Long Abstract

MRI provides a sensitive and specific imaging tool to detect acute ischemic stroke by means of a reduced diffusion coefficient of brain water. In a rat model of ischemic stroke, differences in quantitative T1 and T2 MRI relaxation times (qT1 and qT2) between the ischemic lesion (delineated by low diffusion) and the contralateral non-ischemic hemisphere increase with time from stroke onset. The time dependency of MRI relaxation time differences is heuristically described by a linear function and thus provides a simple estimate of stroke onset time. Additionally, the volumes of abnormal qT1 and qT2 within the ischemic lesion increase linearly with time providing a complementary method for stroke timing. A (semi)automated computer routine based on the quantified diffusion coefficient is presented to delineate acute ischemic stroke tissue in rat ischemia. This routine also determines hemispheric differences in qT1 and qT2 relaxation times and the location and volume of abnormal qT1 and qT2 voxels within the lesion. Uncertainties associated with onset time estimates of qT1 and qT2 MRI data vary from ± 25 min to ± 47 min for the first 5 hours of stroke. The most accurate onset time estimates can be obtained by quantifying the volume of overlapping abnormal qT1 and qT2 lesion volumes, termed ‘Voverlap’ (± 25 min) or by quantifying hemispheric differences in qT2 relaxation times only (± 28 min). Overall, qT2 derived parameters outperform those from qT1. The current MRI protocol is tested in the hyperacute phase of a permanent focal ischemia model, which may not be applicable to transient focal brain ischemia.

Keywords: Neuroscience, Brain, Stroke, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Onset Time

Introduction

Brain tissue is particularly vulnerable to ischemia due to the high dependence of the oxidative phosphorylation for ATP synthesis and limited energy reserves. Ischemia results in subtle time-dependent ionic changes in intracellular and extracellular spaces that lead to redistribution of brain water pools, release of excitotoxic neurotransmitters and ultimately initiation of destructive processes 1. In focal ischemia, tissue damage spreads beyond the initial core if blood flow is not restored within a certain time frame 2. The time of stroke onset is currently one of the key criteria in clinical decisions for the pharmacotherapy of ischemic stroke, including recanalization by thrombolytic agents 3. Consequently, many patients are automatically ineligible for thrombolytic therapy due to unknown symptom onset time, owing to the stroke occurring during sleep (‘wake-up stroke’), lack of witness, or being unaware of symptoms 4,5. A procedure that determines the time of stroke onset is therefore required so that such patients may be considered for thrombolysis.

MRI probes water in vivo. Dynamics of which are severely perturbed by acute ischemic energy failure 6. Most notably, the diffusion of water governed by translational (thermal) motion of water molecules is reduced in the early moments of ischemia due to the energy failure 7. This in turn results in anoxic depolarization of neural cells 8. Diffusion MRI (DWI) has become a gold standard diagnostic imaging modality for acute stroke 9. The DWI signal increases rapidly in response to ischemia allowing ischemic tissue to be identified but does not show any time-dependency during the first few hours of ischemic stroke 10. Likewise, quantitative measures of water diffusion such as the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) or the trace of the diffusion tensor (Dav) decrease rapidly in ischemic tissue, but show no relationship with time from stroke onset in animal stroke models 10 and patients 11.

Quantitative MRI (qMRI) relaxation parameters, qT1, qT2 and qT1ρ, are governed by rotational motion and the exchange of water hydrogen atoms and show complex time-dependent changes in brain parenchyma following ischemic energy failure 6. Such time-dependent changes enabled stroke onset time to be estimated in in patients 12 and animal models of ischemia 13–15. In rat focal stroke, qT1ρ increases almost instantaneously after ischemia onset and continues linearly for at least 6 hours 13,14. qT1 relaxation times also increase in a time-dependent fashion in ischemic brain tissue which can be described by two time constants: an initial fast phase followed by a slow phase lasting for hours 8,16. Because of this biphasic increase, the use of qT1 in stroke timing may be more complicated than that of qT1ρ MRI 15. qT2 relaxation times also show a bi-phasic change in rat focal stroke, whereby there is an initial shortening within the first hour, followed by a linear increase with time 13. The initial shortening can be explained by two parallel running factors including: (i) the buildup of deoxyhemoglobin resulting in the so-called ‘negative blood oxygenation level dependent effect’ and (ii), the shift of extracellular water into the intracellular space 17,18. The time-dependent increase in qT2 is likely due to cytotoxic and/or vasogenic edema with subsequent breakdown of intracellular macromolecular structures 18. Both qT1ρ and qT2 data provide accurate estimates of stroke onset time in preclinical models 14. qT2 12 and T2-weighted signal intensities 19,20 have also been exploited for stroke onset time estimation in clinical settings.

