Abstract

Mutations in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle enzyme fumarate hydratase (FH) are associated with a highly malignant form of renal cancer. We combined analytical chemistry and metabolic computational modelling to investigate the metabolic implications of FH loss in immortalised and primary mouse kidney cells. Here, we show that the accumulation of fumarate caused by the inactivation of FH leads to oxidative stress that is mediated by the formation of succinicGSH, a covalent adduct between fumarate and glutathione. Chronic succination of GSH, caused by the loss of FH, or by exogenous fumarate, leads to persistent oxidative stress and cellular senescence in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, the ablation of p21, a key mediator of senescence, in Fh1-deficient mice resulted in the transformation of benign renal cysts into a hyperplastic lesion, suggesting that fumarate-induced senescence needs to be bypassed for the initiation of renal cancers.

Introduction

FH mediates the reversible conversion of fumarate to malate in the TCA cycle. The biallelic inactivation of FH leads to Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer (HLRCC), a hereditary cancer syndrome characterized by the presence of benign tumours of the skin and uterus and a highly malignant form of renal cell cancer1. Fumarate, which is highly accumulated in FH-deficient cells, has long been considered a major pro-oncogenic factor for HLRCC tumorigenesis2. It was initially proposed that the stabilization of the Hypoxia Inducible Factors (HIFs), caused by the fumarate-dependent inhibition of prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs), was instrumental for tumour formation3,4. However, the recent findings that the genetic deletion of HIFs does not prevent cyst formation in Fh1-deficient mice5 challenged their etiological role in these tumours, indicating that other HIF-independent oncogenic pathways are involved.

Fumarate is a moderately reactive α,β-unsaturated electrophilic metabolite that can covalently binds to cysteine residues of proteins under physiological conditions. This process, called protein succination, is a feature of FH-deficient tumour tissues, where fumarate accumulates to millimolar levels6. Keap1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase and an inhibitor of the transcription factor Nuclear erythroid Related Factor 2 (NRF2), has recently been identified as a target of protein succination and consequent inactivation, which led to the induction of NRF2 and a potent antioxidant response5,7. Of note, among the most characterised targets of NRF2, Haem Oxygenase 1 (HMOX1) has been found to be synthetic lethal with FH8 suggesting that the activation of NRF2 and its downstream targets might have an important pro-survival role in Fh1-deficient cancer cells, beyond the control of redox homeostasis.

Although Keap1 succination could explain the antioxidant transcriptional signature in FH-deficient tissues, other direct oxidation mechanisms could contribute to such a response. In fact, the loss of FH has been previously associated with the increased production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)9, and the accumulation of fumarate in FH-deficient cancer cell lines leads to the formation of an adduct between fumarate and GSH, which depletes intracellular NADPH and enhances oxidative stress10. Nevertheless, a comprehensive investigation of the mechanism by which FH loss triggers oxidative stress, and the biological consequences of such stress, have not been performed.

Systems biology has become an invaluable tool for investigating cellular metabolism as it allows integrating data from different platforms such as transcriptomics and metabolomics. This approach was recently used to identify the molecular determinants of the Warburg effect11 and to explore novel therapeutic strategies for cancer such as metabolic synthetic lethality12. In the present work we used a combination of computational biology, metabolomics, and mouse genetics to investigate the overall metabolic effects of FH loss and, in particular, the possible outcomes of FH loss and oxidative stress. We demonstrated that the accumulated fumarate leads to oxidative stress by covalently binding to reduced glutathione (GSH) in a non-enzymatic reaction that forms succinicGSH. We also demonstrated that the oxidative stress induced by GSH succination is necessary and sufficient to elicit cellular senescence in non-transformed cells and that the ablation of senescence can initiate a tumorigenic programme in the kidneys of Fh1-deficient mice.

Results

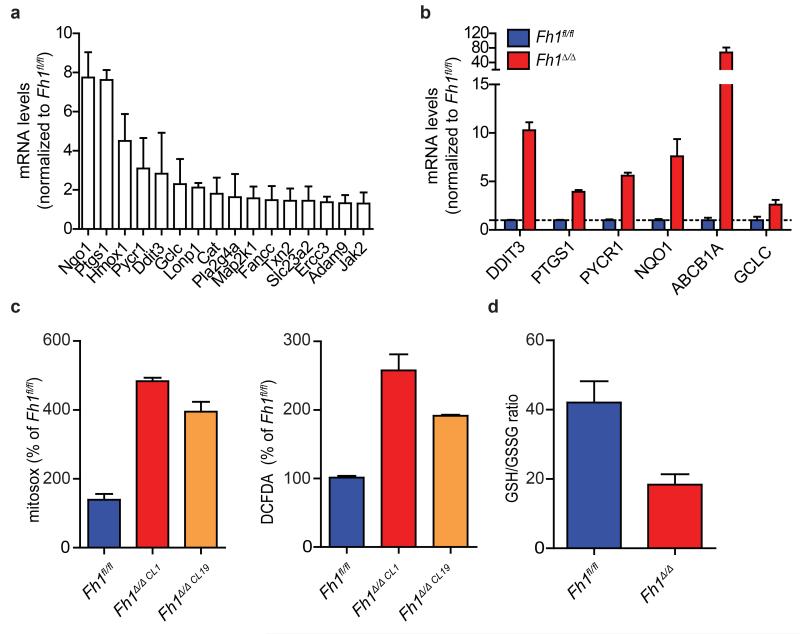

Oxidative stress in FH-deficient cells

To elucidate the metabolic changes that occur upon the loss of FH we utilised the previously characterised mouse FH-deficient kidney cells (Fh1Δ/Δ) and their wild type (wt) isogenic control (Fh1fl/fl)8. Initially, we found that genes whose expression is up-regulated in FH-deficient cells8 are significantly enriched with oxidative stress genes (hypergeometric p-value of 5.505e-04, see Methods). Reassuringly, genes that are up-regulated in HLRCC clinical samples relative to normal kidney tissues7 are also significantly enriched with oxidative stress genes (hypergeometric p-value of 3.984e-06). The genes that featured most highly (Fig. 1a) were then validated by qPCR (Fig. 1b). In line with this oxidative stress signature Fh1-deficient cells exhibit increased ROS production and a substantial drop in GSH/GSSG ratio (Fig. 1c-d).

Figure 1. Antioxidant signature in FH-deficient cells.

(a-b) expression of genes that belong to “antioxidant response” retrieved from a gene expression array (a) and validated by qPCR (b) from FH-deficient mouse kidney epithelial, as compared to control cells. qPCR data were obtained from 3 independent cultures and represented as average ± s.e.m. (c-d) FH-deficient cells exhibit increased oxidative stress measured by mitosox (c), DCFDA (c) and by decreased GSH/GSSG ratio (d). Results were obtained from 3 independent experiments and represented as average ± s.e.m.

To better understand the metabolic consequences of FH loss we performed a comprehensive analysis of extracellular metabolite exchange rates using liquid chromatography – mass spectrometry (LC-MS) (Supplementary Table 1). We then generated in silico genome-scale metabolic models of the FH-deficient and wt cells by incorporating the gene expression and metabolite exchange rates measured in these cell lines within a generic metabolic model13 (see Methods). Of note, these implemented models not only explore essential reactions for biomass production, as previously done8, but also allowed us to predict changes in metabolic fluxes upon loss of FH. We first examined the models by testing their ability to predict the measured flux rates via cross-validation (leaving one out). For each iteration, we regenerated a new model based on the gene expression and a partial set of the metabolite uptake and secretion rates and used these models to predict the flux-rate through the reaction whose flux measurement was omitted. Significant correlation was found between the measured and predicted flux rates (R=0.617, and 0.551, p-values of 6.59e-04, and 2.63e-03, when testing the wt and FH-deficient models, respectively; Supplementary Table 2).

Following the validation of the models, we utilized them to systematically explore the metabolic differences between the FH-deficient and control cells. We computed the capacity of the two models to produce each of the 1,491 metabolites included in the models. The FH-deficient model was found to have a higher capacity to produce 43 metabolites. Among the top ones are four derivatives of glutathione (Supplementary Fig. 1a-b). Furthermore, glutathione biosynthesis was projected to be an essential metabolic reaction in the Fh1-deficient model (Supplementary Fig. 3b). We also predicted that the FH-deficient model has a significantly lower capacity to produce reducing power, in the form of NADH and NADPH, compared to the wt model (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Of note, in the computational model, the loss of HMOX1, whose essentiality in the Fh1-deficient cells has been previously shown8, was expected to exacerbate the decreased ability of the FH-deficient cells to produce NADPH.

