Abstract

Background

Self-management is intended to empower individuals in their recovery by providing the skills and confidence they need to take active steps to recognise and manage their own health problems. Evidence supports such interventions in a range of long-term physical health conditions, but a recent systematic synthesis is not available for people with severe mental health problems.

Aims

To evaluate the effectiveness of self-management interventions for adults with severe mental illness (SMI).

Method

A systematic review of randomised controlled trials was conducted. A meta-analysis of symptomatic, relapse, recovery, functioning and quality of life outcomes was conducted using Revman.

Results

Thirty-seven trials were included with 5790 participants. From the meta-analysis, self-management interventions conferred benefits in terms of reducing symptoms and length of admission, and improving functioning and quality of life both at the end of treatment and at follow up. Overall the effect size was small to medium. The evidence for self-management interventions on readmissions was mixed. However, self-management did have a significant effect compared to control on subjective measures of recovery such as hope and empowerment at follow up, and self-rated recovery and self-efficacy at both time points.

Conclusion

There is evidence that the provision of self-management interventions alongside standard care improves outcomes for people with severe mental illness. Self-management interventions should form part of the standard package of care provided to people with severe mental illness and should be prioritised in guidelines: research on best methods of implementing such interventions in routine practice is needed.

Introduction

Self-management broadly encompasses the tasks required to successfully live with and manage the physical, social and emotional impact of a chronic condition.1 Currently, there is no universally accepted classification of self-management, though it commonly involves the provision of information and education on a condition and its treatment, collaboratively creating an individualised treatment plan, developing skills for self-monitoring symptoms and strategies to support adherence to treatment including medication, psychological techniques, lifestyle and social support. A rapid synthesis1 of self-management interventions revealed a robust evidence base for improvement in outcomes of long term conditions such as diabetes and asthma, and some evidence for interventions in stroke, hypertension and depression, along with the potential for reducing health care resource use. The synthesis concluded that inclusion of self-management should be a requirement for high quality care for all long term conditions.

A range of interventions badged as self-management are available for people with long term conditions falling under the umbrella of severe mental illness2 (schizophrenia spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder and major depression), but a recent systematic synthesis regarding their effectiveness is lacking. A 2002 review of interventions for this population identified four key elements that improved the course of illness of those with SMI: (i) providing psychoeducation about mental illness and its treatment; (ii) behavioural tailoring to facilitate medication adherence; (iii) developing a relapse prevention plan; and (iv) teaching coping strategies for persistent symptoms.3 More recently, an additional focus on service-user defined recovery and personal goals has been incorporated into self-management interventions. Through these elements, self-management interventions are thought to empower individuals by providing the knowledge and skills to enable them to make informed decisions to manage their own care,4 cope with symptoms and reduce susceptibility to relapse and reliance on services.3

To date, previous reviews of self-management interventions for SMI have focused on broad, non-specific self-management interventions such as psychoeducation;5,6 self-help;7 or been confined to specific diagnoses within the SMI population8 - predominantly schizophrenia or psychosis- which limits the findings’ generalisability3 and results in the exclusion of studies which have focused on broad populations of mental health service users, even though self-management interventions are currently intended for use by a broad group. A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of self-management interventions for people with SMI has not previously been available. Empowering mental health service users and supporting them in making choices about their care are increasingly given weight among the stated goals and values of mental health services and policies: self-management interventions have potential to help these goals be achieved.

The aim of the present study is to assess the effectiveness of self-management in the typical mixed populations of people with SMI such as those found in National Health Service (NHS) secondary care settings and in community mental health services in many other systems. It will look at the effect of self-management in both the short and longer term, in relation to the following pre-specified outcomes deemed important from both a commissioning and service user perspective: symptomatic recovery; relapse prevention, reduced need for hospitalisation; self-rated recovery, functioning and quality of life.

Methods

A review protocol was developed following PRISMA guidelines9 and was registered at PROSPERO (Ref: CRD42017043048).

Inclusion Criteria

The research question and inclusion criteria were formulated using the PICOS (Participant, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome and Study Design.9 This widely used framework supports formulation of focused and rigorous review questions.

Participants

Studies were included if participants were adults aged 18 years and over and diagnosed with a Severe Mental Illness (SMI),2 that is with a clinical diagnosis10 of schizophrenia spectrum disorders (schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder and psychosis), bipolar disorder, major depression or studies with mixed populations of people with these diagnoses (which included those with personality disorder) using secondary care mental health services.

Intervention

Studies were included if they featured the delivery of a “self-management intervention” directly to service users that was designed to educate and equip individuals with the skills to manage symptoms, relapses and overall psychosocial functioning.11 Self-management interventions were delivered in conjunction with treatment as usual. In order to investigate the effectiveness of self-management itself, interventions with a broader focus that included self-management as only one of the intervention components were not included in the current review, unless it was possible to ascertain the specific impact of self-management. To be considered a self-management intervention for the purposes of this systematic review the intervention had to include the following three (of the four) domains identified by Mueser and Colleagues3 as effective areas of self-management:

Psychoeducation about mental illness and its treatment (in order to make informed decisions about care);

Recognition of early warning signs of relapse and development of a relapse prevention plan;

Coping skills for dealing with persistent symptoms.

Additionally, the self-management intervention should include a recovery-focused element11 such as setting personal goals based on an individual’s own hopes for their recovery and learning how to effectively manage their illness in the context of pursuing those goals.

Strategies for medication management, the fourth domain identified by Mueser and colleagues (2002), was not considered a necessary domain for a self-management intervention to be included in the current review. Making medication management a mandatory domain was considered at odds with a recovery focused approach; however the majority of studies did include a medication management component.

Comparison

Studies employing either treatment as usual, however defined, or active controls were included in this review.

Outcome

If studies reported on any of the following prespecified outcomes they were included in the meta-analyses

Symptom-focused outcomes

Relapse (or related service use outcomes: number and length of admissions)

Recovery-focused outcomes (including measures of overall recovery processes and its components: self-empowerment and efficacy, social connectedness, hope, optimism and the pursuit of a meaningful life).12

Functioning (global)

Quality of life

Study Design

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) including cluster RCTs and factorial RCTs were considered for inclusion. Quasi randomised studies were excluded.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded if:

The intervention had a therapeutic focus beyond that of improving an individual’s self-management of their illness (e.g. cognitive remediation, cognitive behavioural therapy, basic life skills or social skills), which prevented evaluating the specific efficacy of the self-management component.

- The intervention was delivered:

-

i)to family members (either as the target recipients of the intervention or in addition to the service user participants).

- ii)

-

i)

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

A systematic search for all relevant literature was conducted using a PRISMA9 search strategy of the following databases: Medline, Embase, PsychINFO, DARE and CENTRAL from their inception until 15th May 2018. The relevant parts of a published search strategy used for the NICE Schizophrenia Guidelines16 was utilised in the current study and details are included in online data supplement 1. Abstracts were screened based on the review protocol (ML) and any uncertainties were reviewed to reach a consensus (ML & MFA). Twenty percent of the full text articles assessed for eligibility (n=82) were blindly assessed to meet inclusion and exclusion criteria (MFA & AM). The few cases of disagreement were discussed and consensus reached. Additionally, a hand search of reference lists was conducted.

All abstracts were retrieved and added to Mendeley referencing software (Version 1.16.3).

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data were extracted and reviewed in Microsoft Excel. Characteristics of the study design, the intervention, participants and outcomes for all available data at all provided time points were extracted. Authors were contacted and asked to provide any missing data. Raw outcome data extracted from papers published prior to 2012 was kindly provided by the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health from our group’s previous work with them on the development of the NICE schizophrenia guidelines. The relevant studies and outcome data provided from the original search were then extracted according to this current review protocol and checked against the original manuscripts. When a study had three arms, we followed expert guidelines17 and combined both control groups into a single group to enable pairwise comparison. Mean values were multiplied by -1 to correct for differences in the direction of scales.

