Abstract

Background

Clinical guidelines recommend immediate initiation of combined antiretroviral therapy (ART) for all HIV-positive individuals. However, those guidelines are based on trials of relatively young participants.

Methods

We included HIV-positive ART-naïve, AIDS-free individuals aged 50-70 years after 2004 in the HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration. We used the parametric g-formula to estimate the 5-year risk of all-cause and non-AIDS mortality under: i) immediate initiation at baseline, and initiation at CD4 count ii) <500 cells/mm3, and iii) <350 cells/mm3. Results were presented separately for the general HIV population and for a US Veterans cohort with high mortality.

Results

The study included 9596 individuals (28% US Veterans) with median [interquantile range] age of 55 [52,60] years and CD4 count 336 [182,513] at baseline. The 5-year risk of all-cause mortality was 0.40% (95% CI 0.10,0.71) lower for the general HIV population and 1.61% (95% CI 0.79,2.67) lower for US Veterans when comparing immediate initiation vs initiation at CD4<350 cells/mm3. The 5-year risk of non-AIDS mortality was 0.17% (95% CI -0.07,0.43) lower for the general HIV population and 1% (95% CI 0.31,2.00) lower for US Veterans when comparing immediate initiation vs initiation at CD4<350 cells/mm3.

Conclusions

Immediate initiation appears to reduce all-cause and non-AIDS mortality in patients aged 50-70 years.

Keywords: Aging, when to start, antiretroviral treatment, CD4 cell count, causal inference, parametric g-formula, comparative effectiveness

Introduction

Two randomized clinical trials have shown that combined antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation at high CD4 counts reduces the risk of serious AIDS and non-AIDS events and death in HIV-positive individuals 1,2. As a result, clinical guidelines have been updated to recommend ART initiation in all HIV-positive individuals regardless of their CD4 cell count3–5. However, these trials were comprised of relatively young participants (median age 36 years) and the number of deaths was too small to examine effects on mortality. Thus, estimates of the impact of the new recommendations on mortality among older HIV-positive individuals, whose prognosis may be different, are currently lacking.

The number of patients diagnosed with HIV at older ages has increased over time 6. Currently, between 12 and 18% of newly diagnosed HIV-positive individuals are over 50 years of age in high-income countries 7,8. Compared with younger HIV-positive patients, those who enter HIV care at older ages are often diagnosed with late or advanced HIV disease 6, have a diminished immunological response to treatment 9–11, and are therefore at higher risk of progressing to AIDS or death. The clinical management of these patients is further complicated by a higher prevalence of comorbidities, including hyperlipidaemia, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes12. The benefits of immediate ART initiation might be partially or totally offset by polypharmacy, i.e. taking a large number of different medicines 13, that can make adherence to ART more difficult and can increase the risk of drug toxicities and drug interactions 14.

It is therefore important to quantify the impact of immediate ART initiation in patients who enter into HIV care at older ages. Here we estimate the 5-year risk of all-cause mortality and non-AIDS mortality among ART-naïve, AIDS-free individuals aged between 50 and 70 years using data from the HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration of HIV cohorts from Europe and the Americas. More specifically, we estimated and compared the mortality risks if all participants had started ART (i) immediately, (ii) when their CD4 count dropped below 500 cells/mm3, and (iii) when their CD4 count dropped below 350 cells/mm3. We present the results separately for HIV-positive patients from the general population and for United States (US) Veterans with high mortality.

Methods

Selection of patients

We included individuals aged between 50 and 70 years, who had at least one CD4 cell count and one HIV-RNA measured within 3 months of each other while ART-naïve and AIDS-free after December 31, 2004. Baseline was defined as the earliest of the date when all the inclusion criteria were met. Individuals aged more than 70 years at baseline were rare in our cohorts and were not included because their clinical management might be different due to a higher burden of comorbidities. We considered two populations with different background mortality: HIV-positive patients from the general population and US Veterans known to have higher mortality15. Individuals from the general HIV population were enrolled in the following cohorts: AMACS (Greece), ANRS CO3 Aquitaine, French Hospital Database, PRIMO, SEROCO (France), ATHENA (The Netherlands), CoRIS, GEMES, PISCIS (Spain), IPEC (Brazil), Southern Alberta Clinic Cohort (Canada), Swiss HIV Cohort study (Switzerland), UK CHIC and the UK Register of Seroconverters (United Kingdom). The population of US Veterans included individuals from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study (US).

