Abstract

The post-transcriptional addition of nucleotides to the 3′ end of RNA regulates the maturation, function, and stability of RNA species in all domains of life. Here, we show that, in flies, 3′ terminal RNA uridylation triggers the processive, 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleolytic decay via the RNase II/R enzyme CG16940, a homolog of the human Perlman syndrome exoribonuclease Dis3l2. Together with the TUTase Tailor, dmDis3l2 forms the cytoplasmic, terminal RNA uridylation-mediated processing (TRUMP) complex, that functionally cooperates in the degradation of structured RNA. RNA-immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing reveals a variety of TRUMP complex substrates, including abundant non-coding RNA, such as 5S rRNA, tRNA, snRNA, snoRNA, and the essential RNase MRP. Based on genetic and biochemical evidence we propose a key function of the TRUMP complex in the cytoplasmic quality control of RNA polymerase III transcripts. Together with high-throughput biochemical characterization of dmDis3l2 and bacterial RNase R our results imply a conserved molecular function of RNase II/R enzymes as ‘readers’ of destabilizing post-transcriptional marks – uridylation in eukaryotes and adenylation in prokaryotes – that play important roles in RNA surveillance.

Keywords: Exoribonuclease, RNA decay, Dis3l2, RNA surveillance, Uridylation

Introduction

Upon transcription, RNA species are subjected to a plethora of post-transcriptional modifications, that regulate RNA maturation, function and stability (Machnicka et al, 2013). Among these, the addition of non-templated nucleotides to the 3′ hydroxyl end of RNA (i.e. tailing) is one of the most frequent marks, exhibiting deep conservation and serving diverse molecular functions.

RNA tailing is catalyzed by a group of template-independent terminal ribonucleotidyltransferases (TNTases), containing a DNA polymerase β-like nucleotidyltransferase domain (Aravind & Koonin, 1999). Beyond the well-established canonical poly(A) polymerases that generate the poly(A) tail of eukaryotic mRNA, many non-canonical poly(A) polymerases (ncPAPases) have been described in plants, yeast and animals (Martin & Keller, 2007; Norbury, 2013). Because some ncPAPs catalyze the incorporation of uridine instead of adenine, they are also referred to as terminal uridylyltransferases (TUTases), whereas others exhibit relaxed nucleotide specificity, catalyzing both, uridylation and adenylation. The genome of flies and mammals encode seven ncPAPs, with distinct substrate specificity and subcellular localization.

Depending on organism and cellular compartment, RNA adenylation can have opposing functions: While the addition of short A-tails triggers mRNA degradation in bacteria and is associated with exosomal decay of aberrant transcripts in eukaryotic nuclei, polyadenylation increases the stability and translatability of mRNA in the cytoplasm of eukaryotes (Dreyfus & Régnier, 2002; Houseley & Tollervey, 2009).

In contrast to adenylation, uridylation only recently emerged as a widespread post-transcriptional mark associated with an expanding set of transcripts including both coding and non-coding RNA. Messenger RNA uridylation was initially observed at the 3′ ends of small RNA-directed cleavage products in plants and mammalian cells, perhaps marking these fragments for decay (Shen & Goodman, 2004). But also full length mRNA is subjected to 3′ terminal uridylation: Human replication-dependent histone mRNAs, that lack a poly(A) tail, are uridylated at the end of S phase or upon inhibition of DNA replication (Mullen & Marzluff, 2008; Su et al, 2013). Here, uridylation prompts rapid decay in both 5′-to-3′-direction by XRN1, DCP2 and LSM1, and 3′-to-5′-direction by the exosome and ERI1 (3′hExo) (Mullen & Marzluff, 2008; Hoefig et al, 2013; Slevin et al, 2014). The addition of uridine nucleotides to the 3′ end of canonical, polyadenylated mRNA was first reported in fission yeast for a small number of transcripts, which were stabilized in the absence of the TUTase Cid1 (Rissland et al, 2007; Rissland & Norbury, 2009). Because uridylation was enhanced in mutants defective of deadenylation and decapping, uridylation and deadenylation were proposed to act redundantly to induce mRNA decapping. Recent high-throughput methods for the inspection of mRNA 3′ ends at the genomic scale (TailSeq) revealed infrequent uridylation of the majority (>85%) of protein-coding transcripts in cultured mammalian cells (Chang et al, 2014). Messenger RNA-uridylation in mammals is mediated by the TUTases TUT4/ZCCHC11 and TUT7/ZCCHC6 and contributes to mRNA turnover by targeting deadenylated mRNA for decay (Lim et al, 2014). Like in mammals, mRNAs are also subjected to uridylation in plants, a modification that is predominantly introduced by the TUTase URT1 in Arabidopsis (Sement et al, 2013). However, URT1-depletion did not impact mRNA turnover, but instead prompted the accumulation of truncated, deadenylated mRNA, implying a role of uridylation in establishing 5′-to-3′-directionality of mRNA turnover. In cooperation with PABP, URT1 was subsequently proposed to contribute to the repair of deadenylated mRNA (Zuber et al, 2016). Finally, RNA uridylation also contributes to mRNA expression in kinetoplastid protists, where the insertion and deletion of uridine nucleotides edits cryptogene-transcripts to generate otherwise unstable mitochondrial mRNA (Göringer, 2012).

The addition of uridine(s) to the 3′ end of microRNAs (miRNAs) and their precursors recently emerged as a hallmark for the regulation of miRNA biogenesis and turnover in plants and animals (Ameres & Zamore, 2013; Heo & Kim, 2009). Small RNA uridylation was first observed in Arabidopsis, where the small RNA methyltransferase HEN1 protects miRNAs and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) from HESO 1-directed uridylation and degradation (Li et al, 2005; Ren et al, 2012; Zhao et al, 2012). In animals, more versatile functions of uridylation have been described: In worms and mammals, the RNA-binding protein Lin28 recruits the TUTase TUT4/ZCCHC11/PUP2 to pre-let-7, resulting in its processive uridylation (Heo et al, 2009; Hagan et al, 2009; Lehrbach et al, 2009). Pre-let-7 uridylation prevents miRNA maturation and induces degradation by Dis3l2, a 3′ uridylation triggered exoribonuclease (Chang et al, 2013; Faehnle et al, 2014). Notably, Dis3l2 is conserved in fission yeast, plants and animals and increasing evidence supports a more general role of Dis3l2 in RNA metabolism (Thomas et al, 2015; Malecki et al, 2013; Lubas et al, 2013; Łabno et al, 2016; Haas et al, 2016). In the absence of Lin28, mono-uridylation of pre-miRNAs by the TUTases TUT4/ZCCHC11 and TUT7/ZCCHC6 restores the two-nucleotide 3′ overhangs of selected pre-miRNAs to enhance maturation, a process that may be conserved in flies (Heo et al, 2012; Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015). Similar mechanisms may also contribute to the identification of defective pre-miRNAs that lack intact 3′ overhangs and trigger their destruction via the exosome in mammals (Liu et al, 2014). In flies, uridylation of pre-miRNAs by the TUTase Tailor prevents the maturation of splicing-derived mirtrons (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015; Bortolamiol-Becet et al, 2015). Tailor exhibits intrinsic specificity for RNAs ending in 3′-G (and 3′-U), facilitating the identification of mirtron-hairpin 3′ ends through the conserved splice acceptor sequence (AG-3′). In contrast, conserved Drosophila pre-miRNAs are significantly depleted in 3′ guanosine, supporting the hypothesis that hairpin uridylation may serve as a barrier for the de novo creation of microRNAs in Drosophila (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015; Bortolamiol-Becet et al, 2015). Finally, destabilization of mature miRNAs upon binding to highly complementary targets is associated with small RNA uridylation (and adenylation) in flies and mammals (Ameres et al, 2010; Xie et al, 2012).

While increasing evidence suggests broad and conserved roles of uridylation in the regulation of RNA fate and function, the molecular mechanisms, cellular targets and biological functions of RNA uridylation remain largely unexplored. Here, we report that 3′ terminal uridylation prompts 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleolytic decay in flies. We describe the molecular basis for uridylation-triggered RNA decay, revealing a novel complex that plays important roles in cytoplasmic RNA surveillance. Based on RNA-immunopurification and high-throughput sequencing we uncover putative targets in flies, providing a roadmap for the functional dissection of uridylation-triggered RNA decay. In that regard, we uncover an unexpected function of uridylation-triggered RNA decay in the quality control of RNA polymerase III transcripts. Our work provides novel insights into the targets, functional consequence and molecular reader of a conserved epitranscriptomic mark with important implications for post-transcriptional gene regulation and RNA surveillance.

Results

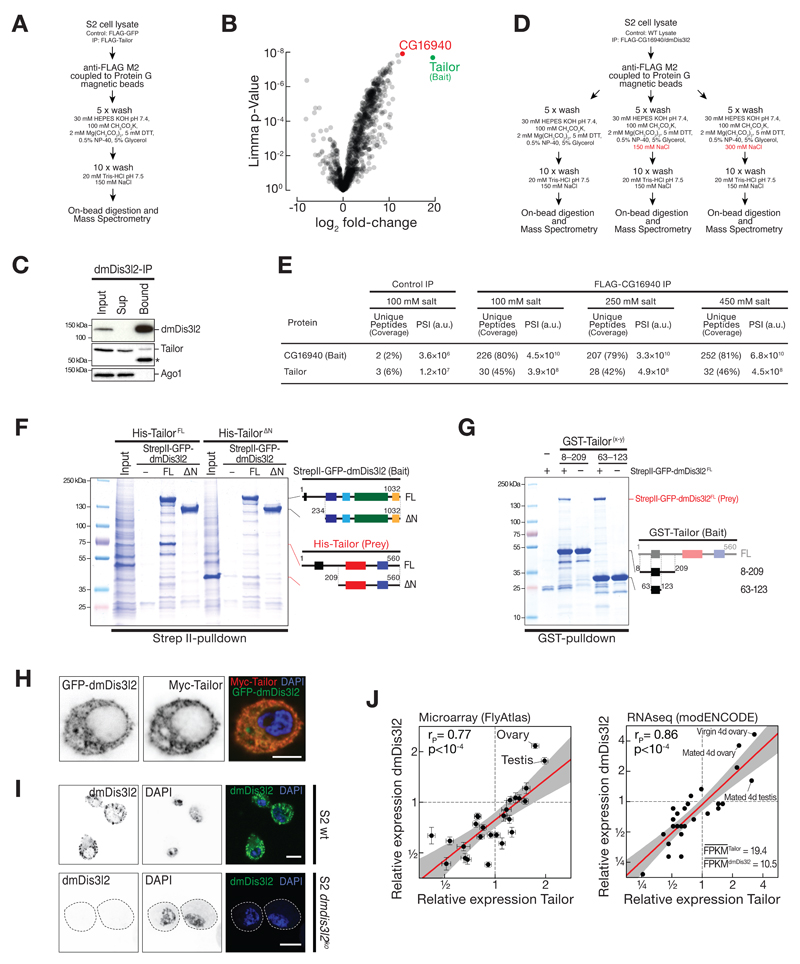

Identification of the terminal RNA uridylation-mediated processing (TRUMP) complex