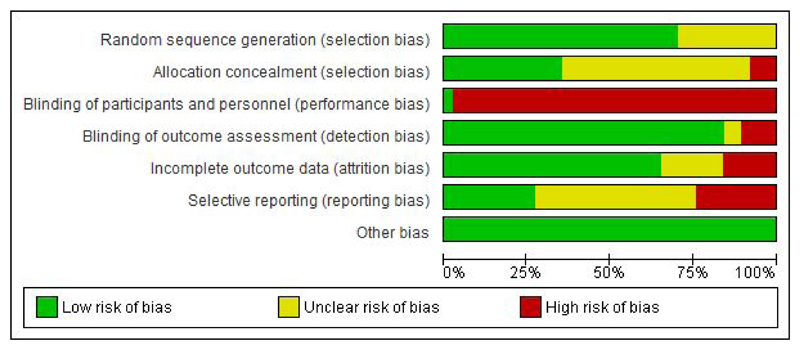

Assessment of Bias

Assessment of bias was performed by two pairs of researchers (BHS and AYU; ML and AM) using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool.17 Each study was rated for risk of bias due to sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of assessors, selective outcome reporting and incomplete data. The blinding of participants in trials of complex interventions is problematic. As such, it is assumed that blinding of participants was at high risk for all studies. Risk of bias was rated as high (weakening confidence in results), low (unlikely to seriously alter results) or unclear. Funnel plots were generated to examine publication bias in analyses with more than 10 studies.18

Statistical Analysis

Review Manager Software (Revman 5.2) was used to conduct the meta-analyses. When outcome data was reported for more than one follow-up point, the time point closest to 1-year post intervention was used. Where more than one measure was used to report the same outcome in the same study, we prioritised the primary outcome of that study or included the outcome more commonly reported by other studies in the analysis. On the rare event that a study reported both symptomatic relapse and readmission data, we included the readmission data in the analysis. Studies with treatment as usual and active control groups were analysed together.

Effect Size Calculation

Effect sizes for continuous data were calculated as standardised mean difference, Hedges’ g, and studies were weighted using inverse variance.17 For dichotomous outcomes we calculated risk ratios and combined studies using the Mantel-Haenszel method.17 All outcomes are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using random effects modelling. If reported by studies, we used intention to treat data in our analysis.

Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was assessed through visual inspection of forest plots, the p value of Chi squared test (Q) and calculating the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance.19 A p value less than 0.10 and an I2 exceeding 50% suggests substantial heterogeneity. Quantifying inconsistency across studies in this way allowed us to explore the possible reasons for heterogeneity through sensitivity analysis.

Sensitivity analyses were carried out using the one-study-removed method to examine the effect of a specific study on the pooled treatment effect. When a study was identified as substantially contributing to heterogeneity, the potential sources of clinical or methodological heterogeneity were reviewed and compared to the remaining studies to evaluate if their exclusion from the particular meta-analysis was warranted.

Results

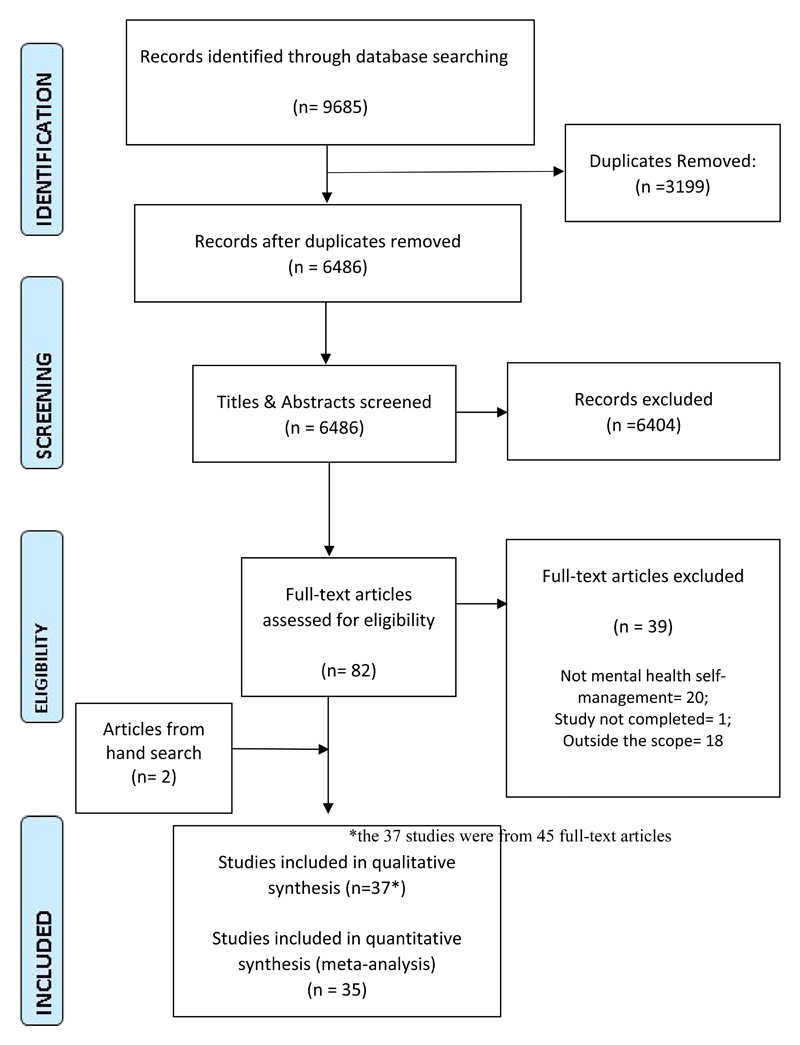

Of the 6486 potentially relevant citations, 82 papers were retrieved and assessed for inclusion (figure 1). Of these, 20 were excluded because they were not mental health self-management interventions (either they did not meet the three criteria for inclusion, or covered social skills training only); one study was not completed (protocol paper only); and a further 18 papers were outside of the scope of this review (i.e. self-management was delivered as part of another intervention, or included family members in the intervention). Two papers were included from a reference hand search. Thirty-seven randomised controlled trials (published across 45 full-text articles) were therefore included in the narrative synthesis. Two were not included in the meta-analyses20,21 as they did not report usable outcomes.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart.

Study Characteristics

A detailed breakdown of the characteristics of the studies included in this review can be found in Table 1. Studies included in this review randomised a total of 5790 participants with a median sample size of 107 (range 32 to 555). The majority of studies were conducted in high income countries (k=27), with a smaller but substantial proportion in lower or middle income countries (k = 10). The majority of studies (k=29) included participants who were currently living in the community, with eight studies recruiting from inpatient settings.

Table 1. Study population and design.

| Sample Characteristics | Comparator | Time points† (in weeks) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study ID | Setting | Age | N Total/Int | Gender % Female | Diagnosis‡ (% of sample) | Intervention/Control | Post-treatment | Follow up |

| Treatment As Usual | ||||||||

| ATKINSON 1996 22 | UK, Community | NR | 146/73 | 37 | SZ 100% | Education groups for People with Schizophrenia Control: TAU (Wait List Control) |

20 | 32 |

| BARBIC 2009 23 | Canada, Community | 45 | 33/16 | 33 | SZ 100% | Recovery Workbook Control: TAU |

12 | NR |

| CHIEN 2013 24 | Hong Kong, Community | 26 | 96/48 | 45 | SZ 100% | Mindfulness-Based Psychoeducation Program (MBPP) Control: TAU |

NR | 37; 102* |

| CHIEN 2014 25 | Hong Kong, Community | 26 | 107/36 | 43 | SZ 100% | Mindfulness-Based Psychoeducation Program (MBPP) Control: TAU & Active control (basic psychoeducation) |

25 | 52 |

| CHIEN 2017 26 | HK, China, Taiwan, Community | 26 | 342/114 | 37 | SZ 100% | Mindfulness-Based Psychoeducation Group Program (MBGP) Control: TAU & Active control (basic psychoeducation) |

25 | 50; 76*; 128 |

| COOK 2011 27–29 | USA, Community | 46 | 555/276 | 66 | SZ: 21% BP: 38% MDD: 25%; Other: 15% |

Wellness Recovery Action Planning (WRAP) Control: TAU |

14 | 40 |

| COOK 2012 30,31 | USA, Community | 43 | 428/212 | 56 | SZ: 21%; BP:40%; MDD:18%; Other: 8.6% |

Building Recovery of Individual Dreams and Goals through Education and Support (BRIDGES) Control: TAU |

14 | 40 |

| DALUM 2018 32,33 | Denmark, Community | 43 | 198/99 | 45 | SZ: 76%; BP: 24% | Illness Management and Recovery program Control: TAU |

39 | NR |

| FARDIG 2011 34 | Sweden Outpatient | 40 | 41/21 | 46 | SZ 100% | Illness Management and Recovery program Control: TAU |

39 | 91 |

| HASSON 2007 35 | Israel Inpatient | 35 | 210/119 | 35 | SZ: 84%; BP: 3%; P: 3%; Other: 3% |

Illness Management and Recovery program Control: TAU |

35 | NR |

| LEVITT 2009 36 | USA, Community | 54 | 104/54 | 37 | SZ: 32%; BP:12%; P:6%; MDD:43; Other: 7% |

