Summary

Introduction

The association between intraoperative cardiovascular changes and perioperative myocardial injury has chiefly focused on hypotension during non-cardiac surgery. However, the relative influence of blood pressure and heart rate remains unclear. We investigated both individual and co-dependent relationships between intraoperative heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), and myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery (MINS).

Methods

Secondary analysis of the VISION study, a prospective international cohort study of non-cardiac surgical patients. Multivariable logistic regression analysis tested for associations between intraoperative HR and/or SBP and MINS, defined by an elevated serum troponin T adjudicated as due to an ischaemic aetiology, within 30 days after surgery. Pre-defined thresholds for intraoperative HR and SBP were: maximum HR >100 beats or minimum HR <55 per minute (bpm); maximum SBP >160 mmHg or minimum SBP <100 mmHg. Secondary outcomes were myocardial infarction and mortality within 30 days after surgery.

Results

After excluding missing data, 1,197/15,109 patients (7.9%) sustained MINS, 454/16,031 (2.8%) sustained myocardial infarction and 315/16,061 patients (2.0%) died within 30 days after surgery. Maximum intraoperative HR >100 bpm was associated with MINS (OR 1.27 [1.07–1.50]; p<0.01), myocardial infarction (OR 1.34 [1.05-1.70]; p=0.02) and mortality (OR 2.65 [2.06-3.41]; p<0.01). Minimum SBP <100 mmHg was associated with MINS (OR 1.21 [1.05–1.39]; p=0.01) and mortality (OR 1.81 [1.39-2.37]; p<0.01), but not myocardial infarction (OR 1.21 [0.98-1.49]; p=0.07). Maximum SBP >160 mmHg was associated with MINS (OR 1.16 [1.01–1.34]; p=0.04) and myocardial infarction (OR 1.34 [1.09-1.64]; p=0.01) but, paradoxically, reduced mortality (OR 0.76 [0.58-0.99]; p=0.04). Minimum HR<55 bpm was associated with reduced MINS (OR 0.70 [0.59 – 0.82]; p<0.01), myocardial infarction (OR 0.75 [0.58-0.97]; p=0.03) and mortality (OR 0.58 [0.41-0.81]; p<0.01). Minimum SBP <100mmHg with maximum HR >100 bpm was more strongly associated with MINS (OR 1.42 (1.15-1.76); p<0.01) compared with minimum SBP <100mmHg alone (OR 1.20 (1.03-1.40); p=0.02).

Discussion

Intraoperative tachycardia and hypotension are associated with MINS. Further interventional research targeting heart rate/blood pressure is needed to define the optimum strategy to reduce MINS.

Introduction

One in ten patients sustain myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery (MINS),1 characterized by a transient rise in serum troponin levels usually unaccompanied by any clinical or electrocardiographic signs/symptoms.2 Postoperative troponin elevation is strongly associated with death after surgery, which occurs in up to 1-4% of eight million surgical procedures carried out in the United Kingdom each year.1, 3–5 Although the aetiology of MINS remains unclear,6 numerous retrospective studies implicate extreme intraoperative changes in blood pressure and/or heart rate.7, 8 However, few of these studies have used an objective, subclinical marker of MINS.

Tachycardia and hypotension, either separately or in combination, may provoke MINS, via a presumed mechanism of oxygen supply-demand-imbalance.7–10 Although preoperative resting heart rate is associated with postoperative MINS, it is uncertain if this relationship continues during surgery.11 Attempts to control elevated heart rate with beta-blockers have consistently demonstrated a reduction in myocardial infarction; however, trials have also demonstrated an increase in mortality and stroke with perioperative beta-blocker treatment.12, 13 Moreover, the impact of the combination of intraoperative tachycardia and hypotension on MINS remains unclear. Similarly, how the duration of hemodynamic abnormalities influence the development of MINS is uncertain and under-investigated.14–17

In the largest prospective perioperative cohort of its kind, we tested whether high or low intraoperative heart rate or systolic blood pressure, in isolation or combination, were associated with MINS, myocardial infarction or mortality within 30 days after non-cardiac surgery in the VISION study cohort. In addition, we tested whether the duration of high or low heart rate/systolic blood pressure was associated with MINS within 30 days of non-cardiac surgery.

Methods

Study design

This was a secondary analysis of a prospective international observational cohort study, the Vascular Events in Non-cardiac Surgery Cohort Evaluation (VISION) study.1 The methods have been published previously and the study was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00512109).1, 11, 18, 19 This analysis was planned before taking custody of data; exposures and outcomes were defined a priori. Ethics committees or institutional review boards at each site reviewed and approved the protocol, and the research was consistent with the principles of the declaration of Helsinki. All participants or their designates provided written informed consent to take part in the study. Eight hospitals used deferred consent for patients who were unable to provide consent and had no next of kin available. Where it was not possible to approach the patient before surgery (e.g. emergency surgery), they were approached for written consent within 24 hours after the procedure. This report follows the STROBE guidelines for observational cohort studies.20

Participants

VISION study participants were aged 45 years or older, underwent non-cardiac surgery under general or regional anaesthesia, and stayed in hospital for at least one night. Patients were excluded if they refused to provide consent or if they had previously taken part in the VISION study.

Data collection

Data were collected prospectively by research personnel at each hospital before, during and after surgery. There was a follow-up visit or telephone call at 30 days after surgery. Medical records were reviewed prospectively and data were transcribed to standardized case report forms.

Exposure variables

Clinical staff measured heart rate and blood pressure before and during surgery as part of routine medical care according to local practice. Blood pressure was most often measured using the oscillometric, non-invasive, technique. During surgery the highest and lowest single measurements of heart rate and systolic blood pressure, duration of heart rate >100 bpm and <55 bpm, and duration of systolic blood pressure >160 mmHg and <100 mmHg, were recorded by reviewing the anesthetic charts or record. Duration was defined as the total time above or below the pre-defined thresholds during surgery, measured in minutes. Predefined and pragmatic thresholds for heart rate and blood pressure were chosen prospectively by consensus of VISION study investigators.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery (MINS), according to the VISION study definition: serum Troponin T (TnT) ≥0.03ng/mL within 30 days after surgery, adjudicated as due to an ischemic pathology, which excludes non-ischemic causes of transient troponin elevation.19, 21 TnT was measured using a Roche 4th generation Elecsys™ assay. Blood was sampled between six and twelve hours after surgery was completed, and then again on postoperative days one, two and three. In addition, investigators were encouraged to take additional blood samples if participants experienced an ischemic symptom within the 30-day postoperative period. Since TnT ≥0.04ng/mL was the accepted laboratory threshold at many hospitals when the study started, electrocardiograms were only routinely performed when troponin concentration reached this threshold. Echocardiograms were recommended in the absence of clinical signs or electrocardiographic evidence of myocardial ischemia. Patients with a serum troponin elevation <0.04 ng/mL were not investigated for evidence of myocardial ischemia. The secondary outcome was myocardial infarction within 30 days of surgery. Myocardial infarction was defined according to the third universal definition (serum troponin elevation in the presence of at least one of: ischemic symptoms; the development of new or presumed new Q waves, ST segment or T wave changes, or left bundle branch block on the electrocardiogram; or the finding of a new or presumed new regional wall motion abnormality on echocardiography).22 The tertiary outcome measure was all-cause mortality within 30 days after surgery.