In addition to hemispheric differences in quantitative relaxation times, the spatial distribution of elevated relaxation times within the ischemic region may also serve as surrogates for stroke onset time 14. In rat models of stroke, regions with elevated qT1ρ, qT2 and qT1 relaxation times are initially smaller than the diffusion defined ischemic lesion but increase with time 14,15,21. Hence quantification of the spatial distribution of elevated relaxation times as a percentage of the size of the ischemic lesion also enables stroke onset time to be estimated 14,15. Here we describe the protocol to determine stroke onset time in a rat model of stroke using qMRI parameters.

Protocol

Animal procedures were conducted according to European Community Council Directives 86/609/EEC guidelines and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Finland.

1. Animal Model

-

1.1.

Anesthetize male Wistar rats weighing 300 – 400 g with isoflurane in N2/O2 flow (70%/30%) through a facemask for the duration of the operation and MRI experiments. Induce anesthesia in ventilated hood. Maintain isoflurane levels between 1.5 and 2.4%. Lack of response to pinch reflex is taken as a sign of sufficient depth for surgical anesthesia. Monitor depth of anesthesia during MRI from breathing frequency via a pneumatic pillow under the torso (SA Instruments Inc, Stony Brook, NY). Use isoflurane scavenger attached to magnet bore.

-

1.2.

Perform permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) to induce focal ischemic stroke. Use the intraluminal thread model for MCAO and carry out the operation according to methods given by Longa et al. 22.

-

1.2.1.

Leave the occluding thread (silicon-PTFE tempered monofil filament, diameter 0.22 mm) in place for the duration of the MRI experiment.

-

1.2.1.

-

1.3.

Analyze arterial blood gases and pH (e.g. blood analyser i-Stat Co, East Windsor, NJ, USA)

-

1.3.1.

During MRI monitor: breathing rate with the pneumatic pillow placed under the torso and rectal temperature using a rectal temperature monitoring system (SA Instruments Inc, NY). Maintain core temperature close to 37 °C using a water heating pad under the torso.

-

1.3.2.

Immediately after MCAO, secure rat in a cradle at the center of the magnet bore using a rat head holder (RAPID Biomedical GmbH, Germany). Inject 2 mL of saline intraperitoneally before transferring the rats into the magnet bore.

-

1.3.1.

2. MRI

-

2.1.

Acquire MRI data using a 9.4T/31 cm (with the 12 cm gradient insert) horizontal magnet interfaced to a Direct Drive console (Agilent, CA) equipped with an actively decoupled linear volume transmitter and quadrature receiver coil pair (RAPID Biomedical GmbH, Germany).

-

2.2.

Scan each rat for up to 5 hours post MCAO. At hourly intervals (60, 120, 180, 240 min post MCAO), acquire 12 congruently sampled (0.5 mm slice-gap, slice thickness = 1 mm, field of view = 2.56 cm x 2.56 cm) coronal slices of the trace of diffusion tensor (2.2.1.), Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill T2 (2.2.2.) and Fast Low Angle Shot T1 (2.2.3.).

-

2.2.1.

Obtain the trace of the diffusion tensor images (Dav= 1/3 trace [D]) with three bipolar gradients along each axis (the duration of the diffusion gradient = 5 ms, the diffusion time = 15 ms) and three b-values (0, 400 and 1400 s/mm-2s), where, Δ = 15 ms, ∂ = 5 ms, echo time (TE) = 36 ms, repetition time (TR) = 4000 ms and acquisition time = 7.36 minutes.

-

2.2.2.

Obtain the Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill T2 sequence with 12 echoes for T2 quantification, where echo-spacing = 10 ms, TR = 2000 ms and acquisition time = 4.20 minutes.

-

2.2.3.

Obtain the Fast Low Angle Shot (FLASH) for T1, where the time from inversion to the first FLASH sequence (T10) is 7.58 ms, with 600 ms increments of 10 inversions up to 5407.58 ms, TR = 5.5 ms, time between inversion pulses (Trelax) = 10 s and acquisition time = 8.20 minutes.

