Introduction

Concerns about the health effects of dietary sugars have recently taken centre stage, reflecting an emerging understanding of the importance of sugars, and particularly sugary drinks, in the development of obesity and diabetes.(1–4) Recent research estimates consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) caused approximately 80,000 excess cases of type 2 diabetes in the UK over ten years.(1) In early 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended intake of free sugars should be less than 10% of daily calories, and preferably below 5%.(5) In the UK, in July 2015, the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) halved its recommendation for free sugars to no more than 5% of daily calories.(6)

In the UK, dietary sugars (non-milk extrinsic sugars) made up approximately 15 and 12% of dietary calories among children and adults, respectively, in 2012.(7) Recently there have been calls for action to reduce sugar consumption, including voluntary industry reformulation and taxes or warning labels on sugary foods.(8–10) Earlier this year, Public Health England proposed a series of evidence-informed measures to reduce sugar consumption.(11) So far, relatively little attention has been given to important structural factors, including in agriculture, which influence sugar consumption in the UK.(12–14) However, it has long been recognised that agricultural policy, through its effect on price and availability of foods, is an important determinant of health.(12, 14–19) For sugars, the European Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has historically protected the European sucrose (sugar beet) industry through interventions that have kept commodity prices high and prevented foreign imports. For the past decade, the EU has been phasing out these protections (“liberalisation”). This process will be complete by 2017.

This article describes the effect liberalisation may have on the production, price, and addition of sugars to processed foods. The market is already reacting to these reforms, with the biggest players in the sugar industry responding by growing larger and planning to increase production. We argue this may lead to increased sugar consumption, posing a threat to public health and undermining efforts to reduce sugar consumption. The reforms may also have a disproportionate impact on those in low socioeconomic groups and so may widen health inequalities. In this article, the terms ‘sugar’ and ‘sugars’ refer to sucrose and other calorie-containing sweeteners, including high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS)(Table 1).

Table 1. Definitions for terms used in this paper.

| Sugar(s): | An umbrella term to describe all monosaccharides and disaccharides. It includes both sucrose and high fructose corn syrup. |

| Sucrose: | A white sugar typically derived from sugar beet or sugar cane. Sucrose is a disaccharide made up of 50% glucose and 50% fructose. |

| High fructose corn syrup (HFCS): | This is an alternative to sucrose often used in food manufacturing. Chemically it is very similar to sucrose, containing between 42% and 60% fructose, with the remainder being glucose. While there has been much discussion about the health effects of fructose (and HFCS that has more than 50% fructose), the recent SACN report concluded that there was insufficient evidence to demonstrate that the health effects of fructose were different compared to other sugars.(6) However its properties do make it particularly favourable to use as a food additive.(26) |

| Free sugars: | Free sugars is the preferred term for identifying sugars of health concern, and is used by both SACN and the WHO in their recent reports.(5, 6) Any sugars added to foods by the manufacturer, cook or consumer plus sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, fruit juices and fruit concentrates.(6) Free sugar does not include sugars that are within the cellular matrix of fruit and vegetables, which significantly attenuates the sharp rise in blood sugar. Moreover fruit and vegetable consumption has a positive association with cardio-metabolic health. |

| Non-milk extrinsic sugars: | This is the term that SACN used to use to identify sugars of concern in the diet. This includes all sugars not contained within the cellular structure of a food. It also excludes all sugars in milk and milk products. The only difference between non-milk extrinsic sugars and free sugars, is that the latter excludes fruit sugars found in stewed, dried or tinned fruit. |

History of the Common Agricultural Policy

CAP was enacted in 1962, when Europe was emerging from food shortages post-World War II. Its primary aims, enshrined in treaty, were to increase agricultural productivity, ensure a fair standard of living for farmers, stabilise markets, ensure availability of energy-dense food supplies, and establish reasonable consumer prices.(20) Its aims have not evolved as understanding of nutrition for health has improved and as new public health issues have emerged, including obesity and diabetes. CAP sets common rules in agriculture for all EU Member States. These have primarily been concerned with using market interventions to control the supply and price of many agricultural products (including dairy, red meats, sugar, cereals, and vegetables fats). In doing so, CAP has promoted over-production of these products, shaping European diets by in ways that may have been detrimental for public health.(15)

