Abstract

Aims

The aims were to (1) estimate the prevalence of alcohol and drug use disorders in prisoners on reception to prison, and (2) estimate and test sources of between study heterogeneity

Methods

Studies reporting the 12 month prevalence of alcohol and drug use disorders in prisoners on reception to prison from 1 January 1966 to 11 August 2015 were identified from 7 bibliographic indexes. Primary studies involving clinical interviews or validated instruments leading to DSM or ICD diagnoses were included; self-report surveys and investigations that assessed individuals more than 3 months after arrival to prison were not. Random-effects meta-analysis, and subgroup and meta-regression analyses were conducted. PRISMA guidelines were followed.

Results

In total, 24 studies with a total of 18,388 prisoners across 10 countries were identified. The random-effects pooled prevalence estimate of alcohol use disorder was 24% (95% CI 21–27) with very high heterogeneity (I2 = 94%). These ranged from 16 to 51% in male and 10 to 30% in female prisoners. For drug use disorders, there was evidence of heterogeneity by sex, and the pooled prevalence estimate in male prisoners was 30% (95% CI 22–38; I2 = 98%; 13 studies; range 10-61%) and, in female prisoners, it was 51% (95% CI 43–58; I2 = 95%; 10 studies; range 30-69%). On meta-regression, sources of heterogeneity included higher prevalence of drug use disorders in women, increasing rates of drug use disorders in recent decades, and participation rate.

Conclusions

Substance use disorders are highly prevalent in prisoners. Around a quarter of newly incarcerated prisoners of both sexes had an alcohol use disorder, and the prevalence of a drug use disorder was at least as high in men, and higher in women.

Introduction

Prisons around the world detain large number of individuals with substance use problems, which increase the risk of mortality after prison release [1–3] and repeat offending [4, 5]. In addition, alcohol use disorders are associated with suicide inside prison [6], and of perpetrating violence and being victimized inside custody [7, 8].

The treatment gap for substance use disorders inside prison has been reported in many studies [9, 10]. Estimates of the prevalence of these disorders in prisoners can assist in effectively plan service provision, target scarce resources, and develop and evaluate initiatives to reduce the gap between health needs and interventions. A previous systematic review reported ranges for drug abuse and dependence of 10-48% in men and 30-60% in women on reception or arrival to prison. For alcohol abuse and dependence, ranges of 18-30% for men and 10-24% for women were reported [11]. There were very high rates of heterogeneity between these included studies (with I2 values of over 80%), which were investigated in subgroup analyses. Lower prevalences were associated with studies where psychiatrists acted as interviewers, and higher prevalences for drug use disorders in remand prisoners. However, this review is now dated, with its search for primary studies ending in 2004, and a number of relevant investigations have been subsequently published. In addition, subgroup analyses were the limited number of primary studies by sex, and an updated review will allow for further investigation of sources of between-study variation.

The aim of the current paper is to provide an update of prevalence estimates of alcohol and drug use disorders in prisoners, and estimate sources of between-study heterogeneity. As part of this, we have used the term substance use disorder, which does not distinguish between ‘abuse’ and ‘dependence.’ In this update, we have also conducted meta-analyses to report pooled prevalence estimates and meta-regression to examine sources of variation between included studies.

Methods

Search strategy

We identified surveys of alcohol and drug use disorder in general prison populations (defined as remand/detainee and/or sentenced prisoners who are sampled from the whole population of a correctional institution) published between January 1966 and August 2015. For the period January 1966 and January 2004, methods have been described in a previous systematic review conducted by one of the authors (SF) [11]. For this update, we searched the following databases from 1 January 2004 to 11 August 2015: PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Global Health, PubMed, CINAHL, National Criminal Justice Reference Service, and EMBASE. We used a combination of search terms relating to substance use disorder (i.e. substance*, alcohol, drug*, misuse, dependen*, abuse) and prisoners (i.e. inmate*, sentenced, remand, detainee*, felon*, prison*, incarcerat*), which are same search terms used in the previous review except for the addition of ‘incarcerate*.’ Additional targeted searches covered relevant reference lists, and non-English articles were translated. We corresponded with authors to clarify data when necessary. We followed the PRISMA guidelines [12] (Appendix A) and registered the protocol for this review with PROSPERO (registration code CRD42016036416) [13].

Study eligibility

Inclusion criteria were studies: (a) reporting diagnoses of substance use disorder (i.e. substance abuse and/or dependence) based on clinical examination or by interviews using validated diagnostic instruments (based on DSM (versions III to IV-R; codes 303.90, 304.00-90, 305.00-90, excluding nicotine-related disorders) and ICD versions 9 and 10 (ICD-9: 303-305; ICD-10 codes: F10-19.1-2 except F17)); (b) with diagnoses based on the previous 12 months from the time when participants were interviewed/examined; (c) that sampled the general prison population within 3 months of arrival to prison.. We excluded studies that selected subgroups for interview (e.g. prisoners referred for treatment, specific categories of offenders), as the aim was to provide a prevalence estimate for the whole prison population [14–16]. After correspondence with authors, if studies reported combined prevalence for alcohol and drug [17, 18] or combined male and female prevalence, these were excluded [19] as we aimed to report estimates separately by sex, and by drug and alcohol use disorder. Studies that reported specific drugs [20, 21], self-screening measures [22, 23] or solely lifetime prevalence were also excluded [24].

Publications in any language were included in the search: studies from low and middle income (LMI) countries were reported separately given high heterogeneity [25, 26]. Similarly, studies with juvenile/youth prisoners were analysed separately [27–31].

Data extraction and analysis

Two researchers (IY and AH) independently extracted information on year of publication, geographical location, total sample, sex, prisoner status (remand/sentenced), average age, method of sampling, sample size, participation rate, type of interviewer, diagnostic instrument, diagnostic criteria (ICD vs DSM), and number diagnosed with substance use disorders. If older studies reported dependence prevalence, this was prioritised over abuse as we considered these had higher diagnostic validity [32, 33] (except when only combined prevalence for abuse and dependence was available). Eligible studies were assessed for quality using JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data, which uses 9 criteria including sample size, sampling, sample description, appropriate statistical analysis, and response rates (Appendix B) [34].