ART initiation strategies

ART was defined as a combination of antiretroviral drugs including at least two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors plus either one or more protease inhibitors, one nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, one entry/fusion inhibitor, or one integrase inhibitor.

For each population, we estimated the 5-year risk of all-cause mortality and non-AIDS mortality if all participants had started ART within 3 months of baseline (immediate ART initiation). We compared these estimates with those estimated under ART initiation within 3 months of an AIDS diagnosis or CD4 count i) <500 and ii) <350 cells/mm3, the ART initiation strategies recommended in different settings before the changes in guidelines. We did not account for episodes of ART discontinuation and we assumed that once ART was started patterns of treatment discontinuation were the same as in the observed data for each of the two populations.

Follow-up

Follow-up started at baseline and ended at the earliest of death, 12 months after the most recent laboratory measurement, cohort-specific administrative censoring, date of pregnancy when known, 5 years after baseline or the date a patient initiated antiretroviral therapy with a combination other than our definition of ART.

Outcomes

The outcomes, which were analysed separately, were all-cause mortality and non-AIDS mortality up to 5 years after baseline. For each ART initiation strategy and outcome, we estimated the 5-year risk and risk difference. Non-AIDS mortality was defined as any known cause of death other than AIDS-defining conditions 16. Cause of death was based on the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) and formatted according to CODE (http://www.hicdep.org/). Two cohorts, UK CHIC and IPEC, did not provide data on cause of death and were excluded from the non-AIDS mortality analyses. For all cohorts death ascertainment and cause of death were based on hospital records and cross-matching with national and local registries15.

Statistical methods

Our estimates had to be adjusted for the time-dependent confounders CD4 cell count, HIV-RNA level and AIDS, as well as for confounders measured at baseline. Because standard statistical methods cannot appropriately adjust for time-dependent confounders affected by prior treatment 17,18, we applied the parametric g-formula to obtain adjusted estimates for each treatment strategy under the assumptions of no residual confounding, no measurement error, and no model misspecification 19.

The parametric g-formula is a generalization of standardization for time-varying treatments and confounders 17,20. The parametric g-formula is used to estimate the risk of mortality that would have been observed if all patients in the study had perfectly complied with a particular treatment initiation strategy and none had been lost to follow-up. The estimation procedure for the HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration has been described elsewhere 21. Briefly, the procedure has two steps. First, parametric regression models are used to estimate the joint distribution of the outcome, treatment and time-varying covariates conditional on previous treatment and covariate history. Second, a Monte Carlo simulation using the above estimates is run to simulate the distribution of the post-baseline outcomes and time-varying covariates separately under each ART initiation strategy.

For the first step, we fit separate logistic regression models for time-varying indicators for the outcome event, AIDS, ART initiation, measurement of CD4 cell count, measurement of HIV-RNA, and linear regression models for CD4 cell count and HIV-RNA on the natural logarithm scale. All regression models included as covariates the most recent value of these time-varying variables, time since last CD4 count and HIV-RNA measurements, and the following baseline variables: CD4 cell count (<100, 100-199, 200-349, 350-499, ≥500 cells/mm3), HIV-RNA level (<10000,10000-100000, >100000 copies/mL), age (<60,≥60 years), sex, mode of acquisition (heterosexual, homo/bisexual, injecting drug users, or other/unknown), calendar year (2005-2009, 2010-2015), geographical origin (Western countries, sub-Saharan Africa, other, unknown), and cohort. All models also included an interaction term for number of months since ART initiation.

In the analyses where the outcome was non-AIDS mortality, AIDS mortality and mortality due to unknown cause where treated as competing events. The g-formula estimates of risk in the presence of competing risks should be interpreted as an extension of the sub-distribution cumulative incidence function to the setting of time-varying treatments and confounders20.

As in all regression-based methods, the parametric g-formula relies on correct model specification. To explore the validity of our parametric assumptions, we compared the observed means of the outcome and time-varying covariates with those predicted by our models. We used a nonparametric bootstrap procedure based on 500 samples to obtain percentile-based 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All analyses were conducted with the publicly available SAS macro GFORMULA (http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/causal/software/).

