Abstract

Objective

To systematically review and meta-analyse how physical activity (PA) changes from adolescence to early adulthood (13-30y).

Data Sources

Seven electronic databases were searched: Medline, Embase, PsycInfo, SCOPUS, ASSIA, Sportdiscus, Web of Science.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

English-language, longitudinal studies (from 01/1980 to 01/2017) assessing PA ≥twice, with the mean age of ≥one measurement in adolescence (13-19y) and ≥one in young adulthood (16-30y) were included. Where possible, data were converted to moderate-to-vigorous activity (MVPA) min/day; meta-analyses were conducted between weighted mean differences (WMD) in adolescence and adulthood. Heterogeneity was explored using meta-regression.

Results

Of 67 included studies, 49 were eligible for meta-analysis. PA was lower during adulthood than adolescence WMD(95%CI) -5.2(-7.3,-3.1) min/day MVPA over Mean(SD) 3.4(2.6)y; heterogeneity was high (I2>99.0%) and no predictors explained this variation (all p>0.05). When we restricted analysis to studies with data for males (n=29) and females (n=30) separately, there were slightly larger declines in WMD [-6.5(-10.6,-2.3) and -5.5(-8.4,-2.6) min/day MVPA] (both I2>99.0%). For studies with accelerometer data (n=9), the decline was -7.4(-11.6,-3.1) and longer follow-up indicated more of a decline in WMD (95%CI) [-1.9(-3.6,-0.2) min/day MVPA], explaining 27.0% of between-study variation. Of 18 studies not eligible for meta-analysis, 9 statistically tested change over time; 7 showed a decline and 2 showed no change.

Conclusion

PA declines modestly between adolescence and young adulthood. More objective longitudinal PA data (e.g. accelerometry)_over this transition would be valuable, as would investigating how PA change is associated with contemporaneous social transitions, to better inform PA promotion interventions.

Registration

PROSPERO ref:CRD42015030114.

Introduction

Physical activity in young people has been associated with a reduced risk of obesity [1], metabolic syndrome [2], beneficial effects on mental health [3], school performance [4], sleep duration [5] and wellbeing [6]. Most evidence suggests that physical activity declines with age throughout adolescence, although evidence on the magnitude of the decline is equivocal [7]. In addition, inactivity may track into adulthood [8], resulting in greater health risks later in life [9].

The transition to adulthood often includes major life changes including relocation, changes in living arrangements, academic and employment status and new social roles [10]. Such changes likely influence health-related behaviours [11]. Evidence suggests that the transition from adolescence to early adulthood, [12] including from high school to post-high school, [13] might particularly influence physical activity declines. However, the limited evidence is dominated by self-reported behaviour, which is susceptible to various forms of bias and there appears to be little objective data available.

How physical activity changes over the transition from adolescence to adulthood is unclear. Therefore, we asked, “How does physical activity change during the period from adolescence to early adulthood (age 13 to 30)?” To our knowledge, no reviews have investigated physical activity over this transition but the synthesis of the available evidence via a systematic review is important to better characterise change in physical activity over this important time.

Identifying characteristics of any changes may highlight potential strategies for physical activity promotion, including potentially distinguishing the respective importance of adolescence and young adulthood as targets for physical activity promotion. We aimed to identify the state of the evidence and pinpoint knowledge gaps regarding changes in physical activity occurring during the transition to adulthood. Specifically, we assessed whether physical activity changes between adolescence (13-19y) and early adulthood (16-30y), and the extent of this change; we hypothesised that physical activity declines over the transition from adolescence to adulthood.

Methods

We conducted a literature search of longitudinal observational studies providing data on physical activity in young people (PROSPERO ref: CRD42015030114). We searched seven electronic databases (Medline via PubMed, Embase via Ovid, PsycInfo (EBSCO), SCOPUS, ASSIA via ProQuest, Sportdiscus, Web of Science Core Collection) from 1980 until January 2017. We only included data collected after 1980 to ensure that results are relevant to contemporary populations while still representing 36 years of research. The search strategy focused on three themes: participants (including adolescents, young adults), outcomes (including MVPA, physical activity) and study type (including longitudinal, prospective). The full list of terms is available in Supplementary Table 1; the search was conducted by EW (Research Associate). The search was undertaken in parallel with a search on dietary behaviour so the search strategy also contains diet-related terms.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion was restricted to published longitudinal data with at least two data collection points within each age range; the mean age of at least one measurement was required to be in adolescence (13-19y) and at least one in young adulthood (16-30y). The overlapping age definitions enable inclusive definitions of both periods, and avoid arbitrary cut-offs limiting our search results. Thirty years-old has been suggested as the end of young adulthood [14] and adolescence is defined by the World Health Organization as 10-19 years [15]. Transitions from childhood into adolescence or throughout adolescence have been covered by previous reviews [7, 16], so we begin our review at age 13 to capture transitions occurring from mid-adolescence to early-adulthood. The physical activity measurements included in the papers had to be at least one year apart. We were interested in a wide variety of absolute measures of physical activity but excluded studies presenting only sedentary behaviour. Studies reporting no absolute physical activity over at least two time-points (including some tracking studies or those only reporting % participants meeting guidelines) were excluded. We did not approach authors for additional information as we did not want to bias this review in the event of differential author response. Contacting authors may help to ameliorate incomplete reporting of outcomes that may lead to potential bias in systematic reviews of trials [17], this is less of an issue in observational data [18]. Moreover, previous reviews report limited response (42%) after multiple requests, with the data received biased towards more recent studies [19]. All articles published in the English language in a scientific journal; regardless of country of origin and containing data collected 1980 onwards were considered for inclusion. Inclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Setting | All countries | None |

| Participants | Those aged between 13 and 30 years Mean age of at least one measurement in adolescence (13-19 years-old) and one in adulthood (16-30 years-old) |

Those aged below 13 years of age or above 30 years of age ≥2 measurements<16 years-old or ≥2 measurements >19 years-old Participant groups selected based on a pre-existing health condition (including obesity and eating disorders) |

| Outcomes | At least one measure of physical activity, for example:

|

Studies including no PA outcomes Studies reporting tracking of PA behaviours only with no data on absolute change in behaviour Studies reporting solely on sedentary behaviour |

| Study type | Longitudinal quantitative studies, with data collection including on specified outcomes over ≥2 time-points (minimum 1 year apart) where mean age of the cohort is between ages 13 and 30 (with at least one measurement in adolescence (13-19 years-old) and one in adulthood (16-30 years-old) | Other quantitative study types Qualitative studies Interventions Trial analyses |

| Publication type | Journal article | Conference abstract, study protocol, report, dissertation, book and professional journal |

| Publication year | 1980 onwards | Before 1980 |

| Language | English | All other languages |

Three reviewers (KC/EW/EvS) independently reviewed the same 1500 results from the initial title and abstract search (in 3 sets of 500). Iterative comparison and discussion allowed for development of a consistent screening approach; screening of all remaining titles/abstracts was divided between KC, EW and EvS. Subsequently, two reviewers (KC/RL) independently screened full texts for inclusion and discussed discrepancies to reach consensus. Hand searching of the references identified three additional full texts, none of which were included.

Where data from the same study was reported in multiple papers, the following decision hierarchy was applied: 1) the paper with most time-points; 2) additional papers with further time-points; 3) objective data (versus self-report); 4) largest number of baseline participants; 5) earliest publication date; and 6) largest number of follow-up participants.