-

2.2.1.

3. Image Processing

-

3.1.

Computation of relaxometry and ADC maps: Compute qT2, qT1 and ADC maps using Matlab functions provided on University of Bristol website [DOI: pending], for which the input is a file path to the location of the MRI data.

-

3.1.1.

For T2 data, apply Hamming filtering in k-space prior to reconstruction of images (or in image domain by convolution, with equivalent results but computationally less efficient). Compute qT2 maps by taking the logarithm of each time series and solving on a voxel-wise basis by linear least-squares. (A bi-exponential fit can also be performed to the T2 decays, but the voxel-wise F-tests tests revealed that voxels within the image for which additional parameters could not be justified).

-

3.1.2.

For T1 data, apply Hamming filtering in k-space prior to reconstruction of images. Perform T1 fitting according to methods given in 23. To deal with the problem of unknown sign (due to the use of magnitude images), the lowest-intensity point may be either excluded, or estimated in the course of fitting with similar results.

-

3.1.3.

For Diffusion-weighted data, apply Hamming filtering by convolution in image domain (this is more straightforward due to the segmented k-space trajectory). Fit ADC maps by the method in13.

-

3.1.1.

-

3.2.

Identification of ischemic tissue

-

3.2.1.

Identify ischemic tissue on reciprocal Dav images (1/Dav) as this provides clear contrast for lesion identification. To generate ischemic volumes of interest (VOI), define ischemic tissue as voxels with values one median absolute deviation above the median value of the whole-brain 1/Dav distribution. To identify homologous regions in the non-ischemic hemisphere, reflect the ischemic VOI about the vertical axis. Manually adjust non-ischemic VOIs to avoid including voxels containing cerebrospinal fluid.

-

3.2.2.In order to determine the relationship of qT1 and qT2 with time post MCAO, for each rat and time-point load the ischemic and non-ischemic VOIs onto qT1 and qT2 maps. Extract mean relaxation times and calculate the percentage difference in qT1 and qT2 between hemispheres (ΔT1 and ΔT2) using the following equation:

Where Tx is the chosen parameter, qT1 or qT2. refers to the mean relaxation time of the ischemic VOI and the mean relaxation time in the non-ischemic VOI. The non-ischemic VOI should be used so that each rat serves as its own control. -

3.2.3.

Use the following criteria to identify voxels with elevated qT1 and qT2: any voxels within the ischemic VOI with relaxation times exceeding the median relaxation time of the qT1 or qT2 distribution in the non-ischemic VOI by more than one half-width at half-maximum (HWMH). These criteria mean relaxation times must have been in the 95th percentile or higher to be classified as ‘high’. Use of the median relaxation time of the non-ischemic VOI allows each rat to serve as its own control.

-

3.2.4.

To picture the spatial distribution of relaxation time changes within regions of decreased diffusion, identify and color code voxels with elevated qT1 or qT2 as well as voxels with both elevated qT1 and qT2 termed ‘qT1 and qT2 overlap’.

-

3.2.5.

To determine the size of the lesion according to qT1 and qT2, compute the parameter f ( as introduced by Knight et al. 18) from MRI data acquired for each rat and time-point. f1 and f2 represent the number of voxels with high qT1 or qT2 (respectively) as a percentage of the size of the ischemic VOI.

Use the following equation to calculate f1 and f2:

Where x refers to the relaxation time (qT1 or qT2), NHigh refers to the number of ‘high’ relaxation time voxels in the ischemic VOI, NLow is the number of ‘low’ relaxation time voxels in the ischemic VOI and NLesion, the total number of voxels within the ischemic VOI. Criteria for identifying voxels with elevated qT1 and qT2 are outlined in section 3.2.3. ‘Low’ voxels are voxels with relaxation times less than the median qT1 or qT2 of the non-ischemic VOI by one HWHM. The subtraction of NLow allows for decreases in relaxation times due to ischemia or other pathologies 17. Determine the extent of ‘qT1 and qT2 overlap’ by calculating the volume of overlapping elevated qT1 and qT2 as a percentage of whole brain volumes, hereby referred to as ‘VOverlap’. Use the following equation:

Where, NOverlap refers to the number of voxels within the ischemic VOI with both ‘high’ qT1 and ‘high’ qT2 NWholebrain and represents the total number of voxels in the whole rat brain. Determine the number of voxels in the rat brain by manually creating a VOI around the whole brain on qT2 relaxometry maps.