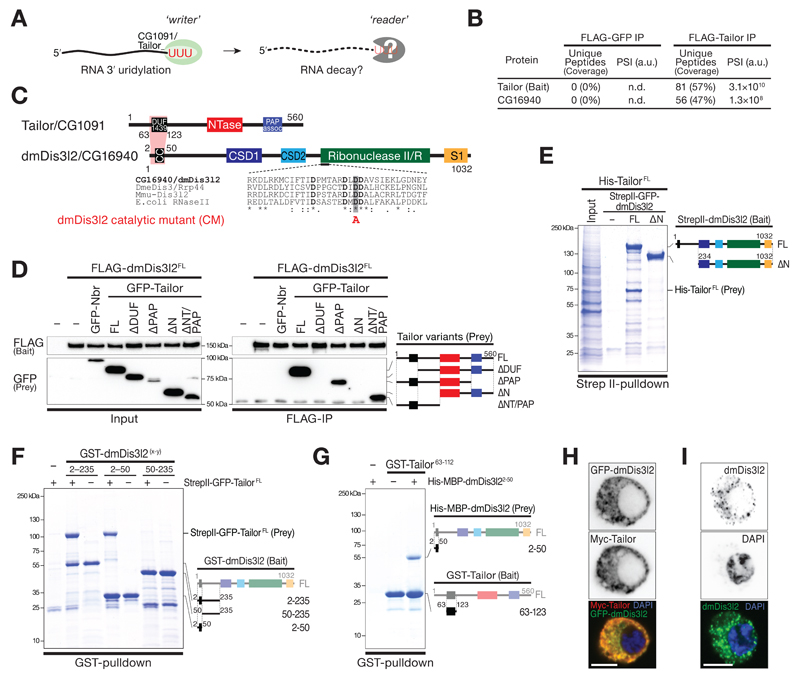

To identify putative reader(s) of Tailor-directed RNA uridylation in flies (Figure 1A) we performed immunoprecipitation of FLAG-tagged Tailor upon expression in Drosophila S2 cells, followed by mass spectrometry analysis (Figure EV1A, B, and Table EV1). As the most prominent, statistically significant interaction candidate that withstood high-salt wash steps emerged the previously uncharacterized, putative 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease CG16940 (Figure 1B, C, and EV1B, D and E). CG16940 is a homolog of the human Perlman-Syndrome exoribonuclease Dis3l2 (Astuti et al, 2012). Dis3l2 belongs to the RNase II/R enzyme family, is conserved in plants, yeast and animals, and has previously been implicated in the degradation of uridylated RNA species in fission yeast and mammals (Malecki et al, 2013; Chang et al, 2013; Lubas et al, 2013; Ustianenko et al, 2013). Because of its high overall sequence conservation, we refer to CG16940 as dmDis3l2. To validate the interaction between Tailor and dmDis3l2, we raised a monoclonal antibody against an N-terminal unstructured fragment of dmDis3l2 (amino acids 97 to 259) and performed immunoprecipitation of endogenous dmDis3l2 in lysate of Drosophila S2 cells, followed by Western blot analysis. This approach confirmed the interaction between Tailor and dmDis3l2 (Figure EV1C). Because immunodepletion of dmDis3l2 did not result in complete recovery of Tailor from the supernatant, we concluded that Tailor may exist both in a dmDis3l2-bound and -unbound state. To map the interaction between dmDis3l2 and Tailor we performed co-immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis, as well as recombinant protein-protein interaction studies: Immunoprecipitation of FLAG-dmDis3l2 recovered GFP-Tailor (but not the unrelated cytoplasmic control protein GFP-Nibbler), an interaction for which the N-terminal fragment of Tailor that encompasses the DUF1439 domain was required and sufficient (Figure 1D and EV1F and G). Systematic truncation studies on dmDis3l2 revealed a minimal interaction domain that involves a predicted coiled-coil motif close to the N-terminus (Figure 1E, F and EV1F). Recombinant short protein fragments encompassing Tailor DUF1439 domain (amino acids 63 to 123) and the N-terminal coiled-coil motif in dmDis3l2 (amino acids 2-50) were sufficient to recapitulate this interaction (Figure 1G, EV1G), revealing a minimal protein-protein interaction domain in Tailor and dmDis3l2 underlying complex formation.

Figure 1. Identification of the terminal RNA uridylation-mediated processing (TRUMP) complex.

A Model for uridylation-triggered RNA decay. 3′ terminal uridylation by the TUTase Tailor may trigger the degradation of RNA species by unknown reader enzyme(s).

B Protein interaction analysis by Nano LC-MS. Unique peptide counts and protein sequence coverage, as well as signal intensities (PSI) for Tailor (bait) and CG16940/dmDis3l2 in control IP (FLAG-GFP) and FLAG-Tailor IP are indicated. A.u., arbitrary units.

C Protein domain architecture of Tailor/CG1091 and dmDis3l2/CG16940. DUF1439, domain of unknown function; NTase, nucleotidyltransferase; PAP assoc, poly(A) polymerase associated; CC, predicted coiled-coil motif; CSD, cold-shock domain; S1, RNA binding domain;

D Co-immunoprecipitation of FLAG-dmDis3l2 (bait) and GFP-Tailor full-length and truncations expressed in Drosophila S2 cells. GFP-Nibbler (Nbr) served as negative control. Domain architecture of GFP-Tailor truncations are indicated.

E to G Recombinant protein interaction analysis using the indicated epitope tags and purification methods. Domain architecture of bait and prey are indicated.

H and I Immunostaining and imaging of Myc-Tailor and GFP-dmDis3l2 (H) or endogenous dmDis3l2 (I) in S2 cells. Single color channel images show total inversions. Scale bar = 5 µm.

Co-expression of epitope-tagged Tailor and dmDis3l2 in S2 cells revealed predominant – if not exclusive – localization of both proteins dispersed throughout the cytoplasm, without detectable signal in the nucleus (Figure 1H and EV1H). The overall cytoplasmic localization of dmDis3l2 was confirmed by immunofluorescence analyses using the monoclonal antibody against dmDis3l2, resulting in a cytoplasmic signal that was lost upon depletion of dmDis3l2 (Figure 1I and EV1I). Together with the fact that both factors exhibit significant co-expression across tissues in Drosophila (Pearson’s correlation coefficient r>0.7, p<10-4, Figure EV1J), we concluded that Tailor and dmDis3l2 form a stable, cytoplasmic, and co-regulated protein complex in flies, which we refer to as the terminal RNA uridylation-mediated processing (TRUMP) complex.

CG16940/dmDis3l2 is a uridylation-triggered 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease

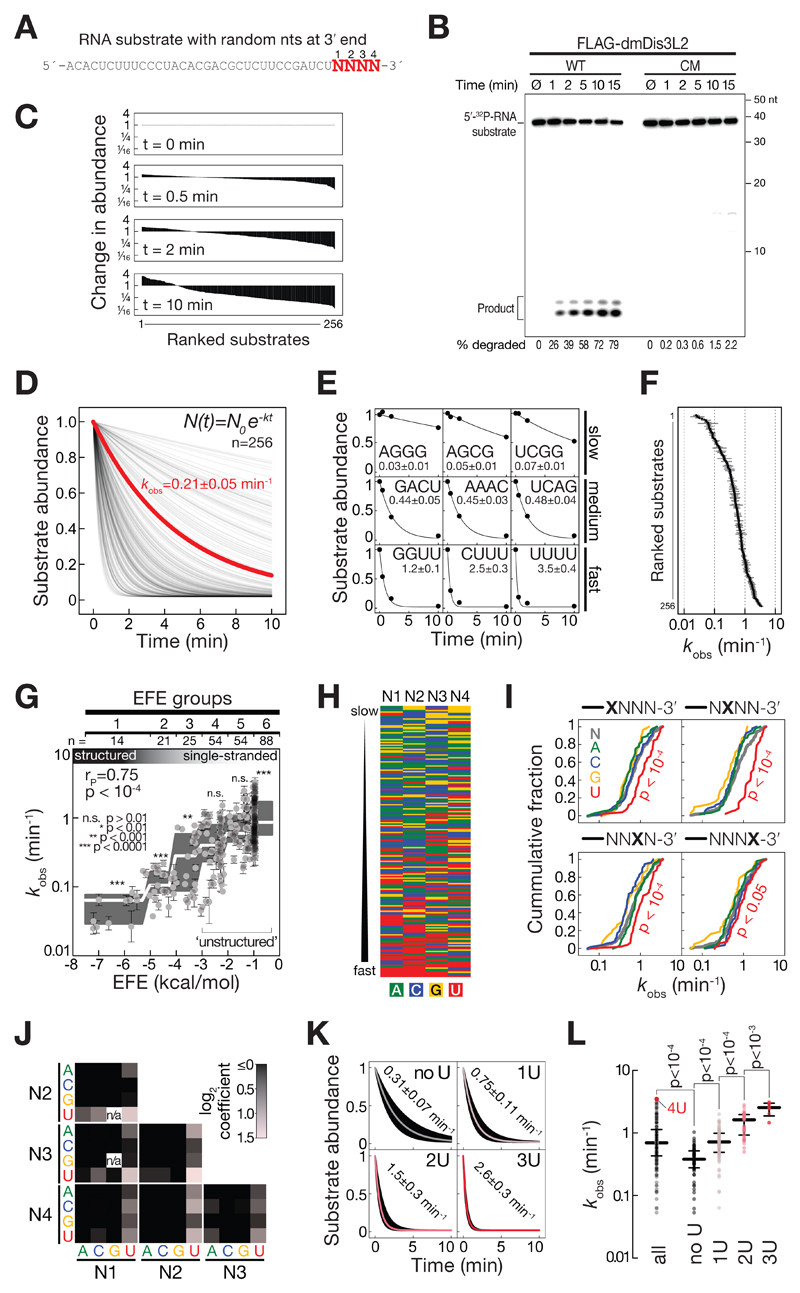

For biochemical characterization we immunopurified FLAG-tagged dmDis3l2 upon expression in S2 cells and confirmed enzyme purity by Western blot analysis (Appendix Figure S1A). DmDis3l2 rapidly degraded a 37-nt, 5′ radiolabeled RNA substrate without detectable decay intermediates (Figure 2A and B). This activity was abolished when one of four highly conserved aspartic acid residues within the RNase II/R domain that constitute the predicted catalytic site was replaced with alanine (Figure 1C and 2B). Together with the conserved domain architecture, we concluded that dmDis3l2 is a bona-fide 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease. DmDis3l2-directed RNA degradation was consistent with the previously proposed molecular mechanism for RNase II/R enzymes, which involves the Mg2+-dependent nucleophilic attack of phosphodiester bonds (Frazão et al, 2006; Faehnle et al, 2014), because EDTA inhibited, while excess Mg2+ rescued the degradation activity of dmDis3l2 (Appendix Figure S1B).

Figure 2. DmDis3l2/CG16940 is a 3′ terminal-uridylation-triggered, processive 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease.

A Sequence of RNA substrate used for in vitro exoribonuclease assays. N, randomized nucleotide.

B In vitro exoribonuclease assay using 5′ radiolabeled RNA substrate and immunopurified wild-type (WT) or catalytic mutant (CM) FLAG-dmDis3l2 (mutation indicated in Figure 1C), incubated for the indicated time and separated on a 15 % polyacrylamide gel followed by phosphorimaging. Quantification of degraded substrate in percent is indicated.

C Change in abundance of 256 different substrate RNAs as determined by high-throughput sequencing of substrates in experiment shown in (B).

D Decay rates of 256 different substrate RNAs. Data shown in (C) was normalized to overall decrease in substrate abundance as determined by phosphorimaging (as shown in B) and fit to the indicated model for exponential decay. Apparent decay rate of all substrates, as determined by phosphorimaging is indicated in red.

E Selected examples for individual substrates shown in (D). Values report the observed decay rate (kobs) in min-1.

F Overview of decay rates (kobs) of all 256 different substrate RNAs, as determined in (D). Error represents SEM of curve fit.

G Impact of RNA secondary structures, as determined by RNAfold (Gruber et al, 2008), and reported as effective free energy (EFE, kcal/mol), on decay rates (kobs) are shown. Error bars represent SEM of curve fit. Grey boxes represent tukey boxplot of individual EFE groups. White line indicates median. P-Value was determined by Mann-Whitney test comparing individual EFE groups against all substrates. Unstructured substrates used for subsequent analysis are indicated (EFE groups 4 to 6).

H Nucleotide content of single-stranded RNA substrates, ranked from slow (top) to fast (bottom) decay by dmDis3l2.

I Cumulative distribution of decay rates for RNA substrates with the indicated nucleotide at each one of four randomized position at the 3′ end of the substrate RNA. P-Value was determined by Mann-Whitney test comparing individual nts against all.

J Functional coupling between two base positions within the randomized 3′ end of substrate RNA. Red squares show average increase in decay rate compared to all substrates. Black squares show no or negative effect.

K Boxplot decay rates of substrates containing no, one, two, or three uridine(s) within the randomized 3′ end of the substrate RNA. Median decay rates ± SEM of fit are indicated.

L Decay rate of all substrates, or substrates containing no, one, two, or three uridine(s) within the randomized 3′ end of the substrate RNA. Median and quartile ranges are indicated. P-values were determined by Mann-Whitney test. Substrate containing 4 uridines (4U) is indicated.

