Abstract

Addiction has been proposed as a ‘reward deficient’ state which is compensated for with substance use. There is growing evidence of dysregulation in the opioid system, which plays a key role in reward, underpinning addiction. Low levels of endogenous opioids are implicated in vulnerability for developing alcohol dependence (AD) and high mu-opioid receptor (MOR) availability in early abstinence is associated with greater craving. This high MOR availability is proposed to be the target of opioid antagonist medication to prevent relapse. However, changes in endogenous opioid tone in AD are poorly characterised and are important to understand as opioid antagonists do not help everyone with AD. We used [11C]carfentanil, a selective mu-opioid receptor (MOR) agonist PET radioligand, to investigate endogenous opioid tone in AD for the first time. We recruited 13 abstinent male AD and 15 control participants who underwent two [11C]carfentanil PET scans, one before and one 3 hours following a 0.5 mg/kg oral dose of dexamphetamine to measure baseline MOR availability and endogenous opioid release. We found significantly blunted dexamphetamine-induced opioid release in 5 out of 10 regions-of-interest including insula, frontal lobe and putamen in AD compared with controls, but no significantly higher MOR availability AD participants compared with HC in any region. This study is comparable to our previous results of blunted dexamphetamine-induced opioid release in gambling disorder, suggesting that this dysregulation in opioid tone is common to both behavioural and substance addictions.

Introduction

Alcohol dependence affects 4% of adults in Europe and 4.7% in the US, and globally 3.3 million deaths per year (5.9% of deaths worldwide) are attributed to harmful alcohol use 1. Treatment for alcohol abuse and dependence costs an estimated $12 billion in the US and €5 billion in the EU 2,3, however three quarters of individuals with alcohol dependence will not remain abstinent from alcohol in the first year following treatment 4. Thus, there is a substantial unmet need in reducing this harm.

Psychosocial approaches are the mainstay treatment of alcohol dependence but effective relapse prevention medications, including the opioid antagonists naltrexone and nalmefene, are available 5–7. Opioid antagonists modulate the mesolimbic ‘reward’ pathway, which is proposed to underpin their effectiveness in reducing the risk of relapse to heavy drinking 5,7–9. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), naltrexone and nalmefene have been shown to reduce brain responses in the mesolimbic pathway to salient alcohol cues or exposure 10,11. These medications do not help everyone and so a better understanding of opioid system function in alcoholism is required to develop improved therapies and better target individuals with current medication.

The mu opioid receptor (MOR) subtype is expressed in brain regions associated with addiction including the ventral tegmental area, nucleus accumbens and amygdala. The MOR and its endogenous ligands, including β-endorphin, play an important role in reward 12–14. Some substances of abuse, including alcohol and amphetamines, increase the levels of endogenous opioids binding to MORs and this is associated with positive subjective effects, including ‘best ever’ feelings and euphoria 15,16. Naltrexone has been shown to attenuate these positive subjective effects 17–19. Endogenous opioid dysregulation may also play an important role in the vulnerability to developing addiction where a ‘reward deficient’ state leads to substance abuse to compensate for opioidergic hypofunction 20,21.

Lower basal endogenous opioid levels in the brain may result in higher opioid receptor availability and this has been demonstrated in alcohol dependence during early abstinence using the non-selective radioligand [11C]diprenorphine 22 and the MOR selective radioligand [11C]carfentanil 23,24. Higher opioid receptor availability is associated with alcohol craving 22,23,25 and alcohol dependent individuals with higher [11C]carfentanil binding may benefit more from naltrexone treatment 25. This suggests that the effectiveness of opioid antagonists is linked to opioid receptor availability in humans. However, no studies have assessed in vivo endogenous opioid tone in alcohol dependence which is also key to understanding the predictors of response to opioid antagonists.

We have developed and validated a [11C]carfentanil positron emission tomography (PET) protocol to assess endogenous opioid release following an oral dexamphetamine challenge 15,26. With this protocol, we demonstrated no difference in baseline MOR availability but a blunted dexamphetamine-induced opioid release, with blunted associated subjective effects, in gambling disorder 27. In this study, we applied the same protocol to test the hypotheses that in alcohol dependence there is blunted dexamphetamine induced endogenous opioid release, as shown in gambling disorder, and a higher baseline MOR availability.

Patients and Methods

This study was approved by the West London Research Ethics Committee and the Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee, UK (14/LO/1552). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Alcohol dependent (AD) men (n=13, >4 weeks abstinent, DSM-5 criteria for ‘severe’ alcohol use disorder) were recruited from Central North West London NHS Foundation Trust, UK and associated services. Severity of alcohol dependence, relapse risk and alcohol craving were assessed using the Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (SADQ) 28, Time to Relapse Questionnaire (TRQ) 29 and Alcohol Urge Questionnaire (AUQ) 30. ‘High risk’ alcohol exposure was calculated as lifetime cumulative weeks with >60g average daily alcohol consumption 31. Male healthy controls (HC) (n=15) included ten from previous studies 15,26 and five recruited for the current study to achieve age-matching between groups.

All participants’ physical and mental health history, including history of alcohol, tobacco and substance use, was assessed by psychiatrists using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI-5) 32. Current or past history of gambling disorder or substance dependence (excluding nicotine) was an exclusion criterion; previous recreational drug use was allowed (>10 times in lifetime: cannabis: 3 HC, 9 AD, cocaine: 6 AD, stimulants: 5 AD, inhalants: 1 HC, 3 AD, hallucinogens: 1 AD, sedatives: 1 AD, 2 HC, opioids: 1 AD). HC were excluded if they drank >21 UK units of alcohol (166g) per week or had a previous history of alcohol dependence. Drug use (except nicotine) was not permitted 2 weeks prior to the study visits and confirmed by negative urine drug screen (cocaine, amphetamine, THC, methadone, opioids, benzodiazepines). Participants were breathalysed for alcohol. Smoking tobacco was not allowed 1 hour before each scan. All participants had laboratory and ECG results within normal range, and were not prescribed any regular psychotropic medications.

Participants with current or previous psychiatric disorders were excluded. However, in AD participants a past history of depression (non-psychotic) and/or anxiety disorders was permitted due to the high prevalence in this population. Depression was assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) 33 and anxiety with Spielberger State/Trait Inventory (SSAI and STAI) 34. Impulsivity was assessed with the UPPS-P Impulsive Behaviour Scale 35.

Genotyping

Blood samples for genotyping of OPRM1 A118G polymorphism were available from all participants (AD: n=13; HC: n=11) except for 4 HC from our first study 15 and were analysed by LGC Limited (Middlesex, UK). DNA was extracted and normalised and underwent SNP-specific KASP™ Assay mix. Loci with a call rate less than 90% were not included. Participants were categorised as a G-allele carrier (G:A or G:G) or not (A:A).

