Abstract

Importance

Pharmacological enhancers of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) are in preclinical or early clinical development for cardiovascular prevention. Studying whether these agents will reduce cardiovascular events or diabetes risk when added to existing lipid-lowering drugs would require large outcome trials. Human genetics studies can help prioritize or deprioritize these resource-demanding endeavors.

Objective

To investigate the independent and combined associations of genetically-determined differences in LPL-mediated lipolysis and LDL-C metabolism with diabetes and coronary risk.

Design

Population-based cohort and case-cohort.

Setting

This study was conducted in the United Kingdom between 2014 and 2018.

Participants

Individual-level genetic data from 390,470 people were included.

Exposure

Six conditionally-independent triglyceride-lowering alleles in LPL, p.Glu40Lys in ANGPTL4, rare loss-of-function variants in ANGPTL3 and LDL-C lowering polymorphisms at 58 independent genomic regions, including HMGCR, NPC1L1 and PCSK9.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Odds ratio for type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease.

Results

Triglyceride-lowering alleles in LPL were associated with protection from coronary disease (~40% lower odds per standard deviation [SD] genetically-lower triglycerides) and type 2 diabetes (~30% lower odds) in people above or below the median of the population distribution of LDL-C lowering alleles at 58 independent genomic regions, HMGCR, NPC1L1 or PCSK9 (p<0.001 in all subgroups). Associations with lower risk were consistent in quintiles of the distribution of LDL-C lowering alleles and 2×2 “factorial” genetic analyses. The 40Lys variant in ANGPTL4 protected from coronary disease and type 2 diabetes in groups with genetically-higher or lower LDL-C. For a genetic difference of 0.23 SD in LDL-C, ANGPTL3 loss-of-function variants, which also have beneficial effects on LPL-lipolysis, were associated with greater protection against coronary disease than other LDL-C lowering genetic mechanisms (odds ratio from a meta-analysis of published genetic studies, 0.66, 95% CI, 0.52-0.83 for ANGPTL3 vs odds ratio, 0.90, 95% CI, 0.89-0.91 for 58 LDL-C lowering variants; pheterogeneity=0.0089).

Conclusions and Relevance

Triglyceride-lowering alleles in the LPL pathway are associated with protection against coronary disease and type 2 diabetes independently of LDL-C lowering genetic mechanisms. These findings provide human genetics evidence to support the development of agents that enhance LPL-mediated lipolysis for further clinical benefit in addition to LDL-C-lowering therapy.

Introduction

Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) is an endothelium-bound enzyme that catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the clearance of atherogenic triglyceride-rich particles.1 There is genetic evidence of a causal link between impaired LPL-mediated lipolysis and coronary artery disease. Gain-of-function genetic variants in LPL,2,3 or loss-of-function variants in its intravascular inhibitors ANGPTL3,4–6 ANGPTL42,7 or APOC38,9 are associated with lower triglyceride levels and lower coronary disease risk, while loss-of-function variants in LPL2,3,10 or its natural activator APOA511 are associated with higher triglycerides and higher coronary risk. Impaired LPL-mediated lipolysis has also been linked to insulin resistance12 and a higher type 2 diabetes risk,12–15 but the relationships of this pathway with glucose metabolism are incompletely understood.

There is growing interest around LPL-mediated lipolysis as a target for pharmacological intervention. Several new medicines that enhance LPL-mediated clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoprotein particles by directly activating LPL16,17 or by inhibiting its intravascular inhibitors6,7,18–20 are in pre-clinical7,16,17 or early clinical6,18–21 development for cardiovascular prevention. However, it is not known whether these agents will provide further benefits in addition to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) lowering therapy, which is the mainstay of lipid-lowering therapy in cardiovascular prevention. Drugs that accelerate LPL-mediated clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoprotein particles are being developed for use in addition to statins and, possibly, other LDL-C lowering agents. However, statins,22 ezetimibe23 and PCSK9 inhibitors24–27 also reduce triglyceride-rich particles and this could limit the clinical benefits and utility of LPL-enhancing agents when used in combination with these drugs.

Large-scale clinical trials and the investment of massive resources would be required to study the impact on cardiovascular outcomes of each of these LPL-enhancing agents in the context of LDL-C lowering therapy. In advance of outcome trials, human genetic approaches can provide evidence of whether or not genetically-determined differences in LPL-mediated lipolysis and LDL-C metabolism have independent contributions to cardio-metabolic disease risk, which can help prioritize or deprioritize these resource-intensive efforts.28,29

Methods

Study design

The aims of this study were: (1) to investigate associations of genetically-enhanced LPL-mediated lipolysis with cardio-metabolic risk factors, coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes (eFigure 1A); and (2) to estimate the independent and combined cardiovascular and metabolic associations of genetically-enhanced LPL-mediated lipolysis and of LDL-C lowering genetic variants (eFigure 1B-C). For the first aim, we estimated associations from summary-level genetic data including up to 672,505 individuals in non-stratified analyses (eFigure 1A). For the second aim, we used individual-level genetic data from up to 390,470 individuals to perform 2×2 “factorial” (eFigure 1B) or stratified genetic analyses (eFigure 1C). We also investigated the associations of naturally-occurring variation in the genes encoding LPL-inhibitors.