To dissect the enzymatic properties of dmDis3l2 in more detail, we developed a high-throughput biochemical assay for the characterization of 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleases. To this end we employed as a substrate a 37-nt RNA containing four random 3′ nucleotides (Figure 2A), incubated it with immunopurified dmDis3l2 for 30 sec, 2 min, and 10 min, and subjected the remaining substrate to high-throughput sequencing (Appendix Figure S1C). The randomized 3′ end of the substrate RNA enabled us to simultaneously analyze 256 different substrates, all of which were recovered at each timepoint of the assay, albeit to varying extent (Figure 2C). Upon normalization to the overall decrease in substrate abundance, as determined by denaturing gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging (Appendix Figure S1C), analysis of the resulting libraries enabled the calculation of relative degradation rates for all 256 different substrates (Figure 2D), which globally followed a single-exponential decay model (see examples in Figure 2E). The observed decay rates (kobs) differed between individual substrates by more than two orders of magnitude (Figure 2F). To dissect dmDis3l2 substrate specificities, we first determined the secondary structure stability of each substrate, binned them into effective free energy groups (EFE groups) from highly structured (group 1) to single-stranded (group 6) and tested each group for significant over- or underrepresentation in the observed decay rate (Figure 2G). (Note, that the constant region of the substrate was designed to avoid secondary structures not involving the random 3′ nucleotides.) DmDis3l2-directed decay was strongly affected by secondary structures: Structured RNAs (EFE groups 1-3) were degraded significantly slower (p < 10-3, Mann-Whitney Test), whereas single-stranded substrates were degraded significantly faster (EFE group 6, p< 10-4) compared to all substrates. We concluded that dmDis3l2 is a single-stranded RNA-specific exoribonuclease.

But even among single-stranded substrates (EFE groups 4-6) decay rates varied extensively between individual substrates (Figure 2G). Primary sequence analysis revealed that rapidly degraded single-stranded substrates were generally enriched in 3′ uridine (Figure 2H). Analysis of each individual position of the randomized four 3′ nucleotides showed that substrates containing uridine at each individual position were degraded significantly faster when compared to any other nucleotide (Figure 2I). Pairwise comparisons between individual positions revealed an additive effect of uridine content on decay-activation across all positions (Figure 2J); and grouping substrates according to increasing overall 3′ terminal U-content confirmed a steady and statistically significant increase in degradation-rates (Figure 2K and L). In fact, among all 196 single-stranded substrates the most efficiently degraded contained four terminal uridines and decayed twelve-times faster (kobs=3.5±0.4 min-1) than the median of all substrates without terminal uridines (kobs=0.3±0.1 min-1, Figure 2K and L). In summary, we concluded that dmDis3l2 is a 3′ uridylation-triggered, single-strand-specific, processive 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease.

Uridylation by Tailor primes structured RNA for dmDis3l2-directed decay

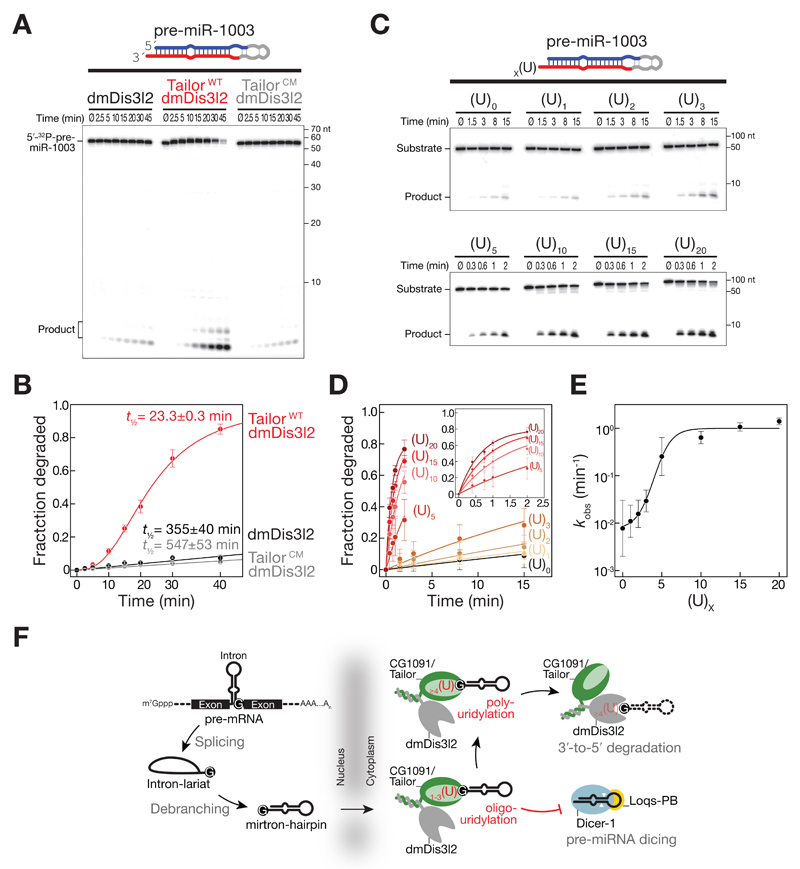

The functional characterization of dmDis3l2 implied a model in which 3′ terminal uridylation by Tailor could prime RNA substrates for 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleolytic degradation by dmDis3l2. To test this hypothesis, we employed a natural substrate of Tailor, the mirtron hairpin pre-miR-1003 (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015), and assayed degradation by immunopurified dmDis3l2 in the presence and absence of Tailor (Figure 3A and B). DmDis3l2 alone degraded synthetic, 5′ radiolabeled pre-miR-1003 inefficiently (half-life t1/2 = 355 min, Figure 3A and B), consistent with the predicted inability of sole dmDis3l2 to attack structured RNA species (Figure 2). The addition of Tailor significantly enhanced pre-miR-1003-degradation, decreasing substrate half-life by more than one order of magnitude (t1/2 = 23 min, Figure 3A and B). This decay-stimulation followed sigmoidal reaction kinetics, consistent with a model in which Tailor-directed uridylation precedes dmDis3l2-directed decay as the rate limiting step (Figure 3B). In fact, replacing one of three highly conserved aspartates in the catalytic pol β superfamily motif of Tailor with alanine abolished the enhanced decay of pre-miR-1003 by dmDis3l2 entirely, resulting in a substrate half-life similar to the one observed with dmDis3l2 alone (Figure 3A and B).

Figure 3. Uridylation-triggered RNA decay of mirtron hairpins by Tailor and dmDis3l2 in vitro.

A RNA decay assay using synthetic, 5′ radiolabeled pre-miR-1003, immunopurified dmDis3l2 and wild-type (WT) or catalytic mutant (CM) Tailor. Reactions were incubated for the indicated time and separated by 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subjected to phosphorimaging.

B Quantification of at least three independent replicates of experiment shown in A. Data represent mean ± SD. Half-life was determined by fitting data to single exponential (dmDis3l2 and dmDis3l2/TailorCM) or sigmoidal (dmDis3l2/TailorWT) reaction kinetics.

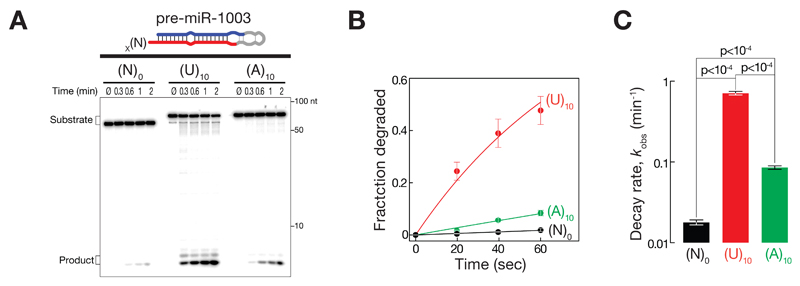

C RNA decay assay using synthetic, 5′ radiolabeled pre-miR-1003 containing the indicated number or uridine residues at the 3′ end and immunopurified dmDis3l2.

D Quantification of three independent replicates of experiment shown in C. Data represent mean ± SD. Data were fit to single exponential reaction kinetics.

E Reaction kinetics (kobs) determined in D plotted against number of 3′ terminal uridine residues. Error of fit is shown as SEM.

F Two-step-model for the regulation of mirtron hairpin maturation in Drosophila. Mirtron hairpins are generated by splicing and lariat debranching. Upon export from the nucleus, Tailor uridylates mirtron hairpins by recognizing the 3′ guanine, a hallmark of splice-acceptor sequences. Short uridylation masks the 2nt 3′ overhang required for Dicer-1 to recognize pre-miRNAs. Extended uridine-tails eventually trigger processive, 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleolytic decay by dmDis3l2, resulting in mirtron clearance.

To directly test the ability of dmDis3l2 to degrade uridylated mirtron hairpins – the products of Tailor-activity – we generated synthetic pre-miR-1003 variants that contained 3′ terminal uridine extensions of varying length and assayed degradation by sole dmDis3l2 in the absence of Tailor (Figure 3C, D and E). While the addition of one, two, or three uridine residues only mildly enhanced dmDis3l2-directed decay of pre-miR-1003 by 1.5-, 2-, and 3.8-fold, respectively, penta-uridylation resulted in 32-fold and deca-uridylation in 81-fold enhancement of degradation when compared to unmodified pre-miR-1003 (Figure 3D and E). Although the addition of 15 or 20 uridine-residues further accelerated decay, strongest increase in decay activity was observed between 3 and 10 uridine additions (Figure 3E), suggesting that short U-tails are sufficient for biologically meaningful enhancement of dmDis3l2-directed decay. Notably, degradation of uridylated mirtron-hairpins in vitro by dmDis3l2 proceeded without visible decay intermediates, implying that dmDis3l2 degrades even highly structured RNA species processively once it encounters a uridine-rich, single-stranded 3′ extension of sufficient length that can prime decay.

Our data shows that uridylation can prime the decay of structured RNA substrate, which – if not uridylated – serve as poor substrates for dmDis3l2-directed decay (Figure 2), presumably because uridylation provides a single-stranded entry-point for the initiation of degradation. To test if a single-stranded extension is sufficient for the initiation of degradation irrespective of its nucleotide composition we compared decay rates of pre-miR-1003 variants that contain an (A)10 or a (U)10 extension (Figure EV2). While deca-adenylation enhanced the degradation of pre-miR-1003 merely by 4.8-fold, a uridine-tail of similar length was 8.3-times more efficient in triggering dmDis3l2-directed decay, resulting in a 40-fold increase in decay rates compared to untailed pre-miR-1003 (Figure EV2). We concluded that primary sequence composition of Tailor-directed tailing is the major criterion that prompts the degradation of structured RNA by dmDis3l2.

Together, our data is consistent with a two-step mechanism for the inhibition of mirtron maturation by uridylation in flies (Figure 3F): (1) Initial addition of short uridine tails masks the 2-nt 3′ overhang, with immediate impairment in Dicer-mediated processing (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015). (2) Further extension of U-tails ultimately prompts the processive, 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleolytic decay of uridylated mirtron hairpins by dmDis3l2, causing their final clearance. Notably, this model is supported by the fact that in the absence of Tailor, not only mature mirtrons, but also their precursor-hairpins accumulate (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015).

