Abstract

Assimilation of nitrogen is an essential process in bacteria. The nitrogen regulation stress response is an adaptive mechanism used by nitrogen-starved Escherichia coli to scavenge for alternative nitrogen sources and requires the global transcriptional regulator NtrC. In addition, nitrogen-starved E. coli cells synthesize a signal molecule, guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp), which serves as an effector molecule of many processes including transcription to initiate global physiological changes, collectively termed the stringent response. The regulatory mechanisms leading to elevated ppGpp levels during nutritional stresses remain elusive. Here, we show that transcription of relA, a key gene responsible for the synthesis of ppGpp is activated by NtrC during N starvation. The results reveal that NtrC couples these two major bacterial stress responses to manage conditions of nitrogen limitation, and provide novel mechanistic insights into how a specific nutritional stress leads to elevating ppGpp levels in bacteria.

Nitrogen (N) is an essential element of most macromolecules in a bacterial cell, including proteins, nucleic acids and cell wall components. Bacteria can assimilate a variety of N sources and ammonia typically supports the fastest growth, serving as the preferred N source for many bacteria including E. coli1. During N limited growth ammonia is converted by glutamine synthetase into glutamine, the primary amine donor for key amino acid and nucleotide biosynthetic pathways. E. coli cells respond to N starvation by activating the nitrogen regulation (Ntr) stress response, resulting in the expression of approximately 100 genes to facilitate N scavenging from alternative sources of combined N (ref 2). In enterobacteria, the master transcription regulator of the Ntr stress response is NtrC of the NtrBC two-component system3. N limitation results in the phosphorylation of the response regulator NtrC (product of glnG) by its cognate sensor kinase NtrB (product of glnL).

N starved E. coli cells rapidly synthesize ppGpp, the effector alarmone of the bacterial stringent response4. Two enzymes modulate the levels of ppGpp in E. coli: the ppGpp synthetase RelA and ppGpp synthetase/hydrolase SpoT5. RelA and SpoT contribute to stress adaptation, antibiotic tolerance, expression of virulence traits and the acquisition of persistent phenotype in pathogenic bacteria6-9. The regulation of RelA/SpoT enzyme activities has been extensively studied10-13, but the regulatory mechanisms that govern transcription of their genes and thereby lead to elevated ppGpp levels during nutritional stresses remain elusive.

Here, we address the links between the Ntr stress response and the ppGpp alarmone. To gain insight into NtrC-dependent gene networks, we map the genome-wide binding targets of NtrC and RNA polymerase (RNAp) during N starvation in E. coli, using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq). Our results reveal that nitrogen stress response and stringent response are coupled in E. coli.

Results

Tooling up to study genome-wide binding of NtrC and RNAp

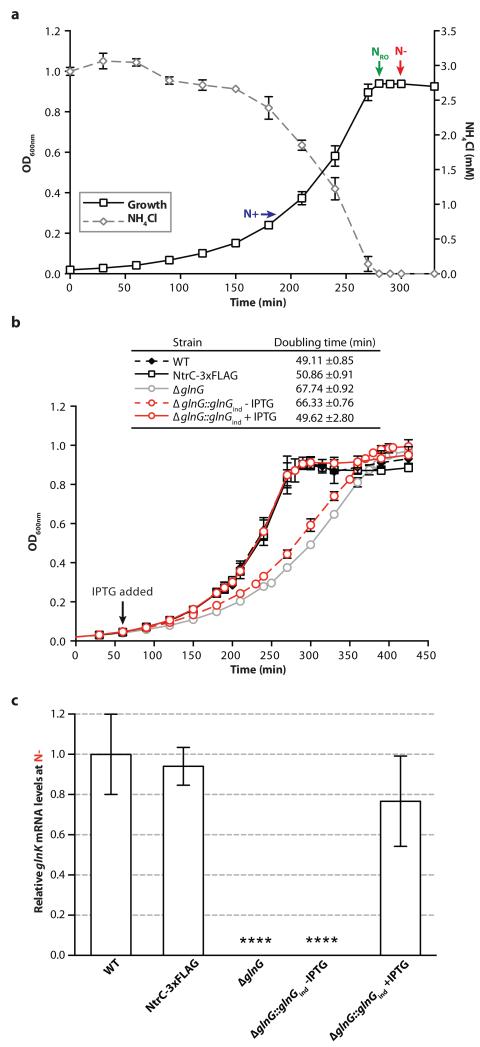

To identify genome regions preferentially associated with NtrC, we introduced an in-frame fusion encoding three repeats of the FLAG epitope at the 3′ end of glnG in E. coli strainNCM3722, a prototrophic E. coli K-12 strain. To establish N starved conditions, we grew batch cultures of the wild-type NCM3722 strain in Gutnick minimal medium supplemented with a limiting amount (3mM) of NH4Cl as the sole N source, and monitored bacterial growth as a function of ammonium consumption. In Fig. 1A, the time when wild-type NCM3722 stops growing (t=NRO) coincides with the ammonium run out ([ammonium]<0.000625mM) in the growth medium. To establish the FLAG epitope had not compromised the activity of NtrC, we measured the doubling times of wild-type NCM3722, NCM3722:glnG-FLAG and NCM3722:ΔglnG strains under our growth conditions. The doubling time of theNCM3722:glnG-FLAG strain is close to that of the wild-type NCM3722 strain; however, as expected, the doubling time of the NCM3722:ΔglnG strain is longer than that of the wild-type NCM3722 strain (Fig. 1B). Further, the expression levels of glnK mRNA, an Ntr stress response gene directly activated by NtrC, at t=N− (i.e. the time-point 20 minutes after N runs out) is similar in the wild-type NCM3722 and NCM3722:glnG-FLAG strains, and as expected is not readily detected in the NCM3722:ΔglnG strain (Fig. 1C). Complementation of the NCM3722:ΔglnG strain with inducible plasmid-borne glnG restored both the doubling time and glnK mRNA expression (Fig. 1B and 1C). In summary, we conclude that: (i) FLAG-tag has not adversely affected biological activity of NtrC and (ii) under our experimental conditions t=N− is representative of the time when the E. coli cells are starved for N.