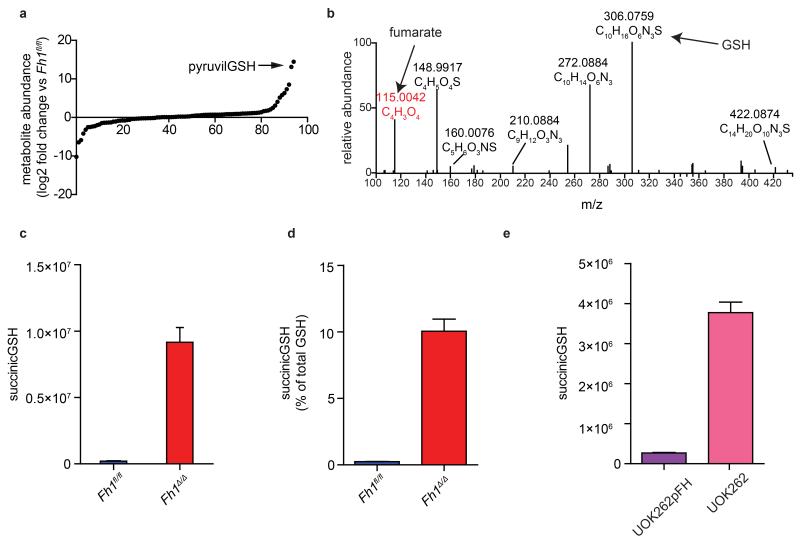

Metabolomics revealed GSH succination in FH-deficient cells

In order to further confirm that GSH metabolism was altered in FH-deficient cells an LC-MS analysis of steady state intracellular metabolites was performed. Among the most significant metabolites accumulated in FH-deficient cells a putative GSH adduct was detected (annotated by Metlin database as the formate adduct of pyruvilGSH) (Fig. 2a). Since this metabolite is specific to FH deficient cells and is poorly characterised we decided to elucidate its structure by LC-MS/MS and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) analyses. The MS/MS fragmentation pattern and the presence of fumarate and GSH fragments as diagnostic daughter ions (Fig. 2b), strongly indicated that this metabolite was wrongly annotated and is instead an adduct of fumarate binding to GSH, which we defined as succinicGSH (Supplementary Fig. 2a for the chemical structure). Furthermore, NMR pulse field gradient correlation spectroscopy (pfgCOSY), pulse field gradient total correlation spectroscopy (pfgTOCSY) (Supplementary Fig. 2b) and further LC-MS/MS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2c) confirmed the chemical structure of this molecule (registered as S-(1,2-Dicarboxyethyl)glutathione: CAS Registry Number [1115-52-2]).

Figure 2. Accumulation of fumarate leads to GSH succination.

(a) Relative abundance of intracellular metabolites in FH-deficient cells measured by LC-MS. Results were obtained from 9 independent cultures. (b) Fragmentation pattern of the metabolite annotated as pyruvilGSH obtained by LC-MS/MS. (c-e) Intracellular abundance of succinicGSH in mouse (c) and human (e) FH-deficient cells. (d) Amount of succinicGSH compared to the pool of GSH in mouse cells. succinicGSH and GSH were measured by LC-MS. Results were obtained from 3 independent experiments and represented as average ± s.e.m.

After elucidating the molecular structure of succinicGSH we confirmed its presence in Fh1Δ/Δ cells using targeted LC-MS, showing that succinicGSH represents about 10% of the total GSH in these cells (Fig. 2c and 2d). It is noteworthy that succinicGSH was also recently characterised in the human FH-deficient renal cancer cell line UOK26210 and we confirmed its presence in these cells (Fig. 2e).

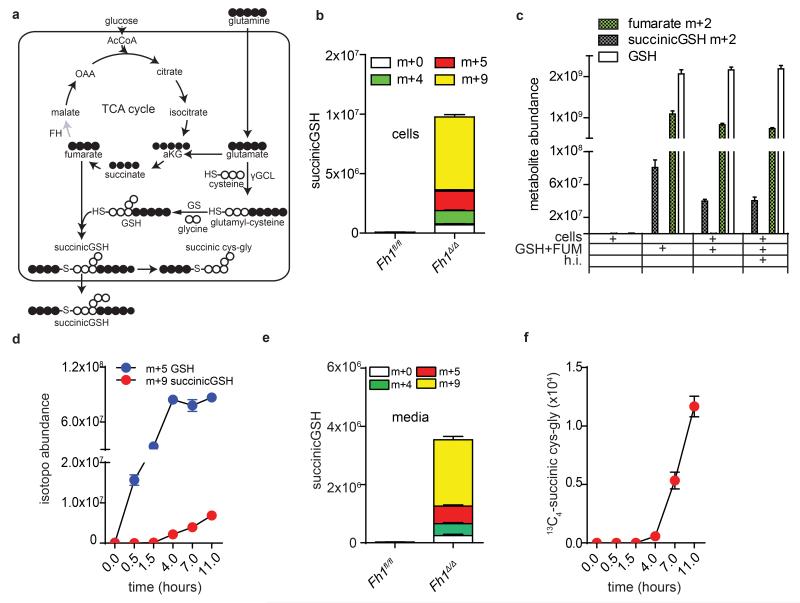

SuccinicGSH is formed by a reaction between fumarate and GSH

To further elaborate on the source of succinicGSH in FH-deficient cells, we tested the hypothesis that this compound is formed by a reaction between accumulated fumarate and GSH. To this end, FH-deficient cells were incubated with uniformly-labelled 13C5-glutamine, which generates 13C5-labelled glutamate and 13C4-labelled fumarate, and the isotopologue distribution of succinicGSH was analysed by LC-MS (see Fig. 3a for a schematic diagram of the reactions). SuccinicGSH isotopologues were consistent with carbons coming mostly from fumarate (m+4) and glutamate (m+5), which eventually gave rise to a m+9 labelled metabolite (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. The formation and fate of SuccinicGSH.

(a) Schematic representation of GSH biosynthesis in FH-deficient cells upon incubation with 13C5-glutamine. The white and black circles under each metabolite illustrate 12C- and 13C-, respectively. (b) Isotopologue distribution of succinicGSH were measured by LC-MS after incubating cells of the indicated genotype in the presence of 13C5-glutamine for 8 hours. (c) GSH and 13C2-fumarate were mixed in a physiological buffer in the presence or absence of protein lysates from FH-deficient cells and the amount of 13C2-succinicGSH was measured by LC-MS. Where indicated, the cell extracts were heat inactivated (h.i.) prior to the in vitro reaction. (d) The kinetics of GSH and SuccinicGSH formation from 13C5-Glutamine. (e) The relative level of succinicGSH in the media of mouse cells with the indicated genotype. (f) The kinetics of the formation of the degradation product from GSH was traced by 13C5-Glutamine and assessed by LC-MS. Results were obtained from 3 independent experiments and represented as average ± s.e.m.

At physiological pH the thiol residue of GSH is scarcely deprotonated (pKa=9.2). Therefore, reactions between GSH and electrophilic molecules are generally catalysed by enzymes, such as Glutathione Transferases, which activate GSH by ionising its thiol group (SH) into the more reactive thiolate (S−) residue14. We therefore wanted to address whether the production of succinicGSH required an enzymatic reaction. To this end, GSH and fumarate, at a concentration found in Fh1-deficient cells15, were mixed in a physiological buffer. In order to avoid interference from endogenous fumarate and succinicGSH from cell extracts, 13C2-fumarate was used. When labelled fumarate and GSH were mixed in a physiological buffer a significant amount of m+2 labelled succinicGSH was detected (Fig. 3c). The addition of cell protein extracts from Fh1-deficient cells did not increase and, heat inactivation did not decrease the production of succinicGSH, indicating that the formation of the compound under these conditions is non-enzymatic. Together, these results demonstrated that fumarate, when accumulated, leads to GSH succination.

We further investigated the rate of succinicGSH formation and its degradation. To this aim, Fh1-deficient cells were incubated with 13C5-glutamine and the kinetics of succinicGSH formation was monitored. The labelling of succinicGSH occurred very rapidly upon incubation with labelled glutamine and it tailed GSH biosynthesis (Fig. 3d). Of note, we could not detect the succinated form of the GSH precursor γ-glutamyl-cysteine in Fh1-deficient cells, suggesting that GSH, rather than one of its precursors, is subject to succination. We finally investigated the fate of succinicGSH. Experiments on Fh1-deficient cells incubated with 13C5-glutamine revealed that succinicGSH is excreted in the media (Fig. 3e) and its isotopologue labelling matches that of intracellular succinicGSH (Fig. 3b). Importantly, in these cells we have also identified a succinated form of the dipeptide cys-gly, the degradation product of GSH. The rate of production of this metabolite, which followed both GSH and succinicGSH kinetics (Fig. 3f), suggests that succinic cys-gly is likely a breakdown product of succinicGSH. Together, this investigation revealed that succinicGSH is formed by succination of newly synthesised GSH and that this metabolite is partly degraded into succinated cys-gly and partly secreted to the media (See Fig. 3a for a schematic of these reactions).