Illness Management and Recovery program (IMR) Control: TAU (Wait List Control) |

22 | 72 |

| LIN 2013 37 | Taiwan, Inpatient | 35 | 97/48 | 36 | SZ 100% | Adapted Illness Management and Recovery program (IMR) Control: TAU |

3 | 7 |

| MONROE-DEVITA 2018 38 | USA, Community | 44 | 101/53 | 41 | SZ:81%; BP: 19% | Illness Management and Recovery program Control: TAU (Assertive Community Treatment) |

26; 52* | NR |

| PERRY 1999 39 | UK, Outpatient | 45 | 69/34 | 68 | BP 100% | Teaching patients with bipolar disorder to identify early symptoms of relapse and obtain treatment Control: TAU |

NR | 26, 52*, 78 |

| SAJATOVIC 2009 40 | USA, Community | 41 | 164/84 | 62 | BP 100% | Life Goals Program Control: TAU |

NR | 13; 26; 52* |

| SALYERS 2010 41 | USA, Community | 42 | 324/183 | 46 | P: 55%; BP:10%; Other:17; missing: 18% |

Illness management and Recovery program (IMR) Control: TAU |

52 | 104 |

| SHON 2002 42 | Korea, Outpatient | 33 | 40/20 | 42 | SZ: 55%; P: 15% Other: 29% | Self-Management education program Control: TAU |

12 | NR |

| SMITH 2011 43 | UK, Community | 44 | 50/24 | 62 | BP 100% | Beating Bipolar Control: TAU |

NR | 43 |

| TAN 2017 44 | Singapore | 44 | 50/25 | 62 | SZ: 86%; BP: 8%; MDD: 2%; other: 4% | Illness management and Recovery program (IMR) Control: TAU |

26; 52* | 104 |

| TODD 2014 45,46 | UK, Community | 43 | 122/61 | 72 | BP 100% | Living with Bipolar (LWB) Control: TAU (Wait List Control) |

13; 26* | NR |

| TORRENT 2013 47 | Spain, Outpatient | 40 | 268/82 | NR | BP 100% | Psychoeducation + TAU (used in Colom 2003) Study had 3 arms (intervention in original study Functional Remediation) Control: TAU |

21 | NR |

| VAN GESTELTIMMERMANS 2012 48 | Netherlands, Outpatient | 44 | 333/168 | 66 | PD: 31% P: 33%; other: 36% | Intervention: “Recovery Is Up to You” Control: TAU |

13 | 26 |

| VREELAND 2006 49 | USA, Outpatient | NR | 71/40 | 55 | SZ 100% | Team Solutions Control: TAU |

24 | NR |

| WANG 2016 50 | Hong Kong, Community | 24 | 138/46 | 48 | SZ 100% | Mindfulness-Based Psychoeducation Group Program (MBGP) Control: TAU & Active control (basic psychoeducation) |

25 | 50 |

| ZHOU 2014 51 | China, Community | 35 | 201/103 | 47 | SZ 100% | Modules of the UCLA Social & Independent Living Skills Program Control: TAU |

26 | 130 |

| Active Control | ||||||||

| ANZAI 2002 52 | Japan, Inpatient | 47 | 32/16 | 25 | SZ 100% | Social and Independent Living Skills Program-Community Re-entry Module Active Control-Conventional occupational rehabilitation program |

9 | 52 |

| CHAN 2007 53 | Hong Kong, Inpatient | 36 | 81/44 | 0 | SZ 100% | Transforming Relapse and Instilling Prosperity (TRIP) Active Control - traditional ward occupational therapy (WOT) program |

NR | 54 |

| COLOM 2003 54,55 | Spain, Outpatient | NR | 120/60 | 63 | BP 100% | Psychoeducation + TAU Active Control: Unstructured support group |

21 | 104*; 260 |

| COOK 2013 56 | USA, Community | 46 | 143/72 | 50 | SZ: 26%; BP 31%; MDD:27%; Other: 16% |

Wellness Recovery Action Planning (WRAP) Active Control: Choosing Wellness: Healthy Eating Curriculum 9x2.5hr sessions |

9 | 35 |

| ECKMAN 1992 20 | USA, Outpatient | 40 | 41/20 | 0 | SZ 100% | Social and Independent Living Skills Program-Medication and Symptom Self-management modules Active Control: Supportive Group Psychotherapy |

26 | 78 |

| KOPELOWICZ 1998 21,57 | USA, Inpatient | 35 | 59/28 | 29 | SZ 100% | Community re-entry program Active Control: Occupational therapy group |

NR | 5 |

| PROUDFOOT 2012 58,59 | Australia, Outpatient | NR | 419/139 | 70 | BP 100% | Online Bipolar Education Program (BEP) + email support from expert patients known as Informed Supporters Active Control: Online Bipolar Education Program (BEP) |

NR | 26 |

| SALYERS 2014 60 | USA, Community | 48 | 118/60 | 20 | SZ: 100% | Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) Active Control: unstructured problem-solving group |

39 | 78 |

| SCHAUB 2016 61 | Germany, Inpatient | 34 | 196/100 | 47 | SZ: 96%; P:4% | Group-based Coping Oriented Program (COP) Active Control: Supportive group treatment |

8 | 52*; 104 |

| WIRSHING 2006 62 | USA, Inpatient | 46 | 94/NR | 2 | SZ 100% | Modified Community Re-Entry Program (CREP) Active Control: Illness Education Class |

NR | 53 |

| XIANG 2006 63 | China, Outpatient | 39 | 96/48 | 51 | SZ 100% | Social and Independent Living Skills Program-Community re-entry module Active Control: Supportive counselling |

8 | 33 |

| XIANG 2007 64 | China, Inpatient | 39 | 103/53 | 53 | SZ 100% | Social and Independent Living Skills Program-Community re-entry module Active Control: Group psychoeducation program |

4 | 26; 56*; 78; 108 |

Time point used in meta-analysis.

Time point of data collection in weeks post randomisation.

Abbreviations: INT: Self-management Intervention group; SZ: schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; BP: bipolar disorder; P: psychosis; MDD: major depressive disorder; PD: personality disorder. NR: Not reported. TAU: Treatment as Usual. Int: intervention.

The mean age of participants was 40 years and 44% were female. In relation to clinical diagnosis, 18 studies included only participants with schizophrenia spectrum disorder and seven included only those with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. The remaining 12 included mixed populations of participants with schizophrenia, psychosis, bipolar, major depressive disorder and personality disorder in contact with secondary mental health services.

Across the 37 studies, self-management interventions ranged broadly in duration from 1 to 52 weeks (median duration 12 weeks). Likewise, face-to-face/group contact time also ranged widely from 4 to 96 hours (median 23 hours). Most interventions were delivered in a group format, and facilitated by clinicians (k=25) or peers (k=5). The remaining interventions were delivered to participants individually, either as an online, computer-based intervention (k=2), by a clinician (k=2) or by peer (k=1). Finally, two studies used a combination of group and individual sessions facilitated by clinician. All interventions were delivered from a manualised protocol, however the depth, detail and fidelity of the intervention to the manual was not always reported in detail. All interventions were delivered in addition to treatment as usual provided in the respective settings.

Table two provides a detailed breakdown of the studies reviewed, organised by a preliminary typology of self-management interventions developed as part of this review (further details in DS2).

Controls

Self-management interventions were compared to treatment as usual (TAU) in 19 studies, waiting list control conditions in three studies and the remaining 12 had active control conditions such as group counselling, occupational therapy or psychoeducation (Table 2). A further three were multi-arm studies with active and TAU control groups.