Sensitivity analyses

Since our main analyses included all ART-naive patients regardless of CD4 count at baseline in a sensitivity analysis we restricted to the subset of individuals in the general HIV population with a CD4 count≥500 cells/mm3 at baseline. This sensitivity analysis was conducted only in the general HIV population since there were not enough patients and death cases to achieve good model fit in the US Veterans.

Since a non-negligible proportion of death events had unknown cause of death, as a sensitivity analysis we estimated the risks, risk difference and risk ratio of non-AIDS mortality assuming that all deaths due to unknown cause were non-AIDS related. This extreme case scenario is unrealistic in practice, but provides an illustration of how sensitive the analyses may be to assumptions regarding the missing data on cause-specific mortality.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 9,599 eligible individuals, of whom 2672 (28%) were US Veterans. Patients were predominantly males and started follow-up before 2010. The median [interquartile range (IQR)] age at baseline was 55 years [52,59] in the general HIV population and 56 years [53,60] in US Veterans. The median [IQR] CD4 count at baseline was 354 cells/mm3 [203,530] in the general HIV population and 284 cells/mm3 [128,471] in US Veterans (Appendix Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by background mortality group, HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration 2005-2015.

| Baseline characteristics | General HIV population | U.S. Veterans | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included (%) | Initiators of ART during follow-up | Median [IQR] follow-up, months | Included (%) | Initiators of ART during follow-up | Median [IQR] follow-up, months | ||

| CD4 count, cells/mm3 | <100 | 798 (12%) | 88% | 30 [13,54]] | 532 (20%) | 87% | 26 [12,53] |

| 100 – 200 | 878 (13%) | 89% | 33 [15,57] | 435 (16%) | 87% | 27 [14,54] | |

| 200 – 349 | 1725 (25%) | 85% | 35 [17,64] | 626 (23%) | 83% | 29 [14,55] | |

| 350 – 499 | 1534 (22%) | 71% | 34 [15,62] | 495 (19%) | 76% | 29 [13,60] | |

| ≥500 | 1992 (29%) | 57% | 34 [15,62] | 584 (22%) | 60% | 29 [14,57] | |

| HIV-RNA, copies/mL | <10,000 | 1612 (23%) | 58% | 35 [15,66] | 686 (26%) | 63% | 38 [11,53] |

| 10,000 - 100,000 | 2855 (41%) | 75% | 33 [15,62] | 1266 (47%) | 81% | 30 [15,58] | |

| >100,000 | 2460 (36%) | 85% | 33 [16,59] | 720 (27%) | 87% | 27 [12,52] | |

| Sex | Male | 5493 (79%) | 76% | 34 [16,63] | 2607 (98%) | 78% | 28 [13,56] |

| Female | 1434 (21%) | 70% | 31 [14,58] | 65 (2%) | 74% | 30 [15,50] | |

| Mode of acquisition | Heterosexual | 3149 (45%) | 73% | 32 [15,59] | |||

| Homo/bisexual | 2960 (43%) | 77% | 39 [18,69] | ||||

| Injection drug use | 161 (2%) | 67% | 21 [11,45] | ||||

| Other/unknown | 657 (9%) | 70% | 26 [11,50] | 2672 (100%) | 78% | 28 [13,56] | |

| Geographical origin | Western Countries | 4386 (63%) | 76% | 36 [16,66] | |||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 415 (6%) | 69% | 26 [11,51] | ||||

| Rest of World | 611 (9%) | 72% | 28 [14,51] | ||||

| Unknown country | 1515 (22%) | 73% | 31 [14,60] | 2672 (100%) | 74% | 28 [13,56] | |

| Calendar year | 2005-2009 | 4212 (61%) | 77% | 52 [26,79] | 1791 (67%) | 86% | 45 [23,67] |

| 2010 – 2015 | 2715 (39%) | 71% | 19 [11,33] | 88 (33%) | 80% | 15 [9,22] | |

| Age at enrollment, years | 50-59 | 5384 (78%) | 74% | 34 [15,63] | 1964 (73%) | 83% | 29 [13,58] |

| 60-70 | 1543 (22%) | 78% | 34 [15,59] | 708 (27%) | 87% | 25 [13,48] | |

| HCV co-infection status | No | 5201 (75%) | 80% | 35 [17,63] | 1555 (58%) | 81% | 29 [14,56] |

