Abstract

Background

Obesity is a major challenge for people with schizophrenia.

Aim

We assessed whether STEPWISE, a theory-based, group structured lifestyle education programme could support weight reduction in people with schizophrenia.

Methods

In this randomised controlled trial, we recruited adults with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or first episode psychosis from ten mental health organisations in England. Participants were randomly allocated to the STEPWISE intervention or treatment as usual. The 12-month intervention comprised four 2.5 hour weekly group sessions, followed by two-weekly maintenance contact and group sessions at 4, 7 and 10 months. The primary outcome was weight change after 12 months. Key secondary outcomes included diet, physical activity, biomedical measures and patient related outcome measures. Cost-effectiveness was assessed and a mixed-methods process evaluation was included.

Results

Between 10 March 2015 and 31 March 2016, we recruited 414 people (intervention 208, usual care 206) with 341 (84.4%) participants completing the trial. At 12 months, weight reduction did not differ between groups (mean difference 0.0 Kg, 95% CI -1.6 to 1.7, p=0.963); physical activity, dietary intake and biochemical measures were unchanged. STEPWISE was well-received by participants and facilitators. The healthcare perspective incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was £246,921 per quality-adjusted life-year gained.

Conclusions

Participants were successfully recruited and retained, indicating a strong interest in weight interventions; however, the STEPWISE intervention was neither clinically nor cost-effective. Further research is needed to determine how to manage overweight and obesity in people with schizophrenia.

Declaration of Interest

None relevant to the trial; full disclosure is available in the paper.

Study registration

ISRCTN19447796.

Funding details

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Heath Technology Assessment (HTA) programme (HTA 12/28/05)

Introduction

People with schizophrenia die 10-20 years earlier than the general population, with approximately 75% of deaths resulting from physical illness (1). The two-fold increased prevalence of overweight and obesity contributes to this excess mortality (2). Some, but not all, studies suggest that dietary and physical activity interventions may reduce weight gain (3–7).

Many weight loss programmes involve one-to-one strategies to promote behaviour change but these are unlikely to be affordable in many healthcare settings (8). Group-based structured education offers an alternative approach (9), and has been adopted by the UK NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme (10). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that lifestyle interventions should be offered to people taking antipsychotics but there is insufficient evidence to inform how this should be commissioned (11).

We designed the STEPWISE group-based lifestyle structured education and then conducted a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate whether STEPWISE could lead to clinically relevant weight loss after a year in adults with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or first episode psychosis. Further objectives were to assess the impact on physical activity, diet, biomedical measures and quality of life, intervention fidelity, acceptability to participants and mental health services, and cost-effectiveness.

Methods

Study Design

STEPWISE was a two-arm, parallel group RCT comparing the STEPWISE intervention with treatment as usual (TAU). The study took place in ten English NHS Mental Health Trusts in urban and rural locations. The trial was approved by UK National Research Ethics Committee, Yorkshire & the Humber - South Yorkshire, (reference 14/YH/0019) and conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice. The trial protocol has been reported (12).

Participants

Researchers at each site worked with local mental health clinicians to identify potentially eligible patients from clinic lists and case notes. We used posters and leaflets to encourage self-referral. We recruited adults (≥18 years) with a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder (ICD-10 codes F20, F25) or first episode psychosis (defined as <3 years since presentation to mental health services). The Operational Criteria Checklist (OPCRIT+) was completed using case note review to assess whether the clinical diagnosis matched an objective measure of psychiatric illness.

All participants had been prescribed an antipsychotic for ≥1 month and were able and willing to participate in a group education programme. Participants had a body mass index (BMI) ≥25 Kg/m2 (≥23 Kg/m2 for South Asian and Chinese backgrounds) or expressed concern about their weight.

People were excluded if they had a physical illness that could seriously reduce their life expectancy or ability to participate, that would independently impact metabolic measures and weight, e.g. Cushing’s syndrome, or were currently pregnant or less than 6 months post-partum. High levels of psychiatric symptoms, as judged by the principal investigator, which could seriously affect participation and ability to put into practice the learning from the intervention sessions were a further exclusion criterion. People with significant alcohol or substance misuse, primary diagnosis of psychotic depression, mania or learning disability were excluded. People currently (or within the past three months) engaged in a weight management programme or unable to speak and read English were also excluded. Participants provided written informed consent before trial entry.

Randomisation and masking

The Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit generated a computerised randomisation list using permuted blocks of random sizes to allocate participants to either TAU plus the STEPWISE intervention or TAU alone in a 1:1 ratio, stratified by site and time since antipsychotic initiation (<3 months or ≥3 months). After randomisation, an unblinded researcher informed the participant and their general practitioner of the allocation. Research outcome assessors were blind to treatment allocation. Blind (or suspected) breaks were recorded. Due to the nature of the intervention, participants were not blinded.

Interventions

STEPWISE structured education lifestyle programme

We developed the STEPWISE intervention using the MRC framework for complex interventions (appendix 1). Following a systematic literature review, a team with expertise in obesity, lifestyle interventions, behaviour change, mental health, and people with schizophrenia designed the prototype intervention, which was piloted and amended in four iterative cycles.

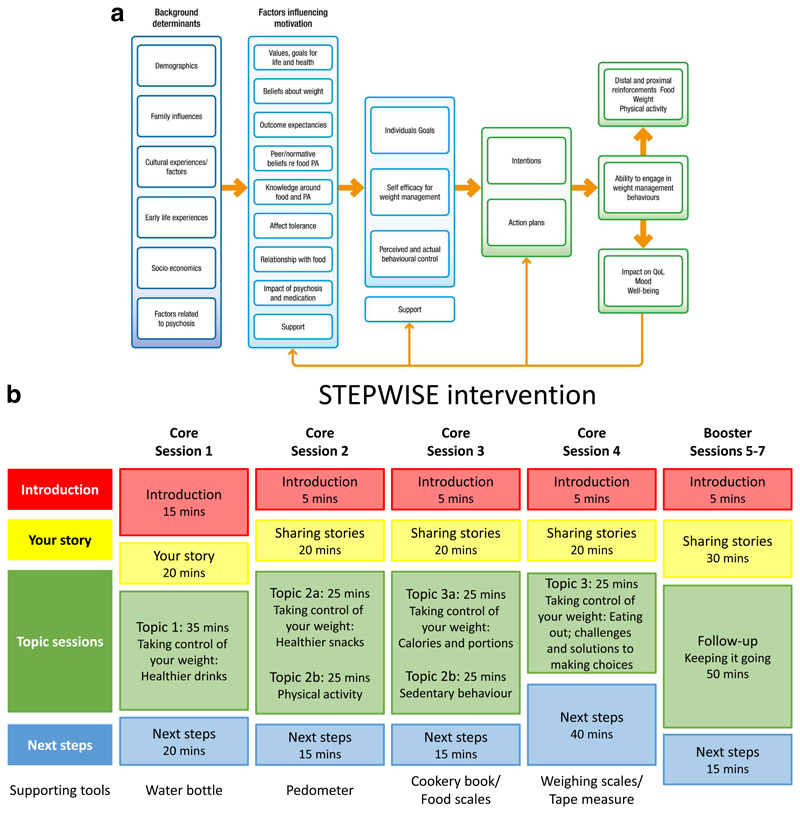

We considered three areas that are core to weight management interventions in people with schizophrenia when developing the theoretical framework that guided the intervention (Figure 1a):

behaviour change theory specifically with a focus on food and physical activity;

psychological processes underlying weight management;

challenges of living with psychosis and its impact on eating and weight.

