Abstract

Background

RNF4 is a ubiquitin ligase targeted to SUMOylated proteins.

Result

USP11 co-purified with RNF4 and can remove ubiquitin polymers attached to SUMO chains.

Conclusion

USP11 is a ubiquitin protease with the ability to counteract RNF4 in the DNA damage response.

Significance

Identification of a ubiquitin protease to balance the activity of a SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase.

RNF4 is a SUMO-targeted ubiquitin E3 ligase with a pivotal function in the DNA damage response (DDR). SUMO Interaction Motifs (SIMs) in the N-terminal part of RNF4 tightly bind to SUMO polymers, and RNF4 can ubiquitinate these polymers in vitro. Using a proteomic approach, we identified the deubiquitinating enzyme USP11, a known DDR-component, as a functional interactor of RNF4. USP11 can deubiquitinate hybrid SUMO-ubiquitin chains to counteract RNF4. SUMO-enriched nuclear bodies are stabilized by USP11, which functions downstream of RNF4 as a counterbalancing factor. In response to DNA damage induced by methyl methanesulfonate, USP11 could counteract RNF4 to inhibit the dissolution of nuclear bodies. Thus, we provide novel insight into crosstalk between ubiquitin and SUMO, and uncover USP11 and RNF4 as a balanced SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase/protease pair with a role in the DDR.

Keywords: Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO), USP11, RING finger protein 4 (RNF4), ubiquitin, E3 ubiquitin ligase, ubiquitin-dependent protease, DNA damage response, STUbL, proteasome

Small Ubiquitin-like Modifiers (SUMOs) are predominantly located in the nucleus and play key roles in all nuclear processes including transcription, chromatin modification and maintenance of genome stability (1). Analogous to the ubiquitin system, a set of E1, E2 and E3 enzymes mediate the conjugation of SUMO to target proteins, and a set of SUMO-specific proteases is responsible for the reversible nature of this post-translational modification (2,3). Mouse models have shown that the SUMOylation system is essential for embryonic development. Mice deficient for the single SUMO E2 enzyme Ubc9 die at the early post-implantation stage as a result of hypocondensation and other chromosomal aberrancies (4).

Large sets of target proteins have been identified for the different SUMO family members, involved in all different nuclear processes (5-7). About half of the SUMO acceptor lysines in these target proteins are located in short stretches that fit the SUMOylation consensus motif ΨKxE (7,8), a motif that is directly recognized by Ubc9 (9,10). Internal SUMOylation consensus motifs in human SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 enable SUMO polymerization (11-14). SUMO signal transduction furthermore includes proteins that bind non-covalently to SUMOylated proteins via SUMO-Interaction Motifs (SIMs) (15), including the novel SUMO-binding Zinc finger identified in HERC2 (16).

Interestingly, extensive crosstalk exists between the SUMOylation system and the ubiquitination system (17,18). This crosstalk includes competition between SUMO and ubiquitin for the same acceptor lysines (19), or sequential modification by SUMO and ubiquitin of a target protein (20). Moreover, the SUMO system is tightly connected to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway since a significant subset of SUMO-2/3 target proteins is subsequently ubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome (21,22). Inhibition of the proteasome led to accumulation of SUMO-2/3 conjugates and the depletion of the pool of non-conjugated SUMO-2/3, indicating that this biochemical pathway is required for SUMO-2/3 recycling. SUMO and ubiquitin can form hybrid chains, including via lysine 32 of SUMO-2 or lysine 33 of SUMO-3 (21).

The SUMO system and the ubiquitin system are linked together via the SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (STUbLs), responsible for ubiquitinating SUMOylated proteins. They were first identified in Schizosacharomyces pombe as Rfp1 and Rfp2 and in Saccharomyces cerevisiae as the Slx5-Slx8 complex (23-25). Rfp1 and -2 each have an N-terminal SIM and a C-terminal RING-finger domain to enable interaction with SUMOylated proteins. Ubiquitin E3 ligase activity of the Slx5-Slx8 complex is provided by the active RING-finger protein Slx8. RNF4 is a major mammalian STUbL containing four N-terminal SIMs and a C-terminal RING domain that enables homodimerization (26). More recently, RNF111/Arkadia was identified as a second mammalian STUbL (27,28).

STUbLs play key roles in the DNA damage response (29). Schizosacharomyces pombe strains deficient for STUbLs display genomic instability and are hypersensitive to different DNA damaging agents including hydroxyurea (HU), methylmethane sulfonate (MMS), camptothecin (CPT) and ultraviolet (UV) light (23,24). RNF4 knockdown in human cells also results in increased sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents (30). Moreover, RNF4 accumulates at DNA damage sites induced by laser micro-irradiation (30-32). SUMOylated target proteins for RNF4 include MDC1 and BRCA1 (32,33) and furthermore HIF-2α (34). Mice deficient for RNF4 die during embryogenesis (32,35). Mice expressing strongly reduced levels of RNF4 are born alive, albeit at a reduced Mendelian ratio, and showed an age-dependent impairment in spermatogenesis (32). MEFs derived from these mice exhibit increased sensitivity to genotoxic stress.

A key feature of ubiquitin-like modification systems is their reversible nature to carefully balance the systems (2,36). Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) play a pivotal role in the regulation of cellular ubiquitination levels, essentially controlling all cellular processes. Around 100 mammalian DUBs exist, with different substrate specificity, subcellular localization, and protein-protein interactions (36,37). Currently, it is not clear how the activity of the STUbLs is balanced. Here, we report the identification of a ubiquitin-specific protease with the ability to counteract RNF4.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

The cDNA encoding the USP11 protein was a kind gift from Dr. L. Zhang and Prof. P. ten Dijke in our institute. The cDNA encoding the RNF4 protein was obtained from the Mammalian Gene Collection (Image ID 4824114; supplied by Source Bioscience). Both cDNAs were amplified by a two-step PCR reaction using the following primers: 5′-AAAAAGCAGGCTATATGGCAGTAGCCCCGCGACTG-3′ and 5′-AGAAAGCTGGGTGTCAATTAACATCCATG AACTC-3′ (USP11), 5′-AAAAAGCAGGCTCAATGAGTACAAGAAAGC-3′ and 5′-AGAAAGCTGGGTTTCATATATAAATGGGGTG-3′ (RNF4) for the first reaction and 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCT-3′ and 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGT-3′ for the second reaction. RNF4 was cloned in between the SpeI and XhoI sites of the plasmid pLV-CMV-X-FLAG-IRES-GFP (kind gift from Dr. R.C. Hoeben). Additionally, RNF4 and USP11 cDNAs were inserted into pDON207 employing standard Gateway technology (Life Technologies). The C318A mutation in USP11 was introduced by QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) using oligonucleotides 5′-CAATCTGGGCAACACGGCCTTCATGAACTCGG-3′ and 5′-CCGAGTTCATGAAGGCCGTGTTGCCCAGATTG-3′. These different cDNAs were subsequently transferred to the destination vector pDEST-T7-His6-MBP (a kind gift from Dr. L. Fradkin in our institute). RNF4 was cloned into pGEX-2T to obtain a construct encoding GST-tagged RNF4 by amplifying RNF4 cDNA using the following primers: 5′-ACAAACGGATCCATGAGTACAAGAAAGCGTCGTG-3′ and 5′-GCCGCGGAATTCTCATATATAAATGGGGTGGT AC-3′. Both the PCR product and the pGEX-2T vector were subsequently digested with BamHI and EcoRI and the PCR product was ligated into the vector with T4 ligase (New England Biolabs). The His6-ΔN11-SUMO-2-Tetramer expression vector was a kind gift of Prof. Dr. R.T. Hay (Dundee, U.K.) (26). The His6 tag was extended to His10 through PCR.

Cell culture & cell line generation, transfection and treatments

MCF7, U2-OS and HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin (Life Technologies). MCF7 cells stably expressing RNF4-FLAG were generated through lentiviral infection with a construct carrying RNF4-FLAG-IRES-GFP. Two weeks after infection, cells were sorted for a low level of GFP by flow cytometry, using a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences). Cells were treated with 0.02% MMS (Sigma) for the indicated amounts of time. Transfections were performed using 2.5 μg of polyethylenimine (PEI) per 1 μg of plasmid DNA, using 1 μg of DNA per 1 million cells. Transfection reagents were mixed in 150 mL NaCl and incubated for 15 minutes prior to transfection. Cells were split after 24 hours (if applicable) and investigated after 48 hours.

