SUMMARY

All plants are inhabited internally by diverse microbial communities comprising bacterial, archaeal, fungal, and protistic taxa. These microorganisms showing endophytic lifestyles play crucial roles in plant development, growth, fitness, and diversification. The increasing awareness of and information on endophytes provide insight into the complexity of the plant microbiome. The nature of plant-endophyte interactions ranges from mutualism to pathogenicity. This depends on a set of abiotic and biotic factors, including the genotypes of plants and microbes, environmental conditions, and the dynamic network of interactions within the plant biome. In this review, we address the concept of endophytism, considering the latest insights into evolution, plant ecosystem functioning, and multipartite interactions.

INTRODUCTION

Endophytes are microorganisms that spend at least parts of their life cycle inside plants. Endophyte definitions have changed in the past years and expectedly will evolve further over the coming years. The term “endophyte” has commonly been used for fungi living inside plants, but later researchers realized that interior parts of plants could be colonized by bacteria as well (1, 2). Plants do not live alone as single entities but closely associate with the microorganisms present in their neighborhood, and especially with those living internally. The emergence of the concept of the “plant microbiome,” i.e., the collective genomes of microorganisms living in association with plants, has led to new ideas on the evolution of plants where selective forces do not act merely on the plant genome itself but rather on the whole plant, including its associated microbial community. Lamarckian concepts of acquired heritable traits may be explained via the hologenome concept by vertical transmission of valuable traits provided by endophytes to plants (3).

The most common definition of endophytes is derived from the practical description given in 1997 by Hallmann and coauthors (2), who stated that endophytes are “…those (bacteria) that can be isolated from surface-disinfested plant tissue or extracted from within the plant, and that do not visibly harm the plant.” This definition has been valid for cultivable species in most laboratories in the world over the past 2 decades. However, due to the suspected lack of adequate elimination of nucleic acids after disinfection of plant surfaces, this definition appeared to be less suitable for noncultured species upon the introduction of molecular detection techniques in endophyte research (4).

Conceptual aspects related to the nature of endophytes are under dispute. For instance, must plant pathogens be considered endophytes or not, even when they have lost their virulence (5)? Recently, a typical bacterial group of endophytes beneficial to plants, the group of fluorescent pseudomonads, turned out to be detrimental to leatherleaf ferns under specific conditions (6). This indicates that potential plant mutualists can become deleterious for their hosts. Endophytes should not be harmful to the plant host, but what about harmfulness to other species, for instance, when particular bacteria that colonize internal compartments of plants are harmful to humans (7)?

The most common endophytes are typed as commensals, with unknown or yet unknown functions in plants, and less common ones are those shown to have positive (mutualistic) or negative (antagonistic) effects on plants (2). However, these properties are often tested in a single plant species or within groups of closely related plant genotypes, but rarely over a taxonomically wide spectrum of plant species. Also, the environmental conditions wherein plant-endophyte interactions are studied are often rather narrow. Furthermore, interactions between members of the endophyte community have rarely been investigated. A few studies demonstrated that interactions between taxonomically related microbial endophytes can shift whole populations inside the plant (8, 9). Bacterial and fungal endophytic communities are commonly investigated separately, but the interaction between both groups inside plants can become a fascinating new field in endophyte research (10).

Studies of plant-endophyte interactions are commonly based on controlled, optimized conditions for growth of host plants and seldom based on variable, field-realistic conditions. Effects ascribed to endophytes in healthy plants might change when host plants are grown under less favorable, or even stressful, conditions. In conclusion, our current understanding of endophytes is built on a rather small set of experimental conditions, and more varied experimental settings would be required for deeper insight into endophyte functioning. Because of this and the general preference to investigate microbial species that are relatively easy to cultivate, our knowledge of the ecology and interactions of endophytes in plants is still biased.

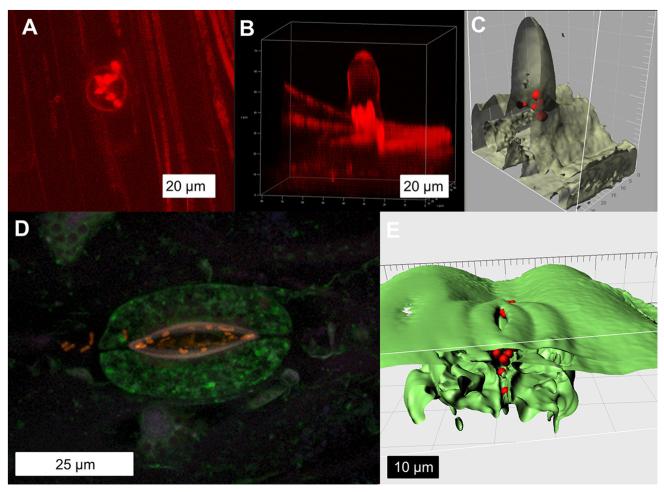

New developments in high-throughput technologies, such as next-generation sequencing, permit the investigation of complex microbiomes and will facilitate larger sample sizes and encourage deeper analyses of microbial communities (11). The new “omics” approaches are valuable tools for exploring, identifying, and characterizing the contributions of genetic and metabolic elements involved in the interactions between host plants and endophytes. For instance, metagenome sequencing has revealed important functions required for survival of bacterial endophytes inside plants (12), and metabolome analysis demonstrated the effects of beneficial endophytes on primary metabolites of plants (13). The combination of cultivation-independent and improved cultivation technologies will allow the exploration of hitherto uncultured groups living in association with plants (14, 15). In addition, the locations of endophytes in different plant compartments are disputable (16), but powerful image analyses can provide information about the exact colocalization within plant tissues and about physical contacts between different microbial groups (17–19). We are reaching a pivotal point in our perception of endophytes, and we expect that technical innovations in microbial detection will soon drastically change our concepts of endophytes as living entities colonizing internal plant compartments.

In this paper, we present a historical overview of the endophyte research leading to the current understanding of endophytes. The state of science for defined groups of endophytes is described in succeeding sections, based on the vast number of peer-reviewed publications on endophytes, which have been growing exponentially over the last 3 decades. Furthermore, we elaborate the expected impacts of novel technologies on endophyte research. It is our purpose to revisit current concepts on endophytes and to assess directions for new research on microbial endophytes based on the latest technological developments.

HISTORY OF ENDOPHYTE DEFINITIONS

The German botanist Heinrich Friedrich Link was the first to describe endophytes, in 1809 (20). At that time, they were termed “Entophytae” and were described as a distinct group of partly parasitic fungi living in plants. Since then, many definitions have evolved; for a long time, they mostly addressed pathogens or parasitic organisms, primarily fungi (21–23). Only Béchamp described so-called microzymas in plants, referring to microorganisms (24). Generally, in the 19th century, the belief was that healthy or normally growing plants are sterile and thus free of microorganisms (postulated by Pasteur; cited in reference 25). Nevertheless, Galippe reported the occurrence of bacteria and fungi in the interior of vegetable plants and postulated that these microorganisms derive from the soil environment and migrate into the plant, where they might play a beneficial role for the host plant (26, 27). Other studies in the late 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century confirmed the occurrence of beneficial microorganisms within plants (28, 29). Nevertheless, contrasting views on the existence of plant-beneficial endophytes prevailed at that time (28, 30–34). Nowadays, it is a well-established fact that plants are hosts for many types of microbial endophytes, including bacteria, fungi, archaea, and unicellular eukaryotes, such as algae (35) and amoebae (36).

An important discovery was made in 1888 by the Dutch microbiologist Martinus Willem Beijerinck, who isolated root nodule bacteria in pure culture from nodules of Leguminosae plants and showed that these isolates, which were later classified as Rhizobium leguminosarum (37), were capable of fixing atmospheric nitrogen (38). At the same time, Hermann Hellriegel and Hermann Wilfarth reported mineral N independence of leguminous plants, as well as the importance of symbiotic nitrogen fixation by rhizobia (39). Albert Bernhard Frank reported another important mutualistic symbiosis, i.e., the living together of unlike organisms (40), between roots of trees and underground fungi (41). He coined the term “mycorrhiza” to describe the interaction, which literally means “fungus roots.”

More recently, in 1991, Orlando Petrini defined endophytes as “all organisms inhabiting plant organs that at some time in their life cycle can colonize internal plant tissues without causing apparent harm to their host” (42). Since then, many definitions have been formulated (2, 43–48), essentially all pertaining to microorganisms which for all or part of their life cycle invade tissues of living plants without causing disease. Although this endophyte definition has been the basis of many studies and might be a pragmatic approach to distinguish between endophytes and pathogens, it has some drawbacks and raises some questions.

First, this definition is more suitable for cultivated endophytes, as only with those is it possible to assess phytopathogenicity. However, in most cases, pathogenicity assays are not performed, or they are performed with only one plant species, although pathogenicity might occur with a different plant genotype or under different conditions. Second, it is well known that some bacteria may live as latent pathogens within plants and become pathogenic under specific conditions (6) or are pathogens of other plants. Third, it has been shown that bacterial strains belonging to a well-known pathogenic species of a specific plant host may even have growth-promoting effects on another plant (49, 50). These findings demonstrate that it is not trivial to clearly distinguish a nonpathogenic endophyte from a pathogen and that properties such as pathogenicity or mutualism may depend on many factors, including plant and microbial genotype, microbial numbers, and quorum sensing or environmental conditions. With cultivation-independent analyses, it is now even more difficult to assess the pathogenicity of individual microbiome members. In conclusion, we question the currently applied definition of endophytes and claim that the term “endophyte” should refer to habitat only, not function, and therefore that the term should be more general and include all microorganisms which for all or part of their lifetime colonize internal plant tissues.