Figure 1. Establishing N starved growth conditions in E. coli.

(A) The growth arrest of wild-type E. coli NCM3722 cells coincides with ammonium run out (at t=NRO) in the minimal Gutnick medium. The time points at which the E. coli cells were sampled for downstream analysis are indicated (t=N+ and t=N− represents growth under nitrogen replete and starved conditions, respectively). (B) The growth curves of wild-type NCM3722, NCM3722:glnG-FLAG (NtrC-3xFLAG), NCM3722:ΔglnG and NCM3722:ΔglnG::glnGind (−/+ IPTG). The quantitation of the doubling times is also given. (C) Graph showing the relative levels of glnK mRNA expression as fold-change in cells sampled at t=N+ and t=N−. Error bars on all growth curves represent SD (where n=3). Statistical significant relationships from One-way ANOVA analysis are denoted (****P<0.0001).

NtrC binds upstream of relA in N starved E. coli

To identify the genomic loci bound by NtrC in E. coli during N starvation, we sampled cells for ChIP-seq analysis at t=N− and NtrC bound DNA was precipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies. To identify transcriptionally active promoters in E. coli during N starvation, we treated the E. coli cells at t=N− with rifampicin for 15 minutes (rifampicin inhibits transcription elongation and thus transcription-initiated RNAp molecules will become trapped at any functional promoter14,15) and RNAp bound DNA was precipitated with a monoclonal antibody against the β subunit of the RNAp. The ChIP-seq data revealed that NtrC bound upstream of at least 21 transcription units at t=N−. RNAp binding (in the presence and absence of Rif treatment) to promoter regions of all 21 transcription units and differential gene expression analysis (t=N− vs. t=N+) indicate that all 21 transcription units are upregulated at t=N− (Table 1, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Fourteen of the 21 transcription units are known members of the NtrC regulon (Table 1)2. However, none of the 7 remaining transcription units (flgMN, dicC, fliC, relA, ssrS, soxR and yjcZ-proP) have been previously demonstrated to require NtrC for their transcriptional regulation. Therefore we tested NtrC binding to these regions by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) with purified E. coli NtrC and DNA probe sequences (designed following ChIP-seq analysis) upstream of: flgMN, dicC, fliC, relA, ssrS, soxR and yjcZ-proP (referred to as flgN, dicC, fliC, relA, ssrS, soxR and yjcZ probes). As a positive control the region upstream of the glnALG the operon (referred to as the glnA probe) was used. The in situ phosphorylated NtrC (NtrC-P) bound to the relA and positive control glnA probes (Fig. 2A) but not the other probes (Supplementary Fig. 2). ChIP-seq data indicates the NtrC binding site is located between positions −838 and −649 upstream from the translational start of RelA. Since complex formation between NtrC-P and flgN, dicC, fliC, ssrS, soxR and yjcZ probes is not detectable even at a higher concentration of NtrC-P (Supplementary Fig. 2) and the DNA regions are poorly enriched by NtrC binding in the ChIP-seq data (Table 1), we consider that flgN, dicC, fliC, ssrS, soxR and yjcZ are unlikely to be solely dependent upon NtrC. We do not exclude the possibility that the upstream regions of flgN, dicC, fliC, ssrS, soxR and yjcZ transcription units contain intrinsically poor NtrC binding sites which function in co-dependence with other transcription factors (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Summary of genome-wide binding sites of NtrC in N starved E. coli determined by ChIP-seq.

| Peak number | Genomic loci | Fold | P-value | Gene/Operon | Pathway/process | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 471741-471821 | 39.71 | 0.0004 | glnK-amtB | GlnK - Nitrogen regulatory protein, AmtB - ammonia transport | Gene expression analysis 2 |

| 2 | 688381-688461 | 55.29 | 0.0003 | gltIJKL | Glutamate / aspartate ABC transport | Gene expression analysis 2 |

| 3 | 847261-847341 | 74.78 | 0.0002 | glnHPQ | Glutamine ABC transporter | Direct binding37, gene expression analysis 2 |

| 4 | 1073221-1073301 | 94.03 | 0.0001 | ycdMLKJIHG | Pyrimidine degradation | Gene expression analysis 2 |

| 5 | 1129181-1129261 | 13.65 | 0.0022 | flgMN | Regulation of flagellar synthesis and flagellar biosynthesis protein | |

| 6 | 1561101-1561181 | 24.1 | 0.0009 | ddpXABCDF | D-ala-D-ala dipeptide transport and dipeptidase | Gene expression analysis 2 |

| 7 | 1646021-1646101 | 9.49 | 0.0042 | dicC | DNA-binding transcriptional repressor | |

| 8 | 1830021-1830101 | 23.35 | 0.0009 | astCADBE | Arginine catabolic pathway | Direct binding38, gene expression analysis 2 |

| 9 | 1864821-1864901 | 12.11 | 0.0027 | yeaGH | Unknown (YeaG is a serine protein kinase) | Gene expression analysis 2 |

| 10 | 2001461-2001541 | 9.11 | 0.0045 | fliC | Flagellar biosynthesis component | |

| 11 | 2059941-2060021 | 59.59 | 0.0002 | nac-cbl | Nitrogen limitation response- adapter for σ70 dependent genes | Gene expression analysis 2 |

| 12 | 2424941-2425021 | 23.73 | 0.0009 | hisJQMP | Histidine ABC transporter | Gene expression analysis 2 |

| 13 a | 2425861-2425941 | 5.38 | 0.015 | argT | lysine / arginine / ornithine ABC transporter | Gene expression analysis 2 |

| 14 | 2912341-2912421 | 13.89 | 0.0022 | relA | GDP pyrophosphokinase involved in stringent response | |

| 15 | 3054061-3054141 | 10.4 | 0.0036 | ssrS | 6S RNA involved stationary phase regulation of transcription | |

| 16 | 3217421-3217501 | 10.64 | 0.0035 | ygjG | Putrescine degradative pathway | Gene expression analysis 2 |

| 17 | 3416981-3417061 | 16.21 | 0.0017 | yhdWXYZ | Polar amino acid transport | Gene expression analysis 2 |

| 18 | 4056061-4056141 | 70.98 | 0.0002 | glnALG | Glutamine biosynthesis pathway (ammonia assimilation) & nitrogen regulation | Direct binding 39,40 Gene expression analysis 2 |

| 19 | 4054381-4054461 | 9.42 | 0.0042 | glnLG | NtrBC two component system - nitrogen regulation | Direct binding41, gene expression analysis 2 |

| 20 | 4275021-4275101 | 10.22 | 0.0037 | soxR | SoxR transcriptional regulator | |

| 21 | 4327301-4327381 | 11.7 | 0.0029 | yjcZ-proP | Hypothetical protein (YjcZ), osmolyte:H+ symporter (ProP) |