Data extraction

KC conducted data extraction with 100% checked for accuracy (RL); discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Data extracted included: baseline date (date of the first wave meeting the inclusion criteria), study name, country, ethnicity, sex, socio-economic status; and number of participants, age, physical activity measurement method, and physical activity data at each relevant time-point. Any analysis of change was also recorded including whether any adjustments were made. Data was extracted for males and females separately where possible; if not available, data for the whole sample was extracted and data for other subgroups were extracted if an overall measure by sex was not available [20–28]. If data was not presented by sex or overall, data summarised by ethnicity was extracted if available [22, 23, 26, 28] and otherwise for whichever variable resulted in the least subgroups.

This review originally intended to address a second research question: “How do factors such as socio-economic status or particular lifestyle transitions influence these changes in physical activity behaviour?” Data extraction revealed there was little heterogeneous information available to address this question, and we therefore only focus on the main research question.

Assessment of risk of bias

Risk of bias was scored using an adapted version of a previously used scale (Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool) which has been explained in detail previously [29] and used in other physical activity reviews [30]. Participant representativeness, study size, participant drop-out, quality of physical activity data, and quality of change analyses were rated. These criteria were assessed by two independent reviewers (KC and HEB/EvS); in case of disagreement, consensus was derived by discussion with a further reviewer (EW). Each item was scored as ‘Strong’, ‘Moderate’ or ‘Weak’; if a paper provided insufficient information then it was scored as ‘Weak’. Scores for each item were summed and quality was defined as ‘Weak’ when at least one item was classed as ‘Weak’. Papers were classed as ‘Strong’ when three out of the five criteria were rated as ‘Strong’ and no items were scored as ‘Weak’; other studies were classed as ‘Moderate’. We scored the size of a study as ‘Strong’ if there were over 1000 participants at the follow up with the least participants; using 1000 as the threshold was an arbitrary decision but we deemed this suitable considering 22% of the included studies had ≥1000 participants. Analyses were scored as ‘Strong’ if they used a suitable statistical method to assess change (such as regression) and included appropriate adjustment for potential confounders. Studies were scored as ‘Strong’ if objective methods were used to assess physical activity and were the same at all time-points. If validity and reliability of self-reported methods were stated, and were the same over both time-points, then they were rated as ‘Moderate’. Scoring details are summarised in Supplementary Table 2.

Data preparation

Wherever possible, values from all included studies were converted to a common metric to enable meta-analysis of physical activity change. The metric chosen was the original unit reported for all studies with accelerometer data (MVPA min/day). If a paper presented more than one physical activity outcome, the one most comparable to MVPA was selected and otherwise the value most easily converted to MVPA min/day. The extent of data conversion was recorded for each study so it could be included in meta-regression. Conversion was defined as minimal when reported data were in min/day, min/week or similar and as extensive when any other conversion was necessary. As in a previous review [31], pedometer counts were translated to approximate MVPA using 100 steps/min, and a bout of activity was classed as 30 minutes. For data reporting MET minutes or MET times/week, the value reported was divided by the appropriate MET value if stated in the paper (or 5 for MVPA to account for the whole range of MVPA (≥4 METS [32])).

Due to the overlapping adolescent and adulthood time periods, decisions were made to class study time-points as ‘adolescence’ or ‘adulthood’. If only two time-points per study were available, the first was classed as adolescence and the second as adulthood. For studies with >2 time-points, at least one time-point was included as adolescence and at least one as adulthood, any further time-points were divided at 17.5 years-old (the mid-point between the adolescent and adulthood age ranges). The additional time-points <17.5y were incorporated with the adolescent estimate and time-points ≥17.5y were incorporated with the adult estimate so that mean activity values could be used where necessary; each time-point was used once. Sample size at follow-up(s) was assumed to be that of baseline when time-point specific participant numbers were not provided [33–35]. Where reported, medians, inter-quartile ranges and variance were converted to mean and standard deviation as suggested previously [36]. It was not possible to convert all data to include in the meta-analysis; reasons for this were presenting an activity score/index with insufficient information to convert it into min/day [37–46], presenting an infeasible number of hours of activity (mean of 25 hrs/day) [47], summing multiple measurements annually [48] and presenting energy expenditure per unit of body weight [49]. A further seven studies did not report standard deviations at one or more waves so could not be included in the meta-analysis [21, 50–55].

Statistical analysis

Data for each adolescent-adulthood comparison were combined in STATA using a random effects meta-analysis (STATA version 14, StataCorp, USA). As all studies included in the meta-analysis were converted to a common metric, non-standardised weighted mean differences (WMD) were calculated. Variation attributable to heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. If heterogeneity (I2>50%) was seen [18], meta-regression was used to test the impact of potential effect modifiers (baseline age, time between baseline and follow-up [the mean calculated for the adolescent and adult time periods used], region of study, baseline date, accelerometer versus non-accelerometer data, extent of conversion necessary to estimate MVPA). Effect modifiers were selected based on the data extracted and those used in a previous review [18]. Risk of bias score was not investigated as a potential effect modifier due to limited variability. Age and time between measurements were calculated using mean ages reported (and/or time between measurements where relevant). Region of study was summarised into four categories; Europe, North America, lower and middle income countries (LMICs: e.g. Brazil and Iran) and other high income countries (e.g. Australia and Japan). Baseline measurement date was taken from the included papers and referred to that used as baseline in this review where possible (other waves of data may have been available outside our inclusion criteria) but was not reported for 9 studies [33, 34, 38, 40, 47, 49, 56, 57]. Variables that were associated (p<0.05) in single models were included in a multiple model to explore the variance that could be explained.

Due to sex-differences in biology and behaviour during adolescence [58], a post-hoc decision was made to stratify meta-analyses by sex where data were available. In addition, due to the high heterogeneity of the data a further post-hoc meta-analysis was conducted only including accelerometer-assessed physical activity. For completeness, a separate meta-analysis including non-accelerometer methods was also conducted.

Lastly, the main meta-analysis was repeated restricting the age of baseline to ≤15 years-old and ≥18 years-old at follow-up to provide an estimate of change between more discrete age periods.

Funnel plot asymmetry and Eggers test for bias were conducted for all meta-analyses to investigate various forms of potential publication bias.

The results are reported in accordance with relevant guidance (Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) [59] and Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement (PRISMA) [60]).

