Abstract

Safety and efficacy data on pegylated asparaginase in adult acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) induction regimens is limited. The UK National Cancer Research Institute UKALL14 trial NCT01085617 prospectively evaluated the tolerability of 1000 IU/m2 PEG-ASP administered on days 4 and 18 as part of a 5-drug induction regimen in adults aged 25-65 years with de-novo ALL. Median age was 46.5 years. Sixteen of 90 patients (median age 56 years) suffered treatment-related mortality during initial induction therapy. Eight of 16 died of sepsis in combination with hepatotoxicity. Age and Philadelphia (Ph) status were independent variables predicting induction death >40yrs versus ≤40yrs, odds ratio (OR) 18.5 (2.02-169.0), p =0.01; Ph- versus Ph+ disease, OR 13.60 (3.52 – 52.36), p <0.001. Of 74 patients who did not die, 37 (50.0%) experienced at least one grade 3/4 PEG-ASP-related adverse event, most commonly hepatotoxicity (36.5%, n=27). A single dose of PEG-ASP achieved trough therapeutic enzyme levels in 42/49 (86%) of patients tested. Whilst PEG-ASP delivered prolonged asparaginase activity in adults, it was difficult to administer safely as part of the UKALL14 intensive multi-agent regimen to those over the age of 40 years. It proved extremely toxic in patients with Ph+ ALL, possibly due to interaction with imatinib.

Introduction

Depletion of extracellular asparagine by parenteral administration of the enzyme L-asparaginase is a key component of most current therapeutic strategies in ALL. In children, intensive L-asparaginase treatment, typically delivered by pegylated Escherichia coli -derived (PEG-ASP) improves clinical outcome 1 2, 3 4 5, 6, offering a longer half-life 7 and a lower risk of anti-asparaginase antibody formation. Safety and efficacy is less well established in older adults 8, 9 and toxicity can be substantial10 - in a phase 2 trial, failure to deliver the intended doses was closely correlated with advancing age11

UKALL14 (NCT01085617) is an on-going, multicentre, phase 3 study which addresses several questions in the treatment of newly diagnosed adult ALL. A major study aim is to evaluate the addition of 2 doses of 1000 IU/m2 PEG-ASP to the standard induction regimen that had been evaluated in our previous study, UKALL1212 in which non-pegylated E coli L-asparaginase was given at 10,000IU daily on days 17-28 of phase 1 induction. The only other change to the ‘backbone’ induction regimen between the two consecutive national trials was the addition of a steroid pre-phase and the substitution of pulsed dexamethasone for prednisolone. The aim of these changes was to make our regimen more compatible with a “paediatric-inspired” intensive approach.

The overall endpoint of the trial is EFS. However, a specific endpoint of the PEG-ASP evaluation is toxicity related to PEG-ASP. Secondary endpoints include rate of complete remission (CR), overall survival, minimal residual disease (MRD) quantitation at the end of the first phase of induction and anti-asparaginase antibody formation. Here, we report on the outcome of PEG-ASP administered during induction in the first consecutive 91 trial subjects. At this point, it was judged by the trial management group that a toxicity end-point had been reached and a change was made to the PEG-ASP trial therapy.

Methods

UKALL 14 Induction Phase 1 Treatment

Eligible patients were ≥25 and ≤ 65 years old with newly diagnosed ALL, irrespective of Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome status. There was no exclusion for poor organ function or performance status at diagnosis. Ethical approval was obtained from the UK National Research Ethics Committee. All patients gave written, informed consent, according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients received a 5-7 day pre-phase of dexamethasone 6mg/m2/day followed by 2 sequential courses of induction therapy, termed induction phase 1 and induction phase 2, respectively. Patients with precursor B lineage ALL (pre-B ALL) were randomised to receive chemotherapy alone or chemotherapy plus 4 doses of rituximab given on day (D) 3, 10 17 and 24 of PEG-ASP 1000 IU/m2 on D4 and D18, daunorubicin 60mg/m2 and vincristine 1.4mg/m2 (2mg max) on D1,8,15 and 21, dexamethasone 10mg/m2 D1,-4, 8-11,15-18 and a single 12.5mg intrathecal methotrexate dose on D14. Patients with Ph chromosome positive (Ph+) disease received continuous oral imatinib from D1, starting at 400mg and escalating to 600mg given daily throughout induction. Anti bacterial, anti-viral and antifungal prophylaxis was mandated, but centres used local policy for choice of agents. G-CSF support was strongly recommended. Routine anti-thrombotic prophylaxis was suggested but not mandated for all patients with platelet counts >50 x 109/l. Anticoagulation with anti-thrombin replacement was recommended in the case of thrombosis. Routine coagulation factor replacement for laboratory-detected coagulopathy was specifically discouraged.