Sucrose has been among the most protected European agricultural products. These protections have benefitted sugar processors (manufacturers producing sugar from sugar beet), who have in turn influenced CAP sugar policies.(21) The policies consisted of a combination of import tariffs, minimum price guarantees, production quotas and export subsidies. Import tariffs effectively prevented importation of cheaper sucrose from outside Europe. Minimum price guarantees and production quotas ensured European producers were paid significantly above the world price for in-quota sucrose. Moreover, export subsidies made it profitable to produce an excess of sucrose (above quotas) and export this to other countries, even when production was costly compared to the world price. Because sucrose was so profitable, the policy soon led to over-production. CAP also maintained a production cap on HFCS of about 5% of all sugars production, affording additional protections to the European sugar beet industry by preventing large-scale replacement of sucrose with HFCS.

These policies facilitated the growth and profitability of the European sugar industry such that it now includes five of the world’s ten largest sugar producers.(21) They also ensured sucrose was the predominant sugar and that its price was kept relatively high compared to the world price.(21) In 2012, before the reforms, the European price was about €700 per tonne compared to a world price of about €400 per tonne.(22)

Liberalising the sugar sector

Initial sugar reforms in 2006 reduced the minimum price guarantee and eliminated export subsidies. One study estimated that reducing the price guarantee could lead to a 7.5% increase in SSB consumption in France.(23) Subsequent reforms, starting in 2013, go much further and will almost fully liberalise the sugar market in Europe, culminating with eliminating production quotas and minimum price guarantees in 2017. The European Commission predicted that as a result, the commodity (or wholesale) price of sugar would drop significantly, HFCS production would treble, and production of sugars overall would increase by around 15% in the decade after quotas end.(22) Early indications suggest these predictions are broadly accurate. The price of European sucrose has fallen to approximately €400 per tonne, with analysts expecting an increase of around 20% in sugar production post-2017.(24, 25) The main players in the European sugar industry are growing larger and preparing to increase production to remain competitive. For example, in May 2015 Europe’s second largest sugar producer, Tereos, purchased the sugar distribution business of a UK-based baked goods company, citing the reform as necessitating this consolidation. Tereos has also stated it will increase sugar production by 20% once quotas are abolished.(25) This reform follows on from previous CAP policies which also incentivised the growth and consolidation of the European sugar industry, which can now only remain profitable post-liberalisation by further increasing production.

What might be the unintended consequences of liberalisation on consumption of sugars?

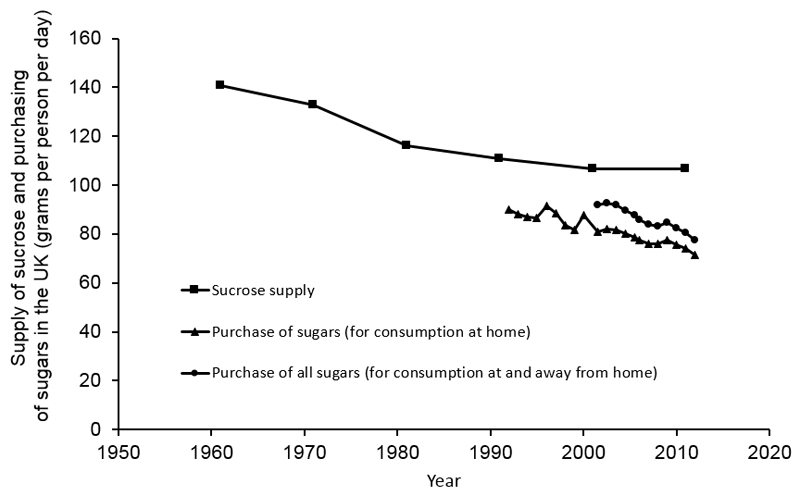

Sugar supply and consumption in the UK has declined over the last fifty years (Figure 1), but it is unclear whether this trend continued after the 2006 reforms. Evidence from France suggests the 2006 reform would lead to reduced SSB prices, contributing to increases in sugar consumption.(23) The new set of sugar reforms go much further and may be more liable to increase sugar consumption, not only through reductions in consumer food prices but also through other mechanisms.

Figure 1.