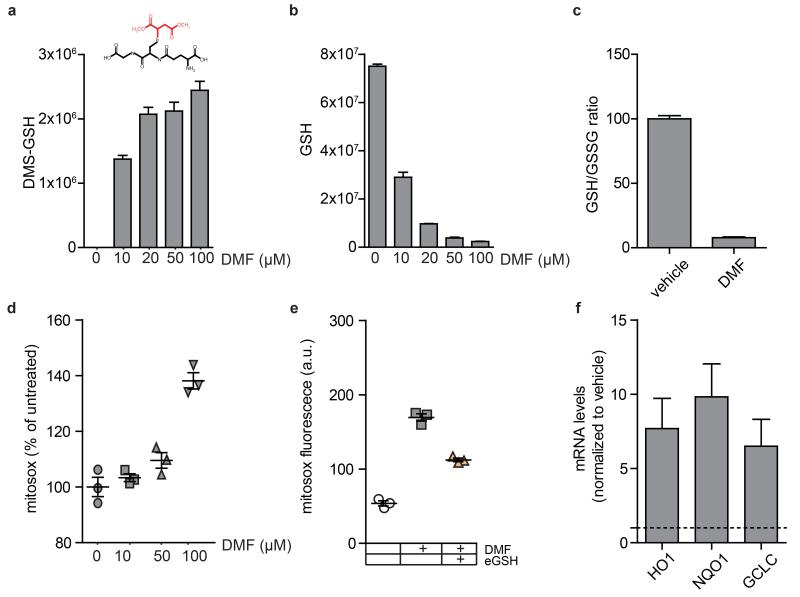

Succination of GSH increases oxidative stress

We wanted to investigate the link between GSH succination and the oxidative stress signature that characterise FH-deficient cells (Fig. 1). Sullivan et al. previously proposed that enhanced oxidative stress in these cells is caused by the NADPH-depleting conversion of succinicGSH into GSH, a reaction catalysed by glutathione reductase (GR)10. However, this conclusion was based on indirect evidence i.e. consumption of NADPH upon incubation of a methylated version of succinicGSH at high concentration and GR10. To test their hypothesis, we measured the activity of GR towards chemically synthesized succinicGSH as compared to its natural substrate oxidized GSH (GSSG) by measuring the products. While GSSG was quickly reduced to GSH, we could not detect GSH production from succinicGSH in the presence of GR (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Therefore, it is unlikely that the detoxification of succinicGSH by GR provides explanation for the enhanced redox stress in Fh1- deficient cells. Several other factors could contribute to the oxidative stress in these cells, including electron transport chain dysfunction, as previously documented16. Therefore, to investigate the mechanistic link between fumarate accumulation, succination of GSH, and oxidative stress, respiration-competent Fh1fl/fl cells were incubated with a cell permeable derivative of fumarate, dimethylfumarate (DMF). DMF quickly reacted with intracellular GSH leading to the formation of dimethyl-succinicGSH (DMS-GSH) (Fig. 4a). Of note, the incubation with DMF caused a dose-dependent depletion of GSH (Fig. 4b), a substantial drop in the GSH/GSSG ratio (Fig. 4c) and increased oxidative stress (Fig. 4d-e). Furthermore, DMF treatment elicited an antioxidant gene response similar to that observed in Fh1Δ/Δ cells (Fig. 4f). Importantly, the incubation with a cell-permeable derivative of GSH, ethyl-GSH (eGSH), significantly decreased the ROS production triggered by DMF (Fig. 4e). Together, these results indicate that the succination of GSH, but not its detoxification, is responsible for the oxidative stress observed in Fh1-deficient cells

Figure 4. Dimethyl-fumarate induces GSH succination and increases oxidative stress.

(a-c) Cell-permeable dimethyl-fumarate (DMF) binds to (a) and depletes (b) the intracellular pool of GSH, leading to a decrease in GSH/GSSG ratio (c). The structure of the adduct between GSH and DMF, DMS-GSH, is indicated in panel (a). (d-f) DMF induces oxidative stress (d-e) and the activation of an antioxidant response, measured by the expression of antioxidant genes (f). The redox stress caused by DMF is attenuated by incubating cells with a cell permeable derivative of GSH, eGSH (e). HO1 = heme oxygenase1; NQO1 = NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (quinone 1); GCLC = glutamate-cysteine ligase. Results were obtained from 3 independent experiments and represented as average ± s.e.m.

GSH succination increases glutathione biosynthesis

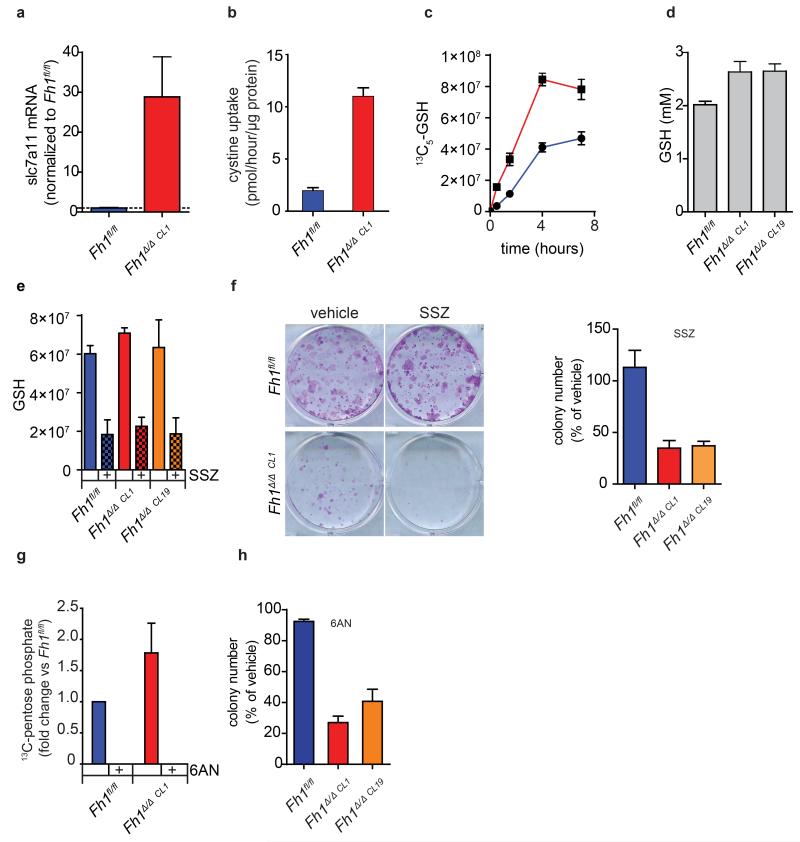

We hypothesised that the chronic depletion of GSH caused by succination could perturb cell metabolism and contribute to a general deregulation of redox homeostasis. To address this question, we reconstructed the metabolic models previously generated to include GSH-succination. Of note, the inclusion of this reaction improved the ability of the FH-deficient model to predict the measured flux rates (R=0.570, p=1.81E-03) (Supplementary Table 2). We found that in the FH-deficient model, but not in the wt model, GSH succination significantly reshaped the generation of reducing power (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Furthermore, the model revealed that GSH succination impinged GSH metabolism and cystine uptake (Supplementary Table 3). Notably, the selective uptake of cystine (an oxidized dimer of cysteine), rather than methionine, as a precursor for cysteine and subsequently GSH biosynthesis imposes a further metabolic constraint: the reduction of cystine to cysteine requires NADPH, the supply of which becomes critical for GSH biosynthesis (see Supplementary Fig. 3b). In line with these predictions, Fh1Δ/Δ cells exhibited a significant overexpression of Slc7a11, a member of the cystine transporter xCT, which was functionally associated with increased uptake of cystine (Fig. 5a-b). The rate limiting step in GSH biosynthesis is the synthesis of γ-glutamylcysteine from glutamate and cysteine by γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (GCL) (see Fig. 3a for a schematic representation of these reactions). GSH is then synthesised by glutathione synthetase (GSS), which adds glycine to gamma-glutamylcysteine. Therefore, the GSH biosynthesis rate could be assessed by the rate of incorporation of glutamine-derived glutamate after incubation with 13C5-glutamine. The incorporation of glutamate into GSH was faster in FH-deficient cells, meaning that, as predicted by the computational models, GSH production is accelerated in FH-deficient cells (Fig. 5c). Moreover, the increased biosynthesis rate of GSH caused by GSH succination led to a larger steady-state pool of GSH (Fig. 5d). In line with these findings, genes encoding for cystine transport (Slc7a11) and enzymes of the GSH biosynthetic pathway (GSS and GCL), are significantly upregulated in HLRCC patients (Supplementary Fig.4)7,17. All in all, these suggest that increased GSH biosynthesis could be a compensatory mechanism that mitigates the increased oxidative stress in FH-deficient cells.