Results

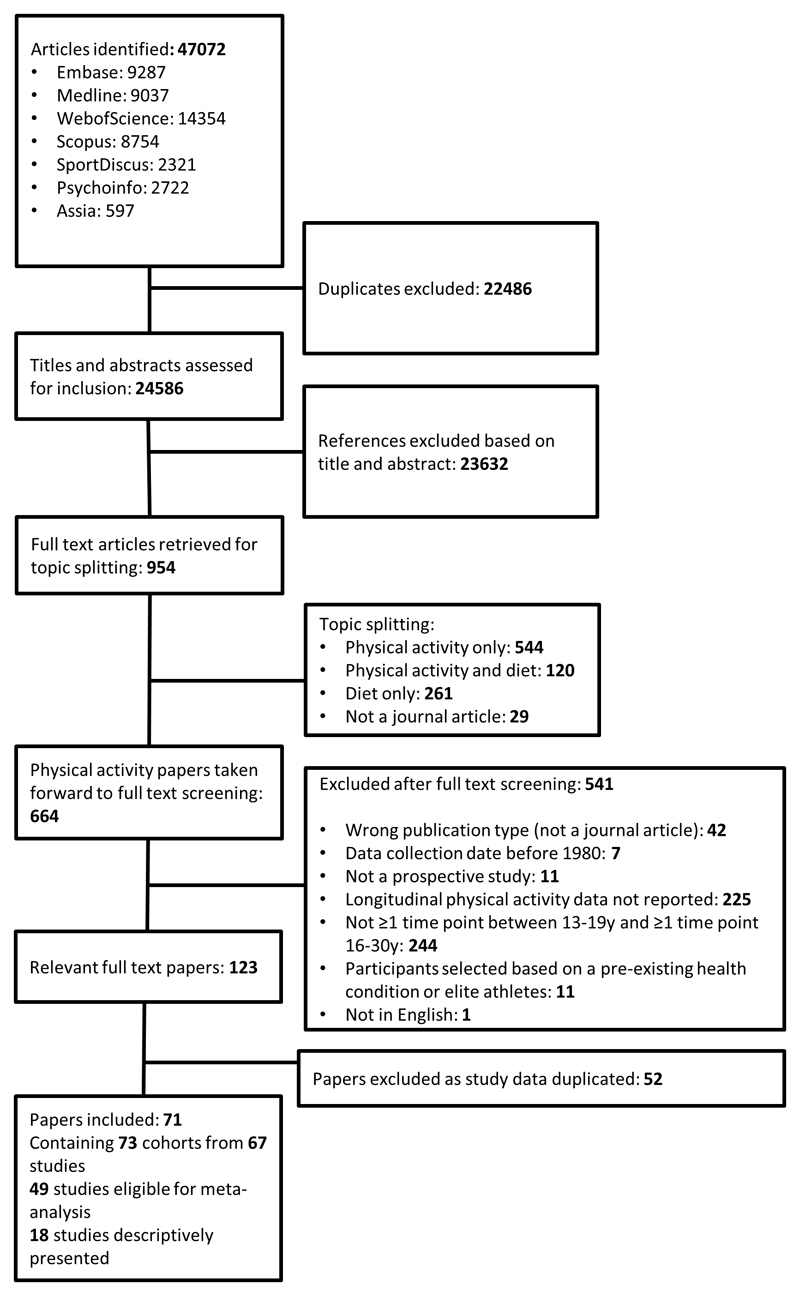

Of 47,072 articles identified (including physical activity and diet papers), 22,486 duplicates were excluded. The remaining 24,586 had titles and abstracts assessed for inclusion; 23,632 papers were excluded based on title/abstract. Of the remaining 954 papers; 544 included physical activity only and 120 included both physical activity and diet and were taken forward to full text screening. Of those full texts screened, 541 were excluded with the reasons included in Figure 1; this left 123 full text papers. Of these, 52 full text papers were excluded as they included duplicate data available in other included papers. This left 71 papers containing data on 73 cohorts (defined as a specific group followed over time; some papers include multiple cohorts) from 67 overarching studies; data from 49 of these studies were eligible for meta-analysis. Study characteristics for all included studies are available in Supplementary Table 3. Descriptive characteristics of the included studies, presented as those that were meta-analysed and those that were descriptively summarised are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Evidence search and exclusion process.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of the included studies, presented as those that were meta-analysed and those that were descriptively summarised (n=67 studies)

| Meta-analysed | Narrative | |

|---|---|---|

| N reporting (/49) | N reporting (/18) | |

| Sample size (n) | 49 | 18 |

| <100 | 9 | 7 |

| 100-499 | 22 | 6 |

| 500-999 | 7 | 1 |

| >1000 | 11 | 4 |

| Age at baseline (n) | 49 | 18 |

| Mean (SD) years | 15.6 (1.4) | 15.8 (1.5) |

| Length of follow-up (n) | 49 | 18 |

| Mean (SD) years | 3.4 (2.6) | 3.8 (3.0) |

| Region (n) | 49 | 18 |

| Europe | 20 | 10 |

| North America | 22 | 5 |

| LMIC | 3 | 0 |

| Other HIC | 4 | 3 |

| Ethnicity (n) | 20 | 5 |

| (% white Mean(SD)) | 69.3 (26.6) | 72.1 (16.3) |

| SES (n) | 9 | 2 |

| (% mothers with college degree Mean(SD)) | 39.7 (16.4) | 46.5 (12.0) |

LMIC: Low and middle income country

HIC: High income country

SES: Socio-economic status expressed as % mothers with college degree (the most commonly reported measure)

Supplementary Table 4 presents the results of individual item and overall risk of bias assessment scores. Initially, 87% agreement was achieved on risk of bias scoring with discrepancies resolved via discussion. Of the 71 papers included, 2 received a ‘Strong’ rating, 3 (4%) were rated as ‘Moderate’ and 66 (93%) as ‘Weak’. The large number of ‘Weak’ scores was mainly due to the strict criteria of any single item scoring as ‘Weak’ meaning that the overall rating for that paper was ‘Weak’.

Meta-analyses

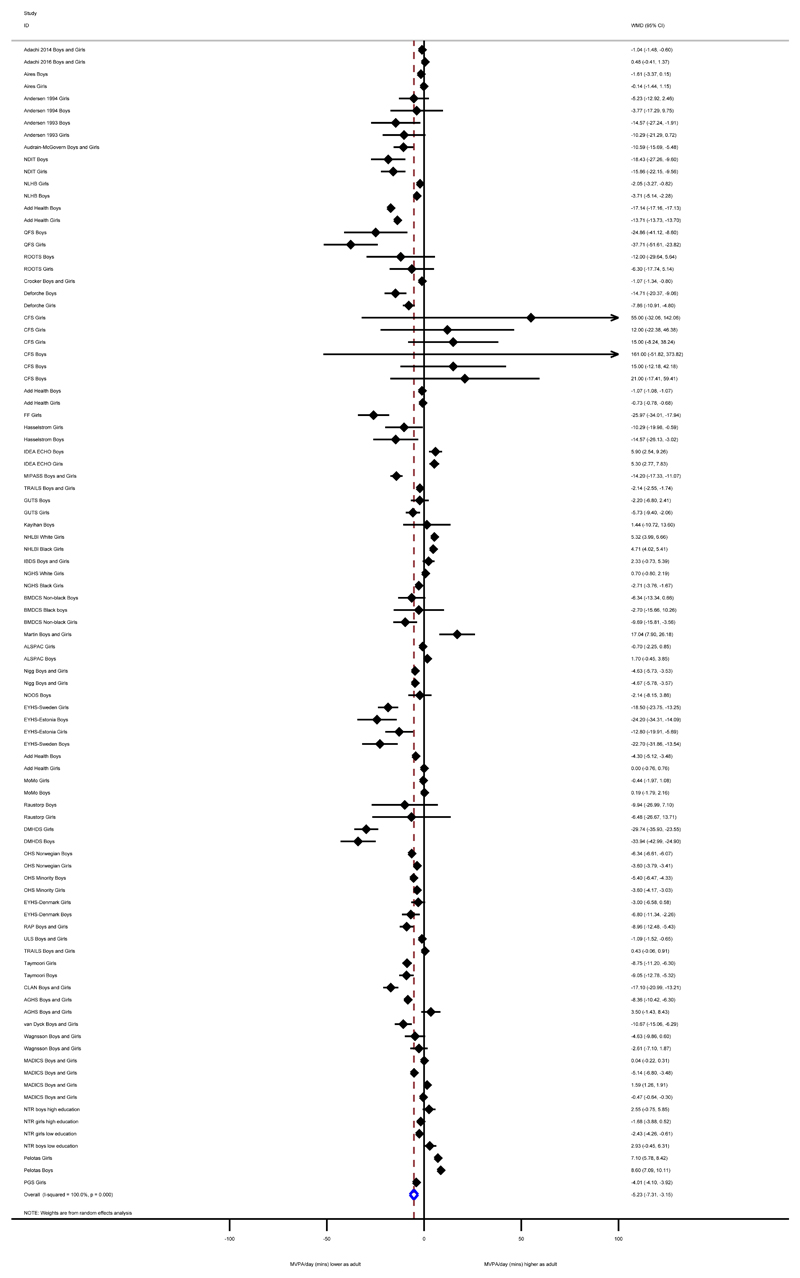

The pooled WMD displayed in Table 3 and Figure 2 indicate that physical activity is lower during adulthood than during adolescence WMD (95%CI) -5.2 (-7.3,-3.1) min/day MVPA over a mean 3.4 (SD:2.6) years. There was a statistically significant (χ2=5.8e+06, p<0.001) high amount of heterogeneity present between studies (I2>99.0%) and none of the included predictors explained this variation (all p>0.05).