We conducted a random-effects analysis, which assigns similar weights to all studies included in the meta-analysis regardless of sample size [35]. If there were high levels of overall heterogeneity (I2>75%), we also reported estimate ranges as an alternative. Meta-regression analysis was performed to examine sources of between-study heterogeneity on a range of study pre-specified characteristics (i.e. sex, age, publication year, country [USA v. other countries], prisoner status [sentenced v. remand/detainee/unsentenced], participation rate, sample size, diagnostic criteria [ICD v. DSM], and psychiatric interviewer). Univariable analysis was conducted for both dichotomous and continuous definitions of a variable (e.g. publication year: continuous v. before or after 2000). Multivariable analyses were not conducted due to the limited number of primary studies. If there were less than 10 studies that reported an explanatory variable, it was excluded from the meta-regression [36]. Selected continuous variables (study year and proportion sentenced) were converted to dichotomous variables for reporting of pooled prevalence estimates of subgroups. Accordingly, in the meta-regression, studies that combined both remand and sentenced prisoners were excluded if: (1) prisoner type comprised more than 10% of the total study participants or was unspecified, and (2) separate prevalence data were not provided for each type [37–42].

In addition, pooled prevalence estimates of the subgroups that did not have more than one study in each relevant category were not reported even if they had significant results on meta-regression. Further, we conducted subgroup analyses stratified on pre-specified variables based on our previous review – sex, whether the country of origin was USA or not, remand/detainee vs sentenced prisoner status, whether the assessment was conducted by a psychiatrist or not. We added a new subgroup analysis based on the date of publication (year 2000, which was approximately the median date). To test for publication bias, funnel plot analysis and Egger’s test were conducted on all studies stratified by disorder (i.e. AUD and SUD) and also by sex and disorder [43]. Thus, 6 separate Egger’s tests were performed and smaller studies were not combined in these analyses. Studies with juvenile prisoners or LMI countries were not included as they were clinical heterogeneous and limited in number. The Egger test quantifies bias captured in the funnel plot analysis with linear regression using the value of effect sizes and their precision (SE) and assumes that the quality of study conduct is independent of study size [35] All analyses were conducted in Stata (STATA-IC) version 14 using the following commands: metan (for random-effects meta- analysis), metareg (for meta-regression), metabias (for publication bias analysis), and heterogi (for calculation of confidence intervals for heterogeneity level).

Results

Study characteristics

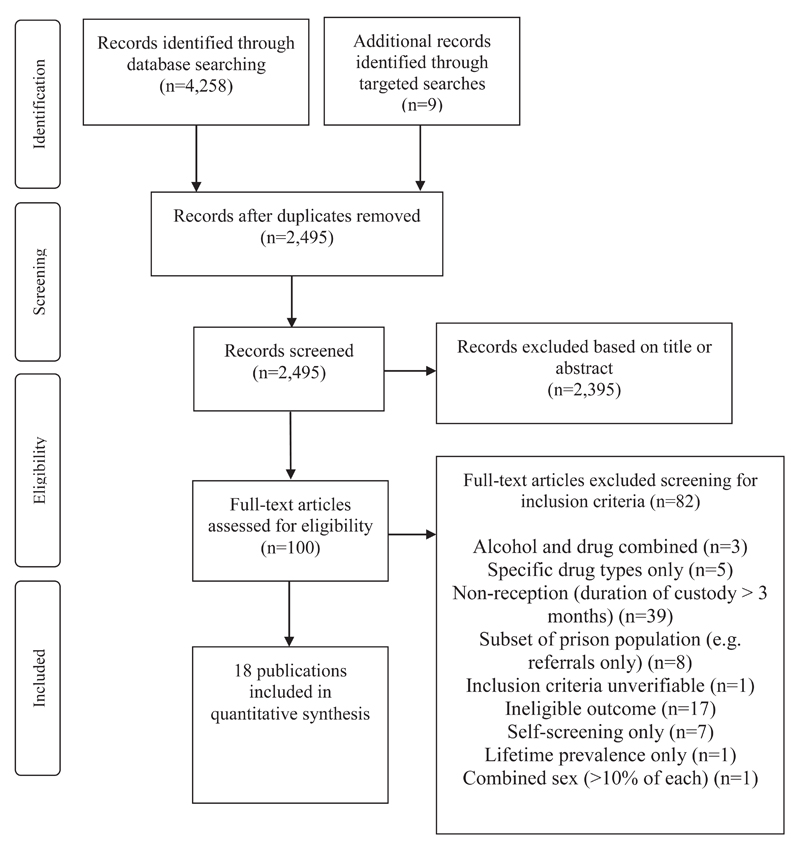

We identified 24 publications for the main analysis (Figure 1); 13 of which were from the previous review [37–39, 44–53], and 11 new studies from 2004 [40–42, 54–61]. Two additional studies in LMI countries (Chile [26] and Brazil [25]), and 5 studies on juvenile prisoners (mean age: 16.7 years) were examined separately (Appendix C) [27–31].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search strategy for update (2004-2015).

Studies in the main analysis were from 10 different countries (Australia [40], Austria [61], England [48], France [42], Germany [56], Iceland [60], Ireland [39, 41, 51, 55], Netherlands [57], New Zealand [37], and USA [38, 44–47, 49, 50, 52, 54, 59]) - with 40.5% (7,456 prisoners) of the adult combined sample from the United States. Participants were 18,388 prisoners, both sentenced and remand/detainee, 64% of whom were male. The mean age was 30.2 years (range 17–67 yrs). Of the 5,835 prisoners with criminal history information reported, 924 prisoners (15.8%) were charged or convicted with a violent offence. There were more sentenced (11,065; 60.2%) than remand/detainee/unsentenced prisoners (2975; 16.2%), and eleven investigations included both sentenced and remand prisoners (4,348; 23.6%) (‘mixed’ studies) [38–40, 42, 51, 55–57]. Apart from two studies based on clinical interviews [48, 51], the others involved trained interviewers using validated, structured diagnostic instruments (Table 1 for details). Prevalence of drug use disorder were based on all drugs excluding alcohol and tobacco (i.e. cannabis, opioids, cocaine, amphetamine, hallucinogens, inhalants, other stimulants, and tranquilizers). The individual prevalence estimates of substance use disorders are summarized in Table 2. In terms of quality of the included studies, we determined that 9 out of 24 studies were of high quality as they met all 9 criteria in the quality checklist - including a sufficient sample size (>250), low refusal rate (<20%) and detailed description of study subjects and setting [38, 41, 42, 44, 46, 49, 53, 54, 59] (see Appendix B for full criteria).

Table 1.