PET and MR Imaging protocol

We followed our protocol as previously described 15,26,27. [11C]carfentanil PET scans were acquired on a HiRez Biograph 6 PET/CT scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Dynamic emission data were collected continuously for 90 min (26 frames, 8 × 15 s, 3 × 60 s, 5 × 120 s, 5 × 300 s, 5 × 600 s) following an intravenous bolus infusion of maximum 350MBq [11C]carfentanil infused over 20 seconds. Participants underwent two [11C]carfentanil PET scans, one before and one 3 hours following the oral administration of 0.5mg/kg dexamphetamine. 7 participants (n=1 AD, n=7 HV) underwent scans on separate days. However, there were no significant effects of this on [11C]carfentanil binding potential (BPND).

Subjective responses to dexamphetamine challenge were measured with the Simplified Amphetamine Interview Rating Scale (SAIRS) (15 mins pre-dose (baseline), 1, 2, 3, 4.5h post-dose) 36, and Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory (SSAI) (before and after each PET scan).

Blood samples to measure plasma dexamphetamine levels were obtained pre-dose (baseline), 1, 2, 3, and 4.5 hours post-dosing. Dexamphetamine samples were analysed at the Drug Control Centre, Analytical and Environmental Sciences, King's College London, UK. Serum cortisol samples were collected immediately pre-dexamphetamine dose (baseline), 30, 60, 90, 120, 150 and 180 minutes post-dose. Cortisol samples were analysed using the ARCHITECT cortisol assay at the Pathology Department, Hammersmith Hospital, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK. See Supplementary data for further details of cortisol and amphetamine assays.

On a different day to their PET scans, participants underwent a T1-weighted structural MRI (Magnetom Trio Syngo MR B13 Siemens 3T; Siemens AG, Medical Solutions). Subjects completed the ICCAM fMRI imaging platform 37,38 and these results will be reported elsewhere.

Image Analysis

As described previously 15,26,27, image pre-processing and PET modelling were carried out using MIAKAT (www.miakat.org). Dynamic PET data underwent motion correction and rigid-body coregistration to the structural MRI. Ten bilateral Regions-of-interest (ROI) were chosen a priori: caudate, putamen, thalamus, cerebellum grey matter, frontal lobe grey matter, nucleus accumbens, anterior cingulate, amygdala, insular cortex and hypothalamus. All time-activity data, except the hypothalamus, were sampled using a neuroanatomical atlas 39. This was applied to the PET image by non-linear deformation parameters derived using unified segmentation (SPM-12) of the structural MRI. The template and atlas fits were confirmed visually for each participant. The hypothalamus was manually defined on individual structural MRIs as previously described 15,39.

[11C]carfentanil BPND values were quantified using the simplified reference tissue model with occipital lobe as the reference region 15,40. BPND is the ratio of specifically bound radioligand (e.g. bound to MOR) to that of non-displaceable radioligand (e.g. unbound and non-specifically or non-MOR bound [11C]carfentanil) in tissue at equilibrium. BPND used in reference tissue methods compares the concentration of radioligand in receptor-rich with receptor-free regions 41. Reductions in [11C]carfentanil BPND observed following dexamphetamine challenge are due to reductions in specific [11C]carfentanil binding to MORs associated with endogenous opioid release, compared with non-specific [11C]carfentanil binding in the occipital lobe reference region. Endogenous opioid release was indexed as the fractional reduction in [11C]carfentanil BPND following dexamphetamine:

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS (version 24). Data were normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk) except for BDI and abstinence duration.

Demographic differences between groups were assessed using independent sample t-tests. Omnibus mixed model ANOVA tested the effects of Status (AD or HC) on [11C]carfentanil BPND and ∆BPND, SAIRS and SSAI subjective responses, plasma amphetamine and serum cortisol concentrations. Post-hoc tests were made using one-way ANOVA or t-tests. Correlational analyses were made using Pearson correlation coefficient or Spearman’s rho (BDI and abstinence duration). Bonferroni corrected p-values are reported in the results. Data were tested for sphericity, and where sphericity was violated ANOVAs were Greenhouse-Geisser corrected.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Variables

Demographic results are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age or IQ between HC and AD participants. More AD participants smoked tobacco but there were no differences between daily numbers of cigarettes or dependence scores (FTND) between HC and AD smokers. AD participants had significantly higher BDI and STAI scores than HC but none reached a threshold for clinical anxiety or depression. UPPS-P negative urgency scores were higher in AD participants compared with HC.

Table 1. Demographic and genotype data (mean ± SD).

| Healthy Controls | Alcohol Dependence | p-value (two-tailed) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers | 15 | 13 | |

| Age | 42.8 (±10.2) | 46.6 (±7.3) | 0.281 |

| IQ | 115.6 (±9.9) | 107.8 (+10.7) | 0.090 |

| Alcohol UK units/week | 6.67 (±8.2) | 0 | |

| Current Smokers | 3 | 7 | |

| Cigarettes per day (current smokers) | 10.0 (±5.0) | 10.6 (±7.7) | 0.247 |

| Pack years (current and ex-smokers) | 7.9 (±8.1) | 23.6 (±14.5) | 0.063 |

| FTND (current smokers) |

3.0 (±2.7) | 3.7 (±3.1) | 0.906 |

| BDI on PET visit | 0.2 (±0.6) | 3.3 (±3.6) | 0.004 |

| STAI | 30.3 (±7.4) | 37.2 (±5.9) | 0.012 |

| SSAI (before PET 1) | 27.9 (±6.6) | 28.8 (±9.9) | 0.797 |

| UPPS-negative urgency | 20.8 (±6.1) | 27.4 (±4.1) | 0.006 |

| SADQ | 38.5 (±11.2) | ||

| TRQ | 18.9 (±5.1) | ||

| Alcohol Abstinence (days) | 9.6 (±12.7) | 604.6 (±866.5) | <0.001 |

| OPRM1 G-allele carrier | 2 of 11 (18.2%) | 4 of 13 (30.1%) |

Abbreviations: Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Spielberger State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (SSAI, STAI), UPPS Impulsivity Scale (UPPS), Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (SADQ), Time to Relapse Questionnaire (TRQ)

Injected Mass and Radioactivity and Head Motion

There were no significant differences in injected cold carfentanil mass between AD participants and HC for either scan, but there was a significantly higher injected activity in post-dexamphetamine scans in AD participants (Supplementary Table 1). There were no significant correlations between [11C]carfentanil BPND in any region and injected mass or activity in the pre- or post-dexamphetamine scans. There was no significant effect of dexamphetamine on movement within scans, or differences between AD and HC participants (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Dexamphetamine and Cortisol Pharmacokinetics

A repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant effect of Time on dexamphetamine plasma concentrations but no significant effect of Status (AD or HC) (Supplementary Figure 4, Supplementary Table 5).