Table 3.

Summary of physical activity reported in meta-analysed studies and meta-analysis results

| Type of study included | N studies | Age range adolescence | Age range adulthood | Mean (SD) follow-up (years) |

Mean (SD) adolescent MVPA mins/day |

Pooled WMD (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All eligible studies | 49 | 13-19 | 16-30 | 3.4 (2.6) | 41.0 (29.1) | -5.2 (-7.3, -3.1) | >99.0 |

| All eligible studies (males) | 29 | 13-19 | 16-30 | 4.2 (2.8) | 49.1 (31.1) | -6.5 (-10.6, -2.3) | >99.0 |

| All eligible studies (females) | 30 | 13-19 | 16-30 | 3.8 (2.8) | 37.2 (27.8) | -5.5 (-8.4, -2.6) | >99.0 |

| Accelerometer only | 9 | 13-19 | 16-30 | 4.3 (2.9) | 43.5 (16.8) | -7.4 (-11.6, -3.1) | 95.0 |

| Non-accelerometer | 40 | 13-19 | 16-30 | 3.2 (2.5) | 40.4 (31.4) | -4.8 (-7.0, -2.5) | >99.0 |

| Restricted ages | 3 | 13-15 | 18-30 | 7.4 (3.4) | 47.9 (15.0) | -8.2 (-23.8, 7.5) | 89.7 |

SD: Standard deviation

MVPA: moderate to vigorous physical activity

WMD: Weighted Mean Difference

95% CI: 95% Confidence Intervals

Restricted ages: restricting the age of baseline to ≤15 years-old and ≥18 years-old at follow-up

Figure 2.

Change in physical activity (MVPA min/day) from adolescence to adulthood from all eligible studies.

Results for males and females (Table 3, and Supplementary figures 1 and 2, respectively) both indicated a decline in physical activity from adolescence to adulthood, both with very high heterogeneity between studies.

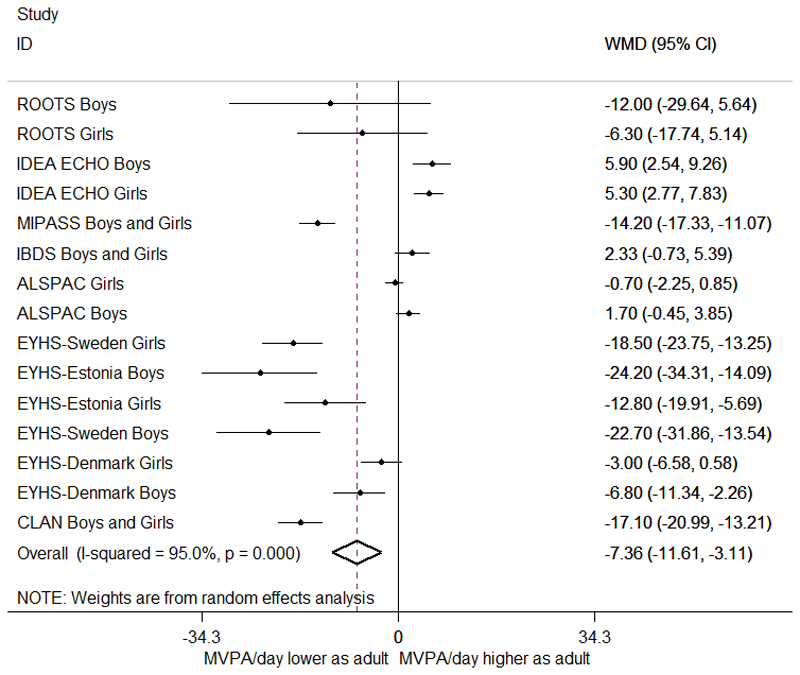

The results based only on accelerometer data suggested a slightly greater decline in MVPA between adolescence and adulthood -7.4 (-11.6,-3.1) min/day MVPA with a high amount of heterogeneity present between studies (χ2=272.47, p<0.001, I2=95.0%) (Table 3, Figure 3). The only variable included in meta-regression that explained any of this variation was the difference in age between time-points with a greater age difference indicating more of a decline: WMD -1.9 (-3.6,-0.2), p=0.03, with 27.0% of variation between studies explained. This value suggests that for every extra year of follow-up the decline is 1.9 minutes greater. When restricting to non-accelerometer data, the WMD was -6.3 (-8.1,-4.4) min/day MVPA and none of the high amount of heterogeneity present between studies (χ2=5541.7, p<0.001, I2=99.2%) was explained by variables tested with meta-regression.

Figure 3.

Change in physical activity (MVPA min/day) from adolescence to adulthood from eligible studies using accelerometer-assessed physical activity

When adolescence was restricted to ≤15 years-old and adulthood as >18 years-old, three studies were included [28, 61, 62]. When restricted to these distinct age groups, results were non-significant but the extent of the WMD was comparable to the previous results (WMD -8.2 (-23.8, 7.5) min/day MVPA); heterogeneity remained high (χ2=38.9, p<0.001, I2=89.7%) (Table 3).

Funnel plot asymmetry and Eggers test for bias suggested no evidence of asymmetry in any meta-analyses (all p>0.188); indicating that these tests showed no evidence of publication bias.

Of the 18 studies that were not eligible for meta-analysis, 9 statistically tested for change in physical activity over time; of these 9 studies, 7 showed a decline in physical activity [37, 41, 48, 52] and two showed no change between adolescence and adulthood [21, 47]. All of these studies used questionnaire reported measurement methods with the exception of one using an activity diary [49] and one using a recall [55]. The median [IQR] age in adolescence was 15.9 [14.9 to 16.5] years and 19.5 [17.4 to 22.0] years in adulthood. Median time between baseline and follow-up measurements was 2 [1.4 to 7.0] years and baseline participant numbers were 166 [84 to 994].

Discussion

Meta-analysis of published longitudinal data indicated that physical activity declines over the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Results from all 49 eligible studies indicated that daily MVPA declined by a mean of 5.2 min/day which is equivalent to approximately 13% of the mean baseline value; this decline occurred over a mean duration of 3.4 (SD:2.6) years. Stratified analyses showed slight sex differences, with a slightly greater decline observed in males. For studies assessing physical activity with accelerometers, a decline of 7.4 minutes of daily MVPA was observed. This equated to 17% of the mean baseline estimate and occurred over a mean follow-up of 4.3 (SD:2.9) years. Half of the non-meta-analysed studies statistically tested change in physical activity between adolescence and adulthood, of those; the majority (78%) reported a decline.