Statistical analysis

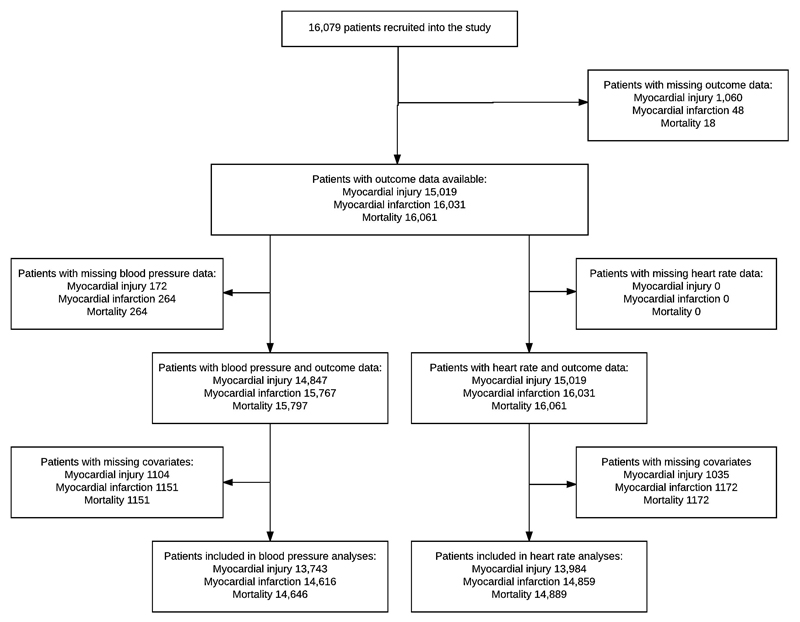

We used SPSS (IBM, New York) for the primary analysis, which we planned before taking custody of the data. Cases that were missing a record of highest or lowest intraoperative heart rate or systolic blood pressure, or outcome data were excluded from respective analyses by list-wise deletion (figure 1). We sorted and dichotomized the sample according to predefined thresholds for highest intraoperative heart rate (>100 bpm), lowest intraoperative heart rate (<55 bpm), highest intraoperative systolic blood pressure (>160 mmHg) and lowest intraoperative systolic blood pressure (<100 mmHg), and considered these as categorical variables. We presented demographic data stratified according to these groups. Continuous data that followed a normal distribution were presented as mean (standard deviation), continuous data that did not follow a normal distribution were presented as median (interquartile range), and binary categorical data as frequencies with percentages.

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram showing the number of cases included and excluded from each analysis

We used multivariable logistic regression analysis to test for associations between independent variables and MINS within 30 days after surgery. The reference groups were: heart rate ≤100 bpm for highest heart rate, heart rate ≥55 bpm for lowest heart rate, systolic blood pressure ≤160 mmHg for highest systolic pressure and systolic blood pressure ≥100 mmHg for lowest systolic pressure. Each multivariable model was adjusted for potentially confounding factors known to be associated with MINS, cardiovascular complications or mortality in other perioperative research: age (45-64, 65-75, >75 years), current atrial fibrillation, diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, previous stroke or transient ischemic attack, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR <30, 30-44, 45-60, >60 ml/min), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, neurosurgery, major surgery and urgent/emergency surgery were considered as categorical variables in the multivariable models.1, 23–25 Full definitions of covariates are listed in the supplementary file. These analyses were repeated for the secondary outcomes: mortality and myocardial infarction. The results of logistic regression analyses were presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals. For the primary (MINS) analysis the available sample size was 15,109. Given a type I error rate of 5% and a background incidence of MINS of 7.9%, we have >99% power to detect a 1.8% absolute difference in the incidence of MINS for participants with intraoperative heart rate >100 bpm. The minimum sample size required to detect an absolute difference of 1.8% in the primary outcome, assuming a type I error rate of 5% and power of 99% is 4,967 participants. Additional power calculations for the secondary and tertiary outcomes are in the supplement.

We suspected that any relationship between duration of intraoperative heart rate >100 bpm / <55 bpm or systolic blood pressure >160 mmHg / <100 mmHg and MINS would be non-linear. Therefore, we stratified duration of intraoperative heart rate >100 bpm / <55 bpm or systolic blood pressure >160 mmHg / <100 mmHg into quartiles and repeated the primary multivariable logistic regression analysis for quartiles of duration and repeated as for the primary analysis. Quartiles of duration were considered as ordered categorical variables. The reference categories were patients with ‘normal’ heart rate or systolic blood pressure, for example in the analysis of duration of heart rate >100 bpm, the reference group was patients with heart rate ≤100 bpm. We undertook post-hoc Bonferroni corrections to adjust for multiple comparisons. We were interested to see whether at least one episode (a single measurement) of ‘abnormal’ heart rate and at least one episode of ‘abnormal’ systolic blood pressure during the same operative episode influenced the degree of association with MINS. We therefore undertook a planned sensitivity analysis to examine the relationship between MINS and combinations of abnormal heart rate and systolic blood pressure during a single surgical procedure; since the data were not time-stamped, these were not necessarily concurrent/simultaneous episodes. We categorized the cohort according to combinations highest/lowest heart rate and highest/lowest systolic blood pressure: highest heart rate and highest systolic blood pressure / highest heart rate and lowest systolic blood pressure / highest systolic blood pressure and lowest heart rate / lowest systolic blood pressure and lowest heart rate. We repeated primary statistical analysis using these categorical variables.