Figure 5. GSH succination triggers cystine uptake and GSH biosynthesis.

(a-c) The loss of FH leads to the upregulation of the cystine transporter (a), increased cystine uptake (b) and accelerated GSH biosynthesis traced from 13C5-glutamine (c). (d) The steady-state pool of GSH is increased in FH-deficient cells. (e-f) Sulfasalazin (SSZ) inhibits GSH biosynthesis in both wt and FH-deficient cells (e) but selectively impairs cell survival and growth of FH-deficient cells (f). (g-h) 6-aminonicotinamide (6-AN), an inhibitor of the pentose phosphate pathways, inhibits pentose phosphate production in both cell lines as assessed by tracing 13C6-Glucose (g), selectively affects the proliferation of FH-deficient cells (h). The images in (f) are representative images of triplicate cultures. Results were obtained from 3 independent experiments and represented as average ± s.e.m.

To test whether GSH biosynthesis is required for the survival of FH-deficient cells, we inhibited cystine uptake using a well characterised xCT inhibitor, sulfasalazine. Reassuringly, the inhibition of cystine uptake significantly impaired GSH biosynthesis in both genotypes (Fig. 5e). However, only Fh1Δ/Δcells were negatively affected by the drug (Fig. 5f). Since GSH biosynthesis requires NADPH supply to reduce cystine to cysteine (Supplementary Fig. 3b), we tested the effects of inhibiting NAPDH production on the survival of FH-deficient cells. The Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) is the major supply of NADPH in cells and so cells were incubated with 6-amino nicotinamide (6AN), a known inhibitor of the PPP enzyme 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6-PGDH). 6AN effectively halted PPP activity in both genotypes (Fig. 5g) but it only affected the survival of FH-deficient cells (Fig. 5h). In summary, these results indicate that GSH biosynthesis is essential for FH-deficient cells to overcome the oxidative stress caused by GSH succination.

Loss of FH leads to oxidative-stress mediated senescence

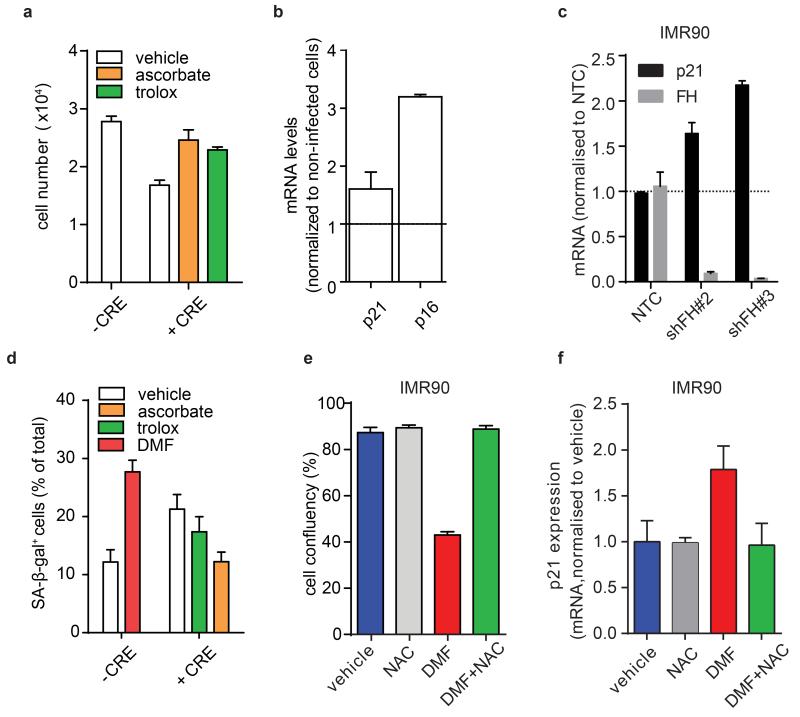

We hypothesised that the observed metabolic reprogramming is a required step for the support of cell transformation. Since both the human and mouse FH-deficient cells used here were immortalised cell lines, we tested the effects of GSH succination on primary kidney cells isolated from Fh1fl/fl mouse pups and on the human diploid fibroblasts IMR90. Upon infection with adenoviral vector expressing Cre recombinase (Ad-Cre), Fh1fl/fl cells, which lost FH activity, underwent proliferation arrest, whereas the uninfected cells continued to proliferate (Fig. 6a). The proliferation arrest was associated with a robust induction of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21CIP1/WAF1 (thereafter referred to as p21) and of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A p16 (Fig. 6b). These results suggested that oxidative stress-mediated cellular senescence18 might be responsible for the observed phenotype. Similarly, the non-transformed non-immortalised human diploid fibroblast cells IMR90 exhibited a significant upregulation of p21 upon acute depletion of FH (Fig. 6c). To confirm the involvement of senescence, we tested the senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity in FH-deficient cells. Upon infection with Ad-Cre, Fh1fl/fl exhibited a strong SA-β-gal staining (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 5a). Reassuringly, the loss of FH was also associated with the activation of an antioxidant response similar to that observed in Fh1-deficient cell lines (Supplementary Fig 5b). To ascertain the role of oxidative stress in senescence induction, cells were incubated with ascorbate (vitamin C) or Trolox (vitamin E derivative), two well-characterised antioxidants, which are water or lipid soluble respectively. Importantly, both the growth inhibitory effect, and the induction of SA-β-gal activity in Fh1-deficient primary kidney cells were abrogated by these antioxidants (Fig. 6a and d). These results indicate that redox stress induced by FH loss is, at least in part, responsible for the ensuing senescence.

Figure 6. GSH succination leads to redox stress-induced senescence in primary kidney cells and human diploid fibroblasts.

(a) 1×104 primary epithelial kidney cells from Fh1fl/fl animals were either left uninfected, or infected with adeno-CRE and treated with vehicle or the antioxidant Trolox or Ascorbate. Cell number was measured after 2 days of culture. (b) The ablation of FH in cells described in (a) resulted in the activation of p16 and p21 transcription. Results are expressed as average fold induction over non-infected cells ± s.e.m (representative experiments; n=6 for p21 and n=3 for p16). (c) FH and p21 mRNA levels were assessed by qPCR in non-targeting control (NTC) transfected cells in FH-silenced cells. (d) Microscopy quantitative analysis of senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity, induced by DMF or adeno-CRE infection, with or without Trolox and Ascorbate. (e-f) cell growth (e) and p21 mRNA expression levels (f) were assessed in IMR90 cells after DMF treatment, with or without the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC). All the results were obtained from 3 independent cultures and expressed as average ± s.e.m.

We then wanted to test the direct role of GSH succination in fumarate-induced senescence. Primary kidney cells and IMR90 cells were treated with DMF, a potent inducer of succination-dependent oxidative stress and their proliferation was assessed. DMF elicited a dose-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation and induced SA-β-gal activity in non-transformed primary mouse kidney epithelial cells (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 5a and 5c). Consistent with these results, DMF-treated IMR90 exhibited profound proliferation defects (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Fig. 5d), p21 upregulation (Fig. 6f), and SA-β-gal positivity (Supplementary Fig. 5d), which were rescued by the incubation with the antioxidant N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC) (Fig. 6e-f and Supplementary Fig. 5d-e). These results strongly suggest that fumarate-induced oxidative stress is sufficient for the induction of p21 and the initiation of cell senescence, regardless of cells’ genotype.