All patients had an initial assessment of response - including MRD response by BCR-ABL transcript monitoring or clonal immunoglobulin/T-cell receptor gene rearrangement quantification - at the end of induction phase 1, which did not affect treatment decision. Formal assessment of response to induction therapy (outside the scope of this report) was documented after phase 2 induction,

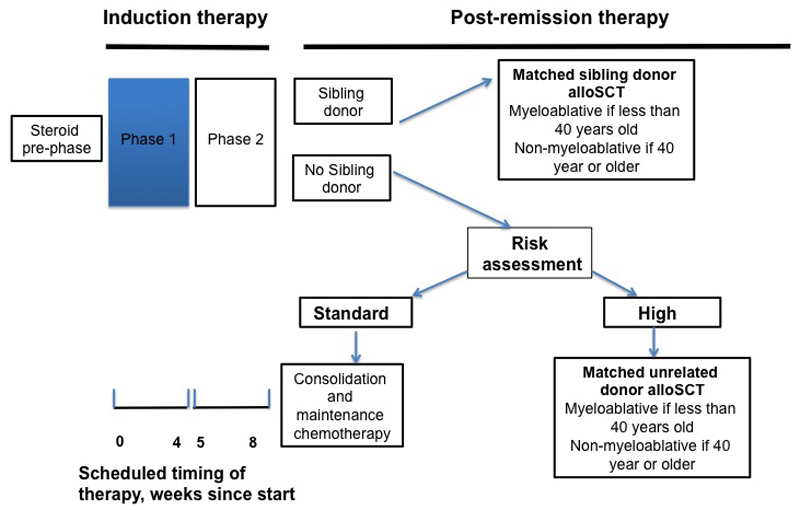

A simplified schema of the remainder or UKALL 14 treatment is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic of UKALL 14 treatment protocol.

*High risk by karyotypes: t(9;22) t(4;11), low hypodiploidy near triploidy or complex, age >40 years WBC ≥ 30 x 109/L (pre B-ALL), ≥100 x 109/L (T-ALL), Molecular Minimal Residual Disease positivity (> 1 x 10-4) after induction phase 2

Causality assessment for toxicity and death

The standard CTCAE reporting system (http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm) was used. Causality of events was attributed, as is standard practice, by both the local site PI and the central study clinical team. Additional detailed questionnaires and PIs narratives were received for all induction deaths allowing a more detailed analysis of individual events.

PEG-ASP Antibody Assays

Antibodies against PEG-ASP (IgG and IgE) were measured by two indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, which detected anti-PEG-ASP and non-pegylated Anti-E.Coli (non-pegylated Asparaginase). Seroconversion was reported with positivity in at least one assay with a clearly negative pre-dose sample. Anti-asparaginase antibody ratio over negative control more than 1.1 was used to define positivity.

Serum asparaginase activity by MAAT testing

PEG ASP enzyme activity was quantified in sera using the MAAT7 assay. Therapeutic enzyme levels were defined as >100 IU/L.

Statistical analysis

Induction phase 1 treatment-related death was defined as any death occurring before the start of phase 2 induction where the cause of death was not primarily attributable to progressive ALL. Logistic regression was used to examine risk potential factors for induction death and grade 3/4 adverse events. Factors with a conservative p<0.2 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariable analyses. All analyses were conducted using Stata 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Non-fatal grade III-IV adverse events causally related to PEG-ASP included were those classified as probably or definitely related. All adverse events were graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0.

Results

Patient characteristics

Ninety-one eligible patients (from 37 centres) were enrolled onto UKALL 14 between 30th December 2010 and 19th April 2012. One patient died before starting any treatment and has been excluded from all analyses. Patient characteristics at diagnosis are summarised in Table 1. The majority (59 of 90, 66%) of patients were over 40 years of age and nearly a third (26/90, 29%) had Ph+ ALL. Most patients (92%) had performance scores of 0-1 at diagnosis. Median follow up was 36.0 months (12 days – 50.4 months).

Table 1. Patient characteristics at diagnosis.

| Characteristic | N(%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Lineage | B-precursor | 77 (86) |

| T-cell | 13 (14) | |

| Sex | Male | 48 (53) |

| Female | 42 (47) | |

| Age at entry (years) | Median (range) | 46.50 (25 - 65) |

| ≥55 | 29 (32) | |

| ≥41 | 59 (66) | |

| Presenting WBC (x109/l) | Median (range) | 9.26 (0.52 - 297.4) |

| <30 | 62 (69) | |

| 30-99.9 | 15 (17) | |

| 100+ | 13 (14) | |

| Cytogenetic risk status | *High risk | 28 (31) |

| Low risk | 42 (47) | |

| **Unknown | 20 (22) | |

| t(9;22) | Absent | 64 (71) |

| Present | 26 (29) | |

| Low hypodiploidy/near triploidy | Absent | 65 (72) |

| Present | 4 (4) | |

| Failed/missing | 21 (23) | |

| t(4;11) | Absent | 75 (83) |

| Present | 7 ( 8) | |

| Failed/missing | 8 (9) | |

| Complex karyotype | Absent | 64 (71) |

| Present | 5 (6) | |

| Failed/missing | 21 (23) | |

| )Performance status | 0 | 55 (61) |

| 1 | 28 (31) | |

| 2 | 5 ( 6) | |

| 3 | 1 (1) | |

| Missing | 1 (1) | |

| BMI | Normal/underweight*** | 31 (34) |

| Overweight | 25 (28) | |

| Obese | 34 (38) | |

High risk: t(9;22), t(4;11) low hypodiploidy/near triploidy or complex karyotypes

No high risk factors and at least one risk factor is missing or failed

30 in the normal range and 1 patient with a BMI of 17.