Miscalled peak by SISSRs, added from visual interpretation of the ChIP-seq results

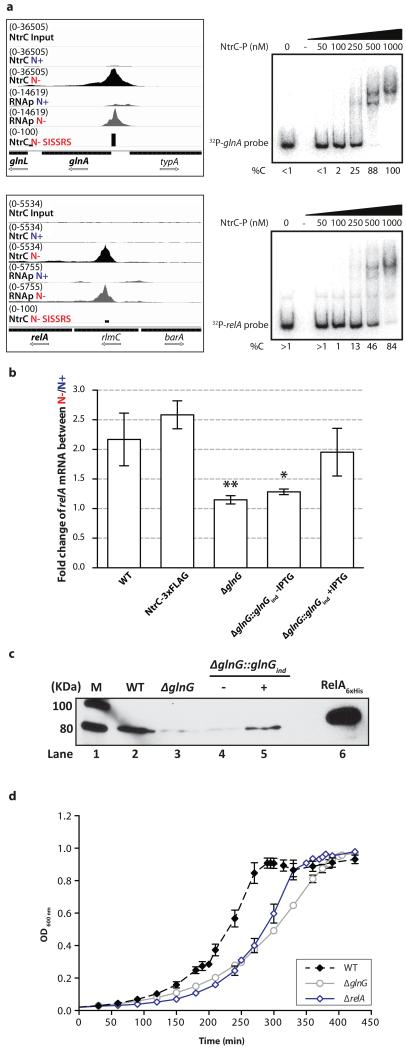

Figure 2. NtrC binds to a site upstream of relA in N starved E. coli.

(A) Left. Shown are screenshots of Integrative Genome Viewer with tracks showing the binding profiles (tag density) as measured by ChIP-seq of NtrC (black) and RNAp (grey) in N non-starved (denoted as N+) and N starved (denoted as N−) E. coli aligned against the upstream regions of glnA and relA. Tracks with the input DNA control tag density (denoted as input) and with the genomic loci bound by NtrC identified by the peak-calling algorithm Site Identification for Short Sequence Reads (denoted as SISSRS) at t=N− are also shown for comparison. Right. Representative autoradiographs of non-denaturing gels showing the binding of NtrC to 32P-labelled DNA probes with sequences corresponding to the upstream regions of glnA (positions –273 to +71 relative to the translation-start site of GlnA) and relA (positions −928 to −592 relative to the translation-start site of RelA). The %C indicates the percentage of DNA bound by NtrC in comparison to unbound DNA in lane 1. (B) Graph showing the relative levels of relA mRNA expression as fold-change in cells sampled at t=N+ and t=N−. The error bars represent SD and statistical significant relationships from one-way ANOVA analysis are denoted (*P<0.05; **P<0.01). (C) Representative autoradiograph of a Western blot (full gel image in Supplementary Fig. 8) showing expression of RelA proteins in cells sampled at t=N−. Lane 1 contains the molecular weight marker and lane 6 contains purified E. coli RelA-6xHis protein. (D) The growth curves of wild-type NCM3722, NCM3722:ΔglnG and NCM3722:ΔrelA.

NtrC activates relA transcription in N starved E. coli

To unambiguously establish that relA transcription is activated by NtrC during N starvation we measured relA mRNA levels in wild-type NCM3722 and NCM3722:ΔglnG strains at t=N− relative to t=N+. In the wild-type NCM3722 strain the level of relA mRNA expression is ~2.2±0.4-fold at t=N− relative to t=N+, and no detectable increase in the relA mRNA expression is seen in the NCM3722:ΔglnG at t=N− relative to t=N+ (Fig. 2B). The complementation of the NCM3722:ΔglnG strain with inducible plasmid-borne glnG restored relA mRNA expression in the NCM3722:ΔglnG:glnGind strain to levels comparable to that of the wild-type NCM3722 strain in the presence of the inducer isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Fig. 2B). To determine if synthesis of the RelA protein correlates with NtrC dependent activation of relA transcription, we probed whole-cell extracts of the wild-type NCM3722, NCM3722:ΔglnG and NCM3722:ΔglnG::glnGind strains sampled at t=N− with monoclonal antibody to E. coli RelA. As expected, RelA protein was not detected in whole-cell extract prepared from the NCM3722:ΔglnG strain and NCM3722:ΔglnG::glnGind strain in the absence of IPTG (Fig. 2C, lanes 3 and 4); however, RelA protein was detected in whole-cell extracts prepared from the NCM3722:ΔglnG::glnGind strain in the presence of IPTG (Fig. 2C, lane 5). These results support our ChIP-seq data and demonstrate that accumulation of RelA in E. coli is NtrC dependent during N starvation. Further the growth of NCM3722:ΔglnG and NCM3722:ΔrelA strains under N-limiting conditions is similar (Fig. 2D), thus indicating that NtrC-dependent activation of RelA is important for the tolerance of N stress.