Study characteristics of newly included studies of substance use disorder in prisoners on arrival into custody (by study year).

| Study | Country | Population | Sampling strategy | Sampling method | Instrument criteria | Diagnostic criteria | Mean age (years) | Age Range | Psychiatric interviewer1 | Mean duration in prison | Type of prisoner | % male | No committed violent offences | No. not consenting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collins 1988 | USA | North Carolina prisons | All males admitted March–June 1983 | Consecutive new arrivals at reception | DIS2 | DSM-III3 | 27.6 | Not reported | N | Not reported | Sentenced | 100% | 157 | 117 |

| Daniel 1988 | USA | Missouri Correctional Classification Center | Consecutive arrivals over 7 months | Consecutive sampling at reception | DIS | DSM-III | 29 | SD 8.2 | N | Not reported | Sentenced | 0% | 21 | 0 |

| Teplin 1994 | USA | Cook County Department of Corrections, Chicago | All remands 1983–84 | Stratified random sampling | DIS | DSM-III-R | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Remand | 100% | Not reported | 35 |

| Jordan 1996 | USA | Correctional Institution for Women, Raleigh, NC | All sentenced incoming prisoners in 1991–92 | Combined consecutive and random sampling | CIDI4 | DSM-III-R | 31.5 | 18–65 | Y | 5–10 days | Sentenced | 0% | 98 | 42 |

| Smith 1996 | Ireland | Mountjoy Prison, Dublin | All new arrivals in 1992–93 | Simple random sampling | Clinical interview | DSM-III-R | Not reported | Not reported | Y | 1 day | Mixed | 100% | Not reported | 2 |

| Teplin 1996 | USA | Cook County Department of Corrections, Chicago | All remands 1991–93 | Stratified random sampling | DIS | DSM-III-R | 28 | 17–67 | N | Not reported | Remand | 0% | 201 | 59 |

| Mason 1997 | England | Durham Remand prison for men | All remands over 7 months | Consecutive sampling at reception | Clinical interview | DSM-IV | Not reported | Not reported | Y | Not reported | Remand | 100% | Not reported | 0 |

| McClellan 1997 | USA | Prison unit for men and reception center for women, Texas | All newly admitted inmates | Simple random sampling | DIS | DSM-III | 32.8 male 32.3 female |

Not reported | N | Not reported | Mixed | 67% | Not reported | 202 |

| Mohan 1997 | Ireland | Mountjoy Prison, Dublin | Consecutive new arrivals over 3 months | Simple random sampling | SCAN5 | DSM-IV | 25.8 | 17–48 | Y | Not reported | Mixed | 0% | 0 | 0 |

| Peters 1998 | USA | Holliday Transfer Facility, Texas | Consecutive new arrivals in 1996 | Consecutive sampling at reception | SCID IV6 | DSM-IV | 32.6 | SD 10.2 | Y | 14–60 days | Sentenced | 100% | 61 | 100 |

| Lo 2000 | USA | Cuyahoga County Jail, Cleveland, USA | All sentenced incoming prisoners in 1997–98 | Consecutive sampling | DIS | DSM-IV | 30 | 18–58 | N | Not reported | Sentenced | 76% | Not reported | 29 |

| Marquart 2001 | USA | Texas Dept. of Criminal Justice, institutional division | All female prisoners admitted in 1994 | Simple random sampling | DIS | DSM-IV | 32.3 | 17–63 | Y | Not reported | Remand | 0% | Not reported | 0 |

| Butler 2003 | Australia | Metropolitan Remand and Reception Centre, female Correctional Centre, and remote reception sites | Consecutive convenience sample of admissions over 3 months | Convenience sample among those admitted over 3 months | CIDI | DSM-IV and ICD-107 | Men 29.61, women 29.10 | Not reported | Mental health nurses | Not reported | Mixed | 100% | Not reported | Non-screened: 67.4% |

| Wright 2006 | Ireland | The Dochas Centre, female wing of Limerick Prison near Dublin | Consecutive admissions in Aug03 and between Apr04-May04 | All consenting prisoners interviewed at reception (10.7% of all committals) | SADS-L,8 SODQ9 | ICD-10 | 27.4 | Not reported | Post-membership psychiatrists | Aimed to interview within 72 hours of reception | Mixed | 0% | 14/60 =23.3% | 30 |

| Jones 2006 | England | HMP Grendon (therapeutic community prison) | Consecutive admissions in 2003 | All consenting prisoners interviewed at reception | CAAPE10 | DSM-IV | 30.7 | 18-66 | Psychologic al counselor | Shortly after admission | Sentenced | 100% | Not reported | 0 |

| Bulten 2009 | Netherla nds | Vught prison | Random sample of admissions to 'general wards' of prison | Random sample among new admissions | MINI11 | DSM-III-R | 30.4 | 18-59 | Trained psychologist | First weeks of incarcerati on | Mixed | 100% | 0.38 | 50 |

| Curtin 2009 | Ireland | Cloverhill, Limerick and Cork Prisons (remand), Mountjoy and Cork Prisons (sentenced) | Consecutive admissions, up to 10 per day | All consenting prisoners interviewed at reception | SADS-L | ICD-10 | 29.8 | 18+ | Post-membership psychiatrists | Within 72 hours | Mixed | 100% | 79 | 54 |

| Einarsson 2009 | Iceland | Icelandic prison for sentenced inmates | All new admissions in study period (females excluded) | All consenting prisoners interviewed at reception | MINI 5 | DSM-IV | 31 | 19-56 | Psychologist | Within 10 days | Sentenced | 100% | 0.17 | 16 |

| Stompe 2010 | Austria | Prison Vienna-Josefstadt | Consecutive recruitment of admissions. | All eligible new admits. | SCAN | ICD-10 | Not reported | 18+ | Doctor (psychiatry trainee) | Not reported | Mixed | 100% | Not reported | 0 |

| Proctor 2012 | USA | Minnesota state prisons | All reception 2000–2003 | All consenting prisoners interviewed at reception | SUDDS-IV12 | DSM-IV | 32.8 | 18-58 | Addictions counselors (computer recorded interview) | Not reported | Sentenced | 0% | Not reported | 0 |

| Sarlon 2012 | France | Local prisons of Fleury-Merogis, Loos, Lyon, Marseille | Reception: new receptions to local prisons in four areas | All consenting prisoners interviewed at reception | MINI plus 5.0 | DSM-IV | 29.9 | 18-64 | clinicians (Psychiatrist and psychologist) | within 14 days | Mixed | 100% | Not reported | 30 |