Induction deaths

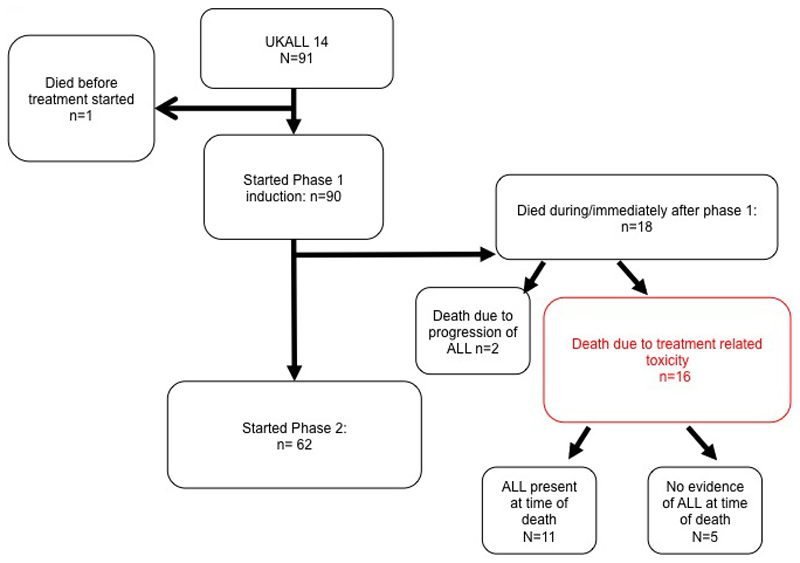

Progress through the induction therapy blocks is shown in Figure 2. Among those commencing phase 1 induction therapy (n=90) there were 18 early deaths. Two patients died of progressive ALL and the other 16 (16/90, 18%) deaths were related to induction treatment, occurring at a median time from start to induction death of 23 days (range 10-53).

Figure 2. Flow chart of progress of the 91 patients enrolled.

*Grade 4 sepsis n=4, Grade IV organ toxicity n= 4 (hepatotoxicity n= 1, pancreatitis n=1, hepatotoxicity plus neurological event n =1, hepatotoxicity plus thromboembolism together with sepsis n =1 and wrong diagnosis n=1, withdrawal of consent, n =1.

The causes of induction deaths are summarised in table 2. In 12 of 16 (75%), the causes of death were most often multifactorial; sepsis together with hepatotoxicity occurred in 8 of 16, 50.0%. Neutropenic sepsis alone occurred in 3 of 16 patients, (18.8%). A causative organism was identified in 11 of the cases of sepsis, with a gram-negative bacterial infection being responsible in 8 of those. Additional causes of death were: hepatotoxicity plus bowel ischemia (n=2,), acute coronary syndrome plus neutropenic sepsis (n=1), hepatotoxicity plus pancreatitis (n=1) and pulmonary haemorrhage (n=1). Nine of 11 hepatotoxicity-associated induction deaths were associated with grades 3-4 hyperbilirubinaemia. In total, half of the induction deaths were accompanied by recognised PEG-ASP toxicities (namely those already listed in the Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) as occurring in 1:1000 or more patients, or pancreatitis; less common, but clearly recognised as being related to PEG-ASP). There was no obvious association between baseline comorbidities and induction death.

Table 2. Summary of deaths during induction.

| ID | Patient Details | Comorbidities | Hepatotoxicity (grade) | Neutropenic sepsis (organism) | Haemorrhage (site) | Thrombosis/Visceral ischaemia (site) | Pancreatitis | Other | PEG ASP doses | Days from last PEG-ASP dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1003 | Age 54 PH - | Liver cirrhosis | 4 | Not known | D4 & 18 | 19 | ||||

| 1004 | Age 46 PH+ | None | Pseudomonas . Aeruginosa | Acute coronary Syndrome | D4 | 16 | ||||

| 1011 | Age 43 PH+ | None | 4 | Escherichia.Coli | Renal Failure | D4 & 18 | 8 | |||

| 1021 | Age 65 PH- | None | 4 | Pseudomonas . Aeruginosa | Gastrointestinal | D4 | 50 | |||

| 1026 | Age 64 PH + | Depression | 4 | Pseudomonas . Aeruginosa | D4 | 20 | ||||