Sensitivity analyses

To determine the influence of emergency surgery, we excluded all emergency cases and repeated the primary analyses. To determine the influence of atrial fibrillation, we repeated the primary heart rate analyses after excluding all cases with a previous history of atrial fibrillation. To determine the influence of heart rate modulating medications - beta-adrenoceptor antagonists (beta-blockers) and calcium channel blockers (diltiazem and verapamil) - we excluded patients that received a beta-blocker and/or a calcium channel blocker within 24 hours before surgery and repeated the primary analysis of heart rate. In the primary analysis the independent variables were high/low heart rate/systolic blood pressure categorised according to one or more episodes above/below pre-defined binary thresholds. However, this did not take account of instances where a patient had both high and low heart rate/systolic blood pressure episodes during surgery. Therefore we undertook a post-hoc sensitivity analysis. Heart rate was categorized as: 55-100 bpm, minimum heart rate < 55 bpm, maximum heart rate > 100 bpm, minimum heart rate < 55bpm and maximum heart rate > 100 bpm. Systolic blood pressure was categorized as: 100 – 160 mmHg, minimum systolic pressure < 100 mmHg, maximum systolic pressure > 160 mmHg, minimum systolic pressure < 100 mmHg and maximum systolic pressure > 160 mmHg. We repeated the primary analysis to test for association between these four-level heart rate/systolic blood pressure variables and MINS.

Results

16,079 patients were recruited to the VISION study from twelve hospitals in eight countries between 6th August 2007 and 11th January 2011.1 1,197/15,109 patients (7.9%) sustained MINS, 454/16,031 patients (2.8%) sustained MI and 315/16,061 patients (2.0%) died, within 30 days of surgery. Baseline characteristics and simple frequencies and proportions of the main outcomes, stratified by the exposures of interest, are presented in table 1. Cases included in multivariable analyses are shown in figure 1.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics.

Descriptive data stratified by binary thresholds for highest and lowest intraoperative heart rate (HR) and systolic blood pressure (SBP), presented as frequencies with percentages (%) or means with standard deviations (SD). Age rounded to nearest whole number. Heart rate in beats per minute (bpm) and systolic blood pressure in mmHg. Highest intraoperative heart rate >100 bpm (HR >100); lowest intraoperative heart rate <55 bpm (HR <55); Highest systolic blood pressure >160 mmHg (SBP >160); lowest systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg (SBP <100); estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Missing cases shown in figure 1.

| Intraoperative HR or SBP groups | Whole cohort | HR >100 | HR <55 | SBP >160 | SBP <100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases (n) | 16079 | 2936 | 4256 | 4754 | 9891 |

| Mean age (SD) | 65 (11.9) | 64 (12.3) | 65 (11.3) | 68 (11.6) | 64 (11.6) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male (%) | 7763 (48.3) | 1448 (49.3) | 2118 (49.8) | 2197 (46.2) | 4702 (47.5) |

| Female (%) | 8316 (51.7) | 1488 (50.7) | 2138 (50.2) | 2557 (53.8) | 5189 (52.5) |

| Comorbid disorder (%) | |||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 545 (3.4) | 142 (4.8) | 106 (2.5) | 171 (3.6) | 281 (2.8) |

| Diabetes | 3153 (19.6) | 626 (21.3) | 744 (17.5) | 1163 (24.5) | 1785 (18.0) |

| Hypertension | 8171 (50.8) | 1304 (44.4) | 2226 (52.3) | 2844 (59.8) | 4754 (48.1) |

| Congestive cardiac failure | 761 (4.7) | 121 (4.1) | 184 (4.3) | 256 (5.4) | 405 (4.1) |

| Coronary artery disease | 1947 (12.1) | 247 (8.4) | 608 (14.3) | 674 (14.2) | 1054 (10.7) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 858 (5.3) | 127 (4.3) | 238 (5.6) | 316 (6.6) | 421 (4.3) |

| Previous stroke or transient ischemic attack | 1167 (7.3) | 279 (9.5) | 317 (7.5) | 533 (11.2) | 643 (6.5) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 1337 (8.3) | 205 (7.0) | 269 (6.3) | 396 (8.3) | 797 (8.1) |

| Preoperative eGFR (%) | |||||

| <30 ml/min | 564 (3.5) | 131 (4.7) | 104 (2.6) | 195 (4.3) | 311 (3.4) |

| 30-45 ml/min | 831 (5.2) | 171 (6.1) | 224 (5.7) | 336 (7.4) | 459 (5.0) |

| 45-60 ml/min | 1579 (9.8) | 241 (8.6) | 457 (11.5) | 592 (13.0) | 904 (9.9) |

| >60 ml/min | 11938 (74.2) | 2254 (80.6) | 3179 (80.2) | 3416 (75.3) | 7483 (81.7) |

| Surgical procedure category (%) | |||||

| Elective | 13765 (85.6) | 2312 (78.7) | 3881 (91.2) | 4020 (84.6) | 8512 (86.1) |

| Urgent | 485 (3.0) | 162 (5.5) | 83 (2.0) | 170 (3.6) | 317 (3.2) |

| Emergency | 1828 (11.4) | 462 (15.7) | 292 (6.9) | 564 (11.9) | 1062 (10.7) |

| Major surgery (%) | 9600 (59.7) | 1774 (60.4) | 2477 (58.2) | 2956 (62.2) | 6075 (61.4) |

| Outcome measures (%) | |||||

| MINS | 1197 (7.4) | 257 (9.7) | 233 (5.8) | 436 (10.0) | 711 (7.7) |

| Myocardial Infarction | 454 (2.8) | 109 (3.7) | 88 (2.1) | 185 (2.8) | 276 (2.8) |

