Abstract

Background

The “GENetIcs of sUbSequent Coronary Heart Disease” (GENIUS-CHD) consortium was established to facilitate discovery and validation of genetic variants and biomarkers for risk of subsequent CHD events, in individuals with established CHD.

Methods

The consortium currently includes 57 studies from 18 countries, recruiting 185,614 participants with either acute coronary syndrome, stable CHD or a mixture of both at baseline. All studies collected biological samples and followed-up study participants prospectively for subsequent events.

Results

Enrolment into the individual studies took place between 1985 to present day with duration of follow up ranging from 9 months to 15 years. Within each study, participants with CHD are predominantly of self-reported European descent (38%-100%), mostly male (44%-91%) with mean ages at recruitment ranging from 40 to 75 years. Initial feasibility analyses, using a federated analysis approach, yielded expected associations between age (HR 1.15 95% CI 1.14-1.16) per 5-year increase, male sex (HR 1.17, 95% CI 1.13-1.21) and smoking (HR 1.43, 95% CI 1.35-1.51) with risk of subsequent CHD death or myocardial infarction, and differing associations with other individual and composite cardiovascular endpoints.

Conclusions

GENIUS-CHD is a global collaboration seeking to elucidate genetic and non-genetic determinants of subsequent event risk in individuals with established CHD, in order to improve residual risk prediction and identify novel drug targets for secondary prevention. Initial analyses demonstrate the feasibility and reliability of a federated analysis approach. The consortium now plans to initiate and test novel hypotheses as well as supporting replication and validation analyses for other investigators.

Journal Subject Terms: Genetic, Association Studies; Cardiovascular Disease; Epidemiology; Secondary Prevention; Biomarkers

Keywords: coronary artery disease; genetics, association studies; residual risk; secondary prevention; recurrent event; myocardial infarction; prognosis

Introduction

Major public health initiatives and policy changes, along with advances in drug and interventional therapies have significantly reduced cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in most high-income countries.1–3 However, the improved survival rates following an initial presentation with coronary heart disease (CHD) has, paradoxically, led to a growing number of patients living with established CHD (e.g 16M in the USA, 3M in the UK)4 5 who remain at substantially high risk of subsequent cardiovascular events. These include myocardial infarction (MI), repeated revascularizations, but also heart failure (HF), stroke and sudden death.4

Despite a large body of knowledge on the pathophysiology of first CHD events in general populations,6, 7 little is known about factors that influence disease progression or subsequent events in patients with established CHD, beyond those consequent to the acute index event in the short term (such as biomarkers of myocardial dysfunction or necrosis, left ventricular function or arrhythmia).8 As a result, although guidelines and treatment thresholds have progressively evolved over the last two decades, the targeted risk factors per se have remained largely unaltered.9 Novel therapies beyond lipid lowering, anti-platelet agents, and drugs recommended for high blood pressure and heart failure have been slow to emerge. Importantly, multiple novel and existing agents (e.g darapladib, varespladib, , and folic acid) have failed in very late stage clinical development despite promising observational data.10, 11 12, 13 In contrast, some traditional risk factors, such as obesity, which show robust associations with initial CHD onset,14 continue to show inverse or null associations with subsequent events once CHD has developed.15

Ultimately, the high (residual) risk in individuals with existing CHD despite optimal contemporary therapy emphasizes the need for studying risk of subsequent events and their related causal pathways. For example, in the intervention arm of the IMPROVE-It study, despite simvastatin and ezetimibe treatment following an acute coronary syndrome, at 7 years, almost a third of participants experienced the primary endpoint (a composite of cardiovascular death, major coronary event, coronary revascularization or nonfatal stroke).16 Similarly, in the FOURIER trial, almost 10% of patients with established but stable CVD, experienced an event at 2.2 years despite high intensity statin and PCSK9 inhibition, with achieved median LDL-C levels of 30mg/dL.17 These data point to the existence of risk factors beyond traditional ones such as LDL-C, and the need to elucidate their related causal pathways.18 By studying those with established CHD at high risk of subsequent events, we plan to gain novel insights into other drivers of atherosclerosis or features that identify patients who may benefit most from novel therapies.9 Genetic and biomarker studies in these individuals may help identify novel molecular pathways and future drug targets with the goal of advancing precision medicine.

In the absence of a single large resource to study the determinants of coronary heart disease prognosis, we have established The GENetIcs of SUbSequent CHD (GENIUS-CHD) consortium.19 Assembling studies from across the globe that have recruited patients with different types of CHD at baseline, have acquired prospective follow up, and have stored biological specimens, or genetic data, the consortium aims to: (1) investigate genetic and non-genetic determinants of risk for subsequent CHD, systematically and at scale; and (2) facilitate access to data and expertise, as a platform to foster collaboration among investigators working in the field.

Here we describe the design of the consortium, including details of participating studies, available data and samples, as well as the governance procedures and the consortium’s approach to data sharing and collaboration to further advance the stated scientific aims. In addition, we present some early findings from an investigation of the association of patient characteristics and certain routinely recorded measures on the risk of subsequent events among patients with different types of CHD at baseline.

Methods

In accordance with Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines, the data, analytic methods, and study materials will be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedures. Participating studies received local institutional review board approval and included patients who had provided informed consent at the time of enrolment. The central analysis sites also received waivers from their local institutional review board for collating and analysing summary level data from these individual studies. Full details on the eligibility criteria, definitions of terminology, management of the consortium, and planned projects are provided in Supplementary Materials.

Results

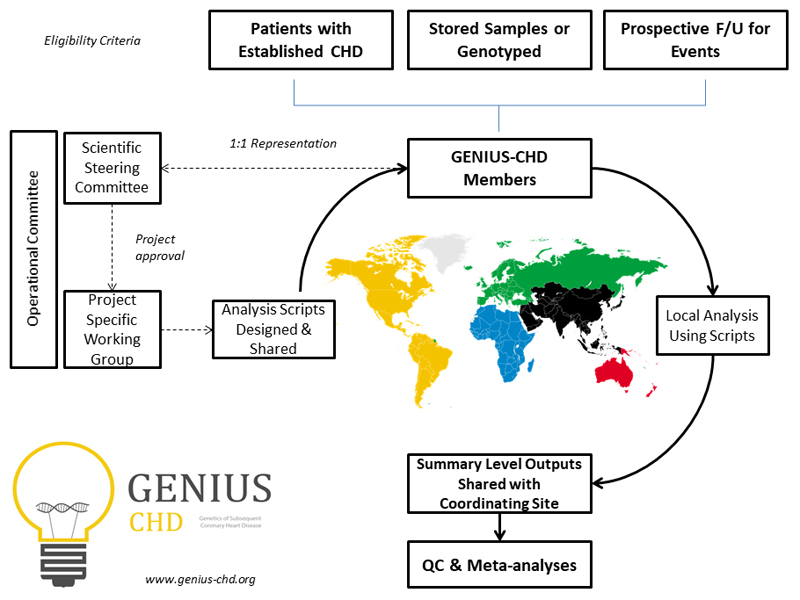

The design and structure of the GENIUS-CHD consortium is presented in Figure 1. Studies meeting the main eligibility criteria were identified and invited to participate (Supplementary Methods). In brief, studies are eligible to join the GENIUS-CHD consortium if they meet three inclusion criteria: (1) included individuals with established CHD (defined as the presence of or confirmed history of acute coronary syndrome at baseline, or of coronary artery disease as evidenced by any revascularization procedure (percutaneous coronary intervention or bypass surgery) or demonstrable plaque in any epicardial vessel on direct coronary imaging); (2) acquired prospective follow-up of participants with ascertainment of one or more subsequent cardiovascular disease events as well as all-cause mortality; and, (3) had stored blood samples, which are viable and suitable for DNA and/or biomarker analysis or previously collected such data prior to sample depletion.

Figure 1.