Sucrose supply is the total sugar produced in the UK plus imports minus exports from 1961 to 2011, adjusted to provide per capita estimates. Purchase of sugars (non-milk extrinsic sugars) is based on household level food purchase, adjusted to provide per capita estimates. From 1990 to 2001, purchase data are from the National Food Survey. Purchase data from 2002 to 2012 are from the Living Cost and Food Survey, formerly known as the Expenditure and Food Survey.

First, lowering the cost of sugars to food processors will make it more economically viable to incorporate sugars into processed foods as an easy, inexpensive means of increasing palatability, potentially resulting in higher sugar content in foods that already contain sugars.

Second, the price fall and the increased availability of HFCS may result in sugars being added to a broader range of foods. HFCS has a number of advantageous properties apart from sweetness, including flavour enhancement, stability, freshness, texture, pourability and consistency, and it can be used as a sweetener in both sweet foods and some savoury foods (e.g. ketchup).(26) HFCS use in Europe is relatively low at present because of the production cap, but with the restriction lifted in 2017, it will soon become feasible to produce and use.

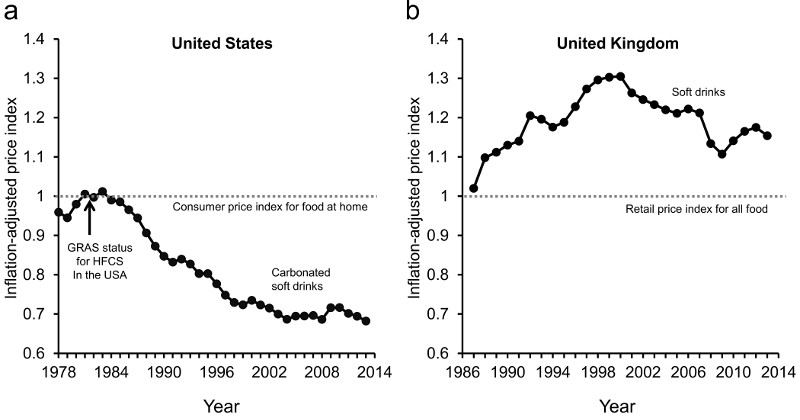

The US provides an illustrative comparison. The US government declared HFCS to be “generally recognized as safe” in 1983, removing any restraint on its use. Following this, SSB manufacturers replaced sucrose with cheaper HFCS in their beverages.(27) In the 30 years since, there has been a long-term decline in the price of carbonated soft drinks relative to food (Figure 2a). In contrast in the UK, where sucrose remained the predominant sweetener, the price of soft drinks relative to food has risen (Figure 2b). Moreover, in the US sugar consumption increased by 20% over a 15-year period after the introduction of HFCS, even though sucrose consumption declined, showing the potential effects of macro-level sugar policy on product formulation and consumption.(27) Although, because of other differences between the US and Europe, it is unclear whether Europe would see this effect to the same degree.

Figure 2.

2a United States Consumer Price Index over the years 1978 to 2013 for carbonated beverages adjusted for inflation based on the index for all food and drink at home. Baseline year for both indices set to 1978. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2b United Kingdom Retail Price Index over the years 1987 to 2013 for soft drinks adjusted for inflation based on the index for all food and drink. Baseline year for both indices set to 1987. Data from the Office of National Statistics.

Significantly cheaper sucrose and HFCS may also lead to greater marketing of foods high in sugars, as these foods will remain very profitable—and potentially more profitable than in the past. Assuring the profitability of sugars may encourage industry to resist regulations designed to reduce the use of sugars.

Third, the effects of the reforms are likely to be felt beyond Europe. It is intended that the sugar reforms will open up the world market, particularly in developing countries, for European processed food, which will become cheaper to produce as sugar prices fall. The EU Trade Commission and Defra have supported these reforms because of the opportunities they bring for the European and UK processed food industry.(21, 28) Defra has stated that ‘the boom in global demand for western-style foods is creating huge opportunities for growth in [the sucrose and food manufacturing] sector which [the UK] should not hold back.’(28)

Good health needs good agriculture policy

European agricultural policy and particularly the policy of sugar liberalisation have largely not considered health.(13, 14) While some weak public health objectives have been incorporated in recent years, health is not listed as one of CAP’s five main objectives.(29–31) The structuring and sequencing of the reforms in 2006 and 2013 indicates that they were designed to benefit industry rather than with the public’s health in mind.(21) There has been no pause to consider the broader health implications of sugar reform—even though from the outset the European Commission forecasted that sugar consumption would increase as a result of these reforms.