| Yes | 891 (13%) | 74% | 36 [17,72] | 1069 (40%) | 75% | 28 [13,56] | |

| Unknown | 835 (12%) | 59% | 22 [11,46] | 48 (2%) | 56% | 11 [8,18] | |

| All patients | 6927 | 74% | 34 [15,62] | 2672 | 78% | 28 [13,56] | |

During a follow-up of 31,989 person years, 7,247 individuals initiated ART, 295 individuals died in the general HIV population and 339 died in the US Veterans cohort. In the general population, there were 124 (55%) non-AIDS deaths, 47 (21%) AIDS deaths, and 54 (24%) deaths with unknown cause. The most common non-AIDS causes of death were non-AIDS cancer (70 events) and cardiovascular disease (21 events). In US Veterans, there were 136 (40%) non-AIDS deaths, 157 (47%) AIDS deaths and 46 (14%) deaths with unknown cause. Sixty-two non-AIDS deaths were attributed to non-AIDS cancer and 45 to cardiovascular disease.

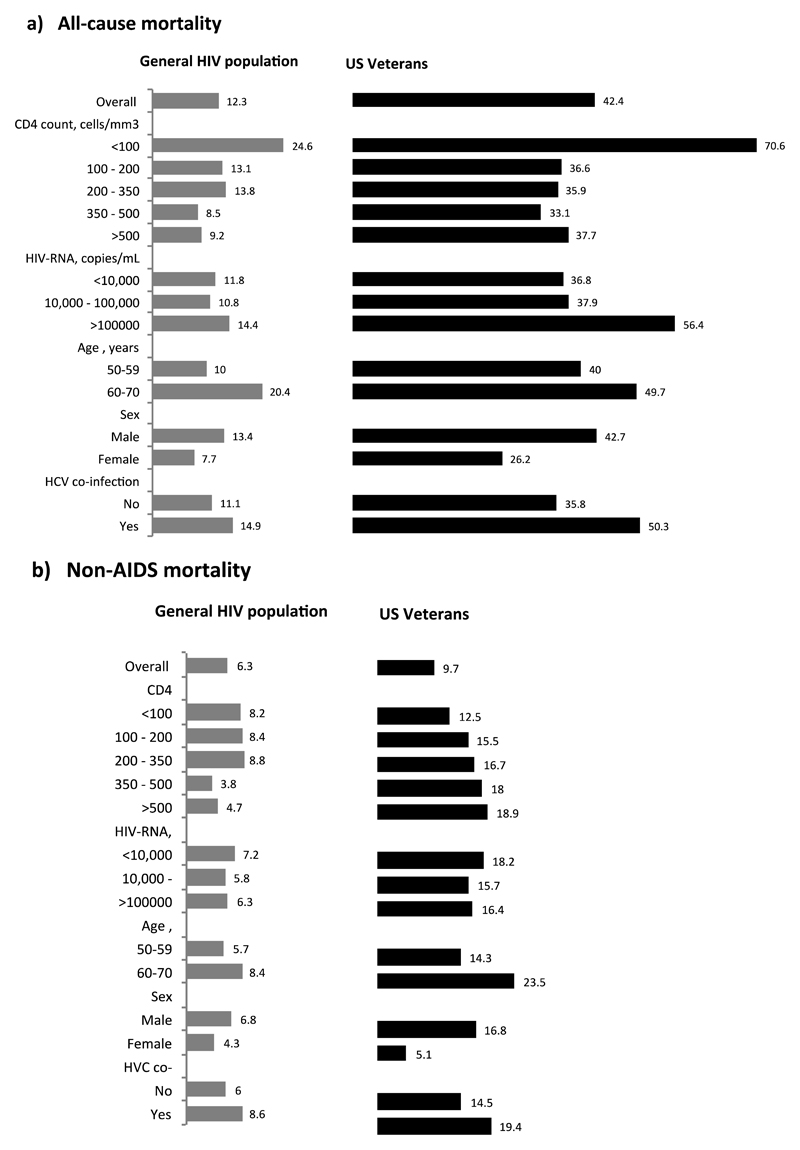

Rates of all-cause mortality and non-AIDS mortality per 1000 person-years were 12.3 and 6.3 for the general HIV population, and 42.4 and 9.7 for US Veterans (Figure 1). In both populations, the observed rates of all-cause and non-AIDS mortality were higher for males and for individuals with lower CD4 count and older age at baseline.