Overview of the GENIUS-CHD consortium, illustrating inclusion criteria and governance structure. Following project approval by the steering committee, analyses scripts are prepared and distributed to all members, with sharing of summary level outputs before meta-analysis at the coordinating centres. CHD = coronary heart disease; QC = quality control. Further details can be found at www.genius-chd.org

At the time of writing, 57 studies from 18 countries are participating in the consortium and are listed in Table 1. Please refer to www.genius-chd.org for an updated list. Brief narrative descriptions of each study are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Table 1. Overview of each study participating in the GENIUS-CHD consortium.

| Alias | Cohort Name | Country | Study Design | Recruitment Period | CHD Type | Total recruited with CHD | European ancestry (%) | Europeans recruited with CHD | Mean Follow up Time (SD) | Age (SD) | Male (%) | PubMED ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4C | Clinical Cohorts in Coronary disease Collaboration (4C) | UK | Clinical Cohort | 2009-2014 | CAD | 3345 | 54.8 | 1832 | 2.56 (0.95) | 61.8 (12.14) | 61.5 | NA |

| AGNES | Arrhythmia Genetics in The Netherlands | Netherlands | Clinical Cohort | 2001-2005 | ACS | 1459 | 100.0 | 1459 | 6.73 (4.75) | 57.8 (10.73) | 79.2 | 20622880 |

| ANGES | Angiography and Genes Study | Finland | Clinical Cohort | 2002-2005 | Mixed | 588 | 100.0 | 588 | 8.20 (4.47) | 64.1 (9.59) | 65.5 | 21640993 |

| ATVB | Italian Atherosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology Group | Italy | Clinical Cohort | 1997-2006 | ACS | 1741 | 100.0 | 1741 | 10.47 (4.45) | 40.0 (4.40) | 90.8 | 21757122 |

| CABGenomics | CABG Genomics | USA | Clinical Cohort | 2001-2014 | Mixed | 2694 | 85.5 | 2303 | 6.9 (3.5) | 64.4 (10.38) | 79 | 25649697 |

| CARDIOLINES | CardioLines | Netherlands | Clinical Cohort | 2011- | Mixed | 1269 | 75.0 | 1,692 | 1.3 (0.5) | 63.5 (11.6) | 72.8 | NA |

| CDCS | Coronary Disease Cohort Study | New Zealand | Clinical Cohort | 2002-2009 | ACS | 2139 | 91.4 | 1956 | 5.21 (2.15) | 67.4 (12.01) | 71.3 | 20400779 |

| COGEN | The Copenhagen Cardiovascular Genetic study | Denmark | Clinical Cohort | 2011-2017 | Mixed | 3709 | 95.0 | 3,904 | 5.5 (1.01) | 70.1 (17.4) | 67.5 | In press |

| COROGENE | Corogene Study | Finland | Clinical Cohort | 2006-2008 | ACS | 1489 | 100.0 | 1489 | 7.7 (0.5) | 64.7 (11.88) | 70.9 | 21642350 |

| CTMM | Circulating Cells | The Netherlands | Clinical Cohort | 2009-2011 | Mixed | 713 | 96.5 | 688 | 0.97 (0.37) | 62.6 (10.08) | 69 | 23975238 |

| CURE | Cure-Genetics Study | Canada | RCT | 1998-2000 | ACS | 12434 | 82.1 | 10203 | 0.78 (0.28) | 65.4 (11.19) | 61.4 | 11102254 |

| EGCUT | Estonian Biobank | Estonia | Population | 2002-2011 | CAD | 2783 | 100.0 | 2783 | 6.65 (2.93) | 66.6 (10.99) | 51.5 | 24518929 |

| EMORY | Emory Cardiovascular Biobank | USA | Clinical Cohort | 2004- | Mixed | 5873 | 72.0 | 4229 | 4.49 (3.15) | 65.4 (11.74) | 68.7 | 20729229 |

| ERICO | Estratégia de Registro de Insuficiência Coronariana | Brazil | Clinical Cohort | 2009-2014 | ACS | 738 | 61.0 | 450 | 2.85 (1.48) | 63.8 (13.35) | 56 | 23644870 |

| FASTMI2005 | The French Registry of Acute ST elevation MI | France | Clinical Cohort | 2005- | ACS | 3669 | 100.0 | 3669 | 1.72 (0.63) | 67.3 (13.94) | 68.5 | 17893635 |

| FINCAVAS | Finnish Cardiovascular Study | Finland | Clinical Cohort | 2001-2008 | Mixed | 1671 | 100.0 | 1671 | 8.57 (3.99) | 60.9 (11.04) | 69.4 | 16515696 |

| FRISCII | FRISCII Study | Sweden | RCT | 1996-1998 | ACS | 3147 | 99.3 | 3125 | 7.46 (2.09) | 66.3 (9.82) | 69.5 | 10475181 |

| GENDEMIP | GENetic DEtermination of Myocardial Infarction in Prague | Czech Republic | Clinical Cohort | 2006-2009 | ACS | 1302 | 100.0 | 1302 | 1.13 (0.78) | 56.5 (8.66) | 74.4 | 23249639 |

| GENEBANK | Cleveland Clinic Genebank Study | USA | Clinical Cohort | 2001-2007 | Mixed | 2345 | 100.0 | 2345 | 3.00 (0.00) | 61.5 (11.06) | 74.3 | 21475195 |

| GENESIS-PRAXY | GENdEr and Sex determInantS of cardiovascular disease: From bench to beyond-Premature Acute Coronary Syndrome (GENESIS-PRAXY) | Canada | Clinical Cohort | 2009-2013 | ACS | 784 | 99.4 | 779 | 1.00 (0.00) | 48.3 (5.62) | 69.1 | 22607849 |

| GENOCOR | Genetic Mapping for Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk | Italy | Clinical Cohort | 2007-2010 | Mixed | 497 | 100.0 | 497 | 5.68 (1.20) | 65.2 (8.47) | 86.7 | 22717531 |

| GEVAMI | The GEnetic causes to Ventricular Arrhythmia in patients during first ST-elevation Myocardial Infraction | Denmark | Clinical Cohort | 2011- | ACS | 1033 | 100.0 | 1033 | 3.93 (1.40) | 59.5 (10.37) | 79.3 | 25559012 |

| GoDARTS incident | Genetics of Diabetes Audit and Research in Tayside Scotland (I) | Scotland | Population | 2004 - 2012 | CAD | 1261 | 99.8 | 1258 | 3.47 (2.95) | 71.3 (10.91) | 61.1 | 29025058 |

| GoDARTS prevalent | Genetics of Diabetes Audit and Research in Tayside Scotland (P) | Scotland | Population | 2004 - 2012 | CAD | 2514 | 99.7 | 2507 | 6.48 (3.06) | 69.1 (9.41) | 65.9 | 29025058 |

| GRACE_B | Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events - Belgium | Belgium | Clinical Cohort | 1999-2010 | ACS | 734 | 100.0 | 734 | 4.25 (1.80) | 65.9 (11.91) | 75.8 | 20231156 |

| GRACE_UK | Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events - UK | UK | Clinical Cohort | 2001-2010 | ACS | 1443 | 100.0 | 1443 | 9.54 (2.68) | 64.3 (12.21) | 69.6 | 20231156 |

| IDEAL | Incremental Decrease in End Points Through Aggressive lipid Lowering (IDEAL) | Canada | RCT | 1999-2005 | ACS | 8888 | 99.3 | 8823 | 4.63 (0.82) | 61.8 (9.47) | 80.8 | 16287954 |

| INTERMOUNTAIN | Intermountain Heart Collaborative Study | USA | Clinical Cohort | 1993-2009 | Mixed | 7556 | 89.5 | 6763 | 8.56 (5.39) | 61.2 (11.06) | 66.7 | 20691829 |

| INVEST | INternational VErapamil SR Trandolopril STudy GENEtic Substudy INVEST-GENES | USA/ International | RCT | 1997-2003 | CAD | 5979 | 38.0 | 2270 | 2.83 (0.82) | 66.1 (9.70) | 44 | 21372283, 17700361 |

| JUMC | Krakow-GENIUS-CHD | Poland | Clinical Cohort | 2010-2014 | Mixed | 747 | 100.0 | 747 | 0.84 (0.34) | 68.3 (10.26) | 71.6 | 28444280, 27481134 |

| KAROLA | Karola Study | Germany | Clinical Cohort | 1999-2000 | Mixed | 1206 | 100.0 | 1206 | 11.62 (3.01) | 58.7 (8.15) | 84.2 | 24829374 |

| LIFE-Heart | Leipzig (LIFE) Heart Study | Germany | Clinical Cohort | 2006-2014 | Mixed | 5564 | 100.0 | 5564 | 1.62 (2.03) | 63.9 (11.09) | 77.2 | 22216169 |

| LURIC | The LUdwigshafen RIsk and Cardiovascular Health Study | Germany | Clinical Cohort | 1997-2000 | Mixed | 2320 | 100.00 | 2320 | 8.58 (3.18) | 63.8 (9.92) | 76.6 | 11258203 |

| MDCS | Malmo Diet and Cancer Study | Sweden | Population | 1991-1996 | CAD | 4,546 | 100.00 | 4,546 | 8.3 (8.0) | 58.0 (7.6) | 60.2 | 19936945 |

| NE_POLAND | North East Poland Myocardial Infarction Study | Poland | Clinical Cohort | 2001-2005 | ACS | 646 | 100.0 | 646 | 7.20 (2.75) | 62.3 (11.84) | 75.4 | 26086777 |

| NEAPOLIS | Neapolis Campania Italia | Italy | Clinical Cohort | 2008-2012 | Mixed | 1394 | 100.0 | 1394 | 1.07 (0.54) | 67.6 (10.50) | 74.5 | 24262617 |