Figure 1. The STEPWISE intervention.

Figure 1a. Theoretical Framework. The STEPWISE intervention was co-designed by a team with expertise in the development of obesity and lifestyle intervention programmes, mental healthcare professionals and researchers, and service users and refined during a four cycle pilot. It was underpinned by self-regulation and self-efficacy theories and the relapse prevention model. Figure 1b. Curriculum. The STEPWISE intervention comprised four 2.5 hour foundation group education sessions, designed to be delivered to small groups of 6-8 participants over four consecutive weekly followed by three 2.5 hour follow-up ‘booster’ sessions at 3-monthly intervals and fortnightly support, usually by telephone. The content was determined by the specific difficulties described by people with schizophrenia. The sessions incorporated adequate breaks. The educational style was non-judgmental and facilitative to allow the participants to discuss their beliefs about weight and explore own solutions. Strategies was employed to maintain engagement including telephone call reminders, provision of taxis to the venue, afternoon sessions with lunch provided, and use of incentives described as supporting tools.

Based on established psychological theories, appropriate behaviour change techniques were used to address problem behaviours.

STEPWISE took place over approximately 12 months. Groups of participants (median 6, range 3-11) attended a foundation course of four weekly 2.5-hour group sessions delivered by two trained facilitators (Figure 1b). This was followed by 1:1 support contact, mostly by telephone, lasting about ten minutes, approximately every two weeks for the remainder of the intervention period. A trained facilitator carried out the support contact to promote behaviour change and continued engagement. Further 2.5-hour group-based booster sessions took place at approximately 4, 7 and 10 months after randomisation giving a total intervention duration of ˜25.5 hours.

All sessions started at lunchtime with the provision of a healthy lunch. After an initial introduction, participants were invited to “share their story”. This provided the facilitators with feedback on what changes the person had made and what remained challenging. The facilitators used a non-judgemental style to encourage openness, problem solving and sharing successful strategies. Specific changes and challenges were recorded so that the participants could refer back to their individualised solutions.

The next part was entitled ‘Taking control of your weight’ to reinforce the focus of the intervention. Each session covered one or two aspects of how lifestyle changes could help the participants take control of their weight. Four topics covered diet while two focussed on physical activity. A facilitative approach, as opposed to a didactic teaching style, was used to enable participants to discuss their beliefs about weight and explore their own solutions.

The final section was devoted to action planning, when the participants developed their own individualised goals and solutions. As the participants departed, they were given supporting tools to reinforce the key messages of the session.

Each centre had 4-6 trained facilitators to maintain consistency across sessions and support contact. We recorded intervention attendance and level of support contact. We invited participants to complete an anonymous 6-question “session feedback” form at the end of each session (appendix 2a).

Control Arm

As no consistent lifestyle education programme was offered across sites (13), we provided printed advice on lifestyle and the risks associated with weight gain for all participants. We recorded whether participants attended other weight management or physical activity programmes outside the trial.

Outcomes

Trial assessments were undertaken at the participant’s home or Mental Health Organisation, after consent but before randomisation and at 3 and 12 months post randomisation (appendix 3).

The primary endpoint was weight change at 12 months after randomisation. A medical and psychiatric history, including smoking and current medication, was obtained. Height (baseline only), weight, waist circumference and blood pressure were measured (appendix 2b). Participants wore a wrist GENEActiv accelerometer for 7 days to assess physical activity (mean acceleration and mean time spent in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity) (appendix 2c).

Research staff helped participants complete the self-report questionnaires by reading the questions, checking understanding and providing available answer options. We assessed dietary intake with the Adapted Dietary Instrument for Nutrition Education questionnaire (14). We used questionnaires to assess patient-reported outcome measures, including quality of life (RAND SF-36 and EQ-5D-5L), health beliefs (adapted Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire), psychiatric symptoms (Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale) and depressive symptoms (9-item Patient Health Questionnaire).

Assessments of fasting glucose, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and lipid profile were made at baseline and 12 months post-randomisation.

Safety assessments

We monitored adverse events at 3 and 12 months. Expected serious adverse events included psychiatric hospitalisation, self-harm, suicide attempt and death from suicide. An independent Data Monitoring Committee and Trial Steering Committee oversaw the conduct and safety of the trial.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

We undertook an economic evaluation from a health and social care and societal perspective. Health and Social Care costs included the costs of medicines and NHS professionals in primary and community care and inpatient settings, and social care costs. Societal costs were calculated using police costs, productivity losses from lost education and employment and informal care costs. The intervention cost was based on staff time plus overheads and included training and supervision. The Client Service Receipt Inventory was used to record service use. Costs were calculated using appropriate unit cost information. Cost-effectiveness was assessed by combining cost with the primary outcome and quality adjusted life years (QALY) generated from the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire. We constructed incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) to demonstrate the cost per extra QALY gained and uncertainty around estimates was explored using cost-effectiveness planes and acceptability curves.

Process Evaluation

We undertook a process evaluation using a published framework and a logic model that focused on resources, activities and process outcomes (reach, delivery, fidelity and receipt of intervention) (15). Qualitative data were collected via semi-structured telephone interviews with service users (n=24), intervention facilitators (n=20) and intervention developers (n=7). The interviews were recorded and coded using NVivo (QSR International v11).