Serum cortisol concentration increased following oral dexamphetamine administration (Supplementary Figure 6). A mixed-model ANOVA showed a significant effect of Time on cortisol levels but no significant effect of Status (AD or HC) (Supplementary Table 5).

Subjective Effects of Amphetamine

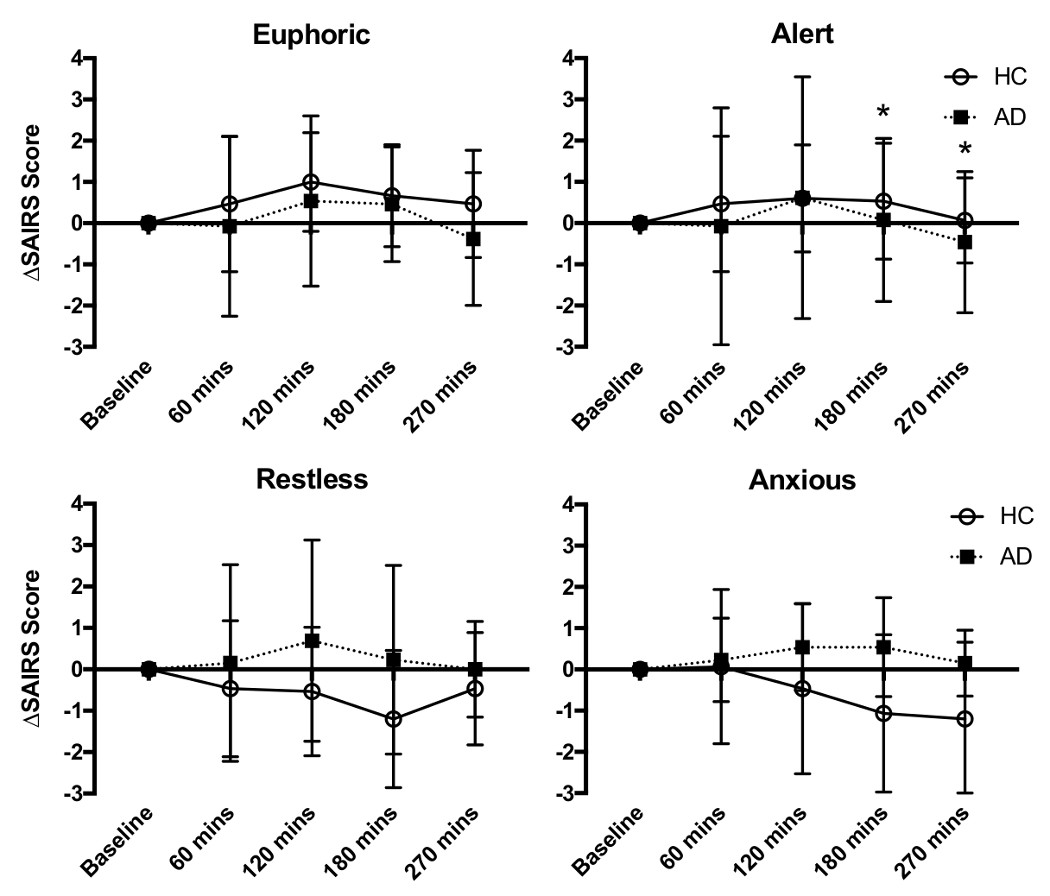

The subjective effects from the oral dexamphetamine were mild in both groups (Figure 1). A mixed-model ANOVA showed no significant effects of Time or Status (AD or HC) on changes in SAIRS scores from baseline (Supplementary Table 7). There was a significant Time x Status interaction on change in SAIRS Anxiety from baseline. Post-hoc analysis (paired t-test) showed reductions in anxiety ratings in HC at 180 and 270 mins post-dexamphetamine (p=0.048 and p=0.025 respectively, Bonferroni corrected p<0.01) which was not present in the AD group. There was no significant effect of Time or Status on SSAI scores.

Figure 1.

Change in SAIRS following dexamphetamine administration (mean ± SD, *p<0.05 in HC)

Pre- and Post-dexamphetamine [11C]carfentanil BPND

A mixed-model ANOVA examining pre- and post-dexamphetamine [11C]carfentanil BPND showed a significant effect of Scan (pre- or post-dexamphetamine) demonstrating differences in BPND following dexamphetamine, and a significant Scan x Status interaction indicating a significantly different change in BPND after dexamphetamine between AD and HC (Supplementary Table 8). Post-hoc paired t-tests showed significant reductions in BPND after oral dexamphetamine in HC across all ROIs except hypothalamus and amygdala, but no significant reductions in AD participants (Supplementary Table 9).

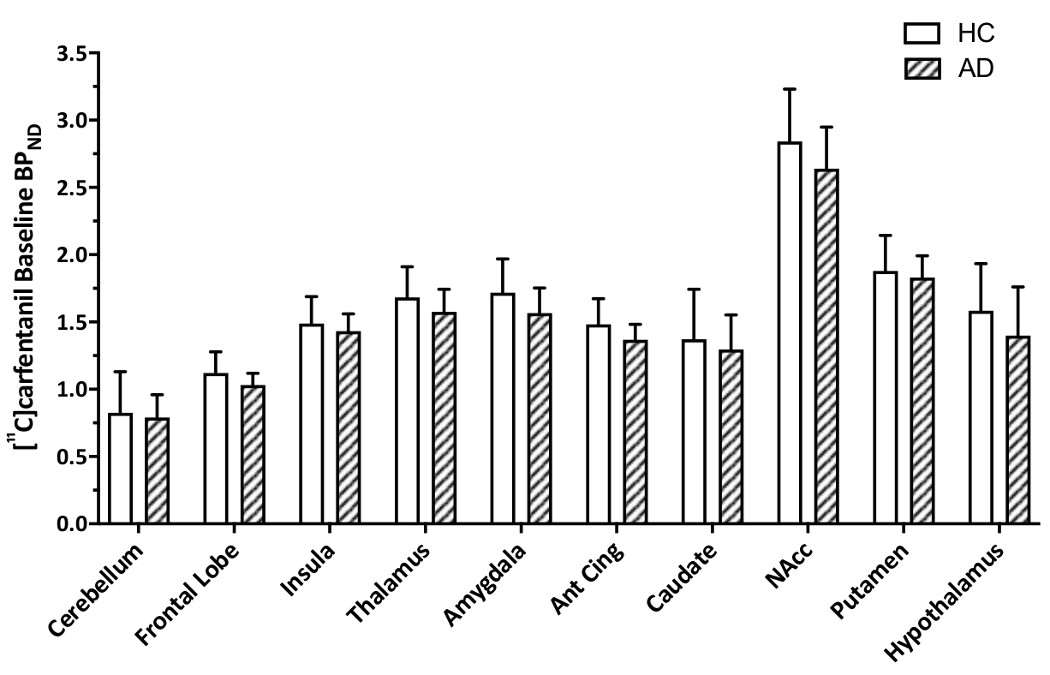

A mixed-model ANOVA examining pre-dexamphetamine [11C]carfentanil BPND showed no significant effect of Status indicating no differences between AD and HC participants (Figure 2, Supplementary Tables 8 and 9).