Figure 1.

Rates (number of events per 1000 person-years) of (a) all-cause mortality and (b) non-AIDS mortality by baseline characteristics and by background mortality group, HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration 2005-2015.

The estimated 5-year risk of all-cause mortality under immediate ART initiation was 5.3% (95% CI 4.5, 6.2) in the general HIV population and 14.4% (12.6, 16.7) in the US Veterans (Table 2). The 5-year risk of all-cause mortality was 0.40% (0.10, 0.71) lower for the general HIV population and 1.61% (0.79, 2.67) lower for US Veterans when comparing immediate initiation vs initiation at CD4 below 350 cells/mm3. The estimated risk of non-AIDS mortality was lower for immediate ART initiation compared with initiation at CD4<500 and <350 cells/mm3 in both populations (Table 2). More specifically, the 5-year risk of non-AIDS mortality was 0.17% (-0.07,0.43) lower for the general HIV population and 1.0% (0.31,2.0) lower for US Veterans when comparing immediate initiation vs. initiation at a CD4 of 350 cells/mm3. The effect estimates were similar in a sensitivity analysis that classified all unknown-cause deaths as non-AIDS related (Appendix Table 2). Among individuals in the general HIV population with baseline CD4 count ≥500 cells/mm3, the estimated risks of all-cause mortality were 2.8% (1.5,4.5) under immediate ART initiation, 3.7% (2.5,4.5) under initiation at CD4<500 cells/mm3, and 4.4% (3.1,5.9) under initiation at CD4<350 cells/mm3 (Table 3).

Table 2.

Estimated 5-year risks of all-cause mortality under three ART initiation strategies, HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration 2005-2015.

| All-cause mortality | Non-AIDS mortality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | ART initiation strategy | 5-year risk, % (95% CI) |

Risk difference (95% CI) |

Risk ratio (95% CI) |

5-year Risk, % (95% CI) |

Risk difference (95% CI) |

Risk ratio (95% CI) |

| General HIV population (N=6927) | Immediate universal | 5.3% (4.5,6.2) | 0 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 2.7% (2.1,3.4) | 0 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) |

| <500 cells/mm3 | 5.5% (4.8,6.3) | 0.14 (0.04,0.28) | 1.03 (1.01,1.06) | 2.8% (2.2,3.5) | 0.07 (-0.03,0.16) | 1.03 (0.99,1.06) | |

| <350 cells/mm3 | 5.7% (5.1,6.6) | 0.40 (0.10,0.71) | 1.07 (1.02,1.15) | 2.9% (2.3,3.7) | 0.17 (-0.07,0.43) | 1.06 (0.97,1.16) | |

| US Veterans (N=2669) | Immediate universal | 14.4% (12.6,16.7) | 0 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 6.6% (5.2,8.9) | 0 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) |

| <500 cells/mm3 | 15.1% (13.3,17.4) | 0.69 (0.32,1.13) | 1.05 (1.02,1.08) | 7.0% (5.6,9.2) | 0.40 (0.13,0.84) | 1.06 (1.02,1.13) | |

| <350 cells/mm3 | 16.0% (14.5,18.4) | 1.61 (0.79,2.67) | 1.11 (1.05,1.18) | 7.6% (6.4,9.9) | 1.00 (0.31,2.00) | 1.15 (1.04,1.30) | |

Table 3.

Estimated 5-year risks of all-cause mortality under three ART initiation strategies for individuals with CD4 cell count ≥ 500 cells/mm3 at baseline in the general HIV population, HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration 2005-2015.

| All-cause mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | ART initiation strategy | 5-year risk, % (95% CI) |

Risk difference (95% CI) |

Risk ratio (95% CI) |

| General HIV population (N=2072) | Immediate universal | 2.8% (1.6,4.4) | 0 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) |

| <500 cells/mm3 | 3.7% (2.5,5.0) | 0.86 (0.10,1.45) | 1.30 (1.03,1.72) | |

| <350 cells/mm3 | 4.4% (3.3,5.9) | 1.62 (0.17,2.82) | 1.56 (1.05,2.41) | |

The time-varying means predicted by our models under observed ART initiation were similar to the observed means in the original data (Appendix Figure 1-3).