-

3.2.1.

4. Verification of ischemic lesion with triphenyletrazolium chloride (TTC)

-

4.1.

Immediately after decapitation, carefully extract the rat brain from the skull. Complete this procedure within 10 minutes from the time the rat was decapitated.

-

4.2.

Store brains in refrigerated 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) before using a rat brain slicer matrix to section the brain into serial 1 mm-thick coronal slices.

-

4.3.

After sectioning, incubate each brain slice in 20 mL PBS containing TTC at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark, as recommended in 24. Although 1% TTC concentration is acceptable, use 0.5% for improved contrast.

-

4.3.1.

Cover the containers of the sections in foil to keep it dark.

-

4.3.1.

-

4.4.

After incubation, remove the TTC solution using a pipette and wash slices in three changes of PBS.

-

4.5.

Immediately photograph slices using a standard light microscope and a digital camera.

5. Statistical Analysis

-

5.1.

Carry out statistical analysis using Matlab and statistical software such as Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) or Microsoft Excel.

-

5.2.

Determine relationship of MR parameters with time

-

5.2.1.

Perform Pearson’s correlations on pooled rat data to determine the relationship of ΔT1, ΔT2, f1 and f2 and VOverlap with time post MCAO.

-

5.2.2.

For parameters that show a significant linear relationship (p < .05), perform linear least square regression to determine whether stroke onset time can be predicted by quantifying the parameter of interest. Use the root mean square error (RMSE) to assess the accuracy of onset time estimates.

-

5.2.1.

-

5.3.

Quantification of lesion size

-

5.3.1.

To compare lesion sizes according to different qMRI parameters, conduct one-way related ANOVAs and Fisher’s least significant difference post-hoc on the average number of voxels in the ischemic VOI and the average number of voxels with high qT1 and qT2. Differences are considered significant at p < .05. If sphericity assumptions are not met according to Mauchly’s sphericity test, degrees of freedom and significance values should be corrected according to Greenhouse Geisser estimates.

-

5.3.1.

Representative Results

Across rats the blood gas profiles were as follows: SO2 95.8 ±3.2%, PaCO2 51.6 ± 2.9 mmHg, and pH 7.30± 0.04.

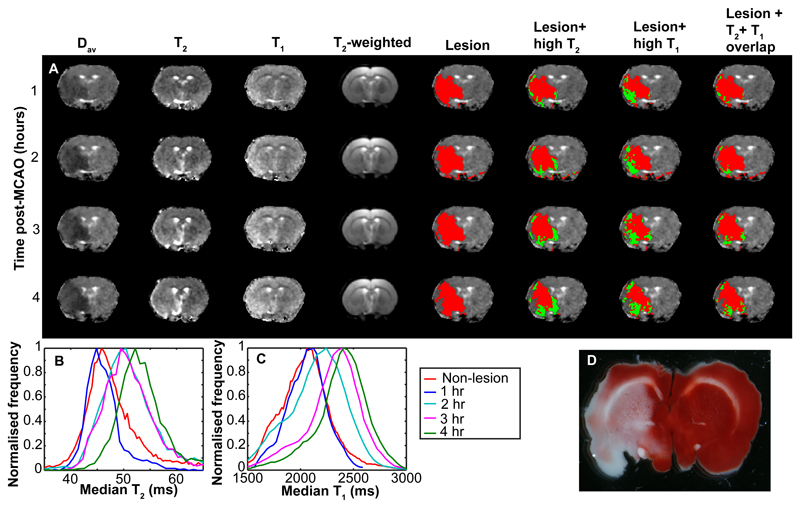

Typical Dav, qT2 and qT1 images from a central slice of a representative rat at 4 time points post MCAO are shown in the first 3 panels of Figure 1a. Images in the other panels of Figure 1 show the automatically detected ischemic lesion in red and regions within the ischemic lesion with elevated qT1, qT2 and regions with Voverlap are shown in green. Up to 2 hours post-MCAO, regions with high qT1 within the ischemic lesion were significantly larger than high qT2 (p < .01), but converged with time (Figure 1). The ischemic lesion by Dav was also larger than regions of high qT1 (p < .05) and qT2 (p < 05) in the first two hours.

Figure 1. Changes in qMRI parameters due to ischemic stroke in an example rat.