Intervention delivery fidelity was monitored by direct observation using two instruments (appendix 2d). The Core Facilitator Behavioural Observation Sheet assessed 35 behaviours in six domains. Participant–educator interaction was assessed using the DESMOND Observation Tool (16). Every 10 seconds, the coder recorded whether an educator or participant was currently talking. Silence, laughter or multiple conversations were classed as ‘miscellaneous’. This provided an objective indication of facilitator versus participant talktime.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on detecting a clinically meaningful difference of 4.5 Kg (˜5% reduction in body weight). This amount of weight loss is associated with improved lipid profile, glucose and blood pressure and potential reductions in cardiovascular disease (17). Based on previous UK data, we assumed a standard deviation (SD) of 10 Kg. 130 participants per arm (260 in total) were required to detect this weight difference assuming 95% power and two-sided significance level of 5%. Based on an average of seven participants per group, and intra-class correlation of 5% in the intervention arm, the sample size was inflated by a design effect of 1.3 in the intervention arm yielding revised sample sizes of 169 and 130 in the intervention and control arms, respectively. To maintain a 1:1 allocation, 158 participants per arm were required. We anticipated a dropout rate of 20% giving 198 participants per arm.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were by intention to treat. The primary objective was assessed by fitting a marginal generalised estimating equation model adjusted for baseline weight, site and years since antipsychotic initiation; the model incorporated an adjustment for potential clustering or correlation among outcomes of people treated together. A sensitivity analysis assessed the robustness of the findings, in particular, to missing data mechanisms (including missing not at random), exploring whether the intervention had the same effect among recently diagnosed participants compared with those with longer illness duration. Other continuous outcomes were analysed and reported as for the primary outcome. Analyses were conducted using the Stata 14.2 software (StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. TX; 2015).

Role of the funding source

The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or report writing. The corresponding author had full access to all study data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

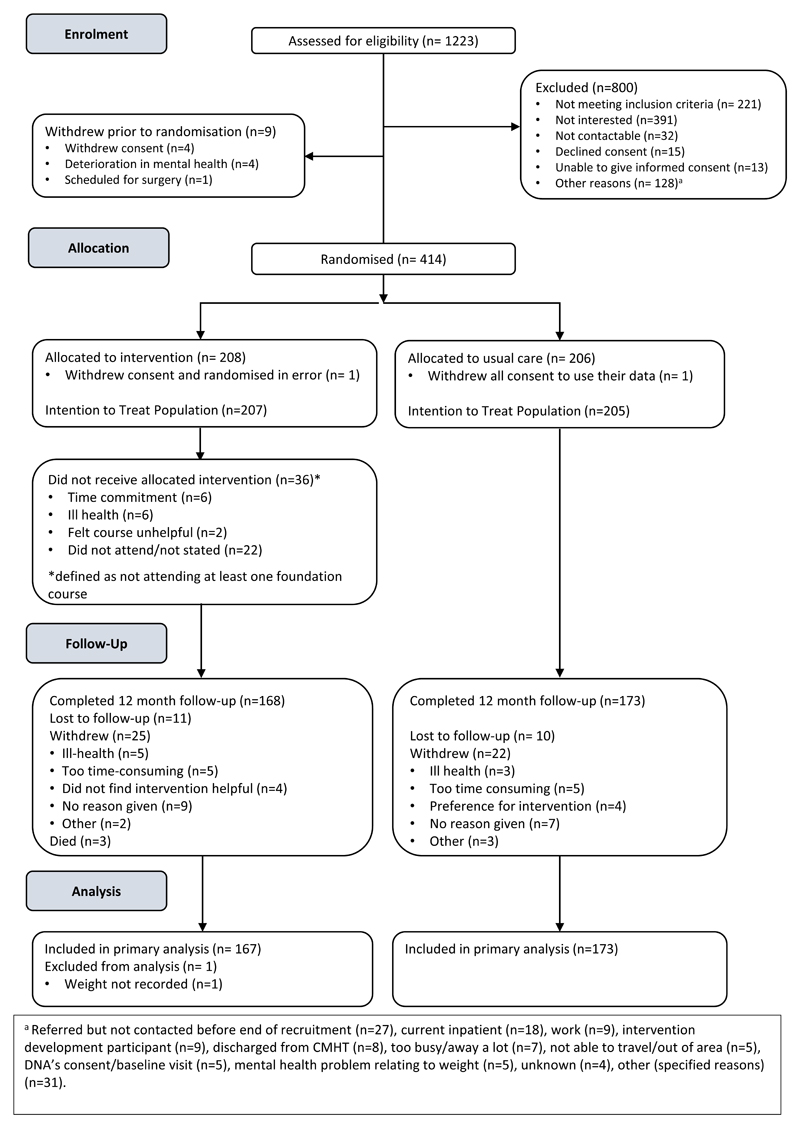

Between 10 March 2015 and 31 March 2016, we screened 1,253 patients of whom 414 enrolled (Figure 2). The trial closed on 31 March 2017 when the last 12-month follow-up was completed. The commonest reasons for exclusion at screening were ineligibility and lack of interest. Two participants withdrew consent prior to the study commencement and were not included in any analyses. Therefore, 412 participants (207 intervention, 205 control) were included in the final intention to treat analysis. 168 (81.2%) intervention and 173 (84.4%) control participants completed the study. 25 (12.1%) intervention and 22 (10.7%) control participants withdrew consent during the study. 11 (5.3%) intervention and 10 (4.9%) control participants were lost to follow-up. Three deaths occurred in the intervention arm.

Figure 2. STEPWISE trial CONSORT diagram.

At baseline, the groups were largely balanced (tables 1 and 2), but intervention participants were on average 3 Kg heavier at baseline, partially explained by the higher proportion of men in the intervention arm (55.6% vs. 46.3%). 7 control and 3 intervention participants had a BMI <25 Kg/m2. The OPCRIT+ concurred with the clinical diagnosis (appendix 4.1). Participants reported mild-to-moderate psychiatric symptoms and took a range of antipsychotics (table 1). 24 (14.3%) intervention participants and 29 (16.7%) control participants changed antipsychotic during the trial.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics. Data are number (%) or mean (SD). Daily doses are median (IQR) in mg. Where long acting injectable medications have been used, the total dose has been divided by the dosing interval. Participants may have been taking more than one antipsychotic

| Intervention (N=207) | Control (N=205) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 40.0 (11.3) | 40.1 (11.5) | ||