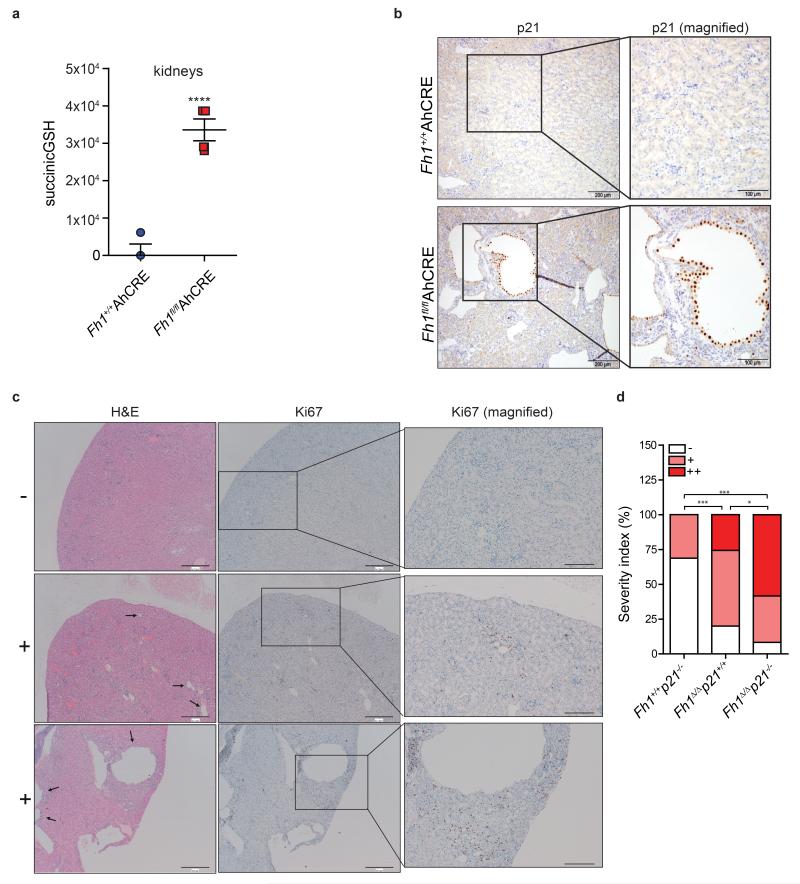

Fumarate-induced senescence in renal cysts of Fh1Δ/Δ mice

Previous work demonstrated that the loss of FH in murine kidneys does not result in overt renal carcinomas, as observed in HLRCC patients, but rather in benign cysts19. Our results indicated that the redox stress mediated by the accumulation of fumarate caused by the loss of Fh1 leads to senescence. Therefore, we hypothesised that senescence could be a major adjournment event of the tumorigenic process in Fh1-deficient animals. To test this hypothesis we used the previously characterised Fh1fl/flAhCre mice, which develop FH-deficient renal cysts15. Metabolite extraction confirmed the presence of high levels of succinicGSH in the kidneys of these animals (Fig. 7a). In line with our findings in FH-deficient cell lines, many of the epithelial cells facing the lumen of the renal cysts showed an intense staining for p21 (Fig. 7b). To address the role of p21 in suppression of tumorigenesis in Fh1-null mice, we crossed Fh1fl/flAhCre with p21−/− mice, obtaining animals deficient for both Fh1 and p21 in the kidneys (Fh1Δ/Δp21−/−). Histological analyses revealed that a simultaneous ablation of these genes resulted in the presence of several hyperproliferative areas in the kidneys. This was assessed by haematoxylin and eosin staining for cellular density and by Ki67 for proliferative capacity of the cells20. Strikingly, several areas of the kidneys of Fh1Δ/Δp21−/− animals were characterized by strong Ki67 staining (Fig. 7c ++; quantified in Fig.7d). In fact, 14 out of 24 (58.33 %) of the Fh1Δ/Δp21−/−animals exhibited dense areas with proliferative and locally-invasive kidney epithelial cells (cytokeratin positive) (Fig. 7c ++ and Supplementary Fig. 6). These results strongly suggest that the bypass of senescence may initiate a tumorigenic programme in Fh1-deficient mice.

Figure 7. GSH succination is associated with fumarate-induced senescence in renal cysts.

(a) SuccinicGSH was measured in kidney extracts of the indicated animals by LC-MS. Four animals for each genotype were used for this experiment. (b) Representative images of p21 immunostaining performed on dissected kidneys of the indicated mice. (c) Representative H&E staining and Ki67 immunostaining images of the different histological grading of kidney hyperplasia observed in 12-18 month-old mice. Representative images from normal kidneys, scored as (−), were taken from Fh1+/+ p21−/− animals; kidneys with limited number of cysts (arrows) and areas of hyperplasia with low overall Ki67, staining scored as (+), were taken from Fh1Δ/Δ p21+/+ animals; polycystic kidneys with increased Ki67 immunostaining mainly localized around large cystic areas (arrows), scored as (++), were taken from Fh1Δ/Δ p21−/−. Scale bars represent 500 μm and 200 μm respectively. (d) Quantitative analysis of the % distribution of the different hyperplastic grades described in (c) in the indicated genotypes. The results are derived from n=32 of Fh1+/+ p21−/−, n=35 of Fh1Δ/Δ p21+/+ and n=24 of Fh1Δ/Δ p21−/− mice aged 12-18 months. P values calculated by Chi Square analysis are indicated (*** p<0.0001, *p<0.05).

Discussion

FH is emerging as an important mitochondrial tumour suppressor in both hereditary and sporadic forms of cancer2. Although FH mutations in HLRCC were discovered more than a decade ago, the specific consequences of the loss of this TCA cycle enzyme remained unclear. The biochemical consequences of Fh1 inactivation in both human and mouse cells have been extensively investigated, revealing a complex pattern of metabolic defects, including deregulation of TCA and urea cycle15. Nevertheless, a global analysis of the metabolic rewiring upon the loss of Fh1 is still missing. To address this question, we generated in silico models to explore the metabolic consequences of FH inactivation. These models, which integrate transcriptomics and consumption-release metabolomics data to predict metabolic fluxes, revealed unexpected metabolic features of FH-deficient cells. Interestingly, we found that a large number of metabolic pathways became essential upon the loss of FH, among which haem biosynthesis and degradation pathway and GSH biosynthesis were the most enriched. While the haem biosynthesis and degradation pathway has already been demonstrated to be synthetic lethal in FH-deficient cells, the role of GSH metabolism in FH-deficient cells has not been investigated before and required further investigation. An untargeted intracellular metabolomics analysis helped to shed light on these findings. We found that the aberrant accumulation of fumarate leads to the persistent depletion of GSH via the formation of the adduct succinicGSH. We confirmed that succinicGSH, which is all but absent from normal cells, accumulates in both human and mouse FH-deficient cells and in the kidneys of Fh1-deficient animals, suggesting that this metabolite could be used as a beacon for toxic accumulation of fumarate. In the work presented here we showed that succinicGSH is formed by a non-enzymatic reaction between fumarate and the thiol residue of de-novo biosynthesised GSH. Furthermore, we found that succinicGSH is secreted by FH-deficient cells and can be degraded, in a process similar to GSH catabolism, into succinic cys-gly.

SuccinicGSH has been recently identified in the human FH-deficient cancer cell line UOK26210. In this work, Sullivan and colleagues proposed that the detoxification of succinicGSH mediated by GR explains the enhanced oxidative stress in FH-deficient cells 10. However, our data showed that the contribution of GR to succinicGSH degradation is minor and unlikely to account for increased oxidative stress in these cells. Instead, we found that succination of GSH significantly increases the demands of NADPH to sustain GSH biosynthesis from cysteine. This reaction negatively affects redox homeostasis and, as a compensatory mechanism, FH-deficient cells enhance cystine uptake and GSH biosynthesis. Therefore, although FH-deficient cells experience a chronic oxidative stress, GSH levels are not compromised in these cells. How these cells genetically orchestrate this metabolic reprogramming is not known. The accumulation of fumarate in FH-deficient human cancers has been previously linked with the activation of the transcription factor Nrf25,7, which elicits an antioxidant response and prevents the elevation of ROS to toxic levels in these cells. Keap1 is also regulated by oxidation of its thiol residues 21 therefore the increased oxidative stress observed in FH-deficient cells could also contribute to Nrf2 activation. We hypothesise that both the redox stress caused by GSH succination and Keap1 succination contribute to the emergence of the antioxidant signature and Nrf2 activation to support GSH biosynthesis and to maintain a viable level of oxidative stress.

Persistent oxidative stress has been previously linked to the induction of senescence16. We reasoned that overt oxidative stress caused by the loss of FH in non-transformed cells could instigate a tumour suppressive mechanism that could explain why Fh1-deficient animals do not develop carcinomas but only benign cysts19. In order to accurately dissect the effects of accumulation of fumarate in early phases of epithelial transformation, we silenced FH in non-immortalised non-transformed cells. In primary epithelial kidney cells and in human diploid fibroblasts, the loss of FH or incubation with DMF leads to a robust induction of senescence, confirmed by proliferative arrest, p21 up-regulation and SA-β-galactosidase activity. The incubation with antioxidants abrogated the anti-proliferative response, suggesting that the oxidative stress induced by fumarate accumulation is responsible for the induction of senescence. In line with these results, we observed that some renal cysts exhibit a strong positive staining for p21, indicating that senescence is also a factor that may prevent or delay malignant transformation in vivo. In line with this notion, the co-ablation of p21 and Fh1 resulted in high proportion of hyperprolifearative areas in the kidney. Importantly, p21, but not p16 induction is also observed in human HLRCC patients (Supplementary Fig.4). These results confirm the association between FH loss and p21 induction in human tumours. Furthermore, they may indicate that in human FH-deficient renal cancer, the lack of p16 induction may help avoiding the senescence phenotype.