Table 2. Intervention characteristics organised by proposed typology.

| Study ID | Format | Facilitator | # Sessions | Duration (wks) | Session Length (hrs) | Dose (hrs)† | Intervention Name & Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illness Management and Compliance Interventions | |||||||

| ATKINSON 1996 22 | Group | Clinician | 20 | 20 | 1.5 | 30 |

Education group Sessions alternated between an information session (short presentation and discussion) followed by a problemsolving session. Patients were given a manual outlining the content of the sessions, which included: The meaning of schizophrenia to the individual, Current understandings and treatment for schizophrenia, identifying early signs of relapse and problem solving around managing relapse, symptoms, medication & side effects. Problem solving around relationships with friends and family, teaching social skills and stress management, and rehabilitation and linking in to community resources. |

| CHAN 2007 53 | Group | Clinician | 10 | 2 | 0.8 | 8 |

Transforming Relapse and Instilling Prosperity (TRIP) Utilizes strategies from IMR however is not a direct derivative of the program. TRIP is an intensive, ward-based illness management program aims to decrease treatment non-compliance and improve patient's insight and health through didactic teaching of information about their illness and open discussion of adaptive life and coping skills. Sessions cover two categories i) illness orientated (mental health, medication management, relapse prevention planning, symptom management) and ii) health orientated (emotion management, rehabilitation resources, healthy living, stress management). |

| DALUM 2018 32,33 | Group | Clinician | 39 | 39 | 1 | 39 |

Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) Program Follows the standardized curriculum-based approach of IMR as described below in Fardig 2011 but with an additional 11th module on healthy living lifestyles. |

| FARDIG 2011 34 | Group | Clinician | 40 | 40 | 1 | 40 |

Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) Program Is a clinician led, curriculum-based program for service users with SMI. Teaches evidence-based techniques for improving illness self-management: psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioural approaches to medication adherence, relapse prevention, social skills training (e.g., to enhance social support), coping skills training (e.g., for persistent symptoms). Overall aim is to help clients learn about mental illnesses and strategies for treatment; decrease symptoms; reduce relapses and rehospitalisation; and make progress toward goals and toward recovery. |

| HASSON 2007 35 | Group | Clinician | 35 | 35 | 1 | 35 |

Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) Program Follows the standardized curriculum-based approach of IMR. Educational handouts that are a central part of the Illness Management and Recovery program were translated into Hebrew and adapted for use in Israel. |

| LEVITT 2009 36 | Group | Clinician | 40 | 20 | 1 | 40 |

Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) Program The standard IMR program was delivered to those living in supportive housing. |

| LIN 2013 37 | Group | Clinician | 6 | 3 | 1.5 | 9 |

Adapted Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) Program Adapted IMR to fit in-patient acute care setting with the primary focus on symptom and medication management, while maintaining a recovery perspective. The adapted IMR program was based on three abbreviated modules from the original IMR program: Practical Facts about Schizophrenia, Using medication Effectively, and Coping with Problems and Persistent Symptoms. The IMR sessions usually started during the third week of hospitalization. Individuals who were discharged from the hospital before completing the adapted IMR program were invited to continue with the same IMR group until they had completed it. Brief essays about recovery written by individuals who had completed the adapted IMR program were also included. |

| MONROE-DEVITA 2018 38 | Group & individual | Clinician | 52 | 52 | 1 | 52 |

Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) Program This study assessed the effectiveness of IMR when delivered to those receiving Assertive Community Treatment. Follows the standardized curriculum-based approach of IMR but with an additional 11th module on healthy living lifestyles. |

| SALYERS 2010 41 | Individual and group | Clinician + Peer | 43 | 43 | 1 | 43 |

Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) Program This study assessed the effectiveness of IMR when delivered to those receiving Assertive Community Treatment. |

| SALYERS 2014 60 | Group | Clinician | 39 | 39 | 1 | 39 |

Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) Program Standard program |

| SHON 2002 42 | Group | Clinician | 12 | 12 | 1 | 12 |

Medication and Symptom Management Education program Sessions covered the following key areas: six sessions covered introduction of the psychiatric disorders; recognising symptoms and a variety of coping strategies, 3 sessions reinforcing knowledge concerning medication use and side effects, and 3 sessions covering relapse warning symptoms and coping skills and prevention strategies. Utilised a range of teaching, video vignettes, and small group discussions. |

| TAN 2017 44 | Group | Clinician | 26 | 52 | 1 | 26 |

Adapted Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) Program Eight of the ten IMR modules were used and adapted to the local setting. The two excluded modules covered the US mental health system and addiction and were deemed not applicable to this setting. |

| VREELAND 2006 49 | Group | Clinician | 96 | 24 | 1 | 96 |

Team Solutions Program Group based intervention consisting of three, eight-week modules covering the following topics and workbooks: i) Understanding Your Illness and Recovering From Schizophrenia; ii) Understanding Your Treatment and Getting the Best Results From Your Medication; and iii) Helping Yourself Prevent Relapse and Avoiding Crisis Situations. This program was developed by pharmaceutical company Elli Lily. |

| Bipolar specific illness management | |||||||

| COLOM 2003 54,55 | Group | Clinician | 21 | 21 | 1.5 | 32 |

Manual de Psicoeducacion en Tastornos Bipolares Aims to prevent recurrences and reduce time spent ill. Addresses four main issues: illness awareness, treatment compliance, early detection of prodromal symptoms and recurrences and life style regularity through talk on topic of session, exercise related to topic and active discussion. |

| TORRENT 2013 47 | Group | Clinician | 21 | 21 | 1.5 | 31.5 |

Psychoeducation based on Manual de Psicoeducacion en Tastornos Bipolares This psychoeducation intervention (based on Colom, 2003) aimed to prevent recurrences of bipolar illness by improving four main issues: illness awareness, treatment adherence, early detection of prodromal symptoms of relapse, and lifestyle regularity. Note: study has three arms-Functional remediation, psychoeducation and treatment as usual. Functional remediation arm was not included in this analysis as it does not meet inclusion criteria. |

| SAJATOVIC 2009 40 | Group | Clinician | 6 | 6 | 1.25 | 7.5 |

Life Goals Program The Life Goals Program (LGP) is a manualised, structured group psychotherapy program for individuals with bipolar disorder. It is based on behavioural principles from social learning and self-regulation theories and focuses on systematic education and individualized application of problem solving in the context of mental disorder to promote illness self-management. LGP is organized in two phases which cover illness education, management, and problem solving. Phase I is the core psychoeducational intervention. The optional phase II group sessions address goal setting and problem solving in an unstructured format. |

| SMITH 2011 43 | Individual | Computer | 8.5 | 17 | NR | N/A |

Beating Bipolar The key areas covered in the package are: (i) the accurate diagnosis of bipolar disorder; (ii) the causes of bipolar disorder; (iii) the role of medication; (iv) the role of lifestyle changes; (v) relapse prevention and early intervention; (vi) psychological approaches; (vii) gender-specific considerations, and (viii) advice for family and carers. Online modules were required to be completed in sequential order and throughout the trial there was an opportunity for participants in the intervention group to discuss the content of the material with each other within a secure, moderated discussion forum. |

| TODD 2014 45,46 | Individual | Computer | 10 | 26 | NR | N/A |

Living with Bipolar (LWB) LWB is an online interactive recovery informed self-management intervention, broadly based on the principles of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and psychoeducation. The intervention aims to help people to: increase their knowledge, self-esteem and self-efficacy around managing bipolar in order to pursue personally meaningful recovery goals. Ten interactive modules were developed: (1) Recovery & Me;(2) Bipolar &Me; (3) Self-management &Me; (4) Medication & Me; (5) Getting to Know Your Mood Swings; (6) Staying well with Bipolar; (7) Depression & Me; (8) Hypomania & Me; (9) Talking about my diagnosis; and (10) Crisis &Me. Worksheets were used to enhance learning and personalise the content, and could be down- loaded or printed out. Case studies and worked examples, written by service users were used extensively to reduce perceived isolation through shared experience. A mood checking tool was available for participants to help them identify major changes in their mood. Participants receive information about the most appropriate modules, given their mood symptoms. In line with the recovery agenda participants were given access to all aspects of the intervention and encouraged to use it as and when they felt appropriate. |

| PROUDFOOT 2012 58,59 | Individual | Computer and Peer email | 8 | 8 | 0.5 | 4 |

Online Bipolar Education Program (BEP) + Informed Supporters (email support from expert patients) The online psychoeducation program consisted of topics covering causes of bipolar disorder, diagnosis, medications, psychological treatments, omega-3 for bipolar disorder, wellbeing plans, and the importance of support networks. It was supplemented by email-based coaching and support from ‘Informed Supporters' (i.e. peers) to answer specific questions or to provide examples of how to apply the education material to their everyday lives. Emails focused on effective self-management across three domains: medical, emotional and role management, and were linked to the content of the online psychoeducation program. Questions of a clinical nature were referred to suitable clinicians. |

| PERRY 1999 39 | Individual | Clinician | 11.97 | 9 | 0.75 | 9 |

Teaching patients with bipolar disorder to identify early symptoms of relapse and obtain treatment Treatment occurred in two stages: collaboratively exploring previous relapses and training the patient to systematically identify the idiosyncratic nature and timing of their prodromal symptoms of manic or depressive relapse. Diaries were kept to distinguish symptoms associated with normal mood variation from prodromes. Once prodromes had been recognised by the patient, an action plan was created and rehearsed (such as ways to seek early treatment from a professional). The full relapse plan of warning and action stage prodromal symptoms for manic and depressive relapse with the plan for seeking treatment was recorded on a card in laminated plastic, which was carried by the patient. |