Figure 2.

Baseline [11C]carfentanil BPND in HC and AD participants (mean ± SD)

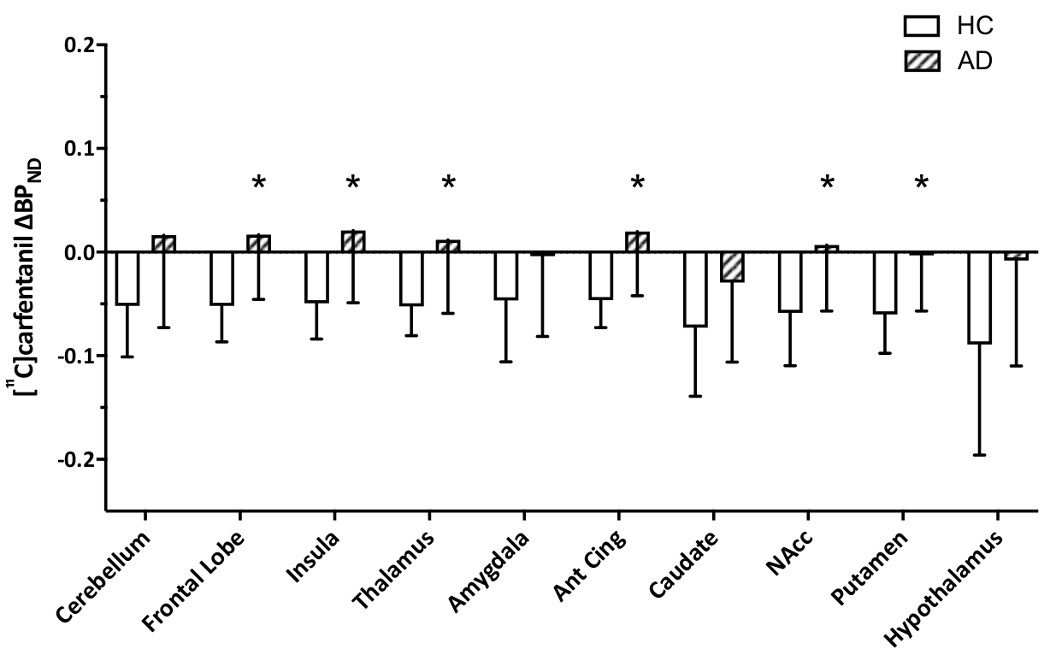

A mixed-model ANOVA examining [11C]carfentanil ∆BPND showed a significant effect of Status, indicating differences between AD and HC participants. Independent sample t-tests showed [11C]carfentanil ∆BPND (i.e. opioid release) was significantly blunted in AD participants, compared with HC, in the frontal lobe, insula, thalamus, anterior cingulate and putamen (Bonferroni corrected p<0.005) with large effect sizes (Cohen’s D >0.8, significant t-tests comparing [11C]carfentanil ∆BPND between HC and AD) (Figures 3 and 4, Supplementary Tables 8 and 9).

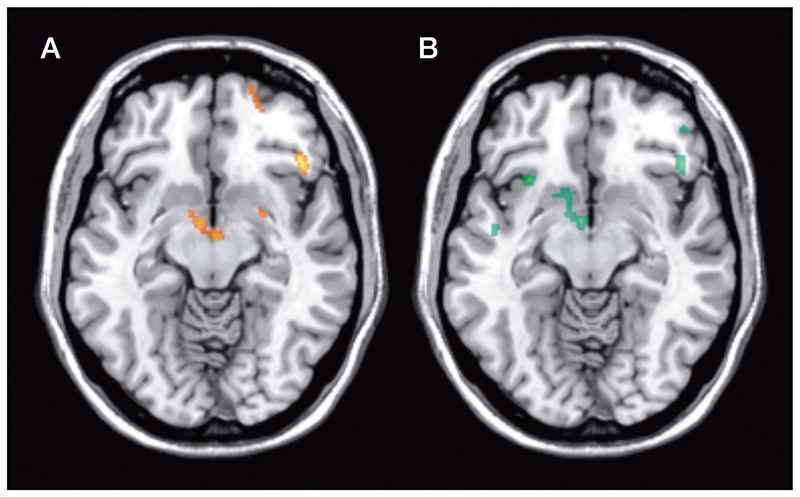

Figure 3.

[11C]carfentanil ∆BPND in HC and AD participants (mean ± SD, *significant ∆BPND differences between HC and AD, Bonferroni corrected p<0.005)

Figure 4.

A Clusters with significant reductions in [11C]carfentanil BPND following dexamphetamine in HC. There are no significant clusters in AD. B Clusters with significantly lower [11C]carfentanil ∆BPND in AD compared with HC (all images: min cluster size 100, p<0.001, z=62)

[11C]carfentanil binding, demographic and clinical variables

We found no significant correlations between [11C]carfentanil BPND and ∆BPND with SADQ, TRQ, duration/length of alcohol abstinence or exposure measures in AD participants. Of note, AD did not report any AUQ craving at baseline or at any other point during the study. There were no significant differences in [11C]carfentanil BPND or ∆BPND comparing smokers with non-smokers regardless of group (combined AD and HC or AD and HC separately). The inclusion of smoking status in the mixed-model ANOVA examining [11C]carfentanil ∆BPND did not impact on these results (Supplementary Table 8). There were no significant correlations between [11C]carfentanil BPND or ∆BPND with daily cigarettes smoked or FTND scores in all participants (AD and HC) or AD or HC separately.

There was no significant association between UPPS-P negative urgency and baseline [11C]carfentanil BPND in AD or HC participants. There was a significant positive correlation between [11C]carfentanil ∆BPND in the amygdala and BDI score (Spearman’s rho=0.654, p=0.015) in AD only, indicating a higher BDI score is associated with lower opioid release. This result did not survive Bonferroni correction (two-tailed p<0.005). There were no correlations between STAI and [11C]carfentanil BPND or ∆BPND in either participant group.