| OHGS | Ottawa Heart Genomics Study | Canada | Clinical Cohort | 2010-2013 | Mixed | 546 | 100.0 | 546 | 1.77 (0.27) | 65.6 (11.11) | 73.8 | NA |

| PERGENE | Perindopril Genetic Association Study (EUROPA) | Netherlands | RCT | 1997-2000 | CAD | 8746 | 99.0 | 8656 | 4.20 (0.62) | 59.9 (9.27) | 85.6 | 19082699 |

| PLATO | The Study of Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes | International | RCT | 2006-2008 | ACS | 18624 | 98.3 | 18315 | 0.86 (0.24) | 62.6 (10.96) | 69.5 | 19332184 |

| PMI | Post Myocardial Infarction Study | New Zealand | Clinical Cohort | 1994-2001 | ACS | 1057 | 91.1 | 963 | 8.56 (3.58) | 62.8 (10.56) | 78 | 12771003 |

| POPular | The POPular study | Netherlands | Clinical Cohort | 2005-2007 | Mixed | 1024 | 98.2 | 1006 | 1.00 (0) | 63.8 (10.39) | 74.6 | 20179285 |

| POPular Genetics | The POPular GENETICS Study | Netherlands & Belgium | RCT | 2011-2017 | ACS | 2481 | 94.3 | 2287 | 1.00 (0) | NA | 74.9 | 24952855 |

| PROSPER | Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk | Netherlands | RCT | 1997-1999 | CAD | 893 | 100.0 | 893 | 3.15 (0.71) | 75.4 (3.38) | 70.3 | 10569329 |

| RISCA | Recurrance and Inflammation in the Acute Coronary Syndromes Study | Canada | Clinical Cohort | 2001-2002 | ACS | 1054 | 100.0 | 1054 | 1.22 (0.18) | 61.8 (11.45) | 75.9 | 18549920 |

| SHEEP | Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program (SHEEP) | Sweden | Clinical Cohort | 1992-1995 | ACS | 1150 | 100.0 | 1150 | 14.87 (5.91) | 59.3 (7.21) | 70.7 | 17667644 |

| SMART | Second Manifestations of Arterial Disease | Netherlands | Clinical Cohort | 1999-2010 | Mixed | 3057 | 98.2 | 3001 | 6.77 (3.86) | 60.5 (9.31) | 81.7 | 10468526 |

| STABILITY | Stabilization of Atherosclerotic Plaque by Initiation of Darapladib Therapy trial | International | RCT | 2008-2010 | CAD | 10786 | 86.1 | 9287 | 3.60 (0.57) | 64.7 (9.10) | 82 | 24678955 |

| THI | Texgen | USA | Clinical Cohort | 2001-2008 | ACS | 3875 | 73.1 | 2834 | 5.50 (3.42) | 63.6 (10.61) | 74.9 | 21414601 |

| TNT | Treating to New Targets | Canada | RCT | 1998-1999 | CAD | 10000 | 94.1 | 9409 | 4.36 (1.47) | 61.1 (8.82) | 81.6 | 15755765 |

| TRIUMPH | Translational Research Investigating Underlying Disparities in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patient's Health Status | USA | Clinical Cohort | 2005-2008 | ACS | 2062 | 100.0 | 2062 | 0.97 (0.15) | 59.8 (12.10) | 72.2 | 21772003 |

| UCORBIO | Utrecht Coronary Biobank | Netherlands | Clinical Cohort | 2011-2014 | Mixed | 1493 | 72.4 | 1081 | 1.6 (0.9) | 65.4 (10.27) | 75.6 | NA |

| UCP | Utrecht Cardiovascular Pharacogenetics Study | Netherlands | Clinical Cohort | 1985-2010 | Mixed | 1508 | 100.0 | 1508 | 8.00 (4.16) | 64.1 (9.97) | 75.4 | 25652526 |

| UKB | UK Biobank | UK | Population | 2006-2010 | CAD | 12045 | 94.2 | 11342 | 6.39 (1.72) | 69.9 (6.07) | 80.6 | 1001779 |

| VHS | Verona Heart Study | Italy | Clinical Cohort | 1996- | CAD | 939 | 100.0 | 939 | 5.62 (2.97) | 61.3 (9.74) | 81 | 10984565 |

| VIVIT | Vorarlberg Institute for Vascular Investigation and Treatment (VIVIT) Study | Austria | Clinical Cohort | 1999-2008 | CAD | 1447 | 99.8 | 1444 | 7.43 (2.91) | 64.5 (10.45) | 72 | 24265174 |

| WARSAW ACS | Warsaw ACS Genetic Registry | Poland | Clinical Cohort | 2008-2011 | ACS | 681 | 100.0 | 681 | 2.97 (1.16) | 63.5 (11.84) | 74.2 | NA |

| WTCC | WTCCC CAD Study | UK | Clinical Cohort | 1998-2003 | Mixed | 1926 | 100.0 | 1926 | 10.05 (2.81) | 60.0 (8.13) | 79.3 | 16380912, 17634449 |

Alias denotes the abbreviated name of study used in figures and analyses; ACS = acute coronary syndrome, CAD = coronary artery disease; PubMed IDs are provided for individual study descriptions; mean (standard deviation) with proportions (%) are provided unless otherwise stated.

The majority of studies are either investigator-led clinical cohorts (n=42), but clinical trials (n=10) and nested case cohort (inception-study design) studies (n=5) are also included. Of the total, 23 studies have included participants at the time of an ACS, while the remainder recruited those with stable CHD or a mixture of the two (e.g. from cardiac catheterization labs). Collectively, 185,614 participants have been enrolled with CHD at baseline (including 812,803 person years of follow-up); of which 170,343 are of self-reported European descent. Recruitment times varied between studies, ranging from the earliest recruitment in 1985 to studies that remain actively recruiting to the present day. All studies enrolled patients >18 years of age, although one study exclusively recruited only those with premature CHD (MI<45 years), while another recruited only older subjects (>70 years). The overall mean age within each study reflects this heterogeneity, ranging from 40-75 years of age, and proportion of male sex ranging from 44-91% (Table 1).

Available data

Core phenotypes

All studies collected data on age, sex and ethnicity. Risk factor data are available for diabetes, obesity and smoking status in almost all participating studies (96%), while data on concentrations of routine blood lipids (total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C and triglycerides) (84%) and blood pressure values at enrolment (82%) were collected by the majority of studies. Data on statin use at baseline are available in 90% of all participating studies (Table 2).

Table 2. Participant characteristics of each study contributing to GENIUS-CHD.

| ALIAS | BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | Systolic BP (SD) | Diastolic BP (SD) | Diabetes (%) | Current Smoking (%) | Total cholesterol (SD), mmol/L | LDL-C (SD), mmol/L | HDL-C (SD), mmol/L | Creatinine (SD) | Statin use (%) | Prior Revasc (%) | Prior MI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4C | 30.2 (5.7) | 133.8 (23) | 77.9 (12.2) | 21.8 | 19.1 | 4.64 (1.10) | NA | 1.309 (0.42) | 98.7 (81) | 24.7 | 20.6 | 14.1 |

| AGNES | 26.6 (3.9) | NA | NA | 7.9 | 61.0 | 5.26 (1.04) | 3.25 (1.01) | 1.198 (0.45) | NA | 10.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| ANGES | 28.1 (4.4) | NA | NA | 30.8 | 14.7 | 4.71 (0.84) | 2.68 (0.77) | 1.166 (0.33) | 83.0 (37) | 69.4 | 42.4 | 24.7 |

| ATVB | 26.8 (4.0) | 132.4 (21) | 83.5 (13.5) | 8.2 | 79.5 | 5.83 (1.39) | NA | 1.080 (0.33) | NA | 55.4 | NA | NA |

| CABGenomics | 29.8 (5.6) | NA | NA | 9.0 | 10.3 | 4.32 (0.94) | 2.13 (0.85) | 1.085 (0.35) | NA | 74.1 | NA | 37.0 |

| CARDIOLINES | 26.9 (3.8) | 134.4 (23) | 84.34 (14.6) | NA | 0.6 | 5.43 (1.1) | 3.84 (1.0) | 1.16 (0.3) | 73.09 (15) | NA | NA | NA |

| CDCS | 27.3 (4.7) | 129.1 (22) | 74.6 (11.7) | 15.2 | 5.8 | 5.01 (1.09) | 2.95 (1.03) | 1.175 (0.34) | 100.8 (41) | 46.0 | 26.5 | 30.4 |

| COGEN | NA | NA | NA | 16.7 | 26.2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| COROGENE | 27.6 (4.8) | NA | NA | 18.2 | 34.4 | 4.58 (0.99) | 2.43 (0.88) | 1.250 (0.37) | 84.0 (46) | 5.2 | NA | NA |