Interpretation

All meta-analyses displayed large heterogeneity. This limits the validity of pooling the results and estimating a single summary result; the results of these meta-analyses should therefore be interpreted with caution. However, random effects meta-analysis should allow for heterogeneity and to some extent have led to relatively conservative results with wider confidence intervals and larger p-values when heterogeneity exists.

We investigated potential sources of heterogeneity using meta-regression and by separately reporting results for studies reporting accelerometer-assessed physical activity and self-report assessed activity. It was only in the accelerometer-assessed analysis that any variables investigated in meta-regression explained any variation, with a greater age difference between adolescence and adulthood indicating slightly more of a decline in physical activity as would be expected due to there being more time for change to occur.

The slightly larger decline observed in males than females could be at least partly because boys were more physically active than girls in adolescence. Previous work has observed a larger physical activity decline in girls during early adolescence (<12 years-old) but a greater decrease among boys later in adolescence [7, 58], suggesting a reduction in sex differences in physical activity later in adolescence. Our results add to this evidence by suggesting that these sex differences may further reduce over the transition to adulthood.

Although the inclusion criteria for early adulthood required at least one measurement of physical activity between the ages of 16 and 30, the majority of these data points were at the younger end of this age range. The adulthood measure in 35% of all studies was over age 21 with only 8% over 25 years-old. For studies using accelerometers to measure physical activity, 33% (3/9) had a follow-up after age 21 with 11% (1/9) after 25 years-old.

The tool we used to assess risk of bias led to only 2 of 71 (2.8%) papers being scored as Strong; 66 (93%) were scored as Weak. Our criteria were strict as just one ‘weak’ rating leading to the overall classification as ‘Weak’, Nevertheless, this suggests a paucity of good quality data which is important to further investigate due to the potential importance of early adulthood for developing long lasting health behaviours.

As adolescence and early adulthood are times of increasing autonomy, positive behaviours established during this time could potentially last into later adulthood, making this transitional time a potentially important target for health promotion [63]. Further, moving from adolescence into adulthood is characterised by transitions between different social roles [14] and major transitions including moving out of the family home, changes in school/work environment and financial circumstances. Many of these transitions are associated with health behaviours including physical activity, but further work would be useful to characterise physical activity over the young adulthood period while taking account of these transitions [11]. The period of late adolescence to early adulthood has been suggested as an important, but overlooked, age to establish long-term health behaviour patterns [63].

Relationship to prior knowledge

Although our results indicate that MVPA appears to decline by as much as 7 min/day between adolescence and early adulthood, the physical activity recommendations for adolescents (60 min/day MVPA) and adults (150 min/week of moderate or 75 min/week of vigorous activity) differ by more than this. As a weekly average, the adult recommendations suggest 21 minutes of moderate, or 10 minutes of vigorous activity daily, which is substantially less than the 60 min/day recommended in adolescence. Therefore the absolute change in activity identified here of up to 7 min/day does not appear to account for the difference between adolescent (60 min/day) and adult physical activity recommendations (~10-21 min/day).

One could therefore argue that this decline is acceptable and should not present a health hazard at a population level. However, when this decline is put in the context of a meta-analysis from a large worldwide study [2] indicating that a 10-minute increase in MVPA was associated with a smaller waist circumference and lower fasting insulin among young people, this decline may have important health implications at the population level. Further, the mean time between adolescence and adulthood measurements was 3.4 years and although we did not test the linearity of changes over time, if this change was extrapolated over 10 years (e.g. 15y-25y) it would amount to a potential decline of closer to 15 min/day. Further research with objective measures in high quality studies that continue well into adulthood with multiple time-points are needed to further investigate this. Although we did not assess tracking of activity here, low physical activity in adolescence is likely to progress to adulthood inactivity [35] which is linked to increased risk of many diseases including type 2 diabetes, cancer and also mortality [9].

The evidence on changes in physical activity during other stages of the life course suggest declines of 4% per year throughout childhood [64] and 7% per year during adolescence [7]. The modest decline observed here is comparable in relative terms, equating to an approximate 13% decline compared to the baseline value over a mean follow-up duration of 3.4 years. Taken together, this evidence suggests that at a population-level physical activity declines steadily throughout the first decades of life and that preventing declines in physical activity throughout this period could be valuable. Studying population-level estimates may mask individual variations in patterns of change, and the important influence of various social transitions which may occur at different times for different people (such as starting employment, moving out of the family home, or having children). Further research on trajectories of change in physical activity behaviour may help unravel some of these uncertainties.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to meta-analyse change in physical activity over the transition between adolescence and adulthood. Although heterogeneity was high and results should be interpreted with caution, limiting the results to studies using accelerometer-assessed physical activity, which should reduce measurement error [65], indicated a similar decline. Despite the high heterogeneity, we believe that the review would be less useful without the meta-analyses. Although we investigated potential causes of heterogeneity using meta-regression, few factors were significant.

In the analysis focused on accelerometer-assessed activity, there was some indication that time between measurements may have explained some of the heterogeneity. We acknowledge slight deviations from our published protocol. We did not search in the Cochrane library (we excluded trials), CINAHL (not relevant as is nursing journal database), and Psychlit (not available at our institution). However, as reference checking of included papers did not identify additional papers, we are confident that we have done a comprehensive search. We did not conduct duplicate abstract screening which is a limitation although 1500 articles were triple screened to ensure consistency amongst the three reviewers. Further, although data extraction was 100% checked it was not extracted in duplicate.

We believe that defining adolescence as 13-19 years-old is appropriate. Although menarche may occur for some girls before age 13, socially, especially in developed countries (source of 95% of the data) 13 years-old is classed as at least mid-adolescence. Our analysis design distinguishes this review as we focused on the transition out of adolescence into adulthood rather than change in physical activity during adolescence which has been reviewed previously [7, 16]. As we used overlapping age groups, an included study may have two time-points that are arguably both in adolescence (such as 13 and 17 years-old). The sensitivity analysis restricting to studies reporting data on <15 years-old (adolescence) and >18 years-old (adulthood) indicated a non-significant decline of -8.2 (-23.8, 7.5) min/day MVPA, but with only three studies included with this strict age criteria, we believe using broader age categories was appropriate to be as inclusive as possible.

A strength of this work is that sufficient homogenous data was present to perform a meta-analysis. However, data conversion was necessary, requiring assumptions which may have led to error in the absolute values used although this should not have greatly influenced the within-study change estimates. Similarly, we used the data presented in each paper that was most similar to MVPA. Sometimes this was not directly comparable (e.g. overall activity) but was converted to min/day. As most studies did not statistically test change in physical activity and only provided descriptive data, this conversion and meta-analysis was useful to gain a tangible overview of results.

The review aimed to characterise change in physical activity between adolescence and adulthood, therefore we did not use all time-points separately as they were condensed into broad adolescent and adulthood age periods; annual change has been examined throughout adolescence [7] and was beyond the scope of this review. We were keen to take study size into account so believe it was most appropriate to use meta-analysis, rather than computing an estimate such as percentage annual change. The included studies were all published in English and mostly from North America, Europe and other high income countries (95% of studies), so these results are not likely to be generalizable to LMICs. We only included peer-reviewed publications, which may be susceptible to publication bias; however, funnel plots did not indicate evidence of asymmetry.