A novel σ54-dependent promoter drives transcription of relA

NtrC exclusively activates transcription from promoters used by RNAp containing the major variant bacterial σ factor, σ54 (ref. 16). At such promoters, hexamers of phosphorylated NtrC bind to enhancer-like sequences located approximately 100-150 nucleotides upstream of the transcription start site and in a reaction hydrolysing adenosine triphosphate (ATP), convert a transcriptionally-inactive initial σ54-RNAp-promoter complex to a transcriptionally-active one17. A previous study revealed that two promoters, P1 and P2, which are utilized by the housekeeping σ70-RNAp, drive the transcription of relA18. The P1 promoter is constitutively active but upon entry into stationary phase, relA transcription is driven by P2 and it is thought that transcription from P2 is influenced by the global transcriptional regulator cAMP receptor protein (CRP). To identify σ54-RNAp dependent promoter(s) responsible for driving NtrC-dependent transcription of relA, we carried out 5′-RACE analysis of relA mRNA isolated from N starved wild-type NCM3722 and NCM3722:ΔglnG E. coli cells and mapped the transcription start sites (TSS). Results shown in Supplementary Fig. 4A indicate that (i) in N starved E. coli, relA is transcribed from three different promoters, the constitutive σ70-RNAp dependent P1 promoter and two new promoters, which we refer to as P3 and P4 and (ii) transcription from P3 and P4 is dependent on NtrC. Transcription from the σ70-RNAp dependent P2 promoter was only detected in the NCM3722:ΔglnG cells, indicating that σ54-RNAp binding to the P4 promoter (which is located immediately adjacent to the P2 promoter and overlaps the CRP binding site; Supplementary Fig. 4B) is likely to antagonize efficient transcription initiation from P2 under N starvation (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Inspection of the DNA region immediately upstream of the TSS of the P3 and P4 transcripts revealed two conserved sequences typical of a σ54-RNAp dependent promoter19 (Supplementary Fig. 4B). Since the ChIP-seq data indicates that the DNA region from −811 to −607 (with respect to the translation start site of RelA) is enriched for RNAp binding and spans the P4 promoter (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 4B), we suggest that NtrC preferentially activates transcription from the P4 promoter in N starved E. coli rather than from the P3 promoter. To demonstrate in vitro that P4 represents a bona fide NtrC and σ54-RNAp dependent promoter, we conducted a small primed RNA (spRNA) synthesis assay20 using purified E. coli NtrC, σ54 and RNAp and using purified E. coli NtrC, σ54 and RNAp and a promoter DNA fragment (encompassing sequences −261 to +75 with respect to P4 TSS) and thus containing the NtrC binding site and P4 promoter region. Since the sequence of the template strand at P4 is GACC (position −1 to +3), we used the spRNA assay to monitor the accumulation of the 32P labelled and dinucleotide CpU primed RNA product (CpUpGpG) in the presence α32P-GTP. The CpUpGpG RNA product is only synthesised under conditions when NtrC is phosphorylated in situ with carbamyl phosphate and σ54-RNAp is present (Supplementary Fig. 4C, lanes 4 and 5). Notably, an alignment of the relA regulatory sequences from several representatives of the Enterobacteriaceae family indicates that the regulatory mechanism involving NtrC and the σ54-RNAp that governs the transcription of relA under N starvation is conserved (Supplementary Fig. 5).

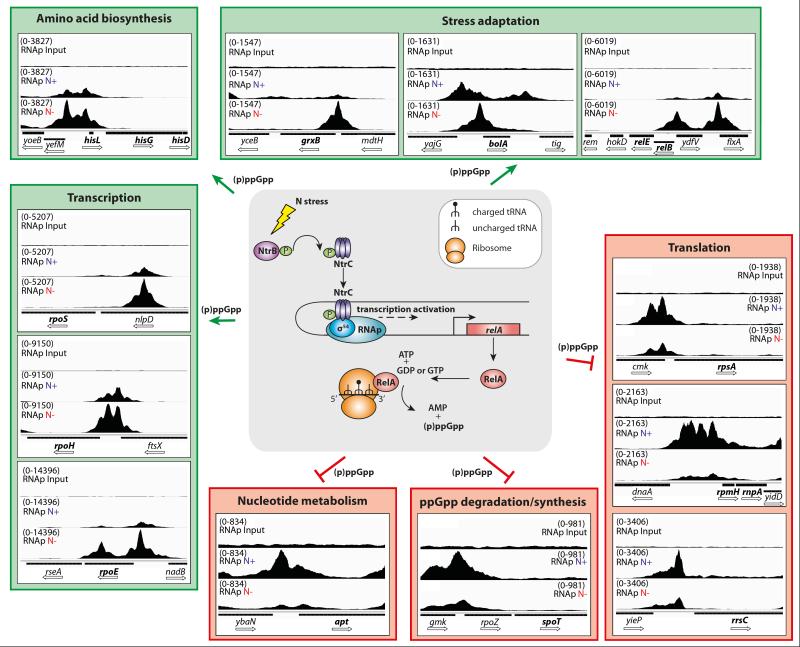

NtrC couples the Ntr and stringent responses in E. coli

Zimmer et al.2 previously concluded that the Ntr stress response represents a scavenging response since many of the NtrC activated genes encode transport systems of N containing compounds. The new results provided in this study reveal that during N starvation E. coli uses NtrC to integrate the need to scavenge for N with stringent-response mediated changes that enable cells to adapt to low N availability. By directly activating the expression of RelA and so elevating the intracellular concentration of ppGpp, the effector molecule of stringent response, cells are expected to further reprogram gene expression. In support of this view, a small increase in relA expression has been shown to profoundly increase intracellular ppGpp levels12. Since transcription initiation is a major regulatory target of ppGpp, which binds to the RNAp and either positively or negatively affects its ability to form transcriptionally-proficient complexes with the promoter8,9,21,22, we examined the binding profiles of RNAp under N+ and N− growth conditions at 60 ppGpp responsive promoters listed on the EcoCyc database23. The results reveal the expected RNAp binding profiles at 35 of the 60 ppGpp responsive promoters thereby clearly demonstrating that NtrC stimulates the stringent response in N starved E. coli (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 6). RNAp binding is positively affected at promoters of genes involved in transcriptional reprogramming (e.g. rpoS, rpoH and rpoE), amino acid biosynthesis (e.g. hisLGDCBHAFI) and stress adaptation (e.g. bolA, relEB and grxB). RNAp binding is negatively affected at promoters of genes involved in translation (e.g. rpsA, rmpH, rnpA, rrsC), nucleotide metabolism (e.g. apt) and ppGpp degradation (spoT). However, RNAp binding at 22 of the 60 ppGpp responsive promoters is unaffected in N starved E. coli and 3 display altered binding that is not expected (Supplementary Fig. 6,). Results from differential gene expression analysis (t=N− vs. t=N+) are consistent with the ChIP-seq data to a large extent and reveal that 37/60 promoters display the expected transcriptional activity at t=N− (Supplementary Table 1). In E. coli and several other bacteria, ppGpp is also the major regulator of bacterial persistence, a phenomenon characterised by slow growth and tolerance to antibiotics and other environmental stresses; a family of genes known as toxin-antitoxin (TA) pairs play a pivotal role in the acquisition of the persistence phenotype6. We note that RNAp binds to promoters of 9 of the 12 TA genes found in E. coli under N− but not N+ conditions, thus implying that N starvation could cause a shift towards a persistent phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Figure 3. NtrC couples the Ntr stress response and stringent response in N starved E. coli.