| CTMM | 27.6 (4.4) | 135.5 (19) | 77.4 (11.2) | 21.0 | 20.9 | 4.54 (1.06) | 2.59 (0.98) | 1.135 (0.32) | 86.2 (40) | NA | NA | 30.3 |

| CURE | 27.7 (4.5) | 135.1 (22) | 77.1 (13.6) | 20.9 | 23.0 | NA | NA | NA | 93.1 (35) | NA | 14.8 | 31.7 |

| EGCUT | 29.0 (5.2) | 135.7 (18) | 80.4 (10.6) | 18.9 | 19.8 | 5.70 (1.17) | 3.84 (1.08) | 1.340 (0.35) | NA | 27.7 | 15.4 | 35.3 |

| EMORY | 29.8 (6.7) | 137.0 (22) | 75.0 (15.0) | 34.2 | 7.8 | 4.49 (1.04) | 2.42 (0.93) | 1.090 (0.34) | 100.2 (56) | 74.2 | 59.6 | 26.8 |

| ERICO | 27.0 (5.1) | 134.8 (32) | 99.4 (38.0) | 39.4 | 31.2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 23.8 | 11.7 | 26.2 |

| FASTMI2005 | 27.2 (4.8) | 139.9 (28) | 80.0 (17.0) | 35.9 | 29.1 | 5.03 (1.22) | 3.03 (1.07) | 1.239 (0.43) | 103.4 (62) | 74.1 | NA | 18.2 |

| FINCAVAS | 27.8 (4.3) | 140.2 (22) | 82.2 (10.6) | 18.4 | 24.3 | 4.70 (0.90) | 2.62 (0.80) | 1.300 (0.39) | 90.8 (70) | 57.3 | 32.6 | 39.0 |

| FRISCII | 26.8 (3.9) | 143.4 (23) | 82.0 (10.6) | 12.8 | 27.0 | 5.81 (1.12) | 3.72 (0.99) | 1.151 (0.36) | 90.6 (19) | 12.3 | 12.1 | 27.2 |

| GENDEMIP | 28.6 (4.7) | 137.1 (21) | 84.0 (10.8) | 19.0 | 61.0 | 5.42 (1.16) | 3.58 (1.09) | 1.183 (0.33) | NA | 16.7 | 30.2 | 40.8 |

| GENEBANK | 29.4 (5.4) | 132.7 (21) | 75.0 (12.0) | 11.8 | 16.8 | 4.38 (0.93) | 2.51 (0.82) | 0.903 (0.26) | NA | 71.8 | 65.3 | 56.1 |

| GENESIS-PRAXY | 29.5 (6.5) | 139.5 (27) | 86.2 (17.2) | 13.9 | 44.2 | 4.87 (1.19) | 2.89 (1.13) | 0.966 (0.30) | 75.9 (20) | 92.9 | 11.4 | 11.5 |

| GENOCOR | NA | 129.5 (20) | 75.4 (11.1) | 13.3 | 64.4 | 4.82 (0.92) | 3.10 (0.83) | 1.082 (0.28) | 94.8 (27) | 72.1 | 13.7 | 63.2 |

| GEVAMI | 27.2 (4.3) | 124.8 (18) | 73.2 (11.1) | 8.9 | 52.4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 13.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| GoDARTSincident | 29.8 (5.6) | 126.7 (17) | NA | 70.9 | NA | 4.57 (1.02) | 2.43 (0.91) | 1.277 (0.41) | 107.0 (65) | 49.6 | 0.2 | 1.2 |

| GoDARTSprevalent | 30.2 (5.4) | 136.0 (20) | NA | 75.8 | 14.5 | 4.37 (0.84) | 2.04 (0.74) | 1.320 (0.38) | 101.0 (34) | 66.3 | 30.2 | 46.8 |

| GRACE_B | 27.0 (4.3) | 138.3 (25) | 78.7 (14.6) | 81.1 | 49.3 | 5.19 (1.20) | 3.06 (1.09) | 1.343 (0.98) | 102.6 (63) | 79.4 | NA | 80.5 |

| GRACE_UK | 27.9 (5.0) | 137.9 (27) | 76.4 (16.5) | 13.9 | 69.2 | 5.20 (1.27) | 3.07 (1.14) | 1.204 (0.49) | 101.5 (38) | 14.5 | 20.2 | 30.0 |

| IDEAL | 27.3 (3.8) | 136.9 (20) | 80.4 (10.2) | 11.9 | 20.7 | 5.09 (1.00) | 3.14 (0.90) | 1.192 (0.31) | 100.6 (17) | 75.5 | 40.9 | 100.0 |

| INTERMOUNTAIN | 29.5 (6.1) | 141.8 (24) | 81.1 (13.3) | 20.3 | 10.2 | 4.91 (1.12) | 2.76 (0.94) | 1.048 (0.35) | 99.6 (67) | 38.7 | NA | 6.6 |

| INVEST | 29.4 (5.6) | 148.4 (18) | 82.4 (10.5) | 24.3 | 13.3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 52.7 | 48.1 | 23.3 |

| JUMC | 26.3 (4.5) | 148.2 (25) | 80.3 (12.4) | 36.1 | 27.5 | 4.97 (1.08) | 3.11 (1.14) | 1.232 (0.37) | 91.3 (42) | 87.5 | 49.8 | 39.9 |

| KAROLA | 26.9 (3.3) | 120.0 (16) | 73.1 (9.1) | 18.6 | 31.8 | 4.44 (0.84) | 2.61 (0.76) | 1.030 (0.28) | 82.7 (28) | 77.0 | 42.8 | 22.4 |

| LIFE-Heart | 28.9 (4.7) | 139.0 (22) | 80.0 (12.9) | 33.9 | 27.8 | 5.16 (1.19) | 3.12 (1.05) | 1.227 (0.35) | 88.8 (34) | 45.8 | NA | 13.3 |

| LURIC | 27.5 (4.0) | 142.2 (24) | 81.0 (11.5) | 44.1 | 24.6 | 4.94 (0.99) | 2.98 (0.89) | 0.965 (0.26) | 88.7 (38) | 58.9 | 48.3 | 57.8 |

| MDCS | 25.8 (4.0) | 141.1 (20) | 85.6 (10.0) | 4.4 | 26.6 | 6.17 (1.1) | 4.16 (1.0) | 1.38 (0.4) | 84.76 (16) | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| NE_POLAND | 24.8 (3.8) | 138.7 (27) | 88.1 (15.6) | 22.3 | 48.5 | 5.12 (1.04) | 3.31 (0.97) | 1.126 (0.34) | 92.0 (36) | 81.2 | 1.7 | 11.2 |

| NEAPOLIS | 28.0 (4.2) | 129.4 (14) | 75.7 (7.7) | 42.7 | 26.9 | 4.49 (1.03) | 2.45 (0.99) | 1.233 (0.66) | 101.0 (68) | 82.6 | 41.9 | 40.9 |

| OHGS | 28.5 (4.9) | 132.2 (19) | 72.1 (11.3) | 5.5 | 19.3 | 5.57 (1.05) | 3.46 (0.88) | 1.222 (0.34) | 89.1 (21) | 91.6 | 27.8 | 23.3 |

| PERGENE | 27.5 (3.5) | 136.9 (15) | 81.8 (8.1) | 12.7 | 14.7 | 5.41 (1.04) | NA | NA | 86.5 (26) | 55.3 | 54.6 | 65.4 |

| PLATO | 28.2 (4.5) | 135.6 (22) | 79.5 (12.9) | 22.8 | 35.2 | 5.40 (1.23) | 3.27 (1.11) | 1.279 (0.35) | 85.6 (26) | 79.7 | 15.1 | 20.6 |

| PMI | 26.5 (3.8) | 116.5 (16) | 66.5 (9.6) | 12.5 | 28.0 | 5.97 (1.19) | 3.98 (1.07) | NA | 88.0 (28) | 44.6 | NA | 18.4 |

| POPular | 27.2 (4.1) | 144.9 (22) | 81.4 (12.1) | 19.0 | 27.6 | 4.56 (0.94) | 2.73 (1.15) | 1.260 (0.32) | 92.7 (27) | 80.7 | 32.9 | 43.6 |

| POPular Genetics | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| PROSPER | 26.6 (3.9) | 150.0 (22) | 81.1 (11.4) | 10.4 | 17.3 | 5.55 (0.84) | 3.74 (0.74) | 1.174 (0.31) | 109.2 (23) | 0.0 | 26.5 | 86.9 |

| RISCA | 27.2 (4.4) | NA | NA | 19.8 | 30.4 | NA | NA | NA | 100.6 (29) | 46.6 | 28.3 | 27.8 |

| SHEEP | 26.8 (4.0) | 131.8 (21) | 79.6 (10.3) | 18.2 | 50.1 | 6.20 (1.16) | 4.22 (1.01) | 1.082 (0.31) | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| SMART | 27.4 (3.7) | 137.0 (19) | 80.1 (10.8) | 17.1 | 24.2 | 4.66 (0.95) | 2.64 (0.88) | 1.231 (0.72) | 92.3 (23) | 77.5 | 100.0 | 44.5 |