PLANT-MICROBE SYMBIOSES

Different groups of bacteria and fungi interact with higher plants. Genetic links between the association of plants with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and root nodule symbioses have been found (51–53), suggesting that at least segments of bacterial and fungal endophytic populations coevolved with each other and with their host. Mutualistic interactions leading to adaptive benefits for both partners occasionally evolved to even more complex forms, in which more than two partners were involved (10).

Evolution of Plant-Fungus Symbioses

Plant-fungus symbioses are known to have occurred during early colonization of land by terrestrial plants (54). The fungal group Glomeromycota has for a long time been the prime candidate for interaction with the first terrestrial plants, in the Ordovician era, but members of the Mucoromycotina are also speculated to have had symbiotic interactions with the first terrestrial plants (55). The association between AMF and plants evolved as a symbiosis, facilitating the adaption of plants to the terrestrial environment (56). The oldest known fossils representing terrestrial fungi with properties similar to those of AMF were collected from dolomite rocks in Wisconsin and are estimated to be 460 million years old, originating from the Ordovician period (54). It was therefore assumed that terrestrial AMF already existed at the time when bryophyte-like, “lower” plants covered the land. All other plant-AMF interaction types, such as ectomycorrhiza and orchid and ericoid mycorrhiza, appeared later and are considered to be derived from the first interactions between AMF and the first terrestrial plants (57).

It is assumed that no tight interactions between plants and fungi occurred initially but that, due to nutritional limitations, interactions between both partners evolved (57). It is still unknown whether the first AMF were already mutualistic symbionts or whether mutualistic lifestyles evolved from pathogenic forms. The internal spaces of plants became important habitats for plant-colonizing fungi. Specific tissue layers, such as the endodermis and exodermis, evolved, forming the borders of cortex cells surrounding fungi internalized in the roots (57). This finally resulted in the formation of arbuscules, which are typical structures in plant-AMF interactions. AMF became more dependent on their host for energy sources and adopted an obligate life cycle. On the other hand, intraradical hyphae increased the total root surface area of the host plant, allowing substantially more nutrient (P) uptake from the soil environment. As evolution progressed, more extreme forms of plant-fungus interactions appeared, such as mycoheterotrophic plants, i.e., plants that fully exploit their fungal counterparts during interaction (58).

Evolution of Plant-Bacterium Symbioses

The best-described plant-bacterium interaction is the one between leguminous plants and rhizobia. The interactions of nitrogen-fixing bacteria belonging to the genera Azorhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, Ensifer, Mesorhizobium, Rhizobium, and Sinorhizobium (collectively called “rhizobia”; for a full list of genera, see http://www.rhizobia.co.nz/taxonomy/rhizobia) are capable of inducing differentiation in root nodule structure, as demonstrated in Fabaceae and Parasponia plants (60). Typical symptoms in roots of leguminous plants infected by rhizobia are curling of root hairs and the appearance of infection threads and, finally, nodule primordia in the inner root layers—these are all processes mediated by signal exchange between plants and rhizobia (for a review, see reference 61). In primordium cells, the bacteria become surrounded by the plant membrane, and together, the bacteria and plant structure form the symbiosome, in which atmospheric nitrogen is fixed and transferred in exchange for carbohydrates (62). Symbiosomes have a structure similar to that of mycorrhizal arbuscules, which are also surrounded by a plant membrane. It is interesting that a number of legume-nodulating rhizobial strains form endophytic associations with monocotyledonous plants, such as rice (63), maize (64), and sugarcane (65), and dicotyledonous plants, such as sweet potato (66). Although nodule primordia were not observed, rhizobial nifH transcripts were found inside roots of rice and sugarcane plants (12, 65). The contribution of rhizobium-assimilated nitrogen to the total nitrogen pool in nonleguminous plants is still a matter of debate (67).

Recent studies revealed that the nature of the association of both AMF and rhizobia with host plant species can be mutualistic, parasitic, or nonsymbiotic (68, 69). A meta-analysis demonstrated that the plant response to AMF depends on various factors, most importantly the host plant type and N fertilization (69). Apart from mutualistic rhizobia, parasitic strains which infect legumes but fix little or no nitrogen have been reported (68). The rhizobium-legume symbiosis seems to be characterized by a continuum of different types of symbiotic interactions, in many cases dependent on the presence of symbiotic genes, frequently located on plasmids, needed for the mutualistic interaction (70).

ENDOPHYTE DIVERSITY

Prokaryotic Endophytes

We present an overview of prokaryotic endophytes reported to date, based on a curated database (see Data Sets S1 and S2 in the supplemental material) comprising all currently available 16S rRNA gene sequences assigned to endophytes (published in peer-reviewed journals indexed to the PubMed or Web of Science databases and deposited in the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration repository, as of 1 March 2014). Only sequences longer than 300 bp and from studies that applied well-established surface sterilization procedures, such as the application of sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) or mercury chloride (HgCl2), were included. The database comprises 4,146 16S rRNA gene sequences from isolates (56%) and 3,202 16S rRNA gene sequences from uncultured organisms (44%). Sequences from earlier next-generation high-throughput sequencing technologies (e.g., 454 pyrosequencing) were able to produce only relatively short nucleotide stretches (i.e., <300 bp), which limits the discriminatory power for classification of different taxonomic groups, and thus were not included in our database.

Prokaryotic endophytes considered in this database are diverse and comprise 23 recognized and candidate phyla (2 from Archaea and 21 from Bacteria) (Table 1; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Despite this remarkable diversity, more than 96% of the total number of endophytic prokaryotic sequences (n = 7,348) are distributed among four bacterial phyla (54% Proteobacteria, 20% Actinobacteria, 16% Firmicutes, and 6% Bacteroidetes). These phyla have also been reported to be dominant in the plant environment (71, 72). The database comprises only a few (n = 29) sequences from Archaea, which were mainly detected in coffee cherries (73), rice and maize roots (74, 75), and the arctic tundra rush Juncus trifidus (76).

TABLE 1.

Summary of the endophytic data set from all peer-reviewed publications with prokaryotic 16S rRNA gene sequencesa

| Phylogenetic affiliationb | No. of sequences | % of sequences |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 7,319 | |

| Acidobacteria | 53 | 0.72 |

| Actinobacteria | 1,461 | 19.88 |

| Armatimonadetes | 6 | 0.08 |

| Bacteroidetes | 462 | 6.29 |

| GOUTA4c | 1 | 0.01 |

| ODc | 6 | 0.08 |

| TM7c | 2 | 0.03 |

| Chlamydiae | 8 | 0.11 |

| Chlorobi | 5 | 0.07 |

| Chloroflexi | 3 | 0.04 |

| Cyanobacteria | 102 | 1.39 |

| Deinococcus-Thermus | 7 | 0.1 |

| Elusimicrobia | 1 | 0.01 |

| Firmicutes | ||

| Bacilli | 1,132 | 15.41 |

| Clostridia | 68 | 0.93 |

| Fusobacteria | 3 | 0.04 |

| Nitrospirae | 3 | 0.04 |

| Planctomycetes | 5 | 0.07 |

| Proteobacteria | ||

| Alpha- | 1,337 | 18.2 |

| Beta- | 736 | 10.02 |

| Delta- | 26 | 0.35 |

| Epsilon- | 3 | 0.04 |

| Gamma- | 1,878 | 25.56 |

| Spirochaetae | 3 | 0.04 |

| Tenericutes | 2 | 0.03 |

| Verrucomicrobia | 6 | 0.08 |

| Archaea | 29 | |

| Euryarchaeota | 23 | 0.31 |

| Thaumarcheota | 6 | 0.08 |

| Total | 7,348 |

Endophytic sequences with >300 bp were retrieved from peer-reviewed manuscripts available in the ISI Web of Science and PubMed databases (as of 1 March 2014).

Based on comparison with the small-subunit rRNA SILVA database (version 115) (372) by using the SINA aligner (364).

Candidate division phyla.