| Transition to Community from Ward | |||||||

| ANZAI 2002 52 | Group | Clinician | 18 | 9 | 1 | 18 |

SILS - Community Re-entry Module The Community Re-entry Module consists of sessions on medication management, warning signs of relapse and how to develop and implement an emergency plan to deal with relapse, how to find and secure housing and continuing psychiatric care in the community, and how to reduce stress and promote coping after discharge. The conventional program emphasizes arts and crafts, reality-orientation groups, and work assignments in the hospital. |

| ECKMAN 1992 20 | Group | Clinician | 52 | 26 | 1.5 | 78 |

SILS- Medication and Symptom management modules Utilised two modules from the UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills Program. Medication and Symptom Self-management modules |

| KOPELOWICZ 1998 21,57 | Group | Clinician | 8 | 1 | 0.75 | 6 |

SILS - Community re-entry program Based on the UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills Modules and modified for use in the rapid-turnover, “crisis” operations of a typical acute psychiatric inpatient facility. Sessions focused on preparing participants for discharge through teaching knowledge and skills to understand their disorders and the medications that control it, to develop an aftercare treatment plan by identifying problems, specifying remedial and maintenance services, and linking with service providers, teaching skills to avoid illicit drugs, cope with stress, organize a daily schedule, and make and keep appointments with service providers. |

| ZHOU 2014 51 | Group | Clinician | 26 | 26 | 2 | 52 |

SILS- Medication and Symptom management modules The Medication Management and Symptom Management Modules of UCLA program were delivered. Additionally, at the end of the intervention, participants were given a self-management check-list journal (which monitored medication adherence, sleep, side effects, residual symptoms and signs of relapse) and the main caregiver was asked to provide guidance on the process. Participants in the intervention group attended monthly self-management group meetings (for 24 months) where community mental health workers checked and evaluated their journals. |

| WIRSHING 2006 62 | Group | Clinician | 8 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

Modified Community Re-Entry Program (CREP) Based on the UCLA Community re-entry modules modified to be administered during brief hospitalizations to address the immediate needs of a patient who is transitioning back into the community. |

| XIANG 2006 63 | Group | Clinician | 16 | 8 | 1 | 16 |

SILS - Community Re-entry Module Chinese version of the community re-entry module. |

| XIANG 2007 64 | Group | Clinician | 16 | 4 | 1 | 16 |

SILS-Community Re-entry Module Chinese version of the community re-entry module |

| Recovery Oriented Self-management | |||||||

| BARBIC 2009 23 | Group | Peer | 12 | 12 | 2 | 24 |

The Modified Recovery Workbook program Training uses combination of teaching, group discussion and practical exercises, complemented by a workbook for use between sessions. Uses an educational process to increase awareness of recovery, increase knowledge and control of the illness, increase awareness of the importance and nature of stress, enhance personal meaning and sense of potential, build personal support, and develop goals and plans of action. *Note: does not include strategies for medication management |

| COOK 2013 56 | Group | Peer | 9 | 9 | 2.5 | 22.5 |

Wellness Recovery Action Planning (WRAP) Group sessions consisted of lectures, individual and group exercises, personal sharing and role modelling, and voluntary homework to practice using and refining one’s WRAP plan between groups. The content of each session is described fully elsewhere (Cook, Copeland, Jonikas et al., 2012), and consisted of: (a) the key concepts of WRAP and recovery, (b) personalized strategies to maintain well-being, (c) daily maintenance plans with simple and affordable tools to foster daily wellness, (d) advance planning to proactively respond to self-defined symptom triggers, (e) early warning signs that a crisis is impending and advance planning for additional support during these times, (f) advance crisis planning to identify preferred treatments and supporters when in acute phases of the illness, and (g) post crisis planning to resume daily activities and revise one’s WRAP plan if needed. |

| COOK 2011 27–29 | Group | Peer | 8 | 8 | 2.5 | 20 |

Wellness Recovery Action Planning (WRAP) Behavioural health illness self-management intervention where participants create an individualized plan to achieve and maintain recovery by learning to utilize wellness maintenance strategies, identify and manage symptoms and crisis triggers, and cope with psychiatric crises during and following their occurrence. Instructional techniques promote peer modelling and support by using personal examples from peer facilitators’ and students’ lives to illustrate key concepts of self-management and recovery. |

| COOK 2012 30,31 | Group | Peer | 8 | 8 | 2.5 | 20 |

Building Recovery of Individual Dreams and Goals through Education and Support (BRIDGES) Course topics included recovery principles and stages; structured problem-solving and communication skills training; strategies for building interpersonal and community support systems; brain biology and psychiatric medications; diagnoses and related symptom complexes; traditional and non-traditional treatments for SMI; and relapse prevention and coping skills. |

| VAN GESTEL-TIMMERMANS 2012 48 | Group | Peer | 12 | 12 | 2 | 24 |

“Recovery Is Up to You” Course Trained peer instructors (at an advanced state of their recovery process) were employed to facilitate this group intervention, with discussion and skills practice. Participants used a standardized workbook that covered recovery-related themes: the meaning of recovery to participants, personal experiences of recovery, personal desires for the future, making choices, goal setting, participation in society, roles in daily life, personal values, how to get social support, abilities and personal resources, and empowerment and assertiveness. Important elements of the course were the presence of role models, psychoeducation and illness management, learning from other’s experiences, social support, and homework assignments. |

| Coping Oriented Self-Management | |||||||

| CHIEN 2013 24 | Group | Clinician | 12 | 24 | 2 | 24 |

Mindfulness-Based Psychoeducation Program (MBPP) The program is a psychoeducational program that addresses patients' awareness and knowledge of schizophrenia and builds skills for illness management. (a) phase 1: orientation and engagement, empowerment and focused awareness of experiences, bodily sensations/thoughts and guided awareness exercises and homework practices; (b) phase 2: education about schizophrenia care, intentionally exploring and dealing with difficulties regarding symptoms and problem-solving practices; and (c) phase 3: behavioural rehearsals of relapse prevention strategies, accessible community support resources and future plans. |

| CHIEN 2014 25 | Group | Clinician | 12 | 24 | 2 | 24 |

Mindfulness-Based Psychoeducation Program (MBPP) As described above in Chien, 2013 |

| CHIEN 201726 | Group | Clinician | 12 | 24 | 2 | 24 |

Mindfulness-Based Psychoeducation Group Program (MBGP) As described above in Chien, 2013. Name of intervention changed to MBGP, but contents of intervention appear to be the same. |

| SCHAUB 2016 61 | Group | Clinician | 12 | 7 | 1.25 | 5 |

Group-based Coping Oriented Program (COP) COP seeks to improve understanding of the illness and its treatment, to teach coping strategies for specific stressors and symptoms, to activate the use of internal and external resources, and to enhance self-confidence and hope. COP combines elements of illness management with cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis. Includes psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioural teaching principles (e.g., cognitive restructuring, role playing, problem solving). COP focused on topics of greatest concern to patients, such as symptom-management (e.g., coping with anxiety and positive symptoms), managing stress (stress-management including mindfulness and problem solving), building up rewarding activities, time management, social skills (e.g., dealing with relatives, getting to know people), reintegration into the workplace, and providing information about outpatient services. In early groups, participants identified specific distressing symptoms for which coping strategies were selected and taught. |

| WANG 201650 | Group | Clinician | 12 | 24 | 2 | 24 |

Mindfulness-Based Psychoeducation Group Program (MBGP) As described above in Chien, 2013. Name of intervention changed to MBGP, but contents of intervention appear to be the same. |

NR – Not reported

Description of intervention, with assumption that meets 4 criteria (*with exception of Barbic, 2009).

Total intervention contact time

Outcome Measures

The table in data supplement 3 outlines the continuous measures used in studies, categorised by outcome type. Dichotomous data were also reported. Outcome measures used across the studies were reported to be well-validated and reliable instruments. Symptom outcomes were reported on measures ranging from self-rated (The Internal State Scale (ISS) to those rated by caregivers (PECC) and those requiring a clinical interview (PANSS and BPRS). In the majority of studies, relapse was measured as an admission to hospital. A small minority of trials additionally identified relapse in participants when a score reached a cut-off point on a scale, but admission data was given precedence in the present analysis. Measures of quality of life were self-rated whereas functioning tended to be clinician rated. Measures of recovery which focused on personal recovery as opposed to clinical recovery were exclusively self-rated.