| STABILITY | 29.9 (5.0) | 131.7 (16) | 79.1 (10.0) | 38.4 | 21.4 | NA | 2.25 (0.85) | 1.216 (0.32) | NA | 97.3 | 74.6 | 58.6 |

| THI | 29.6 (5.6) | NA | NA | 30.4 | 21.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 57.2 | 21.7 | 16.7 |

| TNT | 28.5 (4.5) | 130.7 (17) | 77.9 (9.4) | 14.2 | 13.3 | 4.53 (0.61) | 2.52 (0.45) | 1.223 (0.28) | 104.5 (17) | 70.1 | NA | 58.2 |

| TRIUMPH | 29.6 (6.0) | 117.7 (18) | 68.1 (10.9) | 29.1 | 37.4 | NA | 2.70 (1.02) | 1.037 (0.33) | 113.7 (81) | 89.0 | 27.2 | 18.5 |

| UCORBIO | 27.2 (4.3) | NA | NA | 21.4 | 23.1 | 4.80 (1.18) | 2.64 (1.05) | 1.205 (0.33) | 92.0 (45) | 63.9 | NA | 29.0 |

| UCP | NA | 153.4 (25) | 87.1 (13.3) | NA | NA | 5.66 (1.10) | 3.36 (1.01) | 1.244 (0.33) | 94.7 (25) | 27.0 | NA | NA |

| UKB | 29.4 (4.9) | 139.1 (20) | 78.7 (10.9) | 22.2 | 75.9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 82.9 | 59.6 | 36.7 |

| VHS | 26.8 (3.6) | NA | NA | 18.4 | 69.1 | 5.51 (1.13) | 3.69 (1.00) | 1.175 (0.30) | 96.7 (32) | 46.4 | 17.6 | 59.4 |

| VIVIT | 27.4 (4.1) | 137.4 (19) | 80.6 (10.9) | 31.0 | 19.4 | 5.36 (1.15) | 3.33 (1.02) | 1.348 (0.40) | 89.9 (41) | 49.9 | 20.6 | 30.4 |

| WARSAW ACS | 28.1 (4.7) | 128.0 (23) | 76.2 (13.2) | 21.8 | 42.4 | 4.98 (1.06) | 2.99 (1.02) | 1.105 (0.33) | 93.5 (44) | NA | NA | 18.9 |

| WTCC | 27.6 (4.2) | 143.6 (22) | 84.3 (12.3) | 11.7 | 12.8 | 5.31 (0.98) | 3.12 (0.90) | 1.198 (0.38) | NA | 71.6 | 67.2 | 72.0 |

Data were collected through a federated analysis. Alias denotes the abbreviated name of study used in figures and analyses; BMI = body mass index; BP = blood pressure; LDL-C = low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MI = myocardial infarction; mean (standard deviation) and proportions (%) are provided unless otherwise stated.

Additional phenotypes

A list of selected additional phenotypes available by study is presented in Supplementary Table 1. Of note, 79% have available data on plasma C-Reactive Protein (CRP), while coronary disease burden information, from invasive angiography is available in 52% of studies. Finally, over a third of studies have also collected data on physical activity (38%) and socioeconomic status (37%).

Samples

Stored samples are available in most studies for future assay testing and stored frozen. The majority have stored plasma (75%), while others also have serum, blood EDTA, RNA and urine (Supplementary Table 2).

DNA & Genotyping

More than two thirds of the studies have DNA still available, either pre-extracted or as whole blood collected in EDTA and stored for future genotyping. All studies within the consortium have performed genotyping in some capacity, with genome-wide data available in a subset of studies (Supplementary Table 3).

Subsequent Events & Follow up

The most commonly collected endpoint was all-cause death, collected by all but two studies. CHD death during follow up was collected in 70% of studies, while incident MI was reported by 82% of studies. Studies ascertained endpoints through different means, including telephone contact, in-person patient interviews, clinical chart reviews and linkage to national mortality registers and hospital records (Supplementary Table 4).

Power Calculations

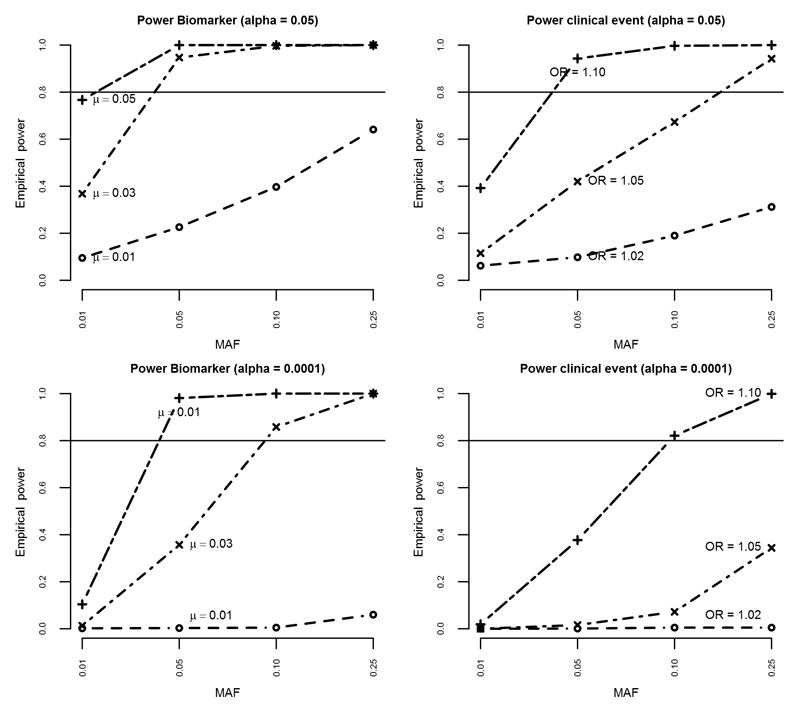

Empirical power was estimated based on a conservative sample size of 150,000 subjects with an event rate of 10% (across the entire follow-up period with a mean of about five years); Figure 2. Given that the GENIUS-CHD consortium is designed to answer multiple questions, power was estimated for a range of genetic (SNPs) and non-genetic (biomarkers, clinical risk factors) effects.

Figure 2.

Figure illustrating empirical power for detecting different effect sizes for biomarker variance and clinical events for both alpha 0.05 and 0.0001, by varying minor allele frequencies, for a conservative total N of 150,000 with an event rate of 10%. MAF = minor allele frequency; OR = odds ratio

Minor allele frequencies (MAF) of 0.01, 0.05, 0.10 and 0.25 were examined, representing rare to common SNPs. For each MAF, power was calculated for a range of plausible SNP effects on biomarkers (mean difference (μ) 0.01, 0.03, 0.05) and clinical endpoints (odds ratios (ORs) of 1.02, 1.05, 1.10). For the association of SNPs with biomarkers, power was 80% (alpha=0.05) or more unless the SNP was rare (MAF of 0.01) or the effect size was small (e.g., 0.01 per allele). For the association of SNPs with clinical endpoints, power was close to 80% when the effect size was large (OR ≥ 1.10) or the MAF was ≥ 0.10.

Power of observational (i.e. non-genetic) analysis was >99% for both continuous and binary exposures unless the OR was close to 1. In addition to continuous and binary outcome data, GENIUS-CHD also collects time-to-event data. Given the similarity (in most empirical settings) between OR and hazard ratios,20 similar power is to be expected for time-to-event analysis.

Initial Analysis

To examine the feasibility of the federated analysis approach, we sought to collect data on participant characteristics, cardiovascular and mortality outcomes and association analyses with common clinical exposures. A standardised dataset was developed, with a federated analysis conducted using standardised statistical scripts. The summary level outputs generated were then shared with the coordinating centres for aggregating and meta-analysis (Supplementary Methods).

Participant characteristics

Detailed characteristics of participants by study are presented in Table 2. Prevalence of risk factors varied by study, with diabetes ranging from 4 to 76%; smoking from 8 to 79%. Mean total cholesterol by study ranged from 166.3 to 239.8 mg/dL, mean BMI ranged from 24.8 to 30.2kg/m2 and mean systolic blood pressure from 117 to 153mmHg. The proportion of participants with prior revascularization or MI was high in most studies reflecting the inclusion criteria for the consortium (Table 2).

Review of returned outputs from the federated analysis revealed good quality data with estimates falling within expected ranges for age, sex, and other variables such as body mass index (Supplementary Figure 1).

Endpoints

The primary endpoint pre-selected for the study was a composite of coronary death or MI (CHD death/MI). Mean follow up was estimated in each study and ranged between 9 months and 15 years. In total we estimated over 748,000 person years of follow up were available for the primary endpoint analysis.