RNF4-FLAG purification

Parental MCF7 cells and MCF7 cells stably expressing RNF4-FLAG were grown in regular DMEM, until confluent in ten 15-cm dishes (approximately 0.2 billion cells). Cells were washed 3 times in ice-cold PBS prior to addition of 3 mL of ice-cold lysis buffer to each plate (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM TRIS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1.0% N-P40, buffered at pH 7.5, with every 10 mL of lysis buffer supplemented by one tablet of protease inhibitors + EDTA (Roche)). Subsequently, cells were scraped in the lysis buffer, on ice, and collected in 50 mL tubes. The lysates were sonicated on ice for 10 seconds using a microtip sonicator at 30 Watts. Next, lysates were centrifuged at 4 °C and 10,000 RCF to clear debris from the soluble fraction. Lysates were equalized using the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA, Pierce). 1 μL (dry volume) of FLAG-M2 agarose beads (Sigma) was prepared per 1 mL of lysate, and equilibrated by washing 5 times in ice-cold lysis buffer. FLAG-M2 beads were added to the lysates and incubated while tumbling for 2 hours at 4 °C. Next, beads were pelleted by centrifugation at 250 RCF and washed 5 times with ice-cold lysis buffer. After every single wash step, the tubes were exchanged. RNF4-FLAG and interacting proteins were eluted off the beads by incubating them for 10 minutes with three bead volumes of lysis buffer supplemented with 1 mM FLAG-M2 peptide. Elution of the beads was repeated twice, and a fourth elution was performed with 2× LDS Sample Buffer (Novex). The primary three peptide elutions were pooled and concentrated. Culturing of cells, immunoprecipitation of RNF4-FLAG and subsequent steps leading to the LC-MS/MS analysis were performed in biological triplicate.

Purification of His-SUMO-2

Purification of His-SUMO-2-modified proteins was essentially performed as described previously (8,38).

Recombinant proteins

His6-MBP-USP11 and His-ΔN11-SUMO-2-Tetramer recombinant proteins were purified essentially as described previously (39). Briefly, BL21 cells were transformed with expression constructs. Cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.6. Subsequently, cells were grown overnight at 24°C in the presence of 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.05% Glucose. Lysates were prepared and proteins were affinity-purified on TALON beads (BD Biosciences). GST-tagged RNF4 was produced in E. coli and purified as described previously (11).

In vitro ubiquitination, binding, and deubiquitination assays

15 ng of His-ΔN11-SUMO-2-Tetramer was in vitro ubiquitinated using 8 μM ubiquitin, 40 nM UBE1, 0.7 μM UbcH5a (all from Boston Biochem), 0.5 μM GST-RNF4 in 50 mM TRIS pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, and 4 mM ATP. 50 μL reactions were incubated at 37°C for three hours after which non-ubiquitinated and ubiquitinated His-ΔN11-SUMO-2-Tetramers were bound to 50 μL Ni-NTA beads, incubated for three hours, and washed four times in washing buffer (50 mM TRIS pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM MgCl2, 20 % glycerol, 0.1 % NP40, and 50 mM Imidazole), prior to being eluted in washing buffer supplemented with 500 mM imidazole.

For the USP11 binding assay, purified non-ubiquitinated and ubiquitinated His-ΔN11-SUMO-2-Tetramers were incubated in the absence or presence of 5 μg His6-MBP-USP11 for 2 hours at 4 °C. Subsequently, His6-MBP-USP11 was purified through addition of 25 μL prewashed Amylose Resin (New England Biolabs). His6-MBP-USP11 and Amylose Resin were incubated in EBC buffer (50 mM TRIS pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.5% NP-40) for 2 hours at 4 °C, washed 5 times with EBC buffer, and eluted in 25 μL 2× LDS Sample Buffer (Novex).

For the USP11 activity assay, purified ubiquitinated His-ΔN11-SUMO-2-Tetramers were incubated in 50 mM TRIS pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM DTT with different amounts (1 to 5 μg) of His6-MBP-USP11 wild-type and catalytic-dead (C318A) proteins in a final volume of 20 μL. Reactions were incubated at 4 °C for three hours. Reactions were stopped by addition of 5 μL 4× LDS Sample Buffer (Novex).

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study: mouse α FLAG (M2, Sigma), mouse α PML (5E10, kind gift from Prof. R. van Driel, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands (40)), rabbit α USP11 (A301-613A, Bethyl), mouse α SUMO-2/3 (8A2, Abcam), rabbit α SUMO-2/3 (41), rabbit α RNF4 (32), rabbit α SART1 (41,42), and rabbit α V5 (V8137, Sigma).

Electrophoresis, Coomassie Staining and In-gel digestion

RNF4-FLAG IP samples were size-separated by SDS-PAGE using Novex 4-12% gradient gels and MES SDS running buffer (Life Technologies), followed by staining with Colloidal Blue Kit (Life Technologies). Gel lanes were excised as ten slices per eluted fraction, cut into 2-mm3 cubes and in-gel digested with sequencing-grade modified trypsin (Promega) as described before (43). The peptides extracted from the gel after digestion were cleaned, desalted and concentrated on C18 reverse phase StageTips (44).

Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting

Samples were size-separated by SDS-PAGE using Novex 4-12% BIS-TRIS gradient gels and MOPS SDS running buffer (Life Technologies), or homemade 8% acrylamide gels and TRIS-glycine running buffer. Subsequently, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences) using a submarine system (Life Technologies). Sharp Pre-stained Protein Standard (Novex) was used as a size indicator for figure 1, and SeeBlue® Plus2 Protein Standard (Life Technologies) was used as a size indicator for figures 2-6. Note that SeeBlue® Plus2 migrates differently depending on buffer conditions used, as documented on the manufacturer’s website. Ponceau-S staining and immunostaining were performed as described previously (38).

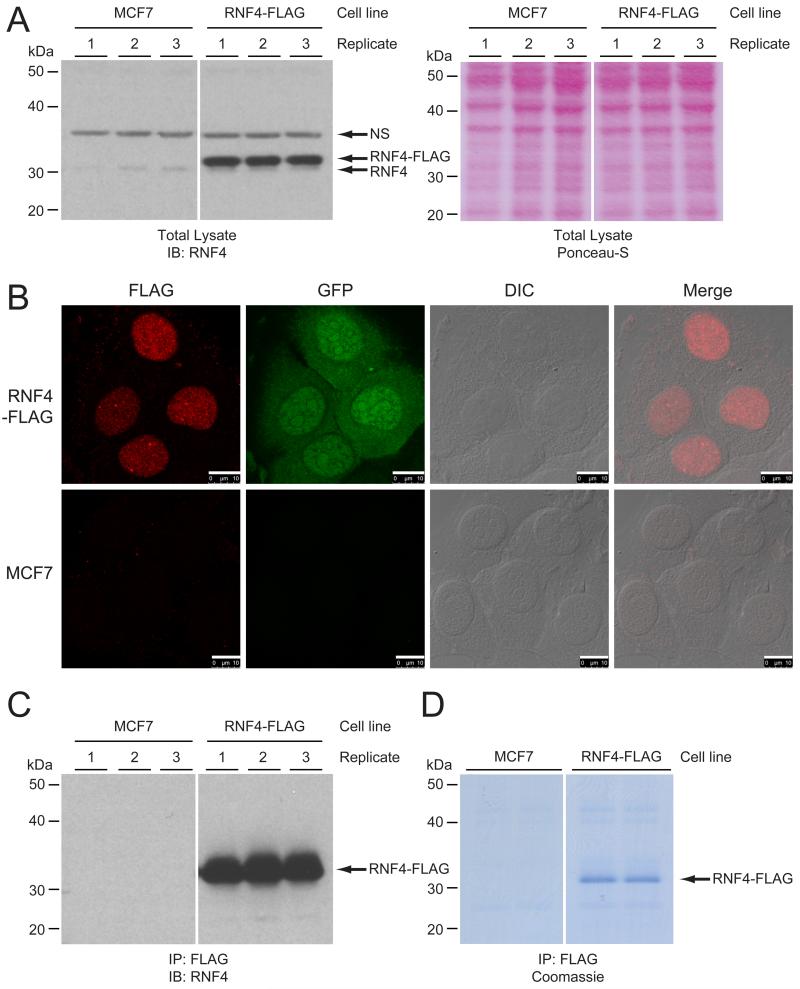

Figure 1. Generation of a cell line stably expressing RNF4-FLAG.