| Tavares 2012 | Brazil | Porto Alegre prison | Consecutive admissions | Random sample among new admits (calculation of 30 a base-point for recruitment) | MINI-plus (Brazilian version) | DSM-IV | 27.88 | Not reported | Not reported | Within 3 months | Sentenced | 100% | 10 | 0 |

| Mir 2015 | Germany | Penal justice system in Berlin | Consecutive admissions screened for eligibility | All eligible new admits. Aimed for sample of 150. | MINI 6.0 (German version) | DSM-IV | 34.3 | Not reported | Clinical psychologist | Within 1 month (usually < 1 wk) | Mixed | 0% | 0 | 48 |

| Mundt 2015 | Chile | Santiago Uno central facility, Centro Penitenciario Feminino,San Joaquín, CPF San Miguel central admission facilities | Consecutive admissions | All consenting prisoners interviewed at reception | MINI Spanish version | DSM-IV | 31.6 | Not reported | Clinical psychologist/nurse (trained by senior consultant psychiatrist) | 7.7 days | Remand | 54% | 127 | 30 |

| Hoffmann 2015 | USA | 8 adult state prison facilities of Minnesota | Uses routine data collected on admissions, all admissions during 2002–2003. | All consenting prisoners interviewed at reception | SUDDS-IV | ICD-10 | 31 | 18-65 | Addiction counselors | On admission | Sentenced | 90% | Not reported | 0 |

Y = Yes; psychiatrist, N = No; non-psychiatrist (trained interviewer)

DIS = Diagnostic Interview Schedule

DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; DSM-IIIR = DSM-III Revised

CIDI = Composite International Diagnostic Interview

SCAN = Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry

SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders

ICD = International Classification of Diseases

SADS-L = Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia – Lifetime version

SODQ = Severity of Opiate Dependence Questionnaire

CAAPE = Comprehensive Addictions and Psychological Evaluation

MINI = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

SUDDS = Substance Use Disorders Diagnostic Schedule

Table 2.

Prevalence estimates of substance use disorder in reception studies of prisoners

| Study | Total no. | Males (%) | No. with alcohol use disorder | No. with drug use disorder | Prevalence of alcohol use disorder (%) | Prevalence of drug use disoder (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel 1988 | 100 | 0 | 10** | _ | 10.0 | _ |

| Collins 1988 | 1120 | 100 | 302** | 112** | 27.0 | 10.0 |

| Teplin 1994 | 728 | 100 | 116** | 129** | 15.9 | 17.7 |

| Jordan 1996 | 805 | 0 | 244** | 138** | 30.3 | 17.1 |

| Smith 1996 | 235 | 100 | 63 | 46 | 26.8 | 19.6 |

| Teplin 1996 | 1272 | 0 | 667** | 304** | 52.4 | 23.9 |

| Bushnell 1997 | 100 | 100 | 19** | 14** | 19.0 | 14.0 |

| Mason 1997 | 548 | 100 | 116** | 214** | 21.2 | 39.1 |

| McClellan 1997 | 1030 male 500 female |

67 | 309 male 93 female |

331 male 227 female |

30.0 male 18.6 female |

32.1 male 45.4 female |

| Mohan 1997 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 0.0 | 57.8 |

| Peters 1998 | 400 | 100 | 86** | 100** | 21.5 | 25.0 |

| Lo 2000 | 152 male 48 female |

76 | _ | 73 male 29 female |

_ | 48.0 male 60.4 female |

| Marquart 2001 | 500 | 0 | 88** | 224** | 17.6 | 44.8 |

| Butler 2003 | 756 male 165 female |

82 | 142 male 27 female |

378 male 111 female |

19.2 male 16.5 female |

52.0 male 68.9 female |

| Wright 2006 | 94 | 0 | 23 | 45 | 24.7 | 48.4 |

| Jones 2006 | 118 | 100 | 53 | _ | 44.9 | _ |

| Bulten 2009 | 191 | 100 | 53 | 57 | 27.7 | 29.8 |

| Curtin 2009 | 615 | 100 | 148 | 206 | 24.1 | 33.5 |

| Einarsson 2009 | 90 | 100 | 46 | 55 | 51.1 | 61.1 |

| Stompe 2010 | 200 | 100 | 59** | _ | 29.5 | _ |

| Proctor 2012 | 801 | 0 | 242 | 456 | 30.2 | 56.9 |

| Sarlon 2012 | 267 | 100 | 43 | 47 | 16.1 | 17.6 |

| Mir 2015 | 150 | 0 | 31 | 71 | 20.7 | 47.3 |

| Hoffmann 2015 | 6871 | 90 | 2177 | _ | 31.7 | _ |

| LMI countries | ||||||

| Tavares 2012 | 60 | 100 | 26 | 18 | 43.3 | 30.0 |

| Mundt 2015 | 229 male 198 female |

54 | 68 male 23 female |

128 male 47 female |

29.7 male 11.6 female |

55.9 male 23.7 female |

| Juvenile prisoners | ||||||

| Köhler 2009 | 149 | 100 | 31 | _ | 20.8 | _ |

| Vreugdenhil 2003 | 204 | 100 | 45 | _ | 22.1 | _ |

| McClelland 2004 | 1143 male 631 female |

64 | 289 male** 156 female** |

276 male** 260 female** |

25.3 male 24.7 female |

24.1 male 41.2 female |

| Plattner 2012 | 275 | 100 | 45 | 135 | 16.4 | 49.1 |

| Dixon 2005 | 100 | 0 | 55** | 85** | 55.0 | 85.0 |

Figures for combined abuse and dependence; rest are dependence only.