Most of the prokaryotic endophytes (26%) could be assigned to the Gammaproteobacteria, including 56 recognized and 7 unidentified genera as well as the “Candidatus Portiera” genus (see Data Set S1 and Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). It should be noted that Gammaproteobacteria also comprise a large number of genera and species which are known as phytopathogens (77, 78). Endophytic Gammaproteobacteria are largely represented by a few genera: Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, Pantoea, Stenotrophomonas, Acinetobacter, and Serratia (>50 sequences each) (see Fig. S2). Members of the genus Enterobacter associate with diverse organisms, and their ecological relationships range from mutualism to pathogenesis. For instance, four species of Enterobacter in plants have been described as opportunistic pathogens, whereas many others (at least five) are beneficial to the host (79), including a monophyletic clade that was recently named Kosakonia (80). The nature of the interactions of other members of the Gammaproteobacteria, including Pseudomonas, Pantoea, and Stenotrophomonas species, is similar to that for Enterobacter, with few species described as plant pathogens and many others described as plant mutualists. Similarly, the Alphaproteobacteria encompass a large number (18%) of endophytic sequences, belonging to 57 recognized and 14 unidentified genera as well as the “Candidatus Liberibacter” genus (see Data Set S1 and Fig. S3). Most of the sequences can be assigned to the genera Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium, known for their N2-fixing symbioses with legumes, and Methylobacterium and Sphingomonas (>50 sequences each) (see Fig. S3). Methylobacterium is capable of growth on methanol as the sole source of carbon and energy and has been hypothesized to potentially dominate the phyllosphere environment (81). The Betaproteobacteria sequences (10%) comprise 53 recognized and 10 unidentified genera of endophytes (see Data Set S1), mainly belonging to Burkholderia, Massilia, Variovorax, and Collimonas (≥40 sequences each) (see Fig. S4). Burkholderia strains have the potential to colonize a wide range of hosts and environments (82), suggesting a great metabolic and physiological adaptability of endophytes belonging to this genus.

Among Gram-positive endophytes, the class Actinobacteria (20%) comprises diverse endophytes belonging to 107 recognized and 15 unidentified genera (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). Most of the sequences group with the genera Streptomyces, Microbacterium, Mycobacterium, Arthrobacter, and Curtobacterium (>50 sequences each) (see Fig. S5). Members of the genus Streptomyces are well known for their capacity to synthesize antibiotic compounds (83). The class Bacilli (15%) comprises 25 recognized and 2 unidentified genera of endophytes (see Data Set S1). The genera Bacillus, Paenibacillus, and Staphylococcus have more than 100 sequences assigned to them (see Fig. S6). Within the genus Bacillus, the species Bacillus thuringiensis is well known for its production of parasporal crystal proteins with insecticidal properties (84).

Overall, most bacterial endophytes belong to mainly four phyla, but they encompass many genera and species. Their functions cannot be assigned clearly to taxonomy and seem to depend on the host and environmental parameters.

Eukaryotic Endophytes

A data set of eukaryotic endophytic full-length internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions was also built for this study (see Data Set S3 in the supplemental material). A total of 8,439 sequences were retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nucleotide database (Table 2 shows the details of data retrieval and analysis; data were current as of 1 August 2014). Endophytes mainly belong to the Glomeromycota (40%), Ascomycota (31%), Basidiomycota (20%), unidentified phyla (8%), and, to a lesser extent, Zygomycota (0.1%) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Summary of the endophytic data set from all peer-reviewed eukaryotic full-length ITS sequences (as of 1 August 2014)a

| Taxonomic assignmentb | No. of sequences | % of sequences |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 8,439 | |

| Ascomycota | 2,610 | 30.92 |

| Archaeorhizomycetes | 2 | 0.02 |

| Dothideomycetes | 1,272 | 15.07 |

| Eurotiomycetes | 54 | 0.64 |

| Incertae sedis | 2 | 0.02 |

| Lecanoromycetes | 5 | 0.06 |

| Leotiomycetes | 171 | 2.03 |

| Orbiliomycetes | 0 | 0 |

| Pezizomycetes | 112 | 1.33 |

| Saccharomycetes | 11 | 0.13 |

| Sordariomycetes | 785 | 9.30 |

| Unidentified | 196 | 2.32 |

| Basidiomycota | 1,712 | 20.3 |

| Agaricomycetes | 1,560 | 18.49 |

| Atractiellomycetes | 26 | 0.31 |

| Cystobasidiomycetes | 3 | 0.04 |

| Exobasidiomycetes | 0 | 0 |

| Microbotryomycetes | 23 | 0.27 |

| Pucciniomycetes | 1 | 0.01 |

| Tremellomycetes | 30 | 0.36 |

| Ustilaginomycetes | 0 | 0 |

| Unidentified | 69 | 0.82 |

| Glomeromycota | 3,390 | 40.17 |

| Glomeromycetes | 3,294 | 39.03 |

| Unidentified | 96 | 1.14 |

| Zygomycota | ||

| Incertae sedis | 5 | 0.06 |

| Unidentified | 722 | 8.56 |

Fungal ITS sequences were retrieved from the NCBI nucleotide database by using the following search strings for the endophytic data set: “Endophyt*[ALL] AND nuccore_PubMed[Filter] AND internal[Title]” and “Mycorrhiza*[ALL] AND nuccore_PubMed[Filter] AND internal[Title].” Full-length ITS (ITS1, 5.8S, and ITS2 regions) sequences were extracted using ITSx (365) and assigned to operational taxonomic units (OTUs; definition set at 97% sequence similarity) with UCLUST (366), using the QIIME pipeline (367).

The phylum Glomeromycota only comprises endophytes known as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) (85) (see Data Set S3 in the supplemental material). Most of the eukaryotic endophytes (39%) can be assigned to the class Glomeromycetes. All members of this class form ubiquitous endosymbioses with most land plants and are of undeniable ecological and economic importance (86–88). AMF of the genera Glomus and Rhizophagus form obligate symbioses with a wide variety of host plants from the subkingdom Embryophyta (86). Among the Ascomycota, a large number of endophytes are identified in the class Dothideomycetes (15%). Besides endophytes, many members of the Dothideomycetes class are necrotrophic plant-pathogenic fungi, which are remarkable because of their production of host-specific toxins, such as phytotoxic metabolites and peptides that are biologically active only against a particular plant species (89–92). Overall, this class contains many species of the genera Alternaria and Epicoccum comprising endophytes (see Data Set S3). Although Alternaria brassicae is considered an opportunistic plant pathogen (93), it is frequently detected in high abundance in healthy plants (94, 95). Many members of the class Sordariomycetes (9%) are endophytes, such as species of the genera Balansia, Epichloë, Nemania, Xylaria, and Colletotrichum, but this class is also well known for phytopathogenic members, such as Cryphonectria parasitica (the causal agent of chestnut blight), Magnaporthe grisea (rice blast), Ophiostoma ulmi and Ophiostoma novo-ulmi (Dutch elm disease), and Fusarium, Verticillium, and Rosellinia species (96).

Among the Basidiomycota (Table 2), the class Agaricomycetes (18%) contains a large number of endophytes, mainly mushroom-forming (basidiome) fungi causing wood decay, white and brown rot saprotrophs, and the beneficial ectomycorrhiza (EMC) symbionts (97). Furthermore, members of the order Sebacinales form mycorrhizal symbioses with a broad range of plants, including woody plants and members of the families Orchidaceae and Ericaceae and the division Marchantiophyta (98). Additional assigned classes containing endophytes are Atractiellomycetes, Cystobasidiomycetes, Microbotryomycetes, and Tremellomycetes (see Data Set S3 in the supplemental material). Similar to the case for bacterial endophytes, various taxa comprise known phytopathogens and strains without known pathogenic effects, indicating that the functions of endophytic fungi also cannot necessarily be linked to taxonomy.

LIFESTYLES OF ENDOPHYTES

Degrees of Intimacy between Plants and Endophytes

Microorganisms can be strictly bound to plants and complete a major part or even their entire life cycle inside plants. Microorganisms requiring plant tissues to complete their life cycle are classified as “obligate.” Well-documented examples of obligate endophytes are found among mycorrhizal fungi and members of the fungal genera Balansia, Epichloë, and Neotyphodium, from the family Clavicipitaceae (Ascomycota) (99, 100). On the other extreme are “opportunistic” endophytes that mainly thrive outside plant tissues (epiphytes) and sporadically enter the plant endosphere (101). Among these are rhizosphere-competent colonizers, such as bacteria of the genera Pseudomonas and Azospirillum and fungi of the genera Hypocrea and Trichoderma (102–105). It is interesting that endophytes, which are transmitted vertically via seeds, are often recovered as epiphytes, suggesting that various endophytes might also colonize surrounding host plant environments (106, 107). Between these two extremes is an intermediate group, which comprises the vast majority of endophytic microorganisms, the so-called “facultative” endophytes. Whether facultative endophytes use the plant as a vector for dissemination or are actively selected by the host is still a matter of debate (107–110). However, facultative endophytes consume nutrients provided by plants, which would in fact reduce the ecological fitness of the host plant. This point is therefore often used as an argument that the so-called facultative endophytes must be mutualists in plants, even if the details of the interaction are unclear.

Overlaps exist between these three groups; thus, these categories must be considered “marking points” within the continuum of colonization strategies existing among endophytes. Independent of class, the microbial species thriving inside plant tissues are ecologically fit to survive and to proliferate under the local conditions of the plant interior, and aspects of survival are discussed later.