(A) MCF7 cells were infected with a bicistronic lentivirus encoding RNF4-FLAG and GFP separated by an Internal Ribosome Entry Site (IRES). Cells stably expressing low levels of the transgene were selected by flow cytometry. Total cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting to confirm expression of RNF4-FLAG. Ponceau-S staining of the membrane was included as a loading control. The experiment was performed in biological triplicate for mass spectrometric analysis. IB, immunoblot. NS, non-specific.

(B) Stable cell lines were investigated by confocal fluorescent microscopy to confirm the nuclear localization of RNF4-FLAG. GFP was visualized as an expression control, and differential interference contrast (DIC) was used to visualize the nuclei. Scale bars are 10 μm.

(C) RNF4 complexes were purified by immunoprecipitation (IP), and three biological replicates were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) for the presence of RNF4. Parental cells were included as a negative control.

(D) Coomassie analysis of one replicate of the FLAG-IP, loaded over two lanes, prior to in-gel digestion and analysis by LC-MS/MS.

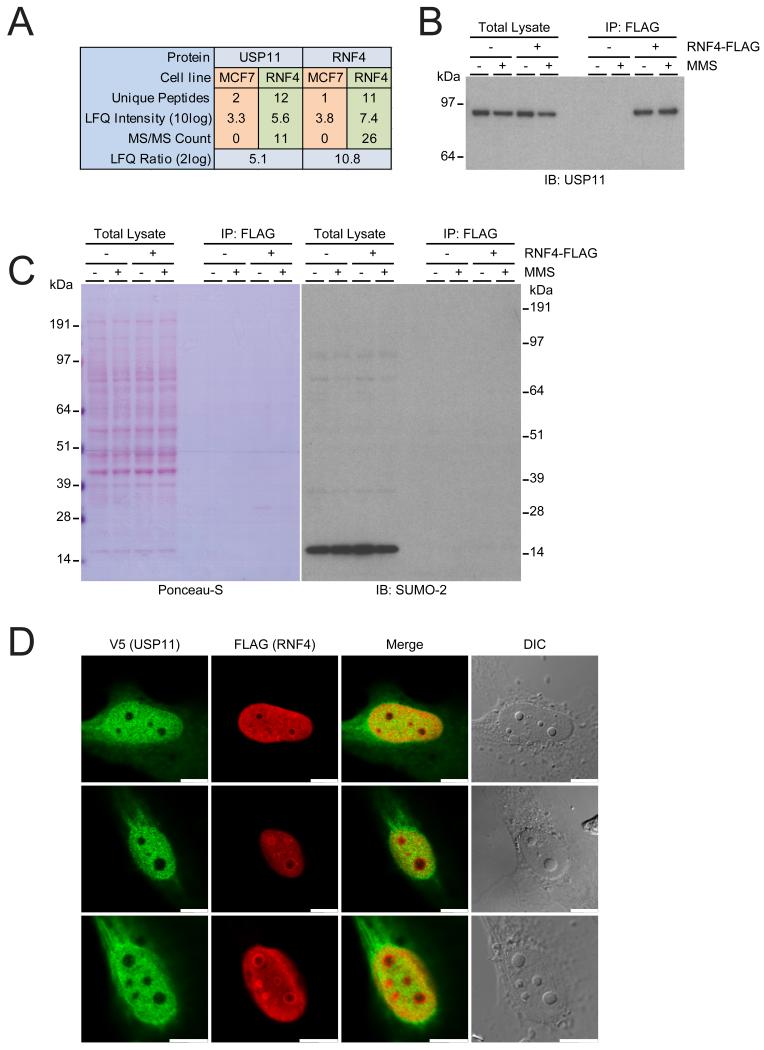

Figure 2. Identification of USP11 as an RNF4-interacting ubiquitin protease.

(A) Overview of the mass spectrometry results pertaining to USP11 and RNF4. USP11 was found to be significantly enriched after FLAG-IP from the RNF4-FLAG stable cell line, with 0/0/0 USP11 MS/MS counts in the parental line versus 8/14/11 USP11 MS/MS counts in the RNF4-FLAG line, respectively. USP11 was found to be enriched after RNF4-FLAG IP with a Label-Free Quantification (LFQ) Log2 ratio of over 5.

(B) MCF7 cell lines expressing RNF4-FLAG and parental controls were treated with methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), lysed, and FLAG-IP was performed. Total lysates and IP fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting against USP11 to confirm the co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous USP11 with RNF4-FLAG. Immunoblotting for RNF4 was performed as an immunoprecipitation control.

(C) Ponceau-S loading control for section B. Additionally, total lysates and IP fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting against SUMO-2/3 to investigate potential co-immunoprecipitation of SUMO-2/3 with RNF4 through its SUMO-interacting motifs (SIMs).

(D) Investigation of V5-USP11 and FLAG-RNF4 co-localization. Both proteins were transiently expressed in U2-OS cells, prior to the cells being fixed, immunostained and analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Differential interference contrast (DIC) was used to visualize the nuclei and nucleoli. Scale bars represent 10 μm.

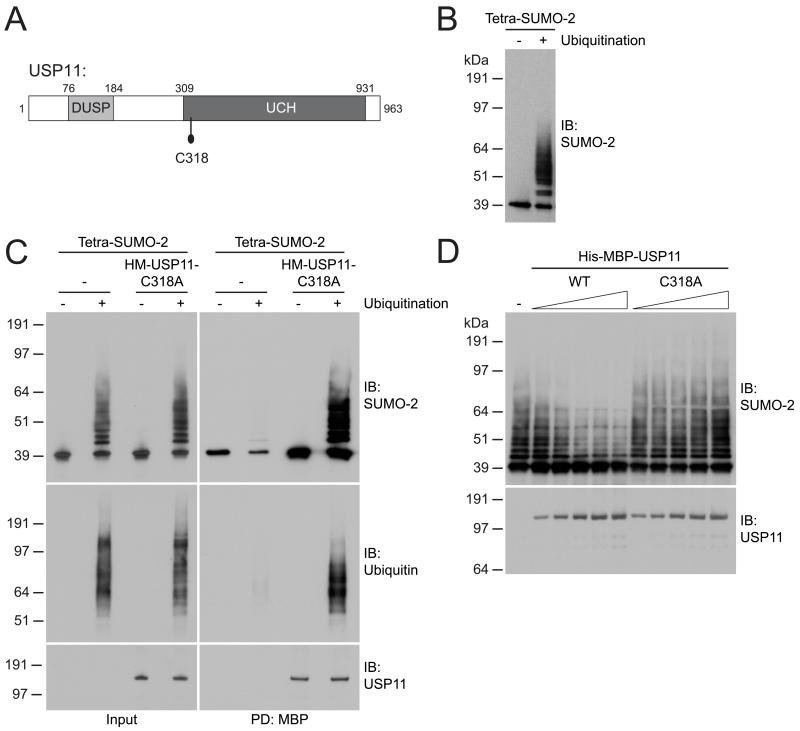

Figure 3. USP11 deubiquitinates hybrid SUMO-2-ubiquitin chains in vitro.

(A) Cartoon depicting USP11. USP11 harbors a Domain present in Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases (DUSP) and an Ubiquitin Carboxyl-terminal Hydrolase domain (UCH). The location of the catalytic cysteine (C318) is indicated.

(B) His-tetra-SUMO-2 proteins were in vitro ubiquitinated using GST-RNF4.

