aguzzi A, Weissmann C. Prion diseases. Haemophilia. 1998;4:619–627. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.1998.440619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Middleton FA, Strick PL. Basal-ganglia ‘projections’ to the prefrontal cortex of the primate. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:926–935. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.9.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haik S, Galanaud D, Linguraru MG, et al. In Vivo Detection of Thalamic Gliosis: A Pathoradiologic Demonstration in Familial Fatal Insomnia. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:545–549. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oppenheim C, Brandel JP, Hauw JJ, et al. MRI and the second French case of vCJD. Lancet. 2000;356:253–254. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74505-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waldman AD, Jarman P, Merry RT. Rapid echoplanar diffusion imaging in a case of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease; where speed is of the essence. Neuroradiology. 2003;45(8):528–531. doi: 10.1007/s00234-003-1050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kantarci K, Jack CR, Jr, Xu YC, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease: regional diffusivity of water. Radiology. 2001;219(1):101–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.1.r01ap14101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mascalchi M, Lolli F, Della Nave R, et al. Huntington disease: volumetric, diffusion-weighted, and magnetization transfer MR imaging of brain. Radiology. 2004;232(3):867–73. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2322030820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kantarci K, Petersen C, Boeve BF, et al. DWI predicts future progression to Alzheimer disease in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2005;64:902–904. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000153076.46126.E9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niendorf T, Dijkhuizen RM, Norris DG, et al. Biexponential diffusion attenuation in various states of brain tissue: implications for diffusion-weighted imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:847–857. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Breithaupt M, Romero C, Kallenberg K, Begue C, Sanchez-Juan P, Eigenbrod S, Kretzschmar H, Schelzke G, Meichtry E, Taratuto A, Zerr I. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in E200K and V210I Mutations of the Prion Protein Gene. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012 Mar 8; doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31824d578a. [Epub ahead of print] PMID:22407223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Casanova R, Srikanth R, Baer A, et al. Biological parametric mapping: A statistical toolbox for multimodality brain image analysis. Neuroimage. 2007;34(1):137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oakes TR, Fox AS, Johnstone T, et al. Integrating VBM into the General Linear Model with voxelwise anatomical covariates. Neuroimage. 2007;34(2):500–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]