MOR polymorphism

There was a higher G-allele prevalence in AD participants compared with HC (30.1% and 18.2% respectively – Table 1). To assess the influence of the OPRM1 A118G polymorphism on [11C]carfentanil BPND the two mixed-model ANOVAs examining [11C]carfentanil BPND and ∆BPND were repeated with the addition of the genotype (A:A or A:G/G:G) as a between-subject factor.

We found a significant main effect of Genotype on baseline [11C]carfentanil BPND, but no Status x Genotype interaction. A post-hoc independent sample t-test showed significantly lower [11C]carfentanil BPND in G-allele carriers in the thalamus (two-tailed Bonferroni corrected p<0.005), and a trend towards lower [11C]carfentanil BPND across all other regions (Supplementary Figure 10, Tables 11 and 12). We found no significant main effect of Genotype or Status x Genotype interaction on [11C]carfentanil ∆BPND.

Discussion

We have demonstrated a blunted dexamphetamine-induced endogenous opioid release in the brain for the first time in abstinent alcohol dependent individuals with [11C]carfentanil PET. We did not find higher baseline MOR availability in alcohol dependence as previously reported by ourselves and others 22,23,42. Our data in alcohol dependence is consistent with our previous study in gambling disorder where we also found blunted dexamphetamine-induced opioid release 27. This strongly suggests that dysregulation of opioid tone underpins both behavioural and substance addictions.

This ‘opioid deficient’ state may play a key role in a broader ‘reward deficient’ state associated with the development and maintenance of alcohol dependence and other addictions, and may precede the development of addiction 20,21,27,43–45. Individuals with alcohol dependence or a family history of alcohol dependence both have blunted responses to financial rewards and lower peripheral plasma β-endorphin concentrations 43,44,46. Although peripheral and central β-endorphin are not directly comparable, both are produced from the cleavage of pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) and the release of both can be stimulated by intense exercise, dexamphetamine and alcohol 15,16,46–49. This low opioidergic function may represent a vulnerability to the development of addiction which endures after successful treatment and may predispose an individual to relapse. There may be an additional impact of addiction or heavy alcohol use on endogenous opioid tone, though this is difficult to determine from our current [11C]carfentanil PET studies.

There is evidence of blunted intravenous dexamphetamine-induced dopamine release in alcohol dependence during early abstinence 50, which may be a mechanism for the blunted dexamphetamine-induced endogenous opioid release alcohol dependence. Another study reported that lower dexamphetamine-induced ventral striatal dopamine release was associated with blunted cortisol release 51. However, in our alcohol dependent participants dexamphetamine-induced cortisol release was not blunted compared with controls. This may suggest that dopamine responses to dexamphetamine are less blunted in our alcohol dependent participants, with longer durations of abstinence, than those described in early abstinence 50.

The blunted dexamphetamine-induced endogenous opioid release in alcohol dependence may be mediated by a mechanism downstream from dopamine release, which would be consistent with the findings of blunted endogenous opioid release in gambling disorder despite a higher dopamine response to oral dexamphetamine 27,52. Intravenous dexamphetamine increases striatal dopamine concentrations in man within minutes of administration 50,53,54 but does not result in similarly acute changes in opioid levels in the brain 55. A period of 1.5 to 3 hours following dexamphetamine administration is required to reach peak endogenous opioid concentrations 15,26,27,56,57, suggesting that the mechanism of dexamphetamine-induced endogenous opioid release is also downstream of the acute dopamine release. Concentrations of other monoamines (5HT and noradrenaline) are also increased by dexamphetamine, and may play a role in endogenous opioid release in brain regions with lower dopamine transporter density, such as the frontal cortex and thalamus 15,58. Further work is required to better understand the mechanisms of dexamphetamine-induced endogenous opioid release, and how this is blunted in both alcohol dependence and gambling disorder.

The salience of our dexamphetamine ‘reward’ may also be a factor in mediating endogenous opioid release. As addiction develops, salience towards addiction-associated cues increases whilst responses to non-addiction related rewards decrease 59,60. For example, individuals with alcohol dependence have blunted fMRI responses to non-salient financial rewards and higher responses to salient alcohol cues 43,44,61–63. The effect of opioid antagonists to modulate the mesolimbic system also appears to be mediated by the salience of the reward. For example, naltrexone only blunts dexamphetamine-induced striatal dopamine release in rats following a period of dexamphetamine sensitisation 54. Whilst naltrexone does not modulate striatal fMRI response to financial reward anticipation in alcohol dependence 43, when the same task was performed during an alcohol infusion, a salient context, nalmefene reduces activation 11. Naltrexone also reduces BOLD response in striatum to salient alcohol cues in alcohol dependent individuals 10,64. This salience mediated endogenous opioid release, rather than low opioidergic tone, may the target for opioid receptor antagonists in reducing the risk of relapse to heavy drinking during abstinence.

Whilst the above evidence suggests that salience is an important factor for the activation of endogenous opioidergic signalling, a recent study has shown that feeding induces a release of endogenous opioids regardless of how palatable or ‘rewarding’ the food is 65. One potential further study to elucidate the effect of the salience of a reward on endogenous opioid release in alcohol dependence would be the administration of an alcohol challenge, where a non-blunted, or possibly enhanced, endogenous opioid release might be observed. However, this would not be an ethical experiment to conduct in our abstinent alcohol dependent participants.

Contrary to our hypothesis we did not find higher MOR availability in alcohol dependent participants compared with controls. Previous studies using [11C]carfentanil and [11C]diprenorphine have shown higher MOR in alcohol dependence, whilst in our data there was no evidence of higher MOR availability in our alcohol dependent participants (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 9) 22–24. Hermann et al. 25 reported non-significantly higher [11C]carfentanil binding in recently abstinent alcohol dependent individuals and lower MOR receptor numbers in post-mortem alcohol dependent brains measured with the MOR agonist [3H]DAMGO. They proposed that repeated alcohol administration in alcohol dependence, and the subsequent chronic elevations in endogenous opioids, may lead to a compensatory reduction in absolute MOR numbers 25. Chronic alcohol-induced endogenous opioid release may also lower basal endogenous opioid tone via homeostatic feedback mechanisms, potentially through an inhibition of POMC activity 66. This low endogenous tone, when coupled with a cessation of alcohol-induced opioid release, may lead to a relative increase in MOR availability in early abstinence, despite lower absolute MOR density.

It is unclear if there are changes in basal endogenous opioid tone or MOR receptor numbers as abstinence lengthens. Alcohol dependent participants in our current study have a considerably longer abstinence compared with previous studies (months compared with days to weeks) 22–24 and have ‘normal’ MOR availability. This would be consistent with a ‘normalisation’ of the balance of MORs and endogenous opioid ligands as abstinence progresses. However, we did not observe any association between duration of abstinence and MOR availability in our current study and we and others have reported no changes in MOR or other opioid receptor availability in alcohol dependence during the first 3 months of abstinence 22,23. Higher MOR availability associated with higher craving reported previously in alcohol dependence may represent a greater potential to relapse, and a potential target for opioid receptor antagonist treatment. The lack of higher MOR availability in our alcohol dependent participants may reflect their stable abstinence and low craving, and suggests these individuals may benefit less from opioid receptor antagonist treatment compared with recently abstinent individuals reporting high alcohol craving.