The cartoon in the middle of the figure represents the model by which N starvation is sensed and leads to the NtrC mediated activation of transcription of relA, which subsequently leads to the production of ppGpp. Around this cartoon, we show screenshots of Integrative Genome Viewer32 with tracks showing the binding profiles (tag density) as measured by ChIP-seq of RNAp binding in N non-starved (denoted as N+) and N starved (denoted as N−) E. coli aligned against the upstream regions of a representative set of known ppGpp responsive promoters grouped into key cellular processes. A track with the input DNA control tag density (denoted as input) is shown for comparison. The screenshots in the green and red boxes denote promoters at which RNAp binding is positively and negatively, respectively, affected by ppGpp.

Discussion

The principal finding of this study is that NtrC, the master regulator of the Ntr stress response, activates the transcription of relA from a σ54-dependent promoter in N starved E. coli and other members of the Enterobacteriaceae family. A physiological theme for σ54-dependent gene regulation has yet to emerge, as the σ54-dependent genes described to date control a diverse set of cellular processes 24,25. The finding that transcription of relA in N starved E. coli exclusively depends on the RNAp containing the σ54 promoter specificity factor further underscores the fundamental importance of σ54 to bacterial physiology. Previous studies demonstrated that the Ntr stress response is amplified through the transcriptional activation of the global transcription factor nitrogen assimilation control protein (Nac) by NtrC2,26. Our results reveal a far wider ranging control of genes occurs through a direct interface of the master Ntr stress response transcription activator NtrC with the bacterial stringent response system. The results predict that NtrC-mediated activation of RelA expression will lead to elevated intracellular levels of ppGpp, which, although consistent with multiple independent observations from gene expression and ChIP-seq data, requires to be directly confirmed in future studies. Nevertheless, the discovery that the regulation of RelA expression, which synthesises one of the major effectors of stringent response, ppGpp, is integrated into the Ntr stress response in N starved E. coli and possibly in other enteric bacteria provides a paradigmatic example of the dynamic complexity of bacterial transcription regulatory networks. Such behaviour allows bacteria to efficiently adapt to nutritional adversity and demonstrates how bacteria may acquire new metabolic states in response to stress.

Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth conditions

All strains used in this study were derived from E. coli NCM3722, a derivative of E. coli K-12 strain MG1655. The NCM3722:ΔglnG strain was constructed as described previously 27; briefly, the knockout glnG allele was transduced using the P1vir bacteriophage with JW3839 from the Keio collection 28 serving as the donor strain and NCM3722 as the recipient strain. The kanamycin cassette was then cured from the strain using pCP20 leaving an unmarked knockout mutation. The NCM3722:ΔrelA strain was constructed in the same way with E. coli JW2755 (Keio collection) serving as the donor strain 28. The NCM3722:glnG-FLAG strain (NtrC-3xFLAG) was constructed by introducing an in-frame fusion encoding three repeats of the FLAG epitope (3x (gat tac aag gat gac gat gac aag)), to the 3′ end of glnG. A glnG inducible complementing plasmid (pAPT-glnG-rbs31) was kindly provided by Baojun Wang 29. Bacteria were grown in Gutnick media (33.8 mM KH2PO4, 77.5 mM K2HPO4, 5.74 mM K2SO4, 0.41 mM MgSO4), supplemented with Ho-LE trace elements 30 and 0.4% glucose, and containing either 10 mM NH4Cl (for precultures) or 3 mM NH4Cl (runout experiments) as the sole nitrogen source at 37°C, 200 rpm. Ammonium concentrations in the media were determined using the Aquaquant ammonium quantification kit (Merck Millipore, U.K.), according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Antibodies

For immunoblotting, commercial mouse monoclonal anti-RelA (5G8) (at a diution of 1/200) was used (Santa Cruz, U.S.A.) in conjunction with anti-mouse ECL horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked secondary antibody (at a dilution of 1/10,000) (GE Healthcare, U.K.). For chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), mouse monoclonal anti-Flag (M2, Sigma-Aldrich, U.K.), 10 μl per individual immunoprecipitation experiment, and mouse monoclonal antibody to β subunit of E. coli RNAp (WP002 Neoclone, U.S.A.), 4 μl per individual immunprecipitation experiment, were used.

ChIP-seq

Cells were grown as stated above in Gutnick minimal media, when growth reached the correct stage (for N+, when OD600nm = 0.3, and for N−, 20 min after growth arrest due to nitrogen runout) samples were taken and cells were subjected in vivo cross-linking with the addition of formaldehyde (Sigma, U.K.) (final concentration 1% (v/v)). For RNAp-rif ChIP only, cells were subjected to a 15 min treatment with rifampicin (final concentration 150 μg/ml) at 37°C prior to cross-linking. Cross-linking was carried out for 20 min at 37°C before it was quenched by the addition of glycine (final concentration 450 mM) for 5 min at 37°C. Cells were harvested from 20 ml of culture by centrifugation, washed twice in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.5) and pellets were frozen at −80°C until required. To fragment the cellular DNA thawed pellets were resuspended in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 0.1% (w/v) Na deoxycholate, 0.1% (w/v) SDS) supplemented with Complete Protease Inhibitor (Roche, U.K.) before sonication (100% amplitude, 30 sec pulses for 10 min) (Misonix Ultrasonic Processor S-4000), this resulted in fragments of 200-400 bp. Cell-debris was removed by centrifugation and the supernatant recovered for IP. A 100 μl aliquot of the supernatant was removed and stored at −20°C to act as the ‘input’ sample which would serve as the background control for ChIP-seq, this sample was de-crosslinked and subjected protein degradation as described for the ‘test’ samples.