Risk of Bias

The risk of bias summary is shown in Figure 2 and the rating for each individual study can be found in data supplement 4. Blinding of participants and personnel is generally considered to be challenging in complex interventions, so that risk of bias in this respect was rated as high in all studies except for one.59 Of note, nine studies were at a high risk of bias for selective reporting of outcomes measured, and 18 were unclear. The “other bias” category refers to whether any studies were discontinued due to adverse events or problems with the study design or acceptability of the intervention.

Figure 2. Cochrane Risk of Bias Summary.

Quantitative Synthesis

Data were analysed at two time points: at the end of the treatment intervention (that is, immediately, or within two weeks) and at follow up. The median follow-up length was 41 weeks (range 4 to 104 weeks) post-treatment; 52 weeks (range 7 to 130 weeks) post randomisation. Summary results are outlined in table three below (forest plots in data supplement 5).

Symptoms

Seventeen studies (n=1979) found a small but significant effect of self-management on total symptoms at post treatment (SMD= -0.43, 95% CI [-0.63 to -0.22]). At follow up, 13 studies (n= 1520) demonstrated a marked effect of self-management on total symptoms (SMD= -0.88; 95% CI [-1.19 to -0.57]). There was no significant effect on positive symptoms at post-treatment, however at follow up (K= 6; n= 771) there was a moderate effect (SMD= -0.61; 95% CI [-1.03 to -0.19]). Self-management had a small effect on negative symptoms at post treatment (SMD= - 0.26, 95% CI [-0.47 to -0.05]) and a moderate effect at follow up (SMD= -0.51, 95%CI [-0.82 to -0.21]). When looking at symptoms of depression and anxiety, five studies (n= 452) favoured self-management both at end of treatment (SMD= -0.26; 95% CI [-0.51 to -0.01]) and follow up (SMD= -0.19; 95% CI [-0.33 to -0.04]; k=6; n= 964).

Relapse/Readmission

Self-management did not have an effect on the total number of patients readmitted at either time point (SMD= 0.84, 95% CI [0.48, 1.46] and SMD=0.75, 95% CI [0.51, 1.08] respectively), however there was an effect at follow up on the mean number of readmissions (SMD= -0.92, 95% CI [-1.63 to -0.21]). A small effect (SMD= -0.26, 95% CI [-0.50 to -0.02]) was demonstrated on length of hospital admissions immediately following treatment (k=6, n= 902), while a moderate effect (SMD= - 0.68, 95% CI [-1.10 to -0.25] was found at follow up (k=7, n= 908).

Self-rated Recovery

In relation to overall self-rated recovery, self-management was favoured over control at both time points with a moderate effect size (SMD= -0.62; 95% CI [-1.03 to - 0.22]) immediately following treatment (k=11; n= 1013), and a large effect at follow up (k=7, n = 1134; SMD= -0.81; 95% CI [-1.40 to -0.22]).

Empowerment

At the end of treatment (k=3; n=346) self-management interventions did not increase sense of empowerment (SMD= -1.44; 95% CI [-2.97 to 0.08]), however at follow up (k=2, n= 538) there was a small but significant effect (SMD= -0.25; -0.43 to -0.07).

Hope

Self-management did not impact hope at end of treatment (k= 2, n= 389; SMD= - 0.18; 95% CI [-0.38 to 0.01]). At follow up three studies with 967 participants showed a small but significant effect favouring self-management over control (SMD= -0.24; [-0.46 to -0.02]).

Self-Efficacy

Four studies (n= 601) reporting on self-efficacy at end of treatment favoured self-management (SMD=-0.38; 95% CI [-0.62 to -0.15]). One study provided data for self-efficacy at follow up (n= 221), which also favoured self-management (SMD= - 0.34; 95%CI [-0.61 to -0.07]).

Functioning

At the end of treatment (k= 15, n= 1948), there was evidence of a moderate effect of self-management on functioning (SMD= -0.56; 95% CI [-0.85 to -0.28]). At follow up (k= 14, n= 1805) this increased to a large sized effect of self-management on social and functional disability (SMD= -0.90; 95% CI [-1.34 to -0.45]).

Quality of Life

Immediately following the end of the intervention, evidence from nine studies (n=863) showed a small but significant effect of self-management on participant’s self-rated quality of life (SMD= -0.23; 95% CI [-0.37 to -0.10]) which was maintained at follow up (k= 7, n= 980) (SMD= -0.25, 95%CI [-0.37 to -0.12]).

Heterogeneity and Sensitivity Analyses

Seventeen of the twenty-two meta-analyses had high levels of heterogeneity as assessed by an I2 greater than 50% and/or a significant X2 test. The one-study-removed method17 was utilised to explore sources of statistical heterogeneity. Although high heterogeneity was identified in a range of meta-analyses, it did not appear to be driven by just one study. An evaluation of clinical and methodological characteristics resulted in the decision to not remove any studies. A full account of the sensitivity analysis is in data supplement 6.

Publication Bias

Funnel plots were created for the six meta-analyses that had more than 10 studies (see data supplement 7). The small number of studies and participants across these studies, meant that it was difficult to discern any evident publication bias.

Post-Hoc Analysis

A post-hoc sub group analysis of TAU only and active control only studies was conducted (see results table in data supplement 8). No differential pattern of outcomes between the different comparators was found.

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating self-management interventions for people with severe mental illness. The reviewed evidence suggests that self-management does confer benefits across a broad range of outcomes. Specifically, self-management has a positive impact on total symptom severity, negative symptoms and the symptoms of depression and anxiety, both at end of treatment and at 1-year follow-up. Self-management was found to impact on positive symptoms at follow up only. The effect size for self-management on total symptom severity was comparable to or better than those found in recent meta-analyses of cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp): pooled effect size -0.33 [95%CI: -0.47 to -0.19]65 and 0.40 [95%CI [0.252, 0.58].66 At longer term follow up (approximately 1 year post intervention) self-management had a large effect (SMD=-0.88; 95%CI [-1.19, -0.57]) although the high heterogeneity should be noted.

Despite the positive effect on symptoms, the findings were inconsistent for variables related to relapse and readmission. This was in contrast to a previous meta-analysis of self-management interventions for those with schizophrenia only8 which found a significant impact on relapse and readmission. In the present review, few studies reported relapse as an outcome and of those that did, only a small number of participants experienced relapse events which may account for the lack of effect. The paucity of data impedes making any comment on the effect of self-management on relapse. Self-management did however demonstrate a small to moderate effect in terms of reducing the average length of hospitalisation both at the end of treatment and one year follow-up.

Self-management did demonstrate a significant medium sized effect on global functioning, and a small but significant effect on quality life at both end of treatment and 1-year follow-up. Furthermore, self-management seems to confer a benefit on outcomes valued especially highly by consumers,67 that is outcomes related to personal recovery, and individual’s sense of empowerment, hope and self-efficacy. A moderate to large effect on overall recovery and self-efficacy was seen at both end of treatment and follow up; the effect on the recovery related concepts of empowerment and hope were significant at follow up only.

Methodological Limitations of Primary Studies

While all studies included in this review were randomised controlled trials, there was variation in the reporting of sequence generation, allocation concealment and, as is common in complex interventions, blinding of participants and personnel was not always consistent. The greatest cause for concern was the selective reporting of outcomes which was noted or not clearly reported in two thirds of the studies reviewed. Furthermore, the relatively small number of studies and participants in some studies, meant that it was difficult to discern any evident publication bias. These limitations must be considered alongside the findings presented in this review to avoid an overestimate of the benefit of self-management.

Strengths and Limitations of the Review

This review gives a broad indication of the effectiveness and potential value of self-management interventions for people with severe mental illness. A strength of this review is the generalisability of the findings to current practice. For instance, it included a diagnostically heterogeneous sample of people with SMI, representative of those on caseloads in secondary care mental health services, and included samples from a wider range of countries and cultures.

Regarding limitations, heterogeneity was found to be high across many of the meta-analyses, and while a certain amount of heterogeneity is inevitable, we have tried to mitigate this through the use of random effects modelling17. A further potential limitation is from the risk of bias quality assessment of the studies included in this review. Interestingly, readmission rates and service use outcomes were infrequently measured by studies. We recommend the inclusion of this outcome in future studies of self-management. We also encourage collection and reporting of important sample characteristics such as participants’ length of illness. Fewer than half of the included studies reported on length of illness - a potential mediator of the effectiveness of self-management interventions.

The choice to pool together comparisons of self-management against TAU or against active controls in the same analyses could be criticised. A post-hoc sub group analysis of TAU only and active control only studies showed no differential pattern of outcomes between the different comparators. Arguably, TAU varies hugely among the included studies, and all of the active controls are treatments which might be available from a multi-disciplinary community mental health team. Thus, irrespective of whether TAU and active controls are combined or not, the analysis is evaluating the addition of self-management to highly varied care.