| Mortality | 315 (2.0) | 119 (4.1) | 49 (1.2) | 91 (1.9) | 222 (2.2) |

Intraoperative heart rate

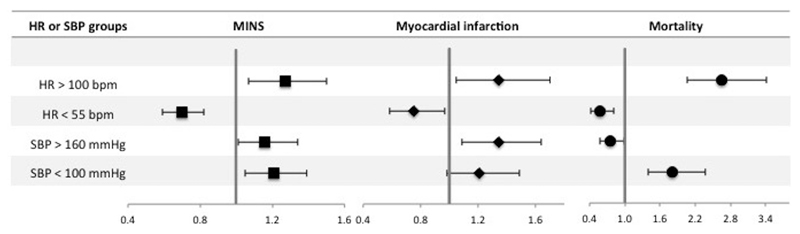

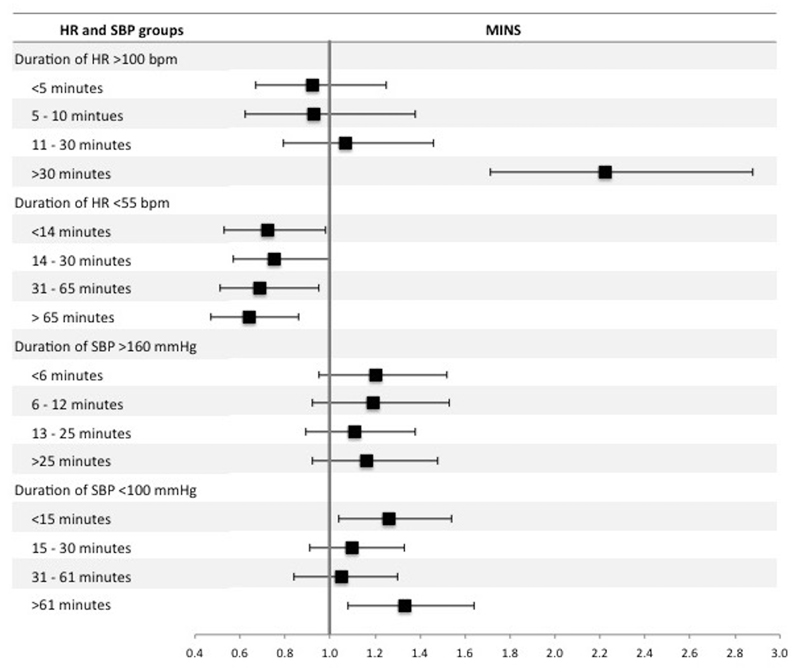

Highest intraoperative heart rate >100 bpm was associated with increased odds of MINS (OR 1.27 [1.07 – 1.50]; p <0.01), myocardial infarction (OR 1.34 [1.05 – 1.70]; p=0.02) and mortality (OR 2.65 [2.06 – 3.41]; p <0.01). Lowest intraoperative heart rate <55 bpm was associated with reduced odds of MINS (OR 0.70 [0.59 – 0.82]; p <0.01), myocardial infarction (OR 0.75 [0.58 - 0.97]; p=0.03) and mortality (OR 0.58 [0.41 – 0.81]; p <0.01) (table 2, figure 2 and supplementary tables 1 and 2). Duration of intraoperative heart rate >100 bpm for longer than 30 minutes was associated with MINS (OR 2.22 [1.71 – 2.88]; p <0.01) compared to participants with intraoperative hart rate ≤100 bpm throughout the procedure (figure 3 and supplementary table 3). Heart rate <55 bpm for any duration was associated with reduced odds of MINS and there was a trend towards reduced likelihood of MINS as duration of heart rate < 55bpm increased (figure 3 and supplementary table 4).

Table 2. Summary multivariable logistic regression models for highest and lowest intraoperative heart rate and systolic blood pressure.

Dependent variables are MINS, myocardial infarction and mortality within 30 days after surgery. Highest intraoperative heart rate was dichotomized according to a threshold of >100 beats per minute (bpm) with heart rate ≤100 bpm as the reference category. Lowest intraoperative heart rate was dichotomized according to the threshold of <55 bpm with heart rate ≥55 bpm as the reference category. Highest intraoperative systolic blood pressure was dichotomized according to a threshold of >160 mmHg with systolic blood pressure ≤160 mmHg as the reference category. Lowest intraoperative systolic blood pressure was dichotomized according to the threshold of <100 mmHg with systolic blood pressure ≥100 mmHg as the reference category. Results of adjusted analyses are presented with unadjusted analyses for comparison. Full multi-variable models are presented in supplementary tables 1-4.

| MINS | Myocardial Infarction | Mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | odds ratio | p-value | odds ratio | p-value | odds ratio | p-value |

| Highest intraoperative heart rate >100 bpm | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.31 (1.14-1.52) | <0.01 | 1.42 (1.15-1.78) | <0.01 | 2.79 (2.21-3.51) | <0.01 |

| Adjusted | 1.27 (1.07-1.50) | <0.01 | 1.34 (1.05-1.70) | 0.02 | 2.65 (2.06-3.41) | <0.01 |

| Lowest intraoperative heart rate <55 bpm | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.66 (0.57-0.76) | <0.01 | 0.66 (0.52-0.84) | <0.01 | 0.51 (0.37-0.69) | <0.01 |

| Adjusted | 0.70 (0.59-0.82) | <0.01 | 0.75 (0.58-0.97) | 0.03 | 0.58 (0.41-0.81) | <0.01 |

| Highest intraoperative systolic blood pressure >160 mmHg | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.48 (1.30-1.67) | <0.01 | 1.67 (1.38-2.03) | <0.01 | 0.96 (0.75-1.23) | 0.75 |

| Adjusted | 1.16 (1.01-1.34) | 0.04 | 1.34 (1.09-1.64) | 0.01 | 0.76 (0.58-0.99) | 0.04 |

| Lowest intraoperative systolic blood pressure <100mmHg | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.94 (0.83-1.06) | 0.28 | 0.97 (0.80-1.17) | 0.72 | 1.49 (1.16-1.91) | <0.01 |

| Adjusted | 1.21 (1.05-1.39) | 0.01 | 1.21 (0.98-1.49) | 0.07 | 1.81 (1.39-2.37) | <0.01 |

Figure 2.

Forest plot summarizing multivariable logistic regression models for highest and lowest intraoperative heart rate (HR) and systolic blood pressure (SBP). Dependent variables are MINS, myocardial infarction and mortality within 30 days after surgery. Highest intraoperative heart rate was dichotomized according to a threshold of >100 beats per minute (bpm) with heart rate ≤100 bpm as the reference category. Lowest intraoperative heart rate was dichotomized according to the threshold of <55 bpm with heart rate ≥55 bpm as the reference category. Highest intraoperative systolic blood pressure was dichotomized according to a threshold of >160 mmHg with systolic blood pressure ≤160 mmHg as the reference category. Lowest intraoperative systolic blood pressure was dichotomized according to the threshold of <100 mmHg with systolic blood pressure ≥100 mmHg as the reference category. The x-axis shows odds ratios and the error bars show 95% confidence intervals. Full multi-variable models are presented in supplementary tables 1-4.

Figure 3.

Forest plot summarizing multivariable logistic regression models for the duration of high/low intraoperative heart rate (HR) and systolic blood pressure (SBP). The dependent variable was MINS within 30 days after surgery. There were four separate regression models for duration of: intraoperative heart rate >100 beats per minute (bpm), intraoperative heart rate <55 bpm intraoperative systolic blood pressure >160 mmHg and intraoperative systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg. For each model, duration was stratified into four approximately equal quartiles. The reference categories were patients with ‘normal’ heart rate or systolic blood pressure, for example in the analysis of duration of heart rate > 100 bpm, the reference group was patients with heart rate ≤ 100 bpm. The x-axis shows odds ratios and the error bars show 95% confidence intervals. The full multivariable regression models are presented in supplementary tables 3,4,7 and 8.