Participants and studies

In non-stratified analyses (eFigure 1A), we used genetic association data on up to 672,505 people from EPIC-InterAct,30 EPIC-Norfolk,31 UK Biobank32 and large-scale genetic consortia, including the CARDIoGRAMplusC4D,33 DIAGRAM,34 GIANT,35,36 MAGIC37,38 and GLGC consortia.39

In factorial and stratified analyses (eFigure 1B-C), we used individual-level data from up to 390,470 individuals of EPIC-InterAct, EPIC-Norfolk, and UK Biobank (Table 1). EPIC-InterAct30 is a case-cohort study of type 2 diabetes nested within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study.40 EPIC-Norfolk is a prospective cohort study of over 20,000 individuals aged 40-79 and living in the Norfolk county in the United Kingdom at recruitment.31 UK Biobank is a population-based cohort of 500,000 people aged between 40-69 years who were recruited in 2006-2010 from several centers across the United Kingdom.32 Detailed characteristics of the participants with individual level genotype data included in this study are presented in Table 1, and details about the cohorts participating in each analysis, phenotype definitions and data sources are in eNote 1 and eTable 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants of UK Biobank, EPIC-InterAct, and EPIC-Norfolk included in this study.

| Study | UK Biobank | EPIC-InterAct | EPIC-InterAct | EPIC-Norfolk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study group | Cohort | Incident type 2 diabetes | Non-cases | Cohort |

| Country | United Kingdom | Multiple European countries | Multiple European countries | United Kingdom |

| Genotyping chip | Affymetrix UK BiLEVE and UK Biobank Axiom arrays | Illumina 660w quad and Illumina CoreExome chip | Illumina 660w quad and Illumina CoreExome chip | Affymetrix UK Biobank Axiom array |

| Imputation panel | Haplotype Reference Consortium | Haplotype Reference Consortium | Haplotype Reference Consortium | Haplotype Reference Consortium, UK10K and 1000 Genomes |

| Participants, N | 352,070 | 9,400 | 11,593 | 19,157 |

| Age at baseline, mean years (SD) | 57 (8) | 55 (7) | 52 (9) | 59 (9) |

| Female sex, N (%) | 189,755 (54) | 4,754 (51) | 7,231 (62) | 10,175 (53) |

| Smoking status, current smokers N (%) | 36,464 (10) | 2,733 (29) | 3,115 (27) | 2,174 (11) |

| BMI in kg/m2, mean (SD) | 27.4 (4.8) | 29.8 (4.8) | 25.8 (4.1) | 26.3 (3.8) |

| Waist-to-hip ratio, mean (SD) | 0.87 (0.09) | 0.92 (0.09) | 0.85 (0.09) | 0.86 (0.09) |

| Systolic blood pressure in mmHg, mean (SD) | 138 (19) | 144 (20) | 132 (19) | 135 (18) |

| Diastolic blood pressure in mmHg, mean (SD) | 82 (10) | 87 (11) | 81 (11) | 83 (11) |

| LDL cholesterol in mmol/L, mean (SD) | NAa | 4.0 (1) | 3.8 (1) | 4.0 (1) |

| HDL cholesterol in mmol/L, mean (SD) | NAa | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.4) |

| Triglycerides in mmol/L, median (IQR) | NAa | 1.7 (1.2 – 2.4) |

1.1 (0.8 – 1.6) |

1.5 (1.1 – 2.2) |

Abbreviations: N, number of participants; BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not available.

Blood lipids concentrations are still being measured in the UK Biobank study and results are not currently available.

Factorial and stratified genetic analyses

The similarities between the random allocation of genetic variants at conception and that of participants in a randomized trial41 have been used as rationale to study associations of alleles in different genes to gain insights into the likely consequences of the pharmacological modulation of the gene products in a way that simulates a factorial randomized controlled trial.42,43 In this study, for each participant, we calculated a weighted LPL genetic score and a weighted LDL-C genetic score by adding the number of triglyceride-lowering LPL-alleles or LDL-C–lowering alleles at 58 LDL-C-associated genetic loci, weighted by their effect on the corresponding lipid levels. These genetic scores were dichotomized at the median value to “naturally randomize” participants into four groups: (1) reference, (2) genetically-lower triglycerides via LPL-alleles, (3) genetically-lower LDL-C via alleles at 58 independent genetic loci, or (4) both genetically-lower triglycerides via LPL-alleles and genetically-lower LDL-C via the 58 genetic loci. We studied associations with lipid traits and cardio-metabolic outcomes between groups using a 2×2 “factorial” design (eFigure 1B). Further details about this approach are in the eNote 2.

In stratified analyses (eFigure 1C), we studied the associations of LPL-alleles in quantiles of the population distribution of 58 LDL-C lowering alleles or alleles at three genes encoding the targets of current lipid-lowering therapy, including HMGCR (encoding the target of statins), NPC1L1 (ezetimibe) and PCSK9 (PCSK9 inhibitors). We considered groups above or below the median of overall and gene-specific LDL-C lowering genetic scores, as well as quintiles of the general LDL-C lowering genetic score.

Selection of genetic variants

As a proxy for genetically-enhanced LPL-lipolysis, we used six genetic variants in the LPL gene previously reported to be strongly and independently associated with triglyceride levels (p<5.0×10−08 for each variant in conditional analyses from the Global Lipids Genetics Consortium [GLGC]10; eTable 2).