(C) His-tetra-SUMO-2 and hybrid SUMO-ubiquitin chains were incubated in the absence or presence of catalytic inactive His6-MBP-USP11, prior to enrichment of His6-MBP-USP11 by MBP-pulldown. Input and pulldown samples were analyzed by immunoblotting for SUMO-2/3 and ubiquitin, and input levels and pulldown efficiency were analyzed by immunoblotting for USP11.

(D) Hybrid SUMO-ubiquitin chains were incubated with increasing concentrations of His6-MBP-USP11 wild-type (WT) or a catalytic inactive mutant (C318A). Hybrid chains were analyzed by immunoblotting against SUMO-2/3 and His6-MBP-USP11 input levels were analyzed by immunoblotting for USP11.

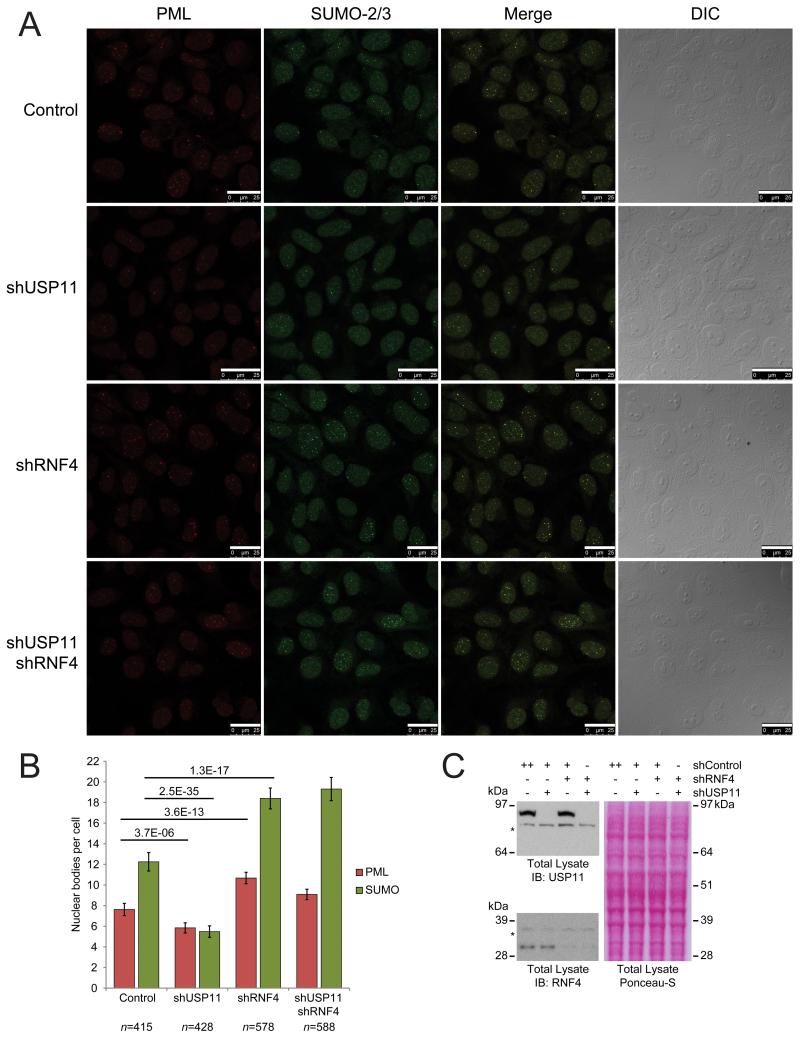

Figure 4. USP11 stabilizes nuclear bodies, counteracting the destabilizing effect of RNF4.

(A) U2-OS cells were depleted for endogenous USP11, RNF4, or both, by infection with lentiviral knockdown constructs. As a control, an untargeted lentiviral knockdown construct was used. Following depletion of proteins, cells were fixed, immunostained and subsequently analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy for the presence of PML and SUMO-2/3 positive nuclear bodies. Images represent maximum projections of Z-stacks. Differential interference contrast (DIC) was used to visualize the nuclei. Depletion of USP11 destabilizes PML and SUMO-2/3 nuclear bodies, whereas depletion of RNF4 stabilizes PML and SUMO-2/3 nuclear bodies. Scale bars are 25 μm.

(B) Multiple maximum projected fields of cells were recorded as in section A. Cells were counted, and PML and SUMO-2/3 nuclear bodies were quantified per cell. At least 400 cells were counted for each experimental condition, with the exact number of cells shown below each experiment. Error bars represent 2× SEM. Student’s t-test p-values are indicated over their respective experiments.

(C) Total cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting to confirm the depletion of USP11 and RNF4. Ponceau-S staining of the membrane was included as a loading control.

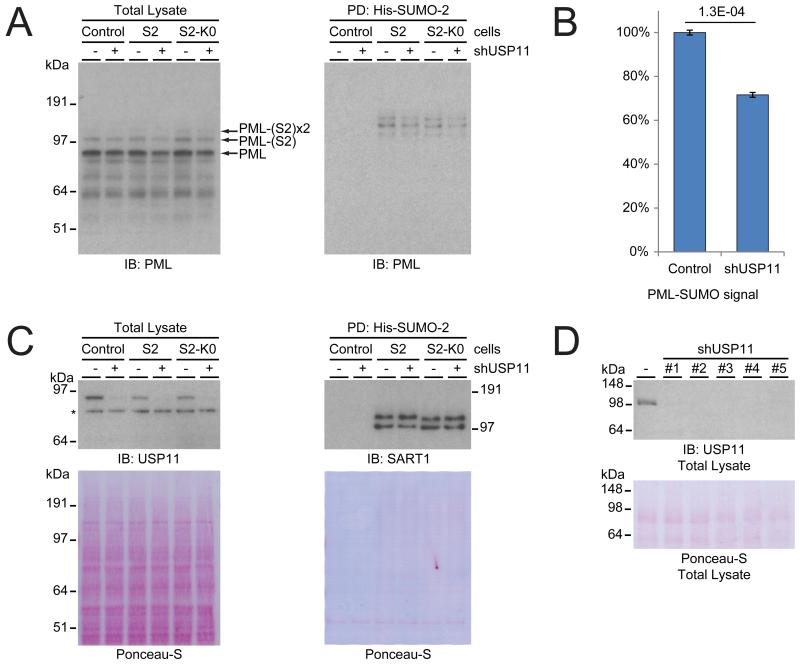

Figure 5. USP11 stabilizes SUMOylated PML.

(A) HeLa cells expressing wild-type His-tagged SUMO-2 or lysine-deficient SUMO-2, and parental HeLa cells were either depleted for USP11 by infection with lentiviral knockdown constructs, or treated with an untargeted knockdown construct. After depletion of USP11, cells were lysed, and His-pulldown was performed to enrich SUMOylated proteins. Total lysates and SUMO-enriched fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting using an antibody against PML. Unmodified and SUMO-modified PML are indicated for the total lysate blot.

(B) Quantification of the PML-SUMO signal in the total lysate and SUMO-enriched lanes corresponding to the His-SUMO cell lines, comparing the PML-SUMO signal in the control versus USP11-depleted cells. Error bars represent standard deviation. Student’s t-test p-value is indicated.

(C) Total lysates from section A were analyzed by immunoblotting with an antibody against USP11 as a knockdown control, and Ponceau-S staining was used as a loading control. SUMO-enriched fractions from section A were analyzed by immunoblotting with an antibody against SART1 as a SUMO-level control, and Ponceau-S staining was used as a pulldown control. Note that SART1 modified with lysine-deficient SUMO has slightly different migration behavior due to lysine-to-arginine substitutions.

(D) HeLa cells were depleted of USP11 by infection with five different lentiviral knockdown constructs, or treated with an untargeted knockdown construct. Subsequently, cells were lysed, and total lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using an antibody against USP11. All five viruses were found to be efficient, and a low-concentration mixture of all viruses was used for all other USP11 depletion experiments to provide an effective knockdown. Note that this experiment was performed using an acrylamide gel resolved in TRIS-glycine buffer, which accounts for a slightly different observed migration size of USP11.