Intraoperative systolic blood pressure

Highest intraoperative systolic blood pressure >160mmHg was associated with increased odds of MINS (OR 1.16 [1.01 – 1.34]; p=0.04) and myocardial infarction (OR 1.34 [1.09 – 1.64]; p=0.01) and reduced odds of mortality (OR 0.76 [0.58 – 0.99]; p=0.04). Lowest intraoperative systolic blood pressure <100mmHg was associated with increased odds of MINS (OR 1.21 [1.05 – 1.39]; p=0.01) and mortality (OR 1.81 [1.39 – 2.37]; p <0.01), but was not associated with myocardial infarction (OR 1.21 [0.98-1.49]; p=0.07) (table 2, figure 2 and supplementary tables 5 and 6). Duration of systolic blood pressure >160 mmHg was not associated with MINS (figure 3 and supplementary table 7). In comparison, duration of systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg for <15 minutes or >61 minutes was associated with MINS (OR 1.26 [1.04-1.54]; p=0.02 and OR 1.33 [1.08-1.64]; p<0.01 respectively) (figure 3 and supplementary table 8).

Intraoperative heart rate and systolic blood pressure

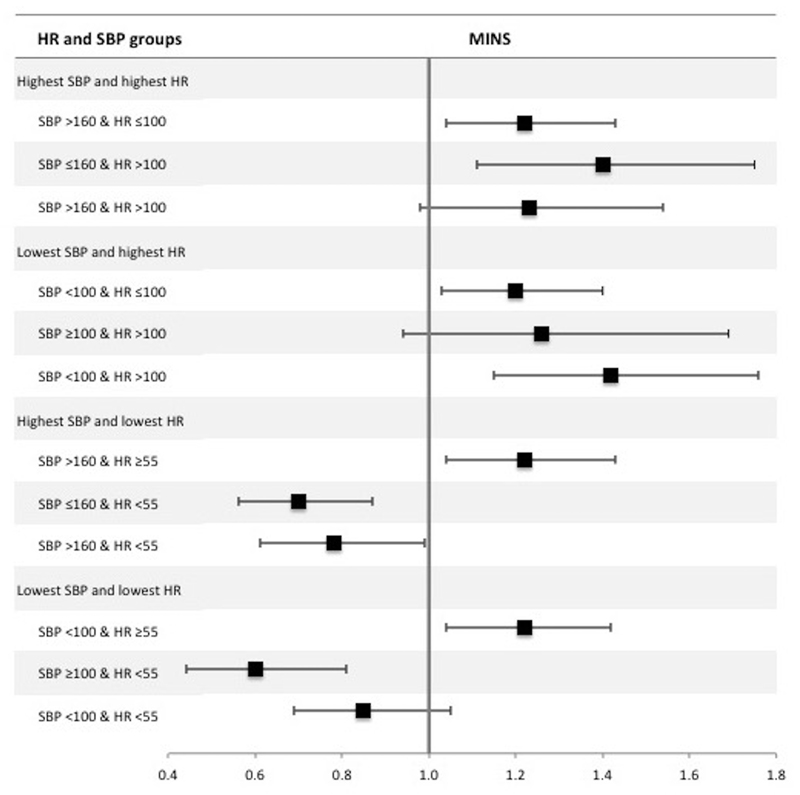

Combinations of highest/lowest heart rate (HR) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) were categorised as: highest HR and highest SBP / highest HR and lowest SBP/ highest SBP and lowest HR / lowest SBP and lowest HR. The association between heart rate (HR) and MINS was modified by systolic blood pressure (SBP); shown in figure 4 and supplementary tables 9-12. The incidence of MINS in patients with hypotension (SBP <100 mmHg) and tachycardia (HR >100bpm) was 176/1906 (9.2%) and had higher odds of MINS (OR 1.42 [1.15-1.76]; p<0.01), compared to patients with hypotension in the absence of tachycardia (499/6632 [7.5%]; OR 1.20 [1.03-1.40]; p=0.02) or patients with tachycardia in the absence of hypotension (76/736 [10.3%]; OR 1.26 [0.94-1.69]; p=0.13), where the reference group was patients without hypotension or tachycardia. Patients with hypertension (SBP >160 mmHg) without bradycardia (HR <55 bpm) were at increased risk of MINS (326/2802 [11.6%]; OR 1.22 (1.04-1.43); p=0.02). However, bradycardia was associated with less risk of MINS, regardless of highest systolic blood pressure (figure 4). A similar result was seen for hypotension with and without bradycardia (figure 4). On post-hoc testing there was little evidence of statistical interaction (effect modification) between heart rate and blood pressure, except between elevated systolic pressure and elevated heart rate, where the association between elevated systolic pressure and MINS was increased in the presence of heart rate >100 bpm.

Figure 4.

Forest plot summarizing multivariable logistic regression models for combinations of highest/lowest intraoperative systolic blood pressure (SBP) and heart rate (HR). The dependent variable was MINS within 30 days after surgery. The sample was categorized according to highest intraoperative systolic blood pressure (SBP) >160 mmHg, lowest intraoperative SBP <100 mmHg, highest intraoperative heart rate (HR) >100 beats per minute (bpm) and lowest intraoperative HR <55 bpm. For highest SBP and HR the reference group was SBP ≤160 & HR ≤100, for lowest SBP and highest HR the reference group was SBP ≥100 & HR ≤100, for highest SBP and lowest HR the reference group was SBP ≤160 & HR ≥55 and for lowest SBP and lowest HR the reference group was SBP ≥100 & HR ≥55. The x-axis shows odds ratios and the error bars show 95% confidence intervals. The results presented are summaries of adjusted analyses (as per the primary analysis). Full multi-variable models are presented in supplementary tables 9-12.