| 1028 | Age 38 PH + | None | Enterococcus Faecium | D4 | 15 | |||||

| 1029 | Age 60 PH+ | IHD | 4 | Escherichia.Coli | D4 | 14 | ||||

| 1030 | Age 49 PH+ | None | Pulmonary | D4 | 6 | |||||

| 1039 | Age 62 PH+ | None | 2 | Small bowel | D4 | 10 | ||||

| 1043 | Age 63 PH- | Grade 4 renal failure | 4 | Klebsiella. Pheumoniae | Carotid artery puncture site | D4 & D18 | 43 | |||

| 1049 | Age 56 PH+ | None | 4 | Pseudomonas . Aeruginosa | D4 | 11 | ||||

| 1057 | Age: 57 PH- | None | 4 | Small bowel | D4 | 20 | ||||

| 1061 | Age: 54 PH+ | Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation | 3 | Yes | GI perforation | D4 | 10 | |||

| 1063 | Age: 62 PH+ | None | Coagulase negative staph/Enterococcus Faecium | D4 & D18 | 12 | |||||

| 1068 | Age: 64 PH+ | None | 4 | Respiratory Syncytial Virus | Renal Failure | D4 | 21 | |||

| 2007 | Age: 55 PH- | None | Pseudomonas . Aeruginosa | D4 & D18 | 8 |

All patients received D4 PEG ASP. Sixty-four, including 5 of the 16 who suffered induction deaths, received the second dose on day 18. For patients who died during induction, the median time from last dose of PEG-ASP to death was 13 days, (range 6 – 50).

Risk factors for induction death

Table 3 shows a univariate analysis of factors predictive of induction death. Age, Ph positivity and high-risk cytogenetics were all risk factors. Patients aged over 40 years had a more than 10-fold increase in risk of death during induction with Ph+ disease had a more than 8-fold increase compared to those who were Ph- (OR: 8.65 (2.61 – 28.71), p<0.001). There was no relationship to baseline albumin levels or body mass index (BMI). The data monitoring committee also confirmed that there was no relationship to rituximab randomization arm. The multivariable analysis is also shown in table 3. Although high-risk cytogenetics appeared to be associated with induction death this was driven by the presence of t(9;22), so this factor alone was included in the multivariable analysis. Age and Ph status remained significantly associated with induction death; in patients who were Ph-, there were no deaths in the 21 patients aged ≤40 years and 5 in the 43 patients over 40 years. In patients with Ph+ ALL, 1 of 10 patients aged ≤40 years died compared to 10 of 16 who were over 40 years.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for induction death.

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factor | Events/n | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age |

≤40

>40 |

1/31 15/59 |

1.00 10.23 (1.28 - 81.59) |

0.03 |

18.50 (2.02 – 169.0) | 0.01 |

| Gender |

Male

Female |

8/48 8/42 |

1.00 1.18 (0.40 - 3.47) |

0.77 |

- | - |

| Baseline WBC per 10x9/l increment | 16/90 | 1.00 (0.99 - 1.01) | 0.56 | - | - | |

| Cytogenetics* |

Standard risk

High risk |

2/28 13/42 |

1.00 5.83 (1.20 - 28.29) |

0.0029 | - | - |

| Ph |

Absent

Present |

5/64 11/26 |

1.00 8.65 (2.61 - 28.71) |

<0.001 | 13.60 (3.53 – 52.36) | <0.001 |

| Base albumin (g/l) (10 unit increment) | 16/90 | 1.03 (0.40 - 2.64) | 0.95 | - | - | |

| Base bilirubin (µmol/L) (10 unit increment) | 16/90 | 0.91 (0.59 - 1.42) | 0.69 | - | - | |

| BMI (5 unit increment) | 16/90 | 1.29 (0.82 – 2.02) | 0.27 | - | - | |

analysed as no high risk factors vs.high risk Ph and high risk Ph+ gives HRs of : 1.86 (0.24 – 14.64) and 9.53 (1.86 – 49.91) respectively.

Adverse events during phase 1 induction therapy

Including the patients discussed above who subsequently died, 87 of 91 patients (97%) experienced a grade 3-5 adverse event (AE) during induction phase 1; among these 46 (51%) suffered one or more recognized PEG ASP toxicities; 34 had grade 3-5 AEs indicating liver dysfunction, including 22 with raised bilirubin. Other PEG ASP toxicities included pancreatitis (n=3), intracranial hemorrhage (n=1), allergic reaction (n=3), coagulation disorder (n=4) and 6 vascular events. Thirty-seven of 74 surviving patients (50.0%) experienced at least one recognised grade 3-4 PEG-ASP-related, non-fatal toxicity summarised in Table 4. Hepatotoxicity - including biochemical markers of liver dysfunction - were the most frequent PEG-ASP related toxicity (36.5%, n=27). Venous thromboembolism (4.1%, n=3), allergic reaction (4.1%, n=3) and pancreatitis (2.7%, n=2) were all reported, but were relatively uncommon. A complete line-listing of all AE/SAE as well as the subset known to be recognized toxicities of PEG-ASP from which table 4 is derived is given in supplementary table S1. Since liver toxicity was so prominent and can be a key determinant of subsequent on-time therapy delivery, an analysis of any pre-treatment factors associated with grade 3-4 hepatotoxicity was carried out. This is shown in Table 5. Older age and BMI were the only factors, which showed a significant association (OR: 2.88 (1.62 – 15.44), p=0.005, for patients >40 years compared to those ≤40 years and OR: 1.58 (1.02 – 2.44), p=0.041 for a 5 unit increase in BMI).