Information was collected on 10 subsequent event endpoints in the initial feasibility analysis. Across all studies, the most frequently occurring event during prospective follow up was the composite of all cardiovascular events (27%); followed by revascularization (21.8%); all-cause mortality (15%); coronary death or MI (14.2%); myocardial infarction (10.7%); cardiovascular death (8.3%); coronary death (8%); heart failure (6.3%); all stroke (3.6%) and ischaemic stroke (3.4%).

Association analyses

As a feasibility analysis, we examined associations between age, male sex and smoking with the primary endpoint CHD death/MI as well as with the nine other secondary endpoints, to investigate any differential associations across discrete subsequent events.

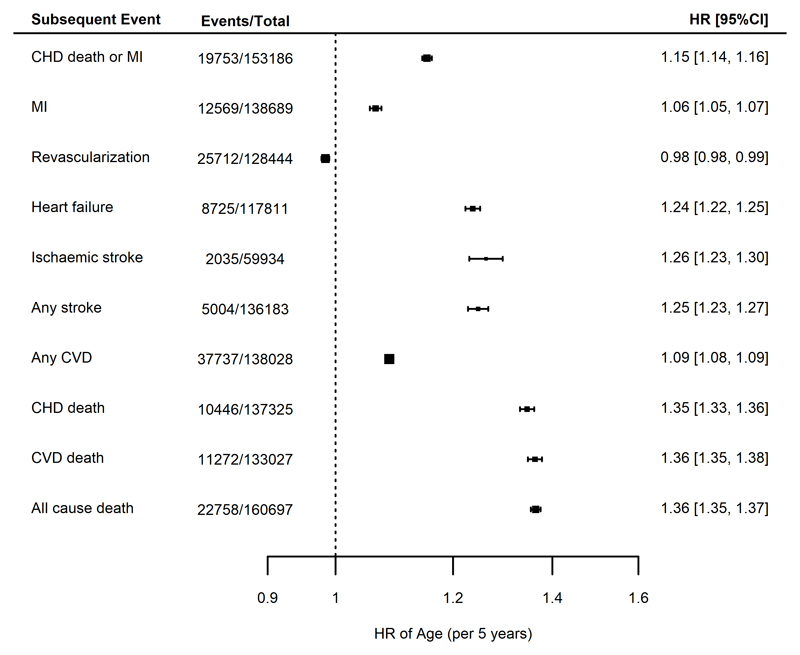

In analyses unrestricted by race or type of CHD at baseline, but adjusted for sex, there was a strong association between each 5-year increment in age with subsequent risk of the primary endpoint of CHD death/MI (HR 1.15, 95% CI 1.14-1.16). The largest observed hazard ratios were for all-cause mortality (HR 1.36, 95% CI 1.35-1.37), cardiovascular death (HR 1.36, 95% C.I. 1.35, 1.38) and heart failure (HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.24, 1.27), while a smaller risk increase was observed for MI (HR 1.06, 95% CI 1.05-1.07). The risk of future revascularization, however, showed a modest inverse association with increasing age (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.98-0.99) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Meta analyses of the associations between age (per 5-year intervals) and different endpoints, adjusted for sex. Estimates are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). CHD = coronary heart disease; CVD = cardiovascular disease; MI = myocardial infarction.

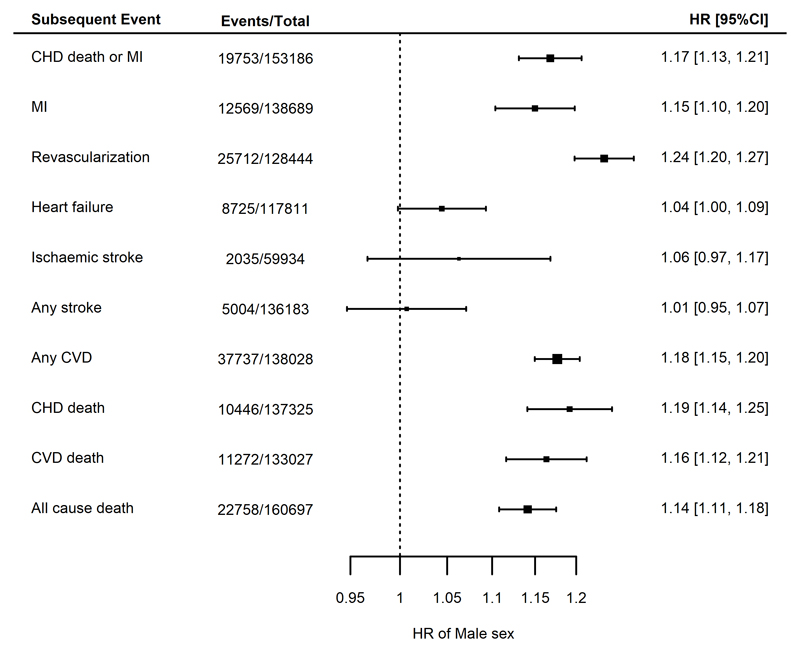

Male sex was a risk factor for CHD death/MI (HR 1.17, 95% CI 1.13- 1.21) and other coronary and mortality endpoints (Figure 4) after adjustment for age. In particular, the largest observed hazard ratio was for risk of revascularization, which was considerably higher in males (HR 1.24, 95% C.I. 1.20, 1.27). In contrast, there was no strong evidence for an association between male sex and risk of stroke (ischemic or any stroke, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Meta analyses of the associations between male sex and different endpoints, adjusted for age. Estimates are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). CHD = coronary heart disease; CVD = cardiovascular disease; MI = myocardial infarction.

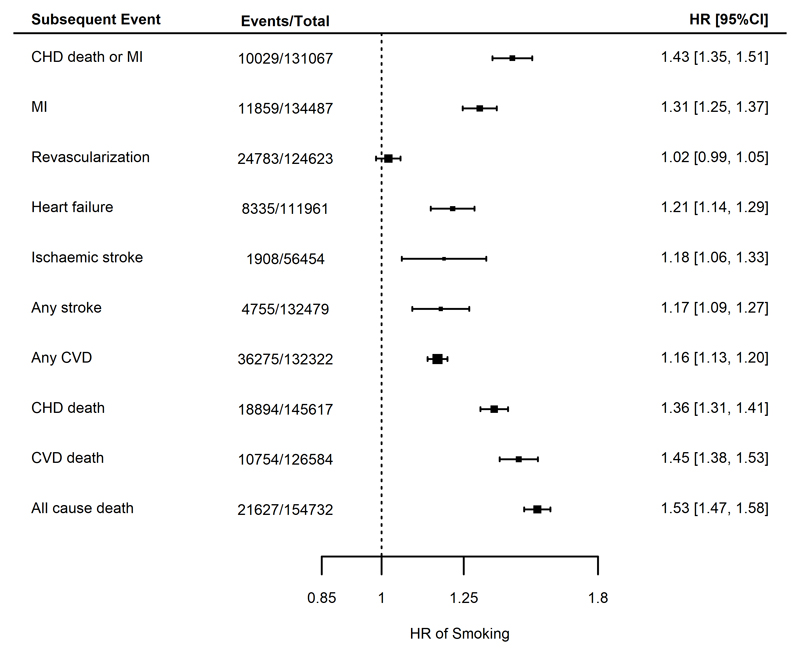

Finally, in analyses adjusted for age and sex, current smoking (compared to prior or never smoking) at the time of enrolment showed a strong association with risk of future CHD death/MI (HR 1.43, 95% C.I. 1.35-1.51). Similarly, smoking was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality (HR 1.53, 95%CI 1.47-1.58) and an increased risk of all other end points, although there was no strong evidence for an association with incident revascularization (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.99-1.05, Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Meta analyses for the associations between smoking at CHD indexing event compared to not smoking and for different endpoints, adjusted for age and sex. Estimates are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). CHD = coronary heart disease; CVD = cardiovascular disease; MI = myocardial infarction.

When stratified by type of CHD at enrolment, i.e. among those presenting with an acute event, those with stable CAD without ever having had an MI and those with stable CAD and a prior MI, the findings were similar and directionally concordant to non-stratified analyses described above, for all endpoints (data not shown).

Discussion

The GENIUS-CHD Consortium is a global collaborative effort engaging 57 studies, including almost 185,000 patients with established CHD, for whom genetic and prospective follow-up data are available. It brings together over 170 domain experts, including clinicians, data scientists, geneticists and epidemiologists, all engaged in improving our understanding of the determinants of subsequent event risk in these patients. With an agreed governance structure and a proven federated analysis approach, we anticipate that this consortium will be a valuable long-term resource for genetic and non-genetic research in this field.