COLONIZATION OF THE ENDOSPHERE

Colonization Behavior of Fungal Endophytes

Successful colonization by endophytes depends on many variables, including plant tissue type, plant genotype, the microbial taxon and strain type, and biotic and abiotic environmental conditions. Different colonization strategies have been described for clavicipitaceous and nonclavicipitaceous endophytes (111, 112). Species of the Clavicipitaceae, including Balansia spp., Epichloë spp., and Claviceps spp., establish symbioses almost exclusively with grass, rush, and sledge hosts (47, 113), in which they may colonize the entire host plant systemically. They proliferate in the shoot meristem, colonizing intercellular spaces of the newly forming shoots, and can be transmitted vertically via seeds (113). Some Neotyphodium and Epichloë species may also be transmitted horizontally via leaf fragments falling on the soil (114). At the stage of inflorescence development, the mycelium of Neotyphodium can also colonize ovules and be present during infructescence development in the scutellum and the embryo, as demonstrated for Lolium perenne (115). When the inflorescence of the grass host develops, Epichloë can also grow over the developing inflorescence and form stromata, which can be differentiated sexually with the help of Botanophila flies (116).

Based on colonization characteristics, Rodriguez et al. (117) classified clavicipitaceous endophytes as class 1 fungal endophytes. Fungi colonizing above- and below-ground plant tissues, i.e., the rhizosphere, endorhiza, and aerial tissues (118), and being horizontally and/or vertically transmitted (119) were grouped as class 2 fungal endophytes (117). Class 3 endophytes were defined to contain mostly members of the Dikaryomycota (Ascomycota or Basidiomycota), which are particularly well studied in trees, but also in other plant taxa and in various ecosystems (120–126). Members of this class are mostly restricted to aerial tissues of various hosts and are horizontally transmitted (127, 128). Class 4 endophytes comprise dark, septate endophytes, which, similar to mycorrhizal fungi, are restricted to roots, where they reside inter- and/or intracellularly in the cortical cell layers (129).

Colonization Behavior of Bacterial Endophytes

Many bacterial endophytes originate from the rhizosphere environment, which attracts microorganisms due to the presence of root exudates and rhizodeposits (130, 131). Mercado-Blanco and Prieto (132) suggested that the entry of bacterial endophytes into roots occurs via colonization of root hairs. To a certain extent, stem and leaf surfaces also produce exudates that attract microorganisms (130). However, UV light, the lack of nutrients, and desiccation generally reduce colonization of plant surfaces, and only adapted bacteria can survive and enter the plant via stomata, wounds, and hydathodes (130, 133). Endophytes may also penetrate plants through flowers and fruits via colonization of the anthosphere and carposphere (18, 130).

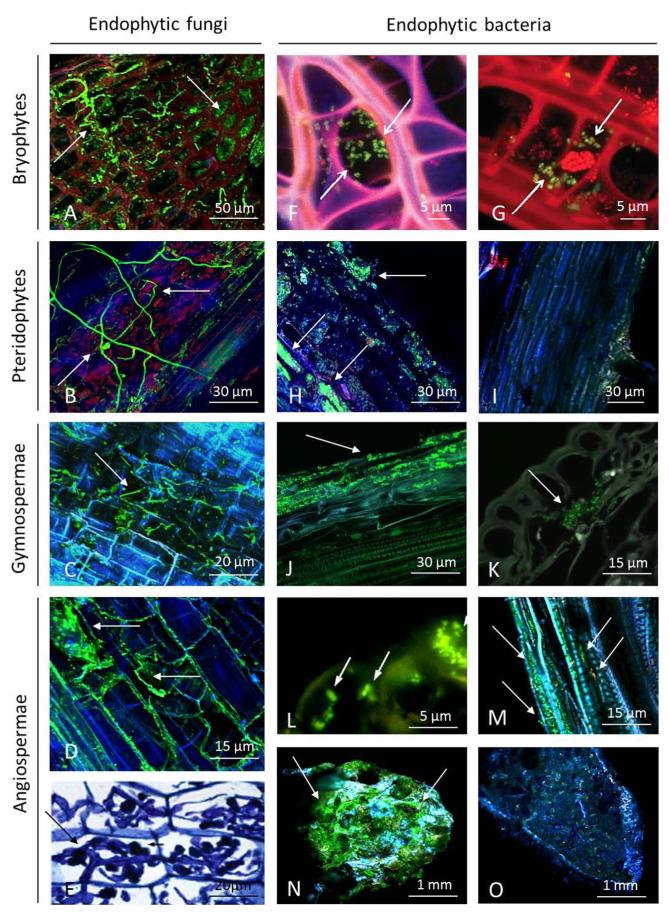

Depending on the strain, various colonization routes have been described, and specific interactions have been suggested (133, 134). Several of these routes involve passive or active mechanisms enabling bacteria to migrate from the rhizoplane to the cortical cell layer, where the plant endodermis represents a barrier for further colonization (130, 135). For bacteria that can penetrate the endodermis, the xylem vascular system is the main transport route for systemic colonization of internal plant compartments (134), whereas others colonize intercellular spaces locally. Bacteria have been shown to colonize xylem vessels, and the sizes of the holes of the perforation plates between xylem elements are sufficiently large to allow bacterial passage (130, 134, 136–138). However, vertical spread of bacteria through plants may take several weeks (139), and it is unclear why bacterial endophytes progress so slowly in the vascular system. Bacteria might even migrate to reproductive organs of Angiospermae plants and have been detected in the inner tissues of flowers (epidermis and ovary), fruits (pulp), and seeds (tegument) of grapevines (18) and in pumpkin flowers (140), as well as in the pollen of pine, a Gymnospermae plant (141). Suitable niches for colonization by bacterial endophytes have been described for different plant taxonomic groups, including Bryophytes, Pteridophytes, Gymnospermae, and Angiospermae (17, 130, 142) (Fig. 1). Overall, it is not known whether endophytes need to reach a specific organ or tissue for optimal performance of the functions which have been identified for endophytes.

FIG 1.

Microphotographs of endophytes showing (arrows) endophytic fungi in Sphagnum sp. (Alex Fluor 488-wheat germ agglutinin [WGA]) (A), endophytic fungi in a fern stem (Alex Fluor 488-WGA) (B), endophytic fungi in a stem of a Pinus sp. (Alex Fluor 488-WGA) (C), fungal endophytes in a stolon of a Trifolium sp. (Alex Fluor 488-WGA) (D), and mycorrhiza colonizing Eleutherococcus sieboldianus (toluidine blue) (E). (F and G) Bacterial endophytes in Sphagnum magellanicum (fluorescence in situ hybridization [FISH] with probes targeting Alphaproteobacteria [F] and Planctomycetes [G]). (H and I) Bacterial endophytes in fern leaves (double labeling of oligonucleotide probes-fluorescence in situ hybridization [DOPE-FISH] with EUBMIX-FLUOS probe for all bacteria [H] and with NONEUB-FLUOS probe [I]). (J and K) Colonization of Scots pine seedling by green fluorescent protein-tagged Methylobacterium extorquens DSM13060. (L) Bacterial endophytes in flowers of grapevine plants (FISH with EUBMIX-Dylight488 and LGC-Dylight549 probes, targeting all bacteria and Firmicutes, respectively). (M) Bacterial endophytes in the xylem of grapevine plants (DOPE-FISH with EUBMIX-FLUOS and HGC69a-Cy5 probes, targeting all bacteria and Actinomycetes, respectively). (N and O) Bacterial endophytes in a nodule of Medicago lupulina (DOPE-FISH with EUBMIX-FLUOS probe targeting all bacteria [N] and with NONEUB-FLUOS probe [O]). (Panel E reprinted from reference 362. Panels F and G reprinted from reference 17 by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd. [copyright 2011]. Panels J and K reprinted from reference 369 with kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media. Panel L reprinted from reference 18 with kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media. Panel M reprinted from reference 363 by permission of the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution.) All photographs show environmental samples, except those in panels J and K. Note that Alexa Fluor 488-WGA can also detect microbes other than fungi.

FUNCTIONS OF ENDOPHYTES

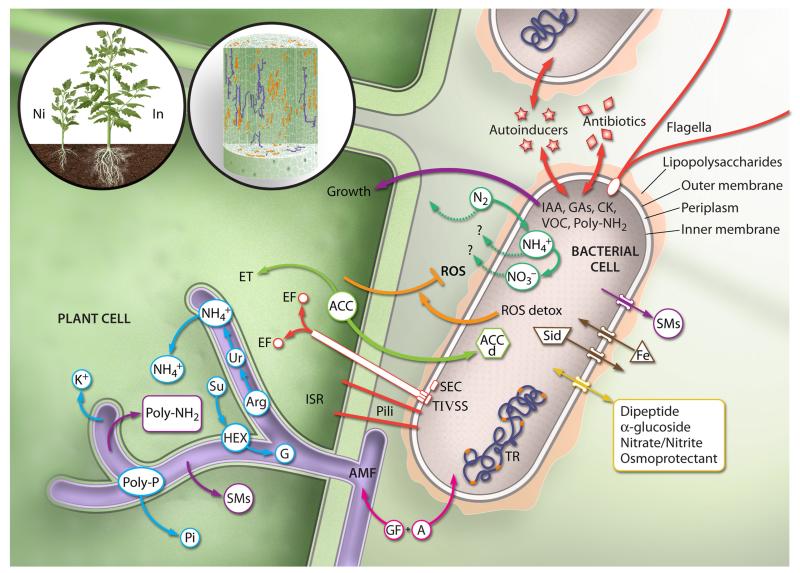

Some endophytes have no apparent effects on plant performance but live on the metabolites produced by the host. These are termed commensal endophytes, whereas other endophytes confer beneficial effects to the plant, such as protection against invading pathogens and (arthropod) herbivores, either via antibiosis or via induced resistance, and plant growth promotion (Fig. 2). A third group includes latent pathogens (143). Generally, endophytes can have neutral or detrimental effects to the host plant under normal growth conditions, whereas they can be beneficial under more extreme conditions or during different stages of the plant life cycle. For example, the fungus Fusarium verticillioides has a dual role both as a pathogen and as a beneficial endophyte in maize (144). The balance between these two states is dependent on the host genotype, but also on locally occurring abiotic stress factors that reduce host fitness, resulting in distortion of the delicate balance and in the occurrence of disease symptoms in the plant and production of mycotoxins by the fungus (144). However, beneficial effects have also been demonstrated, e.g., strains of the endophytic fungus F. verticillioides suppress the growth of another pathogenic fungus, Ustilago maydis, protecting their host against disease (145).