Table 4. Patients who did not die during induction: summary of the grade 3/4 AEs recognised in SPC as being related to PEG-ASP *.

| SOC/event term | Grade 3+ Peg Asp known AEs | |

|---|---|---|

| N(%) | ||

| Gastrointestinal Disorders | 2 (3) | |

| Pancreatitis | 2 (3) | |

| Hepatobiliary Disorders | 3 (4) | |

| Liver Failure | 1 (1) | |

| Liver Dysfunction | 2 (3) | |

| Immune System Disorders | 3 (4) | |

| Allergic Reaction | 3 (4) | |

| Investigations | 29 (39) | |

| Lipase Increased | 1 (1) | |

| Serum Amylase Increased | 3 (4) | |

| Alkaline Phosphatase Increased | 15 (20) | |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase Increased | 4 (5) | |

| Blood Bilirubin Increased | 17 (23) | |

| Alanine Aminotransferase Increased | 10 (14) | |

| GGT Increased | 5 (7) | |

| Metabolism And Nutrition Disorders | 3 (4) | |

| Increased Triglycerides | 1 (1) | |

| Hypoalbuminaemia | 2 (3) | |

| Nervous System Disorders | 1 (1) | |

| Intracranial Haemorrhage | 1 (1) | |

| Vascular Disorders | 4 (5) | |

| Pulmonary Embolism | 1 (1) | |

| Thromboembolic Event | 3 (4) | |

| Non CTC AE terms: | ||

| Coagulation Disorder | 3 (4) | |

| Any liver event | 27 (36) | |

| Any Toxicity | 37 (50) | |

a complete line listing of Grade 3+ AE/SAE according to CTCAE criteria with assignment of causality by both site and by trial management group is provided in supplementary table S1.

Table 5. Analysis of risk factors for liver-related grade 3/4 adverse events during phase 1 induction in patients who did not have an induction death.

| Grade 3/4 Liver AEs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factor | Events/n | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age | ≤40 | 5/30 | 1.00 | 0.005 |

| >40 | 22/44 | 2.9 (1.62 – 15.44) | ||

| Sex | Male | 16/40 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| Female | 11/34 | 0.72 (0.28 – 1.87) | ||

| Baseline WBC per 10x9/l increment | 27/74 | 1.00 (0.99 – 1.01) | 0.71 | |

| Cytogenetics | Standard risk | 10/26 | 1.00 | 0.97 |

| High risk | 11/29 | 0.98 (0.33 – 2.91) | ||

| Ph | Absent | 20/59 | 1.00 | 0.36 |

| Present | 7/15 | 1.71 (0.54 -5.38) | ||

| Base Albumin (g/l) (10 unit increment) | 27/74 | 0.89 (0.41 – 1.92) | 0.77 | |

| Base Bilirubin (µmol/L) (10 unit increment) | 27/74 | 1.02 (0.81 – 1.30) | 0.86 | |

| BMI (5 unit increment) | 27/74 | 1.58 (1.02 – 2.44) | 0.041 | |

Asparaginase activity, anti-asparaginase antibody formation and correlation with MRD response

A trough level of asparaginase activity by MAAT testing7, 13 was assessed 14 days after the first (D4) PEG-ASP dose in 49 patients in whom serum was available (n=49). Therapeutic activity (enzyme level >100IU/l) was achieved in in 42 of 49 (86%). The median enzyme level in those achieving therapeutic enzyme levels was 234 (range 101.5 – 602.8) as compared with 44.8IU/l (0-97.5) in those with sub therapeutic levels. There was no evidence of an association between age and achievement of therapeutic enzyme level. Molecular MRD at the end of phase 1 induction - was documented in 27 patients. Molecular remission rates did not significantly differ between those achieving therapeutic enzyme levels of PEG-ASP and those who not (14/26 compared with 3/4), suggesting that an early complete molecular response in this setting is not contingent upon therapeutic asparaginase enzyme activity. Anti PEG-ASP antibody formation at day 18 was assessed in 59 patients and at that time point there were no instances of seroconversion.