The observation that the loss of FH, a bona fide tumour suppressor gene22, could lead to senescence, although counterintuitive, suggests that the role of FH in tumorigenesis is complex and might involve secondary oncogenic alterations to overcome senescence. It is worth mentioning that the loss of FH is not the only example of an oncogenic event that leads to senescence at early stages of tumorigenesis. Other examples include the loss of the tumour suppressors VHL and PTEN23,24 as well as the activation of the oncogenes Ras or BRAF25,26,27. Although the underlying mechanisms that lead to senescence within these models might be different, a general accepted paradigm is that the unrestrained proliferation elicited by an oncogenic event leads to the activation of tumour restraining events. In this work we demonstrated that in the case of FH loss, this activity is mediated by fumarate, at least in part via GSH succination.

Methods

Animal work

Animal work was carried out with ethical approval from University of Glasgow under the Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and the EU Directive 2010 (PPL 60/4181). Animals were housed in individual ventilated cages in a barrier facility proactive in environmental enrichment. AhCre and p21−/− (Cdkn1atm1Led) mice were sourced from Owen Sansom (Cancer Research UK, Beatson Institute, Glasgow)28,29, Fhfl/fl mice kindly provided by Iain Tomlinson (University of Oxford) 19 and all were maintained on a C57Bl6 background. Experimental mice (mixed sex) were aged to 12-18 months and no difference between male and female animals was observed.

Cell culture

Fh1fl/fl, Fh1Δ/Δ, UOK262 and UOK262pFH cell lines were obtained and cultured as previously described8. In brief, all cell lines were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM glutamine. The mouse cell lines were also supplemented with 1 mM pyruvate and 50 μg·mL−1 uridine.

Immunohistochemistry

Mouse kidneys were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and paraffin embedded. 4um sections were cut and stained for Ki67 (1:100 Thermo RM-9106), Cytokeratin (Cytokeratin, Pan Ab-1, Mouse Monoclonal Antibody 1:100, Thermo, MS-34) and p21 (1:500 Santa Cruz, sc471)

Chemical reagents

Unless otherwise stated, all chemical compounds were purchased form Sigma (Gillingham, Dorset, UK). 13C-labelled compounds were purchased by Cambridge Isotopoes (Tewksbury, MA)

The transcriptomics signature of FH-deficient cells

To examine whether the Fh1Δ/Δ cells are under oxidative stress based on their gene expression (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE63438) we identified genes whose expression is significantly higher in the Fh1Δ/Δ cells compared to the Fh1fl/fl cells (FDR corrected p-values < 0.05)8. We then assembled a set of 281 genes that are known to be involved in the response to oxidative stress. This set includes genes that are annotated with one of the 32 Gene Ontology (GO) terms which are child-terms of the GO term Response to oxidative stress30 (e.g., response to reactive oxygen species, response to superoxide, response to oxygen radical). We examined if the genes that are significantly up-regulated in the Fh1Δ/Δ cells compared to the Fh1fl/fl cells are enriched with this set of oxidative stress genes, via a hypergeometric enrichment test. We then examined if FH-deficiency induces a gene expression signature of oxidative stress also in clinical samples. To this end we analyzed a previously defined set of 1397 genes that are up-regulated in HLRCC relative to normal kidney tissues7, and tested if this set is enriched with oxidative stress genes by performing a hypergeometric enrichment test.

Metabolomic extraction of mouse tissue

Kidneys were excised and immediately processed for metabolomics extraction. Equal amounts of renal tissue were lysed in 250 μL of extraction solution per each 10 mg of tissue in Precellysis vials following manufacturer’s instruction. The extraction solution contained 30% acetonitrile, 50% methanol and 20% water. The suspension thus generated was immediately centrifuged at 16,000g for 15 minutes at 0°C. The supernatant was then submitted to LC-MS metabolomic analysis.

Metabolomic extraction of cell lines

5×105 cells were plated onto 6-well plates and cultured in standard medium for 24 hours. For the intracellular metabolomic analysis, cells were quickly washed for three times with phosphate buffer saline solution (PBS) to remove contaminations from the media. The PBS was thoroughly aspirated and cells were lysed by adding a pre-cooled ES. The cell number was counted in a parallel control dish, and cells were lysed in 1 ml of ES per 1×106 cells. The cell lysates were vortexed for 5 minutes at 4°C and immediately centrifuged at 16,000g for 15 minutes at 0°C. The supernatants were collected and analyzed by LC-MS. For the metabolomic extraction of spent media, 50 μL of cell media were deproteinized by 1:16 dilution in a solution composed of 80% acetonitrile and 20% water. The supernatants were then processed as described above. Fresh medium without cells was incubated in the same experimental conditions and used as a reference.

LC-MS metabolomic analysis

For the LC separation, column A was the Sequant Zic-Hilic (150 mm × 4.6 mm, internal diameter (i.d.) 5 μm) with a guard column (20 mm × 2.1 mm i.d. 5 μm) from HiChrom, Reading, UK. Mobile phase A: 0.1% formic acid v/v in water. Mobile B: 0.1% formic acid v/v in acetonitrile. The flow rate was kept at 300 μL·min−1 and gradient was as follows: 0 minutes 80% of B, 12 minutes 50% of B, 26 minutes 50% of B, 28 minutes 20% of B, 36 minutes 20% of B, 37-45 minutes 80% of B. Column B was the sequant Zic-pHilic (150 mm × 2.1 mm i.d. 5 μm) with the guard column (20 mm × 2.1 mm i.d. 5 μm) from HiChrom, Reading, UK. Mobile phase C: 20 mM ammonium carbonate plus 0.1% ammonia hydroxide in water. Mobile phase D: acetonitrile. The flow rate was kept at 100 μL·min−1 and gradient as follow: 0 minutes 80% of D, 30 minutes 20% of D, 31 minutes 80% of D, 45 minutes 80% of D. The mass spectrometer (Thermo Exactive Orbitrap) was operated in a polarity switching mode.

13C-Glutamine and Cystine labelling experiments

5×105 cells were plated onto 6-well plates and cultured in standard medium for 12 hours. The medium was then replaced by fresh medium supplemented with either 2 mM U-13C-Glutamine or 0.2 mM 13C2-Cystine for the indicated time.

Orbitrap-Velos MS2 fragmentation

The S-(1, 2-Dicarboxyethyl) glutathione standard (H-1556.1000, Bachem) was dissolved in water and diluted to 40 μg·mL−1 with a 50% mixture of acetonitrile and water. An Orbitrap-Velos mass spectrometer was used in the negative mode, with HCD fragmentation MS2 energy of 50 unit.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) measurement

Proton and two-dimensional pfgCOSY as well as pfgTOCSY were measured for standards and samples on an ECX 400 Jeol NMR equipped with a pulse-field gradient autotune 40TH5AT/FG broadband high sensitivity probe. 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 3.98 (s, 2H), 3.85 - 3.71 (m, 2H), 3.38 (s, 1H), 2.97 (dq, J = 18.1, 9.3 Hz, 3H), 2.75 (dd, J = 17.1, 5.9 Hz, 3H), 2.72 - 2.58 (m, 1H), 2.22 (m, 1H).

Bioinformatics processing and statistical analysis of the metabolomic data

The metabolomics analyses obtained from cells and media extractions were log2 transformed and the replicates normalized using quantile normalization. Then, a multi-factor analysis of variance and multiple test correction were used to identify metabolites significantly different between experimental groups. Analyses were performed using Partek Genomics Suite Software, version 6.5 Copyright 2010 and R version 2.14.0.

In vitro succination reaction

2 mM glutathione and 8 mM 13C2-fumarate were mixed in 2 mL of a solution composed of 50mM NaCl, 20mM Tris and 0.1% Triton X-100, pH=7.4, 4°C for 8 hours in the presence or absence of cell lysate obtained from 2×106 Fh1Δ/Δ cells previously heat inactivated (100°C for 1 hour) or left untreated. Protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) was used following manufacturer’s instructions. At the end of the experiment, the mixture was quenched using the extraction solution for metabolomics (see above) and the extracts were spun down at maximum speed for 10 minutes. The supernatant was subsequently analysed by LC-MS.

DMF treatment

5×105 cells were plated onto 6-well plates and cultured in standard medium for 24 hours. Then the cell culture medium was replaced with medium supplemented with the indicated concentrations of DMF for the indicated time. Cells were then harvested and extracted as described above.