Genetic association studies for CHD disease progression, recurrence and adverse events after a CHD event may have particular utility for identifying novel causal pathways and therapeutic targets that may be different than those for first events, a concept recently supported by research in other disease areas.21 However, information on the determinants of subsequent CHD event risk is scarce, in contrast to the extensive knowledge about risk factors for a first CHD event. This disparity is due in part to the relatively small sample sizes of individual studies in the secondary prevention setting. While larger registry and electronic health care records (EHR) efforts will result in higher numbers, they typically suffer from the lack of necessary depth of phenotyping, accuracy, and availability of bio-specimens to infer further biological insights.22, 23 In contrast, large population studies with detailed phenotyping have relatively small numbers of mostly stable CHD patients, who have survived many years after their index event.24, 25 By bringing together multiple investigator-led studies, the GENIUS-CHD consortium aims to address and overcome this major limitation to subsequent CHD risk research.

Importantly, the scale and depth of the GENIUS-CHD consortium offers greater scope to tackle key challenges within subsequent CHD risk-related research. Firstly, CHD is a heterogeneous phenotype, consisting of stable, unstable and pathologically distinct subtypes, which have often been combined for individual studies to satisfy the need for statistical power. With the sample size available in GENIUS-CHD, we anticipate being able to disaggregate CHD into more precise sub-phenotypes such as acute vs. stable CHD at baseline, or those with vs. without prior MI, which may help uncover relevant biological differences.26 Additional stratification on variables such as sex, time period of recruitment, duration of follow-up, country of study, LV function and treatment (such as statin, blood pressure lowering and anti-platelet agent use) will also be possible, providing greater insights into the modifying influences of these variables on outcome.

A major strength of the consortium is the use of a federated analysis approach that permits individual level analysis without the need for sharing either samples or the individual datasets themselves, thereby overcoming major privacy and governance hurdles. The effort has been successful because (1) participation is entirely voluntary, with studies only participating in those analyses they feel are of value, or to which they have the capacity to contribute; (2) ownership of all data and samples remain with the PI and are not shared nor stored centrally; and (3) there are open and transparent governance procedures. Our feasibility analysis has demonstrated that this federated approach works well and yields results that are consistent and suitable for high quality meta-analysis.

Indeed, supported by this initial feasibility analysis, our findings demonstrate the validity of the data collected by confirming the anticipated associations of increasing age, male sex, and current smoking with higher risks of subsequent CHD death/MI during follow up. Furthermore, by exploring multiple individual and composite endpoints, we can begin to unravel associations not discoverable in smaller studies. For example, we find that the risk of incident revascularization is lower with advancing age but higher for male sex and neutral for smoking. Plausible explanations may exist for each of these findings (e.g. an association induced by clinical practice, with fewer older people being offered invasive treatments), but importantly they highlight the value of exploring multiple endpoints at appropriate scale. This is especially relevant when exploring novel biomarkers or drug targets as these may, in turn be used to inform clinical testing strategies and choice of endpoints to study in trials.

By virtue of the expertise it has assembled, the consortium is also well placed to address important methodological issues surrounding prognosis research in general. For example, selection bias is a key concern, whereby it is conceivable that those at highest risk may die early and not enter any of the member studies for evaluation (survival bias), or selection on an indexing event itself may distort patient characteristics and impact association findings (index event bias).27 In addition, treatment effects may alter the trajectory of disease by stabilizing or regressing plaque burden or altering baseline risk, such as with high dose statin or PCSK9 inhibitor use.17, 28 To address these and other issues, the consortium has established working groups of relevant national and international experts to explore the extent and impact of such biases/effects and if needed, to develop approaches to address these.29

There are inherent challenges to overcome when working with diverse multiple studies, including variations in definitions and processes for data collection and curation across different studies in different centres and different countries. The consortium members have attempted to standardize common data elements, for example the measurement units for quantitative traits. Variability between studies will persist, but we anticipate that the overall size of the effort will help reduce the impact of such study level heterogeneity on any findings, which will also be explored through subgroup analyses where possible (e.g. country, study size, year of first recruitment). Analytical challenges will additionally include dealing with variability in length of follow up across studies, handling multiple subsequent events along with competing risks, as well as confounding by treatment and selection biases as described above. The collective experience of the consortium members will be leveraged to address these as carefully as possible within each future analysis. Finally, factors influencing enrolment into genetic studies of CHD may limit the generalizability of findings. Men are over represented in participating CHD studies, partly reflecting sex-differential prevalence of disease but also underpinning a wider concern about under-investigation of women, who may be inadvertently excluded given that entry criteria for most studies relies on documented presence of CHD. Similarly, many studies in the consortium have recruited mostly Europeans, limiting the opportunity to explore hypotheses in other ethnic groups. The steering committee is conscious of these imbalances and is actively seeking studies enriched for women and non-European participants to join the collaboration. In summary, the GENIUS-CHD consortium is a global collaboration among investigators who have recruited patients with CHD into multiple individual studies, seeking to gain a better understanding of subsequent CHD event risk and enhance secondary prevention. It seeks to be an open, collegiate and transparent effort and we invite investigators with suitable studies to join and collectively enhance research efforts in this domain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The GENIUS CHD collaborators would like to express their immense gratitude to all patients who participated in each of the individual studies as well as the many personnel who helped with recruitment, collection, curation, management and processing of the samples and data.

Sources of Funding: The funder(s) of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. Within GENIUS-CHD, all participating investigators and sponsors who contributed data and analyses are acknowledged irrespective of academic or industry affiliations.