FIG 2.

Beneficial properties of endophytes. The left panel shows plants inoculated (In) with beneficial microorganisms that significantly improve plant growth compared to noninoculated (Ni) plants. Various microorganisms, in particular bacteria (orange) and fungi (purple), can colonize the internal tissues of the plant (middle panel). Once inside the plant, the endophytic bacteria and fungi interact intimately with the plant cells and with surrounding microorganisms (large panel). Endophytic fungi, represented here as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) (lilac), might form specialized structures, called arbuscules, where plant-derived carbon sources, mainly sucrose (Su), are exchanged for fungus-provided phosphate (Pi), nitrogen (NH4+), and potassium (K+) elements (blue). Plant cytoplasmic sucrose is transported to the periarbuscular space, where it is converted to hexose (HEX) to be assimilated by the fungus. Hexose is finally converted to glycogen (G) for long-distance transport. Phosphate and nitrogen are transported inside the fungal cytoplasm as polyphosphate granules (Poly-P), which are converted to Pi and arginine (Arg) in the arbuscule. Pi is transported to the host cytoplasm, whereas Arg is initially converted to urea (Ur) and then to ammonium (NH4+). Fungal and bacterial plant hormones, such as auxins (IAA), gibberellins (GAs), cytokinins (CKs), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and polyamines (Poly-NH2), as well as secondary metabolites (SMs), are transferred to the host (violet). Various bacterial structures, such as flagella, pili, secretion system machineries (e.g., TIV SS and SEC), and lipopolysaccharides, as well as bacterium-derived proteins and molecules, such as effectors (EF), autoinducers, and antibiotics, are detected by the host cells and trigger the induced systemic resistance (ISR) response (red). ACC, the direct precursor of ethylene (ET), is metabolized by bacteria via the enzyme ACC deaminase (ACCd), thus ameliorating abiotic stress (light green). A range of reactive oxygen species detoxification (ROS detox) enzymes might also ameliorate the plant-induced stress (orange). Diazotrophic bacterial endophytes are capable of fixing atmospheric nitrogen (N2) and might actively transport NH4+ and nitrate (NO3−) to the host (dark green). Bacterial processes of siderophore production (Sid) and uptake (Fe) that are involved in plant growth promotion, biocontrol, and phytoremediation are shown in brown. Examples of various substrates on which the transmembrane proteins are enriched among endophytes are shown in yellow. Transcriptional regulators (TR) are also shown (orange). Communications and interactions between cells of microorganisms dwelling inside the plant tissues are promoted by growth factor (GF), antibiotic (A) (fuchsia), and autoinducer molecules.

Plant Growth Promotion and Protection against Biotic and Abiotic Stresses

ISR and production of antibiotic secondary metabolites

Carroll (111) suggested in 1988 that endophytes play a role in the defense systems of trees. Because life cycles of endophytes are considered to be much shorter than the life cycle of their host, they may evolve faster in their host, resulting in higher selection of antagonistic forms that contribute to resistance against short-living pathogens and herbivores. Later, in 1991, Carroll suggested that endophyte-mediated induced resistance occurs in Douglas fir trees (146). Endophytes may induce plant defense reactions, so-called induced systemic resistance (ISR), leading to a higher tolerance of pathogens (147, 148). There is increasing evidence that at an initial stage, interactions between beneficial microorganisms and plants trigger an immune response in plants similar to that against pathogens but that, later on, mutualists escape host defense responses and are able to successfully colonize plants (148). Bacterial strains of the genera Pseudomonas and Bacillus can be considered the most common groups inducing ISR (reviewed in references 149 and 150), although ISR induction is not exclusive to these groups (151, 152). Bacterial factors responsible for ISR induction were identified to include flagella, antibiotics, N-acylhomoserine lactones, salicylic acid, jasmonic acid, siderophores, volatiles (e.g., acetoin), and lipopolysaccharides (152, 153) (Fig. 2). The shoot endophyte Methylobacterium sp. strain IMBG290 was shown to induce resistance against the pathogen Pectobacterium atrosepticum in potato, in an inoculum-density-dependent manner (151). The observed resistance was accompanied by changes in the structure of the innate endophytic community. Endophytic community changes were shown to correlate with disease resistance, indicating that the endophytic community as a whole, or just fractions thereof, can play a role in disease suppression (151). In contrast to bacterial endophytes, fungal endophytes have less frequently been reported to be involved in protection of their hosts via ISR (154–156).

Fungal endophytes are better known for their capacity to produce compounds that have growth-inhibitory activities toward plant pathogens and herbivores. These compounds comprise alkaloids, steroids, terpenoids, peptides, polyketones, flavonoids, quinols, phenols, and chlorinated compounds (157–159) (Fig. 2). Alkaloids produced by the clavicipitaceous fungi of grasses are among the best-described compounds produced by endophytes. For example, the neurotoxic indole-diterpenoid alkaloids, so-called lolitrems, are responsible for intoxication of cattle grazing on the endophyte-infected grass (160, 161). Some of these compounds, as well as some other alkaloids, are important for protection of the plant against insect herbivores (162, 163). Also, several reports have been published on the production of antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal, and insecticidal compounds by fungal endophytes, and most of these endophytes are transmitted horizontally, forming local infections in their hosts (157, 164). Not all horizontally transmitted fungal endophytes produce protective compounds, and due to the often small window of opportunity for contact with plant pathogens, in both time and space, their role in host protection against plant pathogens is still under dispute. A study made with cacao plants indicated that pathogens commonly colonize tree leaves but that infection does not always result in the occurrence of disease, and even that they can act as beneficial or harmless endophytes in their host (165–167). A recent report supported this finding and further demonstrated that production of endophytic antimicrobial compounds by endophytes can be induced by the presence of a pathogen (168).

Bacterial endophytes also produce antimicrobial compounds (Fig. 2). For example, the endophyte Enterobacter sp. strain 638 produces antibiotic substances, including 2-phenylethanol and 4-hydroxybenzoate (169). Generally, endophytic actinomycetes are the best-known examples of antimicrobial compound producers, and compounds discovered so far include munumbicins (170), kakadumycins (171), and coronamycin (172). Recently, multicyclic indolosesquiterpenes with antibacterial activity were identified in the endophyte Streptomyces sp. HKI0595, isolated from the mangrove tree (Kandelia candel) (173), and spoxazomicins A to C, with antitrypanosomal activity, were found to be produced by Streptosporangium oxazolinicum strain K07-0450T, isolated from orchid plants (174). Some of these compounds appear to be valuable for clinical or agricultural purposes (175), but their exact roles in plant-microbe interactions still need to be elucidated.

Production of additional secondary metabolites

Secondary metabolites are biologically active compounds that are an important source of anticancer, antioxidant, antidiabetic, immunosuppressive, antifungal, anti-oomycete, antibacterial, insecticidal, nematicidal, and antiviral agents (157, 175–182). In addition, endophytes produce secondary metabolites that are involved in mechanisms of signaling, defense, and genetic regulation of the establishment of symbiosis (183). Besides the production of secondary metabolite compounds, endophytes are also able to influence the secondary metabolism of their plant host (182). This was demonstrated in strawberry plants inoculated with a Methylobacterium species strain, in which the inoculant strain influenced the biosynthesis of flavor compounds, such as furanones, in the host plants (184–186). Recently, bacterial endophytes, along with bacterial methanol dehydrogenase transcripts, were localized in the vascular tissues of strawberry receptacles and in the cells of achenes, the locations where the furanone biosynthesis gene is expressed in the plant (187). Similarly, biosynthesis and accumulation of phenolic acids, flavan-3-ols, and oligomeric proanthocyanidins in bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) plants were enhanced upon interaction with a fungal endophyte, a Paraphaeosphaeria sp. strain (188).