Either anti-FLAG (M2) or anti-β (WP002) were added to the remaining supernatant (~750 μl) and incubated overnight at 4°C on a rotating wheel (a no-antibody control IP was set up at this point also). Sheep anti-Mouse IgG Dynal beads (Invitrogen, U.K.) were prepared by washing 2x with Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 2x with IP buffer, prior to saturating the beads (IP buffer supplemented with Complete protease inhibitor and 1 mg/ml BSA) overnight at 4°C on a rotating wheel. The blocking solution was removed by applying the beads to a magnet (which was the method used throughout the IP to harvest bead complexes) and removing the supernatant, antibody-nucleoprotein complex was added and incubated for 2 h at 4°C on a rotating wheel. Bead-antibody-nucleoprotein complexes were harvested and subjected to a series of washing steps; 2x IP buffer, 1x IP salt buffer (IP buffer + 0.5 M NaCl), 1x Wash buffer III (10 mM Tris pH 8, 250 mM LiCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet-P40, 0.5% (w/v) Na deoxycholate) and a final wash in TE buffer (50 mM Tris, 10 mM EDTA pH 7.5). Immunoprecipitated complexes were then eluted from the beads using an elution buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM EDTA, 1% (w/v) SDS) and incubation at 65°C for 40 min with regular agitation. Beads were removed using the magnet and the eluate carefully removed and diluted 2-fold in nuclease-free water (VWR, U.K.). DNA was purified from the eluate by de-crosslinking and degrading the protein by incubation at 42°C for 2 h and 65°C for 6 hours in the presence of Pronase (final concentration 4 mg/ml) prior to Qiagen MiniElute Kit purification (this was carried out for the ‘input’ sample described above also). DNA was quantified using the high sensitivity dsDNA Qubit assay (Invitrogen, U.K.).

Libraries of ChIP-purified DNA were prepared to allow multiplex next generation sequencing using Illumina TruSeq™ DNA sample preparation kit v2 (Illumina, U.S.A.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with the following modifications. 10 ng of ChIP-purified DNA was used to construct each library, barcoded adapters were diluted 10-fold to compensate for the lower DNA amount. An additional 5 cycle PCR was added prior to size selection of libraries to improve yields (PCR completed as described in amplification of libraries in the kit with PCR primers provided), also an additional gel extraction step was added following final PCR amplification to remove excess primer dimers. PCR amplification for NtrC ChIP libraries was completed using KAPA HiFi HotStart Readymix (Kapa Biosystems, U.S.A.) instead of the kit polymerase as this improved amplification of libraries. Size and purity of DNA was confirmed using high sensitivity DNA analysis kit on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyser (Agilent, U.S.A.). DNA libraries were multiplexed and sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq2000, which generated approximately 10 million reads per sample. Reads were mapped to the complete genome of E. coli strain MG1655 (NCBI reference sequence: NC_000913.2) using Bowtie 31. Reads were visualized and screenshots prepared using Integrative Genome Viewer (IGV) 32. All ChIP-seq data files have been deposited into ArrayExpress (accession code E-MTAB-2211). Genomic loci bound by NtrC and RNAp were identified using the peak-calling algorithm SISSRs (Site Identification for Short Sequence Reads) 33, with peaks defined as significant with a P-value of<0.005 and if they showed greater than 9-fold enrichment in the immunoprecipitated sample compared to the input control.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA samples were extracted from cells at specified time-points, RNA was stabilized with Qiagen RNA protect reagent (Qiagen, U.S.A.) and extracted using the PureLink™ RNA Mini kit (Ambion Life Technologies, U.S.A.). Purified RNA was stored at −80°C in nuclease-free water. cDNA was amplified from 100 ng of RNA using the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, U.S.A.). qRT-PCR reactions were completed in a final volume of 10 μl (1 μl cDNA, 5 μl TaqMan Fast PCR master mix, 0.5 μl TaqMan probe (both Applied Biosystems, U.S.A.)). Amplification was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time machine using the following conditions; 50°C 5 min, 95°C 10 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C 15 sec, 60°C 1 min. Real-time analysis was performed in triplicate on RNA from three independent cultures and quantification of 16S expression served as an internal control. The relative expression ratios were calculated using the delta-delta method (PerkinElmer, U.S.A.). Statistical analysis of data was performed by one-way ANOVA, a P-value ≤0.01 was considered to be a significant difference. Primer and probe mixtures were custom designed from Applied Biosystems (Custom TaqMan gene expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, U.S.A.)) sequences can be viewed in Supplementary Table 2.

Microarray analysis of gene expression

Total RNA from E. coli cells sampled at t=N− and t=N+ were extracted as above and samples were processed by OGT (Oxford, UK) to incorporate Cy3 or Cy5 dyes and hybridized onto OGT 4×44K high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Gene expression data was collected by scanning the array using an Agilent Technologies microarray scanner and results were extracted by using Agilent Technologies image-analysis software with the local background correction option selected. Statistical analyses of the gene expression data was carried out using the statistical analysis software environment R together with packages available as part of the BioConductor project (http://www.bioconductor.org). Data generated from the Agilent Feature Extraction software for each sample was imported into R. Replicate probes were mean summarised and quantile normalised using the preprocess Core R package. The limma R package34 was used to compute empirical Bayes moderated t-statistics to identify differentially expressed gene between time points. Generated p-values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini and Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR). An FDR corrected P-value cut-off of less than 0.01 was used to determine significant differential expression. Differential gene expression results only for the 60 ppGpp responsive genes are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Proteins