The absence of patient and public involvement (PPI) in this review is a limitation. Its inclusion would have been particularly useful in developing the operationalisation of self-management, as well as contributing to the interpretation and implications of findings from a users’ perspective. A final limitation in conducting this review was the lack of consensus of how to define the concept known as self-management. Our review is based on a clear operationalisation of self-management: however, there is still substantial variation in interventions.

Implications for Practice

While self-management for this population has been previously recommended at a guideline level,16,68 it remains to be routinely implemented at a service level. On the basis of this review, there is a strong case for including self-management as a high priority for psychosis services and generic community mental health services, alongside interventions such as CBTp or employment support. The diagnostically mixed populations in many studies may have been an impediment to identification of self-management as a high priority in guidance focused on specific groups, but our study supports recommendations from policy bodies and service user groups that support for self-management should be at the core of care for all long-term health conditions, physical and mental69,70. Self-management interventions are relatively straightforward compared to other psychotherapeutic interventions and can be delivered across settings and in a variety of ways, including group, individual, digital, bibliotherapy or a combination, increasing potential for wide implementation. In this population they are often supported: support may be from clinicians, but also from peers, which one may hypothesise could be especially effective in empowering patients and increasing self-efficacy to manage their illness. Effective implementation of these interventions have the potential to alter the long-term course of both the mental and physical health of people with severe mental illness.

Research Implications

In terms of future research, demonstrating whether there are clear effects on relapse and readmission is likely to require large, methodologically robust trials that include these outcomes along with cost effectiveness analysis. The high heterogeneity in this review suggests there are important differences in the content and implementation or context of self-management interventions which influence how effective they may be. There are likely a number of potential contributors: length of intervention, contact time, facilitator (clinician or peer) and type of self-management intervention (from proposed subtypes). Future intervention studies would also benefit from the inclusion of measures of potential mediators and moderators: for instance the addition of measures of cognitive outcomes in future studies will be important to assess its role in mediating improvements in functioning. Additionally, structured development of future self-management programs in conjunction with service users is recommended.71

Accordingly, there is a need to explore what forms of self-management are most effective, feasible and acceptable, and for whom. Possible study paradigms include realist evaluation of what works for whom, mechanistic studies or a broader systematic review that would have in its scope naturalistic studies using a variety of methods to look at experiences and outcomes of delivering self-management in various ways. Nevertheless, the evidence that self-management already has positive effects on a range of important outcomes is already substantial: thus research is now needed on how to overcome implementation barriers and embed self-management in a sustained and widespread way to routine care for people with long-term mental health conditions, and how to evaluate the effect of this. Implementation-evaluation designs have potential to address these questions.

Supplementary Material

Table 3. Analysis of Self-Management Intervention (SM) for people with severe mental illness compared to control (active or TAU) (random-effects model).

| Outcome | Time of data collection | Trials (k) | Participants SM/control (n) | Estimate | Summary of estimate [95% CI] | Z, p | Heterogeneity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q test | I2 (%) | ||||||||

| Symptoms | (1) Total Symptoms | End of treatment | 17 | 912/1067 | SMD | -0.43 [-0.63, -0.22] | 4.12, p<.0001* | Q = 72.84, p<0.0001 | 78† |

| Follow-up | 13 | 676/844 | SMD | -0.88 [-1.19, -0.57] | 5.52, p<.0001* | Q = 82.69, p<0.0001 | 87† | ||

| Positive Symptoms | End of treatment | 8 | 372/507 | SMD | -0.22 [-0.51, 0.07] | 1.50, p= 0.13 | Q = 26.09, p=0.0005 | 73† | |

| Follow-up | 6 | 312/459 | SMD | -0.61 [-1.03, -0.19] | 2.86, p= 0.004* | Q= 33.27, p<0.0001 | 85† | ||

| Negative Symptoms | End of treatment | 9 | 457/590 | SMD | -0.26 [-0.47, -0.05] | 2.44, p= 0.01* | Q= 19.62, p= 0.01 | 59† | |

| Follow-up | 7 | 378/523 | SMD | -0.51 [-0.82, -0.21] | 3.28, p= 0.001* | Q= 26.50, p= 0.0002 | 77† | ||

| Affective Symptoms (Depression/Anxiety) | End of treatment | 5 | 230/222 | SMD | -0.26 [-0.51, -0.01] | 2.04, p = 0.04* | Q = 6.69, p= 0.15 | 40 | |

| Follow-up | 6 | 475/489 | SMD | -0.19 [-0.33, -0.04] | 2.43, p = 0.02* | Q = 5.91, p= 0.31 | 15 | ||

| Relapse | (2) Mean number of readmissions to acute care | End of treatment | 5 | 315/456 | SMD | -0.39 [-0.89, 0.11] | 1.52, p= 0.13 | Q = 38.72, p<0.0001 | 90† |

| Follow-up | 5 | 257/398 | SMD | -0.92 [-1.63, -0.21] | 2.53, p = 0.01* | Q = 57.74, p<0.0001 | 93† | ||

| Total number of patients in each group readmitted to acute care | End of treatment | 2 | 104/147 | RR | 0.84 [0.48, 1.46] | 0.63, p = 0.53 | Q = 0.72, p=0.40 | 0 | |

| Follow-up | 10 | 416/473 | RR | 0.75 [0.51, 1.08] | 1.54, p = 0.12 | Q =15.05, p = 0.09† | 40 | ||

| Length of admission to acute care | End of treatment | 6 | 359/543 | SMD | -0.26 [-0.50, -0.02] | 2.08, p= 0.04* | Q = 10.77, p= 0.03 | 63† | |

| Follow-up | 7 | 350/558 | SMD | -0.68 [-1.10, -0.25] | 3.12, p=0.002* | Q = 49.76, p<0.0001 | 88† | ||

| Recovery | (3) Recovery - Total | End of treatment | 11 | 507/506 | SMD | -0.62 [-1.03, -0.22] | 3.03, p= 0.002* | Q = 89.3, p<0.0001 | 89† |

| Follow-up | 7 | 543/591 | SMD | -0.81 [-1.40, -0.22] | 2.68, p = 0.007* | Q = 105.09 p<0.0001 | 94† | ||

| Recovery - Empowerment | End of treatment | 3 | 187/159 | SMD | -1.44 [-2.97, 0.08] | 1.86, p = 0.06 | Q = 44.89, p<0.0001 | 96† | |

| Follow-up | 2 | 278/260 | SMD | -0.25 [-0.43, -0.07] | 2.68, p = 0.007* | Q = 1.13, p = 0.29 | 12 | ||

| Recovery- Hope | End of treatment | 2 | 200/189 | SMD | -0.18 [-0.38, 0.01] | 1.81, p = 0.07 | Q= 0.52, p= 0.47 | 0 | |

| Follow-up | 3 | 487/480 | SMD | -0.24 [-0.46, -0.02] | 2.16, p = 0.03* | Q = 5.74, p = 0.06 | 65† | ||

| Recovery - Self-Efficacy | End of treatment | 4 | 322/279 | SMD | -0.38 [-0.62, -0.15] | 3.18, p = 0.001* | Q = 5.42, p= 0.14 | 45 | |

| Follow-up | 1 | 121/100 | SMD | -0.34 [-0.61, -0.07] | 2.50, p = 0.01* | N/A | N/A | ||

| Functioning | (4) Functioning | End of treatment | 15 | 884/1064 | SMD | -0.56 [-0.85, -0.28] | 3.90, p<0.0001* | Q =121.25, p<0.0001 | 88† |

| Follow-up | 14 | 805/1000 | SMD | -0.90 [-1.34, -0.45] | 3.97, p<0.0001* | Q = 237.9, p<0.0001 | 95† | ||

| QoL | (5) Quality of Life | End of treatment | 9 | 440/423 | SMD | -0.23 [-0.37, -0.10] | 3.38, p =0.0007* | Q = 7.83, p = 0.45 | 0 |

| Follow-up | 7 | 491/489 | SMD | -0.25 [-0.37, -0.12] | 3.84, p=0.0001* | Q =3.07, p = 0.80 | 0 | ||

Statistically significant finding (p<0.05)

Indicates high heterogeneity: I2 exceeds 50% and/or P value less than 0.10

Funding

This paper reports work undertaken as part of the CORE Study, which is funded by the National Institute for Health Research under its Programme Grants for Applied Research programme (reference RP-PG-0109-10078). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Contributors: ML, BLE, AM, MFA, TK, AYU, BHS and SJ contributed to the design and data search strategy. ML, AM, BHS and AYU completed the literature search and data extraction. ML analysed the data. ML, BLE, AM, MFA, and SJ interpreted the data. ML and MFA contributed to the creation of the tables and figures. ML wrote the review and all authors have contributed to drafting and approved the final manuscript, and all take responsibility for its content.