Sensitivity analyses

When we repeated the primary analyses excluding 1828 participants undergoing emergency surgery, our results were similar (supplementary tables 13-16). When we repeated the primary heart rate analysis excluding 2727 participants that received either a beta-blocker or rate-limiting calcium channel blocker within 24 hours before surgery, our results were very similar (supplementary tables 17 and 18). However, the association between the lowest intraoperative heart rate <55 bpm and reduced mortality was no longer statistically significant (OR 0.71 [0.49 – 1.03]; p=0.07). When we repeated the primary heart rate analysis excluding 545 participants with pre-existing atrial fibrillation, our results were very similar (supplementary tables 19 and 20). However, the association between highest intraoperative heart rate >100 bpm was only a trend (OR 1.29 [0.99 – 1.67]; p=0.06). It is possible that a patient could have episodes of both high heart rate and low heart rate during the surgical procedure. The same is true for systolic blood pressure. We undertook a post hoc analysis that categorised episodes of high/low heart rate/systolic blood pressure into two four-level categorical variables (heart rate: 55-100 bpm / <55 bpm/>100 bpm / <55 and >100 bpm; and systolic blood pressure: 100 – 160 mmHg / <100 mmHg / >160 mmHg / <100 and >160 mmHg) shown in supplementary table 21. The results were similar to the primary analysis (supplementary tables 22 and 23), except that the association between maximum systolic blood pressure >160 mmHg and MINS was no longer statistically significant (OR 1.22 [0.97-1.52]; p=0.08). The combination of minimum systolic pressure <100 mmHg and maximum systolic pressure >160 mmHg was associated with MINS (OR 1.42 [1.16-1.75]; p<0.01). However, the combination of minimum heart rate <55 bpm and maximum heart rate >100 bpm was not associated with MINS (OR 0.70 [0.44-1.13]; p=0.15). To account for possible increased type I error associated with multiple comparisons in the analysis of duration of high/low HR/SBP quartiles, we undertook Bonferroni corrections. The results remained similar in that the longest durations of SBP <100 mmHg (>61 minutes), HR >100 bpm (>30 minutes) and HR <55 bpm (>55 minutes) remained associated with MINS. However, the associations between intermediate durations and MINS were no longer statistically significant.

Discussion

The principal finding of this analysis is that intraoperative tachycardia and hypotension are independently associated with MINS and mortality. For the first time, we demonstrate the effect of combinations of intraoperative heart rate and systolic blood pressure. Our results suggest that the association between low systolic blood pressure and MINS is increased if elevated heart rate occurred during the procedure and reduced if low heart rate occurred during the procedure. Prolonged durations of heart rate > 100bpm and systolic blood pressure < 100mmHg were associated with increased risk of MINS. Furthermore, minimum intraoperative heart rate < 55bpm was associated with reduced risk of MINS and mortality.

Our results are consistent with studies that demonstrate association between intraoperative hypotension and postoperative adverse events following non-cardiac surgery.7, 8, 12, 15, 26, 27 However, unlike our study, these were small and few used objective biomarkers as outcome measures. This is the first study to identify relationships between high intraoperative heart rate/systolic blood pressure and increased risk of MINS, and low intraoperative heart rate and reduced risk of MINS. While the observational nature of our data do not allow us to infer causal relationships, it is reasonable to hypothesize that active avoidance of either very high heart rate, or very high/low systolic blood pressures during surgery may be clinically beneficial. Data from clinical trials suggest that treatment with beta-blockers (which lower heart rate) can reduce the risk of myocardial infarction after non-cardiac surgery, but at the expense of larger increases in the risk of mortality and stroke.12, 28 However, it is difficult to disentangle the effect of heart rate from the effect of beta-blockers and the degree of interaction between these variables. In our study, 2,727 (16.9%) patients received a beta-blocker or negatively chronotropic calcium channel blocker within 24 hours before surgery. We repeated the primary analysis after removing these cases and found that the association between maximum intraoperative heart rate and all the outcomes, and between minimum intraoperative heart rate and MINS/myocardial infarction were unchanged. However, the negative association between minimum intraoperative heart rate <55bpm and mortality was no longer statistically significant. In other words, the ‘protective’ association between low heart rate and reduced risk of mortality was lost in patients not receiving a beta-blocker or calcium channel antagonist. We previously made a similar observation for low preoperative heart rate, which suggests confounding by rate-controlling medication.11 However, we are unable to infer a causative relationship due to the observational nature of our data. This contrasts with the results of previous clinical trials where heart rate lowering medication was associated with increased mortality.12 Further research is needed to investigate potential mechanisms underlying this observation, in addition to trials targeting heart rate control while avoiding hypotension.29

Our data suggest that very high or very low intraoperative heart rate and blood pressure are key perioperative factors that, alone or in tandem, may contribute to MINS. The potential for preoperative identification or treatment of these patients needs further research.30, 31 The pathophysiological mechanism of MINS is unclear. It may be caused by extended periods of myocardial ischemia as a result of oxygen supply-demand imbalance in cardiac muscle; the proposed mechanism of type 2 myocardial infarction.9, 32 In the context of this model, intraoperative hypotension or tachycardia may reduce myocardial perfusion pressure leading to reduced myocardial oxygen supply. Similarly, elevated systolic pressure increases end-systolic stress, leading to increased myocardial oxygen demand.33 Our results support this theory; we observed increasing risk of MINS as the duration of tachycardia or hypotension increased. This is consistent with animal studies of tachycardia induced sub-endocardial myocardial necrosis, where the duration ischemia was correlated with degree of necrosis.34 In addition, we observed that patients with very high and very low blood pressure during surgery were at greater risk of MINS than either high or low blood pressure alone. While we adjusted our analysis for multiple perioperative factors, our findings may reflect unmeasured confounding and cannot exclude that tachycardia/hypertension/hypotension are merely markers of other conditions or treatment interventions that may promote MINS.35–39

A strength of this analysis is the large sample size derived from multiple centres in multiple countries, giving robust external validity and making our results generalisable to the vast majority of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. The primary outcome was an objective biomarker, rather than a potentially subjective, clinically defined outcome. The use of troponin is important because more than four out five patients with MINS are asymptomatic, while only one third have electrocardiographic or echocardiographic evidence of ischemia.19 The detailed nature of the VISION database allowed us to adjust our analysis for confounding factors using multivariable regression modelling, including pre-existing atrial fibrillation.