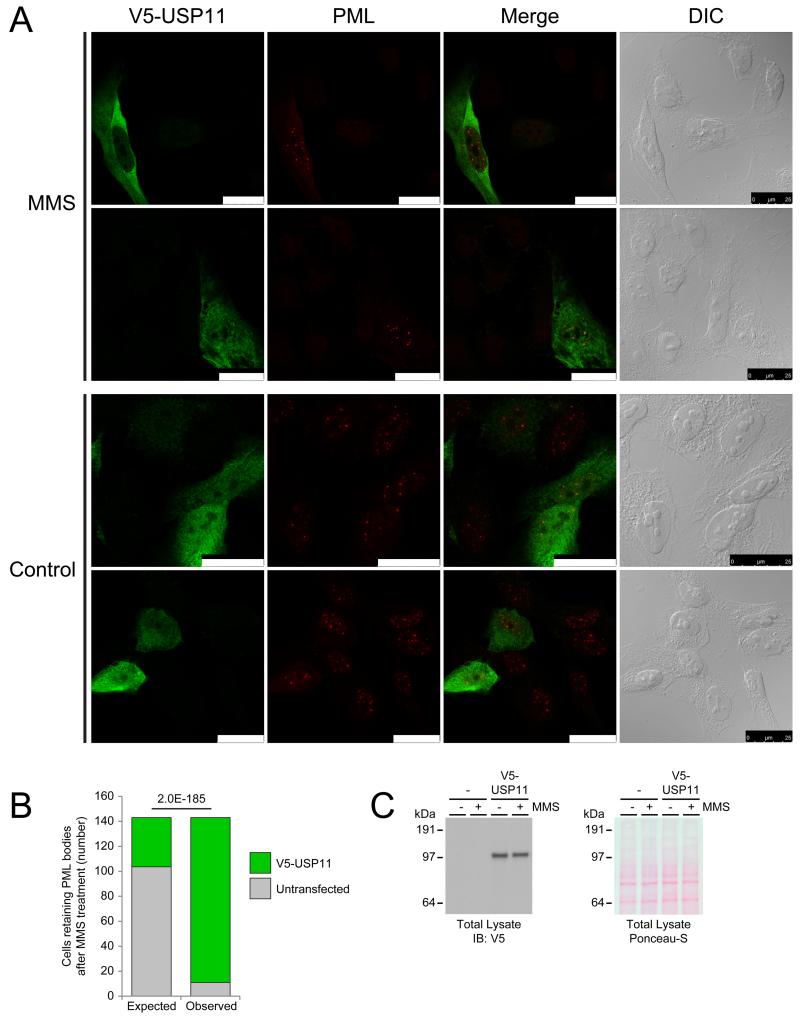

Figure 6. USP11 counteracts RNF4-mediated degradation of nuclear bodies in response to treatment the DNA damaging agent methyl methanesulfonate.

(A) U2-OS cells were transfected with a construct encoding V5-USP11, and subsequently mock treated or treated with 0.02% MMS for 135 minutes. Following treatment, cells were fixed, and immunostained. Confocal fluorescence microscopy was used to visualize V5-USP11 (green) and PML (red). Differential interference contrast (DIC) was used to visualize the nuclei. Scale bars are 25 μm.

(B) As section A, except 143 cells that retained PML bodies after MMS treatment were investigated for the presence of V5-USP11. V5-USP11 transfection efficiency of all cells was 27.6%. The randomly expected number of cells expressing V5-USP11 retaining PML bodies was 39 (27.6%), versus the experimentally observed amount of 132 (92.3%). This difference was significant with a P value of 2.0E-185 by Pearson’s Chi-squared test.

(C) Immunoblot analysis of total lysates corresponding to section A. V5 antibody was used to confirm exogenous expression of V5-USP11, and Ponceau-S staining was used as a loading control.

LC-MS/MS analysis and data processing

Experiments were performed in triplicate. The analysis of in-gel digested samples was performed as described previously (45). Raw data were processed using MaxQuant (46,47). RNF4-FLAG interactors were investigated through Label-Free Quantification (LFQ) as well as MS/MS spectral counting.

Microscopy

Cells were seeded on glass coverslips, and fixed 24 hours later for 10 minutes in 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PHEM buffer (60 mM PIPES, 25 mM HEPES, 10 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2 pH 6.9) at 37 °C. After washing with PBS, cells were permeated with 0.1% Triton-X100 for 10 minutes, washed with PBST, and blocked using TNB (100 mM TRIS pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Blocking Reagent (Roche)) for 30 minutes. Cells were incubated with primary antibody as indicated, in TNB for one hour. Cells were washed five times with PBST, and incubated with secondary antibodies (Goat α Ms Alexa 488 and Goat α Rb Alexa 594 (Life Technologies)) in TNB for one hour. Next, cells were washed five times with PBST and dehydrated using alcohol, prior to fixing them in DAPI solution (Citifluor). Images were recorded on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope system using 488 nm and 561 nm lasers for excitation, a 63× lens for magnification, and were analyzed with Leica confocal software. For quantification of PML bodies, groups of cells were recorded in similar-sized fields using Z-stacking with steps of 0.5 μm to acquire 10 images ranging from the bottom to the top of the cells. Images were maximum projected, individual cells were localized and PML bodies were counted using in-house customized Stacks software (48).

RESULTS

Purification of FLAG-tagged Ring Finger Protein 4 (RNF4) from MCF7 cells

SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase RNF4 specifically recognizes targets that are modified by multiple SUMOs, through its SUMOylation Interacting Motifs (SIMs) (15,49). Subsequently, these SUMOylated targets are ubiquitinated by RNF4, which can lead to the degradation of these proteins by the proteasome (26,50,51). Poly-SUMOylated targets of RNF4 have been identified employing a trap consisting of the RNF4 SIM-domain (52).

We were interested in identifying SIM-independent RNF4 interactors. In order to facilitate this study, an MCF7 cell line stably expressing C-terminally FLAG-tagged RNF4 was generated (Figure 1A). RNF4-FLAG was located correctly and exclusively in the nucleus (Figure 1B). Some of the RNF4-FLAG localized into nuclear bodies, which likely correspond to PML nuclear bodies. The non-fused and co-expressing Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) was included as a control.

We performed FLAG-immunoprecipitation (IP), and found that RNF4-FLAG is very efficiently purified (Figures 1C and 1D). Finally, Coomassie analysis of the purified RNF4-FLAG and its potential interactors revealed a singular and very clear band corresponding to RNF4-FLAG, indicative of a clean and highly stringent purification of RNF4-FLAG (Figure 1D).

Identification of Ubiquitin-Specific Protease 11 (USP11) co-purifying with RNF4

The RNF4-FLAG IP was performed in biological triplicate, and the gel lanes were cut in five separate slices and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Strikingly, we did not detect free or conjugated forms of SUMO in the IP, proving that our lysis and IP conditions were sufficiently harsh to yield a clean IP, yet mild enough to allow the highly robust SENPs to cleave SUMO off virtually all proteins. Unsurprisingly, RNF4 itself was detected as the highest enriched protein after RNF4-FLAG IP. Interestingly, we identified the ubiquitin specific protease 11 (USP11) as an RNF4 interactor (Figure 2A). USP11 was found to be enriched over the control with a Log2 ratio of 5.1, and eleven MS/MS spectral identifications matching USP11 were made in the RNF4-FLAG IP as opposed to zero in the control IP (Figure 2A and Table S1).

After identifying USP11 as a putative interactor of RNF4 through mass spectrometry analysis, the experiment was repeated, and samples were analyzed by immunoblotting (Figure 2B). Additionally, a potential effect of the DNA damaging agent methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) on the interaction between RNF4 and USP11 was investigated, as MMS is known to cause disassembly of the nuclear bodies harboring RNF4 (53). After RNF4-FLAG IP, we found that endogenous USP11 interacted specifically with RNF4, with no signal detectable in the control (Figure 2B). There was no indication that the interaction between RNF4 and USP11 is disrupted upon treating the cells with MMS. A small decrease in USP11 levels was observed after DNA damage, indicative of its function in the DNA damage response. In agreement with the mass spectrometry findings, free SUMO was detected only in the total lysates, a direct result of the SENPs removing all SUMO from target proteins following lysis, indicating that the interaction between USP11 and RNF4 is SUMOylation-independent (Figure 2C). Finally, we investigated co-localization of USP11 and RNF4 through confocal microscopy. Whereas RNF4 was observed to be exclusively nuclear and USP11 was localized all throughout the cell, both proteins had a significant presence in the nucleus, but outside of the nucleoli. This suggests that a fraction of these proteins resides in close proximity to each other in the nucleus (Figure 2D).