| Male | 115 (55.6%) | 95 (46.3%) | ||

| Female | 92 (44.4%) | 110 (53.7%) | ||

| Schizophrenia diagnosis type | ||||

| ICD-10: F20 | 145 (70.0%) | 138 (67.3%) | ||

| ICD-10: F25 | 30 (14.5%) | 36 (17.6%) | ||

| First episode psychosis | 32 (15.5%) | 31 (15.1%) | ||

| Time since starting antipsychotic medication (years) | ||||

| <1 year | 12 (5.8%) | 12 (5.9%) | ||

| 1-2 years | 11 (5.3%) | 20 (9.8%) | ||

| 2-5 years | 28 (13.5%) | 19 (9.3%) | ||

| 5-10 years | 28 (13.5%) | 33 (16.1%) | ||

| 10-20 years | 71 (34.3%) | 69 (33.7%) | ||

| 20 or more years | 57 (27.5%) | 52 (25.4%) | ||

| Antipsychotic medication | Daily dose | Daily dose | ||

| Haloperidol (oral) | 7 (3.4%) | 5 (5, 10) | 3 (1.5%) | 5 (1, 9) |

| Amisulpride (oral) | 21 (10.1%) | 400 (400, 800) | 16 (7.8%) | 175 (100, 375) |

| Aripiprazole (oral) | 37 (17.9%) | 10 (10, 15) | 28 (13.7%) | 10 (5, 15) |

| Aripiprazole (long acting injection) | 3 (1.4%) | 14.3 (14.3, 14.3) | 6 (2.9%) | 14.3 (14.3, 14.3) |

| Clozapine (oral) | 89 (43.0%) | 300 (250, 450) | 81 (39.5%) | 350 (250, 475) |

| Olanzapine (oral) | 31 (15.0%) | 10 (5, 15) | 31 (15.1%) | 15 (10, 20) |

| Quetiapine (oral) | 28 (13.5%) | 350 (175, 600) | 24 (11.7%) | 250 (100, 425) |

| Risperidone (oral) | 6 (2.9%) | 4 (4,7) | 16 (7.8%) | 4 (4, 8) |

| Risperidone (long acting injection) | 4 (1.9%) | 3.1 (2.7, 3.6) | 5 (2.4%) | 2.7 (1.8, 3.6) |

| Flupentixol (injection) | 8 (3.9%) | 3.6 (3.2, 5.0) | 11 (5.4%) | 7.1 (2.9, 14.3) |

| Zuclopenthixol (oral) | 2 (1.0%) | 19 (10, 28) | 6 (2.9%) | 7 (6, 20) |

| Zuclopenthixol (long acting injection) | 8 (3.9%) | 23.2 (11.9, 32.1) | 15 (7.3%) | 14.3 (12.1, 35.7) |

| Paliperidone (long acting injection) | 7 (3.4%) | 5.4 (2.7, 5.4) | 8 (3.9%) | 3.6 (2.2, 4.9) |

| Other antipsychotic | 19 (9.2%) | 9 (4.4%) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White European | 179 (86.5%) | 170 (82.9%) | ||

| Asian | 9 (4.3%) | 7 (3.4%) | ||

| Black | 12 (5.8%) | 19 (9.3%) | ||

| Mixed | 4 (1.9%) | 7 (3.4%) | ||

| Other | 3 (1.4%) | 2 (1.0%) | ||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Ex-smoker | 55 (26.6%) | 52 (25.4%) | ||

| Never smoked | 54 (26.1%) | 45 (22.0%) | ||

| Current smoker | 98 (47.3%) | 108 (52.7%) | ||

| Abnormal renal function | 60 (29.0%) | 58 (28.3%) | ||

| Hepatic disease | 5 (2.4%) | 7 (3.4%) | ||

| Diabetes | 35 (16.9%) | 25 (12.2%) | ||

| Hypertension | 21 (10.1%) | 17 (8.3%) | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 7 (3.4%) | 12 (5.9%) |

Table 2. Outcome measures at baseline, 3-month and 12-month follow-up visits Baseline characteristics. Data are number (%) or mean (SD) or odds ratio (95% confidence intervals. Statistical analysis is on the basis of intention to treat.

| Baseline | 3-month | 12-month | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N=207) | Control (N=205) | Intervention (N=178) | Control (N=180) | Difference between Intervention and Control | Intervention (N=167) | Control (N=173) | Difference between Intervention and Control | |

| Physical measures | ||||||||

| Weight (Kg) | 105.2 (22.2) | 102.1 (22.1) | 104.7 (21.5) | 103.1 (23.5) | -0.55 (-1.44, 0.35) | 104.1 (21.1) | 101.3 (23.7) | 0.04 (-1.58, 1.66) |

| % weight change | -0.2 (4.4) | 0.4 (4.7) | -0.4% (-1.3%, 0.5%) | -0.5 (7.9) | -0.5 (8.3) | 0.0% (-1.6%, 1.7%) | ||

| Maintained or lost weight | 93 (52.2%) | 80 (44.2%) | 1.35 (0.88, 2.05)† | 98 (58.3%) | 88 (50.9%) | 1.35 (0.85, 2.14) † | ||

| BMI (Kg/m2)♦ | 36.1 (7.2) | 35.3 (7.2) | 35.8 (7.1) | 35.5 (7.4) | -0.16 (-0.48, 0.15) | 35.6 (7.2) | 34.8 (7.3) | 0.05 (-0.51, 0.61) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 117.8 (15.6) | 116.1 (17.4) | 116.8 (15.2) | 115.4 (17.0) | 0.79 (-0.64, 2.22) | 116.4 (16.1) | 114.0 (17.7) | 1.22 (-0.74, 3.20) |

| Blood pressure | 126 ± 16/82 ± 11 | 124 ± 17/82 ± 12 | 127 ± 16 / 82 ±11 | 123 ±16 / 81 ±12 | 2.4 (0.2, 4.7) / 0.4 (-1.5, 2.4) | 125 ± 15 / 82 ±10 | 122 ±16 /81 ±11 | 1.7 (-1.1, 4.5) 1.1 (-0.7, 3.0) |

| Biochemical measures | ||||||||

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 42 (13) | 40 (11) | 43 (15) | 41 (14) | 0.2 (-1.4, 1.9) | |||

| Fasting Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.9 (2.2) | 5.8 (2.3) | 6.4 (3.0) | 6.0 (2.8) | 0.2 (-0.2, 0.7) | |||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.0 (1.2) | 5.1 (1.2) | 4.9 (1.2) | 5.1 (1.1) | -0.2 (-0.4, 0.1) | |||