Our analyses also have some important limitations. We cannot exclude unmeasured confounding, for example; the use of intraoperative cardiac medication, the presence of cardiac pacemakers and the incidence of preoperative troponin elevation are all unknown, although we expect the frequency of these to be low.40, 41 Similarly, we did not routinely seek evidence of myocardial ischemia in patients with troponin elevation <0.04 ng/mL, which may underestimate the incidence of myocardial ischemia. Another potentially confounding factor is pre-existing atrial fibrillation, which we corrected for by inclusion in the multivariable models and through sensitivity analysis. We performed additional sensitivity analyses that excluded cases of emergency surgery, and patients receiving preoperative beta-blockers or rate limiting calcium channel antagonists within 24 hours before surgery. However, in the case of rate limiting medication, it is possible that the sensitivity analysis included patients that stopped taking these medications, with a variety of half-lives, > 24 hours before surgery. It is possible that the type of anesthesia (volatile, intravenous, balanced or regional techniques) could have confounded our results, however these data were not available for this secondary analysis, so we were unable to undertake a post-hoc sensitivity analysis on this basis. Continuous measurements of intraoperative heart rate and blood pressure were not recorded as part of this study; therefore our analysis was limited to summary data for intraoperative heart rate blood pressure, which included pre-defined thresholds. Similarly, it is unclear why systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg for between 15 and 60 minutes was not associated with MINS. Future computational research using continuously recorded heart rate or blood pressure data should be considered. We could only adjust the analysis for the absolute duration of intraoperative tachycardia/hypotension rather than expressing this as a proportion of length of surgery. We undertook a planned sensitivity analysis to examine association between combinations of abnormal intraoperative heart rate and systolic blood pressure and MINS, and a post-hoc analysis of combinations of very high and very low blood pressure/heart rate during surgery and MINS. However, since our data did not include the exact timing of high/low heart rate/systolic blood pressure, these combinations were not necessarily concurrent/simultaneous episodes. Our data suggest that future research to examine contemporaneous episodes of abnormal heart rate and systolic blood pressure is warranted, particularly the combination of tachycardia and hypotension.

Very high heart rate and very high or low systolic blood pressure during surgery are associated with increased risk of myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery. The duration of low intraoperative blood pressure and high heart rate are additional aetiological factors for MINS. Further targeted interventional studies using intraoperative heart rate and/or blood pressure thresholds that we have identified may help identify strategies to reduce perioperative cardiac complications.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

Question: Are intraoperative heart rate and/or systolic blood pressure associated with myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery (MINS)?

Findings: Very high heart rate and very high or low systolic blood pressure during surgery are associated with increased risk of MINS.

Meaning: Further targeted interventional studies using intraoperative heart rate and/or blood pressure thresholds that we have identified may help identify strategies to reduce perioperative cardiac complications.

Individual sources of funding

TEFA is supported by a Medical Research Council and British Journal of Anaesthesia clinical research training fellowship (MR/M017974/1). RP is supported by an NIHR research professorship and BJA/Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCoA) career development fellowship. GA is supported by a BJA and RCoA basic science fellowship and the British Oxygen Company research grant. RNR is supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa. PJD is supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Periopereative Medicine and the Yusuf Chair in Cardiology. The VISION study was funded by over 50 grants, listed below.

Sources of funding for the VISION study

Funding for this study comes from more than 50 grants for VISION and its sub-studies: Canadian Institutes of Health Research (6 grants), Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario (2 grants), Academic Health Science Centres Alternative Funding Plan Innovation Fund Grant, Population Health Research Institute Grant, Clarity Research Group Grant, McMaster University, Department of Surgery, Surgical Associates Research Grant, Hamilton Health Science New Investigator Fund Grant, Hamilton Health Sciences Grant, Ontario Ministry of Resource and Innovation Grant, Stryker Canada, McMaster University, Department of Anesthesiology (2 grants), Saint Joseph’s Healthcare— Department of Medicine (2 grants), Father Sean O’Sullivan Research Centre (2 grants), McMaster University—Department of Medicine (2 grants), Hamilton Health Sciences Summer Studentships (6 grants), McMaster University—Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics Grant, McMaster University—Division of Cardiology Grant, and Canadian Network and Centre for Trials International Grant; Winnipeg Health Sciences Foundation Operating Grant; Diagnostic Services of Manitoba Research Grant; University of Manitoba, Faculty of Dentistry Operational Fund; Projeto Hospitais de Excelencia a Serviço do SUS grant from the Brazilian Ministry of Health in Partnership with Hcor (Cardiac Hospital Sao Paulo-SP); School of Nursing, Universidad Industrial de Santander; Grupo de Cardiología Preventiva, Universidad Autó noma de Bucaramanga; Fundación Cardioinfantil Instituto de Cardiología; Alianza Diagnóstica SA; University of Malaya Research Grant; and University of Malaya, Penyelidikan Jangka Pendek Grant. Roche Diagnostics provided the troponin T assays and some financial support for the VISION Study. The VISION Study funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation or approval of the article.

Footnotes

Contributions

Name: T. Abbott, MRCP. This author helped design the analysis plan, perform the data analysis, draft the manuscript and approve the final version.

Name: R. Pearse, MD. This author helped design the analysis plan, provide advice on the data analysis, help draft the manuscript and approve the final version.

Name: R. Archbold, MD. This author helped design the analysis plan, critically review the manuscript and approve the final version.

Name: T. Ahmad, MD. This author helped analyse the data, critically review the manuscript and approve the final version.

Name: E. Niebrzegowska, MSc. This author helped critically review the manuscript and approve the final version.

Name: A. Wragg, FRCP. This author helped critically review the manuscript and approve the final version.

Name: R. Rodseth. This author helped design the analysis plan, critically review the manuscript and approve the final version.

Name: P.Devereaux, PhD. This author helped design the analysis plan, provide advice on the data analysis, critically review the manuscript and approve the final version. This author acts as a guarantor of the data and affirms the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the secondary analysis being reported.

Name: G. Ackland, PhD. This author helped design the analysis plan, provide advice on the data analysis, help draft the manuscript and approve the final version. This author acts as a guarantor of the data and affirms the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the secondary analysis being reported.