In factorial or stratified analyses, as instruments for genetically-lower LDL-C we used 58 genetic variants from independent genomic regions associated with LDL-C levels in up to 188,577 participants of GLGC39 (p<5.0×10−08 for LDL-C in each region; all variants >500 kb away from each other and low linkage disequilibrium with pairwise R2<0.01; eTable 2). In sensitivity analyses, we used a subset of 22 of the 58 variants that had no association with triglycerides in GLGC39 (p>0.05). We also considered six HMGCR,43 five NPC1L142 or seven PCSK943 genetic variants previously used by Ference et al. as genetic proxies for statin, ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitor therapy42,43 (eTable 2). Quality checks of genetic data and of analyses presented in this manuscript are described in eNote 3.

Loss-of-function variants in the inhibitors of lipoprotein lipase

We estimated associations with cardio-metabolic outcomes of a low-frequency variant in ANGPTL4 (p.Glu40Lys, 40Lys allele frequency, 1.9%). The 40Lys allele disrupts the inhibitory effect of ANGPTL4 on LPL in vitro44 and is strongly associated with lower triglyceride levels (~0.27 standard deviations [SD] lower triglycerides per 40Lys allele; p=4.2×10-175) but not with LDL-C (p=0.70) in GLGC.14 The variant is also associated with protection from cardio-metabolic disease.2,7,14,45

Rare loss-of-function alleles in the LPL-inhibitor ANGPTL3 are associated with lower LDL-C and triglyceride levels,4–6 offering a unique genetic model for the combined reduction of LDL-C levels and enhancement of LPL-mediated lipolysis. Genetic studies and clinical trials show that different LDL-C-lowering mechanisms protect against coronary disease with a log-linear relationship that is observed independently of the mechanism by which this reduction is attained.42,46,47 If the association with lower risk of ANGPTL3 variants is only via lower LDL-C, one would expect their association to be the same as that of LDL-C lowering variants in other genes, for a given genetic difference in LDL-C levels. We investigated this hypothesis by meta-analyzing and modelling data from previously published genetic studies about the association of rare loss-of-function variants of ANGPTL3 with LDL-C and coronary disease risk (eNote 4).5,6

We also attempted to estimate the associations with cardio-metabolic outcomes of a rare loss-of-function variant in the APOC3 gene captured by direct genotyping in UK Biobank, but the analysis was uninformative likely due to low statistical power (eNote 5).

Statistical analysis

In non-stratified and stratified genetic analyses, associations of the six triglyceride-lowering genetic variants in LPL and outcomes were estimated using weighted generalized linear regression models that accounts for correlation between genetic variants.48 Estimates of (a) LPL-alleles to triglyceride levels associations and of (b) LPL-alleles to outcome associations were used to calculate estimates of (c) genetically-lower triglyceride levels via LPL-alleles to outcome associations. Correlation values were obtained from the LDlink software (eTable 3).49 Results were scaled to represent the beta coefficient or the odds ratio (OR) per SD in genetically-predicted triglyceride levels via LPL-alleles. Triglyceride associations are expressed in ln-transformed and standardized units.

In factorial genetic analyses (eFigure 1B), the associations of each group relative to the reference group were estimated using linear regression for plasma LDL-C and triglyceride levels, and either logistic or Prentice-weighted Cox regression (as appropriate for the study design) for coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes.

All analyses were adjusted for age, sex and genetic principal components. Analyses were conducted within each study and pooled using fixed-effect inverse variance weighted meta-analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA v14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas 77845 USA) and R v3.2.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). A two-tailed p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Associations of LPL-alleles with cardio-metabolic risk factors and outcomes

Triglyceride-lowering alleles in LPL were associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes both in combined (OR per SD genetically-lower triglycerides, 0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62-0.76; p=2.6×10-13; eFigure 2 and eTable 4) and individual-variant analyses (eFigure 3 and eTable 5). Comparisons with estimates from multiple triglyceride-lowering genetic mechanisms50 showed that this association is specific to LPL and does not reflect a general association in a protective direction of lower triglyceride levels (eNote 6 and eTable 6). Associations with lower coronary risk (OR per SD genetically-lower triglycerides, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.53-0.66; p=1.3×10-22; eFigures 2-3 and eTables 4-5) were consistent with previous studies.10

Triglyceride-lowering LPL-alleles were associated with lower fasting insulin, fasting plasma glucose and a lower BMI-adjusted WHR (i.e. a more favorable fat distribution; p=7.9×10-05; eFigure 2), a novel association consistent with evidence of the preferential LPL-mediated lipid distribution to peripheral, rather than central adipocytes.51

Independent and combined associations of LPL-alleles and LDL-C lowering alleles

In factorial genetic analyses, people naturally-randomized to genetically-lower triglycerides via LPL had lower triglycerides but similar LDL-C levels compared to the reference group (eFigure 4). The association with lipid levels was additive to that of LDL-C lowering alleles (eFigure 4), which were also associated with lower triglyceride levels, consistent with the observed reduction in triglyceride-rich particles observed in people taking statins,22 ezetimibe23 or PCSK9 inhibitors.24–27

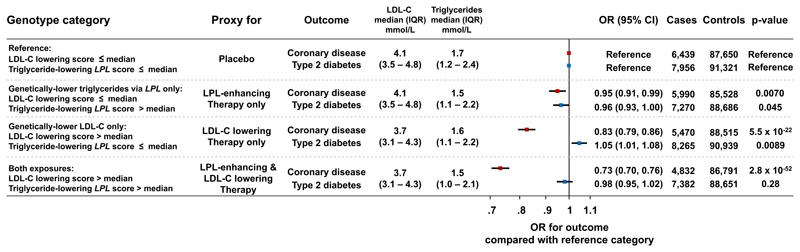

People naturally randomized to lower LDL-C levels, lower triglycerides via LPL or both had a lower risk of coronary artery disease compared to the reference group (Figure 1), with lowest odds in people naturally randomized to both genetic exposures (odds ratio, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.70-0.76; p=2.8×10-52; Figure 1). In this group, the odds ratio for coronary disease compared to the reference group was a further 7% lower than what expected on the basis of the association of the two exposures alone (95% CI, 12%-1% lower odds ratio; pinteraction=0.018). However, stratified analyses in groups above or below the median or in quintiles of the distribution of LDL-C lowering alleles were not consistent with an interaction (Figures 2A and 3; pinteraction>0.05).