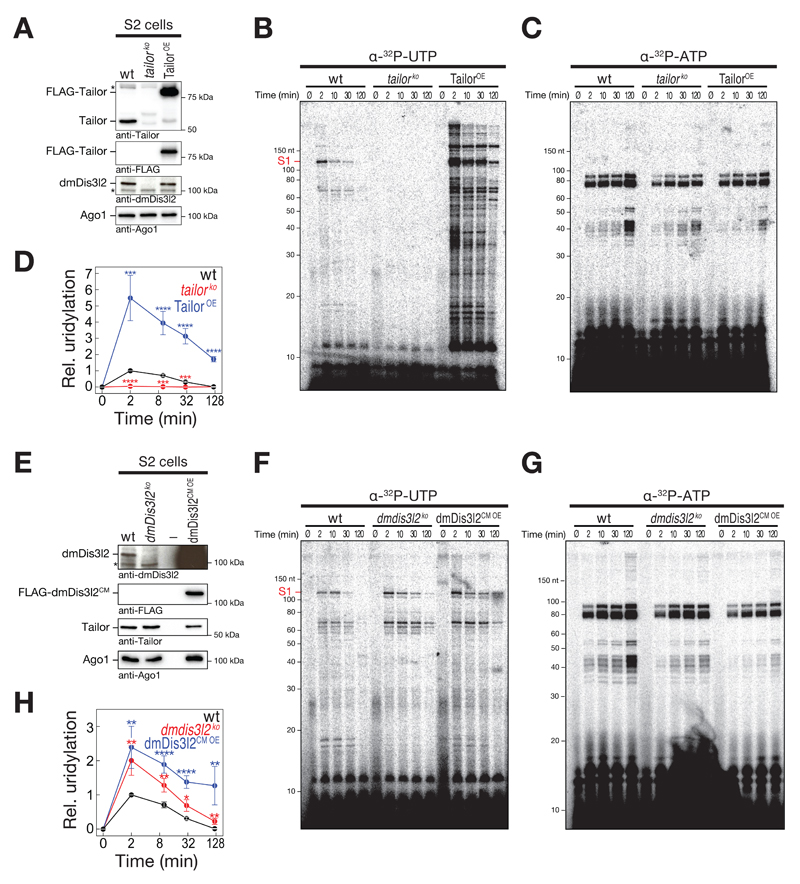

Tailor and dmDis3l2 cooperate in the degradation of cellular RNA in vitro

If and how 3′ terminal RNA uridylation contributes to general RNA metabolism in flies is unknown. To determine the extent, consequences, and genetic requirements for 3′ terminal RNA uridylation, we established a quantitative uridylation assay in Drosophila S2 cell lysate that monitors the post-transcriptional addition of uridine to cellular RNA over time using α-32P-UTP as a co-factor (Figure 4). In wild-type S2 cell lysate, we observed several RNA species undergoing uridylation as manifested by the rapid appearance of 32P-labeled RNA species of different molecular weight (wt, Figure 4B and D), an activity that was entirely absent upon depletion of Tailor by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing (tailorko, Figure 4A, B and D). (Note, that loss of Tailor results in co-depletion of dmDis3l2, indicating that dmDis3l2 protein stability depends on TRUMP complex formation.) To control for overall quality of the lysate and its general ability to recapitulate post-transcriptional RNA modifications, we simultaneously assayed adenylation, employing α-32P-ATP as a co-factor in the same experimental setup, revealing a distinct set of target RNAs (Figure 4C). Adenylation-activity was comparable in both wt and tailorko lysates (Figure 4C and Appendix Figure S2). Together with the fact that RNA uridylation patterns were significantly enhanced in lysate prepared from S2 cells overexpressing an epitope-tagged version of wild-type Tailor (TailorOE, p<0.001, Student’s t-test, Figure 4A, B and D), our data show that multiple endogenous RNA species undergo Tailor-dependent uridylation in lysate.

Figure 4. In vitro uridylation assay in S2 cell lysate recapitulates uridylation-triggered RNA decay of cellular RNA transcripts.

A and E Western blot analysis of genetically modified Drosophila S2 cells. Unmodified S2 cells (wild-type, wt), or S2 cells depleted of Tailor (tailorko) or dmDis3l2 (dmDis3l2ko) by CRISPR/Cas9 or expressing FLAG-tagged Tailor (TailorOE) or catalytic mutant dmDis3l2 (dmDis3l2cm oe) were analyzed. Antibodies are indicated. Note, that panels were assembled from two technical replicates of identical lysates (see source data).

B, C, F and G Lysate of S2 cells (as characterized in A and E) were incubated with α-32P-UTP (B and F) or α-32P-ATP (C and G) for the indicated time followed by RNA extraction, denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging.

D and H Quantification of at least five (D) or seven (H) independent replicates of experiment shown in B/C and F/G, respectively. Uridylation signal intensity for substrate S1 (indicated in B and F) was corrected for adenylation activity and normalized to wild-type 2 min time point. Data represent mean ± SEM. P-values were determined using Student’s t-test. * p<0.05, ** p<10-2, *** p<10-3, **** p<10-4.

Quantitative characterization of α-32P-UTP-incorporation signals indicated that RNA uridylation acts as a destabilizing and/or transient mark: Representative quantifications (Substrate S1, Figure 4B) revealed highest uridylation signal at early timepoints (2 min, Figure 4D), followed by a decrease in signal intensity over time (Figure 4D and Appendix Figure S2G). In contrast, adenylation-signals were consistent with a persistent, stabilizing post-transcriptional mark, resulting in statistically significant higher stability compared to uridylation (p<10-4, Figure 4C, G, and Appendix Figure S2G).

Because in vitro reconstitution assays indicated that Tailor-directed uridylation triggers dmDis3l2-mediated exoribonucleolytic degradation (Figure 3), we next tested if cellular RNA uridylation in lysate genetically interacts with dmDis3l2. To this end, we generated S2 cells depleted of dmDis3l2 by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Depletion was controlled by Western blot analysis (Figure 4E). (Note, that Tailor protein levels stayed unaltered upon depletion of dmDis3l2, consistent with our earlier observation that a fraction of the cellular Tailor-pool does not exists in complex with dmDis3l2 [Figure EV1C].) In fact, cellular RNA uridylation signals were significantly elevated across the whole timecourse in the absence of dmDis3l2 when compared to wild-type lysate (p<0.05, Student’s t-test, Figure 4F, G, and H). Similar results were obtained upon overexpression of epitope-tagged catalytic-mutant dmDis3l2 (dmDis3l2CM OE, p<0.05, Figure 4F, G, and H), indicating a dominant-negative, stabilizing function of dmDis3l2CM. Note, that even in the absence of dmDis3l2, an overall steady decrease in uridylation signatures over time indicated that uridylation might also feed into alternative RNA decay pathways (Figure 4H). In summary, we developed an in vitro assay based on Drosophila S2 cell lysate that quantitatively recapitulates post-transcriptional uridylation of cellular RNA by Tailor in whole cell lysate, a transient modification that genetically interacts with dmDis3l2.

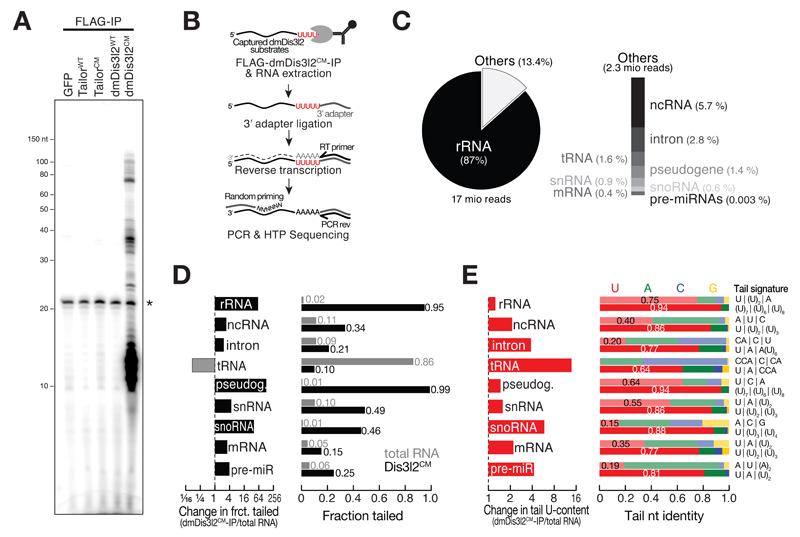

Identification of TRUMP complex-targets

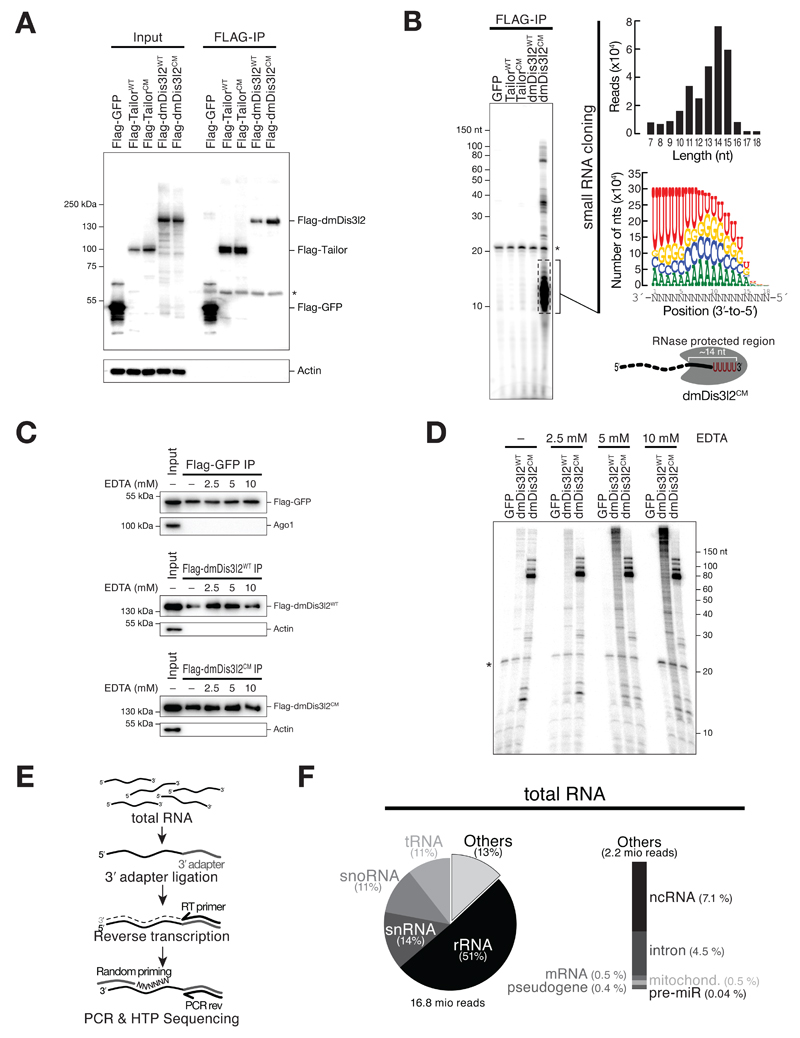

To identify TRUMP complex-substrates at the genomic scale, we expressed FLAG-tagged Tailor or dmDis3l2, as well as their catalytically inactive variants, in Drosophila S2 cells, followed by immunopurification. We reasoned that this strategy might enable co-purification of endogenous substrates for downstream identification by sequencing. To detect RNA species upon immunopurification we performed RNA extraction and dephosphorylation by treatment with calf-intestinal phosphatase, followed by radiolabeling using γ-32P-ATP and T4-polynucleotide kinase. Labeled RNA was subsequently separated on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel and detected by phosphorimaging (Figure 5A, EV3A). As negative control we included FLAG-tagged GFP, which did not co-purify with RNA, as expected (Figure 5A). We likewise did not observe any stable interaction between cellular RNA and wild-type Tailor or its catalytic mutant form, as well as wild-type dmDis3l2, indicating weak, transient, or intractable interactions between these proteins and their RNA substrates (Figure 5A). However, co-purified RNA could be readily detected upon immunopurification of a catalytic-mutant version of dmDis3l2, with strong signal intensities at a size range of 10 to 20 nt (dmeDis3l2CM, Figure 5A). Closer inspection of these RNA species by small RNA cloning and high-throughput sequencing revealed a length distribution peaking at 14 nts (Figure EV3B). This fragment size is reminiscent of the length covered by the substrate channel in a co-crystal structure of murine Dis3l2 bound to RNA (Faehnle et al, 2014). While the short length of these RNA species did not permit the identification of their genomic origin, nucleotide-content analysis revealed a high occurrence of uridine across the five 3′ terminal nucleotides (Figure EV3B). This observation suggests a model in which dmDis3l2CM binds to 3′ uridylated endogenous RNA species, that are truncated by 5′-to-3′ or endonucleolytic decay – presumably in the course of the purification process – to short fragments that reflect a footprint of dmDis3l2-substrate interaction. Consistent with this view, a penta-uridine tail is sufficient for priming degradation of a synthetic substrate by wild-type dmDis3l2, implying high-affinity binding (Figure 2). By reducing incubation time and supplementing EDTA (which prevents 5′-to-3′ RNA decay by major divalent cation-dependent cellular RNases, such as Xrn-1), we optimized dmDis3l2CM-immunopurification conditions, prompting the accumulation of higher molecular weight RNA substrates, while reducing the abundance of short, footprint RNA species (Figure EV3C and D). In order to identify full-length, dmDis3l2CM-bound substrates, we subjected immunoprecipitated RNA to 3′ adapter ligation (note, that products of Tailor-directed uridylation contain a 3′ end chemistry that is amenable to 3′ adapter ligation (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015)), followed by reverse transcription and PCR amplification using random forward priming (Figure 5B, see Materials and Methods for details). The resulting cDNA library was subjected to high-throughput sequencing in reverse-orientation, in order to assess identity and 3′ end modification status of cloned RNA species. Among 17 million analyzed reads, 87% mapped to ribosomal RNA, the vast majority of which (>90 %) stemmed from 5S rRNA loci (Figure 5C). The second most abundant substrate class mapped to non-coding RNA, consisting mostly of RNase MRP RNA (44%) and the signal recognition particle RNA 7SL (41%). Together with transfer RNA (tRNA, 1.6%), small nuclear RNA (snRNA, 0.9%), and small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA, 0.6%), the vast majority of transcripts bound by dmDis3l2CM therefore consisted of RNA polymerase III transcripts. To a lesser extent, dmDis3l2 also associated with RNA polymerase II transcripts, mapping to introns (2.8%), pseudogenes (1.4 %) and mRNA (0.4 %).