Conflict of interest statement

The VISION Study funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation or approval of the article. RP holds research grants, and has given lectures and/or performed consultancy work for Nestle Health Sciences, BBraun, Medtronic, Glaxo Smithkline and Edwards Lifesciences, and is a member of the Associate editorial board of the British Journal of Anaesthesia. GLA is a member of the Associate editorial board of Intensive Care Medicine Experimental. Roche Diagnostics provided the troponin T assays and some financial support for the VISION Study. PD has received other funding from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics for investigator initiated studies. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Vascular Events In Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation Study Investigators. Devereaux PJ, Chan MT, et al. Association between postoperative troponin levels and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307:2295–304. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillies MA, Shah AS, Mullenheim J, et al. Perioperative myocardial injury in patients receiving cardiac output-guided haemodynamic therapy: a substudy of the OPTIMISE Trial. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2015;115:227–33. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiser TG, Haynes AB, Molina G, et al. Estimate of the global volume of surgery in 2012: an assessment supporting improved health outcomes. Lancet. 2015;385(Suppl 2):S11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60806-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearse RM, Moreno RP, Bauer P, et al. Mortality after surgery in Europe: a 7 day cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:1059–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61148-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbott TEF, Fowler AJ, Dobbs T, et al. Frequency of surgical treatment and related hospital procedures in the United Kingdom: A national ecological study using hospital episode statistics. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2017;119:249–257. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathoe HM, van Klei WA, Beattie WS. Perioperative troponin elevation: always myocardial injury, but not always myocardial infarction. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2014;119:1014–6. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bijker JB, van Klei WA, Kappen TH, van Wolfswinkel L, Moons KG, Kalkman CJ. Incidence of intraoperative hypotension as a function of the chosen definition: literature definitions applied to a retrospective cohort using automated data collection. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:213–20. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000270724.40897.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sessler DI, Sigl JC, Kelley SD, et al. Hospital stay and mortality are increased in patients having a “triple low” of low blood pressure, low bispectral index, and low minimum alveolar concentration of volatile anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:1195–203. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31825683dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landesberg G, Beattie WS, Mosseri M, Jaffe AS, Alpert JS. Perioperative myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2009;119:2936–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.828228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devereaux PJ, Sessler DI, Leslie K, et al. Clonidine in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370:1504–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbott TE, Ackland GL, Archbold RA, et al. Preoperative heart rate and myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery: results of a predefined secondary analysis of the VISION study. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2016;117:172–81. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.POISE Study Group. Devereaux PJ, Yang H, et al. Effects of extended-release metoprolol succinate in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery (POISE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1839–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wijeysundera DN, Duncan D, Nkonde-Price C, et al. Perioperative Beta Blockade in Noncardiac Surgery: A Systematic Review for the 2014 ACC/AHA Guideline on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Management of Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130:2246–64. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foex P, Higham H. Preoperative fast heart rate: a harbinger of perioperative adverse cardiac events. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2016;117:271–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reich DL, Bennett-Guerrero E, Bodian CA, Hossain S, Winfree W, Krol M. Intraoperative tachycardia and hypertension are independently associated with adverse outcome in noncardiac surgery of long duration. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2002;95:273–7. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Waes JA, van Klei WA, Wijeysundera DN, van Wolfswinkel L, Lindsay TF, Beattie WS. Association between Intraoperative Hypotension and Myocardial Injury after Vascular Surgery. Anesthesiology. 2016;124:35–44. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsh M, Devereaux PJ, Garg AX, et al. Relationship between intraoperative mean arterial pressure and clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery: toward an empirical definition of hypotension. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:507–15. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182a10e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abbott TEF, Pearse RM, Archbold RA, et al. Association between preoperative pulse pressure and perioperative myocardial injury: an international observational cohort study of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2017;119:78–86. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Botto F, Alonso-Coello P, Chan MT, et al. Myocardial Injury after Noncardiac Surgery: A Large, International, Prospective Cohort Study Establishing Diagnostic Criteria, Characteristics, Predictors, and 30-day Outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:564–78. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. International Journal of Surgery. 2014;12:1500–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jammer I, Wickboldt N, Sander M, et al. Standards for definitions and use of outcome measures for clinical effectiveness research in perioperative medicine: European Perioperative Clinical Outcome (EPCO) definitions: a statement from the ESA-ESICM joint taskforce on perioperative outcome measures. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2015;32:88–105. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;126:2020–35. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31826e1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawn MT, Graham LA, Richman JS, Itani KM, Henderson WG, Maddox TM. Risk of major adverse cardiac events following noncardiac surgery in patients with coronary stents. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310:1462–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999;100:1043–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Connor ME, Kirwan CJ, Pearse RM, Prowle JR. Incidence and associations of acute kidney injury after major abdominal surgery. Intensive Care Medicine. 2016;42:521–30. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4157-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bijker JB, van Klei WA, Vergouwe Y, et al. Intraoperative hypotension and 1-year mortality after noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:1217–26. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c14930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hartmann B, Junger A, Rohrig R, et al. Intra-operative tachycardia and peri-operative outcome. Langenbeck’s archives of surgery / Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie. 2003;388:255–60. doi: 10.1007/s00423-003-0398-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouri S, Shun-Shin MJ, Cole GD, Mayet J, Francis DP. Meta-analysis of secure randomised controlled trials of beta-blockade to prevent perioperative death in non-cardiac surgery. Heart. 2013 doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbott TEF, Minto G, Lee AM, Pearse RM, Ackland G. Elevated preoperative heart rate is associated with cardiopulmonary and autonomic impairment in high-risk surgical patients. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2017;119:87–94. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearse RM, Harrison DA, MacDonald N, et al. Effect of a perioperative, cardiac output-guided hemodynamic therapy algorithm on outcomes following major gastrointestinal surgery: a randomized clinical trial and systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;311:2181–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearse RM, Holt PJ, Grocott MP. Managing perioperative risk in patients undergoing elective non-cardiac surgery. BMJ. 2011;343:d5759. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson JL, Morrow DA. Acute Myocardial Infarction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376:2053–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1606915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Assmann G, Cullen P, Evers T, Petzinna D, Schulte H. Importance of arterial pulse pressure as a predictor of coronary heart disease risk in PROCAM. European Heart Journal. 2005;26:2120–6. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landesburg G, Zhou W, Aversano T. Tachycardia-induced subendocardial necrosis in acutely instrumented dogs with fixed coronary stenosis. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 1999;88:973–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199905000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fowler AJ, Ahmad T, Phull MK, Allard S, Gillies MA, Pearse RM. Meta-analysis of the association between preoperative anaemia and mortality after surgery. The British Journal of Surgery. 2015;102:1314–24. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manfrini O, Pizzi C, Trere D, Fontana F, Bugiardini R. Parasympathetic failure and risk of subsequent coronary events in unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. European Heart Journal. 2003;24:1560–6. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whelton SP, Narla V, Blaha MJ, et al. Association between resting heart rate and inflammatory biomarkers (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and fibrinogen) (from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) The American Journal of Cardiology. 2014;113:644–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whittle J, Nelson A, Otto JM, et al. Sympathetic autonomic dysfunction and impaired cardiovascular performance in higher risk surgical patients: implications for perioperative sympatholysis. Open Heart. 2015;2:e000268. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2015-000268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abbott TE, Vaid N, Ip D, et al. A single-centre observational cohort study of admission National Early Warning Score (NEWS) Resuscitation. 2015;92:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dierckx R, Cleland JG, Parsons S, et al. Prescribing patterns to optimize heart rate: analysis of 1,000 consecutive outpatient appointments to a single heart failure clinic over a 6-month period. JACC Heart Failure. 2015;3:224–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagele P, Brown F, Gage BF, et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T in prediction and diagnosis of myocardial infarction and long-term mortality after noncardiac surgery. American Heart Journal. 2013;166:325–32 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.