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.3) | 0.0 (-0.1, 0.1) | |||

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 2.5 (2.0) | 2.2 (1.7) | 2.4 (1.4) | 2.4 (2.2) | -0.2 (-0.6, 0.1) | |||

| Psychosocial measures | ||||||||

| RAND (general health) | 45.0 (20.3) | 44.8 (20.7) | 48.0 (21.8) | 46.8 (20.3) | -0.3 (-3.4,2.8) | 49.8 (23.1) | 46.8 (21.4) | 2.2 (-1.3,5.6) |

| EQ5D | 0.793 (0.201) | 0.783 (0.187) | 0.815 (0.165) | 0.785 (0.214) | 0.02 (-0.02, 0.054) | 0.793 (0.237) | 0.793 (0.239) | -0.02 (-0.06, 0.03) |

| B-IPQ | 5.5 (1.5) | 5.5 (1.7) | 5.0 (1.7) | 5.3 (1.7) | 5.0 (1.9) | 5.0 (1.7) | ||

| BPRS | 30.9 (8.8) | 31.5 (9.4) | 30.3 (9.0) | 30.4 (9.4) | 29.1 (9.7) | 28.3 (9.5) | ||

| PHQ9 | 10.6 (6.3) | 11.0 (6.8) | 10.3 (6.3) | 10.1 (7.1) | 9.9 (7.0) | 9.6 (6.6) | ||

| Physical Activity | ||||||||

| MVPA* (All days) | 13.3 (16.8) | 11.0 (13.1) | 13.3 (20.4) | 8.8 (12.6) | 2.0 (-0.9, 4.9) | 15.4 (21.7) | 11.8 (19.3) | 1.5 (-2.5, 5.5) |

| MVPA* (weekends) | 9.6 (16.6) | 9.6 (14.8) | 11.3 (24.9) | 7.4 (12.4) | 5.6 (2.0, 9.3) | 11.9 (22.1) | 9.5 (19.2) | 2.2 (-1.8, 6.2) |

| MVPA* (weekdays) | 14.4 (18.5) | 11.6 (14.8) | 13.8 (20.3) | 9.5 (14.3) | 0.9 (-2.0, 3.8) | 16.6 (24.5) | 12.6 (20.1) | 1.0 (-3.9, 6.0) |

| Mean Acceleration (All days) | 21.3 (7.9) | 20.8 (7.4) | 21.7 (9.0) | 19.8 (7.1) | -0.4 (-1.5, 0.8) | 22.4 (8.2) | 20.5 (8.5) | 0.2 (-1.4, 1.7) |

| Mean Acceleration (Weekends) | 19.6 (8.0) | 19.8 (8.3) | 20.4 (9.6) | 18.7 (6.9) | 1.0 (-0.3, 2.4) | 20.9 (8.6) | 19.4 (8.8) | 0.3 (-1.5, 2.1) |

| Mean Acceleration (Weekdays) | 22.1 (8.3) | 21.1 (7.1) | 22.1 (9.2) | 20.2 (7.5) | -0.7 (-2.0, 0.6) | 23.0 (8.5) | 20.9 (8.6) | 0.0 (-1.6, 1.6) |

Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

10 participants had BMI below 25 Kg/m2 at baseline (ranging from 19.5-24.9 Kg/m2); none of these was from a South Asian or Chinese background.

MVPA (moderate-to-vigour physical activity) is assessed in bouts >10 minutes in duration. Baseline accelerometry data were obtained from 85% of participants of whom 76% provided valid data (≥4/7 days). Comparative data were available for 54% and 52% of participants at 3 and 12 months. B-IPQ: Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire; BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; PHQ9: 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

Intervention Uptake

Participants commenced the STEPWISE intervention a median 15 days (range 1-101 days) after randomisation. Participants attended a mean of 2.7 foundation and 1.4 booster sessions. 111 (53.6%) participants attended ≥3 foundation sessions and ≥1 booster session, of whom 47 (22.7%) participants attended all foundation and booster sessions. 36 (17.4%) participants attended no sessions. The mean group size at randomisation was 6.3 (median 6) but the mean number attending ranged from 4.0 – 4.4 (median 4) during the foundation course and dropped to 2.7 – 3.0 (median 3) during booster sessions (appendix 4.2). 169 (81.6%) participants had one or more support contacts, mostly by telephone (80.7% participants, 2,434 contacts), mail/postcard (49.3%, 555 contacts) or both (48.3%). Fewer participants were contacted electronically (11.6%, 88 contacts) or face-to-face (32.9%, 141 contacts). 25 (7.5%) participants (17 intervention and 8 control) reported attending weight loss programmes outside the trial (appendix 4.3).

Outcome measures

The primary comparison of weight change at 12 months was almost identical between arms, with a mean reduction in weight of 0.47 Kg in intervention participants and 0.51 Kg in control participants (difference= 0.0 Kg, 95% CI -1.6 to 1.7, p=0.963) (Table 2, appendix figure 4.1). There was no difference in percentage weight loss or percentage of participants maintaining or losing weight.

Weight loss was modestly associated with age, with weight reduction increasing by 0.8 Kg per 10 additional years (95% CI 0.0 to 1.5 Kg, p=0.042). Participants with schizoaffective disorder had greater mean weight loss (-2.7 Kg) than those with first episode psychosis (-0.3 Kg) or schizophrenia (+0.01 Kg; p=0.023). There was no association between treatment effect and sex, baseline mental health, BMI, severity of psychiatric illness, duration and change of antipsychotic treatment, or attendance at an external weight loss programme. There was no association between total contact time and weight loss.

The baseline self-reported diet indicated a high consumption of refined sugar from sugary drinks and low fibre (appendix 4.4). Although there was some evidence that alcohol intake fell in intervention participants, no other dietary component changed during the trial. Smoking status did not change (appendix 4.5).

Both groups had similarly low physical activity levels at baseline (Table 2). After 3-months, weekend moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was significantly higher in intervention participants, but this difference had disappeared by 12 months. No other differences were seen in physical activity. Self-reported patient quality of life, obesity illness perception and psychiatric symptoms were also similar between groups at both 3- and 12- months (Table 2; appendix 4.6-7). The lack of objective changes in diet and lifestyle in the intervention group contrasted with self-reported changes during the “Sharing Stories” part of the sessions.

At 3 months, outcome assessors were unblinded (or suspected unblinding) at 44 (12%) of visits (intervention: 34/178, 19%; control: 10/186, 5%). At 12 months, unblinding was recorded for 35 (10%) of visits (intervention: 31/168, 18%; control: 4/174, 2%).

The 703 anonymous participant session feedback forms showed 87.2% of respondents indicated the session met their needs (appendix 4.8a). Forms were received from all 10 sites with the number ranging 26 to 116 (appendix 4.8b). Mean weight change did not correlate with mean centre feedback scores, at 3 or 12 months (Spearmans rho = -0.20, p = 0.476 and Spearmans rho = 0.042, p = 0.454 respectively).

Adverse events were similar between groups, except three deaths occurred in the intervention group; none were considered a result of the intervention (appendix 4.9).