Specific funding statements: Dr Patel is funded by a British Heart Foundation Intermediate Fellowship (FS/14/76/30933). This research was also supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre; Dr Schmidt is funded by BHF grant PG/18/5033837 ; Dr Holmes works in a unit that receives funding from the UK Medical Research Council and is supported by a British Heart Foundation Intermediate Clinical Research Fellowship (FS/18/23/33512) and the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre.; The AGNES study was supported by research grants from the Netherlands Heart Foundation (2001D019, 2003T302, 2007B202 and the PREDICT project (CVON 2012-10)), the Leducq Foundation (grant 05-CVD) and the Center for Translational Molecular Medicine (CTMM COHFAR). ; The Cleveland Clinic Genebank Study was supported in part by NIH grants R0133169, R01ES021801, R01MD010358, and R01ES025786, R01HL103866, R01DK106000, R01HL126827, P20HL113452., P01HL098055, P01HL076491, and R01HL103931; The Clinical Cohorts in Coronary disease Collaboration (4C) study was supported in part by NIHR and Barts Charity; The Corogene study was supported by grants from Aarno Koskelo Foundation, Helsinki University Central Hospi-tal special government funds (EVO #TYH7215, #TKK2012005, #TYH2012209, #TYH2014312), and Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular research ; CABGenomics was supported by Stanton Shernan, C. David Collard, Amanda A. Fox/R01 HL 098601 NHLBI; The CDCS and PMI studies were funded by the Health Research Council and Heart Foundation of New Zealand; Dr Samman-Tahnan is supported by the National Institutes of Health/ National Institutes of Aging grant AG051633; Dr Sandesara is supported by the Abraham J. & Phyllis Katz Foundation (Atlanta, GA, USA); The Emory Cardiovascular Biobank is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants 5P01HL101398-02, 1P20HL113451-01, 1R56HL126558-01, 1RF1AG051633-01, R01 NS064162-01, R01 HL89650-01, HL095479-01, 1U10HL110302-01, 1DP3DK094346-01, 2P01HL086773-06A1; The Estonian Biobank was funded by EU H2020 grant 692145, Estonian Research Council Grant IUT20-60, IUT24-6, PUT1660, PUT735 and European Union through the European Regional Development Fund Project No.2014-2020.4.01.15-0012 GENTRANSMED, NIH – GIANT, ERA-CVD grant Detectin-HF and 2R01DK075787-06A1.; FAST-MI (French Registry of Acute ST-Elevation or non- ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction) 2005 is a registry of the French Society of Cardiology, supported by unrestricted grants from Pfizer and Servier. Additional support was obtained from a research grant from the French Caisse Nationale d'Assurance Maladie. ; GENESIS-PRAXY is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Heart and Stroke Foundations of Alberta, NWT & Nunavut, British Columbia and Yukon, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec (HSFC); The GENDEMIP study was supported by Project (MH, Czech Republic) No. 00023001 (ICEM, Prague); GoDARTS was funded by the Wellcome Trust (072960/Z/03/Z, 084726/Z/08/Z, 084727/Z/08/Z, 085475/Z/08/Z, 085475/B/08/Z) and as part of the EU IMI-SUMMIT programme. C.N.A.P. has received grant funding from the Wellcome Trust to develop the GoDARTS cohort. ; Dr Mordi is supported by an NHS Education of Scotland/Chief Scientist Office Postdoctoral Clinical Lectureship (PCL 17/07); the GENECOR stuidy was supported in part by the Italian Ministry of Research's Fund for Basic Research (FIRB 2005); GRACE UK was supported in part by an Educational Grant from Sanofi Aventis; Award from Chief Scientist Office, Scotland; INVEST-GENES was supported by the National Institute of Health Pharmacogenomics Research Network grant U01-GM074492, NIH R01 HL074730, University of Florida Opportunity Fund, BASF Pharma and Abbott Laboratories. ; IATVB was supported by Epidemiologia e Genetica della Morte Improvvisa in Sardegna; The KAROLA study has received financial support by the German Ministry of Education and Research (01GD9820/0 and 01ER0814), by the Willy-Robert-Pitzer Foundation, and by the Waldburg-Zeil Clinics Isny.; The KRAKOW GENIUS Study was supported by a grant from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, no. NN402083939 and the National Science Centre, no. 2013/09/B/NZ5/00770; LIFE-Heart was funded by the Leipzig Research Center for Civilization Diseases (LIFE). LIFE is an organizational unit affiliated to the Medical Faculty of the University of Leipzig. LIFE is funded by means of the European Union, by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and by funds of the Free State of Saxony within the framework of the excellence initiative.; The LURIC study was supported by the 7th Framework Program (AtheroRemo, grant agreement number 201668 and RiskyCAD, grant agreement number 305739) of the European Union; Dr JG Smith was supported by grants from the European Research Council, Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation, the Swedish Research Council, the Crafoord Foundation, governmental funding of clinical research within the Swedish National Health Service, Skåne University Hospital in Lund, and the Scania county, a generous donation from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg foundation to the Wallenberg Center for Molecular Medicine at Lund University, and funding from the Swedish Research Council and Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research to the Lund University Diabetes Center.; The NEAPOLIS CAMPANIA study was suppported by European Research Council Advanced Grant (CardioEpigen, #294609);Italian Ministry of Health (PE-2013-02356818);Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research (2015583WMX) ; The North East Poland Myocardial Infarction Study was supported by grant N N 402 529139 from the National Science Center (Poland); Dr Vilmundarson is supported by a graduate fellowship of the University of Ottawa Heart Institute; OHGS was funded in part by a Heart and Stroke Foundation grant; Dr Stott was supported in part by an investgator initiated grant from Bristol Myers Squibb USA; The PROSPER study was supported by an investigator initiated grant obtained from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Prof. Dr. J. W. Jukema is an Established Clinical Investigator of the Netherlands Heart Foundation (grant 2001 D 032). Support for genotyping was provided by the seventh framework program of the European commission (grant 223004) and by the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (Netherlands Consortium for Healthy Aging grant 050-060-810). ; The RISCA study ws supported in part by FRSQ, HSFC, Merck Frost Canada, Pfizer Canada; The SHEEP study was supported by grants from the Swedish Council for Work Life and Social Research, and the Stockholm County Council. ; The TNT trial was sponsored by Pfizer who granted access to data, Genotyping of the samples was funded in part by grants from Genome Canada and Genome Quebec and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).; Dr Arsenault holds a junior scholar award from the Fonds de recherche du Quebec- Sante (FRQS); Dr. Cresci is supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (Cresci R01 NR013396). The TRIUMPH study was sponsored by the National Institutes of Health: Washington University School of Medicine SCCOR Grant P50 HL077113. ; The UCP studies were funded by the Netherlands Heart Foundation and the Dutch Top Institute Pharma Mondriaan Project; The Verona Heart Study was supported by the Cariverona Foundation; Veneto Region; Italian Ministry of Education, University, and Research (MIUR); LURM (Laboratorio Universitario di Ricerca Medica) Research Center, University of Verona; The Warsaw ACS Registry is supported by grant N R13 0001 06 from The National Centre for Research and Development (NCBiR), Statutory Grant from Medical University of Warsaw; Dr Nelson is funded by the British Heart Foundation; Prof. Samani is funded by the British Heart Foundation and is a NIHR Senior Investigator; Prof Hingorani is a NIHR Senior Investigator. Prof Asselbergs is supported by UCL Hospitals NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, EU/EFPIA Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking BigData@Heart grant n° 116074, the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the ERA-NET Co-fund action N°01KL1802 (Druggable-MI-gene) jointly funded by the Dutch Heart Foundation and Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw).

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr Patel has received speaker fees and honoraria from Amgen, Sanofi and Bayer and research funding from Regeneron; Dr Holmes has collaborated with Boehringer Ingelheim in research, and in accordance with the policy of the The Clinical Trial Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit (University of Oxford), did not accept any personal payment; Dr Akerblom has received institutional research grant and speakers fee from AstraZeneca, institutional research grant from Roche Diagnostics.; Dr James has received grants from AstraZeneca, The Medicines Company, Swedish heart and lung foundation, Swedish research council, Janssen; personal fees from Bayer; Dr Hagstrom declares being an expert committee member, lecture fees, and institutional research grant from Sanofi, and Amgen; institutional research grants from AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline; expert committee member and lecture fees NovoNordisk and Behringer.; Dr Held declares institutional research grant, advisory board member and speaker’s bureau from AstraZeneca; institutional research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb Merck & Co, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche Diagnostics. Advisory board for Bayer and Boehringer Ingelheim; Dr Lindholm has received institutional research grants from AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline; Speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Speaker fees from AstraZeneca.; Dr Siegbahn has received institutional research grants from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Roche Diagnostics, GlaxoSmithKline.; Dr. J.M. ten Berg reports receiving fees for board membership from AstraZeneca, consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, and Merck, and lecture fees from Daiichi Sankyo and Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Sanofi and Accumetrics; Prof Wallentin reports institutional research grants, consultancy fees, lecture fees, and travel support from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim; institutional research grants from Merck & Co, Roche Diagnostics; consultancy fees from Abbott; and holds a patent EP2047275B1 licensed to Roche Diagnostics, and a patent US8951742B2 licensed to Roche Diagnostics. Prof Asselbergs has received research funding from Regeneron, Pfizer, Sanofi.

References

- 1.Ford ES, et al. Proportion of the decline in cardiovascular mortality disease due to prevention versus treatment: public health versus clinical care. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:5–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sidney S, et al. Recent Trends in Cardiovascular Mortality in the United States and Public Health Goals. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:594–9. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford ES, et al. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980-2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2388–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scarborough PBP, Wickramasinghe K, Smolina K, Mitchell C, Rayner M. Coronary heart disease statistics. 2010 edition. London: British Heart Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yusuf S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deloukas P, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies new risk loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:25–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox KA, et al. Prediction of risk of death and myocardial infarction in the six months after presentation with acute coronary syndrome: prospective multinational observational study (GRACE) BMJ. 2006;333:1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38985.646481.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiele F, et al. Coronary artery disease: Risk stratification and patient selection for more aggressive secondary prevention. Eur J Prevent Cardiol. 2017;24:88–100. doi: 10.1177/2047487317706586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz GG, et al. Effects of dalcetrapib in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2089–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White HD, et al. Darapladib for preventing ischemic events in stable coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1702–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boden WE, et al. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armitage JM, et al. Effects of homocysteine-lowering with folic acid plus vitamin B12 vs placebo on mortality and major morbidity in myocardial infarction survivors: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;303:2486–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Global BMIMC et al. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet. 2016;388:776–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30175-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang ZJ, et al. Association of body mass index with mortality and cardiovascular events for patients with coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2015;101:1631–8. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-307119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cannon CP, et al. Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabatine MS, et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridker PM, et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1119–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel RS, et al. The GENIUS-CHD consortium. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2674–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothman KJ, et al. Modern epidemiology. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JC, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies distinct genetic contributions to prognosis and susceptibility in Crohn's disease. Nat Genet. 2017;49:262–268. doi: 10.1038/ng.3755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohman EM, et al. The REduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) Registry: an international, prospective, observational investigation in subjects at risk for atherothrombotic events-study design. Am Heart J. 2006;151:786 e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Psaty BM, et al. The Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) Consortium as a model of collaborative science. Epidemiology. 2013;24:346–8. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828b2cbb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins R. What makes UK Biobank special? Lancet. 2012;379:1173–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z, et al. China Kadoorie Biobank of 0.5 million people: survey methods, baseline characteristics and long-term follow-up. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:1652–66. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reilly MP, et al. Identification of ADAMTS7 as a novel locus for coronary atherosclerosis and association of ABO with myocardial infarction in the presence of coronary atherosclerosis: two genome-wide association studies. Lancet. 2011;377:383–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61996-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dahabreh IJ, et al. Index event bias as an explanation for the paradoxes of recurrence risk research. JAMA. 2011;305:822–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholls SJ, et al. Effect of Evolocumab on Progression of Coronary Disease in Statin-Treated Patients: The GLAGOV Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316:2373–2384. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu YJ, et al. Impact of Selection Bias on Estimation of Subsequent Event Risk. Circulation Cardiovascular Genetics. 2017;10 doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.