Figure 5. Identification of TRUMP complex substrates by RNA-immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing.

A Protein/RNA co-immunopurification experiments. FLAG-tagged versions of indicated proteins were expressed in S2 cells, followed by immunopurification and RNA isolation. RNA was visualized by CIP/PNK treatment using γ-32P-ATP followed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging. Star indicates non-specific contaminant.

B Overview of experimental approach to identify dmDis3l2CM-associate RNA by high-throughput sequencing. See text for details.

C Statistics of library generated from dmDis3l2CM-bound RNA upon mapping to the Drosophila melanogaster genome. rRNA, ribosomal RNA; ncRNA, non-coding RNA; tRNA, transfer RNA; snRNA, small nuclear RNA; snoRNA, small nucleolar RNA; mRNA, messenger RNA; pre-miRNA, precursor microRNA.

D Post-transcriptional modification status of RNA classes shown in C compared to total RNA, subjected to the identical cloning protocol.

E Nucleotide identity of 3′ terminal non-genome-matching additions and change in uridine-tail content for RNA classes shown in C compared to total RNA, subjected to the identical cloning protocol. Semi-transparent bars correspond to total RNA, full bars correspond to dmDis3l2CM-IP. Tail signature reports the three most abundant post-transcriptional modifications detected in the respective RNA class and cloning approach.

We next examined the 3′ terminal post-transcriptional modification status of dmDis3l2CM-bound RNA (Figure 5D and E), and compared it to steady-state, cellular total RNA, subjected to the same cloning procedure (Figure 5D and E, EV3E and F). Compared to total RNA, dmDis3l2CM-bound RNA species exhibited a higher degree of 3′ terminal post-transcriptional modifications across all classes of substrates, with up to 99 % and 95% of tailed reads in the case of pseudogenes and rRNA, respectively (Figure 5D). Closer inspection of the tail nucleotide identity in dmDis3l2CM-bound RNA revealed that post-transcriptional modifications predominantly consisted of uridines across all substrate classes (Figure 5E). The only exception to this was tRNA, which displayed a higher degree of post-transcriptional modification in total RNA (86%, Figure 5D). These modifications predominantly consisted of CCA-addition events (Figure 5E), an integral feature of bona-fide mature tRNAs. But even for tRNA, dmDis3l2CM-bound substrates were uridine tailed, albeit to a lesser extent compared to other substrates, and generally devoid of CCA-tailing signal (Figure 5E). Not surprisingly given their low expression levels compared to other dmDis3l2CM-bound non-coding RNA species, pre-miRNA hairpins represented only a minor class of dmDis3l2-substrates (0.003%, Figure 5C). Nevertheless, 13 pre-miRNAs immunopurified with dmDis3l2CM, half of which stemmed from mirtron-loci (miR-2489, miR-1006, miR-3642, miR-3654, miR-2501, and miR-1007), consistent with the proposed function of TRUMP in the degradation of uridylated mirtron hairpins.

Together, our data provide the starting point for a systematic annotation of transcripts subjected to post-transcriptional uridylation and decay via the TRUMP complex in flies.

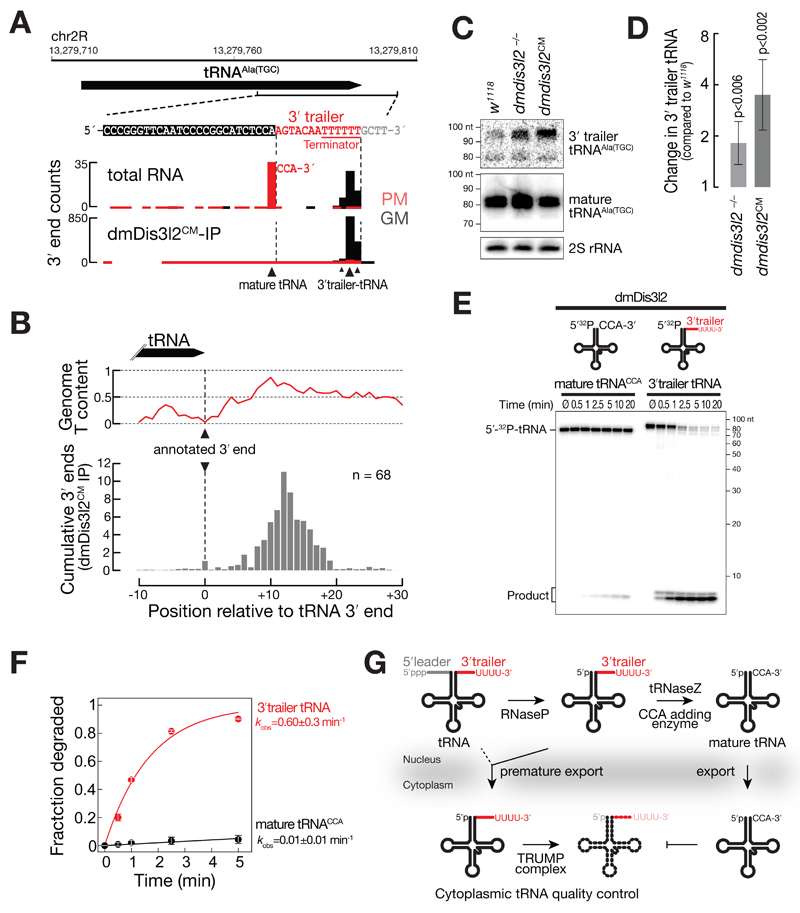

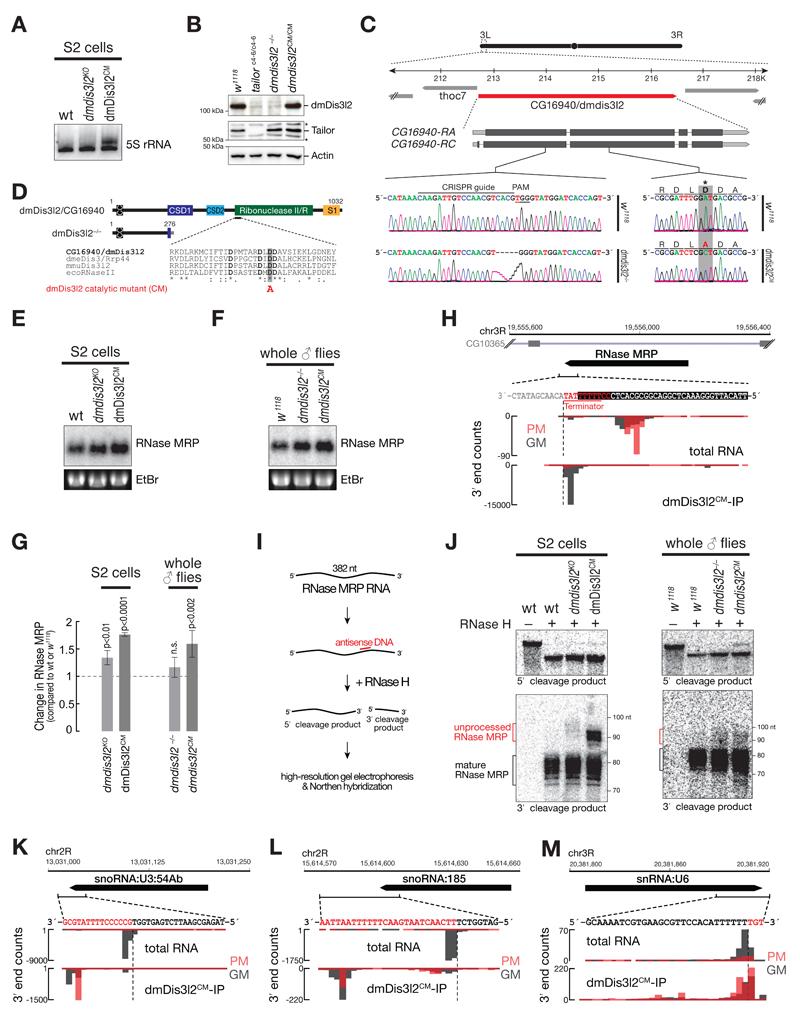

Molecular basis for TRUMP-complex-mediated quality control of RNA polymerase III transcripts

As a major feature of substrates bound by the TRUMP complex emerged RNA polymerase III products, such as 5S rRNA, RNase MRP, tRNA, snoRNA, and snRNA (Figure 5). In fact, more than 90 % of RNA bound by dmDis3l2CM could be assigned to such transcripts. To get further insights into the functional interaction between TRUMP and RNA polymerase III transcripts, we performed Northern hybridization experiments in genetically modified S2 cells and flies. We detected the appearance of a higher-molecular weight isoform for 5S rRNA, in S2 cells expressing a catalytic-inactive version of dmDis3l2, implying a role of dmDis3l2 in the decay of aberrant, unprocessed 5S rRNA transcripts (Figure EV4A). The fact that this molecular phenoptype is not detectable upon depletion of dmDis3l2 indicated compensatory, alternative routes of decay. Validation of the ncRNA substrate RNase MRP, an essential ribonucleoprotein complex implicated in rRNA processing and initiation of mitochondrial DNA replication (Esakova & Krasilnikov, 2010), revealed a significant accumulation upon depletion of dmDis3l2 (p<10-2) and expression of a catalytic mutant version of dmDis3l2 (p<10-4), confirming a role of dmDis3l2 in the degradation of RNase MRP in cultured cells (Figure EV4E and G). To confirm these data in vivo, we performed CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in flies, introducing either a frame-shift mutation into the first common exon of the dmdis3l2 locus or an amino-acid exchange mutation in the predicted catalytic site of the endogenous dmdis3l2 locus (Figure EV4 B to D). Similar to our observation in cultured cells, we also detected a significant upregulation of RNase MRP RNA in whole male flies expressing a catalytic inactive version of dmDisl32 (p<0.002, Figure EV4F and G). Further investigation revealed the accumulation of longer, apparently unprocessed isoforms of RNase MRP upon depletion of dmDis3l2 in S2 cells and in flies (Figure EV4I and J). This was even more apparent upon expression of catalytic mutant dmDis3l2 (Figure EV4J). We made similar observations for tRNA, a class of non-canonical substrates that exhibited lowest level of uridylation among all substrates (Figure 5D and E). Closer investigation of individual tRNA loci, such as tRNAAla (TGC), revealed that dmDis3l2CM-bound species did not overlap with the annotated, mature tRNA 3′ end, but instead extended ~12 nt downstream, overlapping with a U-rich region, presumably corresponding to the polymerase III terminator (Figure 6A), similar to the observations of the RNase MRP locus (Figure EV4H). DmDis3l2CM-bound species therefore corresponded to unprocessed, 3′ trailer containing, primary tRNA transcripts. In contrast, the major tRNA 3′ end in total RNA overlapped precisely with the annotated, mature tRNA, containing non-genome matching CCA-additions (prefix matching reads, PM, Figure 6A), a signal that was absent in dmDis3l2CM (Figure 6A). For a more global view, we performed meta-analysis of 68 tRNA loci (see Extended Materials and Methods for details), which were abundantly recovered in sequencing data of dmDis3l2CM-bound RNA. Across all loci, we detected strongest signal downstream of the annotated tRNA 3′ end, overlapping with high genomic thymine-content (Figure 6B). This observation supports the hypothesis that TRUMP complex targets unprocessed, 3′ trailer-containing tRNA transcripts. In fact, Northern hybridization experiments using total RNA prepared from adult male flies depleted of dmDis3l2 by CRIPSR/Cas9 genome editing revealed a significant increase in signal using a probe against the 3′ trailer region of tRNAAla(TGC) (p<0.006, Student’s t-test, Figure 6C and D). An even higher accumulation was observed for the catalytic inactive dmDis3l2 (p<0.002, Figure 6C and D).