Core RNA polymerase subunits α2ββ’ω (collectively known as E), σ54 and PspF1-275 were expressed and purified as described in detail previously 35. Briefly, core RNA polymerase was purified by nickel-affinity chromatography through the 6x-His-tagged β subunit following previous ammonium sulphate precipitation and heparin column purification of cell lysate. σ54 was purified by successive precipitation steps using streptomycin sulphate (2% final concentration) and ammonium sulphate (70% final concentration) followed by ion-exchange chromatography using a Sepharose column. Finally the sample was subjected to heparin column purification to separate σ54 from the core RNA polymerase. PspF1-275 was expressed as an N-terminally 6x-His-tagged protein from a pET28b+ based plasmid, and purified by nickel-affinity chromatography 35. 6x-His-tagged NtrC from ASKA(−) JW3839 36 was purified by nickel-affinity chromatography as follows. Briefly, cells were grown at 37°C in 80 ml LB medium supplemented with 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol to an OD600nm 0.3. Cultures were induced with 0.4 mM IPTG (final concentration) for a further 2 hours before samples were taken. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 4,500 × g for 30 minutes and the pellet was stored at −20°C. Thawed pellets were resuspended in Ni buffer A (25 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.0, 500 mM NaCl, and 5% (v/v) glycerol) containing a cocktail tablet of protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche Diagnostics, U.S.A.) and lysed using probe sonication. Soluble protein extract was recovered following centrifugation at 20,000 × g, this was loaded onto a pre-charged nickel column (GE Healthcare, U.K.) and purified via affinity chromatography using a AKTA prime FPLC (GE Healthcare, U.K.) as described for σ54 and PspF1-275 35. Pooled fractions containing 6x-His-tagged NtrC were dialysed against storage buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 50% (v/v) glycerol) at 4°C overnight. Aliquots were then stored at −80°C until required.

Small primed RNA synthesis assay

Small primed RNA (spRNA) synthesis assays were conducted as previously described 20. Briefly, assays were performed in STA buffer (25 mM Tris-acetate, pH 8.0, 8 mM Mg-acetate, 10 mM KCl, and 3.5% w/v PEG 6000) in a 10 μl reaction volume containing 50 nM Eσ54 (reconstituted using a 1:4 ratio of E:σ54) and 20 nM promoter DNA probe (relA probe sequence used as template DNA can be seen in Supplementary Table 3) which was initially incubated for 5 min at 37°C to form inactive Eσ54-DNA complexes. To this, NtrC (+/− phosphorylation with Carbamoyl phosphate) (final concentration 1 or 2 μM) or PspF1-275 (final concentration 1 μM) was added, for open complex formation dATP was added at 4 mM (final concentration), samples were incubated for a further 5 min at 37°C. Synthesis of spRNA (CpUpGpG) was initiated by the addition of a mix containing 0.5 mM CpU, 4 μCi [α-32P]GTP, 0.05 mM GTP and incubated for 60 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by addition of 4 μl loading dye (80% formamide, 10 mM EDTA, 0.04% bromophenol blue, and 0.04% xylene cyanol) and 3 min incubation at 95°C. Products were analyzed by PAGE on denaturing 20% TBE-urea gels, run at 200V for 40 min and visualized and quantified using a Typhoon FLA 7000 PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare, U.K.). All experiments were performed at least in triplicate.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were conducted in Reaction buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT) in a total-reaction volume of 10 μl containing 0, 50, 100, 250, 500 or 1000 nM NtrC and 10 mM Carbamyl phosphate, incubated for 30 min at 37°C prior to the addition of 5 nM 32P-labelled probe (sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 3), following which the reaction was incubated for a further 10 min at 37°C. Reactions were analyzed on 4.5% (w/v) native polyacrylamide gel. The gel was run for 60 min at 100 V at 37°C and then dried. NtrC-DNA probe complexes were visualized and quantified using a Typhoon FLA 7000 PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare, U.K.).

Transcription start site mapping by 5′RACE PCR

Transcription start site mapping was conducted using 5′ RACE System for Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends, Version 2.0 Kit (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, U.S.A.) as described in the manufacturer’s guidelines. For this, RNA was isolated from cells under nitrogen starvation (N−) as described above, sequences for primers used can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a LoLa grant (BB/G020434/1) from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) UK to M.B and S.W. S.W. is a recipient of a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award. We thank Sophie Hélaine, Brian Robertson and Rebecca Corrigan for discussions and comments on the manuscript. The authors would like to dedicate this article to the memory of Prof Sydney Kustu who was a pioneer in the field of bacterial nitrogen regulation.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at http://www.nature.com/naturecommunications.

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permission information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/

Accession codes: Data from the ChIP-seq experiments and from the microarray experiments have been deposited in the ArrayExpress database under accession codes E-MTAB-2211 and E-MTAB-XXXX, respectively.