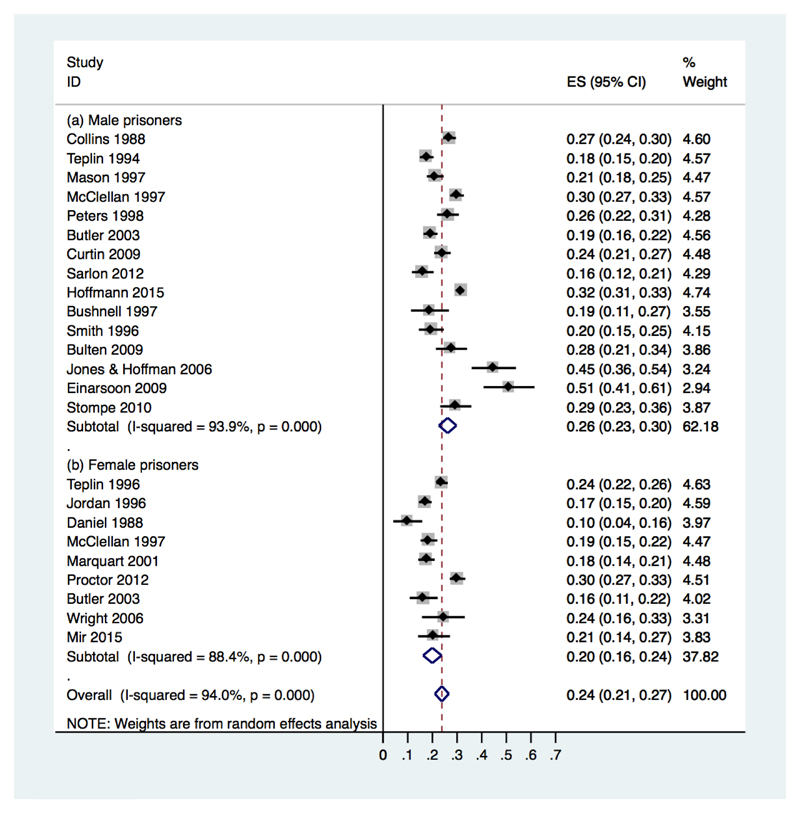

Alcohol use disorder

The overall pooled prevalence estimate of alcohol use disorder was 24% (95% CI 21–27; with very high levels of between study heterogeneity (I2 = 94%; 95% CI 92–95). Fifteen studies of alcohol use disorder in men were identified in 12,739 prisoners [37, 38, 40–42, 44, 48, 50–52, 57, 58, 60, 61]. Pooled prevalence estimate for males was 26% (95% CI 23–30), with substantial heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 94%; 95% CI 92–96) and a range of 16 to 51% in individual studies. We identified 10 investigations that measured alcohol use disorder in female prisoners [38–40, 45, 46, 49, 53–56], and pooled prevalence estimate was 20% (95% CI 16–24) with high heterogeneity (I2=88%; 95% CI 80–93). Primary studies provided estimates that varied from 10 to 30%.

Two investigations in LMI countries reported prevalences of 43% [25] and 30% [26]. There were 4 investigations of alcohol use disorder in juvenile men, and prevalences ranged from 16 to 25% [27–29, 31])

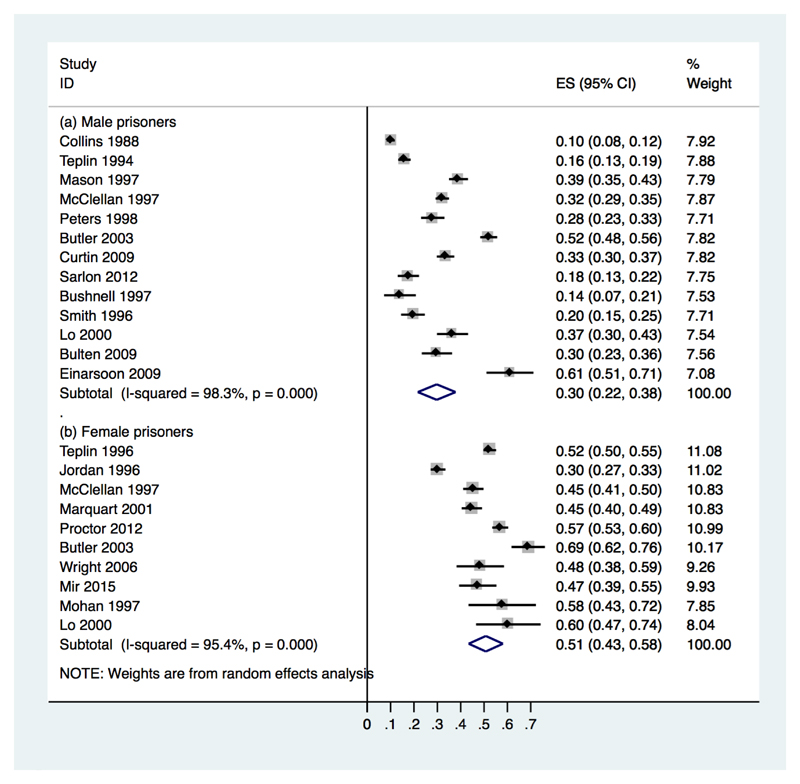

Drug use disorder

There was evidence of heterogeneity by sex in univariable meta-regression, and prevalence estimates for drug use disorder are stratified accordingly.

Men

There were 13 studies that reported drug use disorder in male prisoners [37, 38, 40–42, 44, 47, 48, 50–52, 57, 60]. The pooled prevalence estimate was 30% (95% CI 22–38) with very high heterogeneity (I2=98%; 95% CI 98–99). These varied from 10 to 61%. In LMI countries, reported prevalences were 30% [25] and 56% [26].

Women

Ten relevant studies on drug use disorder in female prisoners were identified [38–40, 46, 47, 49, 53–56]. The pooled prevalence estimate was 51% (95% CI 43–58) with substantial heterogeneity (I2=95%; 95% CI 93–97). Prevalences ranged from 30 to 69%.

Sources of heterogeneity

In univariable meta-regression (n = 23 studies), factors associated with heterogeneity included: females reported higher drug use disorder than males (β = 0.21; 95% CI 0.33–0.10; p = 0.001), more recent studies (published after 2000) reported higher rates of drug use disorder (β = 0.15; 95% CI 0.12–0.28; p = 0.03), and participation rate was negatively associated with drug use disorder (β = -0.37; 95% CI -0.73, -0.01; p = 0.045). No significant associations were reported with alcohol use disorder, although there was a non-significant link with publication year as a continuous variable (β = 0.004; 95% CI -0.00002, 0.008; p = 0.051).

We also investigated using subgroups possible explanations for between-study variation (Table 3). This found that there were higher estimates for drug use disorders in women, and for both drug and alcohol use disorders since 2000, which were consistent with findings on meta-regression. In addition, in alcohol use disorders, there were higher prevalence estimates in sentenced (than remand) prisoners. However, these subgroup analyses had overlapping CIs, apart from a higher estimate for women with drug use disorder compared to men.

Table 3.