Cost-effectiveness analysis

The two groups had similar EQ-5D-5L scores (Health Economics appendix). The intervention produced 0.0035 more QALYs. The mean total health and social care costs were £5,255 for STEPWISE participants and £4,453 for control participants. The mean total societal costs were £11,332 in STEPWISE participants and £10,305 in control participants. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio from the healthcare perspective is £246,921 and £367,543 from the societal perspective.

Process evaluation

Facilitator and participant courses were popular, and materials were adequately resourced, although doubts were expressed about financial sustainability. Professionals were generally motivated but expressed the concern that in some trusts human resource and leadership support were inadequate.

Fidelity assessment of intervention delivery showed overall mean ± SD percentage facilitator talk time was 47.6 ± 12.3% (appendix 4.10). “Positive” (more facilitative) behaviours were observed for 54.1 ± 15.0% of the time. Conversely, “negative” (more didactic) behaviours were observed for 23.8 ± 15.4% of the time. Problems with fidelity included facilitators giving insufficient time for answering questions or completing tasks as well as providing rather than eliciting solutions from participants. Whilst the session structure provided dedicated space for participants to share their behavioural change successes and challenges, the intervention incorporated no objective assessment of whether participants had understood and were acting on programme content. There was difficulty delivering telephone support contacts, commonly because participants did not answer.

Discussion

The STEPWISE trial successfully recruited and retained participants; however, the intervention was neither clinically nor cost-effective over the 12-month intervention period. Both groups lost ˜0.5 Kg but weight change did not differ between groups. There was no sustained behaviour change in diet and physical activity needed to promote weight loss.

These results were unexpected as previous studies had indicated that non-pharmacological interventions could support weight reduction (3); however, most studies had fewer than 100 participants, were of short duration, at moderate risk of bias and demonstrated substantial heterogeneity of effect size (11). NICE concluded that lifestyle interventions could reduce body weight in the short-term but effects beyond six months were unknown (11).

Given our findings, we examined why the intervention did not work and the implications for future research and clinical practice. In terms of trial conduct, recruitment exceeded our target while satisfactory retention and data completeness for the primary outcome ensured the trial was adequately powered. The 1-year follow-up allowed a long-term perspective while assessor blinding reduced the risk of bias.

STEPWISE was robustly developed in collaboration with people with schizophrenia and met UK Department of Health guidelines for structured education (18). The intervention was pragmatic, theory-based, feasible and appeared acceptable to both people with schizophrenia and mental healthcare professionals (19). Direct observation of sessions, the gold standard method for investigating fidelity, demonstrated that, despite the higher than expected turnover of facilitators, the intervention was delivered as planned and tailored appropriately.

Although our findings are at odds with the effects of short term interventions, other long-term studies have failed to demonstrate a benefit of lifestyle intervention. A recent meta-analysis found significant weight loss in only two of six studies with interventions lasting longer than a year (7). The Danish CHANGE study, which randomised 428 people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and abdominal obesity to 12 months of intensive lifestyle coaching plus care coordination plus usual care, or care coordination and usual care, or usual care alone, found no effect on body weight or waist circumference with either intervention (6). Two other recent UK lifestyle intervention trials have also not met their primary outcome (20, 21).

It is instructive to compare the results of STEPWISE and CHANGE with two large US trials where weight loss was achieved. In the ACHIEVE study, the intervention group lost on average 3.2kg over 18 months (4) while in STRIDE, intervention participants lost 4.4 Kg more than control participants from baseline to 6 months but this difference reduced to 2.6 Kg at 1 year (5). Both ACHIEVE and STRIDE interventions were considerably more intensive than STEPWISE. ACHIEVE combined group weight-management sessions (weekly in the first 6 months then monthly), monthly individual visits and thrice weekly group activity classes, while STRIDE study involved a 6-monthly weekly group intervention followed by six monthly maintenance sessions.

The maximum face-to-face contact time in STEPWISE (17.5 hours) is similar to that recommended by the NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme and it is debatable whether a more intensive intervention would be feasible within many healthcare settings. Even accounting for the lower cost of delivering STEPWISE in real world clinical practice, a more intensive programme would likely be unaffordable, a concern raised by several facilitators. In STEPWISE, despite the successful pilot study and use of motivational techniques to engage participants, intervention uptake was challenging, as judged by the number of sessions attended, although the level of engagement was similar to other group based education programmes (22, 23).

Intervention intensity, however, does not fully explain why STEPWISE was unsuccessful as the unsuccessful CHANGE included weekly 1-hour sessions for a year. Both STEPWISE and CHANGE recruited people with schizophrenia; by contrast, 41.9% of ACHIEVE participants and 71% of STRIDE participants had mental illness other than schizophrenia spectrum disorders, for whom behaviour change may be easier to achieve. Whether STEPWISE would have been more successful for those with other psychotic illnesses, such as bipolar disorder, is unknown.

By design, we included a broad representation of people with schizophrenia and first episode psychosis, although those with high levels of psychiatric symptoms were excluded. The participants had a spectrum of BMI from normal weight to morbid obesity. Most had a long history of established psychiatric disorder and around 40% were taking the second-line antipsychotic, clozapine. It is possible that the intervention could have been more effective during early psychosis, when weight gain is most rapid (2). Although we planned to include individuals shortly after the diagnosis of first episode psychosis, few participants had received treatment for less than 3 months, partly because of delays inherent in recruiting to a group intervention.

To achieve meaningful weight loss, sustained behaviour change is needed. At baseline, participants ate an unhealthy diet and were physically inactive. Despite an opportunity to make a change, the intervention had little impact. One limitation of the intervention was the lack of objective feedback about participants’ progress to facilitators. The process evaluation indicated that facilitators wanted more information about participant weight change and nutritional and exercise plans to check understanding of session content and monitor dietary or physical activity changes against action plans.

Notwithstanding the negative results, the trial has important findings. Despite concerns about undertaking trials in this population, we successfully delivered the largest trial in this area with a 12-month follow-up across a diverse group of community mental health teams. We achieved our recruitment target three months ahead of schedule and maintained participants throughout the year-long trial. The trial also highlighted patient and healthcare professional demand for weight-management programmes within mental health settings and, in response, several trusts increased their physical health monitoring and engagement with weight management. Participants also valued sharing experiences with other people with schizophrenia with similar weight problems.

The challenge of managing obesity and weight gain in people with schizophrenia remains and other approaches are needed. STEPWISE focussed on lifestyle modification rather than the breadth of contributors to weight gain and obesity. Antipsychotics are associated with weight gain while psychosis and psychological factors can impede weight loss behaviours. Broader approaches that combine individually tailored lifestyle modification with psychological interventions for mental health, adjustment of antipsychotic treatment or co-prescription with drugs, such as metformin, may be needed (24).