Iron homeostasis

Some bacterial and fungal endophytes are producers of vivid siderophores (153, 189–192). Siderophores are essential compounds for iron acquisition by soil microorganisms (193, 194), but they also play important roles in pathogen-host interactions in animals (195, 196). The role of siderophores produced by endophytes in plant colonization is unknown, but it has been suggested that these compounds play a role in induction of ISR (153) (Fig. 2). Furthermore, siderophore production was shown to play an important role in the symbiosis of Epichloë festucae with ryegrass, as shown upon interruption of the siderophore biosynthesis gene cluster in E. festucae (191). It is possible that siderophores modulate iron homeostasis in E. festucae-infected ryegrass plants. Siderophores produced by endophytic Methylobacterium strains are also involved in suppression of Xylella fastidiosa, the causative agent of citrus variegated chlorosis in Citrus trees (189). A recent comparative genomic analysis of proteobacterial endophytes revealed that strains lacking the gene clusters involved in siderophore biosynthesis have a larger total number of genes encoding membrane receptors for uptake of Fe3+-siderophore complexes, hence potentially allowing them to take up siderophores produced by other endophytes (197).

Protection against biotic and abiotic stresses

Whereas most of the described endophytes protect the plant from biotic stresses, some endophytes can also protect the plant against different abiotic stresses. For example, fungal strains of Neotyphodium spp. were shown to be able to increase tolerance toward drought in grass plants by means of osmo- and stomatal regulation (198), and they protected the plants against nitrogen starvation and water stress (199). The root fungal endophyte Piriformospora indica was shown to induce salt tolerance in barley (200) and drought tolerance in Chinese cabbage plants (201). In both cases, increases in antioxidant levels were the proposed mechanisms behind elevation in stress tolerance in these plants. Colonization of fungal endophytes of the genus Trichoderma in cacao seedlings also resulted in a delay in the response to drought stress (202), and the bacterial endophyte Burkholderia phytofirmans strain PsJN elevates drought tolerance levels in maize (203) and wheat plants (204). Furthermore, fungal endophytes have been shown to interfere with cold tolerance of rice plants (205), and B. phytofirmans strain PsJN has been shown to enhance chilling tolerance in grapevine plantlets (206).

ACC deaminase is a bacterial enzyme that is often associated with alleviation of plant stress (Fig. 2). This enzyme is responsible for lowering the levels of ethylene in the plant by cleaving the plant-produced ethylene precursor 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) to ammonia and 2-oxobutanoate, preventing ethylene signaling (207). The plant hormone ethylene acts in the germination of seeds and in response to various stresses, and it is the key regulator of colonization of plant tissue by bacteria (208). This suggests that, apart from stress alleviation, ACC deaminase supports colonization of a number of bacterial endophytes. When the ACC deaminase gene of B. phytofirmans PsJN was inactivated, the endophyte lost the ability to promote root elongation in canola seedlings (209). Another study performed on cut flowers indicated that bacterial endophytes are able to colonize the shoot and that ACC deaminase delays flower senescence (210).

Plant growth stimulation

Some endophytes are involved in plant growth promotion, despite the fact that they are promoting growth at the expense of obtaining valuable nutrients provided by the host plant (211–213). High endophyte infection loads in plants indicate that benefit-cost balances are at least neutral or positive, suggesting that most endophytes must be beneficial to their hosts. Such beneficial effects may result from interference in photosynthesis and carbon fixation processes taking place in plants. A fungal grass endophyte strain of Neotyphodium lolii was found to influence CO2 fixation but was not shown to be able to interfere with light interception, photochemistry, or net photosynthesis (214). No effect on photosynthesis, stomatal conductance, photosynthetic water use efficiency, or the maximum and operating efficiencies of photosystem II was found in poplar trees inoculated with the bacterial plant growth-promoting endophyte Enterobacter sp. 638 (215). On the other hand, inoculation of wheat with the bacterium B. phytofirmans strain PsJN increased the photosynthetic rate, CO2 assimilation, chlorophyll content, and water use efficiency under drought conditions (204).

Phytohormone production by endophytes is probably the best-studied mechanism of plant growth promotion, leading to morphological and architectural changes in plant hosts (213, 216, 217). The ability to produce auxins and gibberellins is a typical trait for root-associated endophytes (213, 216–219). It was proposed that indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), a member of the auxin class, increases colonization efficiency (220), possibly via interference with the host defense system (221), and production of this compound or related compounds may be an important property for plant colonization by endophytes (Fig. 2). Cytokinin production is commonly observed in endophytes, but on one occasion, in a root-colonizing fungal strain of Piriformospora indica, cytokinin biosynthesis was demonstrated and mutational deletions in cytokinin biosynthesis genes resulted in abortion of any plant growth-promoting effect (222).

Besides the production of plant growth hormones, additional mechanisms for plant growth promotion exist. Adenine and adenine ribosides have been identified as growth-promoting compounds in endophytes of Scots pine (223). Volatile compounds, such as acetoin and 2,3-butanediol, can stimulate plant growth (224–226) and are produced by some bacterial endophytes (227, 228). Polyamines affect plant growth and development in plant-mycorrhiza interactions (229) and are produced by the bacterium Azospirillum brasilense (230). It can be expected that additional, not yet understood mechanisms exist among plant-associated bacteria to promote plant growth.

Nitrogen fixation

Nutrient acquisition for plants via nitrogen fixation is another mechanism behind plant growth promotion. This trait is well studied in rhizobial and actinorhizal plant symbioses. Several root endophytes fix nitrogen (e.g., Acetobacter diazotrophicus, Herbaspirillum spp., and Azoarcus spp.) (231, 232), but the efficiencies of nitrogen fixation in free-living endophytes are far lower than those in root nodules of leguminous plant-rhizobium interactions (233). One exception is the relatively high nitrogen fixation efficiency observed in endophytic strains of Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus in symbiosis with sugarcane plants (234). Other G. diazotrophicus strains were shown to be present in the microbiome of pine needles, including some potential N2-fixing strains (235). This indicates that G. diazotrophicus strains play important roles as nitrogen fixers in wider taxonomic ranges of host plants. Another example of a N2-fixing endophyte is Paenibacillus strain P22, which has been found in poplar trees (13). Strain P22 contributed to the total nitrogen pool of the host plant and induced metabolic changes in the plant. Nitrogen fixation contributes to the fitness of the host plant, especially in nitrogen-poor environments. Even if the quantities of fixed nitrogen measured in single nitrogen-fixing species are low, it remains to be clarified if the fixed N is for the endophytes’ own demands and/or for provision to the host plant (236).

In summary, various mechanisms in endophytes can explain the profound effects that endophytes have on their plant hosts. A recent report indicates that endophyte infection can also affect the gender selection of the host plant (237), which suggests that many new properties remain to be identified among endophytes.

Plant-Microbe Symbioses Leading to Improved Plant Fitness

Endophytes taxonomically differing from AMF and rhizobia were also shown to confer increased fitness to their hosts (238, 239). As an example, spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe) became more competitive toward bunchgrass (Koeleria macrantha) upon inoculation with the fungal endophyte Alternaria alternata (238). Stimulation of the production of secondary compounds by the endophyte played an important role in increased fitness of the host plant. However, inoculation with other Alternaria sp. endophytes did not result in increased fitness of knapweed plants (239), indicating that the endophyte-host plant interaction was strain specific. In another case, it was shown that infection of wild red fescue plants with the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea, a seed pathogen in many grass species, resulted in decreased herbivory by sheep (240). In association with its host, C. purpurea produces alkaloids that are toxic to mammalian species, thus protecting the host from predation. From this case, it is clear that particular microorganisms or taxa showing a lifestyle typical for endophytes can be both pathogenic and beneficial for their host. It was furthermore shown that plant-endophyte interactions can shift the gender balance in the offspring of the plant host. The fungus Epichlöe elymi, an endophyte in Elymus virginicus plants, is vertically and maternally transmitted from parent to offspring plants, thereby increasing its opportunity to establish new infections in succeeding plant generations (237). Manipulation of the sex ratio in offspring is an example of how endophytes can manipulate the fitness of their hosts, in analogy to Wolbachia infection of particular insect species, indicating that manipulation of the gender balance in offspring is common among higher eukaryote-microbe interactions (241).

DECIPHERING THE BEHAVIOR OF ENDOPHYTES BY COMPARATIVE GENOMIC ANALYSIS

Comparative genomics is an important tool for identifying genes and regulons that are important for plant penetration and colonization by endophytes (242). Specific properties discriminating endophytes from closely related nonendophytic strains have been found on several occasions (169, 197, 243–246). Lateral gene transfer (e.g., by mobile elements, such as plasmids and genomic islands) plays an important role in the acquisition of properties responsible for the capacity of bacteria and fungi to colonize the endosphere of plants. As an example, the assembled genome of the obligate biotroph fungus Rhizophagus irregularis was shown to contain up to 11% transposable elements (244). No loss of metabolic complexity was detected, only a drift of genes involved in toxin synthesis and in degradation of the plant cell wall. Also, the genome sequence of the competent bacterial endophyte Enterobacter sp. 638 revealed many transposable elements, which were often flanked by genes relevant to host-bacterium interactions (e.g., amino acid/iron transport, hemolysin, and hemagglutinin genes), as well as a large conjugative plasmid important for host colonization (169).