Discussion

Successful achievement of CR during induction therapy for ALL is an absolute prerequisite for long-term disease-free survival. Numerous previous studies have suggested that induction regimens typically used in children give a better outcome for teenagers and younger adults than typical ‘adult’ regimens 14–18. As a consequence, there is general acceptance of testing the outcome of increasing the intensity of non-myelosuppressive agents such as PEG-ASP in regimens used for older adults.

Within the first 91 patients enrolled, we noted significantly greater induction mortality in UKALL14 than in our previous trial, UKALL12. Induction death occurred in 16 of the first 90 (17.8%) treated patients, and 15 of the first 59 (25%) participants aged over 40 (10/29 (33%) aged over 55). The median age of the patient population enrolled in this period was 46.5 years, with 29% of patients being aged over 55 years. By comparison, the induction death rate in our previous trial, UKALL12/ECOG2993, was 6% overall (ages 15-60, median age 36)12 and 15% in the 55 – 65 year old patients (median age 56)19. UKALL14 did not exclude any patient with poor organ function or co-morbidity at diagnosis, but we did not find any evidence of these factors playing a causal contribution to PEG-ASP-related mortality.

Analysis of the cause of each death in UKALL14 included a complete written narrative from the treating physician as well as the standard case report forms for serious adverse event collection. Bacterial sepsis was revealed as a major contributor to the deaths. However, concomitant grade 3-4 PEG ASP toxicities were very common among those suffering induction death, such that a recognised PEG-ASP toxicity was associated with half of the 16 induction deaths. It is impossible to disentangle the role of the investigational medicinal product (IMP) PEG-ASP from that of concomitant non-IMP induction agents. However, the introduction of dexamethasone instead of prednisolone was the only change that had been made to the standard backbone regimen between UKALL12 and UKALL14.

It is noteworthy that most of the induction deaths reported here occurred after an early, single (D4) dose of PEG-ASP, any toxicity of which would overlap with the myelosuppressive toxicity of anthracycline administered on days 1, 8, 15 and 22. The 60mg/m2 dose of anthracycline given in the UKALL12 regimen was well tolerated, but asparaginase was not started until day 17. The earlier addition of PEG-ASP-associated liver dysfunction to subsequent myelosuppression-related sepsis may have been responsible for the overlapping toxicity. The fact that sepsis was a major contributor to the mortality supports that contention.

To date, only 2 other studies reporting the use of PEG-ASP specifically in adults have been published, both of which report a lower dose and/or different schedule of anthracycline. A phase 2 trial CALGB 9511 11reported on 102 adults treated with PEG-ASP at 2000 U/m2 subcutaneously, capped at 3750 U) starting on day 5 of the 5-drug induction regimen. Although the regimen was reported to be “tolerable”, bilirubin greater than 51.3 μM (3 mg/dL) occurred in 54% of patients. CR rate was only 77% but induction deaths are not separated from induction failures within the report. There was a statistically significant difference in median age of those achieving full dose delivery and asparagine depletion - 32 years versus 48 years. In a more recent study from Douer et al 20 in 51 adults median age 32 years, upper age limit 57 years reported no deaths directly as a result of PEG-ASP in regimen, which included 2,000 IU/m2 PEG-ASP given on day 15. However, 3 of 51 (6%) died of neutropenic sepsis during consolidation. In this case, daunorubicin was given at 60 mg/m2 intravenously (IV) on days 1, 2, and 3. Grade 3 to 4 hyperbilirubinemia (1/3 patients) or transaminitis (2/3 of patients) was very common. Douer and colleagues also reported long median intervals from PEG-ASP to bilirubin recovery, which affected subsequent chemotherapy delivery. The younger median age of patients in that study, the small number receiving concurrent imatinib (N=5), a more modest anthracycline dose and different scheduling of PEG-ASP administration so as not to coincide with the maximal myelosuppression may all have contributed to the difference in toxicity.

The German Multicentre Adult ALL Group (GMALL) have reported in abstract form 21 on 1000 adult patients aged 15-55, treated on the German 07/2003 study in which a single dose of 1000 -2000U/m2 PEG-ASP was administered on day 3 during induction with a reported rate of induction death rate of less than 5% and a Grade IV hyperbilirubinaemia incidence of 16% . As with the Douer study, the younger median age (35 years) of the cohort in addition to the lower dose of anthracycline (45mg/m2 versus the 60mg/m2 used in the current study) may underpin the differences in toxicity.

It should be noted that the French GRAAALL group also reported that advancing age resulted in a higher cumulative incidence of chemotherapy-related deaths (23% v 5%, respectively; P < .001) and deaths in first CR (22% v 5%, respectively; P < .001) during “paediatric style” therapy, even when non-pegylated asparaginsae was used. In the study reported by Huguet et al22, 45 years of age and above was the strongest predictor of severe toxicity,

As a consequence of the toxicity reported here, the UKALL 14 protocol was amended to omit D4 PEG-ASP for those over 40 years of age. Furthermore, PEG-ASP was completely removed from induction treatment for all patients with Ph+ ALL. Additionally, due to the high level of sepsis related to profound myelosuppression, the daunorubicin dose was halved to 30mg /m2 on D1, 8, 15 and 22. One year following this amendment, when an additional 302 further patients had been recruited with 244 patients were assessable for induction death, a repeat analysis showed only 6 (2.5%) phase 1 induction deaths (data not shown).