USP11 deubiquitinates SUMO-2-ubiquitin hybrid chains in vitro

To test whether USP11 (Figure 3A) can counteract RNF4 in vitro, a hybrid SUMO-2-ubiquitin polymer was generated as a potential USP11 substrate, using a recombinant linear SUMO-2 polymer, composed of four SUMO moieties which was ubiquitinated in vitro by RNF4 (Figure 3B)(26). We investigated the ability of catalytically inactive USP11 mutant (C318A) to bind to hybrid SUMO-2-ubiquitin chains through a binding assay, and USP11 was observed to bind to these hybrid chains with very high efficiency, regardless of whether singular or multiple ubiquitin moieties were coupled to the tetra-SUMO-2 (Figure 3C). Next, we performed a deubiquitination assay, and observed that wild-type USP11 was able to deubiquitinate SUMO-2-ubiquitin hybrid chains while the catalytically inactive USP11 mutant had no effect (Figure 3D). We conclude that USP11 could efficiently bind to and deubiquitinate hybrid SUMO-2-ubiquitin polymers generated by RNF4 in vitro.

USP11 counterbalances RNF4 and controls stability of nuclear bodies

Since RNF4 is known to ubiquitinate SUMOylated PML, which in turn leads to degradation of PML and the destabilization of nuclear bodies (26), we set out to study the role of endogenous USP11 in nuclear body integrity. Lentiviral shRNA-mediated depletion of endogenous USP11, RNF4, or both proteins was performed, prior to analysis of the cells by confocal microscopy (Figure 4A). Although SUMO and PML co-localize in nuclear bodies, the overlap is partial. Strikingly, after depletion of endogenous USP11, a significant reduction in nuclear bodies was observed (Figure 4A). Accordingly, depletion of endogenous RNF4 led to significant increases in nuclear bodies. Ultimately, a ~25% reduction in PML bodies and a ~50% reduction in SUMO bodies was found upon USP11 depletion, and a ~35% increase in PML bodies and a ~50% increase in SUMO bodies upon RNF4 depletion (Figure 4B). Efficient depletion of both USP11 and RNF4 was confirmed (Figure 4C). Similar results were obtained in MCF7 cells (data not shown).

Interestingly, when combining depletion of both USP11 and RNF4, a somewhat intermediate phenotype was observed (Figures 4A and 4B). Whereas the increase in PML bodies resulting from depletion of RNF4 was modestly countered by additional knockdown of USP11, there was no clear effect on SUMO positive nuclear bodies. Thus, it is likely that USP11 acts downstream of RNF4, providing a counterbalancing mechanism to the ubiquitin ligase activity of RNF4 to establish an important equilibrium, which is characteristic for ubiquitin signaling and a general phenomenon for post-translational modifications.

USP11 modulates the level of SUMOylated PML

In addition to cellular analysis by microcopy, the SUMOylation state of the PML protein after depletion of endogenous USP11 in HeLa cells was investigated. In order to facilitate the experiment, HeLa cell lines stably expressing His-tagged SUMO-2 were used to allow for efficient purification of SUMOylated proteins. Additionally, a similar cell line stably expressing lysine-deficient His-tagged SUMO-2 was used in order to investigate a potential effect of inhibited SUMO-2 chain formation on the SUMOylation of PML, and any cumulative result in combination with USP11 depletion.

Similar to observations made with counting PML bodies, a significant decrease in SUMOylated PML was found after depletion of USP11, in both total lysate and SUMO-enriched fractions (Figure 5A). We noted a very slight decrease in total PML levels after USP11 depletion, which could be a direct result of SUMOylated and subsequently ubiquitinated PML being degraded more rapidly. The decrease in SUMOylated PML signal was found to be ~30% (Figure 5B); highly similar to the ~25% decrease in PML nuclear bodies observed through confocal microscopy (Figure 4B). We observed a somewhat lower SUMOylation efficiency of PML modification by lysine-deficient SUMO. However, USP11 depletion still resulted in a consistent decrease of PML SUMOylation. Efficient depletion of endogenous USP11 was validated (Figures 5C and 5D), and additionally the well-known SUMOylation target protein SART1 (39) was investigated as a control (Figure 5C). The SUMOylation state of SART1 was virtually identical regardless of USP11 depletion, indicating that the effect on PML SUMOylation was specific. Note that the slight shift in migration behavior visible between the wild-type SUMO-2 and the lysine-deficient SUMO-2 is a direct effect of lysine-to-arginine substitutions.

USP11 prevents the disintegration of nuclear bodies in response to DNA damage

In order to investigate the extent of protection USP11 offers to SUMOylated PML and their associated nuclear bodies, an overexpression experiment was performed where U2-OS cells were transfected with V5-tagged USP11. Subsequently, the cells were treated with MMS, which is known to cause degradation of SUMOylated PML and instigate a disassembly of nuclear bodies (53-55). The treatment dose and time chosen for the experiment was sufficient to completely abolish all PML nuclear bodies. Confocal fluorescence microscopy was used to investigate mock treated and MMS treated cells (Figure 6A).

In untreated cells, nuclear bodies were observed to be distributed fairly equally between cells expressing V5-USP11 and untransfected cells. However, after MMS treatment virtually all untransfected cells completely lost their nuclear bodies, whereas some cells expressing V5-USP11 were able to retain their PML bodies (Figure 6A). We quantified over 100 cells that retained PML bodies, and found the large majority (~92%) to express V5-USP11, even though only ~28% of all cells were transfected (Figure 6B). Equal expression of V5-USP11 was confirmed by immunoblotting (Figure 6C). Thus, an increased presence of USP11 within the cell was able to counteract the ubiquitination and degradation of SUMOylated PML, and could counteract the disassembly of nuclear bodies in response to DNA damage (Figure 7).

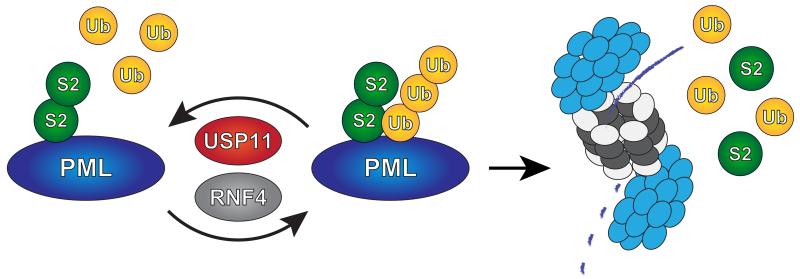

Figure 7. Model.

USP11 counteracts RNF4 by deubiquitinating SUMO-ubiquitin hybrid chains generated by RNF4, preventing degradation of PML by the proteasome.

DISCUSSION

Using an unbiased proteomic approach, we have identified USP11 as a ubiquitin protease to co-purify with RNF4, with the ability to process hybrid SUMO-ubiquitin polymers. This USP family member contains a DUSP domain with the ability to bind ubiquitin, as well as a catalytic UCH domain. We found that USP11 was able to deubiquitinate hybrid SUMO-ubiquitin chains via its catalytically active C-terminal hydrolase domain. Further, USP11 possessed the ability to counteract RNF4 during regular growth conditions. Depletion of USP11 led to a decrease in the amount of nuclear bodies, whereas depletion of RNF4 led to the exact opposite. Furthermore, we found that exogenous USP11 could counteract RNF4’s role in the DNA damage response by blocking the dissociation of PML bodies in response to MMS. The dissociation of PML bodies enables proper progression of the DNA damage response (56) and induction of apoptosis (57,58).