Implications for policy, practice and research

Physical activity declines between adolescence and adulthood. Average adult physical activity levels are too low to benefit a range of health outcomes. Continued efforts to maintain or increase adolescent physical activity and to prevent a decline into adulthood could have important public health benefits. More high quality longitudinal physical activity data over this transition would be valuable, especially in the young adulthood period, to better characterise physical activity patterns over this time to better inform how physical activity promotion interventions might most effectively target this important group.

Conclusion

Published longitudinal data indicate that physical activity declines over the transition from adolescence to adulthood by an average of 5.2 minutes of MVPA per day. Both males and females had lower physical activity in adulthood compared to adolescence. Objectively-assessed physical activity showed a slightly larger decline of 7.4 minutes of daily MVPA. More objective longitudinal physical activity data over this transition would be valuable, as would investigating how change in physical activity is associated with various contemporaneous social transitions.

Supplementary Material

What is already known?

Physical activity is lower in adulthood than adolescence

The adolescence-adulthood transition is important to target behaviour change interventions due to increasing autonomy, and positive behaviours established over this time have the potential to last into later adulthood.

What are the new findings?

Data from 49 studies indicate that over the transition from adolescence to adulthood moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) declines by a mean of 5.2 min/day (or approximately 13% of the baseline value).

Most studies assessed physical activity by self-report, but the 9 studies that used accelerometers showed a mean decline of 7.4 minutes of daily MVPA (17% of mean baseline value) between adolescence and adulthood.

The observed decline in physical activity was slightly larger in males than females (-6.5 vs. -5.5 min/day), and, based on the accelerometer data, the decline was larger with each year of follow-up (further decline of -1.9 min/day per year).

Funding

Funding for this study and the work of all authors was supported, wholly or in part, by the Centre for Diet and Activity Research (CEDAR), a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence (RES-590-28-0002). Funding from the British Heart Foundation, Department of Health, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, and the Wellcome Trust, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged. The work of Kirsten Corder, Helen Brown, Eleanor Winpenny and Esther M F van Sluijs was supported by the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_12015/7). Rebecca Love is funded by a Gates Cambridge Scholarship.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Kirsten Corder reports receiving the following grants: Lead Applicant - A cluster randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the GoActive programme to increase physical activity among 13-14 year-old adolescents. Project: 13/90/18 National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research Programme Sept 2015 – Feb 2019. Co-Applicant - Opportunities within the school environment to shift the distribution of activity intensity in adolescents. Department of Health Policy Research Programme. Dec 2013 – Nov 2016. Kirsten Corder is a Director of Ridgepoint Consulting Limited, an operational improvement consultancy.

References

- 1.Wareham N, van Sluijs E, Ekelund U. Physical activity and obesity prevention: a review of the current evidence. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2005 doi: 10.1079/pns2005423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ekelund U, Luan J, Sherar LB, Esliger DW, Griew P, Cooper A. Moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary time and cardiometabolic risk factors in children and adolescents. Jama. 2012;307(7):704–712. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith A, Biddle S, editors. Youth physical activity and sedentary behavior. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh A, Uijtdewilligen L, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Physical activity and performance at school: a systematic review of the literature including a methodological quality assessment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(1):49–55. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collings PJ, Wijndaele K, Corder K, Westgate K, Ridgway CL, Sharp SJ, Dunn V, Goodyer I, Ekelund U, Brage S. Magnitude and determinants of change in objectively-measured physical activity, sedentary time and sleep duration from ages 15 to 17.5y in UK adolescents: the ROOTS study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:61. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0222-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ussher MH, Owen CG, Cook DG, Whincup PH. The relationship between physical activity, sedentary behaviour and psychological wellbeing among adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(10):851–856. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumith SC, Gigante DP, Domingues MR, Kohl HW., 3rd Physical activity change during adolescence: a systematic review and a pooled analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(3):685–698. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Telema R, Yang X, Viikari J, Valimaki I, Wanne O, Raitakari O. Physical activity from childhood to adulthood a 21-year tracking study. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(3):267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khaw K-T, Wareham N, Bingham S, Welch A, Luben R, Day N. Combined Impact of Health Behaviours and Mortality in Men and Women: The EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Population Study. PLoS Medicine. 2008;5(1):e12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horn DB, O'Neill JR, Pfeiffer KA, Dowda M, Pate RR. Predictors of physical activity in the transition after high school among young women. Journal of physical activity & health. 2008;5(2):275–285. doi: 10.1123/jpah.5.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cluskey M, Grobe D. College weight gain and behavior transitions: male and female differences. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(2):325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bell S, Lee C. Emerging adulthood and patterns of physical activity among young Australian women. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12(4):227–235. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1204_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson M, Neumark-Stzainer D, Hannan P, Sirard J, Story M. Longitudinal and secular trends in physical activity and sedentary behavior during adolescence. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):e1627–e1634. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rindfuss RR. The young adult years: diversity, structural change, and fertility. Demography. 1991;28(4):493–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health: Adolescent development. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/dev/en/