While it is clear that lifestyle change is needed for people with schizophrenia, STEPWISE has shown how difficult this is to achieve. NICE guidance currently recommends “people with psychosis or schizophrenia, especially those taking antipsychotics, should be offered a combined healthy eating and physical activity programme by their mental healthcare provider (11).” Before these lifestyle interventions are commissioned across the NHS, it is vital that further research is undertaken to address how best to support weight management.

Appendix

Relevance statement.

International guidelines recommend that people taking antipsychotics should be offered lifestyle interventions to address weight gain. Many mental health services struggle to implement this, because of insufficient evidence to inform commissioning. Using robust methodology, we developed STEPWISE, a theoretically informed, group-based structured education intervention to support weight loss in people with schizophrenia. We conducted the largest randomised controlled study of a lifestyle intervention for people with schizophrenia. STEPWISE was not effective in reducing weight. Before lifestyle interventions are commissioned across the NHS, it is vital that further research is undertaken to address how to support weight management in this population.

Acknowledgments

We thank the service users who participated in this study and our funders for making this research possible. We gratefully acknowledge the hard work, support, and advice from Nicholas Bell, Director of Research and Development (Sheffield Health and Social Care NHS Foundation Trust) as Research Sponsor; research nurses, clinical studies officers and trial facilitators in the ten participating NHS trusts for participant screening and data collection, and delivering the intervention; trial support officer and data managers at Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit. We acknowledge Jonathan Mitchell (Sheffield Health and Social Care NHS Foundation Trust) as PI of the intervention development study. We acknowledge the following from University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust; Cheryl Taylor who trained facilitators, delivered intervention sessions in the study pilot and conducted observations as part of intervention fidelity; Sue Cradock who developed and conducted the intervention fidelity observation framework; and Michelle Hadjiconstantinou who conducted qualitative interviews and focus groups as part of the intervention development pilot and conducted observations as part of intervention fidelity. We acknowledge advice and oversight from independent members of the Trial Steering Committee: Charles Fox (Chair), Peter Tyrer, Irene Stratton, Debbie Hicks and service user representatives and, independent Data Monitoring Committee: Irene Cormac (Chair), John Wilding and Merryn Voysey. We acknowledge the National Institute of Health Research Clinical Research Network (NIHR CRN) for supporting recruitment to the study, and Tees Esk & Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust who supported the study from 1 October 2015.

This project was funded by the Health Technology Assessment Programme (project number 12/28/05) and will be published in full in the Health Technology Assessment journal series. Further information available online. This report presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Medical Research Council (MRC), Clinical Commissioning Facility (CCF), the NIHR Evaluations, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC), the Health Technology Assessment programme, or the Department of Health. The views and opinions expressed by the interviewees in this publication are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, CCF, NETSCC, the Health Technology Assessment programme or the Department of Health.

The STEPWISE Research Group

University of Southampton: Richard I G Holt (Chief Investigator), Katharine Barnard. University of Sheffield: Rebecca Gossage-Worrall (Research Associate) Mike Bradburn (Senior Statistician), Daniel Hind (CTRU Assistant Director), David Saxon (statistician), Lizzie Swaby (Research Assistant). Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust: Paul French (principal investigator), John Pendlebury (Community Psychiatric Nurse – retired). Leeds and York Partnership Trust: Stephen Wright (PI). Sheffield Health and Social Care NHS Foundation Trust: Glenn Waller (PI). Kings College London: Paul McCrone (Health Economist), Tiyi Morris (Research Assistant). University of Leicester: Charlotte Edwardson (Associate Professor in Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Health), Kamlesh Khunti (Professor of Primary Care Diabetes and Vascular Medicine), Melanie Davies (Professor of Diabetes Medicine). University Hospitals of Leicester: Marian Carey (Director: Structured Education Research Portfolio), Yvonne Doherty (Consultant Clinical Psychologist), Alison Northern (Project Manager), Janette Barnett (Diabetic Specialist Nurse). Cornwall NHS Trust: Richard Laugharne (PI). Devon Partnership Trust: Chris Dickens (PI). Somerset Partnership Trust: Chris Dickens (PI). Sussex Partnership: Kathryn Greenwood (PI). South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust: Fiona Gaughran (co-PI), Sridevi Kalidindi (co-PI). Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust: Shanaya Rathod (PI). Bradford District Care Trust: Najma Siddiqi (PI). Angela Etherington (independent service user consultant), David Shiers (carer collaborator).

Footnotes

Contributors

RIGH was the chief investigator who oversaw all study conduct; helped develop all study materials including the trial protocol; participated in data analysis and interpretation of the results; and drafted and revised the manuscript. DH provided oversight to the trial design and protocol, conducted qualitative data collection (developers), analysis and interpretation of qualitative results and revised the manuscript. RGW conducted qualitative data collection (participants, facilitators), analysis and interpretation of qualitative results; and, was the Trial Manager who coordinated study activities, developed study materials including the protocol and amendments, set up and trained sites, facilitated recruitment and collection of data, and revised the manuscript. MB was the trial statistician, providing advice and input to all statistical issues, completed final data analysis and interpretation of results; and, revised the manuscript.

DSh and AE are carer and service user (respectively) collaborators who contributed to the trial design and conduct including protocol, study documents and interpretation of qualitative results, and revised the manuscript.

DS completed data analysis and interpretation of results, and revised the manuscript. PM contributed to the design of the study, was responsible for the economic evaluation, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. TM conducted health economic data analysis, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. CE oversaw collection, analysis and interpretation of the accelerometry data and revised the manuscript. CD, PF, FG, KG, SR, RL, NS, GW, SW were the principal investigators (PI) and assisted with development of the protocol and other study materials; and with SK (PI) supervised recruitment, assessed eligibility, and supported data collection at site, interpreted results, and revised the manuscript. JP contributed to the tailoring of the intervention, referred service users and supported participant recruitment at Greater Manchester site. MC provided oversight and management of the development of the STEPWISE intervention, contributed to the literature search, interpretation of the intervention fidelity data, and critically reviewed the manuscript. YD was part of the team that developed the intervention, wrote and provided the training for the facilitators that delivered the intervention, and that completed the treatment fidelity. KB contributed to the design and interpretation of the qualitative aspects of the study. MD helped develop the trial protocol, participated in interpretation of the results and critically revised the manuscript. KK contributed to concept, design, intervention development and revised the manuscript. LS supported amendments to study documents, data management and conducted site monitoring; and, data collection and with the STEPWISE Research Group analysis for the usual care survey. AN was project manager for the intervention development study and conducted observations as part of intervention fidelity and revised the manuscript. JB was a key member of the development team and led delivery of the intervention development study, was a senior member of the training team, provided mentorship to facilitators, and conducted intervention fidelity observations.