Discussion

We estimated the effect of immediate ART initiation in HIV-positive patients between the ages of 50 and 70 years who were entering routine HIV clinical care. The 5-year risk of all-cause mortality was 0.40% lower for the general HIV population and 1.61% lower for US Veterans when comparing immediate initiation vs. initiation at a CD4 count of 350 cells/mm3. This means that in a hypothetical cohort of 1000 patients, immediate initiation would prevent between 4 and 16 deaths over a 5-year period. The reduction in absolute risk was smaller for non-AIDS mortality. While small, the estimated benefits of immediate initiation on the all-cause mortality of these older populations are larger than those estimated among all individuals in the HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration (median age 37 years) 22: the 7-year risk of all-cause mortality for immediate initiation was only 0.25% (95% CI 0.40,0.37) lower than the risk under initiation at CD4 count<350 cells/mm3. These findings suggest that in older HIV-positive patients the benefits of immediate ART initiation on mortality are not offset by age-related comorbidities and potential effects of polypharmacy.

Our findings expand results from randomized controlled trials such as Temprano and START, in which older HIV-positive patients were underrepresented and death events were too few to examine the effect of immediate initiation on mortality 1,2. Our results are also compatible with those of a subgroup analysis in patients with age ≥50 in START, which showed an increase of 2.24 events of serious diseases per 100 years for deferred versus immediate ART initiation 23.

Our analysis estimates the risk that would have been observed if all patients in the study, regardless of their CD4 cell count at baseline, had followed each ART initiation strategy. The small magnitude of the benefit of immediate initiation is not surprising as more than half of the included patients had a CD4 cell count <350 cells/mm3 at baseline. In analyses including only individuals in the general HIV population with CD4 cell count ≥500 cells/mm3 at baseline, the risk differences were larger: 1.62% for immediate initiation versus initiation with CD4<350 cells/mm3. This finding suggests that the benefit of immediate ART initiation in older HIV patients is greater when HIV infection is diagnosed early, which stresses the importance of scaling up testing programs. The high proportion of patients with low CD4 cell count at baseline observed in our data is consistent with reports of late HIV diagnosis among older HIV patients in observational studies and surveillance data7,24–27. Lower CD4 cell count at entry into care in older patients can be due to long periods of time being unaware of their positive HIV status as well as faster progression of the HIV disease in patients who become infected at older ages 28–30.

The rates of all-cause and non-AIDS mortality were higher for the US Veterans than for the general HIV population which included individuals in Europe, Canada and Brazil. The difference in mortality is likely due to a combination of heterogeneity in the data collection protocols and individual characteristics. A contributing factor is the ascertainment of death cases, which has been shown to be more complete in the cohort of US Veterans 15. In addition to this, in our study, the US Veterans had larger proportions of individuals older than 60 years at study entry and of HCV co-infected persons. Also, the US Veterans present substantial morbidity and poor health compared with the general population 31. However, despite the difference in mortality, our effect estimates were similar in both populations.

Our conclusions indicating the benefits of immediate initiation are compatible with the results from a study using routinely collected data in the United States 32 and extend this study by looking at more recent calendar period, an older age group and non-AIDS mortality. Of note, the observed and estimated 5-year risks under all ART initiation strategies in the general HIV population were lower in our study. The better prognosis demonstrated by our study may be due to the more recent follow-up period (2005-2015 in our study and 1998-2010 in the American study) and a smaller proportions of injecting drug users (2% in our study and 22% in the American study).

Our study has several limitations. First, as in all non-randomized studies, the validity of our estimates relies on the assumption of no unmeasured confounding. We adjusted for the most important factors used to decide when to initiate ART such as CD4 count, HIV-RNA and AIDS. However, we did not collect information on age-related comorbidities and concomitant treatments. Had these characteristics influenced the decision to initiate ART in older HIV positive patients then our estimates could be biased. Second, our methods require that all models are correctly specified. This condition cannot be guaranteed, but it seems plausible because our models resulted in simulated data sets with average outcome and time-varying covariates similar to those in the original data. Third, cause-specific mortality was unknown for a substantial proportion of patients. Therefore, our estimates might underestimate the risk of non-AIDS mortality. As expected, the estimated absolute risks of non-AIDS mortality were higher in the sensitivity analysis assuming that all deaths for unknown cause were non-AIDS deaths, although risk differences and risk ratios were similar. Moreover, it has been shown that the ICD10 classification for cause of death in individuals known to be HIV-positive tends to misclassify liver disease-related mortality into AIDS-related mortality 33. Finally, the cohorts included in the HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration are not based on random samples of the HIV population, tend to include many HIV seroconverters and might therefore not be fully representative of HIV patients in care in high-income countries. However, this concern is not supported by a recent study showing that individuals enrolled in European cohorts tend to have broadly similar characteristics at HIV diagnosis and the HIV-positive individuals in European Surveillance registries. 34.