USP11 was previously found to be involved in repair of double-stranded breaks by homologous recombination, where knockdown of USP11 resulted in spontaneous activation of DNA damage response pathways, rendering cells hypersensitive to PARP inhibition, ionizing radiation and other genotoxic stresses (59). USP11 has been shown to interact with BRCA2, a key component of the homologous recombination pathway, where BRCA2 was shown to be a target for deubiquitination by USP11 (60). Treatment of cells by Mitomycin C led to degradation of BRCA2, which could be countered by USP11 overexpression, and inhibition of USP11’s function increased cellular sensitivity to Mitomycin C (60). Similar to USP11, RNF4 is also required for homologous recombination (30-32), indicating that balanced ubiquitination and deubiquitination of SUMOylated proteins is required for efficient DNA repair via homologous recombination.

The function of USP11 in the DNA damage response makes it a potential clinical target, as inhibition of USP11 would render cancer cells susceptible to apoptosis, especially combined with other treatments such as PARP inhibition. Accordingly, some progress has been made on compounds targeting and counteracting USP11, displaying the ability to inhibit growth of pancreatic cancer cells (61).

In a similar screen for interaction partners of varying deubiquitinating enzymes performed by Sowa et al. (62), RNF4 was not discovered as an interaction partner of USP11. However, different buffer conditions, epitope tags, and cell lines were used, which could account for variations in interactomes between the two screens.

More recently, USP11 was found to interact directly with PML (63). Contrarily, we found USP11 to co-purify with the SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase RNF4. Wu et al. further reported that USP11 depletion leads to a decrease in PML bodies, which is consistent with our findings. USP11 overexpression was shown by Wu et al. to be able to counteract arsenic-induced degradation of PML, but a role in the DNA damage response was not investigated by these authors. USP11 was found to be transcriptionally repressed in human glioma, with upregulation of the Hey1/Notch pathway resulting in downregulation of USP11 and correspondingly PML (63). Interestingly, this was found to increase cellular malignancy as well as potentiate survival and resistance to therapeutic treatment, which is opposing findings where antagonizing USP11 leads to inhibition of pancreatic cancer (61).