Figure 6. The TRUMP complex targets unprocessed, 3′ trailer-containing tRNA for decay.

A 3′ end counts for the indicated locus in the Drosophila melanogaster genome, corresponding to tRNA-Alanine(TGC) in libraries generated from total RNA or dmDis3l2CM-IP. PM, prefix-matching (i.e. tailed); GM, genome-matching.

B Meta-analysis of 3′ end counts in dmDis3l2CM-IP mapping to the indicated region around the annotated 3′ end of 68 tRNA loci in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Cumulative relative distribution of 3′ end signal, relative to the annotated 3′ end, is reported (bottom). The average genome thymine (T)-content for the same regions is displayed (top).

C Northern hybridization experiment using total RNA from adult whole male flies using probes against 3′ trailer or mature tRNAAla(TGC). Wild-type flies (w1118), or flies bearing a homozygous frame-shift mutation in the first coding exon (dmDis3l2-/-) or a homozygous amino acid-exchange mutation in the catalytic site (dmDis3l2CM) in the endogenous dmdis3l2 locus in the same genetic background were used. Probes against 2S rRNA served as loading control.

D Quantification of four independent biological replicates of experiment shown in C. Data represent mean ± SD. P-Value determined by Student’s t-test.

E Exoribonuclease assay using immunopurified dmDis3l2 and in vitro transcribed, 5′ radiolabeled mature tRNA, containing a CCA modification or 3′ trailer-containing tRNA. Reactions were incubated for the indicated time and subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging.

F Quantification of three independent replicates of experiment shown in E. Data represent mean ± SD. Decay rates (kobs) ± SEM of fit were determined upon fitting to single exponential decay kinetics.

G Model for TRUMP-mediated quality control of tRNA. In the process of tRNA maturation, RNase P removes the 5′ leader and tRNase Z the 3′ trailer sequence, followed by CCA-addition and export. Premature export of unprocessed tRNA results in degradation by dmDis3l2, recognizing the uridine-rich 3′ end of the 3′ trailer, a hallmark of RNA polymerase III terminators. In contrast, mature CCA-modified tRNA is resistant against TRUMP-mediated decay.

Because unprocessed tRNA transcripts contain uridine-rich 3′ ends – the signature of RNA polymerase III-terminators – we predicted that dmDis3l2 would degrade such transcripts independent of the TUTase Tailor. To test this hypothesis, we performed in vitro RNA decay assays, using immunopurified dmDis3l2 and in vitro transcribed, 5′ radiolabeled tRNA. In fact, we observed rapid decay of 3′ trailer-containing tRNA at rates that were 60-times faster (kobs=0.6 min-1), compared to mature, CCA-modified tRNA, which remained stable throughout the duration of the assay (kobs=0.01 min-1, Figure 6E and F).

Together, our results support a role of the TRUMP complex in cytoplasmic tRNA quality control (Figure 6G): Upon premature export to the cytoplasm, unprocessed, 3′ trailer-containing tRNA are targeted for rapid decay, a process that is stimulated by uridine-rich 3′ ends, introduced through inherent features of RNA polymerase III terminators.

Together with initial observations on 5S rRNA and RNase MRP RNA, further inspection of dmDis3l2CM-bound sequences adverts to a more general function of TRUMP in the quality control of RNA polymerase III transcripts beyond tRNA, possibly also contributing to the decay of unprocessed snoRNA (i.e. snoRNA U3 and snoRNA 185, Figure EV4K and L) and mis-localized LSM-class snRNA (i.e. snRNA U6, Figure EV4M).

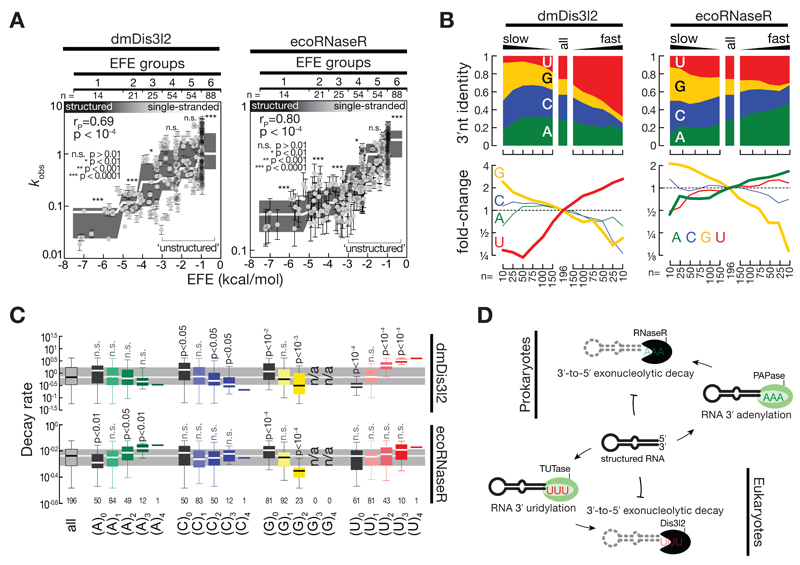

RNase II/R enzymes act as evolutionarily adapted ‘readers’ of post-transcriptional marks

The 3′ terminal post-transcriptional modification of RNA species by tailing is a deeply conserved strategy for priming 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleolytic decay. A conceptually similar system to the here described cytoplasmic uridylation-triggered RNA decay by dmDis3l2 operates in bacteria (Kushner, 2002). In this case, however, 3′ terminal adenylation – instead of uridylation – promotes degradation. For example, the homolog of dmDis3l2 in E. coli – RNase R – processively degrades 3′ adenylated RNA species in one of three major routes for exoribonucleolytic mRNA turnover in bacteria (Andrade et al, 2009; Regnier & Arraiano, 2000). We therefore tested if RNase R – like Dis3l2 in animals – acts as a direct ‘reader’ of destabilizing post-transcriptional marks. To this end, we incubated recombinant E. coli RNase R (ecoRNase R) with 5′ radiolabeled RNA substrate containing four randomized 3′terminal nucleotides (Figure 2A) for 5, 10 and 30 seconds and subjected residual substrate to high-throughput sequencing (Figure 7 and Appendix Figure S3A). Then we compared the decay rates of 256 different substrates between ecoRNase R and immunopurified dmDis3l2 (Figure 7 and Appendix Figure S3B, C and D). Similar to dmDis3l2, ecoRNase R exhibited strong susceptibility to RNA secondary structures: Structured RNAs (EFE groups 1-3) were degraded significantly slower (p<10-4, Mann-Whitney Test), whereas single-stranded substrates were degraded significantly faster (EFE group 6, p<10-4; Figure 7A). The inability to attack RNA 3′ ends that are embedded in secondary structures therefore constitutes a conserved feature of RNase II/R enzymes. Primary sequence analysis of single-stranded, unstructured substrates revealed that slowly degrading substrates exhibited an enrichment in guanosine for both dmDis3l2 and ecoRNase R (Figure 7B). (Note, that the dmDis3l2-associated terminal uridylyltransferase Tailor exhibits high uridylation activity on substrates ending in 3′ G, indicating a functional cooperativity in the conversion of RNA species into dmDis3l2-substrates (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015; Bortolamiol-Becet et al, 2015).) In contrast, rapidly degraded substrates were generally enriched in uridine for dmDis3l2, but exhibited strongest enrichment for adenine in the case of ecoRNase R (Figure 7B). Subsequent grouping of substrates according to individual nucleotide content confirmed the statistically significant, faster decay of substrates containing two (p<0.05, Mann-Whitney test) or three 3′ terminal adenines (p<0.01) for ecoRNase R, while in the absence of adenine RNA decay was significantly slower (p<0.01, Figure 7C). In contrast, increasing uridine-content did not accelerate decay significantly (Figure 7C). Also among homopolymeric 3′ ends, (A)4-substrates were degraded fastest. This observation contrasted similar analyses for dmDis3l2: Only increasing U-content had a statistically significant accelerating effect on RNA decay (p<10-4 for 3′ ends containing two or three uridine, Figure 7C); and the absence of uridine significantly decrease decay kinetics (p<10-4, Figure 7C). Taken together, our high-throughput biochemical characterization provides experimental evidence for an evolutionarily adapted function of RNaseII/R enzymes as ‘readers’ of destabilizing post-transcriptional marks – adenylation in prokaryotes and uridylation in eukaryotes (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. High-throughput biochemical comparison of E. coli RNase R and D. melanogaster Dis3l2.

A Impact of RNA secondary structures on RNA decay rates (kobs) of 256 different RNA substrates subjected to E.coli RNase R (ecoRNase R)- or Drosophila melanogaster Dis3l2 (dmDis3l2)-directed RNA decay assay as described in Figure 2. RNA secondary structures were determined by RNAfold (Gruber et al, 2008) and reported as effective free energy (EFE). Error bars represent SEM of curve fit. Grey boxes represent tukey boxplot of individual EFE groups. White line indicates median. P-Value determined by Mann-Whitney test comparing individual EFE groups against all substrates. Unstructured RNA used for subsequent analysis are indicated (EFE groups 4 to 6).

B Nucleotide content of randomized 3′ end sequence among the indicated number of substrate RNAs, ranked according to decay kinetics from slow (left) to fast (right). Fold-change in abundance for individual nucleotides is reported (bottom). Only unstructured RNA substrates (see A) were considered.

C Decay rate of the indicated number of sequences, grouped according to individual nucleotide content in the randomized 3′ end sequence. Data is represented as boxplot, outliers are not shown. P-Value reports significant differences compared to all substrates as determined by Mann-Whitney test. Grey area represents the inner quartile range and white line the median of all substrates.

D RNaseII/R enzymes act as conserved molecular ‘readers’ of destabilizing post-transcriptional modifications. In prokaryotes, e.g. E. coli, structured RNA is marked by a polyA-polymerase (PAPase) for subsequent degradation by RNaseR, 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease with intrinsic preference for 3′ adenylated RNA. In eukaryotes, e.g. flies or mammals, structured RNA undergoes 3′ terminal uridylation by a terminal uridylyltransferase (TUTase) for subsequent degradation by Dis3l2, a 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease with intrinsic preference for 3′ uridylated RNA.

Discussion

Uridylation of RNA species represents an emerging new layer in the regulation of gene expression. Here, we show that uridylation triggers RNA degradation in Drosophila. Through a series of experiments, we established the molecular basis for uridylation-triggered RNA decay in flies. We first identified the terminal RNA uridylation-mediated processing (TRUMP) complex consisting of the TUTase Tailor and the previously undescribed, bona-fide 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease CG16940/dmDis3l2 (Figure 1). Together with its ortholog Dis3/Rrp44, the core catalytic subunit of the exosome, Dis3l2 belongs to the RNase II/R family of exoribonucleases and is conserved in fission yeast, plants (aka SOV) and animals (Gallouzi & Wilusz, 2013). In contrast to Dis3, Dis3l2 lacks a N-terminal PIN-domain which mediates the association of Rrp44 with the exosome in yeast (Schneider et al, 2009). An exosome-independent function of dmDis3l2 is experimentally supported by the absence of any exosome component in our mass spectrometry data (Table EV1). Hence, our data establishes a novel and autonomous route to cytoplasmic 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleolytic decay in flies.

Tailor and dmDis3l2 stably interact through N-terminal dimerization-modules consisting of a DUF1439 domain in Tailor and a predicted coiled-coil motif in dmDis3l2 (Figure 1D-G and EV1F and G). To our knowledge this finding represents the first evidence for a direct coupling of a TUTase to exonucleolytic decay. Tailor and dmDis3l2 interact not only physically but also functionally: DmDis3l2 possesses a preference for single-stranded, 3′ uridylated RNA as determined in an unbiased assay for the biochemical characterization of 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleases (Figure 2). Uridylation-triggered decay seems to be a conserved feature of Dis3l2 enzymes, because a similar specificity has been reported for its mammalian homolog (Ustianenko et al, 2013; Faehnle et al, 2014; Chang et al, 2013). In fact, a molecular explanation for how uridylation may prompt decay by Dis3l2 has been proposed based on the crystal structure of murine Dis3l2 bound to oligouridine (Faehnle et al, 2014). Three RNA-binding domains (S1, CSD1 and CSD2) in Dis3l2 form an open funnel on one side of the catalytic domain, that navigates RNA substrates to the active site in the RNaseII/R domain, a path that is accompanied through multiple uracil-specific interactions (Faehnle et al, 2014; Lv et al, 2015).