Panel (a) shows example qMRI images over a 4-hour period of ischemia. The first four columns show Dav maps, qT2 maps, qT1 maps and T2 weighted images respectively. Remaining columns show the Dav maps with various representations of the automatically segmented lesions. The automatically detected Dav lesion is shown in column 5 in red. In column 6 the Dav lesion is shown in red with voxels with high qT2 shown in green. In column 7 the Dav lesion is shown in red with high qT1 voxels shown in green. In column 8 the Dav lesion is shown in red with voxels with both elevated qT1 and qT2 (Voverlap) shown in green. Panel (b) shows the distribution of qT2 in the Dav lesion as a function of time post MCAO, as well as the non-lesion qT2 distribution at time zero. Panel (c) shows the corresponding qT1 distributions, the adjacent legend pertaining to both panels (b) and (c). Panel (d) shows a TTC-stained brain slice after the animal was sacrificed at 6 hours post-MCAO.

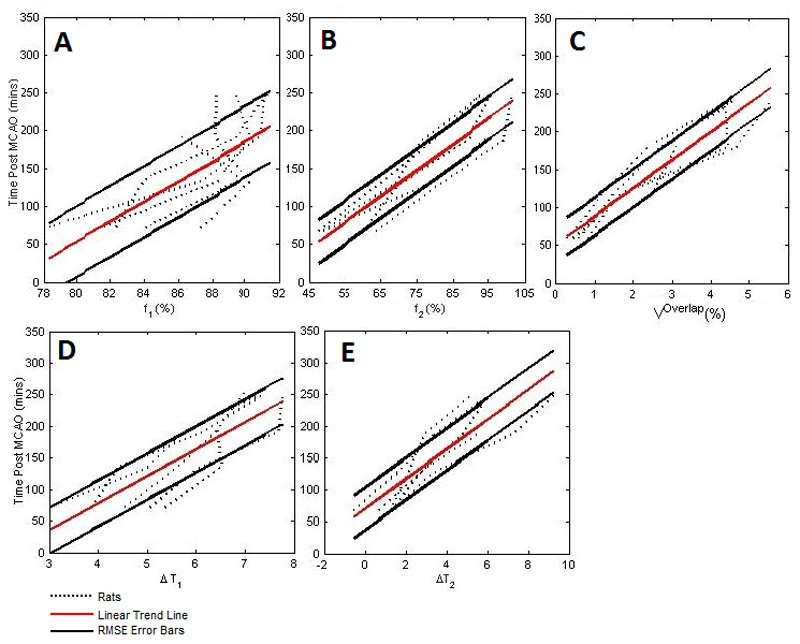

The time dependencies of qMRI parameters are shown in Figure 2. All qMRI parameters were significant predictors of time post MCAO (ΔT1: R2 = 0.71, ΔT2: R2 = 0.75, f1: R2 = 0.53, f2: R2 = 0.82, Voverlap: R2 = 0.87). Based on the RMSE for each parameter, uncertainties associated with estimates of time since stroke onset were ± 37 min for ΔT1, ± 28 min for ΔT2, ± 47 min for f1, ±34 min for f2, and ±25 min for Voverlap. Thus Voverlap gave the most accurate estimate of time since stroke onset.

Figure 2. The relationships between time post-MCAO and qMRI parameters relevant to the timing of ischemia.

Panel (a) shows f1,(b) the f2 parameter, (c), Voverlap, (d),ΔT1 and (e), ΔT2. Best fit for each parameter (solid red line) and RMSE error bars (solid black lines) are shown. Dotted lines represent each of the induvial 5 rats subjected to MCAO.

TTC staining of brains samples around 6 hours after MCAO verified irreversible ischemic damage predominantly in grey matter (Figure 1d).

Discussion

The current protocol for estimation of stroke onset time in rats uses quantitative diffusion and relaxation time MRI data rather than signal intensities of respective weighted MR contrast images19. Recent evidence points to inferior performance of image intensities in estimating stroke onset time 14, 25. In the ‘diffusion-positive’ stroke lesion our MRI protocol provides stroke onset times from qT1 and qT2 MRI data with an accuracy of half an hour or so. It is a general trend that qT2 data outperforms that of qT1. The best accuracy for onset time determination is obtained from the volume of overlapping elevated qT1 and qT2 (Voverlap).