We explored a number of clinical variables that may influence [11C]carfentanil binding. Although smoking status differed in our alcohol dependent and control groups, there was no influence of current smoking, or associated measures, on baseline MOR availability or dexamphetamine-induced endogenous opioid release. Previous evidence concerning MOR in smokers is inconsistent, with higher, lower, or no differences in availability compared with non-smokers reported 67–69. Consistent with others, we found that OPRM1 G-allele carriers had lower MOR availability 70,71. We found no significant effect of the OPRM1 polymorphism on dexamphetamine-induced endogenous opioid release, whilst others have observed lower endogenous opioid release in G-allele carriers during a pain task following placebo administration 71. In gambling disorder we demonstrated a positive correlation between the UPPS-P negative urgency and baseline MOR availability in the caudate 27 but we did not replicate this finding in our alcohol dependent group. This is consistent with previous evidence showing correlations between impulsivity and [11C]raclopride (D2/3) and [11C]-(+)-PHNO (D3-preferring) in gambling disorder and cocaine dependence but no such correlations between [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding and impulsivity in alcohol dependence 72–75. This suggests that the nature of impulsivity in alcohol dependence may differ from cocaine and gambling disorders.

An exploratory analysis found that higher levels of depressive symptoms (BDI score) were associated with a blunted endogenous opioid release in the amygdala, although this result does not survive a strict Bonferroni correction for multiple correlations. The amygdala is an important region for emotional processing in depression 76, and endogenous opioid release in the amygdala is associated with positive emotion and exercise induced negative emotion, and is dysregulated in major depressive disorder 48,77–79. One reason for this association being observed only in alcohol dependent participants may be due to a higher and greater range of BDI scores compared with controls. These scores were, however, low and did not reach a threshold for clinically significant depression.

Our study was designed to be adequately powered for our primary outcome of [11C]carfentanil ∆BPND and our samples size is consistent with those in other relevant published human PET literature examining amphetamine induced endogenous neurotransmitter release 15,26,27,50,52,80. Our study sample size is too small to adequately investigate clinical factors that may be associated with our PET outcome measures.

In summary, we have demonstrated for the first time blunted dexamphetamine-induced opioid release in the brain in abstinent alcohol dependent individuals. This study adds to the evidence supporting a role for a dysregulated opioid system in alcohol dependence and builds on our previous study with the same protocol in gambling disorder showing similarly blunted dexamphetamine-induced opioid release in the presence of ‘normal’ MOR availability. The similarly blunted opioid release in gambling disorder where participants had no history of substance dependence, excluding nicotine, lends further support to an ‘opioid deficit’ contributing to vulnerability to addiction. Thus, dysregulated opioid signalling appears to be a common feature across both behavioural and substance addictions.

Further characterisation of the endogenous opioid tone and the dopamine–opioid interactions will inform our understanding of substance and behavioural addictions and how best to optimise and develop the use of opioid antagonists in treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information is available at Molecular Psychiatry’s website

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the study participants and the clinical team at Imanova, Centre for Imaging Sciences. This article presents independent research funded by the Medical Research Council (Grant G1002226) and Imperial College BRC and supported by the NIHR Imperial Clinical Research Facility at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Medical Research Council, Imperial College BRC, the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

• Professor Lingford-Hughes has received honoraria paid into her institutional funds for speaking and chairing engagements from Lundbeck, Lundbeck Institute UK and Janssen-Cilag. She has received research support from Lundbeck and has been consulted by but received no monies from Britannia Pharmaceuticals.

• Professor Nutt has consulted for, or received speaker's fees, or travel or grant support from the following companies with an interest in the treatment of addiction: RB pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, GSK, Pfizer, D&A Pharma, Nalpharm, Opiant Pharmaceutical and Alkermes.

• Professor Gunn is a consultant for Abbvie and Cerveau.

• Dr Rabiner is a consultant for Opiant Pharmaceutical, AbbVie, Teva, and a shareholder in GSK.