References

- 1.Reitzer L. Nitrogen assimilation and global regulation in Escherichia coli. Annual review of microbiology. 2003;57:155–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090820. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmer DP, et al. Nitrogen regulatory protein C-controlled genes of Escherichia coli: scavenging as a defense against nitrogen limitation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:14674–14679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14674. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.26.14674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang P, Ninfa AJ. Regulation of autophosphorylation of Escherichia coli nitrogen regulator II by the PII signal transduction protein. Journal of bacteriology. 1999;181:1906–1911. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.6.1906-1911.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villadsen IS, Michelsen O. Regulation of PRPP and nucleoside tri and tetraphosphate pools in Escherichia coli under conditions of nitrogen starvation. Journal of bacteriology. 1977;130:136–143. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.1.136-143.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkinson GC, Tenson T, Hauryliuk V. The RelA/SpoT homolog (RSH) superfamily: distribution and functional evolution of ppGpp synthetases and hydrolases across the tree of life. PloS one. 2011;6:e23479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023479. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerdes K, Maisonneuve E. Bacterial persistence and toxin-antitoxin loci. Annual review of microbiology. 2012;66:103–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150159. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bokinsky G, et al. HipA-triggered growth arrest and beta-lactam tolerance in Escherichia coli are mediated by RelA-dependent ppGpp synthesis. Journal of bacteriology. 2013;195:3173–3182. doi: 10.1128/JB.02210-12. doi:10.1128/JB.02210-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potrykus K, Cashel M. (p)ppGpp: still magical? Annual review of microbiology. 2008;62:35–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162903. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalebroux ZD, Swanson MS. ppGpp: magic beyond RNA polymerase. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2012;10:203–212. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2720. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shyp V, et al. Positive allosteric feedback regulation of the stringent response enzyme RelA by its product. EMBO reports. 2012;13:835–839. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.106. doi:10.1038/embor.2012.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.English BP, et al. Single-molecule investigations of the stringent response machinery in living bacterial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:E365–373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102255108. doi:10.1073/pnas.1102255108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wendrich TM, Blaha G, Wilson DN, Marahiel MA, Nierhaus KH. Dissection of the mechanism for the stringent factor RelA. Molecular cell. 2002;10:779–788. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00656-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang M, Sullivan SM, Wout PK, Maddock JR. G-protein control of the ribosome-associated stress response protein SpoT. Journal of bacteriology. 2007;189:6140–6147. doi: 10.1128/JB.00315-07. doi:10.1128/JB.00315-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell EA, et al. Structural mechanism for rifampicin inhibition of bacterial RNA polymerase. Cell. 2001;104:901–912. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herring CD, et al. Immobilization of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase and location of binding sites by use of chromatin immunoprecipitation and microarrays. Journal of bacteriology. 2005;187:6166–6174. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.17.6166-6174.2005. doi:10.1128/JB.187.17.6166-6174.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rombel I, North A, Hwang I, Wyman C, Kustu S. The bacterial enhancer-binding protein NtrC as a molecular machine. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology. 1998;63:157–166. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bush M, Dixon R. The role of bacterial enhancer binding proteins as specialized activators of sigma54-dependent transcription. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews : MMBR. 2012;76:497–529. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00006-12. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00006-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakagawa A, Oshima T, Mori H. Identification and characterization of a second, inducible promoter of relA in Escherichia coli. Genes & genetic systems. 2006;81:299–310. doi: 10.1266/ggs.81.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrios H, Valderrama B, Morett E. Compilation and analysis of sigma(54)- dependent promoter sequences. Nucleic acids research. 1999;27:4305–4313. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burrows PC, Joly N, Buck M. A prehydrolysis state of an AAA+ ATPase supports transcription activation of an enhancer-dependent RNA polymerase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:9376–9381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001188107. doi:10.1073/pnas.1001188107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magnusson LU, Farewell A, Nystrom T. ppGpp: a global regulator in Escherichia coli. Trends in microbiology. 2005;13:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.03.008. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross W, Vrentas CE, Sanchez-Vazquez P, Gaal T, Gourse RL. The magic spot: a ppGpp binding site on E. coli RNA polymerase responsible for regulation of transcription initiation. Molecular cell. 2013;50:420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.021. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keseler IM, et al. EcoCyc: fusing model organism databases with systems biology. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41:D605–612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1027. doi:10.1093/nar/gks1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burrows PC, Wiesler SC, Pan Z, Buck M, Wigneshweraraj S. In: Bacterial Regulatory Networks. Filloux AAM, editor. Caister Academic Press; 2012. pp. 27–58. Ch. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reitzer L, Schneider BL. Metabolic Context and Possible Physiological Themes of σ54-Dependent Genes in Escherichia coli. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2001;65:422–444. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.3.422-444.2001. doi:10.1128/MMBR.65.3.422-444.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bender RA. A NAC for Regulating Metabolism: the Nitrogen Assimilation Control Protein (NAC) from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Journal of bacteriology. 2010;192:4801–4811. doi: 10.1128/JB.00266-10. doi:10.1128/JB.00266-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schumacher J, et al. Nitrogen and carbon status are integrated at the transcriptional level by the nitrogen regulator NtrC in vivo. mBio. 2013;4:e00881–00813. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00881-13. doi:10.1128/mBio.00881-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baba T, et al. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Molecular Systems Biology. 2006;2:2006.0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. doi:10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang B, Kitney RI, Joly N, Buck M. Engineering modular and orthogonal genetic logic gates for robust digital-like synthetic biology. Nature communications. 2011;2:508. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1516. doi:10.1038/ncomms1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atlas RM. Handbook of microbiological media. Fourth edition Vol. 1. CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biology. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. doi:10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2013;14:178–192. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. doi:10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Narlikar L, Jothi R. ChIP-Seq data analysis: identification of protein-DNA binding sites with SISSRs peak-finder. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2012;802:305–322. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-400-1_20. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-400-1_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Statistical applications in genetics and molecular biology. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article3, doi:10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wigneshweraraj SR, et al. Enhancer-dependent transcription by bacterial RNA polymerase: the beta subunit downstream lobe is used by sigma 54 during open promoter complex formation. Methods in enzymology. 2003;370:646–657. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)70053-6. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(03)70053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitagawa M, et al. Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (a complete set of E. coli K-12 ORF archive): unique resources for biological research. DNA research : an international journal for rapid publication of reports on genes and genomes. 2005;12:291–299. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsi012. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Claverie-Martin F, Magasanik B. Role of integration host factor in the regulation of the glnHp2 promoter of Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88:1631–1635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiupakis AK, Reitzer L. ArgR-Independent Induction and ArgR-Dependent Superinduction of the astCADBE Operon in Escherichia coli. Journal of bacteriology. 2002;184:2940–2950. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.2940-2950.2002. doi:10.1128/JB.184.11.2940-2950.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ninfa AJ, Reitzer LJ, Magasanik B. Initiation of transcription at the bacterial glnAp2 promoter by purified E. coli components is facilitated by enhancers. Cell. 1987;50:1039–1046. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reitzer LJ, Magasanik B. Transcription of glnA in E. coli is stimulated by activator bound to sites far from the promoter. Cell. 1986;45:785–792. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90553-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ueno-Nishio S, Mango S, Reitzer LJ, Magasanik B. Identification and regulation of the glnL operator-promoter of the complex glnALG operon of Escherichia coli. Journal of bacteriology. 1984 doi: 10.1128/jb.160.1.379-384.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.