The images in Figure 1 demonstrate that while the reduced diffusion coefficient appears rather uniform, regions with abnormal qT1 and qT2 are heterogeneously scattered within the ischemic lesion. This finding is in accordance with previous observations and is likely due to different sensitivities of these qMRI parameters to pathophysiological changes caused by ischemia 6. This suggests qMRI parameters may be informative of tissue status and supports notions that DWI over-estimates ischemic damage 26. Indeed, recent preclinical evidence points toward the heterogeneity of ischemic damage within diffusion defined lesions27. Thus the combination of diffusion, qT1 and qT2 potentially provides information on stroke onset time and tissue status, both of which are clinically useful for treatment decisions regarding patients with unknown onset.

Voverlap and f2 gave the most accurate estimates of stroke onset time. The benefit of quantifying relaxation times is that unlike signal intensities they are insensitive to inherent variations caused by technical factors such as magnetic field inhomogeneities and proton density 6, including the expected magnetic field variation within the ischemic lesion 18. Reduced uncertainty associated with onset time estimates of qT1 and f1 are likely due to the aforementioned bi-phasic response of qT1 to ischemia, which contributes to the shallow slope of the time-dependent qT1 change 8,15,16. The MRI data shown (Figure 2) are in accordance with previous works 13,14, in that the time courses of relaxation time differences between the ischemic and contralateral non-ischemic brain are adequately described by linear functions. It is, however, important to note that the underpinning hydrodynamic changes due to ischemia are not linear1,18.

The current MRI protocol for stroke timing is demonstrated in rat subjected to permanent ischemia using the Longa et al. procedure22. In our experience the Longa et al. procedure fails to induce MCAO in 10-20% of rats, however, as ADC is used to verify presence of ischemia, the experiments can be terminated prematurely. Failure to induce MCAO is often due to imperfect occluder thread. A further factor resulting in experimental failures is that MCAO is a severe procedure causing death of up to 20% of rats during a prolonged MRI session.

The stroke onset timing protocol applies only to permanent ischemia. In rat focal ischemia with reperfusion, the relationship between Dav and qT1 or qT2 will dissociate as Dav recovers, but for qT1 and qT2 may or may not, depending on duration of ischemia prior to reperfusion8, 28. Additionally, the evolution of ischemic damage is likely to be more variable in stroke patients due to individual differences in factors affecting microcirculation such as age and co-morbidities (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, heart disease). These factors will inevitably influence the time dependence of f1, f2 and Voverlap in human strokes and thus requires investigation in clinical settings.

To conclude, qMRI parameters provide estimates of stroke onset time. Voverlap and f2 provide the most accurate estimates and may also be informative of tissue status. qMRI could therefore be clinically beneficial in terms of aiding treatment decisions for patients with unknown onset time. An issue to be considered here is that the gray-to-white-matter ratio in rat brain is much higher than in humans, and hydrodynamics in these brain tissue types may vary18. Nevertheless, further investigation into the time dependence of f2, Voverlap and qT2 in hyper acute stroke patients is therefore warranted.

Supplementary Material

Short Abstract.

A protocol for stroke onset time estimation in a rat model of stroke exploiting quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (qMRI) parameters is described. The procedure exploits diffusion MRI for delineation of the acute stroke lesion and quantitative T1 and T2 (qT1 and qT2) relaxation times for timing of stroke.

Acknowledgements

BLM is a recipient of EPSRC PhD studentship and received a travel grant to University of Eastern Finland from the School of Experimental Psychology, University of Bristol. MJK is funded by the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute and by the Wellcome Trust international strategic support fund [ISSF2: 105612/Z/14/Z]. KTJ and OHJG are funded by Academy of Finland, UEF-Brain strategic funding from University of Eastern Finland and by Biocenter Finland. This work was supported by The Dunhill Medical Trust [grant number R385/1114].

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose

Contributor Information

Bryony. L. McGarry, Email: b.mcgarry@bristol.ac.uk.

Kimmo. T. Jokivarsi, Email: kimmo.jokivarsi@uef.fi.

Michael J. Knight, Email: mk13005@bristol.ac.uk.

Olli H. J. Grohn, Email: olli.grohn@uef.fi.