Figure 1. Associations with cardio-metabolic disease outcomes in 2×2 “factorial” genetic analyses.

The figure shows associations with risk of coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes for each group compared to the reference group. Analyses include individual-level genetic data from 390,470 participants of the UK Biobank, EPIC-Norfolk and EPIC-InterAct studies. Median values and interquartile ranges for lipid levels are from the EPIC-Norfolk study. Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

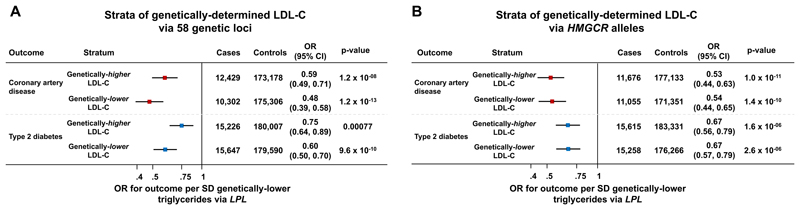

Figure 2. Associations of triglyceride-lowering LPL alleles with cardio-metabolic disease outcomes in individuals above or below the median of the population distribution of genetic variants at 58 LDL-C associated genetic loci (Panel A) or HMGCR (Panel B).

Analyses include individual-level genetic data from 390,470 participants of the UK Biobank, EPIC-Norfolk and EPIC-InterAct studies. Abbreviations: LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

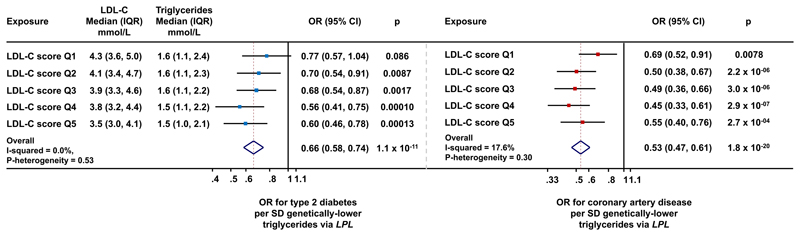

Figure 3. Associations of triglyceride-lowering LPL alleles with cardio-metabolic disease outcomes within quintiles of the population distribution of genetic variants at 58 LDL-C associated genetic loci.

Data are from the UK Biobank, EPIC-Norfolk and EPIC-InterAct studies. Median values and interquartile ranges for lipid levels are from the EPIC-Norfolk study. Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Q, quintile.

People naturally-randomized to lower LDL-C had a higher risk of type 2 diabetes compared to the reference group (Figure 1), consistent with previous studies.43,50,52–55 However, people naturally randomized to both genetic exposures had a similar risk of type 2 diabetes compared to the reference group (Figure 1), as the association of LPL-alleles with lower risk “cancelled-out” the risk-increasing association of LDL-C lowering alleles. Consistently, triglyceride-lowering LPL alleles were strongly associated with lower diabetes risk also in people with genetically-lower LDL-cholesterol (Figure 2A).

In stratified analyses, triglyceride-lowering LPL-alleles were strongly and consistently associated with protection from diabetes and coronary disease in subgroups of people above or below the median of the population distribution of the 58 LDL-C lowering alleles (Figure 2A), 22 of the 58 LDL-C lowering alleles that were not associated with triglyceride levels in GLGC (eTable 7), HMGCR, NPC1L1 or PCSK9 alleles (p<0.001 for all comparisons; Figure 2 and eFigure 5). Associations of LPL-alleles with lower risk were consistent in quintiles of the population distribution of the 58 LDL-C lowering alleles (Figure 3 and eFigure 6).

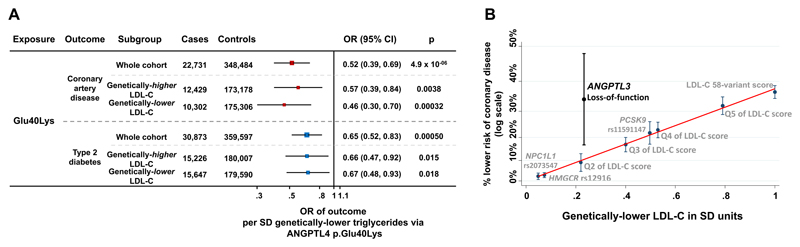

Evidence from ANGPTL4 and ANGPTL3 genetic variants

The ANGPTL4 p.Glu40Lys variant was associated with protection from coronary disease and diabetes, with effect estimates nearly identical to the ones of triglyceride-lowering alleles in LPL for a given genetic difference in triglycerides (Figure 4A, eFigure 2). Associations were consistent in people above or below the median of the 58-variant LDL-C lowering genetic score (Figure 4A). Also, the 40Lys allele was associated with a more favorable fat distribution in UK Biobank (SD of BMI-adjusted waist-to-hip ratio per allele, -0.024; standard error, 0.0086; p=0.0046; N=350,450).