Tension between agricultural and nutritional policies is widespread, not only in Europe. In most countries agricultural and health ministries are separate with little interaction. For example, US agricultural policy has heavily encouraged over-production of corn since the 1970s, and in doing so has contributed to large-scale production and consumption of HFCS, conflicting with the health goals of reducing obesity and type 2 diabetes.(1, 16)

However, consensus is growing that agricultural policy is integral to population health.(12–19) Examples of good practice exist. The North Karelia project in Finland instituted changes in agriculture, including a switch from dairy to fruit production and introduction of rapeseed, which, alongside other initiatives, was associated with improvements in population diet and reduced cardiovascular disease.(18) Poland removed dairy and other animal fat subsidies in the 1990s, which is credited with contributing to an observed decline in coronary heart disease.(17)

The timing of the sugar reform is particularly unfortunate, creating a tension between agricultural policy and health policy and generating mixed signals for the food industry. There is a risk that ongoing and proposed measures designed to reduce sugar consumption (e.g. reformulation to remove sugar, taxes on SSBs, marketing restrictions), could be significantly undermined by larger trends in price and production of sugars in Europe.

Possible effects on health inequalities

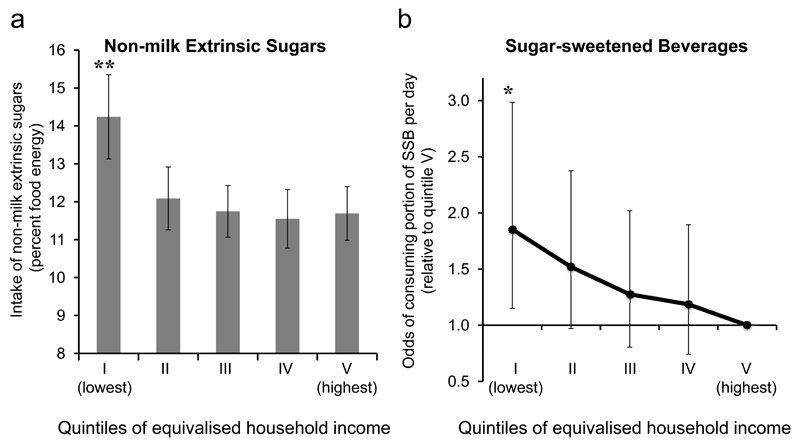

There is already a socioeconomic gradient in sugar consumption among adults and a similar gradient in consumption of SSBs, which are a major source of added sugars (Figure 3). High sugar-containing foods are among the cheapest foods.(32) Any reformulation to increase sugars in processed foods is unlikely to happen equally across all product lines. Cheaper processed food items, marketed on price rather than quality, may be most liable to price reduction or reformulation to incorporate more sugars. These cheaper foods are purchased and consumed more frequently by lower socioeconomic groups,(33) who are more price-sensitive consumers.(34) Consequently, this reform may disproportionately increase sugar consumption among lower socioeconomic groups, contributing to widening health inequalities.

Figure 3.

3a Survey-weighted, estimated mean intake (and 95 percent confidence intervals) of non-milk extrinsic sugars, percent food energy, by equivalised household income quintile, for adults aged 19-64. Data from years 1-4 of the NDNS rolling programme, 2008-12. Estimates are adjusted for age, sex, race, survey year and total dietary energy intake; 3b Odds of consuming a 165 ml portion of sugar-sweetened beverage per day for women and men aged 19-64 year in NDNS. Odds are estimated with reference to highest income group and adjusted for age, sex, race, survey year and total dietary energy intake; ** and * denote statistical differences between the lowest and highest quintile groups of p<0.001 and p<0.05, respectively

Messages for policy-makers

If agricultural policies are important in shaping food consumption and nutrition,(17–19) agricultural policies in the UK and Europe should explicitly integrate health. We should aspire to agricultural policies that promote a healthier diet, which can also deliver improvements in sustainability.(35) Agricultural policies should be subject to full and meaningful health impact assessments. No health impact assessment of the sugar reforms was undertaken. Such an assessment would provide an estimate of the scale of potential population health impacts and help identify solutions to mitigate health harms. Although challenging, the relative success of conducting health impact assessments in transport and integrating health into transport decision-making suggests it is achievable.(36–38)

Given financial pressures on industry to reformulate foods to incorporate more sugar (or at least maintain existing formulation), it may be necessary for governments to mandate targets for reducing sugar contents of processed foods, and implement robust systems for monitoring compliance. It will also be important to undertake surveillance of food prices, diet, and health to track the effects these reforms have on the cost and availability of foods, the sugars in the food supply, and the impacts on diet including patterning of consumption among socioeconomic groups.