In summary, we propose that USP11 keeps RNF4 in check through its ability to reverse RNF4’s ubiquitination of SUMOylated proteins (Figure 7). We have thus identified a ubiquitin protease which balances the activity of a SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Drs. R. van Driel, R.T. Hay, R.C. Hoeben, L. Fradkin, L. Zhong and P. ten Dijke for providing critical reagents, to M. Verlaan – de Vries for technical assistance and to Dr. A. Zemla for providing artwork. This work was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) (A.C.O.V.), ZonMW (A.C.O.V.), the European Research Council (A.C.O.V) and the research career program FSS Sapere Aude (J.V.O.) from the Danish Research Council. The NNF Center for Protein Research is supported by a generous donation from the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flotho A, Melchior F. Sumoylation: a regulatory protein modification in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013;82:357–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061909-093311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hickey CM, Wilson NR, Hochstrasser M. Function and regulation of SUMO proteases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:755–766. doi: 10.1038/nrm3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hay RT. SUMO-specific proteases: a twist in the tail. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nacerddine K, Lehembre F, Bhaumik M, Artus J, Cohen-Tannoudji M, Babinet C, Pandolfi PP, Dejean A. The SUMO pathway is essential for nuclear integrity and chromosome segregation in mice. Dev. Cell. 2005;9:769–779. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker J, Barysch SV, Karaca S, Dittner C, Hsiao HH, Berriel DM, Herzig S, Urlaub H, Melchior F. Detecting endogenous SUMO targets in mammalian cells and tissues. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:525–531. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golebiowski F, Matic I, Tatham MH, Cole C, Yin Y, Nakamura A, Cox J, Barton GJ, Mann M, Hay RT. System-wide changes to SUMO modifications in response to heat shock. Sci. Signal. 2009;2:ra24. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vertegaal AC. Uncovering ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like signaling networks. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:7923–7940. doi: 10.1021/cr200187e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matic I, Schimmel J, Hendriks IA, van Santen MA, van de Rijke F, van Dam H, Gnad F, Mann M, Vertegaal AC. Site-specific identification of SUMO-2 targets in cells reveals an inverted SUMOylation motif and a hydrophobic cluster SUMOylation motif. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:641–652. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez MS, Dargemont C, Hay RT. SUMO-1 conjugation in vivo requires both a consensus modification motif and nuclear targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:12654–12659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernier-Villamor V, Sampson DA, Matunis MJ, Lima CD. Structural basis for E2-mediated SUMO conjugation revealed by a complex between ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc9 and RanGAP1. Cell. 2002;108:345–356. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00630-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tatham MH, Jaffray E, Vaughan OA, Desterro JM, Botting CH, Naismith JH, Hay RT. Polymeric chains of SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 are conjugated to protein substrates by SAE1/SAE2 and Ubc9. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:35368–35374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104214200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matic I, van Hagen M, Schimmel J, Macek B, Ogg SC, Tatham MH, Hay RT, Lamond AI, Mann M, Vertegaal AC. In vivo identification of human small ubiquitin-like modifier polymerization sites by high accuracy mass spectrometry and an in vitro to in vivo strategy. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:132–144. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700173-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vertegaal AC. Small ubiquitin-related modifiers in chains. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007;35:1422–1423. doi: 10.1042/BST0351422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vertegaal AC. SUMO chains: polymeric signals. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2010;38:46–49. doi: 10.1042/BST0380046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerscher O. SUMO junction-what’s your function? New insights through SUMO-interacting motifs. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:550–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danielsen JR, Povlsen LK, Villumsen BH, Streicher W, Nilsson J, Wikstrom M, Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N. DNA damage-inducible SUMOylation of HERC2 promotes RNF8 binding via a novel SUMO-binding Zinc finger. J. Cell Biol. 2012;197:179–187. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunter T, Sun H. Crosstalk between the SUMO and ubiquitin pathways. Ernst. Schering. Found. Symp. Proc. 2008:1–16. doi: 10.1007/2789_2008_098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulrich HD. Mutual interactions between the SUMO and ubiquitin systems: a plea of no contest. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:525–532. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desterro JM, Rodriguez MS, Hay RT. SUMO-1 modification of IkappaBalpha inhibits NF-kappaB activation. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:233–239. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang TT, Wuerzberger-Davis SM, Wu ZH, Miyamoto S. Sequential modification of NEMO/IKKgamma by SUMO-1 and ubiquitin mediates NF-kappaB activation by genotoxic stress. Cell. 2003;115:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00895-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schimmel J, Larsen KM, Matic I, van Hagen M, Cox J, Mann M, Andersen JS, Vertegaal AC. The ubiquitin-proteasome system is a key component of the SUMO-2/3 cycle. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:2107–2122. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800025-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tatham MH, Matic I, Mann M, Hay RT. Comparative proteomic analysis identifies a role for SUMO in protein quality control. Sci. Signal. 2011;4:rs4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prudden J, Pebernard S, Raffa G, Slavin DA, Perry JJ, Tainer JA, McGowan CH, Boddy MN. SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases in genome stability. EMBO J. 2007;26:4089–4101. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun H, Leverson JD, Hunter T. Conserved function of RNF4 family proteins in eukaryotes: targeting a ubiquitin ligase to SUMOylated proteins. EMBO J. 2007;26:4102–4112. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uzunova K, Gottsche K, Miteva M, Weisshaar SR, Glanemann C, Schnellhardt M, Niessen M, Scheel H, Hofmann K, Johnson ES, Praefcke GJ, Dohmen RJ. Ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic control of SUMO conjugates. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:34167–34175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tatham MH, Geoffroy MC, Shen L, Plechanovova A, Hattersley N, Jaffray EG, Palvimo JJ, Hay RT. RNF4 is a poly-SUMO-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase required for arsenic-induced PML degradation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:538–546. doi: 10.1038/ncb1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun H, Hunter T. Poly-small ubiquitin-like modifier (PolySUMO)-binding proteins identified through a string search. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:42071–42083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.410985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poulsen SL, Hansen RK, Wagner SA, van Cuijk L, van Belle GJ, Streicher W, Wikstrom M, Choudhary C, Houtsmuller AB, Marteijn JA, Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N. RNF111/Arkadia is a SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase that facilitates the DNA damage response. J. Cell Biol. 2013;201:797–807. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201212075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heideker J, Perry JJ, Boddy MN. Genome stability roles of SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8:517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yin Y, Seifert A, Chua JS, Maure JF, Golebiowski F, Hay RT. SUMO-targeted ubiquitin E3 ligase RNF4 is required for the response of human cells to DNA damage. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1196–1208. doi: 10.1101/gad.189274.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galanty Y, Belotserkovskaya R, Coates J, Jackson SP. RNF4, a SUMO-targeted ubiquitin E3 ligase, promotes DNA double-strand break repair. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1179–1195. doi: 10.1101/gad.188284.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vyas R, Kumar R, Clermont F, Helfricht A, Kalev P, Sotiropoulou P, Hendriks IA, Radaelli E, Hochepied T, Blanpain C, Sablina A, van Attikum H, Olsen JV, Jochemsen AG, Vertegaal AC, Marine JC. RNF4 is required for DNA double-strand break repair in vivo. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:490–502. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo K, Zhang H, Wang L, Yuan J, Lou Z. Sumoylation of MDC1 is important for proper DNA damage response. EMBO J. 2012;31:3008–3019. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Hagen M, Overmeer RM, Abolvardi SS, Vertegaal AC. RNF4 and VHL regulate the proteasomal degradation of SUMO-conjugated Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-2alpha. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1922–1931. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu XV, Rodrigues TM, Tao H, Baker RK, Miraglia L, Orth AP, Lyons GE, Schultz PG, Wu X. Identification of RING finger protein 4 (RNF4) as a modulator of DNA demethylation through a functional genomics screen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:15087–15092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009025107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nijman SM, Luna-Vargas MP, Velds A, Brummelkamp TR, Dirac AM, Sixma TK, Bernards R. A genomic and functional inventory of deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell. 2005;123:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reyes-Turcu FE, Ventii KH, Wilkinson KD. Regulation and cellular roles of ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinating enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:363–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.082307.091526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hendriks IA, D’Souza RC, Yang B, Verlaan-de Vries M, Mann M, Vertegaal AC. Uncovering global SUMOylation signaling networks in a site-specific manner. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:927–936. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schimmel J, Balog CI, Deelder AM, Drijfhout JW, Hensbergen PJ, Vertegaal AC. Positively charged amino acids flanking a sumoylation consensus tetramer on the 110kDa tri-snRNP component SART1 enhance sumoylation efficiency. J. Proteomics. 2010;73:1523–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stuurman N, de Graaf A, Floore A, Josso A, Humbel B, de Jong L, van Driel R. A monoclonal antibody recognizing nuclear matrix-associated nuclear bodies. J. Cell Sci. 1992;101(Pt 4):773–784. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101.4.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vertegaal AC, Ogg SC, Jaffray E, Rodriguez MS, Hay RT, Andersen JS, Mann M, Lamond AI. A proteomic study of SUMO-2 target proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:33791–33798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vertegaal AC, Andersen JS, Ogg SC, Hay RT, Mann M, Lamond AI. Distinct and overlapping sets of SUMO-1 and SUMO-2 target proteins revealed by quantitative proteomics. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:2298–2310. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600212-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shevchenko A, Tomas H, Havlis J, Olsen JV, Mann M. In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:2856–2860. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rappsilber J, Mann M, Ishihama Y. Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:1896–1906. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schimmel J, Eifler K, Sigurethsson JO, Cuijpers SA, Hendriks IA, Verlaan-de Vries M, Kelstrup CD, Francavilla C, Medema RH, Olsen JV, Vertegaal AC. Uncovering SUMOylation Dynamics during Cell-Cycle Progression Reveals FoxM1 as a Key Mitotic SUMO Target Protein. Mol. Cell. 2014;53:1053–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cox J, Neuhauser N, Michalski A, Scheltema RA, Olsen JV, Mann M. Andromeda: a peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. J. Proteome. Res. 2011;10:1794–1805. doi: 10.1021/pr101065j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smeenk G, Wiegant WW, Vrolijk H, Solari AP, Pastink A, van Attikum H. The NuRD chromatin-remodeling complex regulates signaling and repair of DNA damage. J. Cell Biol. 2010;190:741–749. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201001048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin DY, Huang YS, Jeng JC, Kuo HY, Chang CC, Chao TT, Ho CC, Chen YC, Lin TP, Fang HI, Hung CC, Suen CS, Hwang MJ, Chang KS, Maul GG, Shih HM. Role of SUMO-interacting motif in Daxx SUMO modification, subnuclear localization, and repression of sumoylated transcription factors. Mol. Cell. 2006;24:341–354. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weisshaar SR, Keusekotten K, Krause A, Horst C, Springer HM, Gottsche K, Dohmen RJ, Praefcke GJ. Arsenic trioxide stimulates SUMO-2/3 modification leading to RNF4-dependent proteolytic targeting of PML. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3174–3178. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lallemand-Breitenbach V, Jeanne M, Benhenda S, Nasr R, Lei M, Peres L, Zhou J, Zhu J, Raught B, De The H. Arsenic degrades PML or PML-RARalpha through a SUMO-triggered RNF4/ubiquitin-mediated pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:547–555. doi: 10.1038/ncb1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bruderer R, Tatham MH, Plechanovova A, Matic I, Garg AK, Hay RT. Purification and identification of endogenous polySUMO conjugates. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:142–148. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conlan LA, McNees CJ, Heierhorst J. Proteasome-dependent dispersal of PML nuclear bodies in response to alkylating DNA damage. Oncogene. 2004;23:307–310. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brouwer AK, Schimmel J, Wiegant JC, Vertegaal AC, Tanke HJ, Dirks RW. Telomeric DNA mediates de novo PML body formation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:4804–4815. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-04-0309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hendriks IA, Treffers LW, Verlaan-de Vries M, Olsen JV, Vertegaal AC. SUMO-2 Orchestrates Chromatin Modifiers in Response to DNA Damage. Cell Rep. 2015;10:1778–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dellaire G, Bazett-Jones DP. PML nuclear bodies: dynamic sensors of DNA damage and cellular stress. Bioessays. 2004;26:963–977. doi: 10.1002/bies.20089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo A, Salomoni P, Luo J, Shih A, Zhong S, Gu W, Pandolfi PP. The function of PML in p53-dependent apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:730–736. doi: 10.1038/35036365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang ZG, Ruggero D, Ronchetti S, Zhong S, Gaboli M, Rivi R, Pandolfi PP. PML is essential for multiple apoptotic pathways. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:266–272. doi: 10.1038/3073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wiltshire TD, Lovejoy CA, Wang T, Xia F, O’Connor MJ, Cortez D. Sensitivity to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibition identifies ubiquitin-specific peptidase 11 (USP11) as a regulator of DNA double-strand break repair. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:14565–14571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.104745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schoenfeld AR, Apgar S, Dolios G, Wang R, Aaronson SA. BRCA2 is ubiquitinated in vivo and interacts with USP11, a deubiquitinating enzyme that exhibits prosurvival function in the cellular response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:7444–7455. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7444-7455.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burkhart RA, Peng Y, Norris ZA, Tholey RM, Talbott VA, Liang Q, Ai Y, Miller K, Lal S, Cozzitorto JA, Witkiewicz AK, Yeo CJ, Gehrmann M, Napper A, Winter JM, Sawicki JA, Zhuang Z, Brody JR. Mitoxantrone Targets Human Ubiquitin-Specific Peptidase 11 (USP11) and Is a Potent Inhibitor of Pancreatic Cancer Cell Survival. Mol. Cancer Res. 2013;11:901–911. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sowa ME, Bennett EJ, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Defining the human deubiquitinating enzyme interaction landscape. Cell. 2009;138:389–403. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu HC, Lin YC, Liu CH, Chung HC, Wang YT, Lin YW, Ma HI, Tu PH, Lawler SE, Chen RH. USP11 regulates PML stability to control Notch-induced malignancy in brain tumours. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3214. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.