• Professor Waldman has received honoraria from Bayer, Novartis, and GSK, and has been a consultant for Bayer.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. Glob status Rep alcohol. 2014:1–392. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE, Brewer RD. 2010 National and State Costs of Excessive Alcohol Consumption. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:e73–e79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson P, Baumberg B. Alcohol in Europe – Public Health Perspective: Report summary. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 2006;13:483–488. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller WR, Walters ST, Bennett ME. How effective is alcoholism treatment in the United States? J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:211–220. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lingford-Hughes A, Welch S, Peters L, Nutt D. BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: recommendations from BAP. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:899–952. doi: 10.1177/0269881112444324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NHS NI for H and CE. Alcohol-use disorders : diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking and alcohol dependence. Natl Collab Cent Ment Heal. 2011:1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rösner S, Hackl-Herrwerth A, Leucht S, Vecchi S, Srisurapanont M, Soyka M. Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anton RF, Moak DH, Waid LR, Latham PK, Malcolm RJ, Dias JK. Naltrexone and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for the Treatment of Outpatient Alcoholics: Results of a Placebo-Controlled Trial A few well-controlled clinical trials with limited. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1758–1764. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chick J, Anton R, Checinski K, Croop R, Drummond DC, Farmer R, et al. A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence or abuse. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35:587–93. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.6.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myrick H, Anton RF, Li X, Henderson S, Randall PK, Voronin K, et al. Effect of Naltrexone and Ondansetron on Alcohol Cue–Induced Activation of the Ventral Striatum in Alcohol-Dependent People. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:466. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.4.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quelch DR, Mick I, McGonigle J, Ramos AC, Flechais RSA, Bolstridge M, et al. Nalmefene Reduces Reward Anticipation in Alcohol Dependence: An Experimental Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81:941–948. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peciña S. Opioid reward ‘liking’ and ‘wanting’ in the nucleus accumbens. Physiol Behav. 2008;94:675–680. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berridge KC, Kringelbach ML. Pleasure Systems in the Brain. Neuron. 2015;86:646–664. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Merrer J, Becker JAJ, Befort K, Kieffer BL. Reward Processing by the Opioid System in the Brain. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:1379–412. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colasanti A, Searle GE, Long CJ, Hill SP, Reiley RR, Quelch D, et al. Endogenous Opioid Release in the Human Brain Reward System Induced by Acute Amphetamine Administration. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell JM, O’Neil JP, Janabi M, Marks SM, Jagust WJ, Fields HL. Alcohol Consumption Induces Endogenous Opioid Release in the Human Orbitofrontal Cortex and Nucleus Accumbens. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayaram-Lindström N, Wennberg P, Hurd YL, Franck J. Effects of Naltrexone on the Subjective Response to Amphetamine in Healthy Volunteers. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:665–669. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000144893.29987.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCaul M, Wand GS, Eissenberg T, Rohde CA, Cheskin LJ. Naltrexone Alters Subjective and Psychomotor Responses to Alcohol in Heavy Drinking Subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:480–492. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davidson D, Palfai T, Bird C, Swift R. Effects of Naltrexone on Alcohol Self-Administration in Heavy Drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:195–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ulm RR, Volpicelli JR, Volpicelli LA. Opiates and alcohol self-administration in animals. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56(Suppl 7):5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oswald L, Wand G. Opioids and alcoholism. Physiol Behav. 2004;81:339–358. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams TM, Davies SJC, Taylor LG, Daglish MRC, Hammers A, Brooks DJ, et al. Brain opioid receptor binding in early abstinence from alcohol dependence and relationship to craving: An [11C]diprenorphine PET study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19:740–748. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinz A, Reimold M, Wrase J, Hermann D, Croissant B, Mundle G, et al. Correlation of Stable Elevations in Striatal μ-Opioid Receptor Availability in Detoxified Alcoholic Patients With Alcohol Craving. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:57. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weerts EM, Wand GS, Kuwabara H, Munro CA, Dannals RF, Hilton J, et al. Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of Mu- and Delta-Opioid Receptor Binding in Alcohol-Dependent and Healthy Control Subjects. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:2162–2173. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hermann D, Hirth N, Reimold M, Batra A, Smolka MN, Hoffmann S, et al. Low μ-Opioid Receptor Status in Alcohol Dependence Identified by Combined Positron Emission Tomography and Post-Mortem Brain Analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:606–614. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mick I, Myers J, Stokes PRA, Erritzoe D, Colasanti A, Bowden-Jones H, et al. Amphetamine induced endogenous opioid release in the human brain detected with [11C]carfentanil PET: replication in an independent cohort. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17:2069–2074. doi: 10.1017/S1461145714000704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mick I, Myers J, Ramos AC, Stokes PR, Erritzoe D, Colasanti A, et al. Blunted Endogenous Opioid Release Following an Oral Amphetamine Challenge in Pathological Gamblers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:1742–1750. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stockwell T, Hodgson R, Edwards G, Taylor C, Rankin H. The Development of a Questionnaire to Measure Severity of Alcohol Dependence. Addiction. 1979;74:79–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1979.tb02415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adinoff B, Talmadge C, Williams MJ, Schreffler E, Jackley PK, Krebaum SR. Time to Relapse Questionnaire (TRQ): A Measure of Sudden Relapse in Substance Dependence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:140–149. doi: 10.3109/00952991003736363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bohn MJ, Krahn DD, Staehler BA. Development and Initial Validation of a Measure of Drinking Urges in Abstinent Alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:600–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Witkiewitz K, Hallgren KA, Kranzler HR, Mann KF, Hasin DS, Falk DE, et al. Clinical Validation of Reduced Alcohol Consumption After Treatment for Alcohol Dependence Using the World Health Organization Risk Drinking Levels. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41:179–186. doi: 10.1111/acer.13272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The Development and Validation of a Structured Diagnostic Psychiatric Interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. Beck Depression Inventory II manual. 1996.