Conclusions

Greater attention must be paid to the role agricultural policy plays in determining the price, availability and consumption of sugars. The effects of policy reforms in sugar and other areas must be considered from a health perspective or else risk worsening public health. Of particular importance, policymakers must take special account of equity considerations in order to reduce—and not exacerbate—growing socioeconomic inequalities in diet and health. At present, agriculture and health are working at odds with each other instead of in tandem. In light of recent CAP changes and wider emerging public health evidence, it is particularly pressing that Europe explore a set of short- to medium-term responses to address the projected increase of sugars in the food supply. In the longer term, Europe and the UK must integrate agriculture and health policies to help begin to address the larger structural factors affecting diet and population health.

Key Messages.

The 2013 CAP reform will lower the commodity price of sugar and liberalise high fructose corn syrup production in 2017, which has the potential to increase sugar consumption in the UK.

These effects may disproportionately impact the lowest socioeconomic groups and widen health inequalities.

Europe must explore both short-term responses to the projected increase of sugars in the food supply and long-term structural solutions that enable agricultural policy to support health policy.

Funding Acknowledgement

This work was undertaken by the Centre for Diet and Activity Research (CEDAR, MR/K023187/1), a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Funding from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research, and the Wellcome Trust, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged. EKA was also supported by Fulbright-Schuman grant and a Harvard Knox Fellowship from Harvard University.

Footnotes

Contributors and Sources:

Emilie Aguirre is a Research Associate researching the diet, nutrition, and obesity implications of agricultural and trade law. She holds a Juris Doctorate from Harvard Law School, a Master’s degree in law from University of Cambridge, and contributed the legal analysis of agriculture and trade policies vis-à-vis sugar. Funding from a Fulbright-Schuman grant enabled her research. Oliver Mytton is an honorary specialty registrar in public health examining population-level interventions to improve diet and promote physical activity. Dr Mytton contributed to the writing of the manuscript and policy analysis. Pablo Monsivais is a public health researcher examining structural determinants of diet and health. Dr Monsivais contributed to the writing and quantitative analysis and supervised the project.

Sources of information used to prepare this paper include original EU Common Agricultural Policy texts; European Commission texts and analyses; medical, public health, agricultural and legal secondary literature; and data from FAOSTAT, Living Cost and Food Survey, United States Consumer Price Index, the UK Retail Price Index and the National Diet and Nutrition Survey. Emilie Aguirre is nominated as guarantor of the article.

Conflicts of Interest:

None.