A comparative genomic and metabolic network study revealed major differences between pathogenic (n = 36) and mutualistic (n = 28) symbionts of plants in their metabolic capabilities and cellular processes (246). Genes involved in biosynthetic processes and functions were enriched and more diverse among plant mutualists, while genes involved in degradation and host invasion were predominantly detected among phytopathogens. Pathogens seem to require more compounds from the plant cell wall, whereas plant mutualists metabolize more plant-stress-related compounds, thus potentially helping in stress amelioration. The study revealed the presence of secretion systems in pathogen genomes, probably needed to invade the host plants, while genomic loci encoding nitrogen fixation proteins and ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO) proteins were more exclusive to mutualistic bacteria (246). Bacteria carrying relatively large genomes are often able to successfully colonize a wide range of unrelated plant hosts, as well as soils, whereas strains with smaller genomes seem to have a smaller host range (247).

Comparative Genomics To Elucidate Specific Properties That Evolved in Bacterial Endophytes

To further expand on potential functional and mechanistic aspects of endophytes, we compared the genomes of 40 well-described bacterial strains which were isolated from the plant endosphere (i.e., endophytes) with those of 42 nodule-forming symbionts, 29 well-described plant bacterial pathogens, 42 strains frequently found in the rhizosphere (i.e., rhizosphere bacteria), and 49 soil bacteria (see Data Set S4 in the supplemental material). Sequences from protein-encoding genes of each genome were assigned KEGG Ortholog (KO) tags by using the Integrated Microbial Genome (IMG) comparative analysis system (248). A feature-by-sample contingency table was created, using properties with abundances of >25% and samples within each group with <98% functional similarity. The assigned KO tags were normalized by cumulative sum scaling (CSS) normalization, and then a mixture model that implements a zero-inflated Gaussian distribution was computed to detect differentially abundant properties by using the metagenomeSeq package (249). A comparison of relevant properties in the process of host colonization and establishment for each investigated group (i.e., nodule-forming symbionts, phytopathogens, and bacterial strains isolated from the rhizosphere and from soil) and for endophytes is shown in Table 3. We are aware of the fact that endophytes may colonize the rhizosphere (soil) or may even, under certain circumstances, have a phytopathogenic lifestyle (as discussed in other parts of this review). However, the aim of the comparative genomic analysis was to obtain indications of potential typical endophytic properties, which require further confirmation.

TABLE 3.

Comparative genomics of properties relevant to plant colonization and establishmenta

| Log2 fold change in abundance in the indicated group versus endophytes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category and feature (gene) | Symbionts | Phytopathogens | Rhizosphere bacteria | Soil bacteria |

| Chemotaxis and motility | ||||

| Aerotaxis (aer) | −0.983*** | 0.029 | −0.259 | −0.354 |

| Serine chemotaxis (tsr) | −0.697** | 0.471* | −0.284 | 0.162 |

| Aspartate/maltose chemotaxis (tar) | −0.315 | −0.262 | −0.276* | −0.041 |

| Ribose chemotaxis (rbsB) | 1.076*** | −0.423 | −0.108 | −0.252 |

| Galactose chemotaxis (mglB) | −0.257*** | 0.030 | 0.390*** | 0.283** |

| Dipeptide chemotaxis (tap) | −0.174** | −0.172 | −0.215*** | −0.089 |

| Response regulators (cheBR) | −0.276 | −0.519*** | −0.153 | −0.280* |

| Response regulator (cheV) | −0.880*** | −0.271 | 0.143 | 0.069 |

| Response regulator (cheD) | −0.206* | −0.086 | 0.040 | 0.009 |

| Response regulator (cheC) | −0.367* | −0.861*** | 0.096 | −0.298 |

| Response regulator (cheZ) | −0.271 | −0.202 | −0.396*** | −0.155 |

| Flagellar apparatus (fliI) | −0.252** | −0.201* | −0.149 | 0.045 |

| Chemotaxis and motility (motA) | −0.555*** | −0.297* | 0.094 | −0.065 |

| Signal transduction—two-component systems | ||||

| Magnesium assimilation (phoQ-phoP) | −0.951*** | 0.052 | −0.034 | 0.042 |

| Stress (rstB-rstA) | −0.951*** | −0.022 | −0.005 | 0.070 |

| Carbon source utilization (creC-creB) | −0.726*** | 0.077 | −0.098 | −0.016 |

| Multidrug resistance (baeS-baeR) | −0.804*** | 0.032 | 0.074 | 0.000 |

| Copper efflux (cusS-cusR) | −0.821*** | −0.415 | 0.258 | 0.300 |

| Carbon storage regulator (barA-uvrY) | −0.989*** | −0.044 | −0.058 | 0.017 |

| Antibiotic resistance (evgS-evgA) | −0.868*** | −0.522*** | 0.143 | −0.288 |

| Nitrogen fixation/metabolism (ntrY-ntrX) | −0.037 | −0.233*** | −0.615*** | −0.089 |

| Type IV fimbria synthesis (pilS-pilR) | −0.902*** | 0.038 | 0.039 | 0.180 |

| Amino sugar metabolism (glrK-glrR) | −0.974*** | −0.021 | −0.061 | 0.232 |

| Twitching motility (chpA-chpB) | −0.783*** | 0.120 | 0.026 | 0.003 |

| Extracellular polysaccharide (wspE-wspR) | −0.612*** | −0.072 | 0.044 | −0.023 |

| Cell fate control (pleC-pleD) | −0.131*** | −0.255** | −0.639*** | 0.094 |

| Redox response (regB-regA) | −0.004 | −0.204* | −0.099 | −0.136 |

| Transcriptional regulators | ||||

| Nitrogen assimilation (nifA) | −0.133 | −0.757*** | −0.359*** | −0.220 |

| Carbon storage regulator (sdiA) | 0.617*** | −0.067 | −0.055 | −0.279* |

| Biofilm formation (crp) | −0.976*** | 0.036 | −0.036 | 0.068 |

| Nitric oxide reductase (norR) | −0.625*** | −0.156* | 0.193 | 0.129 |

| NAD biosynthesis (nadR) | −0.257*** | 0.012 | −0.103 | −0.079 |

| Beta-lactamase resistance (ampR) | 0.091 | 0.016 | −0.060 | −0.339*** |

| Pyrimidine metabolism (pyrR) | −0.326** | −0.051 | 0.121 | 0.015 |

| Thiamine metabolism (tenA) | 0.070 | −0.976*** | 0.109 | 0.195 |

| Stress-related enzymes | ||||

| Glutathione peroxidase (btuE) | −0.360** | −0.031 | 0.104 | −0.195 |

| Glutathione S-transferase (gst) | 0.562** | −0.435* | −0.230 | −0.351 |

| Catalase (katE) | −0.362* | −0.237 | 0.084 | 0.042 |

| Transport system | ||||

| ABC, capsular polysaccharide (kpsT) | −0.045 | −0.277*** | −0.244* | −0.221 |

| ABC, thiamine-derived products (thiY) | −0.449** | −0.958*** | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| ABC, spermidine/putrescine (potD) | 0.718*** | −0.308** | 0.092 | 0.081 |

| ABC, dipeptide (dppF) | 0.204** | −0.230*** | −0.027 | 0.09 |

| ABC, branched-chain amino acid (livK) | 0.571 | −0.884** | −0.629 | −0.734 |

| ABC, cystine (fliY) | −0.28 | −0.270* | 0.225 | −0.355* |

| ABC, methionine (metN) | −0.478*** | −0.336* | 0.031 | −0.163 |

| ABC, histidine (hisJ) | −0.302 | −0.096 | 0.349* | −0.266* |

| ABC, lysine/arginine/ornithine (argT) | 0.216 | −0.336 | 0.464 | −0.182 |

| ABC, l-arabinose (araG) | 0.145 | −0.067 | 0.066 | −0.342*** |

| ABC, rhamnose (rhaT) | −0.129 | −0.826*** | −0.043 | −0.724*** |

| PTS, cellobiose (celB) | −1.425*** | −0.947*** | −0.073 | −0.146 |

| PTS, glucose (ptsG) | −0.860*** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| PTS, mannose (manY) | −0.433*** | −0.287** | −0.374*** | −0.264* |

| PTS, ascorbate (sgaA) | −0.433** | 0.003 | −0.207 | 0.158 |

| PTS, phosphocarrier (furB) | −0.317* | −0.007 | −0.065 | 0.059 |

| Others, multidrug (mdtB) | 0.076 | −0.042 | −0.217** | 0.134 |

| Other, tricarboxylic (tctA) | 0.670*** | −0.018 | 0.352* | 0.481* |

| Others, C4-dicarboxylate (dctP) | −0.123 | −0.462* | 0.382* | 0.553** |

| Others, membrane pore protein (ompC) | −1.149*** | 0.090 | −0.053 | 0.071 |

| Secretion systems | ||||

| Type I RaxAB-RaxC system (raxB) | −0.270 | 0.357 | −0.234 | −0.186 |

| Type II general pathway protein (gspD) | −0.199 | 0.213 | −0.265 | 0.064 |

| Type III secretion core apparatus (yscJ) | 0.354* | 0.263** | 0.051 | −0.181** |

| Type IV conjugal DNA protein (virB2) | 0.370 | 0.125 | −0.718*** | −0.143 |

| Type VI Imp/Vas core components (hcp) | −0.360 | −0.038 | −0.045 | 0.095 |

| Twitching motility protein (pilJ) | −0.850*** | 0.058 | 0.028 | −0.002 |

| Type I pilus assembly protein (fimA) | −0.676*** | −0.300 | 0.282 | 0.158 |

| Plant growth-promoting properties | ||||

| Nitrogenase (nifH) | 0.301** | −0.676*** | 0.226 | 0.030 |

| ACC deaminase (acdS) | 0.118 | 0.223 | 0.119 | −0.344** |

| Acetoin reductase (budC) | 0.024 | −0.259*** | −0.024 | −0.059 |

| Acetolactate decarboxylase (alsD) | −1.000*** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Butanediol dehydrogenase (butB) | −0.089 | −0.090 | 0.469** | −0.319 |

| IAA biosynthesis, IAM pathway (amiE) | 0.201 | −0.067 | −0.017 | −0.029 |

| IAA biosynthesis, IPyA pathway (ipdC) | 0.077 | −0.157 | 0.291*** | −0.043 |

| IAA biosynthesis, IAN pathway (nit) | −0.156 | 0.088 | 0.084 | −0.019 |

| IAA biosynthesis, IAN pathway (nthAB) | −0.136 | −1.054*** | −0.596*** | −0.147 |