Figure 4. Associations of loss-of-function alleles in ANGPTL4 and ANGPTL3.

Panel A shows associations with cardio-metabolic disease outcomes of the ANGPTL4 p.Glu40Lys loss-of-function allele in the UK Biobank, EPIC-Norfolk and EPIC-InterAct studies. Associations are scaled to represent the odds ratio per standard deviation genetically-lower triglyceride levels. Data are from the UK Biobank, EPIC-Norfolk and EPIC-InterAct studies. Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SD, standard deviation. Panel B shows associations with protection against coronary disease for different genetic exposures associated with lower LDL-C levels. A clear log-linear relationship between genetic-difference in LDL-C and association with lower risk is observed for several mechanisms, while ANGPTL3 loss-of-function variants are outliers in this relationship. The graphs display the % lower risk for coronary disease (log scale) and the difference in standard deviations of genetically-lower LDL-C. For individual variants the estimates represent per-allele differences; for quintiles of the LDL-C score the difference compared to the bottom quintile; for the overall genetic score the difference per standard deviation genetically-lower LDL-C; for ANGPTL3 variants the difference in carriers compared to non-carriers. Abbreviations: Q, quintile; SD, standard deviation; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

In previous sequencing studies, carrying a rare loss-of-function variant in ANGPTL3 has been associated with 0.4 mmol/L (36 mg/dL) lower triglycerides and 0.23 SD lower LDL-C (~0.23 mmol/L or 9 mg/dL).6 In this study, for variants at HMGCR, NPC1L1, PCSK9 and for the 58-variant LDL-C lowering genetic score, a genetic difference of 0.23 SD in LDL-C was consistently associated with ~10% lower odds of coronary disease (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.89, 0.91; I2=0%, pheterogeneity in effect estimates=0.86; eFigure 7). In a meta-analysis of published genetic studies5,6 on rare loss-of-function variants in ANGPTL3 we found an association with ~34% lower odds of coronary disease (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.52-0.83; p=0.00046; I2=0%, pheterogeneity=0.99; eFigure 8). For a given genetic-difference in LDL-C, the association of ANGPTL3 variants with lower coronary disease risk was stronger than that of the LDL-C lowering genetic score (pheterogeneity in effect estimates=0.0089; Figure 4B, eFigure 7 and eTable 8).

Discussion

By analyzing individual-level genetic data in close to 400,000 people, we provide strong evidence that triglyceride-lowering alleles in the lipoprotein lipase pathway and LDL-C lowering genetic mechanisms independently contribute to a lower risk of coronary artery disease. This is of relevance to the future clinical development and positioning of LPL-enhancing drugs, given that these agents are being developed for use in addition to statins and other existing LDL-C lowering drugs. Because the LDL-C lowering alleles studied here included those at genes encoding the targets of current LDL-C lowering therapy, this study supports the hypothesis that pharmacologically enhancing LPL-mediated lipolysis is likely to provide further cardiovascular benefits in addition to existing LDL-C lowering agents.

By studying the interplay of these pathways with a study design that is directly relevant to the future clinical development of LPL-enhancing agents, this study adds to previous analyses which have investigated the impact on cardio-metabolic disease of LPL-pathway alleles2,3,10,12,14 or LDL-C lowering alleles separately.50,53,56–58 The independent associations of genetically-enhanced LPL-mediated lipolysis and of mechanisms that lower LDL-C via PCSK9, NPC1L1 and HMGCR provide direct support to the development of direct enhancers of LPL16,17 for use in the context of existing LDL-C-lowering therapy, but also provide general support for other agents that enhance LPL activity via inhibition of its natural inhibitors in this therapeutic context.6,7,18–21

We also investigated variation at two intravascular inhibitors of LPL, ANGPTL4 and ANGPTL3, making two important observations. First, the level of protection from diabetes and coronary disease associated with ANGPTL4 p.Glu40Lys is the same as that of LPL alleles, for a given genetic-difference in triglycerides, and is consistent across the population distribution of LDL-C lowering alleles. These findings are relevant for drugs that inhibit ANGPTL47 or directly enhance LPL by disrupting the inhibitory activity of ANGPTL4.17 Second, rare loss-of-function variants in ANGPTL3 are associated with a greater level of protection from coronary disease than other genetic mechanisms, for a given genetic difference in LDL-C. This result suggests that ANGPTL3 inhibition may be an exception to the “LDL paradigm”, the mechanism-independent log-linear relationship between LDL-C lowering and coronary disease protection that has been consistently found in genetic studies and clinical trials.42,46 In phase 1 trials, ANGPTL3 inhibitors reduced LDL-C by amounts similar to or greater than currently approved LDL-C lowering drugs.6,20,21 Our findings suggest that ANGPTL3 inhibitors may be more effective than current agents for a given magnitude of LDL-C reduction.

Triglyceride-lowering LPL-alleles were also associated with protection against type 2 diabetes. The strong and consistent association in a protective direction of multiple independent LPL-alleles found in our study extends and reinforces previous reports by us and others limited to the rs180117712 and rs32812,14,15 alleles. We also provide evidence consistent with the association with lower incidence of diabetes being specific to the LPL pathway and not being a general association of lower triglycerides. In factorial analyses, this association was in a protective direction with a magnitude equivalent to the association of LDL-C lowering alleles with increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Therefore, our data suggest that enhancing LPL activity may also ameliorate glucose metabolism, while further reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease, also in people taking LDL-C lowering therapy.