Glutathione Reductase Assay

SuccinicGSH (0.2mM, purchased from BACHEM) and GSSG (2mM) were separately dissolved in a solution containing 50 mM Tris and 5 mM EDTA. The pH was adjusted at 7.8 to mimic the pH of the mitochondrial matrix. Substrates were added to a solution of 250 μM NADPH and 0.05 U·ml−1 glutathione reductase. Metabolite production was monitored by LC-MS.

qPCR experiments

mRNA was extracted as previously described8. In brief, RNA was extracted from cells of the indicated genotype using the Qiagen RNAeasy RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Manchester, UK) following the manufacturer’s instructions.1 μg of mRNA was retro-transcribed into cDNA using High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK). qPCR reaction was performed using 200 ng of cDNA, the indicated primers, and fast Sybr green mastermix (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK). Primers were designed using ROCHE universal probe library primer design tool (version 2.45 and 2.48) and the sequences were as follow:

p21 FW: 5′- GAGGGCTAAGGCCGAAGATG-3′, RV: 5′- GCAGACCAGCCTGACAGATTTC-3′

Rpl34 FW: 5′-GTGAGGGACGAGGAGAGGTG-3′, RV: 5′-ACCATCCTGAGTGCCGCTTC-3′

Slc7a11 FW: 5′- TGGGTGGAACTGCTCGTAAT-3′, RV: 5′- AGGATGTAGCGTCCAAATGC-3′

DDIT3 FW: 5-GCGACAGAGCCAGAATAACA-3′, RV 5′- GATGCACTTCCTTCTGGAACA-3′

PTGS1 FV: 5′- CCTCTTTCCAGGAGCTCACA-3′, RV: 5′- TCGATGTCACCGTACAGCTC-3′

PYCR1 FW: 5′- CTGACCATGTCAAGCCACTG-3′, RV 5′- TTCCCAGGGATAGCTGAGGT-3′

NQO1 FW: 5′- AGCGTTCGGTATTACGATCC-3′, RV: 5′- AGTACAATCAGGGCTCTTCTCG-3′

ABCB1A FW: 5′- GGGCATTTACTTCAAACTTGTCA-3′, RV: 5′- TTTACAAGCTTCATTTCCTAATTCAA-3′

GCLC FW: 5′- ATGATAGAACACGGGAGGAGAG-3′, RV: 5′- TGATCCTAAAGCGATTGTTCTTC-3′

HMOX1 FW: 5′- GTCAAGCACAGGGTGACAGA-3′ RV 5′- ATCACCTGCAGCTCCTCAAA-3′

For the qPCR reactions 0.5 μM primers were used. 1 μL of Fast Sybr green gene expression master mix; 1 μL of each primers and a 4 μL of a 1:10 dilution of cDNA in a final volume of 20 μL were used. Real-time PCR was performed in the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies) using the fast Sybrgreen program and expression levels of the indicated genes were calculated using the ΔΔCt method by the appropriate function of the software using actin as calibrator.

Primary kidney cells isolation and infection

Primary kidney epithelial cells were isolated from Fh1+/+ and Fh1fl/fl p5 mice as described previously31 and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine and 1 mmol·L−1 pyruvate. Cells were infected with Cre recombinase-encoding adenovirus (Ad5-CMV-Cre-GFP, Vector Development Laboratory) using 200 pfu per cell. After 2 days, cells were transferred on 24 well plates for growth curve determination and SA-β-Gal Staining.

Lentiviral infection of IMR90

The viral supernatant for infection was obtained from the filtered growth media of the packaging cells HEK293T transfected with 3μg psPAX, 1μg pVSVG, 4μg of shRNA constructs and 24μl Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technology). 3×105 cells were then plated on 6-well plates and infected with the viral supernatant in the presence of 4 μg·mL−1 polybrene. After two days, the medium was replaced with selection medium containing 1 μg·mL−1 puromycin. The expression of the shRNA constructs was induced by incubating cells with 2μg·mL−1 doxycyclin. The shRNA sequences were purchased from Thermoscientific (NTC: # RHS4743; sh #2 V3THS_324847 and sh#3: V3THS_324846)

Senescence Associated (SA)-β-Gal Staining

For mouse epithelial kidney cells, 4×104 cells were treated for 2 days with 50 μM DMF and a Senescence β-Galactosidase Staining Kit (Cell Signaling Technology) was used. The staining was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions and images were acquired with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope. To quantify SA-β-gal positive cells, cells were counted in 4 random fields in each of the triplicates wells.

For IMR90, 4×104 cells were plated onto coverslips in a 24 well plate. The day after, the medium was replaced with medium containing either DMF or NAC or a combination of the two drugs. The medium was replenished every day for a total of 5 days of treatment-. At the end of the experiment, cells were washed in PBS and fixed with 0.5% glutaraldehyde solution (in PBS) for 15 min at RT. Immediately after cells were washed twice with 1mM MgCl2 in PBS (pH 6.0) and incubated with a staining solution composed of 1 mg·ml−1 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-ß-D-galactopyranoside (prepared in N,N-dimethylformamide), 0.12 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 0.12 mM K4Fe(CN)6 and 1mM MgCl2/ PBS (pH 6.0) at 37°C overnight in CO2-free incubator. The day after, cells were washed three times with deionized water and imaged with a Zeiss Axiovert 40 CFL microscope using a 10× objective.

Cell proliferation

4×104 IMR90 were plated in a 24 well plate and placed onto the stage of the Incucyte Live Content Imaging instrument. 9 fields for each well were collected every two hours for the first day and then every hour for the following days. Cell proliferation was automatically determined from bright-filed images by calculating cell confluence at different time points, using the appropriate function of the Incucyte software. Cell media was replaced daily with media supplemented with the indicated drugs.

Generation of the metabolic models of Fh1Δ/Δ and Fh1fl/fl cells

To investigate the metabolic changes that occur due to FH-inactivation metabolic models of Fh1Δ/Δ and Fh1fl/fl cell lines were constructed based on their transcriptomics and uptake-secretion metabolomics. The construction was conducted in two stages. In the first stage each model was constrained to obtain an optimal fit to the gene expression signature of the cell line by solving a Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) problem, via the integrative Metabolic Analysis Tool (iMAT)32,33. In the second stage each model was further constrained to obtain an optimal fit to the measured uptake-secretion flux rates. The latter was achieved by forming the following problem:

| (1) |

subject to

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Where v is the flux vector, and S is an m × n stoichiometric matrix, in which m is the number of metabolites and n is the number of reactions. The mass balance constraint is enforced by equation (2). Thermodynamic and enzyme capacity constraints are imposed in equation (3), by setting vi,min and vi,max as a lower and upper bound of the flux values through reaction i, respectively. In (4) Rm includes the set of measured reactions; for each measured reaction i, the variables yi represents the deviation of its computed flux rate, denoted as vi, from its measured flux rate, denoted as fi. The objective function (1) is to minimize the deviation of the computational flux rates from the measured flux rates. To avoid the non-linear constraint imposed in (4) two variables, y+ and y−, are introduced to convert the problem to its equivalent linear form.

| (1) |

subject to

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

A solution found by the MILP solver to the iMAT problem and then by a Linear Programming (LP) solver to the problem formulated above is guaranteed to be optimal, meaning, to maximize the similarity to the expression and then, under the optimal fit to the transcriptomics to obtain a maximal fit to the flux measurements. However, the solution is not necessarily unique, as a space of alternative optimal solutions may exist. The space of optimal solutions represents various steady-state flux distributions attaining the same similarity with the expression data and flux measurements. To account for these alternative solutions, the optimal similarity to the expression and flux-measurements is calculated. The model is then constrained to attain this optimal similarity, which reduces the solution space significantly.

To explore the optimal solution space of the model, that is, the feasible metabolic states which maximize the fit to the experimental data, Flux Variability Analysis (FVA)34 was employed. FVA obtains for each reaction its minimal and maximal attainable flux, subject to the aforementioned constraints. Additionally, by applying FVA the maximal production rate of every metabolite in the models was computed; in this case the production of a metabolite was defined as the sum of its production rates in all the different compartments of the model (e.g., mitochondria, cytoplasm). For each metabolic pathway the median fold-change in the production of its metabolites was computed based on the pathway definition of13. Lastly, the redox potential of the models was estimated by computing their capacity to produce NADH and NADPH from NAD+ NADP+, respectively.

The metabolic model of the FH-deficient cells were utilized to examine the dependency of GSH-production on the uptake-secretion rates of different metabolites, including amino acids and main carbon sources. First, for each metabolite in this set the feasible flux-range of its exchange reaction was computed via FVA. An exchange reaction represents the secretion or uptake of a given metabolite. A positive flux rate through an exchange reaction denotes secretion and a negative flux rate denotes uptake. Next, for every one of the metabolites the model was constrained to carry out an increasing flux of its exchange reaction, which is within its feasible flux range. Under each of these constraints the maximal production of reduced GSH in the model was computed. Lastly, for each metabolite, the Spearman correlation between the upper bounds of the metabolite exchange reaction and the pertaining maximal production rates of GSH was computed. A positive correlation, as found between GSH production and arginine, denotes that a higher flux rate through the exchange reaction of the metabolite – less uptake or more secretion – enables the model to produce GSH more rapidly. Likewise, a negative correlation, as found between GSH production and cystine, denotes that a lower flux rate through the exchange reaction of the metabolite – more uptake or less secretion – enables the model to produce GSH more rapidly.