Our data proposes a dual function of 3′ terminal uridylation: (1) The addition of uridines to single-stranded RNA significantly enhance decay kinetics, most certainly because it increases the affinity of substrates to dmDis3l2 (Figure 2) (Faehnle et al, 2014). (2) Uridylation can also prime the decay of structured RNA substrates, which – if not tailed – serve as poor substrates for dmDis3l2-directed decay (Figure 2 and 3). In this case, oligo-uridylation provides a single-stranded landing site for the initiation of 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleolytic decay. Notably, the primary sequence composition of the single-stranded RNA extension is the major criterion for the initiation of dmDis3l2-directed decay of structured RNA (Figure EV2). How exactly uridylated RNA species are handed over to dmDis3l2 upon uridylation remains to be established, but the observed sigmoidal reaction kinetics of Tailor-primed decay (Figure 3A and B), and the strong increase in observed decay rates upon penta- and deca-uridylation (Figure 3C and D) may indicate an underlying shift in relative substrate affinities.

In flies, Tailor-directed uridylation regulates the maturation of microRNA precursors, particularly mirtrons and evolutionary young miRNAs, possibly serving as a barrier for the de-novo generation of miRNAs (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015; Bortolamiol-Becet et al, 2015). Here, we expand the model for pre-miRNA regulation, by proposing a two-step model: (1) The addition of short uridine tails (i.e. mono- to tri-uridylation) masks the canonical two-nucleotide 3′ overhang of miRNA hairpins and prevents the ability of Dicer-1 to efficiently generate mature miRNAs (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015). (2) Extension of the uridine tail to 5 nts or longer ultimately initiates dmDisl32-directed processive 3′-to-5′ exonucleolytic decay, prompting the clearance of hairpins. In this regard, the regulation of miRNA maturation in flies is reminiscent of a model proposed for the regulation of let-7 maturation in mouse embryonic stem cells (Chang et al, 2013; Ustianenko et al, 2013). A major difference however lies in the targeting strategies. While uridylation in mammals is induced through recruitment of TUT4 by its RNA-binding partner protein Lin28, specificity for mirtron-uridylation in flies arises from intrinsic substrate preferences of Tailor, that targets RNAs ending in 3′G (or 3′U) (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015). Notably, the G-preference of Tailor complements the inability of dmDis3l2 to degraded even single-stranded RNA ending in G (Figure 2).

By establishing an in vitro assay for the quantitative analysis of post-transcriptional modification of cellular RNA in lysate of Drosophila S2 cells, we could show that multiple RNA species are subjected to post-transcriptional uridylation (Figure 4). This assay implies that uridylation acts as a transient, destabilizing post-transcriptional mark. In combination with genetic manipulations using CRISPR/Cas9, we find that Tailor is required for uridylation; and depletion of dmDis3l2 results in the stabilization of uridylated RNA. Our data therefore implicates the TRUMP complex as a novel player in general cellular RNA metabolism.

Through RNA immunopurification of dmDis3l2CM, followed by high-throughput sequencing, we found that a variety of transcripts, including rRNA, ncRNA, tRNA, snoRNA, snRNA, and mRNA, are subjected to uridylation in cultured Drosophila cells, albeit to varying extent (Figure 5). Our data therefore provides a roadmap for the functional dissection of uridylation-triggered RNA decay. Notably, germline mutations in DIS3L2 have been shown to cause Perlman syndrome in humans, a congenital overgrowth disorder with high neonatal mortality and predisposition to Wilms tumor (Higashimoto et al, 2013; Astuti et al, 2012). But the disease-causing molecular targets of Dis3l2 remain enigmatic. Future investigations into the substrates and consequences of uridylation-triggered RNA decay at the organismal level will certainly contribute to better understanding the molecular origin of this disease.

The identification of TRUMP-substrates revealed RNA polymerase III transcripts as major targets for uridylation-triggered decay. Using genetically modified S2 cells and flies, combined with biochemical reconstitution assays, we showed that dmDis3l2 targets aberrant, unprocessed RNA polymerase III transcripts for decay, revealing a novel, unexpected function of uridylation-triggered RNA decay in cytoplasmic RNA quality control (Figure 6). This is exemplified by tRNAs, a class of non-coding RNAs that undergo sequential processing in the nucleus, resulting in the removal of short extensions at the 5′ (5′ leader) and 3′ end (3′ trailer) of primary transcripts, followed by the addition of CCA, which ultimately undergoes aminoacylation upon export to the cytoplasm, resulting in mature tRNAs that can participate in protein synthesis (Phizicky & Hopper, 2010). The accumulation of 3′ trailer-containing transcripts in flies depleted of dmDis3l2, or genetically modified to express a catalytic mutant version, indicates a new, cytoplasmic layer of tRNA quality control, targeting unprocessed 3′ trailer containing transcripts for decay. A similar layer of quality control may be expanded to other substrates, including RNA polymerase III-transcribed snRNA and snoRNA (Figure EV4K-M). A key common feature that apparently drives decay in the cytoplasm are uridine-rich 3′ ends that represent signatures of RNA polymerase III-terminators, hence serving as a molecular identifier for decay (Figure 6). In this respect it is unclear if transcripts containing the signature of RNA polymerase III terminators actually require the activity of Tailor to initiate dmDis3l2-directed decay, since 3´ trailer-containing tRNAs are readily degraded by immunopurified dmDis3l2 in vitro in the absence of Tailor (Figure 6E and F). However, previous results showed that Tailor exhibits enhanced uridylation activity not only on RNA substrates ending in 3′G but also in 3′U (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015), indicating that extended uridylation of terminator-signature-containing transcripts might further enhance decay rates in vivo. Note, that while this manuscript was under review, two studies implicated mammalian Dis3l2 in the quality control of non-coding RNAs, providing further support to a conserved function of Dis3l2 in cytoplasmic RNA surveillance (Łabno et al, 2016; Pirouz et al, 2016).

While the TRUMP complex provides a molecular explanation for uridylation-triggered RNA decay, we currently cannot exclude that uridylation in flies may also serve a function other than prompting RNA decay. In fact, immunoprecipitation of endogenous dmDis3l2 revealed that Tailor may exist in a dmDis3l2-bound and –unbound state (Figure EV1C). In contrast, genetic evidence indicates that dmDis3l2 protein stability depends on TRUMP complex formation, because depletion of Tailor results in co-depletion of dmDis3l2 in both cultured cells and in vivo in flies (Figure 4A and EV4B). Notably, previous gain-of-function experiments indicate that Tailor can enhance the biogenesis of selected miRNAs by restoring the 2 nt 3′ overhang in miRNA precursors, a hallmark for the efficient processing by Dicer (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015). Hence, future studies are required to carefully dissect the consequences of Tailor-directed uridylation in flies, also taking possible functions other than RNA decay into account.

In terms of both function and substrates, the TRUMP complex may act as the cytoplasmic counterpart of the nuclear TRAMP complex, which prompts the exosomal degradation of aberrant transcripts in eukaryotes (Houseley & Tollervey, 2009; Schmidt & Butler, 2013). The TRAMP complex is composed of a non-canonical poly(A) polymerase Trf4 or Trf5, a zinc knuckle protein Air1 or Air2, and the RNA helicase Mtr4 and tags defective nuclear RNAs with a short poly(A) tail, ultimately resulting their degradation via the nuclear exosome, involving Rrp6 and Dis3/Rrp44 (LaCava et al, 2005; Wyers et al, 2005; Vanacova et al, 2005, Jia et al, 2011, Schmidt & Butler, 2013). However, in contrast to the TRUMP complex, exosomal degradation initiated by the TRAMP complex does not seem to involve the sequence-specific recognition of the post-transcriptional modification. Instead, the RNA helicase Mtr4 may bridge TRAMP and exosome functions by handing off transcripts directly to the exosome or Rrp6 (Weir et al, 2010; Jackson et al, 2010). Consistent with this hypothesis, TRAMP can trigger the degradation of a subset of target RNAs even in the absence of functional Trf4 and Mtr4, while others require adenylation and RNA unwinding activities, presumably promoting the productive presentation of RNA substrates to Rrp6 or the exosome (LaCava et al, 2005; Wyers et al, 2005; Callahan & Butler, 2010; Houseley et al, 2007; San Paolo et al, 2009; Rougemaille et al, 2007; Castaño et al, 1996). This is different to the situation in bacteria, where adenylation likewise promotes the decay of RNA species, such as tRNA, rRNA and mRNA (Mohanty & Kushner, 2010; Cheng & Deutscher, 2003; 2005). Among the three major 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleases in E. coli, RNase R is the only enzyme that is able to efficiently digest through regions of extensive secondary structure, while RNase II cannot and PNPase requires the assistance of the DEAD-box RNA helicase RhlB (Khemici & Carpousis, 2004; Cheng & Deutscher, 2002; 2005). In this respect, RNase R is very similar to Dis3l2 because both require a single-stranded 3′ extension as an entry site for initiation of decay that then can proceed through highly structured regions. In E. coli, this entry site is generated by PAP I, a poly(A) polymerase that adenylates mRNA, tRNA and rRNA (Mohanty & Kushner, 2010; Andrade et al, 2009). Based on high-throughput biochemical characterization we provide evidence that RNase R acts as a terminal adenylation-triggered exoribonuclease (Figure 7). Our data therefore implies a conserved molecular function of RNase II/R enzymes as ‘readers’ of destabilizing post-transcriptional marks – uridylation in eukaryotes and adenylation in prokaryotes – that play important roles in RNA surveillance.

Materials and Methods

General Methods

Total RNA from S2-S cells and whole flies was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Ambion). Stable transgenic and genetically modified Drosophila S2 cells and fly stocks were generated as described (Ameres et al, 2010; Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015). Northern hybridization experiments were performed as described previously (Han et al, 2011). Protein interaction analysis by Mass Spectrometry was performed using NanoLC-MS. A monoclonal antibody against dmDis3l2/CG16940 was generated upon expression and purification of a His-tagged N-terminal sequence of dmDis3l2/CG16940 (-PC, amino acids 97 to 259) in E. coli. Flies carrying a 5 bp frameshift mutation in the first common exon of cg16940/dmdis3l2 or a single aminoacid exchange in the catalytic site of the endogenous cg16940/dmdis3l2 locus were generated by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing and verified by Sanger Sequencing and Western blot analysis (see Figure EV4B to D). Detailed information is given in Extended Materials and Methods.

Co-immunoprecipitation

S2 cells were transiently co-transfected with pAFMW-CG16940/dmDis3l2-PC and pAGW-Tailor encoding full-length or truncated versions of Tailor or pAGW-Nibbler, followed by lysate preparation using 1 x lysis/IP buffer (30 mM HEPES-KOH pH7.4, 100 mM KAc, 2 mM MgAc, 5mM DTT, 0.5% NP-40, 5% Glycerol). Immunoprecipitation of FLAG-CG16940/dmDis3l2 was performed using mouse-anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma) coupled to Protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen), including five wash steps with 1 x lysis/IP buffer. Interaction was determined by Western blot analysis using mouse anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma) and rabbit-anti-GFP (gift from S. Dorner). For immunoprecipitation of endogenous dmDis3l2, mouse-α-dmDis3l2 was coupled to GammaBind G Sepharose (GE Healthcare).

Recombinant protein interaction studies

Recombinant proteins for Strep II pull-down experiments were expressed in insect cells using Baculovirus expression system, bound to Strep-Tactin beads and co-purified with His-tag proteins followed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. Recombinant proteins for GST pull down experiments were expressed in E. coli Rosetta II, and interaction was tested using Glutathione Sepharose 4 Fast Flow beads (GE Healthcare), followed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. For more details, see Extended Materials and Methods.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunostaining of S2 cells was performed as previously described (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015). For co-imaging of Tailor and dmDis3l2, S2 cells were transiently transfected with pAFMW-Tailor and pAGW-dmDis3l2. Anti-Myc antibody (M4439, Sigma) was used at 1:2000 dilution. Anti-dmDis3l2 was used at 1:150 dilution.