Pooled prevalence estimates for drug and alcohol use disorders in newly incarcerated men and women by pre-specified subgroups.

| Alcohol use disorder, | Drug use disorder, | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Country | ||||

| High income countries | – | – | 30 (22–38) (n = 5,750; k =13) | 51 (43–58) (n = 4,379; k =10) |

| USA | 23 (19–27) (n = 9,619; k = 5) | 20 (15–25) (n = 3,978; k = 6) | 37 (26–48) (n = 2,948; k = 5) | 48 (39–57) (n = 3,926; k = 6) |

| Non-USA | 25 (21–28) (n = 3,573; k = 14) | 20 (15–24) (n = 453; k = 4) | 40 (31–50) (n = 3,255; k = 12) | 56 (44–68) (n = 453; k = 4) |

| Publication year | ||||

| Before 2000 | – | – | – | 46 (33–58) (n = 2,622; k = 4) |

| 2000 and after | – | – | – | 54 (47–62) (n = 1,757; k = 6) |

| Prisoner type | ||||

| Remand | 21 (18–25) (n = 1,502; k = 4) | – | – | – |

| Sentenced | 33 (29–37) (n = 8,808; k = 7) | – | – | – |

| Interviewer | ||||

| Psychiatrist | 23 (19–26) (n = 2,265; k = 6) | – | – | – |

| Other | 30 (26–35) (n = 9,746; k = 8) | – | – | – |

Publication bias

There was no evidence of publication bias overall, and in subgroups stratified by sex apart from drug use disorder in male prisoners, where there was non-significant evidence of publication bias in the funnel plot analysis (Egger’s test, t=2.19, SE(t)=4.27, p=0.051) [37, 38, 40–42, 44, 47, 48, 50–52, 57, 60]. Visual analysis of the funnel plot suggested asymmetry, but appeared to be mostly attributable to one study [60] with a high prevalence and large standard error, which when removed did not suggest clear publication bias (Appendix D).

Discussion

This updated systematic review of the prevalence of substance use disorder in prisoners is based on 24 studies and 18,388 individuals in 10 countries. In addition, we identified 5 studies in juvenile prisoners and 2 investigations in LMI countries. The sample size in this update is more than double of that a previous systematic review [11], which identified relevant prevalence studies until 2004, and allowed for an investigation of sources of heterogeneity between included studies.

We report two main findings. The first is that alcohol use disorder was highly prevalent in prisoners with a pooled estimate of 24% (95% CI 21–27). In men, the lowest estimate suggests one in six (or 16%) met the threshold for alcohol use disorder on arrival into prison, and in women it was one in ten. By way of comparison, in the US, community rates of past year alcohol use disorder were estimated at 8.7% for men and 4.6% in women in 2013 [62]. According to the Global Burden of Disease 2015 Study, global prevalence of alcohol use disorder was 1.5% for males and 0.3% for females (0.9% for both sexes) [63]. The second major finding was that drug use disorder was as high as the alcohol estimates, and possibly higher in female prisoners with a pooled estimate of 51% (95% CI 43–58). Importantly, the lowest prevalence study in women found that 30% had a drug use disorder. This can be contrasted with US community samples, where 3.4% of men and 1.9% women had such a disorder [62] and 0.8% in men and 0.4% in women (0.6% for both sexes) worldwide [63].

We investigated sources of heterogeneity more carefully than previous work, which led to a number of potentially important findings. First, using meta-regression, we found evidence of increasing drug use disorder in prison studies over the past three decades. This is in contrast with community trends in some high-income countries such as the US where drug use disorder has not increased (and alcohol reduced slightly) between 2000 and 2013 [64]. Second, two other study characteristics were associated with significant variations in prevalence. Having a higher participation rate was associated with lower rates in drug use disorder, and the higher rates of drug use disorders in women prisoners. Being assessed by a psychiatrist was also linked with lower alcohol use disorder prevalence in subgroup analyses, although the confidence intervals overlapped. This should inform the interpretation of single studies, particularly if used for service planning and development. One possible explanation for heterogeneity that we did not investigate are the community baseline rates of substance use disorders, and future work could examine this using comparable measures of drug and alcohol use such as the ongoing Global Burden of Disease [63]. In addition, the reported high prevalence range of 30-56% for substance use disorder in LMI countries needs further research as it was only based on 2 investigations.

There are a number of implications that arise from this updated meta-analysis. First, it highlights the opportunity that jails and prisons represent to treat substance use disorders [65]. The high prevelances underscore the importance of evidence-based interventions being available to all individuals entering custody. Four areas should be considered to improve management of substance use disorders in prisoners. First, prison arrival centres need to have systems in place to identify individuals with high treatment needs, and treatments should be matched to individual needs [65]. Second, acute detoxification management should be available to all entrants to custody, which may include short-term prescription of benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal [66], and symptomatic treatment of withdrawal from other substances that may include opioid agonists (such as methadone or buprenorphine). Detoxification programmes may benefit from the use of clinical tools to document withdrawal symptoms [67]. Third, combination pharmacological and psychosocial treatments should be available, considering the high prevalences and the subsequent effects on adverse outcomes, including mortality after release and violent reoffending [68, 69]. Finally, considering the high relapse rates, programmes need to link prisoners with community services. Structured, simple and scalable tools to identify those at highest risk [70], and case management [71] may assist in this process. A second implication from the review is that prevalence research needs to consider some areas of improvement. These include separating prevalences by drug and alcohol use disorder, and also providing information stratified by sex and prisoner status (i.e. sentenced or not). Baseline information on socio-demographic and criminal history characteristics (such as those listed in Table 1, including the sample’s age structure, and index offence) should be provided in new studies, and supplemented with more clinically informative information, such comorbidities with mental illness [72] and chronic pain, prevalence by individual drugs, and most recent treatment. At the same time, as there are now at least 24 studies on prevalence on over 18,000 prisoners, and whether new research should prioritise how treatment can be most effectively delivered to prisoners and former prisoners needs to be considered by funding agencies, researchers, and government agencies in criminal justice and public health.

A number of limitations to this review need to be considered. First, there was variation in the diagnostic tools and interviewers used to assess substance use disorders, and we found that psychiatrist interviewers were associated with lower prevalences for alcohol use disorder. To reflect this clinical and statistical heterogeneity, we also reported prevalence ranges. Second, as we focused on substance use disorders on prison entry, these estimates may not reflect treatment needs later in prison or on prison release, where novel psychoactive substances are increasingly problematic and may require different treatment approaches [73]. In addition, the misuse of prescribed medication such as painkillers, antiepileptics and anxiolytics inside custody needs to be considered, and may further increase treatment needs. Finally, some of the subgroup analyses were based on less than 10 studies, and should be interpreted with caution.