The ability of the models to predict the measured flux rates was examined in a leave-one-out cross validation process. Every iteration, the models were regenerated based on their gene expression and a partial set of the metabolic uptake and secretion rates. These models were then used to compute via FVA the maximal and minimal flux-rate of the exchange reaction whose flux measurement was omitted from the construction process. Significant correlation was found between the measured and predicted flux rates (Supplementary Table 2).

Following the validation of the models, they were utilized to systematically explore the metabolic differences between the Fh1Δ/Δ and Fh1fl/fl cells. The capacity of the two models to produce each of their 1,491 metabolites was computed. The FH-deficient model was found to have a higher capacity to produce 43 metabolites (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Among the top ones are four derivatives of glutathione: Oxidized glutathione, reduced glutathione, (R)-S-Lactoylgutathione, and S-Formylglutathione (Supplementary Fig. 1b). These results suggest that FH-deficiency induces oxidative stress. To further examine this hypothesis the ability of the Fh1fl/fl and Fh1Δ/Δ models to produce reducing power in the form of NADH and NADPH was computed. Indeed, the Fh1fl/fl model was found to have a significantly higher capacity to produce NADH and NADPH, compared to the Fh1Δ/Δ model.

Following the discovery of GSH succination in the FH-deficient cells, the models were reconstructed with GSH succination (see next section). According to the updated models, GSH succination further severely limits NADPH and NADH production in Fh1Δ/Δ cells. This strong coupling between GSH succination and decreased NADH/NADPH production is highly notable, since the activity of almost all other reactions in the Fh1Δ/Δ model does not entail such a decrease (Supplementary Fig. 1c, Wilcoxon ranksum p-value of 7.91e-04). Further computational analysis revealed that this coupling arises since, in the Fh1Δ/Δ cells, GSH synthesis depends on cystine uptake, rather than on methionine uptake (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The synthesis of GSH from cystine causes the oxidation of two GSH molecules. As reducing them requires NADPH, it imposes a constraint to activate pathways that contribute to NADPH production.

GSH-succination was introduced to the models by adding the following reactions

Mitochondrial reaction: reduced-GSH [m] + fumarate [m] → succinicGSH

Cytoplasmatic reaction: reduced-GSH [c] + fumarate [c] → succinicGSH

Sink reaction: succinicGSH

Reaction (3) denotes the secretion of succinicGSH. In the FH-deficient model this reaction was constrained to carry a non-zero flux. Note that some of the succinicGSH may be metabolized via additional metabolic reactions which are yet to be discovered, as opposed to secreted. However, currently the models cannot account for such reactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Cancer Research UK. L.J. is partially funded by the Edmond J. Safra bioinformatics center and the Israeli Center of Research Excellence program (I-CORE, Gene Regulation in Complex Human Disease Center No 41/11), and an Adams fellowship. E.R. research in cancer is supported by grants from the Israeli Science Foundation (ISF), the Israeli Cancer Research Fund (ICRF) and the I-CORE program. We thank UOB Tumor Cell Line Repository and Dr. W. Marston Linehan, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA for providing us with the UOK262 cell lines.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Tomlinson IPM, et al. Germline mutations in FH predispose to dominantly inherited uterine fibroids, skin leiomyomata and papillary renal cell cancer. Nature Genetics. 2002;30:406–410. doi: 10.1038/ng849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frezza C, Pollard PJ, Gottlieb E. Inborn and acquired metabolic defects in cancer. Journal of molecular medicine. 2011;89:213–220. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0728-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isaacs JS, et al. HIF overexpression correlates with biallelic loss of fumarate hydratase in renal cancer: novel role of fumarate in regulation of HIF stability. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollard PJ, et al. Accumulation of Krebs cycle intermediates and over-expression of HIF1alpha in tumours which result from germline FH and SDH mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2231–2239. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adam J, et al. Renal cyst formation in Fh1-deficient mice is independent of the Hif/Phd pathway: roles for fumarate in KEAP1 succination and Nrf2 signaling. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:524–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Covvey JR, Johnson BF, Elliott V, Malcolm W, Mullen AB. An association between socioeconomic deprivation and primary care antibiotic prescribing in Scotland. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:835–841. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ooi A, et al. An antioxidant response phenotype shared between hereditary and sporadic type 2 papillary renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:511–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frezza C, et al. Haem oxygenase is synthetically lethal with the tumour suppressor fumarate hydratase. Nature. 2011;477:225–228. doi: 10.1038/nature10363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sudarshan S, et al. Fumarate hydratase deficiency in renal cancer induces glycolytic addiction and hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1alpha stabilization by glucose-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species. Molecular and cellular biology. 2009;29:4080–4090. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00483-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan LB, et al. The Proto-oncometabolite Fumarate Binds Glutathione to Amplify ROS-Dependent Signaling. Mol Cell. 2013;51:236–248. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shlomi T, Benyamini T, Gottlieb E, Sharan R, Ruppin E. Genome-scale metabolic modeling elucidates the role of proliferative adaptation in causing the Warburg effect. PLoS computational biology. 2011;7:e1002018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folger O, et al. Predicting selective drug targets in cancer through metabolic networks. Molecular systems biology. 2011;7:501. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duarte NC, et al. Global reconstruction of the human metabolic network based on genomic and bibliomic data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:1777–1782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610772104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fabrini R, et al. The extended catalysis of glutathione transferase. FEBS letters. 2011;585:341–345. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng L, et al. Reversed argininosuccinate lyase activity in fumarate hydratase-deficient cancer cells. Cancer Metab. 2013;1:12. doi: 10.1186/2049-3002-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, et al. UOK 262 cell line, fumarate hydratase deficient (FH-/FH-) hereditary leiomyomatosis renal cell carcinoma: in vitro and in vivo model of an aberrant energy metabolic pathway in human cancer. Cancer genetics and cytogenetics. 2010;196:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashrafian H, et al. Expression profiling in progressive stages of fumarate-hydratase deficiency: the contribution of metabolic changes to tumorigenesis. Cancer research. 2010;70:9153–9165. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serrano M, Blasco MA. Putting the stress on senescence. Current opinion in cell biology. 2001;13:748–753. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollard PJ, et al. Targeted inactivation of fh1 causes proliferative renal cyst development and activation of the hypoxia pathway. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scholzen T, Gerdes J. The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. Journal of cellular physiology. 2000;182:311–322. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200003)182:3<311::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaspar JW, Niture SK, Jaiswal AK. Nrf2:INrf2 (Keap1) signaling in oxidative stress. Free radical biology & medicine. 2009;47:1304–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottlieb E, Tomlinson IP. Mitochondrial tumour suppressors: a genetic and biochemical update. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young DW, et al. Integrating high-content screening and ligand-target prediction to identify mechanism of action. Nature chemical biology. 2008;4:59–68. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Z, et al. Crucial role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;436:725–730. doi: 10.1038/nature03918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collado M, Blasco MA, Serrano M. Cellular senescence in cancer and aging. Cell. 2007;130:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michaloglou C, et al. BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi. Nature. 2005;436:720–724. doi: 10.1038/nature03890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplon J, et al. A key role for mitochondrial gatekeeper pyruvate dehydrogenase in oncogene-induced senescence. Nature. 2013;498:109–112. doi: 10.1038/nature12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ireland H, et al. Inducible Cre-mediated control of gene expression in the murine gastrointestinal tract: effect of loss of beta-catenin. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1236–1246. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng C, Zhang P, Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Leder P. Mice lacking p21CIP1/WAF1 undergo normal development, but are defective in G1 checkpoint control. Cell. 1995;82:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashburner M, et al. The Gene Ontology Consortium Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature Genetics. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathew R, Degenhardt K, Haramaty L, Karp CM, White E. Immortalized mouse epithelial cell models to study the role of apoptosis in cancer. Methods in enzymology. 2008;446:77–106. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)01605-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zur H, Ruppin E, Shlomi T. iMAT: an integrative metabolic analysis tool. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:3140–3142. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shlomi T, Cabili MN, Herrgard MJ, Palsson BO, Ruppin E. Network-based prediction of human tissue-specific metabolism. Nature biotechnology. 2008;26:1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahadevan R, Schilling CH. The effects of alternate optimal solutions in constraint-based genome-scale metabolic models. Metabolic engineering. 2003;5:264–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.