Univariate analysis demonstrated that older age and poor-risk cytogenetics - including t(9;22) - were significantly associated with induction death. On multivariable analysis, age and Ph positivity remained as independent risk factors for induction death, suggesting that the concomitant imatinib therapy only received by those with Ph+ ALL may have compounded the potential for PEG-ASP toxicity. The precise mechanism by which this might occur is not known. However, from the summary of product characteristics for imatinib, ‘increased hepatic enzymes’ is reported as common (1:10 to 1:100), hyperbilirubinaemia occurs in between 1:100 and 1:1000 patients and finally, hepatic failure is noted as ‘rare’ namely occurring in between 1:1000 and 1:10,000 cases. Hence, the potential for overlapping hepatotoxicity of PEG-ASP and imatinib is clearly present.

Half of the patients who did not experience an induction death experienced one or more grade 3-4 PEG-ASP toxicities from which they eventually recovered - most commonly, hepatotoxicity. Twenty-three percent of patients in this study experienced grade 3 or greater hyperbilirubinaemia; by definition, a limitation or exclusion to further dosing with many commonly used ALL therapeutics. An analysis of treatment delays in our previous trial, UKALL12/E2993 study showed that delays of more than 4 weeks were associated with poorer OS and EFS in patients undergoing alloHCT, but not in patients undergoing post-remission chemotherapy22. Any long-term impact of any delays engendered by toxicity during initial induction therapy in this study will become clear when the trial is completed and we can evaluate any delays in relation to our primary end-point, EFS.

Our pharmacokinetic studies indicate that a single dose of 1000 IU/m2 PEG-ASP generates therapeutic enzyme levels in most patients – 86% of assessable patients had therapeutic levels of PEG-ASP activity 14 days after administration. A recent longitudinal analysis of PEG-ASP pharmacokinetics during a ‘paediatric’ regimen in adult ALL demonstrated therapeutic enzyme activity in a similar proportion of adult patients for up to 21 days20. In our study, anti-asparaginase antibodies were not seen at the early time point documented.

In conclusion we have shown that PEG-ASP achieves very effective asparagine depletion without anti-asparaginase antibody formation in the majority of adult patients. However, toxicity can be substantial in older patients, making a “paediatric-inspired” regimen of the type commonly used used in paediatric and young adult therapy difficult to deliver safely to those over the age of 40 years. Avoidance of overlapping toxicities and careful timing of administration will be of key importance to the more widespread use of this type of regimen in older adults.

Since remission can be induced with minimal mortality in patients with Ph+ ALL23, 24, we suggest that PEG-ASP is never co-administered with imatinib during induction therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

UKALL14 was funded by Cancer Research UK grant CRUK/09/006 to AKF. The MAAT testing and anti-asparaginase antibody testing was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Medac GMBH to AKF. BP was funded by Bloodwise grant 07062 to BP and AKF. We thank all centres and patients who contributed to this study.

Footnotes

Authorship Contributions

BP, AK and AKF wrote the paper. AKF designed the study, contributed data and was Chief Investigator of the trial. AK analysed data. PS, LM, SP and PP co-ordinated the study, collected data and contributed to the analysis. AD carried out the MAAT testing. CJR, TM, AMcM and DM contributed data and managed the trial. All authors contributed to writing the Ms and approved the final version.

Conflicts of interest.

AKF received a 2 year, unrestricted educational grant from Medac GMBH between 2010 and 2012