Triglyceride-lowering alleles in LPL were also associated with greater insulin sensitivity, lower glucose levels, and a more favorable body fat distribution pattern, strengthening the link of this pathway with insulin and glucose metabolism.12, 45 The novel finding from this study of robust associations of triglyceride-lowering LPL alleles and ANGPTL4 p.Glu40Lys with a lower waist-to-hip ratio is consistent with the known role of LPL as a lipid-buffering molecule51 and corroborates the notion that the association of this pathway with insulin sensitivity and lower diabetes risk may be due at least partially to improved capacity to preferentially store excess calories in peripheral adipose compartments.12

A number of assumptions and possible limitations of the genetic approach used in this study are worth considering when interpreting its results. “Mendelian randomization” generally assumes that genetic variants are associated with the endpoint exclusively via the risk factor of interest.41 In this case, the risk factor of interest is genetic differences in LPL-mediated lipolysis of which triglyceride levels are a proxy and therefore the association of LPL-alleles with different metabolic risk factors and diseases does not invalidate the approach. The consequences of modest genetically-determined differences in LPL-mediated lipolysis over several decades, as assessed in this study, may differ from the short-term pharmacological modulation of LPL-mediated lipolysis in randomized controlled trials or clinical practice. While our analyses show a strong association of LPL-alleles with diabetes and coronary disease, this does not necessarily mean that pharmacologically enhancing lipolysis over a short time will yield clinically-relevant changes in future risk of coronary disease or new-onset diabetes in high-risk adults for whom these agents are being developed. Therefore, the effect estimates from our genetic analysis reflect a life-long exposure to genetic differences in LPL-mediated lipolysis, and should not be interpreted as an exact prediction of the magnitude of the clinical effect for studies of the short-term pharmacological modulation of this pathway.

Conclusions

Triglyceride-lowering alleles in the LPL pathway are associated with protection against coronary disease and type 2 diabetes independently of LDL-C lowering genetic mechanisms. These findings provide human genetics evidence to support the development of agents that enhance LPL-mediated lipolysis for further clinical benefit in addition to LDL-C-lowering therapy.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question: Are genetically-determined differences in lipoprotein lipase (LPL) mediated lipolysis and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) lowering pathways independently associated with risk of coronary disease and diabetes?

Findings: Triglyceride-lowering alleles in LPL or its inhibitor ANGPTL4 were associated with lower risk of coronary artery disease (~40% lower odds per standard deviation genetically-lower triglycerides) and type 2 diabetes (~30% lower odds) in a consistent fashion across quantiles of the population distribution of LDL-C lowering alleles. For a given genetic difference in LDL-C, the association with protection against coronary disease conveyed by rare loss-of-function variants in ANGPTL3, which are associated with lower LDL-C and enhanced LPL-lipolysis, was greater than that conveyed by other LDL-C lowering genetic mechanisms.

Meaning: LPL-mediated lipolysis and LDL-C lowering mechanisms independently contribute to the risk of coronary disease and diabetes, which supports the development of LPL-enhancing agents for use in the context of LDL-C lowering therapy.

Acknowledgement

This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank resource. This study has been conducting using data from the EPIC-InterAct and EPIC-Norfolk studies. This study was funded by the United Kingdom’s Medical Research Council through grants MC_UU_12015/1, MC_PC_13046, MC_PC_13048 and MR/L00002/1. This work was supported by the MRC Metabolic Diseases Unit (MC_UU_12012/5) and the Cambridge NIHR Biomedical Research Centre and EU/EFPIA Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking (EMIF grant: 115372). EPIC-InterAct Study funding: funding for the InterAct project was provided by the EU FP6 programme (grant number LSHM_CT_2006_037197). S. B. is supported by a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (Grant Number 204623/Z/16/Z). D. B. S. is supported by the Wellcome Trust grant n. 107064. M. McC. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator and is supported by the following grants from the Wellcome Trust: 090532 and 098381. M. McC. was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) and the views expressed are those of the Author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. S. O. R. acknowleges funding from the Wellcome Trust (Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award: 095515/Z/11/Z and Wellcome Trust Strategic Award: 100574/Z/12/Z).

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help of the MRC Epidemiology Unit Support Teams, including Field, Laboratory and Data Management Teams.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

Dr. R. A. S. is an employee and shareholder of GlaxoSmithKline Plc. (GSK). Dr McCarthy received grants from Eli Lilly, Roche, AstraZeneca, Merck, Janssen, Servier, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Takeda; and honoraria from Novo Nordisk and Pfzier. Dr O'Rahilly received personal fees from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, iMed, and ERX Pharmaceuticals for serving on advisory boards and scientific panels.