References

- 1.Imamura F, O’Connor L, Ye Z, Mursu J, Hayashino Y, Bhupathiraju SN, et al. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. BMJ. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h3576. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Te Morenga L, Mallard S, Mann J. Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ. 2013;346 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7492. 2013-01-15 23:31:43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Chomitz VR, Antonelli TA, Gortmaker SL, Osganian SK, et al. A Randomized Trial of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Adolescent Body Weight. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(15):1407–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romaguera D, Norat T, Wark PA, Vergnaud AC, Schulze MB, van Woudenbergh GJ, et al. Consumption of sweet beverages and type 2 diabetes incidence in European adults: results from EPIC-InterAct. Diabetologia. 2013 Jul;56(7):1520–30. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2899-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Draft Carbohydrates and Health report: Scientific consultation: 26 June to 1 September 2014. Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Statistics UOfN, editor. National Diet and Nutrition Survey. 2015. editor. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mytton OT, Clarke D, Rayner M. Taxing unhealthy food and drinks to improve health. BMJ. 2012;344:e2931. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capewell S. Sugar sweetened drinks should carry obesity warnings. BMJ. 2014;348 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3428. 2014-05-27 22:34:51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moodie R, Stuckler D, Monteiro C, Sheron N, Neal B, Thamarangsi T, et al. Profits and pandemics: prevention of harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink industries. The Lancet. 2013;381(9867):670–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tedstone A, Anderson S, Allen R. Sugar reduction: Responding to the challenge. Public Health England; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson RJ, Minjares R, Naumoff KS, Shrimali BP, Martin LK. Agriculture Policy Is Health Policy. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 2009;4(3–4):393–408. doi: 10.1080/19320240903321367. 2009/11/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorward A, Dangour AD. Agriculture and health. BMJ. 2012;344 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7834. 2012-01-17 11:32:27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawkesworth S, Dangour AD, Johnston D, Lock K, Poole N, Rushton J, et al. Feeding the world healthily: the challenge of measuring the effects of agriculture on health. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2010;365(1554):3083–97. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0122. 2010-09-27 00:00:00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birt C. A CAP on Health? The impact of the EU Common Agricultural Policy on public health. Faculty of Public Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallinga D. Agricultural policy and childhood obesity: a food systems and public health commentary. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010 Mar-Apr;29(3):405–10. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zatonski WA, Willett W. Changes in dietary fat and declining coronary heart disease in Poland: population based study. BMJ. 2005 Jul 23;331(7510):187–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7510.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pekka P, Pirjo P, Ulla U. Influencing public nutrition for non-communicable disease prevention: from community intervention to national programme--experiences from Finland. Public Health Nutr. 2002 Feb;5(1A):245–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nugent R. Bringing Agriculture to the Table: How Agriculture and Food Can Play a Role in Preventing Chronic Disease. The Chicago Council on Global Affairs; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Treaty Establishing the European Economic Community. 1957.

- 21.Richardson B. Sugar: Refined Power in a Global Regime. Palgrave Macmillan; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prospects for Agricultural Markets and Income in the EU 2014-2024. Agriculture and Rural Development, European Commission; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonnet C, Requillart V. Does the EU sugar policy reform increase added sugar consumption? An empirical evidence on the soft drink market. Health Economics. 2011;20(9):1012–24. doi: 10.1002/hec.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Commodity Price Dashboard No 35 -- April 2015 edition. European Commission; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burgess K. Life looks sweeter for RGF as it offloads sugar business. Financial Times. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moeller SM, Fryhofer SA, 3rd, Osbahr AJ, Robinowitz CB. The effects of high fructose syrup. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009 Dec;28(6):619–26. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2009.10719794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schorin MD. High Fructose Corn Syrups, Part 1: Composition, Consumption and Metabolism. Nutrition Today. 2005;40(248) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Common Agricultural Policy deal struck. Gov.UK; 2013. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/common-agricultural-policy-deal-struck. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cross-compliance - Agriculture and rural development. European Commission; 2015. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/envir/cross-compliance/index_en.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fruit and vegetables: The 2007 reform - Agriculture and rural development. European Commission; 2015. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/fruit-and-vegetables/2007-reform/index_en.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. OJ. 2012;C 326:01. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones NR, Conklin AI, Suhrcke M, Monsivais P. The growing price gap between more and less healthy foods: analysis of a novel longitudinal UK dataset. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pechey R, Jebb SA, Kelly MP, Almiron-Roig E, Conde S, Nakamura R, et al. Socioeconomic differences in purchases of more vs. less healthy foods and beverages: analysis of over 25,000 British households in 2010. Soc Sci Med. 2013 Sep;92:22–6. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowman SA. A comparison of the socioeconomic characteristics, dietary practices, and health status of women food shoppers with different food price attitudes. Nutr Res. 2006 Jul;26(7):318–24. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scarborough P, Allender S, Clarke D, Wickramasinghe K, Rayner M. Modelling the health impact of environmentally sustainable dietary scenarios in the UK. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012 Jun;66(6):710–5. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woodcock J, Edwards P, Tonne C, Armstrong BG, Ashiru O, Banister D, et al. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: urban land transport. Lancet. 2009 Dec 5;374(9705):1930–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61714-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kahlmeier S, Racioppi F, Cavill N, Rutter H, Oja P. "Health in all policies" in practice: guidance and tools to quantifying the health effects of cycling and walking. J Phys Act Health. 2010 Mar;7(Suppl 1):S120–5. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s1.s120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Local Sustainable Transport Fund - Guidance on the Application Process. Department of Transport; 2010. [Google Scholar]