In summary, the high prevalence of alcohol and drug use disorders in prisoners remains a key challenge for prison health. Tackling this will likely require interventions at all stages of the criminal justice process – from identifying and treating withdrawal in police custody [74] and on arrival to prison, to opiate maintenance and other treatments during any period in prison [68], to community links being made and integrated treatment provided on release [75]. Comprehensive strategies to prevent relapse of substance dependence is likely to reduce premature mortality, recidivism and subsequent return to prison.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Prevalence of alcohol use disorder in male and female prisoners on reception to prison (ES=prevalence estimates)

Figure 3.

Prevalence of drug use disorder in male and female prisoners on reception to prison (ES=prevalence estimates)

Acknowledgements

We thank J Borrill, BK Jordan, EM Kouri, C Lo, J Marquart, L Teplin and T Weaver for kindly providing additional data from their studies for the initial review. We are grateful to T Butler, H Kennedy, N Hoffmann, A Kopak, A Dixon and B Wright for providing further information about their studies for the update. In addition, D Black, A Robertson, A Armiyau, R Almeida, F Sahajian, J Baillargeon and J Sigurðsson helpfully responded to queries.

Funding Sources

Prof. Seena Fazel is funded by the Wellcome Trust (095806). The Trust had no direct involvement in the conduct of this research