References

- 1.Eckel RH. Lipoprotein lipase. A multifunctional enzyme relevant to common metabolic diseases. The New England journal of medicine. 1989 Apr 20;320(16):1060–1068. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198904203201607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myocardial Infarction Genetics and CARDIoGRAM Exome Consortia Investigators et al. Coding Variation in ANGPTL4, LPL, and SVEP1 and the Risk of Coronary Disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2016 Mar 24;374(12):1134–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sagoo GS, Tatt I, Salanti G, et al. Seven lipoprotein lipase gene polymorphisms, lipid fractions, and coronary disease: a HuGE association review and meta-analysis. American journal of epidemiology. 2008 Dec 1;168(11):1233–1246. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musunuru K, Pirruccello JP, Do R, et al. Exome sequencing, ANGPTL3 mutations, and familial combined hypolipidemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2010 Dec 02;363(23):2220–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stitziel NO, Khera AV, Wang X, et al. ANGPTL3 Deficiency and Protection Against Coronary Artery Disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017 Apr 25;69(16):2054–2063. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dewey FE, Gusarova V, Dunbar RL, et al. Genetic and Pharmacologic Inactivation of ANGPTL3 and Cardiovascular Disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2017 Jul 20;377(3):211–221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dewey FE, Gusarova V, O'Dushlaine C, et al. Inactivating Variants in ANGPTL4 and Risk of Coronary Artery Disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2016 Mar 24;374(12):1123–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3 and risk of ischemic vascular disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Jul 3;371(1):32–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.TG and HDL Working Group of the Exome Sequencing Project, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute et al. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3, triglycerides, and coronary disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Jul 3;371(1):22–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khera AV, Won HH, Peloso GM, et al. Association of Rare and Common Variation in the Lipoprotein Lipase Gene With Coronary Artery Disease. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2017 Mar 07;317(9):937–946. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Do R, Stitziel NO, Won HH, et al. Exome sequencing identifies rare LDLR and APOA5 alleles conferring risk for myocardial infarction. Nature. 2015 Feb 5;518(7537):102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature13917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lotta LA, Gulati P, Day FR, et al. Integrative genomic analysis implicates limited peripheral adipose storage capacity in the pathogenesis of human insulin resistance. Nature genetics. 2017 Jan;49(1):17–26. doi: 10.1038/ng.3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taskinen MR. Lipoprotein lipase in diabetes. Diabetes/metabolism reviews. 1987 Apr;3(2):551–570. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610030208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu DJ, Peloso GM, Yu H, et al. Exome-wide association study of plasma lipids in >300,000 individuals. Nature genetics. 2017 Oct 30;49(12):1758–1766. doi: 10.1038/ng.3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahajan A, Wessel J, Willems SM, et al. Refining the accuracy of validated target identification through coding variant fine-mapping in type 2 diabetes. Nature genetics. 2018 Apr;50(4):559–571. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0084-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsson M, Caraballo R, Ericsson M, et al. Identification of a small molecule that stabilizes lipoprotein lipase in vitro and lowers triglycerides in vivo. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2014 Jul 25;450(2):1063–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geldenhuys WJ, Aring D, Sadana P. A novel Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) agonist rescues the enzyme from inhibition by angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4) Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2014 May 01;24(9):2163–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaudet D, Brisson D, Tremblay K, et al. Targeting APOC3 in the familial chylomicronemia syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Dec 4;371(23):2200–2206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaudet D, Alexander VJ, Baker BF, et al. Antisense Inhibition of Apolipoprotein C-III in Patients with Hypertriglyceridemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2015 Jul 30;373(5):438–447. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham MJ, Lee RG, Brandt TA, et al. Cardiovascular and Metabolic Effects of ANGPTL3 Antisense Oligonucleotides. The New England journal of medicine. 2017 Jul 20;377(3):222–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaudet D, Gipe DA, Pordy R, et al. ANGPTL3 Inhibition in Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2017 Jul 20;377(3):296–297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1705994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wurtz P, Wang Q, Soininen P, et al. Metabolomic Profiling of Statin Use and Genetic Inhibition of HMG-CoA Reductase. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016 Mar 15;67(10):1200–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. The New England journal of medicine. 2015 Jun 18;372(25):2387–2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sattar N, Preiss D, Robinson JG, et al. Lipid-lowering efficacy of the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab (AMG 145) in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016 May;4(5):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ridker PM, Revkin J, Amarenco P, et al. Cardiovascular Efficacy and Safety of Bococizumab in High-Risk Patients. The New England journal of medicine. 2017 Apr 20;376(16):1527–1539. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ray KK, Landmesser U, Leiter LA, et al. Inclisiran in Patients at High Cardiovascular Risk with Elevated LDL Cholesterol. The New England journal of medicine. 2017 Apr 13;376(15):1430–1440. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leiter LA, Zamorano JL, Bujas-Bobanovic M, et al. Lipid-lowering efficacy and safety of alirocumab in patients with or without diabetes: A sub-analysis of ODYSSEY COMBO II. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism. 2017 Jul;19(7):989–996. doi: 10.1111/dom.12909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson MR, Tipney H, Painter JL, et al. The support of human genetic evidence for approved drug indications. Nature genetics. 2015 Aug;47(8):856–860. doi: 10.1038/ng.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plenge RM, Scolnick EM, Altshuler D. Validating therapeutic targets through human genetics. Nature reviews. Drug discovery. 2013 Aug;12(8):581–594. doi: 10.1038/nrd4051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.InterAct Consortium. Langenberg C, Sharp S, et al. Design and cohort description of the InterAct Project: an examination of the interaction of genetic and lifestyle factors on the incidence of type 2 diabetes in the EPIC Study. Diabetologia. 2011 Sep;54(9):2272–2282. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2182-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Day N, Oakes S, Luben R, et al. EPIC-Norfolk: study design and characteristics of the cohort. European Prospective Investigation of Cancer. British journal of cancer. 1999 Jul;80(Suppl 1):95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS medicine. 2015 Mar;12(3):e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikpay M, Goel A, Won HH, et al. A comprehensive 1,000 Genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nature genetics. 2015 Oct;47(10):1121–1130. doi: 10.1038/ng.3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris AP, Voight BF, Teslovich TM, et al. Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nature genetics. 2012 Sep;44(9):981–990. doi: 10.1038/ng.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015 Feb 12;518(7538):197–206. doi: 10.1038/nature14177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shungin D, Winkler TW, Croteau-Chonka DC, et al. New genetic loci link adipose and insulin biology to body fat distribution. Nature. 2015 Feb 12;518(7538):187–196. doi: 10.1038/nature14132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott RA, Lagou V, Welch RP, et al. Large-scale association analyses identify new loci influencing glycemic traits and provide insight into the underlying biological pathways. Nature genetics. 2012 Sep;44(9):991–1005. doi: 10.1038/ng.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manning AK, Hivert MF, Scott RA, et al. A genome-wide approach accounting for body mass index identifies genetic variants influencing fasting glycemic traits and insulin resistance. Nature genetics. 2012 Jun;44(6):659–669. doi: 10.1038/ng.2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Global Lipids Genetics Consortium. Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nature genetics. 2013 Nov;45(11):1274–1283. doi: 10.1038/ng.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riboli E, Kaaks R. The EPIC Project: rationale and study design. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. International journal of epidemiology. 1997;26(Suppl 1):S6–14. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.suppl_1.s6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. What can mendelian randomisation tell us about modifiable behavioural and environmental exposures? Bmj. 2005 May 7;330(7499):1076–1079. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7499.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ference BA, Majeed F, Penumetcha R, Flack JM, Brook RD. Effect of naturally random allocation to lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol on the risk of coronary heart disease mediated by polymorphisms in NPC1L1, HMGCR, or both: a 2 x 2 factorial Mendelian randomization study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2015 Apr 21;65(15):1552–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ference BA, Robinson JG, Brook RD, et al. Variation in PCSK9 and HMGCR and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes. The New England journal of medicine. 2016 Dec 01;375(22):2144–2153. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1604304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yin W, Romeo S, Chang S, Grishin NV, Hobbs HH, Cohen JC. Genetic variation in ANGPTL4 provides insights into protein processing and function. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009 May 8;284(19):13213–13222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900553200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gusarova V, O’Dushlaine C, Teslovich TM, et al. Genetic Inactivation of ANGPTL4 Improves Glucose Homeostasis and Reduces Risk of Type 2 Diabetes. Nature communications. 2018 Jun 13;9(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04611-z. 2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silverman MG, Ference BA, Im K, et al. Association Between Lowering LDL-C and Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Among Different Therapeutic Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2016 Sep 27;316(12):1289–1297. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.13985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jarcho JA, Keaney JF., Jr Proof That Lower Is Better--LDL Cholesterol and IMPROVE-IT. The New England journal of medicine. 2015 Jun 18;372(25):2448–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1507041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burgess S, Dudbridge F, Thompson SG. Combining information on multiple instrumental variables in Mendelian randomization: comparison of allele score and summarized data methods. Statistics in medicine. 2016 May 20;35(11):1880–1906. doi: 10.1002/sim.6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Machiela MJ, Chanock SJ. LDlink: a web-based application for exploring population-specific haplotype structure and linking correlated alleles of possible functional variants. Bioinformatics. 2015 Nov 01;31(21):3555–3557. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White J, Swerdlow DI, Preiss D, et al. Association of Lipid Fractions With Risks for Coronary Artery Disease and Diabetes. JAMA cardiology. 2016 Sep 01;1(6):692–699. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McQuaid SE, Humphreys SM, Hodson L, Fielding BA, Karpe F, Frayn KN. Femoral adipose tissue may accumulate the fat that has been recycled as VLDL and nonesterified fatty acids. Diabetes. 2010 Oct;59(10):2465–2473. doi: 10.2337/db10-0678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fall T, Xie W, Poon W, et al. Using Genetic Variants to Assess the Relationship Between Circulating Lipids and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2015 Jul;64(7):2676–2684. doi: 10.2337/db14-1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lotta LA, Sharp SJ, Burgess S, et al. Association Between Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol-Lowering Genetic Variants and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-analysis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2016 Oct 4;316(13):1383–1391. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.14568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Besseling J, Kastelein JJ, Defesche JC, Hutten BA, Hovingh GK. Association between familial hypercholesterolemia and prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2015 Mar 10;313(10):1029–1036. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swerdlow DI, Preiss D, Kuchenbaecker KB, et al. HMG-coenzyme A reductase inhibition, type 2 diabetes, and bodyweight: evidence from genetic analysis and randomised trials. Lancet. 2015 Jan 24;385(9965):351–361. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61183-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Willer CJ, Sanna S, Jackson AU, et al. Newly identified loci that influence lipid concentrations and risk of coronary artery disease. Nature genetics. 2008 Feb;40(2):161–169. doi: 10.1038/ng.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voight BF, Peloso GM, Orho-Melander M, et al. Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet. 2012 Aug 11;380(9841):572–580. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60312-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ference BA, Yoo W, Alesh I, et al. Effect of long-term exposure to lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol beginning early in life on the risk of coronary heart disease: a Mendelian randomization analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012 Dec 25;60(25):2631–2639. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.