- 16.Pearson N, Haycraft E, PJ J, Atkin AJ. Sedentary behaviour across the primary-secondary school transition: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2017;94:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan AW, Altman DG. Identifying outcome reporting bias in randomised trials on PubMed: review of publications and survey of authors. BMJ. 2005;330(7494):753. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38356.424606.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brooke HL, Corder K, Atkin AJ, van Sluijs EM. A systematic literature review with meta-analyses of within- and between-day differences in objectively measured physical activity in school-aged children. Sports Med. 2014;44(10):1427–1438. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0215-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selph S, Ginsburg A, C R. Impact of contacting study authors to obtain additional data for systematic reviews: diagnostic accuracy studies for hepatic fibrosis. Systematic Reviews. 2014;3:107. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bielemann RM, Ramires VV, Gigante DP, Hallal PC, Horta BL. Longitudinal and cross-sectional associations of physical activity with triglyceride and HDLc levels in young male adults. Journal of physical activity & health. 2014;11:784–789. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2012-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung ME, Bray SR, Ginis KAM. Behavior Change and the Freshman 15: Tracking Physical Activity and Dietary Patterns in 1st-Year University Women. Journal of American College Health. 2008;56:523–530. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.5.523-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimm SY, Glynn NW, Kriska AM, Barton BA, Kronsberg SS, Daniels SR, Crawford PB, Sabry ZI, Liu K. Decline in physical activity in black girls and white girls during adolescence. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:709–715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lappe JM, Watson P, Gilsanz V, Hangartner T, Kalkwarf HJ, Oberfield S, Shepherd J, Winer KK, Zemel B. The longitudinal effects of physical activity and dietary calcium on bone mass accrual across stages of pubertal development. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:156–164. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez-Gomez D, Mielke GI, Menezes AM, Goncalves H, Barros FC, Hallal PC. Active commuting throughout adolescence and central fatness before adulthood: prospective birth cohort study. PloS one. 2014;9(5):e96634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palakshappa D, Virudachalam S, Oreskovic NM, Goodman E. Adolescent Physical Education Class Participation as a Predictor for Adult Physical Activity. Child Obes. 2015;11:616–623. doi: 10.1089/chi.2015.0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sagatun Å, Kolle E, Anderssen SA, Thoresen M, Søgaard AJ. Three-year follow-up of physical activity in Norwegian youth from two ethnic groups: Associations with socio-demographic factors. BMC Public Health. 2008;8 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zarrett N, Bell BA. The effects of out-of-school time on changes in youth risk of obesity across the adolescent years. J Adolesc. 2014;37:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwon S, Janz KF, Letuchy EM, Burns TL, Levy SM. Developmental Trajectories of Physical Activity, Sports, and Television Viewing During Childhood to Young Adulthood: Iowa Bone Development Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:666–672. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(1):12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown HE, Atkin AJ, Panter J, Wong G, Chinapaw MJ, van Sluijs EM. Family-based interventions to increase physical activity in children: a systematic review, meta-analysis and realist synthesis. Obes Rev. 2016;17(4):345–360. doi: 10.1111/obr.12362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogilvie D, Foster CE, Rothnie H, Cavill N, Hamilton V, Fitzsimons CF, Mutrie N, Scottish Physical Activity Research C Interventions to promote walking: systematic review. BMJ. 2007;334(7605):1204. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39198.722720.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adachi PJC, Willoughby T. From the couch to the sports field: The longitudinal associations between sports video game play, self-esteem, and involvement in sports. Psychology of Popular Media Culture. 2015;4:329–341. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nordstrom A, Neovius MG, Rossner S, Nordstrom P. Postpubertal development of total and abdominal percentage body fat: An 8-year longitudinal study. Obesity. 2008;16:2342–2347. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raustorp A, Ekroth Y. Tracking of pedometer-determined physical activity: a 10-year follow-up study from adolescence to adulthood in Sweden. Journal of physical activity & health. 2013;10:1186–1192. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.8.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boreham C, Robson PJ, Gallagher AM, Cran GW, Savage M, Murray LJ. Tracking of physical activity, fitness, body composition and diet from adolescence to young adulthood: The young hearts project, Northern Ireland. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2004;1 doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-1-14. no pagination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Souza MC, Eisenmann JC, ES DV, De Chaves RN, De Moraes Forjaz CL, Maia JAR. Modeling the dynamics of BMI changes during adolescence. the oporto growth, health and performance study. Int J Obes. 2015;39:1063–1069. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freitas D, Beunen G, Maia J, Claessens A, Thomis M, Marques A, Gouveia É, Lefevre J. Tracking of fatness during childhood, adolescence and young adulthood: a 7-year follow-up study in Madeira Island, Portugal. Ann Hum Biol. 2012;39:59–67. doi: 10.3109/03014460.2011.638322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magarey AM, Boulton TJ, Chatterton BE, Schultz C, Nordin BE. Familial and environmental influences on bone growth from 11-17 years. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:1204–1210. doi: 10.1080/080352599750030293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Porkka KV, Raitakari OT, Leino A, Laitinen S, Rasanen L, Ronnemaa T, Marniemi J, Lehtimaki T, Taimela S, Dahl M, et al. Trends in serum lipid levels during 1980-1992 in children and young adults. The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:64–77. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rauner A, Jekauc D, Mess F, Schmidt S, Woll A. Tracking physical activity in different settings from late childhood to early adulthood in Germany: The MoMo longitudinal study Health behavior, health promotion and society. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:391. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1731-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Telama R, Yang X, Leskinen E, Kankaanpää A, Hirvensalo M, Tammelin T, Viikari JSA, Raitakari OT. Tracking of physical activity from early childhood through youth into adulthood. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:955–962. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benitez-Porres J, Alvero-Cruz JR, Carrillo de Albornoz M, Correas-Gomez L, Barrera-Exposito J, Dorado-Guzman M, Moore JB, Carnero EA. The Influence of 2-Year Changes in Physical Activity, Maturation, and Nutrition on Adiposity in Adolescent Youth. PloS one. 2016;11(9):e0162395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gunnell KE, Flament MF, Buchholz A, Henderson KA, Obeid N, Schubert N, Goldfield GS. Examining the bidirectional relationship between physical activity, screen time, and symptoms of anxiety and depression over time during adolescence. Prev Med. 2016;88:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huppertz C, Bartels M, de Geus EJC, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Rose RJ, Kaprio J, Silventoinen K. The effects of parental education on exercise behavior in childhood and youth: A study in Dutch and Finnish twins. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 2016 doi: 10.1111/sms.12727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bagur-Calafat C, Farrerons-Minguella J, Girabent-Farres M, Serra-Grima JR. The impact of high level basketball competition, calcium intake, menses, and hormone levels in adolescent bone density: a three-year follow-up. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2015;55:58–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baxter-Jones ADG, Eisenmann JC, Mirwald RL, Faulkner RA, Bailey DA. The influence of physical activity on lean mass accrual during adolescence: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2008;105:734–741. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00869.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lantz H, Bratteby LE, Fors H, Sandhagen B, Sjöström L, Samuelson G. Body composition in a cohort of Swedish adolescents aged 15, 17 and 20.5 years. Acta Paediatrica, International Journal of Paediatrics. 2008;97:1691–1697. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deheeger M, Bellisle F, Rolland-Cachera MF. The French longitudinal study of growth and nutrition: data in adolescent males and females. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2002;15:429–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-277x.2002.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pinto BM, Cherico NP, Szymanski L, Marcus BH. Longitudinal changes in college students' exercise participation. J Am Coll Health. 1998;47:23–27. doi: 10.1080/07448489809595615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi HJ, Nakamura K, Kizuki M, Inose T, Seino K, Takano T. Extracurricular sports activity around growth spurt and improved tibial cortical bone properties in late adolescence. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:1608–1613. doi: 10.1080/08035250600690609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wichstrom L, von Soest T, Kvalem IL. Predictors of growth and decline in leisure time physical activity from adolescence to adulthood. Health Psychol. 2013;32:775–784. doi: 10.1037/a0029465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Graham DJ, Sirard JR, Neumark-Sztainer D. Adolescents' attitudes toward sports, exercise, and fitness predict physical activity 5 and 10 years later. Prev Med. 2011;52:130–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eime RM, Harvey JT, Sawyer NA, Craike MJ, Symons CM, Payne WR. Changes in sport and physical activity participation for adolescent females: a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:533. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3203-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kayihan G. Effect of physical activity on body composition changes in young adults. A four-year longitudinal study. Medicina dello Sport. 2014;67:423–435. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Rodgers K, Cuevas J, Sass J. Longitudinal variation in adolescent physical activity patterns and the emergence of tobacco use. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:622–633. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Corder K, Sharp SJ, Atkin AJ, Griffin SJ, Jones AP, Ekelund U, van Sluijs EM. Change in objectively measured physical activity during the transition to adolescence. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(11):730–736. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Jama. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ortega FB, Konstabel K, Pasquali E, Ruiz JR, Hurtig-Wennlof A, Maestu J, Lof M, Harro J, Bellocco R, Labayen I, et al. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time during childhood, adolescence and young adulthood: a cohort study. PloS one. 2013;8:e60871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fortier MD, Katzmarzyk PT, Malina RM, Bouchard C. Seven-year stability of physical activity and musculoskeletal fitness in the Canadian population. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:1905–1911. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200111000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nelson MC, Story M, Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Lytle LA. Emerging adulthood and college-aged youth: an overlooked age for weight-related behavior change. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(10):2205–2211. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cooper AR, Goodman A, Page AS, Sherar LB, Esliger DW, van Sluijs EM, Andersen LB, Anderssen S, Cardon G, Davey R, et al. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time in youth: the International children's accelerometry database (ICAD) Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:113. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0274-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Corder K, van Sluijs EM, Wright A, Whincup P, Wareham NJ, Ekelund U. Is it possible to assess free-living physical activity and energy expenditure in young people by self-report? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;89(3):862–870. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adachi PJC, Willoughby T. It's not how much you play, but how much you enjoy the game: the longitudinal associations between adolescents' self-esteem and the frequency versus enjoyment of involvement in sports. Journal Of Youth And Adolescence. 2014;43:137–145. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9988-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aires L, Silva G, Martins C, Santos MP, Ribeiro JC, Mota J. Influence of activity patterns in fitness during youth. International Journal Of Sports Medicine. 2012;33:325–329. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1297955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Andersen LB, Haraldsdottir J. Tracking of cardiovascular-disease risk-factors including maximal oxygen-uptake and physical-activity from late teenage to adulthood - an 8-year follow-up-study. Journal Of Internal Medicine. 1993;234:309–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1993.tb00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Andersen LB. Changes in physical activity are reflected in changes in fitness during late adolescence. A 2-year follow-up study. The Journal Of Sports Medicine And Physical Fitness. 1994;34:390–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barnett TA, Maximova K, Sabiston CM, Van Hulst A, Brunet J, Castonguay AL, Bélanger M, O'Loughlin J. Physical activity growth curves relate to adiposity in adolescents. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23:529–533. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Birkeland MS, Torsheim T, Wold B. A longitudinal study of the relationship between leisure-time physical activity and depressed mood among adolescents. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2009;10:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boone-Heinonen J, Guilkey DK, Evenson KR, Gordon-Larsen P. Residential self-selection bias in the estimation of built environment effects on physical activity between adolescence and young adulthood. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:70. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Campbell PT, Katzmarzyk PT, Malina RM, Rao DC, Perusse L, Bouchard C. Prediction of physical activity and physical work capacity (PWC150) in young adulthood from childhood and adolescence with consideration of parental measures. Am J Hum Biol. 2001;13:190–196. doi: 10.1002/1520-6300(200102/03)13:2<190::AID-AJHB1028>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Collings PJ, Wijndaele K, Corder K, Westgate K, Ridgway CL, Sharp SJ, Dunn V, Goodyer I, Ekelund U, Brage S. Magnitude and determinants of change in objectively-measured physical activity, sedentary time and sleep duration from ages 15 to 17.5y in UK adolescents: the ROOTS study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2015;12:10. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0222-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Crocker P, Sabiston C, Forrestor S, Kowalski N, Kowalski K, McDonough M. Predicting change in physical activity, dietary restraint, and physique anxiety in adolescent girls: examining covariance in physical self-perceptions. Can J Public Health. 2003;94:332–337. doi: 10.1007/BF03403555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Deforche B, Van Dyck D, Deliens T, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Changes in weight, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and dietary intake during the transition to higher education: a prospective study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:16. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gordon-Larsen P, Adair LS, Popkin BM. Ethnic differences in physical activity and inactivity patterns and overweight status. Obes Res. 2002;10:141–149. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Han JL, Dinger MK, Hull HR, Randall NB, Heesch KC, Fields DA. Changes in women's physical activity during the transition to college. American Journal of Health Education. 2008;39:194–199. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hasselstrøm H, Hansen SE, Froberg K, Andersen LB. Physical fitness and physical activity during adolescence as predictors of cardiovascular disease risk in young adulthood. Danish Youth and Sports Study. An eight-year follow-up study. Int J Sports Med. 2002;23(Suppl 1):S27–S31. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-28458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hearst MO, Patnode CD, Sirard JR, Farbakhsh K, Lytle LA. Multilevel predictors of adolescent physical activity: a longitudinal analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hobin E, So J, Rosella L, Comte M, Manske S, McGavock J. Trajectories of objectively measured physical activity among secondary students in Canada in the context of a province-wide physical education policy: a longitudinal analysis. J Obes. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/958645. 958645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hunter S, Leatherdale ST, Storey K, Carson V. A quasi-experimental examination of how school-based physical activity changes impact secondary school student moderate- to vigorous- intensity physical activity over time in the COMPASS study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:86. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0411-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Janssens KAM, Oldehinkel AJ, Bonvanie IJ, Rosmalen JGM. An inactive lifestyle and low physical fitness are associated with functional somatic symptoms in adolescents. The TRAILS study. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76:454–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kahn JA, Huang B, Gillman MW, Field AE, Austin SB, Colditz GA, Frazier AL. Patterns and determinants of physical activity in U.S. adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kwon S, Lee J, Carnethon MR. Developmental trajectories of physical activity and television viewing during adolescence among girls: National Growth and Health Cohort Study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:667. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2043-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lemoyne J, Valois P, Wittman W. Analyzing Exercise Behaviors during the College Years: Results from Latent Growth Curve Analysis. PloS one. 2016;11(4):e0154377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Martin AJ, Liem GAD, Coffey L, Martinez C, Parker PP, Marsh HW, Jackson SA. What happens to physical activity behavior, motivation, self-concept, and flow after completing school? a longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 2010;22:437–457. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mitchell JA, Pate RR, Dowda M, Mattocks C, Riddoch C, Ness AR, Blair SN. A prospective study of sedentary behavior in a large cohort of youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:1081–1087. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182446c65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nigg CR. Explaining adolescent exercise behavior change: a longitudinal application of the transtheoretical model. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23:11–20. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2301_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ramires VV, Dumith SC, Wehrmeister FC, Hallal PC, Menezes AM, Goncalves H. Physical activity throughout adolescence and body composition at 18 years: 1993 Pelotas (Brazil) birth cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13(1):105. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0430-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Richards R, Poulton R, Reeder AI, Williams S. Childhood and contemporaneous correlates of adolescent leisure time physical inactivity: a longitudinal study. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rockette-Wagner B, Hipwell AE, Kriska AM, Storti KL, McTigue KM. Activity Levels over Four Years in a Cohort of Urban-Dwelling Adolescent Females. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schipperijn J, Ried-Larsen M, Nielsen MS, Holdt AF, Grøntved A, Ersbøll AK, Kristensen PL. A longitudinal study of objectively measured built environment as determinant of physical activity in young adults: The European Youth Heart Study. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2015;12:909–914. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Simons D, Rosenberg M, Salmon J, Knuiman M, Granich J, Deforche B, Timperio A. Psychosocial moderators of associations between life events and changes in physical activity after leaving high school. Prev Med. 2015;72:30–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Small M, Bailey-Davis L, Morgan N, Maggs J. Changes in eating and physical activity behaviors across seven semesters of college: living on or off campus matters. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40:435–441. doi: 10.1177/1090198112467801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stavrakakis N, de Jonge P, Ormel J, Oldehinkel AJ. Bidirectional prospective associations between physical activity and depressive symptoms. The TRAILS Study. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Taymoori P, Berry TR, Lubans DR. Tracking of physical activity during middle school transition in Iranian adolescents. Health Educ J. 2012;71:631–641. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Telford A, Finch CF, Barnett L, Abbott G, Salmon J. Do parents' and children's concerns about sports safety and injury risk relate to how much physical activity children do? Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:1084–1088. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Van De Laar RJ, Ferreira I, Van Mechelen W, Prins MH, Twisk JW, Stehouwer CD. Lifetime vigorous but not light-to-moderate habitual physical activity impacts favorably on carotid stiffness in young adults: The amsterdam growth and health longitudinal study. Hypertension. 2010;55:33–39. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.138289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Van Dyck D, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Deliens T, Deforche B. Can changes in psychosocial factors and residency explain the decrease in physical activity during the transition from high school to college or university? Int J Behav Med. 2015;22:178–186. doi: 10.1007/s12529-014-9424-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wagnsson S, Lindwall M, Gustafsson H. Participation in organized sport and self-esteem across adolescence: the mediating role of perceived sport competence. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2014;36:584–594. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2013-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.