- 34.Spielberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Consult Psychol Press; 1983. pp. 4–26. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychol Assess. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Kammen DP, Murphy DL. Attenuation of the euphoriant and activating effects of d- and l-amphetamine by lithium carbonate treatment. Psychopharmacologia. 1975;44:215–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00428897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGonigle J, Murphy A, Paterson LM, Reed LJ, Nestor L, Nash J, et al. The ICCAM platform study: An experimental medicine platform for evaluating new drugs for relapse prevention in addiction. J Psychopharmacol. 2017;31:3–16. doi: 10.1177/0269881116668592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paterson LM, Flechais RS, Murphy A, Reed LJ, Abbott S, Boyapati V, et al. The Imperial College Cambridge Manchester (ICCAM) platform study: An experimental medicine platform for evaluating new drugs for relapse prevention in addiction. Part A: Study description. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:943–960. doi: 10.1177/0269881115596155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tziortzi AC, Searle GE, Tzimopoulou S, Salinas C, Beaver JD, Jenkinson M, et al. Imaging dopamine receptors in humans with [11C]-(+)-PHNO: Dissection of D3 signal and anatomy. Neuroimage. 2011;54:264–277. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lammertsma AA, Hume SP. Simplified Reference Tissue Model for PET Receptor Studies. Neuroimage. 1996;4:153–158. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, Fujita M, Gjedde A, Gunn RN, et al. Consensus Nomenclature for in vivo Imaging of Reversibly Binding Radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1533–1539. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weerts EM, Kim YK, Wand GS, Dannals RF, Lee JS, Frost JJ, et al. Differences in δ- and μ-Opioid Receptor Blockade Measured by Positron Emission Tomography in Naltrexone-Treated Recently Abstinent Alcohol-Dependent Subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:653–665. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nestor LJ, Murphy A, McGonigle J, Orban C, Reed L, Taylor E, et al. Acute naltrexone does not remediate fronto-striatal disturbances in alcoholic and alcoholic polysubstance-dependent populations during a monetary incentive delay task. Addict Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/adb.12444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murphy A, Nestor LJ, McGonigle J, Paterson L, Boyapati V, Ersche KD, et al. Acute D3 Antagonist GSK598809 Selectively Enhances Neural Response During Monetary Reward Anticipation in Drug and Alcohol Dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:1049–1057. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Addiction and the Brain Antireward System. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dai X, Thavundayil J, Gianoulakis C. Differences in the Peripheral Levels of β-endorphin in Response to Alcohol and Stress as a Function of Alcohol Dependence and Family History of Alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1965–1975. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000187599.17786.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldfarb AH, Jamurtas AZ. β-Endorphin Response to Exercise. Sport Med. 1997;24:8–16. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199724010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saanijoki T, Tuominen L, Tuulari JJ, Nummenmaa L, Arponen E, Kalliokoski K, et al. Opioid Release after High-Intensity Interval Training in Healthy Human Subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:246–254. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen MR, Nurnberger JI, Pickar D, Gershon E, Bunney WE. Dextroamphetamine infusions in normals result in correlated increases of plasma β-endorphin and cortisol immunoreactivity. Life Sci. 1981;29:1243–1247. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martinez D, Gil R, Slifstein M, Hwang DR, Huang Y, Perez A, et al. Alcohol dependence is associated with blunted dopamine transmission in the ventral striatum. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:779–786. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oswald LM, Wong DF, McCaul M, Zhou Y, Kuwabara H, Choi L, et al. Relationships among ventral striatal dopamine release, cortisol secretion, and subjective responses to amphetamine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:821–832. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boileau I, Payer D, Chugani B, Lobo DSS, Houle S, Wilson AA, et al. In vivo evidence for greater amphetamine-induced dopamine release in pathological gambling: a positron emission tomography study with [11C]-(+)-PHNO. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:1305–1313. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Drevets WC, Gautier C, Price JC, Kupfer DJ, Kinahan PE, Grace AA, et al. Amphetamine-induced dopamine release in human ventral striatum correlates with euphoria. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:81–96. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jayaram-Lindström N, Guterstam J, Häggkvist J, Ericson M, Malmlöf T, Schilström B, et al. Naltrexone modulates dopamine release following chronic, but not acute amphetamine administration: a translational study. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1104. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guterstam J, Jayaram-Lindström N, Cervenka S, Frost JJ, Farde L, Halldin C, et al. Effects of amphetamine on the human brain opioid system--a positron emission tomography study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:763–9. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olive MF, Koenig HN, Nannini MA, Hodge CW. Stimulation of endorphin neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens by ethanol, cocaine, and amphetamine. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC184. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Quelch DR, Katsouri L, Nutt DJ, Parker CA, Tyacke RJ. Imaging endogenous opioid peptide release with [11C]carfentanil and [3H]diprenorphine: influence of agonist-induced internalization. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:1604–12. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ciliax BJ, Drash GW, Staley JK, Haber S, Mobley CJ, Miller GW, et al. Immunocytochemical localization of the dopamine transporter in human brain. J Comp Neurol. 1999;409:38–56. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990621)409:1<38::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lubman D, Allen N, Peters L, Deakin J. Electrophysiological evidence that drug cues have greater salience than other affective stimuli in opiate addiction. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:836–842. doi: 10.1177/0269881107083846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:760–773. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00104-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andrews MM, Meda SA, Thomas AD, Potenza MN, Krystal JH, Worhunsky P, et al. Individuals family history positive for alcoholism show functional magnetic resonance imaging differences in reward sensitivity that are related to impulsivity factors. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:675–683. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wrase J, Schlagenhauf F, Kienast T, Wüstenberg T, Bermpohl F, Kahnt T, et al. Dysfunction of reward processing correlates with alcohol craving in detoxified alcoholics. Neuroimage. 2007;35:787–794. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schacht JP, Anton RF, Myrick H. Functional neuroimaging studies of alcohol cue reactivity: a quantitative meta-analysis and systematic review. Addict Biol. 2013;18:121–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schacht JP, Randall PK, Latham PK, Voronin KE, Book SW, Myrick H, et al. Predictors of Naltrexone Response in a Randomized Trial: Reward-Related Brain Activation, OPRM1 Genotype, and Smoking Status. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017 doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tuulari JJ, Tuominen L, de Boer FE, Hirvonen J, Helin S, Nuutila P, et al. Feeding Releases Endogenous Opioids in Humans. J Neurosci. 2017;37:8284–8291. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0976-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pennock RL, Hentges ST. Differential expression and sensitivity of pre- and postsynaptic opioid receptors regulating hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin neurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:281–288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4654-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nuechterlein EB, Ni L, Domino EF, Zubieta J-K. Nicotine-specific and non-specific effects of cigarette smoking on endogenous opioid mechanisms. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 2016;69:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scott DJ, Domino EF, Heitzeg MM, Koeppe RA, Ni L, Guthrie S, et al. Smoking Modulation of μ-Opioid and Dopamine D2 Receptor-Mediated Neurotransmission in Humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:450–457. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kuwabara H, Heishman SJ, Brasic JR, Contoreggi C, Cascella N, Mackowick KM, et al. Mu Opioid Receptor Binding Correlates with Nicotine Dependence and Reward in Smokers. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weerts EM, McCaul ME, Kuwabara H, Yang X, Xu X, Dannals RF, et al. Influence of OPRM1 Asn40Asp variant (A118G) on [11C]carfentanil binding potential: preliminary findings in human subjects. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16 doi: 10.1017/S146114571200017X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peciña M, Love T, Stohler CS, Goldman D, Zubieta J-K. Effects of the Mu Opioid Receptor Polymorphism (OPRM1 A118G) on Pain Regulation, Placebo Effects and Associated Personality Trait Measures. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:957–965. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Erritzoe D, Tziortzi A, Bargiela D, Colasanti A, Searle GE, Gunn RN, et al. In Vivo Imaging of Cerebral Dopamine D3 Receptors in Alcoholism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:1703–1712. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Clark L, Stokes PR, Wu K, Michalczuk R, Benecke A, Watson BJ, et al. Striatal dopamine D2/D3 receptor binding in pathological gambling is correlated with mood-related impulsivity. Neuroimage. 2012;63:40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Boileau I, Payer D, Chugani B, Lobo D, Behzadi A, Rusjan PM, et al. The D2/3 dopamine receptor in pathological gambling: A positron emission tomography study with [11C]-(+)-propyl-hexahydro-naphtho-oxazin and [11C]raclopride. Addiction. 2013;108:953–963. doi: 10.1111/add.12066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Payer DE, Behzadi A, Kish SJ, Houle S, Wilson AA, Rusjan PM, et al. Heightened D3 dopamine receptor levels in cocaine dependence and contributions to the addiction behavioral phenotype: a positron emission tomography study with [11C]-+-PHNO. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:311–8. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Siegle GJ, Steinhauer SR, Thase ME, Stenger VA, Carter CS. Can’t shake that feeling: event-related fMRI assessment of sustained amygdala activity in response to emotional information in depressed individuals. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:693–707. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Koepp M, Hammers A, Lawrence A, Asselin M, Grasby P, Bench C. Evidence for endogenous opioid release in the amygdala during positive emotion. Neuroimage. 2009;44:252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kennedy SE, Koeppe RA, Young EA, Zubieta J-K. Dysregulation of Endogenous Opioid Emotion Regulation Circuitry in Major Depression in Women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1199. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1199. Zubieta J-K, W C, A R et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hsu DT, Sanford BJ, Meyers KK, Love TM, Hazlett KE, Walker SJ, et al. It still hurts: altered endogenous opioid activity in the brain during social rejection and acceptance in major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:193–200. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shotbolt P, Tziortzi AC, Searle GE, Colasanti A, van der Aart J, Abanades S, et al. Within-subject comparison of [(11)C]-(+)-PHNO and [(11)C]raclopride sensitivity to acute amphetamine challenge in healthy humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:127–36. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.