References

- 1.Sallan SE, Hitchcock-Bryan S, Gelber R, Cassady JR, Frei E, 3rd, Nathan DG. Influence of intensive asparaginase in the treatment of childhood non-T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 1983 Nov;43(11):5601–5607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avramis VI, Sencer S, Periclou AP, Sather H, Bostrom BC, Cohen LJ, et al. A randomized comparison of native Escherichia coli asparaginase and polyethylene glycol conjugated asparaginase for treatment of children with newly diagnosed standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Children's Cancer Group study. Blood. 2002 Mar 15;99(6):1986–1994. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seibel NL. Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children and adolescents: peaks and pitfalls. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008:374–380. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2008.1.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avramis VI, Spence SA. Clinical pharmacology of asparaginases in the United States: asparaginase population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) models (NONMEM) in adult and pediatric ALL patients. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007 Apr;29(4):239–247. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318047b79d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurtzberg J, Asselin B, Bernstein M, Buchanan GR, Pollock BH, Camitta BM. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. Vol. 33. United States: 2011. Polyethylene Glycol-conjugated L-asparaginase versus native L-asparaginase in combination with standard agents for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in second bone marrow relapse: a Children's Oncology Group Study (POG 8866) pp. 610–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pession A, Valsecchi MG, Masera G, Kamps WA, Magyarosy E, Rizzari C, et al. Long-term results of a randomized trial on extended use of high dose L-asparaginase for standard risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Oct 1;23(28):7161–7167. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asselin BL, Whitin JC, Coppola DJ, Rupp IP, Sallan SE, Cohen HJ. Comparative pharmacokinetic studies of three asparaginase preparations. J Clin Oncol. 1993 Sep;11(9):1780–1786. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.9.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douer D. Is asparaginase a critical component in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia? Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2008 Dec;21(4):647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douer D, Yampolsky H, Cohen LJ, Watkins K, Levine AM, Periclou AP, et al. Pharmacodynamics and safety of intravenous pegaspargase during remission induction in adults aged 55 years or younger with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2007 Apr 1;109(7):2744–2750. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-035006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stock W, Douer D, Deangelo DJ, Arellano M, Advani A, Damon L, et al. Prevention and management of asparaginase/pegasparaginase-associated toxicities in adults and older adolescents: recommendations of an expert panel. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2011 Dec;52(12):2237–53. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.596963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wetzler M, Sanford BL, Kurtzberg J, Deoliveira D, Frankel SR, Powell BL, et al. Effective asparagine depletion with pegylated asparaginase results in improved outcomes in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia -- Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study 9511. Blood. 2007 May 15;109(10):4164–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-045351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowe JM, Buck G, Burnett AK, Chopra R, Wiernik PH, Richards SM, et al. Induction therapy for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of more than 1500 patients from the international ALL trial: MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993. Blood. 2005 Dec 1;106(12):3760–3767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabry U, Korholz D, Jurgens H, Gobel U, Wahn V. Anaphylaxis to L-asparaginase during treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children--evidence of a complement-mediated mechanism. Pediatric research. 1985 Apr;19(4):400–408. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198519040-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeAngelo DJ, Stevenson KE, Dahlberg SE, Silverman LB, Couban S, Supko JG, et al. Long-term outcome of a pediatric-inspired regimen used for adults aged 18-50 years with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2015 Mar;29(3):526–534. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boissel N, Auclerc MF, Lheritier V, Perel Y, Thomas X, Leblanc T, et al. Should adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia be treated as old children or young adults? Comparison of the French FRALLE-93 and LALA-94 trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Mar 1;21(5):774–780. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Bont JM, Holt B, Dekker AW, van der Does-van den Berg A, Sonneveld P, Pieters R. Significant difference in outcome for adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on pediatric vs adult protocols in the Netherlands. Leukemia. 2004 Dec;18(12):2032–2035. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramanujachar R, Richards S, Hann I, Goldstone A, Mitchell C, Vora A, et al. Adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: outcome on UK national paediatric (ALL97) and adult (UKALLXII/E2993) trials. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007 Mar;48(3):254–261. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stock W, La M, Sanford B, Bloomfield C, Vardiman J, Gaynon P, et al. What determines the outcomes for adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on cooperative group protocols? A comparison of Children's Cancer Group and Cancer and Leukemia Group B studies. Blood. 2008 Sep 1;112(5):1646–1654. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-130237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sive JI, Buck G, Fielding A, Lazarus HM, Litzow MR, Luger S, et al. Outcomes in older adults with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL): results from the international MRC UKALL XII/ECOG2993 trial. British Journal of Haematology. 2012 May;157(4):463–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09095.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Douer D, Aldoss I, Lunning MA, Burke PW, Ramezani L, Mark L, et al. Pharmacokinetics-based integration of multiple doses of intravenous pegaspargase in a pediatric regimen for adults with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Mar 20;32(9):905–911. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goekbuget N, Baumannn A, Beck J, Bruggemann M, Diedrich H, Huettmann M, et al. PEG-Asparaginase Intensification In Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL): Significant Improvement of Outcome with Moderate Increase of Liver Toxicity In the German Multicenter Study Group for Adult ALL (GMALL) Study 07/2003. American Society of Hematology. 2010:494. Blood; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huguet F, Leguay T, Raffoux E, Thomas X, Beldjord K, Delabesse E, et al. Pediatric-inspired therapy in adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the GRAALL-2003 study. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Feb 20;27(6):911–918. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.6916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vignetti M, Fazi P, Cimino G, Martinelli G, Di Raimondo F, Ferrara F, et al. Imatinib plus steroids induces complete remissions and prolonged survival in elderly Philadelphia chromosome-positive patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia without additional chemotherapy: results of the Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell'Adulto (GIMEMA) LAL0201-B protocol. Blood. 2007 May 1;109(9):3676–3678. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-052746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foa R, Vitale A, Vignetti M, Meloni G, Guarini A, De Propris MS, et al. Dasatinib as first-line treatment for adult patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2011 Dec 15;118(25):6521–6528. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-351403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.