References

- 1.Siesjö BK. Mechanisms of ischemic brain damage. Crit Care Med. 1988;16:954–963. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198810000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astrup J, Siesjö BK, Symon L. Thresholds in cerebral ischemia: the ischemic penumbra. Stroke. 1981;12:723–725. doi: 10.1161/01.str.12.6.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hacke W, et al. Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet. 2004;363:768–774. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15692-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudd AG, et al. Stroke thrombolysis in England, Wales and Northern Ireland: how much do we do and how much do we need? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:14–19. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.203174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.George MG, et al. Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry Surveillance - four states, 2005-2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kauppinen RA. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of acute experimental brain ischemia. Prog NMR Spectr. 2014;80:12–25. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moseley ME, et al. Early detection of regional cerebral ischemia in cats: comparison of diffusion- and T2-weighted MRI and spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 1990;14:330–346. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910140218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kettunen MI, et al. Interrelations of T1 and diffusion of water in acute cerebral ischemia of the rat. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:833–839. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200012)44:6<833::aid-mrm3>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wintermark M, et al. Acute stroke imaging research roadmap. Stroke. 2008;39:1621–1628. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.512319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knight RA, Dereski MO, Helpern JA, Ordidge RJ, Chopp M. Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of evolving focal cerebral ischemia. Comparison with histopathology in rats. Stroke. 1994;25:1252–1261. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.6.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madai VI, et al. DWI intensity values predict FLAIR lesions in acute ischemic stroke. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siemonsen S, et al. Quantitative T2 values predict time from symptom onset in acute stroke patients. Stroke. 2009;40:1612–1616. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.542548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jokivarsi KT, et al. Estimation of the onset time of cerebral ischemia using T1ρ and T2 MRI in rats. Stroke. 2010;41:2335–2340. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.587394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers HJ, et al. Timing the ischemic stroke by 1H MRI: Improved accuracy using absolute relaxation times over signal intensities. NeuroReport. 2014;25:1180–1185. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGarry BL, et al. Stroke onset time estimation from multispectral quantitative magnetic resonance imaging in a rat model of focal permanent cerebral ischemia. Int JStroke. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1747493016641124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calamante F, et al. Early changes in water diffusion, perfusion, T1, and T2 during focal cerebral ischemia in the rat studied at 8.5 T. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41:479–485. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199903)41:3<479::aid-mrm9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gröhn OHJ, et al. Graded reduction of cerebral blood flow in rat as detected by the nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation time T2: A theoretical and experimental approach. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:316–326. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200002000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knight MJ, et al. A spatiotemporal theory for MRI T2 relaxation time and apparent diffusion coefficient in the brain during acute ischemia: Application and validation in a rat acute stroke model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36:1232–1243. doi: 10.1177/0271678X15608394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomalla G, et al. DWI-FLAIR mismatch for the identification of patients with acute ischemic stroke within 4.5 h of symptom onset (PRE-FLAIR): a multicenter observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:978–986. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70192-2. S1474-4422(11)70192-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petkova M, et al. MR imaging helps predict time from symptom onset in patients with acute stroke: implications for patients with unknown onset time. Radiology. 2010;257:782–792. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoehn-Berlage M, et al. Evolution of regional changes in apparent diffusion coefficient during focal ischemia of rat brain: the relationship of quantitative diffusion NMR imaging to reduction in cerebral blood flow and metabolic disturbances. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1995;15:1002–1011. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1995.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20:84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nekolla S, Gneiting T, Syha J, Deichmann R, Haase A. T1 maps by K-space reduced snapshot-FLASH MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992;16:327–332. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199203000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joshi CN, Jain SK, Murthy PS. An optimized triphenyltetrazolium chloride method for identification of cerebral infarcts. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 2004;13:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGarry BL, Rogers HJ, Knight MK, Jokivarsi KT, Gröhn OHJ, Kauppinen RA. Determining stroke onset time using quantitative MRI: High accuracy, sensitivity and specificity obtained from magnetic resonance relaxation times. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2016;6:60–65. doi: 10.1159/000448814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiehler J, et al. Severe ADC decreases do not predict irreversible tissue damage in humans. Stroke. 2002;33:79–86. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.100884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lestro Henriques I, et al. Intralesional Patterns of MRI ADC Maps Predict Outcome in Experimental Stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;39:293–301. doi: 10.1159/000381727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kettunen MI, Gröhn OHJ, Silvennoinen MJ, Penttonen M, Kauppinen RA. Quantitative assessment of the balance between oxygen delivery and consumption in the rat brain after transient ischemia with T2-BOLD magnetic resonance imaging. J Ceber Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:262–270. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.