In conclusion, immediate initiation of ART appears to be beneficial in reducing all-cause mortality in AIDS-free patients aged 50 years or older, despite their low baseline CD4 count. More effort should be made into diagnosing HIV earlier, particularly in older patients in order to ensure timely initiation of treatment and follow-up for concomitant comorbidities, thereby maximising the benefit of early treatment for HIV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding and support. The HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration is funded by NIH grant R01 AI102634. UK CHIC is funded by the UK Medical Research Council (Grant numbers G0000199, G0600337, G0900274 and M004236). The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the researchers and not necessarily those of the Medical Research Council.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

Acquisition of data: Dominique Costagliola, Caroline Sabin, Julia del Amo, Sophie Abgrall, Peter Reiss, Ard van Sighem, Sophie Jose, Jose-Ramon Blanco, Victoria Hernando, Heiner C. Bucher, Helen Kovari, Ferran Segura, Juan Ambrosioni, Charalambos Gogos, Nikos Pantazis, Francois Dabis, Marie-Anne Vandehende, Laurence Meyer, Rémonie Seng, John Gill, Hartmut Krentz, Andrew Phillips, Kholoud Porter, Beatriz Grinsztejn, Antonio G. Pacheco, Roberto Muga, Janet Tate, Amy Justice; Study design: Sara Lodi, Miguel Hernan; Statistical analyses: Sara Lodi, Roger Logan; Drafted the manuscript: Sara Lodi, Miguel Hernan. Interpretation of results: All authors; Read and approved the manuscript: All authors; Revised the work for important intellectual content: All authors; Sara Lodi, the corresponding author, had complete access to all data on the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of any data analysis.

The list of contributors to the HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration is in Appendix 5.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest

HC Bucher or his institution has received honorarium, support to attend conferences or unrestricted research grants from Gilead Sciences, BMS, Viiv Healthcare, Janssen, Abbvie, MSD in the last 3 years preceding the submission date of this manuscript. JR Blanco has carried out consulting work for Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare; has received compensation for lectures from Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare, as well as grants and payments for the development of educational presentations for Gilead Sciences, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and VIIV Healthcare. A Phillips has received payment for invited presentations from Gilead Sciences. S Jose received speakers fees from Gilead. C Sabin received funding from Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare and Janssen-Cilag for the membership of Data Safety and Monitoring Boards, Advisory Boards, Speaker Panels and for the preparation of educational materials. A van Sighem reports grants from Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, during the conduct of the study; grants from European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, personal fees from ViiV Healthcare, personal fees from Gilead Sciences, personal fees from Janssen-Cilag, outside the submitted work. Marie-Anne Vandehende received travel/meeting expenses from Gilead and Jansen-Cilag during the 36 months prior to submission.

References

- 1.Insight Start Study Group. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Temprano ANRS Study Group. A Trial of Early Antiretrovirals and Isoniazid Preventive Therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):808–822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panel on antiretroviral guidelines for adults and adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. [Accessed 30 November 2016];2016 https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf.

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO) Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. [Accessed 30 November 2016];2016 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/246200/1/9789241511124-eng.pdf?ua=1. [PubMed]

- 5.European AIDS clinical society (EACS) European guidelines for treatment of HIV infected adults in Europe. [Accessed 30 November 2016];2016 http://www.eacsociety.org/files/guidelines_8.1english.pdf.