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Pratt D, Appleby L, Piper N, Webb R, Shaw J. Suicide in recently released prisoners: a case-control study. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:827–835. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinner SA, Forsyth S, Williams G. Systematic review of record linkage studies of mortality in ex-prisoners: why (good) methods matter. Addiction. 2013;108:38–49. doi: 10.1111/add.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang Z, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Fazel S. Substance use disorders, psychiatric disorders, and mortality after release from prison: a nationwide longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:422–430. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00088-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baillargeon J, Binswanger IA, Penn JV, Williams BA, Murray OJ. Psychiatric Disorders and Repeat Incarcerations: The Revolving Prison Door. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:103–109. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang Z, Larsson H, Lichtenstein P, Fazel S. Psychiatric disorders and violent reoffending: a national cohort study of convicted prisoners in Sweden. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:891–900. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivlin A, Hawton K, Marzano L, Fazel S. Psychiatric disorders in male prisoners who made near-lethal suicide attempts: case-control study. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:313–319. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.077883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teasdale B, Daigle LE, Hawk SR, Daquin JC. Violent Victimization in the Prison Context: An Examination of the Gendered Contexts of Prison. International journal of offender therapy and comparative criminology. 2016;60:995–1015. doi: 10.1177/0306624X15572351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steiner B, Wooldredge J. Inmate versus environmental effects on prison rule violations. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2008;35:438–456. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oser CB, Knudsen HK, Staton-Tindall M, Taxman F, Leukefeld C. Organizational-level correlates of the provision of detoxification services and medication-based treatments for substance abuse in correctional institutions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;103:S73–S81. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Health Do. The Patel report: Reducing drug-related crime and rehabilitating offenders. London, UK: Department of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fazel S, Bains P, Doll H. Substance abuse and dependence in prisoners: a systematic review. Addiction. 2006;101:181–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PROSPERO - International prospective register of systematic reviews. University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carra G, Giacobone C, Pozzi F, Alecci P, Barale F. [Prevalence of mental disorder and related treatments in a local jail: a 20-month consecutive case study] Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2004;13:47–54. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00003225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown K, Cullen A, Kooyman I, Forrester A. Mental health expertise at prison reception. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2015;26:107–115. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black DW, Gunter T, Loveless P, Allen J, Sieleni B. Antisocial personality disorder in incarcerated offenders: Psychiatric comorbidity and quality of life. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2010;22:113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horn M, Potvin S, Allaire J-F, Côté G, Gobbi G, Benkirane K, et al. Male Inmate Profiles and Their Biological Correlates. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59:441–449. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou J, Witt K, Zhang Y, Chen C, Qiu C, Cao L, et al. Anxiety, depression, impulsivity and substance misuse in violent and non-violent adolescent boys in detention in China. Psychiatry Res. 2014;216:379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langeveld H, Melhus H. [Are psychiatric disorders identified and treated by in-prison health services?] Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2004;124:2094–2097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart D. Drug use and perceived treatment need among newly sentenced prisoners in England and Wales. Addiction. 2009;104:243–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proctor SL, Kopak AM, Hoffmann NG. Compatibility of current DSM-IV and proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for cocaine use disorders. Addict Behav. 2012;37:722–728. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacAskill S, Parkes T, Brooks O, Graham L, McAuley A, Brown A. Assessment of alcohol problems using AUDIT in a prison setting: more than an 'aye or no' question. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kissell A, Taylor PJ, Walker J, Lewis E, Hammond A, Amos T. Disentangling Alcohol-Related Needs Among Pre-trial Prisoners: A Longitudinal Study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49:639–644. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agu056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lintonen TP, Vartiainen H, Aarnio J, Hakamäki S, Viitanen P, Wuolijoki T, et al. Drug Use Among Prisoners: By Any Definition, It's a Big Problem. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46:440–451. doi: 10.3109/10826081003682271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tavares GP, Scheffer M, Almeida RMMd. Drogas, violência e aspectos emocionais em apenados [Drugs, violence and emotional aspects in prisoners.] Psicol Reflex Crit. 2012;25:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mundt AP, Kastner S, Larraín S, Fritsch R, Priebe S. Prevalence of mental disorders at admission to the penal justice system in emerging countries: a study from Chile. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2015;1:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S2045796015000554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Köhler D, Heinzen H, Hinrichs G, Huchzermeier C. The Prevalence of Mental Disorders in a German Sample of Male Incarcerated Juvenile Offenders. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2009;53:211–227. doi: 10.1177/0306624X07312950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vreugdenhil C, Doreleijers TAH, Vermeiren R, Wouters LFJM, Van Den Brink W. Psychiatric Disorders in a Representative Sample of Incarcerated Boys in The Netherlands. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:97–104. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McClelland GM, Elkington KS, Teplin LA, Abram KM. Multiple Substance Use Disorders in Juvenile Detainees. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 43:1215–1224. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000134489.58054.9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dixon A, Howie P, Starling J. Trauma Exposure, Posttraumatic Stress, and Psychiatric Comorbidity in Female Juvenile Offenders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 44:798–806. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000164590.48318.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plattner B, Giger J, Bachmann F, Brühwiler K, Steiner H, Steinhausen H-C, et al. Psychopathology and offense types in detained male juveniles. Psychiatry Res. 2012;198:285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grant BF, Harford TC, Muthén BO, Yi H-Y, Hasin DS, Stinson FS. DSM-IV alcohol dependence and abuse: Further evidence of validity in the general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:154–166. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett Sheehan K, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, et al. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12:232–241. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:147–153. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson SG, Higgins JP. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med. 2002;21:1559–1573. doi: 10.1002/sim.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bushnell JA, Bakker LW. Substance use Disorders among Men in Prison: A New Zealand Study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31:577–581. doi: 10.3109/00048679709065080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mcclellan DS, Farabee D, Crouch BM. Early Victimization, Drug Use, and Criminality: A Comparison of Male and Female Prisoners. Crim Justice Behav. 1997;24:455–476. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohan D, Scully P, Collins C, Smith C. Psychiatric disorder in an Irish female prison. Crim Behav Ment Health. 1997;7:229–235. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butler T, Allnutt S. Mental illness among New South Wales prisoners. Corrections Health Service; Sydney, NSW: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curtin K, Monks S, Wright B, Duffy D, Linehan S, Kennedy HG. Psychiatric morbidity in male remanded and sentenced committals to Irish prisons. Ir J Psychol Med. 2009;26:169–173. doi: 10.1017/S079096670000063X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarlon E, Duburcq A, Neveu X, Morvan-Duru E, Tremblay R, Rouillon F, et al. Imprisonment, alcohol dependence and risk of delusional disorder: A cross-sectional study. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2012;60:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sterne JAC, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: Guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins JJ, Bailey SL, Phillips CD, Craddock A, Research Triangle I., Ctr for Social R et al. The relationship of mental disorder to violent behavior. NC: Research Triangle Institute, Center for Social Research and Policy Analysis; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daniel AE, Robins AJ, Reid JC, Wilfley DE. Lifetime and Six-Month Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders among Sentenced Female Offenders. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1988;16:333–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jordan B, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Caddell JM. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among incarcerated women: Ii. convicted felons entering prison. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:513–519. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830060057008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lo CC, Stephens RC. Drugs and Prisoners: Treatment Needs on Entering Prison. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26:229–245. doi: 10.1081/ada-100100602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mason D, Birmingham L, Grubin D. Substance use in remand prisoners: a consecutive case study. BMJ. 1997;315:18–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7099.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marquart JW, Brewer VE, Simon P, Morse EV. Lifestyle factors among female prisoners with histories of psychiatric treatment. J Crim Justice. 2001;29:319–328. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peters RH, Greenbaum PE, Edens JF, Carter CR, Ortiz MM. Prevalence of DSM-IV Substance Abuse and Dependence Disorders Among Prison Inmates. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1998;24:573–587. doi: 10.3109/00952999809019608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith C, O'neill H, Tobin J, Walshe D, Dooley E. Mental disorders detected in an Irish prison sample. Crim Behav Ment Health. 1996;6:177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Teplin LA. Psychiatric and substance abuse disorders among male urban jail detainees. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:290–293. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.2.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teplin LA, Abram KM, Mcclelland GM. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among incarcerated women: I. pretrial jail detainees. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:505–512. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830060047007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Proctor SL. Substance Use Disorder Prevalence among Female State Prison Inmates. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38:278–285. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.668596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wright B, Duffy D, Curtin K, Linehan S, Monks S, Kennedy HG. Psychiatric morbidity among women prisoners newly committed and amongst remanded and sentenced women in the Irish prison system. Ir J Psychol Med. 2006;23:47–53. doi: 10.1017/S0790966700009575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mir J, Kastner S, Priebe S, Konrad N, Ströhle A, Mundt AP. Treating substance abuse is not enough: Comorbidities in consecutively admitted female prisoners. Addict Behav. 2015;46:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bulten E, Nijman H, Van Der Staak C. Psychiatric disorders and personality characteristics of prisoners at regular prison wards. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2009;32:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jones GY, Hoffmann NG. Alcohol dependence: international policy implications for prison populations. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2006;1:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-1-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoffmann NG, Kopak AM. How Well Do the DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder Designations Map to the ICD-10 Disorders? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:697–701. doi: 10.1111/acer.12685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Einarsson E, Sigurdsson JF, Gudjonsson GH, Newton AK, Bragason OO. Screening for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and co-morbid mental disorders among prison inmates. Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63:361–367. doi: 10.1080/08039480902759184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stompe T, Brandstätter N, Ebner N, Fischer-Danzinger D. Psychiatrische Störungen bei Haftinsassen [Psychiatric disorders in prison inmates] J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;11:20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Behavioral Health Barometer: United States, 2014. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Institute For Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 (GBD 2015) Results. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Substance Abuse And Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taxman FS, Perdoni ML, Harrison LD. Drug treatment services for adult offenders: The state of the state. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32:239–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Amato L, Minozzi S, Vecchi S, Davoli M. Benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal. The Cochrane Library. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005063.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wakeman SE, Rich JD. Pharmacotherapy for substance use disorders within correctional facilities. In: Trestman B, Appelbaum K, Metzner J, editors. Oxford Textbook of Correctional Psychiatry. New York: OUP: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rich JD, Mckenzie M, Larney S, Wong JB, Tran L, Clarke J, et al. Methadone continuation versus forced withdrawal on incarceration in a combined US prison and jail: a randomised, open-label trial. The Lancet. 2015;386:350–359. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62338-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mitchell O, Wilson DB, Mackenzie DL. Does incarceration-based drug treatment reduce recidivism? A meta-analytic synthesis of the research. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2007;3:353–375. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fazel S, Chang Z, Fanshawe T, Långström N, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, et al. Prediction of violent reoffending on release from prison: derivation and external validation of a scalable tool. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:535–543. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00103-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kinner SA, Alati R, Longo M, Spittal MJ, Boyle FM, Williams GM, et al. Low-intensity case management increases contact with primary care in recently released prisoners: a single-blinded, multisite, randomised controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016 doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fazel S, Seewald K. Severe mental illness in 33 588 prisoners worldwide: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Br J Pscyhiatry. 2012;200:364–373. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.HM Inspectorate of Prisons. Changing patterns of substance misuse in adult prisons and service responses. London, England: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Payne-James JJ, Wall IJ, Bailey C. Patterns of illicit drug use of prisoners in police custody in London, UK. J Clin Forensic Med. 2005;12:196–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jcfm.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomas EG, Spittal MJ, Heffernan EB, Taxman FS, Alati R, Kinner SA. Trajectories of psychological distress after prison release: implications for mental health service need in ex-prisoners. Psychol Med. 2016;46:611–621. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.