In vitro RNA decay assay

FLAG-tagged dmDis3l2 and Tailor were immunopurified upon expression in S2 cells as described previously (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015). In vitro RNA decay assays employed 10 nM 5′ radiolabelled substrate RNA and FLAG-dmDis3l2 (and if indicated Tailor) under RNAi assays conditions at 25°C (Ameres et al, 2010), but omitting the ATP-regeneration system and including 0.6 µM UTP in assays that included Tailor. RNase R (Biozym) was assayed under the same experimental conditions.

CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in S2 cells

Drosophila S2 cells were transfected with a mixture of two pAc-sgRNA-Cas9 plasmids encoding Cas9 and a sgRNAs targeting a 46 bp region in the second exon of tailor/cg1091B or a 48 bp region in the second exon of dmdis3l2/cg16940. For guide RNA sequences see Appendix Table S1. Cells were selected for transgene expression using Puromycin (5 μg/ml) for nine days, followed by serial dilution under non-selective conditions and expansion of single cell clones. Individual clones were tested for successful targeting by Surveyor assay and positive candidates were verified by Western blot analysis (Figure 4A and E).

RNA uridylation assay in S2 cell lysate

For lysate preparation, S2 cells were pelleted and washed twice in 1 x PBS. The pellet was resuspended in 2 cell pellet volumes 1 x Lysis IP buffer (30 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 100 mM KOAc, 2 mM MgOAc, 0.5 % NP40, 5 mM DTT, complete ETDA-free proteinase inhibitor cocktail [Roche]) and cells were disrupted with ~50 strokes of a Dounce homogenizer using a “B” pestle followed by centrifugation at 18,000 x g for 30 min at 4°C. Cleared lysate was normalized for protein content and assayed under RNAi conditions at 25°C using 625 nM α-32P - UTP or α-32P-ATP (3000 Ci/mmol, Perkin Elmer). Samples were taken at the indicated timepoints and reaction was stopped by adding 20 Vol 2 x PK buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, 25 mM EDTA pH8, 300 mM NaCl and 2% w/v SDS). Reactions were treated with Proteinase K at 65°C for 15 min, followed by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol-precipitation. RNA pellets were resuspended in formamide loading buffer and subjected to 15 % denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Gels were dried and exposed to storage phosphorimager screens.

RNA Library Construction

Libraries for high-throughput biochemical characterization of dmDis3l2 and ecoRNase R, and small RNA libraries were generated as previously described (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015). For dmDis3l2 substrate-identification, RNA co-immunoprecipitated with FLAG-tagged dmDis3l2 (or total RNA prepared from S2 cells as control) was subjected to 3′ adapter ligation as described previously (Reimão-Pinto et al, 2015), followed by library preparation using the QuantSeq-Flex RNA-Seq Library preparation Kit (Lexogen), according to instructions of the manufacturer.

Data Analysis

Gel images were quantified using ImageQuant TL v7.0 (GE Healthcare). Curve fitting was performed according to the integrated rate law for a first-order reaction in Prism v7.0a (GraphPad). Statistical analyses were performed in Prism 7 v7.0a (Graph Pad) or Excel v15.22 (Microsoft).

Quantitative protein interaction analysis of Mass Spec data was performed using limma (Smyth, 2005).

Bioinformatics analysis

For high-throughput characterization of dmDis3l2 and ecoRNase R substrate preferences, 3′ adapter was cut once with cutadapt (v1.2.1). The random 4mers of 3′ adapter were removed with fastx_trimmer of the fastx-toolkit (v0.0.13). Sequences with exact 4nt length were counted and the reads per million for each 4mer was calculated.

For small RNA library analysis (dmDis3l2 footprint RNA, Figure EV3B), adapter sequences were cut once with cutadapt (v1.2.1). The random 4mers on 5' and 3' were removed with fastx_trimmer of the fastx-toolkit (v0.0.13). Summary statistics (length, nt count, nt composition from end) were computed with custom scripts for the range of 7-18nt.

For analysis of libraries generated from dmDis3l2CM-bound RNA or total RNA, only the reverse run of PE50 sequencing was used. The random 4mers on the 5' were removed with fastx_trimmer of the fastx-toolkit (v0.0.13). The sequences were reverse complemented. The reads were aligned with Tailor (v1.1) with a minimal prefix match length of 18 and one mismatch allowed in the middle of the query (Chou et al, 2015). Counts were calculated with htseq-count (v0.6.1p1). The parameters were stranded=yes and “intersection-nonempty”. A GTF containing the FlyBase r5.57 annotation was used. Reads with multiple alignments were counted as their fraction to each location/feature. Feature types were summarized by following hierarchy: rRNA, tRNA, pre-miRNA, transposable_element, pseudogene, ncRNA, snoRNA, snRNA, mRNA, intron.

Extended Data

Figure EV1. Identification of the terminal RNA uridylation-mediated processing (TRUMP) complex.

A Experimental overview FLAG-Tailor co-immunoprecipitation followed by Mass spectrometry.

B Limma analysis of protein interaction candidates based on three biological replicates of experiment shown in (A). Tailor (bait) is indicated in green. The most prominent interaction candidate showing highest, and significant signal accumulation (CG16940) is shown in red.

C Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous dmDis3l2 and Tailor. dmDis3l2 was immunoprecipitated from S2 cell lysate using an antibody against endogenous dmDis3l2, followed by Western blot analysis of dmDis3l2 and Tailor. Ago1 serves as control. Asterisk indicates antibody heavy chain signal.

D Experimental overview of immunopurification using FLAG-CG16940 as bait and applying increasing salt concentrations in wash steps, followed by mass spectrometry analysis.

E Mass Spectrometry analysis of experiment shown in (D). High coverage and signal intensities of Tailor were recovered in FLAG-CG16940 IP, but not in control IP, irrespective of wash conditions.

F and G Recombinant protein interaction studies using the indicated epitope tags and purification methods. Domain architecture of bait and prey are indicated.

H and I Immunostaining and imaging of Myc-Tailor and GFP-dmDis3l2 (H) or endogenous dmDis3l2 (I) in S2 cells (H and I top panel) or S2 cells depleted of dmDis3l2 by CRISPR/Cas9 (H bottom panel). Single color channel images show total inversions. Scale bar = 5 μm.

J Relative mRNA expression levels of dmDis3l2 and Tailor in different tissues of flies. Analysis is based on published Microarray data (Fly atlas, [Chintapalli et al., 2007]) or RNA seq data(ModENCODE, [Brown et al., 2014] ).

Figure EV2. Uridylation-triggered RNA decay of mirtron hairpins by Tailor and dmDis3l2 in vitro.

A RNA decay assay using synthetic, 5´ radiolabeled pre-miR-1003 containing the indicated number of nucleotide extensions, and immunopurified dmDis3l2.

B Quantification of three independent replicates of experiment shown in A. Data represent mean±SD. Data was fit to single exponential decay kinetics.

C Decay rates (kobs) determined in (B). Error bars indicate SEM of fit. P-values were determined using Student’s t-test.

Figure EV3. Identification of TRUMP complex substrates by RNA-immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing.

A Western blot analysis associated with experiment shown in Figure 5A. Actin serves as control. Star indicates non-specific signal, corresponding to hc-antibody signal.

B Small RNA sequencing analysis. Strong RNA signal intensities between 10 and 20 nt observed for immunopurified dmDis3l2CM were gel purified and subjected to small RNA cloning (see Materials and Methods). Resulting libraries were analyzed for RNA length (top right graph) and nucleotide content (bottom right graph). Small RNAs bound to dmDis3l2CM correspond to 3´uridine-rich, RNase-protected fragments.

C Western blot analysis of FLAG-immunopurification in the presence of the indicated concentration of EDTA. Ago1 and Actin are controls.

D RNA-protein co-immunopurification experiments in the presence of the indicated concentration of EDTA. FLAG-tagged versions of indicated proteins were expressed in S2 cells, followed by immunopurification and RNA isolation. Co-immunopurified RNA was visualized by CIP/PNK treatment using γ-32P-ATP followed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging. Star indicates non-specific contaminant.

E Overview of experimental approach for S2 cell total RNA 3´ end sequencing.

F Statistics of total RNA 3´ end sequencing library generated from S2 cell total RNA following the approach described in (E). rRNA, ribosomal RNA; ncRNA, non-coding RNA; tRNA, transfer RNA; snRNA, small nuclear RNA; snoRNA, small nucleolar RNA; mRNA, messenger RNA; mitochond., mitochondrial RNA; pre-miRNA, precursor microRNA.

Figure EV4. Validation of dmDis3l2CM-bound RNA reveals unprocessed RNA pol III transcripts as targets for TRUMP-mediated decay.

A Northern hybridization experiments using total RNA derived from wild-type (wt) S2 cells, S2 cells depleted of dmDis3l2 by CRISPR/Cas9 (dmdis3l2ko), or S2 cells expressing FLAG-tagged catalytic-mutant dmDisl32 (dmDis3l2CMOE). A probe against 5S rRNA was used.

B Western blot analysis of ovary lysate derived from wild-type flies (w1118), flies depleted of Tailor (tailorc4/6) or dmDis3l2 (dmdis3l2-/-), and flies in which the endogenous dmdis3l2 locus was edited by CRISPR/Cas9 to express a catalytic inactive version of dmDis3l2 (dmdis3l2CM/CM). Levels of dmDis3l2 and Tailor were determined using monoclonal antibodies. Actin serves as loading control.

C Schematic representation of the predicted structure of dmdis3l2/cg16940 gene and RNA transcripts. The location of a 5 bp deletion introduced by CRISPR/Cas9 genome engineering in flies (dmdis3l2-/-), or a mutation introducing an amino acid exchange (D to A) at the predicted catalytic site of dmDis3l2 is indicated and confirmation by Sanger sequencing of a PCR product prepared from the locus of WT (w1118) flies and flies homozygous for dmdis3l2-/- or dmdis3l2CM/CM is shown.

D Protein domain organization of wild-type dmDis3l2 and a predicted truncation generated by the frame-shift mutation shown in (C), as well as the location of the catalytic mutation is depicted.

E Northern hybridization experiments using total RNA derived from Drosophila S2 cells. Wild-type S2 cells, cells depleted of dmDis3l2 by CRISPR/Cas9 (dmdis3l2KO), or cells expressing a catalytic mutant version of dmDis3l2 (dmDis3l2CM) were used. A probe against RNase MRP RNA was used; ethidium bromide staining serves as loading control.

F Northern hybridization experiments using total RNA derived from adult whole male flies. Wild-type (w1118) flies, flies depleted of dmDis3l2 by CRISPR/Cas9 (dmdis3l2-/-), or flies homozygous for a point mutation in the predicted catalytic site of endogenous dmdis3l2 (dmdis3l2CM) were used. A probe against RNase MRP RNA was used; ethidium bromide staining serves as loading control.

G Quantification of four independent biological replicates of experiment shown in (E) and (F). Abundance of RNase MRP RNA in the respective genetic mutant background relative to wild-type samples is reported. Values report mean±SD. p-Values were determined by Student’s t-test.

H 3´ end counts for the indicated locus in the Drosophila melanogaster genome, corresponding to RNase MRP RNA, in libraries generated from total RNA or dmDis3l2CM-IP. PM, prefix-matching (i.e. tailed); GM, genome-matching.

I Experimental approach to test 3´ end heterogeneity of RNase MRP RNA. A DNA oligonucleotide was annealed to RNase MRP RNA in total RNA followed by RNase H treatment, resulting in the endonucleolytic cleavage of the transcript. Shortening of the transcript enables to test 3´ end heterogeneity in high-resolution Northern hybridization experiments.

J Northern hybridization experiment using experimental approach described in (I). Total RNA from S2 cells or adult whole male flies of the indicated genotype were used. Probes against the 5´ (top) or 3´ cleavage product (bottom) were used. Signal corresponding to extended, unprocessed 3´ isoforms of RNase MRP RNA are indicated.

K to M 3´ end counts for the indicated loci in the Drosophila melanogaster genome, in libraries generated from total RNA or dmDis3l2CM-IP. SnoRNA:U3:54b (K), snoRNA:185 (L) and snRNA:U6 (M) are shown. PM, prefix-matching (i.e. tailed); GM, genome-matching.

Supplementary Material