- 6.Althoff KN, Gange SJ, Klein MB, et al. Late presentation for human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(11):1512–1520. doi: 10.1086/652650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO Regional Office for Europe. HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2012. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Center for Disease Control C. HIV Surveillance Report: Diagnoses of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe Study Group. Sabin CA, Smith CJ, et al. Response to combination antiretroviral therapy: variation by age. Aids. 2008;22(12):1463–1473. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f88d02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grabar S, Kousignian I, Sobel A, et al. Immunologic and clinical responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy over 50 years of age. Results from the French Hospital Database on HIV. Aids. 2004;18(15):2029–2038. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200410210-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufmann GR, Furrer H, Ledergerber B, et al. Characteristics, determinants, and clinical relevance of CD4 T cell recovery to <500 cells/microL in HIV type 1-infected individuals receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(3):361–372. doi: 10.1086/431484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schouten J, Wit FW, Stolte IG, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the prevalence of age-associated comorbidities and their risk factors between HIV-infected and uninfected individuals: the AGEhIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(12):1787–1797. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krentz HB, Gill MJ. The Impact of Non-Antiretroviral Polypharmacy on the Continuity of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Among HIV Patients. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(1):11–17. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greene M, Justice AC, Lampiris HW, Valcour V. Management of human immunodeficiency virus infection in advanced age. Jama. 2013;309(13):1397–1405. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.May MT, Hogg RS, Justice AC, et al. Heterogeneity in outcomes of treated HIV-positive patients in Europe and North America: relation with patient and cohort characteristics. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(6):1807–1820. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ancelle-Park R. Expanded European AIDS case definition. Lancet. 1993;341(8842):441. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)93040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robins J, Hernan M. Estimation of the causal effects of time-varying exposures. In: Fitzmaurice GD, Verbeke M, Molenberghs G, editors. Advances in longitudinal data analysis. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC Press; 2009. pp. 553–599. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology. 2004;15(5):615. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000135174.63482.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robins JM. A new approach to causal inference in mortality studies with a sustained exposure period: application to the healthy worker survivor effect. Mathematical Modelling. 1986;7(9-12):1393–1512. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taubman SL, Robins JM, Mittleman MA, Hernan MA. Intervening on risk factors for coronary heart disease: an application of the parametric g-formula. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(6):1599–1611. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young JG, Cain LE, Robins JM, O'Reilly EJ, Hernan MA. Comparative effectiveness of dynamic treatment regimes: an application of the parametric g-formula. Stat Biosci. 2011;3(1):119–143. doi: 10.1007/s12561-011-9040-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lodi S, Phillips A, Logan R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of strategies for antiretroviral treatment initiation in HIV-positive individuals in high-income countries: an observational cohort study of immediate universal treatment versus CD4-based initiation. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(8):e335–e343. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00108-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molina JM, Grund B, Gordin F, et al. Who benefited most from immediate treatment in START? A subgroup analysis. 21st International AIDS Conference; Durban: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mocroft A, Lundgren JD, Sabin ML, et al. Risk factors and outcomes for late presentation for HIV-positive persons in Europe: results from the Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe Study (COHERE) PLoS Med. 2013;10(9):e1001510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Center for Disease Control C. Diagnoses of HIV infectons in the United States and dependent areas, 2014. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lodi S, Dray-Spira R, Touloumi G, et al. Delayed HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy: inequalities by educational level, COHERE in EuroCoord. Aids. 2014;28(15):2297–2306. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Center for Disease Control C. Diagnoses of HIV infection among adults aged 50 years and older in the United States and dependent areas, 2010-2014. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Babiker AG, Peto T, Porter K, Walker AS, Darbyshire JH. Age as a determinant of survival in HIV infection. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(Suppl 1):S16–21. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00456-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lodi S, Phillips A, Touloumi G, et al. Time from human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion to reaching CD4+ cell count thresholds <200, <350, and <500 Cells/mm(3): assessment of need following changes in treatment guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(8):817–825. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costagliola D. Demographics of HIV and aging. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9(4):294–301. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kramarow E, Pastor P. NCHS Data Brief. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. The Health of Male Veterans and Nonveterans Aged 25–64 United States, 2007–2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edwards JK, Cole SR, Westreich D. Age at Entry Into Care, Timing of Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation, and 10-Year Mortality Among HIV-Seropositive Adults in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(7):1189–1195. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernando V, Sobrino-Vegas P, Burriel MC, et al. Differences in the causes of death of HIV-positive patients in a cohort study by data sources and coding algorithms. Aids. 2012;26(14):1829–1834. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328352ada4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Touloumi G. Assessing the representativeness of European HIV cohorts participants as compared to HIV Surveillance data- an ECDC Project. HepHIV 2017 Conference: HIV and Viral Hepatitis: Challenges of Timely Testing and Care; Malta: 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.