Declaration of interests

RIGH received fees for lecturing, consultancy work and attendance at conferences from the following: Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Lundbeck, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Otsuka, Sanofi, Sunovion, Takeda, MSD. MC reports personal fees from Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Servier, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Takeda Pharmaceuticals International Inc.; and, grants from Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen. KK has received fees for consultancy and speaker for Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Lilly, Servier and Merck Sharp & Dohme. He has received grants in support of investigator and investigator initiated trials from Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Lilly, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim and Merck Sharp & Dohme. KK has received funds for research, honoraria for speaking at meetings and has served on advisory boards for Lilly, Sanofi-Aventis, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Novo Nordisk. DSh is expert advisor to the NICE centre for guidelines; Board member of the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH); Clinical Advisor (paid consultancy basis) to National Clinical Audit of Psychosis (NCAP); views are personal and not those of NICE, NCCMH or NCAP. JP received personal fees for involvement in the study from NIHR Grant. MC and YD report grants from NIHR HTA, during the conduct of the study; and, The Leicester Diabetes Centre, an organisation (employer) jointly hosted by an NHS Hospital Trust and the University of Leicester and who is holder (through the University of Leicester) of the copyright of the STEPWISE programme and of the DESMOND suite of programmes, training and intervention fidelity framework which were used in this study. SR has received honorarium from Lundbeck for lecturing. FG reports personal fees from Otsuka and Lundbeck, personal fees and non-financial support from Sunovion, outside the submitted work; and has a family member with professional links to Lilly and GSK, including shares. FG is in part funded by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research & Care Funding scheme, by the Maudsley Charity and by the Stanley Medical Research Institute and is supported by the by the Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London.

References

- 1.Chang CK, Hayes RD, Perera G, Broadbent MT, Fernandes AC, Lee WE, et al. Life expectancy at birth for people with serious mental illness and other major disorders from a secondary mental health care case register in London. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holt RI, Peveler RC. Obesity, serious mental illness and antipsychotic drugs. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11(7):665–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caemmerer J, Correll CU, Maayan L. Acute and maintenance effects of non-pharmacologic interventions for antipsychotic associated weight gain and metabolic abnormalities: a meta-analytic comparison of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Res. 2012;140(1–3):159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daumit GL, Dickerson FB, Wang NY, Dalcin A, Jerome GJ, Anderson CA, et al. A behavioral weight-loss intervention in persons with serious mental illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1594–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green CA, Yarborough BJ, Leo MC, Yarborough MT, Stumbo SP, Janoff SL, et al. The STRIDE weight loss and lifestyle intervention for individuals taking antipsychotic medications: a randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(1):71–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Speyer H, Christian Brix Norgaard H, Birk M, Karlsen M, Storch Jakobsen A, Pedersen K, et al. The CHANGE trial: no superiority of lifestyle coaching plus care coordination plus treatment as usual compared to treatment as usual alone in reducing risk of cardiovascular disease in adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and abdominal obesity. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):155–65. doi: 10.1002/wps.20318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naslund JA, Whiteman KL, McHugo GJ, Aschbrenner KA, Marsch LA, Bartels SJ. Lifestyle interventions for weight loss among overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;47:83–102. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yates T, Davies M, Khunti K. Preventing type 2 diabetes: can we make the evidence work? Postgrad Med J. 2009;85(1007):475–80. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.076166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NICE. National Institute for, Health Clinical, Excellence. Preventing type 2 diabetes: risk identification and interventions for individuals at high risk. PHG38; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.NHS England. NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme (NHS DPP) [last accessed 31/03/18]; https://www.england.nhs.uk/diabetes/diabetes-prevention/

- 11.NICE. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. CG178. The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gossage-Worrall R, Holt RI, Barnard K, Carey M, Davies MJ, Dickens C, et al. STEPWISE - STructured lifestyle Education for People WIth SchizophrEnia: a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17(1):475. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1572-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swaby L, Hind D, Gossage-Worrall R, Shiers D, Mitchell J, Holt RIG. Adherence to NICE guidance on lifestyle advice for people with schizophrenia: a survey. BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(3):137–44. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.116.054304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roe L, Strong C, Whiteside C, Neil A, Mant D. Dietary intervention in primary care: validity of the DINE method for diet assessment. Fam Pract. 1994;11(4):375–81. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linnan L, Steckler A. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research: an overview. In: Linnan L, Steckler A, editors. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research. Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skinner TC, Carey ME, Cradock S, Dallosso HM, Daly H, Davies MJ, et al. 'Educator talk' and patient change: some insights from the DESMOND (Diabetes Education and Self Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed) randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2008;25(9):1117–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Douketis JD, Macie C, Thabane L, Williamson DF. Systematic review of long-term weight loss studies in obese adults: clinical significance and applicability to clinical practice. Int J Obes(Lond) 2005;29(10):1153–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health, Diabetes UK. Structured patient education in diabetes: Report from the Patient Education Working Group 1-69. DH publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies MJ, Heller S, Skinner TC, Campbell MJ, Carey ME, Cradock S, et al. Effectiveness of the diabetes education and self management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND) programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;336(7642):491–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39474.922025.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heslin M, Patel A, Stahl D, Gardner-Sood P, Mushore M, Smith S, et al. Randomised controlled trial to improve health and reduce substance use in established psychosis (IMPaCT): cost-effectiveness of integrated psychosocial health promotion. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):407. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1570-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osborn D, Burton A, Hunter R, Marston L, Atkins L, Barnes T, et al. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of an intervention for reducing cholesterol and cardiovascular risk for people with severe mental illness in English primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies MJ, Gray LJ, Troughton J, Gray A, Tuomilehto J, Farooqi A, et al. A community based primary prevention programme for type 2 diabetes integrating identification and lifestyle intervention for prevention: the Let's Prevent Diabetes cluster randomised controlled trial. Prev Med. 2016;84:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yates T, Edwardson CL, Henson J, Gray LJ, Ashra NB, Troughton J, et al. Walking Away from Type 2 diabetes: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2017;34(5):698–707. doi: 10.1111/dme.13254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper SJ, Reynolds GP, With expert c-a. Barnes T, England E, Haddad PM, et al. BAP guidelines on the management of weight gain, metabolic disturbances and cardiovascular risk associated with psychosis and antipsychotic drug treatment. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(8):717–48. doi: 10.1177/0269881116645254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.