The relative abundances of the assigned functional properties in each investigated group (symbionts [n = 42], phytopathogens [n = 29], rhizosphere bacteria [n = 42], or soil bacteria [n = 49]) compared to endophytes (n = 40) are shown as normalized log2 fold changes. Negative values are shown if the endophyte group has a higher abundance.

Significant changes were computed with a zero-inflated Gaussian mixture model, and the alpha levels, denoted by *, **, and ***, were assigned to q-value thresholds of 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively.

Motility and chemotaxis

The ability to sense and respond to environmental cues is one of the major properties driving colonization of microorganisms (249–252). Our comparative genomic analysis of properties involved in chemotaxis and motility of bacteria suggested that protein-encoding genes related to the use of aspartate/maltose (Tar) and dipeptides (Tap) are more abundant among endophytes than among strains obtained from the rhizosphere. The response regulator proteins CheBR and CheC and the flagellum biosynthesis and motility mechanisms are more abundant among endophytes than among phytopathogens (Table 3). These results indicate the specificity of aspartate and dipeptide metabolism among endophytes, whereas serine metabolism seems to be used largely by phytopathogens. In addition, endophytes might be more responsive to different environmental cues than phytopathogens and nodule-forming symbionts.

Signal transduction

Regulation of two-component response systems is essential for the process of bacterial cell communication and fundamental for the synchronization of cooperative behavior (253, 254). In this category, bacterial endophytes differ mainly from nodule-forming symbionts and only marginally from the other investigated groups. Genes putatively involved in antibiotic resistance (evgS and evgA), redox response (regB and regA), nitrogen fixation and metabolism (ntrY and ntrX), and cell fate control (pleC and pleD) are found more prominently among endophytes than among phytopathogens and rhizobacteria (for the last two). A variety of energy-generating and energy-utilizing biological processes, including photosynthesis, carbon fixation, nitrogen fixation, hydrogen oxidation, denitrification, aerobic and anaerobic respiration, electron transport, and aerotaxis mechanisms, are known to be regulated in response to cellular redox balance (255) and might assist endophytes to thrive inside the host. The transmembrane nitrogen sensor protein NtrY interacts with the regulator protein NtrX to induce the expression of nif genes (256). Under nitrogen-limiting conditions, endophytes might be better able to fix nitrogen for their own benefit than phytopathogens or rhizobacteria. Overall, these results reveal distinct characteristics that are suitable for bacteria to thrive and survive in different environmental niches and conditions.

Transcriptional regulators

Transcriptional regulators are essential for prokaryotes to rapidly respond to environmental changes, improving their adaptation plasticity, cellular homeostasis, and colonization of new niches (257). Genes putatively involved in the transcriptional regulation of nitrogen assimilation (nifA), reduction of nitric oxide (norR), regulation of carbon storage (sdiA), beta-lactamase resistance (ampR), pyrimidine metabolism (pyrR), and thiamine metabolism (tenA) are detected in significantly larger proportions among endophytes than among the other investigated groups (Table 3). Regulatory genes related to the stoichiometry of nitrogen and carbon metabolism and those involved in the metabolism of nucleotides and vitamins and in stress responses might be of great importance for a life inside plants. Nodule-forming symbionts and plant pathogens that also thrive inside plant tissues reveal mechanisms different from those in endophytes to cope with stress and metabolism of nutrients, suggesting that each group has its own regulatory set of genes required for its typical behavioral responses.

Detoxification and stress-related enzymes

Due to an abrupt burst of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), the internal compartments of plants are inhospitable niches for aerobic microorganisms. Therefore, enzymes with detoxification capacities are essential for plant endosphere colonization and may also function as ameliorating agents upon host-induced stresses (258). Genes encoding glutathione peroxidase (btuE), glutathione S-transferase (gst), catalase (katE), and nitric oxide reductase (norR) are enriched, according to our analysis, in endophyte genomes compared to phytopathogen or nodule-forming symbiont genomes (Table 3). These ROS- and RNS-scavenging enzymes might assist endophytes to cope with the plant oxidative burst and might also ameliorate host biotic and abiotic stresses by protecting plant cells from oxidative damages (12, 259).

Transporters

Nutrient transport is an important function for life inside plants (169, 197). The proportion of endophytes harboring genes for ATP-binding cassette (ABC), major facilitator superfamily (MFS), phosphotransferase system (PTS), solute carrier family (SLC), and other transport systems varied largely in our analysis (Table 3). Genes putatively involved in the uptake of capsular polysaccharides, organic ions, peptides, amino acids, and carbohydrates were detected more prominently among endophytes than in the other investigated groups (Table 3). These results indicate the complexity of nutrient transport systems of endophytes, which might reflect their various lifestyle strategies for acquiring nutrients inside plants.

Secretion systems

Protein secretion plays an important role in plant-bacterium interactions (67, 260). Major differences in secretion systems of endophytes and nodule-forming symbionts were observed in our analysis (Table 3). Genes putatively involved in type III secretion systems are more typical of nodule-forming symbionts and phytopathogens than of endophytes, whereas they are detected in a significantly larger proportion of endophytes than soil bacteria (Table 3). This type of secretion system is more often employed by pathogens to manipulate host metabolism (261, 262). Conversely, type IV conjugal DNA-protein transfer secretion systems were detected more prominently among endophytes than among rhizosphere bacteria (Table 3). Type IV secretion is likely to be involved in host colonization and conjugation of DNA (263–265). Protein-encoding genes involved in adhesion to the host via twitching motility and type I pilus assembly are also detected more prominently among endophytes than among nodulating symbionts. These systems might be determinants of host colonization success (266, 267).

Genes involved in plant growth promotion

The nitrogenase (nifH) gene, putatively involved in the fixation of atmospheric N2, was detected in a significantly larger proportion of endophytes than of phytopathogens (Table 3). Surprisingly, 28% of the investigated group of prokaryotic endophytes harbored this gene, indicating that it has an important function in improving plant productivity under conditions of N limitation (see above). One of the genes thought to be involved in plant stress alleviation, encoding 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase (acdS), is detected more prominently among endophytes than among soil bacteria. Recent analyses of bacterial endophyte genomes suggest that ACC deaminase is not as widely spread among endophytes as previously thought (197, 263). However, endophytes differ significantly in their favored pathways for the biosynthesis of the plant hormones acetoin, 2,3-butanediol, and IAA compared to phytopathogens or rhizosphere bacteria, thus suggesting some particular characteristics that promote plant growth.

To summarize, genomic differences can be found between the different functional groups (i.e., endophytes, nodule-forming symbionts, phytopathogens, rhizobacteria, and soil bacteria), but we have to be aware that borders between functional groups are not clear-cut. Properties that are largely discriminative for endophytes compared to the other groups are a higher responsiveness to environmental cues, nitrogen fixation, and protection against reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Endophytes might exhibit phytopathogenic effects under certain conditions, and rhizosphere bacteria might also be able to colonize plants internally. Furthermore, the balance between mutualism and antagonism depends on multiple parameters and might depend on a very fine-tuned interaction between microbial elicitors and plant responses (268).

PATHOGENS AND ENDOPHYTES: THE BALANCE OF THE INTERACTION IS CRUCIAL

Pathogenicity: Definition and Mechanisms

Pathogenicity to humans, animals, and plants is the most acclaimed feature of microorganisms. Traditionally, pathogens have been defined as causative agents of diseases, guided by Koch’s postulates for more than a century and later advanced by making use of molecular markers (269). Next-generation sequencing-based technologies have drastically revolutionized our knowledge of the microbiome, and also of pathogens (270, 271). We learned particularly from the human microbiome that it is involved in many more diseases than recently thought and that pathogen outbreaks are associated with shifts of the whole community, including those supporting pathogens (272, 273). Recently, this was also shown for plant pathogens (140, 274).