Declaration of Interests: We declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Dr Miriam Fornells-Ambrojo, Division of Psychology and Language Sciences, UCL, London, UK.

Dr Alyssa Milton, Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia.

Dr Brynmor Lloyd-Evans, Mental Health and Social Care Division of Psychiatry, UCL, London, UK.

Dr Amina Yesufu-Udechuku, Centre for Outcomes Research and Effectiveness, UCL, London, UK.

Professor Tim Kendall, Mental Health NHS England, UK.

Professor Sonia Johnson, Division of Psychiatry, UCL, London UK.

References

- 1.Taylor SJ, Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E, Pearce G, Parke HL, Schwappach A, et al. A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions: PRISMS – Practical systematic Review of Self-Management Support for long-term conditions. Heal Serv Deliv Res. 2014;2:1–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) The Way Forward: federal action for a system that works for all people living with SMI and SED and their families and caregivers. Interdepartmental Serious Mental Illness Coordinating Committee Full Report. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueser KT, Corrigan PW, Hilton DW, Tanzman B, Schaub A, Gingerich S, et al. Illness Management and Recovery: a review of the research. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1272–84. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.10.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueser KT, McGurk SR. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2004;363:2063–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16458-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao S, Sampson S, Xia J, Jayaram MB. Psychoeducation (brief) for people with serious mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:1–117. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010823.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lincoln TM, Wilhelm K, Nestoriuc Y. Effectiveness of psychoeducation for relapse, symptoms, knowledge, adherence and functioning in psychotic disorders: A meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2007;96:232–45. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott AJ, Webb TL, Rowse G. Self-help interventions for psychosis: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;39:96–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zou H, Li Z, Nolan MT, Arthur D, Wang H, Hu L. Self-management education interventions for persons with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2013;22:256–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text rev. American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mueser KT, Deavers F, Penn DL, Cassisi JE. Psychosocial Treatments for Schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:465–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leamy M, Bird V, LeBoutillier C, Williams J, Slade M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:445–52. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, Glick H, Kinosian B, Altshuler L, et al. Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: part I. Intervention and implementation in a randomized effectiveness trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:927–36. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, Glick H, Kinosian B, Altshuler L, et al. Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: Part II. Impact on clinical outcome, function, and costs. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:937–45. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer MS, Biswas K, Kilbourne AM. Enhancing multiyear guideline concordance for bipolar disorder through collaborative care. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1244–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. 2014 ( https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178) [PubMed]

- 17.Higgins J, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sterne JAC, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323:101–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuijpers P. Meta-analyses in mental health research: A practical guide. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eckman T, Wirshing W, Marder S, Liberman R, Johnston-Cronk M, Zimmerman K, et al. Techniques for training schizophrenic patients in illness self-management: A controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1549–55. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.11.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kopelowicz A, Wallace C, Zarate R. Teaching psychiatric inpatients to re-enter the community: a brief method of improving the continuity of care. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:1313–6. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.10.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atkinson JM, Coia DA, Gilmour WH, Harper JP. The impact of education groups for people with schizophrenia on social functioning and quality of life. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:199–204. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barbic S, Krupa T, Armstrong I. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of a modified recovery workbook program: preliminary findings. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:491–7. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chien WT, Lee IYM. The mindfulness-based psychoeducation program for chinese patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:376–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.002092012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chien WT, Thompson DR. Effects of a mindfulness-based psychoeducation programme for Chinese patients with schizophrenia: 2-year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:52–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.134635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chien WT, Bressington D, Yip A, Karatzias T. An international multi-site, randomized controlled trial of a mindfulness-based psychoeducation group programme for people with schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2017;47:2081–96. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook JA, Copeland ME, Jonikas JA, Hamilton MM, Razzano LA, Grey DD, et al. Results of a randomized controlled trial of mental illness self-management using wellness recovery action planning. Schizophr Bull. 2011;38:881–91. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook JA, Copeland ME, Floyd CB, Jonikas JA, Hamilton MM, Razzano LA, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Effects of Wellness Recovery Action Planning on Depression, Anxiety, and Recovery. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:541–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jonikas JA, Grey DD, Copeland ME, Razzano LA, Hamilton MM, Floyd CB, et al. Improving propensity for patient self-advocacy through wellness recovery action planning: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49:260–9. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9475-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook JA, Steigman P, Pickett S, Diehl S, Fox A, Shipley P, et al. Randomized controlled trial of peer-led recovery education using Building Recovery of Individual Dreams and Goals through Education and Support (BRIDGES) Schizophr Res. 2012;136:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pickett SA, Diehl SM, Steigman PJ, Prater JD, Fox A, Shipley P, et al. Consumer empowerment and self-advocacy outcomes in a randomized study of peer-led education. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48:420–30. doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9507-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalum HS, Waldemar AK, Korsbek L, Hjorthøj C, Mikkelsen JH, Thomsen K, et al. Illness management and recovery: Clinical outcomes of a randomized clinical trial in community mental health centers. PLoS One. 2018;13:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalum HS, Waldemar AK, Korsbek L, Hjorthoj C, Mikkelsen JH, Thomsen K, et al. Participants’ and staffs’ evaluation of the Illness Management and Recovery program: a randomized clinical trial. J Ment Heal. 2018;27:30–7. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2016.1244716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Färdig R, Lewander T, Melin L, Folke F, Fredriksson A. A randomized controlled trial of the illness management and recovery program for persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:606–12. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.6.pss6206_0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasson-Ohayon I, Roe D, Kravetz S. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of the illness management and recovery program. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:1461–6. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.11.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levitt AJ, Mueser KT, Degenova J, Lorenzo J, Bradford-Watt D, Barbosa A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of illness management and recovery in multiple-unit supportive housing. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1629–36. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.12.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin EC-L, Chin Hong C, Wen-Chuan S, Mei-Feng L, Shujen S, Mueser KT, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an adapted Illness Management and Recovery program for people with Schizophrenia awaiting discharge from a psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2013;36:243–9. doi: 10.1037/prj0000013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monroe-DeVita M, Morse G, Mueser KT, McHugo GJ, Xie H, Hallgren KA, et al. Implementing Illness Management and Recovery Within Assertive Community Treatment: A Pilot Trial of Feasibility and Effectiveness. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69:562–71. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perry A, Tarrier N, Morriss R, Mccarthy E, Limb K. Randomised controlled trial of efficacy of teaching patients with bipolar disorder to identify early symptoms of relapse and obtain treatment. BMJ. 1999;318:149–53. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7177.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sajatovic M, Davies MA, Ganocy SJ, Bauer MS, Cassidy KA, Hays RW, et al. A comparison of the life goals program and treatment as usual for individuals with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1182–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.9.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salyers MP, McGuire AB, Rollins AL, Bond GR, Mueser KT, MacY VR. Integrating assertive community treatment and illness management and recovery for consumers with severe mental illness. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46:319–29. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shon K-H, Park S-S. Medication and symptom management education program for the rehabilitation of psychiatric patients in Korea: The effects of promoting schedule on self-efficacy theory. Yonsei Med J. 2002;43:579–89. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2002.43.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith DJ, Griffiths E, Poole R, di Florio A, Barnes E, Kelly MJ, et al. Beating Bipolar: Exploratory trial of a novel internet-based psychoeducational treatment for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13:571–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan CHS, Ishak RB, Lim TXG, Marimuthusamy P, Kaurss K, Leong JYJ. Illness management and recovery program for mental health problems: reducing symptoms and increasing social functioning. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:3471–85. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Todd NJ, Solis-Trapala I, Jones SH, Lobban FA. An online randomised controlled trial to assess the feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of ‘Living with Bipolar’: A web-based self-management intervention for Bipolar Disorder. Trial design and protocol. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:679–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Todd NJ, Jones SH, Hart A, Lobban FA. A web-based self-management intervention for Bipolar Disorder ‘living with bipolar’: a feasibility randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2014;169:21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Torrent C, Bonnin M, Ph D, Martínez-arán A, Ph D, Valle J, et al. Efficacy of Functional Remediation in Bipolar Disorder: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:852–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12070971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Gestel-Timmermans H, Brouwers EPM, van Assen MaLM, van Nieuwenhuizen C. Effects of a Peer-Run Course on Recovery From Serious Mental Illness: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:54–60. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201000450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]